A Living Document

Unpacking the Memory of Reinhard Wiener’s Private Film from Liepaja (1941)

Table of Contents

From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards

TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935)

Contested Memory

DER EWIGE JUDE (1940)

From Home Movie to Historical Document

A Living Document

Archiving the Ghetto

The Westerbork Film

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias. “A Living Document: Unpacking the Memory of Reinhard Wiener’s Private Film from Liepaja (1941).” Research in Film and History 7 (2025): 1–55. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/24045.

In early February 1979, Reinhard Wiener, a government secretary at the Ministry of the Interior in the German federal state of Baden-Württemberg, wrote a letter to the German Federal Archives regarding a private film, which he had shot during his time as a naval soldier in the Latvian coastal city of Liepaja (German: Libau), where he was stationed from 1941 to 1942 in an anti-aircraft unit as part of the German occupying forces (Video 1).1 The film shows several executions of Jewish men. They are driven from trucks by members of the German SD (security service) and the Latvian Heimwehr (auxiliary police) to a trench that had been dug near the lighthouse. There they are shot by a firing squad of the Einsatzgruppen (paramilitary killing squads). Numerous onlookers have gathered on the old fortifications surrounding the execution site. Many of them are members of the German Wehrmacht (armed forces) and the Kriegsmarine (German navy). In Liepaja, as in many other places in the countries invaded and occupied by Germany, such executions were ordered shortly after the invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1942. In addition to Jews, Latvian resistance fighters and patients of nursing homes were also murdered in Liepaja.

In his letter to the archive, Wiener explains the historical significance of his film.2 The Federal Archives were hesitant to purchase a copy, and therefore Wiener was eager to stress its particular importance. A substantial part of his argument was that his film had to be seen as a “living document of the events in Libau” that constitutes unique historical evidence for the systematic mass killings in many Eastern European countries following the German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941.3

How far can such a shocking film, which is clearly about death depicting atrocities and showing the continuous killing of innocent civilians, be labeled as “living”? How can a film that presents the perspective of a German soldier on the atrocities committed during ‘Operation Barbarossa’ be considered a “document”?

Based on Wiener’s retrospective description of the film, I will introduce and classify the footage from 1941, contextualize it according to the current state of research and then examine its early use. My aim is to reflect on the extent to which the film itself has become “living” in the sense that it was detached from its specific context of origin and, in particular, was used to visualize new interpretations, literally new versions, of the historical events through new arrangements of the individual shots.

Reading the fragmentary footage from June 1941 as a “living document” allows us to review it within the framework of traces preserved by the camera, specifically regarding the lives, biographies and identities of the people depicted in the film. Framing it as “living document” sheds light on the changing status of archive footage depending on its specific use, which I have analyzed with respect to Wiener’s film at a different occasion.4 Back then I suggested distinguishing different phases of usage that result in a changing status of the film, transforming it from a wartime trophy to juridical evidence and finally into a cinematic historical document. This transformation demonstrates the traveling character of historical film footage, which migrates into different films and resonates with different phases of memory. In the following, I review Wiener’s film as a multilayered carner memory that includes the content of the film as well as its specific context and its use and circulation in other films.

Unpacking Memory

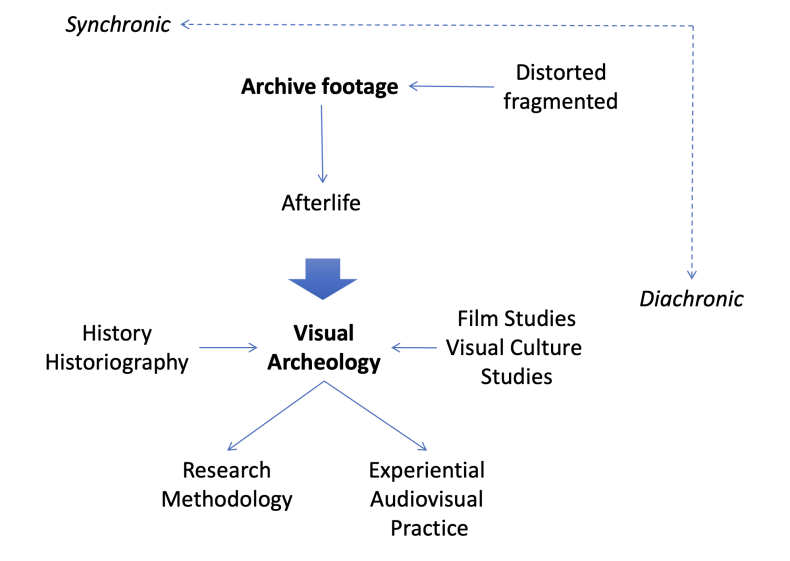

My approach to unpack the various layers of memory entrenched in and attached to Wiener’s film is informed by a variety of theoretical and methodological approaches to explore and analyze historical film footage that constitute an interdisciplinary mixed-methods approach of ‘visual archeology’.

While archaeology is typically concerned with ‘dead history’, which is reconstructed through remnants of the past, visual archeology of cinematic ‘remnants’ has the potential to explore how the past continues to ‘live on’ in the present through constant forms of appropriation and renewed interpretation of historical footage and films. In this view, fragmentary and ephemeral archive films are perceived “as traces that need to be understood in a certain context, appropriated, arranged, and re-read. Such visual exploration […] discovers the agency incorporated in the preserved images.”5 It is based on a model for researching historical film footage, which I introduced elsewhere as

a methodology to explore and investigate archive footage from the Holocaust. […] In a new and innovative way this approach includes also the afterlife of archive films, their circulation and migration through other films and media, and thus takes into account their later use and appropriation.6

As a first step, this includes a precise ‘description and analysis of the content’ of archival footage as if its context was unknown; second, the ‘exploration of the historical context’ and production background as part of a recontextualization of the footage, and third, the ‘investigation of the later use’ of the footage in other films and exhibition contexts. Jean-Benoît Clerc uses a similar approach in his recently published comprehensive study of Wiener’s film. He structures his investigation into a description of the film, a presentation of the historical context and an examination of the use of the film up to the 2000s.7

In this way, the footage is examined at both a synchronous and a diachronic level (Fig. 1). On the synchronic level, the generally rather fragmented and distorted material is contextualized. On the diachronic level, its afterlife comes into focus. The analysis, contextualization and discussion of the film footage is based on an interdisciplinary interplay of methods from film studies, visual culture studies and art history on the one hand and history and historiography on the other, which includes experimental curatorial practices as expressed, for example, in video essays as part of the research procedure.8

A key technique for the synchronic analysis of archive footage that combines film analysis and art history as well as curatorial practice and academic research is the “interpretative montage” introduced by art historian Georges Didi-Huberman using the example of the secret photographs of the Jewish Sonderkommando from Auschwitz. This describes a form of exploration of images that are difficult to “read”: “the ‘readability’ of these images – and thus their potential role in providing knowledge of the process in question – can only be constructed by making them resonate with, and showing their difference from, other sources, other images, and other testimonies.”9

Another productive method is what I would like to describe as ‘practice of unarchiving’, which decontextualizes and then recontextualizes archival footage to reveal and uncover specific ideological structures and personal traces left over from past times. This corresponds to a certain understanding of historiography that Steve F. Anderson describes thus: “According to this model, historians function as detectives engaged in solving a puzzle or uncovering and narrativizing a series of pre-existing facts.”10 The figure of the detective quickly brings to our attention the notion of trace and clues, and the special focus on details that unarchiving shares with forensic approaches and methods of image analysis.

To understand this notion more precisely, Carlo Ginzburg’s reflections on traces, clues and hints following Giovanni Morelli and Sigmund Freud can be specifically useful. At the end of the nineteenth century, Morelli pointed out the importance of details in the identification of works of art. An incidental and easily overlooked trace could say more about the artist than a significant gesture. This trace paradigm can also be found in Freudian psychoanalysis and characterizes the detective’s reading of clues.11 The overall impression is thus replaced by the detail. Similarly, Siegfried Kracauer, among others, has pointed out this as the revealing function of film, which is particularly expressed in the close-up.12

Hence, the specific practice of reading archive films can be derived from the interplay between the deciphering of details and traces described by Ginzburg and the affinities of film highlighted by Kracauer. Evelyn Kreutzer and Noga Stiassny describe the relation of trace (detail) and gaze (film) as “gaze-trace-entity”, from which a specific notion of “in-betweenness” arises:

Considering the fragmentary character of the visual heritage of the Holocaust, we propose to rethink the traces found in and constituted by archival footage from the Nazi era as part of a gaze-trace entity. This convergence of the ‘gaze-trace’ creates multiple in-between states.13

The diachronic analysis of the afterlife of archive footage is based on a phenomenon, which I have described elsewhere as “migrating images”.14 Based on Barbie Zelizer’s critical assumption that media help us to classify atrocities with reference to iconic images rather than to understand them15, I originally defined the concept of migrating images as a form of dissociation from their historical context that would use them as visual cues without fostering reflexive engagement with past events and their implications for our contemporary lives. I wrote:

historical images we derived from the Holocaust and its immediate aftermath are continuously dissociated from their historical origins. They are migrating into popular culture as emblematic images, hence my characterization of them as migrating images.16

This interpretation, however, overlooks the dynamic character of memory, which heavily depends on various forms of actualization that offer new ways of accessing the past and its afterlife. Astrid Erll has described this as “traveling memory”.17 When images migrate through other films, they leave a trace. With each new step they create new connections, which finally establish a complex visual net of image relations that demonstrates the impact of the visual memory of the Holocaust and provides new access points to engage with its visual heritage in critical and reflexive ways. This actually turns migrating archive footage into “living images” that continuously evolve and adapt to new contexts and interpretations.

Travelling with a Camera

Reinhard Wiener arrived in Liepaja in early July with the 707 Marine Flak Division.18 From day one, the unit was involved in the attack on the Soviet Union. Liepaja was of great strategic importance. A neuralgic port founded by Tsar Alexander III, it was also a significant trading hub, including companies owned by Jews fleeing poverty and pogroms in Eastern Europe. In 1935, just over 7,000 Jews lived in Liepaja.19 The majority of them were assimilated and integrated into the Latvian urban community. There were nine synagogues, three Jewish elementary schools, a grammar school, clubs and a Jewish library.

The port brought prosperity to the city's population, but also made Liepaja a rather proletarian city.20 Opposition to the Soviet rule was weaker here than in other places in Latvia. This was one of the reasons why Liepaja became the first obstacle for the German invasion designated as ‘Operation Barbarossa’. Berlin had expected to take the port and the city on the fly. On the evening of the first day of the attack, June 22, 1941, the 291 Infantry Division of the Wehrmacht was already in striking distance. What happened next can be seen as a harbinger of what awaited the Germans later in Moscow and other parts of the Soviet Union. The advance came to a standstill, and it took almost a week and nearly the complete destruction of the historic center before the Wehrmacht could take the city and the German navy could seize the port.21

Wiener’s unit arrived in Liepaja on July 10.22 Its task was to secure occupied Liepaja from air attacks with the help of four anti-aircraft batteries.23 Wiener filmed his everyday work with his private camera. The footage is today preserved in the collection of the Karl Höfkes Agency (AKH).24 Time and again, aircraft wrecks can be seen being inspected by members of the 707 Marine Flak Division. It is possible to identify some of the locations Wiener recorded in Liepaja. For example, he filmed the outside area of his unit’s office. It is very likely that he was employed there himself, as he stated in his interrogation that he had been assigned to the staff battery as head of the office.25 The corresponding shot shows a sign with the battery’s field post number, which Wiener also recalled during his interrogation.

Wiener explored the area like a tourist. He even ‘visited’ other places in Latvia. His private film footage includes shots from Riga, which show the impressive Freedom Monument that was erected in November 1935. Wiener also filmed the surroundings of his company’s accommodation. A slightly too bright film shot shows the Naval Cathedral Church of Saint Nicolas in the northern part of the city. It must have been close to the office of his unit, as fellow unit member Karl Beitzel recalled in his interrogation that the department staff was housed in a building between the cathedral and the coast.26

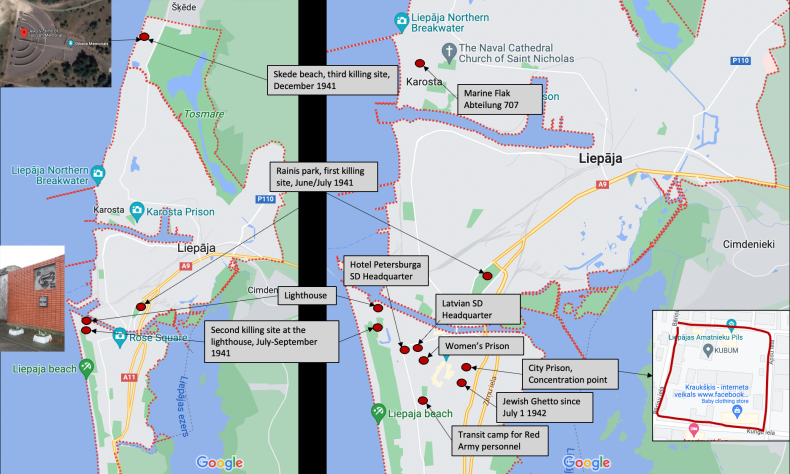

Wiener also moved around the city. Another scene from the footage shows the Holy Trinity Cathedral in the center of Liepaja. These shots must have been taken later, perhaps even in early 1942, when Wiener returned to Liepaja after a stay at home, a trip to Kiel and Königsberg and an accident in October 1941, after which he had to be treated in a military hospital for more than three months (Fig. 2).27 In the summer of 1941, the destruction caused by the German siege can still be seen everywhere. The sight of Jewish forced laborers also characterized everyday life in the city. On July 5, 1941, the city’s commandant, navy captain Brückner, issued an order that Jews had to work and were supposed to wear visible marks that identified them as Jewish. The order described these marks precisely as “recognizable yellow marking on the back and the chest that is not smaller than ten by ten cm.”28

The extent of Liepaja's destruction can also be guessed from the German newsreel Deutsche Wochenschau Nr. 566 from July 9, 1941.29 Before the report from Liepaja, which explicitly deals with the work of war correspondents and shows members of a propaganda company filming, a previous report from Lviv blames the Jewish population for the alleged crimes of Bolshevism. Corpses of dead civilians are displayed in order to arouse anti-Jewish feelings. This footage is followed by images of anti-Jewish riots. Citizens are publicly beaten up. After that, a sequence of close-up shots presents “Bolshevik types”. The voice-over emphasizes: “The majority of them are Jews.” Panning along stigmatized faces, the newsreel utilizes a typical antisemitic presentation mode, which also influences the perception of the final sequence from Liepaja and the Soviet cruelties emphasized by the voice-over. In doing so, the propagandistic report foreshadows how the German occupiers will treat the civilian population and in particular the Jewish citizens of Liepaja, who are identified as cause of the destruction and supporters of Bolshevism (Video 1).

Immediately after the occupation of Liepaja, German soldiers began carrying out random shootings of Jews and Latvians. On July 3 and 4, 1941, members of Einsatzgruppe 1a chose Rainis Park in the middle of the city, where there were already trenches dug by the Red Army for defending the city, which could be used as mass graves for the murder by bullets of several hundred residents.

The systematic shootings near the lighthouse, which Wiener recorded in his film, began in mid-July. In these killings, primarily Jewish men but also Latvians accused of resistance, disabled and mentally ill people as well as Roma were murdered by members of Einsatzgruppe 2 and a Latvian SD (security service) unit. The German SD oversaw the women's prison, where male Jews were detained before being taken to the execution site in small groups on trucks by Latvian helpers. In December 1941, several thousand Jewish women, children and men from Liepaja were murdered on Šķēde beach in the north of the city (Fig. 3). A series of photographs made by German SS photographer Karl-Emil Strott documented in detail the systematic mass killings that lasted for three days.30

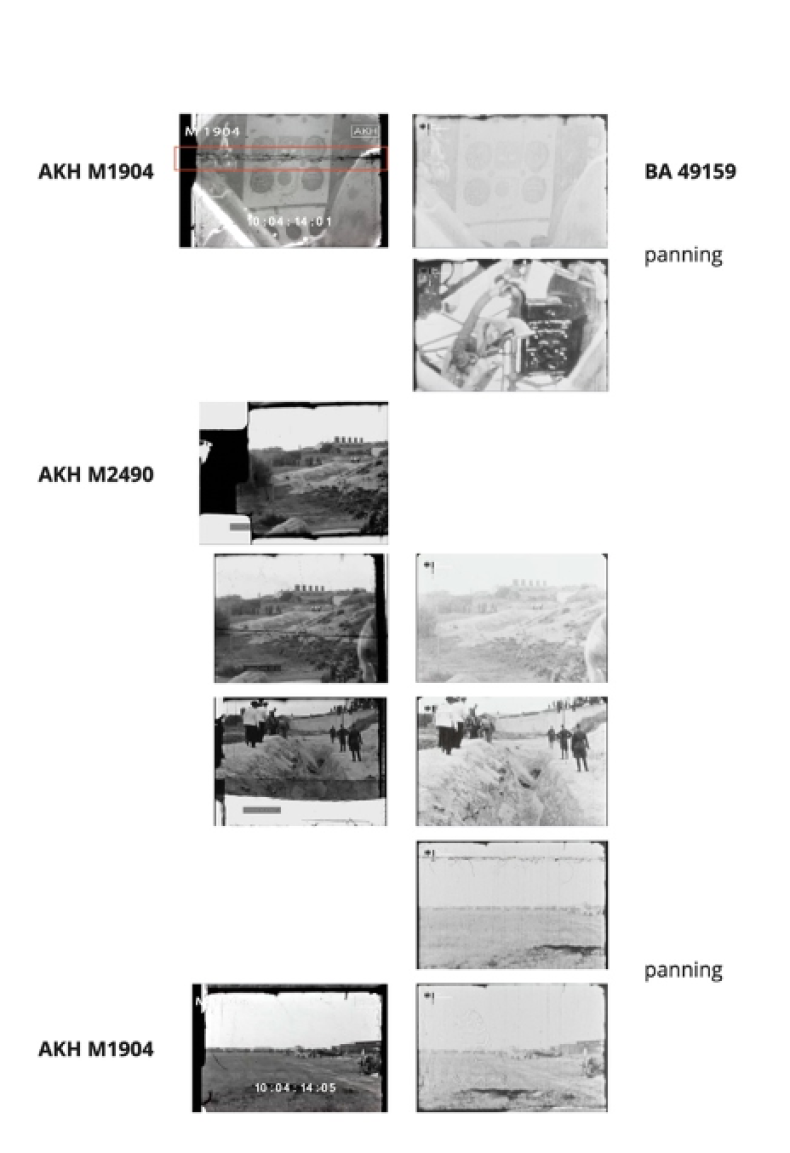

Layers of a Film

Wiener extracted, probably after the war, the sequence of the executions from his other ‘private’ film recordings depicting his life as a soldier in occupied Latvia. This is indicated by the version preserved in the German Federal Archives, which contains shots before and after the execution scenes showing downed airplanes being inspected by German marines. Identical shots can also be seen in his private film recordings from Liepaja and Riga, which are today part of the AKH collection. Visible edits in the digital copy of this film indicate that the film of the executions might have been later cut out from this film. In fact, the material preserved in the Federal Archives also contains frames that are no longer included in the original material (Fig. 4).

Extracting the execution scene from the material he filmed in Latvia was a first pre-selection by Wiener, indicating what he saw as important and what in his view seemed to be less important. Separating the historically ‘important’ documentation of the execution site from the ‘less important’ private shots also leads to him disappearing as a filmmaker behind his film. This retrospective self-positioning, an effect of detaching the film from its original ‘private’ context, allows Wiener to frame himself as a distant observer, contradicting the amateur attitude present in the other parts of his footage.

Hence, what can Wiener’s film fragment from the execution, this ominous “living document of the events in Libau”, itself actually tell us? Wiener’s first statement from October 1959 contains no indication as to whether he arrived at the execution site by chance or planned to visit it. He merely points out that word of the shootings had spread among members of the Wehrmacht, and that soldiers were able to visit extermination sites without permission.31 He also explains that he filmed without commission.32 In further interrogation during the preliminary investigation for the trial against Einsatzgruppe 2 in Hanover in November 1965, Wiener did not give any information about the reason for his presence at the execution site.33 Even in the indictment from the trial in Hanover, nothing can be read about this in Wiener's paraphrased statement.34 It was not until 1980, in an interview with the filmmaker and author Michael Kuball, that Wiener reported that he and another navy soldier, Karl Beitzel, had come along the killings by chance.35 He repeated this version during his visit to Israel a year later. In an interview with Herbert Rosenkranz, head of the archival division for investigating Nazi crimes in Yad Vashem and himself of Austrian origin, Wiener described the incident as follows:

And in Libau we went for a walk in the park between the town and the beach. And a soldier came running towards us there, we shouldn’t continue because it was awful, terrible further back on the beach. We asked him why. And he said ‘Well they’re killing Jews there.’ […] After the soldier had told us not to go there, I had decided to go there after all because I wanted to film it.36

Wiener is not the only one curious to see the executions. Other German soldiers from the navy, the Wehrmacht and the occupation administration populate the trench near the lighthouse as onlookers. It was dug by Jewish forced laborers. Survivor Moshe Leib Tscharny, a witness at the trial against members of Einsatzgruppe 2, told Israeli interrogators that he and other Jewish men were forced to dig a trench with a length of 25 meters, a width of 2.5 meters and a depth of 3 meters on the beach near the lighthouse. The next day, about half of the trench was filled with corpses and they had to cover them with earth and sand.37

Wiener carried his camera with him, as always.38 In Israel, Wiener described his enthusiasm for filming as follows:

[…] if I went for a walk or did something else and even when I used to be on board [of a navy ship], I usually had a film camera with me because something can happen suddenly which you can’t later put on film as a record.39

While he emphasizes the documentary recording value of the camera here, later in the conversation Wiener emphasizes the fragmentary character of his film. Back then, he used a Cine Kodak 8 mm with reversal film.40 This is the reason why he had to stop, set it down and wind it up again several times during the approximately 90-120 minutes he stayed at the site, filming a total of four executions. Correspondingly, excerpts from several shootings can be seen in the film.

From his very first interrogation, however, the technical limitations of his private camera also served Wiener as an opportunity to distance himself from the crimes he had witnessed while staying there for a relatively long time. In his first interrogation in October 1959, Wiener emphasized that the handling of the camera interrupted the depiction of the ongoing action several times. In doing so, he himself limits the evidential value of his film, which he had shortly before attested to be a “living document of the events in Liepaja.”41 In 1981, in his conversation with Rosenkranz in Israel, it finally seems that these technical limitations become a metaphor for Wiener’s personal defense. In order to remain the uninvolved spectator, a position which he had described to the interrogators in 1959 “as a film amateur, i.e. not as a person involved or commissioned”,42 Wiener now virtually disappears behind the film technology: “I would like to stress that I couldn’t observe what exactly was going on around me while I was filming, because I was looking through the lens and I could only see that section that I was looking at through the lens.” And regarding the technical limitations of the recording, which clearly affects the film’s status as a comprehensive document of the executions, he explains: “That means that my film does not show the action continuously[,] which took place[,] there are pieces missing in between.”43

Wiener's film footage of the executions, as preserved in the Federal Archives, is 1 minute and 42 seconds long. The total length of the digitized archive material available there is 2 minutes and 21 seconds.44 As explained above, it also contains fragments from Wiener’s other films from Liepaja. The original film from the family estate, digitized by AKH, is 1 minute and 30 seconds long.45 The historian Gerhard Paul mentions 1 minute and 20 seconds.46 Jean-Benoît Clerc identified 2 minutes and 14 seconds as the total length and counted 1 minute and 39 seconds for the part filmed at the execution site.47 Differing lengths may also be due to diverging digitization frame rates.

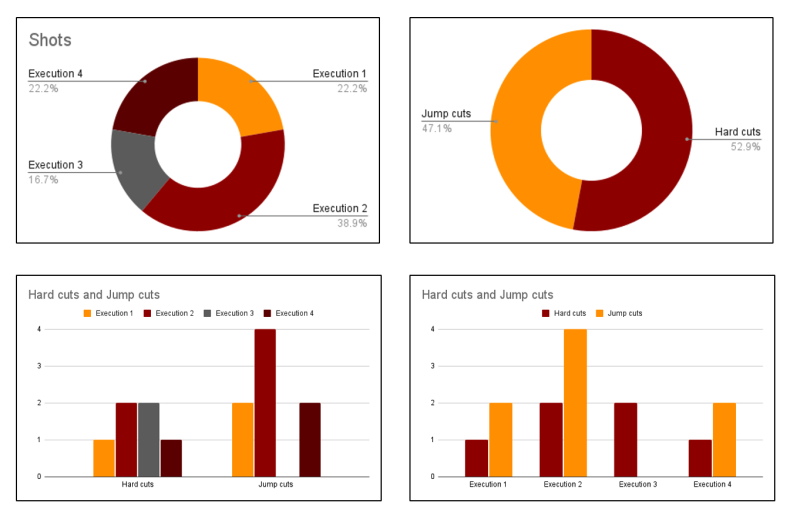

The analysis of the digitized film copy from the Federal Archives shows that the film consists of a total of 18 shots.48 The deviating number of 20 shots in the copy by AKH is due to the initially slightly offset scan of the first shot and the doubling of shot 6, which, as will be shown later, is a particularly significant film shot (Fig. 5). The number of 21 shots assumed by Paul could not be verified.49

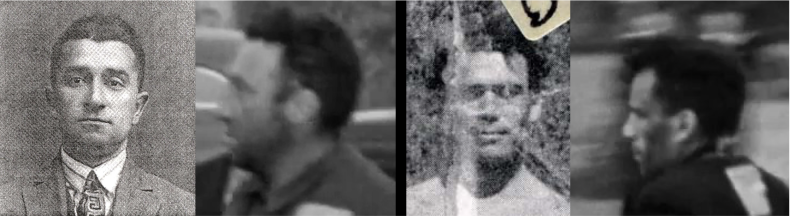

The footage contains depictions of four executions, even though Wiener, in his later conversation with Kuball, remembered only three.50 The first depicted execution comprises the first four shots of the film. Wiener later reported that initially he filmed from a “greater distance.”51 Accordingly, the first shot shows an overview of the area, equal to an establishing shot. We can clearly identify the trench, estimated to be 20 to 25 meters long and a building with five significant chimneys.52 Part of a head can be seen in the bottom right-hand corner of the picture. It might belong to Sergeant Major Karl Beitzel, who, according to Wiener, had accompanied him to the shooting site. The same head is seen much clearer in the next shot. Beitzel can be identified due to the slightly protruding ears and the haircut (Fig. 6). This and the following shots depict the first group of Jewish men pushed by local auxiliary police and Germans in uniform in the direction of the trench.

For shots 5 to 11 Wiener had changed position. They show the second execution. He later reported that he had become bolder and went in front of the spectators.53 This sequence contains the largest number of shots: seven. It depicts a truck with five men marked by the yellow patches on their clothes as Jews. They are guarded by Latvian auxiliary police men that can be identified through their white armbands. Clearly visible is also the truck driver, who is likewise wearing a white armband.

Between Wiener and the truck, soldiers watch as the men jump off. Paul identified the soldier in front of Wiener’s camera as an SS officer ranked Oberscharführer (senior squad leader).54 The following shot is filmed from the same position, although Wiener had turned left and is therefore depicting the group of Jewish men from a closer distance. They assist a man in a white coat who previously had difficulties climbing from the truck. In the background a soldier can be seen with his arms on his hips.

After turning left again, Wiener is then frontally facing the trench in a medium-long shot where the men are executed. The three shots indicate a 90-degree turn of the camera. The last five shots – all filmed from the same position facing the trench – constitute a nearly continuous sequence, only interrupted by jump cuts. Such jump cuts, which indicate that Wiener briefly stopped filming and then continued from the same position, are characteristic of the film and result from the technical limitations described above.

Of a total of 17 cuts in the whole film, 8 are jump cuts (47.1%). For the viewing experience, the constant presence of jump cuts has a destabilizing and disruptive effect. They contribute to the fragmentary character of the footage and undermine its documentary impression. The largest number of jump cuts, a total of four, can be identified in the sequence depicting the second execution. Like in the scenes depicting the first (2 jump cuts) and fourth (2 jump cuts) executions, they constitute two-thirds of the total number of cuts. Only the third execution sequence does not contain any jump cuts (Fig. 7).

This third sequence consists of only three shots. Filmed from the same position as the previous second execution sequence, Wiener first depicts the truck, most likely driven by the same Latvian driver and guarded by the same member of the Latvian auxiliary police as well as the German Oberscharführer. At the right side of the truck, Wiener depicts another German soldier. The second shot of this sequence shows the group of Jewish men, most of them wear the typical yellow patch, from a medium-close range. In the background, the German soldier who was standing at the right side of the truck in the previous shot directs them towards the trench. The Oberscharführer is now visible at the right edge of the frame. Most significantly in this shot is the movement of the camera. Shot 13 is one of two panning shots in Wiener’s film, his camera is following the five men towards the direction of the trench. It also captures a third soldier, who is obviously giving orders to the men.

Then Wiener adjusts the camera to the exact same medium-long shot position facing the trench. On the left side of shot 14, heads of onlookers are partially covering the frame. Another soldier stands between the spectators and the trench, while the killing squad on the left, largely covered by the heads of the onlookers, shoots the five men standing in the pit. The soldier stands in a striking pose, one leg slightly bent, with one hand resting on it and the other on his hip. This shot is also marked by a significant camera movement. After one second the camera trembles. Wiener most likely flinched at the sounds of the shootings while holding the camera in his hand and filming. He described this also to Kuball: “You might see in the film that it [the camera] is trembling.”55

The final execution scene opens with several men, most of them with yellow patches on their backs, running towards the trench. The camera starts recording while the men are already in motion, and it follows them with a slight panning shot, the second in the film. The bright flickering at the beginning of the shot indicates that the camera has not been in use for some time. It may also be the spot where the two parts of the reversal film were later glued together.56 The next shot indicates a jump cut. Obviously only a few seconds have passed. The Jewish men and their guards have moved closer to the trench. At the left, a German soldier with white epaulettes holds an unidentified item in his right hand. Between this and the next shot, Wiener must have moved with the group toward the trench. In the final two shots, both separated by jump cuts, he stands directly at the edge of the pit. In shot 17 a soldier is turning his head towards him and leaves the frame after the shooting. In the final shot, two men in white jackets approach the killing squad on the left-hand side of the frame.

Mapping Traces

The location of the shots can be verified with the help of the distinctive chimneys on the low building opposite the shooting site, which was used as a smokehouse for fish.57 Together with the lighthouse and the fortifications of the former citadel, they constitute prominent landmarks that can be identified in aerial photographs. Information about the crime scene near the lighthouse was already collected during the Central Office's investigations. German witnesses had drawn two maps that indicated the execution site. The crime scene can also be easily located on Google Maps.58 The fortification served as a protective elevation and a good vantage point for onlookers. The city’s sports stadium was also located nearby. Today there is a memorial to the murdered victims, while the former shooting site itself is enclosed by buildings (Fig. 8).

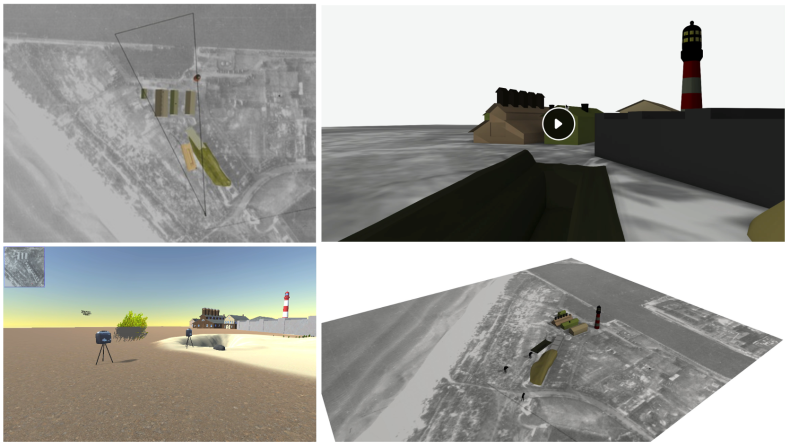

Based on historic maps and photographs, and with the help of technical information about Wiener’s camera and its lenses, Fabian Schmidt and Mikhail Chihichen created a comprehensive 3D model of the execution site that allows to locate it in relation to the significant landmarks depicted in the film (the lighthouse, the citadel and the smokehouse).59 Users can navigate the 3D model and review the different positions of Wiener’s camera. The virtually reconstructed buildings are embedded on a topographical map. A triangle visualizes the 23.9-degree angle of the Cine Kodak 8. An animated model of the execution scene allows us to explore each of the camera’s positions and measure the distance to the trench (Fig. 9).

In addition to topographical information such as the structures of the old citadel, Wiener's film also provides clues regarding the time of day, which correspond with some of the witness statements. We see lightly clad onlookers. Wiener remembers that “it was very hot and you could still bathe.”60 Some members of the navy protectively hold their hands over their eyes to see better. This indicates that the sun is facing them and that it is still relatively high. The shadows also indicate that Wiener filmed late during a day in summer. Indeed, the executions usually took place either in the early hours of the morning or in the evening.61

In the many interviews and statements, which Wiener made during his interrogations and when the interest in his film increased during the late 1970s, he never clearly indicated the date of his filming. Vaguely, he remembered the end of July or mid-August 1941 as possible points in time. In any case, he recorded his film during his first stay in Liepaja, which means between his arrival on July 9 and his vacation, which started on September 27.62

Based on the diary of German soldier Karl Heinz L., who described an execution that bears many parallels to Wiener’s film (the location, the summertime, the evening hours and even mention of a man in a white coat like the one in shot 6), historians have dated the footage to July 15.63 Clerc was the first to reconstruct in detail the probable time of the filming based on almost all available documents from the archives as well as reports from survivors and diaries. His findings cast doubt on the previously assumed timing. Instead, he dated the execution depicted in Wiener's film to July 29, 1941, referring to the testimony of Klara Schwab, whose husband Arkady Jacob Aron Schwab was executed on that day after he had been abused in prison.64 He also refers to a diary entry by Kalman Linkimer, who reports on Schwab's mistreatment and mentions that he was wearing a white coat like the man in Wiener’s film.65 An old man in a white coat is also mentioned by Boatswain Walter Schulz, who witnessed an evening shooting in late July 1941 and even remembers a naval soldier with a camera.66 With the help of an internationally recognized expert in facial reconstruction and comparison, Clerc finally succeeded in identifying the man in the film recording “most likely” as Arkady Jacob Aron Schwab and consequently July 29, 1941, as the day of the shooting.67

Exploring the digitized versions of historical films allows to apply techniques of visual forensics and of cinematic inquiry such as slowing down the speed or pausing the moving images to closer inspect a specific frame and the objects within the frame, a technique Kreutzer and Stiassny described as “digital digging.”68 This allows focusing on specific details and inspect objects, details and scenes that appear blurred or are only visible on the fringe. This method makes it possible, for example, to clarify the contradictory statements about the trucks seen in shots 5 and 12 before the second and the third execution, in which the men were driven from the women’s prison to the execution site by Latvian volunteers. Witness accounts and reports differ as to whether these trucks were German or Latvian-made. The Jewish forced laborer Jehuda Goldberg, however, assumed that they were Soviet looted vehicles.69 The close inspection of the shots reveal that Goldberg was right and that the trucks used for transporting Jews were most likely Soviet GAZ-AA pick-up trucks, produced between 1932 and 1938.

Already noticed by previous researchers, a little dog suddenly enters the frame in shot 9.70 While the camera focuses on the second execution, the foreground turns choppy due to the hectic movements of the dog. Was the dog agitated by the noise made by the rifles? Why was it present at the execution scene in the first place? Did it belong to the Germans, a Latvian volunteer or a bystander? From a visual archeology lens, the little dog serves as an indicator of uncontrolled pre-filmic reality, a reminder of the particular contingent moment in which Wiener took his film. Simultaneously, it constitutes a symbolic motif that – when noticed – results in a moment of irritation, because it contrasts the hermetic and mechanical process of continuous killing that we witness in this film.

A closer look at individual shots also reveals details that trigger speculation about possible traces without producing clear clues. Such a detail can be found in shot 16. Is this uniformed German smoking a cigarette next to the execution site holding a camera? Was a second man filming that day? What can hardly be identified in this shot, might well be a small Bollex hand-held camera (Fig. 10). In that case, another film of the shooting possibly exists somewhere out there.

Digging for Details

How far can a private film made by a German soldier at an execution site where Jews are murdered in large numbers show the suffering of others, in this case that of specific Jewish men, fathers, husbands, citizens of Liepaja who were forcefully driven towards the firing squad? What contemporary audiences encounter in Wiener’s film are mostly grainy and blurred black-and-white images, which French filmmaker Claude Lanzmann, the director of the monumental documentary SHOAH (FR 1984), has once characterized as “only images”. Wiener’s film, Lanzmann critically stated, contains images “without any significance”. Although it depicts – in a technical sense – the moment of the killings, it is still unable to ‘show’ the mass murder because the film presents “images without imagination.”71

Indeed, as Wiener later claimed, his film only depicts a limited point of view, a random and even partly poorly framed section of the events when “looking through the lens.”72 While filming, Wiener claims that he only recognized parts of the cruel reality surrounding him. The atrocities thus became an object of the private filmmaker’s gaze hidden behind his camera viewfinder, emotionally distanced and mechanically recorded. Of course, the film depicts what happened, but its limited view corresponds to the retroactively self-proclaimed distance of Wiener’s position. Wiener’s self-distancing obscures his curiosity, maybe even his excitement or his anxiety during the filming. According to Wiener, only later, when the film was developed and screened for the first time, he himself would notice his own affective response inscribed as trembling into the footage.

In his Theory of Film, Kracauer evokes the myth of Medusa who is beheaded by Perseus confronting her horrible face as a mirror reflection in his shield, to describe the encounter with horrors in cinema. He emphasizes “that we do not, and cannot, see actual horrors because they paralyze us with blinding fear; and that we shall know what they look like only by watching images of them which reproduce their true appearance.”73 Was this the case when Wiener screened his film from Liepaja to fellow German soldiers?

Wiener stated during his visit to Israel that he had shown the film once during wartime to some of his comrades after he had left Liepaja for Schleswig-Holstein in February 1942.74 The clandestine screening at the submarine school in Neustadt may indeed have caused surprise, disbelief, even shock and disgust. Perhaps Wiener only realized after watching his own film that he had witnessed the shooting of innocent people for hours. But maybe approval or legitimization of the deeds could also be heard from the private circle. At the very least, it is unlikely that the screening had the memory-forming effect that Kracauer describes:

The mirror reflections of horror are an end in themselves. As such they beckon the spectator to take them in and thus incorporate into his memory the real face of things too dreadful to behold in reality. In experiencing the rows of calves’ heads or the litter of tortured human bodies in the films made of the Nazi concentration camps, we redeem horror from its invisibility behind the veils of panic and imagination. And this experience is liberating in as much as it removes a most powerful taboo.75

Finally, Wiener’s film was tabooed, buried, hidden, and then concealed from the public after the end of the war. In retrospect, Wiener cited fear of punishment by the military or Nazi judiciary. But perhaps it was more the fear of the images themselves that led to their ‘mummification’. Viewing the projected images of atrocities does not necessarily imply that the audience also really ‘sees’ the suffering of others, who are depicted in the footage.

Hence, while watching these images, what do we actually see? The mute, distant, and blurred images imply the necessity to relate them with additional knowledge, to give them a ‘voice’. Hence, these images need to be attached to other documents, testimonies and/or voices of witnesses. This points to the technique of appropriation. But the term appropriation refers to two different meanings: to property, the ownership of the footage, and the ownership of the experiences (and memories) that are related to these images. And it refers to what is appropriate; to the way how to use these images, how to interrelate them with other materials that will enable us to realize the suffering of those who are depicted on film and were killed shortly after their last traces were preserved on the footage.

The technical transformation from filming to screening, from looking through the lens to inspecting the screen marks an important precondition for sensing the suffering of others within the prosthetic arrangement of a cinematic environment, as could be seen when the Jerusalem courtroom turned into a screening hall during the trial against Adolf Eichmann, and Wiener’s film was projected as visible evidence. This transformative aspect of enlarging the frame from the limited scope of “looking through the lens” to projecting the footage on the large screen, is also indicated by Wiener’s own description of the first private screening of his film: “when they saw it for themselves in the film, then they believed me and what I had said”. He also described the reaction of his ‘audience’: “They were depressed. […] I was observing their faces and saw how shocked they were, we had never seen or found out about anything like it in the Navy nor had we experienced anything like that.”76

Enlarged on the screen, human actors become visible, even particular faces – of the perpetrators as well as of the victims – can be traced. One particular moment, when Wiener’s panning camera follows a group of men running towards the pit, attracts special attention. Here we can see the frightened faces of the men and witness the process of humiliation from a closer perspective.

Most important, however, is the imprint of those lives that were depicted in Wiener’s film in their last moments, traces of people who were forced to the site in order to get killed, for no rational reason, and without any other purpose than total annihilation. Working with a digitized copy of the film allows us to turn it into a series of single frames that enable us to closely review the details preserved in the pictures, in particular human faces, even if Wiener’s camera had only depicted them in passing, without really noticing them (Fig. 11).

Encountering the faces of the men that are forcefully driven to their execution, allows establishing an ethical relation to the unknown people captured by Wiener’s camera. Bob Plant summarizes that according to French philosopher Emanuel Levinas,

[e]ncountering the other’s face is ‘straightaway ethical’ in the sense that my responsibility does not hinge on some prior knowledge of (for example) her ‘character’ or ‘social position.’ For Levinas, responsibility comes immediately from the other’s ‘nudity as the needy one . . . inscribed upon his face.’ That is to say, it is the inherent ‘destitution’ of the face that ‘assigns me as responsible’. What interests Levinas here is what it means to be faced by another concrete human being before any explicit communication or recognition takes place.”77

In this sense, watching Wiener's film is about a shift in perspective, from the manifestation of the event (the systematic mass murder) to the last traces of the persecuted and abused people who were immortalized here in a blurred and impassive form. To do this, the moving images of the film must be stopped in order to enlarge the faces, cut them out of the continuum and look at them. It is only through this process of looking, in which a relationship is established between the viewer and those casually gazed upon, and which happens without any previous knowledge, that they are transformed from abstract victims into concrete people.

In the next step, we can use those enlarged parts of the single frames to compare the people recognized in the footage with other visual evidence such as private photographs from before the war. Furthermore, the shots can be annotated with additional information such as testimonies, interrogation reports, diaries and other sources that might help to reveal the identity of those depicted in the film shortly before they were killed in cold blood.

As noted above, Clerc has “most likely” identified Arcadi Jacob Aron Schwab as the man in the white coat, depicted in shot 6. In his interrogation, Konrad Pohlenk speaks of a Jewish worker named “Westermann” who no longer showed up for work at the end of July.78 He was probably arrested and murdered, perhaps on the same day Wiener was filming. The Israeli Holocaust memorial Yad Vashem preserved a Page of Testimony of Leib Westerman, which also contains a photo (Fig. 12). This could possibly be another man from the second group depicted in shot 6.79

In shot 13, Wiener films a young man running towards the pit. Presumably, this is Boris Kremer from Liepaja who most likely was shot near the lighthouse at the end of July.80 Although we cannot be sure whether those men in Wiener’s film are identical with the men that were uprooted from their families and friends and brutally murdered in the sands of Liepaja, each story, each biography studied and reconstructed in context of searching for traces in the footage is another attempt to unpack the personal memory of the Holocaust.

A Migrating Film

In 1965, Wiener’s film was mentioned for the first time in the correspondence between the German Federal Archives and Reinhard Wiener. Wiener wrote that he owned an “amateur film about executions of Jews” under the subject line “Amateur films; here the execution of Jews in Libau in 1941” and provided precise technical details of the recording and the copy.81 Labeling the film as “amateur” already offers a certain interpretative framework for understanding its subject. Distracting from Wiener’s position as a member of the German armed forces and from the privileged access he had to the execution site, distances him from his film and the crimes it depicts.

The contact between Wiener and the Federal Archives had already existed for several years. In January 1961, the Archives approached the passionate private filmmaker for the first time. They had learned that he was “in possession of self-recorded documentary films from the time of the last war.”82 Wiener sent a detailed list of the footage he had shot during his time as a navy soldier. However, the film from Liepaja, as well as his private footage from Latvia, was missing from the list, although it was just beginning to become known to a wider public at the very same point in time.83

The film, which later was given the archive title “Execution of Jews in Libau in 1941”, was shown publicly for the very first time as part of the television movie AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS (DE 1961). German television had produced this documentary by director Peter Schier-Gribowsky on occasion of the Eichmann Trial in Jerusalem.84 Following a sequence showing the departing train from the Dutch transit camp in Westerbork,85 Wiener’s film was shown in full length and uncut. This first use is a rare complete reproduction of Wiener’s original version.

Schier-Gribowsky knew about the background of the film. The voice over refers very precisely to the actual context by explaining that the film was shot by a German soldier with a 8 mm camera during an execution in the East and is now being shown publicly for the first time. Clerc managed to reconstruct how the film ended up in Schier-Gribowsky’s documentary.86 By this time, Wiener had already made his film available for criminal investigations by West-German authorities. In March 1961, he was contacted by the television station who asked permission to use the material for the documentary about Eichmann. Wiener then consulted with the public prosecutor’s office in Hanover to agree to the broadcast. As we know, his film eventually became part of the film about Eichmann.

Shortly after, Wiener’s film was presented in court during the trial against Eichmann as part of a collection of films screened in the court room as evidence.87 As I explained elsewhere, the court records clearly reference AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS as the source for the film sequence screened in Jerusalem. In his request to the court to introduce films as evidence, Israeli Attorney General Hausner explicitly referred to material about the organization of the Einsatzgruppen and the minutes give the translation of the documentary’s original German title as “In the Steps of the Hangman”.88

But how did Hausner come into possession of Schier-Gribowsky’s film? It is possible to answer this question based on documents from the archives of the German Foreign Office, which include internal reports by the West German journalist Rolf Vogel. Officially accredited as a correspondent for the Deutsche Zeitung (later Handelsblatt) at the trial, Vogel was entrusted with keeping an eye on the possible repercussions of the trial in Jerusalem for the government in Bonn.89 One particularly sensitive point was Chancellery Minister Hans Globke, a close confidant of Chancellor Adenauer. The German government was anxious to assure that Globke’s controversial Nazi past was not to be discussed in Jerusalem. Vogel was therefore particularly interested in the activities of Schier-Gribowsky, because one sequence of AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS critically focuses on Globke and his role as lawyer in the Nazi regime.

Schier-Gribowsky had traveled to Israel to report on the Eichmann trial. Together with Joachim Besser, he covered the events in a documentary series called EINE EPOCHE VOR GERICHT (DE 1961). The episodes were mainly based on the video coverage of the trial, which was filmed by director Leo Hurwitz and his team for the Capital Cities Broadcasting Corporation.90 Vogel’s reports reveal that Schier-Gribowsky had taken a copy of AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS with him to Jerusalem. His intention was to show the film to the Israeli judges and prosecutors. However, he encountered unforeseen difficulties, as there was no film projector in Jerusalem that could play the separate sound and film reels.91 Finally, with the help of Capital Cities, he managed to find a suitable projector. The screening could take place.92 Hausner must have seen Wiener’s film there as part of Schier-Gribowsky’s documentary and decided to include it in the collection of film material that was finally shown on June 8, 1961, to the court (Video 3).

The video shows that Wiener's film was shortened by four shots and edited together with photographs of different executions, including one from the execution site in Šķēde. The film recording of a special session that had taken place the evening before, on June 7, 1961, for the defendant Eichmann and his counsel, makes it clear, however, that the material was certainly taken from Schier-Gribowsky’s film. The length and sequence of shots are identical. The screened sequence even contained the preceding shots from the Westerbork film and a succeeding shot showing a document from the ‘Topf und Söhne’ company (Erfurt), constructors of the crematoria, like in Schier-Gribowsky’s montage.93 Only a few shots of Eichmann were added to the material shown in Jerusalem (Fig. 13).

At this time, Wiener and his film were already well known to insiders, namely the investigators of the Central Office of the State Justice Administrations for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes in Ludwigsburg, which had been set up in 1958 because of the Ulm Einsatzgruppen trial. He was questioned for the first time in the fall of 1959.94 Shortly afterwards, he must have handed over the film to the investigators. It is not yet clear from the files whether Wiener approached the Central Office on his own initiative or was somehow tracked down by them. Wiener later reported that the trial in Ulm had prompted him to tell a neighbor, himself a public prosecutor, about the recordings for the first time.95 But his contacts in the Baden-Württemberg Ministry of the Interior could also have made the connection to Ludwigsburg possible.

During the interrogation, Wiener wrote down a detailed statement in which he described the situation of the filming. In it, he offers his own version of interpreting his film as a “living document of events in Libau”, from which he repeatedly distanced himself – also on behalf of his comrades. Allegedly, his film was intended to bear witness so that those responsible would be requested to comment on “their actions”, while he disappears behind his film as a “film amateur”, neither involved nor commissioned. While his film as a “living document” is supposed to call those responsible to account, the witness Wiener neither recognizes people nor remembers names of those depicted in the footage and on photographs presented to him.96

If we want to understand the term “living document” not only in the banal sense that Wiener's film, like every film, is a moving image recording and thus a series of “living images”, then we should try to take its ambivalence seriously. As agents, the film’s images conceal and reveal in equal measure. They reproduce on the one hand the attitude of the operator,97 who probably lingers at a shooting site for more than 90 minutes without hesitation or disgust, and on the other hand they preserve the traces inscribed on the 8-millimeter footage. The document comes to life through its interpretation, classification, expansion and interrelation with additional sources and information, processes that characterize both the examination of the historical film footage and its continued life, in particular its migration into other contexts, films and media, in this case as evidence in a criminal investigation.

Wiener's film was first used in 1959 as part of the ongoing investigation into the crimes committed by the German Einsatzgruppen in Liepaja. On that occasion, it was transformed into a series of seventeen still images, assembled and newly appropriated in a photo album and provided with short descriptions.98

A closer inspection of the album reveals a process of decontextualization through reappropriation. The first and last picture in the album were taken from the opening shots of the film when Wiener was filming the trench from a greater distance. The new arrangement thereby characterizes the filmmaker as an uninvolved spectator, although Wiener and his camera actually moved closer and closer to the execution scene until he stopped just a few centimeters away from the trench. Contrary to what Wiener himself had stated to the investigators,99 the information provided on the album’s first page frames his film as commissioned work, which assumes a resistant intention: “The witness was instructed by his superior, the port commander of Libau, to record on film the days-long shootings of Jews by the Einsatzgruppen, after the port commander had failed to prevent the shootings.”100

The captions emphasize distance from the actions depicted in the pictures. The first two stills only provide generalizing information about the perpetrators who are characterized as rather passive (“A member of the killing squad shows them [the victims] the way”101), while the Latvian involvement, in contrast, is particularly emphasized (“The Latvian security service [white armband] prevents escape attempts”102). Similarly, the caption on page 5 explicitly indicates a Latvian “guard”, while the SD members are merely “standing by the truck”.103 Other captions tend to affirm the atrocities depicted in the pictures by reinforcing the coercion and violence against the victims through quite ambivalent textual additions rather than critically examining them. One caption under the blurred shot of two running men reads: “Running to the shooting trench”104; and under the photo of an execution an investigator just wrote the brief affirmative sentence: “Salvo”.105

The last photograph on page 18 particularly reinforces the distancing and resistant narrative intended by the rearrangement of the stills. Below the long shot of the shooting site the caption reads:

The witness Wiener has fulfilled the order of his commander. For later times it is recorded in the film that it was not the Germans, but individual specially selected Germans who carried out the extermination operations, against whose rage the port commander of Libau turned in vain.106

The film is given the status of a “document” intended for recording the crimes “for later times”. At the same time, the album exonerates the German involvement in the executions by framing the participants as individual perpetrators. Finally, the filming is once again interpreted as an act of resistance. In this version, however, the actual resistance does not come from Wiener, who operated the camera, but from his superior, the port commander. This narrative is factually countered by the fact that both the fortress commander and the local commander of Liepaja, both members of the navy, were actively involved in the shootings of Jews in July 1941. Heinz-Ludger Borgert writes about the role of the navy in Liepaja:

On July 7, the SD sub-commando Grauel carried out the hostage shootings that the fortress commander had demanded in an excessive manner. On July 8, 1941, the local commander increased the number of hostages to be shot in reprisal to 100 per wounded German soldier. Three days later, it was even set at an unspecified number, i.e., a number yet to be determined.107

Other than the first utilization of the film in the investigators’ photo album, the editing and the rearrangement of the shots in early usages of Wiener’s film indicate that some, specifically Jewish filmmakers obviously intended a shift in perspective towards the recognition of the victims. Already in the first use of the sequence following AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS, it is noticeable that the order of the shots was significantly altered, and thus new meanings generated. In his film EICHMANN UND DAS DRITTE REICH (CH/DE 1961), Erwin Leiser dispenses with the first, rather distanced establishing shots and opens the sequence with shot 3 (which he later even repeats).108 This shot shows from an elevated position how the first group is driven to the trench. He then cuts to a frontal view of it (shots 7 and 9), and then to a semi-close-up shot of the truck with the third group (shot 12) and to the subsequent close-up of one of the victims (shot 13). In this way, Leiser breaks up the continuity of Wiener's shots and, after establishing the situation, already places an accent on the murdered victims (Fig. 14).

The Israeli documentary film THE 81ST BLOW (IL 1974) by Jacques Ehrlich, David Bergman and Haim Gouri shifts the focus even further. The sequence with Wiener’s footage begins with the third group (shot 12) and then shows the opening shot of the truck with the first group as used by Leiser (shot 3), but immediately adds the close-up of the man from the third group (shot 13). The focus on the victims is thus further intensified here, which corresponds to the general direction of THE 81ST BLOW, a film composed of historical footage and accounts of survivors that are added to it as voice-over commentary.109 Only then follow shots of the second execution (shots 7 and 9), in which the perpetrators can only be seen from a distance. After that, Ehrlich, Bergman and Gouri show the close-ups of the second group (shots 5 and 6), again shifting attention to the human dimension of the crimes. The sequence ends with shots 2, 16, 17 and 18 showing the actions and mistreatment by the Germans and the Latvian volunteers.

When the 1978 US television series HOLOCAUST (US 1978) augmented the fictional story of the Jewish Weiss family and the German Nazi careerist Dorf with Wiener’s film footage, director Marvin Chomsky decided to begin the sequence with shot 13, the close-up of the men from the third group, before cutting to the overview shot (shot 3) and then to the semi-close-up shot of the second group (shot 5). With what is probably the most popular use of Wiener’s film, the mini-series, which significantly contributed to shifting attention and empathy towards the Jewish victims, not only in Germany, thus establishes a new arrangement of the shots from Wiener’s film, making the degraded victims visible.110

In these and other films – documentary and fiction alike – the film about the atrocities in Liepaja ‘lives on’ less as a “living document” as proposed by Wiener than as a living, migrating entity that changes its status and character and is continually used and reinterpreted in new ways.

Conclusion: A Film Comes to Life

Three dates are crucial when thinking of Wiener’s film from Liepaja as a “living document”. Although he filmed the roughly 90 seconds long sequence containing 18 shots depicting four executions of a total of approximately 19 to 20 male Jewish citizens from the Latvian costal city on July 29, 1941, and clandestinely screened his film in 1942 to fellow naval soldiers in Northern Germany, it is in 1959, through the investigations of the Central Office in Ludwigsburg, that his film first ‘comes to life’. Transformed into a newly arranged series of 17 still images, Wiener’s film was reframed in such a way that it could minimize German responsibility for the crimes against Jewish civilians and establish a resistant narrative of documenting the crimes of the Einsatzgruppen for future investigations. Nevertheless, as part of the investigators’ records, the film and the photo album indeed became pieces of evidence, at first used for the purpose of identification during interrogations before being officially filed as visual evidence in the trial against the members of Einsatzgruppe 2 in Hanover.

However, it was not before 1961, that Wiener’s film actually began to migrate. Fostered by the Eichmann trial in Jerusalem, at that point public interest increased in the film. The Zurich-based Praesens Film, which at that time was producing Erwin Leiser's EICHMANN UND DAS DRITTE REICH, contacted Wiener via the Hessian Attorney General Fritz Bauer.111 Wiener indeed must have shown the film to Bauer, because later, in his negotiations with the Federal Archives, he mentions that Bauer assured the uniqueness of the footage as “no similar film recordings exist”.112 Finally, the footage became part of Leiser's film and was highlighted in numerous reviews.113

However, when Praesens Film approached Wiener, he had already agreed to the inclusion of his footage in AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS, from which Israel’s General State Attorney took the sequence for a screening as part of the trial in Jerusalem. Thereby, the Eichmann trial became a particular aggregator for the film’s transnational migration and appropriation into different cinematic and commemorative cultures.

From this moment on, Wiener's film began its own ‘life’: as a source for migrating images, the film also carried the conscious and unconscious transmission of the memories of the crimes, their victims and the perpetrators that ‘traveled’ through it. A culmination of these traveling memories was perhaps the use of the footage in the miniseries HOLOCAUST, when the film became a globally disseminated document of the Holocaust. A few days after the controversial broadcast of the series on German television, which is regarded as a turning point in the Federal Republic's culture of remembrance, Wiener sent the Federal Archives some written explanations about his film. In his reply, an employee at the archive explained: “Our academic and journalistic visitors are constantly asking for film material on the subject of the persecution of the Jews.”114 Wiener’s ‘explanations’ reproduce almost verbatim his very first written submission to the Central Office in Ludwigsburg from 1959. The phrase “living document” also appears again, now supplemented by the successful use of the film at the trial in Hanover.

To speak of this film as a “living document” sounds sarcastic. To start with, this footage is a document of destruction, of death. Nothing is alive in the face of the routinely carried out and curiously observed mass murder. So, is it only the moving images that make this film ‘alive’, the ability of film to capture a moment in time that has long passed, to give those filmed a presence that they no longer had shortly after the moment of filming?

This footage ‘lives’ because it can establish new encounters and new relationships with perspectives other than those inscribed in them. As migrating images, the footage acquires its own agency, which makes it an agent that can also testify against itself and its own origin. This is why the film has achieved such a close and recurring relationship with criminal prosecution procedures and approaches to visual forensics, has been used as evidence in investigations and court proceedings and has repeatedly provoked changes of perspective, additions, appropriations, interrogations and historical imaginings.

- 1

Judenexekution in Libau 1941, Reinhard Wiener, DE 1941. See: BA 49159, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/3419/688817. See also: AKH Material Nr. 2490, https://archiv-akh.de/filme/2490#1.

- 2

Reinhard Wiener to Bundesarchiv Koblenz, Re: “Judenexekution Libau 1941”, 6.2.1979, BA Accession Files, AZ 5262/Wiener.

- 3

Reinhard Wiener, “Judenexekution Libau 1941: Erläuterungen zum Amateurfilmstreifen von Reinhard Wiener,” 6.2.1979, BA Accession Files, AZ 5262/Wiener.

- 4

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Trophy, evidence, document: appropriating an archive film from Liepaja, 1941,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 36, no. 4 (2016): 509-528, DOI: 10.1080/01439685.2016.1157286.

- 5

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Archives for the Future: Thomas Heise’s Visual Archeology,” Imaginations 8, no. 1 (2017): 74, DOI: 10.17742/IMAGE.GDR.8-1.5.

- 6

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Three Dimensions of Archive Footage: Researching Archive Films from the Holocaust,” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe 2-3 (2016), DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17892/app.2016.0003.51.

- 7

Jean-Benoît Clerc. Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds: Une exécution de Juifs filmée en 1941 et son usage dans les documentaires d’histoire (Neuchâtel: Éditions Livero-Alphil, 2023), 24.

- 8

See for instance Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Noga Stiassny, and Fabian Schmidt, “The Auschwitz Tattoo in Visual Memory. Mapping Multilayered Relations of a Migrating Image,” Research in Film and History. Video Essays (2022), https://film-history.org/node/1129, DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/19713.

- 9

Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz, (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2008), 120.

- 10

Steve F. Anderson, Technologies of History: Visual Media and the Eccentricity of the Past (Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press, 2011), 71.

- 11

Carlo Ginzburg, “Morelli, Freud and Sherlock Holmes: Clues and Scientific Method,” History Workshop 9 (1980): 8.

- 12

Siegfried Kracauer, Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 46.

- 13

Evelyn Kreutzer and Noga Stiassny, “Digital Digging: Traces, Gazes, and the Archival In-Between,” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces, no. 4 (February 2022): 1–13, DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18100.

- 14

Tobias Ebbrecht, “Migrating Images: Iconic Images of the Holocaust and the Representation of War,” Shofar 28, no. 4 (2010): 86–103.

- 15

Barbie Zelizer, Remembering to Forget: Holocaust Memory through the Camera’s Eye (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1998), 204.

- 16

Ebbrecht, “Migrating Images,” 90.

- 17

Astrid Erll, “Travelling Memory,” Parallax 17, no. 4 (2011): 4-18, DOI: 10.1080/13534645.2011.605570.

- 18

Reinhard Wiener, “Militärischer Lebenslauf (Kurzfassung),” BA (Ludwigsburg) B 162/2621, 69.

- 19

Andrew Ezergailis, The Holocaust in Latvia 1941-1944: The Missing Center (Riga: Historical Institute of Latvia, 1996), 273.

- 20

Ezergailis, The Holocaust in Latvia, 271.

- 21

Ezergailis, The Holocaust in Latvia, 271.

- 22

Wiener, “Militärischer Lebenslauf,” 71.

- 23

Landeskriminalamt Baden-Württemberg Sonderkommission “Zentrale Stelle,” “Vernehmungsniederschrift [Karl Beitzel],” 20.7.1959, BA (Ludwigsburg) B 162/2620, 118. See also Wiener’s recollection of four anti-aircraft batteries in Liepaja in his interrogation: Zentrale Stelle, [Vernehmungsprotokoll], 77.

- 24

AKH Material Nr 1904.

- 25

Zentrale Stelle der Landesjustizverwaltungen, [Vernehmungsprotokoll Reinhard Wiener], 16.10.1959, BA (Ludwigsburg) B 162/2621, 77.

- 26

Landeskriminalamt, “Vernehmungsniederschrift,” 118.

- 27

Wiener, “Militärischer Lebenslauf,” 69.

- 28

Ezergailis, The Holocaust in Latvia, 272.

- 29

Deutsche Wochenschau Nr. 566, 9.7.1941, https://archive.org/details/1941-07-09-Die-Deutsche-Wochenschau-566.

- 30

Valerie Hébert, ed., Framing the Holocaust: Photographs of a Mass Shooting in Latvia, 1941 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2023).

- 31

Reinhard Wiener, “Schriftliche Äußerung des Zeugen Wiener,” 4.10.1959, BA (Ludwigsburg) B 162/2621, 73.

- 32

Wiener, “Schriftliche Äußerung,” 75.

- 33

Landgericht Hannover, [Vernehmungsprotokoll Reinhard Wiener], 3.11.1965, BA (Ludwigsburg) B 162/2630, 59.

- 34

Staatsanwaltschaft beim Landgericht Hannover, “Anklageschrift,” 18.1.1968, in Documentation about Trials and War Criminals, Yad Vashem Archives O.4 File 369, 90-91.

- 35

Michael Kuball, Familienkino: Geschichte des Amateurfilms in Deutschland. Band 2: 1931-1960 (Reinbek b. Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1980), 115.

- 36

Yad Vashem, “Mr. Wiener’s Interview RE Libau: Transcription of a video tape concerning the shooting of Jews in Liepaja/Libau, Latvia,” http://data.ushmm.org/intermedia/film_video/spielberg_archive/transcrip…, 7.

- 37

Staatsanwaltschaft, “Anklageschrift,” 43.

- 38

Kuball, Familienkino, 116.

- 39

Yad Vashem, “Mr. Wiener’s Interview,” 7.

- 40

Wiener, “Judenexekution Libau 1941.” The description of the technical details in the statement for the Federal Archives of 1979 are almost identical to the wording in his written statement of October 1959. Wiener also refers to the camera model in the interview with Kuball and in the conversation with Rosenkranz in Israel.

- 41

Wiener, “Schriftliche Äußerung,” 75.

- 42

Wiener, “Schriftliche Äußerung,” 75.

- 43

Yad Vashem, “Mr. Wiener’s Interview,” 11. Wiener describes his position in a similar way in the interview with Kuball, when he explains that when filming, you only observe the scene that you have targeted in the camera's viewfinder. He did not care at that moment. He was simply filming. Interestingly, however, Wiener links the disappearance of his subjective decision-making ability behind the camera apparatus with the suggestion of potential persecution and explains that he could have been arrested anytime while filming. When questioned, however, he emphasizes that he was not hiding. Kuball, Familienkino, 116-117.

- 44

Judenexekution in Libau 1941, BA 49159 (File), https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/3419/688817.

- 45

Lettland – Libau – Erschießung von Juden durch Einsatzgruppen, Material Nr. 2490 (Original), https://archiv-akh.de/filme/2490#1

- 46

Gerhard Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur: Zur Visual History des ‘Dritten Reiches’ (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2020), 305.

- 47

Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 29.

- 48

Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 29.

- 49

Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur, 308.

- 50

Kuball. Familienkino, 116. Paul also repeats the assumption that three shootings can be seen. Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur, 307.

- 51

Kuball, Familienkino, 116.

- 52

Paul estimates the length at 20 meters. Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur, 307. As described above, the witness Moshe Leib Tscharny remembers the order to dig pits with a length of 25 meters.

- 53

Kuball, Familienkino, 116.

- 54

Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur, 305.

- 55

Kuball, Familienkino, 117.

- 56

For the technology used and the specific requirements, see: Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 28.

- 57

To determine the filming location, Clerc also used stills from the film, testimony, photographs and official maps and sketches drawn by German soldiers and Soviet investigators. His book contains a detailed description of the available sources. His reconstruction comes to the same conclusions about the place where Wiener filmed. Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 416-440.

- 58

The great research efforts by Efrat Komisar, using Wiener’s film, additional visual evidence and digital mapping services, made locating the actual killing site possible.

- 59

Schmidt, Fabian, and Alexander Oliver Zöller., “Atrocity Film,” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe 12 (March 2021), https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2021.00012.223.

- 60

Landgericht Hannover, [Vernehmungsprotokoll].

- 61

Zentrale Stelle der Landesjustizverwaltungen, [Vernehmungsprotokoll Konrad Pohlenk], 30.10.1959, BA (Ludwigsburg) B 162/2621, 108.

- 62

Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 441.

- 63

Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur, 310. Margers Vestermanis mentions the diary entry in his reconstruction of the mass killings in Liepaja as the only existing “documentation of an execution”. Margers Vestermanis, “Ortskommandantur Libau: Zwei Monate deutscher Besatzung im Sommer 1941,” in Vernichtungskrieg: Verbrechen der Wehrmacht 1941-1944, ed. Hannes Heer and Klaus Naumann (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 1995), 253. Beate Kundrus relates the date of L.’s diary entry then to Wiener’s film. Beate Kundrus, “Dieser Krieg ist der große Rassenkrieg”: Krieg und Holocaust in Europa (München: C.H. Beck, 2018), 197.

- 64

Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 512.

- 65

Edward Anders, ed., 19 Months in a Cellar: How 11 Jews Eluded Hitler’s Henchmen. The Holocaust Diary of Kalman Linkimer 1941-1945 (Burlingame, CA, 2014), 18-19. See also: Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 505-506.

- 66

Landgericht Hannover, Voruntersuchungssache gegen Rosenstock u.a. Befragung Walter Schulz, 13.12.1965, BArch B 162/2630, 86. See also: Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 498.

- 67

Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 511.

- 68

Kreutzer and Stiassny, “Digital Digging”.

- 69

Staatsanwaltschaft beim Landgericht Hannover, “Anklageschrift,” 42.

- 70

David Clark, “‘Not ours, this death, to take into our bones’: The Postanimal after the Posthuman,” World Picture 7 (Autumn 2012), http://worldpicturejournal.com/article/not-ours-this-death-to-take-into-our-bones-the-postanimal-after-the-posthuman/. See also: Kreutzer and Stiassny, “Digital Digging”.

- 71

Claude Lanzmann, “Der Ort und das Wort: Über Shoah,” in “Niemand zeugt für den Zeugen“: Erinnerungskultur und historische Verantwortung nach der Shoah, ed. Ulrich Baer (Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp, 2000), 107.

- 72

Yad Vashem, “Mr. Wiener’s Interview,” 11. See also endnote 59.

- 73

Kracauer, Theory of Film, 305.

- 74

Yad Vashem, “Mr. Wiener’s Interview,” 17.

- 75

Kracauer, Theory of Film, 306.

- 76

Yad Vashem, “Mr. Wiener’s Interview,” 17.

- 77

Bob Plant, “Levinas and the Holocaust: A Reconstruction,” in Journal of Jewish Thought & Philosophy 22 (2014): 52-53.

- 78

Zentrale Stelle, [Vernehmungsprotokoll Konrad Pohlenk], 109.

- 79

Although this might be a mistake; according to the information on the document at the Yad Vashem Database of Names, Leib Westerman was already murdered in late June.

- 80

Efrat Komisar deserves the credit for this discovery.

- 81

Reinhard Wiener to Bundesarchiv Koblenz, Re: Amateurfilme; hier: Judenexekution Libau 1941, 10.10.1965, BA Accession Files, AZ 5262/Wiener.

- 82

Bundesarchiv Koblenz to Reinhard Wiener, Re: Dokumentarfilmmaterial aus dem 2. Weltkrieg, 24.1.1961, BA Accession Files, AZ 5262/Wiener.

- 83

Reinhard Wiener, “Dokumentarfilmmaterial: Amateurfilmmaterial aus dem Bereich der ehemaligen Kriegsmarine 1939-1941,” Appendix to: Reinhard Wiener to Bundesarchiv Koblenz, Re: Dokumentarfilmmaterial aus dem 2. Weltkrieg, 19.3.1961, BA Accession Files, AZ 5262/Wiener.

- 84

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Trophy, evidence, document,” 516. Clerc and Gerhard Paul also mention Schier-Gribowsky’s film as the first using Wiener’s footage. Clerc. Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 248 and 523; Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur, 316.

- 85

Fabian Schmidt, “The Westerbork Film Revisited: Provenance, the Re-Use of Archive Material and Holocaust Remembrances,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 40, no. 4 (2020): 702-731.

- 86

Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 248.

- 87

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Trophy, evidence, document,” 516. Clerc analyses the presentation of the footage and its legal and historiographic implications in detail: Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 524-582. Paul also mentions the Eichmann trial as an occasion of public screening. Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur, 315.

- 88

State of Israel, Ministry of Justice, The Trial of Adolf Eichmann: Records of Proceedings in the District Court of Jerusalem 3 (Jerusalem: Israeli State Archives/Yad Vashem, 1992), 991. Paul seems to have overlooked this reference and therefore notes in his analysis of Wiener's film that there is no information about how Wiener's film came to Jerusalem. Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur, 315. Clerc believes that the reference to Schier-Gribowsky’s film in the transcript of the trial answers this question. Clerc, Deux Minutes et Quatorze Seconds, 525. However, he fails to provide any clues as to the exact circumstances of how Hausner came to be in possession of Auf den Spuren des Henkers.

- 89