No Instructions, Just Some Advice

Agricultural Film and the Pedagogy of Consulting in 1950s and 1960s Austria

Table of Contents

Screening Propaganda

In Defense of Culture

The Raw Materials of Celluloid Film

Wholeness and Nature

The Austrian Province as Subject and Space of Action in Educational Film Practices

The Development of Educational Cinema for Schools in the Soviet Union in the 1930s

Educational Film in East Germany (GDR) in 1950–1990 in Perspective of the “Grammar of Schooling”

No Instructions, Just Some Advice

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Schätz, Joachim. “No Instructions, Just Some Advice: Agricultural Film and the Pedagogy of Consulting in 1950s and 1960s Austria.” Research in Film and History 5 (2023): 1–45. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/22726.

In 1965, German pedagogical theorist Klaus Mollenhauer wrote an influential essay on the then-booming field of consulting, counseling, advice and guidance (what in German is summed up as Beratung).1 In this short text, he made two claims that are of pressing interest to a historiography of educational film practice. Firstly, Mollenhauer declared consultation to be a fundamentally pedagogical situation – although one that challenged much of his time’s pedagogy due to what he perceived as its democratic proclivity for eye-level dialogue and the activity of the learner. Secondly, he noted that consultation on all kinds of matters was proliferating in the mid-1960s on two sites: in dedicated public institutions (Beratungsstellen) and in mass media.2 Taking Mollenhauer’s observations as first hints to the nexus between pedagogy, consultation and media usage in 1950s and 1960s Europe, I will investigate this relationship for the area of agriculture.

My case study concerns the occupational counseling of Austrian farmers in the 1950s and 1960s, as reflected in the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry’s Film and Slide Service [Film und Lichtbildstelle des Bundesministeriums für Land- und Forstwirtschaft], which was established in 1950.3 While building upon scholarship on the media history of consulting, this example is hopefully instructive in highlighting the pedagogical side of consulting which has been underexplored in media studies up to this point.

There have been some proposals in recent media history about how different media have been constitutive not just for practices, but for the very concept of consulting in certain time periods.4 The most fruitful of these for my purposes is Florian Hoof’s exploration of the epistemic construct that he calls “consulting knowledge” and its emergence in business consultancy between 1880 and 1930. Hoof argues that the type of knowledge sold by foundational business consultants like Frank and Lillian Gilbreth and H.L. Gannt in the U.S. (but quickly expanding to Europe by the 1910s)5 was not merely represented and popularized via films, graphs and symbolic images. Rather, these media usages were the genuine sites of this emerging “consulting knowledge” and its very structure.

Hoof describes this structure as highly modular, flexible and often ad-hoc, yet given recognizable shape and a scientific air by standardized vocabularies and visual models. Finally, he demonstrates that the usefulness of the new-ish medium of film for business consulting in the early 20th century lay not just in its new technical affordances for recording and analyzing movement, but also in the broad and blurry cultural significance that film and cinema held for overlapping publics at the time (as a tool of science as well as an entertainment apart from work). Thus, there were many angles from which film could be made palatable and even advantageous as a means in business consulting, acceptable to a company’s management as well as the workforce.6

Agriculture’s Consulting Push after 1945 and the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry’s Film and Slide Service

The counseling of Austrian farmers in the 1950s and 1960s was explicitly framed at the time as a type of business consultancy, albeit one that addressed not big companies, but small, family businesses often not involving much of or any external workforce.7 But the term “consulting” proved broader and more slippery here: Firstly, given the structure of small-scale farming, the areas of business addressed by the advice couldn’t be cleanly separated from what was perceived to be the farmers’ private life. Given the structure of small-scale family farming, the consulting often encompassed the design of living quarters and the everyday divisions of labor in the family, blurring the line between business consultancy and more intimately coded modes of life advice.8

Secondly, in contrast to the business consultancy that Hoof analyzes, this consulting was mostly not a free-market service, but something provided to (and sometimes pushed on) farmers by national institutions (like the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry) and the farmers’ own professional representation, the tight-knit network of Chambers of Agriculture [Landwirtschaftskammern] all over the country. Given the important status of farming for Austria’s economy overall at the time, as well as farming’s outsized influence and representation within the conservative political party Österreichische Volkspartei [Austrian People’s Party] (ÖVP) which appointed the Austrian chancellor all through the 1950s and 1960s, consulting was also one way for ensuring the orientation and vying for the cooperation of farmers towards shifting agrarian-political goals over the 1950s and 1960s.9 Corresponding to the intermediate and contested status of farmers in the period, which is not limited to Austria – as independent businessowners and yet increasingly parts of an overall structure of subsidies and overarching planning processes on the state and nation level – the framing as ‘consultation’ was also strategic: a way of framing professional training and instruction in a diplomatic and non-invasive manner.

Indeed, the term ‘consultation’ was stressed in Austrian agriculture after 1945 for the whole area of professional training much of which had previously been framed as further education (and which had involved the dedicated production and use of film at least since the mid-1920s).10 The “itinerant teachers” of the late 19th century were reclaimed as the precursors of that day’s “consultants.”11 Occasionally, even formal education in agricultural schools was argued to work as a type of “group consultation,” as advice was being fed back from the students to their elders at the family farm.12 The closeness of consultation and formal education is also stressed by the fact that after 1947, agricultural consultants and teachers in agricultural vocational schools needed to pass the same exam.13 Consultants mostly worked in the staff of Chambers of Agriculture, both at the level of the province and its local offices in different districts (called Bezirksbauernkammern or District Chambers of Agriculture). The Chambers’ consultants were supposed to work on behalf of the farmer and honestly assess the claims of both political and business interests.14 Of course, the priorities of consultation also reflected different interests, among them those of Austria’s agrarian, economic and political elites, but also international interests and influences. In the early 1950s, US support and involvement is credited prominently with bringing the new system of consultation to Austrian farming.15

This newfound centrality of consulting as something close to, but distinct from outright teaching, in Austrian agriculture is exemplified, among others, by the Austrian Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry issuing a monthly journal called Der Förderungsdienst, roughly meaning The Assistance Service, from 1953 to 2000. The journal addressed both teachers and consultants in issues of farming – including lots of psychological, pedagogical and mediapedagogical considerations for the two areas of work. Pointedly, it is almost exclusively in the area of agriculture where the German term of “Beratungsfilm” [“consulting film”] is being coined and discussed in the postwar decades in Austria and West Germany – as something separate from educational and instructional films. Most prominently, the International Competition of Agrarian Film held biennially in West Berlin from 1960 to 1986 featured “Beratungsfilm” as its own self-contained category, apart from the labels of research film, classroom film, public relations film and advertising film.16

It is likely from there that the term ‘consulting film’ is taken up when it appears in Der Förderungsdienst and other Austrian publications starting the early 1960s to describe a big part of the films that had been distributed by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry’s Film and Slide Service since its inception in 1950.17 (Similarly, I will also retroactively use the term to describe films produced and distributed slightly before its usage, as long as they were intended to be used at consultations.) While also providing image films on farming for general audiences, the service mainly provided for-free film distribution for the purposes of agricultural education and consultation.18 The range of film production companies and commissioning bodies when looking through the service’s 1968 film catalogue reflects the different interests involved in agricultural consultation: While films commissioned or produced by national or state institutions like the Austrian Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry, Austria’s public broadcaster Österreichischer Rundfunk [Austrian Broadcasting Corporation] (ORF) or the West German agrarian public service institution Land- und Hauswirtschaftlicher Auswertungs- und Informationsdienst [Agricultural and Domestic Evaluation and Information Service] (AID) are in the majority, there are also films commissioned by companies promoting their wares (such as fertilizers, motor oil, machines and tires), as well as remnants of the US-directed Marshall Plan program of film production and distribution.19 This mixture is also comparable to other contemporaneous collections of vocational training films, such as the film collection of the Austrian Productivity Center [Österreichische Produktivitäts-Zentrum].20

Drawing on the surviving collection of films and accompanying materials from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry’s Film and Slide Service,21 I am asking: What, when and where is a consulting film, and what can we glean from it about the dynamics of consulting – between instruction, coercion and support for autonomously finding solutions – that it was involved in? And if the concept of consultation in this case is partly the sugarcoating of a more hierarchical idea of instruction, are there also aspects to it that fulfill what Mollenhauer saw as consulting’s challenge to pedagogical hierarchies and the instructor’s dominance at the time?

Teaching to Take Advice: Consultancy as Conversion in RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT (AT 1954)

According to Der Förderungsdienst, consultation proved a tough sell to farmers, to say nothing of top-down instruction. Farmers were described as none too willing to take, much less ask for, the advice being offered to them. For instance, West German farming professor Hans Rheinwald noted in a 1952 study that, in contrast to medical consultations, usually the first task of the consultant was to instill the “will to be counseled” in the farmers he looked to counsel.22 While this recalcitrance was often explained by way of essentialising the “peasant type” and ‘his’ characteristics, described with varying ratios of reverence and condescension,23 it can partly be understood as a byproduct of conservative politics’ instrumentalization of farming. Austria’s center-right parties – ÖVP as well as its predecessor, the Christlichsoziale Partei [Christian Social Party] (CSP, 1891–1934) – had counted farmers among their key constituents. The imperative for accepting outside expertise clashed with the ideology of farming as a traditional, autonomous way of life anchored in locally perfected knowledge that had been cultivated by right-wing political actors (and had been a keystone of the Austrofascist Chancellor Dictatorship of 1933 to 1938, which was established by former minister of agriculture Engelbert Dollfuß). This had often involved the same institutions, such as the provinces’ Chambers of Agriculture and their district offices, that now set up consultation programs and asked for farmers to open up their work processes to outside expertise.24

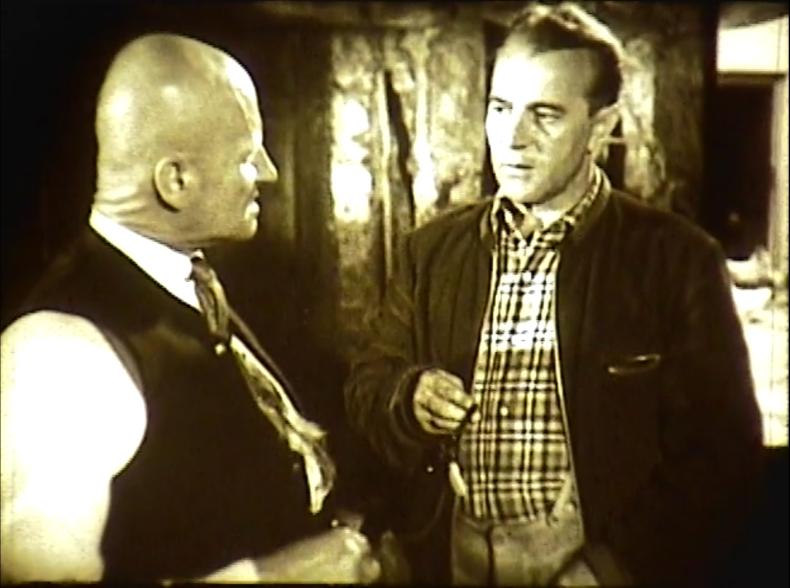

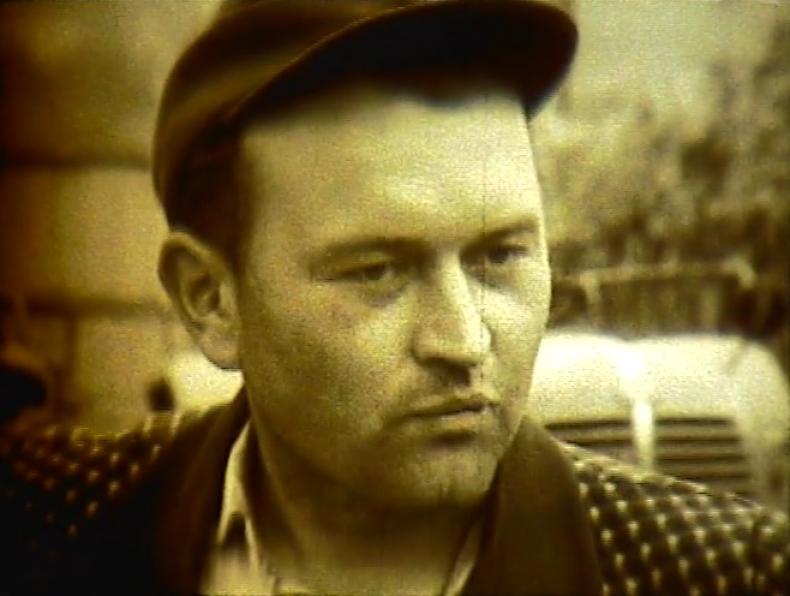

The Chambers of Agriculture’s consultants were supposed to bridge this gap, as well as the hierarchy between expert and layperson, not just with their lucid reasoning, but also with measured persuasion, even “leadership,” as a 1959 essay on “The Personality of the Consultant” states. Having studied agriculture, but usually not farming themselves, consultants were expected to build trust by proving practical knowledge, using straight and clear language and being irreproachable in private matters, as “the farmer knows no distinction between professional and private life.”25 Obviously, success was not a given. The fraught relationship between consultants and farmers is the subject of many a consultant joke.26 It also structures a lot of agricultural consulting films. Sometimes, it is front and center in the films themselves, as in the 1954 short film RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT / ABOUT DAIRY FARMING (AT 1954), directed by Georg Tressler. The film was jointly commissioned by the Ministry of Agriculture and the American Economic Mission in Austria, so the context here is very much the European Recovery Program (ERP) and its push for productivity increase. Like other consulting films from the period, this one tells the story of consulting a farm as a drama of persuasion: A young farmer is prepared to change the setup and ventilation of his cowshed for hygenic reasons according to the advice of the consultant at the local Chamber of Agriculture branch. But the farmer’s father cannot be reasoned with. He has to be swayed by the shock of a grandchild possibly having caught tuberculosis via contaminated milk and then gradually convinced by the local consultant (fig. 1).

In the drawn-out drama of consultancy-as-conversion, a visit to a local nontheatrical film screening of an American instructional cartoon is a key event (fig. 2–4). Director Tressler knew his way around such events: Before directing Marshall Plan films, which would precipitate a long career as a feature film and television director, he had started out as a projectionist for one of the Economic Cooperation Administration’s mobile film units that showed Marshall Plan films to rural populations.27 Still, the screening is staged not as a self-sufficient cure-all for scepticism. Rather, it is shown to be only one moment in a delicate dance between outside expertise, represented by the consultant, and traditional know-how, represented by the old farmer. After the film screening comes the guided visit to a neighbor’s overhauled stables. And even during the screening, the farmer needs the expert answering his gripes and discreetly whispering in his ear to maintain cooperation and keep his attention onscreen (fig. 5). In other moments, meanwhile, the expert is shown to consciously hold back and not play out his knowledge too triumphantly.

RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT was not alone among Austrian consulting films in foregrounding and fictionalizing the relationship between the consultant and their subject within the film. For instance, the fire safety film HINTERM HOF – DER FEUERREITER / BEHIND THE FARM – THE FIRE RIDER (AT ca. 1950) warns against fire hazards in farming by putting fictionalized farmers in between two figures trying to pull them on their side. The calm male consultant is opposed by a querulous woman. In a twist spelling out the misogyny of the construction, she is revealed to be a witch doing the bidding of the mythic “fire rider” (very loosely inspired by an Eduard Mörike poem that is well-known in German-speaking countries) who rides from farm to farm hungry for the next fire to start.28

In contrast to this shrill warning to heed the expert’s call, RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT with its gradual narrative of patient consultation presents a rather flattering portrait of the push for outside guidance and expertise that changed Austrian farming in the 1950s in the context of the ERP. This shift outlasted the Marshall Plan, of course. The change lay not so much in the political drive for agricultural modernization per se (which had been pursued by agricultural institutions in Austria since at least the 1890s). Rather, what was new was the willingness to embrace a more technocratic self-image rather than camouflage the business of agriculture with a politically useful ideology of peasantry as a tradition-bound way of life.29 For the lasting focus on high performance and scientification, see for instance these stills (fig. 6–8) from a later consulting film on the monitoring of farms’ “dairy performance” (MILCHLEISTUNGSKONTROLLE / CONTROL OF DAIRY PERFORMANCE, AT 1964).

While many consulting films across the 1950s and 1960s share the appeal to an externalized expert knowledge, as well as a predilection for the well-tested dramaturgy of ‘before and after’ aimed to demonstrate the merits of the proposed changes,30 the asymmetrical relationship between the films’ addressees and this expert knowledge is navigated and massaged in a range of ways. These include not just fictionalized models of the consultation process as staged in RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT but all kinds of visual and verbal nuances, from observational tasks given to the viewer to the use of open-ended and rhetorical questions to avoid the outright declaration of rules.31 And I will end the article by investigating some of the new inflections made in the staging of the consultation process in the mid-1960s.

But before I come to these changes, I want to turn to the setting of consultation and the way films were thought to fit into it. Because, as RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT emphasizes, the film screening – while being costly to the organisation and impressive to the viewer – is not the sole or even the most crucial element of the consulting process. In this sense, this film – and a lot of writing on the use of agricultural consulting films at the time – agrees with a certain skepticism that Mollenhauer would vent in 1965 about the usefulness of mass media in consultation: Mollenhauer clocks a boom of periodicals, brochures, books, films and television programs offering advice on all kinds of topics. But for him these media necessarily fall short of what is key to the pedagogical ideal of a consultation: the answering to the specific demands of the person who is seeking advice, as well as the refusal to prescribe clean-cut solutions, both of which are best accommodated by open-ended conversation.32 For Mollenhauer, consulting is defined by the fact that “the contents are only brought out in the course of the counseling process, in such a way that the client brings them into the process.”33 RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT with its narrative of gradual opening up to advice at least partly agrees to this dialogic idea of consultation, even though its consultant has the correct answers all along. But what can film contribute to such a process of consultation? What place, time and tasks can film have in consulting?

Where, When and What Is a ‘Consulting Film’?

Where would such films be shown? Surviving loan service cards from the Ministry’s Film and Slide Service such as the one shown below this paragraph provide a tentative answer (fig. 9–10). The card, tracking the loans of another dairy film called FORTSCHRITTLICHE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT / PROGRESSIVE DAIRY FARMING (AT 1959), indicates that, like represented in RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT, the District Chambers of Agriculture (abbreviated as BBK on the card) were pivotal to the films’ distribution. Screenings at those branch offices and other farmers’ clubs were often part of so-called “mass consultations,” consisting of a lecture and a discussion with the consultant, and hopefully leading to dates for individual counseling. Complicating the distinction between consulting and education, the film was loaned out to agricultural schools about as often as to Chamber of Agriculture branch offices.34

Other loan cards indicate that occasional loaners also included trade fairs, universities, and companies selling to farmers.35 As far as the frequency of a title’s loans is concerned, the loan history of FORTSCHRITTLICHE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT is fairly representative of the surviving loan cards, which is to say: Most individual titles seem not to have been in heavy rotation, but loaned out about two to five times a year during their times of use. In other words: The term “mass media” as used by Mollenhauer for the media proliferation of advice might only be generously applied to the 16mm films distributed by the Ministry’s Film and Slide Service.36 But while individual titles were usually not widely distributed by the service, there were a lot of such low- to medium-interest films being loaned out at the same time.37

As suggested earlier, there was some effort to define the ‘consulting film’ as an entity distinct from films for formal education, for instance in the pages of Der Förderungsdienst. Ernst Kreuziger (1928–2000),38 the director of the Ministry’s Film and Slide Service, argued that while classroom films were supposed to cover basics of farming education, consulting films were meant to tackle up-to-date subjects of interest, including new farming technologies, political guidelines or business recommendations. Consequently, consulting films were described as being necessarily more short-lived in their usefulness than comparable agricultural films for schools.39

Also, one film might not be applicable to different geographical areas. This obviously goes for national differences in economic policy. For instance, a prominent West-German film on the necessity for an economic restructuring of agriculture – DER BAUER ZWISCHEN GESTERN UND MORGEN / THE FARMER BETWEEN YESTERDAY AND TOMORROW (FRG 1964) – was distributed by the Ministry’s Film and Slide Service in Austria. But the print was sent out with a disclaimer: The leaflet (fig. 11) cautioned the lecturer to stress that while the film was pointing to pressing problems, its suggested solutions were not in line with the Austrian ministry’s policy.

Even beyond such national political differences, it was warned that local varieties in terrain and modes of production made generalized depictions of agricultural solutions difficult even within a rather small nation like Austria.40 From this vantage point, film in its relative inflexibility appears as a hindrance more than a help to the communication of individual needs and locally specific challenges that was seen as an important part not only of individual consultations, but also of so-called mass and group consultations with a lecture and discussion at the Chamber of Agriculture hall or the local inn. Looking for a modular mode of presenting information, some consultants declared film less useful than slides, which they could reassemble at will, as well as flannel boards – which were deemed great to visualize conceptual schemas, step-by-step processes and different uses of space, according to audience examples.

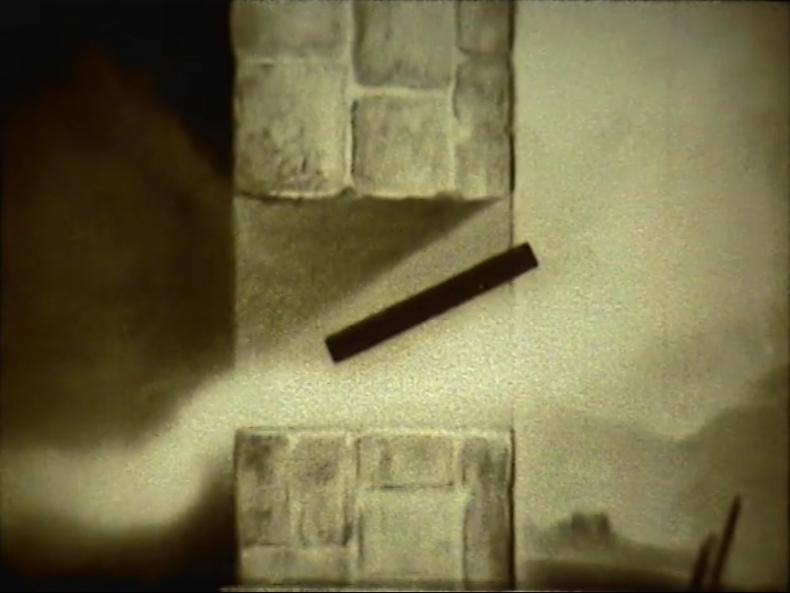

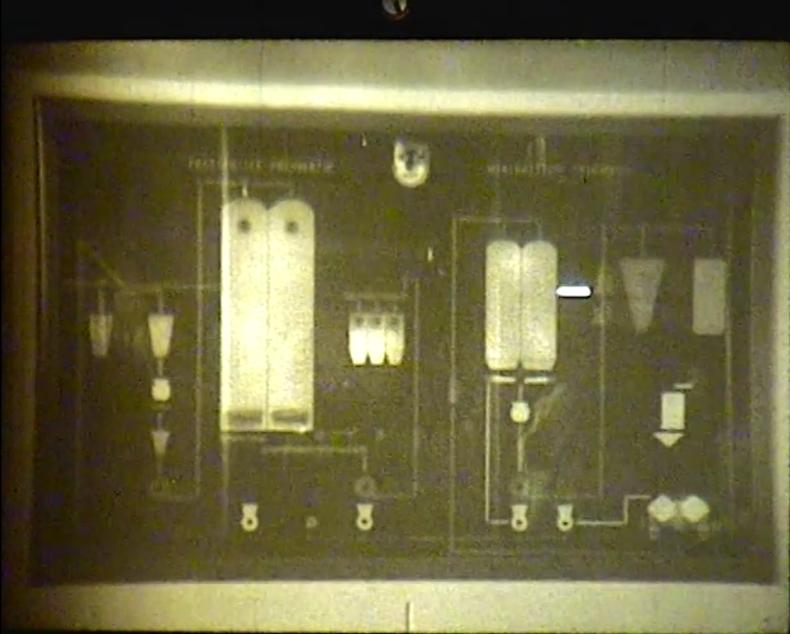

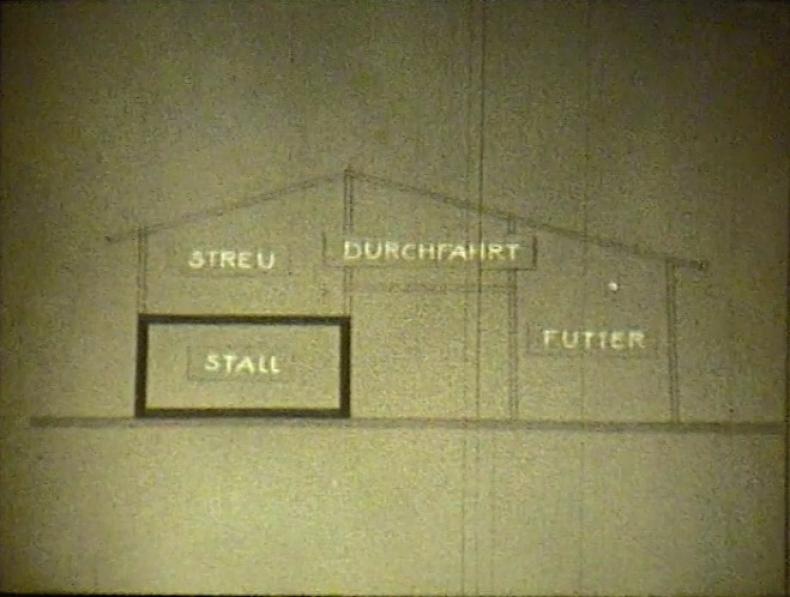

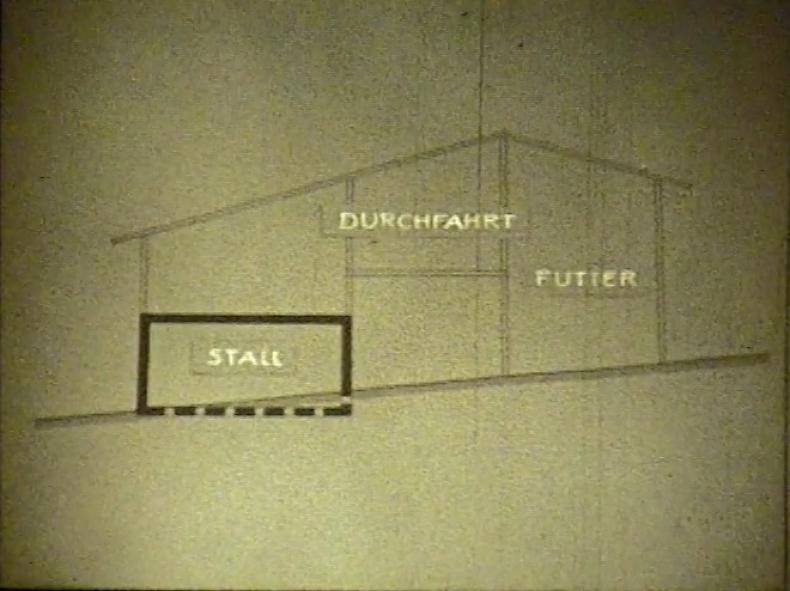

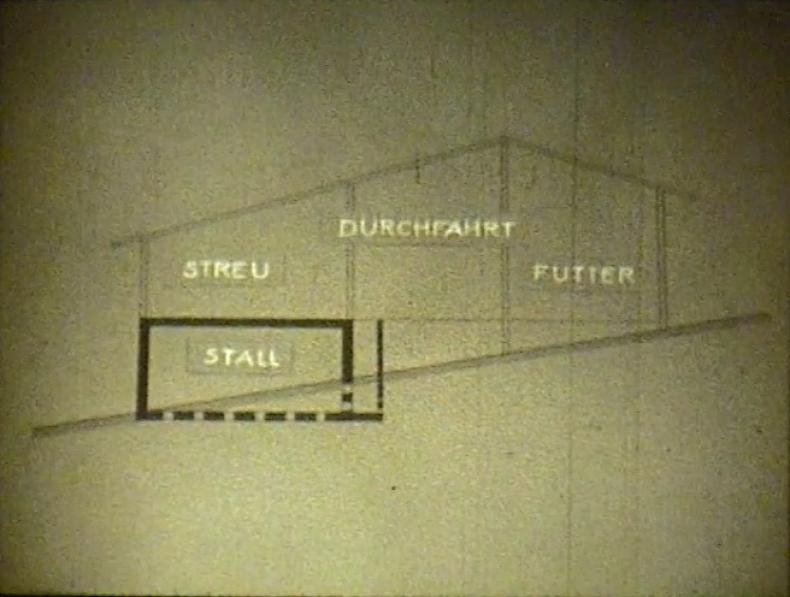

To make film projection fit into different contexts, agricultural consultants were urged to prudently choose which segments of a film to show (rather than the whole 20-minute film), and also which parts to complement with live-spoken commentary rather than the recorded soundtrack.41 While films were thus seen as supplies rather than integral units, the films themselves often already make use of a modular type of presentation. They gesture towards the need for interaction and local specification by enumerating different scenarios, often in abstract visual models. See two examples below, one on establishing an efficient work chain for harvesting hay (DIE LADE- UND TRANSPORTARBEITEN BEI DER HEUERNTE / THE LOADING AND TRANSPORT WORK AT THE HAY HARVEST, AT 1963, fig. 12–15), the other on ways of building a barn on different kinds of ground (HALLENBAUWEISE / HALL CONSTRUCTION, AT 1964, fig. 16–18).

The abstraction and slight variation of the visual model – a cornerstone of “consulting knowledge” – already goes a long way towards suggesting a model that was standardized, yet individually applicable. And it corresponds with the visuals of flannel boards and of the slides which were also distributed by the Film Service, and often packaged together with the films.42 “Ideally, for one given topic, i.e. accommodations, the consultant can be furnished with a film, a series of slides (or a flanel board), and a brochure.”43 The overlapping design of different media is made obvious by the fact that slides were also directly inserted into films, as in this case from a short consulting film about vegetable gardening (GEMÜSEGARTEN DER BÄUERIN / PEASANT WOMAN’S VEGETABLE GARDEN, AT 1964) on which Film and Slide Service director Kreuziger served as an expert adviser (fig. 19–20).

But if film’s relative rigidity needed to be counteracted by measures such as flexible use of excerpts and the approximation or reproduction of slides, what were the positive qualities that film was seen to bring to the table? What did film contribute to the constellation of consulting media, which included not just slides and boards, but also brochures, mathematical tables and workbooks?44 In contemporaneous advice texts for agricultural consultants, there are a lot of the well-known platitudes as to film’s unique abilities in transferring knowledge – often with a questionable inflection on how “everyone knows” of farmers especially being “optical types of people.”45 More instructively, one expert refers to slides as a “Lehrmittel” (a “teaching aid”), and contrasts this with film mostly serving as a “Zugmittel,” an “attraction.”

This is also how film projection is flaunted even within a lot of the films in the Film Service archive, for example at the opening of a French film on fertilizer dubbed GOLDREGEN AUF DIE KULTUREN / GOLDEN RAIN ON THE CROP (ca. 1955).46 Before going into its topic, the film starts by just basking in the view of interested people streaming into a lecture hall where a commented film screening about the production and uses of fertilizer is about to start. In a move that is apt for the makeshift re-use of media in such consultation lectures, when the film-lecture-within-the-film begins, this Austrian sync version keeps the lecturer’s original French voice audible, but dubs a German voice over it that talks about the prominence of French fertilizer in Austrian agriculture. While the film’s original French setting is kept transparent, a new audience and their local interests are addressed (video 1).

A number of texts advise consultants on how to use film’s attractive powers judiciously. The audience of consultations was perceived to be more fickle and demanding than the captive audience in a classroom. That is why it was accepted to use sound film for consulting. Classroom films were still primarily silent in German-speaking countries until the early 1960s – for budget reasons, but also out of pedagogical considerations. It was acknowledged that for consulting too, silent film with live commentary would be more useful. Still, according to Ernst Kreuziger, experience showed that “silent cinema” was being rejected as old-fashioned by the voluntary audiences of consultations.47

A similar trade-off between film’s attractiveness and its pedagogical usefulness is recommended with respect to the positioning of the film within a lecture: In a 1962 article, Kreuziger argues that from a pedagogical standpoint, a film should be shown rather early in a lecture presentation to efficiently use the film’s informational value and move on from there. In matters of consulting, however, he advocates for showing the film towards to end of the lecture, as a lure, so that the audience stays for the whole lecture and discussion. Alternatively, it was suggested to show the more pertinent film first and then a more broadly educational ‘Kulturfilm’ of general interest as a closer (but without going over a total runtime of 25 minutes).48

Learning to Give Advice: MIT RAT UND TAT and the Management of Consulting Relationships in the mid-1960s

On the one hand, the use of film as an attraction sketched in these proposals is very much in line with Hoof’s argument for film and cinema functioning in business consulting as “boundary objects” that ensure cooperativeness from a range of groups with different interests.49 On the other hand, we might wonder if film projection’s shine as an attraction in itself wouldn’t have worn off eventually after the upswing of consulting projections in the 1950s, even in remote locations without a movie theatre nearby.

Indeed, around 1960 the main attraction shifted from film to television in some ways: Austria’s public television premiered a monthly consulting program for farming, called MIT RAT UND TAT / IN WORD AND DEED, in November 1959. The 25-minute episodes drew on specialist input from the Chambers of Agriculture and the Ministry, which also got the rights to distribute prints of the episodes via its Film Service.50 Film projection was likely one key mode of distribution for those short films, given the low saturation of Austria’s households with TV sets until the mid-to-late-1960s.51 Until then, the appeal of television may have been mainly aspirational for most of MIT RAT UND TAT’s public: See your television broadcast of tomorrow as the non-theatrical screening of today!

By the mid-1960s, Austrian public broadcasting had become the main producer of new consulting films distributed by the Film Service.52 At the same time, changes in tone were also being detected in agricultural consulting films – not just in Austria, but internationally: In Munich-based educational film journal Film Bild Ton, the film educator and frequent contributor Walter Godenschweger noted after his visit to the first International Competition of Agricultural Film in 1960 West-Berlin that the trope of the smart expert and the slow-to-change farmer was by now being seen as overly clichéd and unpersuasive.53 Alternative dramaturgies of consulting were being tested. This demand for less of a heavy hand in structuring consulting via film as compared to conversion narratives like RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT was partly playing off the democratic ideal of consulting as an eye level exchange and joint reflection that Mollenhauer would also emphasize in his 1965 essay: something in the air in 1960s pedagogy.

The MIT RAT UND TAT television program didn’t radically upset the formula of consulting films, but it would occasionally gesture towards a less hierarchical, more open-ended investigation of topics. This would often involve making use of the lighter 16mm cameras and the synced sound equipment which had recently been used in television reporting (including early Direct Cinema productions) to alter the division of public and private acting and speaking.54 A 1966 episode on the business considerations of wine growing (WEINBAU UND BETRIEBSWIRTSCHAFT / WINE GROWING AND BUSINESS, AT) makes its points quickly and then veers into a final five-minute segment of interviews with winegrowers prompted to share their experiences (fig. 21–23). The Film and Slide Service’s film catalogue recommends to show the film early in a consulting event as the starting point for a discussion.55 The hands-off gesture of open exchange in the last section of the film is somewhat negated, however, by the insistent, sometimes hectoring questions of the unseen interviewer. Without stating his mission outright, the interviewer presses the farmers to consider the impractical costs of semi-professional small-scale winemaking versus joining cooperatives.

The striving for a new tone in the relationship of the expert and the addressee of their advice – more implicit than explicit in its directives – corresponds to a change in the key topics of agricultural consulting around 1960: Rather than ramping up production and maintaining health standards like in the early 1950s, the main aim in the new agrarian market of abundance was to optimize the individual farm’s work income. The stakes had switched from national health and sufficient food supply to individual profits.56

From this vantage point of a more individual address, it may make sense that one MIT RAT UND TAT episode even aped the journalistic format of the ‘homestory’ (a German anglicism), a staple format of German-language journalism about the visit to a celebrity’s residence.57 In the short film on the topic of how to best set up the transitional room between the farm and the private home (WIRTSCHAFTSRAUM / ECONOMY ROOM, AT 1966), the viewers are introduced by a local female Chamber of Agriculture consultant to the house of a farmer, Mrs. Ebner, who she had helped design this room. (The film is in keeping with the usual gendering of consulting films that addresses women explicitly mostly in matters of domestic management.) The resulting scenes, however, do not so much confer status on Frau Ebner and her exemplary economy room. Rather, what registers is the uneasy hierarchy between the expert and the layperson who is staged merely as a prop of her presentation (video 2). Throughout the film, Mrs. Ebner keeps being used like a mannequin to demonstrate functions of her room over which the consultant-moderator presides.

In conclusion, I would wager that even beyond the technical affordances of lighter 16mm sync-sound equipment, television journalism as a cultural entity is here being borrowed for strategies of how to manage the consultant’s address to their audience in different ways. The man-on-the-street interview and the homestory are tried out as ways of asserting hierarchies of knowledge without flaunting them in a manner that risks shutting down communication.

Conclusion: Consulting’s Subjects

Hoof suggests that the cultural technique of consulting is not least a means of managing and massaging societal lines of conflict, rather than addressing them head-on.58 Reading the mid-1960s consulting films from the MIT RAT UND TAT series from this vantage point, the volatile relationship of consulting is symptomatic of the tension between farming’s important political status and its shrinking market shares in 1960s Austria. This economic turmoil had led to a fundamental crisis of identity: Even in conservative Austria, which resisted radical restructuring of its small-scale agriculture, by the mid-1960s the scandalous question was repeatedly asked if farmers needed to be understood as businesspeople or rather as workers.59 The tonal shift between reverence for and objectification of the films’ intended public is also indicative of this unsure positioning: Are they the entrepreneurial subjects of business consulting, or a workforce receiving instructions? And what would that difference say about the subject that consulting presupposes?

According to educational scholar Katharina Gröning, Mollenhauer’s proposed concept of a pedagogical consultation never translated into institutional practice. While corresponding reforms of welfare institutions and schools faltered, the methodological profile of the consultant in West Germany was throughly shaped by psychology rather than pedagogy during the 1970s.60 Obviously, business consultancy never was mainly about the self-critical, empowered subject of enlightenment as lionized by Mollenhauer or the therapeutic subject that overwhelmed it in most areas in Gröning’s telling. Rather, business consultancy presupposes an entrepreneurial subject that seeks out orientation and a competitive advantage in the field of market competition. As argued by Nicolas Rose and Ulrich Bröckling, this role of the market competitor has been promoted beyond its original bounds into a hegemonic model for neoliberal subject formation since the 1970s: Addressed as an “entrepreneurial self” the individual is prompted to develop their market value like a smart, nimble company – not least by a bevy of consultant figures dedicated to unlocking potentials and cultivating skills.61

Now, these appeals to stay alert and flexible in all areas of life are a far cry from the often rather clear instructions-as-suggestions handed to farmers in the Film and Slide Service’s 1950s and 1960s consulting films. But there are moments when the films sound like demo reels for the interpellation of the later, more thoroughly captured entrepreneurial subject. In their bumpy turns between success stories of resourceful, well-adviced problem-solving and harsh threats to not be left in the dust by “live expressions of the market economy” like livestock exchanges and dairy performance controls (as it is phrased in the voice-over commentary for MILCHLEISTUNGSKONTROLLE), these films occasionally evoke the cheery desperation to creatively get ahead that is familiar from later stages of the entrepreneurial imperative.

- 1This research was funded in whole by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) P 32343-G (Educational Film Practice in Austria). For the purpose of open access, the author has applied a CC BY public copyright licence to any Author Accepted Manuscript version arising from this submission.

- 2See: Klaus Mollenhauer, “Das pädagogische Phänomen ‘Beratung,’” in “Führung” und “Beratung“ in pädagogischer Sicht, ed. Klaus Mollenhauer and C. Wolfgang Müller (Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer, 1965), 25–28.

- 3See: “Eine Film- und Lichtbildstelle für die Land- und Forstwirtschaft,” Agrarische Post, November 11, 1950, 12, https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/annoshow?call=agp|19501111|12|100.0|0.

- 4See: Thomas Brandstetter, Claus Pias, and Sebastian Vehlken, eds., Think Tanks: Die Beratung der Gesellschaft (Zurich: Diaphanes, 2010); Eva Schauerte, Lebensführungen: Eine Medien- und Kulturgeschichte der Beratung (Paderborn: Fink, 2019).

- 5See: Florian Hoof, Engel der Effizienz: Eine Mediengeschichte der Unternehmensberatung (Konstanz: Konstanz University Press, 2015), 306–313. While citations in this text are made from the German-language version, see also the English translation: Florian Hoof, Angels of Efficiency: A Media History of Consulting (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020).

- 6See: Hoof, Engel der Effizienz, 9–23.

- 7See: Hugo Süab, “Über die Abgrenzung des Begriffes ‘Beratung.’ Prof. Dr. H. Rheinwald,” Der Förderungsdienst 2, no. 2 (February 1954): 43.

- 8For the economic structure of farming in 20th century Austria, see: Roman Sandgruber, “Die Landwirtschaft in der Wirtschaft – Menschen, Maschinen, Märkte,” in Geschichte der österreichischen Land- und Forstwirtschaft im 20. Jahrhundert: Politik – Gesellschaft – Wirtschaft, ed. Franz Ledermüller (Vienna: Ueberreuter, 2002), 297–300.

- 9See: Ernst Hanisch, “Die Politik und die Landwirtschaft,” in Geschichte der österreichischen Land- und Forstwirtschaft im 20. Jahrhundert: Politik – Gesellschaft – Wirtschaft, ed. Franz Ledermüller (Vienna: Ueberreuter, 2002), 21–42.

- 10See: Helmut Engelbrecht, Geschichte des österreichischen Bildungswesens: Erziehung und Unterricht auf dem Boden Österreichs. Band 5: Von 1918 bis zur Gegenwart (Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1988), 206–207; archival record: OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allg., Volksbildung: Lichtbildwesen, K. 509, Signatur 2D2, Geschäftszahl 6436-II/10b. A.E. Filmhauptstelle. Ortspolizeiliche Vorschriften. Letter of the Österreichisches Kuratorium für Wirtschaftlichkeit, February 19, 1930, 2.

- 11Hugo Süab, “Koordinierung der Beratung,” Der Förderungsdienst 2, no. 11 (November 1961): 365.

- 12Ernst Kreuziger, “Probleme der praktischen Wirtschaftsberatung,” Der Förderungsdienst 3, no. 11 (November 1955): 250.

- 13See: Thomas Haase, “Die agrarpädagogische Bildung in Österreich” (master’s thesis, Universität Wien, 2009), 112.

- 14Süab, “Über die Abgrenzung des Begriffes ‘Beratung,’” 43.

- 15See: Süab, “Koordinierung der Beratung,” 366.

- 16Alfred Hammer, “Rückblick auf die 2. Deutschen Industriefilmtage Berlin 1961,” Film Bild Ton 12, no. 1 (January 1962): 40.

- 17See: Dankward G. Burkert, Die Tonfilmprojektion (Vienna: Bundesstaatliche Hauptstelle für Lichtbild und Bildungsfilm, 1964), 23.

- 18See: Film- und Lichtbildstelle des Bundesministeriums für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, ed., Film-Verzeichnis 1968 (Vienna, 1968), II. While the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry had occasionally commissioned films in the 1920s, back then they had left distribution to the Ministry of Education’s centralized Austrian Slide and Film Service (Österreichischer Lichtbild- und Filmdienst). See: OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allg., Volksbildung: Film, K. 487, Signatur 2D2, 4. Geschäftszahl 5234-10b/II. Errichtung einer Filmbegutachtungsstelle und eines Filmarchivs im BMU, Einlageblatt zu Zahl 5234-II-10b/30. During the annexation of Austria by national socialist Germany from 1938 to 1945, films on topics of agricultural education were mostly distributed by the central state institution Reichsstelle für den Unterrichtsfilm (RfdU), renamed Reichsstelle für Film in Wissenschaft und Unterricht (RWU) in 1940. See: Peter Zimmermann, “Landschaft und Bauerntum,” in Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 3: ‘Drittes Reich’ (1933–1945), ed. Peter Zimmermann and Kay Hoffmann (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005), 318.

- 19See: Film- und Lichtbildstelle des Bundesministeriums für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, ed., Film-Verzeichnis 1968.

- 20See: Ramón Reichert, “Die Filme des Österreichischen Produktivitätszentrums 1950–1987: Ein Beitrag zur Diskussion um den Film als historische Quelle,” Relation 7, no. 1+2 (2000): 71–135.

- 21Thanks to Filmservice International and Alexander Kammel for granting access to their collection of materials from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry’s Film and Slide Service, including screen records of the film prints. Thanks to Brigitte Paulowitz for the lead.

- 22Süab, “Über die Abgrenzung des Begriffes ‘Beratung,’” 43.

- 23See: Kreuziger, “Probleme der praktischen Wirtschaftsberatung,” 249; E. Hauer, “Betriebwirtschaftslehre und Betriebsberatung,” Der Förderungsdienst 1, no. 11 (November 1953): 231–233.

- 24See: Hanisch, “Die Politik und die Landwirtschaft,” 21–38.

- 25Hugo Süab, “Die Persönlichkeit des Beraters. Von OLR. M. Storz,” Der Förderungsdienst 7, no. 2 (February 1959): 54.

- 26See: “It’s an old joke, but worth repeating…,” Hacker News, accessed August 17, 2022, https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=567237; “Funny Consultant Jokes." "Consultant Jokes", Upjoke.com. accessed June 4, 2023, https://upjoke.com/consultant-jokes .

- 27See: Maria Fritsche, The American Marshall Plan Film Campaign and the Europeans: A Captivated Audience? (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), 43.

- 28See a clip here: “Hinterm Hof – der Feuerreiter,” Das Filmarchiv der Media Wien, accessed August 17, 2022, https://mediawien-film.at/film/96/.

- 29See: Hanisch, “Die Politik und die Landwirtschaft,” 21–35.

- 30See: Ramón Reichert, “Marshallplan und Film: Intermedialität, narrative Strategien und Geschlechterrepräsentation,” in Besetzte Bilder: Film, Kultur und Propaganda in Österreich 1945–1955, ed. Karin Moser (Vienna: Filmarchiv Austria, 2005), 470.

- 31For an example of such observational tasks (in an industrial context), see: Joachim Schätz, Ökonomie der Details: Österreichs Industrie- und Werbefilm zwischen Rationalisierung und Kontingenz (1915–1965) (Munich: Edition Text + Kritik, 2019), 120–126. For an example of the strategic use of rhetorical questions, see: Mark Broughton, “Experts in the Field: Rhetoric and Aesthetics in the Agricultural Documentary,” paper presented at the Borderlines Film Festival, Hereford, UK, April 12, 2008, 7–8, https://researchprofiles.herts.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/experts-inthe-field-rhetoric-and-aesthetics-in-the-agricultural-documentary(aa9a3afe-ada8-40cb-82e9-e6c87fec61ba).html.

- 32See: Mollenhauer, “Das pädagogische Phänomen ‘Beratung,’” 30–34.

- 33Ibid., 40.

- 34Haberl, H. “Kurzberatung mit Bildprojektion im Freien. Von Marady,” Der Förderungsdienst 8, no. 11 (November 1960): 344. See also: Haberl, H. “Anschauungsmittel auf landwirtschaftlichen Lehrschauen. Von D. Sheppard,” Der Förderungsdienst 6, no. 9 (September 1958): 279.

- 35See the loan cards for the films RUND UM DIE MILCHWIRTSCHAFT, BROT FÜR 300 MILLIONEN, and MINUS 18°C. (No filmographic information for the last two.)

- 36Mollenhauer, “Das pädagogische Phänomen ‘Beratung’,” 30.

- 37The 1968 catalogue offers over two hundred titles, with another hundred collected titles having already been taken out of circulation at that time for being too old. See: Film- und Lichtbildstelle des Bundesministeriums für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, ed., Film-Verzeichnis 1968.

- 38“Dipl.-Ing. Kreuziger, Ernst,” Friedhöfe Wien, accessed August 17, 2022, https://www.friedhoefewien.at.

- 39See: Ernst Kreuziger, “Der Film – ein wertvolles, aber oft mißbrauchtes Lehr- und Beratungsmittel,” Der Förderungsdienst 10, no. 12 (December 1962): 410.

- 40See: Armin Kniely, “Stehbild und Film in der Förderung,” Der Förderungsdienst 4, no. 5 (May 1956): 141.

- 41See: Hugo Süab, “Flanelltafel-Diapositiv – eine zweckmäßige Kombination für das Lehrgespräch. Von G. Wermser,” Der Förderungsdienst 6, no. 9 (September 1958): 280; Turek, F. “Die Flanelltafel, ein neues Hilfsmittel für Wirtschaftsberatung und Unterricht,” Der Förderungsdienst 1, no. 12 (December 1953): 268–270; Hugo Süab, “Mehr Dia-Vorträge – wann und wie? Von Dr. H. Köhler,” Der Förderungsdienst 5, no. 2 (February 1957): 57.

- 42See: Ernst Kreuziger, “Der Tonfilmprojektor – ein wichtiges Werkzeug für Lehrer und Berater,” Der Förderungsdienst 13, no. 8 (August 1965): 233.

- 43Ibid. Translated by Joachim Schätz.

- 44See: ibid.

- 45Kreuziger, “Probleme der praktischen Wirtschaftsberatung,” 249.

- 46Kniely, Armin “Stehbild und Film in der Förderung,” 142.

- 47Kreuziger, “Der Film – ein wertvolles, aber oft mißbrauchtes Lehr- und Beratungsmittel,” 409. See also: Ernst Kreuziger, “Die Anwendung visueller Hilfsmittel im Unterricht und in der Beratung,” Der Förderungsdienst 12, no. 11 (November 1964): 382–383.

- 48See: Kreuziger, “Der Film – ein wertvolles, aber oft mißbrauchtes Lehr- und Beratungsmittel,” 411; Kreuziger, “Der methodisch richtige Einsatz von Lichtbild und Film,” 51.

- 49Hoof, Engel der Effizienz, 54. For the concept of the “boundary object” as developed by Susan Leigh Star and James R. Griesemer in the context of Science and Technology Studies, see also: Star and Griesemer, “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39,” Social Studies of Science 19, no. 3 (1989): 387–420.

- 50See: Rudolf Wicha, “Landwirtschaft und Fernsehen,” Der Förderungsdienst 9, no. 7 (July 1961): 225; Rudolf Wicha, “Landwirtschaft und Fernsehen (Schluß),” Der Förderungsdienst 9, no. 8 (August 1961): 262.

- 51See: Monika Bernold, “Die österreichische Fernsehfamilie. Archäologie und Repräsentationen des frühen Fernsehens in Österreich” (diss., Universität Wien, 1997), 21, 103–109.

- 52See: Film- und Lichtbildstelle des Bundesministeriums für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, ed., Film-Verzeichnis 1968.

- 53See: Walter Godenschweger, “Internationaler Agrarfilmwettbewerb Berlin – kritisch betrachtet,” Film Bild Ton 10, no. 3 (March 1960): 44.

- 54On Direct Cinema’s foundation in television reporting, see: David Resha, “Selling Direct Cinema: Robert Drew and the Rhetoric of Reality,” Film History 30, no. 3 (Fall 2018): 32–50.

- 55See: Film- und Lichtbildstelle des Bundesministeriums für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, ed., Film-Verzeichnis1968, 47.

- 56See: Süab, “Koordinierung der Beratung,” 368.

- 57On the history of the “homestory” back to the 1960s, see: Alexandra Olivia Desirée Tait, “Homestories: Performing & Visualising the Familial in West Germany, 1961–1989. Volume I” (PhD diss., University College London, 2019), 37–38.

- 58See: Hoof, Engel der Effizienz, 365.

- 59See: Hanisch, “Die Politik und die Landwirtschaft,” 37.

- 60See: Katharina Gröning, Pädagogische Beratung: Konzepte und Positionen (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011), 13–14.

- 61See: Ulrich Bröckling, Das unternehmerische Selbst. Soziologie einer Subjektivierungsform (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2007), 26, 93, 187, 282. See also: Nicolas Rose, Inventing Our Selves: Psychology, Power and Personhood (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996).

Anon. “Dipl.-Ing. Kreuziger, Ernst.” Friedhöfe Wien. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://www.friedhoefewien.at.

Anon. “Eine Film- und Lichtbildstelle für die Land- und Forstwirtschaft.” Agrarische Post, November 11, 1950. https://anno.onb.ac.at/cgi-content/annoshow?call=agp|19501111|12| 100.0|0.

Anon. “It’s an old joke, but worth repeating…” Hacker News. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=567237.

Anon. “Funny Consultant Jokes.” “Consultant Jokes”, Upjoke.com, accessed June 4, 2023, https://upjoke.com/consultant-jokes.

Anon. “Hinterm Hof – der Feuerreiter.” Das Filmarchiv der Media Wien. Accessed August 17, 2022. https://mediawien-film.at/film/96/.

Bernold, Monika. “Die österreichische Fernsehfamilie. Archäologie und Repräsentationen des frühen Fernsehens in Österreich.” Diss., Universität Wien, 1997.

Brandstetter, Thomas, Claus Pias, and Sebastian Vehlken, eds. Think Tanks: Die Beratung der Gesellschaft. Zurich: Diaphanes, 2010.

Bröckling, Ulrich. Das unternehmerische Selbst. Soziologie einer Subjektivierungsform. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2007.

Broughton, Mark. “Experts in the Field: Rhetoric and Aesthetics in the Agricultural Documentary.” Paper presented at the Borderlines Film Festival, Hereford, UK, April 12, 2008. https://researchprofiles.herts.ac.uk/en/publications/experts-in-the-field-rhetoric-and-aesthetics-in-the-agricultural-.

Burkert, Dankward G. Die Tonfilmprojektion. Vienna: Bundesstaatliche Hauptstelle für Lichtbild und Bildungsfilm, 1964.

Engelbrecht, Helmut. Geschichte des österreichischen Bildungswesens: Erziehung und Unterricht auf dem Boden Österreichs. Band 5: Von 1918 bis zur Gegenwart. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1988.

Film- und Lichtbildstelle des Bundesministeriums für Land- und Forstwirtschaft, edited by Film-Verzeichnis 1968. Vienna, 1968.

Fritsche, Maria. The American Marshall Plan Film Campaign and the Europeans: A Captivated Audience? London: Bloomsbury, 2018.

Godenschweger, Walter. “Internationaler Agrarfilmwettbewerb Berlin – kritisch betrachtet.” Film Bild Ton 10, no. 3 (March 1960): 44–46.

Gröning, Katharina. Pädagogische Beratung: Konzepte und Positionen. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2011.

Haase, Thomas. “Die agrarpädagogische Bildung in Österreich.” Master’s thesis, Universität Wien, 2009.

Haberl, H. “Anschauungsmittel auf landwirtschaftlichen Lehrschauen. Von D. Sheppard.” Der Förderungsdienst 6, no. 9 (September 1958): 279–280.

Haberl, H. “Kurzberatung mit Bildprojektion im Freien. Von Marady.” Der Förderungsdienst 8, no. 11 (November 1960): 344.

Hammer, Alfred. “Rückblick auf die 2. Deutschen Industriefilmtage Berlin 1961.” Film Bild Ton 12, no. 1 (January 1962): 38–41.

Hanisch, Ernst. “Die Politik und die Landwirtschaft.” In Geschichte der österreichischen Land- und Forstwirtschaft im 20. Jahrhundert: Politik – Gesellschaft – Wirtschaft, edited by Franz Ledermüller, 15–189. Vienna: Ueberreuter, 2002.

Hauer, E. “Betriebwirtschaftslehre und Betriebsberatung.” Der Förderungsdienst 1, no. 11 (November 1953): 231–233.

Hoof, Florian. Angels of Efficiency: A Media History of Consulting. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2020.

Hoof, Florian. Engel der Effizienz: Eine Mediengeschichte der Unternehmensberatung. Konstanz: Konstanz University Press, 2015.

Kniely, Armin “Stehbild und Film in der Förderung.” Der Förderungsdienst 4, no. 5 (May 1956): 140–142.

Kreuziger, Ernst. “Der Film – ein wertvolles, aber oft mißbrauchtes Lehr- und Beratungsmittel.” Der Förderungsdienst 10, no. 12 (December 1962): 409–411.

Kreuziger, Ernst. “Der methodisch richtige Einsatz von Lichtbild und Film.” Der Förderungsdienst 13, suppl. no. 4 (1965): 49–51.

Kreuziger, Ernst. “Der Tonfilmprojektor – ein wichtiges Werkzeug für Lehrer und Berater.” Der Förderungsdienst 13, no. 8 (August 1965): 233–239.

Kreuziger, Ernst. “Die Anwendung visueller Hilfsmittel im Unterricht und in der Beratung.” Der Förderungsdienst 12, no. 11 (November 1964): 379–383.

Kreuziger, Ernst. “Probleme der praktischen Wirtschaftsberatung.” Der Förderungsdienst 3, no. 11 (November 1955): 249–250.

Mollenhauer, Klaus. “Das pädagogische Phänomen ‘Beratung.’” In “Führung” und “Beratung“ in pädagogischer Sicht, edited by Klaus Mollenhauer and C. Wolfgang Müller, 25–41. Heidelberg: Quelle & Meyer, 1965.

Reichert, Ramón. “Die Filme des Österreichischen Produktivitätszentrums 1950–1987: Ein Beitrag zur Diskussion um den Film als historische Quelle.” Relation 7, no. 1–2 (2000): 71–135.

Reichert, Ramón. “Marshallplan und Film: Intermedialität, narrative Strategien und Geschlechterrepräsentation.” In Besetzte Bilder: Film, Kultur und Propaganda in Österreich 1945–1955, edited by Karin Moser, 439–473. Vienna: Filmarchiv Austria, 2005.

Resha, David. “Selling Direct Cinema: Robert Drew and the Rhetoric of Reality.” Film History 30, no. 3 (Fall 2018): 32–50.

Rose, Nicolas. Inventing Our Selves: Psychology, Power and Personhood. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Sandgruber, Roman. “Die Landwirtschaft in der Wirtschaft – Menschen, Maschinen, Märkte.” In Geschichte der österreichischen Land- und Forstwirtschaft im 20. Jahrhundert: Politik – Gesellschaft – Wirtschaft, edited by Franz Ledermüller, 191–408. Vienna: Ueberreuter, 2002.

Schauerte, Eva. Lebensführungen: Eine Medien- und Kulturgeschichte der Beratung. Paderborn: Fink, 2019.

Schätz, Joachim. Ökonomie der Details: Österreichs Industrie- und Werbefilm zwischen Rationalisierung und Kontingenz (1915–1965). Munich: Edition Text + Kritik, 2019.

Star, Susan Leigh, and James R. Griesemer: “Institutional Ecology, ‘Translations’ and Boundary Objects: Amateurs and Professionals in Berkeley’s Museum of Vertebrate Zoology, 1907–39.” Social Studies of Science 19, no. 3 (1989): 387–420.

Süab, Hugo. “Die Persönlichkeit des Beraters. Von OLR. M. Storz.” Der Förderungsdienst 7, no. 2 (February 1959): 54.

Süab, Hugo. “Flanelltafel-Diapositiv–eine zweckmäßige Kombination für das Lehrgespräch. Von G. Wermser.” Der Förderungsdienst 6, no. 9 (September 1958): 280.

Süab, Hugo. “Koordinierung der Beratung.” Der Förderungsdienst 2, no. 11 (November 1961): 365–370.

Süab, Hugo. “Mehr Dia-Vorträge – wann und wie? Von Dr. H. Köhler.” Der Förderungsdienst 5, no. 2 (February 1957): 57.

Süab, Hugo. “Über die Abgrenzung des Begriffes ‘Beratung.’ Prof. Dr. H. Rheinwald.” Der Förderungsdienst 2, no. 2 (February 1954): 43–44.

Tait, Alexandra Olivia Desirée. “Homestories: Performing & Visualising the Familial in West Germany, 1961–1989. Volume I.” PhD diss., University College London, 2019.

Turek, F. “Die Flanelltafel, ein neues Hilfsmittel für Wirtschaftsberatung und Unterricht.” Der Förderungsdienst 1, no. 12 (December 1953): 268–270.

Wicha, Rudolf. “Landwirtschaft und Fernsehen.” Der Förderungsdienst 9, no. 7 (July 1961): 225–231.

Wicha, Rudolf. “Landwirtschaft und Fernsehen (Schluß).” Der Förderungsdienst 9, no. 8 (August 1961): 262–269.

Zimmermann, Peter. “Landschaft und Bauerntum.” In Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 3: ‘Drittes Reich’ (1933–1945), edited by Peter Zimmermann and Kay Hoffmann, 309–319. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005.