Recording and Modeling

On the Desire for Presence in Historical Documentaries

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Öhner, Vrääth: Recording and Modeling: On the Desire for Presence in Historical Documentaries. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–7. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14794.

While it might already seem unusual to turn attention first and foremost to the soundtrack in a study of documentary film,1 it probably seems even more unusual if the field of study is limited to the use of sound in historical (television) documentaries. But the situation threatens to become entirely absurd if we reduce the field even more and focus on the least prominent aspect of the soundtrack, noise. For although the soundtrack seems to play a more important role in television than it does in the cinema (according to Rick Altman, it italicizes items in the running program and calls spectators who have briefly left the room back to the screen)2 we should already know from experience what is confirmed by a cursory empirical examination: in historical television, at least in its Austrian, public television version, across all breaks, transitions, and caesuras (from the rather paternalist paleotelevision to more intimate neo-television,3 from “illustrated radio” to its own independent forms of televisuality),4 the soundtrack is dominated by language and the voice. While music fulfills functions that evoke emotion and meaning,5 noises are usually not assigned any other task but to “confirm what is already visually represented and to offer additional security.”6

This finding immediately raises two questions: first of all, why is this the case, and secondly, what does it mean for the audio-visually communicated experience of the past and/or history? Clearly, there is a whole series of possible answers to these questions located on quite different levels of explanation. And although I do not intend to exhaust the series of possible answers by any means, I would like to begin with a few fundamental considerations on noise, perhaps already all too familiar.

First of all, noises confront human perception and, by extension, technological recording with a problem that the passionate radio listener Martin Heidegger already described in Being and Time in 1927: “Hearkening, too, has the mode of being of a hearing that understands. ‘Initially’ we never hear noises and complexes of sound, but the creaking wagon, the motorcycle. We hear the column on the march, the north wind, the woodpecker tapping, the crackling fire. It requires a very artificial and complicated attitude in order to ‘hear’ a ‘pure noise.’ The fact that we initially hear motorcycles and cars, is, however, the phenomenal proof that Dasein, as Being-in-the-world, always already maintains itself together with innerworldy things at hand and initially not at all with ‘sensations’ whose chaos would first have to be formed to provide the springboard from which the subject jumps off to land in a ‘world.’ Essentially understanding, Dasein is initially together with what is understood.”7

Now we could deduce from Heidegger’s comment that media arrangements like the cinema, radio, or television, which, as a reality of second order are based on their distance to “innerwordly things,” unburden their audience from the life-worldy necessity of comprehensive listening and, by generating a “a very artificial and complicated attitude,” reveal an aesthetic, cultural, or socio-political task. Indeed, the experiments with documentary film sound undertaken beginning in the late 1920s in the Soviet Union, the UK, and in Germany point towards the direction of de-familiarization and aconceptual sensation.8 And yet such experimental techniques did not become the audio-visual standard in documentaries, and instead were supplanted for a very long time by techniques of confirmation offering security for the visually depicted: until the start of the 1960s, when the new possibilities of synchronic recording ushered in the new. This might have be due in part to the nature of comprehensive listening, alongside technological, political, and institutional reasons. For just as noises evoke the image of their source in lifeworld contexts, in audiovisual conditions (that is, under the condition of the fundamental dependence of sound on the image) they have the tendency to take hold of objects, individuals, and events, thus limiting space for experimentation.9

Furthermore, these Heideggerian considerations are confirmed by the experience of sound engineers and mixers, albeit in mirror reversal. Often, recorded noises correspond neither to what was recorded on-site nor does the synchronically recorded original tone correspond to the image. Michel Chion called the notion of a “natural harmony” between sounds and images a naturalistic illusion that overlooks the fact that the transference of reality to two audio-visual dimensions represents “a radical sensory reduction.”10 The miracle is not that the sounds and image do not fit together, but that they usually do harmonize when experienced in the location of the cinema. Of course, they do so only on the basis of historically established conventions that represent an arrangement between recorded sound or a realistic or even true-to-life appearance. As Volko Kamensky and Julian Rohrhuber explain, “the notion of sound fidelity for the rendering and the original that is supposedly ‘stored’ in a recording . . . corresponds to a world of experience ‘flooded with conventions,’ that has long become used to the codes of theater, television and cinema, so that what ‘sounds true,’ takes the place of the ever regressing true essence of the sound.”11

For the documentary film’s claim to a realistic depiction of reality, a characteristic field of tension emerges between “representation that seems realistic, but which is perhaps corrected, and an actual, but unrealistic seeming one,”12 leading in the history of documentary film to the formation of quite long-lived conventionalized techniques of harmonizing sounds and images: in the genre of the historical documentary, the dominant mode combines non-diegetic commentary, sometimes supported by non-diegetic music, with the silent image, reducing sound to speaking and speech to a rhetoric that affirms the diegetic world. In this context, noises do not even play the subordinate role assigned to them in feature film of confirming and affirming what is visually represented, even before the “quiet revolution” in the soundtrack during the mid-1970s.13 (Since then, American feature films have been dominated by a “hyperrealism” that is largely divorced from acoustic experience in the lifeworld.)

The near absence of noises in historical documentary can be explained in purely pragmatic terms by a prior lack regarding the archival material: before 1960, the visual material of the newsreels, upon which historical television is primarily based, were usually filmed without sound. The only exception here were speeches and addresses by people of public interest, often reproduced in historical documentaries (along with the constantly present background noises or disturbances). But of course, the indication of a lack of original sound is not sufficient to explain the signifying practice of history television. First of all, history broadcasting often takes recourse to the device of post-recording sounds (most striking in sources from the era of silent film). Secondly, respect for the integrity of archival material in historical television does not play a central role in the genre. In light of the near absence of noise, it is striking that historical television thus refuses a realistic-seeming presentation of the past. Is this due to the power of a convention that assumes that the credibility of rhetorical strategies of commentary and montage are sufficiently confirmed by the photographic realism of the image? Or, is the refusal of a realistic appearance perhaps not a necessary requirement for the functioning of the historical narrative with all the rhetorical strategies used?

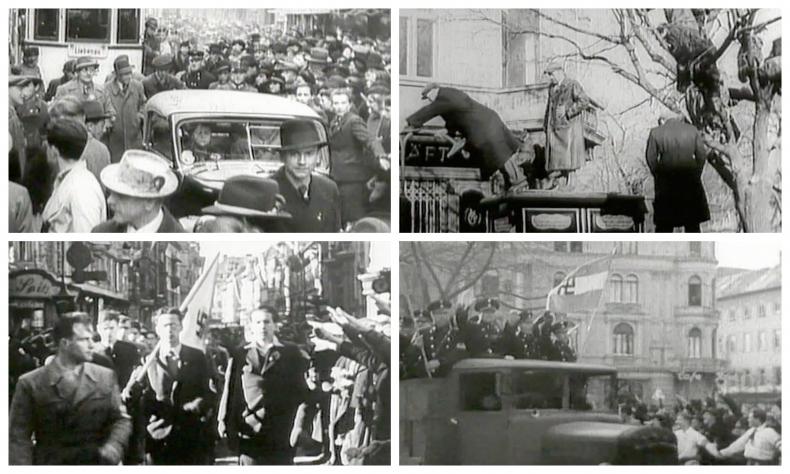

Before I begin to sketch an answer to these questions, I would like to show what my argument is based upon using the example of a comparison between archival material and audio-visual historiography, two brief sequences that deal with a rather problematic moment in Austrian national memory, the so-called “pseudo-revolutionary seizure of power from below” on March 11 and 12, 193814 that anticipated the arrival of German Wehrmacht troops. The first sequence is from Episode 7 of the most-extensive production of Austrian television dealing with the history of the First Republic, the 12-part series ÖSTERREICH I / AUSTRIA I (AUSTRIA 1987). The episode is entitled DIE HEIMSUCHUNG ÖSTERREICHS (Austria’s Visitation) and was initially broadcast in 1988 (on the fiftieth anniversary of the so-called Anschluss), and since then has been rebroadcast several times, in a revised form on the 75th anniversary of the event, which was then released on DVD.15 The second sequence comes from the Ostmark Wochenschau No. 12/1938 (the successor to the Austrian weekly newsreel Österreich in Bild und Ton) from the holdings of the Österreichisches Filmmuseum. Copies of this newsreel were shown in Austrian cinemas as of March 18, 1938.

The sequence from ÖSTERREICH I begins with shots of a large crowd moving through the streets of the Styrian capital of Graz, initially without a recognizable goal, but at least towards the camera. The non-diegetic commentary situates the events:

“Graz. March 12, 1938. The scene here recurred across almost all of Austria. The arrival of the German troops is expected. But they have not yet arrived.”

In the image, we see people climbing up trees to get a better view. In the next shot, the object of their scopophilia becomes visible for the first time, marching groups whose political affiliation is signaled by scattered flags and armbands emblazoned with swastikas. The commentary explains the situation:

“Instead, the local Nazis were on the march. Armed men from the SA and all the other previously illegal [Nazi] formations emerged. Still without uniforms, but well organized.”

This establishes the basic constellation that is varied over the further course of the sequence. The Austrian Nazis being celebrated by the Austrian population, standing for the “seizure of power from below,” which, hidden from the gaze of the newsreel cameras, took place at the same time in the country’s offices, city halls, and state governments.

While ÖSTERREICH I interprets the events leading up to the Anschluss largely along the lines of academic historiography of the late 1980s as a kind of conspiracy of only provisionally legalized, but well organized Nazis (led by interim chancellor Seyß-Inquart, in power from March 11–13, 1938), and the celebration of the population in expectation of the arrival of German troops, the Ostmark Wochenschau No. 12/1938 speaks from a propagandistic perspective, presenting the then contemporary perception albeit one-sidedly, but therefore all the more clearly, endlessly referring to the country’s “liberation.” To shots similar to that of the crowd on the streets of Graz in ÖSTERREICH I, the narrator announces:

“The resignation of the Austrian government causes endless celebration. In all cities, in the smallest towns the people are on their feet. Austria is free! Austria is National Socialist! Austria is once again the Ostmark of the Reich!”16

Acoustically, the commonalities are as striking as are the differences. Let us turn first to the commonalities. Quite clearly, both sequences were rerecorded in such a way that only partially “reproduced” the acoustic dimension of the visible events. In both sequences, the number of sound sources can be counted on one hand, whereby for propagandistic clarity Ostmark Wochenschau limits its acoustic spectrum even more so than ÖSTERREICH I: it makes do with just four sources of sound, the cries of a celebratory crowd, later clearly calling out “Sieg Heil,” and the roar of airplane motors and trucks. It is notable that ÖSTERREICH I also includes the combination of airplane noise and the crowd’s jubilation. For both sequences, the sounds are not exactly, but nearly synchronous to their source as shown in the image.

As far as the differences go, the most striking is not of an acoustic nature, but visual: the visual material overlaps only in a few aspects. The reason for this is that the material used by Portisch/Riff largely comes from Ostmark Wochenschau 11b/1938,17 of which Österreichisches Filmmuseum only has a silent version. At least the two sequences refer to the same event. Acoustically speaking, they differ primarily in that ÖSTERREICH I uses a consistent “atmosphere,” while its very absence is striking at the start of the weekly newsreel. Secondly, in ÖSTERREICH I the sounds are moved much more to the background in relation to the commentary and the relatively balanced volume is kept at a low level, while the background noise in Ostmark Wochenschau already begins at a significantly higher volume and later non-diegetic fanfare sounds and the commentator voice fusing to form a growing chorus of jubilation. Thirdly, the two sequences differ in that the music in ÖSTERREICH I is diegetically integrated.

Previously, I asked whether historical television’s refusal to provide a realistic seeming representation in the acoustic has to do with the power of a convention that the credibility of rhetorical strategies is sufficiently insured by the photographic realism of the image, or whether this refusal is not rather a necessary prerequisite for the functioning of historical narrative itself. The comparison of the two sequences seems to suggest the latter. If we consider the transformation of the “real” of the newsreel into a historical narrative that consists in rerecording similar sources of sound as in the clear distantiation of the commentary voices from the noise, then we could speak of what Daniel Deshay calls the “re-narration of the event” that replaces the “sound recording of the same event.” This contains the power “that the noise allows us to experience due to the ‘reality effect’ typical of it . . . If [this power] is transformed into a narrative, the reality of the noise becomes a second-degree reality.”18 (Since the noises were already re-recorded in the newsreels, the “reality effect” does not refer to the true rendering of historical reality, but the reality of the document preserved in the archive.)

The transformation of the reality of the noise into a second-degree reality held at a distance, created using the narrative, recalls not accidentally the gesture of the historian in Jules Michelet’s History of the French Revolution, who only shows the documents from the archive to then withdraw them once again. Historical television shares with this gesture the same poetic structure of historical knowledge. Jacques Rancière described this structure as follows: “The discourse of the scholar becomes a narrative . . . so that the its autonomous unfolding . . . may hold, in the same register, the evocation of the past event . . . and the explication of its meaning, so that it may put them in the same present, that of the meaning present at the event.”19 The use of the audio-visual archive in historical television testifies to a similar desire for presence that is clearly inscribed in the long-lived link between dominant commentary and the reduced impact of sound.20 Seen in this light, historical television’s refusal to engage in a realistic-seeming representation of the past in the acoustic is thus a necessary prerequisite for the functioning of historical narrative.

- 1Unusual, because the first relevant publication on documentary sound in the German-speaking world was published in 2013, see Volko Kamensky and Julian Rohrhuber, eds., Ton: Texte zur Akustik im Dokumentarfilm (Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2013).

- 2See Rick Altman, “Television/Sound,” Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture, ed. Tania Modleski (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1986); Ralf Adelmann et al., eds., Grundlagentexte zur Fernsehwissenschaft (Constance: UTB, 2001), 388–412.

- 3See Francesco Casetti and Roger Odin, “Vom Paläo- zum Neo-Fernsehen. Ein semio-pragmatischer Ansatz,” in Adelmann, Grundlagentexte zur Fernsehwissenschaft, 311–334.

- 4See John T. Caldwell, Televisuality: Style Crisis, and Authority in American Television (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995).

- 5See Judith Keilbach, “Präsentation: Musik und Geräusche,” Geschichtsbilder und Zeitzeugen: Zur Darstellung des Nationalsozialismus im Bundesdeutschen Fernsehen (Münster: LIT, 2008), 106–108.

- 6Volko Kamensky and Julian Rohrhuber, “Phaedrus’ Ferkel: Zum Problem des Geräuschs im dokumentarischen Filmton,” in Kamensky and Rohrhuber, Ton, 333.

- 7Martin Heidegger, Being and Time, trans. Joan Stambaugh (Albany: SUNY Press, 2010), 158.

- 8See Vrääth Öhner, “Suggestive Klänge, störende Wirklichkeiten: Die britische Schule und der Realismus des Geräuschs,” in Kamensky and Rohrhuber, eds., Ton, 98–109.

- 9“The dissociation of sound from its source always awakens powers that seek to recombine or reterritorialize the dissociated elements by virtually any means available.” Volko Kamensky and Julian Rohrhuber, “Einleitung. Gibt es dokumentarischen Filmton?”, Kamensky and Rohrhuber, Ton, 24.

- 10Michel Chion, “The Real and the Rendered,” Audio-Vision, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York: Columbia University Press, 1994), 95–96.

- 11Kamensky and Rohrhuber, Ton, 15.

- 12Ibid., 33.

- 13See Michel Chion, “Quiet Revolution . . . and Rigid Stagnation,” trans. Ben Brewster, October 58 (Autumn, 1991).

- 14Gerhard Botz, Wien vom “Anschluss” zum Krieg (Vienna: Jugend und Volk, 1978), 107.

- 15See Hugo Portisch, Sepp Riff: ÖSTERREICH I. ORF Edition 2013 (12 episodes, each ca. 100 minutes).

- 16In the collective memory of the Second Republic, the call “Austria is free” is linked primarily to an event that reverses the loss of state sovereignty linked to the Anschluss: the signing of the State Treaty on May 15, 1955. The Austrian chancellor Leopolod Figl used these words during his speech after the signing. In historical television documentaries, the call is often accompanied by the image showing Figl on the balcony of Belvedere Castle at the moment when he presents the State Treaty to the celebratory crowd.

- 17Inserted later, No. 9, STEIERMARK: NACH DER MACHTERGREIFUNG DURCH DIE NSDAP.

- 18Daniel Deshays, “Film hören,” Kamensky and Rohrhuber, Ton, 312.

- 19Jacques Rancière, The Names of History: On the Poetics of Knowledge, trans Hassan Melehy (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994), 48.

- 20This argument seems to repeat the controversial assertion of the dominance of the voice-over in documentary film. The standard objection to this one-sided dominance is what Michel Chion called the “surplus value” of sound, according to which sound provides new meanings to the image and the image provides new meanings for the sound. However, in the view of Carl R. Plantinga “the rhetorical use of the shot in nonfiction films often overrides considerations of the shot as pure visual information” (“Indices and the Uses of Images,” Rhetoric and Representation in Non-fiction Film (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997), 86.)

Adelmann, Ralf et al. (eds.). Grundlagentexte zur Fernsehwissenschaft. Constance: UTB, 2001.

Altman, Rick. “Television/Sound,” in Studies in Entertainment: Critical Approaches to Mass Culture, ed. Tania Modleski. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1986.

Botz, Gerhard. Wien vom “Anschluss” zum Krieg. Vienna: Jugend und Volk, 1978.

Caldwell, John T. Televisuality: Style Crisis, and Authority in American Television. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995.

Casetti, Francesco and Roger Odin, “Vom Paläo- zum Neo-Fernsehen. Ein semio-pragmatischer Ansatz,” in Grundlagentexte zur Fernsehwissenschaft. Constance: UTB, 2001.

Chion, Michel. “The Real and the Rendered,” in Audio-Vision, trans. Claudia Gorbman. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

Chion, Michel. “Quiet Revolution . . . and Rigid Stagnation,” trans. Ben Brewster, October 58. Autumn, 1991.

Deshays, Daniel “Film hören,” in Ton: Texte zur Akustik im Dokumentarfilm. Berlin: Vorkwerk 8, 2013.

Heidegger, Martin. Being and Time, trans. Joan Stambaugh. Albany: SUNY Press, 2010.

Kamensky, Volko and Julian Rohrhuber. “Phaedrus’ Ferkel: Zum Problem des Geräuschs im dokumentarischen Filmton,” in Ton: Texte zur Akustik im Dokumentarfilm. Berlin: Vorkwerk 8, 2013.

Kamensky, Volko and Julian Rohrhuber (eds.). Ton: Texte zur Akustik im Dokumentarfilm. Berlin: Vorkwerk 8, 2013.

Keilbach, Judith. “Präsentation: Musik und Geräusche,” in Geschichtsbilder und Zeitzeugen: Zur Darstellung des Nationalsozialismus im Bundesdeutschen Fernsehen. Münster: LIT, 2008.

Öhner, Vrääth. “Suggestive Klänge, störende Wirklichkeiten: Die britische Schule und der Realismus des Geräuschs,” in Ton: Texte zur Akustik im Dokumentarfilm. Berlin: Vorkwerk 8, 2013.

Plantinga, Carl R. “Indices and the Uses of Images,” in Rhetoric and Representation in Non-fiction Film. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Rancière, Jacques. The Names of History: On the Poetics of Knowledge, trans Hassan Melehy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1994.