From Home Movie to Historical Document

Examining the Production and Initial Reception of Eva Braun’s Private Films

Table of Contents

From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards

TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935)

Contested Memory

DER EWIGE JUDE (1940)

From Home Movie to Historical Document

A Living Document

Archiving the Ghetto

The Westerbork Film

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Miljković, Aleksandra. “From Home Movie to Historical Document: Examining the Production and Initial Reception of Eva Braun’s Private Films.” Research in Film and History 7 (2025): 1–42. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/24046.

“An amateur shoots in color from a privileged location...” — from MYSTÈRES D’ARCHIVES: 1940: EVA BRAUN FILME HITLER (Serge Viallet, FR 2015)

1. Introduction

On November 8, 1946, the United States Forces European Theater (USFET) in Frankfurt on the Main sent a document to the Office of Military Government (U.S. Zone), Financial Branch.1 The document outlines the request to secure Shipment No. 76, which included assets belonging to Adolf Hitler and his lover, and later wife, Eva Braun. The correspondence also included a brief history of the so-called “Hitler-Eva Property.” In addition to a substantial quantity of silverware, jewelry, and foreign currency, the document notes several items of uncertain material value. Beside Adolf Hitler’s suit, two more chattels were mentioned: a chest with photo albums, along with the negatives of these photographs, and 28 reels of motion picture film.2 Shipment No. 76 reached its ultimate destination at the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) in Washington D.C., where it is housed to date.3

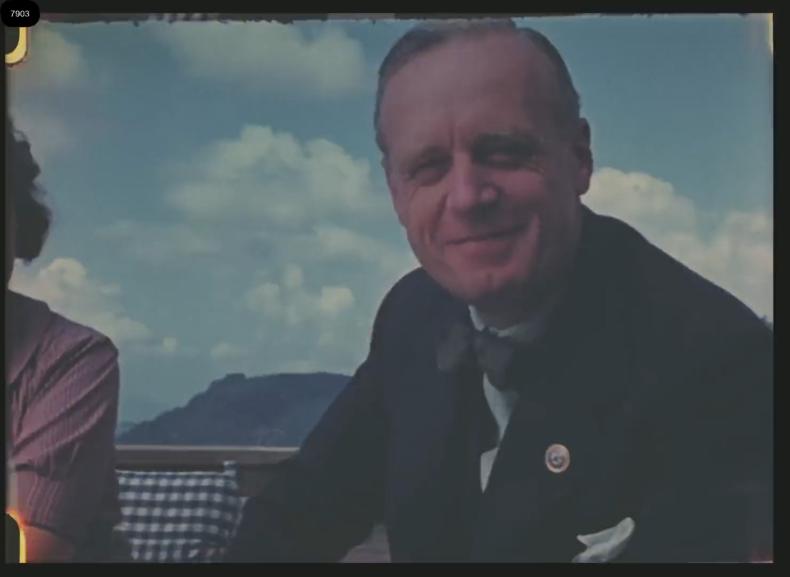

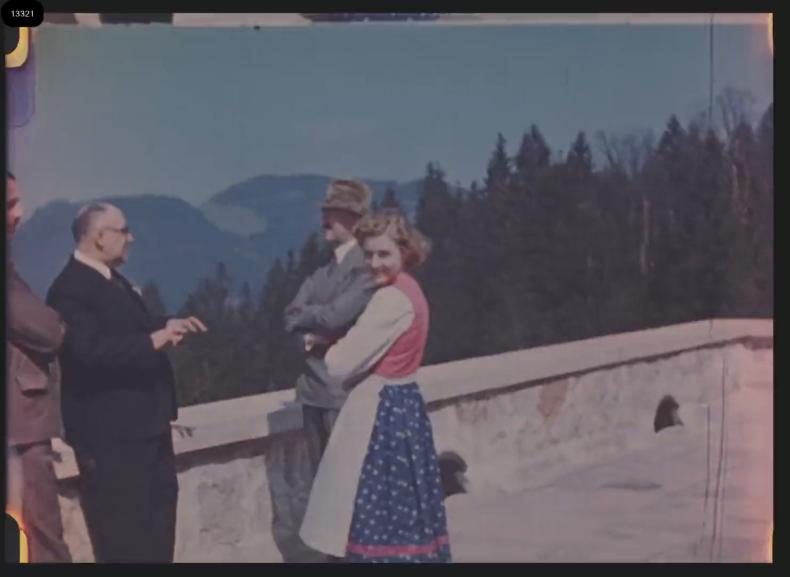

The films and photo albums, which vividly depict Eva Braun’s life in southern Germany, are classified at the NARA as “Private Motion Pictures of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun.” Nine reels of 16mm silent film are currently preserved. They were copied from the original 28 reels produced between 1938 and 1944, which capture themes that are typical of conventional home movies: joyful moments of Braun, her middle-class family and friends enjoying sports, walks in the countryside, family gatherings, celebrations, pets, children at play and journeys through Europe. Simultaneously, and quite “uncharacteristic of home movies and other amateur images,”4 the footage meticulously documents the lives of top Nazi officials at the Berghof, Hitler’s private residence in Obersalzberg. Next to Adolf Hitler, one can see his private secretary Martin Bormann, official photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, personal physician Theodor Morell, chief adjutant Wilhelm Brückner, and state architect Albert Speer. Regular visitors to the Berghof also included propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, foreign minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, and head of Hitler Youth Baldur von Schirach. The Berghof footage additionally provides a revealing behind-the-scenes look at certain historical moments and meetings of key figures. Notable examples include Hitler welcoming Italian Foreign Minister Galeazzo Ciano in October 1936, leading to a secret Treaty of Friendship between Italy and Germany. Another interesting moment is the footage of the leading SS men responsible for the “Final Solution”—Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich and Karl Wolff—examining some papers while having a casual conversation.

Eva Braun’s color home movies have become a valuable resource for numerous post-war film and television projects, provoking a mixture of dismay and curiosity among the public. Despite their widespread use, they have been surprisingly little researched or analyzed. Roger Odin, in his exploration of home movies as documents, suggests that even if these are often perceived as intimate glimpses into personal lives, they also serve as filters that obscure the underlying realities, in the case of Braun’s films, realities of historical trauma and atrocity.5 Next to Odin, Frances Guerin has written extensively about Braun’s footage, dedicating an entire chapter of her book to it. She explores a perspective similar to Odin’s, providing a comprehensive analysis of Eva Braun’s films and photo albums. Guerin emphasizes the flexibility of amateur images and their connection to bourgeois relationships. While Braun’s images surely evoke a sense of familiarity, according to Guerin they also disrupt comfort by making viewers aware of witnessing Hitler and his lover, fostering historical consciousness.6 The chapter concludes with a discussion of contemporary reception and repurposing of Braun’s images on the internet, particularly on platforms like YouTube, which, according to Guerin, is serving various (political) purposes.7

In this study, I will focus on Eva Braun’s home movies to address several key questions. First, I will conduct a provenance study to trace the origins and journey of these films, exploring how they were created, preserved, and eventually made accessible. Next, I will examine Braun’s role as a filmmaker, focusing on her privilege, the agency she exercised in crafting her films, and the personal identity she sought to convey through them. I will then analyze the iconography of national and gender identities that emerge in her work. Following this, I will assess whether Braun’s films were intended to shape perceptions of Hitler as a ‘common man,’ possibly serving a propagandistic role. Finally, I will investigate the post-war reception of Braun’s films, beginning with their integration into American newsreels in 1947 and concluding with their expanded use and ‘rediscovery’ in the early 1970s.

2. The Archival History of the Eva-Braun-Films

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) preserves a comprehensive collection of documents serving as evidence related to Shipment No. 76.8 According to these records, the Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) team secured the “Hitler-Eva Property” on August 1, 1945. Earlier that year, SS Oberführer Josef Spacil had commanded the transportation of these items from Berlin to the SS office and riding school in Schloss Fischhorn, Austria, where they were handed over to SS-Hauptsturmführer Franz Konrad and SS-Obersturmführer Erwin Haufler. Their task was to bury various caches of valuables in the Bavarian region. Nevertheless, the two men distributed these valuables among various close friends for safekeeping. The postwar interrogation of Franz Konrad led to the partial recovery of several items later included in Shipment No. 76, but it was also revealed that some of the property had already been destroyed.

The documents do not specify when the “Hitler-Eva property” was sent to the US. The inventory receipt for Shipment No. 76 is dated December 4, 1946.9 The day before, a release document had been issued, stating that the shipment would be sent to the War Department in Washington, sponsored for display by the National Archives, where the property was to be permanently preserved. Interestingly, the photographic albums and film materials were not listed in this US inventory, although these were part of the Konrad/Haufler collection of valuables. According to a document dated April 4, 1947, they were still kept in USFET’s Documents Control Section.10 Consequently, it remains unclear when did Braun’s films finally arrived at the National Archives. However, their earliest known reproductions can be found in the American newsreels UNIVERSAL NEWSREEL VOLUME 20, RELEASE 15 (US February 20, 1947), and PARAMOUNT NEWS 52 (US March-April 1947). This raises the possibility that either the footage may have been transferred to the National Archives as early as 1947, or alternatively, parts of it could have been copied and sent to the US earlier for the production of newsreels featuring the newly discovered material.

Likely with the aim of optimizing storage the initial collection of 28 smaller rolls was combined into only nine.11 However, this merging process resulted in issues such as flipped footage and disrupted sequences. Investigation established that the last record issued by the National Archives that hints to their possession of the original 16mm Eva Braun films is from June 1973.12 In 1972, Lutz Becker, a German-born artist and filmmaker based in the UK, undertook extensive research on Braun’s films, integrating them into the documentary SWASTIKA (GB 1973)—a project that may have played a pivotal role in bringing the footage to renewed attention.13 The footage’s technical flaws became evident during Becker’s research and were only fully corrected during the digital restoration of the material, which began in 2021, using archival duplicate negatives.14 In 1975, the German federally owned film licensing company Transit Film in Munich formally requested the repatriation of Eva Braun’s films from the US General Services Administration (GSA). The response they received asserted that “the Department of Justice recognizes no legal right in Transit Film to the Eva Braun films,” effectively denying the repatriation request.15 One year before that, the German Bundesarchiv, legally represented by Transit Film, acquired the copies of Braun’s films from NARA. Upon receiving the footage, the Bundesarchiv adhered to archival preservation protocols, organizing the material into ten reels and categorizing it into color and black-and-white footage. To identify individuals and locations featured in the films, the archive relied significantly on the cooperation of Albert Speer.16

Following Eva Braun’s death and the release of her films, interest in her person increased significantly. However, due to her absence to present and advocate for her footage, the material came to be considered legally unauthorized. As a result, the footage started to be appropriated into new contexts, where different authors utilized it. Within the extensive filmography of carrier films compiled by our project approximately 660 titles (out of roughly 4400 that have been examined) prominently feature Eva Braun’s films, ranking it among the top three most frequently appropriated Nazi film materials.17 This ranking places it alongside iconic works such as TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (DE 1935) and LIBERATION OF AUSCHWITZ (Soviet Army footage, 1945). The prominence of Eva Braun’s films stems from various factors. Firstly, they offer a comprehensive depiction of activities in Berchtesgaden and Hitler’s inner circle, including international visits. Secondly, the films provide rare color footage from the era of World War II. Finally, their license-free nature and extensive scope makes them versatile filler material allowing for wider and flexible use.

3. Eva Braun as an Amateur Filmmaker

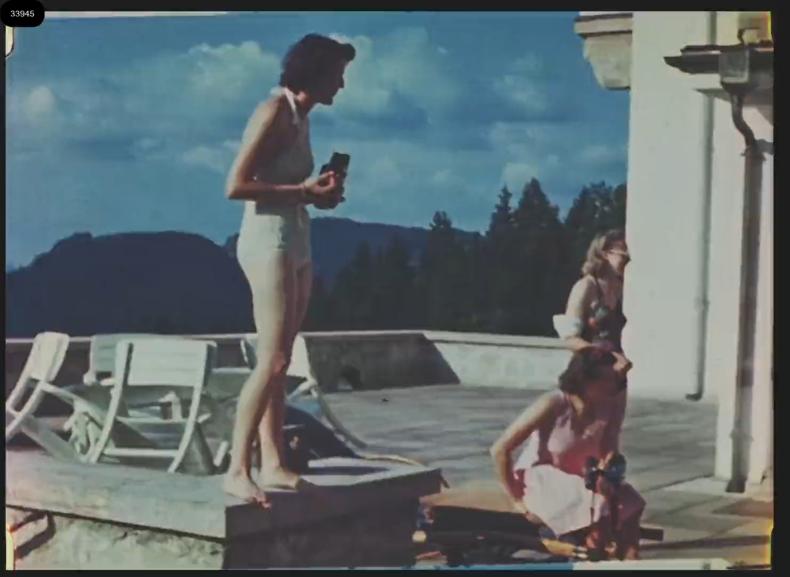

Amateur film and photography reshaped film history in the 1920s and 1930s by standardizing technology and expanding access to cameras, leading to a mass market. In 1930s Germany, amateur filmmaking expanded alongside the establishment of film clubs, periodicals, and state-funded competitions.18 Amateur films offer a different perspective from corporate filmmaking by actively engaging with private histories through their vernacular narratives. They embrace inclusivity, recognizing the importance of “history from below.”19 Therefore, it is inadequate to categorize amateur filmmaking as unintentional, leisure/emotional, and distinct from commercial media. Rather than assuming a textual innocence, amateur film should be assigned a political definition within social relations taking into consideration its connections to cinematic practices, ideologies and economic structures.20 Drawing on Foucault’s concept of discursive practices, Patricia Zimmermann argues that amateur film continually reshapes social relations and challenges presuppositions within discourses while establishing a compensatory relationship with professional film.21 Eva Braun’s films, like those of most amateur filmmakers in 1930s Germany, capture intimate moments, where the camera becomes a tool for self-expression and social interaction (Images 1 and 2). Due to her privileged status, Braun was a rare woman amateur filmmaker with unique access to color film stock and locations that were out of reach for most people. While amateur home cinema was becoming more popular, especially among the middle class, the number of women filmmakers remained relatively small, making her involvement even more exceptional.

3.1 Showcasing Privilege and Navigating Fluid Identity

The story of Eva Braun, intrinsically linked to the figure of Adolf Hitler, has been retold many times, often focusing on the tale of a young girl from Munich who falls in love with the much older Führer.22 Ostensibly, Braun’s existence remained hidden from the public before 1945, while in the years after the war she gained a notoriety that surpassed even some of the key figures of the Nazi regime.23 Before she became known as ‘Hitler’s mistress,’ Eva Braun showed an early passion for film and photography. Initially working for Hitler’s personal photographer, Heinrich Hoffmann, Braun’s enthusiasm in filmmaking was later encouraged by Hitler himself. In the Third Reich, the propaganda potential of the medium of film was widely acknowledged and Hitler himself demonstrated interest in filmmaking.24 Aligned with Hitler’s preferences, the Ministry of Propaganda occasionally provided exclusive and still uncensored German films for the Berghof audience circumventing censorship, including popular American and Western European productions.25 Indications suggest that Braun’s home movies were also occasionally viewed.26 This elevated Eva Braun beyond the role of a mere mistress, transforming her into a part of this new ‘family circle’ and giving her a privileged position rather than a passive, gendered figure.

The most famous of the films and photographs in Eva Braun’s collection are those portraying Hitler. It is likely that Braun sold her photos to Heinrich Hoffmann for propaganda purposes, which brings into question their purely private nature.27 The production of Braun’s films and photo albums indicates a serious commitment to her role as a camerawoman, carefully selecting occasions that showed Hitler as an amiable figure when near others. Besides shaping Hitler’s ‘private’ image, Braun meticulously organized her photo albums and home movies. Through textual explanations, she used these two mediums to document her personal view of historically significant events, infusing the depictions with a strongly subjective and occasionally critical note.28 Her pictures testify to a woman’s freedom and emancipation, atypical for the time, thus serving as a particular agenda. The idea that Braun may have been recording “her version of history”29 might suggest that her filmmaking was less fixated on Adolf Hitler and more focused on highlighting her position of privilege. After all, she crafted her identity beyond the restrictive Nazi policies of motherhood and childbearing imposed on women in Germany at the time.30 While she may not have been an overt instigator of political subversion, her actions nonetheless reveal a distinct agency, strategically leveraging her position of privilege. This subtle assertion of autonomy highlights her ability to navigate and, to some extent, exploit the very structures designed to confine her.

The analysis of authorship in Eva Braun’s home movies requires a nuanced dimension, intricately interwoven with her evolving identity and surroundings. The complexity of authorship unfolds in two relationships: the filming dynamics with her sister Margarete (Gretl) Braun and the more abstract connection with her short-term existence as Eva Hitler. Gretl Braun, akin to Eva, becomes a significant figure in the footage, transitioning between roles behind and in front of the camera. Both Braun sisters, eventually integrated into Hitler’s innermost private circles, were employed by Hoffmann.31 In a black and white sequence from Reel 1, presumably filmed in August 1939 and capturing the celebration of the 25th anniversary of Hitler’s enlistment in the army, a noteworthy dynamic between the Braun sisters is evident.32 The sequence unfolds with Eva Braun participating in the conversation with Hitler, Heinrich Hoffmann and other officials. The subsequent segment depicts Gretl Braun engaged in conversation with Hitler (Image 3), only to revert to the group with Hitler, Eva, and Hoffmann (Image 5). The significance of this transition becomes more apparent when examining a photo from Braun’s albums (Image 4). This photo, seemingly taken by a third person, captures the moment of ‘camera exchange,’ offering insight into this ostensibly collaborative sisterly effort.

Barbara Hahn insightfully observed that “authorship is not a neutral instance,”33 highlighting how women’s authorship is frequently disrupted by the discontinuity of their names. This leads to an important question: how does the perception and understanding of these films change when one realizes they are not just the works of Eva Braun but also of Eva Hitler? This recognition could prompt a reevaluation of Braun’s reputation and a possible shift in how her work is received under her more ‘infamous’ name. However, the claim that Eva Braun “did not make herself known in her lifetime but only in her death”34 is inconsistent on several fronts. There are no photographs of Eva Hitler; only images of Eva Braun have survived, providing insights beyond her association with the Führer. Eva Braun actively shaped her image, moving beyond recognition as Hitler’s mistress. She crafted an identity open to multiple interpretations.

3.2 Creating National and Gender Iconographies

During the Nazi era, artistic expressions, including Eva Braun’s films, were closely aligned with Third Reich policies that aimed to promote the ideal of Volksgemeinschaft—a concept representing a unified and idealized social, political, and moral order.35 Eva Braun’s filmmaking may have evolved from a personal hobby into a medium of self-affirmation and perhaps even self-deception, serving to create an ideal that obscures and excludes the potential violence and humiliation she herself experienced. Through her private camera, Hitler is idealized as a beloved figure, both father and lover, who shapes the imagined collective of the German Volksgemeinschaft. This development in her filmmaking may reflect her close alignment with Hitler’s vision, given her proximity to the Nazi inner circle.

In times of social upheaval and change, Braun deliberately sought to project a sense of stability, tradition, and rootedness in her films. Her work was more than a mere portrayal of everyday life, it was a calculated effort to assert and solidify one’s place within Hitler’s ‘family framework.’ Through her films, she aimed to instill a sense of belonging and purpose, anchoring individuals to a defined role in the social order of the time. Braun’s portrayal of herself and her surroundings can be seen as multifaceted and ambiguous. On the one hand, her frequent focus on nature and landscapes serves to underscore the image of her as a modest and domestic person. Her careful self-portrayal also contributed to the way she was perceived in the post-war period. Particularly in the post-war years, she was perceived as a kind of ‘innocent’ figure, not deeply entangled in Nazi ideology, and embodying traditional feminine and domestic values. This myth aligned with the idealized image that Nazi propaganda painted of the German woman: domestic, loyal, modest, and connected to the homeland (Image 6).

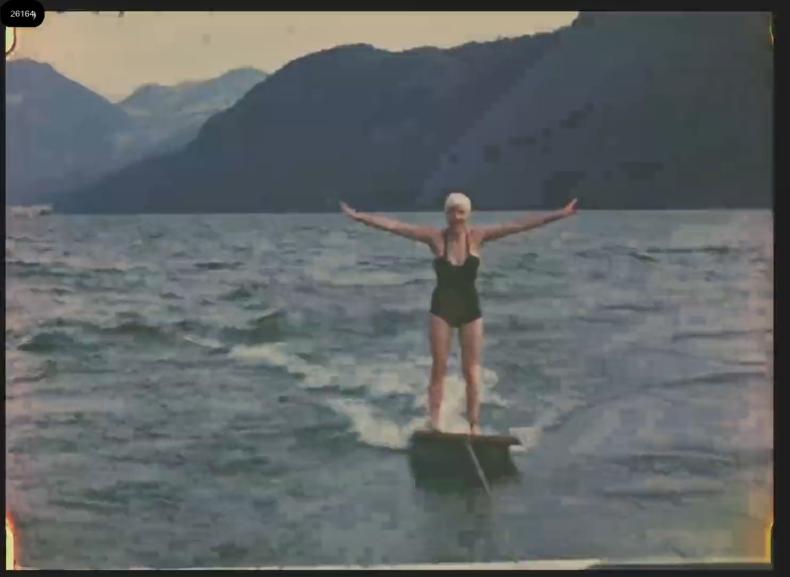

On the other hand, Eva Braun belonged to an elite circle, characterized by a privileged, liberal and relaxed lifestyle. She had no children and, unlike many other women in the Nazi establishment, she maintained a very close relationship with Hitler and other high-ranking officials. This connection granted her a degree of freedom and access that was unusual for women of her time. She often recorded herself and her friends in more relaxed and informal settings, capturing moments of celebration, flirtation, and leisure, such as sunbathing on the terraces of the Berghof or waterskiing on the lakes (Image 7). These scenes depict a carefree, almost hedonistic side of life that is in stark contrast with the more austere and traditional images she also produced.

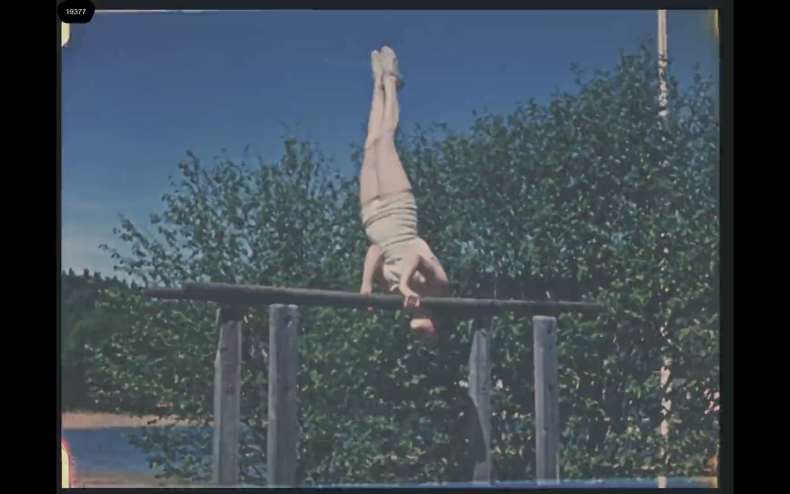

In Braun’s footage, an intriguing aspect emerges: her versatile recordings of leisure time seem to deliberately emulate the shooting styles seen in films like WEGE ZU KRAFT UND SCHÖNHEIT (DE 1925) and OLYMPIA (DE 1938). This is an indication of Braun’s commitment to the spirit of the times and to the ideals of professional filmmaking of her day. Beyond mere documentation, she recreated scenes inspired by Riefenstahl’s OLYMPIA, portraying renowned athletes performing jumps and horizontal bar gymnastics (Images 8 and 9). These scenes, including gymnastics, skiing, waterskiing, table tennis, and casual activities like hanging from a tree branch, emphasize the promotion of Körperkultur (culture of physical fitness) through sports and physical activities. Much like Riefenstahl, Braun appeared to emulate certain filming techniques, including unusual camera angles, smash cuts, extreme close-ups, and slow motion. In doing so, she creatively explored and developed a distinctive visual style in her films, possibly with the intent of echoing Riefenstahl’s methods to emphasize the importance of a healthy body and spirit as promoted by National Socialism.

3.3 Depicting Family Life Through Ambiguous Imagery

Eva Braun Reel # 1 begins with monochrome scenes of people enjoying a sunlit summer day. Activities include swimming in the Königsee near Berchtesgaden and relaxing on mountain slopes. The focal figures are members of Eva’s family: parents Friedrich and Franziska Braun, and sisters Ilsa and Gretl, joined by friends and children. Apart from a brief indoor intermission, likely at the Braun family residence in Munich, outdoor scenes last about ten minutes, portraying typical lower-middle-class gatherings. After a period of economic instability marked by inflation and rising unemployment, Eva Braun’s family reflects the challenges faced by the middle class in pre-war Nazi Germany. Despite grappling with adversity, there was a glimmer of hope in the regime’s initial promises of prosperity. Amidst emerging affluence, the family embraced traditional symbols and customs, fostering a deep connection to nature that instilled a sense of belonging.

With her films, Braun intentionally shapes a petite-bourgeois family image, akin to Roger Odin’s observation that the filmmaker “uses cinema to mold his family.”36 Her meticulous editing creates a visual diary, aiming to convey a profound sense of cultural belonging, family sanctity, and an overall apolitical naivety. Essential to understanding how this representation works is Marianne Hirsch's concept of the “familial gaze.”37 The concept refers to the way in which personal memories and family narratives shape how we understand history and how we perceive images related to that history. It emphasizes the intimate connection between personal and collective experience, particularly when related to trauma and memory. Braun’s films may evoke a familiarity that for many German citizens may trigger memories of family holidays, birthdays and social gatherings. At the same time, the films challenge the viewer to reflect on the ways in which domesticity and personal relationships can co-exist with political ideology and moral atrocities. Frances Guerin addresses this by speaking of a specific awareness that “creates a historical consciousness that, at one and the same time, undermines and is undermined by the familial gaze, a process that triggers our present-day witness to the Nazi past.”38

Beyond the tenth minute of Braun’s initial reel, a surprising sequence unfolds, revealing private moments of Hitler welcoming his closest associates: private secretary Martin Bormann, official photographer Heinrich Hoffmann, personal physician Theodor Morrell, chief adjutant Wilhelm Brückner, and the Berghof household staff from around 1940. This revelation exposes Braun’s ‘second family’—the chosen echelon of highest-class Nazi leaders—fundamentally altering the nature of her films. The previous sense of familiarity is abruptly disrupted here by the realization that the depicted individuals were complicit in human suffering on an unprecedented scale. Building on Dagmar Barnouw’s emphasis on understanding the viewpoint of common Germans, Francis Guerin underscores the importance of acknowledging both the experiences of the victims and the actions of those responsible for historical events.39 This perspective emphasizes that the victims of Nazi policies cannot be ignored when examining the idyllic portrayal of the Braun family.40

The Berghof in Berchtesgaden was Hitler’s holiday house that served as a main Führer Headquarter during the war, providing a stark contrast to the rest of the Reich grappling with the ongoing war. Almost half of Braun’s footage is shot at the Berghof, highlighting its expansive terrace with a breathtaking view of the Obersalzberg mountain side retreat, along with surrounding forested paths and meadows leading to Kehlsteinhaus, also known as ‘Eagle’s Nest.’ Images produced at the Berghof offer a distinct portrayal of the inner circle Hitler surrounded himself with, creating a ‘second family’ within a petite-bourgeois environment. Eva Braun, along with her sister Gretl, appeared to have had the exclusive right to photograph and film Hitler in this intimate setting. The footage is rich with segments that challenge the conventional image of the Führer. Through their lenses, they carefully crafted a specific perception of him as an amiable family figure—pleasant, relaxed, and somewhat aloof.

One of the most iconic scenes, now famously known as the ‘dancing Hitler’ (Image 10), captures him with a surprising naivety and childlike quality. This contrasts sharply with various scenes that depict a contemplative or sentimental Hitler, gazing out over the mountains, or presenting him as a family man—an affectionate figure toward children (Image 11) and a patron of animals, or at least of his German shepherd. Another facet of Braun’s work is evident in sequences showing Hitler visiting his former school or the graves of his parents, exploring his roots and presenting him as a ‘common man.’ This context subtly portrays the petite-bourgeois man as a self-made man, shaping the narrative of the nation’s leader within a progressive storyline, possibly with propagandistic intentions. Hitler was aware of this portrayal—he wasn’t entirely oblivious but seemed to play along, understanding the power of these crafted images.

Moreover, Eva Braun’s documentation extends beyond simply depicting Hitler; it offers rare glimpses into the personal lives of other Nazi leaders, moments that were absent from official media. Scenes of Ribbentrop laughing (Image 13), Goebbels chatting with Gretl, Albert Speer leisurely reading a newspaper, and the iconic trio of Heinrich Himmler, Reinhard Heydrich and Karl Wolff casually conversing or reviewing documents (Image 12)—these all reveal different facets of their personalities. The men at the Berghof exhibit a certain fluidity, transitioning between casual clothing and military or SS uniforms, which significantly alters both their character as individuals and the perception of these images. As footage advances into the later years, a noticeable shift in iconography emerges around 1940. The imagery begins to prominently feature uniformed figures with more somber expressions, occasionally reflecting the war’s toll through subtle details like military camouflage on the Berghof terraces. These elements add layers to our understanding of the Nazi leaders, offering a more complex and multifaceted view beyond the sanitized official narratives.

In addition to personal images, Eva Braun’s documentation also extends to historical events. This raises the question of whether these moments were secretly filmed or whether Braun was privileged to be present. A notable example is the footage found in Braun’s Reel # 7 of Hitler arriving in Berlin following the French campaign on July 6, 1940 (Image 14). Shot in color from the window of the old Reich Chancellery in Berlin, somebody, possibly Braun herself, captures a scene that overlaps with GERMAN NEWSREEL NO. 514 (July 10, 1940), which shows the event filmed by the official crew—albeit in black and white and only up to the entrance of the Reich Chancellery (Image 15).41

This convergence creates the situation where two different recordings intersect: a black-and-white recording by an official cameraman positioned in a building opposite the Reich Chancellery, and a recording possibly by Eva Braun, who may have been seated on a windowsill on the first floor of the Chancellery. Although this may seem coincidental, it highlights Braun’s privileged position. It is known that Braun accompanied Hitler on some of his work trips to Berlin, and her access to a small apartment in the Chancellery42 enabled her to document significant historical events alongside official film productions. Unlike the official filmmakers, Braun did not actively participate, but remained in the private quarters, filming from a window. This gives her footage a distinctly private character, as well as a clandestine quality. The extent of Braun’s permission to film various events, particularly at the Berghof, is still debated—especially regarding her recordings of historically significant encounters with figures like Count Ciano or Hitler’s meetings with ministers such as Goebbels, Ribbentrop, and Himmler. The clandestine nature of her filming is emphasized by her camera work, often done through windows or doors.

To sum up, making films was a unique form of agency for Eva Braun within the constraints of the Nazi regime. Through her films, she was able to navigate and express certain Nazi ideals of femininity, finding both personal expression and a way to conform to the ideological narrative of the time. Combining personal passion with political agency, her work illustrates the complex and often contradictory nature of her position within the Nazi hierarchy. Eva Braun’s Munich family films differ significantly from those shot at the Berghof, marked by a noticeable formality tied to historical gravity, the setting, and the prominent presence of the Führer. Braun assumes a role aligned with upper-class decorum and solemnity, departing from her previous exuberant middle-class lifestyle. She shaped her identity in relation to Hitler, often producing an idealized version of herself (Images 16 and 17). The Berghof recordings offer insights into social mobility and privilege, expanding the viewer’s perspective beyond the initial “familial gaze” to a broader historical narrative, acknowledging German complicity in significant injustice.

4. Early Usage of Eva Braun's Films and Their Subsequent Resonance

Eva Braun’s efforts to project an image of herself as a progressive, self-aware, and empowered young woman, immersed in the ideals of her era and surrounded by loved ones, underwent a profound shift over the past 60 years. Initially, these images aimed to convey a sense of personal and societal advancement. However, their discovery and reinterpretation in the post-war period led to a dramatic transformation in their meaning and reception. As these images were re-examined, they began to reveal more than just a feel-good narrative. They became part of a broader discourse that explored deeper ‘truths and insights’ about their context.

The investigation into how original film footage is repurposed in media post-1945 involves a thorough examination of how these images are recontextualized to transform their initial meanings and purposes. The focus is particularly on archival exploration, where the diverse meanings of images within their archival contexts become evident, shedding light on shifts in perception, usage, and significance over time. These archival images are frequently repurposed in new film productions, utilizing methods such as appropriation, citation, and other forms of engagement. For instance, Frances Guerin employs the term “recycling” to describe this phenomenon, emphasizing that films often serve purposes contrary to those advocated by historians, cultural critics, and politicians, particularly in terms of remembrance.43

Initially, Eva Braun’s authorship of the footage went largely unrecognized, but as her role became acknowledged, the focus shifted to the profound intimacy and enigmatic aspects of her life that the films reveal. Frances Guerin underscores the importance of Braun’s identity, noting that her films transform into “objects of fascination recorded by a historical person,”44 thereby highlighting how Braun’s personal identity is key to interpreting her home movies and understanding their value as historical documents. Odin further argues that “to read a home movie as a document is to ‘use’ it for something that is not its own function,”45 a viewpoint that has shaped the reception of Braun’s footage since its discovery in 1946. This shift in interpretation illustrates how her films have been repurposed beyond their original context, reflecting a broader re-evaluation of their historical significance.

As previously noted, the Eva Braun films were initially showcased in two American newsreels: UNIVERSAL NEWSREEL VOLUME 20, RELEASE 15 (US, February 20, 1947), and PARAMOUNT NEWS 52 (US, March-April 1947). The UNIVERSAL NEWSREEL segment, which lacks sound, runs for nearly 2 minutes and includes clips from Eva Braun Reels # 1 and # 2, labeled “Hitler’s Heyday.” In contrast, the PARAMOUNT NEWS segment features sound, with an opening title announcing “The Hitler-Eva Braun Films!” and is accompanied by dramatic music and a narrator who describes the footage as “one of the most amazing intimate records of modern times.” Both newsreels begin and end with the same footage. The opening scene depicts Eva Braun in a flower meadow, while the closing scene features French soldiers at the Berghof, captured in footage filmed by the French Liberation Army. The PARAMOUNT NEWSREEL not only repeats much of the footage from the UNIVERSAL NEWSREEL but also includes additional scenes, extending the total runtime. This repetition highlights several iconic family scenes, including Eva picking flowers, conversing with Hitler on the terrace, waterskiing, and other moments that become central to the narrative of Braun’s life and her relationship with Hitler. These scenes emphasize different aspects of her persona—her conforming femininity and traditionalism, as well as her sportsmanship and sense of freedom. Together, they contribute to the sensational portrayal of her privileged status as Hitler’s hidden mistress.

From the initial re-contextualization of Eva Braun’s seemingly comfortable and oblivious life, a distinctive comparative mode of image usage emerges. This approach sharply contrasts the idyllic Nazi existence with the horrors of the war they propagated. On one level, this contrast occurs through the juxtaposition of Braun’s footage with various Holocaust images. For example, scenes of Braun enjoying leisure activities are placed alongside harrowing footage from concentration camps. On another level, the narration reinforces this comparison, blending contrasting narratives within single sentences. Phrases like “And while Eva cavorted, the years of world agony marched on”46 and “... but far from the horrors of the labor and concentration camps” highlight the disparity between the two realities.47

Similarly, scenes such as “Ribbentrop laughing” and “Hitler dancing” are used to depict the seemingly carefree Nazi joy amidst the backdrop of war, which is starkly contrasted with footage of the liberation of the concentration camp in Silesia (Images 18 and 19). The lines like “Here, no respect, no worries, no misfortune, and there...”48 underscore the divide between the luxurious Nazi life and the suffering of the victims. Through these techniques, the narrative and images work together to shift the initial context and meaning, emphasizing the stark contrast between the privileged Nazi world and the atrocities they were complicit in.

At this point, the Eva Braun films are re-evaluated in the context of the historical circumstances in which they were created. What was once seen as a positive tool for shaping national identity and promoting the ‘cult of the Führer’ is now repurposed to convey a contrasting message. These images were gradually shifted from personal memorabilia to historical documents with significant political implications, revealing aspects of Nazi life—particularly Adolf Hitler’s private life—that were previously concealed from the public. This shift aims to challenge the notion that life in Germany during the Nazi era was ‘normal’, questions the simplistic idea that ‘ordinary’ Germans were merely innocent bystanders, and addresses the complicity of those who supported and perpetuated the regime’s horrors.

Soon after gaining attention, the material was featured in several productions, including two European ones—NAZISTI ALLA SBARRA: IL PROCESSO DI NORIMBERGA (IT 1947) and AUTANT EN EMPORTE L’HISTOIRE (FR 1949)—as well as two American ones, LOVE LIFE OF ADOLPH HITLER (a.k.a. WILL IT HAPPEN AGAIN?, US 1948) and THE SECRET LIFE OF ADOLPH HITLER (WAR IN EUROPE SO1E10, US 1951). Interesting about these productions is the fact that they all use nearly the same footage. The first film, which is the oldest and shortest, uses the least amount of this footage, whereas all of it is repeated in the other three productions. The French production introduces a significant amount of Braun’s footage, adding a dramatic narrative about her as a courtesan and the possible mother of Hitler’s son. Braun’s authorship is not acknowledged; instead, it is suggested that Eva’s personal cameramen, supposedly assigned by Hitler, might have filmed some segments, with hints that Hitler himself could have been involved in the filming. The two later American productions reuse most of the footage from the French one and follow its narrative. A satirical portrayal of Eva as Hitler’s lover, nicknamed “Little Eva,” is also prominently featured. All these films use footage of Braun and her friends engaging in sports, sunbathing, or flirting to emphasize their perceived lascivious nature as women. Additionally, the sequence of “Himmler, Heydrich, and Wolff’ became iconic through the films that repeatedly used it as a visual shorthand, contrasting it with various images of the Holocaust.

The first integration of Eva Braun’s films into a German production was the 1953 film BIS FÜNF NACH ZWÖLF. This film covers the 30-year period from the start of World War I in 1914 to the end of Nazi rule in 1945, suggesting that many Germans lacked a solid foundation in democratic principles. After its premiere in November 1953, the film was censored and banned nationwide by Federal Minister of the Interior Gerhard Schröder, who feared it might “revive Nazi aspirations.”49 Unlike the rather sensationalistic American newsreels, this film takes a more explanatory approach, using various archival footage. Eva Braun’s authorship of the materials remains unacknowledged, and claims that a friend documented events at the Berghof are presented without verification. The film also addresses myths about Hitler and Eva Braun’s alleged son, using Braun’s footage with children to illustrate these claims, while clarifying that the children were actually those of her friends or family. Braun’s footage is primarily employed to demystify her, portraying her as an “ordinary figure” who was used to humanize Hitler—a quality, the film argues, he was reluctant to embrace in his pursuit of “Übermenschlichkeit.”50

After BIS FÜNF NACH ZWÖLF, Braun’s footage appeared in numerous other films, albeit in smaller amounts, with a greater focus on Hitler and other key Nazi figures rather than on Braun herself. Notably, all the footage used comes from Braun’s first two reels and is, albeit filmed in color, consistently presented in black and white, often flipped. This error of flipped material, which originated with the early American newsreels, persisted in subsequent films, suggesting that many later productions reused material from earlier ones. These early reproductions established iconic scenes that became staples in later films, including Hitler dancing; Himmler, Heydrich, and Wolff; Hitler contemplating; Ribbentrop smiling; Hitler with a little girl; Hitler in a reclining chair; Goebbels at the Berghof; Hitler and Eva on the terrace; Eva picking flowers; Eva with a child; and Eva doing gymnastics by the lake.

A turning point in the use of Braun’s footage came with the release of SWASTIKA (GB 1973), directed by Australian filmmaker Phillip Mora and produced by German writer Lutz Becker. At its premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in 1973, the screening was interrupted by protests and altercations among the audience.51 The film included propaganda and newsreel footage from Nazi Germany showcasing the country’s progress but lacked any commentary. This omission led to severe criticism, as it left the images open to potentially positive interpretations. A crucial yet understated moment in the film occurs around the halfway mark, presenting a stark and abstract contrast intended as a sharp critique of Nazism. This sequence juxtaposes the emotionally charged footage of Hitler with a little girl at the Berghof from Eva Braun’s Reel # 7 against harrowing scenes of starving, begging children in the Warsaw Ghetto (Images 20 and 21). The strong disparity between these images serves as a powerful, albeit subtle, condemnation of the regime, following the earlier tradition of presenting Braun’s material, as previously discussed, rather than being an original idea of Becker or Mora.

What is notable in this case is the manipulation of the material, which is characterized by the addition of a sound layer and lip-syncing designed to suggest diegetic sounds and potential conversations.52 This layer serves not only to clarify the content but also to make it more accessible and emotionally impactful for the audience. Georges Didi-Hubermann, in his analysis of the four Sonderkommando photographs from Auschwitz, discusses such alterations: “This absurd doctoring [...] reveals an urgent desire to give a face to what in the image itself is no more than movement, blur, and event.”53 He views this transformation of images as an effort “to make them more informative than they were in their initial state.”54 This approach, however, raises significant concerns in the case of Braun’s footage in SWASTIKA. By leaving the images unexplained and manipulating them with added sound layers, the film distorts the original material, provoking heightened emotional responses that can mislead the audience and compromise the integrity of the historical record.

Notably, the Eva Braun films were extensively utilized in their original, non-flipped form, in color, and beyond the initial two reels. The accurate application of these films is largely due to the research conducted by the movie’s scriptwriter, Lutz Becker. Although it is mistakenly claimed that Becker was the first to discover these films in the National Archives,55 he was indeed the first to correctly attribute them as “Home Movies of Eva Braun.” This crucial identification generated significant interest and led to increased archival efforts to preserve and explore this material.56

Following the release of SWASTIKA, the use and analysis of Eva Braun’s footage expanded significantly, reflecting a growing interest in understanding the private dynamics of Hitler’s inner circle. Notably, some subsequent works aimed to achieve similar goals as SWASTIKA, such as David Howard’s HITLER’S PRIVATE WORLD (GB 2006), which sought to uncover the conversations and environment at the Berghof through this intimate footage. In addition to documentary approaches, there have been notable reenactments and dramatic interpretations of Braun’s and Hitler’s privacy. For instance, Alexander Sokurov’s MOLOCH (RU 1999) is a fictionalized account that dramatizes Hitler’s life, including his relationship with Eva Braun, in a manner that explores the psychological and personal dimensions of their interactions. Similarly, ADOLF AND EVA (DE 2008) by the German director Bernd Fischerauer is another reenactment that provides a dramatized portrayal of the couple’s personal and political life.

On the more scholarly side, Serge Viallet’s episode from MYSTÈRES D’ARCHIVES: 1940: EVA BRAUN FILME HITLER (FR 2015) stands out as a significant piece of research. This episode is one of the most thorough scientific analyses of the footage, examining the details of the scenes, such as dates, individuals, and the authenticity of the material. Viallet’s work uses various cross-media methods, integrating Braun’s footage with other films, photographs, and newspapers from the era, providing a comprehensive and contextualized understanding. While the initial use of Braun’s films was essential for promoting critical historical analysis, its examination in Viallet’s film highlights the significance of thorough research and the integration of various archival documents. This approach emphasizes the need to analyze the image itself rather than merely employing it for illustrative or sensational purposes. As ethical considerations gain increasing importance, future uses of archival materials may adopt a more cautious and reflective stance, aiming to maintain historical integrity while fostering meaningful discussions about the past.

- 1

United States Forces European Theater was a name given to the European Theater of Operations, United States Army (ETOUSA) after the war in 1945. ETOUSA was a Theater of Operations responsible for directing United States Army operations throughout World War II, from 1942 to 1945. See National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), “Shipment No. 76,” File Unit: 940.4076,NAID: 169214078, accessed July 25, 2024, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/169214078.

- 2

Ibid.

- 3

See National Archives and Records Administration, “Private Motion Pictures of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun,” NAID: 43461, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/43461; National Archives and Records Administration, “Eva Braun’s Photo Albums,” ca. 1913-ca.1944., NAID: 540149, accessed July 25, 2024, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/540149.

- 4

See Frances Guerin, Through Amateur Eyes: Film and Photography in Nazi Germany (Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 218.

- 5

See Roger Odin, “Reflections on the Family Home Movie as Document: A Semio-Pragmatic Approach,” in Mining the Home Movie Excavations in Histories and Memories, ed. Karen L. Ishizuka and Patricia R. Zimmermann (Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2008), 262.

- 6

See Guerin, Through Amateur Eyes, 275.

- 7

Ibid., 278.

- 8

See National Archives and Records Administration,“Shipment No. 76.”

- 9

Ibid.

- 10

Ibid.

- 11

See Michael E. Ruane, “Hitler’s girlfriend filmed Nazis relaxing and the Fuhrer (sic!) dancing. Now the Footage is going digital,” The Washington Post, April 10, 2019,https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/04/10/hitlers-girlfriend-fi….

- 12

Ibid.

- 13

See Robert McCrum and Taylor Downing, “The Hitler home movies: how Eva Braun documented the dictator’s private life,” Guardian, January 27, 2013, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jan/27/hitler-home-movies-eva-br…

- 14

Ruane, “Hitler’s girlfriend filmed Nazis relaxing and the Fuhrer (sic!) dancing.”

- 15

See National Archives and Records Administration(NARA), “Braun, Eva I, 1945, Motion Pictures, Request of legal opinion regarding the status of Eva Braun Home movies,”November 10, 1975.

- 16

Bundesarchiv, Abt. Filmarchiv, Findbuch zu den Amateurfilmen der Eva Braun.

- 17

More about the project “Filmikonen: Bilder die Folgen haben,” accessed August 29, 2024, https://filmikonen.projekte-filmuni.de/.

- 18

See Guerin, Through Amateur Eyes, 30.

- 19

See Efrén Cuevas, “Change of Scale: Home Movies as Microhistory in Documentary Films,” in Amateur Filmmaking: The Home Movie, the Archive, the Web, eds. Laura Rascaroli, Gwenda Young and Barry Monahan, (New York/London: Bloomsbury, 2014), 139.

- 20

See Patricia R. Zimmermann, Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995), xii.

- 21

Ibid.

- 22

See Angela Lambert, The Lost Life of Eva Braun, (London: Century, 2006); Heike B. Görtemaker, Eva Braun: Life with Hitler (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011); Johanna Gehmacher, “I Never Loved Eva Braun: Geschichtspolitische Funktionen einer nachträglichen Ikone des Nationalsozialismus,” OZG 19, no. 2 (2008): DOI: https://doi.org/10.25365/oezg-2008-19-2-7.

- 23

Johanna Gehmacher points out that Eva Braun also appears in a whole range of song lyrics in which new wave and punk bands such as Die Ärzte (“She was the most beautiful of all women – Eva Braun”) play with the manifold implications associated with her name. See Gehmacher, “I Never Loved Eva Braun,” 146.

- 24

As depicted in a scene filmed by Eva Braun (Reel # 7, t.c. 00:33:17:10, presumably 1940/1941), Walther Hewel, State Secretary in the Foreign Office and SS Brigadeführer, presents a 16mm film camera to Hitler on the Berghof terrace.

- 25

See Henriette von Schirach, Frauen um Hitler: Nach Materialien (Munich and Berlin, 1983), 230.

- 26

See Görtemaker, Eva Braun, 171.

- 27

See Henriette von Schirach, Der Preis der Herrlichkeit (Munich and Berlin, 1975), 23/97.; Görtemaker, Eva Braun, 208.

- 28

See Jürgen Matthäus, “Kriegsfotos auf dem Obersalzberg. Anmerkungen zu Eva Brauns Albumsammlung,” Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 69 (2021), 230.

- 29

SeeGuerin, Through Amateur Eyes, 223.

- 30

Ibid.

- 31

See Görtemaker, Eva Braun, 30.

- 32

First mentioned in MYSTÈRES D’ARCHIVES: 1940: EVA BRAUN FILME HITLER (Serge Viallet, FR 2015).

- 33

See Barbara Hahn, Unter falschem Namen (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1991), 7.

- 34

See film Bis fünf nach Zwölf (Richard von Schenk, DE 1953), t.c. 00:25:30.

- 35

See Michael Wildt, “Volksgemeinschaft,”: 1.0, in Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte (June 03, 2014), http://docupedia.de/zg/wildt_volksgemeinschaft_v1_de_2014, accessed June 29, 2024.

- 36

See Odin, “Reflections on the Family Home Movie as Document,” 257.

- 37

See Marianne Hirsch, “Introduction,” in The Familial Gaze (Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1999), xiii.

- 38

See Guerin, Through Amateur Eyes, 220.

- 39

Ibid., 221.

- 40

Ibid., 219.

- 41

First mentioned in MYSTÈRES D’ARCHIVES: 1940: EVA BRAUN FILME HITLER (Serge Viallet, FR 2015).

- 42

See Görtemaker, Eva Braun, 33.

- 43

See Guerin, Through Amateur Eyes, 215.

- 44

Ibid., 245.

- 45

See Odin, “Reflections on the Family Home Movie as Document,” 261.

- 46

See PARAMOUNT NEWS 52, Motion Picture Herald (US March-April 1947), t.c. 00:05:30

- 47

See Love Life of Adolph Hitler (aka Will it happen Again?, US 1948), t.c. 00:51:52

- 48

See Autant en emporte l‘histoire - La vie privée d'Hitler et d'Eva Braun (FR 1949), t.c. 00:39:55.

- 49

See Jürgen Kniep, „Keine Jugendfreigabe!“ Filmzensur in Westdeutschland 1949–1990, (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2010), 105.

- 50

See BIS FÜNF NACH ZWÖLF, t.c. 00:29:25

- 51

McCrum and Downing, “The Hitler home movies.”

- 52

The diagetic soundtracks added to the Eva Braun film material can also be found in the film ES MUSS EIN STÜCK VOM HITLER SEIN (DE 1963).

- 53

Georges Didi-Huberman, Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz, translated by Shane B. Lillis (Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008), 34.

- 54

Ibid.

- 55

Before making SWASTIKA, Philippe Mora and Lutz Becker intended to adapt Albert Speer’s book Erinnerungen into a film in 1970, but this endeavor proved unsuccessful. However, during their archival research, they came across a photograph depicting Eva Braun filming Hitler with a 16mm handheld camera. See McCrum and Downing, “The Hitler home movies.”

- 56

McCrum and Downing, “The Hitler home movies.”

Bundesarchiv, Abt. Filmarchiv, Findbuch zu den Amateurfilmen der Eva Braun.

Cuevas, Efrén. “Change of Scale: Home Movies as Microhistory in Documentary Films,” “Introduction Amateur Filmmaking: New Developments and Directions.” In Amateur Filmmaking: The Home Movie, the Archive, the Web, edited by Laura Rascaroli, Gwenda Young and Barry Monahan. New York/London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Images in Spite of All: Four Photographs from Auschwitz. Translated by Shane B. Lillis. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press, 2008.

“Filmikonen: Bilder die Folgen haben.” Accessed December 29, 2023, https://filmikonen.projekte-filmuni.de/.

Gehmacher, Johanna. “I Never Loved Eva Braun: Geschichtspolitische Funktionen einer nachträglichen Ikone des Nationalsozialismus.” OZG 19, no. 2 (2008): 145–170. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25365/oezg-2008-19-2-7.

Görtemaker, Heike B. Eva Braun: Life with Hitler. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011.

Guerin, Frances. Through Amateur Eyes: Film and Photography in Nazi Germany. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Hahn, Barbara. Unter falschem Namen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1991.

Hirsch, Marianne. “Introduction.” In The Familial Gaze. Hanover, N.H.: University Press of New England, 1999.

Kniep, Jürgen. “Keine Jugendfreigabe!” Filmzensur in Westdeutschland 1949–1990. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2010.

Lambert, Angela. The Lost Life of Eva Braun. London: Century, 2006.

Matthäus, Jürgen. “Kriegsfotos auf dem Obersalzberg. Anmerkungen zu Eva Brauns Albumsammlung.” Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 69, 2021.

McCrum, Robert, and Taylor Downing. “The Hitler home movies: how Eva Braun documented the dictator’s private life.” Guardian, January 27, 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/jan/27/hitler-home-movies-eva-br….

National Archives and Records Administration (NARA). “File Unit: 940.4076 Shipment No. 76.” NAID: 169214078. Accessed December 25, 2023. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/169214078.

—. “Private Motion Pictures of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun.” Accessed December 25, 2023. https://archive.org/details/Eva-Braun-Home-Videos.

—. “Eva Braun’s Photo Albums, ca. 1913-ca.1944.” NAID: 540149. Accessed December 25. 2023. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/540149.

—. “Braun, Eva I, 1945, Motion Pictures, Request of legal opinion regarding the status of Eva Braun Home movies.” November 10, 1975. Accessed December 25, 2023.

Odin, Roger. “Reflections on the Family Home Movie as Document A Semio-Pragmatic Approach.” In Mining the Home Movie Excavations in Histories and Memories, edited by Karen L. Ishizuka and Patricia R. Zimmermann, 255–271. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2008.

Rascaroli, Laura, Gwenda Young, and Barry Monahan, eds. Amateur Filmmaking: The Home Movie, the Archive, the Web. New York/London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Ruane, Michael E. “Hitler’s girlfriend filmed Nazis relaxing and the Fuhrer (sic!) dancing. Now the Footage is going digital.” The Washington Post, April 10, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2019/04/10/hitlers-girlfriend-fi….

Schirach, Henriette von. Der Preis der Herrlichkeit. Munich and Berlin: Herbig, 1975.

—. Frauen um Hitler: Nach Materialien. Munich and Berlin: Herbig, 1983.

Zimmermann, Patricia R. Reel Families: A Social History of Amateur Film. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1995.