Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Kramer, Sven: Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14782.

In recent decades filmmakers, film scholars, and historians have modified their understanding of how to work with documentary film images. Robert A. Rosenstone identified one of the main assumptions of the new perspective as early as 1988:

"The apparent glory of the documentary lies in its ability to open a direct window onto the past, allowing us to see the cities, factories, landscapes, battlefields, and leaders of an earlier time. But this ability also constitutes its chief danger. However often film uses actual footage [...] from a particular time and place to create a ‘realistic’ sense of the historical moment, we must remember that on the screen we see not the events themselves, and not the events as experienced or even as witnessed by participants, but selected images of those events carefully arranged into sequences to tell a story or to make an argument."1

Subsequently, all-too-simple oppositions in film studies—the advocacy of either the image-based reproduction of facts 'or' the staging of reality—yielded to more complex models showing the ineluctable interconnectedness of cinema’s ontological properties.

It took some time for these kinds of ideas to find their way into the study of history; that discipline first had to debate what sort of status such images would have in their work. In 2003 Günter Riederer challenged German historians to recognize films as entirely valid sources for historical research, but also to appropriate theories and techniques for analyzing images and films that had developed in other disciplines. Riederer believed that this “technique of reading film”2 should be established as ancillary discipline of historiography.

Today the question for both filmmakers and humanities scholars alike is how to read cinematographic images emanating from the past. Hence, more and more attention is being paid to the act of reading; there is an increasing amount of reflection upon the role of the audience, and more emphasis on how to productively appropriate images. The following will inquire into the aesthetic solutions used by two more recent documentary and essay films, which self-reflexively deliberate on the complications of appropriating film images recorded during the National Socialist period. Also up for debate are the different ways of writing history that ensue when practiced either by scholars on the one hand, or by filmmakers on the other: Where do their methods intersect, and where do they diverge?

When these questions are applied to the Shoah, it is obvious that several specific problems arise. The Nazis did not document the mass murders on film; only a few visual documents of the ghettos, camps, and firing squad locations have survived. In the case of narrative films—Steven Spielberg’s SCHINDLER’S LIST (USA 1993), for instance—discussions have focused on whether or not murderous events should be represented, and, if so, how graphic the depictions should be. Are dramatic films that adhere to historical facts still historically ‘true’, despite the fact that their images are invented? Spielberg’s film rhetoric immediately suggests this; major sections of his work evince a close attention to detail and other gestures of “authenticity,”, thereby emphasizing the connection between historical events and narrated story.3

In general, the documentary film is confronted with the task of assessing what has been handed down from the past, more than any other forms. Since there are hardly any recordings from the National Socialist era, the collective visual memory of the Shoah is mainly supported by the images recorded by the Allies 'after' the liberation. Ulrike Weckel has recently shown how these recordings fulfill a pedagogical and evidentiary function in the way that they document the camps’ existence in a postwar German society characterized by denial. Moreover, Weckel—joining Cornelia Brink, Dagmar Barnouw, and others—has also read a certain volition in the visual construction of the images and the ways they were distributed, which Weckel interprets as the “intentional shaming”4 of the defeated Germans. The fact that the gesture of proof is amalgamated with a gesture of shaming—meaning, that evidence and a moral perspective are combined—can be seen, for example, in the prosecution’s presentation of the film NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMPS (USA 1945) during the Nuremberg trials on November 29, 1945. She states that it served the purpose of “publically shaming . . . the defendants more than any other concentration camp film shown to German prisoners of war or civilians had.”5

Early compilation films and many that followed were based on the Allies’ recordings and retained the latter’s original purpose: to bear witness. The realization that even such images did not contain the truth of events per se, but had an inherent sense of perspective, caused filmmakers and theorists to pay closer attention to the few documents that were filmed in the camps while they were in operation. Georges Didi-Huberman vehemently supported the idea that the singular images taken by members of the 'Sonderkommando' (special unit) in Auschwitz, at the risk of their own lives, should be acknowledged as depictions of the Shoah, and not dismissed with the argument that it is impossible to depict the Shoah visually (fig. 1). Simply 'wanting' to depict it must be evaluated as something positive:

“The photographs snatched from Auschwitz . . . were also, therefore, four refutations snatched from a world that the Nazis wanted to obfuscate, to leave wordless and imageless.”6

Didi-Huberman realized that these images also owed something to a perspective: he identified them as acts of resistance.

Whereas these images of prisoners were recorded in secret, some filmmakers make use of historical images that were created with the more or less forced cooperation of the inmates. They add a new dimension to the archives of historical images from the Nazi era. And while the task of working out the “historical truth” is still, to this day, a principal motivation, the filmmakers also engage with the ambivalent nature of these images into the works themselves. Whose perspective do these surviving records portray? The perspective of the Nazis, or of the prisoners? Two newer films about the Warsaw ghetto and the Westerbork transit camp deploy different means of appropriating material from the past.

SHTIKAT HAARCHION / A FILM UNFINISHED (GERMANY / ISRAEL 2010), Yael Hersonski’s 2010 Israeli-German documentary makes use of National Socialist footage filmed in the the Warsaw ghetto in May 1942. Although it is not known precisely how this material was supposed to be used, the intentions were indisputably propagandistic. It is not only obvious from the sequences themselves; other sources confirm this ultimate purpose. However, the Nazis only produced a raw edit of the ghetto film and then neglected to pursue the project further. The reels of film were discovered in East Germany in 1954, and more footage came from other sources later. In the beginning sequence of her film, Hersonski looks at how individual scenes were used after 1954:

“After they were discovered, the film sequences were regarded as illustrations of real life in the ghetto and hence were employed as such in documentation, and also archived in museums.”

The filmmaker criticizes this indiscriminate use of the images, commenting in her film: “The propaganda material was turned into historical truth.” In turn, this procedure leads Hersonski to fundamental questions: “But what do these pictures actually show? And what are they not showing?”

This critical process of dealing with historical images is common to all of the more recent films that make use of this material and should be taken seriously. It is clear to all of the filmmakers that the productions made by the National Socialists themselves—or at least under their influence—did not result in any neutral images. Indeed, the perspective of the producers taints the images to this day. In this context Judith Keilbach describes the “ideological signatures” of the visuals.7 Nevertheless, these signatures do not completely determine the reception of the images. Rather, Keilbach points out “that even though the recordings are supplemented with ideology, the connoted message of the pictures is neither obvious nor stable.”8 The images are polysemous, and therefore when they are appropriated they are always subjected to transformational processes. Any appropriation of the images under discussion, therefore, has to be wary of repeating the racist, denunciatory perspective of the murderers by, for instance, presenting the images as if they were nothing more than documents. The process of appropriation must deal with the surviving images far more critically—just as the tenets of good scholarship have always demanded historians treat every other source or document.

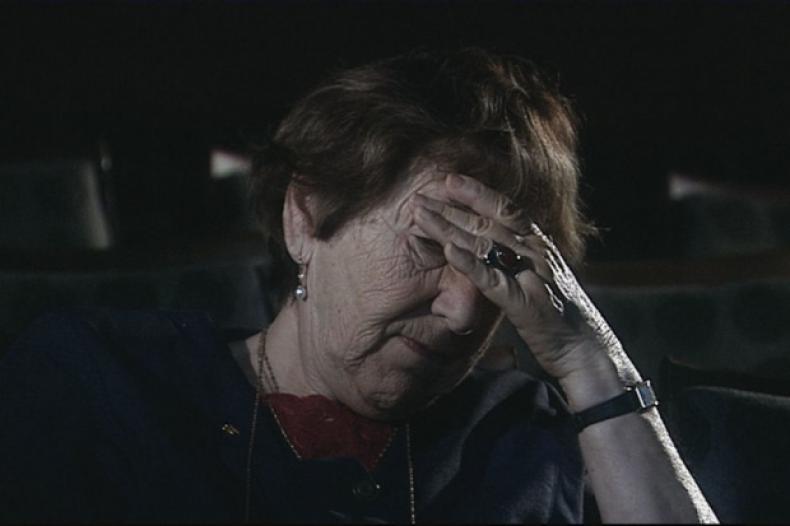

In challenging the dynamic of the images, Hersonski deploys several methods. First, she adds a commentary track that responds not only to historians’ findings, but also cites surviving records by internees, such as the journal of Adam Czerniakow, the chairman of the Jewish council, which details how the inhabitants of the ghetto were forced to collaborate. Furthermore, she records survivors from the Warsaw ghetto watching the old film (fig. 2). She shows their reactions and also integrates their memories of the ghetto and of working on the film. Moreover, she takes a statement, found in the archive, from one of the cameramen who participated in the project in the ghetto, and stages it as if it were an interview. In addition, she employs other means, such as music. All of these procedures are critical interventions; they alter the appropriation of the surviving footage by preventing viewers from naïvely believing the images. It becomes far more obvious how, and to what degree, the National Socialists staged their image of the Jewish internees. Thus, it also becomes easier to see to what extent the archived historical document must be regarded as problematic.

After A FILM UNFINISHED appeared, there was a debate about how much the filmmaker had counteracted the document’s bias.9 The historian Dirk Rupnow accused the film of not presenting any new, historically relevant facts, and at the same time, of merely reproducing the biases of the original material. Although Rupnow admitted that the filmmaker altered the image of the perpetrators by interviewing survivors and adding corresponding scenes in between the archival images, he still criticized it, precisely because of this procedure: “Hersonski has practically put the mourners at the mercy of viewers, who, when looking at them . . . become voyeurs.”10

Above all, however, Rupnow questions under what circumstances the use of historical images created by the perpetrators is justified, from a historian’s point of view. He demands

“that in every single case, one must . . . ask very precisely what the images are showing and reflect upon what is shown very carefully. It must also be made clear why the images are showing it, under what conditions, and with what intention they were filmed—and ultimately, what they do not show.”

According to Rupnow, Hersonski’s film fails to achieve this level of reflection. Despite her critique of the images, Hersonski relies upon them too much: “The film is driven by the perpetrators’ films, which allows them to retain all of their structure and visual language.”

Rainer Rother, to cite another voice in the debate, deems the film to have successfully dealt with the archival material. He regards the filmmaker’s interventions as a deconstruction of the Nazis’ intentions. Hersonski does not simply put the scenes on display; she creates a reading of them. Besides other techniques, Rother refers to the footage of the survivors and their statements. They add the perspective of the victims to the perpetrators’ images, putting them in a context in which they have “never been before.”11 Rother likewise does not see the way that some internees look directly at the camera as a pure reproduction of the Nazi perspective. Rather, they are

"acts in which something uncontrollable occurs, in which the supposed objects of the recordings briefly wrest control from the perpetrators, asserting themselves as subjects by fixing their gaze upon the camera: sometimes furtively, almost secretively, and at other times—seemingly coincidentally—very openly and overtly, self-confident and challenging . . . by directing their gaze toward the camera, they affect the viewer of the film. The victims look at their audience, addressing them and forcing them to interact with them."

According to Rother’s argument, Hersonski’s film does not surrender to the perpetrators’ perspective, but instead presents a reading that makes this perspective legible, on the one hand, while counteracting it on the other.

Rupnow and Rother disagree as to whether the filmmaker succeeds in overriding or counteracting the perspective of the Nazis that is inscribed in the archival film. They do, however, agree that this must happen, even though they have differing opinions as to how this goal can be achieved. Rupnow insists that historians exercise their key responsibilities, demanding that the images be critically contextualized and advance the boundaries of knowledge, since he believes that this is the only thing that justifies (re )presenting these biased images. He advocates more rigorous scholarly work on the material and also points out how such a “re-reading” can have subversive potential, even for methods with less academic weight, such as the interviews with the survivors.

Without wanting to fix Rupnow and Rother too firmly in their individual positions, these different attitudes nonetheless lead to some general questions: When appropriating visual documents of the Shoah, how much weight can be placed on historical research? What sort of role can be played here by non-scientific methods, especially artistic ones? Hersonski positions her film from the start, by asking the questions mentioned above (“What do these images really show? And what don’t they show?”). Because she is aiming for the “truth” behind the reality, her process is subjected to the rules of documentary film. Consequently, she provides a great deal of room for research and for reconstructing individual scenes that took place during the original film shoot. Nevertheless, she also oversteps the boundaries of this process. For instance, underscoring many of the original images with piano and violin music does not really fit into the documentary agenda. These kinds of methods tend to favor emotional, empathetic reception, while forcing the cognitive and critical into the background.

In his silent film RESPITE (GERMANY / SOUTH KOREA 2007) Harun Farocki also makes use of historical film material from the Shoah era and employs a documentary method. And yet, by taking advantage of artistic freedom, the filmmaker moves beyond the documentary in an essayistic direction. Farocki shows footage shot in Westerbork, a transit camp that was the first stop for around 100,000 Dutch Jews on their way to the concentration camps in the east.12 The camp commander commissioned an internee, the photographer Rudolf Breslauer, to make a (never completed) film, beginning in the spring of 1944. Farocki compiled his project from the surviving footage. Apart from several photographs showing the camp before 1942, as well as his own commentary, the filmmaker limits himself to this single source. This alone distinguishes his film from the majority of documentaries about the Nazi camps. He interviews neither witnesses from the period nor experts, nor does he feature shots of the camp today, or any sort of musical soundtrack. Farocki’s intellectual and aesthetic agenda for RESPITE rests mainly on a detailed re-reading of the source material.

Thomas Elsaesser, Sylvie Lindeperg, and others have already examined the film’s main features, knowledgably and astutely contextualizing them in various respects.13 The following emphasizes a few aspects of Farocki’s appropriation of the visuals and pays particular attention to the question of documentary and artistic methods.

If the documentary image in general is often used to establish the truth of past events, this project subverts this essential expectation. The film defies any attempt to derive a single, generalizable meaning. Instead, Farocki’s exploration of the document reveals very different levels of irreducible uncertainties. RESPITE distinguishes itself aesthetically because, in an act of intensive reading, the filmmaker re-examines a single archival holding, making a film about a film. Thus, the focus lies not on the images themselves, but also includes the concepts of reiteration and re-reading.14

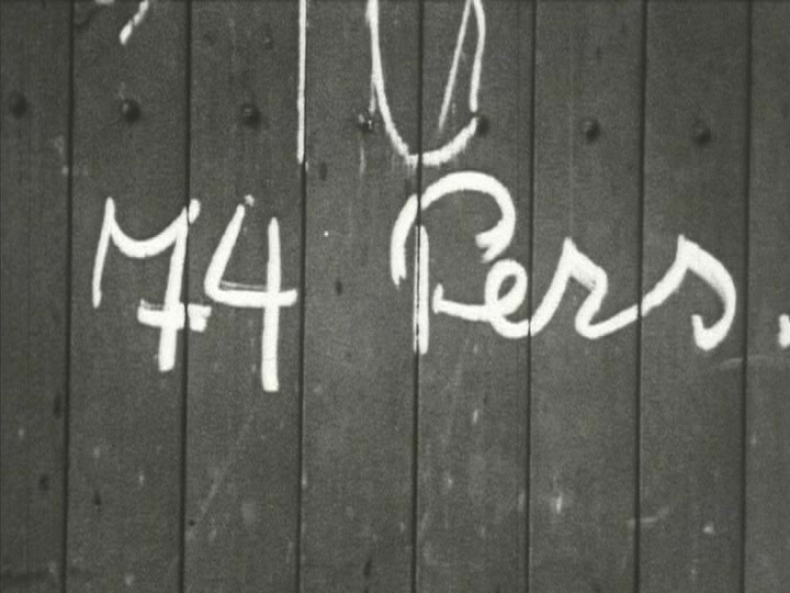

How can these historical images be interpreted? What do they actually document? At least three major tendencies in the relationship between image and commentary can be distinguished in Farocki’s film. The first underscores the aspect of documentation. The commentator performs a meticulous reading of the material, as if he were a detective filtering precise information out of the images—for instance, when he can prove through the images that the number of people being deported in one of the train carriages rose from 74 to 75 (figs. 3 and 4). Here, the visuals serve as historical evidence. A moment of historical reality can be reconstructed.

The film’s second tendency is to interpret the material. The commentary contains statements whose subjectivity is not concealed, but openly displayed. For example, Farocki frames a famous close-up of a Sintisa girl with an intertitle: “The fear of death, or a foreboding of it, can be read in the girl’s face” (fig. 5). Following this subjective assessment is the only passage in the commentary in which the first person singular is heard: “I think that, because of this, the cameraman, Rudolf Breslauer, avoided more close-ups.” This subjective, empathic tendency in the commentary appears alongside the documentary tendencies.

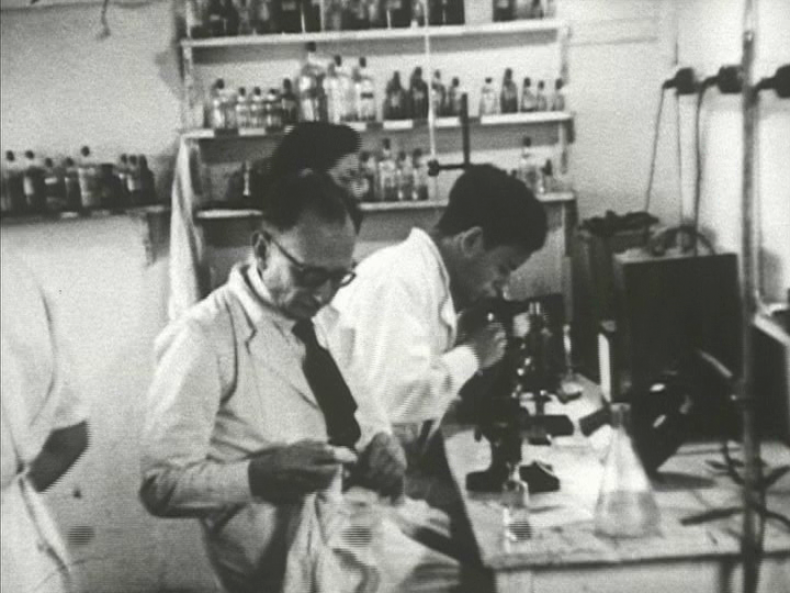

The third tendency can be called a supplementary one. While the first two relate to the material itself, the third makes a connection between Breslauer’s images and others, which the audience does not see, but very likely knows of. Because the commentary mentions these images, the audience becomes conscious of them. Although these images are only alluded to, they supplement the visible pictures. Thus, for instance, after the intertitle “white lab coat in the camp laboratory,” Farocki shows men in the laboratory. This is followed by another title: “One is reminded of the experiments on humans in Auschwitz and Dachau” (fig. 6). The commentary introduces an appropriate description of this technique when it mentions superimposition. “Images we are familiar with from other camps are superimposed on those from Westerbork.” By referring to these other pictures, the commentary deliberately integrates them into Farocki’s film. Strictly speaking, though, this reference should be formulated in a different way, because the thesis is that the other images have been inserted over the ones in RESPITE. The basic idea behind this is that there are always images—mental images—that randomly come to mind and are layered on top of the ones that we happen to be looking at. Or, to put it another way, the pictures we see are always supplemented by other pictures we are not looking at. In this way, the visual discourse and collective memory always modify the images we happen to be perceiving at the moment. The discourse is always supplementing the reading.

While the first tendency pursues the documentary and historical truth, the latter two follow different kinds of logic. One of the structural principles of Farocki’s film is the alignment of tendencies that are contradictory or at least in a state of tension. The evidentiary purpose persists, but it also joins a constellation of imperatives that subvert the documentary (as traditionally conceived). In my opinion, the form of this antagonism—as part of the reading of a document—is the foundation of Farocki’s artistic, essayistic methods. As far as the historical material is concerned, we find ourselves in a double bind: we should not surrender the documentary intention in the reading, but we also should not decisively disambiguate the ineluctable ambiguity of the material.

Farocki’s essayistic exploration of the appropriation of film footage from the Shoah era is exemplified in the complicated, inherently contradictory problems that arise when deciding how to deal with the Nazis’ archived images. Implicitly, his film shows that the visuals do not convey any sort of unequivocal message. Rather, each and every reading co-opts the images for its own purposes. This result also codetermines the work of historians, if they view the images as historical sources. Even though, if one follows Farocki, there is a chance to discover historical data stored in the pictures, a detective-style reading does not go very far. Every other method of “reading film” runs into the inescapable uncertainties of the material, which in fact undermine science’s claim to definitude. Thus, any attempt to integrate the images as historical sources in a positivist manner cannot succeed. Entirely along these lines, Didi-Huberman writes,

“Yet the archive is by no means the pure and simple ‘reflection’ of the event, nor its pure and simple ‘evidence.’ For it must always be developed by repeated cross-checkings and by montage with other archives.”15

Sophisticated filmmakers such as Farocki already know that these critical positions define their work. Meanwhile, it remains to be seen to what extent the various reading practices employed here can be relevant to historical scholarship.

- 1Robert A. Rosenstone, “History in Images/History in Words: Reflections on the Possibility of Really Putting History onto Film,” American Historical Review 93.5 (1988): 1180.

- 2Günter Riederer, “Den Bilderschatz heben: Vom schwierigen Verhältnis zwischen Geschichtswissenschaft und Film,” Tel Aviver Jahrbuch für deutsche Geschichte 31 (2003): 28.

- 3For more on this, see Sven Kramer, “Authentizität und Authentisierungsstrategien in filmischen Darstellungen der Todeslager,” in: Kramer, Auschwitz im Widerstreit (Wiesbaden 1999), 29–45.

- 4See Ulrike Weckel, Beschämende Bilder: Deutsche Reaktionen auf alliierte Dokumentarfilme über befreite Konzentrationslager (Stuttgart 2012), 14.

- 5Ibid., 20.

- 6Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All, trans. Shane B. Lillis (Chicago 2008). Originally published in French as Images malgré tout (Paris 2003).

- 7Judith Keilbach, Geschichtsbilder und Zeitzeugen: Zur Darstellung des Nationalsozialismus im bundesdeutschen Fernsehen (Münster 2010), 44.

- 8Ibid., 48.

- 9The Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (Federal Agency for Civic Education) documents the debate in an online dossier; see BPB, “Geheimsache Ghettofilm: Dossier,” accessed April 23, 2014, http://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/geheimsache-ghettofilm.

- 10Dirk Rupnow, “Die Spuren nationalsozialistischer Gedächtnispolitik und unser Umgang mit den Bildern der Täter: Ein Beitrag zu Yael Hersonskis A FILM UNFINISHED/GEHEIMSACHE GHETTOFILM,” Zeitgeschichte-online, October 2010, accessed April 23, 2014, http://www.zeitgeschichte-online.de/film/die-spuren-nationalsozialistis….

- 11Rainer Rother, “Nationalsozialistische Filmpropaganda – filmisch dekonstruiert: Ein Kommentar zu Yael Hersonskis Film GEHEIMSACHE GHETTOFILM” [2013], Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, accessed April 23, 2014, http://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/geheimsache-ghettofilm….

- 12“Seventy-eight percent of Dutch Jews, that is, nearly 101,000 people, were deported from here to the concentration camps of Auschwitz-Birkenau and Sobibór; of them, only around 5,000 survived.” (Anna Hájková, “Das polizeiliche Durchgangslager Westerbork,” in Terror im Westen: Nationalsozialistische Lager in den Niederlanden, Belgien und Luxemburg 1940–1945, ed. Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel [Berlin 2004], 217).

- 13See Thomas Elsaesser’s essay in this volume, “Returning to the Past its Own Future: Harun Farocki's RESPITE”. Also: Sylvie Lindeperg, “Suspended Lives, Revenant Images: On Harun Farocki’s Film RESPITE,” in Harun Farocki: Against What? Against Whom?, ed. Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun (London 2009), 28–34. See also: Nora Alter, “Dead Silence,” in Ehmann / Eshun, eds., Harun Farocki, 171–178; Antje Ehmann, “Der essayistische Film – eine Abgrenzung wovon? Zur Bestimmung von Harun Farockis Film AUFSCHUB,” in Der Essayfilm: Ästhetik und Aktualität, ed. Sven Kramer and Thomas Tode (Konstanz 2011), 89–100.

- 14For more on this, see: Sven Kramer, Transformationen der Gewalt im Film (Berlin 2014), 142–166.

- 15Didi-Huberman, Images, 147.

Alter, Nora. “Dead Silence.” In: Harun Farocki: Against What? Against Whom?, edited by Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun. London 2009.

Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung. “Geheimsache Ghettofilm: Dossier,” accessed April 23, 2014, http://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/geheimsache-ghettofilm.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Images in Spite of All, translated by Shane B. Lillis. Chicago 2008. Originally published in French as Images malgré tout. Paris 2003.

Ehmann, Antje. “Der essayistische Film – eine Abgrenzung wovon? Zur Bestimmung von Harun Farockis Film AUFSCHUB.” In Der Essayfilm: Ästhetik und Aktualität, edited by Sven Kramer and Thomas Tode. Konstanz 2011.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Returning to the Past its Own Future: Harun Farocki's RESPITE." In: Research in Film and History 1 (2018).

Hájková, Anna. “Das polizeiliche Durchgangslager Westerbork.” In Terror im Westen: Nationalsozialistische Lager in den Niederlanden, Belgien und Luxemburg 1940–1945, edited by Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel. Berlin 2004.

Keilbach, Judith. Geschichtsbilder und Zeitzeugen: Zur Darstellung des Nationalsozialismus im bundesdeutschen Fernsehen. Münster 2010.

Kramer, Sven. “Authentizität und Authentisierungsstrategien in filmischen Darstellungen der Todeslager.” In: Auschwitz im Widerstreit. Wiesbaden 1999.

Kramer, Sven. Transformationen der Gewalt im Film. Berlin 2014.

Lindeperg, Sylvie. “Suspended Lives, Revenant Images: On Harun Farocki’s Film RESPITE.” In Harun Farocki: Against What? Against Whom?, edited by Antje Ehmann and Kodwo Eshun. London 2009.

Riederer, Günter. “Den Bilderschatz heben: Vom schwierigen Verhältnis zwischen Geschichtswissenschaft und Film.” In: Tel Aviver Jahrbuch für deutsche Geschichte 31 (2003).

Rosenstone, Robert A. “History in Images/History in Words: Reflections on the Possibility of Really Putting History onto Film.” In: American Historical Review 93.5 (1988).

Rother, Rainer. “Nationalsozialistische Filmpropaganda – filmisch dekonstruiert: Ein Kommentar zu Yael Hersonskis Film GEHEIMSACHE GHETTOFILM” [2013], Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, accessed April 23, 2014, http://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/geheimsache-ghettofilm….

Rupnow, Dirk. “Die Spuren nationalsozialistischer Gedächtnispolitik und unser Umgang mit den Bildern der Täter: Ein Beitrag zu Yael Hersonskis A FILM UNFINISHED/GEHEIMSACHE GHETTOFILM.” In: Zeitgeschichte-online October 2010, accessed April 23, 2014, http://www.zeitgeschichte-online.de/film/die-spuren-nationalsozialistis….

Weckel, Ulrike. Beschämende Bilder: Deutsche Reaktionen auf alliierte Dokumentarfilme über befreite Konzentrationslager. Stuttgart 2012.