Issue 1: The Long Path to Audio-visual History

The first issue of the journal Research in Film and History is based on the edited volume Film und Geschichte and Film als Forschungsmethode, published in 2015 and 2018 by Bertz + Fischer (in German). Prior to their publication in the journal, the articles were carefully reviewed and in some cases substantially revised. They are intended to serve as a catalyst for further debate, new research approaches, and critical discussion of existing interdisciplinary research into film and history.

Film’s special affinity with history is nearly as old as the medium itself: by 1896 Max Skladanowsky had already filmed his brother, Eugen, in the role of the Prussian king, Friedrich II.1 Even though by 1898 historians such as Boleslas Matuszewski were examining film’s relevance as a historical source,2 in most cases historiography regarded the medium as a testament to its time or as an aesthetically oriented way of writing film history. Moreover, ever since Siegfried Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler,3 there have been continual attempts to understand socio-historical developments, such as the National Socialists’ rise to power in the early nineteen-thirties, through the analysis of contemporaneous films. Still, the cinema—and with it the writing of film history—was not recognized as a legitimate area of reflection for historians. Indeed, it was not until the mid-nineteen-seventies that Marc Ferro demanded a turn to the medium in order to open up a new field, that is, the history of human ideas and desires.4 Ferro was not simply interested in individual film documents; he argued that every film should be considered a document of history, a way of reading its themes and production conditions.

Since the nineteen-seventies this development has been accompanied by an important change in film studies: various approaches have attempted to reformulate the writing of film history. In the nineteen-eighties these critical efforts coalesced under the term New Film History, indicating that aesthetically oriented film history could expand to include economics, the history of technology, sociology, contemporary history, and so on.5 In the wake of this upheaval, film scholars called for a differentiated, more complex understanding of how to write and think about history. Finally, the so-called linguistic turn provided an important stimulus; in this context, Hayden White is a particularly important figure.6 His reference to the narrative character of writing history, which deliberately structures data, also sharpened the prospects for film. Subsequently, Robert Rosenstone positioned a new form of historiography via the medium and envisioned a multimedia form of historical scholarship for the future.7 Robert Burgoyne proposed a similar notion in describing the (historical) film as a critical dialogue between the present and the past.8 This perspective of the relationship between film and history has already undergone critical consideration in the context of the documentary film.9

Whereas historians have only sporadically dwelled on these issues hitherto, film scholars have formulated more elaborate approaches, based on assumptions that viewing and experiencing film and other media images shape historical events.10 They regard cinema as a site of historical consciousness that supersedes an image of historical events and allows for the comprehension of past sensibilities.11 For its part, historiography’s “visual history” has established yet another field of research in recent years, picking up on related questions and adapting the pictorial turn via historical scholarship.12 Although aesthetics have remained a longstanding lacuna in the historiographical observation of source images, historian Gerhard Paul has consciously made it his focus. This presages the possibility for a new kind of understanding, a shift away from the dominance of writing to the dominance of images, which is, according to Paul, also the result of the completely new opportunities afforded by researching images.13 In this context, extensive archives (for example, the Shoah Foundation’s Visual History Archive) have opened, demonstrating that, above all, contemporary history benefits from this historiographical expansion.

Even if cinema’s acoustic elements are taken into consideration here, little research has been conducted into the audio history of film. Despite the fact that film sound has achieved more scholarly attention since the nineteen-eighties, research has focused largely on the history of aesthetics and production or technology. To be sure, individual efforts have examined the subject within the context of the cultural history of sound recording;14 nevertheless, its general significance to historical models or the construction of historical experience has suffered scant and piecemeal exploration. One exception is Richard Dyer’s study of the Hollywood career of the African-American singer Lena Horne. Dyer conducts an exemplary study of Horne’s voice in film and television productions, while analyzing the studio-regulated vocals (and sound) from cultural-historical and socio-political perspectives.15 In turn, Carolyn Birdsall’s recent study, Nazi Soundscapes, uses Düsseldorf to exemplify the cultural implications of sound and hearing under National Socialism—and also explicitly considers film production.16 The e-journal Nach dem Film has devoted an issue to the audio history of film, attempting to extrapolate the key domains of inquiry in this field of research through programmatic texts and exploratory case studies.17 These exceptions notwithstanding, it must be noted that historians have paid little regard to film’s auditory potentials, even if attempts have been made to comprehend visual history as a society of “co-viewers,” as well as “co-listeners,” as Ralph Schock’s and Gerhard Paul’s extensive volume, Der Sound des Jahrhunderts, underscores.18

On the whole, it is clear that the interpretation of political and contemporary historical events is—and will increasingly continue to be—carried out via audiovisual media.19 Documentary photography and film flank historiography, while fictional features continue to configure popular adaptations of historical narratives. With the understanding that media communicate historical knowledge,20 film functions as a way of aesthetically and narratively shaping notions and the comprehension of history; it not only illustrates scenes of grand historical themes or illuminates the biographies of historical figures, it furthermore conveys historical understanding in audiovisual form. In this way, film shapes images of the world, influences perspectives, and competes with established historiography, as well as with other cultural memory techniques.21

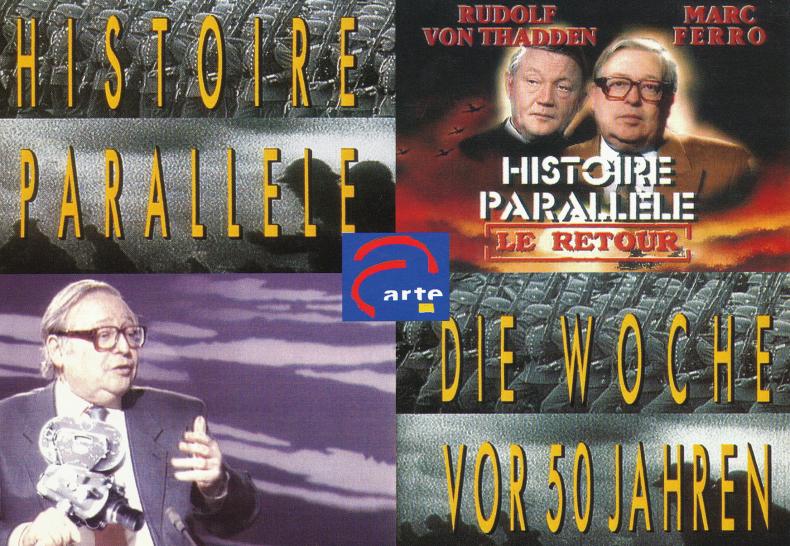

The present collection provides current essays on these positions, located at the intersection of film studies and historiography. At its core is the question of how films generate and model notions of history through sound and visuals, and allow them to be experienced. The articles in the first issue can be grouped into three main categories. The first category concerns scholarship on archiving and archival materials. Thomas Elsaesser uses Harun Farocki’s AUFSCHUB / RESPITE (D / KOR 2007) to demonstrate how the film—a re-reading of historical archival footage—returns its own future to the past. Sven Kramer also concentrates on dealing with documentary film materials from the period of the Shoah, focusing on historiography’s altered understanding of film as a scientific practice and on filmmaking as an artistic practice. Catherine Russell characterizes the term 'archiveology' as a critical method which helps to understand the aesthetics and politics of the archive in digital culture. Anne Barnert questions institutional powers of recollection, using the Staatlichen Filmdokumentation (State film documentation) in East Germany’s Filmarchiv (film archive) as her example. She examines how most film archival documentation is concentrated within the organization itself, and how these procedures influenced the representation of history in film. With Marc Ferro’s DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / THE WEEK FIFTY YEARS AGO / PARALLEL HISTORY (D / F 1989–2001) Matthias Steinle traces a trajectory in the televisual experience and analysis of historical images.

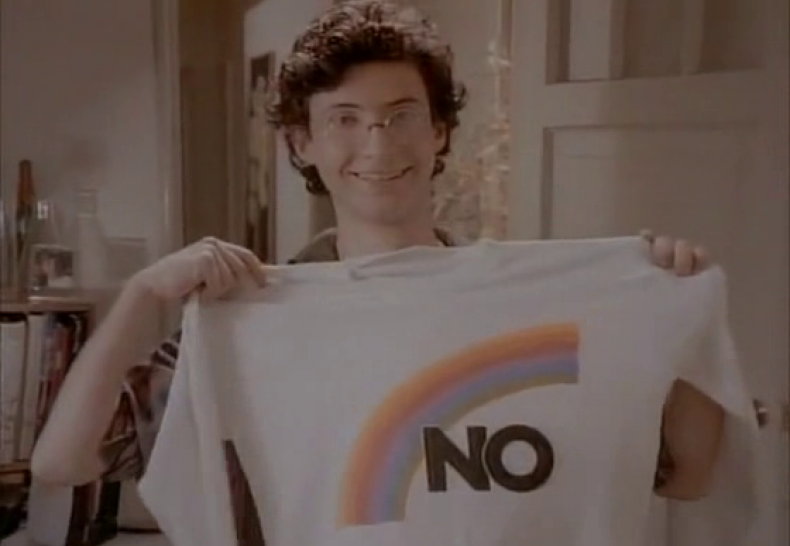

The second category of articles focuses on the migration of images and sounds in (film) historical contexts. Through the example of early postwar German cinema and between the poles of historical events and individual history, Bernhard Gross investigates to what extent film itself constructs history. Winfried Pauleit examines how sound interventions in Tommy Lee Jones’s Western THE THREE BURIALS OF MELQUIADES ESTRADA (2005) question narrative and visual constructs of history and create instead a political aesthetic based on sound. Delia González de Reufels employs Pablo Larraín’s film NO! (2012) to appraise the role of contemporary media images in the analysis and appropriation of the history of the Chilean military dictatorship, inquiring into how original recordings from the nineteen-eighties “migrated” into a contemporary dramatic film to contribute to a re-interpretation of a historical process and its consequences.

The third category comprises articles dealing with the modeling and appropriation of history through film. Vrääth Öhner begins with film soundtracks to analyze the process of seeking presence in historical documentation, comparing the first of the twelve-part series ÖSTERREICH I / AUSTRIA I (AUT 1988) with OSTMARK WOCHENSCHAU / AUSTRIAN WEEKLY NEWS (AUT 1938). Using the short films SILENCE (UK 1998), directed by Sylvie Bringas and Orly Yadin, and HELDENKANZLER / HEROIC CHANCELLOR (D 2011), directed by Benjamin Swiczinsky, as his examples, Rasmus Greiner describes the voice-over as a mode of narrating history through contemporary witnesses, which evokes subjective modeling and reflections of writing history through film. Finally, Sabine Moller outlines empirical research into the association between watching film and awareness of history, using interviews on FORREST GUMP (USA 1994).

The fourth and last category of articles is devoted to current approaches to Siegfried Kracauer in the age of New Film History. Gertrud Koch characterizes Kracauer’s theory of history and film between philosophical realism and the critique of historicism. Nicholas Baer locates Kracauer in relationship to the crisis in historicism, using as his example THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (D 1920), in order to reconsider the foundations of New Film History. And with Kracauer’s help, Mason Allred points out how historical films use the human body to make it possible for the embodied audience to experience “history.”

Winfried Pauleit, Delia González de Reufels, and Rasmus Greiner

Bremen, November 23, 2018

Suggested Citation: Pauleit, Winfried; González de Reufels, Delia; Greiner Rasmus: Issue 1: The Long Path to Audio-visual History. Editorial. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–4. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14787.

- 1See Klaus Kreimeier, Die UFA-Story: Geschichte eines Filmkonzerns (Frankfurt 2002), 16.

- 2Boleslas Matuszewski, Une Nouvelle Source de l'Histoire. Création d'un Dépot de Cinématographie Historique (Paris 1898).

- 3Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film (Princeton, NJ 1947).

- 4Marc Ferro, Cinema and History (Detroit 1988) Originally published as Cinéma et histoire (Paris 1977).

- 5See Thomas Elsaesser, “The New Film History,” Sight and Sound 55.4 (1986): 246-251.

- 6Hayden White, “Das Problem der Erzählung in der modernen Geschichtstheorie,” in Theorie der modernen Geschichtsschreibung, ed. Pietro Rossi (Frankfurt 1987), 57–106; and Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in 19th-Century Europe (Baltimore, MD 1973).

- 7Robert A. Rosenstone, Visions of the Past: The Challenge of Film to Our Idea of History (Cambridge, MA 1995).

- 8Robert Burgoyne, The Hollywood Historical Film (Malden, MA 2008).

- 9Eva Hohenberger, Judith Keilbach, eds., Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit. Dokumentarfilm, Fernsehen und Geschichte (Berlin 2003).

- 10See Vivian Sobchack, ed., The Persistence of History: Cinema, Television and the Modern Event (New York 1996).

- 11See Hermann Kappelhoff, Realismus: Das Kino und die Politik des Ästhetischen (Berlin 2008).

- 12See Gerhard Paul, ed., Visual History: Ein Studienbuch (Göttingen 2006).

- 13Gerhard Paul, “Visual History, Version: 2.0,” in Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, October 29, 2012. accessed January 31, 2015. https://docupedia.de/zg/Visual_History_Version_2.0_Gerhard_Paul?oldid=8….

- 14Ute Holl, “Bioacoustic Media: Making Animals Speak Repeatedly,” in Animals and the Cinema: Classifications, Cinephilias, Philosophies, ed. Sabine Nessel et al. (Berlin 2012), 97–114.

- 15Richard Dyer, “Singing Prettily: Lena Horne in Hollywood,” in Word and Flesh: Cinema Between Text and the Body, ed. Sabine Nessel et al. (Berlin 2008), 126–135.

- 16Carolyn Birdsall, Nazi Soundscapes: Sound, Technology and Urban Space in Germany 1933–1945 (Amsterdam 2012).

- 17“Audio History des Films” (2015), Nach dem Film no. 14, accessed January 31, 2015. http://www.nachdemfilm.de/content/no-14-audio-history.

- 18Thomas Lindenberger, “Vergangenes Hören und Sehen. Zeitgeschichte und ihre Herausforderung durch die audiovisuellen Medien,” in Zeithistorische Forschungen/Studies in Contemporary History, online edition, (1/2004, H. 1), accessed January 31, 2015. http://www.zeithistorische-forschungen.de/16126041-Lindenberger-1-2004. See also: Gerhard Paul and Ralph Schock, eds., Der Sound des Jahrhunderts. Geräusche, Töne, Stimmen 1889 bis heute (Bonn 2013).

- 19Stephen Lowry, Pathos und Politik. Ideologie in Spielfilmen des Nationalsozialismus (Tübingen 1991). See also Gerhard Paul, “Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Die visuelle Geschichte und der Bildkanon des kulturellen Gedächtnisses,” in Das Jahrhundert der Bilder, ed. Gerhard Paul (Bonn 2008), 14–39.

- 20White, Problem der Erzählung. See also Hohenberger and Keilbach, Gegenwart der Vergangenheit.

- 21Kracauer, Caligari; see also Paul, Jahrhundert der Bilder; see also Jacques Rancière, “Die Geschichtlichkeit des Films,” in Gegenwart der Vergangenheit, ed. Hohenberger and Keilbach, 230–246.