The Westerbork Film

Image Migration and Selective Appropriation

Table of Contents

From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards

TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935)

Contested Memory

DER EWIGE JUDE (1940)

From Home Movie to Historical Document

A Living Document

Archiving the Ghetto

The Westerbork Film

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Schmidt, Fabian. “The Westerbork Film: Image Migration and Selective Appropriation.” Research in Film and History 7 (2025): 1–44. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/24050.

‘Holocaust’ is not only an internationally recognized term for genocide, but it has also become a symbol for the evil committed by humans against humans. And hardly any historical event is considered as thoroughly researched today as the Holocaust. The mottos "Never again" and "Wehret den Anfängen" (Resist the beginnings) uphold its memory as reminders to be vigilant against any form of racism and discrimination, both being harbingers of genocide. The nationwide demonstrations in Germany in January 2024 in response to a meeting staged by the AfD (a far-right and right-wing populist party) as a second Wannsee Conference between Identitarians and AfD officials in November 2023, are a prime example of how deeply both German democratic society at large and, though conversely, supporters of the New Right have internalized the persecution and murder of the European Jews as an identity-forming memory. The AfD's attempt to introduce a new form of nationalistic democracy bypassing the so-called ‘established parties’ (Altparteien) is not without reason structured as an attack on the cultural engagement with National Socialism. Such instrumentalizations of Holocaust remembrance, but also Holocaust comparisons, to name another phenomenon of popular cultural reference, continue to be equally taboo and ubiquitous. Although the Holocaust in public perception is considered researched and an unequivocal stance towards it as a moral standard is hardly ever questioned outside of far-right discourses (and some of the discussions about postcolonialism, to be precise), controversial Holocaust topics are still discussed in both, academic and pop-cultural contexts. These are not major controversies, rather minor bumps, but they point to a disruption in a deeper layer of collective memories. While the New Right seeks to erase an unwanted memory entirely, these controversies instead highlight how dominant Holocaust remembrances may, in a conciliatory manner, divert attention from what could be an even more unsettling truth. Three of these more recent topics are the question of complicity in and knowledge about the Holocaust in Germany and abroad before 1945, secondly the discussion about the extent of responsible involvement of German institutions during World War II, which remain virulent as a faint echo of the scandal surrounding the so-called Wehrmachtsausstellung, and finally the topic of dealing with the murder of the Jews immediately after the war. The paradoxical absence of an explicit reference to Jews as the main victim group in the re-education films and the first documentary films after the end of World War II is the subject of current academic research, and considerations regarding the causes can be found, among others, in recent publications by Sylvie Lindeperg, Ulrike Weckel, and Natascha Drubek.1 This topic, which is currently discussed almost exclusively in the academic domain, is closely linked to the question of the extent of complicity in the genocide not only in the German Reich, but also among the Allies. While there were a number of German-language publications in the 2000s on the question of complicity among Germans,2 contemporary knowledge of the murder of the Jews, particularly in the US government, but also among the US public, became the subject of a mainstream production only recently in the series THE US AND THE HOLOCAUST (US 2023). These developments are signs of a, albeit gradual, re-formation of Holocaust remembrance. In question here are the origins and conditions of the formation of today's dominant memories of the Holocaust. More precisely at stake here is a redefinition of the concept of bystanders and successively the relation of Holocaust remembrance to individual memories. These developments are of particular importance for the memory theory research interest presented in this paper, as they shed light on the emergence and the formation of Holocaust memory. Insofar as the questioning of Holocaust memory is one of the core themes of the New Right, an examination of the origins of these remembrances is highly topical.

The formation of Holocaust remembrance has been accompanied by the use of audio-visual documents from the very beginning. Today, digital visual history, a concept introduced by Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann,3 is handed down, discussed and challenged in several domains, on social media, within computer games and feature films. One of the oldest practices in visual history is the reuse of audiovisual footage in documentary films, dating back to analogue times. Since the sharp increase in the number of documentaries about the Third Reich around the 50th anniversary of the end of World War II, the visual history of this difficult chapter of the past has been a subject of growing interest, both in the public and in the academic domain.4 Commonplaces of this discourse include the alleged inflationary use of the same footage, often shrouded in the critical term ‘iconic images’, but also more openly addressed as ‘Abnutzung’ (wearout)5 or ‘illustrative wallpaper’, as Toby Haggith once labeled the use of Bergen-Belsen images.6 Claims of endless repetition7 and of a distancing and numbing effect are raised regularly. These assumptions are reinforced by the film scholar's privileged viewpoint. However, these claims are rarely empirically tested. With the new instruments of digital visual history, it seems only logical to take a closer look and to re-evaluate these assumptions by examining the plethora of existing utilizations. This raises two questions. How justified are the claims about the ongoing repetition of the same images and how does iconicity emerge? And secondly, how are these patterns of use related to the collective remembrances, or more precisely: how are these audiovisual materials entangled in the formation of Holocaust remembrance, if not by merely symbolizing these events as the commonplace theories about iconicity suggest?

This paper analyzes such questions alongside the examination of the provenance and the history of use of one of the most prolific and at the same time often unrecognized archive materials, the so-called Westerbork film, or alternatively, when referring not only to the edited film but to all surviving outtakes and negatives, the Westerbork material or footage. The Westerbork film, commissioned by the SS, was shot in early 1944 at a Nazi transit camp for Jews in the Netherlands. The surviving footage consists of approximately two hours and 30 minutes of silent 16mm black-and-white film, depicting both daily camp life, including work barracks and a deportation to Auschwitz, and moments of leisure. Rediscovered in 1947, the footage gained prominence in 1956 when Alain Resnais featured it in his renowned essay film NUIT ET BROUILLARD. Since then, it has become a central part of the widely used body of perpetrator-shot Holocaust footage and a key example of how archival material is repurposed over time. Examining the migration of such images across documentary and feature films reveals producers' and directors' curatorial choices and the underlying rules that shape visual history. This approach, focused on production studies rather than auteur theory, examines the culture of footage usage negotiated among producers, archivists, and directors and as outcome of budget, availability, aesthetics, and the broader context of archival curation. This shift from an auteur-centric view to production processes is also driven by the observation that filmmakers usually don't present their footage choice as purely individual expression, but delegate the selection of material to archive-producers. Because provenance shapes the social memory of the Westerbork film, concerns about inherent gazes and misuse connect the investigation to cultural studies, particularly to critical approaches like Jamie Baron's theories on archive effect and appropriation.8 The exploration of image migration in the context of remembrance formation – the cinematic memory of the Westerbork film – is clearly in the domain of visual history and memory studies. In balance to production studies, the memory studies perspective analyses and contextualizes the producer's choices critically. This means that selectivity9 – the actualizing or not actualizing of memory – is present twofold: as the selection of images in the process of production (producing a variation) and as selection in the process of reception (as memory, or the selecting and sustaining of a variation). This essay opts for an in-between approach that makes use of paradigms from both fields, film studies (including production studies) and memory studies.

Unpublished Archive Films in Post-War Documentary Films

In the first documentary films about the Third Reich that were published after the re-education films, such as BIS 5 NACH 12 (DE 1953) and BEIDERSEITS DER ROLLBAHN (DE 1953), all of the footage utilized was taken from published propaganda films or newsreels except for the material from the liberation of the camps.10 Excerpts from films such as TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (TRIUMPH DES WILLENS, DE 1935) came with the double function of generally illustrating the documentary's discourse and specifically documenting and evidencing the publicized and therefore mediated reality of 1930s and 1940s. But soon, documentaries changed from newsreel subject summaries to more autonomous forms and a new type of footage, hitherto neglected, became an important asset: the unpublished archive film. The material in question is a kind of in-between category, because its half-official production background renders it less ephemeral than found footage such as home movies, but it doesn't have the self-evident aura of newsreels or propaganda films. These unpublished archive films may come from semi-official contexts, like privately-shot footage taken by an officer during off-duty hours. Unreleased archive film exerts a fascination that is not sufficiently precisely described by the broader phenomenon of perception that Jamie Baron has summarized under “archive effect.” They have in common that they usually do not show any known personalities or events and hence are suitable for two objectives: for seemingly neutral illustration or even documentation, and for dramatization. They nonetheless share an aura of authenticity, largely owed to provenance narratives that the films accumulate over time, and their status as previously unreleased items adds to their exclusivity. The data collected and assessed in the DFG Filmikonen project shows that these archival materials have a special, so far widely unacknowledged, history of use and this paper centers around one of them – the Westerbork film.

The first documentary film to make use of such unpublished archive films was the educational film NÜRNBERG UND SEINE LEHRE (NUREMBERG ITS LESSON FOR TODAY, DE 1948) by Stuart Schulberg, a film project that started in 1946 and whose production and publication was delayed several times.11 By adding sound effects, Schulberg thrived for an immediate realism beyond the re-use of newsreels, even though the Holocaust narrative here is mostly derived from witness reports and is only loosely connected to the images.12 However, Schulberg was the first post-war filmmaker to dedicate a passage explicitly to the persecution of the European Jews. The images of the gassing in Mogilev and the fragments of the pogroms in Lviv had a different effect than the liberation images of the Allies, which were more explicit but maybe also easier to shake off as propaganda. NÜRNBERG UND SEINE LEHRE was ahead of its time but had hardly a memory-forming effect. Due to its delayed completion, the film found an audience in a Germany that was already preparing for the Cold War. The film's unambiguous attribution of guilt to the leading cadres in the Nuremberg trials was a welcome narrative.13 Eight years later, in 1956, Alain Resnais’ NUIT ET BROUILLARD was the first documentary film with an international distribution that utilized even more of such unpublished archive footage, specifically the material DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS, sometimes attributed to the archive of the Warsaw Documentary and Feature Film Studio (WFDiF)14 and, eventually, the Westerbork film, with more success. That being said, the materials were not used for the representation of the genocide but as illustration of the deportation of French Resistance fighters. It would take another four years until Erwin Leiser's DEN BLODIGA TIDEN/MEIN KAMPF (SE/DE 1960) introduced the so-called Warsaw Ghetto Film.15 The publication of Reinhard Wiener’s 8mm film footage of the mass execution in Liepaja (the LIEPAJA EXECUTIONS FILM) in Peter Schier-Gribowsky’s AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS (DE 1961) completed today’s canon of unpublished perpetrator archive footage. As most of these materials had been known since 1945, their late use requires explanation. This paper hypothesizes that there exists a causal relationship between: the second generation's unresolved inquiries about World War II; the availability of Holocaust imagery; and the selective appropriation of these images in contextualizing the murder of Jews historically – a process that encountered resistance from both perpetrators and bystanders. In essence, it therefore suggests that the shaping of social memory concerning the Holocaust in the early 1960s is largely influenced by repressed memories that were, at best, indirectly transmitted to post-war generations. However tempting it might be, it is imperative, in my view, to clearly differentiate this process from what Marianne Hirsch terms “Postmemory.”16 The younger segment of German society seeking understanding was not grappling with latent trauma; rather, they were confronting the denial inherent in their families' complicity as perpetrators. This phenomenon bears a closer resemblance to Alison Landsberg's concept of prosthetic memory. The traumatic history of World War II and the persecution of European Jews were encountered vicariously through documentary films and footage, serving as a surrogate experience. It is only through this mediated lens that the memory of these atrocities became integrated into Germany's social or collective consciousness. Indeed, it is more accurate to describe this phenomenon as prosthetic rather than post-memory, as it did not involve a reconstruction of either the perpetrator or bystander experiences. Instead, it adopted a seemingly impartial but empathetic perspective that identified with the victims, rendering the perpetrators as faceless, anonymous wrongdoers.

Audience reactions, documented in newspaper inquiries and public discussions, reveal that the gradual replacement of individual, private memories of perpetrators, victims, and bystanders with a new, public narrative about the persecution of European Jews began in Germany in the late 1950s.17 Frequent media references to the Westerbork material indicate that its early image migration strongly influenced the formation of social memory concerning the murder of the Jews, suggesting a link between this film and the negotiation between first and second generations in Germany. The material's status as unpublished and newly discovered likely facilitated a quasi-naïve, secondary, and cross-generational historicization of the murder of the Jews, using footage that, unlike newsreels and propaganda films, was also unfamiliar to first-generation perpetrators, thus creating distance from the crime. Its appearance in the late 1950s coincided with and contributed to the emergence of a Holocaust narrative. As a mostly secret project, the genocide left few traces in official films, and until the late 1950s, the effort to eliminate all European Jews was not simply forgotten, especially in Germany, but remained a contested memory.18 The initial interest of the second generation in its background and the sense of guilt of the bystanders outweighed all attempts at repression by the perpetrators, and so the interplay of critical film productions such as Leiser's MEIN KAMPF and the accompanying debate in the media gave rise to the formation of a visual history of the Holocaust in the German public. The Warsaw ghetto film, the LIEPAJA EXECUTIONS FILM and the Westerbork film resonated in this newly emerging and rapidly spreading Holocaust narrative. Today, the girl in the door of the freight car from the Westerbork film and the Jews crossing the wooden bridge between the ghettos in the Warsaw Ghetto film are considered iconic Holocaust images. This status is the result of a change in hegemonic social memory in the late 1950s and early 1960s, a change the Westerbork material contributed to.

This essay explores the image migration of the Westerbork film, tracing this history back to the mid-1940s. It analyses the production of the footage and reconstructs the history of its utilization. Images in general are migrating at the mercy of curators, in the case of films these curators are directors, archive producers19 and producers. The Westerbork footage has become part of such choices more often than other material and is therefore a relevant example for the examination of image migration in the context of the formation of Holocaust remembrance. But before we turn to the analysis of its migration, the following chapter provides an overview over the production of the Westerbork material.

The Westerbork Film

Camp Westerbork was established by the Dutch government in mid-July 1939 as a facility to house Jewish refugees from Austria and Germany who had fled to the Netherlands to escape Nazi persecution. It offered space for about 1,000 inhabitants, mainly families, and was the largest of its kind. Westerbork is well-known today mainly because the SS chose it to be the central transit camp for the deportation of Dutch and emigrated German and Austrian Jews and Dutch Sinti to the extermination camps in Poland. The camp's facilities, many of them visible in the footage, included a laundry, a boiler house, a large-scale kitchen and a hospital, a multi-purpose hall with a stage used for all kinds of gatherings and as a registry for incoming transports, a construction department, a carpentry workshop, a blacksmith's shop, an electrical engineering department, sewing workshops, a shoemaker's workshop and a toy workshop. In the first phase of the camp between 1939 and 1941, a self-administration was formed, i.e. all departments such as the hospital, the registry of new arrivals and the workshops were run by Jewish heads of service (Dienstleiter), most of them German Jews. In June 1942, an SS unit moved into quarters and the camp now operated under the name Judendurchgangslager Westerbork. After the completion of the new barracks, the quartering of Dutch Jews in Westerbork began in June 1942 and from July 15, 1942, deportation trains left for the extermination camps in the East, initially from Hooghalen, about 5 km away. From November 1942, there was a railway track that reached directly into the camp. Until September 13, 1944, 99 transports left Westerbork for the East. More than 106,000 people were deported, most of them to the extermination camps Sobibor and Auschwitz. Fewer than 5,000 deportees returned after the war.20

Various exemption lists were considered when the transports to the East were put together. Those who worked in the administration or in one of the workshops were given a place on the Stammliste (permanent list) and had a good chance of staying. This led to considerable tensions between the so-called alte Kampinsassen (old camp inmates), who mostly preferred their German compatriots when it came to filling the lifesaving working posts, and the Dutch, who often lived in the camp for only a few days or weeks before being deported further. Part of the camp administration was the Fliegende Kolonne, a group of younger men and women who helped the deportees when the trains arrived and departed, as well as the Ordnungsdienst, a kind of internal police force, provided by the inmates themselves, who, for example, ensured that the deportations proceeded in an orderly manner. In January 1944 the majority of the old camp inmates, the Austrian and German Jews that represented the only group of resident inmates, were deported to Theresienstadt. Only some of the department leaders remained in the camp. By spring 1944, the number of Jews being brought to Westerbork each month had massively decreased. As a result of rumours about gas chambers and mass killings in the East, which were taken seriously at the latest since their publication in the underground newspaper Het Parool in the summer of 1943, fewer Jews came to Westerbork voluntarily. And as Germany's chances of winning the war diminished, the plans to deport the entirety of Dutch Jews were postponed or at least no longer considered the most pressing issue in Berlin. During this time of change in spring 1944, camp commandant Gemmeker suddenly developed great activity: a self-printed currency was circulated, a department store and a cantina opened, more attention was paid to the workshops, and a film camera was acquired and brought to use.

Filming in the Camp

At a time when the deportations were about to end, if only temporarily, camp commandant Gemmeker decided to produce a film about his Durchgangslager. The first event to be filmed was a Protestant Sunday service held, most likely on March 5, 1944, among Jews that had converted to Christianity. This caused serious trouble, as two members of the congregation protested against the intrusion and Gemmeker felt entitled to set an example by sending both to the penalty barrack – a punishment that usually meant short-term deportation and death. Though Gemmeker released them before the next deportation, he had made his determination to film in the camp – without interruption – more than clear. Soon after this event, first a train arriving from Amsterdam was filmed, then, on March 20, a group of devastated inmates from the concentration camp Herzogenbusch while disembarking another train in Westerbork. During his trial after the war, Gemmeker claimed that he had wanted to protest against the conditions in other camps with these recordings. While this sounds rather unlikely, one cannot rule out that he had this event filmed in anticipation of the need to defend himself after the war. Since the quality of the developed 16mm material was not satisfying, Gemmeker urged his subordinates to get a better camera and on March 26, the camera that had been used for the visibly inferior shots from the two incoming trains was replaced by a better Siemens model.21 Around this time and most likely due to the problems with the camera, Gemmeker seems to have consulted Rudolf Breslauer, the camp photographer, who then tried to get a 16mm film viewer (an apparatus that enables watching a 16mm film on a small screen) and to trade his own 8mm cameras for a better 16mm model, both to no avail.22 For a while, Gemmeker's name appears regularly on footage orders and other correspondence concerning the filming. But after he unsuccessfully tried to order a viewing apparatus himself, Gemmeker appears to have delegated the filming back to the camp inmates, namely to a man named Kloot. Already on April 14, Kloot reports problems also with the Siemens camera and asks the Agfa developing laboratory how to achieve better contrast and fewer dark images.

Unfortunately, the few surviving documents allow to reconstruct the shooting process only fragmentarily. In fall 1944, Gemmeker had all files concerning the camp he could get hold of destroyed and only a few letters, possibly duplicates stored in the photographic laboratory, survived. However, a treatment from the first development period of the film suggests that the aim was to make a promotional film for the camp that centered around the person of the camp commandant.23

On May 19, 1944, an outgoing transport was filmed and since Gemmeker appears prominently in the footage, one can assume that he specifically ordered it to be filmed. Part of the transport was heading for Auschwitz but the main reason for the filming was, with some certainty, a group of Dutch diamond industry workers, so-called ‘diamond Jews’, who were transported to Bergen-Belsen on direct order of Heinrich Himmler on the same day.24 This transport was considered so important that Adolf Eichmann himself came to Den Haag for a meeting with Gemmeker and others to ensure safe proceedings.25 More than fifteen years later, during his trial in Israel, Eichmann recalled this particular deportation as the main reason for his visit.26 Most likely Gemmeker planned to record the deportation to show his superiors how well organized and smoothly it had been carried out. It is precisely this material that later would become one of the most famous pieces of footage in Holocaust documentaries and a common illustration of deportations. Until September 1944, the majority of the interned were deported to the East without being replaced by new arriving internees and the camp was downsized from an average of 6,000 to 9,000 inhabitants to a few hundred. However, Gemmeker managed to convince his superiors to keep the basic camp intact, to be able to deport the rest of the Dutch Jewry in the future. Westerbork was liberated by the Canadians on April 12, 1945. Commandant Gemmeker and the SS had fled to Amsterdam the day before and had taken the Westerbork film with them.27

Material History

The surviving material, played in the original 16 frames per second, consists of roughly 150 minutes of film. The newly restored digitized version of the film that was made available by the Nederlands Instituut voor Beeld & Geluid (Netherlands Institute for Sound and Vision) in 2021, begins with battery recycling, various workshops, the dentist, the laundry and the famous deportation sequence. The image quality of these first fifteen minutes is very good since they originate from a negative reel that resurfaced only recently at the EYE Film Instituut Nederland. What follows the well-known deportation scenes from the so-called “third train” going to Auschwitz and Bergen-Belsen, are the two abovementioned incoming trains, first families from Amsterdam, then prisoners from camp Herzogenbusch and, very blurred, the registration of newly arrived inmates in the room where on other occasions the cabaret or Lagerbühne (camp stage) performed. This is followed by the scrapyard and metal recycling in the barracks, separating aluminum foil and paper, and various workshops: a sewing room, a cobbler, a children's toy manufacture, a carpentry, a locksmith's shop, a brush maker, and the construction of greenhouses. Then the camera takes a trip by narrow-gauge railway to the Oranje canal, where bricks are unloaded from a barge and onto the carts of the narrow-gauge train. The ride continues to a farm, then on to a field where potatoes are sown and eventually the bricks are unloaded and used for the building of a sewer canal. A short passage from the camp's wood industry (logging and sawing) is followed by a soccer game on the former Appellplatz (daily roll call ground), attended by a couple of hundred inmates, then women's gymnastics, and the Sunday service. The film concludes with cabaret performances. Two reels with outtakes and the visible traces of edits and cuts in the film material hint to one or even several phases of editing that today can no longer be reconstructed or dated. It is possible that editing took place before the liberation in 1945 but at least some of it happened after the material resurfaced in 1947 or even in 1986, when it was re-assembled and transferred to the Netherlands State Archive (RVD). Reconstructing the film's history is challenging because, aside from the newly found negative and a brief portion of the Sunday service, none of the surviving materials are originals.

At first sight the frequent appearance of trains and railways is striking. Not only the deportations but also traffic within the camp ran on rail vehicles and even in some of the workshops, tracks connect the work benches. The material is often referred to as “industrial film”, but most of the work filmed is for the upkeep of the camp. The “timber industry” probably produced firewood and material for small repairs in the camp, the laundry, sewing shop, locksmith's shop and carpenter's shop were repair workshops for the camp. Only the children's toys, the brush makers and the bag sewers, as well as the battery recycling and the scrap metal recycling were sort of ‘commercially’ oriented, and only for the children's toys is there evidence of one single sale to a company in Amsterdam.28 To be precise, Westerbork was never a labor camp. The filming also omits a lot of things. Neither the living quarters nor the sanitary facilities were filmed, and the course of a regular deportation as it is preserved in many eyewitness accounts was different and more brutal than the one depicted in the film.

The persecution of the European Jews has been documented by filming perpetrators, privately and officially. Within this corpus, the Westerbork film belongs, together with the Theresienstadt film, to a special category of deviating propaganda films that show the internment or transit camps for Jews counterfactual as friendly facilities. Most prominently the Theresienstadt film from 1944 represents the propagandistic attempt to deceive its audience and to prove the rumors about an ongoing genocide as hostile propaganda.29 While it is rarely used, and primarily to document this particular kind of propaganda, the Westerbork film is typically employed for its seemingly neutral documentation of events. The following chapters reconstruct the utilization history of the Westerbork film by analyzing the uses quantitatively and qualitatively and by connecting them to the discourses that emerged around the material, hence rendering the dense web of relations around the film tangible. In the process, another level of meaning of the material becomes visible, which has developed and established itself as a quasi-individual cinematic memory, independent of and partly in contrast to the case structure initially recorded in the material. The particular use of this material within the context of empathetic Holocaust remembrance followed a process of selection and appropriation that is being brought to relief through the reconstruction of its image migration.

Image Migration Analysis

Since the deportation sequence is the only one that has been utilized to a larger degree, the comparative study of Westerbork image migration focuses on this part of the film. The roughly 13 minutes show two incoming trains (March 1944), the registration of new camp inmates and the deportation to Bergen-Belsen and Auschwitz on May 19, 1944, altogether 100 single shots mostly of deportees on the improvised platform. Uniformed personnel appear in one third of the material, seven shots show the trains without a person visible. The material from the third train suffers from a malfunction of the camera and features many irritating double images.

It is tempting to analyze image migration within national borders, and groundbreaking work in this field, such as Judith Keilbach's analysis “Zur Darstellung des Nationalsozialismus im bundesdeutschen Fernsehen,”30 was following this approach. But the Westerbork footage from the start migrated across countries and communities. Limiting its analysis to national production contexts means missing out a large part of the phenomenon. This comes with a methodological peculiarity that all image migration analyses share: the relevant corpus of films cannot be limited by predefined aspects – the images migrate unpredictably along a transnational culture of use and not within otherwise recognizable boundaries. Still, the filmography of carrier films gathered during the first three years of the Filmikonen project seeks to make both possible: to analyze image migration in National Socialism documentaries (including comparisons to films that don't use footage) and to follow image migration routes that lead away from this corpus. It consists of roughly 8,700 titles and lists a comprehensive collection of TV and cinema documentaries and also some feature and art films that carry iconic footage. Roughly 4,400 titles are available digitally and have been analyzed in regard of the use of archive film material.31 555 films, episodes and audio-visual media (almost 13%) use footage from the Westerbork film. Hence, it is safe to say that the audio-visual traces of Westerbork play a vital role in illustrating the Holocaust. Only two thirds of these films focus on the persecution of the European Jews. The remaining third touch on the genocide as a side matter: 124 are about National Socialism in general, 56 center on World War II and 23 films only indirectly relate to National Socialism or the Holocaust. This underlines the importance of the material: it is often chosen to represent the Holocaust, if symbolically, even in contexts that focus on other subjects.

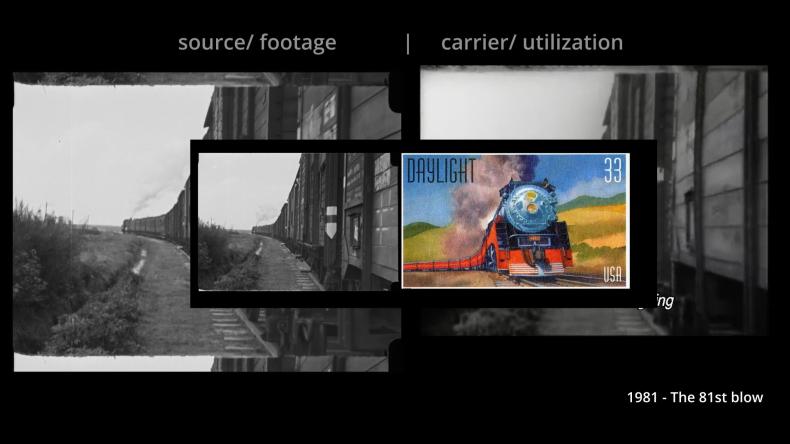

Two types of image movement can be observed. Images either literally migrate from one film to another, or they can appear, according to various patterns, taken from an archive. According to our data, complete repetition of previous uses is exceptional. Rather than simple copy-and-paste operations, adaptations typically involve partial selections from montages. These abridged or slightly varied appropriations of Westerbork material passages represent a characteristic usage pattern within this footage's cultural application. Surprisingly, the mathematical diversity of utilizations is remarkable. Hence, the use of Westerbork footage represents not merely repetition of iconic images, but rather permutation of a specific shot repertoire.

From the outset, the Westerbork footage has often been used in combination with footage of deportations in Poland, here referred to as DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS. Almost two thirds of the films that utilize Westerbork footage also feature this material and usually both are indistinguishably montaged together. The other material that is regularly used in the same documentaries is footage shot by the Soviet cameramen after the liberation of the concentration camps in Auschwitz, namely the children showing their number tattoo and the iconic areal shot of the barracks in Birkenau. From the 1990s onwards, both materials often appear together, Westerbork illustrating the deportation and the Auschwitz footage representing the extermination and labor camps.

The First Utilizations

Three films mark the inception of the image migration of the Westerbork footage. The first one is Alain Resnais' NUIT ET BROUILLARD (FR 1956) and the second one the GDR production EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK (GDR 1958) by Joachim Hellwig. The third, the West German TV documentary ALS WÄR'S EIN STÜCK VON DIR! (DE 1959), directed by Peter Schier-Gribowsky, though less impactful, completes the initial phase of image migration. These three cover a big part of the variety of later uses and they embody diverse approaches: sober documentation (ALS WÄR'S EIN STÜCK VON DIR!), symbolic or typifying use (NUIT ET BROUILLARD) and dramatization (EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK). While Resnais employs the footage of the third train as generic illustration within his typifying collage about the slave labor camp system, the other two refer to the context of the deportation of Dutch Jews, and the West German film even names the production context. All three films vary in their choices of up to 40 shots.32 Only six shots are common among them (though all of those are among the ten most often used shots of all times). The resemblances between NUIT ET BROUILLARD and EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK (for example, both make use of the same shots from the DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS footage) suggest a strong influence of the French production, even though archive records document that director Hellwig personally acquired the material from the Dutch archive. All three films accompany the footage with a score, albeit very different ones. The West German utilization comes with a slow and dignified piece of organ church music and scarce commentary; in EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK the footage is accompanied by a fast and aggressive score with a demanding voice-over; in NUIT ET BROUILLARD the footage is set to Eisler’s variation of the German national anthem with no voice-over, which results in a particular emphasis on the footage from Westerbork as it is treated differently than the other materials. EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK additionally uses the footage as illustration for the arrival in Auschwitz, an impressive but misleading use that has been and continues to be repeated in documentaries ever since. The three films noticeably influence other film productions that followed shortly after. Parts of the montage from EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK can be found in Erwin Leisers MEIN KAMPF, in AKTION J (GDR 1961) and in the short film BUCHENWALD (GDR 1961), while the succession of shots from NUIT ET BROUILLARD partially re-occurs in the West German TV-series DAS DRITTE REICH (DE 1961). Such utilizations of parts of the montage from NUIT ET BROUILLARD can even be traced until recent years.33 ALS WÄR'S EIN STÜCK VON DIR! likewise left its marks in the history of utilization. Director Schier-Gribowsky soon afterwards produced two other TV documentaries using Westerbork footage: AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS (DE 1961) where he featured the LIEPAJA EXECUTIONS FILM for the first time, and BERICHT ÜBER ERICH RAJAKOVIC UND WILHELM HARSTER (DE 1963) which repeats about half of the Westerbork montage from ALS WÄR'S EIN STÜCK VON DIR!. The influence of NUIT ET BROUILLARD on Holocaust remembrances cannot be overrated, but EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK, too, had a certain effect at least on the historicization of Camp Westerbork: the investigations in Germany against former camp commandant Gemmeker only began after someone had made the state attorney in Düsseldorf aware of a scene from the documentary that shows Gemmeker living as a free man in West Germany.34 The Westerbork footage, right from the start, migrated across all sorts of borders, even across the Iron Curtain. And from the beginning, the Westerbork footage was not merely transferred from the archives into documentaries, but the published films themselves turned into archives and, even more importantly, they influenced the choices of other film productions noticeably.

With DAS DRITTE REICH (DE 1961), it is a West German TV documentary that uses the Westerbork material for the first time in a way that would shape its role in collective visual memory: as a generalized representation of the deportation of European Jews, with a particular emphasis on evoking empathy for the victims depicted. Photos of elderly Dutch Jews are commented with the compassionate and only subtly accusatory voice-over “People like these” and then the film cuts to the Westerbork footage. This is also striking, as this montage appears to be taken directly from NUIT ET BROUILLARD, which was not even referring to Jews explicitly. However, by the time DAS DRITTE REICH was released, NUIT ET BROUILLARD had already been appropriated by the German audiences as empathetic Holocaust documentary, despite its lack of reference to Jewish victims, and partially due to the use of the Westerbork material. More important than the intentions of the producers and the actual focus of films like NUIT ET BROUILLARD and MEIN KAMPF was how they were perceived by the audience, especially in Germany. Selectivity as a genuinely remembrance forming activity appears here as twofold: as preserving images as such and as appropriating narrative structures attached to images separately. Films that are using the Westerbork material prominently, such as NUIT ET BROUILLARD and MEIN KAMPF are appropriated as empathetic documentary films about the murder of the Jews even though in MEIN KAMPF the persecution of Jews covers only a small fraction of the film and NUIT ET BROUILLARD does not even mention the Jews. In both cases, newspaper reviews and viewer surveys regularly refer to the scenes from the Westerbork platform when categorizing the films as Holocaust documentaries. Such instances of ‘selective appropriation’ appear to be integral to the process of remembrance formation as a systemic function of the remembrance community, wherein images aligning with the current requirements of a remembrance take precedence. In other words, it is not merely the availability or content of such images (or even the way they are contextualised) that grants them significance, but their ability to take on a specific role within a given moment of social reconciliation that ultimately determines their lasting impact. This is where the iconic potential of the Westerbork material becomes tangible.

A Culture of Use

The Westerbork film was used as evidence during the Eichmann trial in 1961. With a little delay the Westerbork footage also appeared in documentaries in the US, such as LET MY PEOPLE GO: THE STORY OF ISRAEL (US 1965), GOOD TIMES, WONDERFUL TIMES (US/GB/IL 1965), THE LEGACY OF ANNE FRANK (US 1967), and eventually in the miniseries THE RISE AND FALL OF THE THIRD REICH (US 1968). Even later, it appeared in documentaries made in Israel such as THE 81ST BLOW (IL 1974) and the TV series THE PILLAR OF FIRE (IL 1981). While the US productions largely adopted the European approach of an emotionalizing Holocaust remembrance, THE 81ST BLOW in particular utilizes the Westerbork footage in a different way. Here, the heroic Holocaust remembrance leaves no space for victim identification by the bystanders and the offspring of perpetrators. In THE 81ST BLOW, the Holocaust is not divided into a peaceful outside and a brutal inside of the camps, but persecution and violence always dominate the experience of Jews.

Parallel to the utilization in Israel, a new phenomenon enters the documentaries in Europe – the perpetrator witness. Most notably in the TV Series THE WORLD AT WAR (GB 1974), witnesses such as Himmler's Chief of Personal Staff Karl Friedrich Otto Wolff and Hitler's secretary Traudl Junge suddenly complement the use of archive footage and tell their distorted, apologetic versions of the past. This goes along with an almost revisionist approach to reforming Holocaust remembrances that is also noticeable in the historical narrations. First in the UK and then in Germany and other European countries, documentaries question the hitherto empathetic Holocaust remembrances. Especially alleged and documented collaboration of Jews in the Holocaust is suddenly introduced into discourses about guilt and responsibility also in mainstream productions. However, the tragic perspective on the Holocaust, that acknowledges the victimhood of the murdered, prevails. In 1981, the German Holocaust documentary DER GELBE STERN (DE 1980), which follows this approach and incorporates Westerbork footage, was nominated for an Academy Award. The following year, GENOCIDE (US 1982), also utilizing Westerbork material in a similar empathetic manner, won an Oscar. The famous shot of the Sintezza Settela from the Westerbork film (see figure 6), looking at us from the door of a cargo train, even makes it into Godard's seminal essay film series HISTOIRE(S) DU CINEMA (FR 1988-1998) – not just once but twice. Since the 50th anniversary of the end of the war, there has been a significant increase in the production of Holocaust films in general and so roughly three quarters of the identified films using shots from Westerbork have a production date after 1994. Yet the most important events for the Westerbork film were still to come: the identification of the famous girl in the door of the freight car, Settela Steinbach, and the related publications in the Netherlands in the 1990s. These triggered a final reshaping of the narrative about the film's provenance, bringing it to wider public attention, first in the 1990s in the Netherlands and subsequently, roughly ten years later, internationally.

As already noted above, the precision of the variation of shot combinations, the omission of certain parts of the footage and the recurrence of certain uses and patterns hint to a social memory about how other filmmakers utilized the material beforehand. These uses betray a certain awareness of others using the same material which could be called an organizational memory of the archive producers.35 Despite these variations, the repeated use of the recognizable footage had an overall affirming effect, and the Westebork film became part of a social memory, first in the production contexts and then within the broader collective remembrances. While certain iconic shots from the Nazi period, such as Hitler grinning or Hitler anxiously drinking from his cup at the Wagner mansion vanished after a phase of repeated use in documentaries, certain shots from the Westerbork film have acquired a steady place in the collective imageries since the 1960s. But this place was also disputed, and the material has been recontextualized in many ways throughout the decades. Following the turbulences of the 1970s mentioned above, two significant events further influenced this culture of use. The discovery of the Sinti identity of the girl with the headscarf, Settela Steinbach, the best-known image from the Westerbork film in 1994, which resulted in a less frequent use of her image, and, shortly before, a change in the availability of the footage that occurred in the late 1980s. When the Westerbork film was transferred from the RIOD (Netherlands Institute for War Documentation, today NIOD) to the archive of the RVD (Netherlands Government Information Service; in 1997 this archive became part of Beeld & Geluid) in 1986, the latter started to circulate an edited version of the Westerbork film which was missing four shots from the original material of the third train and streamlined the events depicted.36 When I was starting to analyze the utilizations of the Westerbork film, this change in the use was quite obvious. Films made after 1986 that had licensed the material legally from the Dutch archive were not using these shots anymore. Today, with four times as many examples of utilizations of the Westerbork material, the picture has changed. Documentaries and art films with a small budget especially tend to use archive footage without licensing it, often by simply copying it from older films. Hence, the effect of the four so-called ‘outtakes’ vanishing from the officially circulating material became statistically irrelevant and was therefore compensated within the collective imageries. Nonetheless, the inavailability of the four outtakes between 1986 and 2019, when they were rediscoverd during an inventory of the material, left its traces in the history of utilizations. This technique of cannibalizing other films, which started in the analogue time but was made far easier in the digital age, adds to a broader awareness on the side of the producers of how the material is utilized and might partly be the cause for both the high degree of differentiation between uses and the existence of a shared cinematic memory that results in a manifest culture of use.

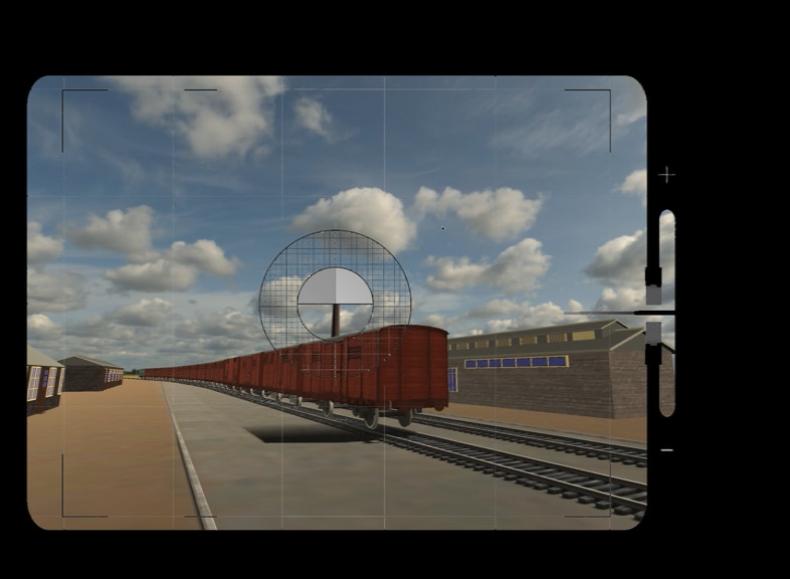

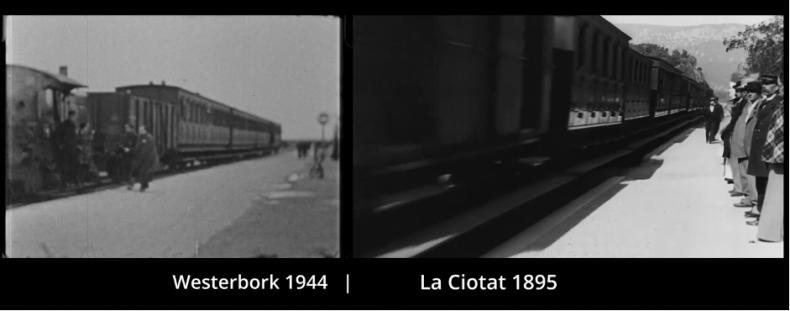

Commemorations vs. Historiography

The ongoing presence of the Westerbork film has several reasons. The intense emotional effect of the shot showing Settela Steinbach and the peacefulness of the deportation proceedings made it an important and fitting document for the emerging Holocaust remembrances in the early 1960s. At least in Germany, the footage replaced the witness reports of perpetrators and bystanders who were not willing to take part in the process of historicization of the genocide. Certainly, premeditation also played a role here.37 The train in the deportation sequence is the same model as the one from the famous Lumière short film from La Ciotat dating back to 1895/6 and camera angle and composition resemble each other.

The deportees carrying bags and suitcases are reminiscent of scenes from any train station that most audiences are familiar with from personal experience as well as feature films. But to gain the status the material has today, there was one more step of narrativization necessary. A transformative step that elevated the Westerbork film from one of the most virulent but at the same time widely unknown documents of the Holocaust to an iconic piece of footage. The dominant historical narrative regarding the Westerbork film as of today names the German inmate and official camp photographer Rudolf Breslauer as sole director and/or cinematographer of the film in an almost auteur-like manner. This hasn't always been the case, at least not in this simplicity and the surviving documents and witness reports do not favor this theory. However, the uncanny deportation scenes seem much easier to handle, once they are modelled into the gaze of a victim, and the story of the inmate who makes a film and therefore communicates with us, speaks to the international remembrance communities of today, opening a channel to the history of Westerbork. From this viewpoint, the Breslauer narrative as part of the cinematic memory of the Westerbork film could be seen as an example of the successful transformation of a piece of footage into a monument – a footage that shapes our imagination of the deportations and specifically counters Nazi depictions of ‘the Jews’ until today. Obviously, the story of Rudolf Breslauer filming has a strong appeal to all kinds of audiences, and it has sunken in so deep into the collective memory already, that it seems unlikely that this process could be reversed or corrected. Unless this leads to the misunderstanding that he was an artistic collaborator rather than a victim compelled to work on SS propaganda, there may be no need for correction. However, from a memory studies perspective the emergence of the Breslauer narrative merits scrutiny. At the core of this development towards a monument lies a process of remediation and of augmentation of the film's cinematic memory.

In the 1990s, Camp Westerbork in general and the film in particular received new attention thanks to three publications. The first was Willy Lindwer's influential book and film about the camp from 1990, Kamp van Hoop en Wanhoop. Lindwer extensively illustrated the memories of survivors and bystanders with photos by Breslauer, whom he introduces as an 'archivist of the camp.'38 While the film is only mentioned in passing, Lindwer is amalgamating it together with the photos into Breslauer's ‘complete works’. Willy Lindwer is the first to name Breslauer exclusively as the sole cinematographer of the Westerbork film.39 The second event relevant to the solidification of the Breslauer narrative and to the legitimization of the footage, is the identification of Settela Steinbach by journalist Aad Wagenaar. Wagenaar's consequential discovery for Holocaust remembrances – that the girl with the headscarf (Figure 6) was not a Jewish girl as previously assumed, but a Sinti girl – was first published in a Dutch newspaper report. Cherry Duyns documents the history of this discovery in the documentary film SETTELA, GEZICHT VAN HET VERLEDEN (NL 1994).

Alongside the careful reconstruction of the girl's true identity, the documentary also constructs the implausible, counterfactual story of camp inmate Wim Loeb who edits two different Westerbork films from the material Breslauer allegedly had shot. In his recollection, Loeb hands the propagandistic version to camp commandant Gemmeker and smuggles a more subversively edited, accusatory one out of the camp. The documentary suggests that this subversive version is the one circulating today. This narrative had what it took to erase any remaining reservations about using the film. Being made by the SS, it now turned into a neutral, even subversive documentation of the camp. This account was then, and this is the third publication relevant to this development, largely uncritically adopted by Broersma and Rossing in their 1997 booklet Kamp Westerbork gefilmd, consolidating the narrative of the film having been directed by Breslauer for good. However, the renewed interest in the film resulted in survivors recognizing themselves and had a positive effect in promoting the Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork. In 2021, Broersma and Rossing published an updated valuable hardcover edition of the booklet.40 Once again and even more than the first edition, this update is successful in interweaving the story of the Westerbork film with the fates of Holocaust victims and survivors vaguely identified in the material and is therefore an important contribution to the renewal of Holocaust remembrance in the Netherlands.

However, the cinematic memory of the Westerbork film had not yet achieved full international awareness and acknowledgement. What followed, was a true act of traveling memory: the migration of the aforementioned narratives from Lindwer, Wagenaar, Broersma and Rossing to the cosmopolitan Holocaust remembrances by way of Harun Farocki’s short film AUFSCHUB (RESPITE, DE/KR 2007). For nearly half a century, the Westerbork film had been an iconic and integral part of Holocaust remembrances – widely recognized in imagery, yet its origins remained largely unknown to the international public. Now, it was poised to step onto a grander stage. Farocki sensed the aesthetic potential of the Dutch cinematic memory of the Westerbork film and appropriated it, without adding much. He translated the core elements of the 1997, exclusively Dutch, publication Kamp Westerbork gefilmd into his silent film and therefore made them accessible to an international audience. Many essays referred to or were even written about Farocki’s AUFSCHUB which soon became a frequently mentioned artefact within the academic discourse and is considered a prototype of re-reading archive material.41 The inclusion of the Westerbork film in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2017 was in part a reaction to the attention the film had gained within Holocaust studies and in the public eye thanks to Farocki’s enhancement. Today, Rudolf Breslauer as its auteur is inseparably linked to the history of the Westerbork film, and as long as this serves as a motivation to deal with the history of Westerbork, there is perhaps no reason to change this narrative. At the same time, an academic analysis of the film's history and the history of its utilization must distinguish between established commemorative interpretations and reconstructible or at least probable historical events. Since it was shot under the surveillance of the SS in a transit camp in 1944, the Westerbork film has not much documentary quality and testimonies bear this out.42 It obviously does not document what the perpetrators wanted to conceal with it – what it meant for the Jews to live in the transit camp. As the filming of the Sunday service reveals, the perpetrator gaze is built into the very architecture of the film. It was produced under duress, and for that it arguably does not matter who ultimately pressed the camera trigger.43 However, this inherent tension – between the film's origins as perpetrator propaganda (viewed through a historiographical lens) and its current iconic status in Holocaust remembrance – is not a flaw to be rectified. The film plays an important role today as a carrier of an empathetic Holocaust remembrance and this is a function that it also has to fulfil, in addition to its role as a source or document of specific events.

Conclusion - A Healing Cinematic Memory

As could be demonstrated, the Westerbork film did not merely illustrate Holocaust documentaries. From the beginning, it was appropriated by the emerging remembrances, and it was brought to a certain use that in return shaped its cinematic memory. The Westerbork film determined how the deportations were perceived but even more importantly, how European Jews during World War II were and are imagined today. The Westerbork material was given a second, parallel existence that detached it from the historical case structures recorded in the material. The ubiquitous references to the documentary character of the footage, especially in publications since the UNESCO honors, are part of the appropriation of the footage within Holocaust remembrance. Being as it is an embellishing propagandistic gaze disguised as a documentary film should have made it a difficult case for utilization: as a document the deportation sequence is precarious, unless we want to document propaganda or perpetrator gazes or the specific case of the deportation of a small and privileged minority in Westerbork – the gem cutters. But most stunningly, its use resulted not only in a neutralization of the perpetrator gaze but even more importantly in empowerment and an inclusion of the victims. The compassionate voice-over in DAS DRITTE REICH sums it up best: “people like these” (meaning: people like us). The cheerful mood of the deportees on their way to Bergen-Belsen is misinterpreted as naiveté and that allows for these images to unfold their actual effect of including ‘the Jews’ into the community of the audience, of de-detaching them. This interpretation or reading of the footage is by no means a necessary or logical one. It is an achievement of the interplay between curators' choices and an audience going through a process of remembrance formation and eventually appropriating these choices in an unpredicted way. To a degree, the newly emerging remembrances communities selected these images. This precarious process of gradual convergence, which in retrospect seems obscured, is rooted in the iconic qualities of some of these shots, which turned into key images of Holocaust remembrances. Hence, the 'misuse' of the Westerbork film – footage depicting an atypical, unusually orderly deportation representing the brutal reality most victims experienced – could be excused or understood as a fortunate one. Furthermore, propagandistic stereotypes are not repeated. We see Dutch and German deportees, and evenutally European citizens and not what the NS propaganda constructed: stereotyped Judentypen (Jewish types). The Westerbork film added to the historical reappraisal of the Holocaust by confronting the postwar societies with an image of the Jews being deported that they couldn't distance themselves from. This effort to restore the humanity of Holocaust victims remains fragile, continually undermined by the dehumanizing representations found in NS propaganda films and newsreels, like the still-utilized Warsaw Ghetto Film. Therefore, employing the Westerbork film to renew this humane gaze, supported by its historical narratives, represents not careless repetition, but a conscious act of resistance against forgetting.

Analyzing the utilization of Westerbork footage from a combined production studies and memory studies perspective proved to be a worthwhile approach to explore the interplay between transnational image migration and remembrance formation. The reinterpretation of its cinematic memory towards an erasure of the inherent perpetrator gaze and its overall euphemistic impetus, which happened along these recurrent uses, made the Westerbork film an important asset of the cosmopolitan Holocaust remembrances. The detailed reconstruction of the Westerbork material's image migration revealed it to be a fractured, non-linear process with numerous unexpected detours and divergent paths. This complex trajectory illuminates the material's crucial but often overlooked role in shaping Holocaust remembrance during the formative period of the 1950s and 1960s. The quantitative analysis applied led to a shift in focus away from single, frequently used shots such as the one of Settela Steinbach towards the deportation sequence as a whole and its function as a humane gaze on deportations and the Holocaust in general. In combination with its precarious status as propagandistic perpetrator footage, this function within Holocaust remembrance can explain the at times idiosyncratic historical narratives found in public remembrance culture, such as the Breslauer story, as strategies of legitimization.

Today, the Westerbork footage functions as a symbol for the Holocaust, appearing even in films about other atrocities. Like a visual trademark, it conveys the humanity of the victims and anchors remembrance in everyday life. But it does more than represent: it connects. The footage serves as a portal to a complex network of narratives – some even contradictory – linking personal memories and collective history. Rather than a fixed iconography, it acts as a dynamic node in a living memory culture. What is perceived as overuse often is, in fact, a sign of active remembrance: a deliberate choice by filmmakers to build connections and emotional resonance. Each use situates the footage anew – through editing, sound, and narration – creating links to so far unknown images and stories. In its recognizability, the footage serves as a connecting denominator. The newly raised questions of pre-1945 complicity and post-1945 denial, mentioned in the introduction, are an important part of the ongoing historical research on the Holocaust, and this research should, of course, include the film materials. However, as the here presented investigation of the image migration of the Westerbork film is meant to make understandable, iconic audiovisual materials also serve a function within cultures of remembrance, and there's a growing need to acknowledge that these two contexts are not entirely compatible, even if each has its own distinct value.

Acknowledgement: Parts of this text have previously been published in German and in a slightly different form as part of my doctoral thesis "Der Westerborkfilm. Bilderwanderung und Holocausterinnerung" (2025).

- 1

See Sylvie Lindeperg, Nuremberg, la bataille des images (Paris: Payot, 2021); Natascha Drubek, Vernichtung und Befreiung. Die Rhetorik der Filmdokumente aus Majdanek 1944-1945 (Wiesbaden: Springer SV, 2020); Ulrike Weckel, Beschämende Bilder (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2012/I).

- 2

See Otto Dov Kulka and Eberhard Jäckel, ed., Die Juden in den geheimen NS-Stimmungsberichten 1933-1945 (Düsseldorf 2004/I); Frank Bajohr and Dieter Pohl, Der Holocaust als offenes Geheimnis. Die Deutschen, die NS-Führung und die Alliierten (München: C.H.Beck, 2006); Frank Bajohr and Dieter Pohl, Massenmord und schlechtes Gewissen (Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2008); Bernward Dörner, Die Deutschen und der Holocaust. Was niemand wissen wollte, aber jeder wissen konnte (Berlin: Propyläen Verlag, 2007). Internationally, the topics of connivance and complicity were discussed in 1996 in the context of the publication of Hitler's Willing Executioners by Daniel Jonah Goldhagen.

- 3

The paradigm of ‘digital visual history’ was introduced by Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, see Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Noga Stiassny, and Lital Henig, “Digital visual history: historiographic curation using digital technologies,” Rethinking History, 27:2 (2023): 159-186, DOI: 10.1080/13642529.2023.2181534.

- 4

The number of documentary films about National Socialism has increased from 1989. The filmography assembled during the Filmikonen project has 320 entries for the 1970s and 705 for the 1980s, then 1368 for the 1990s and 2234 for the 2000s. In reaction to this increase, publications such as Keilbach (2008), Steinle (2007), Haggith (2005), Ebbrecht (2011) and others critically analyzed the use of archive footage.

- 5

Matthias Steinle, “Das Archivbild und seine ‘Geburt’ als Wahrnehmungsphänomen in den 1950er Jahren,” in Mediale Ordnungen, Erzählen, Archivieren, Beschreiben, ed. Corinna Müller and Irina Scheidgen, Schriftenreihe der Gesellschaft für Medienwissenschaft (GfM) 15 (Marburg: Schüren, 2007), 281, https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14294.

- 6

Tobi Haggith and Joanna Newman, eds., Holocaust and the Moving Image (Colombia: Wallflower, 2005), 33.

- 7

“One comes across the sequence of the deportation train almost daily,” Thomas Elsaesser, The Ethics of Appropriation: Found Footage between Archive and Internet, Keynote Recycled Cinema Symposium (DOKU.ARTS, 2014), 8.

- 8

Jamie Baron, The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History New York: Routledge, 2014) and Jamie Baron, Reuse, Misuse, Abuse (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2020).

- 9

Gerd Sebald, “Selektivität,” in Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftliche Gedächtnisforschung, ed. M. Berek et al. (Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2020), 1-19, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-26593-9_9-1.

- 10

The only exception of non-official footage is the private films of Eva Braun, which circulated from 1946 onward, mostly in newsreels. See also Steinle, “Das Archivbild,” 276.

- 11

See Lindeperg, Nuremberg, la bataille des images, 348. The delayed production, which was reconstructed in detail by Lindeperg, is reminiscent of the production history of Sidney Bernstein's GERMAN CONCENTRATION CAMP FACTUAL SURVEY (GB 1945/2014).

- 12

This urge for realism led him to extreme and questionable designs such as the illustration of a sequence about gas chambers disguised as showers using liberation footage of emaciated Holocaust survivors in real showers.

- 13

See Lindeperg, Nuremberg, la bataille des images, 347.

- 14

The name Wytwórnia Filmów Dokumentalnych i Fabularnych (WFDiF) or Studio for Documentary and Feature Films originally stood for a production company in Warsaw that initially produced newsreels and, from the 1960s, also feature films. Since 2019, the name has been used for a merger of various smaller state archives. The DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS material is now stored at the Filmoteka Narodowa. The uncut DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS material has been circulating, probably since the 1980s, as a VHS cassette with the WFDiF logo burnt into the picture.

- 15

The first and very short use of the material in DU UND MANCHER KAMERAD (GDR 1956) did not get much attention.

- 16

Alison Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory - The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

- 17

See: Schmidt, Fabian (2025). Der Westerborkfilm. Bilderwanderung und Holocausterinnerung. München: edition text + kritik, https://doi.org/10.5771/9783689300098, pp. 239.

- 18

For the concept of contested memory, see Joshua D. Zimmermann, Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and Its Aftermath (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2003).

- 19

An archive producer is responsible for searching, locating and negotiating the rights for the use of archive material. This job title has changed throughout the years but can be found already in the early uses in the 1950s.

- 20

The figures vary in the literature and are difficult to assess exactly, as Jews were not only transported via deportation trains, but also by means of lorries or as single passengers in trains, and the deportation lists from Westerbork sometimes do not match the corresponding ones in Auschwitz. The Herinneringscentrum names “almost 107,000” as the official number of deportees. Herinneringscentrum Kamp Westerbork, “Transporte,” accessed December 13, 2024, https://kampwesterbork.nl/de/geschichte/zweiter-weltkrieg/judendurchgangslager/67-zweiter-weltkrieg/durchgangslager/272-transporte.

- 21

NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 250i – 0854.

- 22

Breslauer asked a photography shop in Amsterdam that had no film equipment. In fact, he wrote his request only days after the replacement camera had been organized, most likely by Abraham Hammelburg, so it seems Breslauer was not too well informed about the ongoing filming.

- 23

For further theories and interpretations of the surviving documents see Florian Krautkrämer, ed., Aufschub. Das Lager Westerbork und der Film von Rudolf Breslauer / Harun Farocki (Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2018).

- 24

See Yad Vashem, “Transport from Westerbork, Camp, The Netherlands to Bergen Belsen, Camp, Germany on 19/05/1944,” accessed December 13, 2024, https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/deportations/5092550.

- 25

The minutes of this meeting are available at Yad Vashem archives, Eichmann-trial, TR.3, document 1352.

- 26

“Of all the points made here, I have a direct recollection only of the [...] diamond cleavers, there I know that at that time there was quite a [...] movement was going on” (Eichmann’s comment in the minutes), Eichmann Trial, Session 83, 30.6.1961 (documented for example by the Nizkor project).

- 27

Koert Broersma and Gerard Rossing, Kamp Westerbork gefilmd (Hooghalen/Assen: Van Gorcum & Comp. B.V., 1997), 97. The original source of this information remains unknown to the author.

- 28

National Archives of the Netherlands, Doc 2.06.076.09, inv. 82.

- 29

See Karel Margry, “‘Theresienstadt’ (1944-1945): The Nazi Propaganda Film Depicting the Concentration Camp as Paradise,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television, vol. 12, no. 2 (1992): 145-162; Natascha Drubek, “The Three Screenings of a Secret Documentary,” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe,no. 2-3 (April 2016), https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2016.0002-3.73; Eva Strusková, “The ‘Second Life’ of the Theresienstadt Films after the Second World War,” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe,no. 2-3 (May 2016), https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2016.0002.28.

- 30

See Judith Keilbach, Geschichtsbilder und Zeitzeugen. Zur Darstellung des Nationalsozialismus im bundesdeutschen Fernsehen (Münster: Lit Verlag Münster, 2008).

- 31

The films were examined for the use of 50 source materials, such as TRIUMPH DES WILLENS, the Warsaw ghetto film, Theresienstadt film and the like.

- 32

NUIT ET BROUILLARD (24 shots) and EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK (13 shots) have eight shots in common. NUIT ET BROUILLARD and ALS WÄR'S EIN STÜCK VON DIR! share 15 shots, but with 40 shots altogether, ALS WÄR'S EIN STÜCK VON DIR! still has its very own choice of Westerbork scenes.

- 33

Among other films, this montage can be found in HEIL HITLER! - CONFESSIONS OF A HITLER YOUTH (Arthur Holch, US 1991), HAMBURG IM KRIEG: 1939-1945 (Angelika Rätzke, DE 1995) and FACE AUX FANTOMES (Jean-Louis Comolli, FR 2003).

- 34

Landesarchiv NRW, Ger Rep 328 and 388 No. 0153.

- 35

See Stefan Joller, “Das Gedächtnis der Redaktion,” in Organisation und Gedächtnis, ed. Nian Leonhard, Oliver Dimbath, Hanna Haag, Gerd Sebald (Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2016), 131-157.

- 36

For a detailed reconstruction of this event, see Fabian Schmidt, “The Westerbork Film Revisited: Provenance, the Re-Use of Archive Material and Holocaust Remembrances,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 40, no. 4 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2020.1730033.

- 37

Astrid Erll, “Remembering across Time, Space, and Cultures: Premediation, Remediation and the ‘Indian Mutiny’,” in Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural Memory, ed. Astrid Erll and Ann Rigney (Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 2009), 114,

- 38

Willi Lindwer, Kamp van Hoop en Wanhoop (Amstelveen: Uitgeverij Balans, 1990), 49.

- 39

In the Dutch publication of Jacob Presser's book about Dutch Jewry, Ondergang (1965), Breslauer is given only a subordinate role. The filming is partially attributed to him, Jordan, and Todtmann, but Presser is vague and asserts that Breslauer 'sometimes worked on the film material.' See Presser, Jacob. Ondergang. De vervolging en verdelging van het Nederlandse Jodendom 1940–1945. Staatsdrukkerij/Martinus Nijhoff, Den Haag 1965, p. 290. Other historians either do not mention Breslauer at all (e.g., Lou de Jong) or refer to the dubious statements of the camp commandant Gemmeker during his trial in 1948. For a more detailed discussion see Schmidt (2025), pp.191.

- 40

Koert Broersma and Gerard Rossing, Kamp Westerbork gefilmd (Hooghalen/ Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum, 2021), 92

- 41

Sven Kramer, “Reiterative Reading: Harun Farocki’s Approach to the Footage from Westerbork Transit Camp,” New German Critique 123, vol. 41, issue 3 (2014/1): 35-55.

- 42

Broersma and Rossing, Kamp Westerbork gefilmd (2021), 78.

- 43

See Ulrike Koppermann, “Challenging the Perpetrators' Narrative: A Critical Reading of the Photo Album ‘Resettlement of the Jews from Hungary’,” Journal of Perpetrator Research 2.2 (2019): 101–129.

Bajohr, Frank and Dieter Pohl. Der Holocaust als offenes Geheimnis. Die Deutschen, die NS-Führung und die Alliierten. München: C.H.Beck, 2006.

Bajohr, Frank, and Dieter Pohl. Massenmord und schlechtes Gewissen. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer Taschenbuch Verlag, 2008.

Baron, Jamie. The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History. New York: Routledge, 2014.

Baron, Jamie. Reuse, Misuse, Abuse. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2020.

Boehm, Gottfried, ed. Was ist ein Bild? München: Fink, 2001.

Broersma, Koert, and Gerard Rossing. Kamp Westerbork gefilmd. Hooghalen/ Assen: Van Gorcum & Comp. B.V., 1997.

Broersma, Koert, and Gerard Rossing. Kamp Westerbork gefilmd. Hooghalen/ Assen: Koninklijke Van Gorcum, 2021.

Dörner, Bernward. Die Deutschen und der Holocaust. Was niemand wissen wollte, aber jeder wissen konnte. Berlin: Propyläen Verlag, 2007.

Drubek, Natascha. “The Three Screenings of a Secret Documentary.” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe 2-3 (April 2016). https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2016.0002-3.73.

Drubek, Natascha. Vernichtung und Befreiung. Die Rhetorik der Filmdokumente aus Majdanek 1944-1945. Wiesbaden: Springer SV, 2020.

Ebbrecht, Tobias. Geschichtsbilder im medialen Gedächtnis – Filmische Narrationen des Holocaust. Bielefeld: Transcript, 2011.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias, Noga Stiassny, and Lital Henig. “Digital Visual History: Historiographic Curation Using Digital Technologies.” Rethinking History 27, no. 2 (2023): 159-186, DOI: 10.1080/13642529.2023.2181534.

Elsaesser, Thomas. The Ethics of Appropriation: Found Footage between Archive and Internet. Keynote Recycled Cinema Symposium. DOKU.ARTS, 2014.

Erll, Astrid. “Remembering across Time, Space, and Cultures: Premediation, Remediation and the ‘Indian Mutiny’.” In Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural Memory, edited by Astrid Erll and Ann Rigney, Berlin, 109-138. New York: De Gruyter, 2009. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110217384.2.109.

Grünberg-Klein, Hannelore. Ich denke oft an den Krieg, denn früher hatte ich dazu keine Zeit. Köln: Kiepenhauer & Witsch, 2016.

Haggith, Tobi and Joanna Newman, eds. Holocaust and the Moving Image. Colombia: Wallflower, 2005.

Joller, Stefan. “Das Gedächtnis der Redaktion.” In Organisation und Gedächtnis, edited by Nian Leonhard, Oliver Dimbath, Hanna Haag, Gerd Sebald, 131-157. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2016.

Kaes, Anton. “History and Film: Public Memory in the Age of Electronic Dissemination.” History and Memory 2, no. 1 (Fall 1990).

Keilbach, Judith. Geschichtsbilder und Zeitzeugen. Zur Darstellung des Nationalsozialismus im bundesdeutschen Fernsehen. Münster: Lit Verlag Münster, 2008.

Koppermann, Ulrike. “Challenging the Perpetrators' Narrative: A Critical Reading of the Photo Album ‘Resettlement of the Jews from Hungary’.” Journal of Perpetrator Research 2, no. 2 (2019): 101–129.

Kramer, Sven. “Reiterative Reading: Harun Farocki’s Approach to the Footage from Westerbork Transit Camp.” New German Critique 123, vol. 41, no. 3 (2014/1): 35-55.

Krautkrämer, Florian, ed. Aufschub. Das Lager Westerbork und der Film von Rudolf Breslauer / Harun Farocki. Berlin: Vorwerk 8 2018.

Kulka, Otto Dov, and Eberhard Jäckel, eds. Die Juden in den geheimen NS-Stimmungsberichten 1933-1945. Düsseldorf, 2004/I.

Landsberg, Alison. Prosthetic Memory - The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Lindeperg, Sylvie. Nuremberg, la bataille des images. Paris: Payot, 2021.

Lindwer, Willi. Kamp van Hoop en Wanhoop. Amstelveen: Uitgeverij Balans, 1990.

Müller, Corinna, and Irina Scheidgen, eds. Mediale Ordnungen. Erzählen, Archivieren, Beschreiben. Schriftenreihe der Gesellschaft für Medienwissenschaft (GfM) 15. Marburg: Schüren, 2007. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14196.

Margry, Karel. “‘Theresienstadt’ (1944-1945): The Nazi Propaganda Film Depicting the Concentration Camp as Paradise.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 12, no. 2 (1992): 145-162.

Presser, Jacob. Ondergang. De vervolging en verdelging van het Nederlandse Jodendom 1940–1945. Staatsdrukkerij/Martinus Nijhoff, Den Haag, 1965.

Schmidt, Fabian. “The Westerbork Film Revisited: Provenance, the Re-Use of Archive Material and Holocaust Remembrances.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 40, no. 4 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2020.1730033.

Schmidt, Fabian, and Alexander Zöller. “Filmography of the Genocide: Official and Ephemeral Film Documents on the Persecution and Extermination of the European Jews 1933-1945.” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces 4 (2022): 1–160. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18245.

Schmidt, Fabian. Der Westerborkfilm. Bilderwanderung und Holocausterinnerung. München: edition text + kritik, 2025, https://doi.org/10.5771/9783689300098.

Sebald, Gerd. “Selektivität.” In Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftliche Gedächtnisforschung, edited by M. Berek et al., 1-19. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-26593-9_9-1.

Steinle, Matthias. “Das Archivbild und seine ‘Geburt’ als Wahrnehmungsphänomen in den 1950er Jahren.” In Mediale Ordnungen, Erzählen, Archivieren, Beschreiben, edited by Corinna Müller and Irina Scheidgen, 259-282. Schriftenreihe der Gesellschaft für Medienwissenschaft (GfM) 15. Marburg: Schüren, 2007. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14294.

Strusková, Eva. “The ‘Second Life’ of the Theresienstadt Films after the Second World War.” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures of Central and Eastern Europe 2-3 (May 2016), https://doi.org/10.17892/app.2016.0002.28.

Wagenaar, Aad. Settela. Marshwood, Dorset: Lamorna Publications, 2005.

Weckel, Ulrike. Beschämende Bilder. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner Verlag, 2012/I.