Returning to the Past its Own Future

Harun Farocki’s RESPITE

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Elsaesser, Thomas: Returning to the Past its Own Future: Harun Farocki’s RESPITE. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14781.

There are also witnesses who never encounter an audience capable of listening to them or hearing what they have to say. (Paul Ricoeur)1

Two Near Misses

In October 2006, Harun Farocki and I had almost missed each other in the Index Gallery, Stockholm, at a crowded reception in his honour after the opening of GEGEN-MUSIK (COUNTER-MUSIC, D/F 2004). In the subsequent e-mail exchange, Farocki wanted to know what I could tell him about a film made at Westerbork, the transit camp run by the SS during Nazi Occupation of the Netherlands.2 I replied by telling him about Cherry Duyns’ HET GESICHT VAN HET VERLEDEN (NL 1994), a documentary about the camp footage shot by Rudolf Breslauer and about Aad Wagenaar’s (successful) quest to identify the name of film’s iconic image, known as ‘het meisje’ (the girl), also detailed in his book Settela: het meisje heft haar naam terug (1995)3. I also sent him an essay I had published in 1996 on both Duyns’ film and Wagenaar’s detective work, titled One Train May Be Hiding Another.4

A year later, in New York, at the Greene Naftali Gallery - another opening of a Farocki installation, this time DEEP PLAY (D 2007) - Farocki presented me with a package of DVDs, comprising a good part of his oeuvre. I was delighted and quite moved. Among the DVDs was also AUFSCHUB (RESPITE, D/KOR 2007)5. On re-seeing this (to me, familiar) Westerbork material, and reading Farocki’s ‚silent film‘ commentary, my first response was puzzlement, tinged with perplexity. No mention of Cherry Duyns’ film, barely a word about Aad Wagenaar. Yet one of the crucial ‚discoveries‘ made by two forensic experts at the Rijksvoorlichtingsdienst (Government Information Office; who appear in both Duyns’ film and Wagenaar’s book), namely the precise date of the convoy - revealed in the chalked initials and date of birth on the suitcase of the sick woman being deported on a handcart - is also a key ‚discovery‘ in RESPITE.6

The Westerbork footage is among the most familiar pieces of archival footage that the Nazis have left of their otherwise so clandestinely planned and executed deportation and destruction of Europe’s Jews. It is unique in that it shows in relentless detail one particular transport of Jews to Auschwitz, wittingly or unwittingly testifying in heartbreaking fashion to the deception perpetrated by the Nazis and the self-deception of their victims: those who stay behind shake hands and bid farewell to those in the trains, while other unfortunate passengers help the guards bolt the doors of their boxcars. What was less known, at least to the public outside the Netherlands, was that this much-used authentic footage of the deportation had been extracted from a considerably larger ‚documentation‘ of Westerbork camp life, whose origin, intent and purpose was quite different from what it now appears to be, and even contradicting the uses it has so often been put to since. These ‚gaps‘ and mis-alignments are prominent among the themes that RESPITE addresses.

Farocki is justly known for his pioneering use of found footage, from often anonymous and usually very diverse sources. He has an uncanny and extraordinary gift for establishing links and building connections that no one had thought of, or had dared to draw, before.7 By these criteria, even the extended Westerbork footage is not ‚found footage‘ and its makers are not anonymous. Nor does Farocki claim this to be the case: a prefatory intertitle establishes the basic facts of the material’s provenance and putative author(s).8 And yet: the issue of appropriation, recycling and the migration of iconic images - together with the reasons for the increasing use of found footage by artists, its ethics and aesthetics - is here raised in much more complex and perplexing ways than, say, when Farocki acquired surveillance footage from Californian prisons, for ICH GLAUBTE GEFANGENE ZU SEHEN (I THOUGHT I WAS SEEING CONVICTS, D/AUT 2000), or featured scenes from the last interrogation of Nicolae Ceauşescu and his wife Elena before they were executed, id est, VIDEOGRAMME EINER REVOLUTION (VIDEOGRAMS OF A REVOLUTION, D 1992).

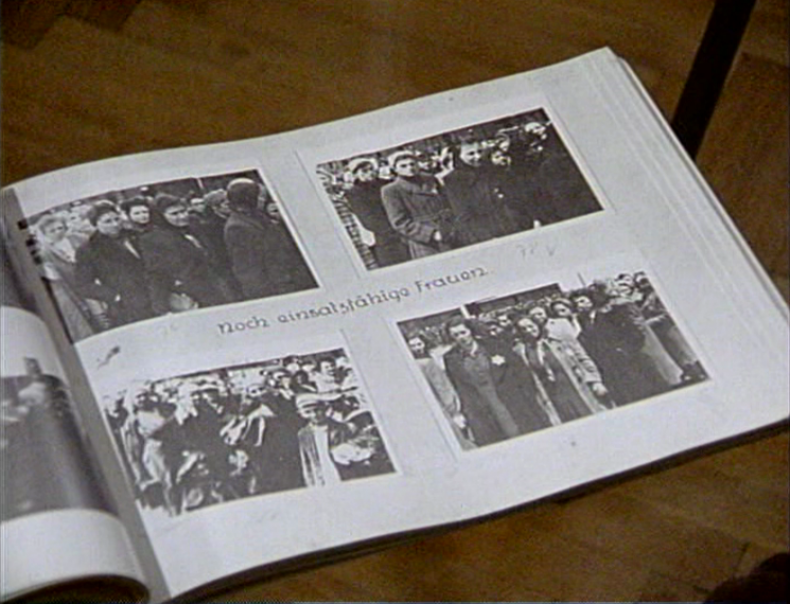

In his e-mail to me, Farocki is aware that part of the Breslauer-Gemmeker film had been used in Alain Resnais’ NUIT ET BROUILLARD (NIGHT AND FOG, F 1955), and he probably knew or learnt about the findings of Sylvie Lindeperg.9 These have further problematized a debate that Farocki was already familiar with from the reception of his own film BILDER DER WELT UND INSCHRIFT DES KRIEGES (IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND INSCRIPTION OF WAR, BRD 1988): the ethics of using (often unattributed) visual material relating to the ‚Holocaust‘, especially when these are film-sequences and photographs taken by the (German) occupiers and perpetrators or even when taken by the (American, British or Russian) liberators of the camps. IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND INSCRIPTION OF WAR explicitly thematizes the dilemma of sharing an alien point of view: that of the aerial photographers of the US Army, on reconnaissance mission, contrasted with the gaze of an SS guard, on his post at the Birkenau ramp. Among the pictures the guard took that day, Farocki selects the one of a young woman, casting a brief glance in the direction of the camera, arguing that in this particular instance, part of the disconcerting fascination comes from the apparent ‚normalcy‘ of the ‚man-looking, woman-being-looked-at‘ situation, occurring in such extreme circumstances. When the film was first shown in the United States, feminist critics queried the ‚objectifying‘ use of the photo of the female detainee, as well as the ‚ventriloquizing‘ use of a female voice-over who speaks Farocki’s commentary.10

Thus, one might have expected Farocki to confront the question of appropriation and the alien gaze also in RESPITE. It is particularly acute in the case of the Westerbork footage, principally for three reasons. First, one of the main points of Aad Wagenaar’s book and Cherry Duyns’ film was to document the mis-appropriation of this one particular image, that of the girl with the headscarf, in the open door of a carriage, who had become a symbol of the suffering of Dutch Jews at the hands of the Germans. In this role she had been featured as text illustration, as book cover and poster girl from the 1960s to the 90s. When Wagenaar established beyond doubt that ‚the Jewish Girl’ was not Jewish but a Sintiza, and that she had a name - Settela Steinbach - her function as icon of the Jewish Holocaust was jeopardized, if not altogether undermined. An image had been appropriated, for the best possible motives, but thereby unwittingly contributing to obliterating another ‚Holocaust‘ perpetrated by the Nazi: the genocide of the Sinti and Roma.11

The second reason why appropriation is a sensitive issue in this case, are the essentially opposed and yet paradoxically convergent motives of he who ordered the footage to be shot (camp Commandant Albert Gemmeker),12 and he who shot the footage (the inmate and professional photographer Rudolf Breslauer): in the very uneven power-structure that bound these two men together - each trying to prove something, though not necessarily to each other - the loaded terms ‚collaboration‘, ‚collusion‘ and ‚cooperation‘ take on the full tragic force which they acquired during World War II. Then, German officials enlisted Jews to administer, police or act as middlemen in the running of the ghettos and concentration camps, and even put Jews in charge of drawing up the lists of those who were to be deported on the trains headed to Auschwitz-Birkenau, Ravensbrück or Sobibor, as seems to have been the case also in Westerbork, where - Farocki draws attention to them – the ‚Fliegende Kolonnen‘ (Flying Convoys) featured prominently, as part of the camp’s ‚Ordnungsdienst‘, the Jewish police and administrative services responsible for almost all aspects of camp life. Who, therefore, do the images belong to, who is their ‚author‘ and through whose eyes are we looking as we watch the film?13

The third reason to raise the issue of appropriation is that the two minute sequence which Resnais took from the nearly 80 minutes’ worth of footage shot by Breslauer, and which he decontextualized by re-editing it, adding images from another transport in Poland, has in turn been further decontextualized and anonymized. One comes across the sequence almost daily, as it is routinely inserted in television docudramas or even news bulletins every time a producer needs to evoke the deportation and the trains, and has only a few seconds to encapsulate them.14

Hiding behind a Camera

These multiple layers of appropriations in the history of the Westerbork film, however, are not the primary focus of my comments here.15 Nor was my initial perplexity caused by Farocki’s omissions or possible mis-appropriation of previous research (filmed or otherwise) on the Breslauer-Gemmeker material. I was puzzled because, knowing Farocki’s work, I assumed there must be a strategy behind his making a film that adds to our ‚memory‘ of the Holocaust, while doing so in a mode of ‚forgetting‘. A second viewing confirmed that RESPITE is indeed about the question of appropriation, but in a manner I had not anticipated. It is unexpected, because I think neither the ethics of ‚appropriation‘, nor the aesthetics of ‚found footage‘ are at issue. Instead, appropriation - understood here as the transfer of knowledge, cultural memory, images or symbols from one generation to another, or as the making one’s own what once belonged to another - finds itself filtered through a process of reflexive identification and self-implication. This self-implication demands that the ”memory of the Holocaust” today not only needs to assert itself against ignorance, but also must prevail against its apparent opposite, too much knowledge. To vary a notorious saying: such memory may have to navigate between the ‚known knowns‘ (what we remember) and the ‚unknown knowns‘ (what we decide to ignore), in order to carve out the space of the ‚unknown unknowns‘ (the knowledge we might have if we neither knew what we knew, nor ignored what we knew).16 What if RESPITE were proposing an ‚epistemology of forgetting‘, that is, what if it posed the question of the kind of knowledge we can derive from no longer knowing what we think we know, and by extension, what it would mean to appropriate Breslauer’s ignorance, rather than his knowledge?

Before trying to address this possibility, I need to backtrack to what it was that presumably attracted Farocki to the Westerbork material. The e-mail gives an admirably succinct clue: „double work as respite [id est suspension of work]“. Farocki continues his examination of the ethics of work (or rather, the ‚work-ethic‘) of the 20th century. The Breslauer-Gemmeker cooperation provides him with a unique - and uniquely poignant17 - example of how ‚work‘ can be thought of not as production or progress, but as a delay and deferral, or AUFSCHUB, as the somewhat crisper German title puts it, which means ‘postponement’ as much as it is a ‚respite‘. „Aufgeschoben ist nicht aufgehoben.“, goes a familiar phrase, to indicate that if I defer a promise or an action, it does not mean that it is cancelled. One of the pivots of the film is the idea that those who are making the film and those who perform in it are engaged in ‚delaying tactics‘: the more they dismantle airplane parts, recycle batteries, strip electric wires and till the land (and, as Farocki was pleased to discover, the more Breslauer can film them doing so in ‚slow-motion‘), the more they can demonstrate their usefulness. And the more useful they are to the German war effort, the longer they hope to stay in the camp, while the film itself not only uses slow-motion, but in its somewhat disorganized, casual and non-linear manner also practices its own kind of deferral, trying to stave off ‚the inevitable‘: the order to board next Tuesday’s train.

But this ‚inevitability‘ is part of the knowledge gained from hindsight, not necessarily shared by the protagonists. As Farocki ventures, there might have been the notion that ‚work‘ in Westerbork was desirable simply because ‚better the devil you know…‘: „everyone tried to stay in Westerbork, maybe not because they knew what awaited them if they were ordered to leave for ‚work-detail in the East‘, but because they knew that here at least, they had enough to eat.“18 Gemmeker, who made a point of treating his inmates ‚correctly‘ - neither beating or verbally abusing them - had his own reasons for colluding with the decoy-and-delay exercise that Farocki thinks Breslauer was engaged in. Unlike Hans Günther - the SS officer in Prague who when commissioning Kurt Gerron to make a film in and about Theresienstadt set out to camouflage the reality of camp life in order to deceive the Danish Red Cross19 - Gemmeker wanted to prove to his masters in Berlin what an exemplary camp he ran, how efficiently both work and leisure were organized and how orderly the weekly transports were dispatched. But he too, had an ulterior motive, and was anxious for a respite, indeed a reprieve: under no circumstances did he want to face the prospect of being posted at one of the death-camps in the East, generally seen as punishment among SS officers.20

This double-ness of motives, asynchronicity of coordinated actions and divergence of intended and unintended consequences together manage to create so many separate narrative trajectories, which nonetheless generate unexpected connections and startling intersections. It makes RESPITE an obvious sequel or, rather, supplement to Farocki’s best-known film to date: IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND INSCRIPTION OF WAR. Critics have taken it as such and pointed to some obvious similarities.21 Both films, for instance, share a key date: May 1944. This was the month of the Allied reconnaissance flights over Auschwitz-Birkenau that play such a central role in IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND INSCRIPTION OF WAR, but equally the month in which Breslauer shot his film and the train departed for the selfsame destination of Auschwitz. In addition, IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND INSCRIPTION OF WAR brings together two sets of photographs from apparently different contexts: the US reconnaissance photos, kept for decades in a bureaucratic filing cabinet, as well as the trophy photos of an SS guard, kept in the so-called ‚Auschwitz Album‘, retrieved by accident and also made public only decades later. One set are ‚technical images‘ taken from above, ‚too far‘ and following a grid, through which fell unnoticed the human beings lining up to be killed, and the other set of photos are sentimental keepsakes, taken from ground-level, ‚too close‘ to register the enormity, because they frame views intended for an album of souvenirs (id est future memories), and therefore remain unframed by any moral concern for the here-and-now of context and situation. Each set documents - in spite of itself - that which it did not set out to show: the ‚known unknowns‘ of retrospection. In RESPITE, even though the images belong to one location and one event, the intention and execution are also at odds with each other: the very efficiency of the organization that Gemmeker wanted to present to Berlin is undercut by Breslauer’s meandering and impressionistic footage. While never presented to the gaze of the Big Other in Berlin, the film (which remained unfinished and unscreened) nonetheless “reached its destination,”22 and did serve as a document: redeeming its creator and indicting its instigator. Only when Alain Resnais took charge of the editing and produced the sequence now so often shown did one ‚see‘ the relentless and incriminating ruthlessness of the transports. It brought out Gemmeker’s ‚optical unconscious‘ more directly than Breslauer’s, but in the process it made the Commandant, who all along claimed ignorance of the fate his charges were headed to, condemn himself through his own vanity: „Why did the German camp command even think of making the film? ‚Did they not realize that especially the scenes of the transports would reinforce the abominable image of the system which they served?‘ After the war the films was used as evidence during the trial against Gemmeker; ‚it was evidence that the Nazi themselves had created.‘“23

Finally, both films feature a highly transgressive image: that of a woman, looking at the camera, ‚returning the look‘. In RESPITE, Farocki, faced with the face of ‚het meisje‘, speculates that Breslauer avoided close-ups of the people getting into the trains, out of respect for the victim’s dignity. This is almost as if he was responding to the accusation, already mentioned, voiced about the young woman’s face in IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND INSCRIPTION OF WAR being violated by the camera’s close up. There, Farocki’s hands ‚frame‘ the shot, isolating her gaze, while the voice-over wonders what this gaze might speak of: a woman, aware of her beauty, catching sight for an instance of a man looking at her, stepping out of time and place into an eternal presence, while the other prisoners recede that much further into oblivion and anonymity.

The shot of Farocki’s hands framing the shot has itself become iconic - reproduced on book covers, and making up the DVD-sleeve. Might it be, like the door shutting on ‚het meisje‘, that the hands preserve the sense of presence while also distancing the face, poised and pictured in the moment where imminent death is the condition for the most palpable evidence of life? To me, this framing gesture now suggests also another association: it rhymes with a remark Farocki made many years later, in Montreal, at a conference in October 2007, when after Philippe Despoix’ presentation, the filmmaker commented on an camera advertisement from 1940-1, which suggested that ‚Wehrmacht‘ soldiers should carry one with them to the front, because it would protect them from bullets. Yes, Farocki said, that is actually true, behind a camera I do feel strangely invulnerable.24 An odd sort of relay began to open up for me: perhaps Rudolf Breslauer felt that putting himself behind a camera in the camp gave him, too, some kind of invulnerability or protection from being devoured by the machinery of death;25 Farocki, in turn, had put himself ‚behind‘ the camera of Breslauer, ‚appropriating‘ his predecessor’s eye by respecting the (dis-)order of the material, rather than re-editing it (as Resnais had done). In an act part-homage and part-critique, RESPITE imagines what it must have been like to look at the camp at that moment in time, without the knowledge that hindsight (and scholarly, commemorative or forensic research) has conferred on it since. Found footage film-making as recycling is ‚re-found‘ footage, in Freud’s sense of the word,26 and here mirrors, ‚mise-en-abyme‘ fashion, the recycling which is documented in the film itself. Both serve as delaying tactic: for does not ‚doppelte Arbeit als Aufschub‘ also name and therefore implicate Farocki himself and his method? He too wants to postpone ‚the inevitable‘ - the knowledge of the Holocaust that came after.

Action Replay: The Dead Demand a Re-wind

This special ‚reflexive implication‘ in the subjects of his films had always struck me as one of the outstanding virtues of Farocki’s filmmaking.27 His guiding principle of the ‚Verbund‘ is based on feedback and mutual interdependence, initially born out of economic necessity, he once explained, as much as derived from his own work ethics and politics.28 While thinking further about the link between appropriation and self-implication in RESPITE, I remembered an interview I had done with Farocki in London in 1993, where he mentioned his astonishment that IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND INSCRIPTION OF WAR had, as he put it, „returned to him a different film“ from the one he thought he had made. It went out as BILDER DER WELT UND INSCHRIFT DES KRIEGES, which would have been „Pictures of the World“, and it came back as „Images of the World“. More surprising still, his film was against nuclear energy and about the need to resist, if necessary by direct action, the stationing of atomic weapons on German soil (the controversial NATO-Pershing II missiles); yet IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND INSCRIPTION OF WAR came back - mainly from US university campuses and festivals - as a film about Auschwitz, about ‚mart weapons‘ and ‚war and cinema‘.29 This points to another parallel that links (the reception of) IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND INSCRIPTION OF WAR to (the production of) RESPITE: Breslauer - and Gemmeker - also thought they were making one kind of film, but their material has come down to us with quite a different kind of meaning. Farocki, in other words, has been subject to ‚appropriation‘ himself, thanks to a historical rupture he could not have foreseen (the end of the Cold War, which greatly reduced public concern about atomic weapons), a new kind of warfare and a change in generations among his audience. However beneficial this appropriation might have been to Farocki’s reputation and subsequent career, it is nonetheless plausible to assume that it came as something of a shock, and therefore to consider RESPITE as a film that advances (my first impressions to the contrary) quite a profound and personal reflection on repetition-with-a-difference as well as on the intended, unintended - indeed, on the parapractic - consequences of ‚replay‘.

This would go some way towards explaining the very particular form that recycling, repetition and replay take in RESPITE, namely that of a ‚re-wind‘. Originally a term used to describe the mechanical action of reversing the direction of a roll of magnetic tape or a spool of film, it has (perhaps in direct proportion to its technical obsolescence) taken on metaphoric connotations, meaning the ability to return to an earlier point in time or to a ‚status quo ante‘, in order to proceed, through repetition, on a slightly different path, be it to make something undone, to efface an unwelcome outcome or to start all over again. My argument would be that Farocki, by making a deliberate decision not to present an ‚edition‘ in the philological sense, and therefore not to edit in the cinematic sense (nor to editorialize with a voice-over, in the journalistic sense), tried to re-wind the historical footage for us, both metaphorically and literally: we might imagine that we are seeing the scenes as if for the first time (the trope of ‚discovery‘ of something ‚buried‘ in the archive) or we might assume that the images finally unwind in the spatio-temporal order that Breslauer shot or scripted them, with Farocki adding a minimum of factual information through the intertitles. But then there is a second, literal re-wind. He replays several scenes, now with commentaries that are heavy with the burden of hindsight knowledge: the white coats in the camp’s infirmary recall the gruesome experiments of a Mengele, the stripping of the copper wires anticipate the mountains of female hair and the inmates taking their lunch break in the grass, resting from working the fields, remind us of the sprawled emaciated bodies piled in heaps before bulldozers tip them into mass graves. The effect is to shock us into a double-take: RESPITE is not (yet another film) about the Holocaust; it is about our knowledge of the images of the Holocaust and how the memory of this knowledge (and of these images) has forever altered our sense of temporality and causality, and thus how we ‚see‘ an image from the ‚archive‘. This would be the best reason why Farocki appears to suspend the previous ‚histories‘ of the Westerbork footage.

The dilemma of the Holocaust film, whether fictional or documentary, is that hindsight knowledge inflects our response and all but pre-programs our interest. The narrative arcs are determined in advance: either the storyline is that of a journey into the heart of darkness, meant to discover yet another hidden secret, to pull the mask from “ordinary men” (or women: THE READER (Stephen Daldry, D 2008)) and reveal the “banality of evil” (HÔTEL TERMINUS: THE LIFE AND TIMES OF KLAUS BARBIE (Marcel Ophüls, USA 1988)); or it takes the form of a quest for redemption and atonement (SCHINDLER’S LIST (Steven Spielberg, USA 1993), even one where self-deception and fantasy are the saving graces of an inescapable fate (LA VITA È BELLA (LIVE IS BEAUTIFUL, Roberto Benigni, F 1997)). Such closures come at a price: not only are the Jews depicted as passive victims, deprived of agency, but the known outcome also makes for passive spectators, shifting their attention to the ‚how‘ more than the ‚why‘. The typical pathos of melodrama - that recognition always comes ‚too late‘ - is accentuated by the response we normally associate with another genre: in the Holocaust film, we want to warn the protagonists, as in the horror movie, and shout „Watch out, you’re in imminent danger, turn around, the monster is right behind you.“ This is especially palpable a feeling one has with the train sequence that has made the Westerbork material famous, but our stifled shouts would never reach them, and our knowledge will forever be of no use to them.

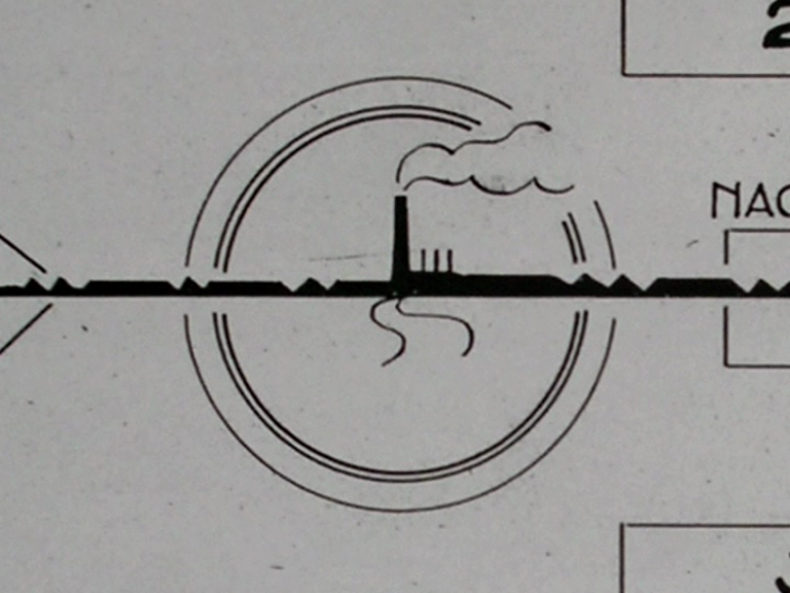

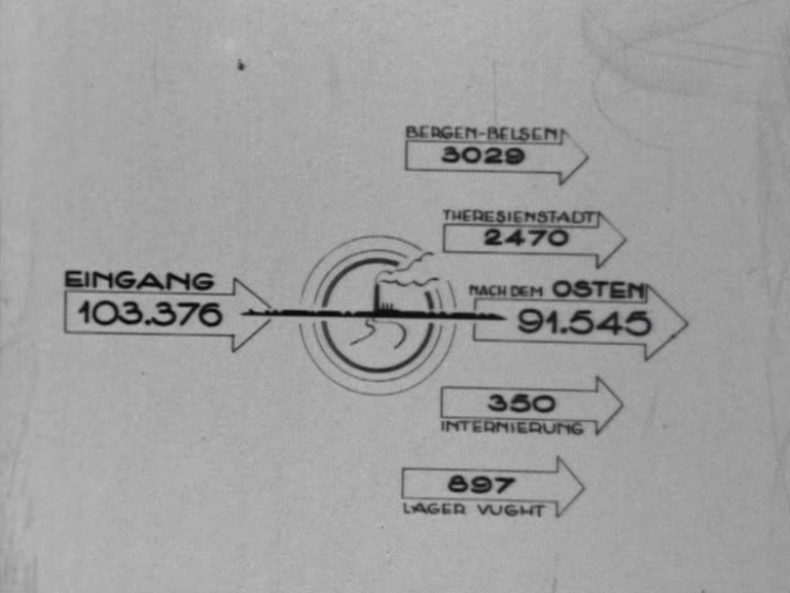

Farocki’s counter-strategy, as I see it, is to try and return some of this knowledge (in both its expectations and anticipations) to a point-zero: hence the re-wind. Not to erase the knowledge or even to wish it undone (the desperate emotion of melodrama), but to give our train-of-thought another direction. For this he has to take a further step; instead of melodrama (the pathos of ‚if only they knew‘), the thriller (the suspense of superior knowledge) or the horror film (the agony of anticipated, but inevitable, disaster) he foregrounds an altogether different genre, that of the ‚industrial film‘. It is a bold move, fraught with its own kinds of pitfall. First, RESPITE resembles the industrial film in its subject-matter: it shows the transit camp organized like a factory, and Farocki makes much of Westerbork’s unique camp logo, with its factory chimney and barracks set in a circular frame. As we saw, this is part of the ‚intention‘ of the original footage, one where Breslauer and Gemmeker’s objectives converged. The medical, recreational and educational facilities grouped around the “production site” are furthermore modelled on well-known experiments in planned work/life communities, implemented in such ‚company towns‘ as Eindhoven in the Netherlands (Philips), Zlin in the Czech Republic (Bata) or Wolfsburg in Germany (VW). Second, the industrial film (one of the oldest genres of the cinema) has a clear trajectory: it progresses by separate steps and consecutive processes from raw materials to finished products (“progress through process”). While Gemmeker’s ‚Westerbork camp‘ prided itself on ‚processing‘ almost 100,000 internees from ‚West‘ to ‚East‘ (graphically represented with arrows going from left to right on a chart drawn up for Gemmeker and filmed by Breslauer), the ‚Westerbork film‘ wanted to demonstrate that it was productively useful, this time not by making finished products, but by recycling redundant products and turning them back into raw materials. In other words, this was an industrial film in reverse, a re-wind, reminiscent of one of the earliest rewinds in film history,30 but also a devastating representation on the part of the camp inmates of themselves as ‚useful waste‘: another reflexive self-implication on the part of Farocki’s film, whose condition of possibility is the very ‚mise-en-abyme‘ of the different kinds of recycling thus instantiated.

It brings me to the third high-wire moment: the argumentative schema of an industrial film ‚in reverse‘ unsettles the conventional narrative of the Holocaust film, but at the same time reinforces it at another level, confirming our other knowledge about the camps: that they were deliberately or cynically organized according to industrial principles, whose raw materials were living human beings, either worked to death or treated as organic matter to be processed for profit. Our hindsight (and Farocki’s) necessarily ‚sees‘ in the metaphoric chimney of the Westerbork logo the all-too-real chimneys of the crematoria in Auschwitz, Gross-Rosen or Majdanek.

If fraught with pitfalls, the explicit references to the industrial film also yield unexpected possibilities: Farocki’s minimal ‚Verfremdung‘ of the material, thanks to (in this instance) an especially poignant genre, returns us to another point zero. Because of the particular ‚logics of the re-wind‘ just indicated, one is poised on the tip of several reversals, potentially liberated from the passive position of merely being spectators of the ‚inevitable‘ (those arrows pointing left to right). From this new point zero, the Westerbork footage reveals yet another side, another hindsight: that of the genre which most likely was on Breslauer’s mind (along with the industrial film) when he set up his scenes. The memory of the ‚Russenfilme‘ haunts the Westerbork footage, not in form or technique (we shall never know how Breslauer would have edited the material, nor what Gemmeker would have made of it), but in the idealizing pathos of collective work, communal living and the tilling of the soil. Images from Eisenstein, Pudovkin or Vertov emerge like watermarks into visibility, adding one more kind of ‚optical unconscious‘ to the film that counters the ‚optical unconscious‘ of the industrial organization of murder, already alluded to. Relativizing not the reality of the camp but ‚historicizing‘ its images, Farocki prompts us to a revision and a rethink of what has so far prevented the majority of the footage to be shown: namely, that these scenes of everyday life, of sports and recreation either did not fit the conventionalized Holocaust narrative or seemed too unbearably ironic in their innocence and ignorance. The re-wind restores ignorance and preserves innocence of another kind: it suggests that the camp’s activities can be seen as heroic, because documenting moments of ‚normalcy‘ that the inmates were able to wrest from their fate. In fact, they testify to the determination to live and organize one’s life - one’s conduct and one’s manners - in a dignified way, even in circumstances that are anything but normal, dignified or civilized.

An Epistemology of Forgetting?

Paul Ricœur - echoing here the historiography of Jules Michelet - once argued that part of the historian’s duties is not only to let the dead render their testimony, but to give back to the past its own future: „Considered as dialectic of origin (‚arché‘) and destination (‚telos‘), the regime of historicity is entirely steeped in tension between the space of experience and the horizon of expectation.“31

To give back to the past its own future: this may have been the challenge that Farocki faced in RESPITE, and for which he had to find the appropriate aesthetic form. The problem is not so much hindsight knowledge per se (how can we not view the past from the present?), but that in this instance, and after more than three decades of Germany’s intense preoccupation with its recent history, we think we know too much about the Holocaust. It forecloses the possibility of new knowledge (other than in the genres of ‚discovery‘, ‚pathos‘ and ‚irony‘ discussed above), and thus invites the very forgetting that Holocaust memorialization is meant to prevent. The danger is that there seems nothing to learn other than the misleadingly tautological mantra ‚never again‘: tautological, because the past will not repeat itself, and misleading because the ‚concentrationary‘ mindset is still very much with us.32 Hence the pedagogic value of repeating the past by way of RESPITE’s ‚rewind and replay‘, by trying to locate the points where the past may have had - within its present - also a future, one that is not necessarily our present. Such efforts of the moral imagination may be dismissed as „counterfactual history“,33 but this is precisely where Farocki’s politics of minimal interference pays maximum dividends: instead of indulging in the ‚what-if‘’s of alternative universes, his splicing of black leader and spacing of laconic intertitles creates the necessary gaps - ‚the respites‘ - into which spectators may insert their own ‚Holocaust memories‘, be they media images, film narratives, history books or civic lessons.

Farocki’s gaps, in other words, engender a kind of forgetting that should not or need not be filled with more evidence or forensic investigation. If the internees’ respites are meant to delay and defer the relentless logic of the weekly transports, the filmmaker’s respites are meant to forestall the relentless logic of automatically attributed meaning, in the belief that such lapses or gaps of recall may make room for the accidental and the unexpected, in the very midst of such murderous causality and consequentiality. Forgetting, in the sense of ‚Ausblendung des Vorwissens‘ (screening out pre-existing knowledge) would thus be neither an attempt at “becoming innocent” nor a slide into denial and disavowal, but might carve out that impossibly possible space between the ‚known knowns‘ (of historical scholarship) and the ‚known unknowns‘ (of future research), but also intervene between the “unknown knowns” (of what we prefer to ignore) and the ‚unknown unknowns‘ (of what this past might one day mean for us).

RESPITE thus returns to the Westerbork past not exactly its future (cruelly taken from so many thousands of human beings), but its lacunary present, creating out of Breslauer’s images and Gemmeker’s narrative a history with holes, so to speak—once more open, without being open-ended. Into the claustrophobic world of Holocaust memory, he cuts the breathing room that re-invests the history of Westerbork with the degrees of contingency and necessity, of improbability and unintended consequences, that serve as a ‚counter-music‘ to the relentlessness of the destruction machine that the extracted footage of the transports has so vividly bequeathed to us. No mean feat, if we think about it, not least because achieved with so little intervention, yielding a kind of knowledge that only a certain courage of forgetting can give us.

- 1Paul Ricoeur, Memory, History, Forgetting, trans. Kathleen Blamey and David Pellauer (Chicago 2004), 166.

- 2“Noch etwas: kennst Du zufällig jemanden, der über den Film „Westerbork“ gearbeitet hat? Wahrscheinlich weisst Du das: so wie der Film über Theresienstadt wurde auch dieser von einem Deportierten aufgenommen. Eine recht lange Sequenz kommt in „Nuit et bruillard“ schon vor. Ich denke, etwas dazu zu machen. In dem Film, der aus ziemlich rohem Material besteht, wird sehr ausführlich die Arbeit gezeigt, die die Häftlinge machen. Es heisst, jeder versuchte, in W. zu bleiben, vielleicht nicht, weil bekannt war, was es bedeutete, von dort „zu einem Arbeitseinsatz im Osten“ abfahren zu müssen, sondern nur, weil es dort zu essen gab. Die dort arbeiten, versuchen den Eindruck zu erwecken, sie täten etwas wichtiges („Kriegswichtig“) und der Film selbst ist auch umständlich, um die Gegenwart auszudehnen. Doppelte Arbeit als Aufschub.” Harun Farocki, e-mail correspondence with the author, October 9, 2006.

- 3Aad Wagenaar, Settela, trans. Janna Eliot (Nottingham 2005).

- 4Thomas Elsaesser, “One Train May Be Hiding Another: Private History, Memory and National Identity,” Screening the Past (April 16, 1999), accessed February 25, 2015, http://tlweb.latrobe.edu.au/humanities/screeningthepast/reruns/rr0499/t….

- 5First appeared as “Holocaust Memory as the Epistemology of Forgetting? Re-wind and Postponement in respite,” in Harun Farocki: Against What? Against Whom?, ed. Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun (London 2009), 57–68.

- 6A review, originally reproduced on Farocki’s website, erroneously credits Farocki with the discovery: “The surviving, mostly unedited footage and Farocki's silent intertitle commentary is ambiguous despite the simplicity of content and the surprising specificity of the filmmaker's research – from a barely visible stamp on a suitcase the titles identify not only the person in the image, but the specific date the footage was taken as well as the woman's place and date of death.” When I pointed this out, Farocki replaced the text with one by Sylvie Lindeperg, „RESPITE,“ film 101, accessed February 25, 2015, http://www.harunfarocki.de/films/2000s/2007/respite.html.

- 7“Harun Farocki has used found footage in innovative ways throughout his career challenging dominant political perspectives with a simple common sense approach to the world. His films are sometimes almost untouched appropriations and others deeply nuanced assemblages that find incredible connections between disparate source materials. He is a humane, empathetic and serious found footage filmmaker who unlike his colleagues has created uncynical films that speak truth to power without being self-righteous.” Eli Horwatt, “Harun Farocki and the Politics of Found Footage with William Burroughs on Cut-Ups,” The Recycled Cinema (2008), accessed February 25, 2015, http://recycledcinema.blogspot.com/2008/01/harun-farocki-politics-of-fo….

- 8In a later e-mail, Farocki mentions a brochure he bought at the Westerbork memorial site: this must be Koert Broersma and Gerard Rossing, Kamp Westerbork gefilmd: Het verhaal over een unieke film uit 1944 (Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork 1997).

- 9Cf. Sylvie Lindenperg, “Filmische Verwendungen von Geschichte: Historische Verwendungen des Films,” in Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit: Dokumentarfilm, Fernsehen und Geschichte, ed. Eva Hohenberger and Judith Keilbach (Berlin 2003), 65–81. Part of her work on NUIT ET BROUILLARD was first published in “NUIT ET BROUILLARD: Récit d'un tournage,” L’Histoire 294 (2005), and subsequently published in book form nuit et brouillard: Un film dans l’Histoire (Paris 2007). Lindenperg is able to identify the different interpolations made by Resnais, as well as how he edited the Westerbork footage.

- 10See Nora Alter, “The Political Im/perceptible,” in Harun Farocki: Working on the Sight-Lines, ed. Thomas Elsaesser (Amsterdam 2005), 219 and footnote 27. Kaja Silverman, also commenting on this critique, mounts a spirited defence of Farocki’s procedure in “What Is a Camera?, or: History in the Field of Vision,” Discourse 15.3 (1993): 39–42.

- 11Cherry Duyns’ film was shown at the International Documentary Film Festival in November 1999, in a special programme The Memory of the 20th Century. “Neem Settela, gezicht van het verleden, een VPRO-documentaire van Cherry Duyns uit 1994. In deze film volgt Duyns de journalist Aad Wagenaar, die op zoek ging naar de identiteit van het meisje met de witte hoofddoek in een treinwagon, vastgelegd op het moment dat de trein Westerbork verliet. Het anonieme meisje werd een symbool voor de Nederlandse joden die via Westerbork naar Duitse kampen werden afgevoerd. Analyse van de film waar de foto uit afkomstig is, toont echter aan dat met de betreffende trein zigeuners werden vervoerd. Het meisje krijgt een naam en Duyns bezoekt overlevenden die haar kennen uit de vooroorlogse zigeunergemeenschap in Limburg. Is het niet jammer dat de mythe is verdwenen nu het meisje een naam heeft gekregen, vraagt Duyns aan het einde van zijn film aan Wagenaar. Een beetje wel, bevestigt deze, maar het beeld blijft een aanklacht. Sterker nog: dankzij de debunking van Wagenaar en Duyns is het beeld van het meisje met de hoofddoek eerder versterkt dan verzwakt.” (“Take Settela, face of the past, a VPRO documentary of Cherry Duyns from 1994. In this movie Duyns follows the journalist Aad Wagenaar, who is searching for the identity of the girl with the white headscarf in the train wagon, photographed on the moment that the train leaves Westerbork. The anonymous girl became the symbol for the Dutch Jews who were transported to German camps via Westerbork. Analysis of the movie, where the photo is originally from, however shows that with this particular train gypsies were transported. The girl gets a name and Duyns visit survivors who know her from the pre-war gypsie society in Limburg. Isn't it a pity that the myth disappeared now the girl has got a name, Duyns asks Wagenaar at the end of his movie. A little bit yes, he confirms, but the image remains an accusation. In fact: thanks to the exposition of Wagenaar and Duyns, the image of the girl with the headscarf is reinforced in stead of weakened.” Transl. T.D.) Mark Duursma, “Versleten beelden niew leven inblazen,” NRC Handelsblad, November 18, 1999.

- 12On the camp commandant Albert Konrad Gemmeker (Düsseldorf 1907–1982), see “A.K. Gemmeker,” The Holocaust – Lest We Forget (2009), accessed March 3, 2015, http://www.holocaust-lestweforget.com/albert-konrad-gemmeker.html. On Rudolf Breslauer (Munich 1904–Auschwitz 1944) see “Robert Breslauer,“ Wikipedia, accessed March 3, 2015,http://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rudolf_Breslauer.

- 13The literature on the dilemmas of the “Judenräte” and Jewish “Ordnungdienste” is extensive, but—from an ethical perspective—still inconclusive. See David H. Jones, Moral Responsibility in the Holocaust: A Study in the Ethics of Character (Lanham et al. 1999). For a summary of the debates about the ownership of the gaze of the photographic records of World War II atrocities and genocide, see Marianne Hirsch, “Surviving Images: Holocaust Photographs and the Work of Postmemory,” Yale Journal of Criticism 14:1 (2001): 5–37; Susie Linfield, “A Witness to Murder,” Boston Review (2005), accessed March 3, 2015, http://bostonreview.net/BR30.5/linfield.php; and—about a single image—Richard Raskin, A Child at Gunpoint: A Case Study in the Life of a Photo (Aarhus 2004).

- 14“De Westerborkfilm is de enige realistische kampfilm uit de tweede wereldoorlog en daarom ontelbare keren gebruikt voor documentaires, in de gehele wereld.” (“The Westerbork film is the only realistic camp film out of WWII and therefor it was used innumerous times for documentaries in the whole world.” Transl. T.D.) On April 9, 2000, the Dutch television channel VPRO devoted a special programme of Andere Tijden to Gemmeker, under the title “De vorige commandant trapte de joden naar Polen, deze lacht ze naar Polen.” (“The former commander kicked the Jews to Poland, this one laughs them to Poland.” Transl. T.D.) Besides extracts from the Breslauer film, an extensive website gives further information about the commandant and his life (accessed March 3, 2015): http://www.npogeschiedenis.nl/dossiers/Gemmeker-Albert-Konrad-1907-1982….

- 15Besides One Train May be Hiding Another, I touch on the fate of these Westerbork images in two more essays: “Vergebliche Rettung: Geschichte als Palimpsest,” in Konrad Wolf: Werk und Wirkung, ed. Michael Wedel and Elke Schieber (Berlin 2009), 73–92, and “Migration und Motiv: Das parapraktische Gedächtnis eines Bildes” in Nachleben und Rekonstruktion: Vergangenheit im Bild, ed. Peter Geimer and Michael Hagner (Munich 2012), 156–176.

- 16I am here “appropriating“ the much-quoted pronouncement made by Donald Rumsfeld at a press briefing given as US Defense Secretary on February 12, 2002, but I refrain from adding Slavoj Žižek’s “known unknowns”—“the knowledge that doesn’t know itself”—although this, too, may have a role to play (cf. Slavoj Žižek, “What Rumsfeld Doesn’t Know That He Knows About Abu Ghraib” [2004], accessed March 3, 2015, http://www.lacan.com/zizekrumsfeld.htm).

- 17Especially if we remember “Arbeit macht frei, ” the wrought-iron phrase over the gates of Auschwitz and other concentration camps, cf. “Arbeit macht frei,” Wikipedia, accessed March 3, 2015, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arbeit_macht_frei.

- 18Harun Farocki, e-mail correspondence with the author, October 9, 2006.

- 19For a detailed account of the background and making of THERESIENSTADT – EIN DOKUMENTARFILM AUS DEM JÜDISCHEN SIEDLUNGSGEBIET (D/CZE 1944), see Karel Margry, “Das Konzentrationslager als Idylle,” in Auschwitz: Geschichte, Rezeption und Wirkung, ed. Fritz Bauer Institut (Frankfurt 1996), 319–352.

- 20“Een theorie is dat Gemmeker de film heeft laten maken om indruk te maken bij zijn superieuren en zo overplaatsing naar het Oostfront te voorkomen. ‘Algemeen wordt aangenomen dat Gemmeker met de film zijn bazen in Berlijn wilde overtuigen van het aandeel dat kamp Westerbork kon hebben in de oorlogsproductie voor Duitsland. Het industriële belang van het kamp was tevens het eigenbelang van de kampcommandant zélf. Zolang Westerbork als Kriegswichtig voor de Duitse oorlogsindustrie was aangemerkt, zou het hachje van Gemmeker zijn gered.’” (“A theory is that Gemmecker ordered to make the film to impress his superiors in order to prevent a translocation to the Eastern Front. ‘It is broadly assumed that with the film Gemmeker wanted to convince his chiefs in Berlin of the contribution that camp Westerbork could make to Germany’s war production. The camp’s industrial interest also was the interest of the camp commander himself. As long as Westerbork was considered as kriegswichtig for German war industry, Gemmeker saves his own skin.’” Transl. T.D.) Han van Bessel, “Onvergetelijke filmbeelden,” de Volkskrant, April 25, 1997. The first historical research on Gemmeker and Breslauer’s film can be found in one of the standard works of Dutch historiography, Jacques Presser, De Ondergang (Nijhoff 1965), 328–332.

- 21See Sylvie Lindeperg, “respite: vies en sursis, images revenants,” Trafic 70 (2009): 25–32; Philippe Despoix, “Travail/sursis: delai sans remission,” Intermédialités 11 (2008): 89–94.

- 22I am here alluding to Jacques Lacan’s seminar on Edgar Allan Poe’s The Purloined Letter, translated by Jeffrey Mehlman and published in Yale French Studies 48 (1972): 38–72.

- 23“. . . waarom heeft de Duitse kampleiding de film überhaupt laten maken? ‘Besefte deze niet dat vooral de scènes van de transporten het gruwelijke beeld van het systeem dat zij dienden, zouden versterken?’ De film werd na de oorlog gebruikt als bewijsmateriaal tijdens het proces tegen Gemmeker; ‘het was bewijsmateriaal dat de nazi's zélf hadden gecreëerd.’ (“. . . why ordered the German camp direction to make the film anyway? ‘Didn’t they realize that in particular the transport scenes would reinforce the cruel image of the system they serve?’ After the war, the film will be used as evidence in the process against Gemmeker; ‘this was evidence that the Nazis created themselves.’” Transl. T.D.) Broersma and Rossing, quoted in Han van Bessel, “Onvergetelijke filmbeelden.”

- 24Farocki repeated the remark in an interview given to Hors Champs: “Harun Farocki: Hier, à la conférence, Philippe Despoix nous a montré cette réclame allemande des années 40–41, qui expliquait que l'appareil photographique pouvait vous protéger sur le front. Achetez une caméra, et vous serez protégé des balles! Et bien entendu, c'est en grande partie vrai. J'ai connu cette expérience. Nous étions une fois dans un zoo, et nous filmions un tigre, non pas un tigre en cage, mais en liberté. Derrière la caméra, vous n'aviez plus peur!” André Habib and Pavel Pavlov, “D'une image à l'autre: conversation avec Harun Farocki,” Hors champs, December 20, 2007, accessed March 3, 2015, http://www.horschamp.qc.ca/spip.php?article290.

- 25Breslauer’s position behind the camera was a tragically illusory invulnerability, as he was to be one of the last deportees, sent to Auschwitz by Gemmeker in September 1944, barely four months after he shot the film. For additional information and an extract from the Westerbork film on the internet, see (accessed March 3, 2015): http://www.auschwitz.nl/paviljoen/deportatie/westerbork-1942-1944/bresl….

- 26“Every finding of an object is in fact a re-finding of it.” Sigmund Freud, “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality and other Writings (1901–1905),” Standard Edition, vol. 7 (London 1953), 222.

- 27“Farocki takes up a subject only when it can be presented as a mise-en-abyme of the world, mirrored in his own work: as a feedback system, in other words, but asymmetrical and asynchronous, rather than closed and self-regulating . . . His films have moral authority and aesthetic credibility only to the extent that their reflexivity cuts both ways: that it is directed also at the director himself, and that the feedback loop must implicate the artist, [creating] moments that re-instate the eye and the hand as instances of self-implication and solidarity. The true topicality and urgency of Farocki’s work may thus be nothing less than that it is an effort to rescue the cinema from its own dialectic of memory and forgetting, of nostalgic evocation of lost reference and modernist self-reflexivity.” Thomas Elsaesser, “The Future of Art and Work in the Age of Vision Machines: Harun Farocki,” in After the Avantgarde: Contemporary German and Austrian Experimental Film, ed. Randall Halle and Reinhild Steingröver (Rochester 2008), 47f.

- 28Cf. Harun Farocki, “Notwendige Abwechslung und Vielfalt,” Filmkritik 224 (1975): 360–9. On self-implication and the idea of “Verbund,” see Thomas Elsaesser, “Harun Farocki: Filmmaker, Artist, Media Theorist,” in Elsaesser, ed., Harun Farocki, 32–6.

- 29T.E., “‘Making the World Superfluous’: An Interview with Harun Farocki,” in Elsaesser, ed., Harun Farocki, 185. What had intervened between the making of the film, which took several years, and its reception by a wider public, was the end of the Cold War, and the fall of the Wall: the atomic threat receded, just as “Auschwitz” returned as an abiding preoccupation of the next decade. The film opened in the United States almost simultaneously with the first Gulf War, which gave the film an additional topical relevance and the conflict a historical depth, neither of which the filmmaker could have anticipated, but which henceforth “belong” to the film.

- 30The Lumière brothers’ DÉMOLITION D’UN MUR (DEMOLITION OF A WALL, F 1896) was habitually shown twice, first forward and then in reverse, with the wall once more rising from its own ashes. See “Demolition of a wall,” Docs Online, accessed March 3, 2015, https://docsonline.tv/demolition-of-a-wall/.

- 31„Pris dans une dialectique de l'arché et du télos, le régime d'historicité est tout entier traversé par la tension entre espace d'expérience et horizon d'attente.” (Trans. T.D.) Paul Ricoeur, Du texte à l’action (Paris 1986), 391. Ricoeur is here echoing Reinhart Kosellek and his notion that memory is always constituted by the tension between an “Erlebnisraum” and an “Erwartungshorizont.”

- 32See, for instance, Zygmunt Bauman, Wasted Lives: Modernity and its Outcasts (Cambridge 2004).

- 33For an argument of the positive uses of counterfactual history, see Niall Ferguson, ed., Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals (London 1977).

Alter, Nora. “The Political Im/perceptible,” in Harun Farocki: Working on the Sight-Lines, ed. Elsaesser, Thomas (Amsterdam 2005).

Bauman, Zygmunt. Wasted Lives: Modernity and its Outcasts (Cambridge 2004).

Bessel, Han van. “Onvergetelijke filmbeelden,” de Volkskrant, April 25, 1997.

Broersma, Koert / Rossing, Gerard. Kamp Westerbork gefilmd: Het verhaal over een unieke film uit 1944 (Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork 1997).

Despoix, Philippe. “Travail/sursis: delai sans remission,” Intermédialités 11 (2008).

Duursma, Mark. “Versleten beelden niew leven inblazen,” NRC Handelsblad, November 18, 1999.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “‘Making the World Superfluous’: An Interview with Harun Farocki,” in Elsaesser, Thomas ed., Harun Farocki.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Harun Farocki: Filmmaker, Artist, Media Theorist,” in Elsaesser, Thomas ed., Harun Farocki.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Holocaust Memory as the Epistemology of Forgetting? Re-wind and Postponement in RESPITE”. In: Harun Farocki. Against What? Against Whom?, ed. Ehmann, Antje / Eshun, Kodwo (London 2009).

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Migration und Motiv: Das parapraktische Gedächtnis eines Bildes” in Nachleben und Rekonstruktion: Vergangenheit im Bild, ed. Geimer, Peter / Hagner, Michael (Munich 2012).

Elsaesser, Thomas. “One Train May Be Hiding Another: Private History, Memory and National Identity,” Screening the Past (April 16, 1999), accessed February 25, 2015, http://tlweb.latrobe.edu.au/humanities/screeningthepast/reruns/rr0499/t….

Elsaesser, Thomas. “The Future of Art and Work in the Age of Vision Machines: Harun Farocki,” in After the Avantgarde: Contemporary German and Austrian Experimental Film, ed. Halle, Randall / Steingröver, Reinhild (Rochester 2008).

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Vergebliche Rettung: Geschichte als Palimpsest,” in Konrad Wolf: Werk und Wirkung, ed. Wedel, Michael / Schieber, Elke (Berlin 2009).

Farocki, Harun. “Notwendige Abwechslung und Vielfalt,” Filmkritik 224 (1975).

Ferguson, Niall ed.. Virtual History: Alternatives and Counterfactuals (London 1977).

Freud, Sigmund. “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality and other Writings (1901–1905),” Standard Edition, vol. 7 (London 1953).

Habib, André / Pavlov, Pavel. “D'une image à l'autre: conversation avec Harun Farocki,” Hors champs, December 20, 2007, accessed March 3, 2015, http://www.horschamp.qc.ca/spip.php?article290.

Hirsch, Marianne. “Surviving Images: Holocaust Photographs and the Work of Postmemory,” Yale Journal of Criticism 14:1 (2001).

Horwatt, Eli. “Harun Farocki and the Politics of Found Footage with William Burroughs on Cut-Ups,” The Recycled Cinema (2008), accessed February 25, 2015, http://recycledcinema.blogspot.com/2008/01/harun-farocki-politics-of-fo….

Jones, David H.. Moral Responsibility in the Holocaust: A Study in the Ethics of Character (Lanham et al. 1999).

Lacan’s, Jacques. “Seminar on The Purloined Letter“. Trans. Mehlman, Jeffrey. In: Yale French Studies 48 (1972).

Lindenperg, Sylvie. “Filmische Verwendungen von Geschichte: Historische Verwendungen des Films,” in Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit: Dokumentarfilm, Fernsehen und Geschichte, ed. Hohenberger, Eva / Keilbach, Judith (Berlin 2003).

Lindenperg, Sylvie. “NUIT ET BROUILLARD: Récit d'un tournage,” L’Histoire 294 (2005).

Lindenperg, Sylvie. NUIT ET BROUILLARD: Un film dans l’Histoire (Paris 2007).

Lindeperg, Sylvie. “RESPITE: vies en sursis, images revenants,” Trafic 70 (2009).

Lindeperg, Sylvie. „RESPITE,“ film 101, accessed February 25, 2015, http://www.harunfarocki.de/films/2000s/2007/respite.html.

Linfield, Susie. “A Witness to Murder,” Boston Review (2005), accessed March 3, 2015, http://bostonreview.net/BR30.5/linfield.php.

Margry, Karel. “Das Konzentrationslager als Idylle,” in Auschwitz: Geschichte, Rezeption und Wirkung, ed. Fritz Bauer Institut (Frankfurt 1996).

Presser, Jacques. De Ondergang (Nijhoff 1965).

Raskin, Richard. A Child at Gunpoint: A Case Study in the Life of a Photo (Aarhus 2004).

Ricoeur, Paul. Du texte à l’action (Paris 1986).

Ricoeur, Paul. Memory, History, Forgetting, trans. Blamey, Kathleen / Pellauer, David (Chicago 2004).

Silverman, Kaja. “What Is a Camera?, or: History in the Field of Vision,” Discourse 15.3 (1993).

Vanderwerff, Hans / Soeters, Sion. “A.K. Gemmeker” The Holocaust – Lest We Forget (2009), accessed March 3, 2015, http://www.holocaust-lestweforget.com/albert-konrad-gemmeker.html.

Wagenaar, Aad. Settela, trans. Janna Eliot (Nottingham 2005).

Žižek, Slavoj. “What Rumsfeld Doesn’t Know That He Knows About Abu Ghraib” [2004], accessed March 3, 2015, http://www.lacan.com/zizekrumsfeld.htm.