Archiving the Ghetto

An Unfinished Propaganda Film of the Warsaw Ghetto, 1942

Table of Contents

From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards

TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935)

Contested Memory

DER EWIGE JUDE (1940)

From Home Movie to Historical Document

A Living Document

Archiving the Ghetto

The Westerbork Film

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Zöller, Alexander. “Archiving the Ghetto: An Unfinished Propaganda Film of the Warsaw Ghetto, 1942.” Research in Film and History 7 (2025): 1–41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/24047.

Throughout May and for the first two days in June 1942, German cameramen shot extensive 35mm footage in the Warsaw Ghetto. Filming concluded shortly before the commencement of the so-called Großaktion Warschau – the deportation of hundreds of thousands of the ghetto’s inhabitants to the death camp at Treblinka, where they were murdered.1 The close temporal connection of the filming to the coordinated mass-depopulation of the ghetto and killing of its inhabitants has raised questions as to whether the Nazis sought to shoot film which they would not have been able to obtain shortly afterwards, and whether their interest in doing so extended to other, later stages of the annihilation of European Jewry.2 Despite its obvious Nazi origin and ideological purpose, the resultant ghetto footage, an unfinished film, has emerged as one of the most widely used audio-visual materials about the Holocaust. As a film saturated with the gaze of the perpetrator, this puts it in a peculiar category of films made by the Nazis yet drawn upon until today to illustrate historical events.

The unfinished film has been preserved in two distinct fragments: a rough cut running to approximately sixty minutes, and an additional thirty minutes of supplemental footage, referred to throughout this text as the Restmaterial (residual material). In addition to these fragments, a 16mm Agfacolor film shot in the ghetto at the same time by one of the German cameramen was discovered in the 1990s. The Restmaterial has since been used in a considerable number of projects, of which Yael Hersonski’s documentary A FILM UNFINISHED (DE/IL 2010) is of particular significance. For the first time, Hersonski took into consideration the entirety of the surviving footage, contrasting the rough cut with shots from the Restmaterial as well as textual sources to lay bare many of the scenes that were staged and arranged for the camera. Since both the rough cut and the Restmaterial passed through different archival institutions, were discovered independently from each other, and were used by filmmakers at different times, a closer look at their respective archival whereabouts is warranted. In keeping with the project’s focus on the provenance and historical context of the film materials investigated during its initial three-year phase, this text will delineate the archival ‘lives’ of both 35mm fragments before discussing some aspects and problems encountered in the appropriation of the footage.

Production Background

There is limited evidence that the project may have been launched by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi Minister of Propaganda. On April 27, 1942, Goebbels spoke to Hitler about the ‘Jewish question’, noting Hitler’s unrelenting stance toward the issue. Goebbels also recorded that Heinrich Himmler, the head of the SS, was “currently engaged in resettling the Jews from the German cities to the ghettos in the east.” “I have arranged for extensive film footage to be shot there. We will have great need of this material for the future education of our people.” 3 If the meeting with Hitler did indeed result in Propaganda Kompanien (PK, propaganda companies) cameramen being dispatched to the Warsaw Ghetto, the response was swift: filming in Warsaw commenced on May 2, 1942. The PK team sent from Berlin at least partly consisted of soldiers of the so-called Propaganda-Einsatz-Abteilung – a rapid-response force of the PK recently set up in Berlin to focus on emerging situations or to undertake special assignments on short notice.4 Hans Juppenlatz, one of the PK cameramen of the ghetto film, was assigned to the Propaganda-Einsatz-Abteilung during his deployment in Warsaw.5 While shooting film footage in the ghetto from May 2 to June 2, 1942, the PK team was instructed by local representatives.

Later, in summer 1942, Goebbels may have watched part of the resultant footage. On August 23, 1942, his diary records: “A number of horrible films are being shown to me from the ghetto in Warsaw. The conditions there are impossible to describe. Jewry is unmasked here in all clarity as a plague spot upon humanity. This pestilence must be eliminated, using whatever means necessary, if humanity is not to succumb to it.”6 The close temporal proximity to the filming in the Warsaw Ghetto makes it likely that Goebbels indeed watched part of the extant footage, and possibly the rough cut as it exists today. If the film project was indeed ordered by Goebbels, it certainly was not an isolated event, nor unusual. Ever since the outbreak of the war, the Propaganda Ministry and, at times, the Minister himself had been issuing so-called Propaganda-Weisungen (propaganda directives) to the Wehrmacht, to procure specific audiovisual material for the current or future needs of Nazi propaganda. For example, on September 8, 1939, the Propaganda Ministry issued such an order to the PK Bildberichter (photographers) in Poland requesting photographs on the subject of “The Polish Jews,” specifically “Jewish types of both sexes of different ages / Jewish professions / Jewish customs / Jewish filth,” to be published in the Eher Verlag’s NSDAP-affiliated propaganda magazine Illustrierter Beobachter.7

While some animosity prevailed between the Wehrmachtpropaganda (WPr) department at the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht (OKW, Armed Forces High Command) and the Propaganda Ministry, these directives were routinely carried out as a matter of course. Shortly before the outbreak of World War II, Goebbels had been unsuccessful in his endeavor to install a system of civilian correspondents that would handle Germany’s wartime propaganda. Instead, the Wehrmacht had prevailed in setting up a strictly military scheme: rather than being ‘embedded correspondents’ attached to military formations, all members of the Propagandakompanien were given a rank and uniform, received basic military training, and most importantly were drafted as regular combatants of the Wehrmacht, making them subordinate to military orders and the law of war. The Wehrmacht had opted for this tight control out of long-standing distrust in civilian war correspondents, which it felt had produced subpar and disloyal results during World War I. Nevertheless, preference was given to professionals – trained cameramen and career photographers – even if they were not members of any Nazi organization. When this reservoir of civilian film and camera experts had dried up, the Wehrmacht recruited reporters from the circles of the German amateur film movement, again without putting too much of a focus on their political convictions. This resulted in a highly diverse group of individuals manning the PK, ranging from dedicated Nazis to opponents of the regime, comprising all shades of ideological and moral ambiguity. Propaganda directives appear to have been Goebbels’ inroad into this military system, which preferred professionalism over ideological conviction: while the Wehrmacht had broad control over the drafting, training and deployment of the PK, the Propaganda Ministry could interject at any point to influence personnel decisions or to enforce its own reporting requirements. The Propaganda-Weisungen are evidence of the PK’s two-fold mandate: to document the war in authentic photographs and film footage, if prudent, yet also to fulfill specific needs of Goebbels’ propaganda apparatus, even if it meant staging photographs or recreating entire scenes on film. These two spheres were not contradictory. The PK cameramen, the so-called Filmberichter, were routinely instructed not to stage footage, for fear that such falsifications could negatively impact the effectiveness and credibility of German newsreel propaganda. Guidance issued to the Filmberichter as part of their training, the so-called Twelve Commandments, stipulated that “You are to avoid staging combat footage, for it may appear inauthentic and puts at risk the reputation of the [PK] cameramen.”8 Yet at the same time no such adherence to ‘authenticity’ prevailed whenever a particular subject was to be illustrated and exploited to maximum effect. The PK coverage of the ghettos in Poland in both film and photography is a striking example for this attitude where the desired end justified all available means.9

Against this backdrop, caution is essential when gauging the ‘authenticity’ of the ghetto film. From particular scenes in both the rough cut and the Restmaterial, as well as from diary entries of the ghetto’s inhabitants commenting on specific phases of the shooting, it is obvious that individual shots and even entire segments were arranged for the camera, with inhabitants of the ghetto forcibly recruited as involuntary performers. Coerced extras sometimes can be seen breaking the fourth wall by looking straight into the camera and even by smiling in an ostensibly distressing situation, thus negating the intended message of the shot. However, these instances, understandably found in the Restmaterial more frequently than in the rough cut, should not prompt us to dismiss the entire footage as ‘staged’. Street scenes of beggars, of the dead and dying, and of emaciated bodies being buried without ceremony in mass graves, would hardly have required staging: they were an everyday reality of the ghetto. As such, the film does provide several authentic, if carefully selected and composed, glances at the reality of the ghetto. As with many media products of the PK, glimpses of reality alternate with deliberate forgeries – a challenge repeatedly encountered in PK films as well as the vast body of surviving PK photographs, which significantly impacts their value as a historical source.10

The inauthentic nature of the filming was fully understood by the inhabitants of the ghetto, who recorded their observations. Adam Czerniakow (1880-1942), the Chairman of the Judenrat (Jewish Council) in the Warsaw Ghetto, repeatedly commented on the German filming activities in his diary. On May 3, 1942, he wrote: “At 10 the film crew from the Propaganda Office arrived and proceeded to take pictures in my office. A scene was enacted of petitioners and rabbis entering my office, etc. Then all paintings and charts were taken down. A nine-armed candlestick with all candles lit was placed on my desk.”11 On May 5, he noted: “The film crew is still much in evidence. They are filming both extreme poverty and the luxury (coffeehouses). The positive achievements are of no interest to them.”12 On May 15, the PK crew shot footage in Czerniakow’s apartment and again scenes were enacted for the camera.13 On May 19, Czerniakow noted that the PK crew ordered copious food at a Jewish restaurant and demanded that a ‘party’ be arranged the following day; “The ‘ladies’ are to wear evening dresses.”14 Rokhl Auerbakh (1903-1976), a writer, essayist and historian who had been interned in the Warsaw Ghetto, was keenly aware of the intention of the Nazi filmmakers – to make a film that would humiliate the Jews by reinforcing well-established anti-Semitic stereotypes –, yet she saw unintended merit in the recording of film footage:

Let them film! Let them film as much as possible! So a filmed documentation will remain of the situation brought upon a community of four times 100,000 Jews! They have the ability to create such a document. The editing and commentary are unimportant. They should leave a sneak view of the Jewish passerby on the crowded streets in the movie. […] They should all be commemorated; the droves of beggars, the people of yesterday slowly dying from the hardships and starvation in the closed ghetto. And another one, the main one – they should add the German participants in this drama. They are the lead actors in this play.15

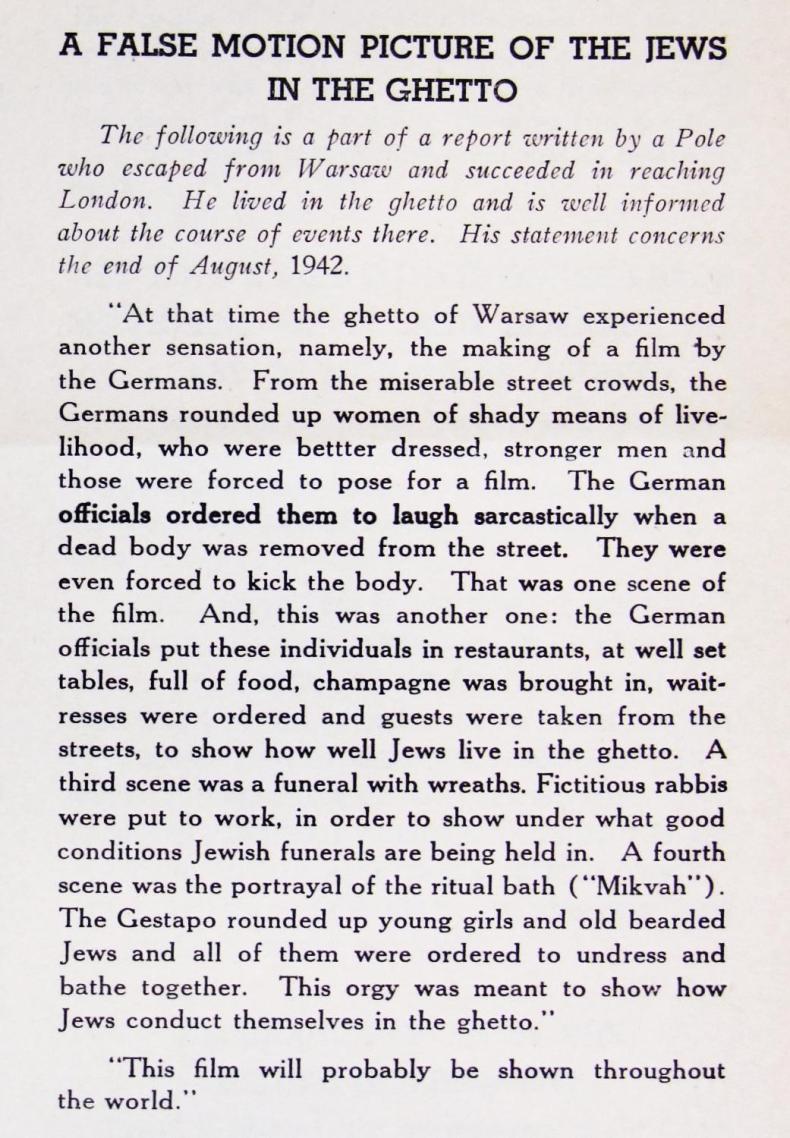

Within months of the filming having wrapped, knowledge about the film project was also disseminated abroad through the Jewish resistance organizations. In March 1943, The Ghetto Speaks, a circular published in New York by the American Representation of the General Jewish Workers’ Union of Poland, published a short notice about a “False motion picture of the Jews in the ghetto,” seizing on the inauthentic nature of the film.

Similarly, The Black Book of Polish Jewry, a 400-page report issued by the American Federation for Polish Jews that was sponsored by luminaries such as Eleanor Roosevelt and Albert Einstein reported on the film: “The Germans are said to have made an anti-Jewish film based on the conditions in the Warsaw ghetto: the well-being of the rich, the dirt in the proletarian homes, scenes of orgy, smuggling, etc.”16 Perhaps even more than the notice published in The Ghetto Speaks, this encapsulates the apparent intent of the filming very accurately: the bourgeois apartments of seemingly wealthy inhabitants of the ghetto were to be contrasted with squalid living quarters, and their inhabitants equally were to be portrayed in direct contrast. While no documents have been preserved that would provide us with an outline or concept of the film, its subjects strongly resemble the topics and implications of earlier PK reports from the ghetto. A striking example is found in a multi-page article published in the summer of 1941 by the Berliner Illustrirte Zeitung, then the German illustrated magazine with the largest circulation in Europe. Titled “Juden unter sich” (“Jews among themselves”), it, too, sought to portray actual or purported differences between affluent and impoverished Jews in the ghetto, driving home the anti-Semitic message that even in captivity Jews would lack in solidarity, looking only after their own benefit.17 But unlike earlier PK reports, the 1942 film also sought to portray Jewish customs such as circumcision, the mikveh (ritual bath), a yeshiva (a Rabbinic literature school), as well as burial practices, including the unceremonial burial in mass graves of victims who clearly died from disease or starvation as a direct result of the horrific living conditions in the ghetto. It has been theorized that this particular interest, a kind of anthropological gaze of the perpetrators which sought to document ‘the Jews’ and their traditions and practices along the lines of established Nazi stereotypes, was prompted by the foreseeable inability to procure such footage. With the Großaktion Warschau, as with the deportation and extermination of Jews from other major ghettos in Poland and Eastern Europe in general, available options to shoot such film material soon dwindled. If this assumption is accurate, it would point to the knowledge of the film’s originators about the ongoing genocide and to an intent to document and memorialize the ghettoization stage of the Holocaust while possible.18

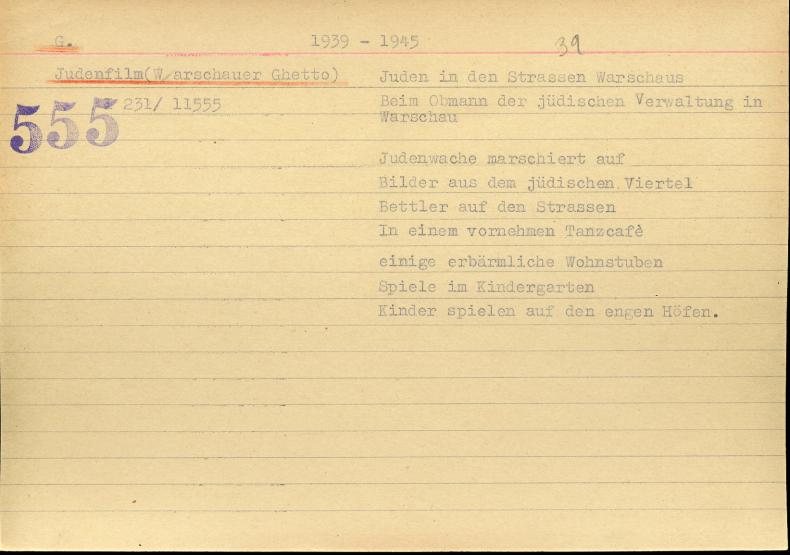

What happened to the film footage after it was recorded? Being PK material, it was probably sent to Berlin through the PK’s courier channels, much like other footage shot for the newsreels, and the negatives were developed at the Tesch film laboratory in Berlin-Johannisthal under an exclusive contract with the Wehrmacht.19 After this a rough cut was edited by an unknown entity, either by PK functionaries or directly at the Propaganda Ministry.

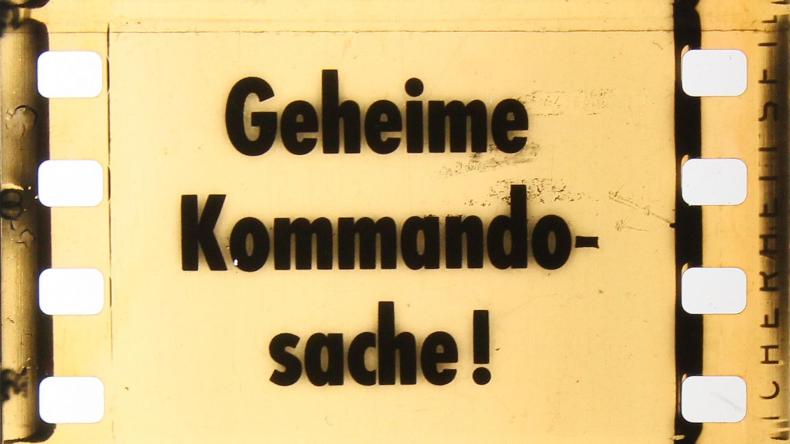

At some point during this process, the Restmaterial and, most likely, the entirety of the footage was classified Geheime Kommandosache, a classified information category used by the Wehrmacht as well as by civilian authorities of the Nazi state. This may or may not have been an unusual step: the PK routinely shot restricted footage deemed unsuitable for public release. Restricted footage was embargoed by the censors and given the status Archivwert, indicating archival value: it was not to be published.20 Almost the entirety of PK camera negatives, as well as a corresponding cache of dupe positive prints, each containing millions of meters of 35mm film, perished in nitrate film fires at the very end of the war. This makes reliable inferences as to any special status of the ghetto film difficult.21

During the editing of the rough cut, the numbers ‘13397’ and ‘13399’ were written on the starting frames in grease pencil and scratched into the perforation. It is very probable that they are so-called KA-Nummern (KA = Kopierauftrag, copy order), running numbers under which new PK footage was developed by the Tesch film laboratory in Berlin. KA numbers started being issued with the outbreak of the war in September 1939 and were also used to censor newly processed PK footage as well as to catalog, archive, and retrieve the film material at the Reichsfilmarchiv. Toward the end of the war, this numbering system had reached around 33,000 individual PK film reports. KA numbers 13397 to 13399 are an approximate match to numbers issued around spring and summer 1942.22 As such, we can assume that the Warsaw Ghetto footage was processed and handled much like other PK footage, shortly after it had been recorded. In the extant nitrates held by the Filmoteka Narodowa (FINA) in Warsaw, the KA numbers clearly were also used in the editing of the reels – they are repeated at the beginning of new reels or where parts from different KA numbers have been spliced together.23 The typical length of a single, uncut PK camera negative was sixty meters of 35mm film, fitting the standard cassette of the hand-held Arriflex cameras used by the Filmberichter. Arriflex cameras can be seen both in the rough cut and in the Restmaterial.

For unknown reasons the editing process remained unfinished. Perhaps it was sufficient as it was if the idea was only to screen some of the footage for the Propaganda Minister. If there ever was any notion of publicly screening the footage in wartime, this was abandoned: it was to be a film for the archive. Conceivably this had been the intention all along. In his memoirs, Fritz Hippler (1909-2002) briefly addresses the Propaganda Ministry’s efforts to procure and preserve film footage of Jews during the various stages of persecution and even beyond their annihilation. In doing so, the Ministry was far from alone in pursuing such documentation efforts.24 The unfinished film was deposited at the Reichsfilmarchiv. Originally a department of the Reichsfilmkammer, the archive had become part of the Propaganda Ministry in 1938. In 1939 a so-called PK-Filmstelle was set up as an archive-within-the-archive that dealt exclusively with PK film footage. Its premises were at Tempelhofer Ufer 17 in Berlin-Kreuzberg.25

Postwar Rediscovery I: Rough Cut

The first fragment of the film to enter public consciousness after 1945, and indeed the collective visual memory, were specific scenes from the rough cut. Around 1954, the East German filmmakers Andrew (1909-1979) and Annelie Thorndike (1925-2012) were given unprecedented access to the collections of the former Reichsfilmarchiv. Prior to the creation of the East German State Film Archive (Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR, SFA), which in 1955 would formally take over the Reichsfilmarchiv’s vaults in Babelsberg, the Thorndikes began inspecting large amounts of film for their upcoming compilation film DU – UND MANCHER KAMERAD (GDR 1956). Tracing the history of Germany from the imperial era to the early 1950s, the film would be edited from countless newsreels, documentary films, and snippets of archival footage.

For months a team of assistants screened films from the vaults of the former Reichsfilmarchiv in Babelsberg. In doing so, they chanced upon film cans containing the ghetto footage.26 At this time, parts of the rough cut had already suffered from nitrate decomposition and could only be copied using a specially developed single-step, frame-by-frame process.27 In the end only one minute, framed by the voice-over as “images kept secret from the German people,” was edited into the film: young Jewish boys are seen being searched by German policemen and forced to drop the turnips they had attempted to smuggle into the ghetto. The sequence is an odd choice as it clearly was staged for the camera. Its inclusion in the film followed an internal dispute: the cutter, Ella Ulrich, had vehemently opposed the inclusion of footage from the Allied liberation films, considering piles of corpses in the liberated concentration camps a disparagement of the victims. When the ghetto film was found, Andrew Thorndike selected footage from this source instead.28

The Thorndikes’ incorporation of a one-minute sequence from the rough cut did not immediately lead to the ghetto film gaining prominence as an important archive source. This was brought about in 1960 when the German-Swedish filmmaker Erwin Leiser (1923-1996) was doing research at the SFA for his compilation film DEN BLODIGA TIDEN (SE/DE 1960). At the time, the GDR’s State Film Archive did not know it held any elements of the ghetto film; it was once more discovered by chance in boxes under an entirely different title. When watching the footage, Leiser immediately decided to include it in his film.29 The global success of Leiser’s film, released internationally as MEIN KAMPF, constitutes a major vector in the dissemination of the ghetto film. It was picked up in short succession by filmmakers in several countries and was shared by the SFA with other film archives through permanent loan agreements. Early, notable uses include Jerzy Bossak’s documentary short REQUIEM DLA 500 TYSIĘCY (REQUIEM FOR 500,000, PL 1963), Frédéric Rossif’s ambitious documentary about life in the Warsaw Ghetto, LES TEMPS DU GHETTO (THE TIMES OF THE GHETTO, FR 1961), the BBC production WARSAW GHETTO (GB 1965), and Lionel Rogosin’s GOOD TIMES, WONDERFUL TIMES (US 1965). These films are characterized by an expansion of the material selected from the available footage. While Leiser had limited his choice of scenes from the rough cut to just a few minutes, Frédéric Rossif’s LES TEMPS DU GHETTO makes extensive use of the material. The same applies to the BBC production WARSAW GHETTO, which was heavily influenced by the input and personal archive of producer Alexander Bernfes (1909-1985), himself a survivor of the ghetto who made it a calling to collect whatever material he could find on the subject. Of note is also the specific use of music found in some of these early appropriations, resulting in a strongly emotionalized presentation. This is particularly true for Jerzy Bossak’s short with its use of upbeat, even euphoric music, a stark yet deliberate contrast to the film’s title and the images of death and destitution. By means of their respective techniques, these early films already were struggling and experimenting with methods to appropriate the ghetto footage, clearly aware that the view it afforded had been shot through the Nazi lens. From at least the 1970s, material from the rough cut also was increasingly present in TV productions. Beyond the realm of filmmakers, the ghetto film attracted the attention of other authorities. The GDR’s Ministerium für Staatssicherheit, or Stasi, obtained a one-reel edit of the rough cut, presumably for potential use in war crimes trials. Specifically, the Stasi’s Hauptabteilung IX, responsible for criminal prosecutions, added this shortened version of the film to its film collection. The reel consists of outtakes mostly showing the squalid living conditions in the ghetto. Scenes staged by the Nazis to demonstrate the alleged well-being of affluent Jews are completely absent.30

After the German reunification and the merging of the GDR’s State Film Archive into the federal Bundesarchiv, commercial usage of the footage was controlled by Transit Film GmbH, the Bundesarchiv’s external licensing department. In a questionable effort to limit the film’s unrestrained circulation, much like it did for other documentary films of Nazi origin such as DER EWIGE JUDE (Fritz Hippler 1940), Transit Film GmbH would only allow eight minutes from the ghetto film to be licensed for commercial projects. When Hersonski’s production ran into this obstacle, they were able to overcome it by donating a lump sum to a charitable cause and were given the material from the Bundesarchiv in its entirety.31 Transit appears to have abolished this dubious practice soon afterwards. Today both the rough cut and the Restmaterial are being made available directly by the German Bundesarchiv, which considers both materials to be rights-free.32

Postwar Rediscovery II: Restmaterial

The other fragment, the Restmaterial, made a rather convoluted journey across various archives in at least three different countries. In 1945, Seymour W. ‘Budd’ Schulberg (1914-2009), a novelist and playwright, was drafted into the US Army and joined the Office of Strategic Services, the wartime precursor to the Central Intelligence Agency. As part of its Field Photographic Branch (termed "Field Photo" in contemporary documents), the OSS ran the War Crimes Photographic Project, headed by Hollywood director John Ford. Field Photo's mission was to collect audio-visual evidence that could be used in tribunals to be held against major Axis war criminals, including motion picture film. Schulberg was in occupied Germany from summer 1945. Making investigations into the Reichsfilmarchiv, based on detailed information the Americans had received from a German informant, a former employee at the archive, he soon was pointed to the archive’s various film vaults. He discovered that many of these sites had suffered catastrophic film fires. Most crucially, this had been the case for all the PK camera negatives buried in an access tunnel to an open-pit mine at Rüdersdorf, east of Berlin. Visiting the site, he found scorched film cans and fragments of burnt film scattered about; Schulberg himself was convinced the Nazis had torched incriminating evidence at the eleventh hour.33 His attention soon focused on the main premises of the Reichsfilmarchiv in Babelsberg, then in the Soviet zone of occupation. This site had not been destroyed, and still housed some of the most valuable collections of the archive in purpose built film vaults. It was now under the control of Soviet staff, aided by German auxiliaries. When Schulberg finally got in touch with the new head of the archive, Major Georgii Avenarius, the two men immediately established a good rapport: Schulberg was one of Commander John Ford’s OSS men in the field while Avenarius, a film professor in Moscow, had written extensively about Ford. As Schulberg tells it, he was soon given permission to take from the archive what he needed.34 This included films that would end up being spliced into one of the Americans’ major audio-visual offerings at the first Nuremberg trial, the OSS-authored compilation film THE NAZI PLAN (George Stevens, US 1945). Combined with newsreel footage and long excerpts from Leni Riefenstahl’s TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (DE 1935), THE NAZI PLAN utilized various archive discoveries to prove the Nazi conspiracy for war and the criminality of Nazi organizations, turning film documents against their creators as visual evidence.35 For example, a sequence of Heinrich Himmler visiting Minsk in the summer of 1941, shot by Hitler’s cameraman Walter Frentz, was procured by Schulberg from the vaults in Babelsberg.36

Schulberg’s pickings from the Reichsfilmarchiv also included harrowing footage from the Warsaw Ghetto. In a 1946 article published in The Screen Writer, the journal of the US Screen Writers Guild, Schulberg vividly recalled a particular scene which demonstrably is part of the Restmaterial, proving this was indeed the portion of the ghetto film he obtained from Avenarius:

Another valuable document, marked ‘Geheim - Oberkommando’ (Secret, by order of the High Command), was a horrendous two-reel film depicting the rounding up of the Jews in the Warsaw Ghetto and their inevitable burial in mass graves. German thoroughness is seen in its most frightening aspect in one shot in which a uniformed cameraman can be seen at the bottom of a mass grave getting a reverse shot as naked bodies, including those of small children and infants, come hurtling toward him.37

One might surmise that at least parts of the ghetto footage would have been a prime contender to be shown in Nuremberg to make a case for Nazi brutality and the persecution of the Jews of Europe, but in the end a decision was taken not to use the film: uniformed SS was not visible in the footage, but members of the uniformed Jewish Ordnungsdienst certainly were, brutalizing other Jews in scenes clearly staged for the camera. Fearing criticism leveled at the authenticity of the footage and regarding it as too polemical in its cynicism, the film ended up being shelved. This decision should be seen not only regarding any parts that might have been screened in Nuremberg, but in view of the entire Restmaterial at hand with its many inauthentic scenes: as a piece of not just visual but legal evidence it was heavily compromised, a fact that must have been evident to the prosecution.38

Had the Restmaterial been used in Nuremberg, its history of appropriation would be very different today. Instead, it was relegated to another archive. In the 1990s, Cooper C. Graham, a film archivist with the Library of Congress (LoC), and Adrian Wood, a British footage researcher working at that time for the upcoming BBC TV series THE NAZIS: A WARNING FROM HISTORY (Laurence Rees, GB 1997) chanced upon the material in a LoC nitrate vault.39 More recently, after the LoC had permitted other archives to make 35mm duplicates of the footage, it granted a request from the Filmoteka Narodowa (FINA) in Warsaw to deaccession of the original Restmaterial nitrates and their shipment to Poland.40 As of 2017, FINA is in possession of the only known 35mm elements of the ghetto film that date from before 1945. As physical artifacts, they help to shed further light on the film’s convoluted provenance and history of appropriation.

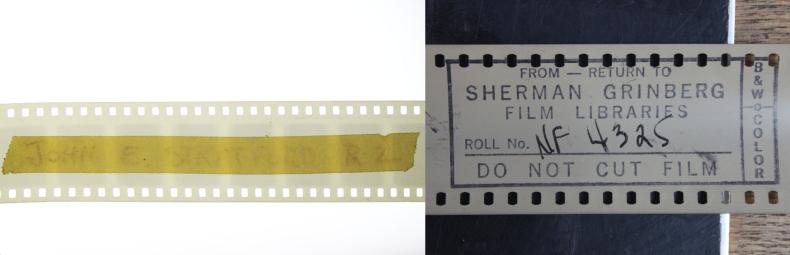

The nitrates in Warsaw, which are the physical copies originally stored at the Reichsfilmarchiv in Babelsberg, reveal that they were handled by two stock footage dealers in the early post-war period: John G. Stratford and the film library of Sherman Grinberg.41 Dr. John G. Stratford, a Jewish émigré from Hungary, entered the stock footage and film distribution business shortly after World War II and was awarded a contract by the Library of Congress to sift through, license, and ultimately restitute to the German Bundesarchiv captured German film from the stocks of the Alien Property Custodian, an entity of the U.S. Department of Justice, which had vested and impounded large amounts of German films. Beginning in the 1960s, the LoC restituted many of those German films to the Bundesarchiv in Koblenz. But approximately half of all German films received from the United States were not shipped by the LoC itself but by Stratford’s New York-based company, International Film Searchers, Inc.42 Perhaps more pertinent to the fate of the Restmaterial after Nuremberg, Stratford had been in the OSS during the war himself, running the Service’s Far East Film Program of the Schools and Training Branch.43 It is not inconceivable that his prior contacts and knowledge about OSS film matters resulted in his company obtaining the Restmaterial after its non-use in Nuremberg; however, it is equally possible that it was simply shipped from Nuremberg to the U.S. and added to the sprawling stocks of seized enemy film hoarded by the Office of Alien Property (OAP) before custody was transferred to the LoC. Stratford’s company was set up in New York precisely because the Alien Property Custodian stored a large amount of captured enemy films in a local vault, Bonded Film Storage Co. When the film stocks of the OAP were turned over to the Library of Congress, Stratford was contracted by the Library to inventory these New York holdings, a task he had carried out previously for the OAP itself.44

Outtakes from the Restmaterial supplied by Stratford were already used in 1953 in a film produced by the United States Information Agency (USIA), POLES ARE STUBBORN PEOPLE (US 1953). A Cold War-era propaganda short, the film reenacts the experiences of a Polish refugee escaping the Soviet sphere of influence and being granted asylum in the United States, while sharply criticizing Soviet hegemony in Eastern Europe.45 The film was part of a “Program to Counter Soviet Efforts to Demoralize the Emigration.”46 I would not have discovered this obscure film had I not found fragments of the ghetto footage in a film can at the German Bundesarchiv labeled ‘Poles Are Stubborn People’. This particular can was restituted to the Bundesarchiv by Stratford’s company in March of 1969.47 As the earliest known use of the ghetto film, POLES ARE STUBBORN PEOPLE already constitutes an egregious misappropriation. In Jaimie Baron’s categorization of use, misuse and abuse, it would fall squarely in the ‘abuse’ category: street scenes of the impoverished and dying from the ghetto film are used to illustrate the plight of the Polish people behind the Iron Curtain, under the yoke of postwar Soviet rule.48

Such improper usage notwithstanding, we may conclude that the Restmaterial was already in circulation as stock footage in the early 1950s, long before the rediscovery of the nitrate elements in a LoC vault in the 1990s. In fact, it appears to have been included in a list of ‘enemy’ films vested by the Alien Property Custodian, as well as in the Office of Alien Property’s inventory of seized German film, published in 1952. In both these published lists it figures under the title “Warschau - Ghetto” – quite possibly the actual, Reichsfilmarchiv-assigned title still written on the film cans.49 It is unclear whether the Bundesarchiv, whose archivist Hans Barkhausen (1906-1999), himself a former employee at the Reichsfilmarchiv, made great efforts to locate captured German film in U.S. archives, requested this particular title. It certainly should have piqued his interest as the focus of these early restitution efforts was on wartime documentary films and footage.50 It is however entirely possible that the LoC could not locate it: vast quantities of German film were sent to the LoC without proper inventories or bills of lading; in one particular incident, 12,000 pounds of German film sent on Army trucks were unceremoniously dumped on the Library’s doorstep.51 The German Bundesarchiv nevertheless did receive snippets of the Restmaterial very early during its restitution efforts, but this appears to have been incidental – and again the material came from Stratford. In 1963, the Bundesarchiv obtained a reel from Stratford’s company which consisted of Restmaterial outtakes, though apparently without realizing that it was from the Warsaw ghetto.52

Contrary to previous assumptions, the Restmaterial was therefore in circulation long before its rediscovery in the 1990s, and several years prior to the first-time use of the rough cut by the Thorndikes in their compilation film DU – UND MANCHER KAMERAD (GDR 1956). A holistic view of the rough cut, the Restmaterial, and the 16mm Agfacolor film would not materialize until Hersonski’s exploration of all available fragments in 2010.

Appropriation

As with all things archival, a film discovery is often a rediscovery, made by another generation of researchers and archivists. This holds especially true for the fate of the Restmaterial, stumbled upon immediately after the war but ending up being shelved in Nuremberg, then resurfacing in the 1950s as stock footage shots in obscure films and archive compilations, before being rediscovered and properly identified in the 1990s. Ever since, it has been essential in unmasking the inauthentic parts of the rough cut, an endeavor most strongly undertaken to date by Yael Hersonski.

Appropriating the ghetto film has been a gradual process based directly on what the archives provided, in different times and under different circumstances. With only the rough cut in wide circulation before the mid-1990s, filmmakers already were keenly aware of the Nazi authorship of the material. The available evidence on balance indicated that PK cameramen were the creators of the footage, since uniformed German cameramen are visible in a handful of shots of the rough cut. A particularly interesting embellishment of the then-available material is found in KORCZAK (Andrzej Wajda, PL 1990), where footage from the rough cut is combined with newly-shot reenactments of a Propagandakompanie team at work in the ghetto, wearing PK uniforms and using an Arriflex camera – quite similar in fact to shots in the Restmaterial that would be discovered only a few years later.

Our project so far has identified some 350 films which use either the rough cut, the Restmaterial, the 16mm Agfacolor film, or a combination of these elements. A mixed-media use of the surviving film materials has gained prominence after their extensive usage in A FILM UNFINISHED (2010). Prominence is given to the 16mm Agfacolor film and to specific shots from the Restmaterial revealing staged or orchestrated scenes. The Agfacolor film was likely shot by PK cameraman Hans Juppenlatz, who himself had been active in the amateur film movement in Germany and had taken his private 16mm film camera into the field with him. The film was seized by a Soviet specialist at an unknown location after the end of the war. In the early 1990s, his family offered the film for sale and it was acquired by the German Bundesarchiv, where the camera original resides today.53 The first use of the Agfacolor film may have been Jonas Misavicius’s documentary BREST GHETTO (BY 1995), which presents it as recently discovered and entirely unknown material; in an apparent oversight, the color footage is shown mirrored. The first use of the footage which garnered a notable international response and helped the Agfacolor film to prominence was the six-part TV series THE NAZIS: A WARNING FROM HISTORY (Laurence Rees, GB 1997). While a purely illustrative use of all fragments of the film remains widespread – the Warsaw Ghetto film is drawn upon to visualize the process of forcing the Jews to live in the newly-established ghettos in eastern Europe, prior to their deportation to the death camps –, deliberate misappropriations are less frequent. In FOLLOWING IN FELIX’S FOOTSTEPS (Steve Prankard, CA 2013), the footage is used to illustrate the ghetto in Łódź; no effort is made to disclose that the moving images are from the Warsaw ghetto. Overtly ‘abusive’ use of the footage is even less common. Besides the glaring example in POLES ARE STUBBORN PEOPLE, an interesting case is found in the Soviet documentary SIONIZM PERED SUDOM ISTORII (Oleg Uralov, USSR 1982). A damning indictment of Zionism throughout the ages, the film uses scenes of the Judenrat from the rough cut immediately after the iconic logo and fanfare of DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU, the Nazi wartime newsreel, as if material from the ghetto film had in fact been shown to cinema audiences in Germany at the time.

In striving to orchestrate glimpses of life and death – and even of Jewish traditions – in the Warsaw ghetto that conformed to the ideological perspective of the Nazis, the 1942 film is far from unique. Similar methods were employed in other film projects such as DER EWIGE JUDE (Fritz Hippler, DE 1940) and most likely in other, now lost, PK footage.54 Exact replications of this skewed view of Jewish life in the ghettos are found in the illustrated Nazi press.55 But there are some peculiar properties to the 1942 film. It was shot at a crucial point in the history of the ghetto, prior to the onset of mass deportations. It was left unfinished, given a security classification, and no public screenings took place. The scant information available points to a project possibly intended for the archive. If that is true, the film’s ‘archivalness’ is two-fold: in its intention as a Nazi memory-falsification project undertaken for an indeterminate posterity, as well as in its convoluted history across various archives, being discovered and rediscovered over the decades. The latter ‘archivalness’, as Jaimie Baron has pointed out, comes with a dangerous promise:

Indeed, the ideas of both ‘archivalness’ and rarity seem to promise truth-value as well as an experience of evidentiary revelation. The footage has been ‘found’, and it therefore has an aura of being directly excavated from the past. The sense of the ‘foundness’ of the footage enhances its historical authenticity because what has been ‘found’ has not (ostensibly) been fabricated or shaped by the filmmaker who repurposes this footage. Paradoxically, then, something ‘old’ gains part of its power by also promising something ‘new’, something we did not know or had not seen before.56

While the inauthentic nature of much of the film’s scenes has been exposed, its promise of ‘archivalness’, interpreted by the Thorndikes as a film kept from the German people, continues to eclipse its Nazi-stipulated memory purpose. The film at hand sought to shape an artificial reality of the ghetto, conforming to established anti-Semitic stereotypes and tropes, which the Nazis employed in their media on numerous occasions. More than likely, it sought to shape the perception of the Jews of Europe beyond their physical annihilation, to influence how they would be remember. 57

Academia still tends to approach the Warsaw Ghetto film through its most notable case of use, Yael Hersonski’s 2010 documentary, an inviting option as it affords many inroads into discussing problems such as the ghetto film’s status as a historical document, problems of authenticity, and the conditions required for a ‘responsible’ use, not least because the question arises whether Hersonski’s own film passes this test. The focus has been put on whether the gaze of the perpetrator can be reframed to inform a responsible, ethical use.58 Hersonski herself has attracted scrutiny in this debate, precisely because she criticized as too superficial the way in which previous filmmakers appropriated the film.59 But even some of the earliest uses of the rough cut were cautious to point out the Nazi origin and thus the dubious authenticity of the footage. The voice-over in Erwin Leiser’s MEIN KAMPF (SE/DE 1960) announces that “Goebbels’ own cameramen took these pictures.” In a similar manner, Frédéric Rossif prefaces any usage of the footage in LE TEMPS DU GHETTO (FR 1965) with a title card pointing out much the same. But a fundamental issue persists in many of the appropriations, whether historical or recent: a profound lack of contextual information and the near-complete failure to inform the viewer on the production and archival background of the images they are confronted with. This is also true for Hersonski, despite making it very clear that the film she is investigating is an archive discovery. At the start of Hersonski’s film, we see historical footage of film cans stacked to the ceiling in a film vault, culminating in the close-up of a film can with a Reichsfilmarchiv label and ‘Geheim’ (secret) stamp, a strong visual metaphor for the archive discovery we are about to witness. But not once is the archive from which the material originated discussed explicitly. This tends to consign the ghetto film to a rather nebulous realm of ‘the archive’, when in fact very palpable observations and deductions can be made, enabling us to identify the institutions, locations, and even some of the individuals involved.60

Increasingly, the Warsaw Ghetto film appears to be drawn upon as a historical source, whilst fully acknowledging the challenges associated with its compromised authenticity. As one of several surviving films from the ghetto, including a considerable number of amateur films taken by German soldiers, it is part of a larger body of moving images recorded by the perpetrators that would benefit from a comparative analysis and the pooling of information about these films.61 A comprehensive, integral approach to the glimpses, glances, and gazes of the ghetto recorded on photographic film and film footage is still emerging. It would need to consider not just German films and photographs, but audiovisual documents recorded by bystanders and the ghetto’s inhabitants, in order to counterbalance the predominance of perpetrator imagery.62 The Warsaw Ghetto Museum in Warsaw, a newly established memory institution scheduled to open to the public in 2025, is currently undertaking a project to interactively map the Warsaw Ghetto. In doing so, the museum is working from a multitude of sources: photographic collections as well as moving images. A closer reading of the 1942 film and the identification of topographical features – streets, buildings, shops – could inform a more precise use in the future, both in publication and exhibition projects. Even more ambitiously, high-quality digital transfers of the 35mm elements may lead to further identification of individuals visible in the footage, a challenging endeavor which has been undertaken on a smaller scale for other ghetto films.63 As an ongoing process, the unmasking of the film's production background, archival provenance, and history of appropriation hopefully will add to this future, informed use.

- 1

The Großaktion or Große Aktion began on July 22 and lasted until September 21, 1942. Approximately 265,000 Jews were deported and murdered; after the Aktion, 70,000 Jews remained in the vastly reduced ghetto.

- 2

It certainly extended to documenting the quashing of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, as evidenced by the Stroop Report. For a detailed discussion of these Nazi documentation efforts, see Fabian Schmidt and Alexander Oliver Zöller, “Atrocity Film,” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe, no. 12 (March 2021), https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2021.00012.223.

- 3

Elke Fröhlich, ed., Die Tagebücher von Joseph Goebbels II, vol. 4 (München: Saur, 1995), 184, author’s translation. German original: “Himmler betreibt augenblicklich die große Umsiedelung der Juden aus den deutschen Städten nach den östlichen Ghettos. Ich habe veranlaßt, daß hier in großem Umfange Filmaufnahmen gemacht werden. Das Material werden wir für die spätere Erziehung unseres Volkes dringend brauchen.” This leaves some ambiguity (‘hier’ / here) as to where such footage was to be shot, i.e. whether the order resulted in film activities in any of the other ghettos.

- 4

Daniel Uziel, “Propaganda, Kriegsberichterstattung und die Wehrmacht. Stellenwert und Funktion der Propagandatruppen im NS-Staat”, in Die Kamera als Waffe. Propagandabilder des Zweiten Weltkrieges, eds. Rainer Rother, Judith Prokasky (München: edition text+kritik, 2010), 20. See also Hasso von Wedel, Die Propandatruppen (Neckargemünd: Vowinckel, 1960), 96-102. An in-depth study of this unit and its purpose remains a desideratum of research.

- 5

The author wishes to thank the Juppenlatz family for giving access to documents and photographs from the estate of Hans Juppenlatz.

- 6

Elke Fröhlich, ed., Die Tagebücher von Joseph Goebbels II, vol. 5 (München: Saur, 1995), 391, author’s translation. German original: “Einige grauenhafte Filmstreifen werden mir aus dem Ghetto in Warschau gezeigt. Dort herrschen Zustände, die überhaupt nicht beschrieben werden können. Das Judentum zeigt sich hier in aller Deutlichkeit als eine Pestbeule am Körper der Menschheit. Diese Pestbeule muß beseitigt werden, gleichgültig, mit welchen Mitteln, wenn die Menschheit daran nicht zugrunde gehen will.”

- 7

Oliver Sander, “Deutsche Bildberichter in Polen,” in, W obiektywie wroga. Niemieccy fotoreporterzy w okupowanej Warszawie 1939-1945 / Im Objektiv des Feindes. Die deutschen Bildberichterstatter im besetzten Warschau 1939-1945, eds. Eugeniusz C. Król and Danuta Jackiewicz (Warsaw: Oficyna Wydawnicza RYTM, 2009), 35.

- 8

Bundesarchiv, “12 Gebote für den Filmberichter,” BArch N 1603 (Horst Grund estate), author’s translation. German original: “Du sollst gestellte Kampfaufnahmen vermeiden, denn sie wirken unecht und gefährden das Ansehen der Filmberichter.” Note this ‘commandment’ specifically eschewed only the staging of combat footage.

- 9

See Daniel Uziel, “Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops and the Jews,” in Yad Vashem Studies 29 (2001), 27-63.

- 10

Oliver Sander, Deutsche Bildberichter in Polen, 33-37. Regarding the controversial value of PK photography as a source and known falsifications, see also Gerhard Paul, Bilder einer Diktatur. Zur Visual History des “Dritten Reiches” (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2020), 277-289.

- 11

Raul Hilberg, Stanislaw Staron, Josef Kermisz, eds., The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow (New York: Stein and Day, 1979), 349.

- 12

Ibid., 350.

- 13

Ibid., 353-354.

- 14

Ibid., 355-356. Some of the scenes commented on by Czerniakow are indeed found in either the rough cut or the Restmaterial, enabling reliable dating of these sequences.

- 15

Diary of Rokhl Auerbakh (Rachel Auerbach), entry for May 22, 1942, quoted in Yad Vashem, Flashes of Memory: Photography during the Holocaust (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2018), 3.

- 16

Jacob Apenszlak, Jacob Kenner, Isaac Lewin, Moses Polakiewicz, eds., The Black Book of Polish Jewry. An account of the martyrdom of Polish Jewry under the Nazi occupation (New York: Roy Publishers, 1943), 324. The notice was quoted from an account of the World Jewish Congress, likely based on the same informant.

- 17

Miriam Y. Arani, “Wie Feindbilder gemacht wurden. Zur visuellen Konstruktion von 'Feinden' am Beispiel der Fotografien der Propagandakompanien aus Bromberg 1939 und Warschau 1941,” in Die Kamera als Waffe, eds. Rainer Rother, Judith Prokasky (München: edition text+kritik, 2010), 150-166.

- 18

Vicente Sánchez-Biosca, The death in their eyes. What perpetrator images perpetrate (New York: Berghahn Books, 2024), 129-175; Dirk Rupnow, Vernichten und erinnern. Spuren nationalistischer Gedächtnispolitik (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2005),242. See also Schmidt/Zöller, “Atrocity Film,” who consider that the Nazis’ interest in documenting the genocide may well have extended beyond the ghettoization stage, even though little film material survives today for obvious reasons.

- 19

Tesch developed all the PK film footage, including restricted material. This was initially done under armed guard. Ralf Forster, “Von der Front in die Kinos. Der Weg der PK-Berichte in die DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU”, in Die Kamera als Waffe, eds. Rainer Rother, Judith Prokasky(München: edition text+kritik, 2010), 52. The Propaganda-Einsatz-Abteilung had its own Verbindungskompanie (liaison company) to ensure rapid transfer of PK films and photographs to Berlin. Wedel, Die Propagandatruppen, 100-102.

- 20

The classifications ‘Wochenschauwert’ and ‘Archivwert’ are found in the lists of newly censored PK film footage, fragmentary copies of which have survived in the estates of former PK-Filmberichter. No known archive holdings exist. The author is indebted to Hans-Gunter Voigt, Potsdam, for information and a collection of reference samples of this important source.

- 21

Regarding possible causes for these film fires, including deliberate destruction, see Schmidt/Zöller, “Atrocity Film.” Today only a handful of unedited, uncensored reels of PK footage from the Reichsfilmarchiv remain at the German Bundesarchiv. To the best of my knowledge, no other PK reel at the Bundesarchiv carries a ‘Geheime Kommandosache’ leader.

- 22

A handful of surviving reels of unedited PK footage at the Bundesarchiv allows for some comparison. KA numbers 11376 and 12152 were both shot and developed in February 1942.

- 23

Close examination of the 35mm elements of the rough cut at the Bundesarchiv so far has not elicited any KA numbers. They likely were lost as a result of removing the leaders and duplicating the image onto safety film, way back in the 1950s. Grease pencil writing in particular, which often shows as faint smudges in the image, is virtually impossible to detect once a film has been copied.

- 24

Fritz Hippler, Die Verstrickung. Auch ein Filmbuch… (Düsseldorf: Verlag Mehr Wissen, 1981), 187. For a detailed discussion of comparable efforts by the SS and other organizations to document the process of annihilation, see Schmidt/Zöller, “Atrocity Film” and Rupnow, Vernichten und Erinnern, 232-246.

- 25

The PK-Filmstelle’s entire records and card indices have been lost; likely they were destroyed at the end of the war. See the documents in the British National Archives, Records of the Foreign Office relating to allied administration of occupied territories in post Second World War Europe, FO 1057/223/1.

- 26

Oral history interview with Klaus Alde, June 14, 2015. Alde was an assistant director for the film and likely the individual who first happened upon the film cans containing the ghetto footage.

- 27

Nitrate decomposition is evident in part of the rough cut. It is likely that in order to copy the decaying film, the Thorndikes further damaged and then destroyed the nitrates: no nitrate elements of the rough cut are accounted for in any of the SFA’s accession books or catalogs.

- 28

Oral history interview with Klaus Alde, June 14, 2015.

- 29

I am indebted to the late Wolfgang Klaue, the last director of the GDR’s State Film Archive and former President of FIAF, for an eyewitness account of this rediscovery. The ghetto film was rediscovered in cans labeled ‘Saatgut’ (seed) – likely a cipher used by the Thorndikes for film material considered for inclusion in DU – UND MANCHER KAMERAD (GDR 1956). Unrelated newsreel footage was equally found to have been placed in cans labeled ‘Saatgut’.

- 30

The reel has since been deposited at the Bundesarchiv, AUFNAHMEN VOM WARSCHAUER GHETTO, BArch, BSP 27048, accessed December 20, 2024, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/42627/685330.

- 31

For information about this incident I am indebted to the film’s producer, Noemi Schory.

- 32

They are accessible online at the Bundesarchiv’s digital reading room: GHETTO, BArch, film ID 5593, accessed December 20, 2024, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/5593/ and GHETTO-RESTMATERIAL, BArch, film ID 23165, accessed December 20, 2024, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/23165/.

- 33

Budd Schulberg, “The Celluloid Noose,” in The Screen Writer, vol. II, no. 3 (August 1946): 6-7.

- 34

Cornell University Law Library, Donovan Nuremberg Trials Collection, OSS War Crimes Photographic Project/Field Photo Branch, Report, September 11, 1945, https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/nur02024.

- 35

For an in-depth discussion of the prosecutorial challenges at Nuremberg, see Sylvie Lindeperg, Nuremberg, la bataille des images. Des coulisses à la scène d’un procès-spectacle (Paris: Payot-Rivages, 2021). THE NAZI PLAN (US 1945) has emerged as an important secondary source of ‘iconic’ Nazi film footage, as filmmakers have repeatedly reverted to it rather than seeking out the original film materials in the archives. This is particularly true for newsreel footage of the 1933 boycott against Jewish businesses in Nazi Germany and for the book burnings on May 10 the same year.

- 36

This PK film likely survives only as a sequence edited into THE NAZI PLAN. During his trip to Minsk, Himmler witnessed a mass execution; Walter Frentz later claimed to have taken no film but only a single color slide of the scene, which he was ordered to destroy. See Klaus Hesse, “‘… Gefangenenlager, Exekution, ... Irrenanstalt ...’: Walter Frentz’ Reise nach Minsk im Gefolge Heinrich Himmlers im August 1941,” in Das Auge des Dritten Reiches. Hitlers Kameramann und Fotograf Walter Frentz, ed. Hans Georg Hiller von Gaertringen (München, Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2006), 176-194.

- 37

Budd Schulberg, The Celluloid Noose, 12. Additional shots of the burial of emaciated corpses in mass graves are also found in the rough cut, but none of the German cameramen are visible.

- 38

Lindeperg, Nuremberg, la bataille des images, 67-68.

- 39

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung, Geheimsache Ghettofilm, accessed December 20, 2024, https://www.bpb.de/themen/nationalsozialismus-zweiter-weltkrieg/geheimsache-ghettofilm/169552/das-restmaterial-als-beweis-der-inszenierung/.

- 40

The Bundesarchiv, which pursued a strict nitrate destruction policy at the time, chose to obtain a 35mm dupe negative in 2000: BArch, B 54862. The deaccessioning of the nitrates and their transfer by the LoC to Warsaw should not be seen as a restitution; the Restmaterial was requested by FINA as part of a bundle of films either of Polish origin or with historical relevance to Poland. I am indebted to Mike Mashon, the former head of the Library of Congress Moving Image section, for sending me the relevant shipping reports and ancillary documents, as well as for information provided by the current and former staff at FINA, which ultimately helped pinpoint the physical elements in Warsaw.

- 41

The Sherman Grinberg Film Library may still hold its own copy of Restmaterial stock footage shots, but it has yet to be discovered following the sale of the company, which has left parts of the collection without proper descriptions. My thanks to Raye Farr, Washington D.C., who recalls having watched Restmaterial footage at Sherman Grinberg many decades ago, and to Lance Watsky of Sherman Grinberg for consulting his staff and database.

- 42

In the legacy database of the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, these accessions figure under “Stratford, New York”; they number approximately 2,000 items.

- 43

National Archives and Records Administration, NARA RG 131 (Office of Alien Property), Motion Picture Subject Files, Entry A1 251, Box 2. See also NARA RG 226 (Office of Strategic Services), Series UD 133, Box 162, which contains Stratford’s OSS personnel file.

- 44

For limited information on Stratford’s dealings with the OAP and the LoC, see Library of Congress, Motion Picture, Broadcasting & Recorded Sound Division, German Collection acquisition files (internal administrative files). I am indebted to Cooper C. Graham for pointing me to these internal records. They also include a set of printed forms on government stationery acknowledging receipt of various atrocity footage screened in Nuremberg, including captured German film, but the Warsaw Ghetto film is not among them.

- 45

National Archives and Records Administration, NARA, RG 306 (U.S. Information Agency), Moving Images Relating to U.S. Domestic and International Activities, NAID 52015, accessed December 20, 2024, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/5201. A 35mm viewing print is available on site.

- 46

Foreign Relations of the United States, 1955-1957, Eastern Europe, vol. XXV, paper prepared by the Interdepartmental Escapee Committee, https://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1955-57v25/d35.

- 47

Bundesarchiv, POLES ARE STUBBORN PEOPLE, BArch, K 35906, last access December 20, 2024, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/179417/82698.

- 48

Jaimie Baron, Reuse, misuse, abuse. The ethics of audiovisual appropriation in the digital era (New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2021). See also the correspondence and script for POLES ARE STUBBORN PEOPLE in Morrie Ryskind’s papers at the New York Public Library, Series II, Sub-series 1, b. 3 f. 6.

- 49

The film was vested under order 18664: Office of Alien Property, Motion Pictures of German Origin Subject to Jurisdiction of Office of Alien Property, December 1, 1952, 89, entry ‘Warschau - Ghetto’.

- 50

See the lists of restituted films in Library of Congress, German Collection acquisition file. See also Hans Barkhausen, “Deutsche Filme in den USA. Rückführung im Austausch,” Der Archivar, 1966, 3 (July): cols. 259–264.

- 51

A document about this incident is found in LoC, German collection acquisition files.

- 52

Bundesarchiv, old archive title: “Austreiben jüdischer Kinder aus einem Raum” (Expulsion of Jewish children from a room). This reel was later edited into a compilation; its current title is “KZ-Insassen: Oranienburg; unbekannter Ort,” BArch, K 35815, accessed December 20, 2024 https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/86998/562312. The ‘unknown location’ is in fact footage from the prison in the Warsaw Ghetto, found in the Restmaterial.

- 53

Author’s correspondence with Adrian Wood. The camera original and access copies are held by the Bundesarchiv, IM WARSCHAUER GHETTO (archive title), BArch, film ID 3323, accessed December 20, 2024, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/3323/.

- 54

For example, the PK filmed in the Warsaw Ghetto in 1941. The filming was recorded in numerous PK photographs, but the corresponding film footage has been lost. For a complete filmography of known PK material (extant as well as lost) dealing with the ghettos, see Fabian Schmidt and Alexander Zöller, “Filmography of the Genocide: Official and Ephemeral Film Documents on the Persecution and Extermination of the European Jews 1933–1945,” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces, no. 4 (February 2022): 1–160, https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18245.

- 55

See Harriet Scharnberg, Die Judenfrage im Bild. Der Antisemitismus in nationalsozialistischen Fotoreportagen (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2018).

- 56

Jaimie Baron, The Archive Effect. Found footage and the audiovisual experience of history (New York: Routledge, 2014), 6.

- 57

Rupnow, Vernichten und erinnern.

- 58

Baron, Reuse, misuse, abuse, 124-134.

- 59

For particularly robust criticism, see Dirk Rupnow, "Die Spuren nationalsozialistischer Gedächtnispolitik und unser Umgang mit den Bildern der Täter. Ein Beitrag zu Yael Hersonskis ‘A Film Unfinished’/’Geheimsache Ghettofilm’,” in Zeitgeschichte-online (October 1, 2010), https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/film/die-spuren-nationalsozialistische…. Rupnow posits that Hersonski, too, failed in breaking the ideological message of the perpetrator images, but leaves open the question of how that could be achieved. For a more recent discussion, see David Zeglen, “A practical gaze at the Warsaw Ghetto: revealing excess & lack in A FILM UNFINISHED,” Continuum, 34(5) (2020): 763–775, https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2020.1798877.

- 60

The scene, shot postwar in one of the Babelsberg vaults of the former Reichsfilmarchiv, was taken from the introductory sequence of the short-lived documentary series ARCHIVE SAGEN AUS (GDR 1957-1959). The series continued the trial-by-document method employed in DU - UND MANCHER KAMERAD, using archive films to illustrate historical events whilst relying on carefully selected - and at times forged - documents to underpin the desired messages. In Hersonski’s film, the shot is shown in reverse, giving prominence to the close-up of the film can.

- 61

For an overview, see Fabian Schmidt and Alexander Zöller, “Filmography of the Genocide: Official and Ephemeral Film Documents on the Persecution and Extermination of the European Jews 1933–1945,” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces, no. 4 (February 2022): 1–160. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18245.

- 62

An intriguing offering in this regard is Anna Duńczyk-Szulc and Agnieszka Kajczyk, Antologia spojrzeń. Getto warszawskie – fotografie i filmy / Anthology of Glances. The Warsaw Ghetto: Photographs and Films (Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny/Muzeum Warszawy, 2023), which provides an overview of the available body of audiovisual material.

- 63

Efrat Komisar, “Filmed Documents. Methods in Researching Archival Films from the Holocaust,” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe, no. 2-3 (January 2016), https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2016.0002-3.85. The author points out the limited chances of identifying individuals in a large ghetto such as Warsaw.

Apenszlak, Jacob, Jacob Kenner, Isaac Lewin, and Moses Polakiewicz, eds. The Black Book of Polish Jewry. An Account of the Martyrdom of Polish Jewry under the Nazi Occupation. New York: Roy Publishers, 1943.

Arani, Miriam Y. “Wie Feindbilder gemacht wurden. Zur visuellen Konstruktion von 'Feinden' am Beispiel der Fotografien der Propagandakompanien aus Bromberg 1939 und Warschau 1941.” In Die Kamera als Waffe, edited by Rainer Rother and Judith Prokasky, 150-166. München: edition text+kritik, 2010.

Barkhausen, Hans. “Deutsche Filme in den USA. Rückführung im Austausch.” Der Archivar, 1966, 3 (July): cols. 259–264.

Baron, Jaimie. Reuse, Misuse, Abuse. The Ethics of Audiovisual Appropriation in the Digital Era. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2021.

Baron, Jaimie. The Archive Effect. Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Geheimsache Ghettofilm. Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.bpb.de/themen/nationalsozialismus-zweiter-weltkrieg/geheimsache-ghettofilm/169552/das-restmaterial-als-beweis-der-inszenierung/.

Cornell University Law Library. “War Crimes Photographic Project / Office of Strategic Services / Field Photographic Branch / APO 413.” Accessed December 20, 2024. https://digital.library.cornell.edu/catalog/nur02024.

Duńczyk-Szulc, Anna and Agnieszka Kajczyk. Antologia spojrzeń. Getto warszawskie – fotografie i filmy / Anthology of Glances. The Warsaw Ghetto: Photographs and Films. Warsaw: Żydowski Instytut Historyczny/Muzeum Warszawy, 2023.

Forster, Ralf. “Von der Front in die Kinos. Der Weg der PK-Berichte in die DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU.” In Die Kamera als Waffe, edited by Rainer Rother and Judith Prokasky, 49-68. München: edition text+kritik, 2010.

Fröhlich, Elke, ed. Die Tagebücher von Joseph Goebbels. München: Saur, 1995.

Hesse, Klaus. “‘… Gefangenenlager, Exekution, ... Irrenanstalt ...’: Walter Frentz’ Reise nach Minsk im Gefolge Heinrich Himmlers im August 1941.” In Das Auge des Dritten Reiches. Hitlers Kameramann und Fotograf Walter Frentz, edited by Hans Georg Hiller von Gaertringen, 176-194. München, Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag, 2006.

Hilberg, Raul, Stanislaw Staron, and Josef Kermisz, eds. The Warsaw Diary of Adam Czerniakow. New York: Stein and Day, 1979.

Hippler, Fritz. Die Verstrickung. Auch ein Filmbuch… Düsseldorf: Verlag Mehr Wissen, 1981.

Keefer, Edward C., Ronald D. Landa, and Stanley Shaloff, eds. Foreign Relations of the United States. 1955-1957. Eastern Europe. Volume XXV. Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1990.

Komisar, Efrat. “Filmed Documents. Methods in Researching Archival Films from the Holocaust.” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe 2–3 (January 2016). DOI: https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2016.0002-3.85.

Lindeperg, Sylvie. Nuremberg, la bataille des images. Des coulisses à la scène d’un procès-spectacle. Paris: Payot-Rivages, 2021.

Office of Alien Property. Motion Pictures of German Origin Subject to Jurisdiction of Office of Alien Property. December 1, 1952.

Paul, Gerhard. Bilder einer Diktatur. Zur Visual History des "Dritten Reiches". Göttingen: Wallstein, 2020.

Rupnow, Dirk. "Die Spuren nationalsozialistischer Gedächtnispolitik und unser Umgang mit den Bildern der Täter. Ein Beitrag zu Yael Hersonskis ‘A Film Unfinished’/’Geheimsache Ghettofilm’.” Zeitgeschichte-Online, October 1, 2010. https://zeitgeschichte-online.de/film/die-spuren-nationalsozialistischer-gedaechtnispolitik-und-unser-umgang-mit-den-bildern-der.

Rupnow, Dirk. Vernichten und erinnern. Spuren nationalistischer Gedächtnispolitik. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2005.

Sánchez-Biosca, Vicente. The Death in Their Eyes. What Perpetrator Images Perpetrate. New York: Berghahn Books, 2024.

Sander, Oliver. “Deutsche Bildberichter in Polen.” In W obiektywie wroga. Niemieccy fotoreporterzy w okupowanej Warszawie 1939-1945 / Im Objektiv des Feindes. Die deutschen Bildberichterstatter im besetzten Warschau 1939-1945, edited by Eugeniusz C. Król and Danuta Jackiewicz, 31-47. Warsaw: Oficyna Wydawnicza RYTM, 2009.

Scharnberg, Harriet. Die Judenfrage im Bild. Der Antisemitismus in nationalsozialistischen Fotoreportagen. Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2018.

Schmidt, Fabian and Alexander Zöller. “Filmography of the Genocide: Official and Ephemeral Film Documents on the Persecution and Extermination of the European Jews 1933–1945.” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces 4 (February 2022): 1–160. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18245.

Schmidt, Fabian and Alexander Zöller. “Atrocity Film.” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe 12 (March 2021). DOI: https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2021.00012.223.

Schulberg, Budd. “The Celluloid Noose.” The Screen Writer, vol. II, no. 3 (August 1946): 1-15.

Uziel, Daniel. “Propaganda, Kriegsberichterstattung und die Wehrmacht. Stellenwert und Funktion der Propagandatruppen im NS-Staat.” In Die Kamera als Waffe, edited by Rainer Rother and Judith Prokasky, 13-36. München: edition text+kritik, 2010.

Uziel, Daniel. “Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops and the Jews.” Yad Vashem Studies 29 (2001): 27-63.

Wedel, Hasso von. Die Propandatruppen. Neckargemünd: Vowinckel, 1960.

Yad Vashem. Flashes of Memory: Photography during the Holocaust. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem, 2018.

Zeglen, David. “A practical gaze at the Warsaw Ghetto: revealing excess & lack in A FILM UNFINISHED.” Continuum 34, no. 5 (2020): 763–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2020.1798877.