Experiencing History in Film

An Empirical Study of the Link between Film Perception and Historical Consciousness

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Moller, Sabine: Experiencing History in Film: An Empirical Study of the Link between Film Perception and Historical Consciousness. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14783.

“We do not experience any movie only through our eyes. We see and comprehend and feel films with our entire bodily being, informed by the full history and carnal knowledge of our acculturated sensorium.” (Vivian Sobchack)1

“Is it possible to view history? . . . My answer is decidedly: no! It’s only possible to view so-called ‘facts’ . . . That is, if we take things precisely, a politically significant event or a personality of the past can be viewed in its political context, but we don’t see that the issue of the past conjured by the images have a historical significance.” (Jörn Rüsen)2

Fictional Film and Historical Consciousness

Fictional films based on history—films that seek to restage past times, events, and individuals—enjoy great popularity. Relevant publications on the issue generally assume that our current knowledge of history is primarily communicated by film, and not the schools.

As plausible as this might seem on first glance, it has been shored up by little concrete empirical evidence until now. Nearly a century ago, studies were already written on the “effects” of films like the war dramas THE BIRTH OF A NATION (USA 1915) or ALL QUIET ON THE WESTERN FRONT (USA 1930) that sought to test their hypotheses with experimental film screenings for schoolchildren.3 Currently, film is seen as promoting the increase of factual knowledge and the acquisition of skills.4 Despite the important partial results and inspirations that these studies have provided to date, they usually remain limited to several basic questions: does filmic fiction lead spectators to confuse them for historical reality? Do they mix facts and fiction? Do they consider filmic fictions real?

Indeed, distinguishing between reality and fiction is one of the major foundational elements in historical consciousness.5 History is an elaborated form of memory that reflects on its foundations by formulating questions and seeking sources that can be examined in terms of their relevance and perspective. And yet, historical consciousness is more than a collection of relevant empirical and narrative facts. Historical consciousness can be considered reflected when it does not fail to consider its own lifeworld conditions, which found the need for historical orientation.6 What we experience in the present, the problems with which we see ourselves confronted in our everyday life, what makes us unsure or lets us hope, all of this founds our questions for the past. Accepting this assumption of the historical theory, history didactics places a reflected and self-reflexive historical consciousness at the center of its efforts. That is, it targets an understanding that sees history as a construct shaped by the present, fundamentally dependent on our own national, generational, familial, and other frameworks. Competency in facts and methods and the examination of empirical soundness (“Is that real?”) with adept research and source criticism do not become obsolete, but back up such an understanding.

In a reductive orientation based on application, films are frequently seen merely as “containers” from which schoolchildren should take (correct) information. Answers to questions that account for the constructive foundations of the didactics of history, such as “How do spectators make sense of history in film?”, “How do their lifeworld conditions correspond with what film develops as history?”, are overlooked. In this light, the project presented in the following “Watching Contemporary History” understands itself as basic research exploring methods in the complex realm of media reception.

Project and Films

In my project “Watching Contemporary History,” I explore the question of how history is perceived and appropriated in fictional film.7 My project focuses on two films that were extraordinarily successful in both the German and the American context: the tragicomedies FORREST GUMP (USA 1994) and GOOD BYE LENIN! (D 2003). I chose these films because they re-stage decisive events in American and German history and because their importance, for both schoolchildren and adults alike, has been shown repeatedly in empirical studies.8 In these studies, the films themselves tend to be neglected: the films and their images play a subordinate role. But the focus of my interest is precisely on the appropriation of concrete scenes and images, that is, how spectators actively make media content “their own.”9 Here, I do not proceed by seeking to confirm hypotheses, generating and validating hypotheses from a close analysis of a film for its potential spectrum of effects. My goal instead is to take a look at the act of perception and appropriation in the research situation and to make it accessible for description and analysis.10

The film FORREST GUMP, which I will focus on here, is not just a twenty-year-old Hollywood blockbuster, but a phenomenon that remains controversial today.11 The main figure of the film, embodied by Tom Hanks, is a contemporary witness. Forrest Gump lives through decisive events of American history, influences them, and reports about his experiences to fellow passengers waiting at a bus stop. Due to his low IQ, he remains unaware of the historical significance of his experiences during his life. That’s the running gag of the film: the spectators can identify the historical subject matter and the historic figures, on which Forrest Gump reports in a highly unreliable way.12

FORREST GUMP earned more than half of its 677 million dollars in ticket sales outside the U.S.; in Germany alone, the film had more than 7.5 million viewers in 1994.13 Within the U.S., it was seen against the backdrop of the so-called “culture wars.” In this context, Forrest Gump (the character) was appropriated by the Republicans as an “avatar of ‘traditional values’”—which confirmed critics in their view that the film was reactionary.14 At the same time, already during the 1990s the film was seen as an expression of a specifically post-modern historical consciousness that ironically comments and reflects upon how the media shape memory and history.15 In 2011, FORREST GUMP was included in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress.16 Even two decades after its release, analyses and views of the blockbuster continue to vary widely.17 One of the controversies relates to the film sequence that I treated in my research project, which I will discuss below in more detail.

The Film Sequence and the Interviews

To pursue the levels on which spectators perceive history in film, I experimented with a variety of methods. One technique included playing two sequences from FORREST GUMP for my subjects (of various nationalities) in the U.S. and then to ask them to report what they saw.18 I selected those scenes that could reflect as many different aspects of plot and story as possible in condensed form in five to ten minutes.19

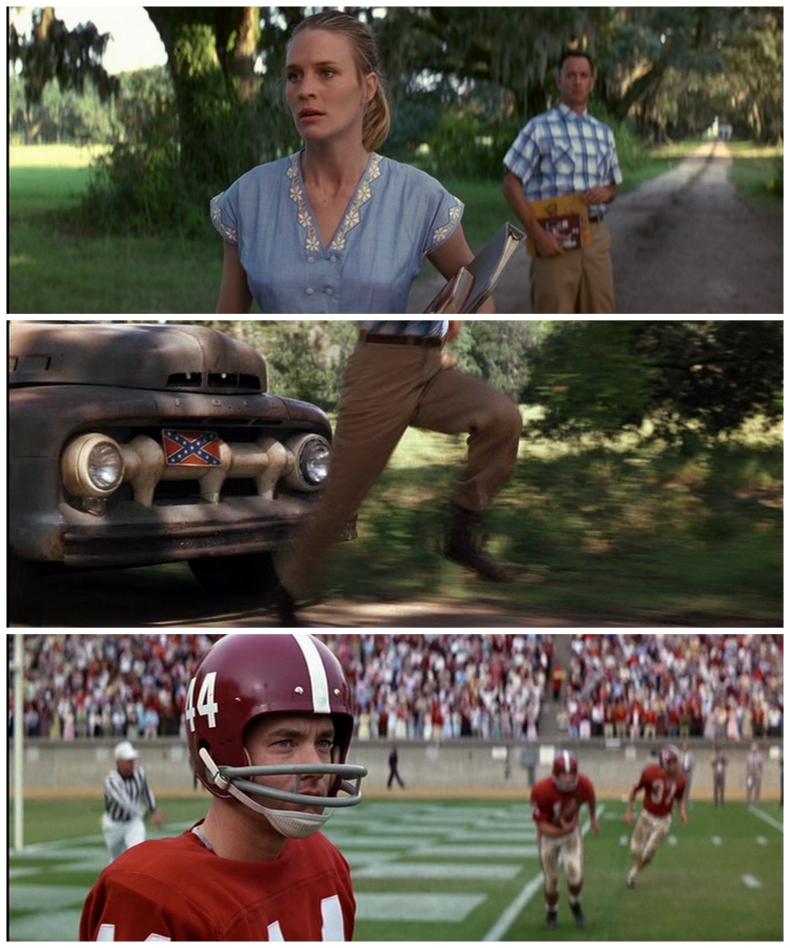

At the start of the sequence, Forrest Gump and his girlfriend Jenny (Robin Wright) are on the way home from high school in 1962, when a group of teenagers starts to make fun of Forrest, calling him an idiot, and throwing stones at him. Jenny tells Forrest to run—“Run, Forrest, run!”, the title of the sequence. Forrest first runs across a field and to a stadium close by. The football trainer is so impressed that he insures that Forrest becomes a member of his college team.

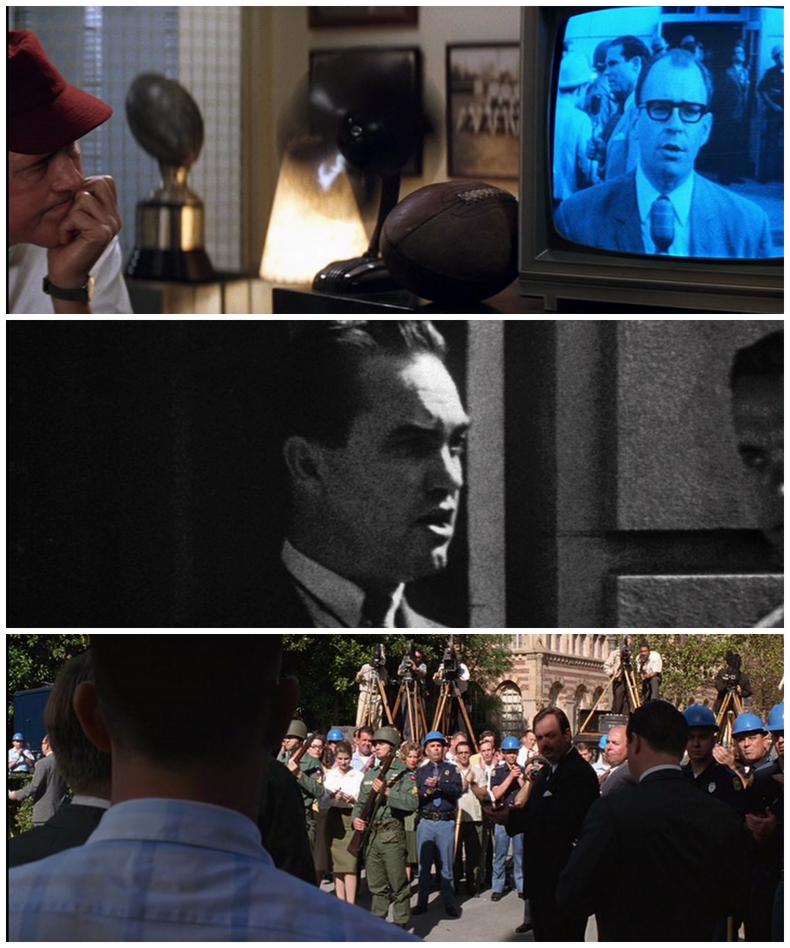

Then, an original news report from 1963 on the abolition of racial segregation at the University of Alabama is shown. First, we see a newsreader, then television spectators, before a historical scene at the entrance to the university is reenacted (the original commentary can be heard the entire time from off-screen). In front of the university are students, members of the National Guard, reporters, and the governor of Alabama, George Wallace, who seeks to block the abolition of segregation.

Forrest joins the students and asks what’s happening. A fellow student answers that the “coons” were trying to attend classes at the university. Forrest doesn’t understand the racist nature of the explanation or the (historical) meaning of the moment. He joins in the crowd and winds up in the first row of those protesting the abolition of segregation. One of the African American students the National Guard is protecting on her way to class drops her notebook as she walks by. Forrest picks it up and gives it to the student, whom he addresses as “Ma’am.” At the end of the sequence, Forrest Gump can be seen as the narrator of these events on the bench of a bus stop. Forrest Gump says goodbye to one of his listeners, an African American nurse (figs. 8–10).

After showing my interview partners the sequence on a laptop, I asked them five questions:

• What did you just see?

• What was the main idea behind the sequence?

• What does the film do to convey the idea?

• Do you have any questions about the sequence?

• What else came to mind while watching the sequence?20

The Interviews

I gathered interviewees in Germany and the U.S. via word of mouth: distributing information on my project as widely as possible, thus gaining volunteers. The selection of interviewees was based on a theoretical sampling as practiced in “grounded theory.”21 In this sense, cases are sought out that are as similar or different as possible and the ensuing interviews are contrasted and compared to one another. My sample includes interviews with both schoolchildren and history professors.

The example of a six-year old first grader attending an American school can show how spectators try to create a mental situation model for the film sequence. The boy’s first comment on the sequence was “Forrest Gump makes a touch down.” Children remember scenes from fictional films that are linked to sport: this was already shown in research on the effects of the media in the 1930s. 22 But when it came to a more concrete description of the scene that showed the abolition of racial segregation at the University of Alabama, the boy encountered difficulties. He tried to localize the events in time by asking, “Was Martin Luther King already born?”

This question can be explained by looking at how the American Civil Rights movement is depicted in children’s books and elementary school instruction in the U.S. In this context, the civil rights activists Martin Luther King, Jr. and Rosa Parks have become icons, as shown by surveys taken among pupils.23 The question about Martin Luther King refers in this sense to the motif of progress lying behind these historical narratives.24 The pupils recognize the historical importance of the original film documents due to their visual historicity (they are black and white and of poorer quality).25 They are also familiar with the historical context of racial segregation. Here, Martin Luther King, Jr. plays a central role; his work stands for the historical transformation that marks social progress in this history of the civil rights movement. Martin Luther King’s role has something of the “savior” function about it in American children’s picture books, which seems to resonate in the child’s question.

An American in her mid-20s who works as a therapist described the sequence as follows:

“I saw him running and from the beginning, chucked in few footballs in college and then historical relevance where he didn’t necessarily bind to the racial issues that were at hand and then by helping the woman with the book. . . . [his] seeming disability . . . would turn into a gift like his innocence is also a gift seemingly because he didn’t buy into all the racial stuff.”

The answer remains on a very abstract level and the complete absence of names, places, and times over the entire course of the interview reveals a distance to the historical events visualized in the film. The therapist emphasizes elsewhere in the interview how little she knows about history and how poorly she is able to remember dates and facts (she placed the historical events at the University of Alabama in the 1940s). Her lack of knowledge corresponds to her lacking sense of involvement, as is most clearly expressed in the words “racial stuff.” As a highly competent spectator, she can locate the scene and Forrest’s function. She is familiar with racial segregation as a socially important subject and the inclusion of historical documents for her indicates “historical significance,” just as they did for the six year old. But the film itself means nothing to her, and she cannot relate particularly to Forrest Gump nor to Tom Hanks. At the same time, this interview is also borne by a narrative of progress, but one that is not linked to the Civil Rights icons King or Parks, but rather to the presidency of Barack Obama: “I am like, now Obama is in the presidency so there has been some changes.”

In the German interviews as well, the expressions of those questioned communicate a sense of who speaks. Here, an outside perspective of American history is linked to a German interior perspective on the subject of racism and thus is linked with the Nazi past. Replying to the question of what he saw, a German political scientist answered as follows:

“The way Forrest Gump was first followed by three white racists with an ancient Dodge, I think with a confederate sticker, a confederate flag on the front, it’s clear that they mean trouble for him. He flees, and during his flight he winds up by accident in a baseball game, where he is discovered to be an excellent runner and becomes a baseball star.”

The Germans asked focused less on the progress narrative and they frequently confuse football and baseball. Characteristic here is that they include American racism in a highly moralized discourse where perpetrators and victims are clearly identified.26

Most interview partners in Germany and U.S. see the film in a positive light and remember it well; its rare to encounter indifferent viewers (like the American therapist) and it was difficult to find interview partners who saw the film as in the same critical light as academic film criticism. While the renewed viewing of the film sequence was shaped by my presence as an interviewer, as I will discuss in more detail below, the overall impression that the film left behind was largely independent of the interview situation. Most conversation partners already stated their view of the film before the interview, when asked.

Among the few critical takes on the film, the following remarks came from a Vietnam War expert:

“I think the main message is that Americans are happy-go-lucky people who fundamentally want to do right, but who somehow through their own sort of stupidity in a kind of nice way have ended up committing various crimes. It could even be the crime of racism and later the crime of entering Vietnam, but fortunately we have all gotten past that . . . Now they can sit on the bench together and the Rosa Parks figure can simply get on the bus having heard the whole story.”

The man in his mid-50s rejected the film fundamentally and subjected it to ideological critique. It is striking that already in this film sequence the view of intra-national racism is expanded by adding a foreign policy perspective. Seen against the backdrop of American interventionism in the past and present, the narrative of progress at the foundation of the film seems cynical.

On his interest in history, the Vietnam War expert said,

“I love the sensation of walking around in the present knowing enough about the past to be able to sort of see the present through the past.”

The person questioned thus saw himself as something of a counter-model to the figure of Forrest Gump, who is incapable of recognizing historical significance, either in the present or in the past.

Most of the viewers I questioned, in contrast, allowed the film’s dramaturgy to have its effect on them, seeing the world through the eyes of the unreliable or unknowing narrator. They philosophized about the possibility of basing social progress on ignorance and naïveté: stupidity as opening space for action. The war expert seems to refuse this mental experiment because it counters his concept of world experience. “Naïve” sympathy contradicts a hermeneutic practice of interpretation primarily based on historical knowledge.

Phenomenological approaches to film theory emphasize that the optical signs of the film—projection, camera shot, a moving body—are only provided with meaning by the film spectator, then becoming a visible sign. Attention, according to the American film scholar Vivian Sobchack, is like a creative act that is anchored in the concrete situation and the expectations of the viewing subject, filled with experience.27 Attention is thus both accidental and directed at the same time. The Address of the Eye is the title of one of Sobchack’s central works.

“ ‘Address’ is on the one hand the place where something is, at the same time it is the place attention is directed. ‘Eye’ and ‘I’ are homophones. For Sobchack, the ‘I’ as an embodied ‘eye’ has its place in the world, intentionally turns its attention to the world, and is also a site that can be addressed.”28

I would like to illuminate this intentional act of address—which affects film and history in general—using two interview examples. My interview partners included an African-American doctoral student of film studies. The interview with this film expert is more extensive and more reflected than many of the other interviews. His film studies expertise means that the doctoral student sees, remembers, and explicitly mentions more than the others. Beyond this expertise, however, it is the concern based on his physical presence in the world—the address of the I—that is expressed so clearly in this interview. In response to the question of what the main idea behind the film sequence screened, the doctoral student replies:

“You sort of see that bridge between Forrest then and Forrest now; interestingly he is wearing the same costume. So you see Forrest in the very beginning wearing the same costume who was being chased by these sort of redneck characters whose truck, I don’t know if you saw in the beginning, has a confederate flag in the front and now you see him now sitting sharing a bus stop and sharing a story with an African-American woman. So you start to see this sort of this progression that things are getting better or that things are better now the fact that he can tell the story to her on a shared bus stop. Now of course why is that important on a bus? The reason why the bus is important, the bus is important because I think there is a whole racial history around buses. So I don’t want to give the filmmakers too much credit but maybe to their credit, they put it on a bus stop intentionally to show, to implicate those politics. So we don’t have the Montgomery Bus Boycott on it for instance but we know Alabama, we know Montgomery, they are on the bus so even that side of it is implicated to sort of that racial history. So that’s one of the messages, things are better . . . I learned that times have changed by the very fact that I am in this school now giving this interview and you are German and you sort of have maybe two people who might not have been welcome in the early 60s in University of Alabama, so just sort of looking at my own contemporary moment.”

Revealing about this approach is first of all that the film sequence is described in a basically open, positive way. Equally striking—and also an expression of his professional point of view—is the variety of details that the film studies scholar recalls, interprets in terms of their symbolism, and explains. The aspect to which he pays the most attention has to do with the framing plot: the action, how and where Forrest Gump tells his story:

The film expert here enters into a dialogue with the filmmaker: while he knows that the Montgomery Bus Boycott that Rosa Parks participated in is not explicitly present in the film, he assumes that it is alluded to on a symbolic level, because he anticipates that the filmmaker could expect that the (American) spectators would recognize the right symbols and generate the historical events in their memory (“we know Montgomery”). Based on the fact that Forrest Gump tells his story to an African-American woman, the film studies scholar interprets this tagging as a message that emphasizes progress and its historical achievements, which he calls “racial history.” In the 1950s, black and white passengers in the south of the U.S. could not sit next to one another on a bus, in the 1980s it is normality for them to be sitting together at a bus stop and telling their stories to one another. The film studies expert transfers this historical reading to the interview situation and thus picks up the content of Forrest Gump’s narrative.

While during the 1960s black students were not welcome at American universities in the South, now, fifty years later, they naturally can sit in a seminar room of an American university and hold an interview. The interpersonal character of the interview situation here becomes explicit: the film studies scholar broadens the group of people who would have had difficulty studying during the 1960s at the University of Alabama to include me: from a country that was responsible for the Second World War and the Holocaust.29 The decisive impulse to read this film sequence in this way is based on the present and the interview constellation is linked on various levels to the historical setting of the film plot. Here, it is significant that the film studies scholar subsumes the event under the term “racial history.” This perspective does not suggest addressing me as a female interviewer and to look at the role of women in this period. His perspective on history is not only lengthened by his perception of the film, but also in his perception of the conversation situation in the present.

The perspectival nature of the perception of history in the film becomes even clearer when we add the comments of a historian who sees the film as treating what for her represents an important aspect of the Civil Rights movement. The historian, unlike the doctoral student, has her own memories of the period. She gave the following answer to the question of what she saw:

“Well, it's a painful moment in American history, and Forrest Gump's innocence makes clear how difficult that time was. He looks at it very naively, he doesn't really see race and racism, he is not understanding, what this moment in time meant, and it was so incredibly significant. You know, I think I know it so well, I know that in the civil rights era so well . . . and it's not just prejudice against blacks, it's also prejudice against anyone who isn't considered to be normal, which is white, male, and middle class.”

Her description of Forrest Gump suggests immediately that she sees the character in a positive light and has a certain sympathy for him (“naïve,” “innocence”). The statement that the period is so familiar to her, which she repeats and makes more concrete, could be interpreted as asserting a biographical link beyond her professional experience. This interpretation is also supported by the following comments: at issue here is racism and prejudice. But prejudice not only affected African Americans, but all those who were not white, male, and middle class. She thus locates herself, but also her female conversation partner in the historical setting. The term “civil rights era” marks her perspective on this period in history, which extends into the perception of history in the film itself. The historian sees the film sequence above all as a depiction of the 1960s in the U.S. and looks here at a woman who struggled to make her way through the university.

I interviewed the historian later once more, two weeks later, without an appointment: I sought her out in her office and asked what she remembered about our interview. She responded:

“It's hard to say because I have seen it so many times, but I think one of the most memorable parts is Forrest Gump running along the field and then morphing into a football player. I liked the way that was done. And then I loved him coming out of the crowd and picking up the book and handing it to the black woman, young woman, who is entering the school.”

In this answer, a general, imprecise recollection30 of a film where digital image manipulations are a characteristic technique mixes with the subjectively significant focusing of attention, the address of the eye that also marked the previous interview situation.

Conclusion

Films communicate material that relies on the spectators’ processes of appropriation. Appropriations are pre-structured by film: but they are realized however in acts of creating significance that refer to the respective lifeworld or cultural context of the spectator.31 This view can be derived from several approaches to media theory or film studies and can be transferred to the appropriation of history as well. For history per se is incomplete; it can, as Jörn Rüsen und Vivian Sobchack have emphatically pointed out, only take place in the present. Readings and attributions of meaning that are placed in the past cannot be extended smoothly into the present. It requires the act of re-appropriation that accompanies an act of re-inscription, socially and culturally as well as individually and neuronally. A spectator who saw the film FORREST GUMP against the backdrop of the presidency of Bill Clinton or George W. Bush sees the film in a different light than those, like the spectators asked, who saw the film against the backdrop of the first African American president, Barack Obama. Someone who saw the film as a child will view the film in a new way as an adult with children of his or her own, just as it makes a difference whether the film is seen in the dark cinema, in the family circle with the home television, or in excerpts in the presence of a German interviewer. All of these factors, which help to shape the appropriation of media, cannot be defined on an individual level. At the same time, due to their representative function and formation of symbols, films are also always sources, “in which the images of humanity that circulate in a society are reflected.”32 FORREST GUMP is a film that explores American racism, that can be read as a document of a society that is trying to define itself as “post-racist.”33 In this sense, the images and sounds of the film and its constructions of figures and plot can be analyzed, in so doing distilling shifts and gaps. In the case of the film FORREST GUMP, this has taken place hundreds of times, but as a result repeatedly leads to diametrically opposed readings. In light of the premises presented here, both historical and film-theoretical, this is not very surprising.

Against the backdrop of approaches to film in history didactics, the interviews presented above can be understood as a challenge to reconceptualize the German theory of history, usually insensitive to the media, against the backdrop of somatic film theory.34 Intellectual understanding and cognitive ability are thus complemented with a physical component. A modification in the same direction was demanded almost 20 years ago by the Dutch historian Frank Ankersmit, when he looked at German history studies against the backdrop of Aristotle’s theory of experience.35 At its core, such an approach does not seek to replace historical thought with a naïve presentism, which remains caught with one’s own associations, without expanding the horizon. Rather, it is about setting historical representation and historical experience in a relationship to one another. A film represents a history that rests on virtuosically staged symbols and visual icons. Temporal and cultural contextualization serve as basis for historical representation, which is always hermeneutic. It relies on mutual listening, which refers both to historical debate and to our own historical knowledge. If we follow Frank Ankersmit, historical experience, in its directness, in its episodic and decontexualizing character, runs counter to historical representation. Historical experience is always immediate and thus founds a new history, through which the history of others is set in relationship to our own experiences. This individually, situationally told story is a link in a much wider intertextual fabric, which includes not only immediate and unique conditions of empirical narrative situations but also very general and transsituational models of perception and interpretation. The intersubjective linkages that are articulated in conversation on (film) images are not a preliminary stage before the “objective” interpretation of film images, but show how history takes place in the consciousness of the spectators. In terms of a reflected historical consciousness, this requires understanding film in its quality as a living medium and taking it seriously.

Translated by Brian Currid

- 1Vivian Sobchack, “What My Fingers Knew: The Cinesthetic Subject, or Vision in the Flesh,” Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture (Berkeley 2004), 63.

- 2Jörn Rüsen, “Geschichte sehen: Zur ästhetischen Konstitution historischer Sinnbildung,” Auf der Suche nach dem verlorenen Staat. Die Kunst der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR, ed. Monika Flacke (Berlin 1994), 29.

- 3See the research overview: Sabine Moller, “Movie-Made Historical Consciousness: Empirische Antworten auf die Frage, was sich aus Spielfilmen über die Geschichte lernen lässt,” Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 64.7–8 (2013): 389–404.

- 4See for example Andrew C. Butler, Franklin M. Zaromb, Keith B. Lyle et al., “Using Popular Films to Enhance Classroom Learning: The Good, the Bad, and the Interesting,” Psychological Science 20.9 (2009): 1161–1168.

- 5See Hans-Jürgen Pandel, “Dimensionen des Geschichtsbewusstseins. Ein Versuch, seine Struktur für Empirie und Pragmatik diskutierbar zu machen,” Geschichtsdidaktik 12.2 (1987): 130–142.

- 6See Bodo von Borries, Historisch Denken Lernen: Welterschließung statt Epochenüberblick. Geschichte als Unterrichtsfach und Bildungsaufgabe (Opladen 2008).

- 7See Sabine Moller, Zeitgeschichte sehen: Die Aneignung von Vergangenheit durch Filme und ihre Zuschauer (Berlin 2018).

- 8See on this Sabine Moller, “Spielfilme als Blaupausen des Geschichtsbewusstseins. GOOD BYE LENIN! aus deutscher und amerikanischer Perspektive,” Zeitgeschichte - Medien - Historische Bildung, eds. Susanne Popp / Michael Sauer / Bettina Alavi (Göttingen 2010), 239–253. A study that shows the significance of FORREST GUMP: Sam Wineburg, Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past (Philadelphia 2001).

- 9I am using the concepts of “media” and “communicative appropriation” as developed by qualitative media research. See Andreas Hepp, “Kommunikative Aneignung,” Qualitative Medienforschung: Ein Handbuch, ed. Lothar Mikos and Claudia Wegner (Constance 2005), 67.

- 10In theoretical terms, I take the premises of an interactionist social psychology as my starting point, according to which people act on the basis of meanings that they attribute to people and things. Attention here is directed at everyday attributions of meaning and everyday actions. This perspective represents a special challenge for empirical research, since as a researcher I always penetrate the everyday context and change it due to my presence. The participation of the researcher in the events cannot be avoided, but it can be made a subject of research with self-reflexive empirical methods, such as hermeneutic dialogue analysis. On the premises in communication theory, see Harald Welzer, “‘Ist das ein Hörspiel?’: Methodologische Anmerkungen zur interpretativen Sozialforschung,” Soziale Welt 46.2 (1995): 181–196; and Harald Welzer, Transitionen: Zur Sozialpsychologie biographischer Wandlungsprozesse (Tübingen 1993); Olaf Jensen, “Zur gemeinsamen Verfertigung von Text in der Forschungssituation,” FQS 1.2 (2000), accessed March 12, 2015, www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/rt/printerFriendly/1080/2355.

- 11In February 2014, the news portal abcnews.com had its readers choose the best oscar winners of the past 64 years. The favorite film chosen was FORREST GUMP. A different media portal commented: “Possibly Confused Readers Name FORREST GUMP Best Oscar Victor of Last 64 Years.” Perhaps, according to the commentary, the survey participants thought they were supposed to choose the film that most closely expressed the worldview of the conservative former president Ronald Reagan. A. A. Dowd, “Newswire. Possibly Confused Readers Name FORREST GUMP Best Oscar Victor of Last 64 Years,” A.V. Club [2014], accessed March 12, 2015, www.avclub.com/article/possibly-confused-readers-name-forrest-gump-best….

- 12FORREST GUMP is considered a film prototype of the unreliable narrator: see Michaela Krützen, Dramaturgien des Films: Das etwas andere Hollywood (Frankfurt am Main 2010), 35.

- 13See Box Office / Business for FORREST GUMP. In: IMDb, accessed March 12, 2015, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0109830/business?ref_=tt_dt_bus.

- 14See James A. Burton, “Film, History and Cultural Memory. Cinematic Representations of the Vietnam-Era during the Culture Wars, 1987–1995,” Diss. Nottingham, 2007, 223, accessed March 12, 2015, http://etheses.nottingham.ac.uk/493/; See also Oliver Gruner, “Public Politics / Personal Authenticity. A Tale of Two Sixties in Hollywood Cinema, 1986–1994,” Diss. East Anglia, 2010, accessed March 12, 2015, https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/31696/.

- 15See Vivian Sobchack, “Introduction: History Happens,” The Persistence of History: Cinema, Television and the Modern Event (New York 1996), 1–14; Almuth Hoberg, Film und Computer (Frankfurt am Main 1999).

- 16See National Film Registry Titles 1989–2013. In: National Film Preservation Board, accessed March 12, 2015, http://www.loc.gov/film/registry_titles.php.

- 17While Thomas Elsaesser praised the film in 2009 for deconstructing the mediacy of collective memory, media studies scholar Steve F. Anderson criticized this film in 2011 as a clear example of revisionist historiography. Referring to the film sequence that is also central to this contribution, Anderson writes that no reasonable spectator could overlook the revisionist character of Forrest Gump: the film was about erasing the contribution of African Americans to American history. See Steve F. Anderson: Technologies of History. Visual Media and the Eccentricity of the Past (Hanover, NH 2011), 32. Thomas Elsaesser “Geschichte(n), Gedächtnis, Fehlleistungen. Forrest Gump,” Hollywood heute: Geschichte, Gender und Nation im postklassischen Kino (Berlin 2009), 181–192.

- 18In empirical terms, my research can be traced back to the study of British psychologist Sir Frederic Bartlett. In a classical experiment from the 1930s, Bartlett presented unknown stories to his subjects and then asked them (after certain periods of time) to retell them. See Frederic Bartlett, Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology (London 1932). For similar approaches, see Peter Seixas, “Popular Film and Young People‘s Understanding of the History of Native American-White Relations,” The History Teacher 26:3 (1993): 351–370; and Torsten Koch and Harald Welzer, “Weitererzählforschung. Zur seriellen Reproduktion erzählter Geschichten,” Leben/Erzählen: Beiträge zur Biographie- und Erzählforschung, ed. Thomas Hengartner and Brigitta Schmidt-Lauber (Berlin 2004), 165–182.

- 19See Lothar Mikos, Film- und Fernsehanalyse (Constance 2005).

- 20These questions are flanked by the film sequences with concluding questions on historical films and the viewing habits as well as a demographic survey and questions about memory. The transcribed interviews were analyzed using the foundation of hermeneutic dialog analysis with the help of text analysis software MAXQDA.

- 21See Juliet Corbin and Anselm Strauss, “Grounded Theory Research. Procedures, Canons, and Evaluation Criteria,” Qualitative Sociology 13.1 (1990): 3–21; Antony Bryant and Kathy Charmaz (eds.), The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory (London 2007).

- 22See Moller, “Movie-Made Historical Consciousness,” 392.

- 23See Sam Wineburg and Chauncey Monte-Sano, “‘Famous Americans’: The Changing Pantheon of American Heroes,” The Journal of American History 94.4 (2008): 1186–1202.

- 24See Michael Schudson, “Telling Stories about Rosa Parks,” Contexts 11.3 (2012): 22–27.

- 25Jamie Baron studied this and called it the “archive effect.” This effect is the result of temporal difference in the perception of the spectator, a then-versus-now effect generated in an individual text. Baron proposes an epistemological effect: the spectator experiences the film material through the “real” past. See Jamie Baron, The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History (London 2014), 18.

- 26See on this Sabine Moller, “Possibly Confused Viewers. Zur Aneignung von Geschichte im Blockbuster Kino,” Kulturelle Aneignung von Vergangenheit, eds. Sabine Moller and Matthias Bauer (special issue, Literatur in Wissenschaft und Unterricht, forthcoming).

- 27See Vivian Sobchack, “The Active Eye: A Phenomenology of Cinematic Vision,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video 12.3 (1990): 27.

- 28Dimitri Liebsch, “Wahrnehmung, Motorik, Affekt. Zum Problem des Körpers in der phänomenologischen und analytischen Filmphilosophie,” Image 17.1 (2013): 107.

- 29He is supposedly referring there to a comment made by George Wallace, who dismissed the accusation of his critics that he was a racist by saying that he was already killing Nazis when his critics were still wearing diapers. See Aubrey J. Sher, Presidential Hopefuls (1788–2008): Who Won, Who Lost, and Why (Bloomington 2008), 372.

- 30Here, the film does not transform Forrest Gump into a football player using digital techniques of de-familiarization (morphing), but using editing techniques.

- 31For a foundational discussion of this issue, see Mikos, Film- und Fernsehanalyse. Jörg Schweinitz, Film und Stereotyp: Eine Herausforderung für das Kino und die Filmtheorie (Berlin 2006), 3.

- 32See Elsaesser, “Geschichte(n), Gedächtnis, Fehlleistungen.”

- 33See on this Jakob Krameritsch’s critique of the historical theory of Jörn Rüsen, “Die fünf Typen des historischen Erzählens − im Zeitalter digitaler Medien,” Zeitgeschichte - Medien - Historische Bildung, 261–281.

- 34See Frank R. Ankersmit, Die historische Erfahrung (Berlin 2012). In the work of Roland Barthes as well, a similar movement can be seen in the engagement with (historical) images when he seeks to complement the studium—the cultural contextualization—with the punctum, the moment of individual impact: see Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida, trans. Richard Howard (New York 1984). Bettina Henzler applied Barthes’ reception theory for photographs and film stills to the moving image: see Filmästhetik und Vermittlung: Zum Ansatz von Alain Bergala. Kontexte, Theorie und Praxis (Marburg 2013), 120–137.

- 35See especially the approach in Bettina Henzler, “Ich, Du, Er, Sie, Es. Intersubjektivität in der Filmvermittlung,” Vom Kino lernen: Internationale Perspektiven der Filmvermittlung, eds. Bettina Henzler, Winfried Pauleit, and Christine Rüffert (Berlin 2010), 66–77.

Anderson, Steve F. Technologies of History. Visual Media and the Eccentricity of the Past. Hanover, NH 2011.

Ankersmit, Frank R. Die historische Erfahrung. Berlin 2012.

Baron, Jamie. The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History. London 2014.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida, translated by Richard Howard. New York 1984.

Bartlett, Frederic. Remembering: A Study in Experimental and Social Psychology. London 1932.

Box Office / Business for FORREST GUMP. In: IMDb, accessed March 12, 2015, http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0109830/business?ref_=tt_dt_bus James A. Burton, “Film, History and Cultural Memory.

Bryant, Antony and Kathy Charmaz (eds.). The SAGE Handbook of Grounded Theory. London 2007.

Butler, Andrew C. / Zaromb, Franklin M. / Lyle, Keith B. et al. “Using Popular Films to Enhance Classroom Learning: The Good, the Bad, and the Interesting.” In: Psychological Science 20.9. (2009).

Cinematic Representations of the Vietnam-Era during the Culture Wars, 1987–1995,” Diss. Nottingham, 2007, 223, accessed March 12, 2015, http://etheses.nottingham.ac.uk/493/.

Corbin, Juliet and Anselm Strauss. “Grounded Theory Research. Procedures, Canons, and Evaluation Criteria.” In: Qualitative Sociology 13.1 (1990).

Dowd, A. A. “Newswire. Possibly Confused Readers Name FORREST GUMP Best Oscar Victor of Last 64 Years,” A.V. Club [2014], accessed March 12, 2015. www.avclub.com/article/possibly-confused-readers-name-forrest-gump-best….

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Geschichte(n), Gedächtnis, Fehlleistungen. Forrest Gump.” In: Hollywood heute: Geschichte, Gender und Nation im postklassischen Kino. Berlin 2009.

Gruner, Oliver. “Public Politics / Personal Authenticity. A Tale of Two Sixties in Hollywood Cinema, 1986–1994.” In: Diss. East Anglia, 2010, accessed March 12, 2015, https://ueaeprints.uea.ac.uk/31696/

Henzler, Bettina. Filmästhetik und Vermittlung: Zum Ansatz von Alain Bergala. Kontexte, Theorie und Praxis. Marburg 2013.

Henzler, Bettina. “Ich, Du, Er, Sie, Es. Intersubjektivität in der Filmvermittlung.” In: Vom Kino lernen: Internationale Perspektiven der Filmvermittlung, edited by Bettina Henzler, Winfried Pauleit, and Christine Rüffert. Berlin 2010.

Hepp, Andreas. “Kommunikative Aneignung.” In: Qualitative Medienforschung: Ein Handbuch, edited by Lothar Mikos and Claudia Wegner. Constance 2005.

Hoberg, Almuth. Film und Computer. Frankfurt am Main 1999.

Jensen, Olaf. “Zur gemeinsamen Verfertigung von Text in der Forschungssituation,” FQS 1.2 (2000), accessed March 12, 2015. www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/rt/printerFriendly/1080/2355.

Koch, Torsten and Harald Welzer. “Weitererzählforschung. Zur seriellen Reproduktion erzählter Geschichten.” In: Leben/Erzählen: Beiträge zur Biographie- und Erzählforschung, edited by Thomas Hengartner and Brigitta Schmidt-Lauber. Berlin 2004.

Krameritsch, Jakob. “Die fünf Typen des historischen Erzählens − im Zeitalter digitaler Medien.” In: Zeitgeschichte - Medien - Historische Bildung.

Krützen, Michaela. Dramaturgien des Films: Das etwas andere Hollywood. Frankfurt am Main 2010.

Liebsch, Dimitri. “Wahrnehmung, Motorik, Affekt. Zum Problem des Körpers in der phänomenologischen und analytischen Filmphilosophie.” In: Image 17.1 (2013).

Mikos, Lothar. Film- und Fernsehanalyse. Constance 2005.

Moller, Sabine. “Movie-Made Historical Consciousness: Empirische Antworten auf die Frage, was sich aus Spielfilmen über die Geschichte lernen lässt.” In: Geschichte in Wissenschaft und Unterricht 64.7–8. (2013).

Moller, Sabine. “Possibly Confused Viewers. Zur Aneignung von Geschichte im Blockbuster Kino.” In: Kulturelle Aneignung von Vergangenheit, eds. Sabine Moller and Matthias Bauer (special issue, Literatur in Wissenschaft und Unterricht, forthcoming).

Moller, Sabine. “Spielfilme als Blaupausen des Geschichtsbewusstseins. GOOD BYE LENIN! aus deutscher und amerikanischer Perspektive.” In: Zeitgeschichte - Medien - Historische Bildung, edited by Susanne Popp / Michael Sauer / Bettina Alavi. Göttingen 2010.

Moller, Sabine. Zeitgeschichte sehen: Die Aneignung von Vergangenheit durch Filme und ihre Zuschauer. Berlin 2018.

"National Film Registry Titles 1989–2013." In: National Film Preservation Board, accessed March 12, 2015, http://www.loc.gov/film/registry_titles.php

Pandel, Hans-Jürgen. “Dimensionen des Geschichtsbewusstseins. Ein Versuch, seine Struktur für Empirie und Pragmatik diskutierbar zu machen.” In: Geschichtsdidaktik 12.2 (1987).

Rüsen, Jörn. “Geschichte sehen: Zur ästhetischen Konstitution historischer Sinnbildung.” In: Auf der Suche nach dem verlorenen Staat. Die Kunst der Parteien und Massenorganisationen der DDR, edited by Monika Flacke. Berlin 1994.

Schudson, Michael. “Telling Stories about Rosa Parks.” In: Contexts 11.3 (2012).

Schweinitz, Hörg. Film und Stereotyp: Eine Herausforderung für das Kino und die Filmtheorie. Berlin 2006.

Seixas, Peter. “Popular Film and Young People‘s Understanding of the History of Native American-White Relations.” In: The History Teacher 26:3 (1993).

Sher, Aubrey J. Presidential Hopefuls (1788–2008): Who Won, Who Lost, and Why. Bloomington 2008.

Sobchack, Vivian. “Introduction: History Happens.” In: The Persistence of History: Cinema, Television and the Modern Event. New York 1996.

Sobchack, Vivian. “The Active Eye: A Phenomenology of Cinematic Vision.” In: Quarterly Review of Film and Video 12.3 (1990).

Sobchack, Vivian. “What My Fingers Knew: The Cinesthetic Subject, or Vision in the Flesh." In: Carnal Thoughts: Embodiment and Moving Image Culture. Berkeley 2004.

Von Borries, Bodo. Historisch Denken Lernen: Welterschließung statt Epochenüberblick. Geschichte als Unterrichtsfach und Bildungsaufgabe. Opladen 2008.

Welzer, Harald. “‘Ist das ein Hörspiel?’: Methodologische Anmerkungen zur interpretativen Sozialforschung.” In: Soziale Welt 46.2 (1995)

Welzer, Harald. Transitionen: Zur Sozialpsychologie biographischer Wandlungsprozesse. Tübingen 1993.

Wineburg, Sam and Chauncey Monte-Sano. “‘Famous Americans’: The Changing Pantheon of American Heroes.” In: The Journal of American History 94.4 (2008).

Wineburg, Sam. Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past. Philadelphia 2001.