The Development of Educational Cinema for Schools in the Soviet Union in the 1930s

From the Cinefication of Schools to the Film Lesson

Table of Contents

Screening Propaganda

In Defense of Culture

The Raw Materials of Celluloid Film

Wholeness and Nature

The Austrian Province as Subject and Space of Action in Educational Film Practices

The Development of Educational Cinema for Schools in the Soviet Union in the 1930s

Educational Film in East Germany (GDR) in 1950–1990 in Perspective of the “Grammar of Schooling”

No Instructions, Just Some Advice

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Serov, Lena. “The Development of Educational Cinema for Schools in the Soviet Union in the 1930s: From the Cinefication of Schools to the Film Lesson.” Research in Film and History 5 (2023): 1–48. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/22731.

Introduction

The 1920s were decisive in defining the direction and imagination of Soviet cinema as being endowed with educational value rather than exploiting its appeal as commercial entertainment. Lenin’s remarks on cinema are often quoted, particularly in Soviet historical sources, as being crucial in defining cinema not only as “the most important of all arts,” but also as a useful asset in enlightening the broad masses. Acknowledging cinema’s educational capacities, Lenin advocated for film programs to be screened in “a definite proportion between entertainment films and scientific ones,”1 dubbed later as the ‘Lenin proportion’ (Leninskaia proportsiia).2 Denise Youngblood has shown how cinema in the 1920s was under dispute between the artistic and political public agents for its leading role as entertainment or enlightenment. Although nationalized in 1919 and under formal control of the Narkompros (the People’s Commissariat of Education),3 cinema became a commercial commodity during the New Economic Policy (1921–1928), a period of mixed economy that produced significant revenue from foreign and domestic entertainment films popular among the Soviet spectatorship. Disregarding the popular tastes of the predominantly urban, middle-class audience, the enlighteners could finally push back the pro-entertainment stance of the film industry with vocal ideological polemics, the demand for censorship and an expansion of state control over production and distribution. With the advent of the Stalinist Cultural Revolution in the late 1920s, cinema was effectively reformed according to ‘utilitarian aesthetics’ with the industry focusing on quality cinema ‘for the millions’ as film import was curtailed and cinema administration further centralized.4

It is against this backdrop that educational cinema begins to develop in the Soviet Union which constitutes the topic of this paper and has not yet been subject of extensive study.5 It covers the period between the end of the 1920s and the first half of the 1930s when educational film developed as a concept and a production type. This period was also characterized by the effort to turn educational cinema into a prolific practice based on coordinated organization implicating the ‘cinefication of schools’ (kinofikatsiia shkoly) and a systematic production of film for schools in order to provide schools with screening opportunities and a repertoire conceived useful for education. Although instances of introducing films to school children were undertaken even before the revolution in Tsarist Russia,6 I will argue that educational film only became ‘institutionalized’ in the 1930s as a film type and a coordinated activity that encompassed a circuit for film production, distribution and exhibition, a body of pedagogical and methodological knowledge and the establishment of a set of practices that allowed for what we can call the ‘Soviet film education movement.’7 Therefore, I also look into the conditions of deploying cinema in schools as a new nontheatrical network for distribution and exhibition that was practically created from scratch, and into the very specific ways of applying cinema to the sites of education. To reconstruct this material framework and the activities of educational cinema, I follow the pragmatic perspective proposed by Eef Masson in her analysis of Dutch classroom films. In the Soviet Union the idea of educational cinema was also bound “to a very specific screening location, a set of institutionalized practices, and/or a given audience.”8

Moreover, the deployment of cinema in schools meant the adaptation to a new audience of children and youth and their particular psychological demands as well as to the pedagogical requirements of education. This process involved many scientific specialists from the disciplines of psychology, pedagogy and ‘pedology’ (‘study of the child’), a new home-grown interdisciplinary field that studied “the child’s social environment and its relation to learning capacity, behavior and ideology.”9 These specialists, active in different scientific centers, were devoted to the study of the impact of cinema on children in general and, as a result, the advancement of cinema for edifying and educational purposes the major endeavor of which became the introduction of cinema to schools. As these research centers maintained close cooperation with film studios and filmmaking professionals, their research and expertise on the effective use of film for pedagogical purposes were integrated into the production of educational films. Effectively, the educational cinema movement in the Soviet Union can be seen as a collective effort between researchers, educators and filmmakers that can be traced throughout the debates that were conducted in numerous publications and in several periodicals of educational as well as cinematographic fields.

The idea to apply cinema in compulsory education was reflected in the introduction of the term uchebnoe kino (educational cinema).10 Alternatively, the term ‘school film’ (shkol’nyi fil’m) was in wide use, to emphasize the institutional purpose. Both notions included a variety of film types (including feature films, kul’turfil’ms or scientific films) that could be used or adapted for screenings within an educational framework or as an activity conducted by the school, be it an out-of-school event in a nearby movie theater or a classroom lesson.11 Often educational film (uchebnyi fil’m) also served as an umbrella term for films conveying knowledge of different kinds and was used to include technical or instruction films that were used for worker training in factories and other sites of instruction.12 However, the term uchebnyi soon became a denominator for a new film type envisaged specifically for schools. Sometimes it was specified additionally by the notion ‘school education films’ (shkol’no-uchebnyi fil’m) to stress the distinction from cinematic instruction.13 With gradual assertion of the advancement of films for school use, educational film became synonymous with the notion of kinoposobie (‘film textbook’) and the idea of film as a teaching aid. Educational films, the formal and textual features of which were to be adapted to the school curriculum, pedagogical requirements and the formality of the school lesson, were effectively assigned a specific place, role and function in class. This notion became crucial because it helped formulate demands to the film industry to produce films suitable for integration into school lessons.

The developments in the Soviet Union should be regarded in a wider context of the institutionalization and internationalization of educational cinema that began earlier in North America and Europe. At least in the early phase of advocating for educational cinema, Soviet specialists were aware of the developments in the West. This is documented by the reporting on the advancements in the field of educational cinema in several publications. Lazar’ Sukharebskii, who was a central figure for the medical, hygiene and scientific film in Soviet cinema of the 1920s, particularly points to the progress made in Germany, Belgium and the US in the field of educational cinema.14 Soviet authors, however, made sure to stress the exceptionality of the Soviet case due to its progressive ideology and cautioned not to adopt all Western methods.15

1. Research into Cinema and Children

Children’s passion for cinema can and should be exploited in every possible way at school.16

Scientific efforts to research the effects of cinema on Soviet audiences constituted an important step towards the Soviet mass enlightenment project through cinema, and effectively educational cinema. The 1920s saw a boom in this kind of audience research: scientists and film workers alike were eager to know their audiences and measure their tastes and reactions to films to produce data that would help to make films that satisfied the viewer and the box office. This “fixation on the ‘sphere of reception’ (vosprinimaiushchaia sreda)” mobilized a variety of research cells guided by the wish to tap the desires of the audience.17 The scientists’ attention focused on one audience group in particular that was deemed particularly attracted to cinema and at the same time perceived as exceedingly vulnerable to its suggestive effects: children and youth.18 Establishing that children devoted most of their leisure time to cinema, the scientists, furthermore, determined that cinema posed a threat to the mental and physical health of children causing distress and fostering the emulation of bad behaviors. The demoralizing impact on young cinema-goers was related to the exposure to a film repertoire which predominantly consisted of imported films from the USA and Europe and Soviet versions of foreign commercial genre cinema.19 In the eyes of the (politically conscious) educators, these films represented the evils of capitalism with their depiction of violence, sex and crime and were regarded as a source for deviance and criminality among youngsters. Soviet observers were sure to ascribe the negative effects to foreign productions, yet remained convinced of the general edifying force of cinema as Anna Toropova has established: “For all their vocal warnings about the damage to children’s physical, mental and moral wellbeing effectuated by unbridled exposure to unsuitable films, Soviet educators and pedologists never questioned that the cinematic medium held unrivalled capacities to healthify the body politic.”20 Testifying to their fervent and polemical nature, the debates were charged with medical vocabulary: educators advocated for the ‘healthification’ of film-viewing activities and an age-appropriate repertoire as ‘antidote’ for the perils of commercial cinema to the wellbeing of children, while the popularity of film viewing among children and youth was pathologized as ‘film mania.’21

As a consequence, educators and pedologists called out for a variety of ‘healthifying’ measures to transform film industry practices and the repertoire of available films – demands resonating with the calls for transformation of the ‘Soviet Man’ according to revolutionary principles.22 Similar to developments in the West like the studies under the supervision by the Payne Fund and their accompanying public debates,23 Soviet cinema reformers called for restrictive means to control access to dangerous film content conceived as harmful through censorship regulating the admission to screening and also intervened into the repertoire by censoring depictions of sexuality, criminality and violence. Another path for educators consisted in the pedagogization of cinema and the creation of a child-friendly cinema environment. The pedagogization of cinema meant that the movie theater turned into an educational setting for children even apart from contexts of formal education: at the end of the 1920s special theaters for children opened in Moscow and Leningrad. During organized matinée screenings young viewers were able to cultivate correct behavioral and viewing habits under pedagogical guidance. Apart from behavioral rules and the educators’ opportunities to monitor the children’s conduct, this encompassed film introductions and discussions that facilitated an active mode of spectatorship and fostered aesthetic sensibilities towards the medium film.24 To neutralize the psycho-physiological impact of cinema, certain hygienic precautions were undertaken to prevent from visual overstimulation in order to minimize fatigue and irritation of sight and perception. Altogether, these undertakings were “part of a broader drive to co-opt the cinema for the purposes of education.”25 Yet, the principal direction of pedagogical cinema, as I would like to argue in this paper, was the ‘cinefication’ of Soviet schools. The attempts to deploy cinema in schools and the classroom mobilized not only educators and pedagogues, but also administrative and public institutions of education, above all the Narkompros as the main entity and other subsidiaries under its formal supervision. This spurred the creation of a new film branch and the production of knowledge on film construction and film use through experimental research that served as basis for the complex process of the implementation of cinema in Soviet schools.

2. The ‘Cinefication’ of Schools

The 1928 Party meeting on cinema emphasized the urgency of creating school films as a most valuable teaching aid.26

The harnessing of cinema for educational purposes was not only advocated for by scientists and educators. The state, identifying this as within its interests, gave decisive pushes to the ‘cinefication’ of schools, i.e. the creation of an infrastructure of distribution and exhibition for the broad adoption of films in educational institutions. The state’s intervention can be identified on two levels. First, there was the idea to transform the film industry to serve the state’s ideas of the cultural revolution. Second, the state made attempts, in the first two decades of its existence, to expand education and reform the Soviet schools when after a period of pedagogical experimentation schools were supposed to return to a solid curriculum where film would take a place along with other teaching aids to make school work more effective.

For the transformation of the film industry for state-oriented tasks, the decisive event was the All-Union Party Conference on Cinema Affairs in 1928 that criticized the commercial orientation of film organizations, most notably the state film company Sovkino. Sovkino’s distribution circuit and repertoire was accused of serving the urban bourgeois audience rather than the broad public, particularly in the countryside. The party conference demanded the reorganization of the film industry to produce an ideological cinema in the interests of the proletariat as the vanguard of socialist construction and cinema forms that were accessible to millions. Turning cinema into a mass art in the hands of the proletariat and creating a cinema to elevate the cultural level of the broad masses was to be achieved by expanding the nontheatrical cinema network with a focus on agitational art. One of the proclaimed results of the conference was that cinema was to take a particular place in the education of children and youth. Taking the child-viewer into account, plans were made to “immediately begin to create educational films, linking them to the curriculum of our schools” and to realize “the task of accelerated development of cinema facilities in the city and village, particularly in schools and children’s clubs.”27

The deployment of film in schools also features in the resolutions on elementary and middle schools issued by the Party in 1931 and 1932.28 With the establishment of compulsory education for all children and the expansion of the school network, the Soviet state introduced a new school system with a strong emphasis on productive labor education. This was also reflected in the introduction of the polytechnical principle of education as a basis for the organization of school work. “In the simplest terms, the polytechnical school was one which taught a variety of practical skills – the antithesis of the ‘academic’ school exemplified by the Tsarist gymnasium.”29 The first resolution called for a reform of pedagogical methods and teaching practices criticizing Soviet schools for failing to “give a sufficient amount of general knowledge,” especially in the “foundations of the sciences (physics, chemistry, mathematics, native language, geography etc.)” for entrance to technicums and higher schools.30 Thus, it called for a stronger link of practical work with the acquisition of a foundation of theoretical knowledge that should be reflected in the introduction of teaching by subject.31 The polytechnical method also envisaged, apart from the installment of workshops in schools for mastering of technology and industrial labor, to establish new sites of learning like libraries, museums, and cinemas that should contribute to the practicality of education and to the pupils’ autonomy in learning.32 The 1932 resolution, as an addition, again drew attention to cinema as one of the ‘tools of pedagogical work’ along with maps, radio and other teaching aids in the context of outlining the basic curriculum, the school methodology and the role of the teacher. The document formulated demands to provide systematic learning on the basis of clearly delineated school subjects, including reading, writing and arithmetic, and solid curriculums in order to organize school work and increase pedagogical effectiveness.

Although individual efforts to deploy cinema for school education began at the end of the 1920s, both resolutions along with the reformation of the Soviet school gave a signal to enforce the organization of the ‘cinefication of school’ campaign that already figured as a title of a 1930 publication by Lazar’ Sukharebskii and Aleksandr Shirvindt outlining its conditions and directions.33 The effort to expand the network of schools participating in the campaign of bringing films into the classroom contained two components that implied the technical and organizational tasks on the one hand, and the production and provision of films on the other. The cinefication of the schools coincided with the general expansion of cinema outlets already underway since the mid-1920s which strove for a broad reach of the population by means of cinema, building a nontheatrical circuit and particularly targeting the countryside for new viewing facilities.34 As Jamie Miller has shown in his review of the development of the film industry’s technical base throughout the 1930s, the high aspirations of the cinema administration for a large and productive cinema infrastructure could hardly be met within the envisioned plans. The technical advancement of the film industry evolved very slowly, as the Soviet Union only began to build its technical base producing their own technical equipment and raw film in the 1930s formerly relying on foreign imports while at the same time introducing new sound technology into film production and distribution.35 As with the general cinefication plans for the country, cinefying schools proved difficult to realize on the ground for similar reasons: deficiencies in planning and organization of the technical base.

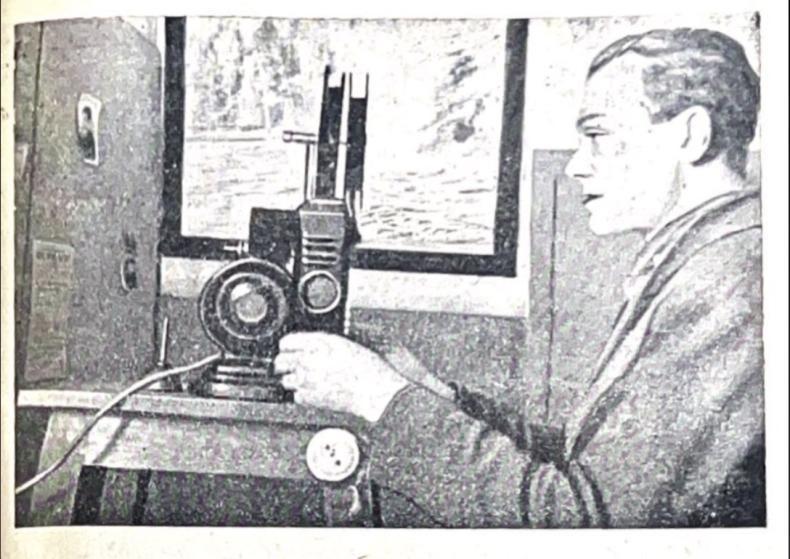

Generally, the cinefication effort envisaged three ways of bringing films to schools: through stationary (statsionarno) external screening venues, mobile cinema (peredvizhka) or permanent installations of screens and projectors in schools.36 The stationary form foresaw external institutions, like the regional departments for the people’s education (the so-called ONOs – otdely narodnogo obrazovaniia), to organize a venue at a local movie theater or club and to rent films for film-lectures, preferably matching the curriculum and designated for groups of pupils from several schools. The makeshift installations, in contrast, could serve schools individually, on a circuit itinerary for a series of schools, or as one school hosting a cluster of classes from different schools for a collective film screening while sharing the expenses for the projectionist [kinomekhanik] and film rental. The principal effort, however not attainable for all educational facilities due to financial reasons, should be directed to equipping schools with permanent screening opportunities, which included a projector and screen that either could be installed in a central location in school like a hall or a cabinet used by all classes, or as a mobile device moving in-between classes.37 While the collective screenings and the mobile cinema circuit were the predominant types of film service for school children, especially in regional and remote areas, a permanently installed projector became more common in the urban centers like Moscow and Leningrad.

During the First Five-Year Plan (1928–1932), the cinefication campaign envisaged to equip 3025 educational facilities with permanent film devices, and a total number of about 20.000 film installments (kinoustanovki) in the RSFSR were supposed to be established by the end of 1932.38 Kinoustanovki were not only to include cinefied schools, but also mobile cinema stations that provided screening services for schools and screening halls at other cultural facilities that qualified as nontheatrical screening sites. Since equipping all educational institutions was not even remotely feasible, this plan determined a hierarchization and priority scheme for teaching facilities suggesting quotas: institutions for higher education (VUZ) and vocational schools had a cinefication priority of 100% which meant that all facilities from this cohort had to be equipped with permanent film projectors, as compared to secondary schools (with a 50% rate). Primary schools and others (6%) were ranked even lower in priority to get an in-door screening opportunity.39 Although there was a sufficient amount of screening equipment to accomplish this task since the Soviet film equipment manufacturers produced a large number of domestic stationary and mobile projectors, this process went ahead very slowly. A study stated that by 1930 only 341 (of a total of 149.00040) learning sites in the RSFSR, including children’s houses and pioneer units (pionerotriady), were equipped with screening devices.41 By the end of 1931, only a total of 1265 (of 120.000) schools had their own screening device.42

Even though schools started to slowly, but steadily acquire screening equipment, its technical features were far from ideal. Films were still exhibited on 35mm inflammable gauge. Film projectors were bulky, broke often and needed, in most cases, the assistance of a projectionist (kinomekhanik) who handled the device and had to be hired additionally producing extra expenses hardly affordable for schools. At that time, the Soviet Union produced two silent film projectors that were deployed for school use, the models TOMP and GOZ – the first for permanent, the second for makeshift installations – ,43 but heavily relied on technological imports from the West (i.e. the adapted Pathé Nr. 2 was also in wide use). The GOZ, the Pathé and the UKRAINKA projectors, however, posed challenges for pedagogical work in the classroom or the film cabinet, since the noise they produced risked distressing pupils and made additional commentary by teachers during the screening impossible.44 (In general, films in schools were screened as silent pictures far into the mid-1930s.) Moreover, the costs for the GOZ projector i.e. amounted in 1933 to 1700–1800 rubles as one-time expense and 3800 rubles running costs per year that covered the waiting of the device, the hiring of a projectionist, film rental and delivery.45 The TOMP Nr. 4 projector, although technically more reliable, devoured even more financial means for a school to afford, particularly in the countryside.

Disregarding the struggles of the film industry with the introduction of sound cinema, enthusiasts for the cinefication effort like film educator Lazar’ Sukharebskii pushed the idea of providing schools with ‘school projectors.’ Sukharebskii advocated for the use of a narrow-gauge screening equipment since it was more suitable for schools than the bulky and noisy devices running inflammable film reel making it “a flexible tool in the hands of the teacher,”46 but which did not exist in the Soviet Union except as a foreign import. The first domestically produced prototype was not developed until the 1930s.47 Sukharebskii who traveled Europe and attended conferences on educational film was closely familiar with the European achievements in this field which he praised in multiple publications as an example for emulation at home. He particularly applauded the mass production of narrow-gauge projectors and film reel that i.e. in Germany entered the schools already in the mid-1920s. To Sukharebskii, the advantages of this technology were obvious and it would no less than ‘revolutionize’ the educational possibilities of film. Much easier to operate by teachers, it would allow for schools to afford a permanent film device and to establish small film libraries in schools and larger ones on district or regional level at departments of national education (ONOs) or at Narkompros’ departments. In contrast to the few features of traditional projectors, educational films on narrow gauge could be paused and run backwards, separate film sequences could be repeated, and even played in stop-motion mode to draw pupils’ attention to particular parts which increased the flexibility and ease of film use as an educational tool in class. With mass production, he claimed, the costs for schools would reduce to 350 rubles per projector. Sukharebskii saw potential progress not only for schools, but advocated for a broad campaign to implement this technology in pedagogy, science and technology.48

3. Film Repertoire and Production

With the cinefication effort and advances in the technological base underway, the supply of schools with educational films posed another problem. Still in 1935, scientists supervising and monitoring the deployment of film in the classroom bemoaned the absence of an appropriate repertoire of educational films that would match the educational curriculum and the age-specific requirements for children of different grades.49 Although production of films already started in the end of the 1920s, impatience prevailed among educators as quality and quantity of the output did not comply to their demands. Furthermore, their ambitions spurred far ahead with plans to establish a large film collection (kinofond) the films of which would be distributed through a broad network of regional branches with distribution agencies supplying local film libraries with film prints.50 Initially, the “planful production of school films” was started at the kul’turfil’m studio at Sovkino and, to a lesser degree, by Mezhrabpom, VUFKU (All-Ukrainian Photo and Cinema Administration), and smaller commercial film initiatives.51 These dispersed attempts were stopped after the restructuring of the film industry around 1930 that led to further centralization of the different functions of the film industry and fostered the stronger separation between the major genres of fiction, documentary, and ‘useful’ cinema for education and technical instruction.52

In this context, Soviet film administration founded the film trust Soiuztekhfil’m specialized in scientific, instructional and educational films. The Soiuztekhfil’m trust began its production in 1932 with the first studios in Moscow, Leningrad followed in 1933, Kiev and Novosibirsk in 1938. The output of films by these studios was commissioned among others by the departments of national education (ONOs), subordinated to Narkompros, according to ‘thematic plans’ provided by the Narkompros. Thematic planning was introduced into the film industry as an attempt to adopt the general principles of planning and command economy beginning with the alignment of production to the five-year plans starting in 1928. Central planning was conceived, in opposition to the ‘erratic’ and ‘exploitative’ market economy, as a means of efficiency and assurance of a fair distribution of means on the one hand, and political control of cultural output on the other.53 The thematic plan (tematicheskii plan) became the central feature for cultural and specifically cinematographic production. It consisted of a collection of topics to be adapted to film one year or a few years into the future.54 Such thematic plans, or templany as they were also called, were supposed to be compiled with the expertise of pedagogues and educators involving the educational facilities as the principal clients for the use of films, while in reality the first plans were composed in a chaotic and ignorant manner by the commissioner at Narkompros. Particularly in the very first issues of the journal Educational Cinema (Uchebnoe Kino) issued by the film trust,55 we find a lot of criticism dedicated to the question of thematic planning. The central shortcomings that were voiced concerned, among others, the lack of collaborating spirit between film professionals and pedagogues, as well as a lack of coordination between different professional groups and the studio management.56 The defects in planning were responsible for the slow initial production process which was not yet adjusted to the requirements for school use and the specifics of child viewers. Film production lagged behind the efforts already underway to equip schools with screening opportunities, leaving them without suitable films at their disposal.

However, the problem of the provisional film deficiency was to be solved with the re-use of the large kul’turfil’m collection that was stored at Sovkino that was regarded as a ‘palleative’ solution to the shortage of suitable films57 in the “crisis in the educational film market.”58Kul’turfil’ms were the primary nonfiction genre for the enlightenment of the masses in the 1920s (until they were replaced by the film types documentary and scientific film in the 1930s) and the repertoire of which ranged from health education and travel films to advertisements.59 With the gradual dissolution of Sovkino, the film collection that encompassed 450 film titles was revised, categorized and re-issued by a commission of pedagogical experts to assess its usefulness for the classroom. The commission seized 53 pictures from distribution altogether and 170 were taken to be repurposed for the school film circuit with the rest deemed inappropriate for teaching. The reviewing process was not only guided by content criteria: “In determining whether or not a film was unsuitable, the commission was guided by the following considerations: poor development of subject matter, obsolete content, unfinished and meaningless films, tattered and dilapidated film prints, ideological harm, and uselessness.”60 The repurposing of films was practiced in two ways. A part of the films could be used without alterations, whereas the other part required re-editing which was to become a significant practice in adjusting films for school use by pedagogues and educators. This process foresaw the elimination of larger ‘defects’ of content and form, the excessive use of ‘illiterate and unscientific’ intertitles and outdated images as well as the combination of similar films into one thematic picture. The remaking of the film repertoire included also an ideological lifting of the films “to be more in line with the general tasks associated with the reconstruction period in the USSR.”61

4. Educational Films as Teaching Aids

From the early haphazard forms of serving schools with films with the support of public and educational organizations, cinema gained a more solid place in schools in the beginning of the 1930s. This evolution of practices and activities in this field was due to technological advancement in equipping schools with projectors and screening devices, developments in pedagogical areas like the introduction of courses for the training of pedagogues and further experimental work by scientists in the theoretical and methodological field. Although some research centers dedicated to the question of film perception among children and youth closed down at the end of the 1920s, scientists continued to play an important role in the adoption of cinema in schools. They kept investigating how school children engaged with different forms of educational cinema in the particular setting of education, yet with a rather more narrow focus on film construction and pedagogical methodology. The central research institutions of the 1930s that combined the support of schools in the tasks of film use with monitoring and investigating its impact on the perception of child viewers and its effectiveness for educational purposes were research centers at the Baumanskaia film station, the TsDKhVD (Central House of Children’s Aesthetic Education) and VGIK (All-Union State Institute for Cinematography). All research cells were based in Moscow and, although different in their research design and methodology,62 worked alongside film professionals and film studios assisting them with psychological and pedagogical requirements for film construction and providing methodological materials on film use for pedagogues.

Even though the introduction of cinema to schools in the late 1920s was a slow and resource-intensive process, in Moscow the cinefication of schools quickly showed preliminary results. 50% of Moscow schools had conducted film screenings (with a maximum of 25 events per school) in the school year 1927/28, most of them at external screening venues. Of a total of 84 films, 19 narrowly ‘scientific’ films63 were screened that could be integrated into the curriculum which was desired by pedagogues. In the rather rare cases of in-house school screenings, the schools were primarily served by mobile projector equipment. Only in a few instances (40 Moscow schools in 1927/28), schools had film projectors and screening facilities at their disposal,64 which was the result of multiple efforts undertaken by “state organs (NKP, MONO), cinema organizations (Sovkino, ODSK, ARK) as well as pedagogical institutes (GUS, institutes for school and extra-curricular activities, MONO central pedagogical laboratory).”65 Educators like Mark Kresin regarded film service via mobile cinema stations as an ‘insufficient’ form of school film use, since it imposed loads of organizational tasks on schools and required the workings of a complex logistics. Kresin argued that only with their own equipment, technical staff and pedagogical expertise schools could independently conduct film work.66

To underline the need for broader cinefication, Kresin brings forth shortcomings experienced at early extra-curricular film events and the organizational failings that were at times discouraging for the advancement of school films. These shortcomings concerned organizational and technical as well as financial issues. As an attempt to save on effort and money, schools organized collective school screenings in which they gathered clusters of groups from several nearby schools. However, “[o]nly few schools allow[ed] to host such film screenings [screenings for collectives of schools], since children behave at another school completely undisciplined, rooms become littered, school life is disrupted, [there are] special problems with the wardrobe and other motives are usually put forward by the school when offered group film service.”67 On another occasion, a school celebrating the anniversary of the Paris Commune organized a tribute to the revolutionary movement in France that was supposed to include a lecture, music, an exhibition, a play as well as a film show with commentary, when the film screening was disrupted due to the lack of suitable and at the same time available films. Other unfortunate instances concerned the cancellation of film service for suburban schools due to inability to meet an agreement with the mobile cinema brigade.68

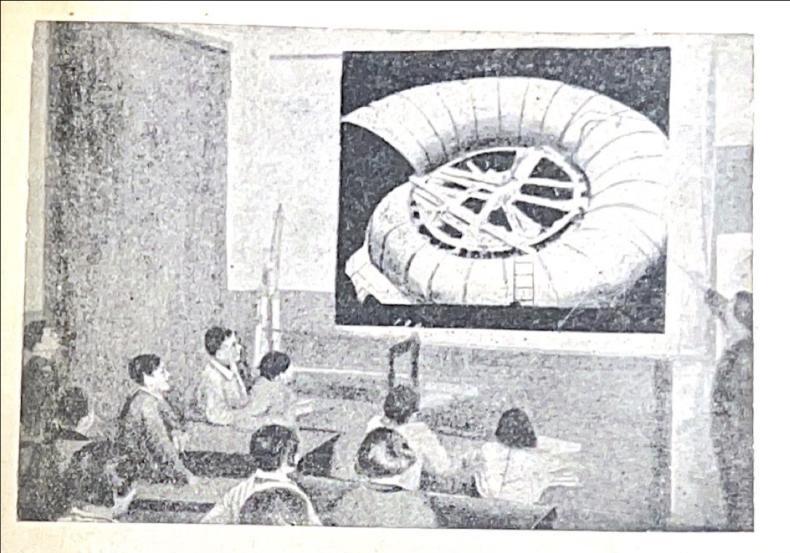

The ability to show films in the classroom, the school cabinet or hall was also a necessary condition for the changing mode of film use in schools and the emergence of the notion of cinema as a teaching aid (kinoposobie). Film was thought of as a new teaching tool in the hands of the teacher who organized and managed the school lesson and who had different visual means for illustration at their disposal being able to present film excerpts during class when needed. Pedagogical specialists worked on the methods of how to best accomplish this, they investigated the psychological and pedagogical implications and possibilities of how to effectively apply film in the classroom. This capacity of adopting film as a teaching aid was linked to the notion of the pedagogically organized film lesson.

In the writings on educational film, the concept of the film lesson (kinourok)69 denoted in most general terms the use of film in class and was distinguished from the ‘film lecture’ (kinolektsiia)70 that was primarily associated with extra-curricular and out-of-school film screenings for school classes accompanied by a thematic lecture or commentary provided by a pedagogue.71 With the differentiation of various forms of film adoption in class, kinolektsiia became a synonym for a badly organized film class that consisted only of a film demonstration consuming the whole time of a lesson and substituting the teacher whose function was reduced to starting the projector and reading the intertitles. The notion of kinolektsiia was, therefore, contradictory to the idea of film as a teaching aid that constituted only one component of the film lesson (next to class discussion or other visual aid) and that was under the guidance of the teacher. With the expansion of the use of films in schools, the concept of the film lesson was fortified and mainly distinguished by the extent of pedagogical effort that was put into it. We have little knowledge of film deployment in the countryside – apart from pedagogues’ complaints of a shortage of film prints for schools in the regions.72 But we can draw on several accounts of film deployment in urban schools where the cinefication effort showed significant progress.

The Baumanskii district in Moscow was the most active in implementing cinema in schools. The district reached full cinefication (sploshnaia kinofikatsiia) between the years 1931 and 1934 with 24 schools fully equipped with screening devices.73 And in the school year 1933/34 alone, the schools in this district managed to screen 260 educational films altogether.74 The network of schools in the district cooperated closely with the film station of the same name. The brigade of the Baumanskaia film station organized and conducted educational film screenings in schools that were observed and evaluated by a group of pedagogues, pedologists, psychologists and educators who not only researched the children’s perception of films, but also their effectiveness as a modern teaching aid.75 In order to determine their role and function in relation to the pedagogical input, the Baumanskaia group observed a large number of film lessons. The researchers focused their attention on the interaction between teacher, class and the different modes of applying films as a teaching device. They were interested in systematizing the pedagogical work with films distinguishing different types of film lessons. Besides, they sought to determine the specific function of films in the process of a lesson and to differentiate various types of films serving pedagogical aims. The Baumanskaia film station also provided additional service to the schools under their patronage to foster the adoption of films: “The school receives films according to a firmly established plan, on a circular system. Teachers have the opportunity to see films in advance and receive comprehensive advice at the film station. Finally, for each film lesson, the teacher receives a methodical instruction compiled according to the given subject.”76

The distinction between the Baumanskaia film station and institutes like the sector for the study of film perception at VGIK or the children’s cinema workshop at the TsDKhVD that were more affiliated with the film studios of Soiuztekhfil’m was that the latter (gaining importance in the 1930s) were more focused on deploying and testing the new film production77 on school children.78 The Baumanskaia film station that was involved in pedagogical work from the 1920s (with a large experience of adapting and re-editing kul’turfil’ms to the curricular requirements of different school subject) was more routinized in working with the old (Sovkino) film collection and therefore preferred a particular method of inquiry. Rather than providing film studios with practical knowledge of how films should effectively be built for a maximal effect, pedagogues of the Baumanskaia film station focused on observing teachers in their film use in the pedagogical process and elaborating ways of how to utilize film during a film lesson. One of their methodological priorities was to view films as modular constructions the parts of which could be used variably. Based on the assumption that films should be taken as repository for useful material that could be used independently from the whole according to the needs of the respective lesson, the methodological priority was to instruct teachers in extracting and combining filmic material with other teaching aids. Respectively, lessons were also conceived as modularized, segmented into didactic parts framing the film (roughly: introduction, tasks, film screening with commentary by the teacher, discussion)79 which became the basis for the methodical instructions that the research groups developed for teachers.80

In their observational research, the scholars of the school section of the Baumaskaia film station distinguished five types of film lessons that they observed evolving during the years of study. This attribution was made according to the pedagogical integration into the class process by the pedagogues: “1) film projection without any teacher involvement, 2) the reading of intertitles by the teacher and giving short explanations during the projection, 3) unsuccessful attempts to include film as one of the class elements in an ordinary lesson, 4) film-lecture, ‘continuous accompaniment’ of the film by the teacher, and 5) actual, with maximum efficiency, use of film as a visual teaching aid during the lesson.”81 While the first four types were attributed to a premature state of film use with little involvement of the teacher and without further elaboration on the film viewing, the fifth type accounted for the most elaborate prototype of film lesson that fully deserved the term. In type one and two the film is treated as an independent work that is demonstrated to fill the whole lesson, in which the pedagogues do not acknowledge the specificity of the filmic experience and do not account for the linkage of the film with the subject. Taking up valuable class time and risking to exhaust child-viewers, the film’s comprehensiveness is not guaranteed in these cases, since the teacher’s occasional commentary is not evidently comprehensible. Type three and four present efforts to include the film into the class subject, acknowledging cinema’s visual means for illustration and exemplification and the pedagogue’s commentary serves as a help for comprehension.

To expose the lack of methodical expertise and ineptitude of the pedagogues, the authors provide comical examples of the ineffectiveness of these types of film lessons. The pedagogically inadequate handling of films is depicted in anecdotal accounts (many of which were recorded by the scientists during their work). After a screening of the 12 minutes health kul’tur’film NE PLIUI NA POL / DON’T SPIT ON THE FLOOR (USSR 1929, directed by V. Shirokov82) from 1929 among first-graders, as part of a class on the topic of public health, the teacher made a drawing of a spittoon on the blackboard and asked the pupils to reproduce the drawing in their notebooks for the remaining time of the class. When the same film was shown at another school, the teacher interrogating the pupils about the conclusions that can be drawn from the film repeated the same conversation with each pupil individually over and over again until the end of the class.

— Petya, tell me, what picture did you see?

— Don’t spit on the floor.

— What is in the spit?

— Germs.

— What do germs spread?

— Disease.

— Where do you spit?

— In the spittoon.83

Depicted as an animated kino-plakat (stylized with signaling letters alternating with microscopic bacteria) and intended as an agitational warning against tuberculosis, DON’T SPIT ON THE FLOOR is a visually challenging spectacle not least because of the bold device in the beginning of the hooligan-protagonist frontally facing the camera and spitting in the direction of the audience.84 The numerous dissolves of mouths, bacteria-filled petri-dishes, animated globes and short scenes showing people in hygienically desolate states and provoking disgust must have irritated an audience of first-graders, yet remained, according to the lesson’s record, uncommented upon by the teacher.

The last type of film lesson, figuring as the ideal type, envisages the use of film as a genuine visual teaching aid that is utilized by the teacher during class to guide the pupils’ process of knowledge: “educational film can only be a truly educational tool [uchebnym posobiem] if the teacher gives the children’s perception the necessary direction for the purpose of learning.”85 Even as this type of film use encompassed a variety of different forms, it implies typical characteristics and goals (didactical forms: breaks, short physical exercise [fizkul’turminutka] etc.) as “1) the complete alignment of the film lesson to the programmatic material of the subject, 2) accurate understanding of the teacher, as well as the children, of the goal of the lesson and the subordination of the entire content of the picture and the lesson to this goal; 3) the working atmosphere of the film lesson and the students’ awareness of their full responsibility for mastering the film lesson material, as well as the fact that they are fully responsible for the content of the film lesson.”86 A particularly sophisticated form of film lesson was conducted by a teacher for the third grade in a natural sciences class with the film TSEMENT / CONCRETE (USSR, 1930).87 After a minute of physical exercise (fizkul’turminutka), pupils were seated followed by an introduction by the teacher noting questions on the blackboard for discussion after the demonstration of the film. The film, divided into different semantic components through breaks, was intermitted by the showing of a map that indicated the regions for the production of concrete and by an experiment: pupils were given concrete powder that they lowered into water to demonstrate its hardening. The teacher concluded the lesson with returning to the questions on the blackboard. This ideal ‘film lesson’ testifies to the growing role the teachers played in the adoption of film and their principal function as organizers of the school lesson.

In their following contributions on film use in school in anthologies and journals, educators from the Baumanskaia film station focused on specifying the methodologies, techniques and practices of this fifth type. Apart from analyses of the general forms of film use and their effects on children’s comprehension, attention and work capabilities, the scientists also provided methodological instructions for the effective use of films in the classroom. They elaborated on the psychological and pedagogical requirements of films for the group being taught, their age specificities and psychological pre-conditions. Since film was regarded by the pedagogues as a ‘strong stimulus’ (iarkii razdrazhitel’)88 with great emotional impact on children, they believed that employed in the correct manner pedagogues could exploit cinema’s emotional power to activate the knowledge process, to organize the children’s attention towards the significant aspects and to build a lesson dramaturgy in which its elements would build an organic whole.89 The pedagogical recommendations compiled by scientists were distributed as instructional leaflets among teachers as so-called metodrazrabotki (literally: ‘methodical elaborations’) which Sukharebskii also dubbed as “printed film lessons.”90

5. Conclusion

The trajectory of educational cinema in the Soviet Union shows features of institutionalization, understood as a way of consolidation of a material infrastructure, knowledge and practices, that shares common features with international developments that manifested already in the 1910s and 1920s in Europe and North America. These developments encompassed the attempts to counter the harmful allure of commercial cinema for children when educators, scientists and cinema reformers advocated for a culturally and educationally purposeful cinema, the creation of a nontheatrical infrastructure for the distribution of films as well as pedagogical adjustments and practices that contributed to the familiarization of school children with classroom screenings. Therefore, the Soviet case should be regarded in the context of transnational developments that need further study to establish the concrete connections and contact zones between Western and Soviet actors in that field.

However, the Soviet case also reveals unique features. Soviet educational cinema heavily relied on an infrastructure that was bound to state institutions as i.e. the process of the cinefication was primarily organized and financed by the educational organizations that were under the formal control of Narkompros. And as long as educational cinema was considered a priority, it was supported financially and organizationally, and pressure was exerted on the respective agencies.

The focus on the period between the 1920s and mid–1930s, the booming years of educational cinema in the Soviet Union, stands for an intensification in interest from public, political, cinema and educational organizations which began to diminish in the second half of the 1930s. One clear sign for this was the decrease in publications on the topic – for example the journal Educational Cinema edited by Soiuztekhfil’m only existed until 1936 and was closed down. In this context, a decisive turning point, at least from the point of view of the film industry, marked the All-Union Meeting on Educational and Scientific Cinematography convening in 1934/35 which called for a new direction in educational and scientific film production. Aligning this claim with a rigorous criticism of educational film production as “dry, incomprehensible, tiresome, and therefore pedagogically ineffective,”91 the general demand was to shift the film production towards popular scientific films addressing a mass audience to heighten the cultural level of the average worker.

- 1Anatolii Lunacharsky, “Conversation with Lenin. I. Of all the arts… [1925],” in The Film Factory. Russian and Soviet Cinema in Documents 1896-1939, ed. Richard Taylor and Ian Christie (London/New York: Routledge, 1994), 57.

- 2Cf. Roman G. Grigor’ev, [Speech at the plenary session of the conference]. In Vsesoiuznaia tvorcheskaia konferentsiia rabotnikov kinematografii. Stenograficheskii otchet [All-Union creative conference of cinematographic workers. Verbatim record] (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1959), 240. Historians of cinema underline that Lenin himself even recommended the production of scientific films on the extraction of turf for industrial use. (Cf. Igor’ Vasil’kov, Nauchno-populiarnoe kino [Popular scientific film] (Moscow: Znanie, 1977), 3.)

- 3Literally Narkompros translates as People’s Commissariat of Enlightenment. This entity served as the Ministry of Education and under Anatolii Lunacharskii (1917–1929) also administered the arts, including cinema, and cultural affairs. (Cf. Sheila Fitzpatrick, The Commissariat of Enlightenment. Soviet Organization of Education and the Arts under Lunacharsky.October 1917–1929 (Cambridge: University Press, 1970).) Other departments that were involved in the advancement of cinema for schools like the Glavpolitprosvet (Chief Administration for Political Education), Glavsotsvos (Chief Administration for Social Training [School Education]) and MONO (Moscow Education Department) were under formal control of the Narkompros.

- 4Denise Youngblood, “Entertainment or enlightenment? Popular cinema in the Soviet society, 1921–1931,” in New Directions in Soviet History, ed. Stephen White (Cambridge: University Press, 1992).

- 5Exceptions would be Leont’eva, S. G., “Fil’ma ili knizhnyi uchebnik: k istorii odnoi pedagogicheskoi diskussii [Film or textbook: on the history of a pedagogical discussion],” in Uchebnyi tekst v sovetskoi shkole [Educational text in the Soviet school], ed. S. G. Leont’eva and K. A. Maslinskii, (St. Petersburg/Moscow, 2008a); Svetlana Leont‘eva, 2008b. “Diskussija o ‘zhivom slove’: k istorii mediaobrazovaniia v sovetskoi shkole [Discussions on the ‘live word’: on the history of media education in the Soviet school],” Intelros no. 2 (2008b), http://www.intelros.ru/readroom/nz/nz_58/2396-diskussija-o-zhivom-slove…; S. I. Cherepinskii, Uchebnoe kino: Istoriia stanovleniia, sovremennoe sostoianie, tendencii razvitiia didakticheskikh idei [Educational cinema: History of formation, current state, trends in the development of didactic ideas], Voronezh, 1989.

- 6Cf. Boris Diushen, “Beglye vospominaniia [Fleeting memories],” Kinovedcheskie zapiski [Film studies notes] 64 (2003): 181–182.

- 7The recently published volume The Institutionalization of Educational Cinema centers around the notion of institutionalization as a comprehensive tool that allows for comparison between international case studies that despite their individual trajectories share common developments in educational cinema at the beginning of the 20th century. Cf. Marina Dahlquist and Joel Frykholm, eds., The Institutionalization of Educational Cinema. North America and Europe in the 1910s and 1920s (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2020). According to the volume’s editors, institutionalization is characterized „by the ways in which discourses, cultural practices, technical standards, and institutional frameworks coevolved according to patterns that transformed educational cinema from a convincing idea into an enduring institution.” (Ibid., 2) For a comparative perspective see also Devin Orgeron, Marsha Orgeron and Dan Streible, eds., Learning With the Lights Off. Educational Film in the United States (New York: Oxford University Press: 2012).

- 8Eef Masson, Watch and Learn. Rhetorical Devices in Classroom Films After 1940 (Amsterdam: University Press, 2012), 13.

- 9Sheila Fitzpatrick, Education and Social Mobility in the Soviet Union 1921–1934 (Cambridge et al.: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 140.

- 10Cf. Lazar' Sukharebskii, Uchebnoe kino [Educational Cinema]. With a foreword by Anatolii Lunacharskii (Moscow: Teakino-pechat', 1929a).

- 11The anthology Detskoe kino [Cinema for Children] (ed. M. S. Epshtein (Moscow: Teakinopechat’, 1930).) that figures as one of the first publications in the Soviet Union to cover the question of cinema for schools in a systematic way and includes contributions from principal experts in this field predominantly makes wide use of the notion ‘school film’.

- 12The conflation also resulted from the fact that both film types were produced in the same film studios organized under the film trust Soiutekhfil’m. In light of the rapid industrialization and the introduction of the First Five-Year Plan the production of instructional films (or technical films, as they were also called alternatively) became an economic asset, since it was said that they enormously shortened the familiarization with and the training phase on new machines. So-called cinematic courses for the training of car and tractor drivers (Avtomobil’) were considered one particularly effective example of film-based technical instruction at factory workshops. They featured scripts by such figures as Viktor Shklovskii and Osip Brik and were partly produced as sound films as soon as 1932. This description serves as a short characterization of this series: “They [the films] are mostly devoted to an overview of the latest technology, with a cursory explanation of the construction or explanation of the rules of operation and maintenance of machines.” (B. A. Al’tshuler and M. D. Nechaeva, “Razvitie sovetskogo nauchno-populiarnogo kino [The Development of the Soviet Popular Scientific Film],” in Ocherki istorii sovetskogo kino v trekh tomakh. T. 3 (1946–1956) [Essays on the History of Soviet Cinema in Three Volumes. Vol. 3 (1946–1956)], ed. Iu. S. Kalashnikov et al. (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1961), 561.)

- 13A film catalogues compiling the film production of the year 1938 uses the denotation ‘school education films’ to refer to this more narrow understanding (V. Vishnevskii and V. Fefer, Ezhegodnik sovetskoi kinematografii za 1938 god [Annual for the Soviet Cinematography for 1938] (Moscow: Goskinoizdat, 1939).

- 14Sukharebskii, Uchebnoe kino [Educational cinema]. With a foreword by A. V. Lunacharskii (Moscow: Teakino-pechat’, 1929a). Sukharebskii particularly emphasized the significance of institutes promoting the idea of educational cinema, the organizational infrastructure of film supply for schools and advances in development of film technology abroad as he was familiar with the developments in Europe as a result of his travels to Germany related to the study of educational and scientific cinema. He also pushed the idea to establish a central state institute for school cinematography in the Soviet Union that eventually remained a paper draft, but probably was modelled on European examples. (L. Sukharebskii, “Institut detsko-shkol’noi kinematografii [Institute for School Cinematography],” in Detskoe kino [Cinema for Children], ed. M. S. Epshtein (Moscow: Teakinopechat’, 1930).) Furthermore, in the summery of their research results on the usage of film in elementary school, the pedologists N. Arnol’d, Ts. Kiselev and M. Polonskii draw upon the studies on the effectiveness of visual education carried out by the Chicago University in various cities during 1922–24. The Soviet studies shows similarities in the research design to the US case, which hints to the fact that Soviet scientists borrowed methods from their Western counterparts. The authors most likely referred to the research conducted under the supervision of Frank Freeman – cf. Frank N. Freeman, ed., Visual Education: A Comparative Study of Motion Pictures and Other Methods of Instruction (Chicago: Unversity of Chicago Press, 1924) – (N. Arnol’d, Ts. Kiselev and M. Polonskii, “Ispol’zovanie kino v nachal’noi shkole (Iz opyta raboty Baumanskoi kinostantsii) [The usage of film in elementary school (From the work experience of the Baumanskaia film station)],” Shkol’no-uchebnyi fil’m [School education film], ed. Boris S. Peres (Moscow: Kinofotoizdat, 1935).)

- 15Cf. Arnol’d, Kiselev and Polonskii, “Ispol’zovanie kino,” 19: The Soviet school differed from the bourgeois school in its “ideological and practical base […], the different methods of schoolwork and means of activization of the children’s learning abilities, contributing to the activity of high achievers, and the impact of pioneers and komsomol’s […].”

- 16Anna Latsis and L. Keilina, Deti i kino [Children and Cinema] (Moscow: Teakinopechat’, 1928), 45.

- 17Anna Toropova, “Probing the Heart and Mind of the Viewer: Scientific Studies of Film and Theater Spectators in the Soviet Union, 1917–1936,” Slavic Review 76, no. 4 (2017): 931f.

- 18Vladimir A. Pravdoliubov, Kino i nasha molodezh. Na osnove dannykh pedologii. Dlia shkol, roditelei, vospitatelei i kinorabotnikov [Cinema and Our Youth. Based on Data in Pedology. For Schools, Parents, Educators and Cinema Workers] (Moscow/Leningrad: Gosudarstvennoe izdatel’stvo, 1929).

- 19Anna Leitsis and L. Keilina, Deti i kino, 10–12.

- 20Anna Toropova, “Science, Medicine and the Creation of a ‘Healthy’ Soviet Cinema,” Journal of Contemporary History 55, no. 1 (2020): 13.

- 21Toropova, “Science,” 11–13. Cf. also Abram M. Gel’mont, “Kino i vospitanie [Cinema and Education],” in Kino – deti – shkola. Metodicheskii sbornik po kino-rabote s det’mi [Cinema – Children – School. A Methodical Anthology on Film Work with Children], ed. Abram M. Gel’mont (Moscow: Rabotnik prosveshcheniia, 1929), 7.

- 22Toropova, “Science,” 14–18.

- 23Cf. exemplary studies: W. W. Charters, Motion Pictures and Youth: A Summary (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1933); Henry James Forman, Our Movie Made Children (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1934). For an overview over the controversies around the Payne Fund Studies cf. Fuller-Seeley, Kathryn, Garth Jowett, and Ian C. Jarvie, Children and the Movies:Media Influence and the Payne Fund Controversy (Cambridge: University Press, 1996).

- 24Iuliia I. Menzhinskaia, “Massovaia kino-rabota s det’mi v Moskve i metody ee provedeniia [Mass Film Work with Children in Moscow and Methods of its Realization].” In Kino – deti – shkola. Metodicheskii sbornik po kino-rabote s det’mi [Cinema – Children – School. A Methodical Anthology on Film Work with Children], ed. Abram M. Gel’mont, (Moscow: Rabotnik prosveshcheniia, 1929).

- 25Toropova, “Science,” 17.

- 26Boris Peres, “Pervye shagi shkol’noi fil’my [First Steps of School Film],” in Detskoe kino [Cinema for Children], ed. M. S. Epshtein (Moscow: Teakinopechat’, 1930), 33.

- 27“Iz materialov pervogo vsesoiuznogo partiinogo kinosoveshchaniia pri TsK VKP(b), 15–21 marta 1928g. [From the materials of the first All-Union Party Cinema Conference by the Central Committee of the TsK VKP(b) March 15th–21st 1928],” in KPSS o kul’ture, prosveshchenie i nauke. Sbornik dokumentov [KPSS on Culture, Education and Science. Anthology of Documents], ed. V. Gurevich (Moscow: Izdatel’stvo politicheskoi literatury, 1963), 165, 168.

- 28The documents were: Resolution of the Central Committee VKP(b) from August 25th 1931 on Elementary, https://istmat.org/node/53561, and Middle School and Resolution of the Central Committee VKP(b) from August 25th 1932 on the Curriculums and the Regime at Elementary and Middle School, https://istmat.org/node/57330.

- 29Fitzpatrick, Education, 5.

- 30Resolution from August 25th 1931.

- 31Fitzpatrick, Education, 19–22. Re-introducing formal subjects into the school curriculum meant a curtailing of progressive pedagogical ideals that among others were inspired by John Dewey and proliferated in the second half of the 1920s and were associated with the so-called complex method or project work. The complex method fostered a liberal and experiential form of learning of socially oriented themes that children would associate with and integrate into their experience of the world which would be activated through practical modes of learning like the experiment or the excursion. (Fitzpatrick, Commissariat of Enlightenment, 29–32.)

- 32The resolution obliged the “Narkompros in cooperation with cinema organizations to develop measures for the use of cinema for school, especially for its polytechnization [politekhnizatsii].” (Resolution from August 25th 1931.)

- 33Aleksandr Shirvindt and Lazar’ Sukharebskii, Kinofikatsiia shkoly [Cinefication of the School] (Moscow: Teakinopechat’, 1930). Sukharebskii and Shirvindt make the attempt to align cinema with the curricular requirements of the school and the administration of education in general, outlining the technical, pedagogical and film repertoire conditions for the deployment of cinema in Soviet schools.

- 34Vance Kepley, “‘Cinefication’: Soviet Film Exhibition in the 1920s,” Film History 6, no. 2 (Summer, 1994): 262–277.

- 35Jamie Miller, “Soviet Cinema, 1929–41: The Development of Industry and Infrastructure,” Europe-Asia Studies 58, no. 1 (2006), 103–124.

- 36Abram M. Gel’mont et al., Spravochnik po uchebnomu kino v nachalnoi i srednei shkole [Reference Guide to Educational Film in Elementary and Secondary School] (Moscow: Roskino, 1933), 8–11.

- 37Most projectors had to be installed as fixed devices in a booth due to fire safety conditions since films in schools were still screened from inflammable film copies.

- 38Latsis and Keilina, Deti i kino, 51; Peres, “Pervye shagi,” 33. A specialized children’s movie theaters like the former Balkan theater renamed in Detkino (Children’s Cinema) in Moscow was a unique attempt to establish film programs for children on a regular basis. It opened in 1928 and eventually closed down seven months later despite its engaging pedagogical work for children and youth because it produced 6000 rubles in deficit during one season. (Anon., “Sezon raboty pervogo detskogo kino-teatra [Work Season of the First Children’s Movie Theater],” in Kino – deti – shkola. Metodicheskii sbornik po kino-rabote s det’mi [Cinema – Children – School. A Methodical Anthology on Film Work with Children], ed. Abram M. Gel’mont, (Moscow: Rabotnik prosveshcheniia], 1930), 81–97.)

- 39Shirvindt and Sukharebskii, Kinofikatsiia, 32f.

- 40Cinefication took place at the same time as the school network expanded over the years of the cultural revolution.

- 41Shirvindt and Sukharebskii, Kinofikatsiia, 7, 27.

- 42Gel’mont at al., Spravochnik, 9.

- 43The projectors were named after the state facilities in which they were produced. GOZ stands for Gosudarstvennyi opticheskii zavod [State Optical Factory] and TOMP refers to Trest optiko-mekhanicheskoi promyshlennosti [Trust for the Optical Mechanical Industry].

- 44Latsis and Keilina, Deti i kino, 49; Gel’mont et al., Spravochnik, 12.

- 45Gel’mont et al., Spravochnik, 11f.

- 46L. Keilina, “Kinofikatsiia shkol’noi seti [Cinefication of the School Network],” in Detskoe kino. [Cinema for Children], ed. M. S. Epstein (Moscow: Teakinopechat’, 1930), 23–26.

- 47As with the general cinefication, the schools competed for narrow-gauge projectors with other facilities for cultural enlightenment like clubs in the villages or cultural houses.

- 48Sukharebskii, L., “Uzkoplenochnaia kinematografiia [Narrow-Gauge Cinematography],” Uchebnoe kino [Educational Cinema] 4 (1933): 22f.

- 49Arnol’d, Kiselev, and Polonskii, “Ispol’zovanie kino,” 13.

- 50Keilina estimates that 40 copies of one film title should be distributed among ca. 13 regional ONOs to keep in each outlet three copies “on the basis that one copy is in operation, the other is in repair, and the third is in transit.” (Keilina, “Kinofikatsiia,” 24.)

- 51Peres, “Pervye shagi,” 33.

- 52The several documentary producers were also organized into a central film trust Soiuzkinokhronika in 1932. (Cf. Nikolai Lebedev, “Kinokhronika i nauchno-uchebnoe kino v period razvernutogo nastupleniia sotsializma (1930–1934) [Documentary and Scientific Educational Film during the Advanced Period of Socialism (1930–1934)],” in Uchenye zapiski [Academic Notes]. ed. Vsesoiuznyi Gosudarstvennyi Institut Kinematografii [VGIK]. Vol. 1. (Moscow: Iskusstvo, 1959), 242–268.)

- 53Jamie Miller, Soviet Cinema. Politics and Persuasion under Stalin (London/New York: I.B. Tauris, 2010), 81.

- 54For a general overview over thematic planning in the Soviet film industry cf. Maria Belodubrovskaya, Not According to Plan: Filmmaking under Stalin (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017), 52–89.

- 55The journal appeared from 1933 to 1936 and provided the central platform for discussions about educational cinema. Topics for debate were the construction of educational films, i.e. the composition of intertitles, mise-en-scène, and the application of sound, production plans, methodical questions of film use in educational contexts, and film reviews of the Soiuztekhfil’m productions. A variety of specialist participated in these discussions: studio professionals, filmmakers and pedagogues. Educational Cinema also published foreign articles in translation on the pedagogical usage of educational films.

- 56V. Perlin, “Nuzhen ni preiskurant, a templan [We Do Not Need a Price List, but a Thematic Plan],” Uchebnoe kino 1 (1934): 2.

- 57Latsis and Keilina, Deti i kino, 52.

- 58I. F. Shevliakov and B. P. Kashchenko, “K voprosu ob ispol’zovanii fonda politprosvetfil’m Sovkino [On the Question of Using the Enlightenment Film Collection of Sovkino],” In Detskoe kino [Cinema for Children], ed. M. S. Epshtein (Moscow: Teakinopechat’, 1930), 40.

- 59For a comprehensive overview over kul’turfil’ms in the Soviet Union cf. Oksana Sarkisova, “The Adventures of the Kulturfilm in Soviet Russia,” in A Companion to Russian Cinema, ed. Birgit Beumers (Chichester: Wiley Blackwell, 2016); Oksana Sarkisova. Screening Soviet Nationalities: Kulturfilms from the Far North to Central Asia (London: I. B. Tauris, 2017).

- 60Shevliakov and Kashchenko, “K voprosu,” 38.

- 61Ibid.

- 62Cf. Toropova, “Science.”

- 63Interestingly, the films identified as ‘scientific’ were for the most part foreign travelogues and kul’turfil’ms: PROBLEMY PITANIIA / NUTRITIONAL PROBLEMS, PUTESHESTVIIA PO REKE AMAZONKE / TRAVELS ACROSS THE AMAZON RIVER, EKSPEDITSIIA NA EVEREST / EXPEDITION TO EVEREST, GVADELUPA / GUADELOUPE, PO OSTROVU BORNEO / ACROSS THE ISLAND OF BORNEO. (Mark Kresin, “Kinoobsluzhivanie shkol [Film Service for Schools],” in Kino – deti – shkola. Metodicheskii sbornik po kino-rabote s det’mi [Cinema – Children – School. A Methodical Anthology on Film Work with Children], ed. Abram M. Gel’mont, (Moscow: Rabotnik prosveshcheniia, 1929), 230.) It is difficult to attribute these films, since they received new edits and titles when traveling abroad and most of them are lost. However, in the case of the film EKSPEDITSIIA NA EVEREST it is highly likely that it is a version of the expedition film THE EPIC OF EVEREST by John Noel (UK 1924). The description given in the catalogue for children’s screenings makes particular mention of the hairstyles of the Tibetan women that also appear in THE EPIC OF EVEREST. (Kinofil’my dlia detskikh kino-seansov [Films for children’s screenings] (Moscow, 1928), 17.)

- 64Sukharebskii, “Kino v shkole,” 155. Another source says that by 1928 37 Moscow schools had permanently installed projectors (of the GOZ type), 25 of which made systematic use of films for education. (Latsis and Keilina, Deti i kino, 30.) For a list of screened films on this occasion among which also figured Dziga Vertov’s A SIXTH PART OF THE WORLD (USSR 1926) cf. ibid., 30–32.

- 65Abram M. Gel’mont, “Kino kak factor vospitaniia (Mery bor’by s vrednym vliianiem kino na detej i puti sozdaniia pedagogicheskogo kinematografa) [1927] [Cinema as educational factor (Measures to counteract the harmful effects of cinema on children and ways to create a pedagogical cinematography)],” in Revolutsiia – iskusstvo – deti. Materialy i dokumenty. Iz istorii esteticheskogo vospitaniia v sovetskoi wkole 1924–1929 [Revolution – Art – Children. Materials and Documents. From the History of Aesthetic Education in the Soviet School 1924–1929], ed. N.P. Starosel’tseva (Moscow: Prosveshchenie, 1968), 313. This work accomplished by cinema institutions like ARK (Association of Revolutionary Cinematography) and ODSK (Society of Friends of Soviet Cinematography) as well as pedagogical institutions like the IMVR (Institute for Extra-Curricular Activities) and IMShR (Institute for Educational Activities) was criticized for its ‘haphazardness’ (kustarnost’) and unsystematic character that relied on enthusiastic pedagogues to conduct this time-consuming work and only rarely was useful to the educational curriculum.

- 66The wholesale cinefication of schools, although an educator’s dream, was, as Gel’mont stated a few years later into the cinefication effort, an unattainable goal, since most schools could not afford the expenses for projectors, their maintenance and the permanent engagement of a projectionist.

- 67Kresin, “Kinoobsluzhivanie shkol,” 232.

- 68Ibid., 236.

- 69One of the first mentions of film-lesson (kino-urok) can be found in Sukharebskii’s writings. He defines the film-lesson as the teacher’s ‘methodological linkage’ (metodologicheskaia uviazka) of lesson content and selected film (Sukharebskii, “Kino v shkole,” 147f.) and gives a more systematic account of the requirements of the film-lesson: its structure, methods, time schedule, the teacher’s input as well as the combination of the film with other teaching aids (Sukharebskii, Uchebnoe kino, 145–165). Cf. also on the film lesson with respect to the problem of ‘time management’: M. Tikhomirov, “Kino-urok v shkol’nom biudzhete vremeni [Film-Lesson within the School Time Budget],” Uchebnoe kino [Educational Cinema] 1 (1934): 28–30.

- 70Cf. I. Iachmenev, “Kinolektsiia i kinourok (Kak ikh provodit’) [Film Lecture and Film-Lesson (How to Conduct Them)],” Prosveshhenie Sibiri [Enlightenment of Siberia] 1–2 (1933): 95: “The film lecture is based on a continuous commentary of the film by the teacher-lecturer.”

- 71This distinction is reminiscent of attempts to differentiate between ‘educational’ and ‘classroom film’ in other national contexts. Ursula von Keitz in her inquiry into the early attempts to establish films for educational purposes in Germany in the 1910s refers to the distinction of the two film types where ‘educational film’ (Lehrfilm) serves as a general moniker and ‘classroom film’ (Unterrichtsfilm) denotes the adoption of films to a setting of instruction or education. (Ursula von Keitz, “Wissen als Film. Zur Entwicklung des Lehr- und Unterrichtsfilms,” in Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Vol. 2: Weimarer Republik 1918–1933, ed. Klaus Kreimeier, Antje Ehmann, and Jeanpaul Goergen (Stuttgart: Reclam, 2004).) In her study, Eef Masson makes a similar emphasis on the term classroom films to stress the very specific context of their use. (Masson, Watch and Learn.)

- 72In 1933 Vinogradov estimated that in the rural areas only a total of 5–10 educational films were available for distribution. (S. Vinogradov, “Ispol’zovanie kino v shkole [Film Use in School],” Uchebnoe kino [Educational Cinema] 2 (1933): 19.)

- 73Arnol’d, Kiselev, and Polonskii, “Ispol’zovanie kino,” 13. From 1930 to 1933 cinefication of schools in Moscow increased from 30 to 190. This means that one eighth of all cinefied schools was located in the Baumanskii district which underlines its pioneer position.

- 74N. Arnol’d, “Kinourok v nachal’noi shkole [Film-Lesson in Elementary School],” Uchebnoe kino [Educational Cinema] 5 (1934): 8. Among the screened films figured geographical titles like ZHEMCHUZHNYE STEPI (ZHEMCHUZHINA STEPI) / PEARL STEPPES (PEARL OF THE STEPPES) (USSR 1930, a film about a desert preserve and the agriculture in the Dnepr region), ASKANIIA NOVA (USSR 1930, a film about a steppes nature preserve), ZA UROZHAI / FOR THE HARVEST (USSR 1929, directed by Ilya Kopalin for Sovkino), VOLZHSKAIA KOMMUNA / VOLGA COMMUNE (USSR 1930, directed by V. Butomo for Soiuzkino; a film about the political life of a state-owed farm in the Volga region) and KHAKASSIIA (1931; a film about the region of the same name).

- 75The methods of studying the adoption of films in class primarily consisted of methods of observations and their analysis by means of records: “Multiple visits to cinefied schools in the Baumanskii district throughout this period [since the beginning of the cinefication of the district], verbatim records, timekeeping, records of a large number of film lessons and their subsequent pedagogical and pedological analysis […].” (Ts. Kiselev, “Sposoby primeneniia kino v shkolakh FZD (Iz opyza raboty shkol’nogo razdela kinostantsii BONO) [How to Use Film in FZD (Factory Schools) (From the Experience of the School Department of the BONO Film Station)],” Uchebnoe kino [Educational Cinema] 3 (1934): 19).

- 76Arnol’d, “Kinourok,” 8.

- 77These genuine ‘educational films’ differed from the interim solution of adapted and re-edited kul’turfil’ms. The former were produced with the requirement to match the school curriculum and pedagogical and psychological requirement of school children.

- 78Another important inquiry into the problem of educational film as a teaching aid was led by Nikolai Zhinkin, who investigated the effectiveness of educational films for children, since the early 1930s under the sponsorship of the film trust Soiuztekhfil’m, and later changed to VGIK (All-Union State Institute for Cinematography). Zhinkin was an important figure in the field of educational cinema. As a psychologist, he established himself in the field of ‘pedology’ – a discipline that in combining a variety of approaches was instrumental for the study of child audiences during 1920s. Since 1929, he worked for 18 years at Soiuztekhfil’m where he reviewed screenplays as studio editor and realized numerous films as screenwriter and director. Zhinkin was interested in ‘general laws’ of film perception and the optimal comprehension of film content in relation to the logical construction of filmic material. His methods included the demonstration of film clips from films like KAK RABOTAET I USTROENO TELO CHELOVEKA / HOW DOES THE BODY WORK AND HOW IT IS BUILT (USSR 1932, directed by the specialist in medical kul’turfil’m Noi Galkin) that were systematized beforehand according to different rhetorical devices for conveying memorable content. To evaluate the effectiveness of individual film clips and cinematic devices he combined written tests and individual and group discussion. (Cf. Nikolai Zhinkin, “Izuchenie zritelia i problemy postroeniia uchebnoi fil’my [The Inquiry of the Viewer and the Problem of the Composition of Educational Films]),” Uchebnoe kino [Educational Cinema] 6, 14–25.) For an overview over Zhinkin’s professional biography and scientific practice cf. Toropova, “Probing,” 948–950.

- 79All elements of the lesson should be ‘dosed’ (dozirovat’) in a rational proportion in order to create “a single harmoniously coordinated whole.” (M. Polonskii, M. Pol’man, and A. Novikov, “Za kinofikatsiiu shkoly [For the Cinefication of the School],” Iskusstvo i deti [Art and Children] 4 (1932): 33, quoted in: Cherepinskii, Uchebnoe kino, 32.)

- 80Cf. Ts. Kiselev, “Rabota pedagoga s fil’moi [The Pedagogue’s Engagement with Film],” Uchebnoe kino [Educational Cinema] 6 (1934): 2–9.)

- 81Kiselev, “Sposoby primeneniia kino,” 19.

- 82In the reference book (Spravochnik) edited and written by Gel’mont et al. the film is described as difficult even for fourth-graders. “When demonstrating pictures of microbes, the film should be paused and these parts discussed in class.” (56).

- 83Kiselev, “Sposoby primeneniia kino,” 21.

- 84An extensive analysis of the film can be found in: Barbara Wurm, Neuer Mensch – Neues Sehen. Der sowjetische Kulturfilm, PhD (unpublished manuscript) (Berlin, 2018), 279–286.