Screening Propaganda

Film Documents of Contemporary History and Educational Practice, circa 1970

Table of Contents

Screening Propaganda

In Defense of Culture

The Raw Materials of Celluloid Film

Wholeness and Nature

The Austrian Province as Subject and Space of Action in Educational Film Practices

The Development of Educational Cinema for Schools in the Soviet Union in the 1930s

Educational Film in East Germany (GDR) in 1950–1990 in Perspective of the “Grammar of Schooling”

No Instructions, Just Some Advice

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Sattelmacher, Anja. “Screening Propaganda: Film Documents of Contemporary History and Educational Practice, circa 1970.” Research in Film and History 5 (2023): 1–33. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/22727.

Introduction

Between 1952 and its closure in 2010, the Institute for the Scientific Film (Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film [IWF]) in Göttingen produced scientific and educational films for national and international distribution. Most of these films belonged to the fields of zoology, ethology, ethnology, agriculture, and technology.1 They were conceived for research as well as for educational purposes for teachers at universities. Among these vast collections, a film series called Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte (Film Documents of Contemporary History) contained reedited historical footage from different time periods as well as film portraits of selected personalities from the postwar era. They were all classified under “G” for “Geschichte” (history). The G-series was rather exceptional because the IWF itself restricted its use to the extent that the films were rarely shown to an audience outside the academic context. The IWF’s director, Gotthard Wolf (1910–1995), admitted that the institute had initially been reluctant to produce films on historical topics since most of its films focused on the hard sciences. Ultimately, the idea of using film as a way to document important historical personalities for future generations gave rise to a preoccupation with the field of history.2

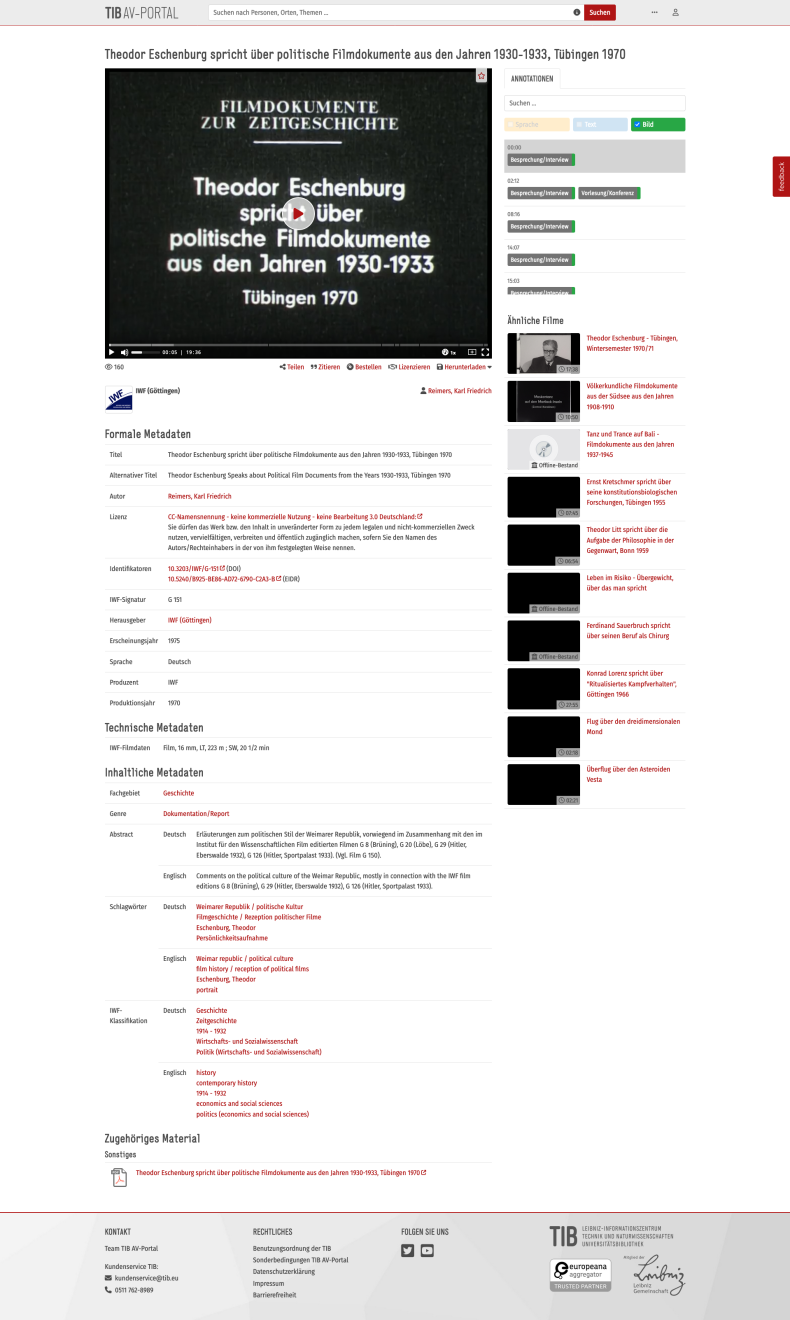

In December 1970, a group of students at the University of Tübingen (Germany) convened in a small seminar room, where their professor, the political scientist Theodor Eschenburg (1904–1999), screened and lectured about several filmed speeches delivered between 1930 and 1933 by politicians from the Social Democratic Party and members of the National Socialist Party, such as Joseph Goebbels and Adolf Hitler. Karl Friedrich Reimers, a German historian employed by the IWF in Göttingen, filmed the seminar along with his team. The resulting 20-minute black-and-white film is entitled THEODOR ESCHENBURG SPRICHT ÜBER POLITISCHE FILMDOKUMENTE AUS DEN JAHREN 1930–1933 / THEODOR ESCHENBURG DISCUSSES POLITICAL FILM DOCUMENTS FROM THE YEARS 1930–1933. Today, it can be accessed online under the IWF call number G 151 via the AV-Portal of the Leibniz Information Centre for Science and Technology University Library (TIB).3 However, the 16mm film (now digitized) does not contain the actual footage that was shown and discussed during the lecture. In the 1970s, these film reels could be ordered together with Eschenburg’s filmed lecture. Nevertheless, today this original footage is not accessible because the TIB has not yet digitized these films for reasons discussed below. In the 1970s, viewers had access to both the analogue 16mm film print along with the historical footage. Since circa 2010, a new generation of viewers can click on a link and easily access the lecture but not the discussed film sequences. Only pictures in an accompanying publication provide visual evidence of the historical speeches.

Although the films are today housed by the TIB AV-Portal and the digitization of other IWF films has long been initiated, the question of how to productively show digitized speeches by former leading figures of National Socialism has yet to be resolved. This essay will elucidate the multilayered history of the film G 151 – THEODOR ESCHENBURG SPRICHT as an example of an early attempt to establish film criticism as a form of academic source criticism among historians on the one hand, and to deliver a reflection on how the propaganda and despotism of National Socialism was looked upon during the early years of the Federal Republic of Germany. On the other hand, I will show how we look upon film as a historic source today and what new challenges come along with the digitization and digital storage of educational films in archives.

Films for Historical and Political Education

In a 1968 conference at the IWF, Günter Moltmann, a German historian and colleague of Reimers, asked if “documentary film strips and sound recordings” could prove useful for contemporary history.4 While numerous book publications had illuminated recent historical events – namely the period of National Socialism – until 1970, film and audio records were rarely used for historical analysis. Moltmann explicitly referred to audiovisual material not as a didactic tool but as a means of research and claimed that historical footage provided a “milieu description” (Milieuschilderung) of historical events while recordings of personalities from the Weimar Republic or the Nazi regime could be used to analyze facial expressions, gesticulations, and rhetoric. “Where sentences do not say much, the manner in which they are spoken can provide information about the speaker.”5 Thus, a filmic record of a politician delivering a speech might well serve for future biographical studies, he argued. In addition to these three purposes – background description, rhetoric, and biographical studies – Moltmann identified a fourth reason audiovisual material should become part of the historian’s repertoire. The visual propaganda that was so essential to Nazism could help elucidate the very nature of propaganda itself. Like any other historical source, film documents, such as excerpts from newsreels (Wochenschauen), should undergo rigorous source criticism by contemporary historians. Moltmann’s fellow historians – for example, the economic and social historian Wilhelm Treue – agreed.6 Given his close ties to historians working at the IWF, Treue emphasized the importance of systematically analyzing film as a historical source in order to expose the propagandistic elements to future historians.7 Both Treue and later Moltmann argued in favor of the establishment of an “intellectual history of film,” implying that film itself had a genuine value and function for the study of history.8 Notably, students of history should be made accustomed to the use of film for historical analysis.

Among the IWF’s vast collection of approximately 11,500 films, G 151 is an extraordinary document. Its value as a historical source is twofold: First, as intended by Reimers, it shows Eschenburg’s interpretation of National Socialist propaganda to future historians and political scientists. The second point is more subtle: Over the fifty years since the film was first published, Eschenburg himself has become a controversial figure due to his own involvement with the NS-system. From 2011 onwards, the historian Rainer Eisfeld revealed that Eschenburg actively participated in expropriating Jewish merchants in Austria.9 Hence, the film – now available in open access online – has become a historical document in its own right. It illustrates how the 1930s were looked upon in the German Federal Republic around 1970 and how the image of Eschenburg has changed – from the distinguished postwar educator to an active member and beneficiary of nazism.

G 151 was released in 1970 amid massive student protests against the persistence of National Socialism within postwar German society.10 This film sheds light on the different layers of afterlife and reuse of historical film documents, depending on their actual historical context. During the nineteen minutes of this film, we see Eschenburg sitting in a small seminar room. Throughout the lecture, a spotlight focuses on him in order to achieve optimum illumination of his face. Next to him – visible only in a few shots – sits Reimers himself. Before them sit the eight or so students attending the lecture, some of them smoking, though they are only shown in a few sequences. Three cameras capture the seminar from different perspectives: two record Eschenburg from the front and the side, while the last shows the students through close-ups.

Eschenburg begins his lecture by examining three filmed public speeches by German politicians during the transition phase between the end of the Weimar Republic and the beginning of the so-called Third Reich in 1933. The provenance of all discussed footage was newsreel material. The IWF collected and reedited numerous newsreel films that showed recorded speeches and propaganda from politicians of the Weimar Republic and the reign of National Socialism. The first speech discussed by Eschenburg is by Heinrich Brüning, a politician of the German Center Party, who briefly served as chancellor of the Weimar Republic between 1930 and 1932 and is titled G 8 BRÜNING AUS EINER REDE ZU DEN REICHSTAGSWAHLEN VOM 14. SEPTEMBER 1930. The second filmed speech, by Paul Löbe, former president of the German Reichstag from 1925 to 1932, is catalogued at the IWF as G 20 PAUL LÖBE SPRICHT ÜBER DRINGENDE AUFGABEN DES DEUTSCHEN REICHSTAGES. Finally, Eschenburg discusses Adolf Hitler’s 1932 public speech in Eberswalde, the IWF edition titled G 29 HITLER IN EBERSWALDE 27. JULI 1932. All three films were shown during the lecture but not included in the final filmic record. There are only hints of the screening – the sound of the film reel turning or Eschenburg pointing to the projection offscreen. In a discussion with students at the end of the film, he shares his experience of having witnessed Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels’ introduction to Hitler’s notorious speech at the Sports Palace in Berlin – the film document edited at the IWF as G 126 HITLERS AUFRUF AN DAS DEUTSCHE VOLK VOM 10. FEBRUAR 1933.11 Sitting back in his chair, Eschenburg puts away his smoking pipe and says,

“Yes, I have seen all three of them. I have spoken to two of them, Brüning and Löbe, several times. Well, I am quite astonished – that was thirty-eight years ago – how aptly the film portrays these three figures.”12 (’00:16–00:37) When Eschenburg says “all three,” he means Brüning, Löbe, and Hitler. He then analyzes the appearance of Chancellor Brüning in the film, reading a script before the Reich Chancellery, and characterizes Brüning’s habitus as “inanimate,” even imitating his posture and gestures for the lecture. It should be noted that sound was a fairly new technology to film in the 1930s and hence the speakers were rather inexperienced with the recording of their own voice. It was around 1933 that sound began to explicitly be used as a tool for propaganda by Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels.13 Eschenburg then continues, further commenting on Brüning’s attire: “There was something quite old-fashioned and teacherly about him. The corner collar (“Eckkragen”) was already unfashionable, as well as the black tie” (‘1:39–1:52). He concludes that Brüning was wholly unappealing: he was boring to listen to and lacked charisma. This was underlined by the fact that there was no audience in the footage – only a rostrum provided for the speaker.

In the next camera setting (‘2:04), one of the IWF cameras shows the seminar room for the first time as well as Eschenburg’s audience. For a brief moment, the viewer gets to see Reimers, sitting next to the professor, before the camera pivots to the room filled with exclusively male students, who are listening but appear to be bored. None of them take notes: one is unplugging his ears, while another fidgets with his pencil. Many keep checking their watches.

One sequence even overlaps audio of Eschenburg describing Brüning’s stiffness and dullness while focusing on one of the student’s watches (‘2:48). His neighbor must have been smoking, evidenced by a cloud of smoke hovering above his hand. Eschenburg is presenting himself here in a double role. On the one hand, he is a witness of Hitler and his collaborators. He confesses that he took part in the speeches but claims that he was forced to attend and had not really believed in what was being said. On the other hand, in this situation he acts as a teacher of political sciences, trying to reveal to his students how political mise-en-scène generally works and highlighting the elements of demagogy in the shown footage. As a teacher, he neglects the fact that the speeches, especially those of Goebbels and Hitler, are not just political propaganda but possess specific demagogic characteristics. In the scenes of the lecture that follow it becomes obvious that the two roles Eschenburg is trying to combine quickly fall apart. At minute 7’44 he states:

I have heard Hitler three times: twice in 1932 and once in 1933. […] Hitler’s speeches have never made an impression on me. It was downright embarrassing for me to sit in the Sports Palace in the middle of a frenzied crowd – as a lonely island, so to speak. I admit that I clapped along; otherwise, I would have been torn to shreds. But I went there with someone who was not [even] a National Socialist and was completely enraptured by this speech.

While supposedly unmasking the mechanisms of propaganda in these films, Eschenburg himself tries to mask, manipulate, and relativize his own participation in National Socialism. He tries to downplay the fact that he attended the speech by referring vaguely to “others” who also attended and how they were fully convinced by the content of the speech. Furthermore, it also seems that the students fail to question Eschenburg’s description of his own participation in these scenes, even when it is obvious that he is attempting to downplay his own complicity. This undermined what Reimers and his colleagues envisioned by filming this lecture for future students. The filmed lecture was meant to exemplify the way in which future historians talk and think about National Socialist propaganda. Moltmann was convinced that film and sound documents were even more apt to analyze the demagogic methods of dictatorship than written documents. With their help, one could better understand the mechanisms of enforced political conformity [“Gleichschaltung”].14 At the same time, Moltmann explicitly stated that a historian, or in Eschenburg’s case, a political scientist working with film should not become a subsequent witness of what he is seeing; rather, his task was “detached analysis.”15 Film, as it was an especially suggestive source, needed to be handled with even more sobriety than other sources. Therefore, Moltmann claimed: “When evaluating film and audio material, the researcher himself can become an unreliable witness. A fair amount of self-discipline, self-control and self-distancing is therefore necessary.”16

However, neither Eschenburg himself nor his students engage with such a sober analysis, so that Eschenburg actually becomes the aforementioned “unreliable witness.” In G 151, there is only limited interaction between Eschenburg and his students. Following the professor’s analysis of Hitler’s speech, the students ask a few questions, which Eschenburg answers. For example, at minute 16:09, one of the students asks if audience members voluntarily attended the speech or if they had been selected beforehand. The professor says: “Voluntary audience – no, I mean, it was kind of a compulsory exercise for National Socialists to go there; it couldn’t be controlled, could it? A speech by Hitler at the Sports Palace is always a sensation, isn’t it? And it’s always crowded – especially now, fourteen days after the inauguration of the government.” One student asks why, even after his election, Hitler still did not openly say what he was planning to do: “He talks in general terms about the greatness of the people, but how he is going to tackle the whole thing?” Eschenburg answers that this was a speech to win the upcoming elections. Hitler therefore remains as vague as possible.

The structure of this lecture quite closely relates to ideas of education through film that are rooted in the 1920s and gained new ground among teachers and filmmakers after the Second World War – often under the keyword School Film Movement [Schulfilmbewegung].17 Typically, a teacher or educator would present films to students, comment on them, and then a discussion in the seminar room would follow.18 Especially in the late 1960s and early 1970s, there was a strong urge to reform the German educational system; thus the education of future teachers was crucial. But even more importantly, since images and audiovisual materials were becoming increasingly omnipresent in daily life, educators called for the development of a proper media pedagogy to be implemented in schools. Authors like the filmmaker Horst Ruprecht, who published a book on film education in 1970, were aware of the manipulative potential of filmic images. Especially through the use of montage, film could distort, omit, or even lie about facts. At the same time, Ruprecht considered film a very apt medium to depict the “truth,”19 so that audiovisual media should be considered more seriously, especially for the teaching of history. As late as 1988, the historian Peter Meyers stated that mass media, particularly film, were still not taken seriously enough by historians and history teachers.20 In order to establish film as a didactic tool within history, he developed a systematic approach to the use of film within history didactics. This approach was to carefully protocol each sequence of a film in order to make it analyzable and objectifiable. What seems obvious to contemporary readers was not so to viewers from the 1970s, when the discipline of film analysis was evolving within the field of semiotics and media theory.21

In 1970, Reimers suggested a concrete path of how to systematically analyze a propaganda film within the context of teaching history at the university level.22 As an example of how to critically discuss a film as a historical source, he chose the film G 126 HITLER’S AUFRUF AN DAS DEUTSCHE VOLK VOM 10. FEBRUAR 1933, which Eschenburg discussed in G 151 THEODOR ESCHENBURG SPRICHT. Reimers proposed conducting primary source research to determine which film archive would contain which version of the film. In his view, this film document had specific characteristics that made it valuable for analyzing propaganda material. First, it showed the combination of visual and acoustic “suggestive procedures” that revealed the demagogic character of Hitler and his surroundings.23 Second, it enabled comparisons of the habitus behavior of Hitler and Goebbels, thus constructing portraits that would subsequently be demasked by how the film was shown. Third, using film as a tool for historical research must always include the study of other source material, such as newspaper articles or radio broadcasts.24 Reimers thus suggested developing a specific system for the analysis of film propaganda: It was important to first create a shot and sequence protocol for each film so that certain standards were applied to each film. The length of all sequences should be stated, ideally in meters and decimeters, facilitating the creation of an index of each film. It was also important to meticulously note the setting size, camera position, and camera movement of each sequence. Finally, music and sound within the film should also be noted.25

To a certain degree, G 151 was meant to be a model film for how to conduct a history lecture on propaganda and teach students how to analyze and deconstruct it. However, during the film it becomes increasingly questionable whether the lecturer lacks the requisite distance to the objects discussed. While Eschenburg describes the speeches by Brüning and Löbe at the beginning of his lecture dispassionately and somewhat dismissively, as the film progresses, he becomes increasingly emotional. Toward the end of the lecture (’18:09–’19:22), as Goebbels delivers his introduction (G 126), Eschenburg finally emerges from his shell, even imitating the posture and tone of Goebbels. He raises his voice and lifts his arm, pointing to something offscreen.

May I say one more thing, ladies and gentlemen: You see – there you see the skillful, yet infamous master of ceremonies! Germany has never again had such an emcee nor did it ever have one before. This introduction by Goebbels with its discussion of the press, Marxism, Judaism, and above all this suggestive speech, isn't it, this ‘prelude’ to Hitler’s entrance: that is already skillful, you know. You know, don’t you – it makes you want to throw up, doesn’t it – but this is a performance, and I am firmly convinced that this performance was most carefully prepared, and perhaps even prepared in front of the mirror, wasn’t it? It was all done ‘by suggestion.’ Many hands may have been involved; then it was memorized. Even today, after thirty-eight years or thirty-seven years, I have to say that for me the suggestion of the prelude, how Hitler was announced there, how the masses were called together – isn’t it true? – it’s a rare rhetorical masterpiece.

This scene marks the end of the film with no further discussion or contextualization. Although these filmed speeches were explicitly intended to serve as sources within the lecture to illustrate mechanisms of political propaganda, Eschenburg employs a vocabulary that is hardly detached from the original source. On the contrary, his description of Goebbels is full of admiration (“there you see the skillful, yet infamous master of ceremonies,” “a rhetorical masterpiece”) and his own attempt to create some distance (“it makes you want to throw up”) does not convincingly mark his personal distance. The further Eschenburg delves into the description of Goebbels, the more it seems he is drawn into the vortex of demagogy. His voice begins to tremble and his body, stiff up to this point, sways back and forth. Ultimately, Eschenburg admits that Goebbels’s speech had made a big impression on him. This last scene of the film reveals all the possible risks that screening propaganda can evoke in front of an audience. It does not just reveal itself as Reimers had hoped but rather shows how demagogic speech can provoke a re-living of the event. However, this effect only counted for Eschenburg himself who was re-living the scene of the speeches another time. The students however, seem totally unaffected by this reenactment. They show no signs of either sympathy or rejection.

The Unlikeliness of the Screening Event

G 151 was finally released in 1975 as a film for use in historical research and university teaching. It was published as a 16mm black-and-white film with a length of 233 meters and duration of twenty minutes at twenty-four images per second. While Reimers had long worked toward a systematic approach for the analysis and deconstruction of political speeches and propaganda through film, the result of this filmed lecture bears the omission of the propaganda itself. While Eschenburg hints at the (for the spectator invisible) rattling projector in the background several times, the films themselves have not been included in the 16mm version of the filmed lecture. The reasons for the absence of the projections in the filmed lecture are not mentioned in the sources but must have been for mostly practical and technical reasons. Filming the projection of historical footage would have meant a great loss of quality. It remains unclear why Reimers decided against cutting parts of the footage into the filmed lecture so the viewer of the 1970s would have the references right in the film. It possibly did not conform to the general filming policy of the IWF that tried to avoid narrative cuts at all costs. Wolf even used the word “deception” when mentioning common film practices, such as sound, color, montage, and titling.26

Anyone wanting to use the film in (university) history teaching had to borrow both the print of G 151 as well as the discussed films.27 With this constellation, a screening would have involved a constant change of film reels unless there were at least two projectors in the room. This would have been unlikely, since just one projector often caused technical problems not easy to resolve. Loading a film into a projector and pushing the right buttons to start it often seemed too much of a challenge for technically untrained teaching personnel.28 Or, a second possibility would have been to watch the speeches in sequence followed by the filmed lecture – which would have afforded less changes of reels and would have been easier to manage. In the absence of practical reports of how the projection was handled in practice, these thoughts remain speculative.

In the postwar era, the use of 16mm projectors in class was a rather rare event. Despite the increasing availability of projection technology in teaching institutions, the apparatus still faced resistance among teachers and never became a regular teaching aid within schools.29 And in the 1980s, the educational 16mm film began being replaced by video technology. Only about fifty years after its first release was G 151 made available online.

Published under a Creative Commons license, it is freely accessible; however, the speeches discussed in the film have not been digitized and are inaccessible to prospective viewers. So far, only a visit to the archive rooms in Hannover allows the viewing of the 16mm original material on the cutting table.

Thus, G 151 shows a screening of propaganda footage that has been omitted from the documentary. However, the footage itself – collected by Reimers and his predecessor Fritz Terveen from around 1957 – formed part of the IWF film collection as reedited and reworked film editions.30 There is then a temporal layering in Eschenburg’s lecture: He discusses speeches that were shot in the 1930s, while actually showing and referring to the reedited versions made by Reimers and Terveen between 1957 and 1971.31 These editions were lent out to history students along with accompanying publications, authored by either Terveen or Reimers, providing detailed information about the source of the filmic material, existing versions and which had been used for the new edition, and a film description that primarily reproduced the spoken text. Even though there is a lack of concrete data about the number of borrowers, information written on the 16mm film boxes convey that particularly the speeches by Löbe and Brüning were not frequently watched. As for the film G 126 AUS EINER WAHLREDE HITLERS IN EBERSWALDE the situation was different: this film was often used by educational institutions, such as universities. This fact can be deduced from the number of prints made by the printing laboratories. On the box of the film G 126 in the IWF-Archive in Hannover the number “7” indicates that this existing print was the seventh one made for borrowing.32

In the case of Brüning’s speech, Terveen added a statistic about the distribution of parliamentary seats in 1930 as well as a list of scientific publications. While the speech by Löbe was only about two and a half minutes long, Hitler’s Eberswalde speech was about thirteen minutes long. Accordingly, Terveen’s publication on the latter film is twice as long as those of the two others. The text is structured into some historical notes on the NSDAP’s totalitarian publishing policies before and after Hitler’s 1933 victory, critical thoughts on the referenced film document, and information about the provenance of the material and the existing film version stored in the IWF archive. As in most of Terveen’s other publications, this one included a lengthy image description and transcription of the speech. Eschenburg fails to mention any of this meticulously constructed background information in his lecture, instead highlighting his personal recollections of this event. Publications on film education from that time suggested that film as a teaching medium should always be analyzed, accompanied, and supplemented by additional media, such as slides, text, sound, or image material, as well as a guided discussion. If G 151 was to be used as a didactic film, it is more likely that the texts from the additional publications would have been used as references, rather than the 16mm prints of each propaganda speech, for financial reasons. It was much less expensive to order printed copies of the accompanying texts than to order the 16mm film prints and their accompanying apparatuses. As Ruprecht stated, a combination of different media in class was always preferable for the learning effect as a whole.33 The study mentioned from 1988 by Peter Meyers about the use of films in history classes revealed that those containing historical propaganda with tendentious and suggestive elements like Hitler’s speech were more closely and effectively remembered than other film documents, such as the speeches by Brüning or Löbe.34

History in Hindsight

From the time of the production of G 151 ESCHENBURG SPRICHT until about 2011, Eschenburg was perceived as the “doyen” of German political science: the “teacher of democracy.”35 Born in 1904, his life spanned several wars and revolutions. Initially, before the Second World War, he was a politician of the German State Party (Deutsche Staatspartei) and the German Popular Party (Deutsche Volkspartei, DVP) – both rather liberal parties – and a publicist. During the era of National Socialism, he served as head of a cartel association for haberdashery, a fact that became important when his activities during 1933–1945 were finally revealed. After the Second World War, he founded the Institute of Political Science in Tübingen, contributing regularly to the renowned weekly newspaper Die Zeit from 1954 to 1992. With his many publications, his work as a publicist, and his political involvement, he became one of the leading personalities shaping political education in postwar West Germany. Over the course of his academic career, he earned all of the prestigious German academic prizes including the Ordre de Mérite,36 while keeping quiet about his (allegedly short-term) SS membership as well as his own prior attitude toward National Socialism. In 2011, the historian Rainer Eisfeld published an article that would mark the beginning of a long-lasting debate about Eschenburg’s political and academic heritage, since it became clear that he had consciously masked parts of his own past during the years 1933–1945.37

The correspondence between Eschenburg and Reimers in preparation for the film shoot reveals that the professor was reluctant to have an open discussion with students about the projected films.38 In fact, he feared that the students might even disrupt the filming, given that the universities were in the throes of a “revolution” (the fact that he always enclosed the word in quotation marks already indicates a dismissive attitude). He was referring, of course, to the student protests that took place at nearly all universities in Germany (and well beyond) as part of the 1968 movements, in which the younger generations attempted to confront their parents about their activities between 1933 and 1945 while breaking the silence of those fathers who had gone to war.39 Clearly, Eschenburg had much to lose here. In one letter to Reimers he states: “Even during the recording, and even before it begins, severe disruptions may occur. Either the recording is made impossible, or it is so disrupted that it is worthless. I cannot tell you whether your project can be realized in the next semester. I would like to warn you that students who question everything – and not least their professors – could be very skeptical, even hostile, about such an admission.”40

For this reason, Eschenburg chose for the lecture to take place in a small seminar room rather than a large auditorium. The additional advantage to this was that, in fact, very few students had even shown interest in attending the lecture. Over the semester, the number of students attending his class had increasingly diminished, and as summer approached, only a small number were even left to appear in the film: Eschenburg blamed the poor attendance on the summer weather and assumed students were going to the pool instead of attending his class.41

When he finally agreed to allow Reimers and his team to film his lecture, Eschenburg tried to avoid all possible “explosions” as he called them. Consequently, he attempted to retain control over the discussions taking place in the seminar. In fact, during the discussion prior to the filming, there were indeed many questions, especially regarding Eschenburg’s own attendance at Hitler’s speech in Eberswalde.42 Notably, Eschenburg did not allow Reimers to film this discussion, despite the fact that it would have been normal practice at the IWF to do so.

With this knowledge in mind, it now seems obvious why Eschenburg was downplaying and relativizing his own participation in the speech: He did have good reason to fear scrutiny. As it was gradually revealed, his role was more active than previously assumed. He was indeed a member of the National Socialist Party and part of the SS from 1933 on. After 1938, he participated in the looting of Jewish possessions and the so-called Arisierung (Aryanization) of Austrian Jewish businesses in Vienna, notably that of the two zipper manufacturers, Alfred Auerhahn and Max Blaskopf. He was also responsible for the expropriation of a plastic factory owned by Wilhelm Fischbein.43 After the war, he claimed that, like others, he had opposed the regime but had no choice but to align himself with the National Socialists in order to guarantee his own economic survival.44 The re-evaluation of Eschenburg’s past and the subsequent debates among historians and political scientists had serious reverberations in parts of German academia, especially among those who had benefited from him as a mentor or conveyor, who alleged that this was a “campaign” waged against him after his death.45 Through these new findings and the resulting debates, the film G 151 and its entangled production and screening history become even more significant and relevant for contemporary viewers.

Conclusion

Given the knowledge that historians have uncovered in recent years, Eschenburg’s reluctance to openly discuss his own role in the Nazi reign seems comprehensible. Moreover, these findings raise the question what kind of source does film constitute today. As we have seen, a seemingly normal lecture and discussion was specifically staged for the film shoot; Eschenburg certainly was not the critical witness of the past that the film would have us believe. With a new, updated publication, the Eschenburg lecture could, like the speeches from the 1930s, function as a critical edition of a controversial past. His lecture spans two temporal perspectives: it discusses the historical events around 1930 in Germany and the function of films as propaganda, while it is itself a source for a critical reflection about how this era was remembered and interpreted during the 1970s. There are other filmed lectures that provide examples of how to conduct research using film documents in the digital era. For example, a selection of Marshall McLuhan’s filmed lectures from the 1960s and 1970s have been digitized and annotated46 for an online archive, where all of the available films have been issued with automatic text transcripts that make it easy for researchers to search for specific information. For the Eschenburg lecture, the TIB-AV portal that hosts G 151 and other IWF films will soon provide transcripts for selected films, such as the Eschenburg lecture. However, other films from the IWF history collection are still missing a speech transcription. An extension of the automatic transcription function could allow historians and media scholars to critically edit and analyze historical propaganda speeches. As film historians like Liliana Melgar Estrada and Eva Hielscher have shown, new possibilities of annotating film emerged with digital film editions since the 1990s.47 Additionally, Adelheid Heftberger and Barbara Flückiger have demonstrated how digital humanities approaches can be made fruitful in film analysis.48 As they have rightly pointed out, the challenges of use and screening in the digital age go beyond technical questions. Using film and sound as a historical source in the digital age of today reactivates previous questions of how to conduct source criticism with the audiovisual documents that Wilhelm Treue, Friedrich Terveen, or Günter Moltmann engaged with earlier. But it also provokes new questions: how do we treat the metadata of a film? How do we approach the question of materiality? Do we go into the archives and watch 16-mm prints or rather rely on digital copies on the internet, risking that we miss out on parts of the film? How do we handle additional media, such as pdfs linked on the digital media platform AV-portal? In this article, I have shown that the audience is a critical component to the way in which film is perceived throughout history. In 1970, amid the political and educational turmoil in Germany, the Eschenburg lecture, and hence all G-edition films at the IWF, were used at universities to address political culture and election campaigning between 1930 and 1933. Today, we have to reevaluate a prospective audience: be it researchers of oral histories or students in the history of science, with the time that has passed since the film’s release, the prospective viewer changes and thus the questions addressed to the film.

- 1For further readings about the history of the IWF and the term “research film”/ “Forschungsfilm” see: Anja Sattelmacher, Mario Schulze, and Sarine Waltenspül, “Introduction: Reusing Research Film and the Institute for Scientific Film,” Isis 112, no. 2 (2021): 291–298, https://doi.org/10.1086/714823.

- 2Gotthard Wolf, “Zur systematischen filmischen Bewegungsdokumentation,” in Der Film im Dienste der Wissenschaft: Festschrift zur Einweihung des Neubaues für das Institut für den wissenschaftlichen Film, ed. Insitut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film (Göttingen, 1961), 33. For film collections for the future within the GDR during the 1970s see also: Anne Barnert, “A State Commemorates Itself: The Staatliche Filmdokumentation at the German Democratic Republic Film Archive,” Research in Film and History 1 (2018): 1–13, https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14789.

- 3G 151 Theodor ESCHENBURG SPRICHT ÜBER POLITISCHE FILMDOKUMENTE AUS DEN JAHREN 1930–1933, TÜBINGEN 1970 (D 1975), 16 mm/digibeta. IWF, https://av.tib.eu/media/11174.

- 4Günter Moltmann, “Film- und Tondokumente als Quellen zeitgeschichtlicher Forschung,” in Zeitgeschichte im Film- und Tondokument: 17 historische, pädagogische und sozialwissenschaftliche Beiträge, ed. Günter Moltmann and Karl-Friedrich Reimers (Göttingen: Muster-Schmidt Verlag, 1970), 17.

- 5Moltmann, “Film- und Tondokumente,” 18.

- 6Wilhelm Treue, “Das Filmdokument Als Geschichtsquelle,” Historische Zeitschrift 186, no. 1 (1958): 308–327, https://doi.org/10.1524/hzhz.1958.186.jg.308.

- 7Treue, “Das Filmdokument,” 322.

- 8Moltmann, “Film- und Tondokumente,” 19; Treue, “Das Filmdokument,” 322.

- 9Cv. Rainer Eisfeld, ed., Mitgemacht. Theodor Eschenburgs Beteiligung an “Arisierungen” im Nationalsozialismus (Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-07216-2, and the well documented debate within the German (print) media, such as Willi Winkler, “Zerfall einer Legende,” Süddeutsche Zeitung, October 17, 2014, https://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/politikwissenschaftler-theodoreschenburg-zerfall-einer-legende-1.2176606.

- 10For the history of the German student revolt see, for example: Martin Klimke and Joachim Scharloth, eds., 1968 Handbuch zur Kultur- und Mediengeschichte der Studentenbewegung (Stuttgart and Weimar: Verlag J.B. Metzler, 2007), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-476-00090-3, whose contributions give insight into the media history of the years around 1968.

- 11G 126 HITLERS AUFRUF AN DAS DEUTSCHE VOLK.

- 12G 151 THEODOR ESCHENBURG SPRICHT.

- 13For a further analysis of the interrelation between sound and propaganda, see: Joachim-Felix Leonhard, “Medien im Nationalsozialismus,” in Medien und NS-Diktatur: Einführende Überlegungen, ed. Sönke Neitzel and Bernd Heidenreich (Brill Schöningh, 2010), 13–28, https://doi.org/10.30965/9783657767106_003.

- 14Moltmann, “Film- und Tondokumente,” 21.

- 15Ibid.

- 16Ibid., 22.

- 17See: Fritz Terveen, ed., Dokumente zur Geschichte der Schulfilmbewegung in Deutschland (Emstetten: Lechte, 1958).

- 18Horst Ruprecht, Lehren und lernen mit Filmen (Bad Heilbrunn/Obb.: Klinkhardt, 1970).

- 19Ruprecht, Lehren und Lernen mit Filmen, 37.

- 20Peter Meyers, Film im Geschichtsunterricht. Realitätsprojektionen in deutschen Dokumentar- und Spielfilmen von der NS-Zeit bis zur Bundesrepublik; geschichtsdidaktische und unterrichtspraktische Überlegungen (Frankfurt am Main: Diesterweg, 1998).

- 21See: Christian Metz, Semiologie des Films (Munich: Fink, 1972); Werner Faulstich, Einführung in die Filmanalyse (Tübingen: Narr, 1978); Knut Hickethier, Methoden der Film- und Fernsehanalyse (Stuttgart: Metzler, 1979).

- 22Karl-Friedrich Reimers, “Audio-visuelle Dokumente in der Forschung und Hochschule. Die ‘Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte’ des Instituts für den Wissenschaftlichen Film (IWF), Göttingen,” in Zeitgeschichte im Film- und Tondokument: 17 historische, pädagogische und sozialwissenschaftliche Beiträge, ed. Günter Moltmann and Karl-Friedrich Reimers (Göttingen: Muster-Schmidt Verlag, 1970), 127.

- 23Reimers, “Audio-visuelle Dokumente,” 130.

- 24Ibid.

- 25Ibid., 131–132.

- 26Gotthard Wolf, Der wissenschaftliche Dokumentationsfilm und die Encyclopaedia Cinematographica (Munich: Barth, 1967), 184.

- 27As suggested by Reimers many times, i.e. in Reimers, “Audio-visuelle Dokumente,” 127.

- 28Ruprecht, Lehren und Lernen mit Filmen, 68.

- 29Eef Masson, “A Legal Alien: The 16mm Projector in the Classroom,” in Exposing the Film Apparatus, ed. Giovanna Fossati and Annie van den Oever (Amsterdam: AUP, 2016), 203–208.

- 30IWF films G 8 BRÜNING, G 20 PAUL LÖBE SPRICHT, G 29 AUS EINER WAHLREDE HITLERS IN EBERSWALDE, G 126 HITLERS AUFRUF AN DAS DEUTSCHE VOLK.

- 31Friedrich Terveen, G 8 Brüning. Aus einer Rede zu den Reichstagswahlen vom 14, September 1930. Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte (Göttingen: IWF, 1959); A. Hauter and Friedrich Terveen, G 20 Paul Löbe spricht über dringende Aufgaben des Deutschen Reichstages um die Jahreswende 1930/31, Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte (Göttingen: Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film, 1967); Friedrich Terveen, G 29 Aus einer Wahlrede Hitlers in Eberswalde. 27. Juli 1932, Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte (Göttingen: IWF, 1958); Karl-Friedrich Reimers, G 126 Hitlers Aufruf an das deutsche Volk vom 10. Februar 1933, Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte (Göttingen: IWF, 1971).

- 32For a detailed description of the system of film printing processes at the IWF, see: Anja Sattelmacher, “Self-Testimony of a Past Present: Reuses of Historical Film Documents,” NTM Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik und Medizin 29, no. 2 (2021): 143–170, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00048-021-00300-z.

- 33Ruprecht, Lehren und Lernen mit Filmen, 5–6, 58–59.

- 34Meyers, Film im Geschichtsunterricht, 55.

- 35Eckhard Jesse, “Theodor Eschenburg, Doyen der deutschen Politikwissenschaft: Einst unumstritten, streitbar, heute umstritten, unbestreitbar,” Zeitschrift für Politik 62, no. 4 (2015): 457.

- 36Jesse, “Theodor Eschenburg. Doyen,” 457–458.

- 37Rainer Eisfeld, “Theodor Eschenburg: Übrigens vergaß er noch zu erwähnen... Eine Studie zum Kontinuitätsproblem in der Politikwissenschaft,” ZfG 59 (2011): 27–44.

- 38Documented in the Correspondance between Eschenburg and Reimers, which is archived under file number IWF_13017_Redaktion Reimers at the TIB Hannover/Rethen.

- 39Eschenburg’s own disdainful attitude toward the student movement becomes obvious in the articles he published in Die Zeit and has well been documented in Eisfeld, Mitgemacht, 90–107.

- 40Eschenburg to Reimers, Tübingen, 20.06.1970, IWF_13017_Redaktion Reimers.

- 41Eschenburg to Reimers, Tübingen, 27.08.1969, IWF_13017_Redaktion Reimers.

- 42Personal telephone interview Sattelmacher/Reimers, March 27, 2021.

- 43See Eisfeld, Mitgemacht, 111–118.

- 44Eisfeld, “Theodor Eschenburg,” 603.

- 45Eisfeld, Mitgemacht, 15–19.

- 46https://www.marshallmcluhanspeaks.com/index.html.

- 47Liliana Melgar Estrada, Eva Hielscher et al., “Film Analysis as Annotation: Exploring Current Tools,” The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists 17, no. 2 (2017): 40–70, https://doi.org/10.5749/movingimage.17.2.0040.

- 48Barbara Flückiger, “Digitalisierung des Filmerbes,” Montage AV. Zeitschrift für Theorie und Geschichte audiovisueller Kommunikation 27, no. 1 (2018): 153–168, http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16836; Adelheid Heftberger, Kollision der Kader: Dziga Vertovs Filme, die Visualisierung ihrer Strukturen und die Digital Humanities (München: edition text + kritik, 2016), https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12910.

Barnert, Anne. “A State Commemorates Itself: The Staatliche Filmdokumentation at the German Democratic Republic Film Archive.” Research in Film and History 1 (2018): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14789.

Eisfeld, Rainer. “Theodor Eschenburg und der Raum jüdischer Vermögen 1938/39.” Vierteljahreshefte für Zeitgeschichte 62, no. 4 (2014): 603–626.

Eisfeld, Rainer. “Theodor Eschenburg: Übrigens vergaß er noch zu erwähnen...Eine Studie zum Kontinuitätsproblem in der Politikwissenschaft.” ZfG 59 (2011): 27–44.

Eisfeld, Rainer, ed. Mitgemacht. Theodor Eschenburgs Beteiligung an “Arisierungen” im Nationalsozialismus. Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-07216-2.

Estrada, Liliana Melgar, and Eva Hielscher, et al. “Film Analysis as Annotation: Exploring Current Tools.” The Moving Image: The Journal of the Association of Moving Image Archivists 17, no. 2 (2017): 40–70. https://doi.org/10.5749/movingimage.17.2.0040.

Faulstich, Werner. Einführung in die Filmanalyse. Tübingen: Narr, 1978.

Flückiger, Barbara. “Digitalisierung des Filmerbes.” Montage AV. Zeitschrift für Theorie und Geschichte audiovisueller Kommunikation 27, no. 1 (2018): 153–168. http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/16836.

Heftberger, Adelheid. Kollision der Kader: Dziga Vertovs Filme, die Visualisierung ihrer Strukturen und die Digital Humanities. München: edition text + kritik, 2016. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/12910.

Hickethier, Knut. Methoden der Film- und Fernsehanalyse. Stuttgart: Metzler, 1979.

Hauter, A., and Friedrich Terveen. G 20 Paul Löbe spricht über dringende Aufgaben des Deutschen Reichstages um die Jahreswende 1930/31. Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte. Göttingen: Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film, 1967.

Jesse, Eckhard. “Theodor Eschenburg, Doyen der deutschen Politikwissenschaft: Einst unumstritten, streitbar, heute umstritten, unbestreitbar.” Zeitschrift für Politik 62, no. 4 (2015): 457–470.

Klimke, Martin, and Joachim Scharloth, eds. 1968 Handbuch zur Kultur- und Mediengeschichte der Studentenbewegung. Stuttgart and Weimar: Verlag J.B. Metzler, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-476-00090-3.

Knopf, Eva. “Der Forschungsfilm zwischen Spielfilm, Rüstungsforschung und ziviler Wissenschaft.” In Film und Geschichte: Produktion und Erfahrung von Geschichte durch Bewegtbild und Ton, edited by Delia González de Reufels, Rasmus Greiner, and Winfried Pauleit, 27–35. Berlin: Bertz + Fischer, 2015.

Leonhard, Joachim-Felix. “Medien im Nationalsozialismus.” In Medien und NS-Diktatur: Einführende Überlegungen, edited by Sönke Neitzel and Bernd Heidenreich, 13–28. Paderborn: Brill Schöningh, 2010. https://doi.org/10.30965/9783657767106_003.

Marshall McLuhan Speaks. Special Collection. Accessed May 11, 2022. https://www.marshallmcluhanspeaks.com/index.html.

Masson, Eef. “A Legal Alien: The 16mm Projector in the Classroom.” In Exposing the Film Apparatus, edited by Giovanna Fossati and Annie van den Oever, 203–208. Amsterdam: AUP, 2016.

Meyers, Peter. Film im Geschichtsunterricht. Realitätsprojektionen in deutschen Dokumentarund Spielfilmen von der NS-Zeit bis zur Bundesrepublik; geschichtsdidaktische und unterrichtspraktische Überlegungen. Frankfurt am Main: Diesterweg, 1998.

Metz, Christian. Semiologie des Films. München: Fink, 1972.

Moltmann, Günter, and Karl-Friedrich Reimers, eds. Zeitgeschichte im Film- und Tondokument: 17 historische, pädagogische und sozialwissenschaftliche Beiträge. Göttingen: Muster-Schmidt Verlag, 1970.

Moltmann, Günter. “Film- und Tondokumente als Quellen zeitgeschichtlicher Forschung.” In Zeitgeschichte im Film- und Tondokument: 17 historische, pädagogische und sozialwissenschaftliche Beiträge, edited by Günter Moltmann and Karl-Friedrich Reimers, 17–24. Göttingen: Muster-Schmidt Verlag, 1970.

Reimers, Karl-Friedrich. Theodor Eschenburg spricht über politische Filmdokumente aus den Jahren 1930–1933, Tübingen 1970. Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte. Göttingen: Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film, 1975.

Reimers, Karl-Friedrich. “Audio-visuelle Dokumente in der Forschung und Hochschule. Die ‘Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte’ des Instituts für den Wissenschaftlichen Film (IWF), Göttingen.” In Zeitgeschichte im Film- und Tondokument: 17 historische, pädagogische und sozialwissenschaftliche Beiträge, edited by Günter Moltmann and Karl-Friedrich Reimers, 109–142. Göttingen: Muster-Schmidt Verlag, 1970.

Reimers, Karl-Friedrich. G 126 Hitlers Aufruf an das deutsche Volk vom 10. Februar 1933. Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte. Göttingen: IWF, 1971.

Ruprecht, Horst. Lehren und lernen mit Filmen. Bad Heilbrunn/Obb.: Klinkhardt, 1970.

Sattelmacher, Anja, Mario Schulze, and Sarine Waltenspül. “Introduction: Reusing Research Film and the Institute for Scientific Film.” Isis 112, no. 2 (2021): 291–298. https://doi.org/10.1086/714823.

Sattelmacher, Anja. “‘Self-Testimony of a Past Present’: Reuses of Historical Film Documents.” NTM Zeitschrift für Geschichte der Wissenschaften, Technik und Medizin 29, no. 2 (2021): 143–170. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00048-021-00300-z.

Terveen, Friedrich. G 29 Aus einer Wahlrede Hitlers in Eberswalde. 27. Juli 1932. Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte. Göttingen: IWF, 1958.

Terveen, Friedrich. G 8 Brüning. Aus einer Rede zu den Reichstagswahlen vom 14, September 1930. Filmdokumente zur Zeitgeschichte. Göttingen: IWF, 1959.

Terveen, Fritz, ed. Dokumente zur Geschichte der Schulfilmbewegung in Deutschland. Emstetten: Lechte, 1958.

Treue, Wilhelm. “Das Filmdokument Als Geschichtsquelle.” Historische Zeitschrift 186, no. 1 (1958): 308–327. https://doi.org/10.1524/hzhz.1958.186.jg.308.

Winkler, Willi. “Zerfall einer Legende.” Süddeutsche Zeitung, October 17, 2014. https://www.sueddeutsche.de/kultur/politikwissenschaftler-theodor-eschenburg-zerfall-einer-legende1.2176606.

Wolf, Gotthard. “Zur systematischen filmischen Bewegungsdokumentation.” In Der Film im Dienste der Wissenschaft : Festschrift zur Einweihung des Neubaues für das Institut für den wissenschaftlichen Film. Göttingen: IWF, 1961, 16–40.

Wolf, Gotthard. Der wissenschaftliche Dokumentationsfilm und die Encyclopaedia Cinematographica. München: Barth, 1967.

Archival Sources

TIB Hannover/Rethen, IWF Archive, IWF_13017_Redaktion Reimers.