Archiveology

Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Russell, Catherine: Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–22. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14788.

Method of this project: literary montage. I needn’t say anything. Merely show. I shall purloin no valuables, appropriate no ingenious formulations. But the rags, the refuse - these I will not inventory but allow, in the only way possible, to come into their own: by making use of them. Walter Benjamin2

The term ‚archiveology‘ is a neologism that can help us understand a mode of film language in which authorship is transformed into practices of research, appropriation, borrowing and recycling. My book, with the same name as this paper, is an inquiry into the stakes of this new language, what can it say, and how can we read it critically and productively.3 Archiveology is a critical method derived from Walter Benjamin’s cultural theory that I believe provides valuable tools for grasping the implications of the practice of remixing and reconfiguring the image bank of film and media histories. As the status of the archive has been transformed in digital culture from the closed institution to open access, so too have its aesthetics and politics.

In my book Experimental Ethnography, I wrote about found footage filmmaking in terms of apocalypse culture.4 In 1999 it seemed as if this mode of film practice was preoccupied with ‚the end of history‘ and the promise that Benjamin held out for cinema had failed to be realized. Seventeen years later, as archival film practices have become more prevalent in mainstream culture, and in experimental media, I am more optimistic about the cultural role of audio-visual appropriation. One key change has been a shift in theory and practice to the recognition of the research function implicit in archival film practices. ‚Found footage‘ links the mode to surrealist practices of accident and recontextualization, but negates the extensive searching that sustains the practice. Recognition of the search function in archiveology highlights the role of the moving-image archive, and its transformation in digital culture. The filmmaker is not unlike the archaeologist who ‚finds‘ things and is able to recognize their cultural value. Whether their search is conducted by algorithm, or through files or film cans, every find for the filmmaker is a lucky find when it can be recombined with other images to create a new experience and even knew knowledge.

The term ‚archiveology‘ was originally coined by Joel Katz in 19915, partly in response to the release of FROM THE POLE TO THE EQUATOR (I/D 1987) by Angela Ricci-Lucchi and Yervant Gianikian, one of the first experimental films to explicitly work with material from a film archive. Katz used the term to refer to the ways that filmmakers were making the archive useful, and engaging with it on its own terms. By the early 1990s Rick Prelinger’s archive of ephemeral film was already pointing to the way that audio-visual kitsch provided a rich resource for rethinking and remaking American cultural history. Both the Italian team and Prelinger have continued to expand their archival film practices, along with a plenitude of other film and video artists, exploring the potential of audio-visual fragments to construct new ways of accessing and framing histories that might otherwise have been forgotten and neglected—and to make these histories relevant to contemporary concerns.

Etymologically, archiveology might mean the study of archives, but the Greek suffix ‚-ology‘ actually refers to someone who speaks in a certain manner. When applied to film practice, it refers to the use of the image archive as a language. Moreover, the connotations of archaeology point to the cultural history that is inevitably inscribed in resurrected film fragments. Film and media artists are transforming cinema into an archival language, helping us to rethink film history as a source of rich insight into historical experience. The technologies of film stocks, video grain and other signs of media history are often inscribed within the imagery of archival film practices, inscribing a materiality into this practice; just as often, though, digital effects can alter the image and obfuscate both the original ‚support‘ material as well as the referential indexicality. As Thomas Elsaesser notes, when post-production becomes „the default value“ it „changes cinema’s inner logic and ontology.“ He compares the new mode of image-making to „the extraction of natural resources,“ among other things. His caveat that „the ethics of appropriation will take on a whole other dimension“6 is a theme for which Walter Benjamin’s cultural politics provides valuable guidance - and one of the many reasons why I have turned to his ideosyncratic cultural theory for a better grasp of archiveology.

The term archiveology has been used to refer to the work of Derrida and Foucault, who have of course contributed immensely to our understanding of the archive as a social practice.7 Derrida’s „archive fever” is manifest in the way that archival film practices work against the archive itself by fragmenting, destroying and ruining the narrativity of the source material. The death drive is always at work in films that are built on the ruins of historical pleasures and experiences, subjecting them to the repetitions of remediation. The term archiveology surfaces occasionally in discussions of Foucault, for whom the archive functions as an archaeology of knowledge and is the basis of all discursive practice.8 His sense of the archive as constituting a „border of time“ is key to the effects of media archiveology and its discontinuous effects of historicity.

In the early 20th century, the architecture, social role, and politics of the archive have been radically changed from their origins in institutional ‚domiciliation‘. Film and media archivists are tasked with making film history accessible and transmissible; in ‚restoring‘ and preserving film, they are frequently transforming film into new media by using digital techniques, thereby challenging norms of authenticity, media specificity and origins that have traditionally been attached to the archive.9 The gate-keeping function of the traditional ‚archon‘ no doubt persists, and has taken on new personas such as that of the copyright holder and the pay-wall; but many gates are easily breached with the aid of digital tools. With the new challenges, platforms, and activities of film and media archives, the practice of archiving is changing rapidly, and has in many cases blended into creative art practices. If we are all archiving all the time in an effort to manage our own computer files, then the public/private distinction between archive and collection may also be arguably dissolving. The digital turn is, however, only one more phase of a process that Sven Spieker claims to be endemic to modernity. From the perspective of the avant-garde, the archive is a transformational process, with the power of turning garbage into culture. However, the flip side of this claim is also true - that „when an archive has to collect everything, because every object may become useful in the future, it will soon succumb to entropy and chaos.“10

Spieker’s analysis of the multiple art practices that have pitched themselves against the institutions and codes of bureaucracy is echoed in Paula Amad’s account of the counter-archive, which makes similar arguments in connection to the film archive as it emerged in the early 20th century. The dream of complete knowledge in the totalizing capacity of the photographic record, and the incorporation of ‚the everyday‘ into the historical record (the trash) constituted a real challenge to historiographic method. With the cinema, archives are no longer about origins. Documents are representations that have their own networks of secrets, which will always be in excess of their ostensible meaning as evidence. As Foucault has taught us, the archive should not be taken as knowledge itself, but should be recognized as a key site of the power and social relations that provide the conditions for knowledge.

The archive as a construction site was at the basis of Benjamin’s understanding of it. In keeping with Bergson and Kracauer, the archive for Benjamin is always about memory and the condition of forgetting. The camera fundamentally altered the function of human memory, precisely by transforming it into a kind of archive. Benjamin himself never uses a neologism such as archiveology but he certainly evokes it in a fragment of writing from 1932 called Excavation and Memory.11 In this fragment, Benjamin suggests that memory might itself be a medium. He compares memory to an archaeological process in which the „richest prize“ is the correspondence between present and past. „A good archaeological report,“ he argues, „gives an account of the strata which first had to be broken through.“ He also says that the „matter itself,“ which „yields its long-lost secrets,“ produces images that „severed from all earlier associations, reside as treasures in the sober rooms of our later insights.“ Memory, for Benjamin, is only a „medium“ insofar as it is experienced; and it is precisely this reawakening of experience that the moving image is able to evoke.

The Living Archive

Benjamin’s theory of the allegorical image has been widely understood in terms of a modern Baroque, but it is evident from contemporary archival film practices that the language of appropriated images is not a dead language. While the archive certainly lends itself frequently to a melancholic sensibility, works such as FILM IST (Gustav Deutsche, AUT 1998-2002) and THE MAELSTROM (Peter Forgács, NL 1997) awaken us to new meanings and new histories that can be produced from the ruins of the past. Jan Verwoert argues that since the 1990s there has been a momentum in critical discourse „away from the arbitrary and constructed character of the linguistic sign towards a desire to understand the performativity of language.“12 Verwoert argues that the appropriated object or language can and will speak back, resisting the desire of the collector seeking to repossess it. The unresolved histories and modernities lingering in the image bank are, in this sense, awaiting practitioners to bring them to life and allow them to speak.

Underlying much of the rethinking of archive-based arts after postmodernism is a recognition that images are constitutive of historical experience, and not merely a representation of it. For example, Emma Cocker argues that archival film practices can produce „empathetic - even resistant or dissenting - forms of memory, a progressive politics.“13 She describes „ethical possession“ as a mode of borrowing from archives for discourses of recuperation and resistance. Notwithstanding the vaguaries of copyright law, appropriation needs to be understood as a form of borrowing that can open up new practices of writing history, and conceptualizing the future.14 Cocker describes a „paradigm shift“ in the use of archival materials since 1990.

For Benjamin, quotation and montage are keys to the dialectics of cultural history. The link between excavation and construction is crucial, if the traumas of the past (the history of barbarism) can be the foundation of historical thought. Benjamin describes his method in The Arcades Project as one of „carrying the principle of montage into history… to grasp the construction of history as such.“15 Precisely because images are mediated, „second nature“, they offer unique insights into the past. Okwui Enwezor introduces the 2009 exhibition Archive Fever as an exhibit that „opens up new pictorial and historiographic experiences against the exactitude of the photographic trace.“16 In other words, the historical value and implications of appropriation art are not grounded in the indexical authority of the document, but in the life of the document-as-image, and the image-as-document.

Walter Benjamin’s name is frequently cited by theorists of media archaeology wishing to construct a retroactive lineage for a field that has only recently emerged. Jussi Parikka and Erkki Huhtamo position him as a key forerunner, alongside Foucault, describing The Arcades Project as an exemplary form of media archaeology, insofar as it is composed of discursive layers of culture, reconstructing Paris from its traces in a wide variety of media.17 Benjamin certainly has much to offer this new field, given his recognition of the sensorial effects of new media technologies, and the allegorical status of the ruins of material culture. The filmmakers who I am interested in frequently work with the traces of celluloid degradation, pixilation and other signs of the media from which imagery is borrowed, speaking back to the technologies of production at the same time as they speak back to the image archive.

Jussi Parikka notes that „an archivology [sic] of media does not simply analyze the cultural archive but actively opens new kinds of archival action.“18 For Parikka, following Wolfgang Ernst, this action seems to be specifically tied to data banks, algorithms and other technical processes. The archive is no longer passive, but is made to generate „new insights“ and „unexpected statements and perspectives.“19 Benjamin’s conception of the image, in conjunction with his insights into media, historiography, and the avant-garde provide a means of thinking of archiveology as a creative practice produced by humans, not machines. Archiveology in this sense involves the interface of human and machine, or as Miriam Hansen has argued in her parsing of Benjamin, a gamble with technology, with the stakes that of the survival of the human senses within the domain of technology.20 Many filmmakers refer to their work as archaeological, and their films are evidence that media archaeology needs to account for images and sounds, viewers and makers.

At the same time as filmmakers are recycling sounds and images in new ways, museums and film archives are also undergoing significant change in the digital era. In 2012 the EYE Museum in Amsterdam launched a series of innovative strategies for integrating film practice and production with film restoration and heritage.21 Filmmakers such as Gustav Deutsche and Peter Delpeut have been invited to use film fragments from the Netherlands Film Archive for new work; and through online digital platforms, the general public has also been encouraged and enabled to rework material from the film archive. Archivists are reaching out to filmmakers to make the film archive accessible, and to bring it to life. Meanwhile, media artists such as Christian Marclay in THE CLOCK (UK 2010) and VIDEO QUARTET (USA 2006) and Raina Stephan in LES TROIS DISPARITIONS DE SOAD HOSNI (THE THREE DISAPPEARANCES OF SOAD HOSNI, LBN/F 2011) are sampling the archives of popular culture, challenging the conventions of curation and provenance that have historically governed museum practices. These new relationships between filmmakers and museums and galleries point to a new role of the moving image in the refiguration of filmed history and the history of film.22

Found Footage, Compilation, Essay

Archiveology embraces the full spectrum of image recycling practices, including remix and ‚supercuts‘ alongside compilation, essayistic, and avant-garde practices. Found-footage filmmaking originated as a genre of experimental film, but in the last 20 years it has evolved into an important type of documentary film and a key component of gallery practice. The film fragments that are recycled are not found in the garbage or the flea-market (or not only found there), but also come from e-Bay and from official state-funded archives. Sounds and images are collected and recombined in ways that will produce new insights into the past. Much of this work is about film history, but that history is revealed to be a rich vein of collective memory, experience, and imagination. For example, Bill Morrison’s film THE GREAT FLOOD (USA 2012) comprised of footage of the Mississippi disaster of 1927 is edited without narration, allowing the archival images to come alive with their own effects, augmented by a subtle jazz guitar soundtrack by Bill Frissell.

Compared to the documentary collages of American baseball, jazz, and American national parks authored by Ken Burns, Morrison’s collage is essayistic in its openness and its refusal to pin down meaning. He offers new images, rarely before seen, to create a history of national disaster that is deeply implicated in the racial fabric of the American South. This kind of work may even be described as a form of sensory ethnography, given its lyrical evocation of human behaviour tied to specific places and times.23

In The Author as Producer Benjamin demanded that writers take up photography.24 It is not simply to document however. He calls on the activist intellectual to work on “the means of production,” which is to say, the technologies of production, in order to turn spectators into collaborators. In the revolutionary language of a Marxist-inflected activism, Benjamin describes the writer as an „engineer“ who adapts the apparatus, even if it is only a „mediating“ role in the revolutionary struggle against capitalism - which in 1934 he fully aligns with Fascism and its „spiritual“ qualities.25 If Benjamin’s rhetoric seems overblown, he nevertheless provides a more engaged model than that of Guy Debord, even if he shares with Debord an insistence on dismantling the society of the spectacle. Debord himself was a film essayist of sorts, but unlike Debord’s film practice, archiveology is a mode that involves the spectator on a sensual level, appropriating the seductive power of the media for productive purposes.

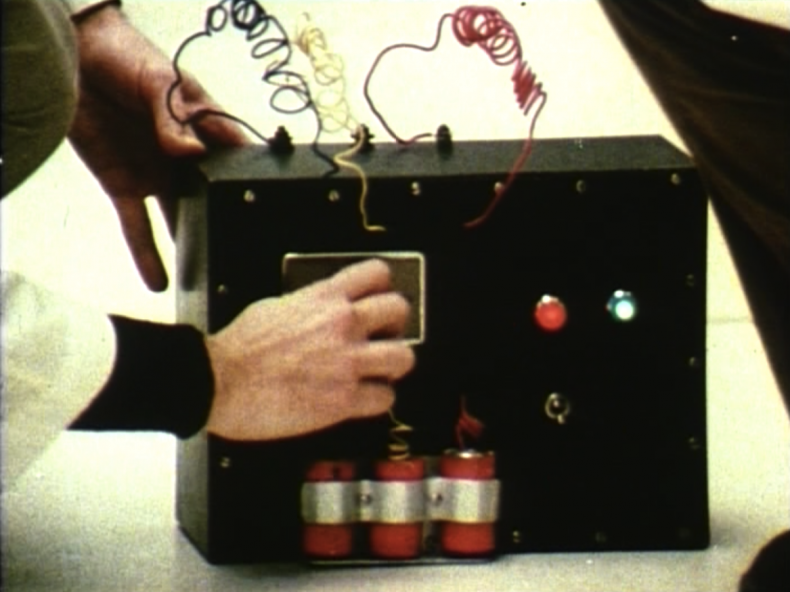

Digital cinema is an unreliable cinema, but once we give ourselves up to the performativity of visual language, the falsification of the image can be used in creative ways. For example, Kamal Aljafari’s RECOLLECTION (D 2015) is made from Israeli feature films shot in Jaffa. Using digital effects, Aljafari has removed the principle actors from the locations, leaving behind only the streets and buildings, many of them ruined by years of conflict. He lingers on the figures on the periphery, zooming into close-ups of Palestinian extras that he finally, at the end of the film, suggests may be relatives and acquaintances. The images are rendered inauthentic due to his magic tricks, but then given a new reality through his retrospective assignation of names and characters. RECOLLECTION is a film haunted by ghosts, memories, and a history of violence and Occupation. The ruined city echoes with an emptiness that the viewer is compelled to fill with imagination, and a recognition that the city is much older than the past century of conflict. Aljafari projects himself onto the archival materials in a destructive, poetic, and very personal way. Digital tools have only amplified the means by which images can be ‚played‘ with and yet a film like RECOLLECTION points toward the potential even of destroyed and ruined archives to be remade as new ways of knowing the world.

If, for Benjamin, Eugène Atget photographed Paris as if it were the scene of a crime,26 Aljafari’s depiction of Jaffa renders the entire city a site of a political, historical, and humanitarian crime. His method is precisely a matter of „Possessing the object in close-up“ and „illuminating the detail“ as Benjamin describes Atget’s practice.27 The „new way of seeing“ that Benjamin identifies in Atget’s photography of the early 20th century has been renewed once again by Aljafari, whose process starts with refilming the Israeli features with a digital camera from the screen; his pans and zooms traverse and examine the cityscapes as media. His exploration of historical displacement is a literal recovery of the city as a space of domiciliation, memory, and imagination.

In keeping with these reconsiderations of found footage as historical discourse, I am proposing that archiveology is in fact a language of the audio-visual archive. Benjamin saw film as exemplary of a second-order of technology in which an „interplay between human and nature“ is prioritized. As Miriam Hansen has elaborated, one of the key terms in this formulation is „play“. Here again, it seems as if the proliferation of archival film practices finally makes Benjamin’s theory legible. For Benjamin „room-for-play“ indicates the extent to which a mediated world contains its own fissures and points of resistance. Far from a power structure, the apparatus conceals „productive forces“ which can be redirected and restaged. This, I would argue, is the space which archival film practices now occupy, and will continue to expand. In other words, insofar as we live in the society of the spectacle with no way out, we need to reuse the remnants of image cultures past in order to better conceptualize the future.

Archiveology is a mode of film practice that draws on archival material to produce knowledge about how history has been represented; and how representations are more than simply false images, but are actually historical in themselves and have anthropological value. Often this process of layering and remediation falls into the category of the essay film. Although there is little consensus on what it is exactly, most critics would agree that the essay film involves a conjunction of experimental and documentary practice, and also that it is a mode of address which is often subjective.28 The essayistic value of archiveology lies in the way that the filmmakers allow the images to speak in their own language. One of the key features of archiveology is that it produces a critical form of recognition. The viewer is able to read the images, even if it is not clear where they come from exactly.

The City, the Phantasmagoria, and Critical Cinephilia

Essay films that draw on archival material have been made about many topics, but a frequent theme of archiveology is the city film. Rick Prelinger, who is responsible for some of the most extensive moving image archives and some of the richest thinking about moving image archives, has recently turned to the city for a number of ongoing projects of collecting, compilation, and screening. In Prelinger’s 2007 manifesto on open access, he says that „the public domain is the coolest neighbourhood in town.“29 Indeed the city is traditionally the site of flea markets, garage sales and remainder stores. Among the “objects’ in circulation are images of the city itself. Prelinger has tapped into such rich resources of city films made by the industry, amateurs and non-theatrical producers that he has been able to make continual re-makes and installments of his film presentations LOST LANDSCAPES OF DETROIT (USA 2010), LOST LANDSCAPES OF LOS ANGELES (USA 2018) and LOST LANDSCAPES OF SAN FRANCISCO (USA 2005). Rather than finish these films, Prelinger prefers to screen them theatrically, inviting the audience to collectively add the narration live.

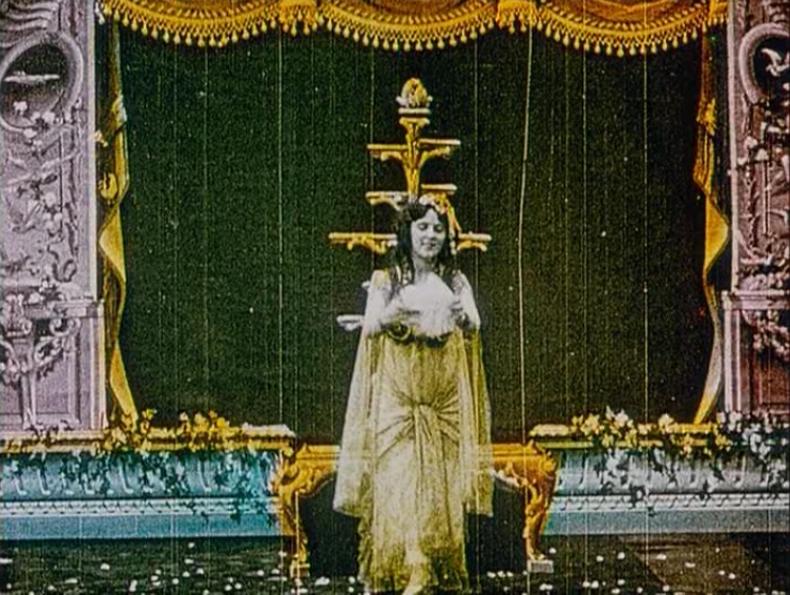

The city, like the archive, is a living, breathing entity as ‚documents‘ are continually added, and more importantly, continually ‚re-discovered‘. The surface of the archive is now; its depths are passages to the past. Thus it is always instructive to return to archive-based films, to be able to discover again what was rediscovered in the past. One of the first compilation films made in the postwar period is PARIS 1900 (F 1947) by Nicole Védrès. This film has been largely overlooked by film historians, perhaps because its director, Nicole Védrès, made too few films and was the wrong gender to become recognized as an important French auteur. It may also have been overlooked because in 1947 it challenged the usual paradigms of film classification. Jay Leyda recognized it in his book Films Beget Films, and he situated it within a history of such filmmaking that drew primarily on newsreels.30 However, Védrès takes the compilation format a substantial step forward by combining clips of fiction film footage with photographs, newsreel and actualité footage, and by the scope of her archival research. In addition to film libraries, she repurposed imagery from personal collections, flea markets and other sources including garrets, blockhouses, cellars, garbage bins and even a rabbit hutch.31 In other words, PARIS 1900 expands the concept of the archive and ‚official‘ history to include many other histories that were recorded on film and subsequently abandoned as inconsequential.

PARIS 1900 consists of excerpts from over 700 films, with original music by Guy Bernard, to represent the period often known as ‚La Belle Époque‘, from 1900 to 1914, as a mythical period of peace in which social optimism and the arts flourished in France. The film could be described as ‚superficial‘ in that it depicts Paris as a kind of image culture (and this is precisely how Bosley Crowther described it in 1950),32 and yet there is a lingering undercurrent of impending disaster that is finally realized with the commencement of the Great War in 1914. The omnipresent camera underscores the role of technology in this excitable culture and the archival excess seems indirectly responsible for the impending collapse. As Védrès herself puts it, she felt she had completed a „novel that ended tragically - although no one can tell, even now, whether it was by crime, accident or suicide - in August 1914.“33 Despite the light-hearted commentary and the playfulness of Parisian fashions, entertainments, and diversions, this post-war city film is significantly less celebratory than the famous pre-war antecedents of Vertov and Ruttman, which celebrated their own modernity, rather than a former one. PARIS 1900 is less a ‚symphony‘ than a kind of sugar-coated eulogy. Instead of nostalgia, it exhibits an undercurrent of failure and false promise.

At the centre of the film is the spectacular death of the Birdman, Franz Reichelt, leaping to his death from the Eiffel Tower in 1912. Captured by Pathé newsreel cameras, this image is emblematic of the vulnerability of the past to teleological narratives of success in which an aviator such as Bleriot is a hero and poor old Reichelt is forgotten. If Védrès manages to redeem the Birdman as a hero of an earlier age of the spectacle, her film is arguably consistent with Benjamin’s utopian hope for a flash of something transformative to emerge from the ruins of the past. Benjamin specifically insists that this spark can only be detected within a „constructed“ history that articulates not empty time, but time filled by „Jetzeit“ or ‚now time‘.34

PARIS 1900 provides an instructive point of reference between Benjamin’s moment and our own, because Védrès was working with an image-bank that was remarkably close to Benjamin’s own historical study of nineteenth-century Paris. The viewer becomes an historian such as Benjamin describes, an historian who „takes up, with regard to [the image], the task of dream interpretation.“35 The history in this film, like the history in the Arcades Project, challenges all disciplinary bounds, and respects no scientific laws. Moreover, the techniques of cutting, extracting, and fragmenting evoke the destructive edge of technology that finally brought the city of Paris to its knees, just as the absence of an auteur behind the camera evokes the terrifying role of the war machines on the horizon. The film exemplifies Benjamin’s observation that: „Overcoming the concept of ‚progress‘ and overcoming the concept of ‘period of decline’ are two sides of one and the same thing.“36

Another important example of a city film that draws on the archive is LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF (Thom Andersen, USA 2003), which director Thom Andersen describes as a „city symphony in reverse“37. Like Védrès, Anderson relies on voice-over narration that incorporates a commentary on the image into his compilation. Both these films drive home the point that cities are places where films are often made, and thus amongst the waste they create are the ruins of their own self-image. Thomas Andersen’s 2003 film LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF is an attempt to separate the virtual city of images from the ‚real‘ city of history, an attempt that is ultimately doomed to failure. Andersen’s essayistic narration is a critique of Hollywood and the ways that the film industry has appropriated Los Angeles for its various nefarious, fantastic, and duplicitous ends; but it is also a melancholy ode to a city that has had to continually remake its own history in the face of its simulacral servitude to the dream factory. Los Angeles is a comparatively young city, burdened with its own lack of historicity. The deep irony of LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF is that Andersen betrays his own obsessive cinephilia with his vast knowledge of film history, displayed in a brilliant montage of excerpts from genre cinema, auteur cinema, art cinema, and independent cinema.

Amid the dozens of clips of Hollywood movies, Andersen lingers occasionally during the 169 minutes to offer more extended interpretations of a number of key titles, including DOUBLE INDEMNITY (USA 1943), CHINATOWN (USA 1974), L.A. CONFIDENTIAL (USA 1997) and DRAGNET (USA 1951 and USA 1967). These sections function as video essays embedded in a compilation film. Andersen’s commentary is full of insight and analysis. His montage is expertly paced, and the film offers a unique perspective on the relation of film to urban space in general, as well as the specific aspects of the L.A. setting. LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF is far from comprehensive—especially since the focus is almost exclusively on the postwar city - and yet it is an excellent example of film criticism in the form of archiveology. Moreover, it has had a direct impact on film history, in its recovery and redemption of THE EXILES (USA 1961) that had been more or less ‚lost‘ until Andersen ‚found‘ it and included it in his film.38

Andersen’s narration in LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF borrows some of the postmodern critique of image culture, but complicates it with a recognition of the untimeliness of historical disjunction and displacement. By organizing his cinematic collection around the use and reuse of specific L.A. locations, Andersen evokes a key principle of archival film practices. He says „If we can appreciate documentaries for their dramatic qualities, perhaps we can appreciate fiction films for their documentary revelations.“39 Extracting a sense of place from the multitude of films set in Los Angeles, Andersen reveals cultural significance precisely by transforming Hollywood films into archival fragments.

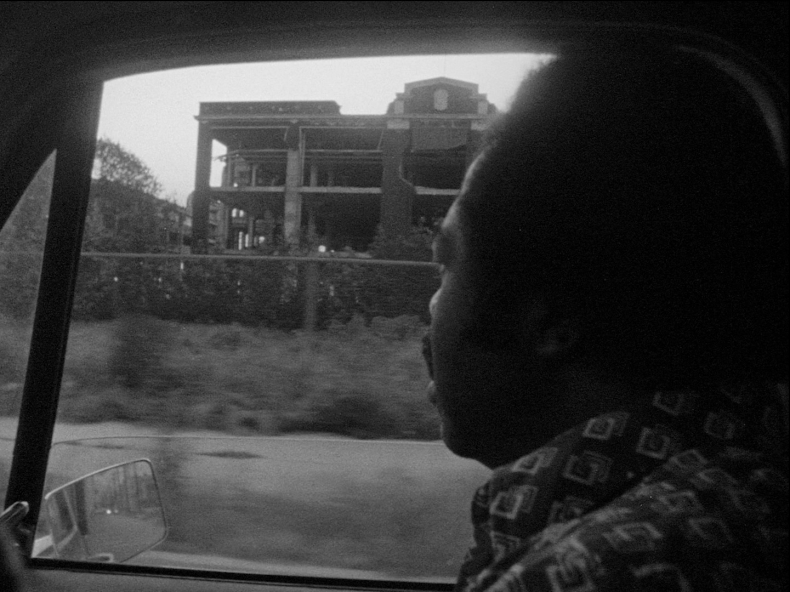

We need to ask if Andersen’s project is any less cynical, and any less futile, than the star-studded histories of the city that he dismantles, given that his dismantling is also a recycling and reprise of key scenes from the films. His critique remains couched in the language of the dream-world, and he is too much of a cinephile to dismiss the movies altogether. The film ends with a shot from BLESS THEIR LITTLE HEARTS (USA 1983) of an African-American man driving past the ruins of the Goodyear Factory on South Central Ave. The ruins, photographed in black and white, are the only ruins featured in the film, graphically illustrating the failed project of American modernity. Without the cinema, though, would we still be able to see them? Andersen’s narration notes that the factory once provided jobs for the black working class; visitors could once take tours „just as today they can take a studio tour and see how movies are made.“

In fact, LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF cannot penetrate the veil of image culture, but Andersen’s „dream interpretation“ arguably enacts the mode of allegory that Benjamin describes as „a form of expression“, and a form of writing.40 Andersen conforms to the melancholic, for whom the only pleasure is that of allegory.41 The ruined factory, shot from a moving car, completes the film on a note of movement, pointing to the interminable incompletion of the archival project, and the open-ended future of the city. Andersen’s melancholic, allegorical, language is not only an essay, it is transformative, creating a kind of memory that is always on the verge of being forgotten as the industry continues to churn out new variations on the dream of a better urban future.

If Walter Benjamin taught us anything, it’s that social relations have not kept up with changes in technologies. The promise of the new brings only repetition and melancholia. Seventy-five years after Benjamin’s death, this observation has been confirmed on multiple levels, and it is furthermore evident that nature no longer exists as something before or outside technologies, or that technology can remain separate from nature. Maybe we remember when things were otherwise, but we only have other people’s words for this other time, if it ever existed. We may have an image of another way of being, but it is constantly changing, twisting and showing other faces.

In the few direct remarks that Benjamin made about criticism, he describes the critic as a „strategist“, for whom the artwork is a „shining sword in the battle of minds.“42 In other words, he advocated a form of critical activism that was not afraid to destroy. In fact, the critic is not unrelated to the „Destructive Character“ as Benjamin defined this figure in 1931:

The destructive character stands in the front line of traditionalists. Some people pass things down to posterity, by making them untouchable and thus conserving them; others pass on situations, by making them practicable and thus liquidating them. The latter are called the destructive…What exists he [the destructive character] reduces to rubble - not for the sake of the rubble, but for that of the way leading through it.43

And in yet another variation on the theme of critical practice, Benjamin aligns it with the dream work. The „aura“ of a book can be sensed by forgetting it, and having it return in a dream. The unconscious turns impressions into „extracts“ that are recognizable in dreams.44 I emphasize the word ‚extracts‘ to foreground the implicit link between quotation and destructive memory.

LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF is an example of film criticism that is at once activist, destructive, and dreamlike. It is a critical practice grounded in the connections between the phantasmagoria and cinephilia as a critical practice. Benjamin did not specifically associate the illusionism of narrative cinema with the phantasmagoria, and yet film critics have long taken the opposite to be true: that the avant-garde counter cinema associated with Brecht, the surrealists, and the Dadaists constitutes a dismantling of the phantasmagoria. Benjamin’s name is frequently aligned with the avant-garde, but the concept of counter-cinema does not go far enough in postmodern digital culture. What happens when the avant-garde cozies up to the mainstream cinema? What happens when the avant-garde appropriates its affective properties along with its images? Joseph Cornell did this as early as 1936 with ROSE HOBART (USA 1936) and many film and media artists besides Andersen have revived that practice, which has had a remarkable resurgence in the digital era.

Works such as THE CLOCK (UK 2010), KRISTALL (Christoph Girardet / Matthias Müller, D 2006) and PHOENIX TAPES (Christoph Girardet / Matthias Müller, D 2000) are examples of a mode of archiveology that is dedicated to the lure of the film image and the desires embedded in mainstream narrative cinema. These are works that are borne of a certain kind of cinephilia, or love of cinema that involves not only ‚love‘, but a recognition of the social relations embedded in the cinema experience. By aligning that cinephilia with Benjamin’s phantasmagoria, I believe that cinephilia can be considered a form of critical cultural anthropology.

Archiveology involves the conception of images as things in the world. Torn out of their narrative homelands, they become cultural documents, allegories of their own production, and potentially ‚resurrected‘ to speak on their own terms. While these images retain an autonomy that leads out of the phantasmagoria, images of movie stars, and scenes from familiar movies - the moments that attract the cinephile - lead back into the phantasmagoria, and appropriate not only the image-thing, but its sensory memory.

Benjamin’s theory of the phantasmagoria is based on the magic lantern shows of Etienne-Gaspard Robertson, and developed as a conjunction of Marxist ideology and Freudian dreamscapes. The phantasmagoria became the general term for an array of visual devices, because it best describes the way that ideological experience is expressed.45 It is not reflective, but an expression that is „mediated through imaginative subjective processes.“ Benjamin privileges the term in the Arcades Project because it is taken from the „time and place“ of his study, 19th century Paris. Ideological transposition, or the process by which the subject is caught up in ideology, is a demonic process, for which the iconography and procession of ghosts and the living dead is most appropriate. Margaret Cohen describes the phantasmagoria as the demonic doppelganger of allegory.46

Cohen is led to inquire how allegory fits into this schema, and concludes that because it describes the commodity form, „it cannot grasp the palpable way in which the commodity form ‚appears‘.“47 The critical method that Benjamin assigns to profane illumination and the dialectical image could not yet be performed from within the phantasmagoria itself during his lifetime. If the 19th century phantasmagoria is an important predecessor of narrative illusionism (and Jean Baudrillard’s Simulacra in turn), then critical cinephilia may be the archiveological method of demystification that neither Cohen nor Benjamin were able to recognize.

The conventional view of cinephilia points toward a love of cinema that is somehow beyond reason, somewhat involuntary and deeply subjective. And yet, despite its affinities with the collector and the trivia-hound, the fetishist and the helplessly addicted, I believe that it might provide the tools for the production of knowledge. Cinephilia need not be associated simply with the subjective state of the critic, his or her personal affinities with the text, the passion of writing about film, or the conversations between cinephiles.48 It might also lead to a greater understanding of cultural history and the sensory, emotive, and affective worlds of the past.

In his essay on cinephilia, Thomas Elsaesser suggests that cinema might be thought of as „one of the great fairy-tale machines or ‘mythologies’ that the late 19th century bequeathed to the 20th, and that America, originally inheriting it from Europe, has in turn passed to the rest of the world.“49 The genre-system of popular cinema, overlaid with the sensuality of modern experience, is arguably crystallized in cinephilia, which in turn becomes a kind of prism of the dream-life of global modernity.

The potential of cinephilia as a mode of cultural anthropology is implicit in the destructive practice of film criticism in which the cinematic phantasmagoria is dismantled into its documentary fragments. The cinematic phantasmagoria is a good term for the duality of the cinematic spectacle, as on one hand a closed world of artifice and fantasy; and on the other, a document of social practices, rituals and audio-visual culture. By examining more closely the role of „things“ in the films, and the role of the bodies of actors as people (rather than characters), „the cinematic“ can also be thought of as a mode of cultural knowledge. Paul Willeman suggests that „we are talking about the articulation between representation and history in cinema. The concrete, local, historical detail shines through…“50 Critical cinephilia, as practiced in writing, through the video essay, or archiveology, would thus be able to reveal these details in such a way that cultural history is experienced rather than simply described.

Critical cinephilia, in other words, should theoretically enable us to restore the dimensions of affect, enchantment, pleasure and emotional investment to film studies, without abandoning the theoretical goals of cultural critique that informed the critique of narrative pleasure. Instead of a deterministic, mechanical model of pleasure, perhaps we can find a more selective and subjective means of connecting with narrative cinema.

Conclusion: The Document

By rethinking found footage as archiveology, I hope to emphasize the documentary value of collecting and compiling fragments of previously filmed material, but at the same time, the very concept of documentary becomes more complicated. How and when does an image become a document? I would argue that it does so as soon as it is excised from its narrative origins, or from its original “documentary” form, if that is where it comes from. In One-way Street Benjamin distinguished between the artwork and the document in a section called 13 Theses against Snobs. Among his pithy pronouncements on the document, he says:

-The more one loses oneself in a document, the denser the subject matter grows.

-A document overpowers only through surprise.

-The document’s innocence gives it cover.51

Digital tools have made archiveology accessible and available as a critical practice to amateurs and artists alike. We need to distinguish between those practices that push back against historical transparency and those that access the archive to construct seamless histories of linear causality. Benjamin’s historiography is based on a non-linear conception of correspondences between past and future, and on the shock or crystallization of the moment produced through juxtaposition and montage. His aesthetics of awakening and recognition are techniques of interruption of the ‚flow‘ of images that conventional historicism relies upon. The death of ‚film‘ and the rise of digital media has effectively enabled and produced a new critical language that we are only really learning to speak. As video essays begin to proliferate as a mode of critical discourse, we need to retain the techniques of collage within compilation modes, and this depends in part on a recognition of detail and density; it depends on surprise, and it depends on the kind of inversion of background and foreground that archiveology can produce. If fragments of fiction film become documents of fashion and architecture, fragments of documentary become recognizable as performances.

- 1This essay is comprised of selections from chapters 1, 3, and 5, in the newly published title Archiveology, Catherine Russell. Copyright, 2018, Duke University Press. All rights reserved. Republished by permission of the copyright holder. www.dukeupress.edu

- 2Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. Howard Eiland and Kevin McLaughlin, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 460.

- 3Catherine Russell, Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices, forthcoming from Duke University Press, 2018. This article is a translation of portions of that book.

- 4Catherine Russell, Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999).

- 5Joel Katz, “From Archive to Archiveology,” Cinematograph 4 (1991): 96-103. I also attempted to “define” the term in a “Lexicon for the 20th century A.D.” Public 19 (2000) eds. Christine Davis, Ken Allan and Lang Baker, 22.

- 6Thomas Elsaesser, “The Ethics of Appropriation: Found Footage Between Archive and Internet,” in Found Footage Magazine Issue #1 (October 2015): 30-37.

- 7A German anthology was published in 2009 of articles by a range of theorists including Derrida and Foucault, plus numerous other literary and art theorists such as Boris Groys, Benjamin Buchloh and Paul Ricoeur. Ebeling, Knut, and Stephan Günzel, Archivologie: Theorien des Archivs in Philosophie, Medien und Künsten (Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2009).

- 8Lynne Huffer, Mad for Foucault: Rethinking the Foundations of Queer Theory, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 177.

- 9Rick Prelinger, “Points of Origin: Discovering Ourselves through access,” Moving Image 9, no. 2 (2009): 164–75.

- 10Sven Spieker, The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy, ( Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2008), xiii.

- 11Walter Benjamin, “Excavation and Memory,” Selected Writings. Vol. 2, 1927–1934, ed. Michael J. Jennings, Howard Eiland, and Gary Smith, trans. Jonathan Livingstone et al. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999), 576.

- 12Verwoert, Jan. “Apropos Appropriation: Why Stealing Images Today Feels Different.” Art and Research 1, no. 2 (2007). http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/verwoert.html.

- 13Emma Cocker, “Ethical Possession: Borrowing From the Archives,” In Cultural Borrowings: Appropriation, Reworking, Transformation, ed. Iain Robert Smith, A Scope e-Book . 2009: 92–110.

- 14Cocker, 92.

- 15Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 61.

- 16Okwui Enwezor, “Archive Fever: Photography Between History and the Monument,” in Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, (Gottingen: Steidl, 2009), 11-50.

- 17Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka, “Introduction: An Archaeology of Media Archaeology,” in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, Implications, ed. Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011), 6.

- 18Jussi Parikka, “Media Archaeology as a Transatlantic Bridge,” in Wolfgang Ernst, Digital Memory and the Archive, ed. Jussi Parikka, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 29.

- 19Parikka, 29.

- 20Miriam Hansen, Cinema and Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor Adorno (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 162.

- 21Giovanna Fossati, “Found Footage: Filmmaking, Film Archiving and New Participatory Platforms, in Found Footage: Cinema Exposed, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012): 177-184.

- 22For a more substantial of the role of archive-based films in the Gallery and Museum, please see Erika Balsom, Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013).

- 23Scott MacDonald, “Conversations on the Avant-Doc: Scott MacDonald Interviews.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 54, no. 2 (2013): 259-330.

- 24Walter Benjamin, “The Author as Producer,” Selected Writings Vol 2, 775.

- 25Ibid, 780.

- 26Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility (Second Version),” Selected Writings. Vol. 3, 1935–1938, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, trans. Edmund Jephcott et al. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002), 108.

- 27Walter Benjamin, “Little History of Photography,” Selected Writings, Vol 2: 518-19.

- 28Timothy Corrigan, The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011); Laura Rascaroli, The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film (London: Wallflower Press, 2009).

- 29Rick Prelinger, "On the Virtues of Preexisting Material: A Manifesto," [2007] reprinted in Contents Magazine No. 15 (2016).

- 30Jay Leyda, Films Beget Films, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1964), 79.

- 31Nicole Védrès, quoted in the Toronto Film Society programme notes for Monday February 8, 1954. The film was scheduled to play in Toronto on this date, but the print did not arrive. The screening was rescheduled in May 1987 more than thirty years later. Védrès provided notes for the film in English for the 1954 screening.

- 32Crowther, “Snows of Yesteryear: Paris 1900 has Faults of Most Album Films New York Times, October 29, 1950; Anonymous, “Paris 1900, France, 1948,” Monthly Film Bulletin 19, no. 216 (1952): 100.

- 33Védrès, op.cit.

- 34Walter Benjamin, “On the concept of History,” Selected Writings. Vol. 4, 1938–1940, ed. Howard Eiland and Michael W. Jennings, trans. Edmund Jephcott et al. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003), 395.

- 35Benjamin, The Arcades Project, 464.

- 36Ibid, 460.

- 37Thomas Andersen, Voice-over commentary in Los Angeles Plays Itself.

- 38For more on the “discovery” of The Exiles as an archival film, please see “The Restoration of THE EXILES: The Untimeliness of Archival Cinema,” Screening the Past 34 September 2012 http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-34/

- 39Thomas Andersen, Voice-over commentary in LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF.

- 40Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama. trans. John Osborne. (London: nlb/Verso, 1977), 162.

- 41Ibid, 185.

- 42Benjamin, “One-Way Street,” Selected Writings Vol. 1. 1913–1926, ed. Marcus Bullock and Michael W. Jennings, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996), 460.

- 43Benjamin, “The Destructive Character,” Selected Writings Vol.2, 542.

- 44Benjamin, “The Task of the Critic,” Selected Writings Vol. 2, 548.

- 45Margaret Cohen, Profane Illumination, Walter Benjamin and the Paris of Surrealist Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 240.

- 46Cohen, 236.

- 47Cohen, 250.

- 48See Girish Shambu, The New Cinephilia, (Montreal: Caboose, 2014) for a recent discussion of the practice of cinephilia as experiential and social, but not necessarily critical or activist, or able to produce cultural knowledge.

- 49Elsaesser, “Cinephilia, Or The Uses Of Disenchantment,” in Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory, ed. Marijke De Valck and Malte Hagener, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005), 32-33.

- 50Willemen, Looks and Frictions: Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory, Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory (London: British Film Institute, 1994), 254-55.

- 51Benjamin, “One Way Street,” 459.

Andersen, Thomas. Voice-over commentary in LOS ANGELES PLAYS ITSELF (Thom Andersen, USA 2003).

Anonymous. “PARIS 1900, France, 1948,” Monthly Film Bulletin 19, no. 216 (1952).

Balsom, Erika. Exhibiting Cinema in Contemporary Art (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2013).

Benjamin, Walter. “Excavation and Memory,” Selected Writings. Vol. 2, 1927–1934, ed. Jennings, Michael J. / Eiland, Howard / Smith, Gary. Trans. Livingstone, Jonathan et al. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

Benjamin, Walter. “Little History of Photography,” Selected Writings, Vol 2.

Benjamin, Walter. “On the concept of History,” Selected Writings. Vol. 4, 1938–1940, ed. Eiland, Howard / Jennings, Michael W. / trans. Jephcott, Edmund et al. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003).

Benjamin, Walter. “One-Way Street,” Selected Writings Vol. 1. 1913–1926, ed. Bullock, Marcus / Jennings, Michael W. , (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996).

Benjamin, Walter. “The Author as Producer,” Selected Writings Vol 2.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Destructive Character,” Selected Writings Vol.2.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Task of the Critic,” Selected Writings Vol. 2.

Benjamin, Walter. “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility (Second Version),” Selected Writings. Vol. 3, 1935–1938, ed. Eiland, Howard / Jennings, Michael W / trans. Jephcott, Edmund et al. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2002).

Benjamin, Walter. One Way Street (London: NLB, 1979).

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project, trans. Eiland, Howard / McLaughlin, Kevin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1999).

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project.

Benjamin, Walter. The Origin of German Tragic Drama. trans. John Osborne. (London: nlb/Verso, 1977).

Cocker, Emma. “Ethical Possession: Borrowing From the Archives,” In Cultural Borrowings: Appropriation, Reworking, Transformation, ed. Smith, Robert. A Scope e-Book. 2009.

Cohen, Margaret. Profane Illumination, Walter Benjamin and the Paris of Surrealist Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

Corrigan, Timothy. The Essay Film: From Montaigne, After Marker (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

Crowther, Bosley. “Snows of Yesteryear: Paris 1900 has Faults of Most Album Films", New York Times, October 29, 1950.

Ebeling, Knut / Günzel, Stephan. Archivologie: Theorien des Archivs in Philosophie, Medien und Künsten (Berlin: Kulturverlag Kadmos, 2009).

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Cinephilia, Or The Uses Of Disenchantment,” in Cinephilia: Movies, Love and Memory, ed. De Valck, Marijke / Hagener, Malte (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2005).

Elsaesser, Thomas. “The Ethics of Appropriation: Found Footage Between Archive and Internet,” in Found Footage Magazine Issue #1 (October 2015).

Enwezor, Okwui. “Archive Fever: Photography Between History and the Monument,” in Archive Fever: Uses of the Document in Contemporary Art, (Gottingen: Steidl, 2009).

Fossati, Giovanna. “Found Footage: Filmmaking, Film Archiving and New Participatory Platforms, in Found Footage: Cinema Exposed, (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012).

Hansen, Miriam. Cinema and Experience: Siegfried Kracauer, Walter Benjamin, and Theodor Adorno (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

Huffer, Lynne. Mad for Foucault: Rethinking the Foundations of Queer Theory, (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).

Huhtamo, Erkki / Parikka, Jussi. “Introduction: An Archaeology of Media Archaeology,” in Media Archaeology: Approaches, Applications, Implications, ed. Erkki Huhtamo and Jussi Parikka, (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011).

Katz, Joel. “From Archive to Archiveology,” Cinematograph 4 (1991).

Leyda, Jay. Films Beget Films, (New York: Hill and Wang, 1964).

MacDonald, Scott. “Conversations on the Avant-Doc: Scott MacDonald Interviews.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 54, no. 2 (2013).

Parikka, Jussi. “Media Archaeology as a Transatlantic Bridge,” in Wolfgang Ernst, Digital Memory and the Archive, ed. Jussi Parikka, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).

Prelinger, Rick. "On the Virtues of Preexisting Material: A Manifesto," [2007] reprinted in Contents Magazine No. 15 (2016).

Prelinger, Rick. “Points of Origin: Discovering Ourselves through access,” Moving Image 9, no. 2 (2009).

Rascaroli, Laura. The Personal Camera: Subjective Cinema and the Essay Film (London: Wallflower Press, 2009).

Russell, Catherine. “Archiveology”. In: “Lexicon for the 20th century A.D.” Public 19 eds. Davis, Christine / Allan, Ken / Baker, Lang. (New York 2000).

Russell, Catherine. Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices, forthcoming from Duke University Press, 2018.

Russell, Catherine. Experimental Ethnography: The Work of Film in the Age of Video, (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999).

Russell, Cathrine. “The Restoration of THE EXILES: The Untimeliness of Archival Cinema,” Screening the Past 34 September 2012 http://www.screeningthepast.com/issue-34/

Shambu, Girish. The New Cinephilia, (Montreal: Caboose, 2014).

Spieker, Sven. The Big Archive: Art from Bureaucracy, ( Cambridge, MA: mit Press, 2008).

Verwoert, Jan. “Apropos Appropriation: Why Stealing Images Today Feels Different.” Art and Research 1, no. 2 (2007). http://www.artandresearch.org.uk/v1n2/verwoert.html.

Willemen, Paul. Looks and Frictions: Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory, Essays in Cultural Studies and Film Theory (London: British Film Institute, 1994).