Contested Memory

Bromberg 1939

Table of Contents

From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards

TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935)

Contested Memory

DER EWIGE JUDE (1940)

From Home Movie to Historical Document

A Living Document

Archiving the Ghetto

The Westerbork Film

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Ben-Moshe, Yael, and Alexander Zöller. “Contested Memory: Bromberg 1939.” Research in Film and History 7 (2025): 1–49. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/24053.

“This is a study of selective cultural preservation”, wrote Lewis E. Coser in his introduction to Maurice Halbwachs’ book On Collective Memory.1 Coser pointed to the “cultural” aspect, because indeed Halbwachs dedicated most of his study to collective memory rather than just personal memory. Although collective memory cannot serve as a substitute for our personal memory, it takes precedence over it because the individual needs an external structure for their personal memory. Halbwachs saw the work of memory as a selective process of remembering and forgetting: a prerequisite to understanding the present, and a process stretching over generations. Societies, wrote Halbwachs, “choose from the past the period into which we wish to immerse ourselves. […] This is because the people whom we remember no longer exist or, having moved more or less away from us, represent only a dead society in our eyes – or at least a society so different from the one in which we presently live that most of its commandments are superannuated.”2

This article deals with the formation of memory in three countries – Poland, Israel, and Germany – regarding events that occurred in the Polish city of Bydgoszcz (German: Bromberg)3 during the first week of September 1939, immediately after the outbreak of World War II. It discusses film footage from Bydgoszcz that initially was screened in the German wartime newsreels: civilians are seen being arrested at gunpoint by German soldiers and led away to an uncertain fate. While these moving images were employed strictly for propaganda purposes, they appear connected to an actual historical event: the so-called Bloody Sunday (German: Bromberger Blutsonntag, Polish: Krwawa niedziela), which took place on September 3 to 4, 1939. An incident of reprisal killings and mass violence, it remains one of the most controversial episodes in German and Polish memory. In the chaotic interim of German troops occupying the city and the Polish defenders leaving Bydgoszcz, the incident was likely triggered by German insurgents. Members of the SD (Sicherheitsdienst, SS intelligence service) from Berlin as well as local Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans living on Polish territory) began shooting at retreating columns of Polish soldiers. While these skirmishes may have resulted in limited casualties, the Polish response was forceful, and often excessive. Volksdeutsche suspected of being responsible for the outbreak of violence were arrested, and many of them executed on the spot. A comparable escalation of violence, fueled by long-standing animosity between Germans and Poles, occurred in nearby villages and farmsteads. Altogether, approximately 400 Germans may have been killed, most of them outside the city boundaries, though grossly inflated figures were put into circulation almost immediately afterwards by the German propaganda apparatus.4 The Germans soon retaliated with disproportionate violence, at least part of which was premeditated, having been planned long before the outbreak of hostilities.

The events in Bydgoszcz should be seen in the wider context of Nazi persecution and extermination policy targeting Christian Poles and Polish Jews, commencing immediately from the outbreak of World War II. The events of the Bloody Sunday itself – atrocities demonstrably meted out by Poles against ethnic Germans – pale in comparison to the disproportionate and pre-planned violence that followed. The Blutsonntag’s usefulness for both Nazi propaganda and Nazi extermination policy was that of a catalyst and a means for justifying genocidal violence. The punitive and self-serving nature of the German response is evident from the newsreel’s commentary and was echoed in numerous Nazi publications.

Beyond these violent reprisals, the Bloody Sunday was exploited by Nazi Germany for propagandistic purposes and became one of the most visceral exculpations for German anti-Polish policy5 For decades in Germany, the term Bromberger Blutsonntag was used to refer primarily to the killings of Volksdeutsche rather than the German reprisals that resulted in far greater casualties.6 Conversely, in Poland, the equivalent expression Krwawa niedziela is strongly tied to the suffering of Poles during and after the Bloody Sunday events. The precise sequence of events, however, remains doubtful, compelling contemporary historians to remain cautious about what triggered the violence. While the ongoing, decades-old debate can be characterized as a Polish-German dispute, it tends to obscure a third, crucial perspective that must be taken into account: that of the Jewish community of Bydgoszcz, and the collective memory about the events in Israel up until today.

This article discusses German newsreel footage connected to the Bloody Sunday, its historical context and use, and employs a transnational approach to trace its interpretation and appropriation across different cultural and societal divides in German, Polish, and Israeli memories. A transnational perspective enables us to draw attention to the divergence of how ‘Bromberg’ is remembered and ingrained in disparate and sometimes incompatible ways in the memory cultures of all three nations. Drawing on the historical background and observations on collective as well as individual memory, we examine the appropriation of this film footage in various productions in the wartime and postwar era until today. All the countries concerned have a special relationship to the events, both in connection to Bydgoszcz itself as well as to violence, persecution, and genocide during the period of World War II in general. We argue that the memory relating to Bydgoszcz and the Bloody Sunday remains contested and has taken on specific modes of remembrance and forgetting in the countries affected.

Formation and Transformation of Contested Memory

In April 1988, commemorating 45 years since the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising and during the trial of John Demjanjuk, Israeli scholars were invited for the first time to a conference in Warsaw dealing with the struggles and sacrifices of Poles and Jews during the war. “But the discussions, both on the stage and in the corridors, showed that [...] Jews and Poles [...] still have difficulty talking to each other without opening old and new wounds.”7 Israel Guttman, a Holocaust survivor, objected to what he described as “disastrous” accounts written by Polish historians, who claimed that the Poles actively supported the Jews in the ghetto and in their resistance efforts.8 In the Jewish and Israeli memory Poland holds exceptional significance as the central territory where the Holocaust was largely implemented9 Adapting Pierre Nora’s concept of lieu de mémoire globally, “the sites-of-memory approach was used as a tool to reconstruct – and at the same time, wittingly or unwittingly: to actively construct – national memory.”10 The Polish perspective, in this frame of reference, seeks to focus on Nazi crimes targeting ethnic Poles, and the designation of the Polish people by the Nazis as an inferior race destined for slavery, if not annihilation. The casualties which resulted from Nazi extermination policy of both Jewish and non-Jewish Poles are staggering, yet memory formation in Israel and Poland continues to be very distinct, and often conflicting.

“What characterized the Polish experience as a whole was witnessing.”11 Every stage of the Holocaust was indeed in front of Polish eyes: the deportation from Germany to Poland, the rise of the ghetto walls, the smell of extermination. In fact, the most dominant memory the Poles have of the Jews is watching them die, postulates Steinlauf.12 This experience however did not become part of the collective Polish memory, as it conflicted with the victimization narrative. Instead, antisemitism in Poland after World War II continued. It manifested itself in pogroms such as in Kielce (1946) and later in the forced emigration during the 1960s, following the Six-Day War, compelling 15,000 Jews to leave Poland and to renounce their Polish citizenship, after having been blamed for being pro-Israel, anti-social and disloyal. During 45 years of communist rule all Jewish institutions were nationalized including the Holocaust.13 “The Holocaust became an object lesson in the horrors of the last stage of monopoly capitalism.”14 But the bigger problem was that witnessing the murder of the Jews on Polish soil made it difficult for the Poles to confront “that past as a narrative of their own exemplary martyrdom. The meaning of the Holocaust had thus become Polish victimization by the Holocaust.”15 Only recently, in 2022, a tradition established in 1983 by Menahem Begin, the Israeli Prime Minister from 1977 to 1983, of thousands of Israeli youths traveling to the Nazi death camps in Poland as a memory-cultural rite of passage, was undermined by the Polish government’s demands to include memorial sites unrelated to the Shoah in order to acknowledge the suffering of non-Jewish Poles during the war.16

Against this background, coming to terms with the events in Bydgoszcz had to consider different historiographical positions, incompatible remembrances, and disparate self-conceptions. This is particularly evident when comparing Polish and German historiographical positions established shortly after the war. While the Polish position focused on Polish victimhood, early postwar German studies rarely dealt with German crimes committed during the first weeks of the war against Poland, a long-standing imbalance which persisted for decades. German historiography generally gave limited attention to the first weeks of the war, and if it did, tended to focus on the Volksdeutsche rather than the Polish victims of Nazi policy in Poland. As Lehnstaedt (2020) observes: “[...] The lack of research into and commemoration of these first six weeks of the conflict in Germany is surprising. [...] It is significant that there are probably more German studies on the Bydgoszcz Bloody Sunday (Krzoska 2012) – the Polish killings of some 400 ethnic Germans! – than on the tens of thousands of murders committed by the Germans themselves. Most, but by no means all, of these works appeared in the 1950s-70s, and usually did not deal with crimes committed in Poland, or attempted to relativize them.”

Instead, and despite being influenced by Nazi propaganda tropes, the Blutsonntag narrative emerged as a dominant leitmotif for West-German historians. One such example was Jörg Hoensch’s Geschichte Polens, published in 1983.17 This reactionary version of events was still being advocated in 1987 by the conservative historian Ernst Nolte, who wrote: “The war against Poland began with a tendency towards genocide on the Polish side, namely the so-called ‘Bromberg Bloody Sunday’, the slaughter of several thousand citizens of German origin by furious Poles. It must seem doubtful whether the German minority would have survived if the war had lasted longer than three weeks.”18 It was the journalist and historian Günter Schubert who broke with the previous German tradition with his watershed book about the Bloody Sunday, drawing from previously overlooked sources and Polish research relating to ethnic German diversion, i.e. a coordinated attack on Polish troops passing through Bydgoszcz as the likely cause of the violence that followed. In his 1989 study he was unambiguous that the event was deliberately triggered by German insurgents, a position that is largely congruent with the current Polish viewpoint. Schubert also agreed with previous Polish assessments on the verifiable number of German victims: 280 dead in the city of Bydgoszcz itself and 379 in the surrounding area, for a total of close to 700 Volksdeutsche victims.19

In the memory of the affected nations, Bydgoszcz therefore has left disparate traces. Germany is still coming to terms with the long-lived Blutsonntag legend transported by Nazi propaganda, which for decades influenced conservative historiography, and competitive narratives established between Germans and Poles during the Cold War.20 Poland, on the other hand, is grappling with a difficult chapter in its history that runs counter to the nation’s firmly established self-perception. The Israeli position is more removed from this German-Polish acrimony. The events in Bydgoszcz are regarded less as a point of contention but have been merged into the memory of many Jewish communities in Poland who suffered a similar fate. Bydgoszcz at the time was home to a rather small and secular Jewish community. No Yizkor book appears to have been compiled during that time in Bydgoszcz, or by survivors after the war.21 But even though memory formation has been very disparate, these contested memories have interacted and continue to interact with each other. In our approach this reciprocal transnationality comes into play on several levels:

- in regard to the historical event itself, born out of Bydgoszcz’s mixed population of Poles, Germans, and Jews, communities which were pivotal for memory formation in the respective countries;

- in light of the appropriation of the footage for specific means to suit comparative (national) memories, discussed below;

- in view of the transcultural impact of cinema in today’s age of global media cultures (Landsberg 2018);

- in our own position as researchers from Israel and Germany, having different cultural and societal frames, being prompted to enter into a dialogue with the other memory cultures and mnemonics at hand, requiring an “attentiveness to the border-transcending dimensions of remembering and forgetting.”22

The Events in Bydgoszcz in 1939 and the Historical Context of the Footage from UFA-TONWOCHE 471

The Bydgoszcz footage follows in close temporal connection to the atrocities committed on September 3 to 4, 1939. Regardless of how the shooting in the city itself was triggered, the shock and fear of the Polish population, apprehensive of the imminent German invasion, led to a situation in which Polish residents acted as a ‘fifth column’ to defend their homes.23 Rumors circulated that German saboteurs had opened fire on Poles from the towers of the Protestant churches. This became the trigger for a hunt for Volksdeutsche, which continued in various waves until the following day.24 The Bloody Sunday has been characterized as an incident of reprisal killings, but the catalyst and the circumstances are contested, not least because of long-lasting propaganda narratives established shortly after the fact.25

Back in May 1939, the Reichssicherheitshauptamt, the security apparatus of the SS, had weighed its options to utilize Volksdeutsche communities and their connections to obtain data on all Jews living in Poland, as well as on other individuals deemed a threat, such as communists, socialists, and members of the Polish intelligentsia. The SD had considered the head of the Deutscher Volksverband in Polen to be in a suitable position for this task and requested that a card index of individuals was to be compiled.26 This was then used to create the Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen, an index of individuals to be arrested (and, in many cases, executed) that would be made available to the Einsatzgruppen killing squads operating in occupied Poland. The printed categories found in the Sonderfahndungsbuch make it obvious that the majority of individuals were not being wanted simply for arrest, but to be exterminated by Gestapo and Einsatzgruppen.27 These preparations, undertaken months before the outbreak of war, culminated in Operation Tannenberg: utilizing the active assistance of the German minority in Poland, more than 61,000 names of the Polish elite were compiled; within two months the Einsatzgruppen had killed approximately 20,000 individuals in hundreds of mass shootings. The Volksdeutscher Selbstschutz, a paramilitary organization, participated in these massacres, including the one in the so-called Valley of Death at Fordon, close to Bydgoszcz.28 Tannenberg was closely linked to another mass extermination effort, the so-called Intelligenzaktion in which members of the Polish intelligentsia were detained and many of them killed. This included teachers from Bydgoszcz who were murdered in the Valley of Death at Fordon.

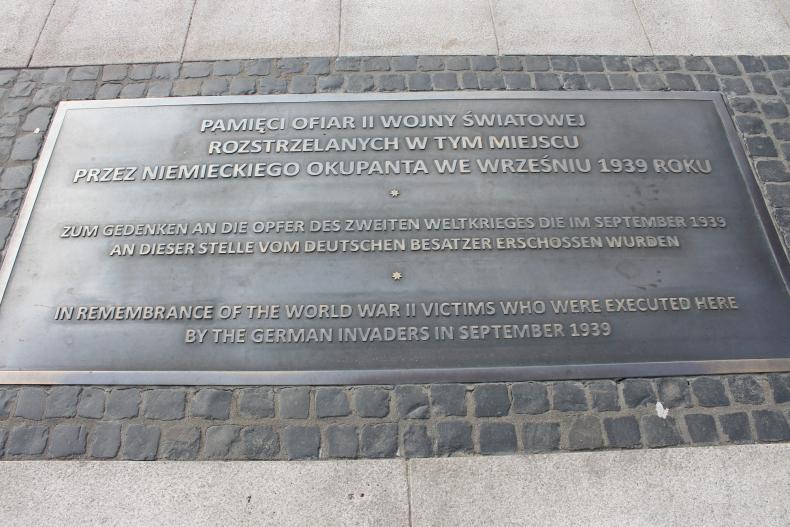

Bydgoszcz was occupied by German forces on September 5, 1939. Having established control over the city, the Germans began to look for Poles who had participated in the killings of Volksdeutsche.29 This intensified after the arrival of the Stadtkommandant, Walter Braemer, and the setting up of the German military administration. A decree signed by Braemer on September 8 announced that anyone caught shooting at German soldiers or civilians would be executed. Notably, Braemer’s decree did not refer to the Bloody Sunday itself but to skirmishes alleged to have taken place during the night of September 7 to 8.30 Despite this spurious reason, Poles killed on September 9 in Stary Rynek (Old Market) square encompassed entirely innocent civilians shot as hostages, including members of the local clergy, an oft-repeated practice by the German occupiers to instill terror and obedience.31 To drive home the terror aspect, the bodies of the executed were publicly displayed for six hours. All in all, the precise reasons for the arrests and executions, including those recorded on film and in photographs, remain uncertain: civilians were arrested as alleged perpetrators of Bloody Sunday atrocities, as hostages to be shot in reprisal executions, or as part of the aforementioned, premeditated killing operations. Polish historiography tends to regard the execution of twenty-five prominent citizens of Bydgoszcz in Stary Rynek square on September 9 as part of the Intelligenzaktion, rather than as an act of reprisal for the Bloody Sunday skirmishes. Altogether more than 5,000 Poles, including Jews, in and around Bydgoszcz were murdered in the first four months of German occupation; many non-Jewish Poles were also deported to concentration camps.32

One of the questions raised from the footage is the identity of the detainees gathered by Wehrmacht soldiers in Parkowa street. According to testimonies of Jews living in Bydgoszcz at the time, the displacement of Jews to other Polish cities (i.e. Warsaw and Łódź) began already before September 1 as a result of the persecution of Jews in Poland before the war.33 Those who managed to escape returned to Bydgoszcz to collect their belongings in November 1939. But those who stayed were killed by mid-October 1939.34

The persecution of mainly Polish resistance and elite at that time manifested itself in the guidelines of SS-Oberführer Herrmann issued on September 9 for dealing with the areas occupied by German troops in Pomerania: “…Show no leniency. Do not allow any gatherings. Dissolve Polish associations. [….] Take away all radio equipment from the Poles. When clearing cities and other areas, do not forget the Jews.”35

At that time around 2,500 to 3,500 Jews lived in Bydgoszcz.36 Most of them came from Germany and thus were modern reform Jews who spoke German and not Yiddish at home. They even had modern versions of the traditional clothing for the synagogue. Notwithstanding conditions for Jews living in Bydgoszcz were very restrictive, and Jews couldn’t go to any public school in the city but had to attend private institutions. When the Germans arrived, the Poles voluntarily informed German soldiers and the Gestapo where Jews were to be found.37 In the last week of August 1939, Jews were recruited by the Polish army like everyone else.38 Thus, it would be reasonable that in the hostility between Germans and Poles, Jews were captured or killed as well. That means that, without any distinct visual signs, among the captives in the footage could also be Jews that fought for Poland.

Markus Eugelblardt from the Bydgoszcz Jewish Committee testified in the 1960’s and by that supports our assumption that during the execution in Stary Rynek square, Poles and Jews were murdered together.39 It thus makes sense that most inmates in the footage from Bydgoszcz were Poles, and among them were a few Jews as well. Nonetheless, although a small community, the systematic murder of the Jews in Bydgoszcz did not happen at the beginning of the occupation but took place later and continued until November 1939. Leon Szczygliński pointed in his testimony to the fact that the persecution of Jews and Poles took place between September 12 and early October 1939, with the description of the fate of his 400 Jewish co-inmates from bloc No. 8 in Bydgoszcz who were murdered in early October (301/6000).40

German Wartime Newsreels and the Footage from Bydgoszcz

The outbreak of World War II on September 1, 1939, saw the first large-scale deployment of frontline cameramen as part of the German military, and the immediate utilization of their film footage in the Nazi newsreels.

The first German newsreels released on September 7, 1939, contained a number of shots which continue to circulate widely until today, often appropriated to illustrate the German attack on Poland: the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein shelling the Westerplatte peninsula near Danzig/Gdańsk, itself the first major battle of the German invasion of Poland; columns of Wehrmacht trucks and motorcycles moving along Polish roads in images reinforcing the Blitzkrieg formula; German soldiers removing the double-headed Polish eagle from a border crossing near Danzig/Gdańsk.41 The second round of wartime newsreels, released to German cinemas on September 14, 1939, again contained moving images which arguably have taken on iconic status by being appropriated time and again in various forms and contexts, impacting our collective visual memory of World War II: German soldiers are seen arresting Polish civilians in the town of Bydgoszcz, a major city in northern Poland with a sizeable German minority. Civilians are shown being gathered at gunpoint, some of them with their hands raised above their heads. Individuals are then led away to an uncertain fate, with the voice-over insinuating that some measure of swift punishment is to be meted out in response to the so-called Bromberger Blutsonntag on September 3 to 4, 1939. By that time, in mid-September and beyond, the term had become firmly entrenched in the German consciousness, having been invoked repeatedly by the Nazi mass-media, especially on the radio and in the press. Historically, the term ‘Blutsonntag’ had been applied a number of times to sudden outbursts of violence against unarmed groups of individuals and so drew on established narratives of past atrocities, not unlike connotations associated with the word ‘pogrom’. As such, it was fraught with implications of terror and injustice targeting unarmed civilians. But the term ‘Blutsonntag’ as applied to the events in Bydgoszcz may not have been originated by German anti-Polish propaganda, although it became the cornerstone of it and a key accusation-in-a-mirror narrative for German efforts to justify not only the war at hand, but the subsequent genocidal policies implemented in Poland. Rather, it appears to have been appropriated and exploited. The Jewish community in Bydgoszcz, which had suffered casualties from the very beginning of the event, had itself used the term as early as September 3.42 On September 8, Deutsche Rundschau, the newspaper of the German ethnic minority in Bydgoszcz, prominently used the term, after which it was propagated widely in Germany’s mass media.43

Moving images from wartime Bydgoszcz were first released in the German newsreels after Thursday, September 14, 1939, the day they were cleared by the film censors.44 Owing to the state-imposed coordination between the newsreel companies, supervised by the Deutsche Wochenschauzentrale at the Propaganda Ministry, we may assume that the Bydgoszcz footage was included in all four of the remaining weekly newsreel series, which hardly differed in their content except for title sequences: UFA-TONWOCHE, DEULIG-TONWOCHE, FOX TÖNENDE WOCHENSCHAU, and EMELKA-WOCHENSCHAU.45 All four companies were eventually merged into the DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU in the summer of 1940, which would go on to remain the single, unified weekly newsreel screened inside Germany until the end of the war.46 Owing to a lack of prints to supply all cinemas in Germany at once, the current newsreel was typically screened at first in major German cities, then handed down to second-tier cinemas, until it reached venues in smaller towns and villages. At the beginning of World War II, a single newsreel would thus remain in circulation for up to eight weeks, if not longer. 47 We therefore conclude that the initial screening of the Bydgoszcz footage took place during the period of mid-September until approximately mid-November 1939, long after the event had unfolded. In fact, while cinemagoers in the largest German cities were shown the footage within less than two weeks of having been recorded, individuals in remote villages may only have seen it after the war in Poland had already ended.48

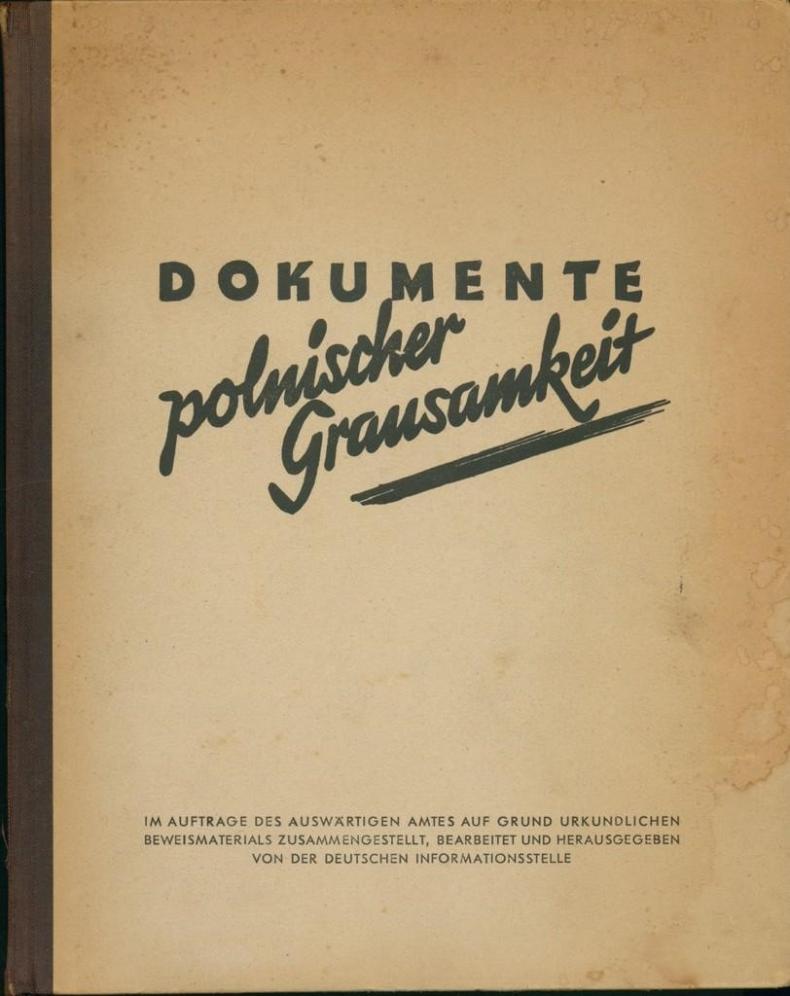

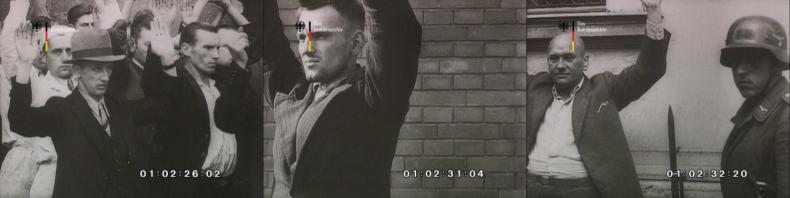

UFA-TONWOCHE 471 (206 m, b/w, sound) consists of ten segments, almost all of which deal with the war in Poland: 01. Hermann Göring speaking in front of workers of the Rheinmetall Borsig works in Berlin-Tegel; 02. The German advance on Polish territory – alleged perpetrators of the Bromberger Blutsonntag being arrested – Jews being led away and paraded in front of the camera; 03. Polish prisoners of war; 04. The ‘Black Madonna’ of Czestochowa, unaffected by the hostilities; 05. German troops advancing; 06. Images of the Luftwaffe; 07. Adolf Hitler touring the frontlines; 08. Polish prisoners of war being interviewed by German reporters, including on-scene audio; 09. Distribution of food to returning Volksdeutsche refugees; 10. German troops entering a Polish city, being greeted by jubilant Volksdeutsche.49

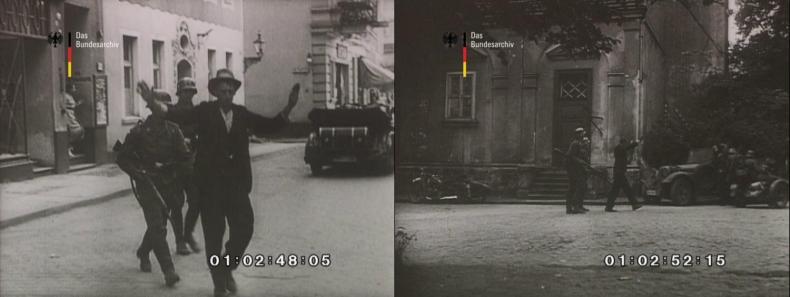

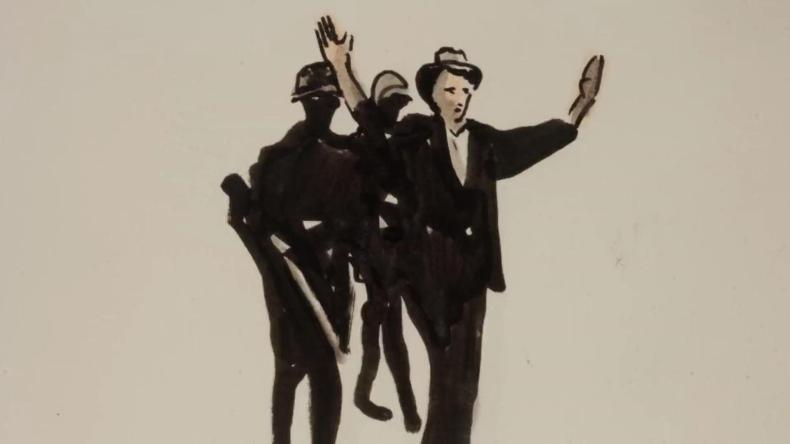

The footage from Bydgoszcz, which constitutes the first half of the second segment of UTW 471, starts at the 2:25 minute mark, and runs for approximately thirty seconds. It consists of eight shots. Male civilians are rounded up in the streets at gunpoint, many of them with their hands raised above their heads. German Luftwaffe (air force) soldiers are visible in some of the shots. One civilian, with rifles trained at him, is seen being led away. The corresponding voice-over starts shortly before the images, setting the scene:

One of the first measures is the cleansing of towns of the hate-filled Polish mob, incited by the Polish government to join in insidious partisan warfare against German soldiers. [Bydgoszcz footage starts.] Here all the murderers who participated in brutish bloodshed against defenseless German citizens during the infamous Blutnacht of Bromberg are dragged from their hiding spots.50

From the newsreel’s commentary we are to assume that the detained civilians were encouraged by the Polish government to engage in partisan warfare, and that they were implicated in atrocities against the Volksdeutsche. The voice-over concludes with the statement that the culprits will be subjected to “standrechtliche Bestrafung”, an overt reference to capital punishment under the Wehrmacht’s war-time martial law, which often meant summary execution by shooting. Owing to a lack of surviving documentation, the identity of the cameraman or cameramen remains uncertain. The presence of Luftwaffe soldiers may indicate that the footage was shot by a Propagandakompanie (PK) camera team, i.e. military war correspondents of the Wehrmacht. The Luftwaffe fielded its own units, called Kriegsberichterkompanien (Lw.KBK). Five PK, two KBK of the Luftwaffe, and one PK of the Kriegsmarine (German navy) were deployed during the war in Poland.51 Further uncertainty exists in that early during the war, civilian cameramen of UFA-TONWOCHE as well as a special detachment of cameramen under Leni Riefenstahl also shot footage in Poland.52

Almost as an afterthought, additional footage on Bydgoszcz was published in the subsequent newsreel, UFA-TONWOCHE 472, released on September 20, 1939.53 Volksdeutsche are shown identifying Poles in a prisoner-of-war holding pen in the vicinity of Bydgoszcz; the voice-over claims that the men identified were complicit in the Blutsonntag atrocities. 54

Atrocities alleged to have been perpetrated against Volksdeutsche in Poland were extensively photographed and published in the German press, in an attempt to justify the invasion as a means of ‘liberating’ the Volksdeutsche.55 The events in and around Bydgoszcz received particular attention.56 But in contrast to the German newspapers and the illustrated press, coverage of the Blutsonntag in film was very limited: no footage comparable to the atrocity photographs of slain Volksdeutsche that were distributed to the press were shown to cinema audiences.57 The Bydgoszcz footage in UTW 471 constitutes the first audio-visual manifestation of the ongoing propaganda campaign. This connection, however, is largely diegetic, as it is established by the newsreel voice-over and not substantiated in any way: there is no way of knowing whether the civilians rounded up in front of the camera were indeed involved in any transgressions. The voice-over demonstrates that the newsreel’s producers knew that audiences were acutely aware of the preceding atrocities, whether real or alleged, and that this narrational association would be effective in justifying to German audiences the on-screen event: civilians being arrested for unseen, unadjudicated crimes, and likely executed afterwards. This is true for both the arrests shown in UTW 471 and the ‘singling-out’ of alleged perpetrators in a prisoner-of-war holding pen near Bydgoszcz in UTW 472. Nevertheless, the treatment of the event in the newsreels appears more restrained. Until much later during the war, Germany’s newsreel propaganda eschewed atrocity footage, even when it could have served the intended purpose, to keep the medium accessible to as wide an audience as possible, including adolescents. Such inhibitions did not exist for the German illustrated press or German Auslandspropaganda (propaganda disseminated abroad).

Following the screening of the 35 mm newsreels, the footage from Bydgoszcz was published as narrow-gauge derivatives, such as the DEGETO-SCHMALFILMSCHRANK and OZAPHAN-MONATSSCHAU series produced for home cinema consumers.58 In 1940, shots were also edited into two compilation films about the war in Poland. The feature-length propaganda film DER FELDZUG IN POLEN (Fritz Hippler, DE 1940) uses the Bydgoszcz footage, though edited differently from the newsreel, and only in one of the two versions of the film that were cleared by the German film censors.59 FEUERTAUFE (Hans Bertram, DE 1940), another film compiled largely from Propagandakompanie (PK) and newsreel footage, extolled the Luftwaffe’s involvement in the attack on Poland and contains hitherto unpublished footage of wartime Bydgoszcz, though it is not connected to the Bloody Sunday events: the Bydgoszcz airfield being occupied by German troops and being repaired to put it back in use; an aerial shot showing the Bydgoszcz railway station; destroyed bridges in the city; Volksdeutsche crossing the river Brda (German: Brahe) on ferry boats “in order to return to their liberated home.”60

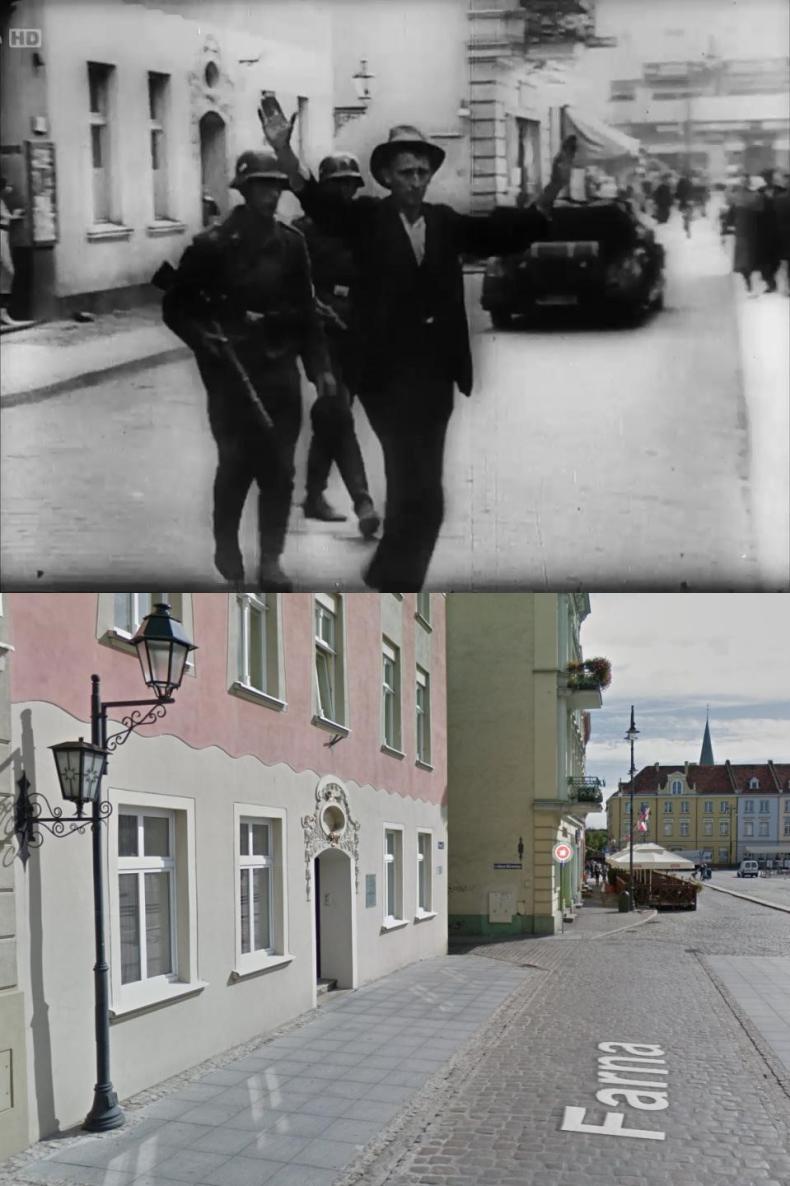

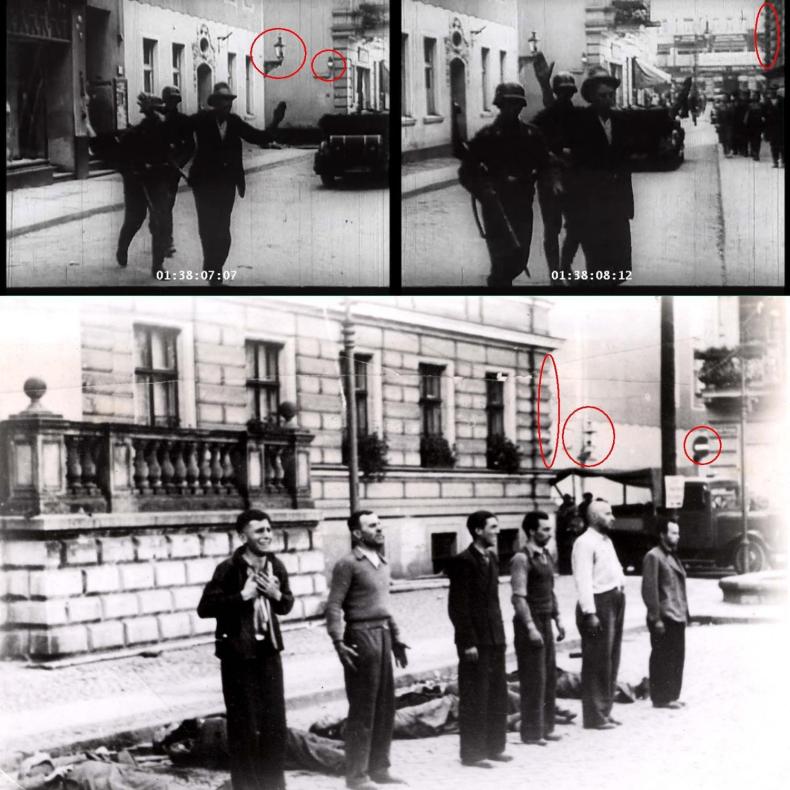

Some of the shots in UTW 471 can be geolocated to street locations in present-day Bydgoszcz. Shots 4 to 6 were taken in Parkowa street, just off Gdańska, one of the main thoroughfares in the city center; shot 7 was taken in Farna, an alleyway leading out onto Stary Rynek square. Exploring both streets on a map of Bydgoszcz shows that these sites are approximately half a kilometer apart from each other, separated by the river Brda (Brahe). The footage recorded does not represent a single occurrence, but arrests carried out in different parts of Bydgoszcz.61

The Farna shot is significant in that its location can be matched to a multitude of photographs taken just around the corner of the building visible on the right during the camera pan. These photos, taken in Stary Rynek square, show civilians being gathered, lined up, and summarily executed.62 However, uncertainty exists whether the footage and execution photos show precisely the same event. The newsreel footage has been tentatively dated to September 5, 8, or 9, 1939, with the executions in Stary Rynek square having taken place on September 9.63

Bydgoszcz and Anti-Semitic Propaganda in UFA-TONWOCHE 471

The footage from Bydgoszcz in UTW 471, running to approximately thirty seconds, is immediately followed by another thirty seconds showing Jews marching along a dusty road and being transported on trucks. Members of an SD Einsatzgruppe unit can be seen accompanying the transport. A final sequence of shots consists of elderly Jews being paraded in front of the camera. The voice-over strongly insinuates that the events in Bydgoszcz – the Blutsonntag, and in fact the war itself – were the result of Jewish subversion, a long-established anti-Semitic stereotype.

Scrutiny of the footage and corresponding PK photographs quickly demonstrates that this segment was constructed from unrelated material: the roughly thirty seconds following the Bydgoszcz sequence, while logically presented as a single ‘story’, were shot some 250 kilometers south of Bydgoszcz and likely had no connection to Bydgoszcz other than what the newsreel’s editors attempted to insinuate. A series of photographs taken by PK photographer Lifta on a single roll of photographic film shows a street crossing with a road sign giving distances to the villages of Ustronie and Opatów as 7.5 and 9.4 kilometers, respectively. Triangulation yields that the photographs may have been taken in or near the village of Wieruszów in Łódź Voivodeship. The town of Wieruszów is located approximately 30 kilometers from the former German-Polish border, and Wehrmacht units operated in the area almost immediately after the outbreak of war on September 1, 1939. This likely means that at least part of the anti-Semitic ‘story’ in UTW 471 was shot even before the footage from Bydgoszcz was recorded.64

As detailed above, there is no indication that the footage from Bydgoszcz and the following anti-Semitic segment in the newsreel were factually connected in any way. With only a small, secular Jewish community in Bydgoszcz at the time, it simply may not have been possible to establish the desired visual connection between the outbreak of the war, the Blutsonntag violence, and ‘the Jews’, compelling the editors to splice together entirely unrelated material – a technique routinely employed in the German newsreels throughout the entirety of the war. From the viewpoint of German propaganda, Orthodox Jews by far were the strongest ‘marker’ to visually signify and convey anti-Semitic tropes. The newsreel ‘story’ thus served a carefully calculated purpose: blaming the violence of the Bloody Sunday on the Poles whilst blaming the entire war on the Jews. The footage was employed by the Nazis several times for this purpose, including in the shorter version of FELDZUG IN POLEN (DE 1940), with the material edited differently for much the same effect. But despite this strong entanglement in Nazi propaganda tropes, the Bydgoszcz footage almost immediately was appropriated by filmmakers to convey entirely different messages. This was made possible by stripping it of its original context.

Appropriations of the Bydgoszcz Film Footage

Over time, the meaning of the footage has changed dramatically. For the Nazis it was evidence of the maltreatment of the Volksdeutsche minority in Poland: visceral justification for swift reprisal and anti-Polish policies. Yet in the postwar era, the images almost universally have been interpreted as prototypical evidence of Nazi brutality – a drastic reassessment overturning the meaning originally intended.65 This ‘new’ reading was established even while the war was ongoing. In the United Kingdom, the Polish-British filmmakers Franciszka and Stefan Themerson created CALLING MR SMITH (GB/PL 1943), a ten-minute propaganda short which laid bare the Nazi atrocities in Poland, calling on Britons to assist the beleaguered Polish people. The Themersons used a single, heavily edited shot from the Bydgoszcz footage, though its message to decry German crimes is unmistakable.

This usage foreshadows similar appropriations in the postwar era. KROK OD PRZEPASCI (ONE STEP FROM THE EDGE, Maciej Sienski, PL 1985), a film that discusses the extermination of various ethnic groups in Poland by the Nazis, again manifests this filmic expression. While using a wide array of well-known footage, Bydgoszcz is singled out as a symbol for these various groups of victims, blurring the perpetrator’s faces in the footage and giving prominence to the faces of the victims, thereby separating victims from perpetrators in a physically illustrative way.

The moving images from Bydgoszcz, albeit short, are emblematic for a frequent tactic employed by the German occupiers to terrorize the populations of Polish cities and towns: civilians were arrested at random in the streets, the arrestees often being held without a warrant, incarcerated, or executed; the event itself was so commonplace that the Poles coined the word łapanka for it (from łapać: to catch, to capture; ‘roundup’, ‘street abduction’).66 The on-screen events – detaining civilians at gunpoint – hint at a deliberate breaking-down of the accepted wartime rules of engagement and the application of calculated terror as a means of subduing an occupied nation. It is this imbalance of power – armed soldiers versus unarmed civilians – that contributes strongly to the lasting relevance of the footage: it is emblematic not of the actual events in Bydgoszcz, but of a rupture in civilization. Neither the alleged crime nor the punishment is shown on screen, which invites not only interpretation but also decontextualization of the scene. This allows the footage to be inserted into very different contexts in the wider scope of World War II, and applied to entirely different groups of victims, a remarkable characteristic which arguably contributes to its ‘iconic’ status until today. It has contributed to a history of appropriation that, by and large, makes illustrative use of Bydgoszcz rather than addressing its historical context. As a logical step towards extermination – arrests and brutalization of civilians, followed by ghettoization, followed by deportation – Bydgoszcz is sometimes combined with other well-known film materials to illustrate the stages of persecution of the European Jews.

Our project thus far has identified some 180 carrier films – documentaries, documentary series and features – between 1939 and 2024 that appropriate the Bydgoszcz footage. The following is based on a sampling of 70 carrier films, with a non-exclusive focus on German, Polish, and Israeli productions.

Illustrative use of the Bydgoszcz footage is widespread, combined with other iconic footage in associative montage, to detail the process and steps of persecution. Drawing on data gathered in our project to date, Bydgoszcz is found in connection with the following film materials and their topical significance: the Warsaw Documentary and Feature Film Studios (WFDiF) deportation compilation (DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS); the German Warsaw Ghetto film from 1942 (ghettoization); newsreel footage shot in Riga in July 1941 and edited into DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 567 (civilians attacked in the street); Reinhard Wiener’s amateur film of an execution of Jews by firing squad in Liepāja, Latvia (mass shootings); TÄTIGKEIT DER POLIZEI IM GENERALGOUVERNEMENT (an archival compilation, ca. 1942, on police operations in the occupied territories, possibly filmed by a police unit or the PK); footage from the town of Jonava edited into DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 566 (indiscriminate arrests of Jews); and anti-Jewish pogrom footage from Lviv. A combination of Bydgoszcz with these other film materials is common.

The most commonly combined footage in our body of carrier films is the compilation DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS, likely because it visually connects the arrests of civilians with the logical next step if the detainees are identified as Jews: deportation to the camps. It may be argued that Bydgoszcz is routinely misappropriated, or at least used in purely illustrative fashion. Carrier films typically employ their own narrative under which the iconic materials are subsumed. The source material is given a new, more abstract meaning: the universally condemned act of brutalizing civilians in wartime. While filmmakers may not be aware of the identity of the perpetrators or the victims we see in the footage, they may feel invited to appropriate Bydgoszcz as symbolic footage for the gradual process of persecution and annihilation under Nazi rule. We may thus conclude that a significant property of the Bydgoszcz footage is its malleability and the ease with which it may be inserted into other contexts that are often unconnected to the material’s actual historical background. For example, in the international co-production BERLIN CALLING (Nigel Dick, FR/DE/US/CZ 2015) the footage is used to illustrate the “life of all Jews in Germany [that] became ever more precarious".

In other German productions, such as FRITZ BAUER - TOD AUF RATEN (Ilona Ziok, DE 2010), STRAFSACHE 4 KS 2/63 - AUSCHWITZ VOR DEM FRANKFURTER SCHWURGERICHT S01E01: DIE ERMITTLUNG (Dietrich Wagner / Rolf Bickel, DE 2019), and the TV series DER ZWEITE WELTKRIEG, S01E01: DER ÜBERFALL (Michael Kloft, DE 2018), Bydgoszcz is not mentioned. The footage is instead combined with newsreel footage of the German occupation of Riga in the summer of 1941, thereby establishing the context of being about the persecution of the Jews. The voice-over in DER ZWEITE WELTKRIEG talks about mass shootings of Jews early during the war and the establishment of ghettos in Poland:

In den ersten Wochen des Krieges waren schon mehrere 1000 Juden von den Einsatzgruppen ermordet worden. Nun entstehen in vielen polnischen Städten Ghettos, in denen Menschen jüdischen Glaubens zusammengepfercht und [Bydgoszcz footage begins] ausgebeutet werden. Für viele [Bydgoszcz ends/Riga begins] werden diese Ghettos die erste Station ihres Leidensweges sein, der Millionen Menschen in den Tod führen wird [Riga ends].67

The Riga footage from DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 567 has a similar characteristic and thus similar effect; people are being dragged in the streets to an unknown fate, while the cause or the consequences are not made clear in the footage. Therefore, the scenes from Bydgoszcz and Riga serve the same thematic purpose in the carrier films, building tension without having to explain cause or consequences of the actual events depicted on screen.

In a similar manner, the episode GENOCIDE: 1941-1945 of the British TV series THE WORLD AT WAR (Michael Darlow, GB 1974) combines Bydgoszcz with the street violence in Riga, and with pogrom photographs from Lviv. This is augmented with testimony from a Polish Jew about the German occupation of Poland: “In Poland Nazis could do what they liked, and some Poles joined it. […].” But while the footage from Bydgoszcz is shown, the narrator speaks about the persecution of the Polish elite: “The smallest hint of opposition or non-cooperation meant reprisal against the whole community.”

While using the footage, German filmmakers in particular avoided discussing the massacre in the city directly, and so marginalized the dispute. The footage was used for illustrative purposes, for persecutions, deportation, ghettoization, and indiscriminate arrests in Poland and around Europe. Other uses relate to Poland in general, or to other parts of eastern Europe under German occupation. Only a handful of films discuss the footage in its original context, among those two recent German film productions. One is the ZDF production DER ZWEITE WELTKRIEG - DAS SOLLTEN SIE WISSEN (Alexander Berkel, DE 2019, S20E25 of the series HISTORY) and the other is the film production FÜHRER UND VERFÜHRER (Joachim Lang, DE 2024). The first covers quite broadly World War II not only in Europe, but including also the atomic bomb in Japan and its consequences, so it addresses the destruction of civilization in general, and not the Holocaust specifically.

The second film FÜHRER UND VERFÜHRER, not only mentions Bydgoszcz, but discusses the event of Bloody Sunday and the disinformation that was spread during the war and after. Goebbels: “Raise the number of victims by a factor of ten, and repeat it over and over again. […] invent slogan, ‘Bromberg’s Bloody Sunday’, that sounds good.” The footage from Bydgoszcz with original voice-over follows. Unique about Lang’s film is first of all the merging of the genres of Holocaust films and World War II films. Lang combines historical footage with testimonies, fiction and reality, and while incorporating the historical footage in the correct context, still manages to do so in a reflective manner.

In most Polish productions though, TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (DE 1935), DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS, and scenes of the invasion of Poland from UFA-TONWOCHE 470/1939 are routinely used in connection to the Bydgoszcz footage. These materials establish the infrastructure for the narrative: the rise of national socialism as in TDW – the perfect opposition for the Nazi narrative of chaos vs. order, the invasion of Poland (UTW 470), Bydgoszcz as a symbol of the persecutions, and DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS as the beginning of the end, or, as it is explained in POLOWANIE NA HITLERA (THE HUNT FOR HITLER, PL 2021) as a voice-over to the deportation compilation, “The disorder caused by the occupation will lead to deep trauma of society and will last for decades after the end of the war.”

Polish filmmakers, it could be argued, may be more aware of the actual context of the Bydgoszcz footage. Polish productions, such as the TV series POLOWANIE NA HITLER, utilize not just the Bydgoszcz footage from UTW 471 but also photographs of the executions in Stary Rynek square. But other domestic and Polish-international co-productions again discuss unrelated locations, such as AUSCHWITZ (James Moll, US/PL 2015), where the subject of the film is the city of Oświęcim and the concentration camp of Auschwitz, though Bydgoszcz is used to illustrate crimes committed against civilians in Poland more generally. Bydgoszcz is used in SURVIVING SKOKIE (Eli Adler / Blair Gershkow, US/PL 2015), a film concerned with wartime childhood in Pabianice, even though Pabianice is located some 250 kilometers from Bydgoszcz. As in historiography, we may find that the German, Polish, and Jewish perspectives on Bydgoszcz have started to converge in filmmaking, or at least allow each other to be taken into account.

But are these images attributed to the persecution of Jews as well? The term ‘Holocaust’ is not mentioned and does not exist in the frame of events in Poland, since it solely refers to the elimination of Jews. Rather, the genocide of the Jews is integrated in the context of Polish genocide: 3 million Jewish Poles and 3 million Christian Poles were murdered in Poland. That has been the continuous core narrative in Poland since the end of World War II until today. Such an approach could explain why the footage showing Orthodox Jews from Ustronie and Opatów is missing in all Polish films and is not part of the story about the persecution of the Poles (see, for example, the co-production THE BORDERLINE: HRUBIESZÓW OPERATION, PL/GB 2019).

Polish filmmakers used the footage as historical evidence of the events in Bydgoszcz or as illustrative example of persecutions in Poland, while marginalizing the other elements, the Holocaust of the Jews, as part of which Orthodox Jews from Opatów were rounded up. Nonetheless, in Polish-international co-productions the narrative is not always reflected in such a manner. These naturally seem to pander to a different (international) audience. As in the coproduction AUSCHWITZ (US/PL 2015), the victims clearly comprise different groups “inmates now include Polish political prisoners, gypsies ([shot of Settela Steinbach from the Westerbork film] and Jews”.

Unlike productions from other countries, only a handful of Israeli films from different decades may be cited as having used the footage, yet none of them mentions Bydgoszcz. In each case, the films connect the footage to other locations or to the persecution of the Jews at the outbreak of the war: in AHAVA ZOT LO HAYTA (LOVE IT WAS NOT, Maya Sarfaty, IL/AT 2020), Bydgoszcz is used to illustrate Czechoslovakia; in ADOLF EICHMANN – THE SECRET MEMOIRS (IL 2002, Nissim Mossek/ Alan Rosenthal) it is connected to the city of Kraków. In the influential documentary HA-MAKAH HASHMONIM V’ECHAT (THE 81ST BLOW, David Bergman/ Jacques Ehrlich/ Haim Gouri, IL 1974) the footage was appropriated without sound or interpretation and was edited into a sequence discussing the general persecution and murder of European Jews. Our research so far did not uncover an Israeli production that discusses the footage in its actual historical context, which correlates with the limited space allocated to Bydgoszcz in the Israeli collective memory.

Summary

The lasting significance of the events in Bydgoszcz for German, Polish, and Israeli memory emerged from the city’s heterogeneous population. The end of the Cold War, globalization, and European unification have challenged domestic memory perspectives. Increasingly, German researchers (Schubert, Arani, Lehnstaedt) have reacted to memory formation in Poland, undermining the long-lived Nazi narrative. In keeping with Astrid Erll’s (2011) assessments, we may observe that the lasting impacts of the events in Bydgoszcz transcend both geographical and cultural borders and boundaries. No longer “competitive narratives”, they have been transformed into comparative memories that “put historical experiences into perspective.”.68 They persist and influence not only national remembrances but affect – and often hinder to this day – the unencumbered interaction between different memory cultures.

In Germany, the collective memory, if not historiography, remains distorted by propaganda narratives established before 1945. Indeed, outside academia, parrotings of the Bydgoszcz myth are still being published and achieve to reach considerable audiences.69 In Poland, attempts to broaden the dialogue and harmonize historiographical positions continue to clash with the national, heroic perspective. It is all the more remarkable, then, that the Polish Institute for National Remembrance (IPN) has recently adopted a position on the Bloody Sunday events which seeks to harmonize its stance with the findings of Schubert (1989), demonstrating a willingness to further the dialogue between Polish and German historians, even if it means tapping into research that is decades old. 70 In the permanent exhibition at POLIN, the Museum of the History of Polish Jews in Warsaw, the Bloody Sunday is not addressed directly. The permanent exhibition commences with the outbreak of war but gives almost no space to the war experience itself, moving almost immediately to the time after the surrender of Poland, when German occupation had solidified. In the Museum of World War Two in Gdańsk, the Bloody Sunday is the subject of a small and rather inconspicuous niche in the permanent exhibition where a six-minute video on the subject is looped. The main room of this section features a large-scale, cropped version of the photograph shown in Figure 6, but without connecting it to the Bloody Sunday. Instead, it is dated to September 10, 1939 and placed in the context of an Einsatzgruppe killing. Unlike the defense of Warsaw in the autumn of 1939 or the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, the events in Bydgoszcz can hardly be dressed up to conform to the prevalent self-image of Poland as a nation victimized yet withstanding the Nazi onslaught through heroic resistance. In Warsaw, very much unlike in Bydgoszcz, this heroic interpretation of the past is everywhere. But from a Polish perspective, the events in Bydgoszcz constituted not only terror but betrayal and humiliation, meted out by individuals who often had been close acquaintances of the victims: “More than one hundred thousand men started terrorizing and murdering their Polish neighbors – people whom they knew very well.”71 Aleksander Scibor-Rylski’s drama SASIEDZI (PL 1969) broaches this issue of betrayal among neighbors and strongly illustrates how these feelings have been formative for the (non-)remembrance of Bydgoszcz in the collective Polish memory.72 At the same time, the absence of Jewish voices in what is essentially a Polish-German debate remains jarring. As Astrid Erll observes, “in the transcultural travels of memory, elements may get lost, become repressed, silenced, and censored, and remain unfulfilled.”73 Even though a decontextualized use appears to have become the conventional mode of appropriation, more recent examples point to a critical use of the footage, a shift reflected both in historiography as well as filmmaking. At the same time, questions of memory, remembrance, and forgetting likely will continue to be contested, and hopefully discussed in light of its entangled transnational relevance as well as its actual historical context.

- 1

Lewis A. Coser, “Introduction,” in Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory, ed. Lewis A. Coser (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1992), 31.

- 2

Ibid., 50.

- 3

Throughout this text, we will use the names Bydgoszcz and Bromberg interchangeably, though we strive to use the German and Polish names in connection to the respective historical discourses.

- 4

Marcus Krzoska, “Der ‘Bromberger Blutsonntag’ 1939: Kontroversen und Forschungsergebnisse,” Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 60, no. 2 (2012): 239. In October 1939, Kurt Lück, the head of the Gräberzentrale, an entity set up in Posen to count the Volksdeutsche victims, announced that more than 5,000 ethnic Germans had been killed, among them 1,000 in Bydgoszcz alone: ibid., 242.

- 5

We reviewed the third edition, which increased the casualty figures originally given for the Volksdeutsche victims by a factor of ten. See Günter Schubert, Das Unternehmen "Bromberger Blutsonntag". Tod einer Legende (Köln: Bund-Verlag, 1989): 27 and 200–201. On the inflation of Volksdeutsche victim figures, see also Krzoska, “Der ‘Bromberger Blutsonntag’ 1939,” 240.

- 6

A notable exception is Stephan Lehnstaedt, “‘Polenfeldzug’: Nazi Crimes during the War against Poland in 1939 and their Place in German Memory”, Studia Nad Totalitaryzmem i Wiekiem XX / Totalitarian and 20th Century Studies 4, no. 4: 446–455. In a deliberate reversal of the established meaning, Lehnstaedt equates the term ‘Blutsonntag’ with the German reprisals that resulted in the killing of approximately 3,000 Poles; the term is no longer applied to the Volksdeutsche victims.

- 7

Charles Gans, “Ha’polanim lo nakfu etzbah la’azor la’gov’im baraav” (“Poles didn’t do anything to help starving people in the ghetto”), Maariv, April 22, 1988, 3 Beit.

- 8

Ibid.

- 9

Joshua D. Zimmermann, “Introduction. Changing Perceptions in the Historiography of Polish-Jewish Relations During the Second World War,” in Contested Memories. Poles and Jews during the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, ed. Joshua D. Zimmerman (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2003), 1–2.

- 10

Astrid Erll, “Travelling Memory,” Parallax 17, no. 4 (2011): 6–7, DOI: 10.1080/13534645.2011.605570.

- 11

Michael C. Steinlauf, “Teaching about the Holocaust in Poland,” in Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and its Aftermath, ed. Joshua D. Zimmerman (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2003), 263.

- 12

Ibid, 263–264.

- 13

Stanislaw Krajewski, “The Impact of the Shoah on the Thinking of Contemporary Polish Jewry: A Personal Account,” in Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and its Aftermath, ed. Joshua D. Zimmerman (New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2003), 294.

- 14

Steinlauf, 264.

- 15

Steinlauf, 265.

- 16

N.N., “Israel nixes youth trips to Poland over Holocaust education spat,” Times of Israel, June 16, 2022, https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-nixes-youth-trips-to-poland-over-holocaust-education-spat/.

- 17

Jörg Hoensch, Geschichte Polens (Stuttgart: Ulmer, 1983). See also Klaus Bachmann, “Ein Massaker, das es nie gab,” taz, 8 September 1989, https://taz.de/Ein-Massaker-das-es-nie-gab/!1799214/. Hoensch revised his position for a more nuanced assessment, which is reflected in subsequent editions of the book.

- 18

Quoted in Miriam Y. Arani, “Photojournalism as a means of deception in Nazi-occupied Poland, 1939–45,” in Visual Histories of Occupation: A Transcultural Dialogue, ed. Jeremy E. Taylor (2021), 176. For another example of the revisionist position carried over from the Nazi narrative, see Rudolf Trenkel, Der Bromberger Blutsonntag im September 1939 oder Die gezielte Provokation zu Beginn des Zweiten Weltkrieges (Hamburg: Thorner Freundeskreis, 1975). Trenkel projects the ‘provocation’ onto the Poles, thus shifting the blame, and omits any discussion of German insurgents who likely sparked the violence.

- 19

Schubert, Das Unternehmen "Bromberger Blutsonntag", 198–199.

- 20

Krzoska, Der Bromberger Blutsonntag 1939, 242–243 and Lehnstaedt, Polenfeldzug, 452.

- 21

Fordon and Bydgosczc appear in the Pinkas Hakehilot Encyclopaedia of Jewish Communities in Poland (1969–2007), https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/Pinkas_Poland/pinkas_poland6.html.

- 22

Astrid Erll, “Travelling Memory,” 15.

- 23

Krzoska, Der Bromberger Blutsonntag 1939, 239.

- 24

Ibid, 239–240. According to Polish sources, the overall number of German civilians killed in the first days of the war, together with German minorities in rural regions, was around 4,000 to 5,000 people. In Bydgoszcz and the surrounding area, the Volksdeutsche casualties reliably exceeded 400. Krzoska, Der Bromberger Blutsonntag 1939, 248.

- 25

Krzoska, Der Bromberger Blutsonntag 1939, 239.

- 26

BArch, R 58/954 (RSHA), memorandum re: connections to Poland, Geheime Reichssache, May 9, 1939.

- 27

Śląska Biblioteka Cyfrowa, Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen, https://www.sbc.org.pl/dlibra/publication/27260/edition/24330.

- 28

For a detailed study on the Selbstschutz’s involvement in the Fordon massacres see Wiesław Trzeciakowski, Selbstschutz w Bydgoszczy i powiecie bydgoskim 1939–1940 (Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Tekst, 2017).

- 29

Haaretz (September 6, 1939) cited a British radio announcement that Poles were evacuating Bydgoszcz.

- 30

Drozdowski, Nie tylko krwawa niedziela, 111–112.

- 31

Trzeciakowski, Selbstschutz, 84.

- 32

Lehnstaedt, Polenfeldzug, 449.

- 33

See testimonies of Marila (Chajmowitz) Hecht, 2001, Yad Vashem, Collections, File Number 12278, Item ID 4025345, https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/documents/4025345, and Shoshana Veis, 1996, Yad Vashem, File Number 10498, Item ID 3565043, https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/documents/3565043; Haboker, “Ne’esar Shaliach Polani? Od Dam Bagvolot,” (25 August 1939, Number 1159): 9, on skirmishes and border incidents prior to the outbreak of the war.

- 34

See testimonies of Marila (Chajmowitz) Hecht, 2001, Shoshana Veis, 10498, and Kazir Kachmerc Gershon 2005, File Number 12587, in Yad Vashem archive: “In November I returned to Bydgoszcz with my mother and sister, and we took more things from home, cause we didn’t take much. The house was exactly as we left it. At that time there were no jews in the city, they were all dead.” (Marila (Chajmowitz) Hecht, 2001). “At some point at the end of the year we left for Lodz. My mom returned to Bydgoszcz and took some things from the apartment, although the Gestapo declared the apartment as confiscated.” (Kazir Kachmerc Gershon, 2005).

- 35

Drozdowski, Nie tylko krwawa niedziela.

- 36

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/bydgoszcz; Pinkas Hakehilot claims 3500, https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/pinkas_poland/pol0_00001.html#B.

- 37

Marila (Chajmowitz) Hecht, 2001, Yad Vashem, Collections, File Number 12278, Item ID 4025345, https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/documents/4025345.

- 38

Kazir Kachmerc Gershon 1989, Yad Vashem archive, 7401, Item ID 3561736, Collections, https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/documents/3561736.

- 39

Yad Vashem, Testimonies Collection, File Number 559, Record Group: M.49.E/559, Eugelblardt, Markus, Evidence of mass murder of Jews and Poles in Bydgoszcz.

- 40

Yad Vashem, Leon Szczyglinski, Testimony about his encountering in Dobrzyn and Bydgoszcz, Record Group 0.4, Documentation about Trials of War Criminals, File Number 255, p. 18-33 (appears also in Testimonies Collection, File Number 6002, Record Group M.49.E/6002).

- 41

BArch, Film ID 580, UFA-TONWOCHE 470, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/580/663723.

- 42

Doris L. Bergen, “Instrumentalization of Volksdeutsche in German Propaganda in 1939. Replacing/Erasing Poles, Jews, and Other Victims," German Studies Review 3 (2016): 460.

- 43

It seems imprecise, then, to claim the Deutsche Rundschau originated – instead of merely appropriated – the term ‘Bromberger Blutsonntag’. Several sources nevertheless have claimed that the Rundschau coined the term. Cf. Volker Rieß, “Bromberger Blutsonntag,” in Enzyklopädie des Nationalsozialismus, ed. Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Graml, Hermann Weiß (Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1998), 404.

- 44

Peter Bucher, Wochenschauen und Dokumentarfilme 1895–1950 im Bundesarchiv (Koblenz: Bundesarchiv, 1984), 87.

- 45

At present, this assumption relies on an incomplete set of the pertinent newsreels. The German Bundesarchiv (BArch) holds elements for UFA-TONWOCHE 471 but none for the other newsreel series released in 1939.

- 46

On the development of the German wartime newsreels, see Ulrike Bartels, Die Wochenschau im Dritten Reich. Entwicklung und Funktion eines Massenmediums unter besonderer Berücksichtigung völkisch-nationaler Inhalte (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2004).

- 47

Bartels, Die Wochenschau im Dritten Reich, 205–209.

- 48

The Polish-German armistice came into effect on October 6, 1939.

- 49

BArch, Film ID 584, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/584/663718.

- 50

BArch, Film ID 584, UFA-TONWOCHE 471, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/584/663718. German original voice-over: “Eine der ersten Aufgaben ist die Säuberung der Ortschaften von dem verhetzten polnischen Mob, der von der polnischen Regierung zum hinterhältigen Freischärlerkampf gegen die deutschen Soldaten aufgestachelt wurde. Hier werden alle die Mordgesellen aus ihren Schlupfwinkeln geholt, die sich an den viehischen Bluttaten gegen wehrlose deutsche Bürger in der berüchtigten Blutnacht von Bromberg beteiligt hatten. Sie werden sofort ihrer standrechtlichen Bestrafung entgegengeführt.”

- 51

Miriam Y. Arani, “Die Fotografien der Propagandakompanien der deutschen Wehrmacht als Quellen zu den Ereignissen im besetzten Polen 1939–1945,” Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 60, no. 1 (2011): 10.

- 52

Bill Niven, Hitler and Film: The Führer’s Hidden Passion (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2018), 143–144. The authors are indebted to Hans-Gunter Voigt, Potsdam, for further information on this subject.

- 53

Bucher, Wochenschauen, 87.

- 54

BArch, Film ID 6153, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/6153/667496.

- 55

Arani, Photojournalism as a means of deception, 161 and 167.

- 56

Arani, Fotografien der Propagandakompanien, 29.

- 57

For discussion of the atrocity photographs in the Nazi press, see Arani, Die Fotografien der Propagandakompanien, 10, and Arani, Photojournalism as a means of deception, 161.

- 58

Cf. OZAPHAN-MONATSSCHAU 10a/30, USHMM RG-60.4281, Film ID 2552, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1003746. The Bydgoszcz footage starts at 1:22. Intertitle: “Das Mordgesindel von Bromberg wird aus seinen Schlupfwinkeln geholt” (“The murderous rabble of Bromberg is being dragged from their hiding spots”).

- 59

BArch, Film ID 23066, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/23066/662781.

- 60

BArch, Film ID 17950, https://digitaler-lesesaal.bundesarchiv.de/video/17950/260375.

- 61

Main Commission for Investigation of War Crimes, Poland, Warsaw & Rosa Berman for Yad Vashem, https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/photos/86776; https://collections.yadvashem.org/en/photos/82835.

- 62

Yad Vashem Image Archives, images 1872/11, 1893/11, 1893/12, 3824/2, and 69GO4. The individuals killed are variously identified as prisoners or hostages executed in retaliation for the Bloody Sunday events. Prints of some of the photographs are also found in the image collections of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum (USHMM) in Washington, D.C., and at the Jewish Historical Institute (JHI) in Warsaw.

- 63

Drozdowski (2022) includes the footage in his chapter on September 9 in Bydgoszcz. Krzystof Drozdowski, Nie tylko krwawa niedziela: bydgoski wrzesień dzień po dniu (Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Pejzaż 2022), 123–145. This chapter incorporates stills from the UTW footage as well as various photographs, including photos of civilians gathered and then executed in Stary Rynek square, indicating temporal overlap.

- 64

Regarding the presence of German troops in Wieruszów and killings of Polish civilians by German soldiers during the first three days of the war in Poland (September 1-3, 1939), see BArch B 162/40893.

- 65

For another such recontextualization of one of the filmic ‘icons’ covered in this project, see Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Trophy, evidence, document: appropriating an archive film from Liepaja, 1941,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 36, no. 4 (2016): 509–528, 10.1080/01439685.2016.1157286.

- 66

Ron Jeffery, Red Runs the Vistula (Auckland: Nevron Associates, 1985).

- 67

English translation: “Several thousand Jews had already been killed by the Einsatzgruppen within the first weeks of the war. Now ghettos are being established in many Polish cities into which the Jews are being herded [Bydgoszcz footage starts] and exploited. For many [Bydgoszcz footage ends, Riga 1 footage starts] these ghettos will be the first stage of their ordeal, resulting in the death of millions [Riga 1 footage ends].”

- 68

Anja Tippner and Anna Artwińska, “Camp Narratives in a Comparative Transnational Perspective,” in Narratives of Annihilation, Confinement, and Survival. Camp Literature in a Transnational Perspective, ed. Anja Tippner and Anna Artwińska (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019), 3–4.

- 69

In 2022, Compact, the most popular magazine of Germany’s extreme far-right founded by Jürgen Elsaesser, a journalist and right-wing activist, published the special issue “Polens verschwiegene Schuld”, which repeated the Nazi narrative about the Bloody Sunday. Until early 2024, Compact was available in many railway bookshops across Germany, selling thousands of copies, before being dropped by a major press wholesaler. In 2024, it was temporarily banned by the German Federal Minister of the Interior but went into circulation again, pending an appeal to the ban.

- 70

IPN, “The Myth of ‘The Bloody Sunday of Bydgoszcz’ Dispelled,” https://1september39.com/39e/articles/2332,The-Myth-of-quotThe-Bloody-Sunday-of-Bydgoszcz-Dispelled.html. The website “1 September 39”, launched in 2020, is an IPN online resource. Schubert’s study was finally translated into Polish fourteen years after its original German publication: Günter Schubert, Bydgoska krwawa niedziela. Śmierć legendy (Bydgoszcz: Miejski Komitet Ochrony Pamięci Walk i Męczeństwa w Bydgoszczy, 2003).

- 71

Lehnstaedt, Polenfeldzug, 449.

- 72

Bergen, Instrumentalisation of Volksdeutsche, 448–449.

- 73

Erll, Travelling Memory, 14.

Arani, Miriam Y. “Photojournalism as a means of deception in Nazi-occupied Poland, 1939–45.” In Visual Histories of Occupation: A Transcultural Dialogue, edited by Jeremy E. Taylor, 159–182. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2021.

Arani, Miriam Y. “Die Fotografien der Propagandakompanien der deutschen Wehrmacht als Quellen zu den Ereignissen im besetzten Polen 1939-1945.” In Zeitschrift für Ostmitteleuropa-Forschung 60, no. 1 (2011): 1–49.

Bachmann, Klaus. “Ein Massaker, das es nie gab.” taz, September 8, 1989. https://taz.de/Ein-Massaker-das-es-nie-gab/!1799214/.

Bartels, Ulrike. Die Wochenschau im Dritten Reich. Entwicklung und Funktion eines Massenmediums unter besonderer Berücksichtigung völkisch-nationaler Inhalte. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2004.

Bergen, Doris L. “Instrumentalization of Volksdeutsche in German Propaganda in 1939. Replacing/Erasing Poles, Jews, and Other Victims.” German Studies Review 3 (2016): 447–470.

Bucher, Peter. Wochenschauen und Dokumentarfilme 1895–1950 im Bundesarchiv. Koblenz: Bundesarchiv, 1984.

Coser, Lewis A. “Introduction.” In Maurice Halbwachs. On Collective Memory, edited by Lewis A. Coser, 1–34. Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1992.

Drozdowski, Krzystof. Nie tylko krwawa niedziela: bydgoski wrzesień dzień po dniu. Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Pejzaż, 2022.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias. “Trophy, Evidence, Document: Appropriating an Archive Film from Liepaja, 1941.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 36, no. 4 (2016): 509–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2016.115728.

Erll, Astrid. “Travelling Memory.” Parallax 17, no. 4 (2011): 4–18. DOI: 10.1080/13534645.2011.605570.

Gans, Charles. “Ha’polanim lo nakfu etzbah la’azor la’gov’im baraav.” Maariv, April 22, 1988.

Hoensch, Jörg. Geschichte Polens. Stuttgart: Ulmer, 1983.

Instytut Pamięci Narodowej (IPN). “The Myth of ‘The Bloody Sunday of Bydgoszcz’ Dispelled.” Accessed December 20, 2024. https://1september39.com/39e/articles/2332,The-Myth-of-quotThe-Bloody-Sunday-of-Bydgoszcz-Dispelled.html.

Jeffery, Ron. Red Runs the Vistula. Auckland: Nevron Associates, 1985.

Jewish Virtual Library. “Bydgoszcz, Poland.” Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/bydgoszcz.

Krajewski, Stanislaw. “The Impact of the Shoah on the Thinking of Contemporary Polish Jewry: A Personal Account.” In Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and its Aftermath, edited by Joshua D. Zimmerman, 291–304. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2003.

Krzoska, Marcus. “Der ‘Bromberger Blutsonntag’ 1939: Kontroversen und Forschungsergebnisse.” Vierteljahrshefte für Zeitgeschichte 60, no. 2 (2012): 237–248.

Lehnstaedt, Stephan. “‘Polenfeldzug’: Nazi Crimes during the War against Poland in 1939 and their Place in German Memory.” Studia Nad Totalitaryzmem i Wiekiem XX / Totalitarian and 20th Century Studies 4, no. 4 (2020): 446–455.

N.N. “Ne’esar Shaliach Polani? Od Dam Bagvolot.” Haboker, August 25, 1939.

N.N. “Kravot Ba‘prozdor Hapolani.” Haaretz, September 6, 1939.

N.N. “Israel nixes youth trips to Poland over Holocaust education spat.” Times of Israel, June 16, 2022. https://www.timesofisrael.com/israel-nixes-youth-trips-to-poland-over-holocaust-education-spat.

Niven, Bill. Hitler and Film: The Führer’s Hidden Passion. New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 2018.

Pinkas Hakehilot Encyclopaedia of Jewish Communities in Poland. Volume VI. “Poznan and Pomerania districts; Gdansk.” Last modified April 26, 2021. https://www.jewishgen.org/Yizkor/Pinkas_Poland/pinkas_poland6.html.

Rieß, Volker. “Bromberger Blutsonntag.” In Enzyklopädie des Nationalsozialismus, edited by Wolfgang Benz, Hermann Graml, Hermann Weiß, 404–405. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta, 1998.

Schadewaldt, Hans. Die polnischen Greueltaten an den Volksdeutschen in Polen. Berlin: Volk und Reich-Verlag, 1940.

Schubert, Günter. Das Unternehmen "Bromberger Blutsonntag." Tod einer Legende. Köln: Bund-Verlag, 1989.

Schubert, Günter. Bydgoska krwawa niedziela. Śmierć legendy. Bydgoszcz: Miejski Komitet Ochrony Pamięci Walk i Męczeństwa w Bydgoszczy, 2003.

Śląska Biblioteka Cyfrowa. “Sonderfahndungsbuch Polen.” Accessed December 20, 2024. https://www.sbc.org.pl/dlibra/publication/27260/edition/24330.

Steinlauf, Michael C. “Teaching about the Holocaust in Poland.” In Contested Memories: Poles and Jews During the Holocaust and its Aftermath, edited by Joshua D. Zimmerman, 262–270. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2003.

Tippner, Anja, and Anna Artwińska. “Camp Narratives in a Comparative Transnational Perspective.” In Narratives of Annihilation, Confinement, and Survival. Camp Literature in a Transnational Perspective, edited by Anja Tippner and Anna Artwińska, 1–12. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2019.

Trenkel, Rudolf. Der Bromberger Blutsonntag im September 1939 oder Die gezielte Provokation zu Beginn des Zweiten Weltkrieges. Hamburg: Thorner Freundeskreis, 1975.

Trzeciakowski, Wiesław. Selbstschutz w Bydgoszczy i powiecie bydgoskim 1939–1940. Bydgoszcz: Wydawnictwo Tekst, 2017.

Zimmerman, Joshua D. “Introduction. Changing Perceptions in the Historiography of Polish-Jewish Relations during the Second World War.” In Contested Memories. Poles and Jews during the Holocaust and Its Aftermath, edited by Joshua D. Zimmerman, 1–16. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2003.