A State Commemorates Itself

The Staatliche Filmdokumentation at the German Democratic Republic Film Archive

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Barnert, Anne: A State Commemorates Itself: The Staatliche Filmdokumentation at the German Democratic Republic Film Archive. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–13. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14789.

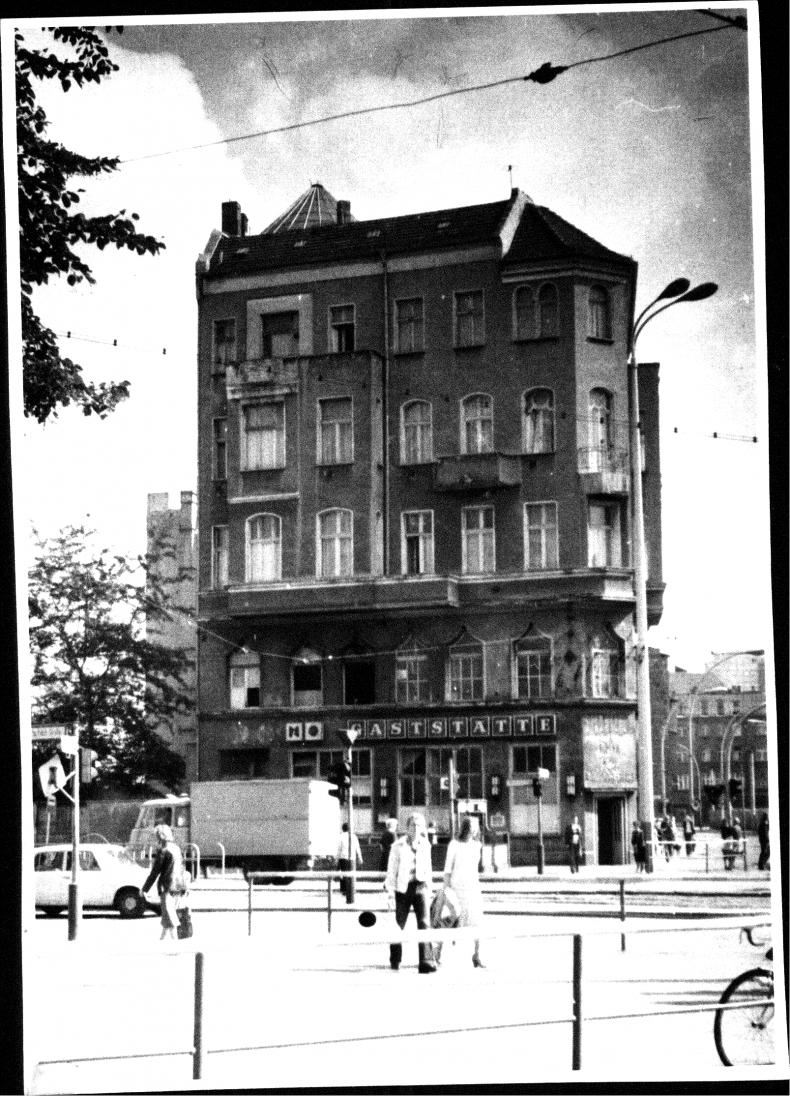

In East Germany in the 1970s and 80s there was a film production group whose one and only express task was to create historical film sources for later generations—a systematic, complete, self-produced documentation of the socialist country of East Germany for the future. Commissioned by the Ministry of Culture, the Staatliche Filmdokumentation (State film documentation, SFD) produced around 300 documentary films between 1970 and 1986. Since their job was to document the state and society for future audiences, they occupied a unique position. The SFD was not integrated into the studio or critical system of the East German cinema; instead, it and its approximately ten employees comprised a department of the State Film Archive. It is unusual, however, for an archive to produce films. Yet, it is precisely because these films were made by this department that they can be described as 'film documents'.

SFD films were considered historical “foundation and source material.”1 As such, they were not intended for the general public in the German Democratic Republic (GDR). They were never premiered, never had audiences. As soon as they were made, they were archived and became inaccessible. At least 30 years were supposed to pass before they would be made available. Other sources mention periods of 50 or even 100 years between production and planned reception. Most of these time periods, however, were vaguely defined, so that it became obvious that these films were meant to disappear, to be forgotten for the time being. And, in fact, the SFD remains almost completely unknown to this day. In 2012/3 many of these films were restored, digitalized, and made accessible in a cooperative project between the Institut für Zeitgeschichte (Institute of Contemporary History, Berlin) and the Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv (the Federal Archive’s Film Archive), with support from the Bundesstiftung zur Aufarbeitung der SED-Diktatur (Federal Foundation for Reassessing the Dictatorship of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany).2 Now that these films can be seen and used, they are able at last to fulfill the purpose for which they were intended.

First of all, the history and ideas behind this film production group should be examined. In doing so, the eastern and western European traditions of “objectively” communicating history through the medium of film will be described. Considering the unusual context in which they were made, that is, by an archival department—the next question that arises is: How did the attempt to give an archive the responsibility for almost the entire process of filming historical documentaries influence the depiction of history in film? SFD films are not documents of history in the generally accepted sense that all films are. What is special about them is that they were made in the archive, systematically and exclusively for this purpose. The process wove together what are actually two separate functions of collective memory—for the tasks of the institutional archive are to collect, evaluate, store, and maintain information, yet the East German State Film Archive attempted to appropriate the creative side of memory by making its own films.

When the SFD was founded in 1970 the Ministry of Culture commissioned it to film in 16mm black-and-white—an unusual format in East Germany at the time. Their assignments covered several types of documentation: non-fiction films about long-term developments and processes in the GDR, as well as documentary films about individuals or social milieus. The fourth type is the most controversial, because these films were supposed to cover undesirable or even taboo themes in the GDR. Two examples of this are the films BERLIN-MILIEU. ACKERSTRASSE (D 1973) which shows fortifications along the Berlin Wall in meticulous detail, and VOLKSPOLIZEI/1985 / THE PEOPLE'S POLICE/1985 (D 1985) which shows the method of operation and self-conception of the police in East Germany.

Since the themes of these films were labeled “secret for the time being,” it was expected that it would be possible to release them later, under different political conditions. Only the SFD was privileged to make this fourth type of documentary film. Here, the department was allowed to do something that was forbidden to other filmmakers. At its best, the GDR documentary film (especially the ones from the state-operated DEFA Studios) is characterized by its method of close, participatory observation.3 In terms of its socio-political functions, however, it was also an instrument for staging interventions in existing reality. In this sense, films available to the public in the cinema or through television systematically produced blind spots in their presentations of East German society. That they sacrificed some of their function as accurate historical sources was an accepted, even intended, part of cultural policy. This gives the productions of the SFD a corrective function. According to one of the department’s internal descriptions, they were supposed to “fill in the gaps” in the film archive that were created by censorship. Thus, their “additions” to cinema and television productions were supposed to enable the state to complete its documentation of itself at a later date.

Due to its unusual mandate, the SFD’s relationships to the state and the party were complicated and difficult. The socialist party began intervening in 1972. The process of making a final decision about the SFD languished for so many years in the party’s Central Committee that the whole matter was eventually dropped. This is what led to the department’s unresolved problem: without any firm support from the party, the authorities overseeing the SFD—the Central Office for Film at the Ministry of Culture—did not believe they were in a position to take on the responsibility for this politically risky experiment in film. As a result, the SFD remained in permanent limbo, which hindered investment, made it difficult to get film permits and access to information, and obstructed cooperative projects with other film producers. For the SFD, this meant that filling in the gaps in East German film production could not be achieved “with certainty,” but “only probably.”4 Their film documents dealt with a state that wanted systematic, comprehensive documentation, but contradictorily refused access to the information needed for it, with only a few exceptions. Thus, one of the important hallmarks of the SFD’s documentation of East Germany is that its portrayal of what was characteristic and “typical” of this country was based on “conjecture.” Today, SFD film documents are valuable historical sources, because—despite the party’s sketchy informational policies—it is possible to perceive what was obviously lacking in the rest of the country’s media. SFD films reacted to the incompleteness of East Germany’s representation of itself in the media, supplementing it with what was mainly intuitive, everyday knowledge. Research here could find opportunities to connect to concepts of “implicit knowledge,”5 which, unlike explicit knowledge, encompasses what cannot be spoken, what has been forgotten, what is no longer conceivable, or what has yet to be conceived.

Originally, the SFD was founded for very pragmatic reasons: there were concrete problems with East German filmmakers who had to deal with censorship, so it seemed urgently necessary to have comprehensive state documentation “for archival purposes.” An earlier form of the department, called the Filmarchiv für Regierungsaufnahmen (Film archive for government recordings) existed by 1949 at the VEB DEFA Studio für Wochenschau und Dokumentarfilme (VEB DEFA studio for weekly news and documentary films). By this time, experience had shown that censorship criteria were erratic, that even if a taboo managed to survive, corresponding images of it were already irretrievably missing. By the end of the 1950s the word from the DEFA documentary film studio was that the increasingly large amount of material missing from films was becoming a grave obstacle to the production of future compilations. Particularly considering the international success of films such as DU UND MANCHER KAMERAD / YOU AND MANY A COMRADE (D 1956) and DEN BLODIGA TIDEN / MEIN KAMPF (SWE / D 1960), which were based on materials from the archives of the GDR’s State Film Archive, it would not have been right to allow the East German documentary film in general to lose its cogency and influential power.

Several times during the 1960s the DDR-Filmarchiv (GDR film archive) also proposed that a state documentary film department be formed. Herbert Volkmann, head of the State Film Archive from 1958 to 1968, was an early proponent of the idea and he worked on furthering it between 1960 and 1962. Preparations for a state documentary film office began at the GDR’s State Film Archive in 1968/9. Ultimately, the SFD was founded as part of a different context with ambitions far beyond the idea of collecting materials for East German compilation films. The late 1960s was marked by a general sense of scientific euphoria. Making documentary films for a later time period seemed to be an essential, important task, because it appeared that the world was on the threshold of a new audio-visual age in which scientific film sources would be necessary. There were also international documentary movements in literature, theater, and film, in addition to science. The State Film Archive began a years-long period of rethinking the documentary film in the context of a new genre. According to the main idea, documentary films were historical sources, and therefore ought to shed anything and everything that had to do with authorship and entertainment. This particular notion of subordinating form to the freedom of future viewers to shape and interpret a film according to their own lights linked the SFD to international role models. In terms of cultural politics, the Soviet Kino-Letopis documentary cinema was crucial. Kino-Letopis (meaning “chronicles” or “annals”) had been producing documentaries on the history and formation of the Soviet Union since the late 1930s at Moscow’s Central Studio for Documentary Films. Here, the SFD adapted the Kino-Letopis idea of focusing on the needs of future film producers, who would require diverse film materials that could be used in many different ways.

Another part of this concept of ideological science and archiving was based on the Filmarchiv der Persönlichkeiten (Film archive of personalities, 1942–4) at the Reichsfilmarchiv (the Third Reich’s film archive).6 These films, which went into production shortly after Kino-Letopis began, were also sources for the founding of the SFD. A series of documentaries on factual topics and people, with scientific, future-oriented ambitions, began production in the early 1940s under the leadership of Gerhard Jeschke. Here, too, the archive was intended to be a consciously produced historical source that would create and shape the visual memories of an entire state for the future. Personal documents from the Filmarchiv der Persönlichkeiten contain biographical statements given by researchers, inventors, combat and fighter pilots, car and airplane designers, writers, artists, doctors, a number of military personnel, race theoreticians, etc.7 Jeschke’s work method was extremely static: the camera barely changed position over the duration of the interview, and interruptions occurred only when it was technically necessary to change rolls of film. Later, the SFD took up this way of dealing with interview situations. It was part of the early SFD’s agenda to give interviewees the opportunity to talk almost uninterruptedly about self-selected topics in their lives. The SFD hoped that this process would result in “deliberate coincidences.”8 The main idea behind this was that the longer subjects talked about their recollections, the more relaxed the phrases and stereotypes would become. Here, we can already see the central idea behind the SFD’s empirically motivated methods: it is the expectation that, given enough time and space, the “essence” of the present would be inscribed, as it were, in the filmed retrospection.

While the Soviet Kino-Letopis cinema offered a guarantee for the cultural-political “correctness” of an East German state documentary film, there was another strand of tradition that was very influential, albeit less prominent. For the specific, contextual, aesthetic concept of their films the SFD tended to look to western models. Here, the Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film (Institute for the scientific film, IWF) in Göttingen was a significant source. Under the guidance of the historian Fritz Terveen, the institute had been producing historical documentary films since 1956. Here, the agenda was to produce institutionally anchored, historical film material under the auspices of “science,” in close cooperation with the Göttingen scholars working with Percy Ernst Schramm. Their debates about the value of these films as historical sources also had an effect on the GDR film archive. In particular, Terveen’s strict distinction between “scientific” and artistic documentaries influenced the SFD. An obvious sign of this influence was that the SFD did not adopt the usual East German term, Filmbericht (film report), nor did they turn to the Soviet term for “film chronicle.” Instead, it employed the word Filmdokument (film document), which was the term used in West Germany for films consciously produced as historical sources. This decision was a clear rejection of anything that might be considered narrative or interpretive, and indicated the department’s conscious utilization of the academic and archival.

In this concept of film as historical source, the less recognizable the artistic subject is, the more the source increases in value: it is not the hand of the director that is at work here, but the hand of the editor. These were not meant to be documentary films, but film documents. In this sense, the SFD did not want to regard its films as works of art, nor were they solely historical documents. Rather, they were, first and foremost, archival material, "candid primary sources.”9 This slightly odd practice of specifically designating the film document a "candid primary source” actually implies its potential opposite—the “staged primary source.”10 And, in fact, in the context of the GDR, it was taken for granted that reality and truth were to be seen as things that could be staged. Out of the many phenomena and manifestations, it was considered necessary to emphasize the ones that could be considered the heralds of the country’s anticipated historical progress. Not only did this legitimize the historical/ philosophical staging as trustworthy, true, and real, it also made it practically necessary. The SFD thus postponed the necessity of presenting the “party’s” perspective: only later would filmmakers, scientists, or educators create unified narratives or interpretations out of SFD recordings. This made it possible for the SFD to avoid the otherwise indispensible process of evaluating the film material for political content—just as long as nothing disturbed the fundamental balance of power.

The “artlessness” that the SFD derived from their role models resulted in empirical work methods. This can be seen in particular in the SFD’s first two phases of production. The period in which the department was founded and built up under the directorship of Bernhard Musall ended in 1970/1, and in 1972, another phase involving an independent production program began. During this phase of Universale Dokumentation (universal documentation), which lasted until 1977, nearly everything was a potential theme for the long, historical documents with little structure that were produced under the auspices of Klaus-Detlef Bausdorf. There were lengthy historical film series about thematic complexes such as the Spanienkämpfer (those who fought in Spain’s civil war); speakers included scientists such as the Nobel Prize winner Gustav Hertz, and politicians such as the infamous former minister of justice, Hilde Benjamin. The films also featured artists—the director Friedo Solter or the composer Joachim Werzlau, for example—at work or going about their everyday lives. In this phase, the prevailing concept of universal documentation also formed the basis for the endless interviews discussed above.

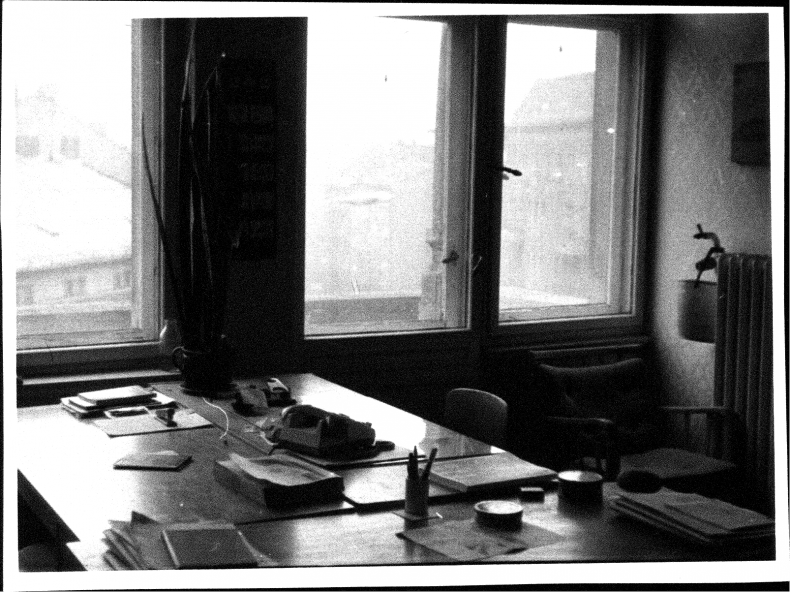

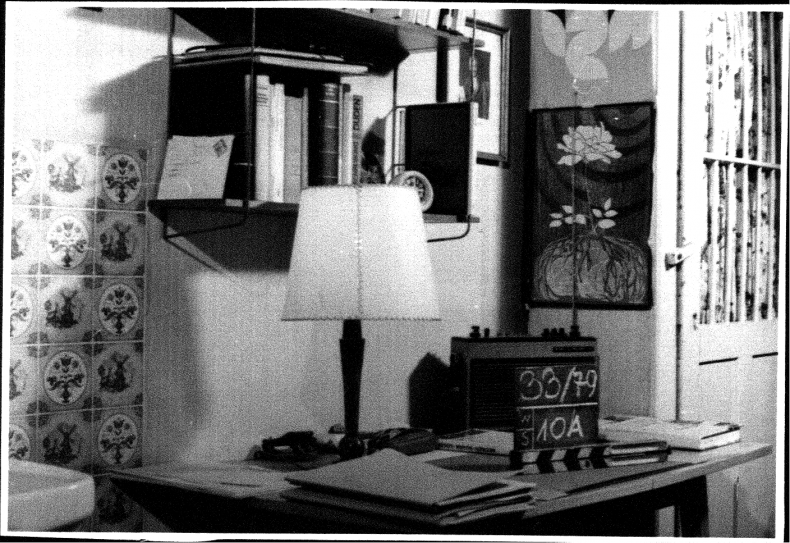

When the universal concept faltered, a second phase of production known as the Berlin-Totale, which concentrated on the capital, occurred between 1978 and 1980. The SFD’s new director, Karl-Heinz Wegner, interpreted the empirical method as working on a “mosaic.” The plan was to film so that many smaller groups of subjects would fit together to form a variable, overall picture.11 The following are examples of this “building block” approach: BERLIN-TOTALE III. LEBENS- UND WOHNVERHÄLTNISSE 5. WOHNKULTUR A) INGENIEURS-WOHNUNG (Berlin Overall III: Conditions of Life 5, Domestic Culture, a] Engineer’s Home, Gertraude Kühn, 1978), to which belong the subcategories:

B) ARBEITER-WOHNUNG I (Worker’s Home I),

C) DOZENTEN-WOHNUNG (Teacher’s Home),

D) RENTNER-WOHNUNG (Pensioner’s Home),

E) ARBEITER-WOHNUNG II (Worker’s Home II),

G) ANGESTELLTEN-WOHNUNG (White-collar Worker’s Home), and

F) STUDENTEN-WOHNUNG (Student’s Home).12

In accordance with the notion of the systematic, continuing series the empirical gaze splintered almost endlessly during the making of the Berlin-Totale films. The expectation was that this slice of Berlin life would be able to fully represent the GDR as a whole, “without any gaps.”

For the SFD, the state film archives functioned as a protective space. As the state’s only film production group, it was also permitted to cover themes that were taboo in East Germany, for “archival purposes.” In addition the department had the privilege of not having to evaluate the aesthetic or formal value of the film material. Both of these things were allowed, though, because the SFD was required to keep its films out of the public eye, so that they had no immediate, direct effect upon the public. The productions had the status of banned films. Despite the archival context, the SFD’s basic conflict was always that it was expected to produce factual, neutral, informative source material on the one hand, while on the other, effective propaganda material was also required. This inconsistency contributed to its unclear status, as well as to its problems. However, once the SFD had been established as a department of an archive, institutional logic had its own effect on the SFD: the archival context strengthened the traditional scientific strand and weakened the propaganda aspect. There was also an opportunity to employ a methodical concept in which history was not related via subjects, but empirically and systematically depicted. From 1972 to 1977 the SFD’s universal system tried to realize this in its depictions of the GDR, while the special system employed in Berlin-Totale attempted it from 1978 to 1980. Both phases shared a common goal: thoroughness.

Ultimately, the 1980s brought about a crisis in the notion of a positivist belief in science. In a third and final conceptual phase, the SFD began moving away from the archival framework. From 1981 to 1985 the documentation phase was known as Sozialistische Lebensweisen (socialist ways of life). Under the leadership of Peter Glass, the focus was on individual observations thought to be characteristic of the GDR. Gradually, the fragmented, empirical approach was abandoned. It had been based on the assumption that the mass of information gained would one day produce an objective, overall picture of East Germany that had been systematically worked out, without the need for editors to intervene in the material, either interpretatively or judgmentally. By the early 1980s, however, the positive future, which one had previously assumed could be described by science, had become more uncertain.13 Its ideological content jolted awareness. The political, social, and economic crises in East Germany accelerated this erosion of belief in science and progress. At the SFD this manifested in a fundamental change of concept, among other things, with the department turning to the artistically condensed film. A process of “writing history through the means of film”14 would from then on actually be able to “write history,” and not just collect information.

At the same time, this new, individual, subjective direction in the film document’s aesthetic concept meant the end of the SFD. In the spring of 1983 the department was accused of not adhering to the agreed limitations, of making “real films” and not film documents. The problem with “real films,” though, was that they were no longer gathering information for the future, but were instead artistically made films aiming for immediate efficacy. Examples of this are the productions DAS HAUS/ 1984 / THE HOUSE/1984 (D 1984) and VOLKSPOLIZEI/ 1985. However, the SFD had not received permission to make such films. From 1983/4 onward it lost more and more political support, which manifested in a massive deficiency on all levels of production. Finally, in early 1985, it faced the open and grave accusation of undermining the “leading role of the party.”15 Just a little while later, in autumn 1985, it was enjoined from further operations, and by the end of 1986 the SFD had been completely dismantled. Thus, a unique experiment in the German Democratic Republic came to an end.

The idea of consciously making historical documents that can be used in the production of future films is still influential in today’s documentary films. In 2011 Thomas Heise made DIE LAGE / THE SITUATION (D 2012), his “third SFD film” after DAS HAUS/ 1984 and VOLKSPOLIZEI/ 1985. Made without much money or preproduction, “for an audience ten years from now,” as Heise says, this film will also only be seen and understood properly after the passage of time.16 The assumption is that there will be a change in conditions that will occur if the film disappears for a while into an archive: as all of the specific knowledge about contexts, media images, and the opinions and ideas associated with them are forgotten, time will peel away all extraneous information and judgments. The expectation is that when these things are finally forgotten, then the structures of habit, communication, or power will at last be visible. The attitude toward documentation here no longer calls for a scientific agenda, as did the SFD. Rather, it is characterized by its rejection of immediate effect and influence.

How does the “archival intention” affect the way that history is depicted in film? At the start, it was mentioned that the GDR Film Archive tried to use the SFD to appropriate the creative side of memory that is actually alien to the archive. If, however, the artistic recollection also includes other possible histories and processes of history, then the archive does not simply turn it into its antithesis, as if it were a purely mechanically produced memory. In the case of the SFD, the productive, creative parts of remembering were translated to suit archival conditions. This means that the many contradictory constructions, associations, and deconstructions of history outside of the archive evolved into a process inside the institution, which although regulated, was nevertheless productive when it came to filling in gaps and rounding out systems. What is creative about East Germany’s process of commemorating itself comes to the fore particularly when the logic of the archive is crossed with an aspect of self-irritation; when gaps cannot be closed, when systems are in danger of becoming lost in endlessness, when minimal editing, sound, and a still camera suddenly produce filmic effects that bring new meanings to the films. Thus, it is ultimately left up to the audience to decide whether or not it encounters “history” in the films produced by the SFD.

- 1The films are characterized as “foundation and source material” throughout all of the surviving SFD documents, above all in those establishing the group’s concept of itself.

- 2The results of this project were initially presented at the colloquium Offene Geheimnisse. Die Staatliche Filmdokumentation des DDR-Filmarchivs (1970–1986), Institut für Zeitgeschichte (Berlin), November 14–15, 2013. See Anne Barnert, ed., Filme für die Zukunft: Die Staatliche Filmdokumentation am Filmarchiv der DDR (Berlin 2015). See also Günter Jordan, Film in der DDR: Daten, Fakten, Strukturen (Potsdam 2009), 203–205 (entry: Filmdokumentation); Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, ed., Filmobibliografischer Jahresbericht (Berlin 1973–86); as well as the following contemporary reports from that time: Thomas Heise, “Archäologie hat mit Graben zu tun,” in Thomas Heise: Material, booklet for the DVD (Munich 2011); Thomas Grimm, “Verrat der Quellen: Die Staatliche Filmdokumentation,” in Schwarzweiß und Farbe: DEFA-Dokumentarfilme 1946–92, eds. Günter Jordan and Ralf Schenk, (Berlin 2000), 356–363; Thomas Grimm, “Nischenlogik? Oder: meine unterschiedlichen Erfahrungen als freier Filmemacher mit den Medien der DDR,” in Unsere Medien – unsere Republik 2: Deutsche Selbst- und Fremdbilder in den Medien von BRD und DDR: Part 9, ed. Adolf-Grimme-Institut (Marl 1994), 48–51.

- 3See Klaus Stanjek, ed., Die Babelsberger Schule des Dokumentarfilms (Berlin 2012).

- 4According to Karl-Heinz Wegner, head of the SFD from 1978 to 1980, in a concurrent analysis of SFD productions up to that time. Only shortly afterward it had to be re-edited; major passages were cut, including the quote above. Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/583: Arbeitsanalyse der Staatlichen Filmdokumentation (SFD): Probleme, Erfahrungen, Erkenntnisse und Schlussfolgerungen (November 1, 1978), 10.

- 5See Jens Loenhoff, ed., Implizites Wissen: Epistemologische und handlungstheoretische Perspektiven (Weilerswist 2012).

- 6For more on this, as well as on the significance of the Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film (Institute for the scientific film, or IWF, Göttingen) for the SFD, see Rolf Aurich, “Historische Quellen produzieren: Eine deutsche Filmtradition,” in Filme für die Zukunft: Die Staatliche Filmdokumentation am Filmarchiv der DDR, ed. Anne Barnert (Berlin 2015).

- 7See Marianne Schulz, “Das Filmarchiv der Persönlichkeiten im Staatlichen Filmarchiv der DDR: Auswertung und Erschliessung eines ungewöhnlichen Filmbestandes faschistischer Provenienz” [unpublished manuscript, final thesis, Fachschule für Archivwesen] (Potsdam 1980).

- 8Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/582: Staatliche Filmdokumentation: Jahresbericht 1973 [January 1974], 3.

- 9Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/585: Zur inhaltlichen Aufgabenstellung der SFD und ihrem Dokumentationsprofil (June 16, 1982), 2.

- 10Basically, the work of dividing documents into primary and secondary sources, traditional sources, or remaining sources could only have been a task for archivists, not the authors of the films. See Eckart Henning, “Einleitung,” in Die archivalischen Quellen: Mit einer Einführung in die historischen Hilfswissenschaften, eds. Friedrich Beck and Eckart Henning (Cologne 2003), 1–6.

- 11Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/737: Diskussionsgrundlage: Konzeption für ein Film-Dokument BERLIN 1978 (November 7, 1977), 1, 10.

- 12The following systematic films were made in 1978: BERLIN-TOTALE III. LEBENS- UND WOHNVERHÄLTNISSE 5. WOHNKULTUR B) ARBEITER-WOHNUNG (I); ... C) DOZENTEN-WOHNUNG; ... D) RENTNER-WOHNUNG (directed by Gertraude Kühn). From 1980 and 1979: ... G) ANGESTELLTEN-WOHNUNG and ... F) STUDENTEN-WOHNUNG (directed by Monika Reck). From 1979: ... E) ARBEITER-WOHNUNG (II) (directed by Gerd Barz).

- 13See Aleida Assmann, Ist die Zeit aus den Fugen? Aufstieg und Fall des Zeitregimes der Moderne (Munich 2013).

- 14The phrase "Geschichtsschreibung mit filmischen Mitteln" (writing history through the means of film) can be found in a petition from the SFD master editor Gisela Tammert to Konrad Naumann, first secretary of the district administration of the Berlin SED, Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/120 (October 15, 1985), 2.

- 15Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/120: [untitled document, in which Wolfgang Klaue, director of the archive from 1969 to 1990, reacts to this accusation] (June 17, 1985), 4.

- 16From the author’s conversation with Thomas Heise on August 30, 2013.

Assmann, Aleida. Ist die Zeit aus den Fugen? Aufstieg und Fall des Zeitregimes der Moderne. Munich 2013.

Aurich, Rolf. “Historische Quellen produzieren: Eine deutsche Filmtradition.” In Filme für die Zukunft: Die Staatliche Filmdokumentation am Filmarchiv der DDR, edited by Anne Barnert. Berlin 2015.

Barnert, Anne, ed. Filme für die Zukunft: Die Staatliche Filmdokumentation am Filmarchiv der DDR. Berlin 2015.

Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/120: untitled document. June 17, 1985.

Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/582: Staatliche Filmdokumentation: Jahresbericht 1973. January 1974.

Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/585: Zur inhaltlichen Aufgabenstellung der SFD und ihrem Dokumentationsprofil. June 16, 1982.

Bundesarchiv Berlin, DR 140/737: Diskussionsgrundlage: Konzeption für ein Film-Dokument BERLIN 1978. November 7, 1977.

Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, ed. Filmobibliografischer Jahresbericht. Berlin 1973–86.

Grimm, Thomas. “Nischenlogik? Oder: meine unterschiedlichen Erfahrungen als freier Filmemacher mit den Medien der DDR.” In Unsere Medien – unsere Republik 2: Deutsche Selbst- und Fremdbilder in den Medien von BRD und DDR: Part 9, edited by Adolf-Grimme-Institut. Marl 1994.

Grimm, Thomas. “Verrat der Quellen: Die Staatliche Filmdokumentation.” In Schwarzweiß und Farbe: DEFA-Dokumentarfilme 1946–92, edited by Günter Jordan and Ralf Schenk. Berlin 2000.

Heise, Thomas. “Archäologie hat mit Graben zu tun.” In Thomas Heise: Material, booklet for the DVD. Munich 2011.

Henning, Eckart. “Einleitung.” In Die archivalischen Quellen: Mit einer Einführung in die historischen Hilfswissenschaften, edited by Friedrich Beck and Eckart Henning. Cologne 2003.

Jordan, Günter. Film in der DDR: Daten, Fakten, Strukturen. Potsdam 2009.

Loenhoff, Jens, ed. Implizites Wissen: Epistemologische und handlungstheoretische Perspektiven. Weilerswist 2012.

Schulz, Marianne. Das Filmarchiv der Persönlichkeiten im Staatlichen Filmarchiv der DDR: Auswertung und Erschliessung eines ungewöhnlichen Filmbestandes faschistischer Provenienz [unpublished manuscript, final thesis, Fachschule für Archivwesen]. Potsdam 1980.

Stanjek, Klaus, ed. Die Babelsberger Schule des Dokumentarfilms. Berlin 2012.