The Austrian Province as Subject and Space of Action in Educational Film Practices

Table of Contents

Screening Propaganda

In Defense of Culture

The Raw Materials of Celluloid Film

Wholeness and Nature

The Austrian Province as Subject and Space of Action in Educational Film Practices

The Development of Educational Cinema for Schools in the Soviet Union in the 1930s

Educational Film in East Germany (GDR) in 1950–1990 in Perspective of the “Grammar of Schooling”

No Instructions, Just Some Advice

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Yazdanpanah, Marie-Noëlle. “The Austrian Province as Subject and Space of Action in Educational Film Practices.” Research in Film and History 5 (2023): 1–41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/22728.

Intro

(1) This film fulfils its educational and instructional purposes. For those who have seen the abundance of blessings, the name Burgenland will no longer be an empty sound; but the film also has a social-ethical effect, it should build a bridge between town and country and plant respect for farm work in the hearts of the children. (Heinrich Fuchsig, 1925)1

(2) The educational and instructional film will be indispensable especially for rural schools, which are often still cut off from the wider homeland and the city. On the other hand, city schools will also gain a lot from good films that show settlements, life and work of the rural population and help to build bridges between city and country and achieve mutual understanding. (Hans Zach, 1935)2

The two media educators quoted here agreed: In their eyes, educational film acts as an intermediary between city and country, promoting understanding and acceptance by bringing the world to the viewers.3 Both, Viennese teacher Heinrich Fuchsig and Hans Zach, senior member of the Styrian Regional School Board, were involved in independent initiatives to anchor film in Austrian schools: The activities of the Film- und Bildarbeitsgemeinschaft der Lehrer Wiens (roughly translated as Vienna Teachers’ Film and Image Working Group) in the mid-1920s as well as the Steirische Schulen-Arbeitsgemeinschaft für den Heimatkundlichen Unterrichtsfilm (Styrian Schools Working Group for the Educational Film on Local History) about ten years later included (with different emphasis) re-editing films for educational purposes, publishing books and magazines, producing supplementary teaching materials such as leaflets (Handreichungen), distributing films and equipment, and above all a variety of networking such as organising conferences and teacher training courses as well as producing their own films. As proponents of educational film, its members believed that film, through its vividness, its alleged closeness to reality (Wirklichkeitsnähe) and ability to present things and processes that would otherwise be inaccessible to teaching was highly useful; especially for subjects that required empathy and were difficult to convey through tools or methods often described as abstract – such as written or spoken words and maps. The teaching of different lifeworlds, the knowledge of one’s own homeland and civic education were considered as such. And the medium of film, which was said to have an immediate effect on the emotional level, was therefore considered ideal.4

This article focuses on measures to anchor film as a teaching tool in 1920s and 1930s Austria concentrating on the relationship between the urban centre and the predominantly rural province: First, the centre’s cinematic view on the periphery is examined based on the film referred to in the first quote: LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE / LIFE IN A BURGENLAND PEASANT VILLAGE (AT 1925).5 I investigate how the film presents the new Austrian province Burgenland as an agriculturally rich region to an urban audience, particularly schoolchildren, and what these choices were meant to signify. Secondly, I will look at independent local initiatives, examining both their views on film as a mediator and their relationship to the centre: What was the institutional centre’s attitude towards regional independent bodies and actors and vice versa? How were competences negotiated or allocated? Using LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE in the context of other educational films produced by teachers and investigating activities of regional actors, I will elaborate on political agendas and processes of negotiation and institutionalisation, a focus being scopes of action. Thus, on the one hand, processes of institutionalisation and standardisation of educational film, which took place internationally at about the same time in Europe and North America,6 are examined, using the example of regional initiatives in Austria. Taking a cue from concepts of “practice” in the lineage of Michel de Certeau,7 an account of practices and processes of institutionalisation should include, if possible, evidence of resistant or deviant actions – in this case by local bodies. My contribution therefore considers sources and perspectives that make leeway and processes of negotiation, conflicts and frictions visible. On the other hand, using the example of an educational film produced by an independent Viennese initiative that represents the centre’s view of the “unknown” periphery, I look into early practices of educational film and show how the medium of educational film could at the same time be as vivid and factual as the media educators demanded and serve both as a tool for civic education and as a vehicle for nationalist rhetoric. The article is mainly based on activities and statements of the educational film actors of the time, drawing on contemporary published and archival sources (films and texts).

Educational Film as a Collaborative Effort for Nation Building

LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE was created collaboratively to initiate the independent production of educational films in Austria based on the school curricula and to gain institutional support for implementing film as a teaching tool. One of the cinematographers described the working process as an often difficult and tedious but lively democratic practice that helped widen perspectives: teachers would normally evaluate films instead of dealing with the material itself; practical endeavours such as making their own films would help develop media education further.8 The filmmakers, Viennese teachers and other educational film activists, were members of the already mentioned Film- und Bildarbeitsgemeinschaft der Lehrer Wiens founded in 1923. During the 1920s the Schulkinobund, as the group called itself from the mid-20s onwards, became one of the key initiatives of educational film in interwar Austria and as such was successfully involved in its institutionalisation. It cooperated closely with the Ministry of Education and the Vienna Urania: in 1928, for example, it funded the Österreichisches Unterrichtsfilm-Archiv, the Austrian Educational Film Archive at the Urania; it rented out Urania films throughout Austria and members partook in the ministry’s film commissions tasked with evaluating films or taught in seminars in which teachers were trained as film projectionists. Together with these two institutions – the Vienna Urania and the Ministry of Education – the Schulkinobund shaped Austrian educational film activities and discourses roughly until the mid-1930s. News and debates were shared via the Schulkinobund’s magazine Das Bild im Dienste der Schule und Volksbildung. Monatsschrift für zeitgemäße Verwendung von Bild, Lichtbild und Film. Mitteilungsblatt der Film- und Bildarbeitsgemeinschaften der Lehrer Österreichs (The Picture in the Service of School and Popular Education. Monthly Journal for the Contemporary Use of Picture, Slide and Film. Newsletter of the Film and Slide Working Groups of Teachers in Austria; 1924–1930). The title provides ample information on the journal’s focus which is an important source for thoughts and activities on employing film in Austrian schools. It is also one of the main sources for information on the production and use of LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE.

Marketed as the first educational film made by teachers in Austria9 and as a significant step for the “absolutely necessary bodenständige [down-to-earth] and heimatkundliche [concerned with local history] educational film,”10 it was considered a showcase project: Recommended by the Vienna City School Board,11 the film was also presented at national and international conferences.12 With the province of Burgenland, the filmmakers chose a highly topical subject: The film premiered in 192513 – only two years after the final incorporation of parts of the former Deutsch-Westungarn, Western Hungary, into Austria as its easternmost and ninth province. Burgenland was a highly contested space in a country whose sovereignty was permanently questioned and that predominantly was perceived as being in an almost constant state of crisis: The process of incorporation lasted from 1921 to 1923 and was accompanied by armed disputes between the Austrian police and Hungarian paramilitary fighters who were (unofficially) backed by the conservative right-wing government of Miklós Horthy.14 Burgenland was also the site of embittered conflicts about Austria’s democratic constitution, escalating in 1927 in the Schattendorf killings, when right-wing combat veterans shot two people during a confrontation with Social Democrats in the border village Schattendorf. Their acquittal by a grand jury was the cause of the July revolt and the burning of the Vienna Palace of Justice in 1927.15 This incident terminated the relatively peaceful years in the mid-1920s when LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE was produced. The majority of the political parties and most of the media deemed the new small state of Austria unable to exist independently. Burgenland as the only significant territorial gain of the new Republic was presented as being of great importance, even though only parts of the original province became Austrian, and Sopron, its economic, political and cultural centre, remained with Hungary due to a referendum. In any case, the new province was supposed to defuse the perception of Austria as an economically unfit country dependent on imports: a main argument put forward was that Burgenland would provide Austria, especially Vienna, with much needed food. Thus, it was promoted as Austria’s new granary that could replace the lost fertile areas in the east of the former monarchy.

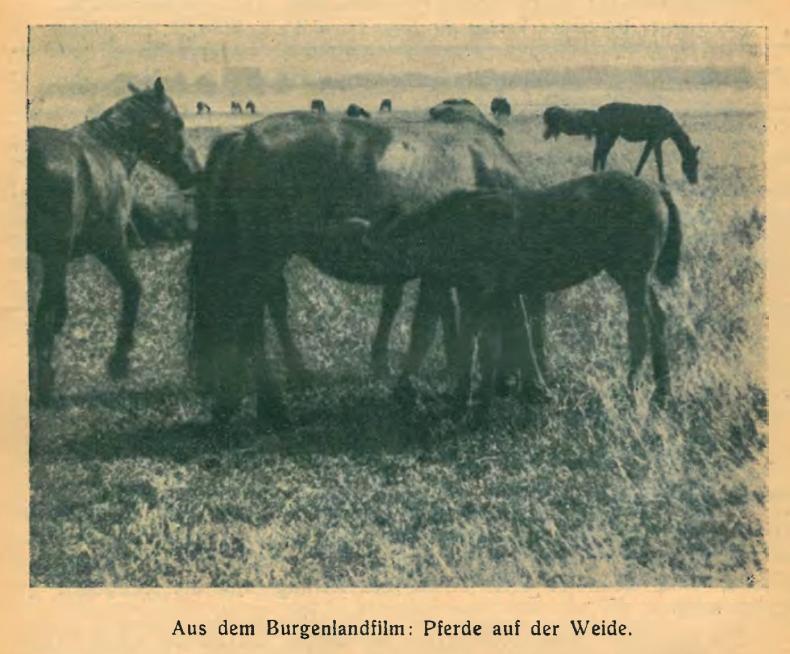

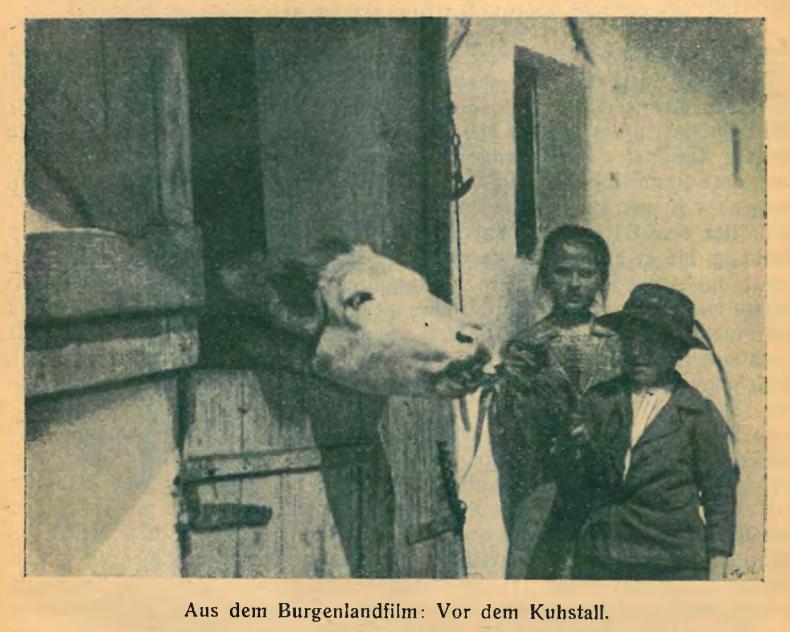

This is how the new territory is also presented in LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE and what Heinrich Fuchsig refers to in the above-cited statement. The film aimed to introduce a new and predominantly rural part of the Austrian homeland to Viennese children, so that they would recognise the benefits for the small state in which they now lived, instead of remaining indifferent. The people involved in the production thus explicitly pursued a (state) political agenda: “The film (...) is intended to contribute to an uplift of national sentiment.”16 It presented a seemingly never-changing circle of life in a rural village, into which few elements of modernity have found their way through machines, but not concerning communal life. Its five parts, the order of which changed several times through re-editing, show workers and animals leaving the farm, work at the farm, animals on pastures, work in the field, ending with wildlife and leisure time on Sundays and traditional festive days.17 Several times the camera pans across wide landscapes and over “huge herds of cattle, horses and geese (…) in seemingly endless succession.”18 Often employing long, static shots, the film observes elaborate tasks such as threshing, highlights unusual objects such as the production of enormous haystacks or depicts trickling grain in a close-up. With this, the film aimed to give an impression of richness and productivity. However, this was inaccurate, because due to outdated methods, a lack of infrastructure and above all ownership structures the harvest yields of Burgenland’s agriculture fell far short of expectations. About half of the area and roughly 2/3 of the farms were either small subsistence farms or large estates, the latter of which were often divided by the new border and therefore economically unsuccessful.19 In fact, Burgenland was Austria’s poorest province: A region of emigration since about 1900, the second least populous province in Austria accounted for 43 percent of the state’s total emigration in 1923.20

The “Other” Becoming One’s Own

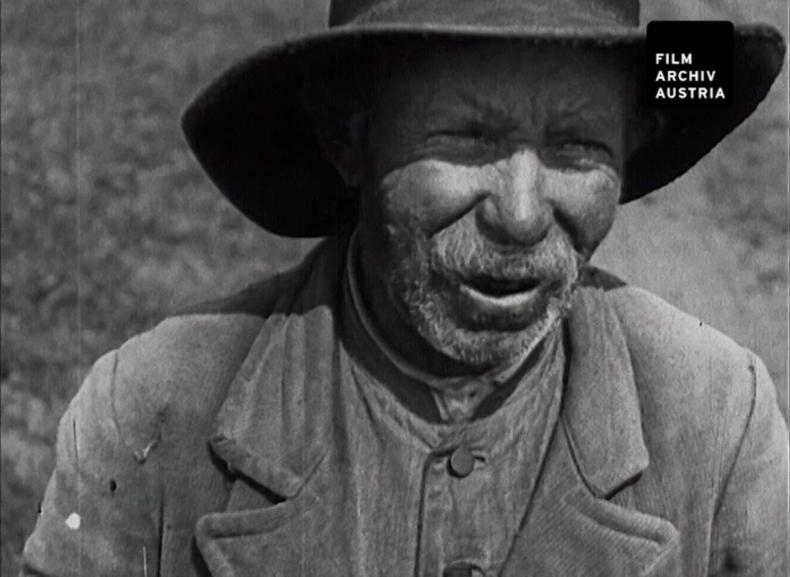

The film’s setting, the Heideboden near Lake Neusiedl, predominantly belonged to large landowners who employed farm workers. The film reflects this without explicitly naming it: It presents agricultural work as communal and instead of focusing on a single peasant family, as is often the case in cultural or educational films about agricultural communities, the workers are portrayed as a collective. Generally, relationships are not explained, the only exception being the two shepherds who are labelled as “the father” and “the son” in the intertitles.

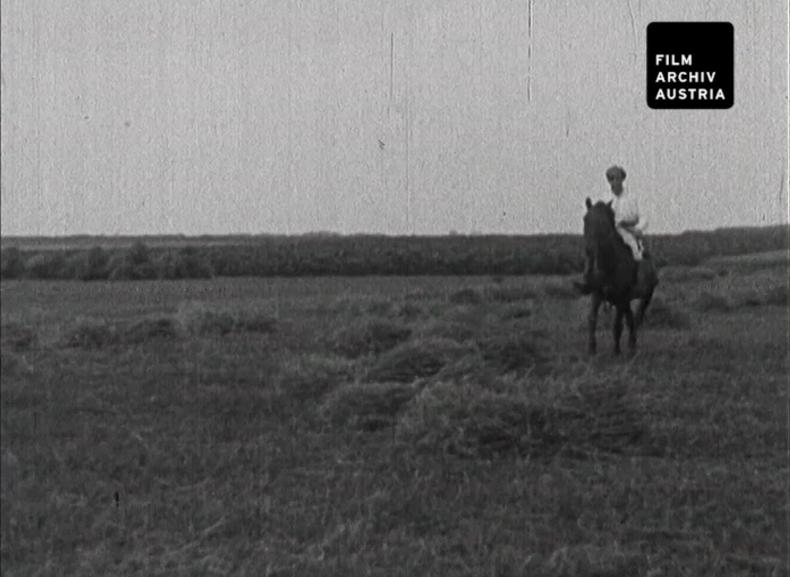

Here the film resembles genre art and is reminiscent of paintings depicting country life or peasants; but even more so: by focusing on the shepherds’ physiognomy in long close-ups, the camera adopts an ethnographic, typologising gaze. These shots thus not only represent the urban centre’s view of the rural periphery, which, with the exception of shots of a modern threshing machine, is shown as a pre-modern community and as an apparent contrast to urban life. They also reflect contemporary Austrian discourses in which Burgenland was presented as foreign, somewhat backward “East.”21 Other examples for this are a horseback-rider who functions as a typical representative of the iconic Hungarian (and Burgenland) plains, the Puszta, and sieve makers resting on the roadside as “typical” representatives of Romani people. Moreover, with the vast and flat Heideboden that part of Burgenland was chosen which differs most from the predominantly mountainous and hilly landscape of Austria.

the iconic landscape of the Hungarian Puszta.

This otherness was emphasised in some reviews and statements by the filmmakers, such as when one of the cameramen presents the shooting as an expedition of daring pioneers who arduously conquered the unfamiliar country for an urban audience, describing the area as follows:

The extremely characteristic “Heideboden” with its vast fields, numerous lakes, dense reed beds and endless meadows, the so-called “Wasen” ([according to] Hanschak), and the farmers themselves, with their peculiar customs and traditions, provided the best possible preconditions. (…) Hence it was possible to capture on film both the Burgenländer at work and in their other behaviour, as well as the hamster at its harvest, the skylark in the field, the interesting European ostrich, the bustard, the stork in the nest on the chimney and many more for the Viennese schoolchildren.22

Austria’s territorial claims against Hungary were not only justified economically, but also with the alleged centuries-old “German character” of Burgenland. However, the province was – and to a lesser extent still is – inhabited by German speakers, Hungarians, Croats and Romani;23 and since the 14th/15th century several Jewish communities have been documented, the most continuous in the area of present-day Austria.24 In LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE neither the images nor the intertitles name origins or nationalities and no explicit political judgements are given. Yet, in his review Ferdinand Lettmayer – geography teacher, member of the Schulkinobund and part of the film’s advisory team – refers to the Heideboden as “ancient German property” and labels its inhabitants as “Franconian”25 which meant belonging to Austria. But this notion of ethnic belonging does not dominate the film.

But this was exactly the case in another (educational) film on Burgenland, BILDER AUS DEM BURGENLAND (AT 1931) which was compiled of material from several Burgenland films and distributed by the national educational film institution ÖLFD, the Austrian Slide and Film Services, a suborganization in the Ministry of Education, on occasion of the 10th anniversary of Austrian Burgenland. The film not only addresses the conflicts surrounding the incorporation of Burgenland but depicts it explicitly as German. Diversity in the sense of otherness is stressed by focusing on certain groups of inhabitants. Croats and Hungarians are portrayed as riders or idle pipe smokers, whereas the Jewish community is presented as a traditionally segregated group. These minorities lack representations of productivity, especially the Romani. Contemptuously called “elements” they are portrayed as poor, filthy and potentially criminal and serve as the biggest contrast to the majority population, the Germans (meaning German-speaking Christians): depicted as hard-working, traditional, cheerful people, they embody “the real” Burgenland and end the film as a positive culmination.

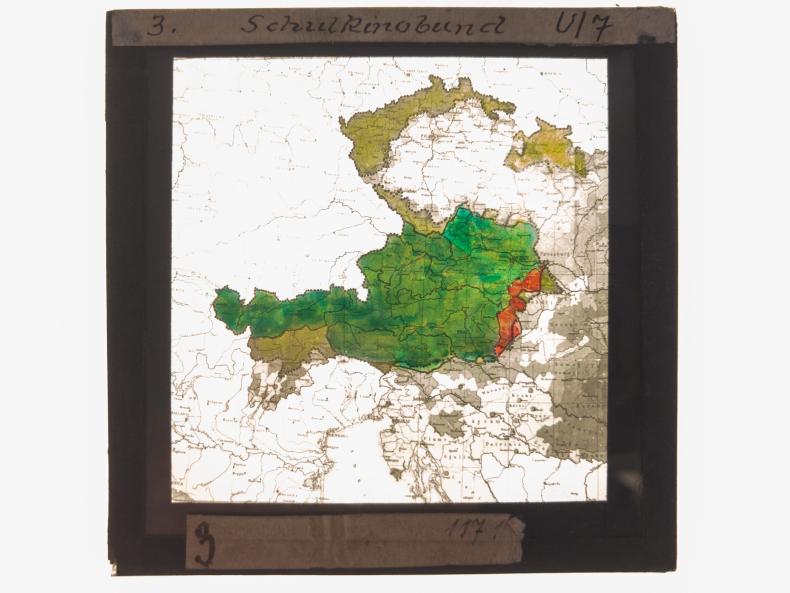

It was a widespread and recommended educational practice to integrate films into media packages with slides, maps, objects, etc. which were introduced and commented on by teachers or lecturers. Educational films were also re-edited, shortened, and, depending on the area of use, intertitles were adapted; sometimes sequences from various films were compiled: In 1925 scenes depicting animals and fieldwork from LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE for example were included in the educational film BÄUERLICHES LEBEN IN ÖSTERREICH / RURAL LIFE IN AUSTRIA.26 LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE was accompanied by 31 slides.27

A single one preserved in the Urania Archive depicts a map of the new Republic of Austria (green) with the claimed German-speaking areas outside the national territory (ochre) and Burgenland (red), indicating a political framing that formulates language affiliation as decisive for state membership. Nevertheless, compared to other educational film programmes about Burgenland such as BILDER AUS DEM BURGENLAND, labelling and ranking the people portrayed or characterising the landscape as German in order to claim it does not seem to have been the dominant approach. Rather, what is unusual or “Other” from an urban Viennese perspective is presented as typical of Burgenland (although it was characteristic of the Heideboden and not the whole province). Even more so, the diversity and productivity of this rural unknown territory was offered in such a way that urban audiences accepted it as an important asset to their homeland, which then would lead to an “uplift of national sentiment” – this at least was the pronounced agenda. Lettmayer thus allocated the film to the context of civics and local history (Staatsbürgerkunde, Heimatkunde). For educators in 1920s Austria, the task of civic education was to educate pupils to become self-confident citizens who believed in the(ir) state, “by considering what bears comparison with other states,”28 as Lettmayer puts it in an article about utilising film in geography lessons. The children were supposed to develop “political and economic judgement” as well as “a love for their homeland,”29 which could be achieved ideally through the vividness and intuition (Anschaulichkeit and Anschauung) of film. In conclusion, with the first film initiated by the Film- und Bildarbeitsgemeinschaft der Lehrer Wiens, civic education, identity formation and emotional commitment to the new Austria, a trust in and love for the homeland (and its people) was meant to be accomplished through the depiction of Burgenland’s fertile agriculture and the work of farmers and farm laborers.

Traces of the overall film’s screening history (except for Viennese school cinemas in the 1920s), and especially sources indicating whether its agenda was successful, are few and far between. On the one hand, mainly the people involved, either the filmmakers themselves or supporters such as Lettmayer or Heinrich Fuchsig, commented on the film and its impact. On the other hand, several films were made about the Austrian Burgenland from the 1920s onwards, the titles of which were very similar. In the surviving paper trails (announcements, short reviews in print media, minutes, and correspondence on Burgenland film projects in archives) the titles were often abbreviated to “Burgenland film” without indicating which one was meant. LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE was also referred to as “Burgenland film” several times. Therefore, its screening history and reception outside the circle of its producers and immediate supporters cannot be clearly reconstructed. It is at least certain that the film was shown at the Urania outside the school cinema context on the occasion of the 10th anniversary of Burgenland in 1931/32 and again in 1933/34, the first year of Austrofascist dictatorship, as part of a Burgenland lecture consisting of several films, slides and records.30

Negotiating Forms of Engagement and Collaborations

Teachers and popular educators in Austria had set up independent associations to establish films and slides in schools and popular education as early as the 1910s.31 However, the founding of Film- und Bildarbeitsgemeinschaft der Lehrer Wiens in 1923 happened when film was finally establishing itself as a mass medium and the discussion about its positive as well as its allegedly endangering qualities was particularly lively (see the Cinema Reform Movement, including a Conference in May 1924 at the Vienna Urania).32 This was a time when the Urania was introducing a public education film programme, the Urania-Filme mit volkstümlicher Erläuterung (Urania Films with Popular Explanations),33 and when new educational concepts (above all the working school) were being debated and implemented, and considerations and activities to organise and institutionalise educational film (and slides) were intensifying. Contemporary accounts and archival sources attest to numerous parallel initiatives of varying size and duration of existence in addition to the already mentioned Schulkinobund. Among them were many by teachers who organised screenings, put together series of slides or made their own films. Due to the high costs and technical requirements, most of them only provided slides and photographs, although the surviving film titles as well as the occasional use of the term “teacher film amateur” (Lehrerfilmamateur)34 indicate that the practice existed after all.

Overall, the Austrian Ministry of Education welcomed independent involvement (partly because it saved money) and issued appeals to teachers and popular educators to collaborate. They were called on to contribute in terms of content or didactics by providing new visual material or by supplementing existing films or slides with explanations befitting modern visual education. In particular, topics from local and natural history were recommended – with LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE the Schulkinobund was to become a “role model” in this respect. Some of its members were also among the first to establish slide and film distribution centres in Viennese schools. Engagement at the organisational level such as this was looked for, and teachers and popular educators were encouraged to found decentralised film and slide services (Bezirkslichtbildstellen) to provide regional schools and public education institutions with films and slides quickly and easily.35 At the same time, the Ministry of Education and the ÖLFD took measures to standardise and control educational film activities and had clear ideas about how regional visual media “libraries” should be founded and managed and how a decentralised system was to be established.36

Producing and Circulating Films about the Region

Both desired forms of engagement – film production as well as distribution – were pursued by the Styrian Schools Working Group for Educational Film on Local History (henceforth HKUF): not only did its member Viktor Zack produce about 30 educational films since 193337 and was probably one of the most productive “teacher film amateurs” in interwar Austria; the initiative also organised the circulation of these films as well as projectors throughout schools in the Southern Austrian province of Styria and provided accompanying material such as illustrative sketches. Officially founded in 1935, the HKUF already existed in a loose, smaller version before that; activities of its members, the majority of whom were Styrian teachers, can be traced back to 1933 at the latest. Starting from the small town Bruck an der Mur, about 200 schools had joined HKUF by May 1938, according to a report by founding member Hans Zach, in which he tried to “sell” the initiative to the new Nazi administration of recently annexed Austria. Most of these schools were primary and secondary schools, but one public education institution and a teacher training college also took part.38 For a charge of 50 groschen per 50 metres of film and an annual fee, members gained access to the films, contextual materials and projectors as well as advice and the opportunity to participate in trainings and the regional and annual conferences of HKUF. At a meeting in Graz in 1935, the initiative, which was financed mainly by voluntary donations in addition to the membership fees, formulated as its central task the “constant consultation of all schools, the creation of Heimatfilme that were ready for teaching and that combined the greatest objectivity and liveliness.”39

Film was appointed as the ideal teaching tool with reasons that show that the members knew the contemporary debates on educational film. However, unlike the Schulkinobund, the HKUF not only had rural schools specifically in mind, it also focused exclusively on the subject of Heimatkunde (local natural and regional history, economy, and geography): “Entrenching the pupils more deeply in their homeland” was seen as an important “task of today” and a “love of one’s homeland” a prerequisite for personality formation and a successful life.40 Zach penned these programmatic lines during the Austrofascist dictatorship, and as a recipient of the honorary title “government councillor” (Regierungsrat) he was probably rather closely connected to the regime. The terms of father- and especially homeland are omnipresent in the preserved records related to the HKUF, rendering the primacy of this notion obvious. There is no mention of the concept of state – homeland refers to Styria, not Austria, and a perspective focused on the nation as in the Burgenland film remains absent.

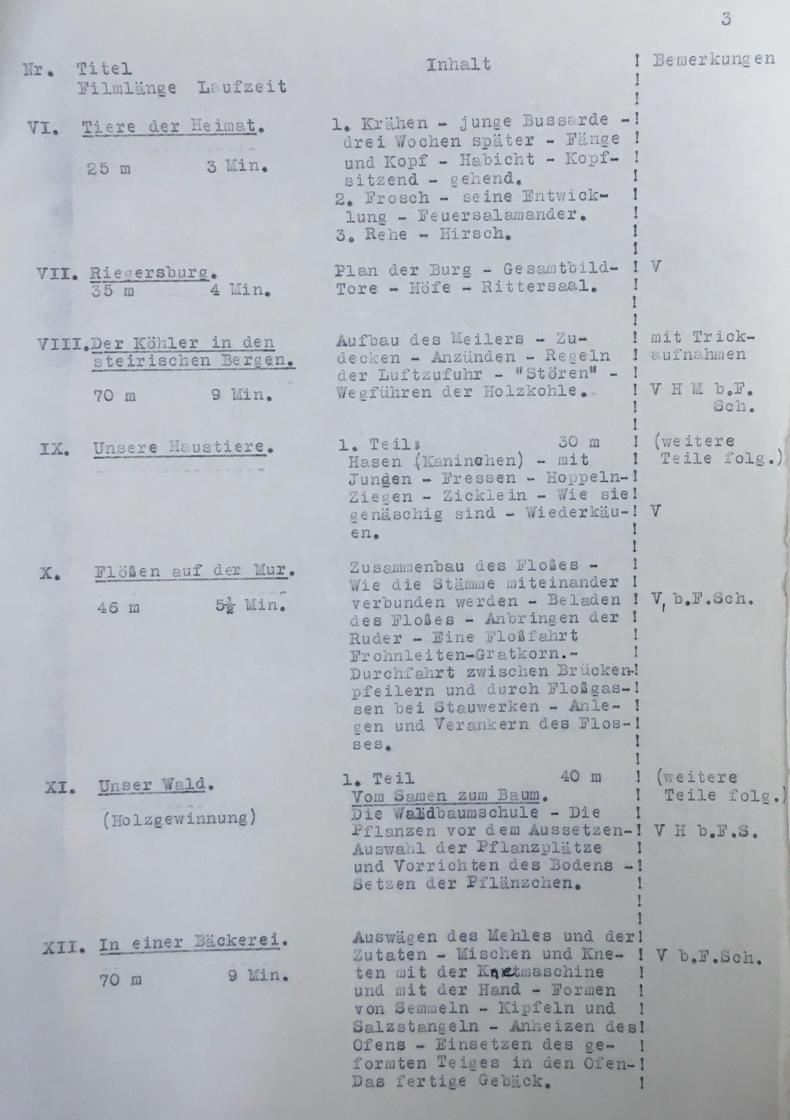

The films were to “grow out of the school itself and be created and designed for the school”41; short films on individual topics, produced by those who knew best – the teachers –, were considered particularly suitable. Zack shot on small-gauge film, interestingly at first on 9.5 millimetres, not on the recommended 16mm format that was to prevail.42 He filmed his surroundings, and thus, in contrast to LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE did not provide a view from “outside,” the urban centre’s perspective on rural life, but – at least spatially – an “inner perspective.” Short synopses on content and structure, length and area of use (various school types and age groups) have been preserved.43

Many films were about agricultural subjects like THE WORK OF STYRIAN MOUNTAIN FARMERS, which consisted of five parts – “Fertilising,” “Ploughing,” “Haymaking,” “Grain Harvest” and “People at the Plough” – that strongly resemble the Burgenland film. Several addressed regional economies or industries that had relevance for the whole of Austria (even if this was not stressed), such as STEIRISCHE ERZ UND EISEN / STYRIAN ORE AND IRON, which depicted the individual steps of ore mining in 26 minutes, among other things by means of animation. In four parts the film narrows down the subject matter: After introducing the location, the company and machines are depicted, followed by work processes and individual worksteps, the latter also via animation.44 Especially films like this one, which wanted to convey production methods and processes or geological developments like the formation of a stalactite, included animated sequences. This signifies that Zack was au courant with important and frequently used visualisation techniques in educational and industrial films.45 The Styrian Heimat was also featured via animals, the annual cycle, landscape, or landmarks. It was strongly associated with tradition, nature and pre-modern forms of production and work processes, but industries that were important nationwide as well, and was thus presented similar to the Austrofascist newsreels, the Wochenschau. The sources indicate that, similar to LIFE IN A BURGENLAND PEASANT VILLAGE, Zack’s films focused on positive aspects; in both cases, the goals – national sentiment, a love of the homeland and/or personality formation (Persönlichkeitsbildung) – were apparently to be achieved without any form of problematisation (e.g., of unemployment or conflicts).

Networks and Interests

Zack’s films also circulated outside of Styria in school contexts. Not only were they part of film programmes of smaller regional initiatives such as a working group of Viennese teachers,46 but they were also projected at small-gauge film screenings of the Schulkinobund aimed at teachers.47 In addition to these (more) informal networks, HKUF was supported by official regional bodies48 and in contact with representatives of the Ministry of Education, who were already aware of its activities in 1935 and showed interest in cooperation: Head of the ÖLFD, Johann Haustein, and Hans Mokré, head of the Styrian public education service, were sent to the founding conference in Bruck an der Mur as representatives of the Ministry of Education (Mokré also was to become a member of the initiative’s committee).49 In particular, the free use of projectors and Zack’s films lay in their interest; also a regional branch of the ÖLFD in Graz was planned that should be updated with slides and films from the HKUF’s production.50 However, contrary to Zach’s assertion in his report to the Nazi administration in 1938, the Styrians also benefited from exchanges with the state agencies, as the ÖLFD apparently provided Zack with footage for a film.51 So while Zach downplayed the cooperation for political reasons in 1938, the sources suggest that HKUF was quite well connected and cooperated not only with regional initiatives but also the centre. The latter’s attitude can be characterised as a well-meaning, somewhat superior view that approved of HKUF’s activities as an effort: Haustein, Mokré and Witt assessed Zack’s films overall as useful for schools and popular education or saw them as good “preparatory works” for a possible “more comprehensive local history” film that could be used for propaganda purposes.52

Scopes of Actions – Conflicts – Continuities

Gustav Adolf Witt, who ran the public education service (Volksbildungsstelle) in the Ministry of Education and from 1935 on also the ministry’s film commission, strove for a close link between ÖLFD and initiatives such as the HKUF, arguing that cooperation would avoid fragmentation as well as competition.53 Representatives of the centre expressed such concerns especially in the early years of institutionalisation, when expectations and guidelines were formulated and the scope for action was only just being defined. A case that seemed to confirm Witt’s fears was the regional Lichtbildleihe (Slide (and Film) Service) in a school in Leobersdorf in the province of Lower Austria: In the first issue of Das Bild in 1924, the brochure Das Lichtbild, der Lehrer und das Volk (The Slide, the Teacher and the People), written by the head of that service, teacher A. Schuhmann, was recommended as a “guide that has emerged from practical work and is valuable for all further organisation in the provinces.”54 A more detailed review was announced, but never appeared. This may have been because Schuhmann’s publication seemed to prove the dangers of activities not coordinated with the Ministry of Education that Witt would still invoke in the mid 1930s. In 1925, he dealt with Schuhmann’s divergent programme which proposed the establishment of local services “without official influence”: For Witt, actions like this one not only were often inefficient and amateurish and prevented the exchange of slides and films. Even more so, they “worked in an almost adversarial sense to the state’s efforts to provide slides and films (Lichtbildfürsorge).”55In his report he goes on:

As much as the teachers’ own activity (…) would be desirable, the Ministry of Education cannot in any way support such an idiosyncratic manner, as it is only likely to hinder, and even endanger, the unerring work of the Ministry of Education, which has so far been completely successful, and which is based on the uniform agreement of lending fee and substitution regulations on the part of all owners of slides.56

The ministry pursued rationalisation, efficiency, and standardisation. It claimed prerogative of interpretation and saw itself as “unerring” quality-assuring body regarding content, formats, and didactics, as well as the definition of guidelines for the distribution of slides and films. This was to ensure a nationwide, centrally organised exchange of visual teaching materials and networking of the individual regional services. Witt’s indignant reaction to Schuhmann’s perceived subversive activities testifies to the fact that individual initiatives were approved and supported only if they followed the given rules and/or were promising and benefited the centre, as was the case with the HKUF and the Schulkinobund.

Yet, the actors’ scope for action and success depended not only on their resources and their willingness to cooperate, but also on (political) networks: The Schulkinobund, which continued to exist after the elimination of parliament and democracy in Austria in 1933, but became less influential, was dissolved in 1939 by the NS administration.57 Karl Köfinger, who was a member of the initiative and as a cameraman played a leading role in the realisation of the group’s first educational film, LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE, was a successful producer of educational, advertising and cultural films under the dictatorial Dollfuß-Schuschnigg regime (1933–1938), several of them for the state-owned company Selenophon-Film, until his death in 1938. He also partly headed the Verband der Kurzfilmhersteller (Association of Short Film Producers), which obtained from the government that short film production become a protected “tied trade” and was also called upon several times during that period as a court expert on media-technical issues.58 Teacher film amateur Viktor Zack from HKUF, in turn, not only continued his activities after 1938 but moved “to the centre”: When the NS administration reorganised and centralised Austrian educational film activities, he became head of the Landesbildstelle “Alpen-Süd” in Graz in 1939, essentially being put in charge of the educational film agendas of the former Austrian provinces of Styria and Carinthia.59 As internal correspondence before his appointment states, NSDAP member Zack fulfilled the requirements “in pedagogical as well as in cinematic and organisational,” but also “in political terms.”60 From 1950 onwards he lead the now Austrian Styrian Landesbildstelle. An account of his goals and activities recalls the days of HKUF in the mid 30s: He wanted to anchor film and slides as teaching tools even in the most remote schools. The post-war cinematic staging of the Styrian homeland also bears witness to – political as well as (media-)educational – continuities: one of Zack’s new films was entitled STEIRISCHES HOLZ / STYRIAN WOOD.61

HKUF is an example of the smooth “transition” of cultural, educational initiatives from Austrofascism to National Socialism to the democratic state of Austria after 1945 – both in terms of protagonists such as Viktor Zack and in terms of the content conveyed: That the Austrian homeland, be it Styria, be it Burgenland, when interpreted as “Germanic” could easily be integrated into NS-German educational agendas is hardly surprising (after 1945, this aspect was consistently omitted). However, Heimatkunde as a school subject to generate love of one’s homeland and down-to-earthness in the sense of identification with one’s life world could (and can) be effective in various political contexts. It also played a major role in left-wing reform pedagogy, for example in Red Vienna. The central aim of Heimatkunde was to get to know and understand the close surroundings through one’s own senses, ideally through excursions or by means of images. The qualities of vividness and the immediate effect on emotion that were and are still attributed to film today made it the ideal medium in this respect, regardless of the (socio-)political agenda of the media educators. Due to the relative open-endedness of its presentational images – the shots of the unspecified farmworkers and the focus on the fertility of the fields instead of cultural heritage, the lack of explicitly political shots and titles –, LEBEN UND TREIBEN IN EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNDORFE could, depending on its contextualisation, be used to both strengthen identification with the democratic new state of Austria and as evidence of an alleged “Germanness” of the region (although these aspects did not necessarily contradict each other). Zack, too, was able to implement his programme, both in terms of content and pedagogy, in different political regimes. Central to all of them was the quality attributed to film of bringing the world to the classroom – be it to present the rural periphery in the urban centre of Vienna or to bring the nearer and wider surroundings into remote rural schools in the Austrian provinces.

The research in this article was funded in whole by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) P 32343-G (Educational Film Practice in Austria).

- 1H[einrich] F[uchsig], “Der erste von österreichischen Lehrern hergestellte Bildungsfilm,” Das Bild 2, no. 6 (1925): 94–95.

- 2Hans Zach, Aufruf an die Lehrerschaft, 1935. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G, 21027/38.

- 3For the broad discussion in Austria and Germany on film as a teaching aid at that time, see among others: Edgar Beyfuss and Alexander Kossowsky, eds., Das Kulturfilmbuch (Berlin: Chryselius & Schulz, 1924); Friedrich Copei, “Anschauung und Denken beim Unterrichtsfilm,” Film und Bild in Wissenschaft und Volksbildung 5, no. 8 (1939): 201–209; Film- und Bildseminar des Schulkinobundes, ed., Der Film als Lehrmittel (Vienna: Deutscher Verlag für Jugend und Volk, 1928) and various articles in the magazine Das Bild. For research on this see: Anita Gertiser, “Domestizierung des bewegten Bildes. Vom dokumentarischen Film zum Lehrmedium,” montage a/v 15, no. 1 (2006): 58–73; focusing on the – quite similar – discussions in the US: Devon Orgeron, Martha Orgeron, and Dan Streible, “A History of Learning with the Lights Off,” in Learning with the Lights Off. Educational Film in the United States, ed. Devon Orgeron, Martha Orgeron, and Dan Streible (New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), 16–66.

- 4Ferdinand Lettmayer, “Die Aufgaben des Geographieunterrichts und der Film,” in Der Film als Lehrmittel, 22–31.

- 5Sometimes titled DAS LEBEN UND TREIBEN AUF EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNHOF with a length of 1.200 m. Verzeichnis der Filme des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1931, K. 488, Sig. 2D2; or DAS LEBEN AUF EINEM BURGENLÄNDISCHEN BAUERNHOF (1600m). Lehr- und Kulturfilmarchiv Neuerscheinungen Erste Folge (Juni 1927), 4. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1929–1930, K. 487, Sig. 2D2.

- 6For this see the anthology by Marina Dahlquist and Joel Frykholm, eds., The Institutionalization of Educational Cinema. North America and Europe in the 1910s and 1920s (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019), especially the introduction, 1–16. For Austria, see: Katrin Pilz, “The Institutionalisation of Educational Film in Austria and Microcinematography as its exemplary ‘Good Object’, 1910–1938” (2023, unpub. manuscript).

- 7Michel de Certeau, The Practice of Everyday Life (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002), xv–xx.

- 8H[ans] E[rich] Schwarz, “Schulfilm: Das Leben in einem burgenländischen Bauerndorfe,” Bildwart 3, no. 10 (1925): 744, 746.

- 9Fuchsig, “Der erste von österreichischen Lehrern hergestellte Bildungsfilm.” But teacher Alto Arche, e.g., had already made several short films around 1910 that were shown in schools and popular educational institutions. Heinrich Fuchsig, Rund um den Film. Grundriss einer allgemeinen Filmkunde (Wien/Leipzig: Deutscher Verlag für Jugend und Volk, 1929), 123, 128.

- 10Gustav Adolf Witt, Lichtbild und Lehrfilm in Österreich (Vienna/Leipzig: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1927), 105. In the Viennese school reform of the 1920s, which was based on reform pedagogy, down-to-earthness (Bodenständigkeit) was one of the three main principles, along with comprehensive teaching and work school; down-to-earth meant vivid and related to the life world of the learners. Otto Glöckel, Die Entwicklung des Wiener Schulwesens seit dem Jahre 1919 (Vienna: Dt. Verlag für Jugend und Volk, 1927), 31. Many media educators, regardless of their political attitudes, supported reform pedagogy, e.g. Walther Günther, an important representative of educational film in Germany during both the Weimar Republic and the Nazi era.

- 11“Filmempfehlung,” Verordnungsblatt des Stadtschulrates für Wien 7 (April 1, 1926): 32.

- 12E.g., at the International Educational Film Conference in Basel 1927. N.N., “Umschau. Basler Lehrfilmkonferenz,” Das Bild 3, no. 6 (1927): 115.

- 13Fuchsig, “Der erste von österreichischen Lehrern hergestellte Bildungsfilm.”

- 14On the multifaceted, often contradictory process of the incorporation see: Béla Rasky, “Vom Schärfen der Unschärfe. Die Grenze zwischen Österreich und Ungarn 1918 bis 1924,” in … der Rest ist Österreich. Das Werden der Ersten Republik 1, ed. Helmuth Konrad and Wolfgang Maderthaner (Vienna: CSG, 2008), 139–158.

- 15Konsens und Konflikt. Schattendorf 1927 – Demokratie am Wendepunkt, red. Pia Byer and Evelyn Fertl (Eisenstadt: WAB, 2007). Focusing on the socio-political ramifications of the process: 80 Jahre Justizpalastbrand. Recht und gesellschaftliche Konflikte, ed. Austrian Ministry for Justice and Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for History and Society (Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 2008).

- 16Ferdinand Lettmayer, “Das Leben und Treiben in einem burgenländischen Bauerndorfe. Legende,” Das Bild 6, no. 2 (1929): 33.

- 17The actual archival print corresponds to the structure that Lettmayer indicated in 1929. Lettmayer, “Leben und Treiben.” An earlier account presents a different order. Fuchsig, “Der erste von österreichischen Lehrern hergestellte Bildungsfilm.”

- 18Lettmayer, “Leben und Treiben.”

- 19Roman Sandgruber, “Die österreichische Ernährungssituation und die burgenländische Landwirtschaft,” in Burgenland 1921. Anfänge, Übergänge, Aufbau (Eisenstadt 1996), red. Roland Widder, 191–198.

- 20Walter Dujmovits, Die Amerikawanderung der Burgenländer (Berlin: Epubli, 2012), 11. Philipp Strobl, “The Origins of ‘Little Burgenland’: A Close Look at Austria’s Most Important Area of Emigration, 1900–1930,” in Quiet Invaders Revisited. Biographies of Twentieth Century Immigrants to the United States, ed. Günther Bischof (Innsbruck/Wien/Bozen: Studienverlag, 2017), 79–100.

- 21E.g. Paul Kisch, “Fortschritte im Burgenland,” Neue Freie Presse, April 10, 1929, 2–3; N.N., “Das Meer der Wiener. Ein Ausflug nach Hinterösterreich,” Die Bühne 4, no. 138 (1927): 14–15. See also: Ferenc Jankó and Steven Jobbitt, “Making Burgenland from Western Hungary: Geography and the politics of Identity in Interwar Austria,” Hungarian Cultural Studies. e-Journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association 10 (2017), DOI: 10.5195/ahea.2017.313.

- 22K[onrad K[noll], “Wiener Lehrer mit der Filmkamera im Burgenland. Unsere ersten Filmaufnahmen,” Das Bild 1, no. 1 (1924): 4–5.

- 23In his article on the region-building process in Burgenland Peter Haslinger speaks of an ambiguity of local identities. Peter Haslinger, “Building a Regional Identity. The Burgenland, 1921–1938,” Austrian History Yearbook 32 (2001): 105–123, DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0067237800011188; see also: Jankó and Jobbitt, “Making Burgenland from Western Hungary.”

- 24Gert Tschögel, “Was bleibt, sind Erinnerungen. Zur Geschichte der burgenländisch-jüdischen Kultur,” in Grenzfall Burgenland 1921–1991, ed. Elisabeth Deinhofer and Traude Horvath (Eisenstadt: Kanica, 1991), 115–126.

- 25Lettmayer, “Leben und Treiben.”

- 26N.N., “Methodische Richtlinien. ‘Bäuerliches Leben in Österreich,’” Das Bild 2, no. 5 (1925): 80.

- 27Verzeichnis der Filme des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania, OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1931, K. 488, Sig. 2D2.

- 28Lettmayer, “Aufgaben des Geographieunterrichts und der Film,” 23–24.

- 29Ibid.

- 30E.g., in 1933/34 “Burgenland; the most beautiful castles in Burgenland – Life in a Burgenland Peasant Village (films); speech and singing rehearsals of the regional dialect.”

- 31Most important were the associations Kosmos (with the Kosmos school cinema) and Kastalia (that also published the media educational journal Kastalia. Österreichische Zeitschrift für wissenschaftliche und Schulkinematographie).

- 32Its aim was to exchange experiences between Austrian and German educational film and cinema reform movements. For the talks see the special issue “Die Kinoreform-Tagung in Wien” of Volksbildung 5, no. 4–5 (1925). See also Vrääth Öhner’s article in this issue.

- 33Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania, no. 37 (1921): 7. Christian Stifter, “Die Erziehung des Kinos und die ‘Mission des ‘Kulturfilms.’’ Zur sozialen Organisation des ‘Guten Geschmacks’ in der frühen Volksbildung und Kinoreform in Wien, 1898–1930,” Spurensuche 8, no. 3–4 (1997): 54–79; Marie-Noëlle Yazdanpanah, “Through Ice and Snow. Mountain Films as Educational Films in the 1920s and 1930s,” TMG Journal for Media History 26, no. 1 (1923, https://tmgonline.nl/).

- 34Gustav Adolf Witt, Fortschritte Österreichs im Lichtbild- und Lehrfilmwesen (Vienna/Leipzig: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1931), 114.

- 35Referentenerinnerung. Mitarbeit der Lehrerschaft an der Lichtbildleihe des BMU. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Lichtbildwesen 1920–1925, K. 503, Sig. 2D2, 11305, III-13/25.

- 36See: G.A. Witt’s Letter to the regional School Board, June 30, 1925. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Lichtbildwesen 1920–1925, K. 503, Sig. 2D2, 15587, III13/25.

- 37Gerald Matzner, “Direktor Viktor Zack zum Gedenken,” Sehen und Hören 4, no. 59 (1972): 165.

- 38See: Hans Zach’s Report for the Styrian Regional School Board, May 24, 1938. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G, 21027/38.

- 39Zach, Aufruf an die Lehrerschaft.

- 40Lecture Hans Zach, Heimatkundlicher Unterricht und Unterrichtsfilm. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G, 21027/38.

- 41Zach, Report for the Styrian Regional School Board.

- 42Schmalfilmtagung 1934 Wiener Neustadt. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1934, K. 492, Sig. 2D2, 36559.

- 43Film Directories of the “Steirische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für den heimatkundlichen Unterrichtsfilm,” January 1938. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G. I have not found any surviving copies so far.

- 44Ibid.

- 45Animation was used to achieve “precision in detail” and bring “a thought to an exact point” which could not be achieved so well with photographic images. Ramón Reichert, “Behaviorism, Animation, and Effective Cinema. The McGraw-Hill Industrial Management Film Series and the Visual Culture of Management: Films that Work,” in Films that Work. Industrial Film and the Productivity of Media, ed. Vinzenz Hediger and Patrick Vonderau (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009), 292.

- 46Bericht über die Versuchsarbeit mit Unterrichtsfilmen in Wien, 18. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10 G, 1590/1938.

- 47N.N., “Der Schmalfilm als Unterrichtsfilm,” Die österreichische Schule 14, no. 4 (1937): 314.

- 48For example, the Styrian school board called for joining HKUF in official media and exempted teachers who attended their conferences from teaching. Verordnungsblatt für das Schulwesen in der Steiermark, February 15, 1935, 21–22; N.N., “Mitteilungen,” Pädagogische Zeitschrift, no. 1 (1938): s.p

- 49N.N., “Schmalfilm-Tagung in Bruck a. d. Mur,” Die österreichische Schule 12, no. 3 (1935): 2.

- 50Hans Mokré, Bst.V.B.R.f.Stmk. Schaffung einer Zweigstelle des ÖLFD in Graz, April 6, 1935. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1935, K. 493, Sig. 2D2, 7916- VB/35.

- 51G.A. Witt, Comment to Mokrés report about the 1935 conference in Bruck. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1935, K. 493, Sig. 2D2, 7914/VB/35. This is also an indication of the practice of integrating footage into educational films or combining sequences from several films.

- 52E.g., Hans Mokré in his report for the BMU about the 1935 conference in Bruck, March 5, 1935. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1935, K. 493, Sig. 2D2, 178/3-1935.

- 53Witt, Comment to Mokrés Report.

- 54N.N., “Bücher und Zeitschriftenschau,” Das Bild 1, no. 1 (1924): 6.

- 55G.A. Witt, Letter to the Regional School Board of Lower Austria, June 30, 1925. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Lichtbildwesen 1920–1925, K. 503, Sig. 2D2, 15587, III-13/25.

- 56Ibid.

- 57OeStA, AdR, BKA, BKA-I, BP-Direktion, VB, Sig.-XIV, 1070 Österreichischer Schulkinobund, 1929–1939, GZ 5064/39.

- 58N.N., “Konflikt in der Wiener Kurzfilm-Produktion,” Der Wiener Film, December 15, 1936, 2; “Personalnachrichten,” Reichspost, February 7, 1931, 4.

- 59Four new film services were set up in Austria. They were subordinated to the RfdU, the Reichsstelle für den Unterrichtsfilm (Reich Office for Teaching Films) a branch of the Ministry of Science, Education and Culture.

- 60Odomar Gugenberger in a letter to the Ministry of Internal and Cultural Affairs, January 27, 1939. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G, 306758.

- 61Matzner, “Direktor Viktor Zack zum Gedenken.”

Austrian Ministry for Justice and Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for History, and Society, eds. 80 Jahre Justizpalastbrand. Recht und gesellschaftliche Konflikte. Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 2008.

Bericht über die Versuchsarbeit mit Unterrichtsfilmen in Wien, 18. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10 G, 1590/1938.

Beyfuss, Edgar, and Alexander Kossowsky, eds. Das Kulturfilmbuch. Berlin: Chryselius & Schulz, 1924.

Byer, Pia, and Evelyn Fertl, red. Konsens und Konflikt. Schattendorf 1927 – Demokratie am Wendepunkt. Eisenstadt: WAB, 2007.

Copei, Friedrich. “Anschauung und Denken beim Unterrichtsfilm.” Film und Bild in Wissenschaft und Volksbildung 5, no. 8 (1939): 201–209.

Dahlquist, Marina, and Joel Frykholm, eds. The Institutionalization of Educational Cinema. North America and Europe in the 1910s and 1920s. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2019.

de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002, xv–xx.

“Die Kinoreform-Tagung in Wien.” Special issue of Volksbildung 5, no. 4–5 (1925).

Dujmovits, Walter. Die Amerikawanderung der Burgenländer. Berlin: Epubli, 2012.

Film Directories of the “Steirische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für den heimatkundlichen Unterrichtsfilm,” January 1938. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G.

“Filmempfehlung.”Verordnungsblatt des Stadtschulrates für Wien 7 (April 1, 1926): 32.

Film- und Bildseminar des Schulkinobundes, ed. Der Film als Lehrmittel. Vienna: Deutscher Verlag für Jugend und Volk, 1928.

F[uchsig], H[einrich]. “Der erste von österreichischen Lehrern hergestellte Bildungsfilm.” Das Bild 2, no. 6 (1925): 94–95.

Fuchsig, Heinrich. Rund um den Film. Grundriss einer allgemeinen Filmkunde. Vienna/Leipzig: Deutscher Verlag für Jugend und Volk, 1929.

Gertiser, Anita. “Domestizierung des bewegten Bildes. Vom dokumentarischen Film zum Lehrmedium.” montage a/v 15, no. 1 (2006): 58–73.

Glöckel, Otto. Die Entwicklung des Wiener Schulwesens seit dem Jahre 1919. Vienna: Dt. Verlag für Jugend und Volk, 1927.

Gugenberger, Odomar. Letter to the Ministry of Internal and Cultural Affairs, January 27, 1939. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G, 306758.

Haslinger, Peter. “Building a Regional Identity. The Burgenland, 1921–1938.” Austrian History Yearbook 32 (2001): 105–123. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0067237800011188.

Jankó, Ferenc, and Steven Jobbitt. “Making Burgenland from Western Hungary: Geography and the politics of Identity in Interwar Austria.” Hungarian Cultural Studies. e-Journal of the American Hungarian Educators Association 10 (2017). DOI: 10.5195/ahea.2017.313.

Kisch, Paul. “Fortschritte im Burgenland.” Neue Freie Presse, April 10, 1929, 2–3.

K[noll], K[onrad]. “Wiener Lehrer mit der Filmkamera im Burgenland. Unsere ersten Filmaufnahmen.” Das Bild 1, no. 1 (1924): 4–5.

Lehr- und Kulturfilmarchiv Neuerscheinungen Erste Folge (Juni 1927), 4. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1929–1930, K. 487, Sig. 2D2.

Lettmayer, Ferdinand.“ Die Aufgaben des Geographieunterrichts und der Film.” In Der Film als Lehrmittel, 22–31.

Lettmayer, Ferdinand. “Das Leben und Treiben in einem burgenländischen Bauerndorfe. Legende.” Das Bild 6, no. 2 (1929): 33.

Matzner, Gerald. “Direktor Viktor Zack zum Gedenken.” Sehen und Hören 4, no. 59 (1972): 165.

Mokré, Hans. Bst.V.B.R.f.Stmk. Schaffung einer Zweigstelle des ÖLFD in Graz, April 6, 1935. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1935, K. 493, Sig. 2D2, 7916- VB/35.

Mokré, Hans. Report for the BMU about the 1935 conference in Bruck, March 5, 1935. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1935, K. 493, Sig. 2D2, 178/3- 1935.

N.N. “Bücher und Zeitschriftenschau.” Das Bild 1, no. 1 (1924): 6.

N.N. “Methodische Richtlinien. ‘Bäuerliches Leben in Österreich’.” Das Bild 2, no. 5 (1925): 80

N.N. “Das Meer der Wiener. Ein Ausflug nach Hinterösterreich.” Die Bühne 4, no. 138 (1927): 14–15.

N.N. “Umschau. Basler Lehrfilmkonferenz.” Das Bild 3, no. 6 (1927): 115.

N.N. “Schmalfilm-Tagung in Bruck a. d. Mur.” Die österreichische Schule 12, no. 3 (1935): 2.

N.N., “Konflikt in der Wiener Kurzfilm-Produktion,” Der Wiener Film, December 15, 1936, 2.

N.N. “Der Schmalfilm als Unterrichtsfilm.” Die österreichische Schule 14, no. 4 (1937): 314.

N.N. “Mitteilungen.” Pädagogische Zeitschrift, no. 1 (1938): s.p

Öhner, Vrääth. “In Defense of Culture. The Vienna Urania and the Cultural Film.” Research in Film and History 5 (2023): 1–30.

Orgeron, Devon, Martha Orgeron, and Dan Streible. “A History of Learning with the Lights Off.” In Learning with the Lights Off. Educational Film in the United States, eds. Devon Orgeron, Martha Orgeron, and Dan Streible, 16–66. New York: Oxford University Press, 2012.

“Österreichischer Schulkinobund.” OeStA, AdR, BKA, BKA-I, BP-Direktion, VB, Sig.-XIV, 1070 Österreichischer Schulkinobund, 1929–1939, GZ 5064/39.

“Personalnachrichten.” Reichspost, February 7, 1931, 4.

Pilz, Katrin. “The Institutionalisation of Educational Film in Austria and Microcinematography as its exemplary ‘Good Object’, 1910–1938” (2023, unpub. manuscript).

Rasky, Béla. “Vom Schärfen der Unschärfe. Die Grenze zwischen Österreich und Ungarn 1918 bis 1924.” In … der Rest ist Österreich. Das Werden der Ersten Republik 1, edited by Helmuth Konrad and Wolfgang Maderthaner, 139–158. Vienna: CSG, 2008.

Referentenerinnerung. Mitarbeit der Lehrerschaft an der Lichtbildleihe des BMU. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Lichtbildwesen 1920–1925, K. 503, Sig. 2D2, 11305, III-13/25.

Reichert, Ramón. “Behaviorism, Animation, and Effective Cinema. The McGraw-Hill Industrial Management Film Series and the Visual Culture of Management: Films that Work.” In Films that Work. Industrial Film and the Productivity of Media, edited by Vinzenz Hediger and Patrick Vonderau. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009.

Sandgruber, Roman. “Die österreichische Ernährungssituation und die burgenländische Landwirtschaft.” In Burgenland 1921. Anfänge, Übergänge, Aufbau, red. Roland Widder, 191–198. Eisenstadt 1996.

Schmalfilmtagung 1934 Wiener Neustadt. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1934, K. 492, Sig. 2D2, 36559.

Schwarz, H[ans] E[rich]. “Schulfilm: Das Leben in einem burgenländischen Bauerndorfe.” Bildwart 3, no. 10 (1925): 744, 746.

Stifter, Christian. “Die Erziehung des Kinos und die ‘Mission des ‘Kulturfilms.’’ Zur sozialen Organisation des ‘Guten Geschmacks’ in der frühen Volksbildung und Kinoreform in Wien, 1898–1930.” Spurensuche 8, no. 3–4 (1997): 54–79.

Strobl, Philipp. “The Origins of ‘Little Burgenland’: A Close Look at Austria’s Most Important Area of Emigration, 1900–1930.” In Quiet Invaders Revisited. Biographies of Twentieth Century Immigrants to the United States, edited by Günther Bischof, 79–100. Innsbruck/Vienna/Bozen: Studienverlag, 2017.

Tschögel, Gert. “Was bleibt, sind Erinnerungen. Zur Geschichte der burgenländischjüdischen Kultur.” In Grenzfall Burgenland 1921–1991, edited by Elisabeth Deinhofer and Traude Horvath, 115–126. Eisenstadt: Kanica, 1991.

Verlautbarungen des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania, no. 37 (1921): 7.

Verzeichnis der Filme des Volksbildungshauses Wiener Urania. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1931, K. 488, Sig. 2D2.

Verordnungsblatt für das Schulwesen in der Steiermark, February 15, 1935, 21–22.

Witt, Gustav Adolf. Letter to the Regional School Board of Lower Austria, June 30, 1925. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Lichtbildwesen 1920–1925, K. 503, Sig. 2D2, 15587, III-13/25.

Witt, Gustav Adolf. Lichtbild und Lehrfilm in Österreich. Vienna/Leipzig: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1927.

Witt, Gustav Adolf. Comment to Mokrés report about the 1935 conference in Bruck. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Volksbildung Film 1935, K. 493, Sig. 2D2, 7914/VB/35.

Witt, Gustav Adolf. Fortschritte Österreichs im Lichtbild- und Lehrfilmwesen. Vienna/Leipzig: Österreichischer Bundesverlag, 1931.

Yazdanpanah, Marie-Noëlle. “Through Ice and Snow. Mountain Films as Educational Films in the 1920s and 1930s.” TMG Journal for Media History 26, no. 1 (1923). https://tmgonline.nl/.

Zach, Hans. Aufruf an die Lehrerschaft, 1935. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G, 21027/38.

Zach, Hans. Report for the Styrian Regional School Board, May 24, 1938. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G, 21027/38.

Zach, Hans. Heimatkundlicher Unterricht und Unterrichtsfilm. OeStA, AVA, UM Unterricht allgem., Film 1932–1940, K. 1894, Sig. 10G, 21027/38.