Issue 5: Educational Film Practices

After a long period of neglect by archives and scholars, the varied histories of educational film have been the subject of investigation and re-evaluation since the turn of the millennium. In a few key publications, educational film has been shown to have developed not just a robust variety of generic subtypes, modes of production, distribution, and presentation, but also impacted broader discussions of film and its place in society, as well as engendered new epistemological questions.1

Recent uses of the moving image in educational contexts – from the proliferation of online formats like how-to and explainer videos to the extensive use of video for home schooling and e-learning during the Covid lockdowns – have highlighted the issues of adapting films and videos to fit educational settings and pedagogical aims. Vice versa, film and video have also posed considerable challenges to the spatial, temporal and institutional structures of education as well as concepts of learning and teaching. Then as now, the use of the moving image for instructional, informational, and pedagogical purposes is accompanied by lively debates about the implications of image- rather than text-based knowledge transfer. These discussions often oscillate between high hopes for the educational capacity of the moving image and warnings of the dissipation of knowledge into audio-visual entertainment. The issue Educational Film Practices interrogates these debates by focusing on practices of film use.

This collection of essays aims to move beyond the state of research into so-called ‘useful cinema’ by engaging with educational film as a prolific historical source and methodological testing ground for writing film history as a historiography of practices. The concept of practice serves here as a mid-level notion in between the scopes of structures and individual acts2 which highlights the situated, processual3 and “non-rationalist”4 dimensions of media usage and its organisation. This notion of practice is conducive to elucidating at least three key specifics that have turned up repeatedly in histories of educational film in a variety of places and timeframes. First, researchers have often found a push-and-pull between localized initiatives and attempts at professionalization and centralization. Efforts at (state, federal, and international) institutionalization have been shown to both encourage and police small-scale, semi-amateur attempts to make, distribute, and present educational films (see Marie-Noëlle Yazdanpanah’s contribution on this topic). Writing a history of educational film practice means not only writing an institutional history, even if the key institutions’ archives often provide a majority of records, but also leaving room for traces of divergent or deviant practices in uneasy relationships with efforts at institutionalization.

Second, educational film is a prime example of a generic category that, far from being merely a neutral descriptor or even an aspirational label, has been a key part not only of debates, but also of legal, institutional, and policy procedures. What constitutes a ‘proper’ educational film and what financial benefits (such as tax exemptions) derive from that label – these topics have been the subject of extensive law- and policy-making as well as elaborate procedures of committee evaluation and inter-organizational contest. This policing of the confines of educational film (often against the areas of commercial cinema and corporate advertising) has produced a rich history of neologisms that refer to specific types of educational tasks and contexts: classroom film, safety film, information film, in German also Diskussionsfilm, Impulsfilm, Beratungsfilm. It has also motivated pedagogues to develop elaborate taxonomies that systematize film genres and types in terms of their educational usefulness.5 As this issue’s articles by Kerrin von Engelhardt and Lena Serov demonstrate, the institutional networks and particular interests that shaped educational films frequently involved efforts to evaluate and measure film’s impact on audiences. Scientific audience research and the use of educational films were frequently set up to feed into each other under the umbrella of public or private media policies.

Third, pedagogues as well as filmmakers often understood the educational value of a film not as a fixed feature of the form, style, and content of the media object; rather, they expected it to develop via the setting of the screening as well as its wider institutional context. In the articles collected here, these contexts range from compulsory schooling to vocational training for professionals or aesthetic modes of popular education. There is even more variety in the spatial settings, accompanying performances, and media involved in the co-production of the institutionally intended effects of film screenings. They can involve complex interplays between films, slides, spoken lecture texts, and musical accompaniments during a screening (as in the example studied by Vrääth Öhner), or a broader set of aesthetic experiences and research exercises involved in exploring a topic that might even de-center the screening event as the key to the educational value of a film experience’s (as in Christian Dewald’s reconstruction of holistic strategies of reform pedagogy). Even beyond investigations into the “performance dispositif” of film screenings,6 a focus on practices rather than objects helps to foreground the organizational and material conditions of film usage: be they shifting archival regimes and distribution policies (as in Anja Sattelmacher’s study), or even the film stock itself, its economic preconditions and aesthetic affordances (as explored by Jonathan Haid). Similarly, the diverse disciplinary backgrounds and epistemological interests of the producers, presenters, and audiences of educational films bring with them context-specific concerns and concepts that may alter the relevant understanding of what was supposed to be done with films.

On a methodological level, writing film history as a history of practice might also contribute to unlearning the “recuperative and preservative paradigms” of cinema studies.7 With this term, Katherine Groo has identified an enduring drive in film historiography (including New Film History) to keep the fragmentary and often baffling viewing experience of archival footage at arm’s length by filling in its underdetermined strangeness with contextual information. This is done, among other things, by keeping the (often unavailable) ‘original state’ of the footage as a heuristic point of orientation. Groo argues for a historiography of film that is more concerned with tracing ongoing movements of mutation than with the comforting notion of the ‘film work’ as a stable final product (of its history of production) and restorable origin (of its history of reception). Again, many educational films make for a promising test case, as dynamic documents with a remarkable tradition of appropriating, excerpting, recycling, and re-combining footage and coupling film into (makeshift or neatly packaged) media mixtures.

Overview of the Contributions

In keeping with the journal’s aims, the first article focuses on historical issues: Anja Sattelmacher tracks how the film THEODOR ESCHENBURG SPRICHT – a 1970 seminar recorded for educational re-use – transforms from a lecture on contemporary history to an instructive historical film document. She studies not only the changing meaning of Eschenburg’s statements, but also the changing conditions of archiving and distribution that impacted the scenarios of use.

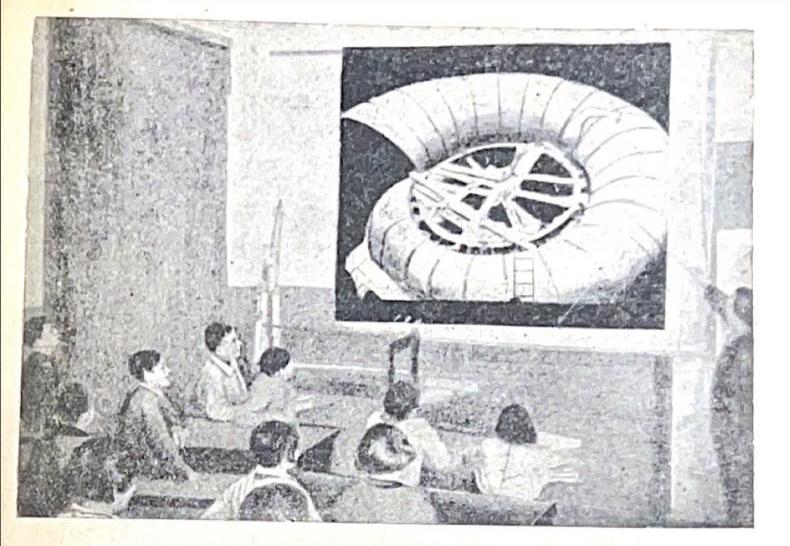

In the second contribution to this issue, Vrääth Öhner investigates the historicity of a particular dispositif (in the Foucauldian as well as Kessler’s meaning of the word) of film presentation: The multimedia screening practices of Vienna’s Urania, a prominent site of popular education in Central Europe during the 1920s, are interpreted here as an aftereffect of the cinema reform movement’s earlier mingling of education and emotional purification.

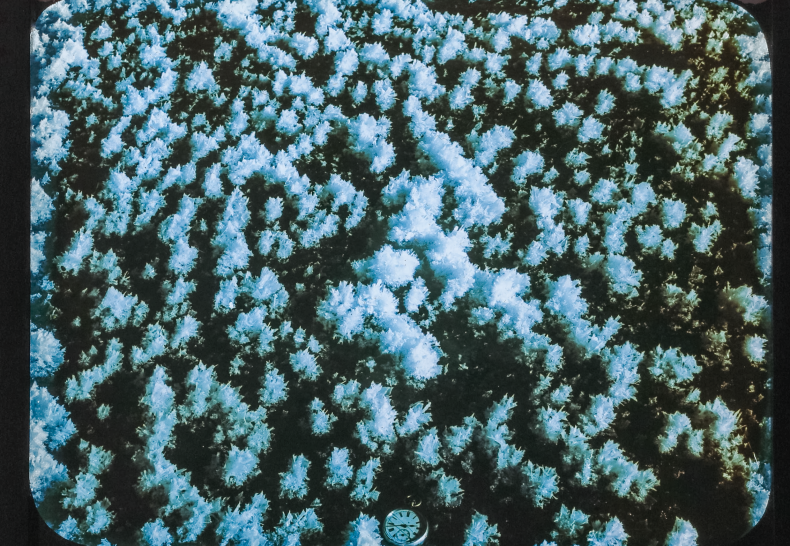

While Öhner sifts through a range of different media objects, Jonathan Haid delves deep into the material components of one substrate – celluloid film – and elucidates its entanglements in German economic policy. This material history of film is juxtaposed with a reading of the propagandistic Kulturfilm DIE WELTGESCHICHTE ALS KOLONIALGESCHICHTE (1926), which is shown to engage with its material base on both a thematic and a stylistic level.

Christian Dewald’s contribution aims to draw on pedagogical theory not just as an afterthought or supplement to a media history of educational film. Instead, he explores the place of “school cinema” within the educational framework of a model school in 1920s Vienna, the Federal Educational Institute Vienna-Breitensee, by drawing on the institution’s history as well as the concepts of reform pedagogy from which this school drew.

While examining interwar Austria as well, Marie-Noëlle Yazdanpanah does not focus on the tension between our understandings of pedagogical and cinematic dispositifs. Instead, she explores the complex relationship between bottom-up teachers’ initiatives and efforts to centralize and standardize the production, distribution, and presentation of educational films. As she demonstrates, this relationship was often played out, spatially and thematically, as one between the capital city of Vienna and the other provinces of the newly formed, post-WWI First Austrian Republic.

The next pair of articles provides valuable contributions to a more international and diachronic perspective on the institutionalization of film in schools over the 20th century, while staging different methodological maneuvers. Lena Serov traces the consolidation of classroom film in 1930s Soviet Russia from a more general program of the “cinefication” of public life that included schools, to the more specialized pedagogical methodology of developing “film lessons.” For the case of the German Democratic Republic, Kerrin von Engelhardt argues for the usefulness of the concept of a “grammar of schooling” from the educational sciences to explain where ambitious state programs for classroom film diverged from their documented actual application.

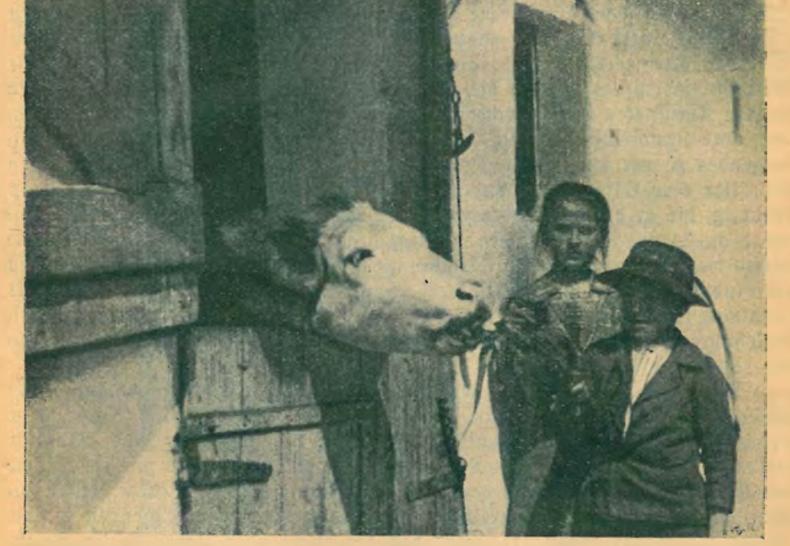

While one half of the articles in this issue deal with educational film in the school context, the final contribution aims to draw attention to the breadth of modes and sites of learning and teaching covered by the umbrella term of ‘educational film.’ Joachim Schätz examines the use of films in the ongoing professional training of farmers in 1950s and 1960s Austria. This may also serve as a final reminder that “educational film” is less the name of a preexisting stable entity than an indication of certain things being done with films.

We thank all contributing authors for their expertise, graciousness and willingness to delve deep into the topics, and archives, they chose. The experience of working with them on this issue was alike to what has often been promised and rarely been true about educational films: always instructive, and not for a second boring!

Joachim Schätz and Katrin Pilz

Vienna, July 10, 2023

Suggested Citation: Pilz, Katrin, and Joachim Schätz. “Issue 5: Educational Film Practices. Editorial.” Research in Film and History 5 (2023): 1–8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/22729.

- 1See for example: Devin Orgeron, Marsha Orgeron, and Dan Streible, eds., Learning with the Lights Off: Educational Film in the United States (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012); Klaus Kreimeier, Antje Ehmann, and Jeanpaul Goergen, eds., Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Band 2: Weimarer Republik (1918–1933) (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2005); Eef Masson, Watch and Learn: Rhetorical Devices in Classroom Films after 1940 (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2012).

- 2See: Lukas Haasis and Constantin Rieske, “Historische Praxeologie. Zur Einführung,” in Historische Praxeologie. Dimensionen vergangenen Handelns, ed. Lukas Haasis and Constantin Rieske (Paderborn: Schöningh, 2015), 13.

- 3See: Mark Dang-Anh, Simone Pfeifer, Clemens Reisner, and Lisa Villioth, “Medienpraktiken. Situieren, erforschen, reflektieren. Eine Einleitung,” Navigationen 17, no. 1 (2017): 18–21.

- 4Andreas Reckwitz, “Grundelemente einer Theorie sozialer Praktiken. Eine sozialtheoretische Perspektive,” Zeitschrift für Soziologie 32, no. 4 (2003): 289.

- 5For both mentioned aspects, see Anita Gertiser’s overview on the institutional history of Swiss classroom film: Anita Gertiser, “Schul- und Lehrfilme,” in Schaufenster Schweiz: Dokumentarische Gebrauchsfilme, ed. Yvonne Zimmermann (Zurich: Limmat, 2011), 384–513. For inter-institutional contest over what constitutes an acceptable educational film, see pages 388–389; for taxonomies of film, see the image on page 455.

- 6This term was proposed by Frank Kessler, on the basis of an ongoing pragmatic operationalization of the concept of the cinematographic dispositif by, among others, Kessler and Eef Masson. See: Frank Kessler, “The Educational Magic Lantern Dispositif,” in A Million Pictures: Magic Lantern Slides in the History of Learning, ed. Sarah Dellmann and Frank Kessler (New Barnet: John Libbey, 2020), 181–191.

- 7Katherine Groo, Bad Film Histories: Ethnography and the Early Archive (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2019), 100.