In Defense of Culture

The Vienna Urania and the Cultural Film

Table of Contents

Screening Propaganda

In Defense of Culture

The Raw Materials of Celluloid Film

Wholeness and Nature

The Austrian Province as Subject and Space of Action in Educational Film Practices

The Development of Educational Cinema for Schools in the Soviet Union in the 1930s

Educational Film in East Germany (GDR) in 1950–1990 in Perspective of the “Grammar of Schooling”

No Instructions, Just Some Advice

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Öhner, Vrääth. “In Defense of Culture: The Vienna Urania and the Cultural Film.” Research in Film and History 5 (2023): 1–30. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/22724.

After cultural film (“Kulturfilm”), “a German variant of documentary based on ideals of experiential education,”1 had long dominated the German-speaking world’s conception of what documentaries are and can be, it has been gradually pushed back since the early 1960s (a milestone would be the Oberhausen Manifesto of 1962) and subsequently thoroughly forgotten. Apart from smaller publications – such as Hartmut Bitomsky’s essay on the Nazikulturfilm,2 which was written in the context of the production of DEUTSCHLANDBILDER (FRG 1983) and published in two parts in the journal Filmkritik in 1983, or Christa Blümlinger’s dissertation from 1986, Verdrängte Bilder in Österreich,3 which devoted a short chapter to the cultural film of the postwar period – it took a good 40 years for film studies to deal with the cultural film in depth. The context of this belated attention was a large-scale research project on the “History of Documentary Film in Germany” from 1895 to 1945, the results of which were finally published in three volumes in 2005.4 Since then, almost everything has been said about the cultural film, its origins in wartime propaganda and cinema reform as thoroughly researched as its difference from the modern documentary film of Anglo-American and Soviet influence. Even the delicate ties that were forged between cultural film and the European film avant-garde during the Weimar Republic have been given their due.5

Against the background of this body of knowledge, my contribution aims to make use of this circumstance – that basically everything has already been said – in order to undertake a shift in perspective that no longer views the cultural film in distinction to the modern and by now canonical documentary film,6 but rather ties it back more strongly to the milieu of its creation, that is, to those practices of educational and instructional film that media scholars Eef Masson and Frank Kessler have described as elements of a “pedagogical” or a “performance dispositif.”7 This involves, first, an analysis of the reciprocal relationships between technology, cinematic form, and audience positioning in concrete historical screening contexts, and, by extension, a conception of media history that no longer conceives of it as a temporal sequence of clearly determinable forms and formats, but rather as “configurations of hardware, text, and spectatorship”8 that are subject to a thoroughly erratic development.

As will be shown by the example of the Vienna Urania, one of the leading institutions of adult education in Austria, which during the interwar period relied on cultural film not only as a means of instructive entertainment but also as a motor for establishing a film culture supported by bourgeois values, this development ran counter to the usual classifications of film history. What the Urania subsumed under the term cultural film in its lecture program was neither limited to non-fictional films (even if these dominated the offerings) nor identical with the unloved supporting program for commercial movie theaters (even if these were also shown in individual cases). The Urania’s cultural film program included German-language as well as international productions; feature-length educational films as well as short subjects on travel, sports, and ethnology. What held the heterogeneity of this offering together was a screening practice that surrounded the cinematic text with a whole series of paratexts (spoken lectures, lantern slides, and accompanying music), as well as the goal pursued with this practice: to educate the audience to see “good” films, that is, films of cultural and educational value.

Constructive Cinema Reform

From the beginning, the programming policy of the Vienna Urania, as far as the use of films in the context of adult education was concerned, followed a scheme developed by the early cinema reform movement. This involved, as Yasuo Imai has pointed out, a pedagogically motivated critique of the harmful influence of “film dramas” on the population, combined with the conviction that “technically and substantively sound cinematographic representations can be an excellent means of instruction and entertainment.”9 Following this scheme, the Urania integrated films into its lecture program at least since 1910, when it moved to the newly constructed Urania building on the Aspern Bridge, in the form of the so-called “Urania Kinematogramme,” i.e., illustrated lectures with musical accompaniment, which presented a colorful mixture of different cinematographic recordings – from travelogue to scientific films to humoresque. A typical program could contain the following elements: “Picturesque landscapes from France – Zoological studies – Humorous drawings – The Nikolaital from Visp to Zermatt – Cinematographic weekly report – Humoresque,”10 and thus resembled the offerings of commercial movie theaters of early cinema, albeit compiled under popular educational aspects.

While short film programs with more or less closely related content were already an integral part of the Urania’s lecture program before World War I, the importance of film as a medium changed fundamentally with the premiere of the full-length “nature feature film” DAS WUNDER DES SCHNEESCHUHS / THE MIRACLE OF THE SNOW SHOE (DE 1920) on February 4, 192111: From now on, the film rather than the lecture was the focus of a program format that soon showed “Urania films with popular explanations” once or twice a day with nice regularity.12 The announcement of the film in the Urania’s program already revealed the reformist thrust of the new series: “With this magnificent film, the Urania wants to show that there is a higher cinematic art on a grand scale than the ordinary one of film drama and film humoresque; a cinematic art that has an important and promising task ahead of it in the service of adult education.”13

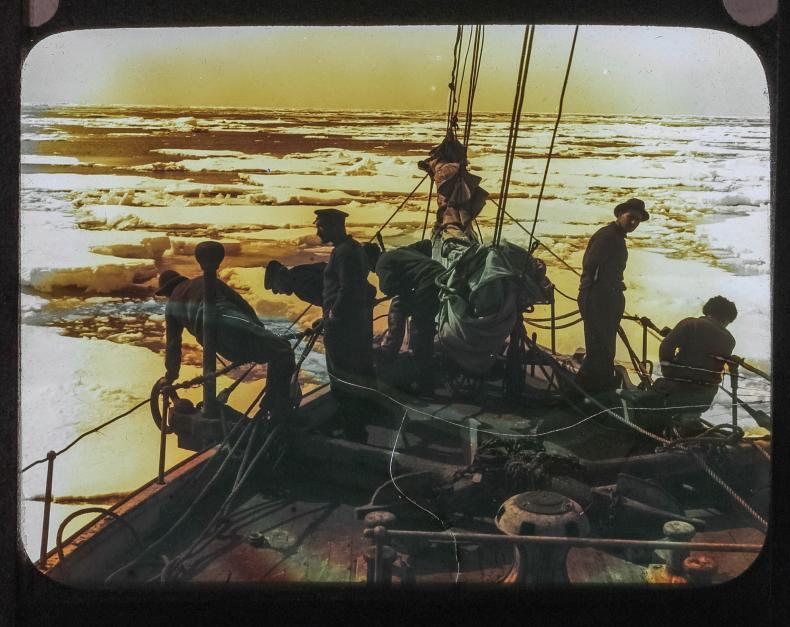

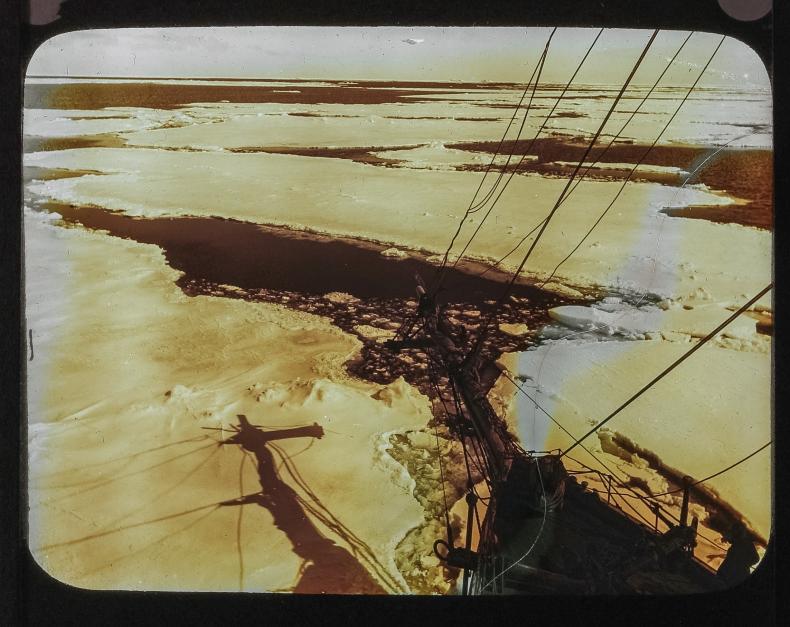

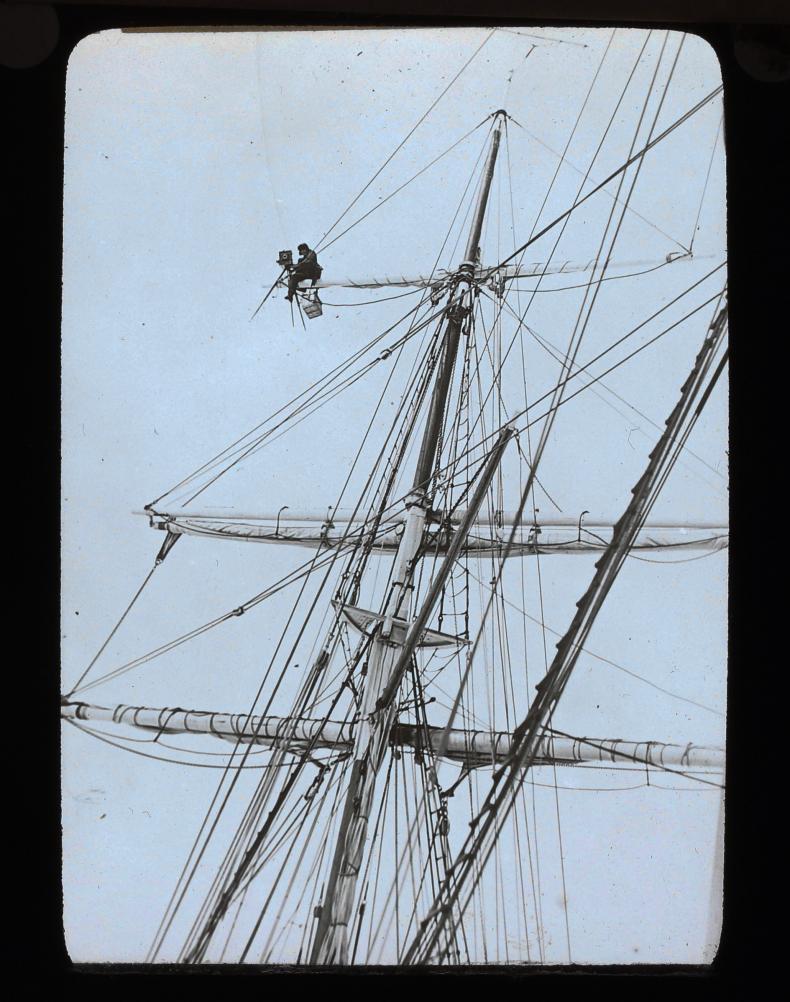

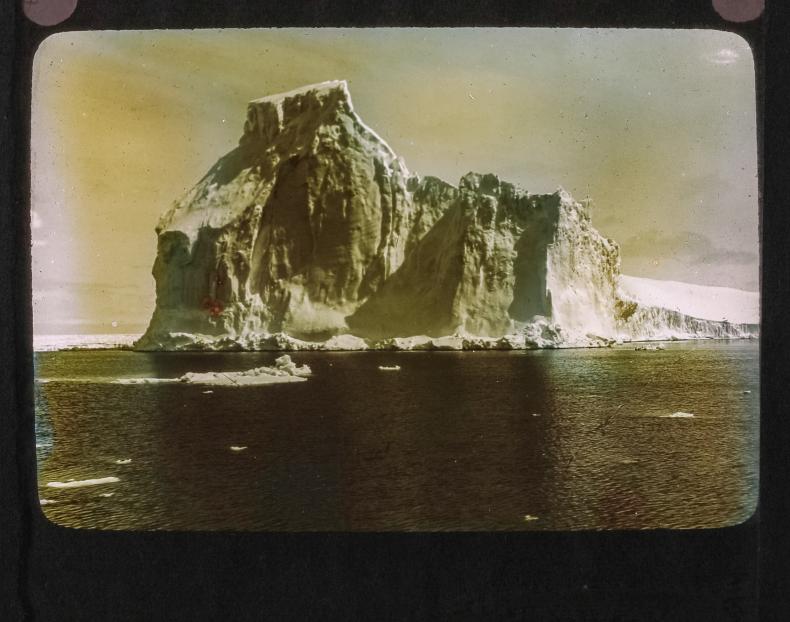

For the Urania, DAS WUNDER DES SCHNEESCHUHS, like SHACKLETONS SÜDPOLEXPEDITION / SOUTH – SIR ERNEST SHACKLETON'S GLORIOUS EPIC OF THE ANTARCTIC (UK 1919), which opened in the same year, 1921, became a success that exceeded even the wildest expectations. Between 1921 and 1924, 73,598 viewers saw DAS WUNDER DES SCHNEESCHUHS in 163 screenings, while SHACKLETONS SÜDPOLEXPEDITION even made it to 181,610 viewers in 322 screenings during the same period.14 For Ludwig Koessler, the longtime president of the Vienna Urania, these successes were proof “that the cinema misery we have been suffering from for so many years is not the fault of the population, but of those who have the cinema business – production, distribution and screening – in their hands and therefore command the selection of films shown to the population as well as the way they are shown.”15

Koessler summarized the diverse and sometimes contradictory tasks that a non-profit educational institution like the Urania could take on with its cultural film program under the catchphrase “constructive cinema reform.”16 This reform was characterized by the dissemination of the cultural film, which Koessler understood to mean not only the “shorter or longer educational film,” “which primarily serves to instruct in school or adult education and can only be added to the entertainment film as an accompaniment.”17 Under “cultural film” Koessler subsumed “also and above all the ethically and aesthetically high-quality entertainment film, that is, in addition to the educational entertainment films (such as SHACKLETONS SÜDPOLEXPEDITION, WUNDER DES SCHNEESCHUHS […] etc.) also the ethically impeccable artistic film drama.”18

As an essential component of constructive cinema reform, the Urania’s cultural film program was intended, on the one hand, to convince film producers and distributors of the appeal of cultural film. If, as Koessler never tired of claiming, the audience’s taste was not dominated exclusively by those lower needs that had been created by the international film industry in the first place, but instead demanded, as it were, films on a higher cultural level than had previously been offered (cultural films, in other words), then this created a powerful incentive for producers and distributors to increasingly look for such films on the distribution market or to produce them themselves. Not only would the Urania’s programming benefit from a greater supply of cultural films “in keeping with the goals of cinema reform,”19 but commercial movie theaters would also be enabled to include cultural films in their programming. On the other hand – and for Koessler this was an equally essential component of constructive cinema reform – the Urania’s cultural film program was intended to contribute to the education and refinement of the audience’s taste in film as well as to reach new audiences. Last but not least, it represented a welcome source of income and thus “an excellent means of self-preservation for the places of adult education,” which were usually dependent on “donations, subsidies and other benefits.”20

Admittedly, Koessler’s argumentation on constructive cinema reform proved to be somewhat self-contradictory: How was the cultural film supposed to contribute to the formation of a taste that Koessler had shortly before presupposed as a justification for its success? One possible answer to this question may be found in the fact that the cultural significance of the new medium for the supporters of cinema reform had not been completely clarified. Koessler had only mentioned in passing in his remarks that the cultural film, unlike literature, theater, or the fine arts, “represents a new artistic means of expression whose elements and rules, it seems, have not yet been traced.”21 As Yasuo Imai has noted, the recognition of film as a new means of artistic expression challenged the basic scheme of the cinema reform movement, which had criticized the status quo of cinema from the fixed standpoint of bourgeois culture. With the recognition of film, it became “gradually difficult for the cinema reform movement to find the standpoint for the pedagogical critique of these conditions outside the social and cultural conditions to which film refers.”22 This was all the more so because the “abandonment of the authority of bourgeois culture by no means secured a new criterion”23 for the meaningful use of film in pedagogical contexts.

The fact that Koessler’s argumentation was on shaky ground became obvious at the very conference that the Urania had organized in May 1924 to bring the cause of constructive cinema reform to public attention.24 In the run-up to the conference, representatives of the film industry had already criticized the fact that they had not been invited,25 and in his conference report, one of the speakers, Béla Balázs, summed up the problems associated with the idea of cinema reform. First, many misunderstandings could have been avoided if the conference had disclosed from the beginning that it was by no means its intention to discuss “reforms of cinematic art and cinema” in general, but merely to discuss “how cinema, in its existing form, could be better utilized for youth and popular educational purposes.” But because the impression had been created that the conference really wanted to “reform an art with resolutions,” the question could be asked, secondly, whether “it has already occurred to anyone to want to renew literature, music, painting by way of congress?!”26

What Balázs, who was more than a step ahead of the cinema reform movement in his reflections on cinematic art,27 still diplomatically wanted to be seen as a misunderstanding, fundamentally called into question the Urania’s efforts in the field of feature-length cultural film. Koessler’s constructive cinema reform had been very much committed to stimulating the production of ethically and aesthetically sound entertainment films, not least because for Koessler the “adaptation of film drama to our old folk culture” represented the “great problem of cinema.”28 What Koessler, and with him the cinema reform movement, failed to consider was the fact that with film a new popular culture had emerged, adapted to the conditions of modern society, which no longer wanted to have much to do with the popular forms of entertainment of the 19th century. At the cinema reform conference, this fundamental misunderstanding had become obvious: After the screening of Fritz Lang’s DIE NIBELUNGEN: SIEGFRIED (DE 1924), which still corresponded most closely to Koessler’s idea of the adaptation of film drama to the old folk culture, the director present was confronted with furious attacks from “women’s club moralists.”29

To make matters worse, in 1924, the Urania experienced a noticeable decline in the number of viewers at its afternoon shows for the first time. Management reacted by lowering the ticket prices for educational Urania films, which “cannot compete with the feature films of the surrounding area.”30 In fact, the Urania had already found it difficult in the years before to repeat the great successes of the early days. In particular, educational cultural films from Austrian production such as KÖNIG DACHSTEIN / KING DACHSTEIN (AT 1923) or VOM BAUM ZUR ZEITUNG / FROM TREE TO NEWSPAPER (AT 1923) hardly ever achieved the same results as their foreign counterparts, instead scoring comparatively low numbers of 15,000 to 25,000 viewers.31 Thus, another pillar of constructive cinema reform had begun to falter: the exemplary effect that the Urania’s cultural film program was to have on film producers and distributors due to its appeal to audiences. After the great successes of the early days, it very soon became apparent that the Urania films were able to occupy a considerable niche, but nevertheless merely a niche on the Austrian film market. At the latest when Adolf Hübl – who would after 1945 go on to become the director of the Ministry of Education’s service for educational films and slides, the Bundesstaatliche Hauptstelle für Lichtbild und Bildungsfilm (SHB) – took over the management of the Vienna Urania’s Department for Film and Foreign Affairs in 1924, the Urania concentrated its activities in the film sector more strongly on the promotion of educational and instructional films. For example, educational films were procured for loan and in 1928 the Austrian Educational Film Archive was established in cooperation with the Schulkinobund.32 The Urania maintained its regular program of feature-length cultural films until Austria’s Anschluss to Nazi Germany in 1938. After that, the non-profit association of the Vienna Urania was “incorporated into the ‘Reichsamt Deutsches Volksbildungswerk’ within the ‘NS-Gemeinschaft Kraft durch Freude’ of the Deutsche Arbeitsfront (DAF)”33 and the cultural film program of the Urania was dissolved.

Screening Practices

When the Urania included cultural films in its lecture program in the course of constructive cinema reform, it was not without concessions to traditional forms of adult education. As the title of the series chosen at the beginning for the cultural film program – “Urania Films with Popular Explanation”34 – indicated, the Urania oriented itself to the model of the lantern slide lecture. A lecture manuscript was written for each film, which was read aloud by a lecturer during the projection and explained the progress of the plot or its context. The lecture was usually supported by a series of lantern slides, which either came from the production context of the film or were compiled from the extensive lantern slide archive of the Urania according to the film’s theme. With the introduction of sound film in the early 1930s, the lecture and lantern slide projection took place before the film began, but throughout the silent era they functioned mostly as interruptions of the cinematic flow. SHACKLETONS SÜDPOLEXPEDITION, for example, was screened in 22 parts, explained and contextualized by as many lecture parts and by a total of 85 lantern slides.35 According to a contemporary account by Gustav Adolf Witt, the ministerial councilor responsible for film issues in the Austrian Ministry of Education, the whole was accompanied “by music selected in each case in special adaptation to the subject and arranged by a creative conductor.”36

The Urania’s screening practice was thus preceded by considerable interventions in the structure of the films shown. These interventions were legally secured by contractual agreements with the film trade. The Urania not only acquired the exclusive screening rights for Austria for the films it showed, but also reserved the right to have the films in their distribution re-edited “by scholars and popular educators according to scientific and adult educational principles.”37 From the pedagogical point of view, these principles followed the widespread notion in adult education that a film’s “inherent fleetingness of impression can be remedied by the addition of explanations and still images, thus preparing and deepening the understanding of what is shown and the mood inherent in it.”38 In practice, however, the interventions in the film’s structure were mostly limited to the removal of the opening credits and the intertitles, whose orientation function for the cinematic narration was taken over by the spoken lecture and, where deemed necessary, supplemented by additional explanations.

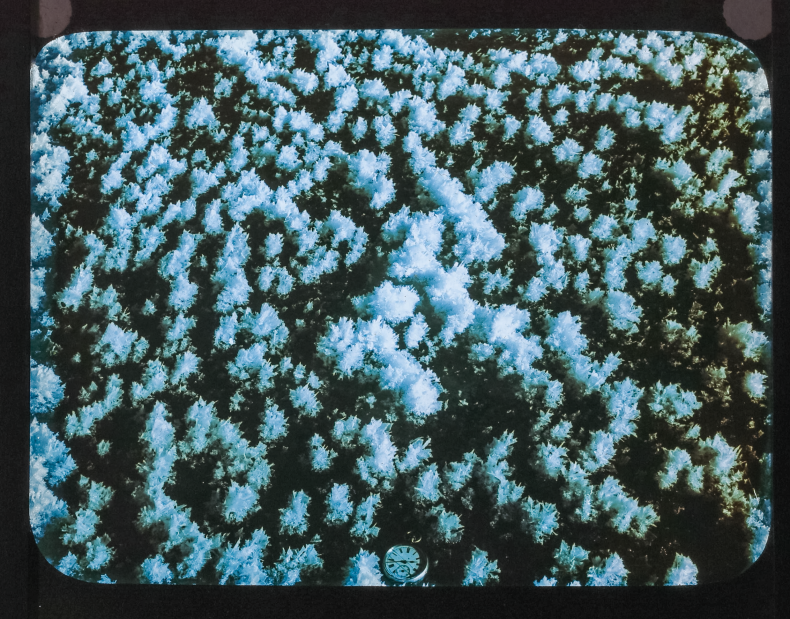

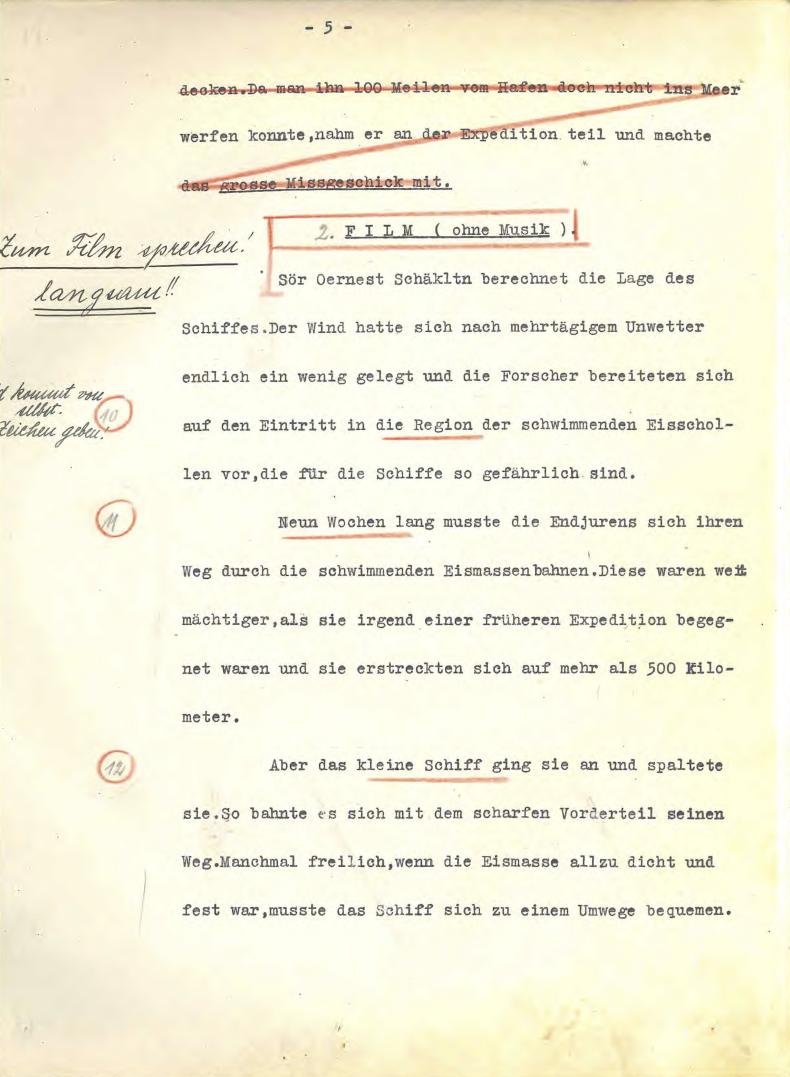

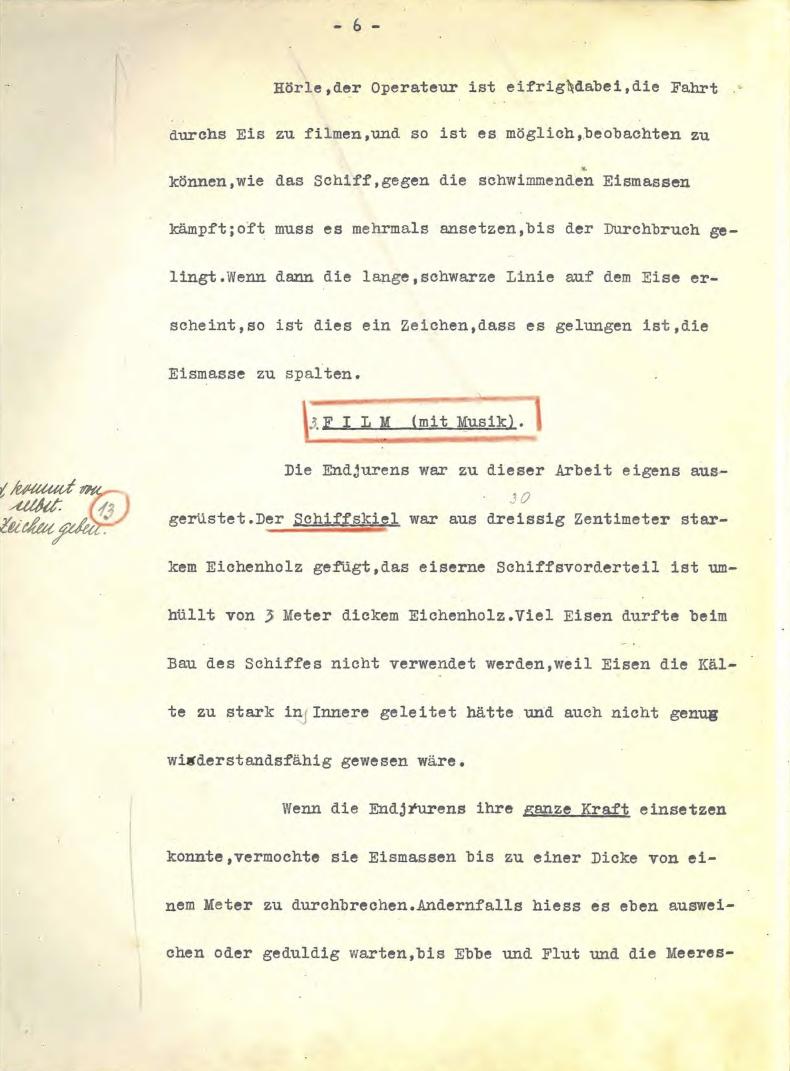

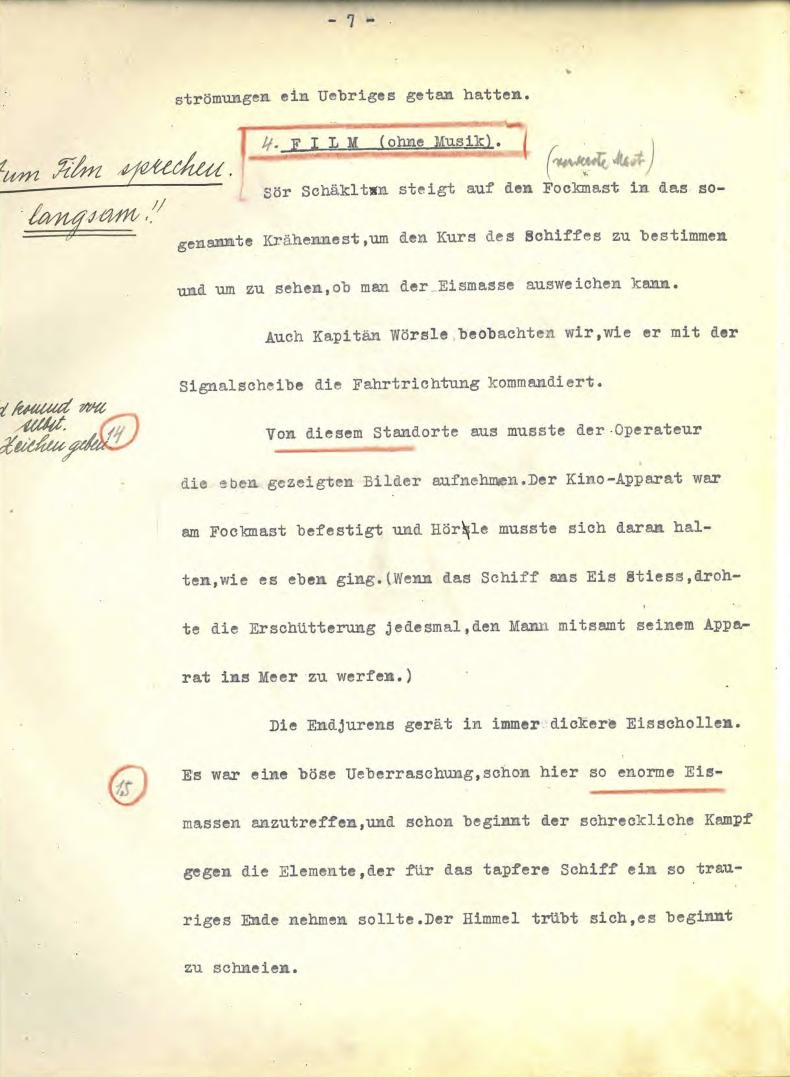

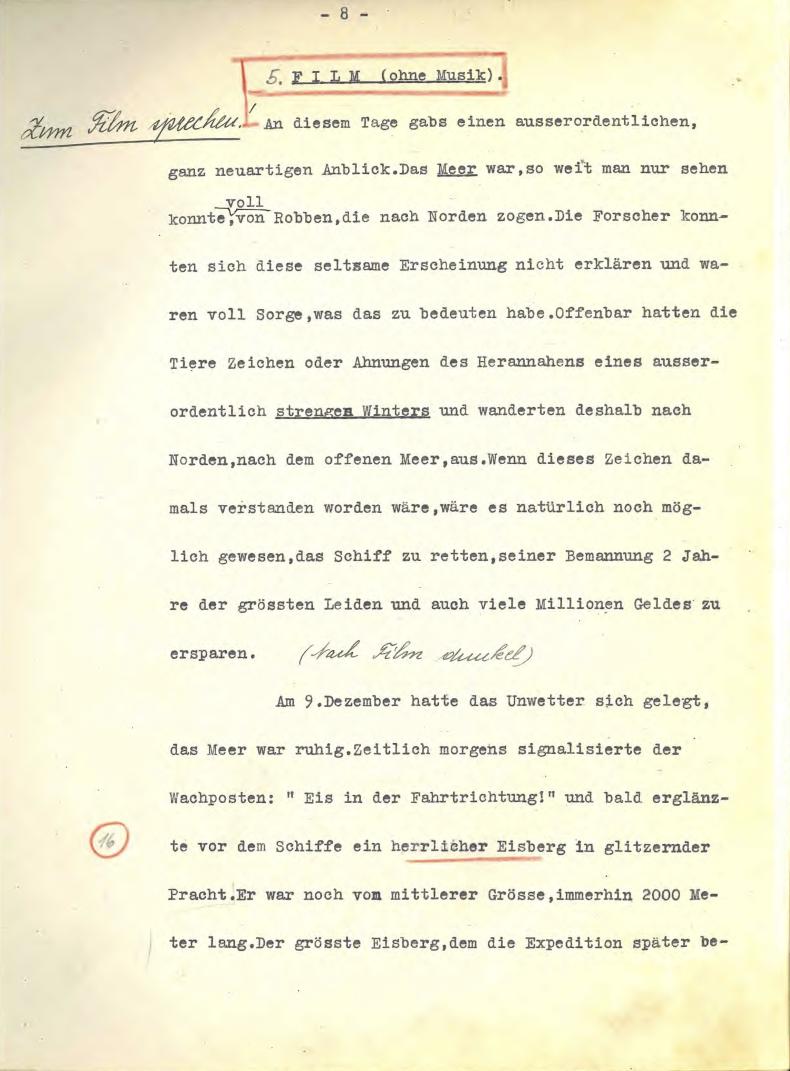

The links between the lecture and the film, on the other hand, were more elaborate. As can be seen from the lecture manuscript for SHACKLETONS SÜDPOLEXPEDITION, one of the more complex examples of the genre, the lecture text and accompanying lantern slides not only preceded the individual parts of the film, but in some cases were directly integrated into the projection of the film.39 The lecture manuscript, which contained detailed stage directions, accordingly, distinguished between three different forms of projection. While the instructions “Film” as well as “Film (music)” applied to those cases in which the slide lecture was presented before the corresponding film segment, the instruction “Film (without music). Speak to the film!” indicated that the lecture text was to be read out synchronously with the film. The lantern slides supporting the spoken lecture interrupted the course of the film at the points marked in the lecture manuscript by means of crossfading. This type of presentation was made possible by the development of projectors with a standstill device in the early 1920s.40 These allowed the projectionist to stop the film at any point in order to crossfade to a series of successive lantern slides, as in the present example.

The Urania’s screening practice integrated a whole range of different actors: scholars and adult educators adapted the commercially purchased films in adcance to meet the Urania's educational requirements, the authors of the lecture manuscripts also ensured the selection of suitable lantern slides, and finally lecturers and projectionists were involved in the smooth running of a Urania film screening with popular explanation. The result of this practice was the subordination of the film and the context it created to the spoken word and its supplement, the lantern slide. In the lecture manuscripts preserved in the Austrian Archives for Adult Education (Österreichische Volkshochschularchiv), there is – as already mentioned – no indication that the editing of the films would have significantly changed the cinematic context of meaning. Except for the segmentation of the films into units of meaning, which could sometimes comprise only individual scenes, but sometimes also entire sequences, the lecture text was limited to anticipating the following film sequence in a descriptive, explanatory, or commentary manner. With one notable exception: the introduction, which was read before the projection of the film began. Hardly any lecture failed at this point to refer to the historical significance of the subjects dealt with in the films, regardless of whether the films themselves contained such a reference or not.

While description, explanation, and commentary directed the viewer’s attention to the traces of meaning that were thought to be too fleeting in the moving image, supported orientation in the cinematic context, and in this way helped to distinguish the essential from the merely incidental, the introductory reference to the historical significance of the subjects dealt with in the films fulfilled another function. In addition to invoking the bourgeois educational canon and setting the mood for the events to come, the aim was to eliminate a deficiency that – according to the common conviction – was necessarily inherent in motion pictures: their superficiality.41 Non-fictional films in particular could not help but show things and circumstances from a contemporary point of view. What the moving image thus lacked, and what the supporters of cinema reform complained about accordingly, was the historical depth dimension of the things and circumstances shown, the consciousness of their historical becoming, which could not be gained from viewing the film alone. The task of the introductory lecture was thus to convey knowledge about the historicity of the subjects shown in the films, even before they first appeared on the screen.

At times, the introductory lecture fulfilled the undoubtedly desired effect of establishing a link between the cinematic action and that old folk culture whose adaptation to the film drama had represented the great problem of cinema for Ludwig Koessler. In the “Introduction to the First Act” of KÖNIG DACHSTEIN, this connection was made as follows:

It is no mere coincidence, but spiritual necessity, that it was precisely in Europe that mountain sports had their first home. Even if until deep into modern times the “terrible wilderness” of the mountains forms a standing phrase in the travel descriptions of alpine regions, this has always needed to be understood with a certain restriction: There have always been peaks that have enjoyed a warm, truly rooted folkloric appeal among the inhabitants, even if they have not yet been trodden by any human foot.42

At times, however, the will to historical embedding also led to the grotesque situation that the introductory words in the medium of language only anticipated what – as in the case of Wilhelm Prager’s WEGE ZU KRAFT UND SCHÖNHEIT / WAYS TO STRENGTH AND BEAUTY (DE 1925) – the first act of the film itself thematized in detail: The harmony between body and mind that still defined Hellenic culture was mentioned here as well, as was the demise of this ideal in the industrial culture of the present, whose harmful effects on public health were reflected in the statistics of hospitals.43 The decisive difference was that Prager had staged these facts with vivid images and via contrasting montage sequences, which presumably impressed themselves more strongly on the viewers’ memory than the linguistically generated ones of the introductory lecture.

This extreme example openly reveals the self-imposed limitations of a screening practice whose explanations referred exclusively to film as a visible image of reality, but not to the reality of the cinematic image. Paraphrasing Walter Benjamin’s dictum, the popular explanations of the Urania presupposed that it was the same reality that spoke to the camera as to the viewer’s eye. With the increasing development of cinematic modes of expression, such a screening practice was bound to reach its limits sooner or later. While the anticipatory description and explanation of what was subsequently shown in the image might have served its good purpose of orientation and directing attention where films still operated in the mode of the “view”44 – that is, in the mode of the mere chronological or thematic connection of shots –, they lost this function where non-fictional films began to develop a dramatic narrative taken from reality and telling the essential story of that reality. When a film like Robert Flaherty’s MOANA (USA 1926), which was also shown in the cultural film program of the Urania,45 needed one hour of film time to narrate one day in the life of the Samoans, but this day simultaneously comprised “a drama of days and nights, of the round of the year’s seasons” as well as “of the fundamental fights which give the people sustenance,”46 then a meaningful segmentation of the film’s sequences became difficult to impossible, and neither description nor explanation of what was shown in the film took hold. What remained was to place the lecture before the beginning of the film and to adopt in it the mood and view of the cinematic narrative: “Moana, the son of the South Seas – this title is not arbitrarily chosen for the sake of the euphony of the words, it is rather the content and epitome of the perfect life of which our film gives an imperfect reflection.”47

“Cultural Film and Film Culture”

“The cultural film presupposes will to film culture, and film culture is promoted by the cultural film.”48 The reflections on the interdependent relationship between “Cultural Film and Film Culture” that Felix Lampe, head of the Bildstelle at the Zentralinstitut für Erziehung und Unterricht in Berlin, had made in his essay of the same name in 1924 served the Vienna Urania as a blueprint for its efforts to lead the film industry out of its “state of immaturity.”49 Lampe had lectured on the topic of “Film and School” at the Urania’s cinema reform conference and was also a welcome guest of the house afterwards.50 In particular, Lampe’s remarks on the “culture of film content,” which in cultural film, more than in any other genre, aimed at increasing the “culture of the viewer,” was – in addition to the exemplary effect of the Bildstelle headed by Lampe – an essential point of reference for the Urania’s programming and cinema reform policy.

According to Lampe, the cultivation of viewers was the result of a correctly understood cultivation of film content, i.e., one that reflected the conditions of the medium. If content that conveyed “scientific truths,” that had “aesthetic or ethical significance,” that fired the imagination, or that had an “edifying” effect51 basically met the requirements of culture, in the case of film it was additionally necessary to consider that element that constituted the core of its essence, movement. “If film culture recognizes its task correctly, then it will be conducive to the cultivation of such contents which are only brought to consciousness properly by the moving image.”52 Depending on whether this content was the mere “observation of movements,” the “interpretation of motifs and effects of movements,” or the perception of movements “that move too fast or too slow to be perceptible in reality,”53 it resulted in different effects on the viewers. These ranged from the simple training of the eye in the new conditions of moving visibility to a new form of connection between perception and thinking – Lampe’s “synthetic seeing” – and on to the “relaxation of emotional life and imaginative activity.”54

If in the first case it was a matter of mere habituation, synthetic seeing already represented a formal training of the mind: Because the moving image “only becomes clear in its totality when it has rolled past,” according to Lampe, it forces viewers to synthesize, which consists in “stringing all the parts together and combining them into a unity.”55 If the synthesis promoted the viewers’ ability to combine, the essential achievement of cinematic movement for Lampe, however, consisted in the fact that it triggered “emotional movements of the soul” in the viewers: “First of all, a movement attracts attention, then interest, and finally partisanship for or against what is being moved or against those who are moving, i.e. shared joy, pity, fear, and hope.”56 In this interplay of “mental tension and relaxation,” set in motion by the moving image, Lampe saw the ultimate reason why “viewers go to the cinema.” For the cultural film, he derived from this the demand that it should be less “sublimated than emotionally cultivated,”57 i.e., the cultural film should provide for a purification of the emotional life in terms of content by directing the interplay of emotional tension and relaxation to culturally valuable facts.

For Lampe, purifying the emotional life in terms of content meant, on the one hand, avoiding “gross violations of thought” and, on the other, influencing the direction of the will in the audience. The task of a rightly understood film culture would be, according to Lampe, “to educate a generation to feel strongly and accurately.”58 Against this background, the Urania’s screening practices unfolded their deeper meaning: the task of the slide lectures accompanying film screenings was not only to impart additional knowledge about the subjects and facts shown, but above all to intensify or weaken the interplay of mental tension and relaxation evoked by the moving image – depending on the perceived necessity. The editing of the films in the run-up to their screening therefore aimed, just like the lecture manuscript and the selection of lantern slides, at directing the emotional life of the viewers. Only in this way can it be understood that the lectures – including the historicizing introduction – carefully adapted their pertinent cues for understanding what was shown to the moods evoked by the moving images of the film. Just before the sequence in SHACKLETONS SÜDPOLEXPEDITION that showed the expedition ship, the Endurance, becoming trapped by pack ice, for example, the lecture manuscript stated: “The Endurance got caught in thicker and thicker ice floes. It was a nasty surprise to encounter such enormous masses of ice already here, and now begins the terrible battle against the elements that was to have such a sad end for the brave ship. The sky clouds over, it begins to snow.”59

As can be seen from the few surviving lecture manuscripts, the subordination of the moving image to the spoken word and the lantern slide was based on moods that were first and foremost evoked by these images. Apparently, this translation of film’s moods into the written word and still image was the only way to inspire the Urania’s educated bourgeois audience with enthusiasm for cultural film. Admittedly, the contribution that the Urania was able to make to building a film culture dominated by cultural films was limited to popularizing them. Only in rare cases did the Urania succeed in acting as a producer of cultural films itself, while the overwhelming majority of its program was made up of foreign productions. For the purification of the viewers’ emotional life, this circumstance created a painfully felt lack, to which, for example, the announcement of the first full-length cultural film produced by the Urania itself, AUS UNSERER ALPENHEIMAT / FROM OUR ALPINE HOMELAND (AT 1924), drew attention:

After the numerous films from almost all parts of the world which the Vienna Urania has shown we have always felt the obligation to give our homeland its due place in the cultural film; however, only a few and not too appealing pictures of this kind could be found on the film market. So, we decided to set an example ourselves and, after the many films from far and near, to capture the nearest homeland on film. After all, our Austrian fatherland offers so much of beauty and value – the richly shaped landscape with its magnificent mountains and lovely lakes and the loyal population in their picturesque traditional costumes and with their old, unspoiled customs.60

Not only because AUS UNSERER ALPENHEIMAT did not find the hoped-for success with audiences,61 the adaptation of film drama to the old Austrian folk culture propagated by Ludwig Koessler became a distant prospect. In 1920s Austria, there were only a few cultural film producers, who, moreover, usually produced short films.62 Thus, the emotional cultivation of cultural film was reserved for foreign productions, which determined what was available to the Urania for the selection of culturally valuable subject matter with films about (alpine) sports, about expeditions to parts of the world not yet explored, and about distant countries and foreign cultures. This situation changed only after the urging of Urania and other interest groups for government support of cultural film production was successful. Especially after the introduction of obligatory cultural films in 1934 by the Austrofascist Ständestaat, which were to be included compulsorily in the supporting program of commercial cinemas, Austrian cultural film production was perpetuated.63 The high proportion of cultural films that glorified the Austrian landscape, Austrian culture, and Austrian customs until the 1960s may illustrate the permanence of a film culture whose first model was created by the Urania and its film screenings with popular explanations. In defense of culture, this was less about enlightenment in the sense of adult education than about the purification of emotional life by way of the cinematic presentation of ‘appropriate’ subjects.

The research in this article was funded in whole by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) P 32343-G (Educational Film Practice in Austria).

- 1Anton Kaes, Nicholas Baer, and Michael Cowan, eds., The Promise of Cinema. German Film Theory 1907–1933 (Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2016), 9.

- 2Hartmut Bitomsky, “Der Kotflügel eines Mercedes-Benz,” in Kinowahrheit, ed. Ilka Schaarschmidt (Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2003), 40–100.

- 3Christa Blümlinger, Verdrängte Bilder in Österreich (Salzburg: PhD Thesis, 1986).

- 4Uli Jung and Martin Loiperdinger, eds., Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 1: Kaiserreich (1895–1918) (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005); Klaus Kreimeier, Antje Ehmann, and Jeanpaul Goergen, eds., Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 2: Weimarer Republik (1918–1933) (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005); Peter Zimmermann and Kay Hoffmann, eds., Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 3: ‘Drittes Reich’ (1933–1945) (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005).

- 5Jeanpaul Goergen, “Die Avantgarde und das Dokumentarische,” in Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland, Band 2, ibid., 493–526.

- 6According to Bill Nichols, the modern documentary arose from the historical confluence of photographic realism, narrative structures, avant-garde practices such as defamiliarization, and the use of rhetorical strategies in the early 1930s. Cf. Bill Nichols, “Documentary Film and the Modernist Avant-Garde,” in Critical Inquiry 27, no. 4 (Summer 2001): 580–610.

- 7Frank Kessler, “The Educational Magic Lantern Dispositif,” in A Million Pictures. Magic Lantern Slides in the History of Learning, ed. Sarah Dellmann and Frank Kessler (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020), 181–191; Eef Masson, Watch and Learn. Rhetorical Devices in Classroom Films after 1940 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012).

- 8Masson, Watch and Learn, 118.

- 9Yasuo Imai, “Film und Pädagogik in Deutschland 1912–1915,” in Bildung und Erziehung 47, no. 1 (1994): 89.

- 10Österreichisches Volkshochschularchiv (ÖVA), Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 5 (1921): 7.

- 11ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 6 (1921): 7.

- 12ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 18 (1921): 3.

- 13ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 6 (1921): 7.

- 14ÖVA, Urania Wien fonds, folder “Abteilung für Filme und Auswärtiges,” “Uraniafilme vom Februar 1921–29. Februar 1924.”

- 15ÖVA, Urania Wien fonds, folder “Abteilung für Filme und Auswärtiges,” Ludwig Koessler, “Kinoreform – Kinozensur,” unpublished manuscript (1923): 1.

- 16Ludwig Koessler, “Die aufbauende Kinoreform und ihr Verhältnis zur Filmzensur,” in Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 23 (1924): 2.

- 17ÖVA, Urania Wien fonds, folder “Abteilung für Filme und Auswärtiges,” Ludwig Koessler, “Lichtbild und Film in der Volksbildung,” unpublished manuscript (1925): 5.

- 18Ibid.

- 19Koessler, “Die aufbauende Kinoreform,” 3.

- 20Koessler, “Lichtbild und Film in der Volksbildung,” 6.

- 21Koessler, “Die aufbauende Kinoreform,” 5.

- 22Imai, “Film und Pädagogik,” 103.

- 23Ibid.

- 24The Kinoreformtagung took place from May 15 to 18, 1924, in the Great Hall of the Vienna Urania. The program and structure of the conference followed the idea of an exchange of experience between the Austrian and German educational film and cinema reform movements. In addition to Ludwig Koessler and Gustav Adolf Witt, the ministerial councilor responsible for film issues in the Austrian Ministry of Education, the head of the German Bildspielbund, Walther Günther, the head of the Bildstelle at the Zentralinstitut für Erziehung und Unterricht in Berlin, Felix Lampe, or the director of the Stettin public library, Erwin Ackerknecht, spoke. Fritz Lang, whose film DIE NIBELUNGEN (DE 1924) was shown at the conference, spoke on the subject of “The Artistic Structure of Film Drama,” Béla Balázs on “Film Criticism in the Service of Cinema Reform.” ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 19 (1924): 2–3.

- 25Cf. “Eine Erklärung des Bundes der Filmindustriellen,” Das Kino-Journal 721 (1924): 5.

- 26Béla Balázs, “Lichtbildung,” Der Tag, Mai 20, 1924, 1.

- 27Cf. Béla Balázs, Der sichtbare Mensch oder die Kultur des Films (Vienna: Deutsch-Österreichischer Verlag, 1924).

- 28Ludwig Koessler, “Film und Kultur,” Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 18 (1924): 4.

- 29Balázs, “Lichtbildung,” 1. Unfortunately, Balázs is silent about the reasons that led to the attacks.

- 30ÖVA, Urania Wien fonds, folder “Abteilung für Filme und Auswärtiges,” Letter from Ludwig Koessler to Friedrich Bauer, Adolf Hübl, and Karl Jäger dated November 18, 1924.

- 31Cf. ÖVA, Urania Wien fonds, folder “Abteilung für Filme und Auswärtiges,” “Uraniafilme vom Februar 1921–29. Februar 1924.”

- 32Heinrich Fuchsig, “Arbeitspause,” Das Bild im Dienste der Schule und Volksbildung 7/8 (1928): 126.

- 33Christian H. Stifter, “Der Urania-Kulturfilm, die Exotik des Fremden und die Völkerversöhnung,” Spurensuche 13, no. 1–4 (2002): 124.

- 34ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 27 (1921): 3.

- 35ÖVA, 632 “Shackletons Südpol Expedition,” lecture manuscript.

- 36Gustav Adolf Witt, Lichtbild und Lehrfilm in Österreich (Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1927), 78.

- 37Ibid.

- 38Ludwig Koessler, “Der Lehr- und Kulturfilm,” Neue Freie Presse (September 29, 1923): 15.

- 39ÖVA, 632 “Shackletons Südpol Expedition,” lecture manuscript.

- 40Koessler, “Der Lehr- und Kulturfilm,” 15.

- 41Cf. Imai, “Film und Pädagogik,” 95.

- 42ÖVA, 665 “König Dachstein,” lecture manuscript, 2.

- 43ÖVA, 747 “Wege zu Kraft und Schönheit,” lecture manuscript, 1–7.

- 44Cf. Tom Gunning, “Vor dem Dokumentarfilm,” in Kintop 4. Anfänge des Dokumentarischen Films, ed. Frank Kessler, Sabine Lenk, and Martin Loiperdinger (Frankfurt am Main: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern, 1995), 111–121.

- 45ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 29 (1928): 7.

- 46John Grierson, “Grundsätze des Dokumentarfilms,” in Bilder des Wirklichen. Texte zur Theorie des Dokumentarfilms, ed. Eva Hohenberger (Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2000), 103.

- 47ÖVA, 846 “Moana. Der Sohn der Südsee,” lecture manuscript, 1.

- 48Felix Lampe, “Kulturfilm und Filmkultur,” in Das Kulturfilmbuch, ed. Edgar Beyfuss and Alexander Kossowsky (Berlin: Chryselius & Schulz, 1924), 19.

- 49Koessler, “Die aufbauende Kinoreform,” 5.

- 50ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 19 (1924): 3. As late as June 1924, DER RHEIN IN VERGANGENHEIT UND GEGENWART / THE RHINE IN PAST AND PRESENT (DE 1922), for which Lampe had written the screenplay, was shown under the title DER RHEIN, DER STROM DES DEUTSCHEN SCHICKSALS in the cultural film program of the Urania, and in October 1924 Lampe gave two film lectures on “Berlin” and “Japan.” Cf. ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 21 (1924): 3; ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 35 (1924): 5.

- 51Lampe, “Kulturfilm und Filmkultur,” 19–20.

- 52Ibid., 22.

- 53Ibid.

- 54Ibid., 23.

- 55Ibid.

- 56Ibid., 25.

- 57Ibid.

- 58Ibid.

- 59ÖVA, 632 “Shackletons Südpol Expedition,” lecture manuscript, 7.

- 60ÖVA, Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania 34 (1924): 3.

- 61ÖVA, Urania Wien fonds, folder “Abteilung für Filme und Auswärtiges,” Letter from Ludwig Koessler to Friedrich Bauer, Adolf Hübl and Karl Jäger dated November 18, 1924.

- 62Cf. Karin Moser, Der österreichische Werbefilm. Die Genese eines Genres von seinen Anfängen bis 1938 (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2019).

- 63Cf. Wolfgang Walter, Die Kulturfilme des österreichischen Ständestaates (Vienna: Diploma Thesis, 2008).

Balázs, Béla. Der sichtbare Mensch oder die Kultur des Films. Vienna: Deutsch-Österreichischer Verlag, 1924.

Balázs, Béla. “Lichtbildung.” Der Tag (20. Mai 1924): 1.

Bitomsky, Hartmut. “Der Kotflügel eines Mercedes-Benz.” In Kinowahrheit, edited by Ilka Schaarschmidt, 40–100. Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2003.

Blümlinger, Christa, Verdrängte Bilder in Österreich. Salzburg: PhD Thesis, 1986.

Fuchsig, Heinrich. “Arbeitspause.” Das Bild im Dienste der Schule und Volksbildung, no. 7/8 (1928): 125–126.

Goergen, Jeanpaul. “Die Avantgarde und das Dokumentarische.” In Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 2: Weimarer Republik (1918-1933), edited by Klaus Kreimeier, Antje Ehmann, and Jeanpaul Goergen, 493–526. Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005.

Gunning, Tom. “Vor dem Dokumentarfilm.” In Kintop 4. Anfänge des Dokumentarischen Films, edited by Frank Kessler, Sabine Lenk and Martin Loiperdinger, 111–121. Frankfurt am Main: Stroemfeld/Roter Stern, 1995.

Grierson, John. “Grundsätze des Dokumentarfilms.” In Bilder des Wirklichen. Texte zur Theorie des Dokumentarfilms, edited by Eva Hohenberger, 100–113. Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2000.

Imai, Yasuo. “Film und Pädagogik in Deutschland 1912–1915.” Bildung und Erziehung 47, no. 1 (1994): 87–106.

Jung, Uli and Martin Loiperdinger, eds. Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 1: Kaiserreich (1895–1918). Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005.

Kaes, Anton, Nicholas Baer and Michael Cowan, eds. The Promise of Cinema. German Film Theory 1907–1933. Oakland, California: University of California Press, 2016.

Kessler, Frank. “The Educational Magic Lantern Dispositif.” In A Million Pictures. Magic Lantern Slides in the History of Learning, edited by Sarah Dellmann and Frank Kessler, 181–191. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020.

Koessler, Ludwig. “Der Lehr- und Kulturfilm.” Neue Freie Presse (29. September 1923): 15.

Kreimeier, Klaus, Antje Ehmann, and Jeanpaul Goergen, eds. Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 2: Weimarer Republik (1918–1933). Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005.

Lampe, Felix. “Kulturfilm und Filmkultur.” In Das Kulturfilmbuch, edited by Edgar Beyfuss and Alexander Kossowsky, 19–27. Berlin: Chryselius & Schulz, 1924.

Masson, Eef. Watch and Learn. Rhetorical Devices in Classroom Films after 1940. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012.

Moser, Karin. Der österreichische Werbefilm. Die Genese eines Genres von seinen Anfängen bis 1938. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 2019.

Nichols, Bill. “Documentary Film and the Modernist Avant-Garde.” Critical Inquiry 27, no. 4 (Summer 2001): 580–610.

Stifter, Christian H. “Der Urania-Kulturfilm, die Exotik des Fremden und die Völkerversöhnung.” Spurensuche 13, no. 1-4 (2002): 114–148.

Walter, Wolfgang. Die Kulturfilme des österreichischen Ständestaates. Vienna: Master Diploma Thesis, 2008.

Witt, Gustav Adolf. Lichtbild und Lehrfilm in Österreich. Vienna: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1927.

Zimmermann, Peter and Kay Hoffmann, eds. Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 3: 'Drittes Reich' (1933–1945). Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005.