TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935)

On the Way to an Archaeological Biography of an Iconic Film

Table of Contents

From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards

TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935)

Contested Memory

DER EWIGE JUDE (1940)

From Home Movie to Historical Document

A Living Document

Archiving the Ghetto

The Westerbork Film

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Wahl, Chris. “TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935): On the Way to an Archaeological Biography of an Iconic Film.” Research in Film and History 7 (2025): 1–50. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/24051.

“TRIUMPH DES WILLENS is probably the most famous and successful political documentary of all time.”1

TRIUMPH DES WILLENS / TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (TdW) has been analyzed many times; there are a variety of texts on the circumstances of its creation, its aesthetic strategies, its historical contexts and its political relevance. However, one of the most influential of those who have studied it to date, the film historian Martin Loiperdinger, identified two gaps in research back in the 1980s that have not been closed since: the film’s material history, i.e. its different versions, and the dissemination history of TdW, the migration of its images and sounds into countless other film and television productions.2

In 2016, I began collecting information on these two issues and reflecting on the respective problems. This preparatory work and the preliminary considerations were one of the important starting points for the project, which we report on in this issue with several case studies. In the meantime, many files have become accessible to me, different versions of the film have been scanned, some especially for me, and a large data set of TdW quotes has accumulated; but of course, the questions have also multiplied. The original approach of following the various prints through the archives and the shots and sequences appropriated from TdW through film and television history has become the enterprise of a comprehensive ‘biography’. What ‘life’ did the film lead after its completion? How were its authorized and prevented screenings connected to the public persona of Leni Riefenstahl? What do its reformattings and recontextualisations have to do with developments in contemporary history and memory culture? How has the status of the film changed over time and what influence does its fragmentation into small ‘bites’ or clips have on the perception of the original feature-length film? In addition, the question of the migration of images from TdW also raises the question of where the images in TdW actually come from, i.e. not how they were filmed and by whom, but which visual traditions they connect to. The study of TdW as a digital copy also enables repeated, intensive viewing of the images, which allows previous observations on the documentary and symbolic value of the film to be specified or expanded. And the expiry of the blocking period for some files makes it possible for the first time to evaluate the somewhat irresponsible handling of the film by the German federal government.

Even though the majority of the data and information collected is still awaiting analysis, which will be completed and published as a monograph in 2025, I would like to give a small foretaste of the results focusing on the material history of the film and its main versions, on the tension between document(ary) and propaganda (film) as well as on some general questions of TdW's iconicity and the aesthetic tradition in which it stands.

The Contested Sequences: Reichswehr and Stahlhelm

The camera negative of TdW has not survived. According to a “report on the recovery” of TdW in Riefenstahl's estate,3 which she wrote herself on April 20, 1974, she had it stored at the end of the war together with a lavender print in her second home in Kitzbühel, from where the French occupying forces took it to Paris. Geyer film laboratories in Berlin allegedly held another lavender in February 1950 which the American occupying forces eventually confiscated. The director was still searching for the negative and lavenders in 1981, as a letter from the Library of Congress (LoC) reveals,4 but the materials have been lost to this day. Instead, Riefenstahl was able to borrow a theatrical print from an unnamed Eastern Bloc country in the early 1960s for a large sum and have a new dup-negative made from it at Arri film laboratories.5 The Eastern Bloc country in question was expressly not the GDR, whose State Film Archive (SFA) also housed TdW material that Erwin Leiser used for his film DEN BLODIGA TIDEN / MEIN KAMPF (SE/DE 1960). A nitrate print from the SFA, which must have been assembled from two different materials at some point and has been in the film archive of the German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv, BArch) since reunification, is the most complete surviving version of the film with a length of approx. 3,064 meters. In early 2019, shortly before the in-house film laboratory was dismantled, it was copied at the Federal Archives and has since undergone digitization at Cinegrell. After a decades-long history of defensive handling of the film in Germany, this version of TdW has recently become freely accessible in the Federal Archives' new digital reading room.6

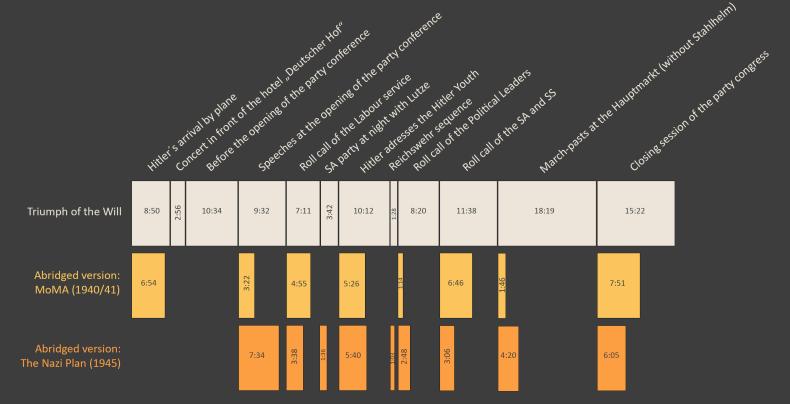

According to the censorship notice dated March 26, 1935, the original length of the premiere version of March 28, 1935, was 3,109 meters, that of the censored 16mm version six months later was 1,232 meters, which corresponds to around 3,078 meters on 35mm. The 3,064-meter version in the BA contains to separate chapters, the approximately 40-meter-long demonstration exercise of the Reichswehr (which was renamed the Wehrmacht after the reintroduction of compulsory military service on March 16, 1935) and the march-past of the Stahlhelm (the League of Frontline Soldiers of World War I, which was disbanded on November, 7 1935) of approximately 44 meters. Neither sequence played a role in the appropriation history of TdW, but it remains to be clarified whether they were part of the ‘original’ versions issued in 1935.

The companion book to TdW, Hinter den Kulissen des Reichsparteitag-Films, ghostwritten by the former editor-in-chief of the Film-Kurier, Ernst Jäger, says about the last day of the event, September 10, 1934: “Unfortunately, we have no more sun on Monday. The sky looks all gray. That only makes for bad pictures.”7 According to Riefenstahl's memoirs, she received a visit from two generals, one of them Walter von Reichenau, in early December 1934 in the editing room set up at Geyer especially for her and this film. The two military officers examined the Reichswehr sequences and demanded that they be retained in the film, while Riefenstahl wanted to discard them due to the poor image quality. Hitler later tried to mediate, and she claims to have suggested to him to make a film only about the Wehrmacht in 1935 to appease the army,8 which she ultimately did with TAG DER FREIHEIT! – UNSERE WEHRMACHT (DE 1935). In her memoirs, Riefenstahl denies having retained the Reichswehr shots, which primarily show the cavalry, in the premiere version.9 She told Loiperdinger that Ufa had subsequently reinserted them without her knowledge.10 In his review of the premiere, however, Ernst Jäger noted: “Marching pictures of the Reichswehr, the nation's armor bearer, are not included in the march-past for technical reasons. But the exercises of the cavalry are.”11

Nevertheless, Loiperdinger writes that only the censorship card can definitively decide whether the Reichswehr sequence was part of the premiere version.12 Since it has not survived, there is only the usual entry in the weekly overview published by the magazine Licht-Bild-Bühne (LBB) on the “decisions of the film inspection authorities,” according to which the process took place two days before the premiere. Riefenstahl herself stated in her memoirs that there had been no censorship at all before the premiere, as she had worked on the film until the very last minute.13 Perhaps this is even true and the Ufa as the distributor of the film only pretended as if there had been a censorship decision and fibbed about the relevant details. In Riefenstahl's estate there is a tear-out of the LBB overview, on which it is noted in red ballpoint pen as evidence for this thesis that TdW was the only film for which “NSDAP” was ever stated as the producer. For all other party films, it would otherwise always say, “Reich Propaganda Directorate of the NSDAP” and two films in the same overview support the argument. The Ufa, as the responsible distributor of TdW, had therefore ‘erroneously’ filled it in that way.14

But even if there had been a censorship card and it had survived, the case would not be so easy to decide – this is shown by the censorship card of the 16mm version that has survived. As is usually the case with censorship cards, the speech texts are documented on it, but there is no information about the picture content. Since neither the Reichswehr nor the Stahlhelm sequence contains a speech, the censorship card cannot provide any clear evidence that they belong to this version. On the other hand, the stated film lengths are telling. The version in the BA, which contains both sequences in question, is 3,064 meters long. According to the censorship card, the 16mm version, converted to 35mm, was about 3,078 meters long, while the premiere version was 3,109 meters long according to the published censorship decision and Ernst Jäger's film review. It is therefore very likely that both the Reichswehr and Stahlhelm sequences were included in the two contemporary versions and that the few meters missing in one of them (and in the BA version, for that matter) are due, for example, to differences in measurement or to wear and tear on the material. Although David Culbert concludes from the lengths that the 16mm version no longer contained the Stahlhelm, as this organization had been dissolved in the meantime,15 this cannot be true, as the dissolution happened only two months after the censorship card was filled out. The Stahlhelm sequence is also longer than the noted difference in length between the premiere and 16mm version. On the other hand, it must have been cut out soon after the dissolution, as it is missing from the print acquired by the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in 1936 – as well as from all other known versions except the one in the BA.

Klaus Kanzog assumes that the somewhat shorter version of TdW (3,030 meters), which was censored in 1939, no longer contained the Reichswehr sequence.16 That may be, after all, the Wehrmacht film from the 1935 Nuremberg Party Rally that Riefenstahl had promised and which had been made in the meantime, but the TdW copies that went to the Imperial War Museum (IWM) in London and the Library of Congress (LoC) in Washington as spoils of war did contain it. When the BA received a copy of TdW from the LoC on August 30, 1966, as part of the restitution of film material, the Reichswehr sequence was immediately separated, as it was mistakenly thought to be material taken from TAG DER FREIHEIT.17 Last but not least, it should be noted that in SANDRA MAISCHBERGER MEETS LENI RIEFENSTAHL (DE 2002), her last major interview, Riefenstahl makes the following statement: “The Wehrmacht is part of it, the Wehrmacht belongs in the TRIUMPH [OF THE WILL].”

The Abridged Versions: MoMA and THE NAZI PLAN (US 1945)

For the Film Library at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York, which was newly founded in 1935, the married couple John Abbott and Iris Barry, director and curator, traveled to Berlin in the first half of June 1936 to view films in the cinema of the Reich Chamber of Film.18 In her subsequently published travel report, which completely ignores the political situation in Germany, Barry goes into detail about TdW, which must have made a great impression on her.19 In July, the couple came to Berlin again to finalize the acquisition of a whole series of films for the library, allegedly with the support of Leni Riefenstahl.20 Among them was TdW, which, according to a letter from Barry to the Alien Property Custodian dated November 25, 1942, finally arrived at MoMA as an “unofficial loan” in April 1938 via SS Untersturmführer Ulrich Freiherr von Gienanth from the Reich Ministry of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, employed as librarian at the German Embassy in Washington.21 Iris Barry always gives the production time of the film as 1934–36. In one document, she writes that “the laborious work of editing and sound-tracking the picture was not completed by Miss Riefenstahl until 1936”22 – information that must have come directly from the director and perhaps has to do with work on a short version of the film (1,658 meters, approx. 60 minutes) that has not survived and was censored in 1936.

From September 1940, an abridged version of TdW that runs for about 42 minutes was produced at MoMA and eventually “exhibited to US government officials” in March 1942 (after the USA had entered the war on December 11, 1941).23 In response to this screening, President Roosevelt, overwhelmed by its propagandistic power, is said to have personally ordered that the film not be shown publicly.24 Since then, the USA considered TdW as “seized enemy property” and the library was instructed to use it only in the context of teaching and research.25 In fact, according to Stuart Liebman, the abridged version has been used primarily for a long time.26 But who edited it? In his memoirs, the legendary director Luis Buñuel claims that he did this with the help of a German assistant within two or three weeks. René Clair and Charles Chaplin, writes Buñuel, watched the film together, one was horrified, the other couldn't stop laughing.27 Riefenstahl, for her part, called the short version a “mockery of my work” when she saw it after the war.28 As the current film curator at MoMA, Ron Magliozzi, declares in a clarifying statement,29 it is possible that Buñuel, who was employed at MoMA in a different capacity only from January 1941, was consulted at a certain point, but there is no evidence in the documents of his involvement in the abridged version, whereas there is every indication that the Film Library's technical officer Edward F. Kerns had a hand in it.

On December 11, 1945, exactly four years to the day after the USA entered the war, the prosecution showed THE NAZI PLAN in the courtroom at Nuremberg, twelve days after NAZI CONCENTRATION AND PRISON CAMPS (US 1945). The Hollywood director and later two-time Oscar winner George Stevens, who allegedly decided to enlist on the same night in the winter of 1941/42 that he saw TdW in a screening room in Los Angeles, was responsible for both compilations: “Watching the movie, he said years later, he realized that ‘all film [...] is propaganda’.”30 Part of the film material from the 1920s to 1944 that THE NAZI PLAN contains is therefore unsurprisingly also a version of TdW that is around 39 minutes long. The screening of Riefenstahl's work was intended to link individuals with deeds whose consequences, documented in NAZI CONCENTRATION AND PRISON CAMPS, had made a “sensational”31 impression on the defendants, which did not stop them from refusing to take responsibility. Since Hitler's former deputy Rudolf Hess, who makes an impressive appearance as a whip for the assembled party members in TdW, pretended to suffer from amnesia, he had already been shown the film on November 8, 1945,32 before the start of the trial, however, to no avail.

A comparison of the two short versions of almost equal length illustrates the different purposes for which they were made: while MoMA wanted to demonstrate the potential of (German) film propaganda to American officials and was therefore interested in visually spectacular and overwhelming passages, THE NAZI PLAN was quite factually concerned with identifying individuals, registering concrete statements as well as proving early militarization in the Nazi state. In this respect, it is not surprising that Stevens only begins with the third chapter, the opening speeches, of which he uses considerably more material than the MoMA version, which in contrast shows Hitler's iconic approach to Nuremberg, the opening sequence of TdW, almost in its entirety. In the roll call of the political leaders, MoMA focuses on the end with the night-time torchlight procession; Stevens uses twice as much material but omits the end and sticks to Hitler's speech. The equally impressive and later frequently appropriated images of the SA and SS roll call are also only quoted in the MoMA version, while THE NAZI PLAN chooses a much shorter excerpt and again concentrates on the speeches. Instead, Stevens shows a few minutes more of the 18-minute-long march-past of the various units in Nuremberg's Old Town, just as he uses excerpts from the SA party at night and the Reichswehr sequence, in contrast to the MoMA version. This juxtaposition makes it clear why THE NAZI PLAN was not simply based on the MoMA's existing abridged version, which Stevens was certainly familiar with and would have had access to. The different emphasis of the two war-related US adaptations of TdW introduced two fundamental and fundamentally different attitudes and interests towards the film that would also determine the appropriations of the following decades.

The 1970s Versions: German Television and Director's Cut

Two other versions of TdW from the 1970s also deserve mention. One is the German television version, the other the version “from the last hand,”33 Riefenstahl's ‘director's cut’ so to speak. The background to this new public attention for the film was the so-called “Hitler wave”34 – simultaneously a more unbiased historical examination of Hitler and National Socialism, an international, partly feminist re-evaluation of the Nazi propagandist Leni Riefenstahl – there is talk of a “Riefenstahl renaissance”35 – and a general penetration of Nazi insignia into popular culture. The television broadcast of TdW in Germany had a prelude with the broadcast on BBC2 on November 23, 1973, which led to a behind-the-scenes legal dispute between Riefenstahl's lawyer, the company Transit representing the film rights of the Federal Republic of Germany, and the German Embassy in London (or the Foreign Office) on the one side, and the BBC and the IWM supplying the film copy on the other.36 The British position was that the Enemy Property Act of 1953 invalidated all German copyrights from the period before 1945, at least for the United Kingdom, while the German position was that the Act only applied to the possession of the film material, but not to the exploitation of rights. The German side demanded a sum of DM 25,000 for the broadcast, while the British side offered compensation of £ 1,000 as an expression of ‘goodwill’. At the political level, it was finally recognized in late 1976, after obtaining an expert opinion, that “in the event of a judicial clarification [...] the German position would have no prospect of success.”37 This dispute resulted in a memorable letter from the IWM to the German side, in which the following assessment was made, which is worth quoting in full:

We regret to say that in our view, and in the view of many organisations and individuals throughout the world with whom we have discussed this matter, the reputation built up by Transit Film in some ways reflects badly (if perhaps inadvertently) on the West German Government. Particular objection is made to what appear by international standards to be the excessive scale of fees charged by Transit. We have been told by colleagues in, for instance, France, Italy and the Netherlands that they do not in any case recognise these rights. I think there is a fairly general resentment about the scale of profits made by Transit from the products of the Nazi regime.38

From today's perspective, the last sentence is also so disturbing because it did not prevent Transit and the German Federal Ministry of the Interior (Bundesministerium des Innern, BMI) from concluding an agreement with Leni Riefenstahl on August 22, 1974, through which the Federal Republic entered into a commercial exploitation partnership with her regarding the film TdW and which also granted her the right to control the non-commercial exploitation. Until her death, the public handling of the notorious propaganda film, and particularly its use in educational work, was largely left to the Nazi director herself.39 As a letter from her lawyer testifies, the BBC broadcast and the broadcast of TdW on German television, which had already been announced in 1973, acted as a catalyst for Riefenstahl's successful efforts in this matter.40 Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR) and the two smaller stations in the ‘northern chain’, Radio Bremen (RB) and Sender Freies Berlin (SFB), broadcast TdW in prime time (20:15) on Sunday, September 29, 1974, with a ten-minute epilogue by historian Joachim Fest, whose biography of Hitler, published a year earlier, had brought him great international attention. Hessischer Rundfunk (HR) followed on October 1, 1974, at a slightly later time (21:50). On September 4, 1976, it repeated the program at 21:35, joined by the three south-west stations Süddeutscher Rundfunk (SDR), Südwestfunk (SWF) and Saarländischer Rundfunk (SR). Finally, there was a last broadcast on September 9, 1977, at 21:45 with the participation of the northern chain and Hessischer Rundfunk.41 While the broadcast in 1974 did not result in any “remarkable, let alone clarifying journalistic reaction” and went off without a “scandal,”42 Riefenstahl was invited to the popular talk show JE SPÄTER DER ABEND on October 30, 1976, in which the director, visibly irritated, had to defend herself against a female worker who obviously did not like her, emphasizing, among other things, that the programming of TdW had not been approved by her. The rerun of the film in September 1977 was followed just six days later by a response in the GDR television magazine show OBJEKTIV, which was directed not only against the film, but above all against Joachim Fest. Excerpts from TdW and Fest's commentary are repeatedly played, to which presenter Ulrich Makosch reacts smugly. Of the film itself he says that it is “one of the last pieces in West Germany to make fascism acceptable. [...] Perhaps it [...] had more viewers last week than Goebbels was able to get for it at the time.” He accuses Fest of saying nothing about “the crimes of fascism” in his commentary, which is not entirely true; Auschwitz and the Reichskristallnacht are mentioned. Makosch, however, is concerned with exaggerated provocation and scandalization: “I sometimes wonder whether the authors of this program might not have had a place reserved for them in the Reich Ministry of Propaganda.” The concluding remark that the film and commentary “objectively [as the name of the magazine says] serve to fascistize and benefit the neo-Nazis” is followed by a tendentious report from the city of Solingen, where a representative of the local German Communist Party (Deutsche Kommunistische Partei, DKP) complains about neo-Nazi graffiti, which, according to him, is encouraged not least by films such as HITLER: A CAREER (DE 1977), a compilation co-directed by Fest and being shown in a Solingen cinema at the time.

As information from a former employee of the State Film Archive of the GDR suggests, the country considered Fest indeed a persona non grata and rejected him as an archive user.43 Even if the criticism expressed in OBJEKTIV was exaggerated, it is noticeable from today's perspective that, as Daniel Kothenschulte writes,44 Fest views film aesthetics and film content separately from one another and that he basically says very little about the film itself, but rather about the character of the Nazi regime, whereby he also seems to be concerned with excusing and apologizing for ordinary Germans. The zeitgeist had indeed changed: “Anyone who would have seriously considered showing Leni Riefenstahl's party rally film TdW on television about ten years ago would have been labeled an incorrigible, conniving Nazi. Today it's different.”45

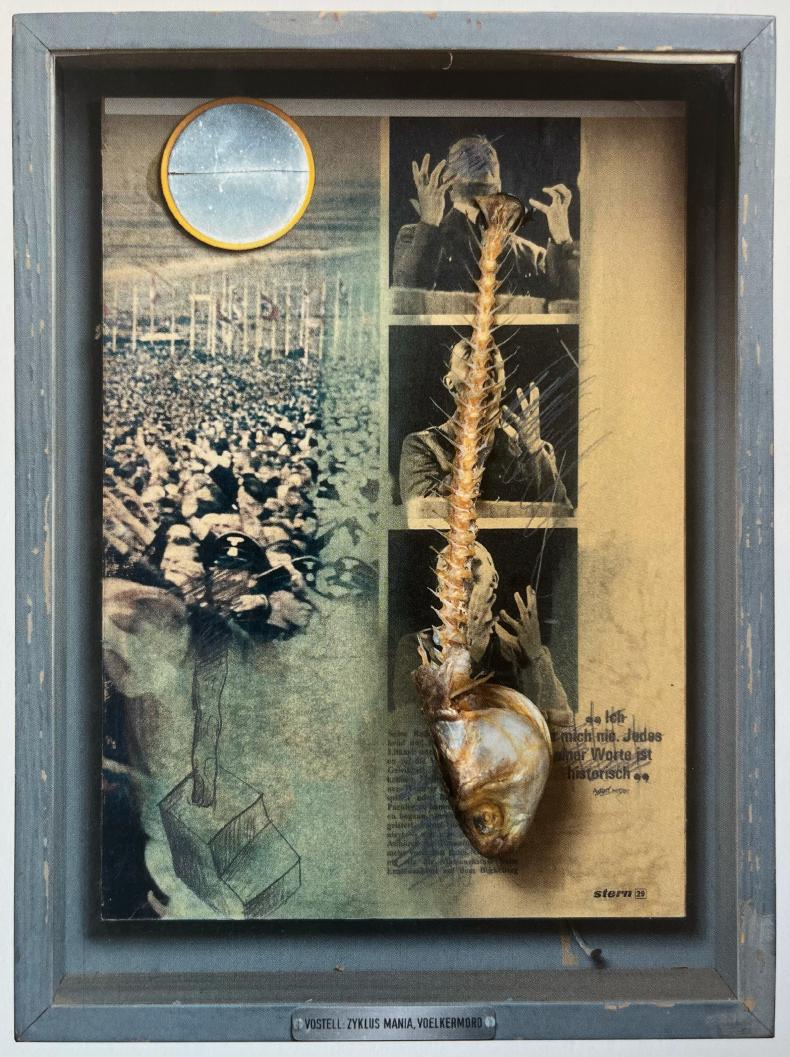

An object entitled “Genocide” from the 40-part “Mania” cycle by Fluxus artist Wolf Vostell, for which he used page 29 from issue 28 of the magazine Stern from July 5, 1973 as a basis , can be understood as a reaction to this change of mood and as an anticipated artistic study of the television broadcasts from 1974 onwards. The page is from the first in a series that ran over several issues and printed excerpts from Fest's biography of Hitler. In addition to a detail of a photo by Heinrich Jaeger, the assistant of Hitler's personal photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, which shows Hitler at the Reich Harvest Festival on the Bückeberg and the larger part of which was printed on page 28, it also contains three frames of Hitler's speech at the end of the Party Congress in 1934, taken from TdW. Both the text on the page and the pictures of Hitler have been crossed out, the Jaeger photo is painted over with a kind of shame or torture stake; a fish skeleton and a broken pocket mirror lie on the page.

What neither Fest nor anyone else commented on, and apparently only Martin Loiperdinger46 and Leni Riefenstahl noticed, concerned the actually irritating fact of the broadcast: in the underlying 16mm copy originating from the BA, which was later also made available via the Institute for Science and Film (Institut für den wissenschaftlichen Film, IWF), a chapter swap had taken place, which confused the structure of the Party Rally depicted in the film (which deviated from the actual sequence of events anyway). The roll call of the political leaders filmed at dusk now no longer came before the roll call of the SA and SS, but before the night-time event of the SA with Chief of Staff Lutze, so that two night sequences directly followed one another, and the director's intended chain of day-night-day-night-day-night-day got jumbled. The reason for this change has not yet been determined; Riefenstahl herself suspected a “mix-up” at the film laboratory.47 In addition to the re-editing, she was also bothered by the inclusion of the Reichswehr sequence. Presumably to enforce a version authorized by herself once and for all, she therefore had “a new print made at Arri for the Munich Film Museum,”48 in which not only the army exercise was missing, but also the nightly outdoor concert for Hitler in front of the hotel Deutscher Hof.49 According to Riefenstahl, this last omission also had “purely artistic reasons,” as there was not only “far too little light” during the shoot, but the “long complex” was “unimportant and superfluous” anyway.50 She had already secured the copyright for the same version in the LoC on November 7, 1975 – when she realized that there was no legal basis for her to earn money from screenings of TdW in the USA51 – and the receipt of the corresponding print was registered on February 18, 1976.52 However, this ‘director's cut’, which was shorter rather than longer as usual, did not catch on.

Document(ary) or Propaganda (Film)? What Riefenstahl Did Not Include in TdW

One controversial question, as we have seen, is whether certain aspects of the 1934 Reich Party Rally (Reichswehr, Stahlhelm, outdoor concert) actually shot by her cameramen are integral parts of Riefenstahl's film; the other question is which aspects were (deliberately) never shot or were eliminated early on, i.e. to what extent TdW is a document of the 1934 Reich Party Rally or propaganda that makes the “soul of National Socialism [...] come alive,” as a contemporary journalist put it,53 and excludes everything that would disturb the “self-portrayal of National Socialism.”54 Riefenstahl's defense strategy after the war – whether in an “affidavit” of August 2, 1960, which she made in the course of her lawsuits against the production company of Erwin Leiser's DEN BLODIGA TIDEN,55 or in conversation with Ray Müller in DIE MACHT DER BILDER (DE 1993) – was explicitly oriented towards a (not unproblematic) distinction between “documentary film” and “propaganda film,” the central criterion of which she understood to be the question of voice-over: since there is none in TdW that would convey the attitude and political assessment of the filmmaker or other authorities, it cannot be a propaganda film. The thin ice she was walking on here in terms of argumentation concerned the question of the construction of reality in films. On the one hand, the director was celebrated in the Film-Kurier in 1936 under the label “Riefenstahl School” for having shaped a “German documentary film style,” which, through the skillful use of camera, editing and music based on a sense of rhythm, stood as “absolute film” alongside the feature film.56 On the other hand, after the war and especially from the 1960s onwards, when she was once again praised for her film aesthetic merits and enjoyed it, she always played down her creative input when it came to the fact that form could also contain a message for which one must take responsibility, that form and content are ultimately inseparable: “I experienced the thrill of being able to give filmic form to real events ‘without distorting them’.”57 With the emergence of various currents of observational documentary film, her position of alleged selective self-effacement became acceptable. The representatives of direct cinema, for example, played down their own influence exercised through perspective and selection, and propagated a rejection of voice-over, which of course was not always adhered to.58 The background, both for Riefenstahl in the 1930s and for the young documentary filmmakers of the 1960s, was a demarcation against newsreels and cultural films, which cultivated a rhetorical, omniscient style. In this respect, she was able to simultaneously stage herself as a pioneer of a purist filmmaking approach striving for objectivity or pretending objectivity and as an ingenious designer of lush audiovisual event reports that anticipated later core disciplines of television.

Part of her argument for the authenticity of the film was Riefenstahl's steadfast public denial of re-enacted footage in TdW.59 However, when Albert Speer, the architect of the Reich Party Rallies who had been released from prison, described in his memoirs in 1969 how large parts of the speeches of the opening congress had been re-shot in a studio in Berlin-Johannesthal because the original material was unusable,60 she replied to him in a private letter, that there had indeed been a day of shooting in the studio, but that on this occasion only the speech of Julius Streicher, the NSDAP Gauleiter of Middle Franconia and publisher of the anti-Semitic hate paper Der Stürmer, who was a friend of hers61 despite her lifelong denials, had been re-filmed, because the cameraman in Nuremberg had run out of material.62 If you look at the corresponding sequence today, it is noticeable that there is at least one other speaker whose shot shows the same conspicuous features as Streicher's: the background for Otto Dietrich, Chairman of the Reich Association of the German Press (RDP) and Vice President of the Reich Press Chamber, is also deep black with a slight drawing of light rays, the guiding light comes from the left with a brightening from the right, the sound is incredibly clean.

The question of how many and which passages were reshot in the studio can no longer be definitively answered today. But apart from delayed reshoots, it is also clear that the workers' choir in the labor service sequence carried out its famous question-and-answer game about the origins of the individual participants from all corners of the Reich exclusively for Riefenstahl's cameras and microphones; the rest of the tens of thousands of people on the Zeppelin meadow are unlikely to have noticed any of this visually or acoustically – not even Hitler. What Hitler may have sensed, but the film did not capture, is the extremely tense atmosphere when for the first time after the so-called ‘Röhm Putsch’ the dictator was confronted by the SA, which had been stripped of its leadership and was generally disempowered:

There was considerable tension in the stadium and I noticed that Hitler's own S.S. bodyguard was drawn up in force in front of him, separating him from the mass of the brown-shirts. We wondered if just one of those fifty thousand brown-shirts wouldn't pull a revolver, but not one did.63

Riefenstahl did not document all events of the Party Rally. In addition to the press reception, the municipal reception for the state and party leaders in the town hall, the cultural conference and the fair,64 she also omitted the women's congress.65 The “millions of German women [and girls]” who were “mobilized for the annual party congresses”66 can only be seen in TdW to the extent that they were used as ecstatic acolytes or appear fleetingly in the picture as passive spectators.

Very few people will have noticed that at one point in the Hitler Youth sequence, shortly before Hitler enters the stadium, a few female representatives of the Bund Deutscher Mädel (BDM) can be seen lined up in the background for a few seconds.

According to Tom Saunders' interpretation, the ubiquitous flags and banners in TdW stood in for the barely present female bodies.67

While Heinrich Hoffmann's photo book of the Party Rally 1934 at least contains two pictures of “severely war-damaged” and “war victims” in wheelchairs,68 according to Martin Loiperdinger and Jens Eder, Riefenstahl deliberately avoided anything crude, ugly or critical that would have disturbed the intended overall effect of the sublime.69 Although such “mishaps were not isolated cases year after year,” images of “failed marches-past where nothing worked”70 are indeed sought in vain in TdW, as are those of mountains of garbage71 or “excesses of violence and alcohol”72, which led to “unbelievable vandalism in the mass quarters,” for which Thamer primarily blames the Political Leaders, who were maligned as “golden pheasants.”73 A silent 16mm amateur film (103 meters) has been preserved in the Schleswig-Holstein state archives, which shows the “Journey of the Political Leaders from the Pinneberg district to the Reich Party Congress in Nuremberg in 1934.”74 It is an interesting mixture of similar, only less well executed motifs as in TdW (the Old Town of Nuremberg, the shadow of an airplane, the motorcade with the Führer, the SA and SS roll call in the Luitpold Arena, the roll call of the Political Leaders on the Zeppelin meadow filmed at dusk, marches-past) and images that we do not get from Riefenstahl: the journey in the smoky train compartment with ugly people playing cards, the feisty “golden pheasants” up close and in daylight, a folk festival atmosphere with people eating and drinking. Violence and alcoholic excesses were, however, also omitted here.

The Agency Karl Höffkes (AKH), which advertises on its website as having the “world's largest stock of privately shot films from the years 1900 to 1945,” has a whole series of amateur films shot during the Reich Party Rallies, including in 1934. One of them, about 25 minutes long, was shot by the “Gruppe 209, Siegen,” according to a title card.75 The opening statement proudly proclaims: “September 6, 1934, was a milestone in the development of the German Labor Service. For the first time, the brown army of labor marched before the Führer.” Like the men from Pinneberg, these men also begin their film with the journey in the train compartment, but unlike the political leaders, who are obviously housed in the city center, they spend the night in a tent camp, where they march to from the station. Brief glimpses of camp life are reminiscent of TdW. In the following scenes of the group's official activities, it is particularly astonishing how close the camera can get to Hitler on Nuremberg's main market square. Various other men with photo and film cameras are also visible, including Leni Riefenstahl's teams. This is a phenomenon that is familiar from TdW, at least when viewed frame-by-frame: the omnipresence of cameras in September 1934. Exactly one year earlier, the “Reich Association of German Amateur Photographers” (RDA) had been founded to encourage private individuals “to actively participate in National Socialist reconstruction.”76 In Nuremberg, countless people tried their hand at photojournalism, which leads to a moment at the end of the Hitler Youth sequence in TdW that is reminiscent of today's use of cell phones at a pop concert: Hitler is centered in this picture frame, but not in the foreground – in the foreground is his worship as the object of a cult, as “Führer icon,”77 as a pop icon.

TdW as an Iconic Film and a Film Full of Icons

“Political-personal icons” and “pop icons” are two of the different types of “media icons” that Gerhard Paul defines for the 20th century. According to Paul, media icons are the mass media variant of icons, which he generally calls

all those images that have a high degree of recognition due to the frequency, duration and distribution of their publication, that stand out from the flood of media images due to their iconic potential and their utility value, that have a special emotional effect on the viewer and that function as cognitive and/or emotional models on a contemporary national or global scale.78

TdW is a media event in that it is probably the first time that the merging of a political-personal into a pop icon is documented and staged at the same time. The frequently described sacred elements of the Party Rally ceremony add a solemn note to this transformation – the image of a saint is superimposed over the political and pop icon: Hitler as a classic icon.

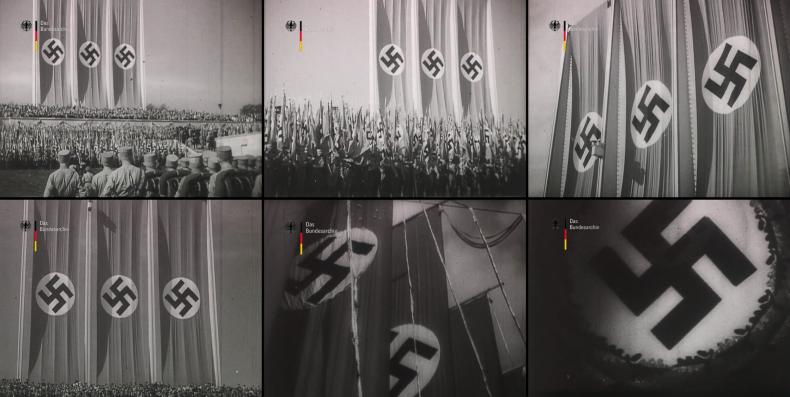

The second star of the film is the swastika, whether on flags or armbands or carved in stone, it is omnipresent.

With Gerhard Paul, it could perhaps be described as a “super-icon” – “known, communicated and effective across cultures, generations and classes.”79 In Christ to Coke, Martin Kemp devotes several pages to the swastika as a “basic and primitive variation on the cross,”80 illustrated with a screen shot from TdW.81 According to Kemp82, but also according to David D. Perlmutter,83 there are two general ways for images to attain iconic status: through frequent use or through a striking, immediately appealing and memorable design. It remains to be discussed whether TdW can be called an iconic film because it has a large number of shots that have been used extremely frequently and that often captivate through their memorable composition. Apart from that, Kemp's statement that “moving images never become truly iconic without crystallizing into a memorable still” needs to be checked.84 This may be true for many shots from TdW, but entire passages from the opening sequence with the arrival by plane or from the consecration of the dead in the Luitpold Arena, for example, in which Herbert Wind's music plays no small role and which certainly strive for and develop the strongest emotional impact of all the sequences in the film, were often appropriated in other films or re-made for them, so that doubts can be raised as to the general validity of the statement. Two other emblems that can be described as icons, although they play a negligible role in the history of the appropriation of TdW, have a conspicuous presence in the film: the Mercedes-Benz 77085 used by Hitler at parades or rather the Mercedes star as an “icon of technology and progress”86

and the “eagle stylized as the ‘Aryan of the animal world’”87 as a totem of the state and the military, with which the film opens – as well as several other sequences. While TdW contains several combinations of swastika and eagle, Hitler and eagle, and Hitler and Mercedes, it was clearly not an aim to bring all four symbols together in a single shot.

Only for 65 of the 1,140 shots that make up TdW there is not a single record of appropriation. It is difficult to imagine another film of almost two hours in length for which the same applies. This breadth of appropriated images alone argues in favor of classifying the film as iconic. At least one appropriation can be proven for every single shot from the two chapters “Hitler's Arrival in Nuremberg” (136 shots) and “Appeal of the SA and SS” (107 shots), not least because they are mostly quoted in sequence blocks, which supports the argument that moving images can also be iconic, not just stills. Of the 15,588 appropriations of shots found to date, the largest number, 193, is accounted for by shot no. 934.

This bird's-eye view of a square of members of the National Socialist Motor Corps (NSKK) marching from left to right through the frame is a striking and memorable shot from TdW due to its extreme perspective and geometric arrangement, but it is also a representative example of the photography of the time, The New Vision, with which Heinrich Hoffmann also experimented. His photo volumes on the two Reich Party Congresses, 193388 as well as 1934, contain comparable images, in the latter they are captioned with the word “Discipline.”

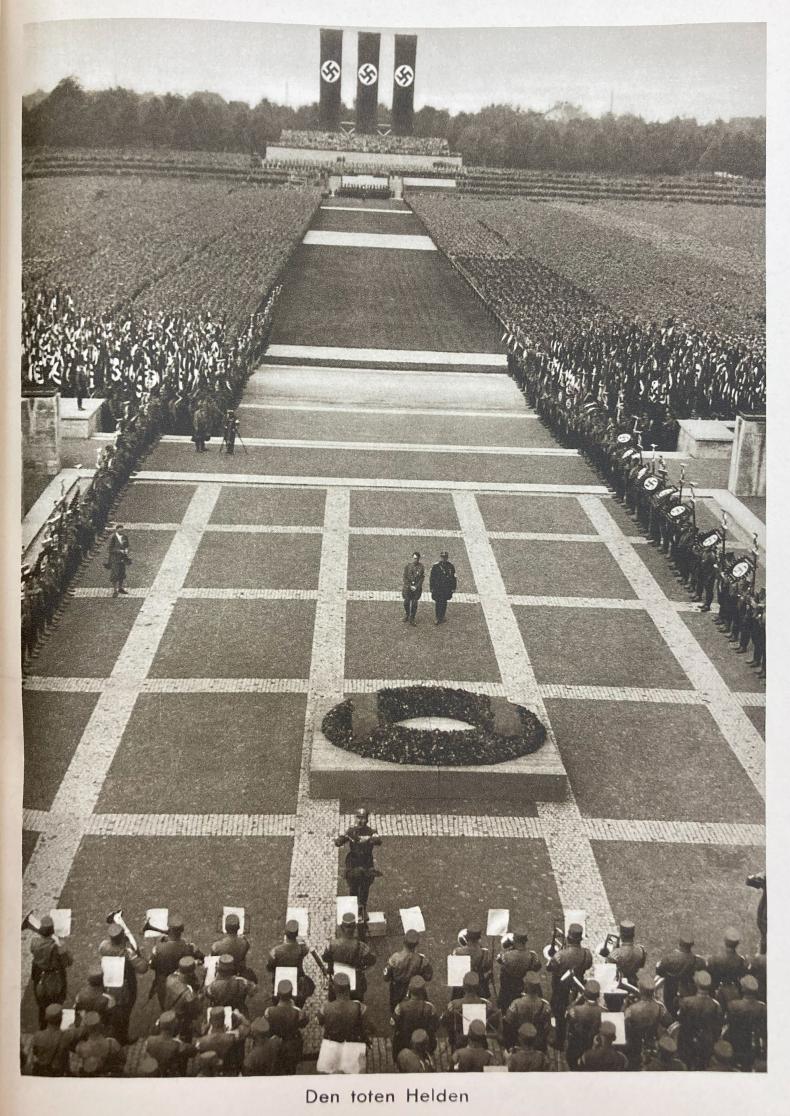

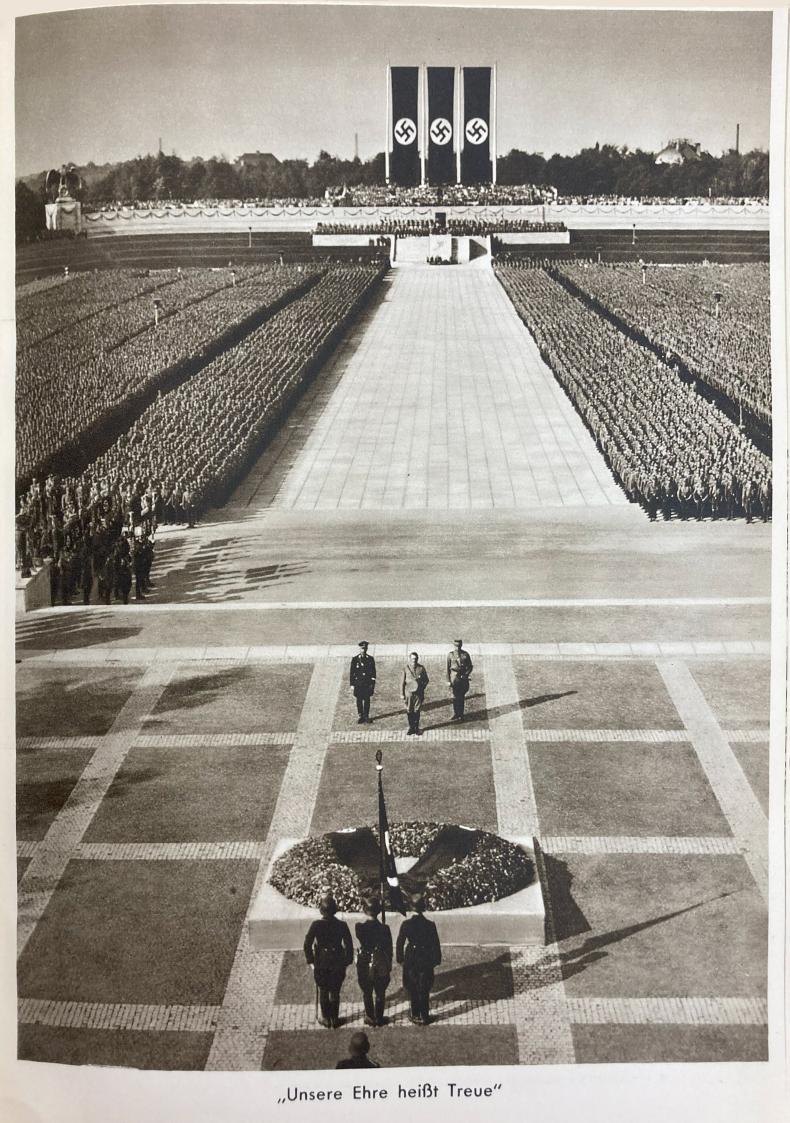

Both volumes also contain a photograph of Hitler at the memorial to the dead soldiers of World War I and the “Martyrs of the Nazi Movement.” Both pictures are taken from the Hall of Honor and show three huge Nazi flags with the swastika in the middle of the background, in front of which a wide path opens between the SA and SS cohorts along which Hitler walked.

The photo from 1933 shows the then chief of staff of the SA Ernst Röhm next to Hitler and is taken from a slightly greater height, so that parts of a band can still be seen in the foreground.

It was the central piece – among many other Hoffmann photographs celebrating the Nazi movement – in the design of the hall of honor of “Die Kamera. Ausstellung für Fotografie, Druck und Reproduktion” (The Camera. Exhibition for Photography, Printing and Reproduction), which took place in 1933 “in the exhibition halls at the Funkturm in Berlin”89 and was “celebrated as the most beautiful exhibition of the year,”90 “German above all in the cleanliness of the propagandistic effect.”91 Anyone entering the hall walked directly towards this picture, which was the only one in the room that was photographed and hung on end.92 The effect can hardly be overestimated, as Thamer emphasizes: “With the means of large-scale photography, which claimed to be an authentic document but at the same time was intended to evoke an emotional response in the viewer, elements of an overwhelming strategy had found their way into the exhibition.”93 And even if it was still possible to write in 1933 that there were “not yet any artistic forms of expression that speak to the people in such a way, and that have such a powerful effect as the large photo did here,”94 the same strategies would soon find its way into the film industry, under the label “Schule Riefenstahl.”

The photo from 1934 shows Hitler flanked by Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler and Viktor Lutze, successor to murdered Ernst Röhm. If one wanted to reduce TdW to a representative still, it would be conceivable to opt for this image of the ceremony honoring the dead, which has no direct equivalent in the film, but wonderfully illustrates its most famous sequence, which is central to the political background of the party congress. In fact, however, most books that include an image from TdW refer to a photograph showing a slightly later section of the same ceremony, taken on the other side of the arena from the elevator in one of the three flagpoles.

“Our opening image,” writes Paula Diehl in her essay on the Party Rally in Gerhard Paul's Bilder, die Geschichte schrieben (Pictures that made history), “is one of the best-known icons of Nazi propaganda and shows the most reproduced camera shot from Leni Riefenstahl's Party Rally film TRIUMPH DES WILLENS.”95 Strictly speaking, it is an original film frame, “enlarged and edited from the film by Gisela Lindbeck-Schneeberger,”96 which was first printed in Hinter den Kulissen des Reichsparteitag-Films.97 If one is even more precise, however, the picture shows a moment that cannot be seen in exactly the same way in the shot in question, no. 814, and must therefore come from material that was not used for the final cut.

That exactitude is not a necessary component of iconicity is also evidenced by the film's title, which has been referenced countless times in variations such as “The Triumph of Hitler's Will,”98 “Triumph of Good Will,”99 “Triumph of the Will to Have an Impact,”100 “Triumph of Her Will,”101 “Triumph of Age,”102 and “The Triumph of the Ordinary.”103 The more or less original meaning of these phrases feeds off the allusion to TdW, but they cement its iconicity (the essentially unchanging and yet adaptable extraordinary) precisely through slight deviations, through recontextualization. With adaptations such as these, the slogan ‘Triumph of the Will’ remains present without the need for a closer examination of the film: that too is iconicity. The final title of the film, which was originally to be called “Everything for Germany,”104 was allegedly chosen by Hitler himself105 and even became the title of the 1934 Party Rally (“Party Rally of Will”) in the public perception retrospectively, although it was actually called “Party Rally of Unity and Strength.”106 How did Hitler come up with this title? It is obvious that he must have taken it from the illustrated book of the same name by Heinrich Hoffmann, which was published in 1933 and in whose foreword the Reich Youth Leader Baldur von Schirach explains how the will of the “self-made man” Hitler triumphed on January 30, 1933.107 Ultimately, then, the title is a cipher for ‘Holy Hitler’, the political and pop icon himself.

Tradition and Zeitgeist

The fact that the will is so much in the foreground is again due to the zeitgeist. A psychological analysis of the will was published in the same year as TdW.108 Francis Courtade and Pierre Cadars claim that the motto was taken from Alfred Rosenberg's pseudo-philosophical Der Mythus des 20. Jahrhunderts (The Myth of the 20th Century) from 1930, which speaks of the “willfulness of Germanism” with eclectic reference to Schopenhauer.109 Alfred Baeumler, a serious Nazi exegete of Nietzsche, wrote about the will from a philosophical perspective in 1931:

To will is to command, but to command is an affect, and this affect is a “sudden explosion of force.” The path of the will is characterized by a series of explosions of force. What we understand by “willing” in the narrower sense, the conscious will, is only a concomitant of the essential, which is an outpouring of force.110

THE TRIUMPH OF POWERFUL COMMAND so to speak. The title condenses the film's self-indulgent propaganda, because according to Thamer, the truth was quite different:

In retrospect, Hitler's path to a dictatorial position both within the party and in its external representation shows a single-mindedness that suggests a consistent will to power, which in reality did not exist. It was rather the circumstances that favored this path [...].111

The circumstances and perhaps also, according to Norman Ohler, the drugs: “You only have to replace the words ‘iron energy’ and ‘will’ with ‘eucodal’ and ‘cocaine’ to get a little closer to the truth.”112 Tradition and zeitgeist were important factors for National Socialist propaganda in general, but also for TdW in particular. It was the historian Andreas Kötzing who, after having listened to one of my talks on the topic, asked me which films and trends TdW itself would tie in with. And although I was of course aware of a few references from the existing secondary literature, of the connection to Arnold Fanck and the mountain film for example, this question unsettled me for a long time and years later led me to check the references from the literature for their validity and to look for further references myself. When it comes to judging similarities, especially when it comes to comparing moving images, modern editing programs are ideal, and so I have tested assertions and assumptions by making a video essay. This tentative, still somewhat clumsy attempt, certainly neither complete nor definitive, was not originally intended for publication. Nevertheless, I consider it a useful, illustrative approach to the topic, which is why I have included it in this text.

TdW is an almost extreme example of the fact that films, like other cultural products, are, on the one hand, embedded in trends and traditions from which they benefit and which they comment on, while, on the other hand, their meaning and value transform over time and with changing circumstances. Riefenstahl's film functions like a gigantic marshalling yard, into which visual and narrative motifs entered, were placed on new tracks and released back into the world. Many of the TdW motifs whose sources are presented in this video essay were in turn directly quoted or recreated by other directors in the following decades, making the film an important locomotive of audiovisual culture in the second half of the 20th century – a phenomenon I will explore in the forthcoming monograph. In Sophie Fiennes’ THE PERVERT'S GUIDE TO IDEOLOGY (GB/IRL 2012), Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, embedded in the imagery of TdW, explains the phenomenon of National Socialism as an amalgam of reactionary and avant-garde elements. In this respect too, as the video essay shows, TdW embodies “the soul of National Socialism:” avant-garde in its form, reactionary in its message or avant-garde in its photography and editing, reactionary in its mise-en-scène; which is why these levels cannot be considered separately when evaluating the film and its director.

- 1

Stephen Brockmann, A Critical History of German Films (Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2010), 150–65.

- 2

Martin Loiperdinger, Der Parteitagsfilm TRIUMPH DES WILLENS von Leni Riefenstahl. Rituale der Mobilmachung (Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 1987).

- 3

“Bericht über die Wiederbeschaffung,” 29 April 1974, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 464, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Handschriftenabteilung (Stabi Berlin).

- 4

Paul C. Spehr (LoC) to Leni Riefenstahl, 3 August 1981, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 876, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin, Handschriftenabteilung.

- 5

“Bericht über die Wiederbeschaffung,” 29 April 1974, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl. 464, Stabi Berlin.

- 6

Bundesarchiv, Digitaler Lesesaal, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/11925/686607.

- 7

Leni Riefenstahl, Hinter den Kulissen des Reichsparteitag-Films (München: Zentralverlag der NSDAP Franz Eher Nachf. GmbH, 1935), 26.

- 8

Leni Riefenstahl, Memoiren (München: Knaus, 1987; Köln: Taschen, 2000), 227–29. Page references are to the Taschen edition.

- 9

Riefenstahl, Memoiren, 232.

- 10

Loiperdinger, Der Parteitagsfilm, 11.

- 11

_r. [Ernst Jäger], “Film-Kritik,” Film-Kurier, March 29, 1935.

- 12

Loiperdinger, Der Parteitagsfilm, 11.

- 13

Riefenstahl, Memoiren, 231.

- 14

“Entscheidungen der Filmprüfstellen,” Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 464, Stabi Berlin.

- 15

Aine Zimmermann, “Leni Riefenstahl and Propaganda Film: A Conversation with David Culbert,” Focus on German Studies 11 (2004), 282.

- 16

Klaus Kanzog, “Der Dokumentarfilm als politischer Katechismus. Bemerkungen zu Leni Riefenstahls Triumph des Willens (1935),” in Perspektiven des Dokumentarfilms, ed. Manfred Hattendorf (München: diskurs film Verlag, 1995), 68.

- 17

Loiperdinger, Der Parteitagsfilm, 11. The BA database shows that a 48-metre-long fragment of TdW was isolated from the nitrate print of the LoC and then copied and classified as a fragment of TAG DER FREIHEIT. The actual 744-metre film from the SFA only entered the BA after reunification.

- 18

Iris Barry, “Hunting the Film in Germany,” in East Side – West Side.Schätze aus dem Filmarchiv des MoMA. Eine Filmreihe im Kino Arsenal, 9. Mai– 5. Juni 2004, ed. Eva Orbanz (Berlin: SDK 2004), 60–61.

- 19

Barry, “Hunting the Film in Germany,” 62.

- 20

Robert Sitton, Lady in the Dark. Iris Barry and the Art of Film (New York: Columbia UP, 2014), 216.

- 21

Iris Barry to Z. G. McGee (Office of Alien Property Custodian), 25 November 1942, RG131, A1, 251, Box 0 “MoMA”, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); curriculum vitae of Ulrich Freiherr von Gienanth, 27 March 1935, R 9361-III, 526259, Bundesarchiv (BArch).

- 22

2-page introductory text to TdW by Iris Barry, undated, RG131, A1, 252, Box 15 “TDW #1”, NARA.

- 23

Ron Magliozzi, And [sic] introduction to archival records on Luis Bunuel; and the film library’s abridgement of ‘Triumph of the Will’ at the Museum of Modern Art (draft in process) (New York: Film Study Center, unpublished manuscript, December 2009).

- 24

Christian Delage, Caught on Camera. Film in the Courtroom from the Nuremberg Trials to the Trials of the Khmer Rouge (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014), 34.

- 25

Eileen Bowser, “Leni Riefenstahl and the Museum of Modern Art,” Film Comment 3, no. 1 (Winter 1965), 16.

- 26

Stuart Liebman, Triumph of the Will, Cineaste 27, no. 4 (Autumn 2002): 47. However, a list from the University of Illinois, Chicago shows a balanced picture: between 1968 and 1970, TdW was shown eight times, four times the long version and four times the abridged version. Kaye Miller (University of Illinois) to Leni Riefenstahl, 9 December 1970, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 448, Stabi Berlin.

- 27

Luis Buñuel, Mein letzter Seufzer. Erinnerungen (Berlin: Verlag Volk und Welt, 1988), 249.

- 28

Leni Riefenstahl to Williard Van Dyke (MoMA), 9 June 1971, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 448, Stabi Berlin.

- 29

Magliozzi, And [sic] introduction to archival records on Luis Bunuel.

- 30

Mark Harris, Five Came Back. A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War (New York: The Penguin Press, 2014), 6.

- 31

Budd Schulberg, “The Celluloid Noose,” The Screen Writer 2, no. 3 (August 1946): 14.

- 32

Delage, Caught on Camera, 111.

- 33

Kanzog, “Der Dokumentarfilm als politischer Katechismus,” 69.

- 34

Marion Gräfin Dönhoff, “Was bedeutet die Hitlerwelle?,” Die Zeit, September 9, 1977.

- 35

Hans Esderts, “Vom Himmel herab naht er. Leni Riefenstahls Film TRIUMPH DES WILLENS im Cinema,” Bremer Nachrichten, August 24, 1972.

- 36

The dispute can be followed in a volume of files from the Federal Ministry of the Interior entitled “Auswertung von ‘NS’-Filme [sic] – Verbotsfilme,” B/106, 96609, BArch.

- 37

German Embassy to the Federal Foreign Office, 29 December 1976, B/106, 96610, BArch.

- 38

Clive Coultass (Keeper of the Department of Film at the IWM) to Dr. B. Lohmeyer (German Embassy), 22 May 1975, B/106, 96609, BArch.

- 39

The background to how this decision came about and the specific consequences it had will be explored in detail in the ‘biography’ of the film that is currently in the making.

- 40

Dr. Weber to Transit, 2 December 1973, B198, 81306, BArch.

- 41

See also Rainer Rother, Leni Riefenstahl: The Seduction of Genius (London: Continuum, 2002), 216n21. Rother overlooks the third broadcast date in 1977. The broadcast dates were checked both in the contemporary TV magazine Hörzu and with the broadcasters themselves.

- 42

Dietmar Schmidt, “Und wieder: Die NS-Filme,” epd/Ausgabe für die kirchliche Presse 45 (1974).

- 43

Information from Hans-Gunter Voigt to the project team member Alexander Zöller.

- 44

Daniel Kothenschulte, “Das blaue Irrlicht. Leni Riefenstahl wird hundert – doch wenig spricht dafür, dass man ihrer Ästhetik innerhalb der Moderne diesmal auf den Grund geht,” Frankfurter Rundschau, August 22, 2002.

- 45

Theo Fürstenau, “Der NS-Film – Darf man ihn wieder zeigen?,” epd/Kirche und Film 11 (1974), 14.

- 46

Loiperdinger, Der Parteitagsfilm, 11.

- 47

“Befund der 16mm-Kopie des Films TRIUMPH DES WILLENS, die uns Mitte November 1974 über die Transit zur Ansicht geschickt wurde” (Findings of the 16mm copy of the film TRIUMPH DES WILLENS, which was sent to us for viewing via Transit in mid-November 1974), 23 November 1974, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 10 “T.d.W.”, Stabi Berlin.

- 48

Enno Patalas, “Die schönste Freude von allen. Hart wie Riefenstahl: Erinnerungen eines Betroffenen an die Regisseurin von TRIUMPH DES WILLENS,” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, February 19, 2004.

- 49

The Munich Film Museum's copy has a length of 2.886 meters and was received in 1978. The corresponding information in Kanzog was confirmed and clarified by Stephanie Hausmann, an employee of the Film Museum, by email in May 2023. Kanzog, “Der Dokumentarfilm als politischer Katechismus,” 69.

- 50

Leni Riefenstahl to Dr. Bucher (Bundesarchiv), 16 August 1989, B198, 81307, BArch.

- 51

Leni Riefenstahl to Williard Van Dyke (MoMA), 9 June 1971; Williard Van Dyke to Leni Riefenstahl, 22 June 1971, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 448, Stabi Berlin. On July 28, 1976, she then signed a contract with Janus Films for the exploitation of her films, including TdW, not least on VHS cassettes. Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 375, Stabi Berlin.

- 52

Information from the catalog cards of the German Collection in the LoC.

- 53

Wilhelm Weiß, “Der Film der Bewegung,” in Völkischer Beobachter, March 29, 1935. Quoted in R109, I, 6449, BArch.

- 54

Loiperdinger, Der Parteitagsfilm, 11.

- 55

“Eidesstattliche Erklärung”, 2 August 1960, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 391, Stabi Berlin.

- 56

“Schule Riefenstahl. Der absolute Film,” Film-Kurier, January 25, 1936.

- 57

Riefenstahl, Memoiren, 225. The emphasis is mine.

- 58

Sarah Kozloff, Invisible Storytellers. Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988), 26.

- 59

Sworn declaration, 2 August 1960, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 391, Stabi Berlin.

- 60

Albert Speer, Erinnerungen (Berlin: Propyläen-Verlag, 1969; Berlin: Ullstein, 2005), 75. Page references are to the Ullstein edition.

- 61

Steven Bach, Leni. The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl (New York: Vintage Books, 2008), 214.

- 62

Leni Riefenstahl to Albrecht Speer, 12 October 1969, Estate of Leni Riefenstahl, 463, Stabi Berlin.

- 63

William L. Shirer, Berlin Diary. The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent 1934-1941 (New York: Knopf, 1941; Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002), 22. Citations refer to the John Hopkins UP edition.

- 64

Siegfried Zelnhefer, Die Reichsparteitage der NSDAP in Nürnberg (Nürnberg: Verlag Nürnberger Presse, 2002), 228.

- 65

Riefenstahl, Memoiren, 232.

- 66

Gisela Bock, Frauen in der europäischen Geschichte. Vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart (München: Beck, 2005), 274.

- 67

Tom Saunders, “Filming the Nazi Flag. Leni Riefenstahl and the Cinema of National Arousal,” Quarterly Review of Film and Video 22 (2016): 37.

- 68

Heinrich Hoffmann, Der Parteitag der Macht. Nürnberg 1934 (Berlin: Zeitgeschichte, 1934).

- 69

Loiperdinger, Der Parteitagsfilm, 114; Jens Eder, “Affektlenkung im Film. Das Beispiel Triumph des Willens,” in Mediale Emotionen. Zur Lenkung von Emotionen durch Bild und Sound, ed. Oliver Grau and Andreas Keil (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 2005), 107–32.

- 70

Zelnhefer, Die Reichsparteitage der NSDAP in Nürnberg, 248.

- 71

Zelnhefer, Die Reichsparteitage der NSDAP in Nürnberg, 171.

- 72

Paula Diehl, “Reichsparteitag. Der Massenkörper als visuelles Versprechen der ‘Volksgemeinschaft’,” in Bilder, die Geschichte schrieben. 1900 bis heute, ed. Gerhard Paul(Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011), 55.

- 73

Hans-Ulrich Thamer, Verführung und Gewalt. Deutschland 1933-1945 (Berlin: Siedler, 1986), 425.

- 74

[Journey of the Political Leaders from the Pinneberg district to the Reich Party Congress in Nuremberg in 1934], Abt. 2002, Nr. 128, Landesarchiv Schleswig-Holstein (LASH). I would like to thank Martin Loiperdinger for pointing me to this movie.

- 75

M 3425, Agency Karl Höffkes (AKH), URL: https://www.archiv-akh.de/filme/3425#1. In the 1980s, Höffkes had attracted attention with an illegal exploitation of TdW on VHS in the environment of right-wing extremist publishers. Johanne Hoppe, Von Kanonen und Spatzen. Die Diskursgeschichte der nach 1945 verbotenen NS-Filme (Marburg: Schüren, 2021), 218.

- 76

Ulrich Pohlmann, “‘Nicht beziehungslose Kunst, sondern politische Waffe.’ Fotoausstellungen als Mittel der Ästhetisierung von Politik und Ökonomie im Nationalsozialismus,” Fotogeschichte 8, no. 28 (1988): 20.

- 77

Wolfgang Schivelbusch, Entfernte Verwandtschaft. Faschismus, Nationalsozialismus, New Deal 1933-1939 (München: Hanser, 2005; Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 2008), 66. Citations refer to the Fischer edition.

- 78

Gerhard Paul, “Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Die visuelle Geschichte und der Bildkanon des kulturellen Gedächtnisses,” in Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Band I: 1900 bis 1949, ed. Gerhard Paul (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; Bonn: Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, 2009), 29.

- 79

Paul, “Das Jahrhundert der Bilder,” 29.

- 80

Martin Kemp, Christ to Coke. How Image Becomes Icon (Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012), 74.

- 81

Kemp, Christ to Coke, 77.

- 82

Kemp, Christ to Coke, 340.

- 83

David D. Perlmutter, Photojournalism and Foreign Policy. Icons of Outrage in International Crises (Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998), 11.

- 84

Kemp, Christ to Coke, 4.

- 85

Emmanuel Thiébot, Propaganda Hitler. Du “sauveur” au monstre, les 1000 visages du Führer (Malakoff: Armand Colin, 2022), 24.

- 86

Paul, “Das Jahrhundert der Bilder,” 29.

- 87

Kristina Oberwinter, “Bewegende Bilder.” Repräsentation und Produktion von Emotionen in Leni Riefenstahls TRIUMPH DES WILLENS (München: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2007), 107.

- 88

Heinrich Hoffmann, Der Parteitag des Sieges. 100 Bild-Dokumente vom Reichsparteitag zu Nürnberg 1933 (Berlin: Zeitgeschichte, 1933).

- 89

Anke te Heesen, Theorien des Museums zur Einführung (Hamburg: Junius, 2012), 130.

- 90

Pohlmann, “Fotoausstellungen,” 19.

- 91

Wilhelm Lotz, “Zur Ausstellung ‘Die Kamera,’” in Die Form 11, no. 8 (1933): 325.

- 92

Lotz, “Zur Ausstellung ‘Die Kamera’,” 322.

- 93

Hans-Ulrich Thamer, “Geschichte und Propaganda. Kulturhistorische Ausstellungen in der NS-Zeit,” in Geschichte und Gesellschaft 24, no. 3 (July–September 1998): 362.

- 94

Lotz, “Zur Ausstellung ‘Die Kamera’,” 325.

- 95

Diehl, “Reichsparteitag,” 52.

- 96

Riefenstahl, Hinter den Kulissen des Reichsparteitag-Films, 9.

- 97

Riefenstahl, Hinter den Kulissen des Reichsparteitag-Films, 95.

- 98

David J. Diephouse, “The Triumph of Hitler's Will,” in The Cult of Power. Dictators in the Twentieth Century, ed. Joseph Held (New York: Columbia UP, 1983), 51–76.

- 99

Eike Geisel, “Triumph des guten Willens,” die tageszeitung, December 17, 1992; quoted in Eike Geisel, Die Wiedergutwerdung der Deutschen. Essays & Polemiken (Berlin: Edition Tiamat, 2015), 160–63.

- 100

Christina Tilmann, “Triumph des Wirkungswillens,” Tagesspiegel, Dezember 3, 1998.

- 101

Robert Weixlbaumer, “Triumph ihres Willens. Die erste deutsche Ausstellung über Leni Riefenstahls Leben und Werk im Filmmuseum Potsdam,” Berliner Zeitung, Dezember 4, 1998.

- 102

Stefan Koldehoff, “Triumph des Alters. Die NS-Propagandistin Leni Riefenstahl plant in ihrem Wohnort Pöcking am Starnberger See ein eigenes Museum,” die tageszeitung, September 5, 2001.

- 103

Joshua Feinstein, The Triumph of the Ordinary. Depictions of Daily Life in the East German Cinema. 1949–1989 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002).

- 104

K.H., “Hochbetrieb in Neubabelsberg. Ergänzungsaufnahmen für TRIUMPH DES WILLENS,” Licht-Bild-Bühne, October 23, 1934.

- 105

“Des Führers Interesse am TRIUMPH DES WILLENS,” Film-Kurier, September 27, 1934; Riefenstahl,Hinter den Kulissen des Reichsparteitag-Films, 28.

- 106

Zelnhefer, Die Reichsparteitage der NSDAP in Nürnberg, 231.

- 107

Baldur von Schirach, “Zum Geleit,” in Der Triumph des Willens. Kampf und Aufstieg Adolf Hitlers und seiner Bewegung, ed. Heinrich Hoffmann (Berlin: Zeitgeschichte, 1933), 4.

- 108

Narziß Ach, Analyse des Willens (Berlin: Urban & Schwarzenberg, 1935).

- 109

Francis Courtade and Pierre Cadars, Geschichte des Films im Dritten Reich (München: Hanser, 1975), 56. Originally published as Histoire du Cinéma nazi (Paris: Éditions Eric Losfeld Le Terrain Vague, 1972).

- 110

Alfred Baeumler, Nietzsche der Philosoph und Politiker (1931; repr., Leipzig: Reclam, 1940), 47–48.

- 111

Thamer, Verführung und Gewalt, 65.

- 112

Norman Ohler, Der totale Rausch. Drogen im Dritten Reich (2015; repr., Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2023), 220–21.

Anonymous. “Des Führers Interesse am TRIUMPH DES WILLENS.” Film-Kurier, September 27, 1934.

———. “Schule Riefenstahl. Der absolute Film.” Film-Kurier, January 25, 1936.

Bach, Steven. Leni. The Life and Work of Leni Riefenstahl. New York: Vintage Books, 2008.

Baeumler, Alfred. Nietzsche der Philosoph und Politiker. Leipzig: Reclam, 1940. First published in 1931.

Barry, Iris. “Hunting the Film in Germany,” The American-German Review 3, no. 4 (June 1937): 40–45. Reprinted in East Side – West Side. Schätze aus dem Filmarchiv des MoMA. Eine Filmreihe im Kino Arsenal, 9. Mai–5. Juni 2004, edited by Eva Orbanz, 60–63. Berlin: SDK, 2004.

Bock, Gisela. Frauen in der europäischen Geschichte. Vom Mittelalter bis zur Gegenwart. München: Beck, 2005.

Bowser, Eileen. “Leni Riefenstahl and the Museum of Modern Art.” Film Comment 3, no. 1 (Winter 1965).

Brockmann, Stephen. A Critical History of German Films. Rochester, NY: Camden House, 2010.

Buñuel, Luis. Mein letzter Seufzer. Erinnerungen. Berlin: Verlag Volk und Welt, 1988.

Delage, Christian. Caught on Camera. Film in the Courtroom from the Nuremberg Trials to the Trials of the Khmer Rouge. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014.

Diehl, Paula. “Reichsparteitag. Der Massenkörper als visuelles Versprechen der ‘Volksgemeinschaft’.” In Bilder, die Geschichte schrieben. 1900 bis heute, edited by Gerhard Paul, 50–59. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2011.

Diephouse, David J. “The Triumph of Hitler's Will.” The Cult of Power. Dictators in the Twentieth Century, edited by Joseph Held, 51–76. New York: Columbia UP, 1983.

Dönhoff, Marion, Gräfin. “Was bedeutet die Hitlerwelle?.” Die Zeit, September 9, 1977.

Eder, Jens. “Affektlenkung im Film. Das Beispiel Triumph des Willens.” In Mediale Emotionen. Zur Lenkung von Emotionen durch Bild und Sound, edited by Oliver Grau and Andreas Keil, 107–32. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 2005.

Esderts, Hans. “Vom Himmel herab naht er. Leni Riefenstahls Film TRIUMPH DES WILLENS im Cinema.” Bremer Nachrichten, August 24, 1972.

Feinstein, Joshua. The Triumph of the Ordinary. Depictions of Daily Life in the East German Cinema. 1949–1989. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2002.

Fürstenau, Theo. “Der NS-Film – Darf man ihn wieder zeigen?.” epd/Kirche und Film, no. 11 (1974): 14–15.

Geisel, Eike. “Triumph des guten Willens.” die tageszeitung, December 17, 1992. Quoted in Eike Geisel, Die Wiedergutwerdung der Deutschen. Essays & Polemiken. Berlin: Edition Tiamat, 2015.

H., K. “Hochbetrieb in Neubabelsberg. Ergänzungsaufnahmen für TRIUMPH DES WILLENS.” Licht-Bild-Bühne, October 23, 1934.

Harris, Mark. Five Came Back. A Story of Hollywood and the Second World War. New York: The Penguin Press, 2014.

Heesen, Anke te. Theorien des Museums zur Einführung. Hamburg: Junius, 2012.

Hoffmann, Heinrich. Der Parteitag des Sieges. 100 Bild-Dokumente vom Reichsparteitag zu Nürnberg 1933. Berlin: Zeitgeschichte, 1933.

———. Der Parteitag der Macht. Nürnberg 1934. Berlin: Zeitgeschichte, 1934.

[Jäger, Ernst]. “Film-Kritik.“ Film-Kurier, March 29, 1935.

Kanzog, Klaus. “Der Dokumentarfilm als politischer Katechismus. Bemerkungen zu Leni Riefenstahls Triumph des Willens (1935).” In Perspektiven des Dokumentarfilms, edited by Manfred Hattendorf, 57–84. München: diskurs film Verlag, 1995.

Kemp, Martin. Christ to Coke. How Image Becomes Icon. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2012.

Koldehoff, Stefan. “Triumph des Alters. Die NS-Propagandistin Leni Riefenstahl plant in ihrem Wohnort Pöcking am Starnberger See ein eigenes Museum.” die tageszeitung, September 5, 2001.

Kothenschulte, Daniel. “Das blaue Irrlicht. Leni Riefenstahl wird hundert – doch wenig spricht dafür, dass man ihrer Ästhetik innerhalb der Moderne diesmal auf den Grund geht.” Frankfurter Rundschau, August 22, 2002.

Kozloff, Sarah. Invisible Storytellers. Voice-Over Narration in American Fiction Film. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.

Liebman, Stuart. “Triumph of the Will.” Cineaste 27, no. 4 (Autumn 2002): 46–48.

Loiperdinger, Martin. Der Parteitagsfilm TRIUMPH DES WILLENS von Leni Riefenstahl. Rituale der Mobilmachung. Opladen: Leske + Budrich, 1987.

Lotz, Wilhelm. “Zur Ausstellung ‘Die Kamera’.” Die Form 11, no. 8 (1933): 321–325.

Magliozzi, Ron. And [sic] introduction to archival records on Luis Bunuel; and the film library’s abridgement of ‘Triumph of the Will’ at the Museum of Modern Art (draft in process). New York: Film Study Center, unpublished manuscript, December 2009.

Oberwinter, Kristina. “Bewegende Bilder.” Repräsentation und Produktion von Emotionen in Leni Riefenstahls TRIUMPH DES WILLENS. München: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2007.

Ohler, Norman. Der totale Rausch. Drogen im Dritten Reich. Köln: Kiepenheuer & Witsch, 2023. First published in 2015.

Patalas, Enno. “Die schönste Freude von allen. Hart wie Riefenstahl: Erinnerungen eines Betroffenen an die Regisseurin von TRIUMPH DES WILLENS.” Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, February 19, 2004.

Paul, Gerhard. “Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Die visuelle Geschichte und der Bildkanon des kulturellen Gedächtnisses.” In Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. Band I: 1900 bis 1949, edited by Gerhard Paul, 14–39. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht; Bonn: Bundeszentrale für Politische Bildung, 2009.

Perlmutter, David D. Photojournalism and Foreign Policy. Icons of Outrage in International Crises. Westport, CT: Praeger, 1998.

Pohlmann, Ulrich. “‘Nicht beziehungslose Kunst, sondern politische Waffe.’ Fotoausstellungen als Mittel der Ästhetisierung von Politik und Ökonomie im Nationalsozialismus.” Fotogeschichte 8, no. 28 (1988): 17–31.

Riefenstahl, Leni. Hinter den Kulissen des Reichsparteitag-Films. München: Zentralverlag der NSDAP Franz Eher Nachf. GmbH, 1935.

———. Memoiren. Köln: Taschen, 2000. First published 1987 by Knaus (München).

Rother, Rainer. Leni Riefenstahl: The Seduction of Genius. London: Continuum, 2002.

Saunders, Tom. “Filming the Nazi Flag. Leni Riefenstahl and the Cinema of National Arousal.” Quarterly Review of Film and Video 22 (2016): 23–45.

Schirach, Baldur von. “Zum Geleit.” In Der Triumph des Willens. Kampf und Aufstieg Adolf Hitlers und seiner Bewegung, edited by Heinrich Hoffmann, 3–8. Berlin: Zeitgeschichte, 1933.

Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. Entfernte Verwandtschaft. Faschismus, Nationalsozialismus, New Deal 1933–1939. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, 2008. First published 2005 by Hanser (München).

Schmidt, Dietmar. “Und wieder: Die NS-Filme.” epd/Ausgabe für die kirchliche Presse 45 (1974).

Schulberg, Budd. “The Celluloid Noose.” The Screen Writer 2, no. 3 (August 1946): 1–15.

Shirer, William L. Berlin Diary. The Journal of a Foreign Correspondent 1934–1941. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2002. First published 1941 by Knopf (New York).

Sitton, Robert. Lady in the Dark. Iris Barry and the Art of Film. New York: Columbia UP, 2014.

Speer, Albert. Erinnerungen. Berlin: Ullstein, 2005. First published 1969 by Propyläen-Verlag (Berlin).

Thamer, Hans-Ulrich. Verführung und Gewalt. Deutschland 1933–1945. Berlin: Siedler, 1986.

———. “Geschichte und Propaganda. Kulturhistorische Ausstellungen in der NS-Zeit.” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 24, no. 3 (July–September 1998): 349–81.

Thiébot, Emmanuel. Propaganda Hitler. Du “sauveur” au monstre, les 1000 visages du Führer. Malakoff: Armand Colin, 2022.

Tilmann, Christina. “Triumph des Wirkungswillens.” Tagesspiegel, Dezember 3, 1998.

Weiß, Wilhelm. “Der Film der Bewegung.” Völkischer Beobachter, March 29, 1935. Quoted in R109, I, 6449, BArch.

Weixlbaumer, Robert. “Triumph ihres Willens. Die erste deutsche Ausstellung über Leni Riefenstahls Leben und Werk im Filmmuseum Potsdam.” Berliner Zeitung, Dezember 4, 1998.

Zelnhefer, Siegfried. Die Reichsparteitage der NSDAP in Nürnberg. Nürnberg: Verlag Nürnberger Presse, 2002.

Zimmermann, Aine. “Leni Riefenstahl and Propaganda Film: A Conversation with David Culbert.” Focus on German Studies 11 (2004): 281–88.

Archive Materials

Estate of Leni Riefenstahl (Nachlass 590). File folders 10, 448, 464, 876. Handschriftenabteilung, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin.

Berlin Document Center (BDC). Personenbezogene Unterlagen der SS und SA (R 9361-III). 526259 (Gienanth, Ulrich Freiherr von). Bundesarchiv (BArch) Berlin-Lichterfelde.

Records of the Office of Alien Property (RG 131). A1 251, Box 0. A1 252, Box 15. National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).