From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards

April 1 Anti-Jewish Boycott as a Visual Backdrop for Communicating Multiple Perspectives

Table of Contents

From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards

TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935)

Contested Memory

DER EWIGE JUDE (1940)

From Home Movie to Historical Document

A Living Document

Archiving the Ghetto

The Westerbork Film

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Stiassny, Noga. “From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards: April 1 Anti-Jewish Boycott as a Visual Backdrop for Communicating Multiple Perspectives.” Research in Film and History 7 (2025): 1–38. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/24048.

Introduction

The newsreel footage that shows the Boycott of Jewish businesses in Berlin on April 1, 1933, is among the most widely circulated of the newsreel footage that has contributed to shaping our understanding of motion picture-driven antisemitic Nazi propaganda. Functioning as a visual marker of the beginning of the (pre-Holocaust) Nazi persecution of European Jews, and German Jews in particular, images of this footage have over the years been edited into documentaries, reenacted in feature films, depicted in graphic novels, visual artworks, and computer games, displayed in historical exhibitions, and circulated on social media; every year, on International Holocaust Remembrance Day (January 27) and Jewish Yom HaShoah (כ״ז בניסן), Boycott images (re)appear in mainstream media, often in combination with other iconic pre-war visual material from Nazi Germany, such as images from the newsreel footage of the May 10th Book Burning – another highly cinematic event that took place in the Reich’s capital that same year.

Although American films such as HITLER’S REIGN OF TERROR (US 1934)1 and newsreel series such as MARCH OF TIME (episode “Inside Nazi Germany,” US January 1938) serve as early, pre-war examples of ‘filmed carrier material’2 appropriating original images from both these events, one of the most significant factors in establishing the Boycott footage’s iconic status was its incorporation into THE NAZI PLAN (hereinafter TNP) – a 1945 US compilation film known for exclusively using original German-produced films, newsreels, and sound records. With the Nuremberg Trials emerging as a pivotal (media-) event in the Western memorialization culture of the Holocaust, the legal validation granted to TNP by its initial screening context within the trials bestowed iconic status on the specific Boycott sequence embedded within this film, shaping the perception that this specific footage is the historical source, originating from a Nazi propaganda newsreel.3 This, in turn, served as a powerful catalyst in its circulation and (re)appropriation within post-war visual culture.

However, while the events depicted in this footage are well-known to both the scholarly community and the public, little has been done so far to trace its production origins. This oversight not only impacts the assertion that it is a Nazi original, but also affected the migration of Boycott imagery across different media objects. Adding another layer of complexity to this, as this article shows, more than one set of footage of the event exists, each with its own provenance and iconic images. Drawing on archival and historical research, film studies, memory studies, and visual history, this article aims to address this gap in the research. It presents the findings of a two-year, cross-continental research endeavor that retraced the filmic history of the Boycott sequence embedded within TNP all the way back to 1933. In the process, the article reveals that, in contrast to the prevailing perception, the 1945 Boycott sequence is, in fact, NOT original Nazi newsreel footage, but rather a curated compilation of two distinct newsreels: one by the American newsreel company Fox and the second by Paramount; the original of the latter remained buried in the archive in the US, and was only rediscovered as part of this research effort.

By analyzing the multiple perspectives and layers of information concealed within these various manifestations of the same event, and contextualizing these within the larger matrix of the April 1 Anti-Jewish Boycott, the article thus challenges our understanding of motion picture-driven Nazi propaganda: it establishes that our collective visual memory of the April 1 Boycott has not been shaped solely by the Nazi gaze, but also by other gazes (within and without the archive footage),4 some of which have been neglected in the research as a result of the complex interplay of archival accessibility, iconization, and image migration in relation to traumatic history and its visual memorialization culture.

Staging a Media Event in the New Reich’s Capital

Less than three months after Hitler seized power, the Nazis initiated their nationwide campaign against Jews in Germany. On the morning of April 1, 1933, at precisely ten o’clock, members of the Sturmabteilung (SA, a.k.a. Brownshirts or Stormtroopers) stood outside Jewish-owned shops, department stores, and the offices of Jewish professionals, deterring people from entering; holding placards that vilified Jews, they urged (non-Jewish) Germans to boycott “Jewish goods.” The Nazi leadership marketed the event as a righteous response to the anti-Nazi boycott and “atrocity propaganda” propagated by international Jewry, especially Jews in the US, aimed at tarnishing Germany’s reputation. In practice, this one-day anti-Jewish boycott followed a series of violent events at the regional level, where the marginalization of Jews could be tested in advance;5 the April 1 Boycott was a violent expression of a long process that deliberately and systematically destroyed Jewish commercial activity, scapegoating Jews for the challenging economic conditions that emerged after the Great War, within the context of a broader global economic crisis.6

Considering this, while the official date of the Boycott was chosen as a counter-reaction to the protests in New York that took place during March 1933,7 the decision to stage the Boycott specifically on April 1 – a date traditionally associated with practical jokes and hoaxes (April Fools’ Day) – carries its own symbolic meaning. Furthermore, the scheduling of the event on Shabbat (Saturday), the most sacred day of the week for observant Jews, and a day typically marked by bustling streets and mass consumption, inflicted significant financial damage on Jewish-owned businesses during one of the most profitable periods of the year and imbued the event with a theological meaning. The timing, with its proximity to Passover (Pesach) and Easter also resonates with the Passion narrative as the final hours of the German nation before its envisaged resurgence. Consequently, the chosen date underscored the antisemitic message that Jews, and Judaism, had no place in the Nazi-German public space.

The April 1 Boycott took effect simultaneously in various locations across the country. Yet, the newsreel coverage of it focused solely on Berlin. This spotlight on Berlin within the newsreel medium highlights the city’s symbolic significance as the new Reich’s capital and the home of a vibrant Jewish community (one third of all Jews in Germany), particularly in terms of the number of Jewish-owned businesses and Jewish professionals.8 The visual focus on Berlin was also a result of the city’s media landscape. The early decades of the 20th century witnessed Berlin emerge as a media hub, with cultural and economic collaborations between Hollywood and German cinema, and the active presence of representatives from international news agencies, such as the American companies Fox, Paramount, and Hearst.9 Alongside international players, local studios also played a significant role, including Ufa, Deulig-Tonwoche, Bavaria Film AG, and the photographic agency of Heinrich Hoffmann (Hitler’s official photographer).10 The high density of media experts in Berlin prompted the Nazis to strategically exploit the cityscape as the ideal backdrop against which to stage a spectacle. In other words, the event in Berlin was specifically designed to capture the attention of a broad audience.

Accordingly, the presence of both local and foreign media agencies gave the event in the Reich’s capital a performative dimension, staged deliberately for the camera. This is reflected, for example, in the famous dynamic shot of a truck with Brownshirts driving around the city, actively propagating the boycott against the Jewish population. The performative quality of the event is also apparent in still-photographs taken in Berlin, particularly in official press-release photographs. One such example depicts a group of Brownshirts parading along Leipziger Straße in Berlin’s Mitte district, holding placards that read “Germans, defend yourselves against Jewish atrocity propaganda / buy only at German shops!” in English, and “Deutsche, verteidigt Euch gegen die jüdische Greuelpropaganda, / kauft nur bei Deutschen!” in German. The documentation of the procession in one of the most popular shopping areas of the era was intended to convey the official Nazi version of the event, that is, to manipulatively present the Boycott as proceeding in an orderly and disciplined manner.11 The bilingual nature of the placards further underscores the event’s potential to reach beyond Germany.12

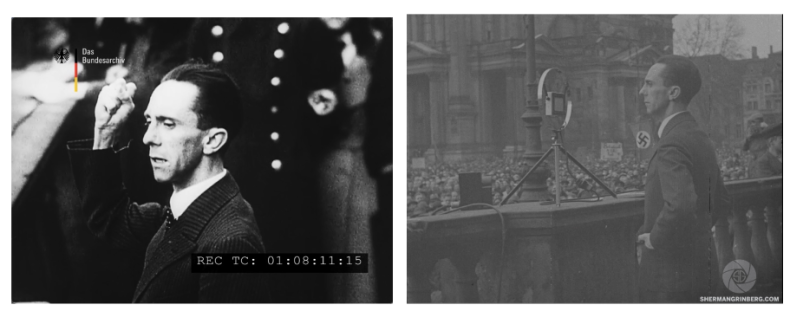

The orchestrated and performative dimension of events in Berlin culminated in an afternoon speech by Joseph Goebbels, Reich Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, and Gauleiter (district leader) of Berlin. Delivered to a massive crowd at Berlin’s Lustgarten, near the former Stadtschloss (Berlin City Palace), and captured on camera, Goebbels presented the official Nazi narrative of the event as a defensive act, conducted in a disciplined manner. He incited the audience to exclude Jews from the public-economic sphere, accusing them of spreading false propaganda against Nazi Germany; with his rhetoric and grandiose hand gestures Goebbels clearly distinguished between ‘the local Aryans’ and ‘the Jews,’ identifying the Jewish people as a morally and racially inferior ‘Other.’

In line with Goebbels’ speech and the bilingual placards, the Berlin Boycott was designed as a spectacle to convey a ‘glocal’ (both global and local) message with two distinct audiences in mind: the domestic (Jewish and non-Jewish) German population, and non-German-speaking viewers, especially Americans. Showcasing the Nazi’s power in their newly established capital, created by and for the so-called German Volksgemeinschaft – an idealized, unified ethno-national community fighting against external and internal enemies – the display served as a trial balloon, sent up to gauge international reactions to their antisemitic policies and the crusade against an ‘un-German spirit.’ This message was also mediated through aesthetic means, such as the distinct typography used on the placards themselves: clean and simple in English, and a more traditionally ‘authentic’ Gothic script for the German audience.13

Under these circumstances, images of the April 1 anti-Jewish Boycott in Berlin were already regarded as emblematic at the time and quickly spread both within and beyond Nazi Germany, before the full implementation of the regime’s censorship measures; in fact, as Thomas Doherty argues in his book Hollywood and Hitler 1933–1939 (2013), even when Nazi censorship of the visual realm was at its peak, “[n]either boycotts on one side nor blockades on the other were airtight: films had a way of slipping over the borders."14

THE NAZI PLAN (1945): The Boycott Is Established as an ‘Original Nazi Source’

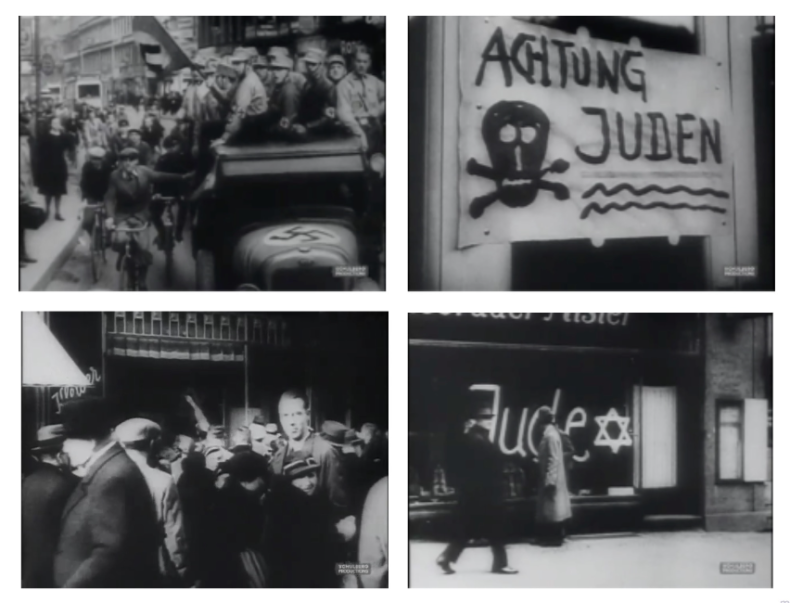

Alongside images capturing the general atmosphere in Berlin during the Boycott, several specific ‘performative images’ have gained particular popularity as the subjects of image migration. Among these are the shot of a moving truck with Brownshirts; a zoom-in on a sign with a skull and crossbones and a textual warning against ‘the Jews’ (“Achtung / Juden”); a Brownshirt painting a Star of David on a shop window as a large crowd watches; and a shot of a closed shop window marked with a Star of David and the word “Jude” (Jew) in large letters (Fig. 3). This last shot gained immediate iconic status, so that in 1938, the MARCH OF TIME reenacted the shot from inside the closed shop (episode “The Refugee: Today and Tomorrow”); to this day, this reenactment is sometimes mistakenly identified as original.15

Used as visual placeholders marking the beginning of the Nazi persecution of European Jews, particularly German Jews, from a retrospective viewpoint that anticipates the horrors to come, such images represent what Tobias Ebbrecht defines as "migrating images:" historical images from the Nazi era that, through their repeated representations and circulation in post-1945 popular culture, form specific (visual) codes and conventions for the telling and retelling (as well as representing and reinterpreting) of stories from the Holocaust, including its overarching ‘master narrative’ of antisemitism, Jewish genocide, Nazi crimes, and the liberation of the camps.16 These patterns, Ebbrecht argues, have been so efficiently engrained in our collective visual memory that they can easily become detached from their historical origins, gaining the potential to migrate into contexts that are vastly different from those in which they were originally created.17 The documentary film THE NAZI PLAN demonstrates precisely this point.

TNP was compiled by Budd Schulberg and other US military personnel under the supervision of Brig. General William J. Donovan and was screened as evidence at the International Military Tribunal in Nuremberg on December 11, 1945. The film is known globally for its exclusive use of German source material, such as official newsreels and other Nazi propaganda footage shot by Reich officers and filmmakers (including figures like Leni Riefenstahl, whose work is also discussed in this issue). The Boycott footage is presented immediately following a segment of Goebbels’ Lustgarten speech, under the chapter title “Opening of the Official Anti-Semitic Campaign 1 April 1933” (part of the larger segment “Part 2: Acquiring totalitarian control of Germany. 1933–1935”). This films-within-a-film approach was leveraged by the prosecution to create the impression that the Nazi leadership was, in essence, convicting themselves through their own images.18 This had such a profound pedagogical impact on the courtroom audience that Hollywood producer Darryl F. Zanuck proposed making a shorter English version of the film for distribution in theatres shortly after its Nuremberg screening – a task eventually carried out by Ray Kellogg in 1946.19

As the Nuremberg Trials became an (media-) event of significant magnitude, the Boycott sequence edited into TNP emerged as the dominant visual frame of reference for our collective visual memory of this historical event, and for our understanding of Nazi antisemitic propaganda disseminated through the medium of newsreels. The perception that the 1945 Boycott footage is original, Nazi-produced newsreel footage has become so deeply embedded in public consciousness that it is effectively considered historical fact: TNP’s entry in the US Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) encyclopedia specifically states that the filmmakers “used only German source material, including official newsreels.”20 The same perception is also evident in other public sources, such as Wikipedia,21 and is prevalent among filmmakers, echoed, for example, in Sandra Schulberg’s film (in collaboration with Josh Waletzky) NUREMBERG: ITS LESSON FOR TODAY (US 2009).22

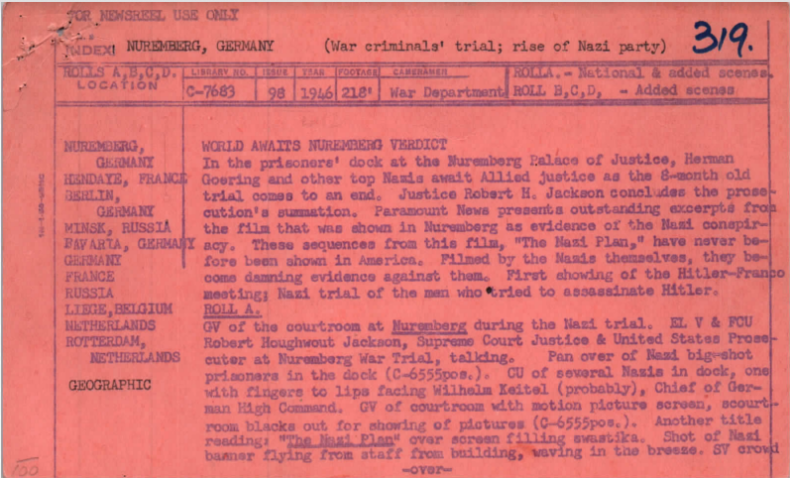

A catalogue card from 1946 found at the Sherman Grinberg Film Library further supports this framing (Fig. 4). According to this archive document, “outstanding excerpts from the film [TNP] that was shown in Nuremberg as evidence of the Nazi Conspiracy,” all of which were “filmed by the Nazis themselves,” were shared after the war with the Paramount newsreel company (and possibly also with other newsreel companies). The document even goes a step further, emphasizing that these excerpts “have never before been shown in America.” These materials include the 1945 Boycott sequence.

In reality, the truth is much more complex, with several original versions of the event in existence, two of which found their way into TNP, though neither qualifies as an ‘official Nazi newsreel.’ Furthermore, American audiences were already familiar with Boycott imagery well before TNP, not only from its appropriation into films and newsreels such as HITLER’S REIGN OF TERROR and MARCH OF TIME, but also because one of these two sources had already been shown in America by mid-April 1933. The most effective way to unravel the origins of TNP’s Boycott sequence is thus through a comparative analysis of the original versions from 1933, with a special focus on the origins of the film’s most iconic migrating images.

Multiple Original Sources

1) Deulig-Tonwoche: Antisemitic Perspective

The German production company Deulig-Tonwoche produced their own newsreel version of the April 1 anti-Jewish Boycott, which stands out as the sole (known) original footage in complete alignment with the Nazis’ official narrative of the event. According to a document from the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, this newsreel was shown in German cinemas on April 5, 1933.23 The Deulig newsreel allocated a mere minute and a half to the Berlin Boycott, within a sequence of varied local and international news (including the Vatican’s Easter ceremony, the Sanriku earthquake in Japan, and the Oxford-Cambridge rowing competition). The limited duration dedicated to the Berlin-Boycott, shorter than the coverage of other stories, seems to reflect an attempt to downplay the event’s significance (in terms of its documentation).

The footage itself follows the same attempt, presenting a ‘normal’ image of a bustling city, accompanied by a narration in German. The reporter covers the event in hindsight (from the standpoint of April 2), framing it as a German response to the alleged ‘atrocity campaign’ against Nazi Germany, which took place ‘peacefully’ and in an ‘orderly manner’ (“Ruhe und Ordnung”). This suggests that the filmed material was not captured on the actual day of the Boycott, but shortly before or after it, with the voiceover added later in the studio.

Antisemitic messages are not openly discussed verbally, but they are nonetheless visually conveyed using stereotypes rife with internal contradictions.24 The footage completely omits any direct visual representation of the small Jewish-owned shops that were affected by the boycott, focusing instead on Jewish-owned department stores, large-scale businesses, and retail companies (like Tietz, Leiser, and Wertheim), propagating the false impression that Jews wielded control over the German economy.25 Such accusations were further reinforced by the inclusion of counter-images from an anti-Nazism demonstration held in New York a few days prior to the Boycott. These images prominently displayed ‘typical’ depictions of Jewish Rabbis standing in a group, insinuating the existence of a global Jewish conspiracy, drawing parallels with the antisemitic forgery The Protocols of the Elders of Zion’ In that vein, the juxtaposition of this newsreel story with images of Pope Pius XI conducting the Easter ceremony symbolically portrayed Jews as a modern embodiment of the mythological traitor, emphasizing the theological dimension of the event and its timing.

In addition to the appropriation of religion-oriented antisemitic iconography, the footage also conveys a Völkisch heritage narrative of continuity. The date, April 1, is not only close to Passover/Easter but also coincides with Bismarck’s birthday. Wishing to portray the Nazis, especially Hitler, as the ‘natural’ successors of Bismarck – the ones to restore Germany’s honor, the complete Deulig newsreel sequence concludes with shots of jubilant celebrations held across Berlin on the day before the Boycott (March 31) and on the evening of April 1; while the Jewish population of Germany was under attack, the Nazis celebrated.

Against this backdrop, while the Deulig footage primarily targeted a domestic audience, its message also aimed to resonate within the international community, intended to provoke blanket coverage that could potentially spark similar anti-Jewish actions beyond the borders of Nazi Germany. This becomes evident through the footage’s consistent focus on the bilingual placards urging a boycott of ‘Jewish businesses,’ including a shot capturing the SA procession on Leipziger Straße – a shot subsequently appropriated into HITLER’S REIGN OF TERROR and the ÉCLAIR JOURNAL (FR 1936), before migrating into other media objects. Curiously, however, the Deulig footage did not find its way into the TNP Boycott sequence screened at Nuremberg. Whether due to a lack of familiarity with the material, archival chaos following the war, or a deliberate decision to sidestep visually manipulative footage that avoids depicting the attacks on Jewish-owned shops, the TNP filmmakers did not rely on the sole German newsreel source that prominently featured Nazi antisemitic propaganda.

2) Fox Tönende Wochenschau: Ambivalent Perspective

Another original Boycott newsreel source was produced by Fox Tönende Wochenschau. While this footage was integrated into TNP, it constitutes only a segment of the complete 1945 Boycott sequence. Furthermore, not all the filmed material from the Fox footage was eventually included in the final 1945 TNP Boycott sequence. Nonetheless, due to the widely held belief that the 1945 version of the Boycott footage originated from a Nazi newsreel source, there is often a (false) tendency in (German) film historiography to attribute the complete 1945 sequence to Fox. This could be rooted in the absorption of the company into the Deutsche Wochenschau (alongside with Ufa-Tonwoche, Deulig-Tonwoche, and Emelka-Tonwoche) in the early 1940s; the Deutsche Wochenschau played a key role in the Nazi propaganda apparatus, with much of its material used as incriminating evidence in post-war tribunals and trials. However, although Fox was clearly subject to the rigorous supervision and constant surveillance of the Reich Ministry of Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda, it is worth acknowledging that, in 1933, Fox Tönende Wochenschau was still operating under Fox Movietone News, the American film and newsreels company known for having the “best field operation in Germany” during that period.26

Moreover, the connection between the 1945 version, often referred to as the ‘Nazi original’, and Fox may also have been influenced by other factors. The 1946 production of TNP, which was created on behalf of Twentieth Century Fox may have played a role. Two additional factors might include the company’s pioneering sound technology (a signature of Fox News during those years)27 as well as the fact that MARCH OF TIME (well known for its newsreel coverage of the Boycott) had no cameramen in Berlin, and therefore relied entirely on Fox Movietone’s newsreels (including outtakes) for their library stock.28 That said, no Fox footage is known to have survived in US archives, and no evidence suggests it having been screened in the US.29 According to the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, which possesses a copy of the Fox newsreel, this footage was shown in German cinemas relatively close to the event.30

The footage itself, 56 seconds of filmed material, opens with the iconic shot of the moving truck, showing chanting Brownshirts fervently calling for an anti-Jewish Boycott – the same shot that opens TNP’s Boycott sequence. The camera then transitions to the crowded streets, emphasizing the smeared shop windows, Brownshirts blocking shop entrances, and the placards urging the public not to buy from Jews. Amid this city panorama, the footage singles out a selection of performative images, all of which are present in TNP and are still regarded as iconic migrating images. These include the famous shots of a Brownshirt, back to the camera, painting a large Star of David on a shop window, surrounded by a crowd of spectators, and the shot reenacted in MARCH OF TIME which shows a shop with the Star of David and the word “Jude” marked on its window, in stark contrast to the casual pedestrians strolling nearby. Goebbels’ Lustgarten speech was recorded as a separate sequence; certain segments were also incorporated into TNP, and subsequently, screened during the trials. Other familiar migrating images from TNP, such as the iconic “Juden” sign with the skull and crossbones, are absent from this newsreel footage.

A notable aspect of the footage, also highly evident in the TNP sequence, is the apparent camera-awareness of both Brownshirts and passers-by; some look directly into the lens, while others pose excitedly with antisemitic propaganda placards.31 This special attention to gazes enhances the complicity of the photographed subjects and underscores the dual nature of that day’s activities: both organized institutional action and spontaneous grassroots movement. This participation-driven narrative is further reinforced within the TNP Boycott sequence by an additional shot taken from the moving truck – a shot that is absent from the original Fox newsreel footage but may potentially have originated from unused materials. Serving as the closing shot of the 1945 version, this second truck shot mirrors the footage’s opening shot. This palindromic structure frames the visual narrative of the TNP sequence with an artistic touch that intensifies the sensation of a tumultuous event unfolding simultaneously in different locations across the city, strengthening the likelihood that editing was employed in the compilation process.

The emphasis on the participation of the photographed subjects and the chaotic atmosphere on the streets is unsettling and may suggest a viewpoint that could be interpreted as anti-Nazi, especially when considered retrospectively, from a post-Nuremberg standpoint. However, certain shots – such as the moving truck shot, captured from a second truck, or the coverage of Goebbels’ speech from the stage, including a close-up of his face (Fig. 6) – would likely have required special permission from Nazi censors to be filmed and published, perhaps even requiring Goebbels’ personal involvement.32

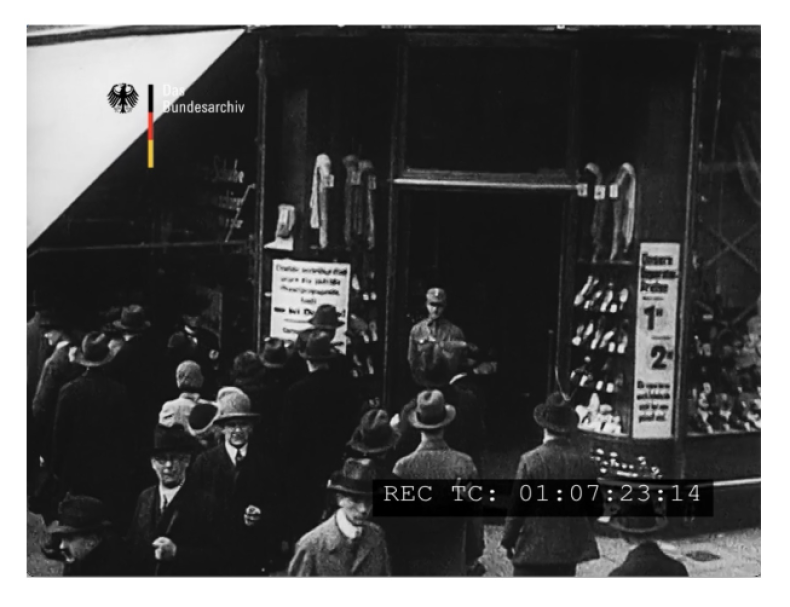

There are also other instances in which the footage aligns completely with the official Nazi narrative. This alignment is evident, for example, in the opening credit, which explicitly states (in German) that “GERMANY IS DEFENDING ITSELF AGAINST ATROCITY PROPAGANDA / To fight the fake news that is spread abroad / a boycott against Jewish shops was initiated across the country.”33 Another visual manifestation of the Nazi narrative within the footage is a shot showing a Brownshirt blocking the entrance to Leiser – a German retail company significantly affected by the Nazi’s anti-Jewish economic policy (Fig. 7). Despite his presence, the shop (likely at Oranienstraße 34 in Kreuzberg) appears to be open, with customers visibly exiting it. This shot depicts the event as a so-called defensive measure executed in a ‘peaceful’ and ‘disciplined’ manner. However, given that the Fox newsreel footage was used as evidence during the Nuremberg Trials, both the shot of the open shop and the credit shot were intentionally left out of TNP in 1945. The decision to omit these specific shots indicates the filmmakers’ awareness of their historical responsibility, especially within the context of the legal proceedings; they were careful not to include images that could potentially mitigate the violent and oppressive character of the April 1 Boycott, without the necessary contextual interpretation.

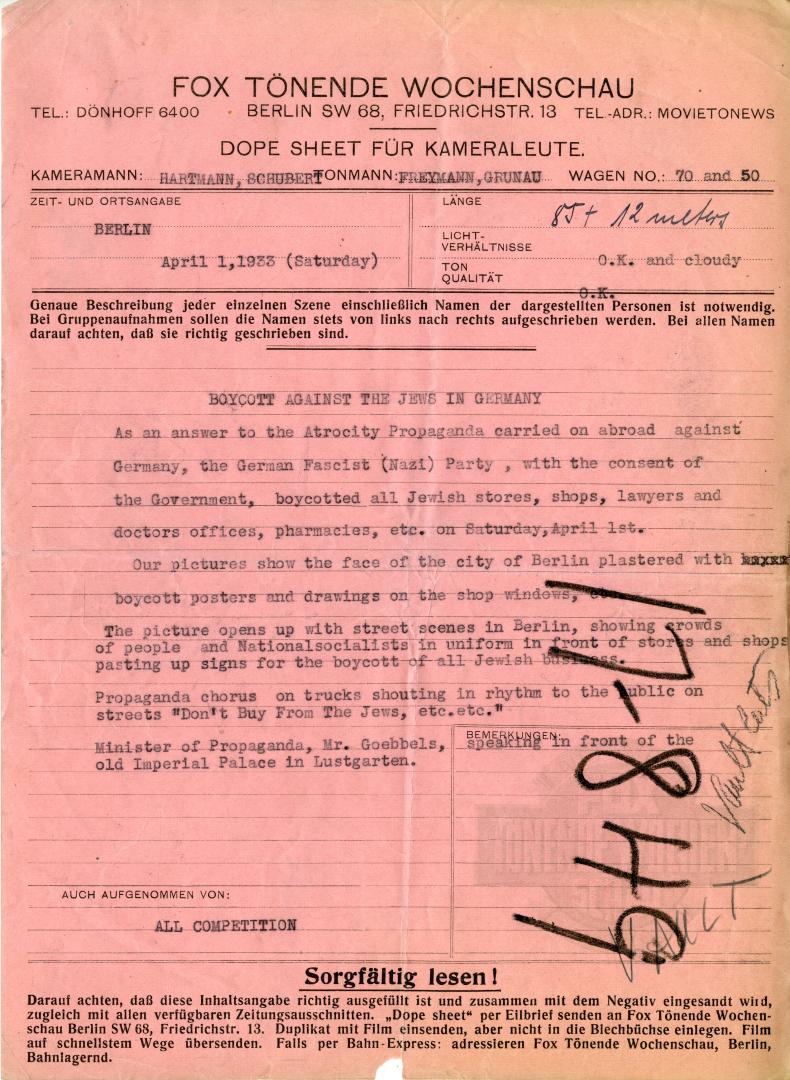

Seeking to please different stakeholders simultaneously – the company’s office in New York on the one hand, and the German regime on the other – the Fox footage inherently embodies an ambivalent perspective. This perspective is not only evident in the footage itself but is also mirrored by the original record (“dope sheet”) that was sent from Germany to the Fox offices in New York at the beginning of April 1933 (Fig. 8). This dope sheet (17-849), written in English on German stationery paper, refers to the Nazi party as “fascist,” revealing a clear anti-Nazi perspective. At the same time, however, the Boycott event is described as a measure taken by Germany “as an answer to the Atrocity Propaganda carried on abroad against Germany,” aligning with the official Nazi narrative.

The dope sheet also provides some valuable insights into the production context of the footage itself. It reveals, for example, that the footage was captured by two crews: wagon number 70, with cameramen Hartmann and Schubert, and wagon number 50, with soundmen Freymann and Grunau; it is possible that the teams split differently, with one camera person and one sound person in each wagon (i.e., Hartmann and Freymann, and Schubert and Grunau). The document does not specify whether the two crews filmed the entire day (i.e., both the streets and Goebbels’ Lustgarten speech), or if each crew was solely responsible for covering a specific event. While the presence of two soundmen implies that a sound recording setup was used on-site, it is most likely that the ambient sound was added at a later stage, during the editing process, before the newsreel arrived in German cinemas.

From the document, we learn that the filming conditions that day were “O.K. and cloudy,” and that the total length of material sent to New York was 85 + 12 meters (a figure that may not necessarily represent the total quantity filmed on site). The dope sheet also provides a detailed account of the material filmed that day: street scenes in Berlin, propaganda chorus on trucks, and Goebbels’ Lustgarten speech. The order of shots in the written description differs from what is seen in TNP, however. This discrepancy serves as a clear indication that the Fox footage underwent editing during the compilation process of TNP.

Navigating between different (often conflicting) interests in New York and Germany simultaneously, the Fox footage thus presents a complex picture of the Boycott event. On the one hand, traces of criticism against the Nazi regime can be discerned. On the other hand, it is hard to ignore the alignment with the official Nazi version of the event, raising the possibility of an ad hoc collaboration between Fox Movietone News and the Nazi regime, with some of the visual content possibly sourced from a Nazi ‘image pool’ rather than being filmed directly by the Fox crews themselves. In fact, already in the early 1930s, accusations were made against Fox for being a “carrier for more Hitler propaganda than any other American newsreel company.”34 For its part, however, Fox Movietone News firmly denied any deal with Nazi Germany to “propagandize Hitlerism.”35 Furthermore, the phrase “ALL COMPETITION” on the bottom left of the dope sheet is open to interpretation but could imply the presence of other competitive newsreel companies in the city, or alternatively, a form of collaboration among these companies. This suggests some exchange and sharing of film resources between various newsreel companies, perhaps even sending duplicate materials to editorial staff abroad, leading us to the second source used by the TNP filmmakers.

3) Paramount News: Anti-Nazi Perspective

If the first two sources were shown in German cinemas and thus aligned, to varying extents, with the Nazi framing of the April 1 event, the third source – the second to be utilized by TNP – takes a clear anti-Nazi stance and an American viewpoint. Created by Paramount News, another well-established American newsreel producer operating in Germany during the 1930s, this newsreel footage reached New York City as early as April 1933, contradicting the claim made in the 1946 catalogue card that these images had not been seen before in America (Fig. 2). This contradiction could have arisen due to the chaotic state prevailing in American archives during the war years, the omission of copyright credits, the early reinforcement of the perception that TNP exclusively used German-produced material, people simply forgetting or not seeing the original footage (unless they were in a Paramount house or dedicated news junkies), or even a calculated self-branding marketing strategy. Regardless of the underlying reason, a cinema review published in Variety on April 18, 1933, confirms that the Paramount newsreel was screened at the Trans-Lux Theater, at 58th Street and Madison Avenue, the previous weekend, precisely two weeks after the Anti-Jewish Boycott was executed in Berlin;36 according to the reviewer (Tom Waller, who appeared under the nickname “Waly”) who was present at the theatre, “first definite screen news of the German boycott was credited to Paramount.”37

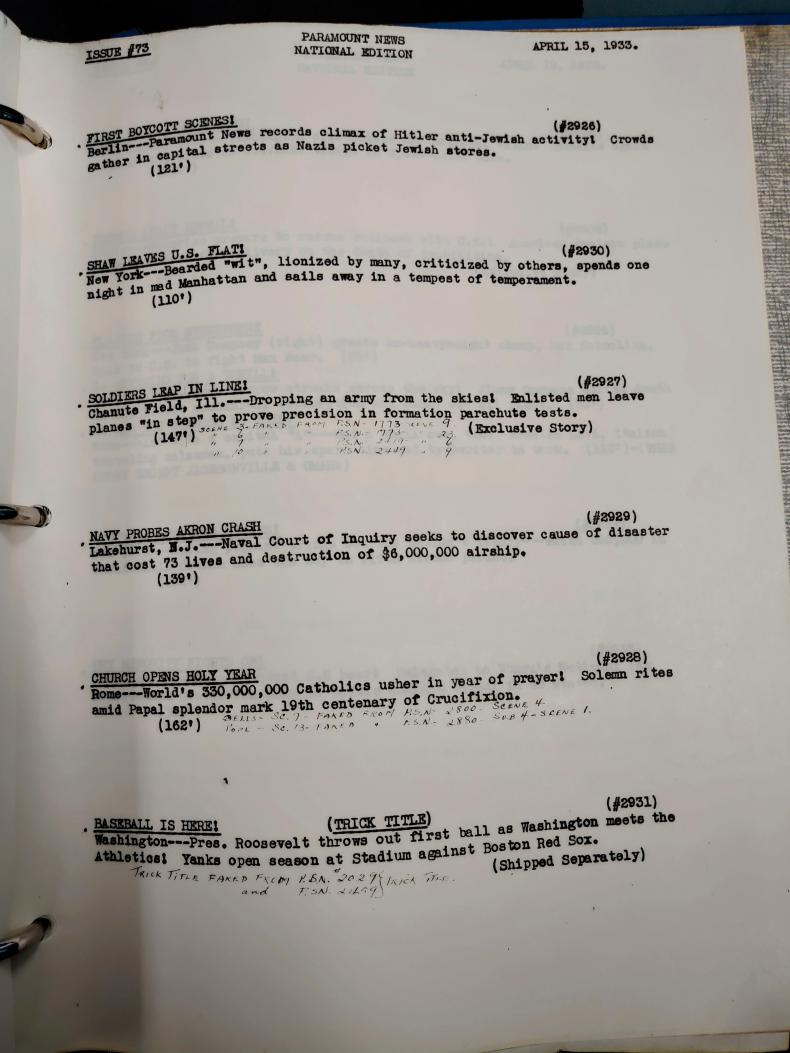

In addition to this first-hand eyewitness account, other documents that provide support for this assertion can be found in the Sherman Grinberg Film Library (Fig. 9). These official release sheets were sent to American movie theatres by the Paramount office on April 15, 1933, with the distribution of the newsreel depicting the Nazi boycott, titled “FIRST BOYCOTT SCENES!” (Story no. 2926).

Moreover, additional documents at the Sherman Grinberg Film Library reveal that the material was also shared with the Pathé newsreel production company, marking the beginning of the footage’s circulation (Fig. 10).

What precisely does the material encompass? For decades, this question has been answered primarily in relation to the Boycott sequence embedded within TNP, which, as previously demonstrated, also includes material originating from the Fox footage. In the rare instances where TNP’s Boycott sequence is not identified as a Nazi-originated source affiliated with Fox, it is often attributed to Paramount.38 This attribution is also visible on the Sherman Grinberg Film Library’s website,39 and if even the Grinberg Library, which owns the Paramount archive, fell into the ‘trap’ set by TNP, it is unsurprising that this (mis)information has been propagated to other visual archives, such as Getty Images.40

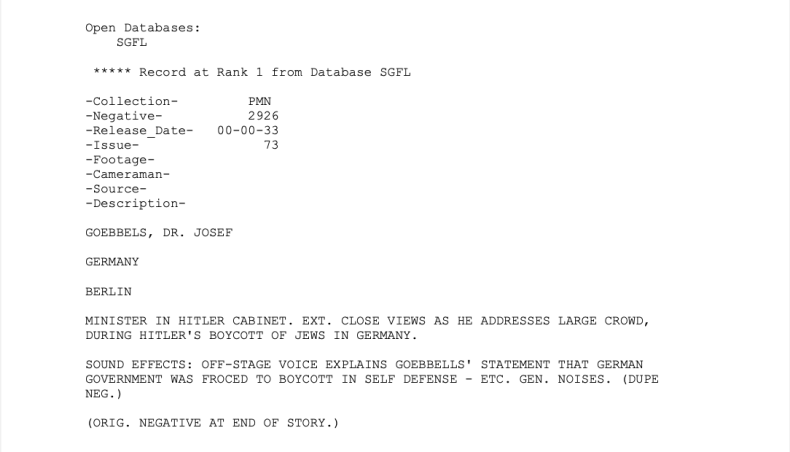

According to the Variety review, the Paramount newsreel includes a (unidentified) “talking reporter” who “interpreted posted signs and editorialized about the situation while the crowd was shown milling about Berlin.”41 This information is further supported by Pathé’s finding aid document, which references an “OFF-STAGE VOICE” explaining Goebbels’ argument that the German regime was “FORCED TO BOYCOTT IN SELF-DEFENSE” (Fig. 11).

However, the document also reveals another intriguing detail: it indicates the transmission of the original negative, which bears the same story number as Paramount’s (#2926). In fact, the transmission involves duplicate negatives: one copy remained silent, while the other included sound. Following this information, the archive team at the Sherman Grinberg Film Library undertook the task of retrieving, locating, and scanning the original Paramount negative, which had remained buried and forgotten in the archive for decades, and is presented here for the first time since the 1930s:

As opposed to both the Deulig and Fox footage, the Paramount footage, originally recorded without sound, targeted an audience outside Nazi Germany, primarily Americans (it is highly likely that sound was added later, in America). Thus, right from the beginning, it establishes in fluent English a critical stance towards the emerging Nazi regime in Germany. The credit slide explicitly associates the event with Hitler and depicts it as a blatant anti-Jewish activity (highlighted by an exclamation mark). The German people are portrayed as complicit, gathering in the streets of Berlin to witness the Nazis picketing Jewish(-owned) stores. This critical perspective is further conveyed through the footage itself. The very first image displayed on the screen is one of the most iconic migrating images of the April 1 Boycott, which also appears in the TNP Boycott sequence: a zoom-in on the “Juden” sign with the skull and crossbones on the door of the Café Unter den Linden. Accompanying this image is an interpretative commentary from the reporter who directly addresses English-speaking cinemagoers by translating the German sign (“Achtung Juden”): “Beware, Jews! This grisly sign on the door of the internationally known café-bar on Unter den Linden warns Germans that the restaurant is managed by Jews, hence, under boycott.”

As this message is communicated, the camera slowly zooms out with a dissolve effect, offering a broader spatial context: it captures the café-bar as passers-by look directly at the camera; for a moment, a child even jumps in front it.42 Visually, the emphasis on the sign introduces another critical dimension to the portrayal of the Nazi regime. The amateurish hand-painted sign stands in stark contrast to the ‘perfectionist’ Nazi aesthetics43 seen in the official printed placards held by individuals and displayed around the city (indeed throughout Germany) during that day.44 This contrast highlights a violent event, with official support and backing, carried out in the streets by hooligans. In Berlin the sign served as a symbol of Jews being associated with “the poison of antisemitism flowing through the Third Reich.”45 In contrast, in America it functioned as a warning sign of the Nazi poison. It is therefore only to be expected that the TNP filmmakers utilized this material to emphasize the Boycott as events coming both from above and from below. To enhance the documentary’s effect, however, the reporter’s explanation was left out during editing.

The Paramount reporter consistently guides the audience through the day’s events, undermining the Nazi framing of the Boycott as possessing Ruhe und Ordnung. At one point, the camera even captures a street brawl between a Brownshirt and a passer-by as the latter attempts to enter a boycotted shoe shop. When the Brownshirt realizes that the scene is being recorded, he shouts at the filmmaker and chases him away. This sequence is presented in two distinct shots, arranged in reverse order, and separated by another shot, possibly to navigate Nazi censorship (Fig. 13). Nonetheless, audio in German was added in the studio, featuring the customer’s voice requesting entry into the store. This scene was also edited into TNP, once again without the sound recording.

Intermixed with these images, the camera focuses on the bilingual placards hung across the city – images that were not appropriated by TNP filmmakers. Furthermore, in addition to the events unfolding in the streets, the footage also captures the gathering of masses at the central event of that day: Goebbels’ speech at Berlin-Lustgarten. This section is particularly intriguing for two reasons. Firstly, the close-up of Goebbels, taken from the stage to his left, from the same angle where the Fox team is standing (Fig. 14). This (further) strengthens the possibility of material being shared between the teams or sourced from a common ‘image pool’ that both companies had access to.46

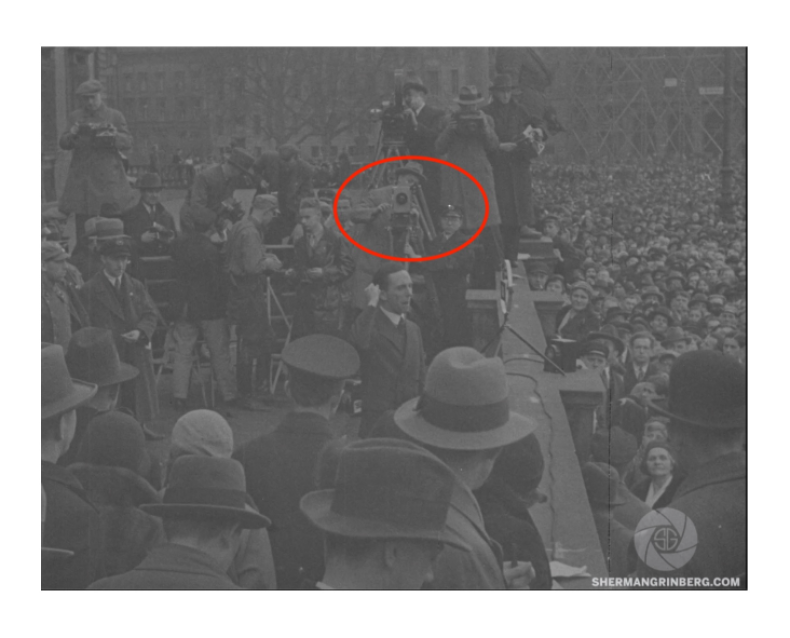

Secondly, apart from this particular image of Goebbels, the speech is filmed from the right side of the stage, suggesting that the Paramount film crew were stationed on the stage, but on the opposite side to the Fox film crew(s). For a moment, their camera even captured multiple camera and sound teams, all of them authorized to record the event, possibly including the Fox team(s) (Fig. 15). This shot exposes the ‘fourth wall’ of the Nazi spectacle; paradoxically, it is conceivable that this is the very reason for the exclusion of this sequence from TNP.

The Paramount newsreel footage, capturing “images that would forever after conjure the first stirrings of the Nazis in power,”47 was dispatched from Germany to America immediately after the Boycott event. After undergoing minor editing, the footage was distributed to theatres to serve as a warning against the rise of Nazism in Europe. Consequently, although certain images may have originated from external sources, the Paramount footage – in contrast to Fox’s and Deulig’s footage – does not present Nazi propaganda, but rather serves as anti-Nazi propaganda material.

The Nazis, aiming from the outset for an internationally reported spectacle with a ‘glocal’ message, were displeased with how the Boycott event (as well as the May 10 Book Burning) was portrayed outside of Germany. As a result, beginning in the latter half of 1933, they intensified censorship controls. A case in point is the absence of visual representation of the torched synagogues during the 1938 ‘November Pogrom’ (Kristallnacht) in the newsreels of that era.48 Whether an anti-Nazi propaganda perspective or practical considerations (such as archive accessibility) influenced the decision, the TNP filmmakers chose the soundless version of the Paramount newsreel, appropriating only selected images from it.

Conclusion: THE NAZI PLAN’s Boycott Footage Is a Post-1933 Curated Sequence

Even though the Nazis conveyed their antisemitic messages far more through newsreels than through feature films, there is still a lack of scholarly analysis of this important medium – a critique articulated by David Bankier twenty years ago and still valid today.49 With this in mind, this article compels us to re-evaluate our understanding of Nazi antisemitic propaganda disseminated through newsreels. Presenting a novel genealogy of the April 1 Anti-Jewish Boycott newsreel footage, it traced the migration trajectory of this footage from its appearance in the compilation film THE NAZI PLAN, often referred to as ‘Nazi original’ footage, back to its roots in 1933. Within this genealogical quest, the article exposed the existence of a plurality of original newsreel footage: by Deulig, Fox, and Paramount; notably, the Paramount footage, which remained concealed in archives for nearly nine decades, has been brought to light through this research. These primary sources are situated and scrutinized within the larger context of the April 1 Anti-Jewish Boycott event, and its physical and symbolic migration, revealing how the event (including its newsreel coverage) was used as a visual backdrop for communicating multiple, often contested, viewpoints, as early as 1933.

As a result, contrary to the prevailing perception that TNP exclusively used German-produced materials, this genealogical excavation unveiled a different narrative: the 1945 Boycott sequence was curated from newsreel footage produced by Fox and Paramount; the only (known) footage in complete alignment with antisemitic Nazi propaganda was excluded (Deulig). The resulting curated sequence was edited to project the Nazi cinematic gaze as an initial emblem of the regime’s atrocities, albeit from an American vantage point, in full awareness of the catastrophic outcomes of the war. This curatorial act fuses diverse perspectives into a juridical-visual strategy, aiming to incriminate the Nazi regime, while highlighting the complicity of the German people – a stance congruent with the charges presented at Nuremberg. Yet, while this genealogy focuses on uncovering the origins of TNP’s Boycott sequence, its completeness remains subject to future discoveries. The possibility of uncovering additional versions looms on the horizon, such as the Pathé newsreel footage that incorporated Paramount materials, as well as versions hitherto unknown, from Berlin and beyond (including from entities such as Hearst, Universal, and Bavaria Film AG).

Acknowledgement

This article – the second in a three-part exploration of the Boycott footage* – is the product of research conducted within the framework of the DFG project “(Con)Sequential Images – An Archaeology of Iconic Film Footage from the Nazi Era.” I would like to express my gratitude to my colleagues in this project, Alexander Zöller and Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, for sharing their knowledge of Nazi footage with me. I would also like to thank Greg Wilsbacher (Newsfilm and Military Collections at the University of South Carolina), and Lance Watsky (Media Archives & Licensing at the Sherman Grinberg Film Library), for their archival help and valuable insights. I am particularly indebted to Christoph Kreutzmüller and Thomas Doherty for the significant feedback they provided, which was of great assistance in contextualizing this research.

* The first part, a multi-modal project consisting of both an article and a video essay, was also published in this journal (see: Kreutzer and Stiassny, “Digital Digging”). The video essay received an Honourable Mention at the Adelio Ferrero Film Festival (2021) and won several nominations in the British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound Best Video Awards (2021).

- 1

My thanks to Thomas Doherty for drawing my attention to this example. See Thomas Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler 1933–1939 (New York: Columbia University Press, 2013), 59–66 and 94–5.

- 2

For the definition of this term, see the Introduction to this volume.

- 3

Ironically, the same act often leads the public to view this source as an authentic documentation of the antisemitic persecution of Jews under Nazi rule.

- 4

Evelyn Kreutzer and Noga Stiassny, “Digital Digging: Traces, Gazes, and the Archival In-Between,” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces 4 (2022): 1–13, https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18100.

- 5

Avraham Barkai, From Boycott to Annihilation. The Economic Struggle of German Jews, 1933–1943 (Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1989), 26–35; Christoph Kreutzmüller, Final Sale in Berlin: The Destruction of Jewish Commercial Activity, 1930–1945 (New York: Oxford, England: Berghahn, 2015); Saul Friedländer, Nazi Germany and the Jews. Volume 1: The Years of Persecution 1933–1939 (London: Phoenix Giant, 1997),17–25; Sibylle Morgenthaler, “Countering the Pre-1933 Nazi Boycott against the Jews,” The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 36, no. 1 (1991): 127–149, https://doi.org/10.1093/leobaeck/36.1.127.

- 6

Kreutzmüller emphasizes that the term ‘boycott’ must be approached “as a primary source term.” This is because, contrary to its original meaning of nonviolent political protest, the April 1 event aimed to annihilate Jewish commercial activity. Building on this insight, I use ‘Boycott’ (capitalized) to signify the documentation of this specific historical event. See Kreutzmüller, Final Sale in Berlin, 8.

- 7

Ibid., 104.

- 8

Ibid., 2.

- 9

Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler; Ben Urwand, The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013).

- 10

While many photos from the event in Berlin are identified with Hoffman, he was not in the city on that day but had followed Hitler (who made sure to distance himself from the event) to southern Germany. Thus, these photographs were taken by his employees.

- 11

Kreutzmüller, Final Sale in Berlin, 105–106 (specifically footnote no. 64 in Kreutzmüller’s text).

- 12

Kreutzmüller draws attention to at least one more instance where evidence suggests that Brownshirts had assembled the night before the Boycott (the night of March 31) in front of the closed gate of a Jewish-owned department store in order to pose undisturbed for the camera of press photographer Fritz Steppuhn, holding bilingual placards. Ibid., 108–9.

- 13

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Visual Design in German-Jewish Newspapers, 1933–1938 (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2021) (Hebrew).

- 14

Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler,72.

- 15

It is worth mentioning that HITLER’S REIGN OF TERROR also incorporates reenacted scenes.

- 16

Tobias Ebbrecht, “Migrating Images: Iconic Images of the Holocaust and the Representation of War,” Shofar 28, no. 4 (2010): 90–2.

- 17

Ibid.

- 18

This strategy was further reinforced by the screening of extensive audio-visual records captured by the Allies during the liberation of the Nazi camps (e.g., George Stevens’ NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMPS, US 1945).

- 19

This film also includes the Boycott footage, albeit with some shots edited out. See Christian Delage, Caught on Camera. Film in the Courtroom from the Nuremberg Trials to the Trials of the Khmer Rouge (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2014), 123.

- 20

US Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) Encyclopedia, accessed August 26, 2023, https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/gallery/film-presented-as-evidence-the-nazi-plan; https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/timeline-event/holocaust/1942-1945/the-nazi-plan; https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/film/the-nazi-plan-antisemitic-campaign.

- 21

“The Nazi Plan,” Wikipedia, accessed August 26, 2023, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Nazi_Plan.

- 22

“NUREMBERG FILMS - How history was made into film and film into history,” Schulberg Productions, accessed August 26, 2023, https://www.nurembergfilm.org.

- 23

The document is available online: Bundesarchiv, “Wochenschauen und Dokumentarfilme, 1895-1950” (reviewed by Peter Bucher), footage number 66, accessed August 26, 2023, https://www.bundesarchiv.de/DE/Content/Downloads/Finden/Film/wochenschauen-dokfilme.pdf?__blob=publicationFile. See also David Bankier, “Signaling the Final Solution to the German People,” in Nazi Europe and the Final Solution, eds. David Bankier and Israel Gutman (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2003), 18. Despite the claims made in the document, this version may have completed its editing by April 5 and been screened a few days later.

- 24

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Visuelle Kommunikation in antisemitischen Diskursen,” Visual History (31.05.2021), ZZF – Centre for Contemporary History, https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2216.

- 25

Morgenthaler, “Countering the Pre-1933 Nazi Boycott,” 127–49.

- 26

Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler,287.

- 27

Joseph Clark, News Parade: The American Newsreel and the World as Spectacle (Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 26–7.

- 28

Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler,243.

- 29

It is worth mentioning that other footage produced by Fox cameramen in Germany in the same year did make it to US screens (e.g., “German Army Hails Hindenburg and Adolf Hitler,” story 17–713, in volume 6, release number 56 of Fox).

- 30

Bundesarchiv, “Wochenschauen und Dokumentarfilme, 1895–1950,” footage number 2600. According to the document, this newsreel was released on April 5, 1933. However, it is also possible that its editing was completed, and it was ready for dissemination on that date.

- 31

Kreutzer and Stiassny, “Digital Digging.”

- 32

Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler,91–5.

- 33

DEUTSCHLAND WEHRT SICH GEGEN DIE GREUELHETZE /Zur Bekämpfung der im Ausland verbreiteten falschen Meldungen /wurden im ganzen Land die jüdischen Geschäfte boykottiert”.

- 34

Daily Worker, June 11, 1934, page 5. (I am grateful to Thomas Doherty for sharing the original source with me).

- 35

Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler, 93. See also Urwand, The Collaboration, 146; William Alexander, Film on the Left: American Documentary Film from 1931 to 1942 (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981), 40.

- 36

Doherty suggests an initial screening date of April 14, although the 15th is also a plausible option. Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler,285.

- 37

Tom Waller a.k.a. Waly, “Newsreels - Translux,” Variety (Tuesday, April 18, 1933): 20, accessed August 26, 2023, https://archive.org/details/variety109-1933-04/page/n123/mode/2up?view=theater&q=boycott. See also Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler,94. Once again, I am grateful to Thomas Doherty for sharing the original source with me, and for assisting me in identifying the reviewer’s name.

- 38

It is also intriguing to note that Doherty, the sole scholar who cites the eyewitness source, and whose work significantly informed this study, stumbled into the same ‘pitfall’: he describes the Paramount footage by referencing Fox’s shot of “brownshirts marauding in trucks” – a detail not mentioned in the Variety review at all. See Ibid.

- 39

“World War II: German anti-Semitism,” Sherman Grinberg Film Library, accessed August 26, 2023, https://filmlibrary.shermangrinberg.com/?s=file=58116.

- 40

“6 Boycott 1933 Videos,” Getty Images, accessed August 26, 2023, https://www.gettyimages.de/video/boycott-1933?assettype=film&family=editorial&phrase=boycott%201933&sort=best.

- 41

See endnote no. 37.

- 42

For more on this moment see Kreutzer and Stiassny, “Digital Digging.”

- 43

I am grateful to Christoph Kreutzmüller for drawing my attention to this point.

- 44

For example, Bundesarchiv, accessed August 26, 2023, https://www.bild.bundesarchiv.de/dba/de/search/?yearfrom=&yearto=&query=Plak+003-020-017.

- 45

Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler,285.

- 46

The Deulig newsreel footage includes sound, some of which is credited to Paramount.

- 47

Doherty, Hollywood and Hitler,94.

- 48

Ibid., 291. See also Lawrence Baron, “Kristallnacht on Film: From Reportage to Reenactments, 1938–1948,” The Space Between: Literature and Culture 1914–1945, vol. 16 (2020). https://scalar.usc.edu/works/the-space-between-literature-and-culture-1914-1945/vol16_2020_baron; Tobias Ebbrecht, “Bilder, die es nicht geben dürfte. Film- und Fotoaufnahmen zum Novemberpogrom 1938 und ihre spätere Verwendung,” Filmblatt 44 (Winter 2010/2011): 36–53; Jörg Müllner (author), Bernhard Schulder (editing), Konrad Waldmann (camera), “Antisemitismus 1938 - Verbotene Bilder vom Pogrom,” Terra X History, November 5, 2023, YouTube video, 00:18:15, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=947o4sd9xYc.

- 49

Bankier, “Signaling the Final Solution,” 18.

Alexander, William. Film on the Left: American Documentary Film from 1931 to 1942. New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1981.

Bankier, David. “Signaling the Final Solution to the German People.” In Nazi Europe and the Final Solution, edited by David Bankier and Israel Gutman, 15–39. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2003.

Baron, Lawrence. “Kristallnacht on Film: From Reportage to Reenactments, 1938-1948.” The Space Between: Literature and Culture 1914–1945, vol. 16 (2020). https://scalar.usc.edu/works/the-space-between-literature-and-culture-1914-1945/vol16_2020_baron.

Barkai, Avraham. From Boycott to Annihilation. The Economic Struggle of German Jews, 1933–1943. Hanover and London: University Press of New England, 1989.

Clark, Joseph. News Parade: The American Newsreel and the World as Spectacle. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press, 2020.

Delage, Christian. Caught on Camera. Film in the Courtroom from the Nuremberg Trials to the Trials of the Khmer Rouge. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2014.

Doherty, Thomas. Hollywood and Hitler 1933–1939. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias. “Bilder, die es nicht geben dürfte. Film- und Fotoaufnahmen zum Novemberpogrom 1938 und ihre spätere Verwendung.” Filmblatt 44 (Winter 2010/11): 36–53.

–. “Migrating Images: Iconic Images of the Holocaust and the Representation of War.” Shofar 28, no. 4 (2010): 86–103.

–. Visual Design in German-Jewish Newspapers, 1933–1938. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2021. (Hebrew)

–. “Visuelle Kommunikation in antisemitischen Diskursen.” Visual History (31.05.2021). ZZF – Centre for Contemporary History. https://doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok-2216.

Friedländer, Saul. Nazi Germany and the Jews: Volume 1: The Years of Persecution 1933–1939. London: Phoenix Giant, 1997.

Kreutzer, Evelyn and Noga Stiassny. “Digital Digging: Traces, Gazes, and the Archival In-Between.” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces 4 (2022): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18100.

Kreutzmüller, Christoph. Final Sale in Berlin: The Destruction of Jewish Commercial Activity, 1930–1945. New York: Oxford, England: Berghahn, 2015.

Morgenthaler, Sibylle. “Countering the Pre-1933 Nazi Boycott against the Jews.” The Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 36, no. 1 (1991): 127–149. https://doi.org/10.1093/leobaeck/36.1.127.

Urwand, Ben. The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2013.

Waller, Tom a.k.a. Waly. “Newsreels – Translux.” Variety (Tuesday, April 18, 1933): 20. Accessed August 26, 2023,

https://archive.org/details/variety109-1933-04/page/n123/mode/2up?view=theater&q=boycott.