DER EWIGE JUDE (1940)

A Multi-perspective Evaluation

Table of Contents

From THE NAZI PLAN (1945) Backwards

TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (1935)

Contested Memory

DER EWIGE JUDE (1940)

From Home Movie to Historical Document

A Living Document

Archiving the Ghetto

The Westerbork Film

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Körling, Daniel. “DER EWIGE JUDE (1940): A Multi-perspective Evaluation.” Research in Film and History 7 (2025): 1–57. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/24049.

Introduction

When DER EWIGE JUDE (Fritz Hippler, DE 1940; hereinafter shortened to DEJ) premiered at the UFA-Palast in Berlin on November 18, 1940, few could have predicted its dark legacy as the single most infamous antisemitic propaganda film ever made. Hitler and Goebbels personally intervened several times in the final design of this regime’s abomination, no expense or effort was spared, and numerous tests were carried out, making DEJ a unique ideological example of the Nazi regime.

But what inspired the outcome of DER EWIGE JUDE and how does such toxic footage live on? This article reveals its origins and how fragments of this Nazi-era film have scattered across documentaries for more than 60 years – some handle these poisonous images with the proper warnings and context, while others, disturbingly, repackage them as generic historical footage, stripped of their murderous intent. In addition to the continuity of DER EWIGE JUDE, this article examines its production, followed by an analysis of the exhibition Der ewige Jude and its accompanying booklet as prototypes for the film. Nevertheless, the primary focus is on the utilization of DEJ in other films and the circulation of its images.

DEJ is a frequently analyzed film; its antisemitism, production, content, and reception during the National Socialist era are the predominant topics of study. The physical footage used in the film has been thoroughly examined as well, most notably by Stig Hornshøj-Møller. However, research on its utilization remains a gap in scholarship that this article aims to address.

In examining the film’s utilization, it is crucial to scrutinize the footage itself. The guiding question is: to what extent is DEJ integrated into filmic narratives as a specific historical source, compared to its material being used illustratively, without context? Therefore, the term ‘utilization’ is used when discussing the citation of footage generally, while ‘appropriation’ and ‘usage’ denote more specific forms of utilization.

DEJ was released in several versions, the best known of which was restricted for adult male German audiences, while a slightly edited version was permitted for women and juveniles. During the occupation of the Netherlands and France, Dutch and French versions were produced respectively.1 Additionally, an international version with German commentary circulated throughout Europe. This text focuses exclusively on the first version mentioned.

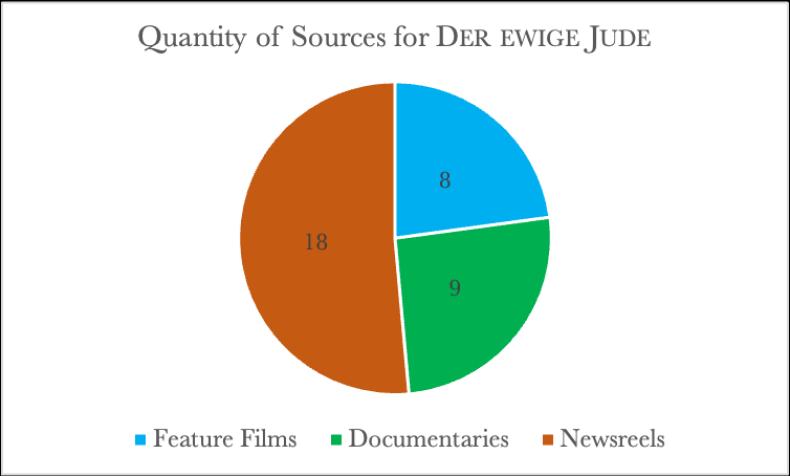

As a compilation film, DEJ incorporates two other iconic audiovisual film materials studied in the Filmikonen project: TRIUMPH DES WILLENS (Leni Riefenstahl, DE 1935) and Hitler’s Reichstag speech of January 30, 1939. Consequently, it is considered both a source (a working definition of DEJ as a source will be given) and a carrier (a film utilizing material from a source).

Background and Structure

DER EWIGE JUDE is one of the most misanthropic and inflammatory audiovisual works. Released in 1940 and advertised as a “Dokument zum Problem des Weltjudentum” (Document on the problem of world Jewry), the film can retrospectively be classified as a foreshadowing of the escalation of the Holocaust. By incorporating Hitler’s aforementioned speech, it aggressively promotes “die Vernichtung der jüdischen Rasse in Europa” (the annihilation of the Jewish race in Europe), aiming to persuade the public about the necessity of extreme measures against the Jewish population, and it advocates for the continuation of the war. Both aspects were closely intertwined.

The idea for a feature-length film about the so-called ‘Eastern Jewry’ in Poland, before World War II one of the countries with the largest Jewish population in the world, had already been discussed among the German government in the years before. However, due to the refusal of the Polish government, the plans had to be abandoned. On September 1, 1939, the situation changed: starting from October, recordings of the Jewish population, especially in the larger cities, were produced on behalf of Joseph Goebbels, Minister für Volksaufklärung und Propaganda (Minister for Popular Enlightenment and Propaganda). These recordings were primarily used in newsreels and in the propaganda film FELDZUG IN POLEN (Fritz Hippler, DE 1940). Films and photos were produced following the instruction to create antisemitic subjects such as “Jewish snipers”, “Jews working for the first time”, or “greedy Jewish traders”.2

For DEJ, the footage was mainly shot in Lodz – at that time the second largest center of the Jewish population in Europe with about 230,000 Jewish Poles.3 Only a few scenes were filmed in Warsaw.4 The influence of Goebbels’ ministry is evident as Hippler was simultaneously head of its film department. Eberhard Taubert wrote the commentary, which was voiced by the well-known newsreel speaker Harry Giese.5

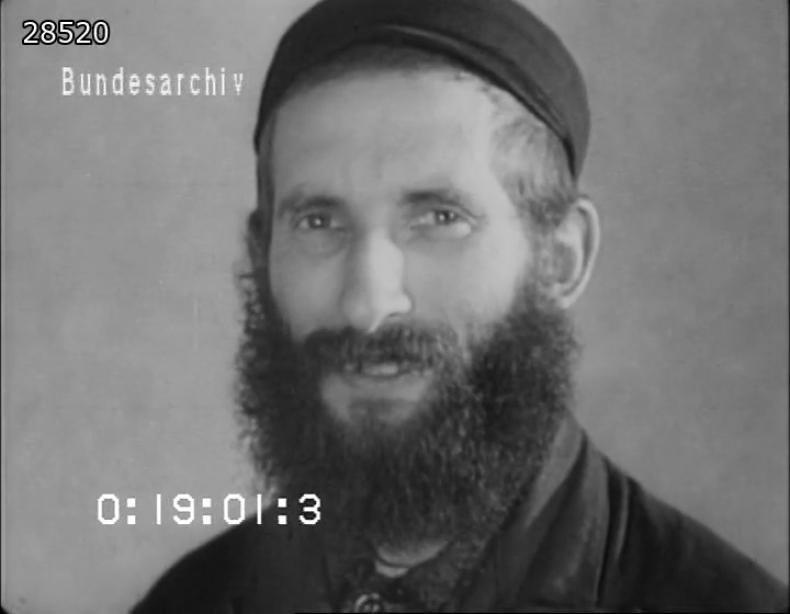

The onset of World War II provided an opportunity to (cinematically) highlight the Jews as enemies of Germany. Special emphasis is placed on depicting the conditions of the predominantly Jewish neighborhoods in Poland. The streets and apartments are shown as dirty and chaotic, as are the people being filmed. The sky is not visible, intensifying the impression of a hostile area.

These harsh conditions were primarily a result of German persecution and of an order issued on October 5 that conscripted the Jewish population into forced labor. The portrayals of the Jewish people are visually and auditorily supported through defamatory camera work and music. For example, a bird’s-eye view is employed to deindividualize and stigmatize the individuals as ‘others’6; sharp contrasts to convey an impression of filth, darkness, and illicit activities. Unsurprisingly, the commentary claims that poverty is not the issue. Instead, it suggests that Jews deliberately conceal their prosperity and exploit the wealth of other nations.

To support this claim, footage of people engaging in trade is shown, including scenes inside synagogues. An article from November 30, 1940, in the German film magazine Der Film states: “Für ihn ist das Geld gleichsam Selbstzweck. Er braucht es gar nicht auszugeben, sondern er ist schon glücklich, wenn er es besitzt” (For him, money is an end in itself, as it were. He doesn’t need to spend it at all; he is already happy when he possesses it).7 Overall, the footage from Poland aims to depict the people as objects of investigation and dehumanized entities. With its fast editing and commentary, the film prevents a thorough examination but instead emotionally shocks the viewers – a “cinematic Blitzkrieg of anti-Semitism.”8 DEJ is the opposite of an objective movie – through its content and aesthetics it deliberately aims to suppress the independent thinking of the audience.

The dehumanization of Jews is particularly linked to the scene featuring rats: Jewish people are explicitly equated with pathogens and depicted as a grave threat, posing a significant risk to the progress of ‘civilized’ nations. While associations with animals such as donkeys, scorpions, and pigs were already prevalent in German-speaking regions before 1933, during National Socialism comparisons with pests and parasites like rats and bedbugs were increasingly promoted.9

The intention behind the dehumanization was to establish a clear division from the rest of the population, ultimately serving to legitimize genocide. “Here [the release of DEJ], the campaign against the Jews reaches its zenith. This is the end of the propaganda war, the beginning of mass extermination” (UNDERGÅNGENS ARKITEKTUR (ARCHITECTURE OF DOOM, Peter Cohen, SE 1989, 01:20:52–01:21:01). In addition to depicting Jewish Poles, DEJ targets public figures primarily from Germany, people from the spheres of politics, business, and culture. The primary focus is to discredit the Weimar Republic and its representatives – “jene trübe Zeit, in der Deutschland am Boden lag” (that bleak time when Germany hit rock bottom; 00:30:35–00:30:37), beginning with the November 1918 revolution and the subsequent election to the National Assembly in 1919. Officials are frequently depicted, and their names are mentioned with the appended word “Jude” (Jew) – thereby attributing the alleged hostility against Germany solely to their Jewish identity.

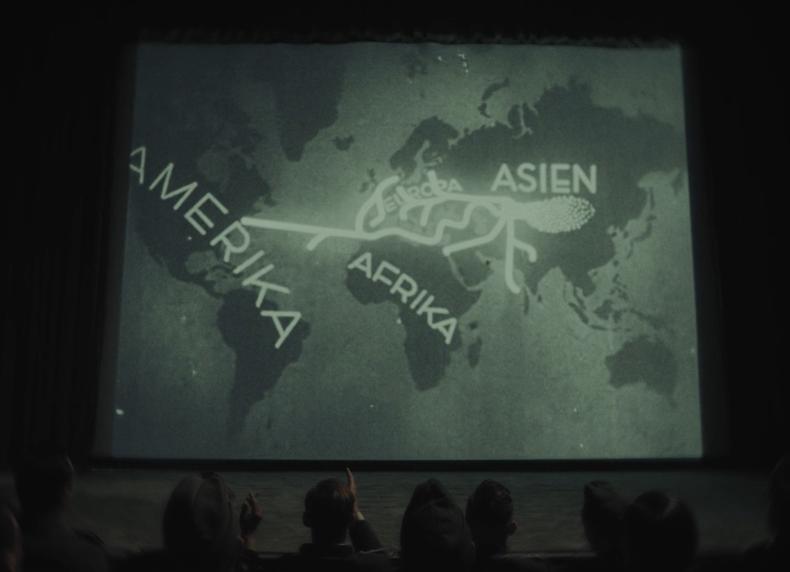

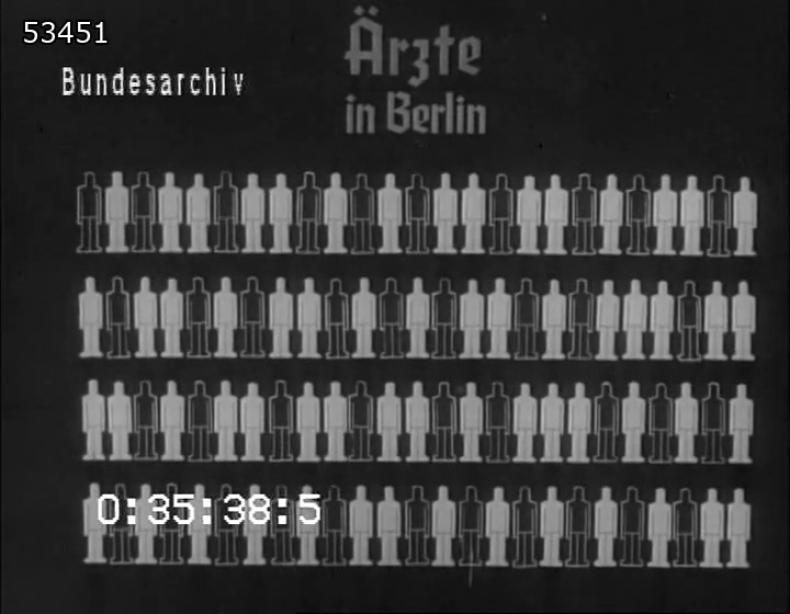

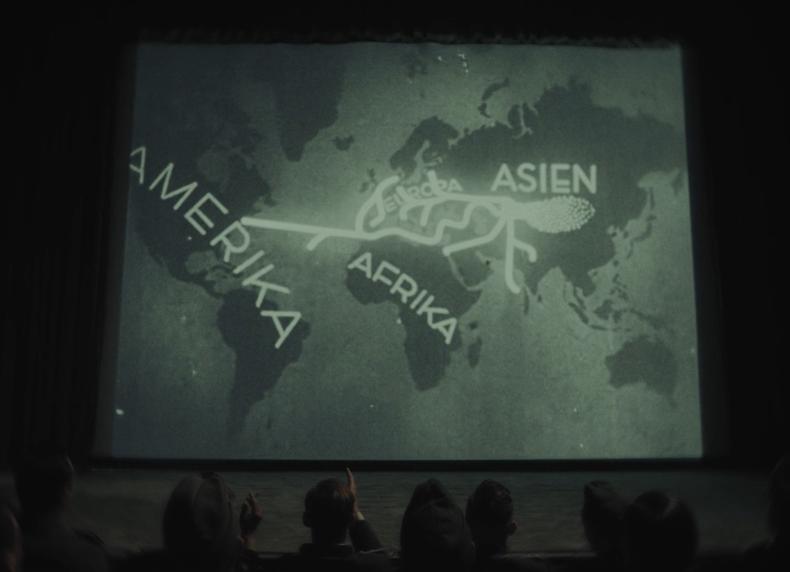

Furthermore, the film employs various animations, e.g., to portray the historical-global dispersion of Jews and alleges the influence of Jewish individuals in certain professions in Germany. Multiple statistics are fabricated or greatly exaggerated; modern art is defamed by labeling it as “Jewish art.” This is contrasted with art described as “Aryan.” This category of trick cards are intended to give the film a scientific veneer, classify it as an objective description of the irrefutable facts, and thus counter vulgar antisemitism with a supposedly ‘serious’ form. Antisemitism should not only be a negative feeling but also a scientific imperative, especially aimed against the alleged Jewish global conspiracy.

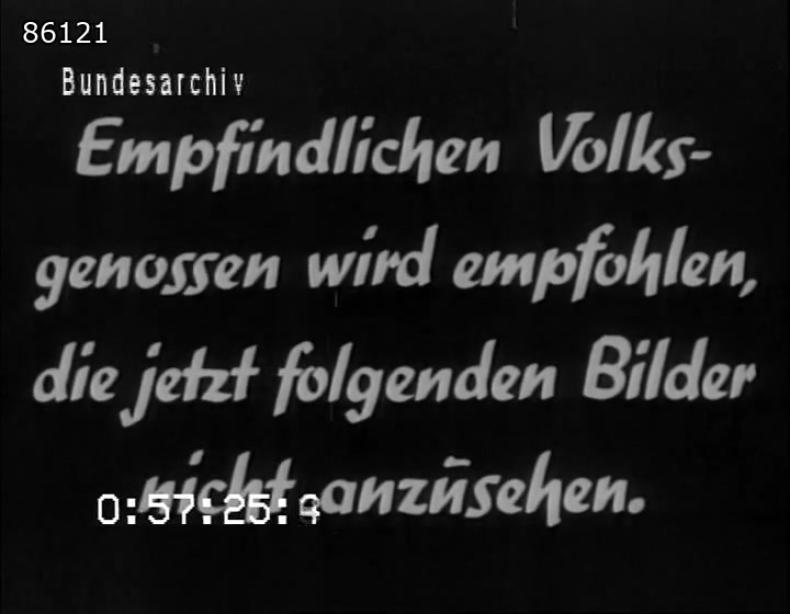

The argumentative climax occurs in a sequence that focuses on kosher butchering. Numerous animals are slaughtered according to Jewish religious customs10; the film describes it as a ruthless and painful killing. Generally, comparisons with animals have a highly symbolic function in DEJ: Jews are compared to flies and rats, pests that harm mankind and must be exterminated. Finally, the equation with butchered mammals is an anticipating metaphor for the only reliable solution: the Jewish people, now on the other side of the scaffold, receive the punishment they deserve.

These scenes were used solely in the version for male adults. Partially fabricated newspaper articles claiming demands for the prohibition of kosher butchering by National Socialism before 1933 accompany them. Finally, Hitler’s Reichstag speech from January 30, 1939, shots of marching soldiers, and German children conclude the movie. According to DEJ, Germany is well prepared for a positive future due to its anti-Jewish policies: “Das ewige Gesetz der Natur, die Rasse rein zu halten ist für alle Zeiten das Vermächtnis der nationalsozialistischen Bewegung an das deutsche Volk” (The eternal law of nature to keep the race pure is for all time the legacy of the National Socialist movement to the German people, 01:04:45–01:04:56).

Through its content and form, the film establishes a connection with the off-screen reality in Nazi Germany, enhancing its image of credibility, objectivity, and truthfulness. It constructs a worldview depicting an eternal fight between Good and Evil, with “the Aryans” portrayed as the virtuous side and “the Jews” associated with everything despised and rejected. The material purportedly promoting ‘Aryan labor’ or the ‘Aryan youth’ is included to counter the footage shot in Poland and to reinforce the film’s overall propaganda message. After disturbance and disgust are brought upon the audience, the film reintegrates it under the banner of National Socialism, employing the ‘shock effect’ to evoke a broad range of emotions towards the Jews and the ideology of National Socialism11: at first, the viewers are presented with the ultimate enemy, “the Jew”, who is portrayed as an fundamental danger to the nation and its population, but finally, the solution to this threat is also presented in the form of National Socialism. And if National Socialism is accepted as a solution, the film implies, then its measures should also be accepted.

From a contemporary perspective, DEJ can be characterized as a document – one, that explicitly reveals the intentions of the Nazi regime’s policies targeting the Jewish population. It sets out the goals of the National Socialists and therefore features colonial, eugenic, and geostrategic schemes, providing insight into the ideology propagated by the Nazi regime.12 “The Jew” functions here as the ultimate evil, which must be fought in its entirety: on the one hand by complete exclusion from German society, and on the other by actively combating its “Niststätte” (nesting place, as it is called in the film) across Europe. Contrary to the statements of Stig Hornshøj-Møller and David Culbert13, DER EWIGE JUDE, particularly its ending, argues precisely for the extermination of the European Jewish population by adopting a scientific stance coupled with sequences that evoke fear, disgust, and hate – and ultimately a rehabilitation of the viewers under the messages and means of racial purity.

Exhibition and Booklet – Predecessors of DER EWIGE JUDE?

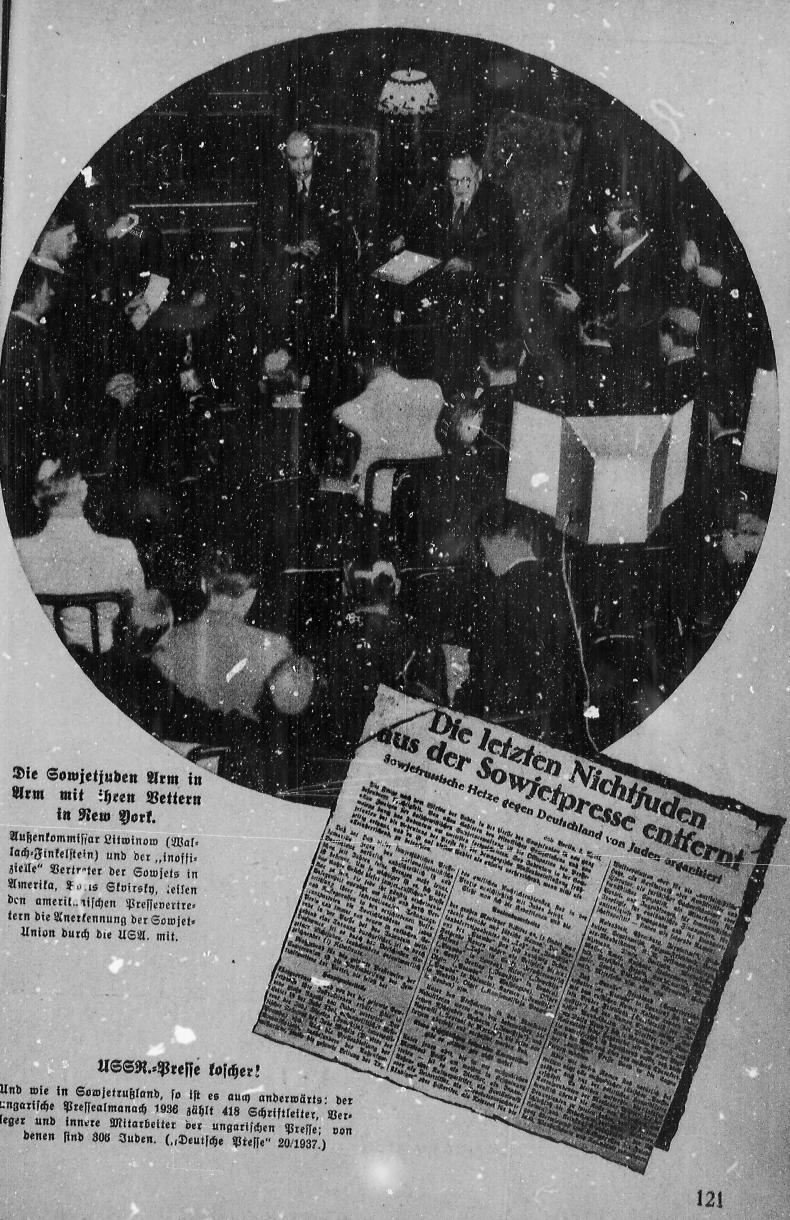

DEJ and the preceding exhibition of the same name were part of a series of antisemitic cultural products during the National Socialist era. The regime considered them essential to gain widespread approval for its anti-Jewish policy and state propaganda became an integral part of the government’s strategy. Newspapers such as Der Stürmer and Der völkische Beobachter played a particularly prominent role. In addition, traveling exhibitions had a crucial function in the late 1930s. The Third Reich was characterized by widespread presence of so-called anti-exhibitions (exhibitions specifically developed ‘against’ something/someone to define the own ingroup by excluding pre-defined outgroups and the politically or socially accepted/unaccepted), including Die große antibolschewistische Schau (Great Anti-Bolshevik Show, Munich 1936), Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art, Munich 1937), Entartete Musik (Degenerate Music. Düsseldorf 1938), and Das Sowjetparadies (The Soviet Paradise, Berlin 1942). These exhibitions predominantly presented a strong antisemitic, anti-modern, and anti-Bolshevik bias. The exhibition Der ewige Jude was therefore no isolated case.

Otto Nippold, deputy Gauleiter of Munich-Upper Bavaria, spearheaded the initiative, Walther Wüster, the Gau’s deputy director for propaganda, was responsible for its implementation, and the bookseller Fritz von Valtier as well as the painter Horst Schlüter for the design.14 The opening took place in the library building of the Deutsches Museum in Munich on November 8, 1937, as part of the annual anniversary of the attempted Hitler putsch of 1923.15 Subsequently, the exhibition traveled throughout the Reich.16 After the occupation of France in 1940, it was also shown there, organized by the Institut d’étude des questions juives, whose founder Theodor Dannecker was a member of the SS and the so-called Judenreferent in Paris. The French version of DER EWIGE JUDE, LE PÉRIL JUIF, and another antisemitic film, LES CORRUPTEURS (Pierre Ramelot, FR 1942), were shown in this context.17

The exhibition aimed to elicit an emotional response from the public while presenting arguments based on facts and reason – the exhibits were designed to create an appearance of objectivity. But at the same time, the exhibition architecture was primarily geared toward agitation.18 Using multimedia techniques, the goal was to engage the broader public beyond the traditional museum audience.19 Among these techniques was a film screening showing stills and sequences of films from the Weimar Republic. After almost two months, these sequences were exchanged with JUDEN OHNE MASKE (Walter Böttcher, Leo von der Schmiede, DE 1938), a propaganda film using the same technique of attacking Jews as DEJ by appropriating footage from feature films. Therefore, it can be considered a predecessor.20 Moreover, excerpts from a film about kosher butchering were also shown during the same screening.21

Notably, no official exhibition catalog was published, and only descriptions and pictures from private individuals and newspapers are available. However, shortly after the opening, the Franz Eher-Verlag (a publishing house owned by the NSDAP) published a booklet serving as a substitute. It was conceived and written by Hans Diebow, editor of the Völkischer Beobachter and member of the NSDAP. The following analysis therefore primarily focuses on the booklet. It consists of 129 pages with 256 images and accompanying texts. An introduction by Diebow sets the tone for the narrative of the publication. The so-called Humboldt-Hardenberg Law of 1812, which extended basic rights to the Jewish population in Prussia, is presented as a cardinal error. This mistake had been corrected with the Nuremberg Laws, and “ein Aufgehen des Judentums im deutschen Blute” (an absorption of Judaism into German blood) had finally been prevented. According to the booklet, enforcing a separation was deemed necessary. Assimilation, which had been attempted for a long time, had ultimately failed.22 The influence of Jews on the monarchies was cited as the reason for their emancipation, the latter had been financially dependent on them and consequently had been pushed towards granting equal rights. This assertion would later be reiterated in the film JUD SÜSS (Veit Harlan, D 1940).

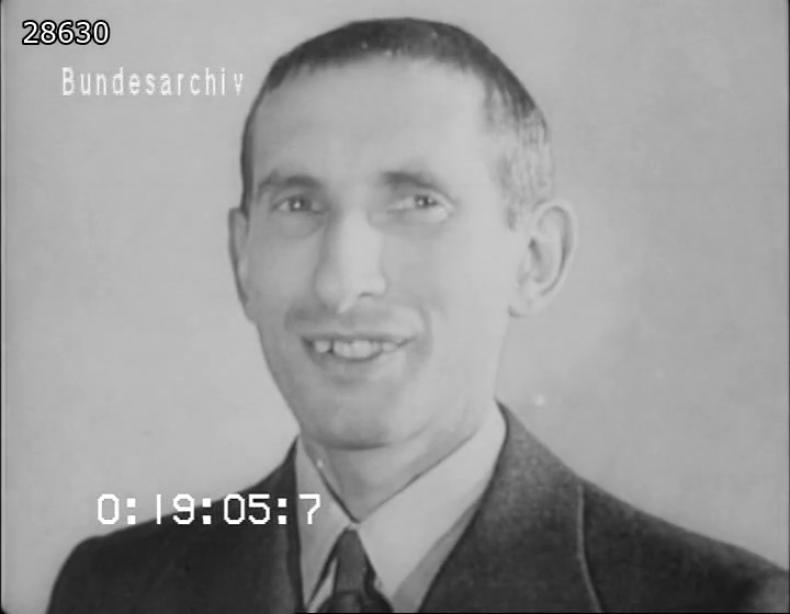

Additionally, Diebow’s booklet is strongly based on a racist argument: Jews are biologically distinct from non-Jews. Thus, the nose is highlighted as a distinguishing characteristic23, an argument also presented in the exhibition.24 According to the booklet and the film, Jews were able to harness their dangerous potential, because one of their essential characteristics was mimicry – the ability to disguise oneself, to adapt, and to cover up dishonest motives. Assimilation was hence only deception and dazzle: Jews continued to act secretly to increase their wealth and harm the rest of the population. The film attempts to visually substantiate this argument by showing young men getting shaved, claiming that people previously identified as Eastern European Jews could no longer be differentiated from the rest of the population in Germany. The image of ‘Eastern Jewry’, which was widely disseminated during World War I, significantly shaped the public image of Jewish life – despite major differences to emancipated Jews in the Reich.25

The film and the booklet both attack well-known individuals, such as Karl Marx, Alfred Kerr, and Eugene Leviné, and even use the same photos of them. Moreover, both the booklet and the film associate Jews with numerous concepts and ideas rejected by the Nazis, like liberalism, democracy, sexual education, communism, capitalism, and pacifism. Individuals are chosen as representatives of these concepts and linked to Jewry, discrediting these concepts and Jews alike. Both cultural assets employ a homogeneous categorization of “the Jews”, presenting them as a monolithic group with the implication that they are all the same. This representation serves to dehumanize the Jewish people through several key strategies:

- Innate behavior: the actions and characteristics of Jews are portrayed as inherent and unchangeable, rather than as individual traits or cultural practices.

- Biological alienation: Jews are described as biologically distinct from other groups, furthering their othering and dehumanization.

- Lack of individuality: by presenting Jews as a uniform group, the propaganda denies them individual identities, personalities, and experiences.

- Stereotyping: DEJ and the booklet rely heavily on negative stereotypes, reinforcing pre-existing prejudices and creating new ones.

- Visual representation: the imagery used in both mediums is carefully selected and manipulated to support these dehumanizing narratives.

However, there are also considerable differences between the exhibition and the film. The most striking of these is the rather marginal thematization of Eastern European Jews in the booklet. With the outbreak of World War II and an emerging escalation of violence, the situation changed dramatically, influencing the film’s production. Additionally, the booklet still grants Jews the concession of having their own cultural and social life.26 This aspect is absent in DEJ. The retrospectively significant events of the November 1938 pogroms and the onset of World War II were considerable turning points escalating the antisemitic rhetoric and measures against Jews.

The film avoids direct criticism of the Soviet Union due to the political situation in 1939/40 (the Hitler-Stalin pact). While communism is indirectly referred to by way of Karl Marx and Rosa Luxemburg, the communist state is not a topic. In contrast, the booklet portrays it as massively hostile toward Germany, describing the state as Jewish-dominated, and referring to it as “Sowjet-Judäa” (Soviet Judaea).27

Compared to the booklet, the film’s radicalization is also evident in its omission of any reference to Zionism. In the booklet, the idea of a Jewish state is seen as inconsequently organized, but in principle, the Nazis are said to sympathize with the concept. However, during the film’s production, the idea of a Jewish state was no longer part of the considerations regarding the Jewish population within the German sphere of power. Instead, eliminatory ideas were increasingly contemplated. The most significant disparity is that the film presents an eliminationist argumentation, which is not as explicitly radical in the booklet. The film includes comparisons with parasites and indirectly implies a call for genocide. Overall, the booklet presumably influenced the structure and content of the film, but political radicalization ultimately played a decisive role in shaping the final form of the latter.

In conclusion, there are several notable similarities between the booklet and the film. Both portray Jews as alien enemies of Germany. They defame the same individuals and groups, sometimes using identical visual material, and rely on fundamentally racist arguments. The exhibition and the booklet were intended to have both an exclusionary and an integrative effect on the audience – the boundaries were sharply drawn. Both intend to demarcate the Volksgemeinschaft from the outside – but remain very vague when defining the inside. Only the regime is supposed to function as an integral element, but nothing unifying is presented beyond that (What was it supposed to be, when language and history were shared with the excluded?). Basically, this was the central aspect of the idea of the Volksgemeinschaft: first and foremost, it was defined who did ‘not’ belong to it – this boundary was immovably drawn but it needed to be emphasized frequently through films like DEJ and the anti-exhibitions. The concept of the Volksgemeinschaft was aligned towards the future (like the marching soldiers and young Germans and the end of DEJ). It was seen as the ideal type of society to be achieved, to which large parts of the population could relate to.28

Several elements of DEJ appear to have been directly inspired by, or even copied from, the preceding booklet and exhibition. These earlier works served as prototypes for the film.29 Additionally, JUDEN OHNE MASKE and the exhibition’s focus on film material produced during the Weimar Republic likely influenced the outcome of DEJ. The event’s success, which was visited by more than 1,300,000 people30, called for an adaptation.

Footage utilized in DER EWIGE JUDE

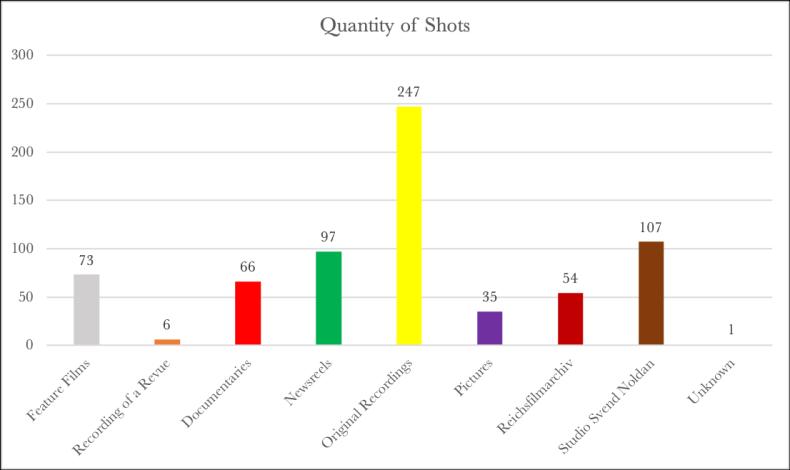

In his source-critical analysis, Hornshøj-Møller traces every single shot back to its origin; the following structure is based on his findings. DEJ primarily utilizes original footage, alongside material from feature films, documentaries, and newsreels. It also incorporates a wide variety of photos and footage from the Reichsfilmarchiv.31 Studio Svend Noldan produced the text panels and other ‘Trick Cards’. In total, the film consists of 686 shots.32 The oldest footage (photos excluded) is from spring 1919 (newsreels about the so-called Spartacist or January uprising), and the most recent is from fall 1939 (newsreels on the invasion of Poland as well as the originally produced content).

DEJ incorporates substantial footage produced in Nazi Germany. As mentioned earlier, TRIUMPH DES WILLENS is one example, but many other materials that were sourced from the Reichsfilmarchiv and various other propagandistic movies (such as HÄNDE AM WERK – EIN LIED VON DEUTSCHER ARBEIT (Walter Frentz, DE 1935) and SCHÖNHEIT DER ARBEIT (Arthur Anwander, DE 1934)) carry propagandistic messages as well. The origin of one photo depicting the Reichstag building from the outside remains unknown.

Categories of Footage

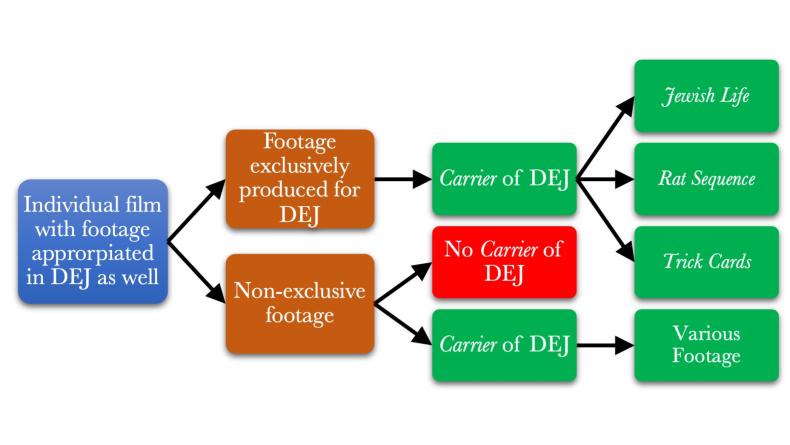

The compilation nature of DEJ raises the question: which material was produced exclusively for it, and which footage cannot be uniquely attributed to DEJ? This distinction is crucial, especially for statistically valid statements. As both source and carrier, it is important to identify the origins of its footage.

Two opposing positions can be taken: the broad definition attributes every shot to DEJ. Hence, all carriers that share the same footage with DEJ would be included in this corpus. However, this definition inevitably poses obstacles since it is in many cases very challenging to distinguish whether certain materials were utilized from DEJ or whether they were taken from various original films. For example, a documentary that exclusively quotes shots from 01. MAI – FEIERTAG DER ARBEITERKLASSE (Phil Jutzi, DE 1929), also utilized in DEJ, cannot necessarily qualify as a carrier of DER EWIGE JUDE. Therefore, a narrow definition that distinguishes between the footage is needed:

- First group: footage originally produced for DEJ.

- Second group: footage not exclusively produced for DEJ.

Shots from the first group are attributed to the film, whereas each footage requires individual consideration for the second group. Editing, music, or commentary in a carrier sometimes allows identification whether a certain material from the second group was taken from a copy of DEJ or from the respective original film. According to this working definition, a documentary that utilizes footage from 01. MAI – FEIERTAG DER ARBEITERKLASSE, may very well be considered a carrier – if the footage can be traced back to DEJ, for example, based on the commentary, the soundtrack, or the editing. Indeterminable cases, however, are attributed to the original film and not considered carriers. Considering this distinction, it seems purposeful to establish three individual categories to structure the highly diverse footage of DER EWIGE JUDE.

The first comprises the footage mainly filmed in Poland, recorded in studios (the scene with the ‘Jewish bourgeoise’) or, for the foreign versions, in the Netherlands (streets and various markets in Amsterdam). This can be subsumed under the collective term ‘Jewish life’, although the material is hardly authentic. Instead, it represents the interval between the beginning of the war and the ghettoization.

The second category is the ‘Rat Sequence’. Notably, all shots except one were taken from the documentary KAMPF DEN RATTEN! (Richard Groschopp, DE 193733). However, as the footage constitutes a crucial element of the film and has never been copied from the original film but exclusively from DEJ, grouping the material into one individual category makes sense for analytical reasons.

The third category includes the maps, text panels, statistics, and the opening credits – collectively called ‘Trick Cards’. This category contains the juxtapositions of supposedly different views of art as well, even if they are not trick cards in the true sense of the word. However, since Studio Svend Noldan considerably altered the source material (for example, photos of famous paintings and sculptures) using cross-fades and specific sequence editing, and it is therefore not a mere sequence of shots, these sequences are assigned to the third category.

The following diagram visualizes the differentiations:

As mentioned, the footage from the second group – the material not exclusively produced for DEJ but utilized in it – can sometimes unequivocally be attributed to DEJ. For instance, TRIUMPH DES WILLENS and newsreel material is frequently utilized in carriers via DEJ and can be linked to it based on the same commentary or editing/succession of shots. However, pinpointing the exact origin of the footage remains challenging in numerous cases. Currently, only three films that do not appropriate any of the exclusive footage (first group) can undoubtedly be regarded as carriers. They need further examination and are therefore not discussed in this article.

Utilizations

Overview

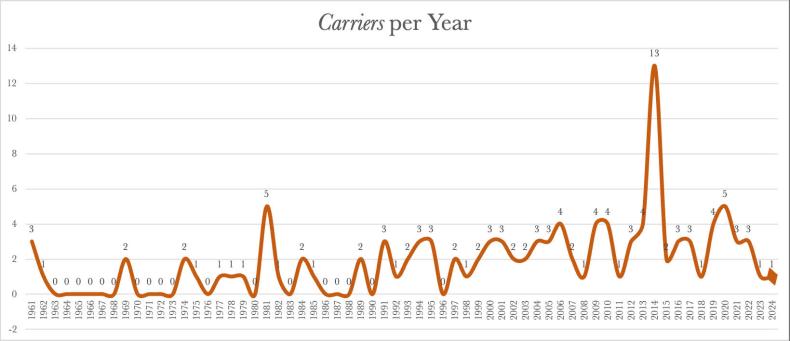

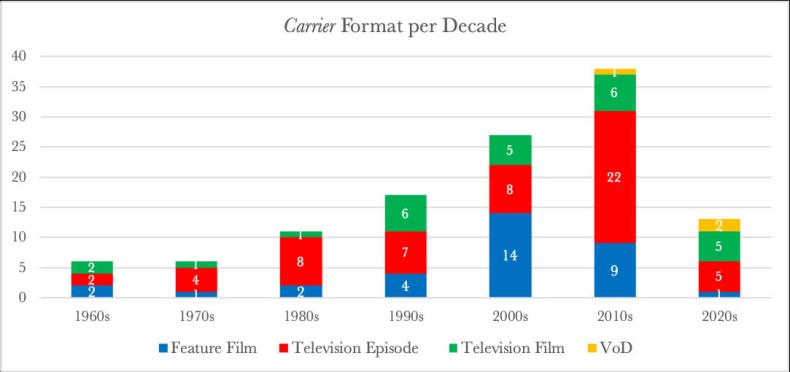

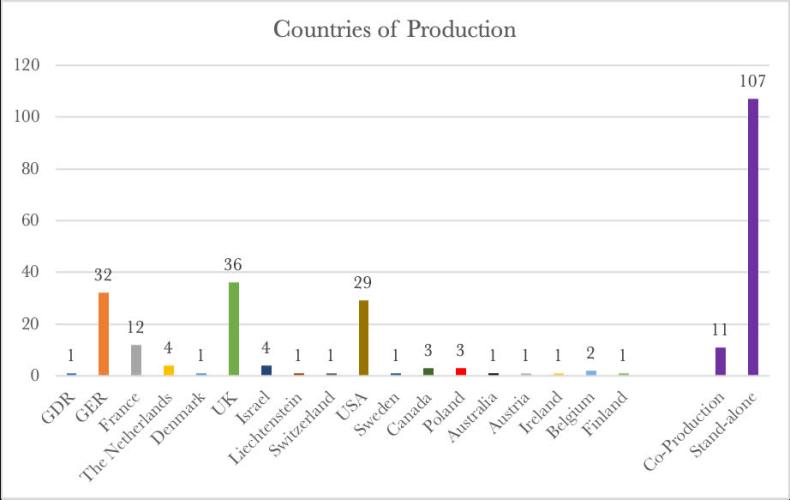

In total, 118 carriers have been identified so far. Considering the film’s reputation in the context of Nazi film propaganda and antisemitism, this low quantity surprises, especially when compared to other sources in our project.34 It seems that many films that deal with anti-Semitism in the Nazi era either exclude the propaganda factor or do not want to go into the (apparently) necessary depth of the topic. To facilitate the analysis of changes in the utilization of the material, these carriers were structured in terms of their release year, format, and country of production.

According to the data, DEJ was never utilized until 1961 when three documentaries included material from it in their compilations: AKTION J (Walter Heynowski, GDR), AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS: ADOLF EICHMANN – SEIN LEBEN IN DOKUMENTEN (Peter Schier-Gribowsky, DE), and LE TEMPS DU GHETTO (Frédéric Rossif, FR). All three carriers deal with the Holocaust and were published, not coincidentally, at the time of the trial of Adolf Eichmann. The ‘rediscovery’ was consequently closely related to the public and legal confrontation with the Holocaust; using the footage from DEJ as audiovisual evidence for the antisemitic propaganda of the Nazi regime and its atrocities (another source, the LIEPAJA EXECUTIONS FILM filmed by Reinhard Wiener in 1941, also surfaced in 1961 and was likewise first utilized in AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS).

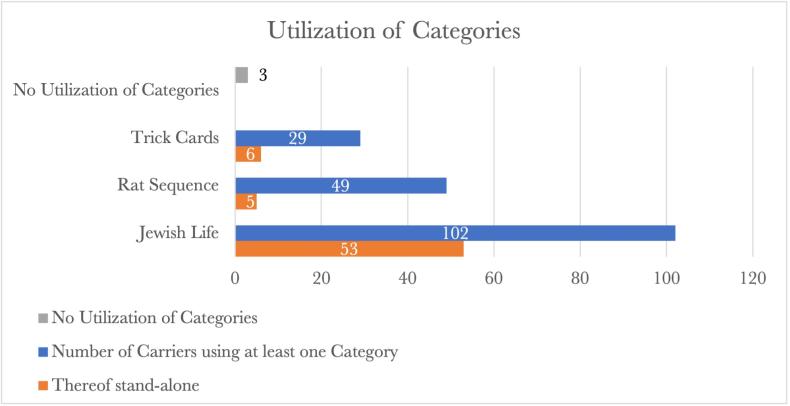

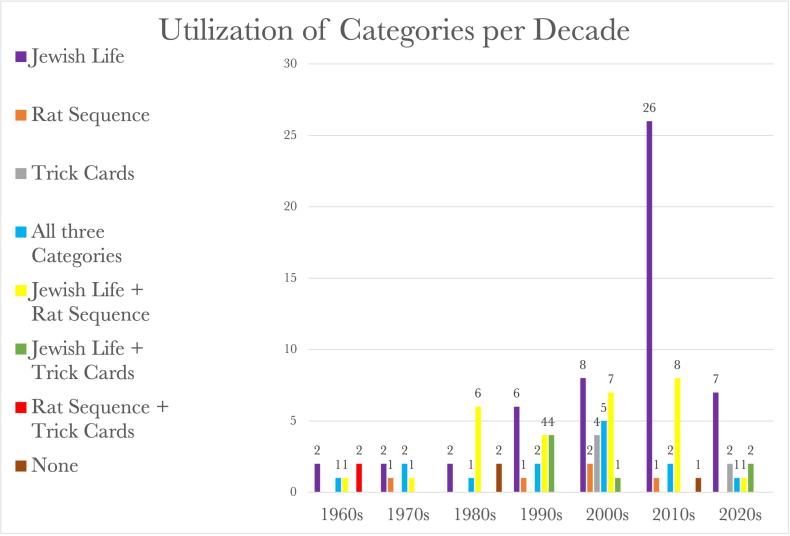

Utilizations of Categories

The category ‘Jewish Life’ predominates by far; it is striking that 53 carriers have utilized footage from ‘Jewish Life’ alone. The following chart displays how the categories are combined. A more detailed breakdown shows that carriers only utilizing material from ‘Jewish Life’ have formed the vast majority since the 2010s.

This development can be further correlated with the contextualization of the footage by referencing its origin.

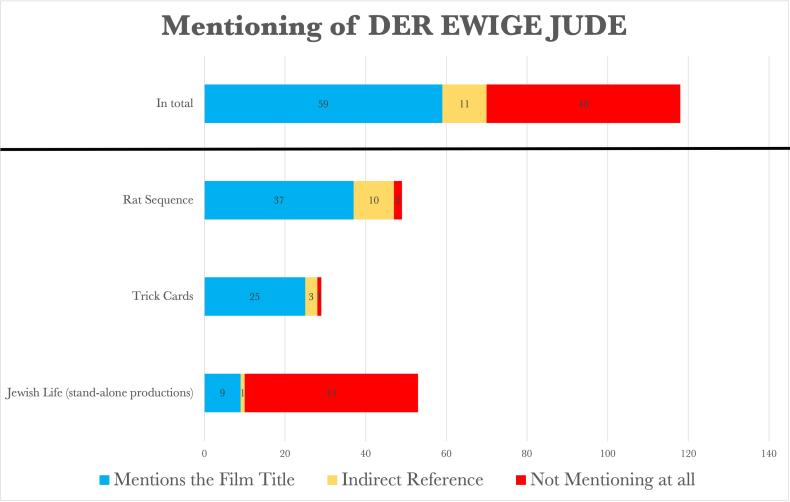

Referencing DER EWIGE JUDE

A disclosing approach is closely connected with a rather unique feature of the carriers of DEJ: the widespread direct or indirect reference to the origin of the footage and thus their narrative integration into the film plot. This referencing and integration is particularly evident in the appropriation of ‘Trick Cards’ and the ‘Rat Sequence’, drawing attention to the source itself. To refer to it, either the title is named in the commentary or captions are used, indicating where the footage is appropriated from. In these cases, it is a direct reference. Altogether, 59 carriers name the origin of the footage, which is half of all carriers.

In contrast, in indirect instances, a general reference to a ‘propaganda film’ is made, or a film-in-film situation implies that the material was originally distributed in cinemas during the Third Reich. Eleven carriers have indirectly referenced DEJ so far. As carriers do not regularly appropriate DEJ without further contextualization, this signals a sensitivity for the material. However, as depicted in the following chart, there are instances where no indication of the footage’s origin is provided, which applies to a total of 48 carriers.35

The footage of the ‘Rat Sequence’ and the ‘Trick Cards’ is either too inhuman or incomprehensible without context, so a reference to DEJ itself must be made. In these cases, DEJ is directly integrated into the film plot (in most, but not all instances, DEJ is treated as a subtopic of National Socialism). This sets the film apart from other iconic material evaluated in the project where such identification has rarely been observed. The frequent reference and thematization as an independent topic do not apply to the other propaganda film, TRIUMPH DES WILLENS, either. However, concerning the material from ‘Jewish Life’, insofar as it is utilized autonomously (in a sequence without the other two categories), this pattern cannot be found. Indeed, there are cases, like EVOLUTION OF EVIL: S01E02 (DE/GB 2015; 00:20:27–00:20:35), in which the origin of the voice-over is mentioned but not that of the images. Consequently, the utilization of the categories diverges to a great extent. This suggests the presence of different approaches to the categories (and the iconic materials in general) and a division between contextualized (appropriation) and uncontextualized (usage) utilization. In the further course of this article, this division will be examined in more detail. At the same time, the use of one of these two concepts (usage and appropriation) will provide a clear indication of which mode of utilization is present in a specific carrier.

Utilization of DER EWIGE JUDE

Decontextualizing DER EWIGE JUDE

In various cases carriers use visual material from the ‘Jewish Life’ category in a way that deviates from its original context – e. g., ARCHAEOLOGY: S01E07 (Phil Comeau, US 1991; 00:04:44–00:04:47) and HOW TO BECOME A TYRANT: S01E01 (Harry Chaskin, Ron Myrick, Emily Gerich, US 2021; 00:06:59–00:07:00). These films use a shot of a person expressing grievances about unidentified circumstances to illustrate the political and social unrest in the Weimar Republic or the mobilization of the masses through hatred. Another example of frequently decontextualized footage is a long bird’s eye take covering crowds. In the case of DEJ, there are only a few shots that are used in a decontextualized way.

The division between appropriation and usage already began in 1961. LE TEMPS DU GHETTO uses the footage from DEJ in a purely illustrative way – survivors talk about the horror of World War II and the Holocaust; a commentary integrates the personal stories in their historical context. An additional soundtrack adds an auditory layer to the objects in the image, for example, the creaking of a trolley or murmuring in the background. In its credits, the French documentary, presumably contrary to its knowledge, claims, that all the footage in this movie was recorded in the Warsaw Ghetto and could be considered as “une filmographie complète des conquêtes du IIIème reich” (a complete filmography of the conquests of the Third Reich). The correct origin of these images, altogether 53 shots (one-fifth of the footage in DEJ shot in Poland), including the two already mentioned with the angry woman and the crowd, is not indicated anywhere.

From here on, and especially with the spread of television, just a few shots began to proliferate. This development is particularly evident in Anglo-Saxon TV productions: on the one hand, these are more numerous than, for example, continental European productions due to the size of the market, and on the other hand, they sometimes deal with quite far-fetched topics (such as NS and the occult). Many of these carriers are simply and repetitively illustrated with random images due to a lack of original footage or the desire to reduce costs. This particularly concerns the footage from the ‘Jewish Life’ category.

Eight of the 21 most utilized shots are from the ‘Rat Sequence’ and one from ‘Trick Cards’. Of the twelve remaining shots, five from ‘Jewish Life’ are in the context of the ‘Rat Sequence’, as they follow directly afterward and are intended to support the comparison. Two are from Hitler’s Reichstag Speech, leaving five shots from the ‘Jewish Life’ category. One of them is shot #149, first used in LE TEMPS DU GHETTO. The editing of this shot is quite an unambiguous indication of the function of this carrier as a kind of quarry, using a specific sequence that has spread further and further.

Shot #149 is utilized 35 times, of which five mention the footage’s origin. Most of the 30 remaining usages are contextualized with the Warsaw Ghetto, but others are distributed regarding their specific content. The following table lists all the 30 unreferenced usages (four carriers use the shot twice; eventually 26 non-referential individual carriers have been identified).

Table 01:

|

Carrier |

TC |

Release Year |

Release Format |

Contextualization |

|

LE TEMPS DU GHETTO |

00:12:32, |

1961 |

Feature Film |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

PILLAR OF FIRE - S01E05 |

00:06:59 |

1981 |

TV Episode |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

HERITAGE: CIVILIZATION AND THE JEWS – S01E08 |

00:32:52 |

1984 |

TV Episode |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

THE HOLOCAUST: IN MEMORY OF MILLIONS |

00:17:22 |

1994 |

TV Film |

– The uprising in the Warsaw Ghetto 1943 |

|

LIBERATION |

00:16:17 |

1994 |

Feature Film |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

HISTORY FILE: NAZI GERMANY – S01E03 |

00:18:38 |

1997 |

TV Episode |

– Annihilation of the Jews in Europe |

|

THE MOST EVIL MEN AND WOMEN IN HISTORY – S01E05 |

00:18:25 |

2001 |

TV Episode |

– Annihilation of the Jews in Europe |

|

HIDDEN: POLAND |

00:14:04 |

2003 |

Feature Film |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

AUSCHWITZ |

00:16:55 |

2004 |

Feature Film |

– Situation in the General Government |

|

MY OPPOSITION: THE DIARIES OF FRIEDRICH KELLNER |

00:40:54 |

2007 |

TV Film |

– Annihilation of the Jews in Europe |

|

NAZI COLLABORATORS – S01E02 |

00:14:14 |

2010 |

TV Episode |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

NAZI COLLABORATORS – S01E09 |

00:11:20 |

2010 |

TV Episode |

– Prosecution of the Jews in Germany |

|

NAZI HUNTERS – S01E10 |

00:07:28, |

2010 |

TV Episode |

– Eichmann studying Jewish culture and learning Hebrew |

|

DEATH CAMP TREBLINKA: SURVIVOR STORY |

00:03:19 |

2012 |

TV Film |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

AFTER AUSCHWITZ |

00:01:07 |

2013 |

Feature Film |

– The Holocaust as the worst crime in human history |

|

A JOURNEY INTO THE HOLOCAUST |

00:39:53 |

2014 |

Feature Film |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

JEWISH CAVIAR |

00:14:39 |

2014 |

Feature Film |

– Poland as the nation with the largest Jewish population in Europe prior to World War II |

|

THE UNSEEN HOLOCAUST |

00:35:49 |

2014 |

TV Film |

– Massacres at Babi Yar |

|

DIE WAHRHEIT ÜBER DEN HOLOCAUST – S01E02 |

00:37:06 |

2014 |

TV Episode |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

THE RISE OF THE NAZI PARTY – S01E07 |

00:02:16 |

2014 |

TV Episode |

– Annihilation of the Jews in Europe |

|

EVOLUTION OF EVIL – S01E02 |

00:31:50 |

2015 |

TV Episode |

– Prosecution of the Jews in Germany |

|

DEFYING THE NAZIS: THE SHARPS' WAR |

00:21:45 |

2016 |

TV Film |

– Jewish refugees in Prague during the German invasion |

|

TRUE EVIL: THE MAKING OF A NAZI – S01E01 |

00:28:08, |

2020 |

TV Episode |

– Suppression of the opposition by Goebbels in Germany – Impossibility of the total suppression of knowledge about the ghettos and camps |

|

TRUE EVIL: THE MAKING OF A NAZI – S01E05 |

00:26:51 |

2020 |

TV Episode |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

|

HOW THE NAZIS LOST THE WAR – S01E03 |

00:10:18, |

2021 |

TV Episode |

– Prosecution of the Jews in Germany – Prosecution of the Jews in Poland |

|

THE US AND THE HOLOCAUST – S01E02 |

00:52:17 |

2022 |

TV Episode |

– Situation in the Warsaw Ghetto |

Additionally, the first usage of this shot in LE TEMPS DU GHETTO, in which two shots from (presumably) the Warsaw Ghetto are edited before #149, was ultimately fundamental to four other carriers listed above:

Table 02:

|

|

LE TEMPS DU GHETTO: 00:12:28. |

LE TEMPS DU GHETTO: 00:12:30. |

LE TEMPS DU GHETTO: 00:12:33. |

|

|

|||

|

|

AMUD HA'ESH – S01E05: 00:06:56. |

AMUD HA'ESH – S01E05: 00:06:58. |

AMUD HA'ESH – S01E05: 00:07:00. |

|

|

|||

|

|

HERITAGE – CIVILISATION AND THE.JEWS – S01E08: 00:32:47. |

HERITAGE – CIVILISATION AND THE.JEWS – S01E08: 00:32:50 |

HERITAGE – CIVILISATION AND THE.JEWS – S01E08: 00:32:53. |

|

|

|||

|

|

NAZI HUNTERS – S01E10: 00:07:44. |

NAZI HUNTERS – S01E10: 00:07:47. |

NAZI HUNTERS – S01E10: 00:07:49. |

|

|

|||

|

|

A JOURNEY INTO THE HOLOCAUST: 00:39:51. |

A JOURNEY INTO THE HOLOCAUST: 00:39:53. |

A JOURNEY INTO THE HOLOCAUST: 00:39:56. |

|

|

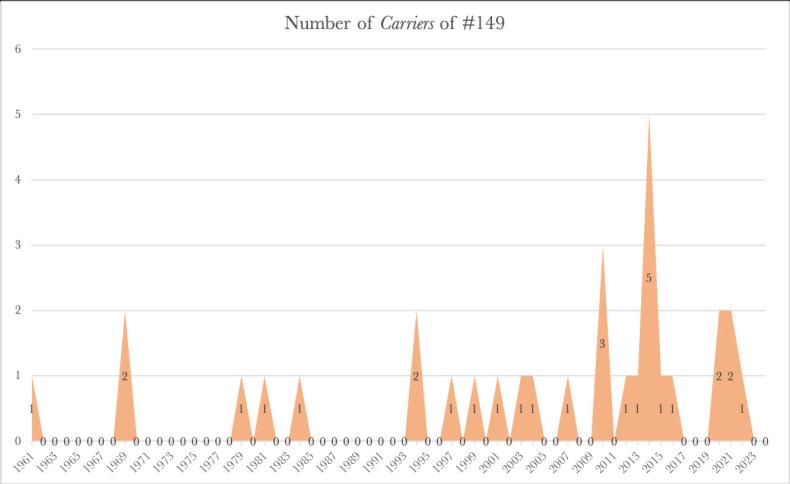

Given the difficulties in identifying films utilizing just a single shot from DEJ, the prevalence of this editing is expected to be considerably higher. Unsurprisingly, none of the five carriers that appropriate #149 in contextualization utilize this sequence. The following graph illustrates the increase of #149, which is closely connected to the rise of television (supported by Table 01).

The practice of using previously released carriers as sources also applies to shot #77, which depicts an angry woman. In the immediate context of this shot, several other shots are frequently edited together. The following table highlights these shots and indicates in which of the twelve carriers utilizing shot #77 they appear:

Table 03:

|

|

LE TEMPS DU GHETTO (1961): 00:18:32. |

AFTER AUSCHWITZ (2013): 00:10:01. |

|

|

|

|

|

ARCHAEOLOGY – S01E07 (1991): 00:04:43. |

HITLER AND STALIN – LEGACY OF HATE (1994): 00:11:40. |

|

|

|

|

|

AFTER AUSCHWITZ (2013): 00:09:53. |

HITLER AND STALIN – LEGACY OF HATE (1994): 00:11:55. |

|

|

|

|

|

THE RISE OF THE NAZI PARTY – S01E02 (2014): 00:41:05. |

GEHEIMNISSE DER WEIMARER REPUBLIK – S01E03 (2016): 00:14:16. |

|

|

|

|

|

THE RISE OF THE NAZI PARTY – S01E02 (2014): 00:41:06. |

NAZI SECRET FILES – S01E03 (2016): 00:02:02. |

GEHEIMNISSE DER WEIMARER REPUBLIK – S01E03 (2016): 00:14:11. |

HITLER'S CIRCLE OF EVIL – S01E02 (2018): 00:51:06. |

|

|

|

THE RISE OF THE NAZI PARTY – S01E02 (2016): 00:41:11. |

NAZI SECRET FILES – S01E03 (2016): 00:02:05. |

GEHEIMNISSE DER WEIMARER REPUBLIK – S01E03 (2016): 00:13:51. |

HITLER'S CIRCLE OF EVIL – S01E02 (2018): 00:51:12. |

|

|

|

GEHEIMNISSE DER WEIMARER REPUBLIK – S01E03 (2016): 001:14:10. |

HITLER'S CIRCLE OF EVIL – S01E02 (2018): 00:51:11. |

|

|

The first of these shots is from DER EWIGE JUDE: it is shot #76, which in these two carriers is edited following #77. The third shot is from the Warsaw Ghetto footage. The others are presumably from an unknown newsreel or documentary. Considering the apprearance of the fifth shot in various productions, its repeated use across different carriers is highly unlikely to be coincidental.36 This pattern suggests a deliberate choice by filmmakers to incorporate this specific imagery, possibly due to its powerful visual impact or its effectiveness in conveying a particular narrative about the period.

Contextualized Appropriations of DER EWIGE JUDE

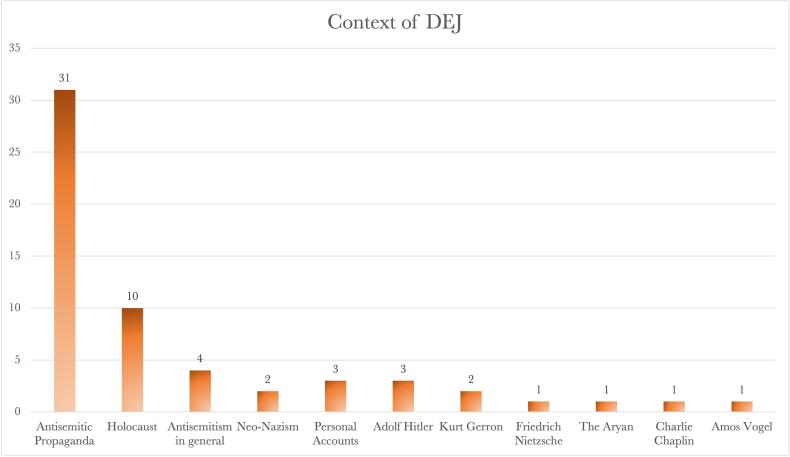

Concerning contextualized appropriation, thematic patterns are recognizable: DER EWIGE JUDE is integrated into filmic narratives in various ways, with a majority addressing antisemitic propaganda during the Nazi era or related aspects (e.g., Fritz Hippler, Joseph Goebbels, Nazi culture). Holocaust-themed carriers are equally diverse, covering the subject broadly (Holocaust in general, the Wannsee Conference) as well as focusing on specifics in France and the Netherlands.37 Other, thematically more remote productions also appropriate DEJ, for example, FILM AS A SUBVERSIVE ART: AMOS VOGEL AND CINEMA 16 (Paul Cronin, GB 2004), a documentary about the film critic and scientist Amos Vogel, who showed DEJ in New York. The following charts illustrate the various contexts of these 59 carriers. In all cases, DEJ is incorporated as an autonomous subtopic within their narratives, situating it historically and structurally:

A prime example of how footage can be arranged in both contextualized and uncontextualized ways, and the challenges this poses, is NAZI TITANIC (Oscar Chan, US/GB 2012). This documentary explores the chaotic and dramatic38 production of the anti-British disaster film TITANIC (Herbert Selpin, Werner Klingler, DE 1943). It addresses various interrelated aspects: the directors, the Nazi regime, the wartime context, TITANIC’s intentions, and Joseph Goebbels’ role in its production.

NAZI TITANIC emphasizes the importance of propaganda in the Nazis’ and Goebbels’ “goal, to give [the] German people a Nazi version history” (00:27:11–00:27:16). Particularly, the history and position of Jews were to be comprehensively rewritten, narratively preparing for their imminent eradication. To this end, Goebbels released two films in 1940 propagating a new audiovisual historiography, JUD SÜSS and DER EWIGE JUDE. DEJ is described as a “documentary” (00:27:36) in NAZI TITANIC. The appropriation begins with shots from the ‘Jewish Life’ category using the original German commentary with English subtitles. This is followed by shots from the ‘Rat Sequence’, and finally by shots from the ‘Jewish Life’ category again, including three from the kosher butchering scene. The following table lists the utilization of DEJ and how it is altered.

Table 04:

|

TC |

Shot ID |

Commentary |

|

00:27:29– |

#21 |

Voice-over |

|

00:27:32– |

#22 |

voice-over |

|

00:27:35– |

#23 (audio only) |

voice-over; original sound only in background; advertising poster utilized instead |

|

00:27:37– |

#24 (audio only) |

voice-over; original sound only in background; advertising poster utilized instead |

|

00:27:49– |

#25 (audio only) |

voice-over; original sound only in background; advertising poster utilized instead |

|

00:27:43– |

#26 |

English subtitles added |

|

00:27:46– |

#27 |

English subtitles added |

|

00:27:46– |

#76 |

English subtitles added; sound from #27 |

|

00:27:48– |

#74 |

English subtitles added sound from #27 |

|

00:27:50– |

#75 |

English subtitles added; sound from #27 |

|

00:27:52– |

#203 |

voice-over; original sound only in background; sound from #28 39 |

|

00:27:55– |

#208 |

voice-over |

|

00:27:57– |

#209 |

voice-over |

|

00:27:59– |

#210 |

voice-over |

|

00:28:04– |

#19 |

voice-over |

|

00:28:05–00:28:08 |

#20 |

voice-over |

|

… |

|

Interview; Boycott footage |

|

00:28:15–00:28:18 |

#97 |

voice-over |

|

… |

|

Boycott footage; Auschwitz Album images; image of Himmler and other SS officers; interview |

|

00:28:45– |

#206 |

voice-over; original sound only in background |

|

00:28:49–00:28:53 |

#207 |

voice-over; original sound only in background |

|

… |

|

Interview |

|

00:28:56– |

#203 (sound only) |

voice-over; original sound only in background; Boycott footage |

|

00:28:59– |

#204 (sound only) |

voice-over; original sound only in background; Boycott footage |

|

00:29:02–00:29:06 |

# 94 |

voice-over; original sound only in background |

|

… |

|

Interview |

|

00:29:09 |

#603 |

voice-over; original sound only in background |

|

00:29:10– |

#602 |

voice-over; original sound only in background |

|

00:29:12–00:29:16 |

#603 |

voice-over; original sound only in background |

In the sequence between 00:27:29 and 00:29:16, NAZI TITANIC’s commentary discusses the comparison of rats and vermin to Jews, describing it as “very potent” (00:27:59–00:28:00). The voice-over explains that the construction of concentration camps “across Germany and Poland [...] with the expressed purpose of liquidating the Jews” (00:28:19–00:28:26) necessitated an indoctrinated and brainwashed German youth. Consequently, a dehumanizing approach was (successfully) chosen for DER EWIGE JUDE.

Concurrently, various footage is interspersed with the dominant material from DEJ:

- four interview shots;

- a picture showing Himmler with other high-ranking SS officers;

- footage from two other sources (Boycott and the Auschwitz Album).

This editing implicitly creates the impression that at least the Boycott footage belongs to DER EWIGE JUDE.

While NAZI TITANIC exemplifies a contextualized appropriation of DEJ, it also demonstrates that the utilization of images and footage from other origins can potentially cause perceptual difficulties for the viewers. In this respect, DEJ is like the other iconic film materials. NAZI TITANIC illustrates that the utilization of DEJ occurs in various ways, each with its own implications and potential for misinterpretation. This case underscores the complexities involved in utilizing historical footage, even when attempting to provide proper context. It highlights the need for careful consideration of how archival material should be presented and incorporated into new narratives in order to avoid unintended conflation of sources or misrepresentations of historical events.

Indirect Appropriations of DER EWIGE JUDE

An indirect method of appropriation involves depicting DER EWIGE JUDE in a cinematic context. Two noteworthy examples are DAS RADIKAL BÖSE (Stefan Ruzowitzky, DE/AT 2013) and the fictional film WIL (Tim Mielants, BE/NL/PL 2023): In both carriers, DEJ is appropriated to illustrate how an audience is incited by its content:

DAS RADIKAL BÖSE:

- Depicts members of the Einsatzgruppen watching DEJ.

- The sequence is preceded by an inserted text: “Die Bedrohung” (the threat).

- The spectators are portrayed in two ways: as a normal cinema audience or as individuals/small groups shown in close-up, spellbound and affected by the film’s hatred.

- DEJ footage is projected onto a wall behind the viewers, clearly showing what the future mass murderers are watching.

- The film’s commentary and diary entries are used as audio supplements to support the argument that DEJ was instrumental in incitement.

WIL:

- Depicts a more general audience watching DEJ.

- Shows the spectators becoming incited, ultimately leading to the burning of the local synagogue in Antwerp.

These portrayals demonstrate the inflammatory potential of DEJ and historically situate its ideological deployment in two contexts: as an ‘educational’ medium used to indoctrinate specific groups of spectators (Einsatzgruppen, SS in general) and as a propagandistic tool employed by German occupiers to garner support from occupied populations (mostly in Western Europe). This indirect appropriation technique provides a meta-commentary on the power and danger of propaganda films. By showing the impact of DER EWIGE JUDE on fictional or historical audiences, these carriers offer a critical view on the film’s role in shaping attitudes and inciting violence during National Socialism. An approach like this allows filmmakers to engage with the content of DEJ without directly reproducing its antisemitic imagery, instead focusing on its reception and consequences. Such depictions raise important questions about the long-term effects of hate propaganda and the responsibility of media in shaping public opinion. They also serve as a warning about the potential for visual media to be used as a tool for manipulation and incitement, resonating with contemporary concerns about misinformation and radicalization through media.

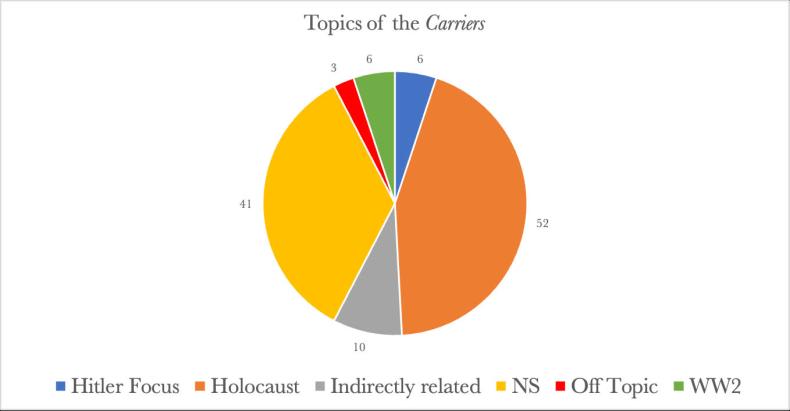

Topics of The Carriers

The great variety of utilization of the footage from DEJ is also reflected in the various topics used within the project to categorize each carrier according to its primary content. Six content-driven categories are used for this purpose, enabling macro-perspective statements about the focal points of the films. The ‘Holocaust’ topic, for example, predominantly focuses on the Holocaust, while the ‘Hitler Focus’ contains carriers primarily engaged with Hitler. ‘NS’ pertains to the political and sociological structure of the Third Reich.

The topical distribution reveals that DER EWIGE JUDE is most frequently utilized in films about the Holocaust and NS; other topics are of minimal significance within the scope of this source. This is unsurprising, given the context and nature of the material. As outlined in the non-contextualizing example of shot #149, this particularly applies to footage of the ‘Jewish Life’ category: carriers incorporating footage from DEJ address aspects such as resistance in the Warsaw Ghetto, the massacres at Babi Yar, and the annihilation of the European Jews.40

Generally, the ‘Jewish Life’ material is juxtaposed with scenes from the Warsaw Ghetto or deportations, despite the chronological inaccuracy. It is worth noting that at the time of filming (fall 1939), ghettos had not yet been established, and identification markers were not yet mandatory for the Jewish population. The utilization of this earlier footage is primarily due to its more ‘humane’ imagery compared to later documentation like the Warsaw Ghetto footage: people are not emaciated, there is no wall separating residential areas, and no corpses are visible (e. g., LIBERATION (Arnold Schwartzman, US 1994, 00:16:19–00:16:43; HIDDEN: POLAND, Allen Siegel, US 2003, 00:14:03–00:14:15). The lack of accessible footage might be another reason for the usage of material from the ‘Jewish Life’ category.

This approach to categorization and analysis provides insights into how footage of DER EWIGE JUDE is utilized in different contexts, and how its imagery is often repurposed to represent various events in the Holocaust. The juxtaposition of this earlier, less overtly traumatic footage with later events highlights the complexities of visual representation in Holocaust documentaries and the ethical considerations involved in utilizing propagandistic source material.

Modes of Utilization

In conclusion, two distinct ‘modes of utilization’ of footage from DER EWIGE JUDE can be identified. Carriers adapt the material in different ways, occasionally alienating it, thereby contributing to the dissemination of images, their contents, and meanings:

- ‘Mode of appropriation’: The origin of the material is explicitly mentioned, providing historical context. It can be altered for this purpose, for example by adding a commentator or changing the sequence of shots. However, DER EWIGE JUDE is still experienced as an autonomous film and in its historical context, empowering viewers to conduct further research. Structurally, the frequent use of this mode sets DEJ apart from other sources evaluated in the project.

- ‘Mode of usage’: Carriers use the footage illustratively, without providing additional information about its origin. In these cases, only the specific content of the shot is relevant, not the context of its origin. This mode demonstrates a hegemonic approach of the spoken word over the image. The narration or commentary in the carriers dictate the interpretation of the visuals, rather than allowing the footage to speak for itself. Instead, the auditory and visual levels are separated, with the original context of the footage (and the audio of it) often replaced or ignored – these carriers repurpose the material to fit their narratives, potentially altering its perceived meaning or significance.

This dichotomy highlights a significant gap between a sensitive preoccupation with the footage and a casual usage of shots. In one carrier, DEJ is thematized and contextualized as a propagandistic work of film history, whereas in another (or even the same), a single shot is extracted from its original context, altered, and framed as ‘authentic’ material from places like the Warsaw Ghetto, leaving the audience uninformed about its true origin. Notably, the ‘mode of usage’ correlates significantly with the growing quantity of TV programs and their increased focus on entertainment. Interestingly, both ‘modes’ emerged in the first year of the footage’s ‘rediscovery’: While AKTION J references the footage’s origin, LE TEMPS DU GHETTO silently presents it as ‘authentic’ footage from the Warsaw Ghetto. From a macro perspective, this film material is often utilized in a way that ‘normalizes’ it, placing it alongside other footage without acknowledging its specific historical context, and hence denying its inflammatory intention. Nevertheless, these shots still serve as medial cues, evoking memories and emotions associated with the Holocaust and National Socialism in general.

While this article is not a suitable forum for a moral debate, it is worth noting the problematic nature of this trend. It demonstrates a lack of sensitivity towards both DEJ and spectators of its carriers. Since 1960/61, the footage has increasingly shifted from being Holocaust evidence to becoming decontextualized material, adaptable for various purposes. Moreover, some shots (from DER EWIGE JUDE and beyond) have been used through previously released films as visual sources, thus likely objectionably perpetuating and expanding the proliferation of DEJ. In these cases, it is highly unlikely that ethical questions were raised regarding the utilization of the material. Nevertheless, there are multiple instances of appropriations aimed at properly contextualizing the footage. These treatments acknowledge DEJ for what it is – the quintessential antisemitic propaganda film.

- 1

The international versions partly use different footage, especially shots from Amsterdam. Some were filmed for this occasion, others were taken from existing films, for example, VRIJDAGAVOND (Jan Teunissen, NL 1934). VRIJDAGAVOND portrays the Jews in a likable way. The same director reissued his movie, condemning the alleged paltering of the Jews in 1941. See Stig Hornshøj-Møller, “Der ewige Jude,”Quellenkritische Analyse eines antisemitischen Propagandafilms (Göttingen: Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film, 1995), 306.

- 2

Harriet Scharnberg, Die “Judenfrage” im Bild. Der Antisemitismus in nationalsozialistischen Fotoreportagen (Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2018), 250–251.

- 3

See Florian Freund, Bertrand Perz and Karl Stuhlpfarrer, “Das Ghetto in Litzmannstadt (Łódź),” in “Unser einziger Weg ist Arbeit.”Das Ghetto in Łódź 1940-1944, ed. Hanno Loewy and Gerhard Schoenberner (Frankfurt am Main and Wien: Löcker Verlag, 1990), 17.

- 4

See Hornshøj-Møller, “Der ewige Jude,” 16–17.

- 5

See Christian Hardinghaus, Filmpropaganda für den Holocaust. Eine Studie anhand der Hetzfilme “Der ewige Jude” und “Jud Süß” (Marburg: Tectum, 2008), 33.

- 6

The topic of ‘othering’ in the cinematic context has grown significantly in recent years. In particular, more subtle forms of exclusion are often examined, and the films are thus also subjected to an ideology-critical analysis. Particularly, filmic methods of identification and exclusion are examined. E. g., Claudia Simone Dorchain and Felice Naomi Wonnenberg, eds., Contemporary Jewish Reality in Germany and its Reflection in Film (Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2013); Harry M. Benshoff and Sean Griffin, America on Film: Representing Race, Class, Gender, and Sexuality at the Movies (Hoboken and Chichester: Wiley, 3rd ed., 2021); Julia Khrebtan-Hörhager and Roberto Avant-Mier, “Despicable Others: Animated Othering as Equipment for Living in the Era of Trump,” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 46, no. 5 (2017): 441–462; Martin Berny, “The Hollywood Indian Stereotype: The Cinematic Othering and Assimilation of Native Americans at the Turn of the 20th Century,” in Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 10 (2020): 1-26; Stephen Bennett, “The Othering of Palestinians in Film: Munich (2006) and Waltz with Bashir (2009),” Networking Knowledge: Journal of the MeCCSA Postgraduate Network 7, no. 3 (2014): 69-81; Nadia Adelia, “Stereotyping and Othering of Non-White Characters in ‘Harry Potter’ Movies,” Kata Kita 7, no. 1 (2019): 14-21.

- 7

Ernst Jerosch, “Der ewige Jude,” Der Film, November 30, 1940.

- 8

Joan Clinefelter, “A Cinematic Construction of Anti-Semitism: The Documentary Der ewige Jude,” in Cultural History through National Socialist Lens. On the Cinema of the Third Reich, ed. Robert C. Reimer (Rochester and Woodbridge: Camden House, 2000), 140.

- 9

See Régine Mihal Friedman and Gertrud Koch, “Juden-Ratten – Von der rassistischen Metonymie zur tierischen Metapher in Fritz Hipplers Film Der ewige Jude,” Frauen und Film, no. 47 (1989): 26–27.

- 10

The process begins with the shochet – a trained and certified Jewish butcher – reciting a blessing, acknowledging the sanctity of the act. The shochet then quickly and precisely cuts the animal’s throat, severing the major blood vessels. This method is intended to result in a rapid loss of blood, which is a critical component of kosher butchering because according to Jewish dietary laws, the consumption of blood is prohibited.

- 11

Claire Aslangul, “Faire peur, faire “vrai”: Der ewige Jude. Objectifs, procédés et paradoxes d’un “documentaire” antisemite,” ILCEA. Revue de l’Institut des langues et cultures d’Europe, Amérique, Afrique, Asie et Australie, no. 23 (2015): 22.

- 12

Claude Singer, “Comment le cinéma nazi falsifiait l’image des ghettos juifs (1939-1944),” Diasporas. Histoire et sociétés, no. 4 (2004): 55–69.

- 13

See Stig Hornshøj-Møller and David Culbert, “‘Der ewige Jude’ (1940): Joseph Goebbels’ unequaled monument to anti-Semitism,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 12, no. 1 (2006): 51.

- 14

See Wolfgang Benz, “Der ewige Jude”. Metaphern und Methoden nationalsozialistischer Propaganda (Berlin: Metropol, 2nd ed., 2010), 57.

- 15

See ibid., 70.

- 16

See ibid., 130–134.

- 17

See Rosemarie Burgstaller, Inszenierung des Hasses. Feindbildausstellungen im Nationalsozialismus (Frankfurt am Main and New York: Campus, 2022), 332–334.

- 18

See Hanno Loewy, “Der ewige Jude. Zur Ikonografie antisemitischer Bildpropaganda im Nationalsozialismus,” in Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. 1900 bis 1949, ed. Gerhard Paul (Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009), 544.

- 19

For example, using pictures combined with texts, audiovisual techniques like short videos, and general methods of modern product advertisement (incisive phrases, emotionalization, creating a desire). See Hans-Ulrich Thamer, “Geschichte und Propaganda. Kulturhistorische Ausstellungen in der NS-Zeit,” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 24, no. 3 (1998): 349.

- 20

See Burgstaller, Inszenierung des Hasses, 280.

- 21

See ibid., 274.

- 22

Hans Diebow, Der ewige Jude (München and Berlin: Franz-Eher-Verlag, 1937), 2.

- 23

See ibid., 3.

- 24

See Benz, Der ewige Jude, 68.

- 25

See Stefan Mannes, Antisemitismus im nationalsozialistischen Film. Jud Süß und Der ewige Jude (Köln: ZBE Sachbuch, 1999), 52–53.

- 26

See Diebow, Der ewige Jude, 126–128.

- 27

Ibid., 120.

- 28

See Michael Wildt, Zerborstene Zeit. Deutsche Geschichte. 1918 bis 1945 (München: C. H. Beck, 2022), 149.

- 29

See Clinefelter, “A Cinematic Construction of Anti-Semitism,” 144.

- 30

See Burgstaller, Inszenierung des Hasses, 255.

- 31

Obviously, the Reichsfilmarchiv itself hadn’t produced this footage; the actual place of origin, however, remains unknown. Hornshøj-Møller assigns the material to the Reichfilmarchiv, as it comes from the collection of idealized shots, which was created to make exemplary film material easily accessible for propaganda purposes. See Hornshøj-Møller, “Der ewige Jude,” 29.

- 32

Hornshøj-Møller counts 712 shots. The difference is black shots. See Hornshøj-Møller, “Der ewige Jude,” 187.

- 33

An examination of the footage posted on the German Federal Archives’ website (Link) reveals that all but one shot is appropriated from KAMPF DEN RATTEN. Hornshøj-Møller, on the other hand, referencing a 1981 interview with Hippler in Kirche und Film, writes that five shots were filmed by Erich Stoll as a supplement. However, Hornshøj-Møller considered the film lost in 1995. As its footage remains incomplete, it is also quite possible that the disputed shot comes from KAMPF DEN RATTEN. See Hornshøj-Møller, “Der ewige Jude,” 215.

- 34

For example, TRIUMPH DES WILLENS, has more than 1,200 known Carriers.

- 35

None of the twelve carriers appropriating ‘Trick Cards’ or the ‘Rat Sequence’ without ‘Jewish Life’ disguises the origin of the footage.

- 36

The strongly divergent TCs indicate they are not the same episodes with different titles. Instead, they were produced by three companies that either recycled their sequence or discovered it in other carriers.

- 37

The respective country version is then used for the country-specific focus.

- 38

The first director, Selpin, was denunciated after complaining about the war, arrested by the Gestapo, and found dead in his cell. It is uncertain if his death was suicide or homicide.

- 39

Interestingly, the DEJ commentary of shot #28 quotes Richard Wagner: during the introduction of NAZI TITANIC (00:03:43–00:03:57), a sequence from DEJ is used; footage which is not part of the three categories but, for example, was produced for TRIUMPH DES WILLENS. These shots are accompanied by Wagner’s Ride of the Valkyries.

- 40

E. g. HOLOKAUST: S01E05 (DE 2000), THE UNSEEN HOLOCAUST (GB 2014), THE RISE OF THE NAZI PARTY – S01E07 (GB 2014).

Aslangul, Claire. “Faire peur, faire “vrai”: Der ewige Jude. Objectifs, procédés et paradoxes d’un “documentaire” antisemite.” ILCEA. Revue de l’Institut des langues et cultures d’Europe, Amérique, Afrique, Asie et Australie, no. 23 (2015): 1–30.

Benz, Wolfgang. “Der ewige Jude.” Metaphern und Methoden nationalsozialistischer Propaganda. Berlin: Metropol, 2nd edition, 2010.

Burgstaller, Rosemarie. Inszenierung des Hasses. Feindbildausstellungen im Nationalsozialismus. Frankfurt am Main and New York: Campus, 2022.

Clinefelter, Joan. “A Cinematic Construction of Anti-Semitism: The Documentary Der ewige Jude.” In Cultural History through National Socialist Lens. On the Cinema of the Third Reich, edited by Robert C. Reimer, 133–154. Rochester and Woodbridge: Camden House, 2000.

Diebow, Hans. Der ewige Jude. München and Berlin: Franz-Eher-Verlag, 1937.

Freund, Florian, Bertrand Perz and Karl Stuhlpfarrer. “Das Ghetto in Litzmannstadt (Łódź).” In “Unser einziger Weg ist Arbeit.” Das Ghetto in Łódź 1940-1944, edited by Hanno Loewy and Gerhard Schoenberner, 17–31. Frankfurt am Main and Wien: Löcker Verlag, 1990.

Friedman, Régine Mihal and Koch, Gertrud. “Juden-Ratten – Von der rassistischen Metonymie zur tierischen Metapher in Fritz Hipplers Film Der ewige Jude.” Frauen und Film, no. 47 (1989): 24–35.

Hardinghaus, Christian. Filmpropaganda für den Holocaust. Eine Studie anhand der Hetzfilme “Der ewige Jude” und “Jud Süß.” Marburg: Tectum, 2008.

Hornshøj-Møller, Stig. “Der ewige Jude.” Quellenkritische Analyse eines antisemitischen Propagandafilms. Göttingen: Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film, 1995.

Hornshøj-Møller, Stig and David Culbert. “‘Der ewige Jude’ (1940): Joseph Goebbels’ unequaled monument to anti-Semitism.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 12, no. 1 (2006): 41–67.

Jerosch, Ernst. “Der ewige Jude.” Der Film, November 30, 1940.

Loewy, Hanno. “Der ewige Jude. Zur Ikonografie antisemitischer Bildpropaganda im Nationalsozialismus.” In Das Jahrhundert der Bilder. 1900 bis 1949, edited by Gerhard Paul, 542–549. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 2009.

Mannes, Stefan. Antisemitismus im nationalsozialistischen Film. Jud Süß und Der ewige Jude. Köln: ZBE Sachbuch, 1999.

Scharnberg, Harriet. Die “Judenfrage” im Bild. Der Antisemitismus in nationalsozialistischen Fotoreportagen. Hamburg: Hamburger Edition, 2018.

Singer, Claude. “Comment le cinéma nazi falsifiait l’image des ghettos juifs (1939-1944).” Diasporas. Histoire et sociétés, no. 4 (2004): 55–69.

Thamer, Hans-Ulrich. “Geschichte und Propaganda. Kulturhistorische Ausstellungen in der NS-Zeit.” Geschichte und Gesellschaft 24, no. 3 (1998): 349–381.

Wildt, Michael. Zerborstene Zeit. Deutsche Geschichte. 1918 bis 1945. München: C. H. Beck, 2022.