Image Migration and History

The End of the Chilean Military Dictatorship in Pablo Larraín's Feature Film NO!

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: González de Reufels, Delia: Image Migration and History: The End of the Chilean Military Dictatorship in Pablo Larraín's Feature Film NO!. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14793.

Introduction

Almost twenty-five years after the end of the Chilean military dictatorship had been initiated with a national referendum, the feature film NO / NO! (CHL / USA / F 2012) by the Chilean director Pablo Larraín re-opened the discussion about the referendum and its long-term consequences.1 Like all the feature films that addressed the issue of the military dictatorship, which lasted sixteen years under Augusto Pinochet, NO! also had to confront numerous existing media images and the memories of that time, which are coded acoustically. And indeed, Larraín, who based his film on an unpublished play by the Chilean author Antonio Skármeta, found a way to deal with these images, which, in keeping with academic art and film studies on the “migration of images”, will be termed 'image migration' for the purpose of this article and made fruitful for historical analysis.2

The process of image migration plays an outstanding role in the feature film NO!, for it characterises the narrative flow, determines the aesthetic style and is indispensable for the message conveyed, which is why this feature film will be examined in detail here as an example of the migration of images and its effects. This process, which is being used more frequently now, and not only by Chilean directors, has photographs and archival footage “migrate” from the time presented into feature films, in other words they are integrated specifically as historical images and sounds. It is one of the basic assumptions of this essay that this is done in order to arouse associations with existing images of recollection and to give the films greater credibility or authenticity,3 and, at the same time, with the intention of placing the shown historical events and processes in new contexts by using historical media images and films or excerpts from them. In this way they are not only narrated differently but also differently evaluated. This occurs inevitably, due to the feature film’s presence, illuminating past events and processes and at the same time making a statement about the time in which the film itself was made and the political and social contexts in which it was made. As – at least potentially – a new historical narration or even a counter-narration, the films about the Chilean dictatorship that are realised with the means of image migration are of particular interest, for, according to the interpretation followed here, image migration serves not only to reprocess the past in the media in greater proximity to the images of collective memory but also to comment critically on the most recent history and the ways it is understood.

Significantly, in many cases the directors who make use of image migration are those who have little or no personal experience of the military dictatorship because they were too young to do so. They are the Chilean 'post-dictatorship' generation,4 which can in fact no longer include the director Pablo Larraín, who was born in 1976, but for whom the years of dictatorship are similarly a “puzzle” and whose “silent, strange atmosphere” he wants to capture in his films in order to better understand it.5 Until now this approach has led to three works on the subject,6 which rank among the series of recent films about the dictatorship in Chile7 and make a contribution to memory and the work of recollection. The political scientist Alison Brysk insists that the latter is necessary in order to overcome the experience of dictatorship or for society as a whole to recover from it, for: “Recovery begins with memory […]”.8 This regeneration through memory with the employment of familiar images of recollection or through the provision of historical media images in new contexts is one of the characteristic qualities of recent films about the Chilean military dictatorship. In the case of NO!, in calling for a debate on the present, this memory work goes beyond that, because here – as is to be shown later – a double image migration comes into view. The appeal to a critical revaluation of the present by means of an historical feature film also reveals the political dimension of NO!, which suggests the political attitude of Latin American films in general.9 This political attitude is underlined by image migration here; however, it has also caused the director to be accused of distorting the historical processes in an ahistorical way.10

And yet NO!, on the one hand, uses historical footage to convey the history of the campaign that was to bring Chileans into the voting booth and lead to a rejection of any continuation of the dictatorship in the plebiscite of 5 October 1988. Its images and sounds are consequently at the centre of the film. On the other hand, the history of the campaign is rewritten with the use of pictures that have been little noticed until now and a statement is made on the character and consequences of the referendum. How image migration can help to bring Chilean past and present into contact with each other and why this process is important from the point of view of historical study is at the centre of the present essay, which is deliberately located at the intersection of history and film, an uncomfortable location for historians in terms of both method and content.

Consequently this essay will not be a matter of seeing whether the feature film adequately presents the historical events, and neither should it be seen exclusively as a document for the appropriation of history in present-day Chile, even though these approaches are doubtless anchored in historical research into feature films.11 Gertrud Koch, for example, has stated that “whenever historians begin to refer to films they try to treat them as documents”. According to Koch, this happens with the justified mistrust of a discipline that has increasingly been enlightened about itself and is aware of the “ambiguous” relationship between film and history.12 This statement continues to apply today with full force not only to German historical studies.13 At the same time, historians are also conscious of the “power of images” and the significance of visual culture for the study of history,14 as it is underlined not least by the use of historical photographs and moving images in historical or period films, which undertake to “fictionalise history within an historically accredited framework” and in this way bring historical themes and content to a popular audience.15

That this can also be done with the intention of bringing out the current impacts of historical processes can be shown with the example of the film NO! This film attracted great interest internationally but it was in particular an extraordinary success with audiences in Chile. That was also true of the eponymous four-part television series into which the feature film was edited with the addition of further archival footage from the time of the referendum.16 It can therefore be assumed that the success of the miniseries depended to a considerable extent on the process of image migration. Re-seeing as well as rediscovering the moving images of 1988 possibly added to the attractions of a feature film that presented the recent past of Chile in a way that blurred the boundaries between past and present.

The next section will examine the significance of the images from the beginning and end of the dictatorship in Chile and the forms and origins of image migration in film, followed by a closer study of this process and its effects on the basis of the feature film NO!.

Thoughts on the significance of image migration: media images and films from the beginning and end of the dictatorship in Chile

The way the dictatorship, which was euphemistically termed “protected democracy” by the military, began is very present to all people of Chile.17 In this connection the footage of the putsch of 11 September 1973 and of the presidential palace, La Moneda, in flames have remained firmly in the memories of surviving witnesses and are also used repeatedly in films.18 The images have been distributed through modern mass media, have been frequently copied and constantly reproduced. Thus television pictures and photographs of the military coup have replaced other images of recollection, shaping the Chileans’ view of history as 'postmemory' and overwriting other memories, especially for those born after the events, such as oral and written testimonies conveyed by contemporary witnesses.19 In “the Age of Repetition”, as Eco describes postmodern aesthetics, which is defined by seriality and quotation, these images have attained the status of icons,20 which is possibly not least the result of the critical retrospective view of the “ages of darkness”, to quote a work by Marcos Roitman Rosenmann.21

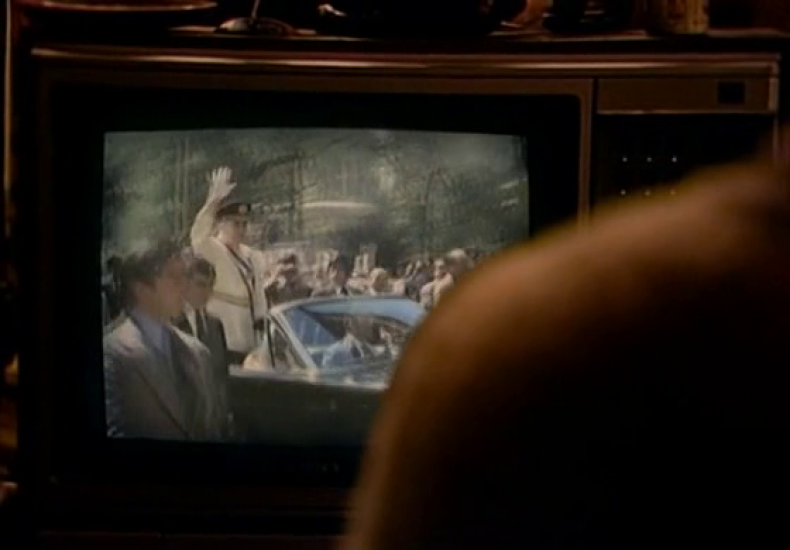

After all, the pictures were at the beginning of the subsequent “war” conducted by the military against its own people.22 From the point of view of the dictatorship that followed, the burning palace anticipates the routine violence of the military regime and also stands for many characteristic features of the dictatorship: for the persecution of political dissidents, which already began in September 1973, for human rights violations and for state terrorism to an unimaginable extent, even going beyond national borders.23 These developments were accompanied by a no less violent restructuring of the political, economic and social order of Chile, which is also taken up in NO! This so-called “shock therapy” introduced neoliberalism into Chile with the help of a group of young Chilean technocrats and founded the myth of the Chilean economic miracle, which, however, began to pale in the early 1980s and from then was to have a destabilising effect on the system.24 In addition to consumerism, which is also addressed in NO!, the military authorities also ordered a mass culture oriented towards the USA and enforced a new art and aesthetic programme which aimed at eliminating the aesthetics of the Allende era.25

Finally, the television images and photographs of the presidential palace in flames took the place of images that the military did not show. Photographs of the first victims of the dictatorship were withheld from the Chilean public, and neither were there any images of the deceased President Allende or of the Chileans who had been murdered by the new regime in the “Caravan of Death” only a few weeks after the putsch.26 The dictatorship already controlled and censored the media immediately after the seizure of power and thus also the production of images,27 which led to an imposing number of “forbidden pictures” and films, which have been rediscovered only recently.28

Not least, however, can the significance of visual and sound recordings from 11 September 1973, which are also used in feature films, be seen in the fact that they were quickly taken up by foreign media and reproduced again and again. Photos went around the world showing the first public appearance of the Junta in the Cathedral of Santiago, where the generals presented themselves in uniform and Augusto Pinochet hid behind sunglasses, in the style of the Greek putschists of 1967.29

In terms of media, the clouds of smoke above La Moneda and the sounds of detonations and street fights in the Chilean capital, which in turn became part of the auditory memory of the putsch, also marked the beginning of the Chilean military dictatorship for other countries. In this regard, as Bredekamp has commented, these images “stood in both reactive and creative relationships to the world of events”.30 For in fact the images from the capital city of Santiago reflected a battle whose outcome had already long been decided on a national level: when the aircrafts of the Chilean air force fired at the presidential palace the seizure of power had already taken place; later, the military authorities were to praise their own efficiency.31 And yet the Chileans who followed the reports on their television screens were led to believe that they were seeing the decisive confrontation between the putschists and the elected government.

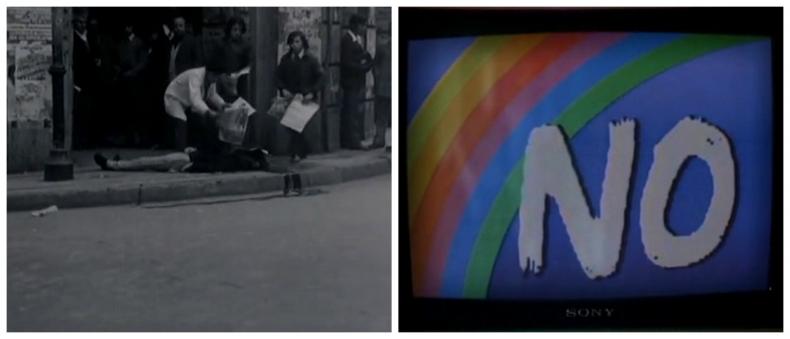

This is quite different from both the pictures of 5 October 1988, the day of the referendum, which introduced the end of the dictatorship, and those of the campaigns that were conducted in preparation of the plebiscite by the opposition and the military regime. They have been received much less and until now have had no iconic status.32 This is all the more surprising considering that these pictures and films also stood at the beginning of a lengthy and difficult process: the Chilean transition or return to democracy, which was started by the referendum. This fact also explains how it was possible in NO! to use these images not only to illustrate the campaign of that name but also as a basis for the criticism of its results. Before the television spots were taken up in NO! they apparently had no additional semantic accretions; they said 'prima facie' only something about the campaign strategy launched by the opposition in the difficult underlying conditions of the national referendum.

Historically, it is significant that the political framework of the plebiscite was set by the constitution newly decreed by the Junta in 1980. It provided for a referendum to be conducted after eight years among Chilean voters as to whether the dictatorship would be continued for another eight years or not. This provision was introduced because the military regime assumed that it would be measured against an opposition at war with itself and little more than an “alphabet soup” of different party abbreviations and ideologies.33 Contrary to this assumption, however, there were surprisingly little subdivisions in the political landscape of Chile in 1988 because in March 1988 the party of “Concertación por el No” had been founded. It united all the dissident groups under their smallest common denominator – the return to democracy through elections – and pursued the aim of rejecting an extension of the dictatorship and of the military’s 'democracia protegida y autoritaria', and of promoting a transition to democracy via elections.34 For this purpose important steps had been taken even before 1988. For example, the opposition had previously succeeded in reaching agreement on forms of resistance to the dictatorship which were legally possible within the authoritarian political framework; for example the initiative of persuading the Chileans to have their names entered in the register of voters, which had been destroyed in the putsch of 1973 and reopened in 1987. The campaign that is at the centre of the feature film was therefore of the utmost significance for the opposition but in turn was built on other measures and developments that are not mentioned here.

The low reception level, to date, of the campaign pictures of 1988 must also be surprising because they mainly came from the same source as those of 1973: the moving images of the seizure of power by the military as well as those of the referendum of 1988 were carried into the households of Chilean citizens especially by Chilean state television. However, the importance of television as a medium grew significantly in the years after the beginning of the dictatorship: the new policy aimed at consumerism had reached the masses, so that workers who had owned almost no domestic appliances before 1973 could afford at least a second-hand black-and-white television set already at the beginning of the 1980s and thus follow at home the television programming controlled by the military.35 Consequently, state television uniquely shaped the collective memory of events during the dictatorship as well as memories of its end.36

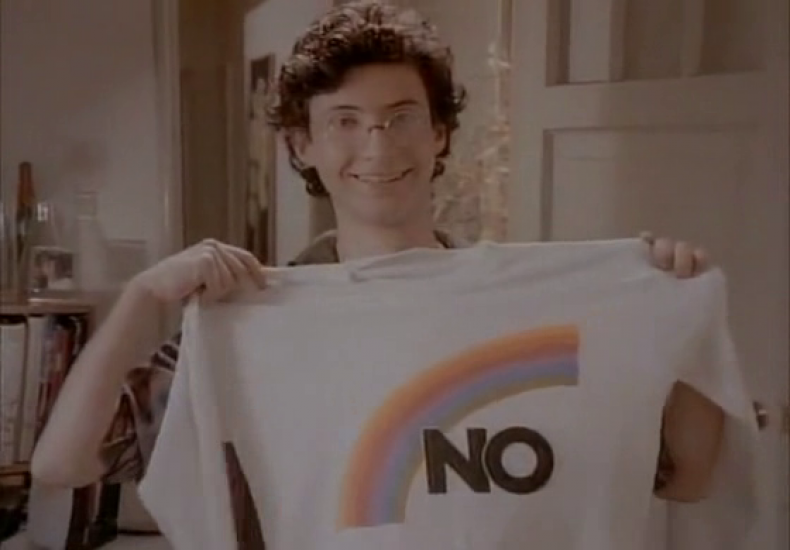

For this reason, it makes sense that in many of the recent feature films about the military dictatorship the characters can be watched following the television programming of the time. In such films as MACHUCA (CHL / ESP / UK / F 2004), in which the children of the middle-class family it centres on watch on television the images of the putsch that is taking place only a few kilometres from where they are, and in TONY MANERO (CHL / BRA 2008), in which the male protagonist at first watches television together with his later victim, the images and the underlying sounds of Chilean programmes migrate over the illusion of a technical device. The television set seems to be showing direct images of the past and makes it possible even for the viewers of the fictional film to watch them. Sometimes image migration is also achieved because the production of television images can be watched: the viewer of the film, both in NO! and in DAWSON. ISLA 10 (, 2009) watches the pretended shooting of television reports. In this regard, however, NO! even goes a step further in that image migration is prepared for from the beginning by the use of technology. The application of analogue U-Matic cameras, which were also used in the production of the real campaign spots, enables an image migration that no longer requires props and becomes the embracing aesthetic principle of the film. This principle can be assessed as an “aesthetic appropriate to the circumstances”:37 it deliberately blurs the boundaries between the migrated images and the fictional film of a later time.

Meanwhile, NO! also becomes a study of the power of television in Chile during the late 1980s, for in the case of the referendum television was the media location where the fight for votes was mostly carried out. It was there that the spots of the opposing campaigns were broadcast in rapid succession, and there that the advertising material of the opposition directly met that of the military regime and was later commented on in state television. Made for the television format, these spots were media creations, and they are also logically shown as such in Larraín’s feature film: the production of images by both campaigns, that of the regime opponents and its supporters – and their editing are staged just as the film characters are shown again and again following Chilean state television and watching the campaigns it broadcasts. The said migrated images of campaign spots are supplemented with product advertisements, excerpts from Chilean entertainment TV and footage of the demonstrations in the capital city, Santiago, in 1988; but television pictures of Pinochet’s journeys through Chile are also shown, journeys he took between 1986 and 1988 in preparation for the referendum.38 These journeys also brought him to Easter Island, whose picturesque landscape and people are correspondingly staged, being part of the mediatised self-advertising of the dictatorship, which presented itself as a one-man regime and began to promote itself long before the official campaign began.

Finally – and this is also important here – NO! represents an extreme case of image migration in the sense that it is difficult for the viewer of this film to decide which of the pictures are historical images from 1988 and which were made in 2012. This really perfect integration of documentary footage into the fictional film is, however, deliberately interrupted at a few points. When, for example, Patricio Aylwin, now marked by age, steps in to act as himself at the age of twenty-four, a young man appealing to the Chilean voters with a television speech, the director is drawing attention to the different time levels and pointing out that at this moment the Republic of Chile’s yesterday and its today are converged in the film. On the one hand this is an homage to the important historical actor Aylwin, on the other hand the process recalls the recipient to the present and breaks the illusion of the journey in time that the film is making in order to draw attention to the Chile in which the film was made.

Image migration in NO! and how it doubles to give a political report on the present

Larraín‘s feature film uses an advertising expert, and thus a representative of the neoliberal economic reform of Chile, as a main character who falls between two chairs: he is the archetype of the creative worker, called René Saavedra, and works in the advertising agency of the conservative Guzmán, who is one of those who have gained from the dictatorship and who actively assists the dictatorship’s campaign. In this way the positions of the regime supporters and the regime opponents meet each other in the advertising agency, for Saavedra has been commissioned to design the campaign for the opposition. Being the son of a known critic of the regime, he has a family background of dissidence as well as a militant wife who is working against the dictatorship, although he is now separated from her.39 Their joint son Simón is brought up by Saavedra alone, and he has sufficient income to afford a housekeeper who also looks after his child. His house in Santiago and its furnishings show him to be a well-situated Chilean who can purchase the consumer items of his time. For example, René Saavedra has a colour television set and is presented in the film also as the proud owner of a microwave oven, whose principle he doesn’t actually understand but which has recently arrived on the Chilean market brand-new from the USA and represents an icon of technical progress in a private household.

But Saavedra is also an outsider: due to his time of exile in the USA his biography puts him at a distance from various developments in Chile, he has an uncritical attitude to advertising and its means and takes an emphatically unpolitical stance. He is a character oriented economically to the upper middle class and sceptically keeps his distance from political events at first. Since various Chilean courses of life and the living conditions during the dictatorship are merged together in Saavedra, as a film figure he stands for something beyond just himself; he could be many.

Saavedra is of interest here not so much because he functions both as an antagonist to his conformist and opportunist boss and also as a contrasting figure to a politically deeply committed cameraman, but because beyond all that he has an important aesthetic function to perform: he enables a double image migration to occur. Saavedra has the task of developing the campaign for the party Concertación por el No, which Larraín integrates into the feature film by means of image migration. He also has the task of making the visual and sound language of commercial advertising, which he is familiar with and uses every day in the neoliberal Chile of the dictatorship, useful for the NO! campaign. In other words, the song of the campaign, Chile – la alegría ya viene,40 which is non-political at first sight, as well as the images for the campaign which Larraín purposely selects for migration into his feature film and thus recontextualises, had already migrated in Chile at the time of the referendum. They come from the advertising spots of the 1980s, which can be seen at the beginning of the film, as well as from the Hollywood feature film FAME (USA 1980), which was also very popular in Chile and whose dance scenes were taken up by the opposition campaign without acknowledgement. In this way Chile was evoked to be more at home in the reality of an American musical than characterised by the difficult reality of life under the dictatorship. Or, as the cameraman with whom Saavedra works under quasi-conspiratorial conditions expresses it: “My joy is different from yours”. The joy addressed in the title song of the campaign, which is said to be coming soon and which will be brought about by the absence of dictatorship, fear and compulsion, is, in the last analysis, a meaningless and unpolitical joy, which becomes manifest in the coloured and through-composed images of the advertising campaign. The joy of the cameraman, however, is of a kind that does not exclude sadness and loss – and stages lonely women in a no less lonely dance in another campaign spot for the No to an extension of the dictatorship under Pinochet. The contrast to the dance scenes in the advertising spot inspired by FAME could not be greater.

And so the advertising spots in the campaign for a No to the dictatorship invoke no political programme but divert attention to the world of consumerism which had started to waver due to the recession in Chile in the 1980s. Many Chileans feared the continuation of the dictatorship less than a return to the “chaos of Marxism” and the bogeyman of material deprivation that Augusto Pinochet spoke of repeatedly.41 In the campaigns they were not made familiar with contrasting political plans but rather with the promise of a continuation of the capitalist economic system and economic discourses in new conditions of political freedom. The visual language employed and even the song of the advertising musicians Sergio Bravo and Jaime de Aguirre use the messages of commercial advertising except that in this case the product is the No to authoritarianism. If this is to be seen as the start of a democratic Chile – and this seems to be evoked in NO! –, this transition could only be begun in continuation of the promise of consumer fulfilment offered by the dictatorship. In this way it became the basis of today’s Chile, whose understanding of democracy was in the public discussion not least at the time when NO! was produced.42

Conclusion

Film images can produce and alter memories. In the case of memories of the Chilean dictatorship this takes place in such feature films as NO! not by providing new images, however, but rather by combining historical images with new footage into a generic whole. The association with known images of recollection, which are an important motivating factor for image migration, defines the technical aspects of the production and also functions as the determining aesthetic principle of the film. Due to the use of U-Matic cameras even in the fictional parts of the film, the latter becomes a showpiece for the influential impact of television and consumerism. The role of consumerism is picked out as a central theme in today’s Chile as well by means of the out-of-focus imagery and imprecision of colours.

In addition, through the increased use of a few archival shots the film contributes to these continuing to be coded as “fixed historical images”. For all those who cannot claim to have witnessed the times, the images take the place of personal memories so that their value for the conveyance of memory in the media is established even further. In this process the role of a wide range of historical, collective actors is forgotten as well as the significance of various initiatives and measures that were taken long before the beginning of the advertising campaign that is at the centre of NO! in order to prepare for the referendum of October 1988. They were not shown in the archival footage selected. Larraín rather points out that through the merging of the opposition into an opportunistic alliance no genuine agreement about the character of the campaign’s contents nor about the political future of Chile after any possible end to the dictatorship was achieved. Rather, there were some tensions inside the Concertación, which also marked the transition to democracy and, according to Huneeus, point not least to the difficulties of historical recollection in Chile.43 This is also taken up by NO! and demonstrated with the use of the migrated images of the advertising campaign, which perceptively underline that image migration as a procedure in historical feature films points both to the past time being shown and also to the present time of the production. As such it deserves to be paid greater attention not only by specialists in film studies but also by historians in general.

- 1They were discussed already immediately after the transition to democracy and then again at the beginning of the new millennium, for example on the basis of the memories of the Junta general Matthei. See, for example, Isabel De la Maza and Patricia Arancibia Clavel, Matthei. Mi testimonio (Santiago de Chile 2003).

- 2See Dennis Vidal, “La migration des images. Historire de l’art et cinéma documentaire,” in L’Homme, 165 (2003): 249–266, esp.: 249ff.

- 3See Tobias Ebbrecht, “Sekundäre Erinnerungsbilder. Visuelle Stereotypen in Filmen über Holocaust und Nationalsozialismus seit den 1990er Jahren,” in Medien-Zeit-Zeichen. Beiträge des 19. Film- und Fernsehwissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums, ed. Christian Hissnauer and Andreas Jahn-Sudmann (Marburg 2007), 37–44, esp.: 40f.

- 4On this concept see: Ana Ros, The Post-Dictatorship-Generation in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay (New York 2012).

- 5Julian Paul Smith, “At the Edge of History,” in Film Quarterly 64:2 (2010): 12.

- 6Larraín’s tryptich of the military dictatorship includes the movies TONY MANERO (2008), POST MORTEM (2010), NO! (2012).

- 7Since 2000 about 17 films on this theme have been premiered, including those by Pablo Larraín already named and the following: MACHUCA (Andrés Wood, 2004); MI MEJOR ENEMIGO (Alex Bowen, 2005); DAWSON. ISLA10 (Miguel Littín, 2009); LA PASSION DE MICHELANGELO (Esteban Larraín, 2013).

- 8Alison Brysk, “Recovering from State Terror. The Morning After in Latin America,” in Latin American Research Review 38:1 (2003): 238–247, here: 239.

- 9See for example Burton’s statement in: Julianne Burton, Cinema and Social Change in Latin America: Conversations with Filmmakers (Austin 1986): ix.

- 10One spoke of “historical half-truths in the movie”, for example: Olga Khazan, “Four Things the Movie NO left our about Real-Life Chile,” in The Atlantic, March 4, 2013, accessed March 4, 2015, http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/03/4-things-the-m….

- 11Cf., for example: Marc Ferro, “Gibt es eine filmische Sicht der Geschichte?,” in Bilder schreiben Geschichte: der Historiker im Kino, ed. Rainer Rother (Berlin 1991), 17–36; Günter Riederer, “Film und Geschichtswissenschaft. Zum aktuellen Verhältnis einer schwierigen Beziehung,” in Visual History. Ein Studienbuch, ed. Gerhard Paul (Göttingen 2006), 96–113.

- 12Gertrud Koch, “Nachstellungen- Film und historischer Moment,” in Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit. Dokumentarfilm, Fernsehen und Geschichte, ed. Eva Hohenberger and Judith Keilbach (Berlin 2003), 216–229, here: 216, 223.

- 13The tensions in the relationship between film and history in Germany have been pointed out, for example, by: Riederer, “Film und Geschichtswissenschaft,” 96–113, here: 98f.; Peter Meyers, “Film im Geschichtsunterricht,” in Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 52 (2001): 246.

- 14On this aspect, see esp. the works of Gerhard Paul and, amongst others: Gerhard Paul, BilderMACHT. Studien zur Visual History des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts (Göttingen 2013).

- 15Gerhard Paul, “TV-Holocaust. Ein fiktionaler US-Mehrteiler als Bildakt der Erinnerung,” in Paul, BilderMACHT, 479–505, here: 484.

- 16The four-part series was broadcast in January 2014 on Tuesdays in the evening programme of the state television broadcaster TVN (Televisión Nacional).

- 17On the period of the Pinochet regime, its ideological features and political processes see, for example: Carlos Huneeus, El régimen de Pinochet (Santiago de Chile 2005); Genaro Arriagada, Por la razón o la fuerza: Chile bajo Pinochet (Santiago de Chile 1998); Pamela Constable and Arturo Valenzuela, A Nation of Enemies: Chile under Pinochet (New York 1991).

- 18Stefan Rinke sees in this a significant distinction between the civil war of 1891 and the putsch of 1973: in the late 19th century it was still the publicly exhibited body of the deceased President Balmaceda that formed the collective memory; in the putsch it was the image of the burning palace. Cf. Stefan Rinke, Kleine Geschichte Chiles (München 2007), 158.

- 19For the term postmemory, which was invented by Hirsch primarily in connection with the media representation of the holocaust see: Marianne Hirsch, “Surviving Images. Holocaust Photographs and the Work of Postmemory,” in Visual Culture and the Holocaust, ed. Barbie Zelizer (New Jersey 2001), 215–246, here: 218.

- 20Umberto Eco, Im Labyrinth der Vernunft. Texte über Kunst und Zeichen (Leipzig 1989), 302.

- 21Marcos Roitman Rosenmann, Tiempos de oscuridad. Historia de los golpes de estado en América Latina. Prólogo de Atilio Borón (Madrid 2013).

- 22On the history of the military dictatorship see, for example: Arriagada, Por la razón; Constable and Valenzuela, A Nation of Enemies.

- 23On the human rights violations see, for example Peter Kornbluh, The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountabilty (New York 2003). On cross-border state terrorism see, for example: John Dinges, The Condor Years: How Pinochet and his Allies brought Terrorism to Three Continents (New York 2005).

- 24On Chile’s economic reorientation and the importance of the Chicago School see: Juan Gabriel Valdés, La escuela de Chicago. Operación Chile (Buenos Aires 1989).

- 25Cf. in particular: Luis Hernán Errázuriz, “Dictadura militar en Chile. Antecedentes del golpe estético-cultural,” in Latin American Research Review, 44:2 (2009): 136–157.

- 26On the Caravan of Death see: Patricia Verdugo, La carava de la muerte. Los zarpazos del Puma (Santiago de Chile 2001).

- 27On the “voluntary synchronisation of the media” in Chile after the putsch see: Huneeus, El régimen, 114–116.

- 28With great attendance of a large audience the series “Chile – las imágenes prohibidas” ran on the private programme Chilevisión from August 2013 with, until now, four parts. A DVD collection with the same title is still selling very well.

- 29The fact that the Junta was presenting itself to the public copying the appearance of a different one is probably not a coincidence; this further underlines the importance of images for the symbolic communications of the military.

- 30Horst Bredekamp, “Bildakte als Zeugnis und Urteil,” in Mythen der Nationen. 1945 – Arena der Erinnerungen, Vol. 1, ed. Monika Flacke (Mainz 2004), 29–66.

- 31Huneeus, El régimen, 94–96.

- 32At least one work even in the year of the referendum showed the history of the No campaign on the basis of its graphic representations, flyers and posters: Cristián Cottet Villalobos, El panfleto. El plebiscito de 1988 a través de suspnafletos y volantes (Santiago de Chile 1988).

- 33Huneeus, El régimen, 572.

- 34On the concept of “protected and authoritarian democracy” and its rejection see: Huneeus, El régimen, 604f. On the preparation of the plebiscite see, for example, the following essay: Manuel Antonio Garretón M., El plebiscito de 1988 y la transición a la democracia (Santiago de Chile 1988).

- 35On consumerism and the significance of television sets in Chile at the time of the dictatorship see: Heidi Tinsman, Buying into the Regime. Grapes and Consumption in Cold War Chile and the United States (Durham and London 2014), here: 78–83. On the basis of contemporary Chilean censorship statistics the historian determined that, for example, three quarters of the workers in the Aconcagua Valley and greater Santiago owned a television set in 1982; this proportion continued to grow.

- 36Surprisingly, that has not yet been researched from a historical point of view.

- 37Cf. Caetlin Benson-Allott, “An Illusion Appropiate to the Conditions NO (Pablo Larraín 2012),” in Film Quarterly 66:3 (2013): 61–63, here: 61, where in particular the coarse grained images and lack of focus in the video technology of the 1980s is emphasised. The author refers to Massood, who demonstrates that a unique cinematographic reality can be produced by combining various techniques. See Paula Massood, “An Aesthetic Appropiate to Conditions: Killer of Sheep, (Neo-) Realism and the Documentary Impulse,” in Wide Angle, 21:4 (1999): 20–41.

- 38A record of these journeys can be found in: Huneeus, El régimen, 571.

- 39The character of José Tomás Urrutia, who appears as representative of the Concertación, introduces Saavedra as the son of Manuel Saavedra and asks those present: “I think you all know him, don’t you?” DVD 00.35:30.

- 40The campaign song can be translated as “Chile, Joy is Coming”.

- 41See Tinsman, Buying into the Regime, 210.

- 42In 2011 and 2012 there were big protests from pupils and students in which at times the Chilean unions also took part. Wide-ranging reforms were demanded in the education sector. At the same time it again became clear that Chilean democracy, which leaves little room for participatory political processes, was seen by young people, indigenous minorities and workers as a democracy which leaves them on the outside. See: Maxwell A. Cameron, “New Mechanisms of Democratic Participation in Latin America,” in LASA Forum, XLV:1 (2014): 4–6, here: 4.

- 43On the tensions in the Concertación and the “memoria histórica” see, for example: Huneeus, El régimen, 623–639, esp. 638f.

Arriagada, Genaro. Por la razón o la fuerza: Chile bajo Pinochet. Santiago de Chile 1998.

Benson-Allott, Caetlin. “An Illusion Appropiate to the Conditions NO (Pablo Larraín 2012).” Film Quarterly 66:3 (2013).

Bredekamp, Horst. “Bildakte als Zeugnis und Urteil.” In Mythen der Nationen. 1945 – Arena der Erinnerungen, Vol. 1, edited by Monika Flacke. Mainz 2004.

Brysk, lison. “Recovering from State Terror. The Morning After in Latin America.” Latin American Research Review 38:1 (2003).

Burton, Julianne. Cinema and Social Change in Latin America: Conversations with Filmmakers. Austin 1986.

Cameron, Maxwell A. “New Mechanisms of Democratic Participation in Latin America” LASA Forum, XLV:1 (2014).

Constable, Pamela and Arturo Valenzuela. A Nation of Enemies: Chile under Pinochet. New York 1991.

Cottet Villalobos, Cristián. El panfleto. El plebiscito de 1988 a través de suspnafletos y volantes. Santiago de Chile 1988.

De la Maza, Isabel and Patricia Arancibia Clavel. Matthei. Mi testimonio. Santiago de Chile 2003.

Dinges, John. The Condor Years: How Pinochet and his Allies brought Terrorism to Three Continents. New York 2005.

Ebbrecht, Tobias. “Sekundäre Erinnerungsbilder. Visuelle Stereotypen in Filmen über Holocust und Nationalsozialismus seit den 1990er Jahren.” In Medien-Zeit-Zeichen. Beiträge des 19. Film- und Fernsehwissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums, edited by Christian Hissnauer and Andreas Jahn-Sudmann. Marburg 2007.

Eco, Umberto. Im Labyrinth der Vernunft. Texte über Kunst und Zeichen. Leipzig 1989.

Errázuriz, Luis Hernán. “Dictadura militar en Chile. Antecedentes del golpe estético-cultural.” Latin American Research Review, 44:2 (2009).

Ferro, Marc. “Gibt es eine filmische Sicht der Geschichte?.” In Bilder schreiben Geschichte: der Historiker im Kino, edited by Rainer Rother. Berlin 1991.

Garretón M., Manuel Antonio. El plebiscito de 1988 y la transición a la democracia. Santiago de Chile 1988.

Hirsch, Marianne. “Surviving Images. Holocaust Photographs and the Work of Postmemory.” In Visual Culture and the Holocaust, edited by Barbie Zelizer. New Jersey 2001.

Huneeus, Carlos. El régimen de Pinochet. Santiago de Chile 2005.

Khazan, Olga. “Four Things the Movie NO left our about Real-Life Chile.” The Atlantic, March 4, 2013, accessed March 4, 2015, http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/03/4-things-the-m….

Koch, Gertrud. “Nachstellungen- Film und historischer Moment.” In Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit. Dokumentarfilm, Fernsehen und Geschichte, edited by Eva Hohenberger and Judith Keilbach. Berlin 2003.

Kornbluh, Peter. The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountabilty. New York 2003.

Massood, Paula. “An Aesthetic Appropiate to Conditions: Killer of Sheep, (Neo-) Realism and the Documentary Impulse.” Wide Angle, 21:4 (1999).

Meyers, Peter. “Film im Geschichtsunterricht.” Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 52 (2001).

Paul, Gerhard. BilderMACHT. Studien zur Visual History des 20. und 21. Jahrhunderts. Göttingen 2013.

Ros, Ana. The Post-Dictatorship-Generation in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay. New York 2012.

Riederer, Günter. “Film und Geschichtswissenschaft. Zum aktuellen Verhältnis einer schwierigen Beziehung.” In Visual History. Ein Studienbuch, edited by Gerhard Paul. Göttingen 2006.

Rinke, Stefan. Kleine Geschichte Chiles. München 2007.

Roitman Rosenmann, Marcos. Tiempos de oscuridad. Historia de los golpes de estado en América Latina. Prólogo de Atilio Borón. Madrid 2013.

Smith, Julian Paul. “At the Edge of History.” Film Quarterly 64:2 (2010).

Tinsman, Heidu. Buying into the Regime. Grapes and Consumption in Cold War Chile and the United States. Durham and London 2014.

Valdés, Juan Gabriel. La escuela de Chicago. Operación Chile. Buenos Aires 1989.

Verdugo, Patricia. La carava de la muerte. Los zarpazos del Puma. Santiago de Chile 2001.

Vidal, Dennis. “La migration des images. Historire de l’art et cinéma documentaire.” L’Homme, 165 (2003).