Sound Space as a Space of Community

On the Playful Construction of History in THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Pauleit, Winfried: Sound Space as a Space of Community: On the Playful Construction of History in THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–18. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14792.

Like narrative storytelling, historiography requires a medium. With this in mind, Hayden White described the process of writing a history of the nineteenth century as a poetological technique, a process that could equally be conducted via the medium of film.2 If we follow this assumption, White’s critique of the narrative nature of historiography can also be applied to the twentieth century and to film. This brings about a shift in focus away from grasping historiography in terms of literary theory (as in White) and towards a mediatization of this technique, which involves linking together different perspectives from literary, visual, and sound theory into a complex film studies approach. This entails bringing history into connection with the respective apparatuses of narration and literary history as well as those of photography and the media that have followed it, that is, the history of images and moving images, before also connecting it to the apparatus of recording sounds, voices, noises, and music: in other words, a history of sound objects.

If White’s critique is expanded to encompass cinematic techniques, this does not just affect the link between fact and fiction in the realm of language (or that of text and discourse) that is applied to the audiovisual narratives of film. The link between the documentary and the staged is of equal relevance here, taking the form of a conception of visual history that emerges before the backdrop of a general iconology that includes the moving image. The focus here is thus not only on what has been photographed and filmed and is thus historically authenticated, but also on how the recording and processing of any such things behaves in relation to the manifold arsenal of pre-existing and conceivable images. And finally, the connection between original historical sounds, how they were recorded and processed, and other sound objects must also be considered in this context, a connection which is revealed before the backdrop of all the many possibilities and conceivable sounds. This is the complex field within which the relationship between film aesthetics and history is situated.

In the following I would like to explore the complex relationship between film aesthetics and history by taking THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA (F / USA 2005) as an example. The main focus here is on how different constructions of history are played with, which I will try to sketch out in seven steps. Aside from the plot (1), I begin by describing a regime of visual control and the conditions needed to generate the possible visual history which the film establishes alongside its plot and is tied to media objects and the cultural practices linked to them (2). Another focus is on the film’s playful, strategic use of images and sound interventions (3), which develops into a political aesthetic of the sound space as the film progresses (4). This leads to a cumulative deconstruction of narrative space that moves increasingly towards the realm of time travel (5). This shift is in turn linked to intertextual discourses that serve to underpin and secure the film’s political aesthetic (6). I conclude by exploring how the film’s move towards the sound space establishes a space of political community (that forms a stark contrast to the actual political-geographical border region between Texas and Mexico) and how the film draws on this political aesthetic to lay out the foundations of an audiovisual historical practice (7).

1. Film Plot

THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA tells the story of the death of a migrant worker in Texas and how his body is returned to Mexico. This repatriation is based on a promise that Melquiades Estrada (Julio Cedillo) once asked his friend and employer Pete Perkins (Tommy Lee Jones) to make: he always wanted to be buried in his hometown of Jiménez, Coahuila, Mexico. When Melquiades is shot by a border patrol, and the sheriff wants to cover up the case, Pete decides on his own to exhume his friend’s already buried body and to take it to Mexico on horseback. To this end, he also kidnaps the border patrol officer Mike Norton (Barry Pepper) who shot his friend and forces him to help out on the journey.

The first part of the film (circa 50 minutes long) consists of highly fragmentary sequences that sketch out Melquiades’s backstory and how he died. The story is told from various different perspectives and makes use of an intricate temporal structure whose leaps back and forth through time and space are often confusing for the viewer. The second part of the film lasts another 50 minutes and comprises the trip itself. The return of the dead body is connected with a series of encounters and obstacles of a surreal nature that repeatedly lead the film’s narrative threads into impassable terrain in metaphorical terms. The journey finally ends in an abandoned ruin that Pete declares to be the village of Jiménez. Melquiades is buried one final time, and under Pete’s instructions, the border patrol officer is subjected to a ritual of atonement that draws its effectiveness from the revolver shots fired in immediate proximity. The kidnapped border patrol officer is then released, marking the end of the almost two-hour film.

2. Visual Control versus Visual History

The film constructs a regime of visual control from the start, which is marked by the use of telescopes, gun sights, maps, all-terrain vehicles, and the helicopters of the U.S. Border Patrol that control the geographic border region between Mexico and Texas. The visual depiction of this regime begins with the very first shot of the film, in which the classical establishing shot of the Western—a broad natural landscape—is challenged by the gaze of surveillance, as two border patrol officials drive their jeep through this landscape. The camera observes the car and follows its movements by means of a pan from a raised position. The jeep gets closer and closer to the camera but stops just before reaching it. Having arrived at this vantage point, the border patrol officers now monitor the landscape with their binoculars. They discover a coyote whilst doing so and take pleasure in using the riflescope fitted to their guns to kill it from their car.3 The dead coyote then leads the border patrol officers to the corpse of Melquiades Estrada. The story of the dead man is told in flashbacks and determines the rest of the film’s plot.

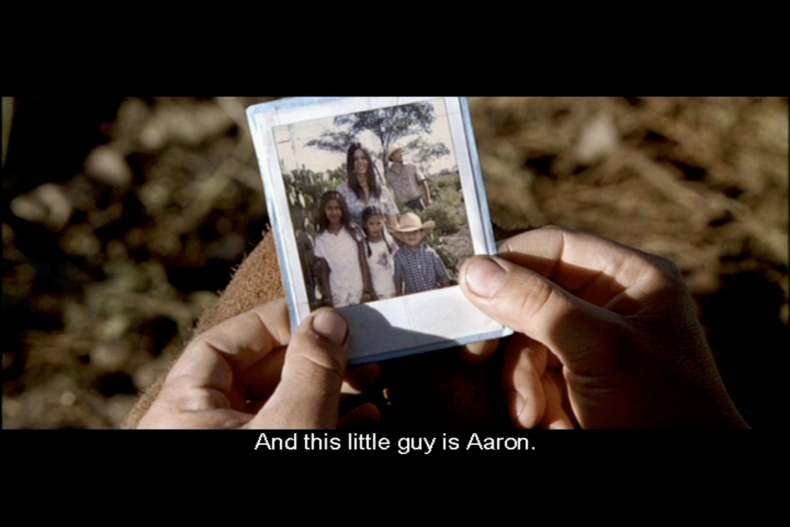

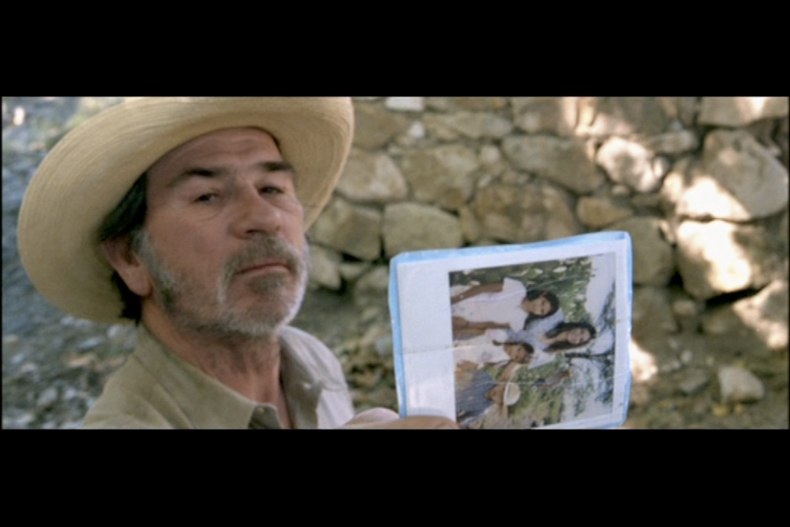

The second part of the film is staged as a movement through different landscapes (Pete, Mike and the dead Melquiades on horseback), whereby the travelers themselves also make use of visual media. Pete uses a map drawn by Melquiades for directions and carried a Polaroid photograph with him supposedly showing his dead friend’s family. These media are not just used for orientation purposes or identifying family members. They also represent media objects that form the narrative underpinnings for the entire undertaking: the return of a dead man to his homeland and the film’s status as a complex mixture of genres that also straddles theory and discourse.

Furthermore, the film also creates a secondary logic from these media objects, a logic of remembrance shaped by Pete’s relationship to the dead man. The photograph and map are media objects in a dual sense. They purport on the one hand to be universally valid, objectively verifiable records (a cartography of Melqiuades’ home village, a photograph of his family), while at the same time functioning as material traces of his story, given that they come from his very hand. For Pete, they are thus magical objects he can use to summon up the memory of the living Melquiades, a process the viewer can also participate in via flashbacks. The film contrasts these flashbacks with his friend’s dead body, which is an increasing state of decay. The objects characterize the repatriation as a final journey that brings the dead man to the place he is destined for (his home village/the cemetery) while also attesting to the time they spent together as a joint 'history'.

The use of a Polaroid photograph emphasizes and gives an aura to the past and the (alleged) moment of happiness, the point in time when Melquiades was still alive and close to his family, particularly because its status as a unique photographic object attests to this one moment in space and time.4 The same is true of the map Melquiades drew by hand in Pete’s presence. The map is a handwritten record by the dead man, which also certifies it as genuine but more in the sense of a last will and testament than as a reliable means of orientation. These objects are diametrically opposed to the various elements of visual control, belonging as they do to the tradition of personal records and sketching the conditions for a possible visual history that accompanies and authenticates the oral narratives.

3. Visual Politics and Sound Interventions

In one of the numerous flashbacks, Pete and Melquiades are sitting in the midst of the landscape taking a break. It is in this scene that Melquiades expresses his desire to be buried in Mexico. Here too, he uses the Polaroid to introduce Pete to his wife and his children and also finishes the map that he then hands over to his friend, making Pete promise to actually take him back to his home village in case of his death.

This is a key scene in many ways. First of all, it provides the justification for the entire plot and explains why someone already buried might be illegally returned to the place of his birth. Second, the way, in which image and sound diverge from one another, reveals the scene to be typical of modern cinema. The dialogue has Melquiades talking about the many billboards in the United States and emphasizes his desire to be buried in the beautiful landscape of his homeland. Visually however, the scene of the two of them taking a break shows them sitting within a romantic natural landscape on the edge of a lake with birds, horses, and flora, scarcely touched by civilization with a musical score of accordion music and no billboards to be seen whatsoever. The dialogue and the audiovisual image depart entirely from one another in this scene and form a paradox, which is accepted on the one hand as the narrative justification behind the subsequent return of the corpse to Mexico whilst also triggering a sudden flash of confusion at this juncture. This same sense of confusion is reestablished again and again over the course of the film, which has the effect of making the relationship between narrative dialogue, visual space, and sound space drift further and further apart. Third, an aesthetic game that plays with various discourses is also conducted, with this scene forming a starting point: the invisible billboards serve as an image of an alienated way of life, an image defied by both the disposition of the two cowboys and how the natural landscape is depicted. They embody the cliché of an authentic lifestyle that draws on the figure of the archetypal Western hero, who, according to American mythology, pushed forward the civilization process of the country from East to West. The trick here is that precisely the same clichés of an authentic way of life are often re-depicted on billboards, and yet are only actually to be found in dialogue here, never shown. Or, in other words: Pete and Melquiades act out a billboard in this scene. Pete and Melquiades’s first encounter already reveals striking similarities to the iconographic tradition of the Marlboro advertisement, with the technologically well-equipped border patrol offering the actual contrast here. The cowboys seem to have come from another era, or appear like characters who straddle various different time periods—complex temporal images that also seem to unite all the clichés of advertising.

But this does not entirely explain the key role played by this scene. In light of this billboard discourse, Melquiades pulls out the Polaroid of his alleged family and describes it to his friend, singling out the name of his wife, Evelia Camargo, and the ages of his children Elisabeth, Yesenia und Aaron in the process, a piece of dialogue that comes across like one more cliché relating to the authenticity and individuality of a family photo. The sleight of hand shown by the film with regard to the formation of this discourse emerges from the fact that the narrative of family identity is ultimately proven to be false and thus discredits not just the hierarchy of knowledge within the narrative but also the very authenticity of photography.

The background to these narrative dead ends and lack of visual reliability is formed by the film’s sound, which is afforded a special role with regard to how the film plays around with various knowledge hierarchies. The sound initially complements the visual beauty of the landscape and emphasizes its vitality by means of a combination of composed film music (Marco Beltrami), local musical styles (country, norteño, Tex-Mex), and striking sound design that takes in animal sounds, bird calls, and other noises. To begin with, all these elements in the film perform an accompanying function, much like that of a musical score. Over the course of the film, the sound develops into far more than just an aesthetic quality and an emotionalizing effect. It is actually expanded to form a sound space that constitutes a distinct order of its own, separate from that of the visual regime of controlled space (but also that of the visual clichés) and from parts of the narrative order. An aesthetic game emerges that plays around with the different orders of narrative space,5 visual space,6 and sound space7 that gradually reveal THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA to be a work of modern cinema and ultimately a film that explores the theory-discourse divide. For the sound level is structured around a series of dialogues that perform a deictic function and position themselves in opposition to what is seen and heard, such as when the numerous billboards are mentioned despite their being nothing to be seen far and wide, or in dialogues that take the form of gags that explicitly refer to the sound track and yet seem to have no greater significance than that.

The first instance of this is when the blind man on the radio explains, “I can’t understand anything, but I like the way Spanish sounds, don’t you?” The second is when a border patrol officer asks the blind man whether he’s seen anyone passing through on horseback lately, to which the blind man answers, “I ain’t seen anybody in 30 years!” This answer leads the officer to then rephrase the original question: “Have you 'heard' anyone come this way in the past few days or hours?” This repeated question directed to the blind man within the diegesis creates a self-reflexive moment in that it emphasizes the border patrol’s regime of visual control and asks the blind man for help in establishing this regime. Yet the character of the blind man makes both the individual question and the entire undertaking of visual control seem absurd, and also emphasizes how fixated it is on present-day space. His comment that he hasn’t seen anybody for thirty years evokes a dimension of historicity which the border patrol has no interest in.8 The rephrasing directs the spectator’s attention once again to the different levels of perception represented by image and sound and the obvious differences between these levels revealed by the film.

The scene opens with a sound montage in which we first hear kidnapped border patrol officer Mike Norton’s cry for help following a snakebite, which is, however, largely muffled by a norteño song by Cornelio Reyna playing on the blind farmer’s radio entitled “Me caí de la nube.”9 There is also an additional underlying layer of sound formed by the noises made by the helicopter and the border patrol’s convoy of vehicles. All these distinct elements generate a polyphonic sound tapestry more than capable of integrating the level of the helicopter and car sounds into the music. So while the visual focus is firmly on the border patrol operations taking place within a rural space, which is also intended to establish the visual regime of police control, the sound track creates a genuinely cinematic sound space that takes the norteño as its starting point, picking up on the rhythm of the accordion and the martial fighting troops of the border patrol in particular and incorporating them into this comprehensive cinematic sound space which, for one utopian moment, re-appropriates the helicopter and convoy vehicles’ movements to form a dance number.10

4. The Political Aesthetic of the Sound Space

The aesthetic confrontation between narrative space, visual space,and sound space firmly belongs to the tradition of modern cinema. Yet in THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA, this confrontation is also revealed to be a political aesthetic. This is not just due to the way in which the film explains how a visual regime of control is implemented on the Texas-Mexican border, which shows how this border is effectively sealed off to prevent migrants from crossing it (this happens more or less incidentally), but rather because the film operates by taking the sound space as its point of departure, positing it as a space of popular community, and from then on in allowing it to intervene again and again in the visual and narrative order in playful, yet also goal-oriented fashion. After about the first hour and a half, the travelers (and with them the film as a whole) arrive at a point where the epistemological signposts (map and photograph) are proven to be false. The protagonists’ (Pete, Mike, and the dead Melquiades) journey loses any sort of meaning within the film’s narrative structure because there exists neither a family that remembers the deceased, nor a hometown to which the body could be returned. This realization comes about based on a conversation with Melquiades’s supposed wife, who is identified by the residents of a Mexican village on the basis of the photograph, but actually has a different name and is married to a different man. Another of the village inhabitants then confirms that the village of Jiménez drawn by Melquiades on the map also does not exist in the cartographic space sketched out. Both the protagonists and the spectator thus realize that they have been on the wrong track. This has the effect of pulling the carpet out from under the goal-oriented undertaking (returning the dead body) that has thus far comprised the plot. This realization not only alters the film’s narrative structure, but also enacts a change in its visual space, which, despite all the extravagant landscape shots, has until now been seen as a consistent, controllable geographical space that can be crossed in targeted fashion with the help of optical devices and maps. The protagonists now find themselves within a visual space no longer in harmony with the assumptions that arise from the map and Melquiades’s oral testimony shown in flashback.

This forms a dramatic turning point in how the film is to be understood, as, in the first part of the film in particular, the plot hinges on the fundamental elements of the map and the photograph. These objects also hold great significance when it comes to how the viewer perceives the film, given that they offer a sense of semantic and orientational security amongst all the deliberately confusing editing techniques and jumps back and forth in time. Up to this point, the hand drawn map and the Polaroid photograph have served as reliable anchors of a visual history and have also forged a connection to the reality effect of the film watching experience. Both are now revealed as being imaginary: a distancing effect that brings not just the constructed nature of the photograph and the map to the fore but also that of the film itself. This reassessment of the map and the photograph makes the film’s previous sense of order collapse entirely. All that now remains is the beauty of the natural landscape that envelops the travelers, while the viewer must now search for a new interpretational model. It is only the sound track, with its musical score and animal sounds, and the sound space it constructs which is still tenable here, unlike the visual and narrative “story” which can no longer be relied on.

The first indication that the map and the photograph’s reliability has become devalued can been seen in the facial expressions of the Mexicans from whom Pete asks for help, who are clearly baffled by Pete’s story, which makes references to both the map and the Polaroid. Three conversations take place to this end that move back and forth between English and Spanish. The puzzling nature of his account also becomes palpable in how the village name Jiménez is repeated again and again in the first conversation in questioning fashion, with the third conversation finally ending in “It does not exist around here?” (spoken in a strong Mexican accent), before being dismissed entirely in the shift back to Spanish: “no existe, porque?” The constant movement back and forth between the two languages at the level of the dialogue serves to make the narration even more precarious and fragile. For to begin with, it is not clear whether the problem here is merely one linked to understanding the respective other language and culture, a translation problem that might be attributed to the differences between the languages, or whether the village and the family in the photograph actually do not exist—at the very least not as Melquiades described (in Spanish). It is when this semantic vacuum at the level of the narrative has brought the conversation to a standstill and elicited disturbed or questioning facial expressions that the soundtrack draws attention to itself once again. At first, the only “response” to the Mexican’s various negations (“It does not exist around here,” “No existe”) is the unmistakable cry of a bird, which gives additional emphasis to the sentences spoken until the musical score takes over, whereupon a cut shows that the travelers are suddenly once again alone in the landscape on horseback. The placement of the bird call is significant in that it appears at precisely the moment at which an omniscient narrator or an off-screen acousmatic voice might otherwise turn up in order to suture the break in the narrative.11 The bird call is edited into the sound design like a voice (rather than a coincidental natural sound aimed at generating atmosphere). It is perceived as a voice would be, accentuates the Mexican’s statements, and stresses the break at both a visual and narrative level by way of its vocal presence. This piece of sound editing also forms another intervention on the part of the sound space into the visual and narrative order by its deliberate elision of any specific action, with its acoustic presence thus actually heightening the semantic vacuum generated.

This trick goes to the very heart of the political aesthetic of THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA. The bird call actualizes and attests to the sound space as a space of community (in direct opposition to the geographic-political border area) in much the same way as the previous example with the sound of the accordion and the appearance of the border patrol. This strategy is particularly effective here because there is no omniscient narrator or any other kind of authority capable of imparting narrative meaning to the film. As a vocal phenomenon, the bird call accentuates the sound space and places it in clear relation both to a fragmentary narration that has been taken to absurd limits and whose meaning has fallen apart and to a space of visual history (which does not just contain phony family photographs, but also border patrol officers kitted out with binoculars and long-range gun sights). The film’s political aesthetic appropriates the unique characteristics of the acoustic, which (unlike the gaze) forms an all-encompassing space, and draws on specific sound montages in order to give it the function of a non-hierarchical and communal space that intervenes in the narrative and the visual realm. The political aesthetic thus makes indirect reference to the period before the Mexican-American War (1846–48), when this space was not yet a border region. The construction of the sound space as a communal space is thus flaunted and concealed in equal measure: on the one hand, we hear the bird call as a voice, for it is inserted at precisely the moment where dialogue would normally appear, while, on the other hand, the fact that it is a natural sound means it also embodies an external perspective (the voice of God, an omniscient narrator, a directorial authority) and thus guarantees that this position is not occupied by any other explaining authority.12 The sound space thus refers both to the buried history of a cultural space (without the voice necessary to articulate it) as well as to a utopian space of community that is depicted as both a musical space and an existential natural realm that envelops all people, animals, plants, and things.

5. Time Travel

The scene that follows this break shows Pete and Mike once again on horseback in a landscape. They are now arguing whether Melquiades might have been lying and whether there is actually a place called Jiménez or not. This discussion on the truth of the matter refers once more to the conditions according to which history is constructed in both narrative and visual terms. Their conversation also takes on a touch of the absurd, because the city of Jiménez in Coahuila, a border town near the Rio Bravo, does indeed exist outside this particular fiction. It was founded in 1858 as Villa La Resurreción and renamed Jiménez in 1875 in honor of Mariano Jiménez, a leader of the Mexican independence movement. Jiménez was also the place where the first revolts leading up to the Mexican Revolution took place.13

Pete now continues to try to get his bearings using the map. But the disorientation he feels now becomes increasingly palpable in the visual space: the movement of the riders is expressed in different visual terms than previously. From the very start of the film, their crossing of the landscape was depicted as a non-linear movement through space, a movement that proceeds in loops and interacts with everything to be found in the natural landscape. The camera generally followed the riders to this end, thus simultaneously creating the impression of an ongoing journey that progressively crosses the space. Once the meaning behind their journey has disappeared, the riders are now shown as being lost in the landscape, the movements they make on their travels accompanied by a slow, sideways tracking shot that pans gently backwards at the same time. This dual camera movement both distorts and gives a different dynamic to the visual space, creating the impression that they are standing still regardless of how much they move.

It is at this point that the riders’ journey becomes a form of time travel, a trip into the past which has been alluded to from the very beginning. For Pete does not return the dead body to Mexico using the pick-up truck he owns and is driving when he kidnaps the border patrol officer. This trip isn’t a road movie, but rather a journey into the past that shuns modern roads. This impression is equally reflected in the means of transportation used (a journey on horseback), which forges a link to the archetypal Western hero, who embodies the limits of civilization. At the same time, the journey reconstructs the time-image of Pete and Melquiades who sit within the natural landscape in the guise of two cowboys (the kidnapped border patrol officer is made to wear Melquiades’ clothing on the trip). Pete thus puts a modern spin on the myth of the archetypal Western hero at a point at which civil society is failing, given that the guilty border patrol officer is not brought to justice, and the Mexican does not receive a fitting burial. He grasped Melquiades’s final wish to be returned to the place of his birth both literally and discursively as the desire to be a cowboy and to be buried as such (on the frontiers of civilization).

For this reason too, pinpointing the location of Jiménez does not require a map that refers to contemporary geography, but rather one that functions as a time-image and that can thus only be reached by means of time travel. With this in mind, the map drawn by Melquiades takes on an additional meaning: Jiménez is shown here as being located between the cities of El Nacimiento (meaning birth) and El Tostón (the name of a 50 centavo coin). These city names point to a temporal cartography and the political-economic contexts that go hand in hand with it. The village could thus also be described as a place that lies between the existential entrance into the world denoted by birth and the economy of poverty denoted by 50 centavos.14

Melquiades’s map thus sketches out a whole lifespan within the context of a specific political economy whose imaginary asymptote or place of desire is Jiménez, a place which equally conceals the commemoration of someone who fought for Mexican independence, the old name of the city La Resurrección and the first conflicts in 1906 that led up to the Mexican Revolution. What emerges from this shift from a geographic map to a temporal one or that of an imaginary place of desire is that Melquiades Estrada ('estrada' is Portuguese for “street”) has no hometown to which he could be returned. Yet he still laid claim to such a place in a conversation with Pete, and included it in his map. The dead body thus continues to insist on being buried in the place it desires. Pete reacts to the situation as any archetypal Western hero would: he founds the village of Jiménez (which does not exist in the film) in the natural landscape merely as a place to bury his dead friend, building a house for him and adding a sign that reads “Jiménez, Coahuila.”

This act is staged in much the same way as the classical moment at which a heroic settler sets up his homestead, the only difference being here that no settlement or farm is being set up for the future, but rather a cemetery where a dead man may finally find the one true place of his own. The creation of the homestead can thus be seen as a retrospective action or a re-enactment. The viewer thus witnesses an act of deception at a narrative and visual level. The journey through time is disregarded by the mise-en-scène, with Pete pointing to the imaginary elements of the village and labeling them one by one (well, store, cemetery, garden), while holding the family photograph up to the camera once more as a piece of evidence before the lens, but this time at right angles to it. It is only the sound track that generates the by now familiar sound space, which, unlike the narrative and visual space, does not lose its meaning but is rather transformed into a historical, utopian space of community.

The basis for this dramatization of communal space can be found in the sound compositions used in the film that refer to the culture of the border region. These include an elaborate sound design with respect to the sounds included, a musical score that draws on traditional and even at times newly invented instruments made from cactus,15 and the use of regional music from Texas and Mexico (norteño, country, Tex-Mex, etc.). As far as sounds are concerned, bird calls in particular play an important role, appearing whenever the narration turns out to be leading the viewer astray. THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA uses bird calls from the border between the United States and Mexico taken from a scientific archive at Cornell University.16 The dramatization of the sound space also occurs indirectly, such as the decision to cast folk musician Levon Helm as the old man on the radio who had lost his singing voice to cancer by this point, but not his sight. The actor playing the sheriff, Dwight Yoakam, is also an American country singer whose music is heard in the film (“Fair to Midland”).

6. Intertextual Discourse

One intertextual film historical reference that depicts a cowboy’s attempts to give a “migrant” a proper burial and ends ups with a Mexican village being “saved” is John Sturge’s THE MAGNIFICENT SEVEN (USA 1960). This Western introduces its protagonist Chris (Yul Brynner) when he brings a dead “migrant” to the village cemetery in a small town in the southern United States and then wields his gun in order that the stranger may receive a suitable burial despite the resistance of the white residents. He is then hired by Mexican farmers to protect their village from bandits and brought to Mexico.

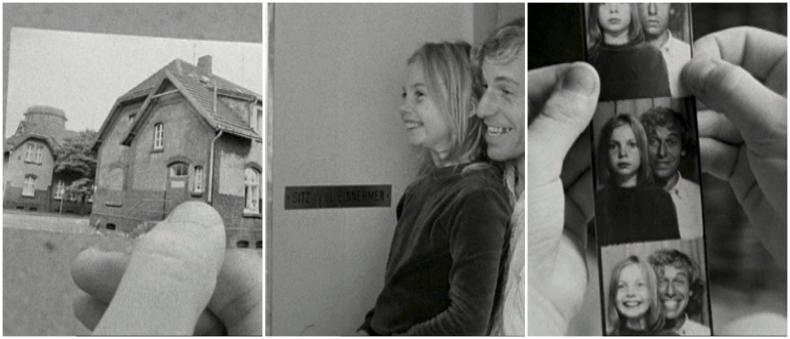

Another such reference is formed by Wim Wenders’ ALICE IN DEN STÄDTEN / ALICE IN THE CITIES (D 1973), in which a family is reunited by means of a photograph. Journalist Philip Winter (Rüdiger Vogler) is entrusted with a girl named Alice (Yella Rottländer) on his trip from New York back to Europe. At Amsterdam Airport, they lose contact with Alice’s family. Using a photograph of her grandmother’s house and a list of German city names, Alice and the journalist try to find her family and set out on a trip to Germany to this end. They ultimately succeed in finding the house in the photo in a city in the Ruhr region, although Alice’s grandmother already left the house several years previously. During their trip, various joint photographs are taken in a photo-booth that construct a fake image of a father and daughter, thus inscribing a theoretical discourse about photography and travelling into the film. THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA takes up both these discursive strands, that of a cowboy in Mexico and that of using a photograph to search for a family or construct a fake one, and reworks them.

THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA also draws on discourses from migration films, such as those shaped by EL NORTE / THE NORTH (UK / USA 1983) by Gregory Nava, with THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA further complicating the plot to this end. The focus here is on two interrelated journeys. The photograph and the maps attest to Melquiades Estrada’s previous migration to the United States to which many references are made in the film, such as his fear of the border police and getting deported or the scenes showing other migrants crossing the border. For their part, Pete and Mike move in the opposite direction and cross the border into Mexico with the help of a guide. This fact is emphasized in the dialogue.

Melquiades’s lack of origin is less baffling when viewed through the prism of the migration film EL NORTE. Within this context, it can be understood as relating to a political narrative and form of camouflage used by numerous refugees from Central and South America who were persecuted in their homelands and then say they are Mexican when caught trying to enter the United States. EL NORTE tells this story by taking two refugees from Guatemala as an example, who pretend to be Mexicans so as to be deported to Mexico instead of their home country.

Finally, there is the soldier-like depiction of the border patrol officer Mike Norton played by Barry Pepper, who is already connoted as such by his role in Steven Spielberg’s SAVING PRIVATE RYAN (USA 1998) and is also deployed in the same fashion in THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA.

The theme of different intersecting journeys was continued two years after the release of THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA in Fatih Akin’s film AUF DER ANDEREN SEITE / THE EDGE OF HEAVEN (D / TUR / I 2007). In Akin’s film, two corpses are transported by plane, one from Germany to Istanbul, and the other from Istanbul to Germany. These trips form the basis of a network of intercultural encounters; Guillermo Arriaga, the screenwriter of THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA, worked as a consultant on the film.17

The intertextual references are significant in this context, for they form part of the film’s playful approach to constructing history. First of all, they establish a basis for the fact that the film need not be narrated in a uniform manner and can both work with ellipses and create a strong sense of disorientation while simultaneously remaining anchored as a work with a specific political aesthetic before the matrix of other films. They also ensure that the film is able to develop its own theoretical discourse and in this case allow the significance of the sound space in particular to come to the fore while the narrative and visual spaces are both deconstructed. And finally, these references emphasize that the intertextual structure of film history inhabits a field of its own when it comes to playing with different constructions of history in that they reflect the various different ways in which something can be depicted narratively, visually and by means of sound, before the backdrop of all the actual, conceivable opportunities for constructing history offered by film aesthetics.

Conclusion

THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA is at once the story of various different journeys and the presentation of a theoretical discourse which takes the construction of historicity as its theme. Journeys characterize the film in the sense of a complex narrative structure that is crisscrossed by visual politics and sound-related interventions. The journeys in question relate to spatial-geographic movements within the United States as well as border crossings (United States–Mexico) with the attendant cultural practices of encounters and farewells. They include trips through time that are expressed via allusions to the Western genre and whose goal and ultimate destination is the burial of a cowboy. These journeys are not only narrated, they are also made visible and audible as specific audiovisual movements of bodies through different spaces and times. The film shows different views of the “other,” especially the beauty of the natural landscape of the border region between Texas and Mexico, allowing it to be experienced in acoustic terms by means of different sounds, animal voices, local music, and a musical score. This is linked to an aesthetic treatment of editing that in the first part of the film in particular undermines the reliability of spatiotemporal continuity for the viewer to a significant extent.

THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA depicts theoretical discourses in the sense that it plays with the different registers of text, image, and sound in the tradition of modern cinema. Furthermore, it refers to other films and makes special use of its knowledge of these films, establishing a cinematic intertexuality that also encompasses the registers of image and sound. THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA carries out various explicit operations on the genre of the Western and the migration film. The sort of traditional horseback journeys through inhospitable terrain familiar from the Western are, for example, contrasted with the contemporary, technologically advanced border patrols carried out by helicopters in the migration film genre (or the border patrol film18).

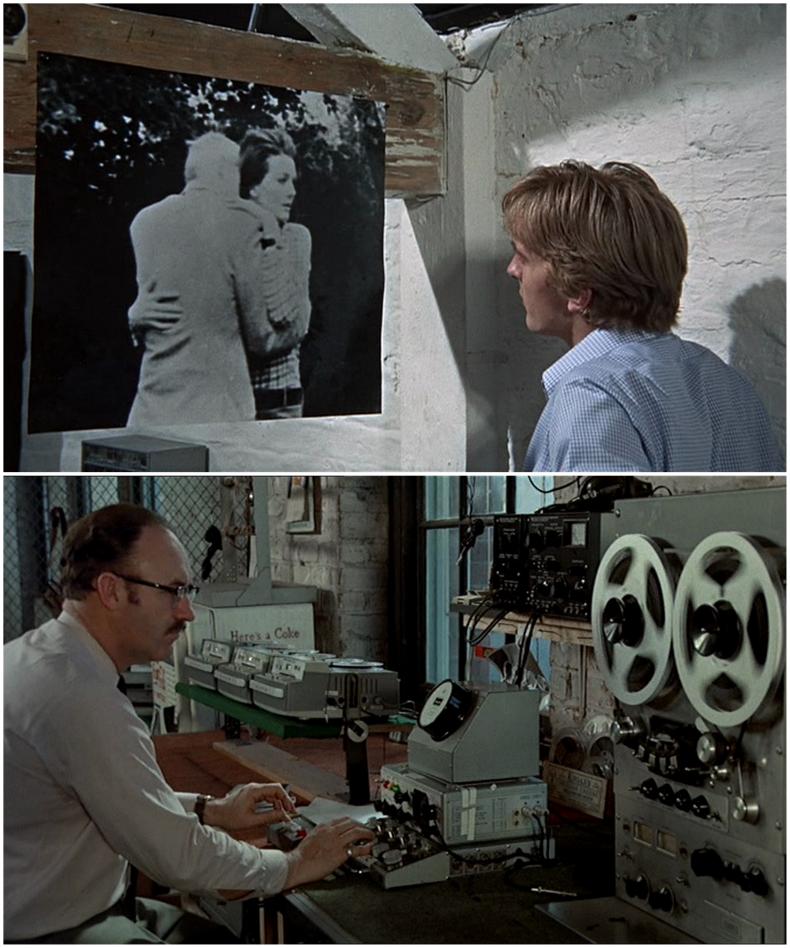

Furthermore, THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA contains numerous theory-based, media reflexive references to the construction of history which interrogate how knowledge is structured, whether in terms of texts and narratives or in terms of photographic, visual, and sound recordings. Examples of other films of a similar bent include Michelangelo Antonioni’s BLOW UP (UK / I / USA 1966), which inscribed a theoretical, philosophical discourse on photography into film history, and Francis Ford Coppola’s THE CONVERSATION (USA 1974), that achieved something similar for the theory of sound recording and sound production. Both films set up discursive reflections on media theory and form the basis from which THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA develops its own means of depicting how history is constructed first visually and then in terms of audio. THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA links back to these films and plays a complex theoretical game that operates according to the different hierarchies of knowledge comprised by cinema.

Yet my central point here is that the film is both aesthetically innovative and undeniably political. The film’s political aesthetic is primarily revealed in how it approaches its knowledge of cinema and of different journeys and the directions they take (migrant journeys, cowboys’ journeys). The aesthetic innovation here is how the film expands upon the experience of travel and its mediatizations in text and image by adding the additional dimension of a sound space into the mix. This sound space is given dramatic structure in a specific manner and established in opposition to the visual and narrative spaces.

The complex configuration of a sound space shaped by regional concerns is finally linked to the political understanding of a space of community. This space forms a clear counterbalance to the visual practices of control while also differing from the construction of a narrative and visual story, which the film eventually has peter out. The political aesthetic of the sound space of THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA is marked by polyphony and hybridity, linking together various sounds, animal voices, musical scores, and types of music. This enables a space of community to emerge as an open form on the soundtrack that is revealed to be a cultural practice of audio history.

Translated by Brian Currid, revised by James Lattimer

- 1The essay is a heavily revised version of a lecture held on September 21, 2013 at the conference “Versteckt – Verirrt – Verschollen: Reisen und Nicht-Wissen” at Universität Trier which was published under the title “Migration in den Klangraum: Zum Spiel mit Wissensordnungen in THREE BURIALS (USA/F 2005, R. Tommy Lee Jones)” in a collection of conference talks: Johannes Pause, Irina Gradinari, and Dorit Müller, eds., Reisen und Nicht-Wissen (Wiesbaden, 2015).

- 2See Hayden White’s Metahistory, along with his essay “Historiography and Historiophoty,” in The American Historical Review 93:5 (1988): 1193–1199.

- 3Coyote is not just the name of an American prairie wolf that the border patrol officers are still able to shoot legally in this film, but also the term used for the traffickers who lead illegal migrants across the Mexican border into the United States, see David Spener, Clandestine Crossings: Migrants and Coyotes on the Texas-Mexico Border (Ithaca, NY 2009).

- 4See Winfried Pauleit, “Im Medium Polaroid: Christopher Nolans Film MEMENTO als Fragment eines post-kinematografischen Möglichkeitsraums,” in Polaroid als Geste: Über die Gebrauchsweisen einer fotografischen Praxis, eds. Meike Kröncke et al. (Ostfildern-Ruit 2005), 66–73.

- 5See here Stephen Heath, “Narrative Space,” Screen 17 (1976), 19–75.

- 6For more on this subject, see Hermann Kappelhoff, “Der Bildraum des Kinos: Modulation einer ästhetischen Erfahrungsform,” in Umwidmungen: Architektonische und kinematografische Räume, ed. Gertrud Koch (Berlin 2005), 138–149.

- 7In our research project “Audio History: How Film Sound Produces History” at Universität Bremen, Rasmus Greiner, Mattias Frey, and I will be exploring the category of sound space as a complement to the concepts of narrative space and visual space, see Cooperation Centre Film, “Research Projects: Audio History: How Film Sound Produces History,” accessed March 13, 2015, http://www.film.uni-bremen.de/en/research/research-projects/audio-histo….

- 8This comment also refers the decline of the classical Western genre at the end of the 1960s and the early 1970s.

- 9Norteño is a popular regional music genre which combines Mexican-Spanish song traditions with waltz and polka influences from Germany and Poland, see here also Manuel Peña, The Texas-Mexican Conjunto: History of a Working-Class Music (Austin 1985); and Chris Strachwitz, “The Roots of Tejano and Conjunto Music” [1991], accessed March 13, 2015, www.lib.utexas.edu/benson/border/arhoolie2/raices.html. Me caí de la nube is also the name of a 1974 film by Arturo Martínez with Cornelio Reyna in the lead role. Alec Wilkinson wrote in The New Yorker about the contemporary band Los Tigres del Norte and makes reference to Strachwitz in characterizing norteño as a music of the lower classes and drunkards: “Norteño is the music made by the people who sustained the haciendas with their labor. It began to be recorded in the nineteen-twenties. The modern norteño band, built around the accordion, was established in Monterrey, in the fifties. The majority of Los Tigres’ songs are corridos . . . Corridos began to appear in northern Mexico in the eighteen-sixties and have a single reference, the border. They emerged to express the strife that ensued when a remote and unified territory was divided suddenly, following the Mexican War” (Alec Wilkinson, “Immigration Blues: On the Road with Los Tigres del Norte,” The New Yorker, May 24, 2010, 37).

- 10This technique of attaching a new connotation to existing music was already used during the 1940s in Charles A. Ridley’s Germany Calling, which appropriates German newsreel material and reedits shots of Hitler and the German military into a musical dance: see http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gYdmk3GP3iM.

- 11See Michel Chion, The Voice in Cinema, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York 1999) on the acousmatic voice. Three different levels of sound are usually delineated in reference to film: dialogue, noises, and music. Animal voices represent a special case here, as they can either be regarded as noises or dialogue. My conversations with various sound experts have confirmed this, but see also Sabine Nessel, “Die akusmatische Tierstimme in Luis Buñuels THE ADVENTURES OF ROBINSON CRUSOE,” Robinsons Tiere, eds. Roland Borgards et al. (forthcoming).

- 12The special trick here is that the disturbance is communicated via the character of Pete, who loses his voice over the course of the scene. Pete is played by Tommy Lee Jones, who was also the director of the film.

- 13On the history of the city of Jiménez, see Tour by Mexico, “Jimenez,” accessed March 13, 2015, http://www.tourbymexico.com/coahuila/jimenez/jimenez.htm; MiMunicipio, “Historia Jimenez Coahuila,” accessed March 13, 2015, http://www.mimunicipio.com.mx/historia/Coahuila/Jimenez. The mistake about the town name alludes to a lack of knowledge of Mexican history. But it also refers to the film’s musical sound space: the musician Flaco Jiménez accompanies the love scene in the hotel between Melquiades and Lou Ann Norton (the wife of the border patrol officer, played by January Jones) with the song “This Could Be the One.” Their love affair remains secret, and is thus not a reason why border patrol officer Norton might shoot Melquiades Estrada.

- 14A life that plays out between birth and the 50-centavo coin is one marked by abject poverty, considering that a single drink already costs 20 times that. A drink is bought in this scene for 10 pesos, and all the Mexican village dwellers say they have worked in the United States to make a living.

- 15See the information on the sound composition in THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA in: http://vimeo.com/10073975.

- 16In an interview, Tommy Lee Jones says he received the recordings personally from Linda Macaulay, who recorded the bird calls and built up an archive of birdsongs at Cornell University, see Museum of the Moving Image, “A Pinewood Dialogue with Tommy Lee Jones,” accessed March 13, 2015, http://www.movingimagesource.us/files/dialogues/2/68688_programs_transc…, 6f. The website for the archive can be found at http://www.birds.cornell.edu/page.aspx?pid=1676.

- 17Patricia Battle, “Interview: Fatih Akin: ‘Ich kann das Kino nicht neu erfinden!,’” September 20, 2006, accessed March 13, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20080423224002/http://www1.ndr.de/unterhalt….

- 18For more on the border patrol film, see Camilla Fojas, Border Bandits: Hollywood and the Southern Frontier (Austin 2008).

“A Pinewood Dialogue with Tommy Lee Jones,” Museum of the Moving Image, accessed March 13, 2015, http://www.movingimagesource.us/files/dialogues/2/68688_programs_transc…

Battle, Patricia. “Interview: Fatih Akin: ‘Ich kann das Kino nicht neu erfinden!,’” September 20, 2006, accessed March 13, 2015, https://web.archive.org/web/20080423224002/http://www1.ndr.de/unterhalt….

Chion, Michel. The Voice in Cinema, translated by Claudia Gorbman. New York 1999.

Fojas, Camilla. Border Bandits: Hollywood and the Southern Frontier. Austin 2008.

Heath, Stephen. “Narrative Space.” Screen 17 (1976): 19–75.

“Historia Jimenez Coahuila,” MiMunicipio, accessed March 13, 2015, http://www.mimunicipio.com.mx/historia/Coahuila/Jimenez.

"Jimenez,” Tour by Mexico, accessed March 13, 2015, http://www.tourbymexico.com/coahuila/jimenez/jimenez.htm.

Kappelhoff, Hermann. “Der Bildraum des Kinos: Modulation einer ästhetischen Erfahrungsform.” In Umwidmungen: Architektonische und kinematografische Räume, edited by Gertrud Koch. Berlin 2005.

Nessel, Sabine. “Die akusmatische Tierstimme in Luis Buñuels THE ADVENTURES OF ROBINSON CRUSOE.” In: Robinsons Tiere, edited by Roland Borgards et al. (forthcoming).

Pauleit, Winfried. “Im Medium Polaroid: Christopher Nolans Film MEMENTO als Fragment eines post-kinematografischen Möglichkeitsraums.” In Polaroid als Geste: Über die Gebrauchsweisen einer fotografischen Praxis, edited by Meike Kröncke et al. Ostfildern-Ruit 2005.

Peña, Manuel. The Texas-Mexican Conjunto: History of a Working-Class Music. Austin 1985. and

“Research Projects: Audio History: How Film Sound Produces History,” Cooperation Centre Film, accessed March 13, 2015, http://www.film.uni-bremen.de/en/research/research-projects/audio-histo….

Spener, David. Clandestine Crossings: Migrants and Coyotes on the Texas-Mexico Border. Ithaca, NY 2009.

Strachwitz, Chris. “The Roots of Tejano and Conjunto Music” [1991], accessed March 13, 2015, www.lib.utexas.edu/benson/border/arhoolie2/raices.html.

White, Hayden. Metahistory. The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth Century Europe. Baltimore 1975.

White, Hayden. “Historiography and Historiophoty.” The American Historical Review 93:5 (1988): 1193–1199 .

Wilkinson, Alec. “Immigration Blues: On the Road with Los Tigres del Norte.” The New Yorker, May 24, 2010.