The Raw Materials of Celluloid Film

Wartime Economy, Educational Animation, and Film’s Plasticity

Table of Contents

Screening Propaganda

In Defense of Culture

The Raw Materials of Celluloid Film

Wholeness and Nature

The Austrian Province as Subject and Space of Action in Educational Film Practices

The Development of Educational Cinema for Schools in the Soviet Union in the 1930s

Educational Film in East Germany (GDR) in 1950–1990 in Perspective of the “Grammar of Schooling”

No Instructions, Just Some Advice

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Haid, Jonathan. “The Raw Materials of Celluloid Film: Wartime Economy, Educational Animation, and Film’s Plasticity.” Research in Film and History 5 (2023): 1–43. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/22725.

Introduction

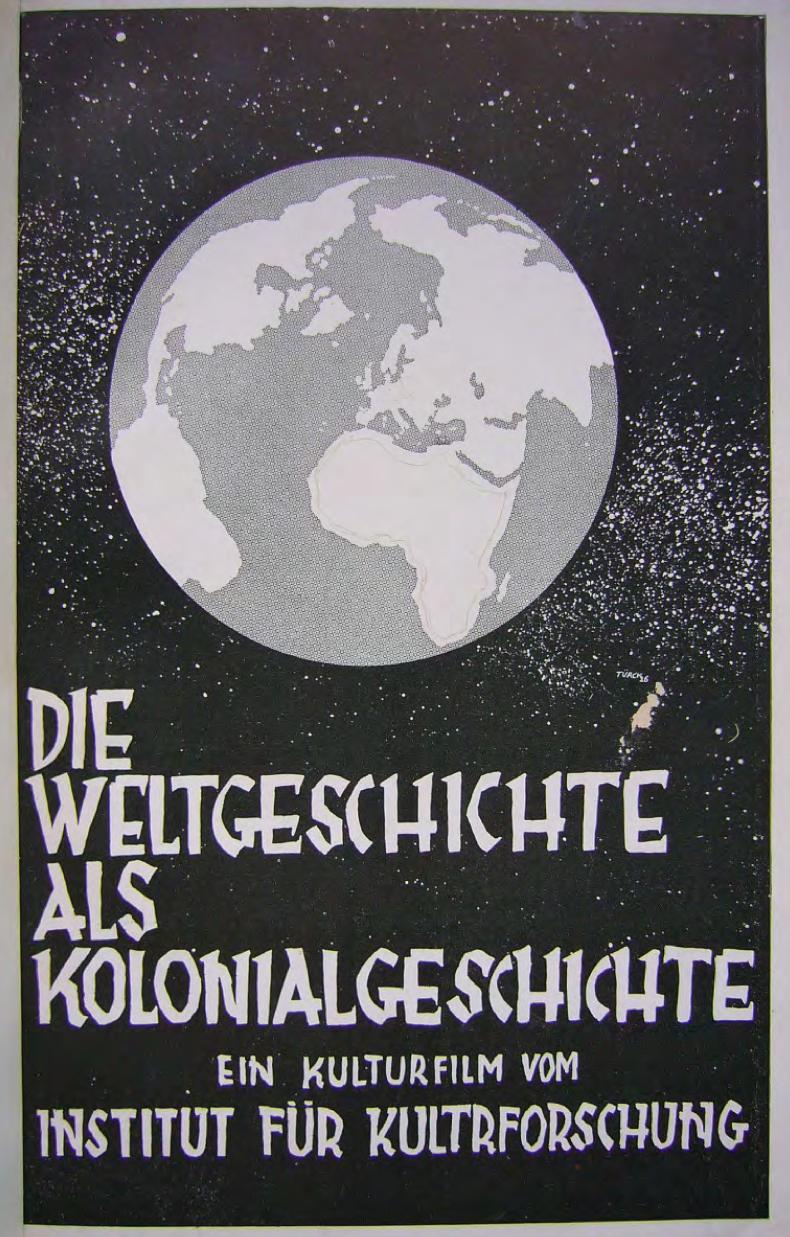

In 1925–1926, the propagandistic educational film DIE WELTGESCHICHTE ALS KOLONIALGESCHICHTE / WORLD HISTORY AS COLONIAL HISTORY (D 1926) was produced at the Berlin Institute for Cultural Research (Institut für Kulturforschung) under the direction of Hans Cürlis (1889–1982). The film aimed to strengthen support among the German population for the idea of a potential reclamation of the former colonies that Germany had lost since the end of World War I under the Treaty of Versailles. The propaganda film’s demands for colonial ownership and an independent supply of raw materials were shaped by the experience of raw material shortages during World War I. Economic and political developments such as the British naval blockade from 1914 had drastic consequences for almost all economic and production sectors of the German Reich.

But what effects did the shortage of raw materials have on the production and availability of film stock in Germany? Through what transformation processes did the procurement of raw materials necessary for the production of celluloid films go? In what geopolitical contexts was the production of celluloid film entangled, and what scientific and industrial developments preceded the search for substitutes? These questions will be explored using the example of the Agfa film factory in Wolfen near Bitterfeld, which was Europe’s largest production site for celluloid film stock. In doing so, I aim less at an institutional history but direct the focus to the raw materials from which celluloid film was mainly made: Cotton as the cellulose base, nitric acid to convert the cellulose into nitrocellulose, and camphor as a plasticizer for the pliable celluloid.1

This method follows approaches in media studies such as Richard Maxwell and Toby Miller’s book Greening the Media, which focus on the material and ecological implications associated with the production, distribution, and disposal of media technologies.2 By looking at colonial camphor exploitation in Taiwan or the industrial development of synthesis processes as a substitute for imported raw materials, celluloid film production in Germany is placed in the context of a global media infrastructure.3 Thus, I am oriented by recent studies that have shown how the logistical relationships behind the production of media technologies and their industries condition the dynamics of media knowledge circulation.4 As part of these approaches, other works have already brought celluloid film into focus: in her book The Cinematic Footprint, Nadia Bozak shows the connections between cinema and the biophysical environment, highlighting the energy and natural resources required to sustain the moving image from celluloid to digital film.5 Kay Dickinson views Hollywood film production as “supply chain cinema” and focuses on the organization of labor processes that enable a globalized film economy.6

The aim of this article is to show how the production of celluloid film stock during World War I and the interwar period was embedded in geopolitical and economic processes, industrial and scientific developments, and the colonial exploitation of natural resources. In addition, I will discuss animation techniques in the context of educational films as a specific form of knowledge transfer. As I will show, these animations are part of a cinematographic image concept made possible by the material properties of celluloid film. After contextualizing and introducing the film DIE WELTGESCHICHTE ALS KOLONIALGESCHICHTE, I turn my attention to the production conditions of Agfa celluloid film. In addition to the history of the Agfa film factory, I examine the raw materials nitric acid, cotton, and camphor in the context of wartime celluloid film production. I then return to the educational film of Hans Cürlis and focus on the connection between celluloid and animation techniques.

The educational film practice of the interwar period, I argue, benefited from the events of World War I regarding the material and infrastructural conditions of celluloid film production. War machinery and celluloid film formed a reciprocal system that had a lasting effect on the production of celluloid film and can be traced along its raw materials.

WORLD HISTORY AS COLONIAL HISTORY

The Institute for Cultural Research was founded in Berlin in 1918 by Hans Cürlis, a doctor of art history and cultural history, on the model of the institute of the same name in Vienna.7 Its self-image was that of a scholarly institution that had consciously chosen the medium of film as a means of education with mass appeal for the presentation and circulation of its research results.8 In addition to numerous ethnological, archaeological, cultural- and arthistorical educational films, the institute also produced colonialist propaganda films, including the film presented here. Shot on 35 mm, the silent film had been approved as an educational film by the Bildstelle at the Central Institute for Education and Teaching (Zentralinstitut für Erziehung und Unterricht) in 1926 and premiered in January 1927 at the Urania in Berlin, an observatory and educational institution. In 1941, the film received a new version in 16mm cine format.9

The forewords in the brochure accompanying the film were written by Theodor Seitz, president of the German Colonial Society and former governor of German colonies, the two former Reich colonial ministers Hans Bell and Bernhard Dernburg, and representatives from German industry and the Ministry of Education. They all emphasize the great importance of the “colonial question” for the people and the economy and also point out the importance of bringing propaganda in this regard to young people in particular through educational work in schools.10 The brochure makes it clear that the educational film has already been designed for use in educational institutions such as the Berlin Urania or for school lessons in combination with a contextualizing lecture.

In five acts, the film addresses Europe’s relationship to the tropics and their raw materials, reconstructs a supposedly cultural-historical tradition of colonization in Africa, and ends with an analysis of the economic processes surrounding the colonial trade in raw materials and its influence on German industry. Live-action footage presents the arrival of various colonial goods such as mahogany logs, palm oil, natural rubber, or cocoa beans at German shipping ports. The depiction of these goods is intended to illustrate the extent to which diverse everyday products depend on the availability of colonial raw materials: from the rubber in car tires and medical gloves to cotton clothing or the palm oil in soap. With explicit and emotional images, the film reminds us of the drastic consequences that the lack of raw materials during World War I had caused: moldy food due to a lack of rubber gaskets, or babies who had to be wrapped in newspaper instead of diapers.

Two other acts are devoted to a historical narrative about the colonization of Africa, which is, according to the film, part of a millennia-old cultural history of trade and the establishment of trade routes, beginning with the ancient Phoenicians. The colonial history of the modern era, the film argues, is merely part of a cultural-historical tradition of opening up and exploring the continents. The remaining part of the film is devoted to the negative consequences that the loss of the colonies allegedly had on the German economy and labor market. It is shown to what extent imports of raw materials and goods from the colonies could have met Germany’s needs as a growing industrial nation if the colonies had still been under German control. Calculations show the high level of import duties Germany has to pay instead, to import all the goods it depends on. The demanded claim to the colonies and their goods is legitimized, among other things, by the investments in infrastructures – such as railroad networks, roads, schools, and health care systems – that had been made in the colonies since 1884, the profits from which would thus be due to Germany.

The AGFA Film Factory

The film practice of Hans Cürlis and many others depended on the availability of negative film for shooting as well as positive film for the distribution of the finished films. Probably the most important production facility for celluloid film stock in Germany was the film factory of the Actien-Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation (Corporation for Aniline Production), or Agfa for short, in Wolfen near Bitterfeld. Founded in 1873 from the merger of a dye factory in Berlin-Treptow and the Berlin-based Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation (Company for Aniline Production), Agfa was initially dedicated to the manufacture of dyes and products for the pharmaceutical and chemical industries. In 1889, the company began selling photographic developers and expanded its offerings a few years later to include dry plates and roll film. The production plant in Treptow was supplemented by the film factory in Wolfen, built in 1909, which eventually heralded the well-known success story of Agfa (and later ORWO) film stock.11 In its first year of production, 1911, Agfa recorded the manufacture of 5,679,846 meters of celluloid positive film, 167,466 meters of celluloid negative film, and 61,909 meters of safety film made of cellulose acetate. After various expansions, the film factory reached a production capacity of 102,135,758 meters of positive film, 14,475,713 meters of negative film, and 393,806 meters of safety film in 1925, when Cürlis was shooting the film. The Agfa plants in Wolfen were thus the largest production facility for film stock in Europe and the second largest in the world after Eastman Kodak.12

The main raw materials for the production of celluloid film base were cotton, nitric acid, and camphor.13 After the start of World War I, however, the British naval blockade sealed off Germany from international trade and the raw materials markets of its colonies from 1914 onward. Not only did this prevent the export of their own manufactured goods, which gave other industrialized countries an advantage in the world trade market, since the exclusion of German products left gaps in the market. Rather, important raw materials, on which a large part of domestic production was based, could for the time being only be imported via the neutral neighboring states. These included, for example, iron ore from Sweden, Norwegian nickel, as well as foodstuffs from the Netherlands and Denmark. Nevertheless, as the war progressed, the supply of important goods became increasingly difficult for Germany, which apart from coal, lime and potash had hardly any raw material deposits of its own.14

In addition to the civilian need for production goods, some raw materials were also indispensable for the buildup and maintenance of the war machinery. These included iron, steel, various non-ferrous metals, petroleum, fats, rubber, textile fibers, numerous chemicals, and many others.15

Nitric Acid

One raw material played a special role in the wartime economy of World War I, as it was essential for three different fields of application: saltpeter. As a source of nitrogen, saltpeter was of enormous importance as a fertilizer for the food supply. At the end of the nineteenth century, there were already warnings of impending famines if the natural saltpeter deposits were to be exhausted one day. Nitric acid, obtained from saltpeter, was also essential for the production of ammunition and explosives. The shortage of nitric acid became apparent shortly after the start of the war in the form of an impending scarcity of ammunition. Finally, nitric acid was an indispensable ingredient for converting cotton or wood pulp into nitrocellulose, from which, with the addition of camphor, the plastic material celluloid and subsequently film base were produced.16 Until World War I, saltpeter in the form of sodium nitrate was imported almost exclusively from Chile, where the world's largest deposits were located. “The source of raw materials in Chile,” recalled chemist Fritz Haber in a 1921 lecture at the Academy of Sciences in Berlin, “threatened to dry up in such a short time, given the rapidly increasing annual demand, that other sources had to be found as a matter of life and death.”17 But before this case of depletion of natural saltpeter deposits could occur, Germany was abruptly cut off from saltpeter supplies from Chile with the onset of the British naval blockade, and the need for an alternative source was more urgent than ever.

While it was still possible to seize large quantities of nitrate supplies from German and Belgian ports at the beginning of the war, consumption very soon exceeded expectations: Whereas the German Army’s monthly requirements were initially estimated at 600 tons of explosives and 450 tons of smokeless powder, by August 1915 the demand was already expected to reach 10,000 tons, and in 1916 as much as 20,000 tons of explosive material per month.18

The Kriegsrohstoffabteilung

Walther Rathenau, an industrialist and later foreign minister of the Weimar Republic, already pointed out the problem of raw material supply at the beginning of the war. In joint conversations, Rathenau explained to the Minister of War, Erich von Falkenhayn, that the availability of raw materials was the most important factor in the forthcoming organization of the war economy. Solving the raw material problem, the War Ministry decided, was critical to the success of the war. In August 1914, an institution was created in the War Ministry to organize the procurement and administration of raw materials essential to the war effort. Rathenau was entrusted with the establishment and management of this agency, which was given the name Kriegsrohstoffabteilung (War Raw Materials Department), or KRA for short.19

The KRA was an ambitious undertaking of great scope: After all, the German Reich’s economy, which had previously been widely ramified and highly dependent on international trade, was to be transferred to an isolated and largely self-sufficient economic system.20 In a first step, KRA inventoried the few raw material deposits available in Germany and, by interviewing industrial companies important to the war effort, determined what quantity of raw materials was needed when, where, and for what purpose. In occupied Belgium, whose port warehouses were richly stocked with goods, raw materials such as saltpeter, cotton, and natural rubber were confiscated. At the same time, research into alternative processes and materials was pursued to achieve greater independence from the original imported materials through substitutes.21 In addition, recycling processes were tested to reduce the need for raw materials.

To meet the administrative challenges of this new wartime economy, separate associations were formed for each group of materials. Those were organized as publicly traded companies and were composed of representatives of the respective industry, but were subject to the control of the KRA. From the War Metal Corporation and the War Wool Corporation to the War Leather Corporation and many others, the companies were responsible for the distribution of the various goods to the processing industries.22 The War Chemicals Corporation (Kriegschemikalien AG) was founded in 1914 and was made up of the three most influential chemical companies in Germany: Badische Anilin- und Sodafabrik (BASF), Bayer, and Agfa, which not only maintained a factory in Wolfen for the production of photographic film material, but also a large dye factory where chemicals were processed. The most urgent concern of the War Chemical Corporation was to find a solution to the acute shortage of nitric acid. More precisely: to provide the infrastructure for large-scale industrial production of nitric acid as quickly as possible.

Around 1900, Wilhelm Ostwald, one of the founders of physical chemistry, had already been researching a process in which nitric acid could be obtained by oxidizing ammonia. At the Lothringen mine in Gerthe, now a district of Bochum, he maintained a small plant in which nitric acid was produced industrially using the Ostwald process, with the ammonia coming from the mine's coking plant. Ostwald drew attention to his plant, but the KRA followed Fritz Haber’s advice. Haber had developed a process for ammonia synthesis and implemented it on an industrial scale at BASF, together with his colleague, chemist and industrialist Carl Bosch. Haber proposed to KRA to expand the BASF plant in Oppau near Ludwigsburg, where ammonia was already produced using the Haber-Bosch process. The ammonia synthesized in this way was to be oxidized to nitric acid according to the Ostwald process. Although corresponding processes for synthesizing nitric acid were not yet fully developed at BASF, Haber’s project proposal was prioritized and BASF received millions in government subsidies. As part of this “saltpeter promise” (Salpeterversprechen), as the contract between Carl Bosch and the Supreme Army Command is known, Bosch was obliged to enable the large-scale industrial production of nitric acid and thus end the crisis. In the spring of 1915, the saltpeter plant in Oppau began production, and shortly afterward other companies, including Bayer and Agfa, also adapted BASF’s process.23

The Film Factory during World War I

Agfa signed its contract with KRA for the construction of a saltpeter factory in July 1915 and a second one in October of the same year. Both factories were designed to produce about 3,000 tons of saltpeter per month and were to remain on call to the army administration for 10 years after the end of the war.24 While the contract to produce saltpeter kept the plants at Agfa’s dye factory busy, the film factory next door was suffering from the effects of the war. On the one hand, there was a lack of trained personnel, as more and more workers were drafted into military service. On the other hand, the shortage of raw materials made itself felt very soon. A look at the factory's production output in 1914 illustrates the impact that the start of the war had on the manufacture of film material: In the first seven months before the war began, the film factory produced 20,739,201 meters of positive film and 2,787,204 meters of negative film made of celluloid, as well as 1,383,180 meters of safety film made of cellulose acetate. In the remaining five months after that, a total of 4,152,700 meters of film were produced, i.e. just under a quarter of the average production output.25

In 1915, production declined further as the remaining stocks of nitrocellulose were used up and no more deliveries were possible. Agfa had already begun experimenting with cellulose made from wood instead of cotton as well as an acid mixture with reduced nitric acid content to compensate for the lack of raw materials. There was also increased research into films made from cellulose acetate, which did not yet approach celluloid films in terms of quality. However, these measures could not counteract the acute shortage of nitrocellulose. The situation was only remedied by the KRA, which released new quantities of nitrocellulose from the seized stocks for the Agfa film factory at the end of 1915. In fact, the military had developed a special interest in photographic material in the context of aerial reconnaissance.26

World War I was characterized, among other things, by “information technology warfare,”27 which reordered the perception of war, shifting it from the human senses to the use of media technologies. In addition to acoustic technologies such as the sound locator (Richtungshörer) co-developed by Erich Moritz von Hornbostel and Max Wertheimer, aerial photography was used as part of military reconnaissance.28 Landscape films taken from airplanes produced individual photographic images from which the wartime landscape could be mapped like a collage.29 The change in perspective from horizontal to bird's-eye view that photographic capture from the air meant required a physiognomic reading of the wartime landscape in order to decipher camouflage techniques and develop counter-strategies of camouflage.30 Agfa developed and produced a film stock specially adapted for this use in the airplane and received personnel releases from the army service for this purpose, as well as new supplies of cellulose nitrate to maintain production in the factory.31

In the following years, the demand for film stock and the production capacity of the film factory continued to increase. Agfa cites four reasons for this:

(1) The economic isolation sealed off Germany not only from the international raw materials market but also from imports from the foreign film industry, which affected both movie productions and the supply of film stocks. Kodak also dominated the market in Germany, but after the import ban, a gap had opened up in the market that Agfa, as the most important German production company, was largely able to fill on its own. As more raw materials such as nitrocellulose were released by the KRA, the film factory was able to increase its production load and by 1916 had already returned to its pre-war level.32

(2) Due to the war-related lack of trained personnel and poor maintenance of projection equipment, the film prints were subject to much greater wear and tear than in peacetime. According to Agfa, this led to a considerable increase in the demand for film stock, which the film factory could not always fully meet. Although the necessary raw materials were provided by KRA, Agfa repeatedly reported a shortage of raw materials that affected production capacity.33

(3) Increased demand for film stock also resulted from the establishment of the Bild- und Filmamt (BuFA) in January 1917. As the mood among the German population continued to deteriorate due to the ongoing war and the insufficient supply of essential goods, and propaganda measures abroad failed to have the expected effect, government agencies and the military began to take an interest in the medium of film as a propaganda tool. The BuFA was subordinate to the Supreme Army Command and was founded with the aim of ensuring the supply of propagandistic images and film material to domestic and foreign audiences. In addition to the production of propaganda films, the agency also took over the distribution of the films to the numerous cinemas on the front line.34

(4) While Agfa’s film factory was already producing custom-made films for use in aircraft for the military, and BuFA’s activities were boosting the production of film stock, another order from the army ensured increased utilization of the factory facilities: Agfa had undertaken to produce celluloid lenses, an important element for gas masks, which were becoming increasingly important due to the growing use of chemical warfare agents. These lenses were small round celluloid discs inserted in front of the outer lenses of the gas masks to absorb breathing moisture. They were intended to prevent the lenses from fogging up and had to be replaced over and over again. Agfa’s production facilities, where celluloid film was cast on large drums, already provided the technological infrastructure to produce the celluloid lenses. For this purpose, a large part of the factory and the available raw materials were claimed. While Agfa celluloid films rotated through the cameras of the BuFA film crews recording the war action, the same manufacturer’s celluloid lenses ran through the gas masks through which the wartime participants on the other side of the camera experienced the war. For Agfa, celluloid lenses and celluloid films not only shared raw materials and means of production, they also merged in the statistics. In 1917, the film factory produced about 81 million celluloid lenses. In the annual reports, this is converted into approximately 21 million meters of film stock and included in the total production of 44,266,910 meters of cinematographic film.35

When demand for celluloid lenses slowly declined in 1918, celluloid film could be produced again instead, and production reached record levels once more. As late as 1918, the War Ministry urged Agfa to increase the production capacity of the film factory by expanding the facilities again in order to meet the needs of the Supreme Army Command. In return, the supply of raw materials was ensured.36

Cotton

As a result of the trade blockade, Germany also suffered from a shortage of cotton during World War I, which was imported from its own colonies, but mainly from the United States. The cotton shortage did not only affect the textile industry. As with nitric acid, both the production of explosives and the production of celluloid films depended on cellulose.37 Nitrocellulose could therefore only be produced from wood pulp in Germany during wartime. However, the substitution of cotton cellulose with wood pulp led to problems in the nitriding process due to impurities such as resins, fats, or hemicellulose, which could have a negative impact on the quality of the cellulose and required adjustments in the processing methods. In addition, the consumption of the important resource nitric acid for the nitration of cellulose was 20% higher for wood pulp than for cotton cellulose – but the yield of nitrocellulose was 15% lower, which is why wood pulp was hardly cheaper as a substitute for cotton. Finally, celluloid waste made from wood pulp was not recyclable in the same way as that made from cotton cellulose, because the celluloid became brittle more quickly after recycling so some of this waste could only be used to recover camphor.38

Camphor

Camphor is an essential oil extracted from the wood of the camphor tree. As a final product, camphor appears as a colorless or white powder or in pressed form as crystals. In terms of chemical properties and composition, camphor corresponds to turpentine oil. In the nineteenth century, the camphor tree grew mainly in Taiwan, as well as in the south of Japan and in the Chinese coastal areas, but due to its economic importance, it was also cultivated in many other countries outside this natural occurrence. In addition to camphor from Japan and Taiwan, which dominated the market at this time, camphor from China was also sold but was considered inferior due to numerous impurities.39

The economic relevance of camphor increased immensely, however, with the invention of celluloid. John Wesley Hyatt had experimented with collodion in his search for a substitute for ivory billiard balls. Collodion, a nitrocellulose solution, was known as a base for photosensitive emulsion in the collodion wet plate, a photographic process developed by Frederick Scott Archer. Hyatt observed that the drying collodion produced a horn-like layer, but it was far too brittle for further processing. But by adding camphor to nitrocellulose as a plasticizer, Hyatt was able to produce a moldable and pliable thermoplastic, which he patented under the trademark Celluloid and successfully marketed from 1871. The plastic compound celluloid turned out to be a highly variable material that could be colored as desired, shaped in a wide variety of ways and produced with different surface textures or varying hardness. The flexibility of the new plastic suddenly changed the industrial production of consumer goods, as the design possibilities significantly exceeded the limitations of traditional materials such as wood, metal, stone, and the like. The field of application was very wide: dentures, plates, cutlery handles, combs, brushes, cufflinks, piano keys, or various pieces of jewelry as an imitation for ivory, malachite, amber, coral, tortoiseshell, just to name a few.40

As a non-substitutable element in the ever-growing celluloid industry, camphor from Japan became a sought-after commodity that could barely meet global demand. While Japan exported about 283 tons of camphor in 1868, this quantity was almost fourteen times higher in 1887, at nearly 3918 tons.41 To meet the growing demand, Japan relied on intensive exploitation of the forest stands, which greatly reduced the occurrence of the camphor tree and in some places almost wiped it out. Although attempts were made to counteract the deforestation of the camphor tree stands by replanting, the slow-growing trees did not promise renewed yields for decades. The dwindling of camphor trees eventually led to a gradual decline in exports again beginning in 1887 and to unstable and rising camphor prices in the early 1890s.42

Similarly, camphor trees in Taiwan were harvested under Chinese rule, with deforestation pushing further and further into areas of the interior inhabited by indigenous people. This led to bloody clashes in the second half of the nineteenth century between the indigenous population and the Chinese administration, which responded to the resistance with military retaliation.43 As a result of the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan had taken over Taiwan as a colony from 1895. Military suppression of indigenous resistance to the colonialist camphor economy continued under Japanese rule, culminating in systematic bombardments of indigenous residential areas between 1917 and 1926. It was not until the early 1930s that the disputes came to rest.44

By taking over Taiwan as a colony, Japan had not only incorporated the strongest competitor in the camphor business but at the same time expanded its own dwindling camphor tree stocks by the largest deposit in the world. Although the camphor tree was planted in other regions of the world because of its economic value, it took many years before it could be cultivated profitably, so Japan held the monopoly position in the international camphor business. In order to also control national trade and prices, Japan declared the camphor industry a state monopoly in Taiwan in 1899 and in Japan in 1903. This monopolization led to higher camphor prices for the Western industrialized countries, with the U.S., Germany, France, and England as the main buyers.

At the same time, it became increasingly difficult for Japan to meet the high demand of global celluloid production, as the camphor tree stocks of Taiwan’s coastal regions were harvested over time, as was already the case in Japan. The development of new camphor areas was opposed by the aforementioned resistance of Taiwan’s indigenous population.45 In addition, a groundbreaking invention at the end of the nineteenth century created a completely new field of application for the plastic: celluloid film as a base for photo emulsion gave rise to a new, rapidly growing industry in the form of cinematography, which in turn placed demands on Japan’s camphor supplies. The unsustainable exploitation of natural camphor resources and the growing demand from the celluloid (film) industry meant that camphor became a scarce commodity at the beginning of the new century.46

To escape trade controls and high prices of the Japanese monopoly, research had been conducted since the end of the nineteenth century in camphor-consuming industrialized countries on synthesis processes, all of which were based on the molecularly related turpentine oil. A viable synthesis process would still depend on the availability of turpentine oil, which could be obtained from certain types of pine, but it was hoped that the celluloid industry would become more independent. Even with the high prices of natural camphor, most synthesis processes were too expensive or inefficient to make mass production economically viable. However, a solution was found by Chemische Fabrik auf Actien (formerly E. Schering), a Berlin pharmaceutical company that had emerged in 1871 from a Charlottenburg pharmacy founded by Ernst Schering. In 1905, the company (referred to as Schering) succeeded in patenting a synthetic camphor whose properties were hardly inferior to those of natural camphor. The real achievement was to make the synthesis process so efficient with minimal raw material requirements that it was economically viable and could compete with Japan’s natural camphor. To counter competition from synthetic camphor, the Japanese monopoly again lowered prices from 1907, but Schering had already established itself on the international camphor market thanks to the patent. Schering’s synthesis process transformed Germany from the second largest importer of natural camphor to the leading exporter of synthetic camphor.47

When the administration of raw material supplies was organized by the KRA during World War I, Schering, as Germany’s leading producer of synthetic camphor, had the task of making the German industry completely independent of imported natural camphor. Like most industries, Schering had also to contend with a lack of workers who were drafted for military service. More serious, however, was the availability of turpentine oil, which came to a virtual standstill due to Germany’s economic isolation. Only from certain species of pine could turpentine oil of the necessary quality be obtained and until the end of trade relations, a large part of it came from France, Russia, and the United States. At the same time, all export sales of synthetic camphor, which had been crucial for Schering’s economic existence, ceased. From 623 tons in 1913, Schering’s camphor production fell to 3 tons in 1918 by the end of the war. Since the synthetic camphor business was no longer possible, Schering had to close the Berlin camphor factory in Charlottenburg.48

It was not until major investments were made after the war, which led to the opening of a new plant in Eberswalde and the takeover of Rheinische Kampferfabrik GmbH in Dusseldorf, that Schering succeeded in becoming the leading producer of synthetic camphor on the world market again in the 1920s. By 1924, Schering had returned to its pre-war production level of 600 tons. In 1930, half of the U.S. demand was supplied by Schering. At that time, camphor was Schering's most important product – a business that was very closely interwoven with the celluloid industry.49

Celluloid and Plastic Image

Using the example of British film pioneer Cecil Hepworth, media scholar Pansy Duncan has shown how special effects in early film led to the constitution of a new (aesthetic) register of the photographic image. Duncan shows how this transformation from the indexical topos of truthfulness of nineteenth-century photography to a conception of the image characterized by manipulation and illusion, which she calls plastic image, was brought about primarily by the plastic celluloid and its material properties.50

Decades before celluloid became an enabler for film media technology, the thermoplastic, as noted before, was already widely used in the industrial production of a wide variety of goods due to its plasticity. The flexibility and suppleness of celluloid were ultimately the decisive properties that led to the invention of celluloid film as a carrier for light-sensitive photographic emulsions in 1889. The supple and at the same time durable celluloid film was not only the technical prerequisite for the invention of cinematography – because without a rollable and transparent film, no cinema would have been possible. Likewise, the malleability of celluloid film opened up techniques of editing, namely cutting apart, reconfiguring, and reassembling different sections of film.51

Early special effects such as substitution splicing and stop-motion built on the editing practice and were used by pioneers such as George Meliès to bring illusionistic phantasms to the screen. When the Scottish queen’s head is cut off in THE EXECUTION OF MARY STUART (UK 1895), a short film released in 1895, it is substitution-splicing that replaces the (male) actor’s body with a puppet from one frame to the next. For Duncan, the plastic image as a cinematographic image conception has a double meaning: the pliable plastic celluloid was the material prerequisite for the aesthetic manipulation and plasticity of the cinematographic image.52

The examples Duncan cites for her argument, Méliès, Hepworth, and THE EXECUTION OF MARY STUART, produced by Thomas Edison, are representatives of the trick film genre that was particularly popular in early cinema. This genre was characterized by the exploration of special effects such as the stop trick, slow and fast motion, or stop-motion, with the goal of manipulating and transforming the camera’s images of reality in a phantasmal, surreal, or spectacular way.

A broader understanding of trick film that goes beyond this genre designation was represented by Hans Ewald, director, and producer of technical, scientific, and commercial animated films. In the 1924 anthology Das Kulturfilmbuch (The Cultural-Film Book), Ewald published an article titled “Der Trickfilm,” in which he discussed the possibilities of presenting and conveying various knowledge content in the educational film. For Ewald, a trick film is simply one “that is made with special tricks and artifice.”53 According to Ewald, slow motion and fast motion are therefore as much a part of the repertoire of trick film as drawn animation films or stop-motion shots of cut-out figures, letters, and shapes. (Thus, he goes beyond the usual German meaning of “Trickfilm” which is usually translated as “animation” and towards the early cinema stress on the ‘trick’ as a filmic special effect.)

For stop-motion animation, a certain arrangement of shapes, for example, the outline of England and its colonies on a map in DIE WELTGESCHICHTE ALS KOLONIALGESCHICHTE, was filmed from above, with the film reel not running continuously during the shoot. Instead, each photograph was taken individually and the position of the shapes was changed after each photographic exposure, so that movement and transformation of the shapes became visible during projection.

In this example, the land areas of the English colonies move across the screen and puzzle together to form a rectangle that visualizes the total area of the English colonies. The same happens with France and Germany and their colonies. The stop-motion animation – a frequent mode of animation for such visualizations at the time – transforms the land areas of the colonies into three comparable rectangles; the “simultaneity of the presented”54allows viewers to grasp the proportions of the areas at a glance and to relate them to one another. The visual argumentation of this arrangement conveys the message: Germany was already “behind the other powers” before it lost its colonies to the “Versailles Dictate.”55

For Ewald, the trick film, with its various techniques, offers a unique opportunity to present “scientific problems [...] to the audience in inexhaustible abundance.”56 Even though Ewald’s concept of the trick film in the service of educational film differs from the trick film genre, it ties into the idea of a plastic, therefore malleable image that found its origin in the plastic material celluloid.

Apart from the stop-motion techniques used by Cürlis, celluloid and its material properties were also important for the development of animation technique, but not in the context of the editability of flexible film material, but as a working medium for drawn animation. Where Ewald describes the production of each change in the drawing as a laborious and lengthy process, cel animation (derived from celluloid) brought great savings of labor to the animation process. Instead of having to redraw the entire scene for each shot, including the motionless parts, cel animation involved drawing each object in the frame onto its own transparent celluloid sheet (a so-called cel). All cels were layered together on a background and in combination resulted in the image composition. The individual cels allowed the animators to manipulate and move the respective objects individually. For example, while the position of some cels remained motionless for several frames, other cels could be moved or replaced with new drawings. Again, it was the material properties of the plastic celluloid that made it possible to produce thin, transparent, colorless, and, above all, flexible sheets, which were the basic prerequisite for cel animation.

Educational Film and Animation Techniques

In addition to explanatory intertitles, it is mainly animation tricks that alternate with live action footage in DIE WELTGESCHICHTE ALS KOLONIALGESCHICHTE. Animated diagrams, maps, or other representations illustrate the facts and arguments of the film. The schematic overview of an economic cycle, for example, is intended to show the positive impact that potential colonial ownership would have on national prosperity: Capital investments in the colonies’ administrations and infrastructures would lead to regular imports of raw materials. Germany, on the other hand, would have secure sales markets for the export of its goods, whereby more wealth would flow back into the economy. This supposedly endless economic cycle would eventually support reparation payments.

For the silent film, which is limited to the visual and cannot rely on an audible voice as a medium of communication, these trick animations allow the presentation of complex relationships. In DIE WELTGESCHICHTE ALS KOLONIALGESCHICHTE they are a significant form of knowledge transfer. Trick animations were of great importance for educational film practice. Especially in colonialist propaganda films, animated maps served to stabilize constructions of national identity. Through the symbolic visualization of infrastructures such as railroad networks and production routes, they also underpinned narratives of Western European “civilization” of the African continent.57

The importance of trick techniques for educational film practice can be traced in further contributions to the already cited anthology Das Kulturfilmbuch. For example, Felix Lampe, head of the Bildstelle at the Central Institute for Education and Teaching, points out the advantage of animation techniques and their suggestive potential over live-action footage regarding geographical representations: “[The] illustration of geographical developments by cinematographic images of reality is only possible in exceptional cases; mere hypotheses are faked as realities with staged images or animated drawings in a way that the less sensually descriptive language fortunately does not do.”58

Not only does the process of cartography itself suggest a high degree of credibility since it is associated with exact measurements. Ralf Forster further argues that animated maps in nonfictional films of this time also derive their evidential power from the alternating presentation with live-action footage, which is experienced as a representation of reality qua their photographic production process. Forster traces this media arrangement back to geographical photo series that already fulfilled political functions around 1900, such as lantern slide lectures of the German Colonial Society. In the projection of geographic slide series, drawn (or photographed) maps were displayed alternately with photographs of the covered areas. During the projection of geographic slide series, drawn (or photographed) maps were shown alternately with photographs of the areas covered. This reciprocal network of meanings consisting of photographic and cartographic forms of representation was continued in educational films of the 1920s and thus tied in with already existing habits of reception.59

Conclusion

Four years after the founding of the Institute for Cultural Research, Oskar Kalbus, scientific advisor to the Ufa-Kulturabteilung (cultural department), evaluated the institution’s achievements in the following words: “At the Institute for Cultural Research, completely new types of film were worked on for the first time in the fields of cartographic-statistical trick film […] and completely new scholarly forms of expression were produced out with the help of the living image.”60

DIE WELTGESCHICHTE ALS KOLONIALGESCHICHTE is one of the institute’s educational films that rely on animated maps and graphs for the didactical transfer of their content. Trick animations are an elementary component of this educational film practice. The cartographic and diagrammatic presentation techniques support social and political narratives about the supposed impositions of the Treaty of Versailles. They visualize and stabilize the messages of the film. The characterization of these stop-motion animations in German educational film publications as techniques of the trick film points to the special effects of the trick film genre as their historical origin. Hence, the animated representations embody the concept of an aesthetically manipulable “plastic image” that sprang from the editing practices of the trick film genre. The flexible and malleable plastic celluloid was not only an enabler for cinematographic moving images and the possibility of editing them but also gave rise to a new animation technique in the form of thin, transparent plastic sheets, the cels.

In Germany, the production and availability of celluloid film as a material medium benefited from the events of World War I, as did the Agfa film factory. The trade blockade enabled Agfa to dominate the German market and replace Kodak as market leader. Military orders such as the celluloid lenses and special productions for aerial reconnaissance enabled the film factory to secure sales. The Agfa dye factory, in turn, had built factory facilities for the production of nitric acid with the help of generous subsidies. Last but not least, the interest of the Supreme Army Command in film as a propaganda medium ensured an increasing demand for film stock through the activities of the BuFA. These versatile links between the military and the products of the chemical and celluloid film industries, as well as the administrative system of the KRA, ultimately gave Agfa access to important raw materials, such as nitrocellulose.

In 1918, the film holdings of the BuFA were absorbed into the Universum Film AG (Ufa) and examined by Felix Lampe, head of Bildstelle of the Central Institute for Education and Teaching, to determine their suitability as educational films for use in schools. The heritage of the BuFA thus formed the basis for many German educational films of the interwar period.61 Likewise, the use of film and photography in the context of military reconnaissance strategies points to the deep relationship between film and World War I. Through looking at the raw materials of celluloid film, it becomes clear that this relationship is not limited to the content and epistemological levels of the medium alone.

The celluloid lenses for the gas masks are a result of the material intertwining of celluloid film and the war machinery of World War I. Both shared production branches and raw materials. Gun powder had been replaced by smokeless powder whose main constituent was nitrocellulose, one of the basic ingredients for celluloid. The celluloid factories already had the equipment to process nitrocellulose and also had sufficient safety measures, since they worked with the highly flammable celluloid. Consequently, the step was not far, and the celluloid industry temporarily took over the production of smokeless powder based on nitrocellulose.62 Thus, the celluloid industry and the military were equally motivated to press ahead with the search for substitutes for the raw materials cotton and saltpeter, which had become rare. The use of wood pulp instead of cotton as the basis for nitrocellulose and the development of industrial factory facilities for the mass production of nitric acid thus not only solved the munitions crisis but also ensured the availability of celluloid films.

Even before the trade blockade, the question of synthetic substitutes for natural resources such as camphor or saltpeter from Chile was raised, as these either threatened to run dry at some point or, in the case of camphor, there was a desire to become independent of the Japanese monopoly. World War I forced the rapid development of a viable synthesis process for nitric acid through cooperation between the military, government, science, and industry. This development had long-term consequences, as this process endured and natural saltpeter from Chile gradually lost importance on the international market. Schering’s camphor synthesis also eventually outstripped the Japanese monopoly. Despite higher costs, the Agfa film factory switched back to natural camphor in 1922 because the quality of the synthetic substitute as a plasticizer did not yet match that of natural camphor.63 Similarly, wood pulp could not match cotton quality in celluloid film production. In 1922, the film factory had a consumption of 1200 tons of cotton.64 In 1924/25, Germany ranked third in world consumption with 5.67%, behind the U.S. and Great Britain, with the very largest share of imported cotton coming from the U.S..65

Cürlis’ propagandistic educational film DIE WELTGESCHICHTE ALS KOLONIALGESCHICHTE is affected by the experiences of raw material scarcity and the war economy during World War I. The film argues for a renewal of colonial ownership to ensure secure access to imported raw materials. The mediation strategy is largely based on trick animations that accompany the live-action footage. As plastic image, this media practice springs from the material properties of celluloid film. But the availability of the raw materials that made this educational film practice possible changed with the developments of World War I. Not only did Agfa Filmfabrik’s market position improve significantly – a development that also benefited the German educational film industry through contractually secured exclusive prices.66 The celluloid film industry has also become independent of Chilean saltpeter imports thanks to the technical innovation push in the synthesis of nitric acid. The same applies to the dependence on imported camphor, although natural camphor was preferred for quality reasons despite the cheaper synthetic camphor. The media use of celluloid film, and thus the educational film practices of the Institute for Cultural Research, are thus themselves linked to practices of colonial exploitation of natural camphor in Taiwan. Wood pulp was also unable to establish itself as a substitute for cotton cellulose in the celluloid film industry. The production of over one hundred million meters of celluloid film annually at the Agfa film factory was thus dependent on the constant availability of cotton. The former German colonies would only have been able to meet this demand to a limited extent, which is why the dependence on U.S. imports would still have persisted.67

Despite partial independence of raw material imports through industrial synthesis processes, the demand for colonies and colonial raw materials formulated in Hans Cürlis’ educational film was itself closely interwoven with the procurement, trade, exploitation, and processing of internationally imported raw materials. Equally interwoven with the material celluloid is the aesthetic presentation of the film in the form of trick animations.

- 1‘Raw materials’ are understood here as a historical category associated with the (often) colonial exploitation of supposedly idle, ‘raw’ and ‘unprocessed’ resources. This exploitation, however, was preceded by discursive and technical transformation processes in which materials were successively transformed into raw materials and appropriated. See: Naomie Gramlich, “Mediengeologisches Sorgen. Mit Otobong Nkanga gegen Ökolonialität,” Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft 13, no. 24 (2021): 68–69.

- 2Richard Maxwell and Toby Miller, Greening the Media (Oxford: University Press, 2012).

- 3See: Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, Signal Traffic. Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures (Urbana/Chicago/Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2015).

- 4Matthew Hockenberry, Nicole Starosielski, and Susan Zieger, eds., Assembly Codes. The Logistics of Media (Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2021); Monika Dommann, “Handling, Flowcharts, Logistik. Zur Wissensgeschichte und Materialkultur von Warenflüssen,” in Zirkulationen, ed. Philipp Sarasin and Andreas Kilcher (Zürich: diaphanes, 2011), 75–103.

- 5Nadia Bozak, The Cinematic Footprint. Lights, Camera, Natural Resources (New Brunswick/New Jersey/London: Rutgers, 2012).

- 6Kay Dickinson, “Supply Chain Cinema, Supply Chain Education. Training Creative Wizardry for Offshored Exploitation,” in Assembly Codes. The Logistics of Media, eds. Matthew Hockenberry, Nicole Starosielski, and Susan Zieger (Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2021), 171–187.

- 7The Institute für Kulturforschung in Vienna was founded in 1915 by the geographer and cultural historian Erwin Hanslik. See: Ulrich Döge, Kulturfilm als Aufgabe. Hans Cürlis (1889–1982) (Berlin: CineGraph Babelsberg, 2005), 16–19.

- 8See: Hans Cürlis, “Zehn Jahre Institut für Kulturforschung,” Der Bildwart. Blätter für Volksbildung 7, no. 6 (1929): 316.

- 9See: Döge, Kulturfilm als Aufgabe, 80.

- 10Hans Cürlis, Die Weltgeschichte als Kolonialgeschichte. Ein Kulturfilm des Instituts für Kulturforschung (Berlin: Institut für Kulturforschung, 1926) [Accompanying booklet].

- 11See: Rainer Karlsch, Die AGFA-ORWO-Story. Geschichte der Filmfabrik Wolfen und ihrer Nachfolger (Berlin: vbb, 2010); Gottfried Plumbe, Die I.G. Farbenindustrie AG. Wirtschaft, Technik und Politik 1904–1945 (Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1990).

- 12See: Manfred Gill, “Geschichte und Bedeutung der Filmfabrik Wolfen – eine Kurzdarstellung,” in Die Filmfabrik Wolfen. Aus der Geschichte, Heft 1, ed. Industrie- und Filmmuseum Wolfen e.V. (Wolfen: ifm, 1997), 7–16.

- 13For the production of the photographic emulsion, further raw materials such as gelatine, silver, and various chemicals were required. In this context, however, I will concentrate exclusively on the celluloid base.

- 14Jörn Leonhard, “Kriegswirtschaft. Szenarien, Krisen, Mobilisierungen,” in Erster Weltkrieg. Kulturwissenschaftliches Handbuch, ed. Niels Werber, Stefan Kaufmann, and Lars Koch (Stuttgart/Weimar: Metzler, 2014), 265.

- 15Elisabeth Vaupel, “Krieg der Chemiker. Die chemische Industrie im Ersten Weltkrieg,” Chemie in unserer Zeit 48, no. 6 (2014): 461.

- 16Ibid.

- 17“Die Rohstoffquelle in Chile drohte bei dem jährlich rasch steigenden Bedarfe in so naher Zeit zu versiegen, daß um Lebens und Sterbens willen andere Quellen gefunden werden mußten.” [Translation by J. H.], Fritz Haber, “Das Zeitalter der Chemie, seine Aufgaben und Leistungen,” in Fünf Vorträge aus den Jahren 1920–1923. Über die Darstellung des Ammoniaks aus Stickstoff und Wasserstoff. Die Chemie im Kriege. Das Zeitalter der Chemie. Neue Arbeitsweisen. Zur Geschichte des Gaskrieges (Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, 1924), 56.

- 18Jörn Leonhard, “Kriegswirtschaft. Szenarien, Krisen, Mobilisierungen,” 265.

- 19Markus Krajewski, World Projects. Global Information before World War I (Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), 143–145; Elisabeth Vaupel, “Ersatzstoffe – Geschichte, Bedeutung, Perspektiven,” in Ersatzstoffe im Zeitalter der Weltkriege. Geschichte, Bedeutung, Perspektiven, ed. Elisabeth Vaupel (Munich: Deutsches Museum, 2021), 32.

- 20Markus Krajewski assigns the endeavor of the projector Walther Rathenau and the KRA the status of one of the all-encompassing “world projects” around 1900, aiming at a global reach. See: Markus Krajewski, World Projects. Global Information before World War I (Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

- 21See: Elisabeth Vaupel, ed., Ersatzstoffe im Zeitalter der Weltkriege. Geschichte, Bedeutung, Perspektiven (Munich: Deutsches Museum, 2021).

- 22See: Krajewski, World Projects. Global Information before World War I, 145–156.

- 23Sandro Fehr, “Ersatz für den Chilesalpeter. Die Versorgung mit Stickstoffverbindungen während des Ersten Weltkriegs,” in Ersatzstoffe im Zeitalter der Weltkriege. Geschichte, Bedeutung, Perspektiven, ed. Elisabeth Vaupel (Munich: Deutsches Museum, 2021), 239–247; Krajewski, World Projects. Global Information before World War I, 156–162.

- 24Agfa Jahresbericht 1915, 72.

- 25Agfa Jahresbericht 1914, 93.

- 26Agfa Jahresbericht 1915, 85–86.

- 27See: Stefan Kaufmann, “Die Entstehung informationstechnischer Kriegsführung im Ersten Weltkrieg. Zur Logistik der Wahrnehmung,” in Medien – Krieg – Raum, ed. Lars Nowak (Leiden/Boston: Fink, 2018), 161–183.

- 28The Gestalt psychologists Erich Moritz von Hornbostel and Max Wertheimer both worked at the Berlin Institute for Psychology founded by the psychologist and musicologist Carl Stumpf. Together with Stumpf, Hornbostel built up the Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv from 1904, which he directed until his emigration in 1933, and whose sound recordings became the basis of ethnomusicological and psychological research. See: Lars-Christian Koch, Albrecht Wiedmann, and Susanne Ziegler, “The Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv: A Treasury of Sound Recordings,” Acoustical Science and Technology 25, no. 4 (2004): 227–231. For further reading on the sound locator, see: Christoph Hoffmann, “Wissenschaft und Militär. Das Berliner Psychologische Institut und der 1. Weltkrieg,” Psychologie und Geschichte 5, no. 3/4 (1994): 261–285; Axel Volmar, “In Storms of Steel. The Soundscape of World War I and its Impact on Auditory Media Culture during the Weimar Period,” in Sounds of Modern History. Auditory Cultures in 19th- and 20th- Century Europe, ed. Daniel Morat (New York: Berghahn, 2014): 227–255.

- 29Bernhard Siegert, “Luftwaffe Fotografie. Luftkrieg als Bildverarbeitungssystem 1911–1921,” Fotogeschichte 12, no. 45/46 (1992): 43.

- 30See: Hannah Wiemer, “Maskierte Landschaft. Camouflage und Luftphotographie im Ersten Weltkrieg am Beispiel des Malers Solomon J. Solomon,” in Medien – Krieg – Raum, ed. Lars Nowak (Leiden/Boston: Fink, 2018), 185–209.

- 31Agfa Jahresbericht 1915, 86.

- 32Agfa Jahresbericht 1916, 88.

- 33Agfa Jahresbericht 1917, 88.

- 34Ibid., See also: Uli Jung and Wolfgang Mühl-Benninghaus, “Front- und Heimatbilder im Ersten Weltkrieg (1914–1918),” in Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 1 Kaiserreich 1895–1918, ed. Uli Jung and Martin Loiperdinger (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005), 409–412.

- 35Agfa Jahresbericht 1917, 89.

- 36Ibid. After the war, international trade relations and first exports to Italy and France, and later overseas, were resumed. Apart from a small inflation-related decline in 1923/24, the production volume of the Wolfen film factory increased annually and amounted to 116,611,472 meters of celluloid film and 393,806 meters of acetate safety film in 1925.

- 37Elisabeth Vaupel, “Ersatzstoffe – Geschichte, Bedeutung, Perspektiven,” 34–35.

- 38Gustav Bonwitt, Das Celluloid und seine Ersatzstoffe. Handbuch für Herstellung und Verarbeitung von Celluloid und seinen Ersatzstoffen (Berlin: Union, 1933), 24–34; August Schrimpff, Nitrocellulose aus Baumwolle und Holzzellstoffen (Munich: Lehmanns, 1919), 152.

- 39In the Asian region, camphor has always been used as a remedy and incense, and in Europe for pharmaceutical and cosmetic purposes. Due to its intense odor, camphor was also widely used in the storage of textiles as a protective agent against moths. See: Ken Riebensahm, Der steigende Kampferbedarf infolge der Erfindung des Celluloids und die Unterwerfung der indigenen Bevölkerung Taiwans während der japanischen Kolonialherrschaft (PhD, University of Hamburg, 2011), 77–81.

- 40Jeffrey L. Meikle, American Plastic. A Cultural History (New Brunswick/London: Rutgers, 1995), 10–30.

- 41J. M. Klimont, Der technisch-synthetische Campher (Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, 1921), 126; Riebensahm, “Der steigende Kampferbedarf infolge der Erfindung des Celluloids und die Unterwerfung der indigenen Bevölkerung Taiwans während der japanischen Kolonialherrschaft,” 94–95.

- 42Ibid., 94–96.

- 43Gundula Linck-Kestin, Ein Kapitel chinesischer Grenzgeschichte. Han und Nicht-Han im Taiwan der Qing-Zeit 1683–1895 (Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1979), 241–268.

- 44Gundula Linck-Kestin, “Ein Kapitel japanischer Kolonialgeschichte. Die Politik gegenüber der nichtchinesischen Bevölkerung von Taiwan,” NOAG 123 (1978): 65–68.

- 45A. Dubosc, “Die Lage des Kampfers,” Kunststoffe 10, no. 5 (1920): 56.

- 46In 1903, Germany imported 475 tons of natural camphor, making it the second largest importer, just behind the United States with 839 tons. The wholesale price of camphor had tripled since 1881 to 430 marks per 100 kg and continued to rise to 1000 marks per 100 kg in 1907. See: Italo Giglioli, “Campherproduktion und Campherhandel,” Die Chemische Industrie 31, no. 14 (July 1908), 442.

- 47Christopher Kobrak, National Cultures and International Competition. The Experience of Schering AG, 1851–1950 (Cambridge: University Press, 2002), 44–45.

- 48Ibid., 62–65.

- 49Ibid., 92–93, 124.

- 50Pansy Duncan, “Celluloid™. Cecil M. Hepworth, Trick Film, and the Material Prehistory of the Plastic Image,” Film History 31, no. 4 (2019): 92–112.

- 51See: Leo Enticknap, Moving Image Technology. From Zoetrope to Digital (London: Wallflower, 2005), 12.

- 52Duncan, “Celluloid™,” 93.

- 53“Einen Film, der mit besonderen Kniffen und Kunstgriffen hergestellt ist, nennt man einen Trickfilm.” [Translation by J.H.], Hans Ewald, “Der Trickfilm,” in Das Kulturfilmbuch, ed. Edgar Beyfuss and Alex Kossowsky (Berlin: Chryselius & Schulz, 1924), 198.

- 54Sybille Krämer, “Operative Bildlichkeit. Von der ‘Grammatologie’ zu einer ‘Diagrammatologie’? Reflexionen über erkennendes ‘Sehen’,” in Logik des Bildlichen. Zur Kritik der ikonischen Vernunft, ed. Martina Hessler and Dieter Mersch (Bielefeld: transcript, 2009), 98.

- 55[Translation by J.H.], Cürlis, Die Weltgeschichte als Kolonialgeschichte. Ein Kulturfilm des Instituts für Kulturforschung, 23.

- 56Translation by J.H.], Ewald, “Der Trickfilm,” 198.

- 57See: Michael Annegarn-Gläß, Neue Bildungsmedien revisited. Zur Einführung des Lehrfilms in der Zwischenkriegszeit (Bad Heilbrunn: Julius Klinkhardt, 2020), 138–140.

- 58“[Die] Veranschaulichung geographischer Entwicklungen durch kinematographische Wirklichkeitsbilder ist nur ausnahmsweise möglich; mit gestellten Bildern oder Trickzeichnungen täuscht sie bloße Hypothesen als Wirklichkeiten in einer Weise vor, wie die minder sinnlich anschauliche Sprache das glücklicherweise nicht tut.” [Translation by J.H], Felix Lampe, “Das geographische Laufbild,” in Das Kulturfilmbuch, ed. Edgar Beyfuss and Alex Kossowsky (Berlin: Chryselius & Schulz, 1924), 137.

- 59Ralf Forster, “Animierte Karten. Nachgestellte Kriege und symbolische Landnahmen in deutschen Dokumentarfilmen 1921–1945,” in Kampf der Karten. Propaganda- und Geschichtskarten als politische Instrumente und Identitätstexte, ed. Peter Haslinger und Vadim Oswalt (Marburg: Herder-Institut, 2012), 172.

- 60“Im Institut für Kulturforschung wurden auf den Gebieten des kartographischstatistischen Trickfilms […] erstmalig völlig neue Filmtypen bearbeitet und ganz neue wissenschaftliche Ausdrucksformen mit Hilfe des lebenden Lichtbildes herausgebracht.” [Translation by J.H.], Oskar Kalbus, Der Deutsche Lehrfilm in der Wissenschaft und im Unterricht (Berlin: Carl Heymanns, 1922), 39.

- 61Ursula von Keitz, “Wissen als Film. Zur Entwicklung des Lehr- und Unterrichtsfilms,” in Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 2 Weimarer Republik 1918–1933, ed. Peter Zimmermann (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005), 121–124.

- 62Vaupel, “Krieg der Chemiker,” 467.

- 63Actien-Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation, Agfa Handbuch für Kinematographie (Berlin: Dr. Selle, ca. 1922), 17. According to Bonwitt, synthetic camphor did not reach a comparable quality that met the high demands of celluloid film production until 1933 (Bonwitt, Das Celluloid und seine Ersatzstoffe. Handbuch für Herstellung und Verarbeitung von Celluloid und seinen Ersatzstoffen, 162).

- 64Actien-Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation, Agfa Handbuch für Kinematographie, 18.

- 65Walther Schmidt and Georg Heise, Welthandels-Atlas, Band 18. Baumwolle. Produktion, Handel und Konsum (Berlin: Columbus, 1927), 10–11.

- 66Agfa had signed contracts with Ufa in 1918 in which exclusive price concessions were negotiated. In return, Ufa undertook to purchase the majority of its (domestic and foreign) film stock requirements from Agfa. See: Karlsch, Die AGFA-ORWO-Story. Geschichte der Filmfabrik Wolfen und ihrer Nachfolger, 52.

- 67Schmidt and Heise, Welthandels-Atlas, Band 18. Baumwolle. Produktion, Handel und Konsum Welthandelsatlas, 8–9.

Actien-Gesellschaft für Anilin-Fabrikation. Agfa Handbuch für Kinematographie. Berlin: Dr. Selle, ca. 1922.

Bonwitt, Gustav. Das Celluloid und seine Ersatzstoffe. Handbuch für Herstellung und Verarbeitung von Celluloid und seinen Ersatzstoffen. Berlin: Union, 1933.

Bozak, Nadia. The Cinematic Footprint. Lights, Camera, Natural Resources. New Brunswick/New Jersey/London: Rutgers, 2012.

Cürlis, Hans. Die Weltgeschichte als Kolonialgeschichte. Ein Kulturfilm des Instituts für Kulturforschung. Berlin: Institut für Kulturforschung, 1926 (Accompanying booklet).

Cürlis, Hans. “Zehn Jahre Institut für Kulturforschung.” Der Bildwart. Blätter für Volksbildung 7, no. 6 (1929): 316–323.

Dickinson, Kay. “Supply Chain Cinema, Supply Chain Education. Training Creative Wizardry for Offshored Exploitation.” In Assembly Codes. The Logistics of Media, edited by Matthew Hockenberry, Nicole Starosielski, and Susan Zieger, 171–187. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2021.

Djeinen, A. “Mittel zur Beschwörung der Kampferkrise. Verschiedene Verbindungen zur Herstellung von Zelluloid; Zelluloidersatzstoffe.” Kunststoffe 10, no. 3 (1920): 33.

Döge, Ulrich. Kulturfilm als Aufgabe. Hans Cürlis (1889–1982). Berlin: CineGraph Babelsberg, 2005.

Dommann, Monika. “Handling, Flowcharts, Logistik. Zur Wissensgeschichte und Materialkultur von Warenflüssen.” In Zirkulationen, edited by Philipp Sarasin, and Andreas Kilcher, 75–103. Zürich: diaphanes, 2011.

Dubosc, A. “Die Lage des Kampfers.” Kunststoffe 10, no. 5 (1920): 56.

Duncan, Pansy. “Celluloid™. Cecil M. Hepworth, Trick Film, and the Material Prehistory of the Plastic Image.” Film History 31, no. 4 (2019): 92–112.

Enticknap, Leo. Moving Image Technology. From Zoetrope to Digital. London: Wallflower, 2005.

Ewald, Hans. “Der Trickfilm.” In Das Kulturfilmbuch, edited by Edgar Beyfuss and Alex Kossowsky, 198–201. Berlin: Chryselius & Schulz, 1924.

Fehr, Sandro. “Ersatz für den Chilesalpeter. Die Versorgung mit Stickstoffverbindungen während des Ersten Weltkriegs.” In Ersatzstoffe im Zeitalter der Weltkriege. Geschichte, Bedeutung, Perspektiven, edited by Elisabeth Vaupel, 237–259. Munich: Deutsches Museum, 2021.

Forster, Ralf. “Animierte Karten. Nachgestellte Kriege und symbolische Landnahmen in deutschen Dokumentarfilmen 1921–1945.” In Kampf der Karten. Propaganda- und Geschichtskarten als politische Instrumente und Identitätstexte, edited by Peter Haslinger und Vadim Oswalt, 171–181. Marburg: Herder-Institut, 2012.

Giglioli, Italo. “Campherproduktion und Campherhandel.” Die Chemische Industrie 31, no. 14 (1908): 438–442.

Gill, Manfred. “Geschichte und Bedeutung der Filmfabrik Wolfen – eine Kurzdarstellung.” In Die Filmfabrik Wolfen. Aus der Geschichte, Heft 1, edited by Industrie- und Filmmuseum Wolfen e.V., 7–16. Wolfen: ifm, 1997.

Gramlich, Naomie. “Mediengeologisches Sorgen. Mit Otobong Nkanga gegen Ökolonialität.” Zeitschrift für Medienwissenschaft 13, no. 24 (2021): 65–76.

Haber, Fritz. “Das Zeitalter der Chemie, seine Aufgaben und Leistungen.” In Fünf Vorträge aus den Jahren 1920–1923, von Fritz Haber, 42–65. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, 1924.

Hockenberry, Matthew, Nicole Starosielski, and Susan Zieger, eds. Assembly Codes. The Logistics of Media. Durham/London: Duke University Press, 2021.

Hoffmann, Christoph. “Wissenschaft und Militär. Das Berliner Psychologische Institut und der 1. Weltkrieg.” Psychologie und Geschichte 5, no. 3/4 (1994): 261–285.

Jung, Uli, and Wolfgang Mühl-Benninghaus. “Front- und Heimatbilder im Ersten Weltkrieg (1914–1918).” In Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 1 Kaiserreich 1895–1918, edited by Uli Jung, and Martin Loiperdinger, 381–486. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005.

Kalbus, Oskar. Der Deutsche Lehrfilm in der Wissenschaft und im Unterricht. Berlin: Carl Heymanns, 1922.

Karlsch, Rainer. Die AGFA-ORWO-Story. Geschichte der Filmfabrik Wolfen und ihrer Nachfolger. Berlin: vbb, 2010.

Kaufmann, Stefan. “Die Entstehung informationstechnischer Kriegsführung im Ersten Weltkrieg. Zur Logistik der Wahrnehmung.” In Medien – Krieg – Raum, edited by Lars Nowak, 161–183. Leiden/Boston: Fink, 2018.

Keitz, Ursula von. “Wissen als Film. Zur Entwicklung des Lehr- und Unterrichtsfilms.” In Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 2 Weimarer Republik 1918–1933, edited by Peter Zimmermann, 120–150. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005.

Klimont, J. M. Der technisch-synthetische Campher. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, 1921.

Kobrak, Christopher. National Cultures and International Competition. The Experience of Schering AG, 1851–1950. Cambridge: University Press, 2002.

Koch, Lars-Christian, Albrecht Wiedmann, and Susanne Ziegler. “The Berlin Phonogramm-Archiv: A Treasury of Sound Recordings.” Acoustical Science and Technology 25, no. 4 (2004): 227–231.

Krajewski, Markus. World Projects. Global Information before World War I. Minneapolis/London: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Krämer, Sybille. “Operative Bildlichkeit. Von der ‘Grammatologie’ zu einer ‘Diagrammatologie’? Reflexionen über erkennendes ‘Sehen’.” In Logik des Bildlichen. Zur Kritik der ikonischen Vernunft, edited by Martina Hessler and Dieter Mersch, 94–122. Bielefeld: transcript, 2009.

Kreimeier, Klaus. “Ein deutsches Paradigma. Die Kulturabteilung der Ufa.” In Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 2 Weimarer Republik 1918–1933, edited by Peter Zimmermann, 67–86. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005.

Lampe, Felix. “Das geographische Laufbild.” In Das Kulturfilmbuch, edited by Edgar Beyfuss and Alex Kossowsky, 135–140. Berlin: Chryselius & Schulz, 1924.

Leonhard, Jörn. “Kriegswirtschaft. Szenarien, Krisen, Mobilisierungen.” In Erster Weltkrieg. Kulturwissenschaftliches Handbuch, edited by Niels Werber, Stefan Kaufmann and Lars Koch, 259–279. Stuttgart/Weimar: Metzler, 2014.

Linck-Kestin, Gundula. “Ein Kapitel japanischer Kolonialgeschichte: Die Politik gegenüber der nichtchinesischen Bevölkerung von Taiwan.” NOAG 123 (1978): 61–85.

Linck-Kestin, Gundula. Ein Kapitel chinesischer Grenzgeschichte. Han und Nicht-Han im Taiwan der Qing-Zeit 1683–1895. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1979.

Maxwell, Richard, and Toby Miller. Greening the Media. Oxford: University Press, 2012.

Meikle, Jeffrey L. American Plastic. A Cultural History. New Brunswick/London: Rutgers, 1995.

Parks, Lisa, and Nicole Starosielski. Signal Traffic. Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures. Urbana/Chicago/Springfield: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Plumbe, Gottfried. Die I.G. Farbenindustrie AG. Wirtschaft, Technik und Politik 1904–1945. Berlin: Duncker & Humblot, 1990.

Riebensahm, Ken. “Der steigende Kampferbedarf infolge der Erfindung des Celluloids und die Unterwerfung der indigenen Bevölkerung Taiwans während der japanischen Kolonialherrschaft.” Diss., Universität Hamburg, 2011.

Schrimpff, August. Nitrocellulose aus Baumwolle und Holzzellstoffen. Munich: Lehmanns, 1919.

Schmidt, Walther, and Georg Heise. Welthandels-Atlas, Band 18: Baumwolle. Produktion, Handel und Konsum. Berlin: Columbus, 1927.

Siegert, Bernhard. “Luftwaffe Fotografie. Luftkrieg als Bildverarbeitungssystem 1911–1921.” Fotogeschichte 12, no. 45/46 (1992): 41–54.

Vaupel, Elisabeth. “Krieg der Chemiker. Die chemische Industrie im Ersten Weltkrieg.” Chemie in unserer Zeit 48, no. 6 (2014): 460–475.

Vaupel, Elisabeth, ed. Ersatzstoffe im Zeitalter der Weltkriege. Geschichte, Bedeutung, Perspektiven. Munich: Deutsches Museum, 2021.

Vaupel, Elisabeth. “Ersatzstoffe – Geschichte, Bedeutung, Perspektiven.” In Ersatzstoffe im Zeitalter der Weltkriege. Geschichte, Bedeutung, Perspektiven, edited by Elisabeth Vaupel, 9–81. Munich: Deutsches Museum, 2021.

Volmar, Axel. “In Storms of Steel. The Soundscape of World War I and its Impact on Auditory Media Culture during the Weimar Period.” In Sounds of Modern History. Auditory Cultures in 19th- and 20th- Century Europe, edited by Daniel Morat, 227–255. New York: Berghahn, 2014.

Wiemer, Hannah. “Maskierte Landschaft. Camouflage und Luftphotographie im Ersten Weltkrieg am Beispiel des Malers Solomon J. Solomon.” In Medien – Krieg – Raum, edited by Lars Nowak, 185–209. Leiden/Boston: Fink, 2018.

ARCHIVAL MATERIALS

Archive of the former film factory Wolfen, Industrie- und Filmmuseum Wolfen:

Agfa Jahresbericht 1914

Agfa Jahresbericht 1915

Agfa Jahresbericht 1916

Agfa Jahresbericht 1917

Agfa Jahresbericht 1918