Trapped in Amber

The New Materialities of Memory

Table of Contents

Liberated on Film

Mexican Public Health History through Film

Reel Life

Film as Instrument of Social Enquiry

Visibility and Torture

Trapped in Amber

Be Part of History

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Elsaesser, Thomas: Trapped in Amber: The New Materialities of Memory. In: Research in Film and History. Research, Debates and Projects 2.0 (2019), No. 2, pp. 1–15. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26881/pan.2018.19.10.

The New York art critic Hal Foster once observed, “We still find it difficult to think about history as a narrative of survivals and repetition,” yet we increasingly have to come to terms with a “continual process of protension and retension, a complex relay of anticipated futures and reconstructed pasts.”1 Foster does not specifically mention film and photography, with their uniquely haunting time-warp effects on our conception of history as a linear sequence, whereby effects are connected to causes. But he does clearly allude to the relays of countervailing temporalities that the prevailing ubiquity of photographic media has engendered. Cinema, after all, defies time through what I would like to call its uncanny ontology: moving images always docu ment what is not yet dead but also not quite alive, simulacra of life at its most vivid. This unresolvable tension between rewind and replay, between presence and absence, between life preserved and the kingdom of shadows, has profoundly altered our understanding of what history is, just as the same tension between original and copy, between reconstruction and repli ca, dominates our thinking today about the status of art and historical artifacts, in our post-auratic era that nonetheless craves authenticity and “keeping things real.”

Damien Hirst’s controversial exhibition “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable,”2 which was shown in Venice in 2017, is both an appropriately baroque (and bombastic) treatment of simulacra and related topics, and a slyly mischievous middle finger cocked at the art world and at academia for wrestling so earnestly with questions such as the ethics of restoration and preservation, how to tell appropriation from plagiarism, how to distinguish reproduction from copy, replica from fake, and what the emotional difference is between the mass-produced souvenir in the gift shop and the priceless collector’s item: all categories that, as Walter Benjamin already recognized, became highly problematic if not obsolete in the age of reproducibility, of which he saw photography and film as the unmistakable harbingers and inevitable disruptions. The implied suspension of epistemic boundaries between different orders of reality and reference has only become more explicit and self-evident with the advent of digital imaging and 3-D printing. Yet the questions this poses about truth and verification, visibility and evidence, have lost none of their slippery intractability for philosophers, art historians, and, indeed, film scholars.

In what follows, I may be doing no more than, yet again, demonstrating this frustrating intractability, as I attempt to trace the impact moving pictures have had on history and memory, as we make sense of obsolescence and nostalgia, document and proof, testimony and traumatic forgetting. I want to start with an observation, or claim: the coexistence in the twentieth century of cinema and of nineteenth-century historicist consciousness produced two unresolved, interrelated crises. First, it made the spatialization of time that was already well underway with Einstein’s relativity theory, as opposed to Bergson’s notion of time as duration, into a truism; second, it began to replace our notion of linear causality with terms such as contingency, chance, chaos theory, and stochastic series.

Taken together, the spatial turn and the crisis in causation challenged the hegemony of history – which the nineteenth century had “discovered” as the relentless force of destiny (Hegel’s world spirit) or celebrated as the engine driving human progress (Marx). More specifically, spatial time and contingent nonlinearity deconstruc ted history into competing but also complementary centers of more entropic forms of energy, identified with the archive and archaeology as the “materializations of memory.” But there is also associative memory and dissociative trauma – what we might call the “immaterializations of memory.”

Given the topic of materiality and memory, I want to approach history as spatialized time under the heading of cultural memory, and history as archive under the heading of historical topographies, suggesting that a concept such as obsolescence combines, or maybe even reconciles, the locatedness of topography with the new materialities of memory that have emerged in response to the apparent immateriality of digital images.

Cultural memory has been extensively studied by Aleida Assmann,3 but as a particular spatialization of time it is now most often associated with Pierre Nora and his idea of lieux de mémoire, that is, sites of memory.4 His seven-volume Les Lieux de Mémoire (1984–1992), about the sites of memory in France, helped to redefine Maurice Halbwachs’s notion of collective memory5 by specifying public memory’s practices in much more topographic and regional detail, as well as exploring its various discursive manifestations. Nora not only showed how cultural memory intersects with the public lives of collectives, but also how it materializes time as it shapes individuals’ sense of origins and “roots” across shared symbols. “A lieu de mémoire,” Nora says, “is any significant entity, whether material or non-material in nature, which by virtue of human will or by the work of time has become a symbolic element of the memorial heritage of any community.”6

These lieux de mémoire7 famously include not just what we would expect to find, that is, the built spaces of collective experiences, such as monuments, museums, cathedrals, cemeteries, statues, and memorial sites, but also extend to practices such as public holidays, festivals, celebrations, and rituals, and even to proverbs, clichés, and common turns of phrase that have been passed on from one generation to the next, and through which people communi cate with each other their sense of belonging, or simply their longing for belonging.

Contrary to Nora’s intentions and declared aim, the term lieu de mémoire has been appropriated in sometimes controversial contexts, making it a rallying cry for a new kind of populist nationalism, whereas he may have intended it as a warning. Instead of the generally positive connotations the term has acquired, Nora was more cautious and critical, seeing in lieux de mémoire – and especially the memory discourses that came flooding in beginning in the 1970s and especially since the fall of Communism – a potential takeover bid and threat to the craft of the practicing historian.

But the notion has also inspired writers interested in the memory function of modern commodities and communication technologies. Those fascinated by the affective power of the com mon symbols of consumer society, from classic Coca-Cola bottles to bell-bottom pants, from 1950s pop songs to taglines from cult movies such as TAXI DRIVER (US 1976) and CASABLANCA (US 1942), have found in lieux de mémoire a respectable catch phrase and useful antidote with which to counter the disparaging associations of “nostalgia,” “obsolescence,” “kitsch,” or “retro fashion.” Being located in time, while also marking the passage of time, a lieu de mémoire can become the embodied form of a battle against forgetting, in the very medium of forgetting, namely ephemerality and fashion, popular culture and mass production, accumulation and waste.

Nora’s notion of cultural memory as lieux de mémoire allows me to introduce my second critical term, namely historical topographies, which has in common with cultural memory the language of sedimentation and layering, of the past retrieved, recalled, recovered, and recollected, as the salvage of secrets, of lost opportunities, and of sunken treasures. This may seem paradoxical in the case of cinema, now more often I interpreted as an art of touch and transparency, of surface and skin. But consider James Cameron’s TITANIC (US 1997) and Damien Hirst’s “Treasures from the Wreck of the Unbelievable”: their (film and exhibition) blockbuster spectacles dramatize the virtual presence of the past with metaphors that emphasize the materiality of time, whose visual evidence is shells and crustaceans. When not recovered from the ocean floor, buried in sand, or encrusted with barnacles, it is as fossils come to life, in the shape of embalmed mummies, conserved in peat like bog people, trapped in amber, or kept intact in permafrost, that we experience history’s imprint and trace, combined with the preserved materiality and site-specific presence of the object itself.

We would therefore simply be following in the footsteps of André Bazin, who coined the term “change mummified”8 and who paid as much attention to the cinema as trace as he did to cinema as window – if we were to argue that barnacles, bogs, and glaciers are the natural “media” of historical topographies, of which photography and film would be the cultural extensions, in contrast to the usual genealogies of celluloid that start with wax tablets, clay cylinders, scrolls, and paper: symbolic notations rather than the preserved imprint of the objects themselves.

To claim that the different tenses and temporal registers of visual media (for instance, what Roland Barthes called “the future anterior” of photography)9 have affinities with the archaeological media for “freezing” time, such as amber, peat, and ice, is to align cinema more plausibly with the material immateriality of Pierre Nora’s lieux de mémoire. But it is also a reminder of the oxymorons hidden in terms such as “cultural memory” and “historical topographies,” when applied to moving images. The idea of cinema as an archaeo-topological medium – one way to come to terms with its uncanny ontology – not only revives debates about stillness and movement and movement stilled, but also risks conflating categories that used to be separate and even opposed to each other, such as “memory” and “history.” The same goes for the opposition of “culture” and “nature,” which the radical egalitarianism of the camera has also leveled; just think of Jean Epstein’s definition of photogénie: “I would describe as photogenic any aspect of things, beings, or souls whose moral character is enhanced by filmic reproduction.”10 It is important to note the equivalence that Epstein draws between “things, beings, or souls.” Even more clearly, the nature/culture divide once considered fundamental has been rendered all but obsolete due to the expanded scale and impact of human activity on the planet. The oxymoronic element in a term like historical topographies, which mixes the man-made and the geological, can draw attention to these different kinds and timescales of agency, and therefore reflect the recognition that humans are henceforth in charge of – and hence responsible for – nature as well as culture, which inaugurates the macro-historical time of the Anthropocene (identified by the massive statistical increase over the last hundred years of such, more or less randomly chosen, indices as CO2 concentration, water use, species extinction, number of motor vehicles, loss of forests, paper use, and transborder foreign investments).

But the Anthropocene might well include what Harun Farocki once identified as one of the effects of filmmaking and, in particular, of documentary in the age of surveillance, namely, “cameras circling the globe that make the world superfluous”11 – pointing to a sort of mutually determining loop of creative destruction, where what cameras capture and preserve, they also downgrade to the status of prop or pretext. Such preservation cannot help but destroy what it sets out to rescue, because when the world opens itself up to ubiquitous visibility, people and places risk existing merely in order to end up as images.

Cinema as cultural memory and historical topography could therefore be regarded as a kind of “transitional object,” a comfort blanket that eases our transition from humanism to posthumanism. The uncanny ontology would be the uncanny valley of the “humanist” side of the divide, while what I just called cinema’s archaeo-topological definition looks at the same transition between Holocene and Anthropocene from the heights of algorithmic cinema – each indexing the different relations we now have to the world, following the end of “grand narratives” and other Enlighten ment teleologies of progress, and thus also of history as we commonly understand it.

Being the small change of history and also the ruin of these grand narratives, cinema as cultural memory comprises all kinds of micro- and macro-histories, many of which tend toward “traumatic” narratives; for instance, making the Holocaust the most emblematic (and problematic) of cinema’s historical topographies, as Farocki’s IMAGES OF THE WORLD AND THE INSCRIPTION OF WAR (DE 1988) and Georges Didi-Huberman’s conflict with Claude Lanzmann over four Sonderkommando photos have shown.12

Another effect of the demotion of history, this time less through cinema as cultural memory and more as a consequence of the collapse of the culture/nature divide, is the revival of the belief in all manner of nonhuman agencies, now going by the name not of God or Manifest Destiny, but – to quote Quentin Meillassoux once more – the philosophical “necessity of contingency”13 or technological singularity, pointing in the dystopic direction of a seemingly inevitable biodigital fusion.14

One is reminded of W. G. Sebald’s musings on the latency effects of the bombing raids on German cities in the last months of the Second World War, published in English under the suggestive title On the Natural History of Destruction.15 Sebald’s name, of course, is synonymous with the very idea of cultural memory and historical topographies in contemporary literature, at the interface between writing and photography, the map and the walk, the archive and the archaeological excavation. It will be remembered that Sebald’s Rings of Saturn forged a new compound of nature and history, “exploring places and setting them in time,”16 remapping Norfolk and Suffolk, his own body becoming the medium of elation and fatigue. By walking, as well as by deploying his bookish erudition, Sebald discovered everywhere the memory traces of past histories, broken-off trajectories, and signs of small or momentous human endeavors that may or may not have begun on an abandoned, forgotten, or unrecognizably transformed patch of land.

Sebald is the inspiration behind Memory Maps, a project conducted by the British writer and academic Marina Warner at the University of Essex and the Victoria and Albert Museum. To quote from Warner’s project description:

A new genre of literature has been emerging strongly in recent years. Writers combine fiction, history, traveller’s [sic] tales, autobio graphy, anecdote, aesthetics, antiquarianism, conversation, and memoir. Mapping memories involves listening in to other people’s ghosts as well as your own.17

Warner identifies a number of general concerns which she sees focalized in the memory map, each sedimented and fragile, each persistent and ephemeral: she singles out the concerns with “identity and belonging” and “ecology and stewardship,” both of which “are inter-connected through memory and through the stories we use as compass bearings.”18

A similar but earlier foray into “cultural memory as historical topography” was undertaken by Simon Schama, in his 1995 Landscape and Memory. Schama kept the two sides in focus: how much landscape has shaped human history, and indeed human society, right up to the present, and the inverse, how much of “nature” as we perceive it today – and as poets and painters have celebrated it for the past 500 years – is actually the product of centuries, indeed millennia, of human intervention and the shaping power of farmers, warriors, and civil engineers.19

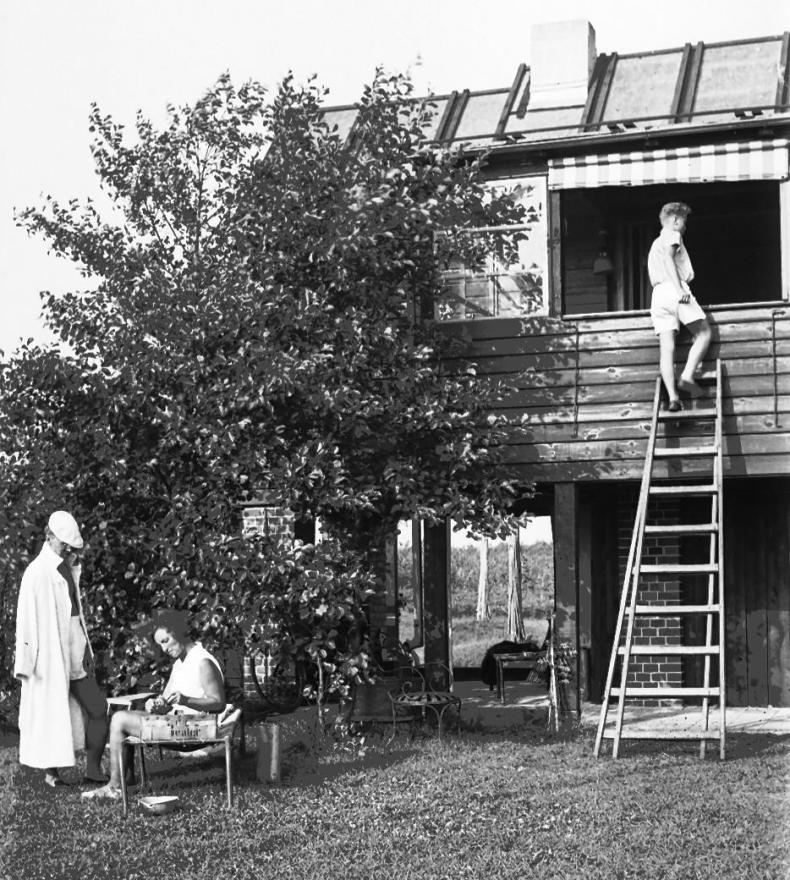

THE SUN ISLAND

On a much smaller scale both temporally and geographically, but partly inspired by Nora, Sebald, and Schama, I tried in my film THE SUN ISLAND (DE 2017) to reconstruct, and in the end also to invent, what might be called the memory map of an “île de mémoire,” based on an actual island located not far from Berlin, where – to quote Marina Warner – “ecology and stewardship” were “interconnected with memory and stories.”20 This particular lieu de mémoire appeared at first glance to be a site of pristine nature, but turned out to have its own scars and traces of lived history. It is a place to which the phrase “natural history of destruction” applies, just as it confirms Simon Schama’s case of a landscape that has shaped the lives of several generations of people. Their relentless work was dedicated to making nature into culture, but in nature’s name, recycling city waste in order to gain land and make it fertile, even as nature unmade and reclaimed this cultural topography once more, thanks to its own relentless work upon human structures, once the humans had been forced to leave the land they had so assiduously cultivated.

In the course of plotting these slow cycles of regenerative destruction, I discovered several other cycles of value creation and value destruction, binding together nature and culture, and – to my surprise – it turned out that the photographs, letters, administrative records, and home movies from which I had to piece together the story of THE SUN ISLAND in fact prolonged this transferal of decay and regeneration; my father’s home movies and my grandmother’s letters gave another twist to the human history/natural history interface when I began to restore decaying film stock and decipher gothic script. Digitizing both the images and the letters added another layer to the value exchange. The gain in legibility entailed a loss in authenticity, but as we shall see it is invariably the inter vention of a new technology that confers added value to an object’s obsolescence.

THE SUN ISLAND as a lieu de mémoire is intimately linked to another historical topography: Berlin, a city that has engendered its own cultural memory, made up of images and music, buildings and ruins, clichés and discoveries, fiction and critical discourse. As almost everyone writing about Berlin notes, it is a very peculiar kind of chronotope.21 Ever since the nineteenth century, Berlin has been a city of multiple temporalities and diverse modalities: virtual and actual, divided and united, created and destroyed, repaired and rebuilt. Just look, for instance, at Potsdamer Platz in 1925, in 1945, and then in 2005. Living in a perpetual mise-en-scène of its own history, a history it both needs and fears, both reinvents and disowns, Berlin is a city of superimpositions and erasures, full of the ghosts and “special effects” that are the legacy of Nazism and Stalinism, obliged to remember totalitarian crimes while still mourning socialist dreams.

Mindful of these peculiar temporalities, some of which only apply to Berlin, my project was eccentric in two distinct ways: first, it situated itself geographically at the very boundary of the city, while nonetheless being unthinkable without it; and second, unlike Berlin, which is reinventing in stone, glass, and steel the memory it has of itself, my island chronotope had to remain a ruin-in-progress. Rather than use the living memory preserved in the movies as the blueprint for its physical restoration, the project was always intended to be imaginary, in the precise sense of treating the images as the primary reality, of which the actual site, the island as it exists when I visited it, was now no more than a “sedi ment” or material residue, however lush and verdant the island vegetation, and however fresh and teeming with fish the waters that surround it.

In other words, the project was the exact opposite of an act of nostalgic recovery and reenactment, and more a way of testing the limits of the evidentiary truth that historical films and photographs now claim for themselves. If images are the tangible record of a physical site, as well as evidence of a moment in time, then old movies, with their now intensely felt materiality, are also a lure and a ruse. They have, for the past century, created and fashioned, fortified but also falsified memory and turned it into our history – from which there is no escape back into mere books or written documents. Quite problematically, as cultural and political artifacts, some film clips have assumed the status of a separate reality, often becoming iconic (think, for instance, of the Zapruder film of the Kennedy assassination, the Rodney King beating, the student protests at Tiananmen Square), that is, more palpably real and authentic than the place and the moment to which they owe their existence. The fact that sometimes they confer a reality of presence to events and places that without the photographic record might never have “existed” – the opposite of what I said about the world existing only to end up as image – this precarious presence gives their preservation (and, by extension, their interpretation) a special, ethical significance.

Marina Warner calls this kind of ethical imperative “stewardship,” and it applies with special force to film, one of the most physically fragile and yet imaginatively powerful archives of such “presence.” It raises further ethical dilemmas, to do with stewardship as a form of trust, nowhere more so than in my particular instance, as some of the materials that I depended upon for THE SUN ISLAND are not in the public domain, but are in every sense “private property”: not only is the island private property – and the present owner might still sue me for trespassing – but the home movies and amateur photographs, which I supplemented by drawing on personal correspondence, love letters, and poems, concern public persons at moments when they were their most intensely private selves.

Yet the realities the letters and movies document also belong to a collective “history,” insofar as these literary and photographic tokens of friendship and rivalry, of courtship and passion, tragedy and trauma, are also the only extant evidence of and testimony to an “experiment in living,” a project of sustainability and of the circular economy that was meant to be emulated, propagated, and made public. In both inspiration and implementation, the island experiment decidedly belongs to the history of Berlin modernism, at the point where one family’s filmic memories have themselves become a historical topography.

From History to Memory and from Memory to Trauma

Notions such as the lieux de mémoire, the memory map, and the chrono tope are symptomatic of the way cultural memory in the form of amateur movies, found footage, and family photographs has become so popular, but also of why its inflection toward the personal and the subjectively felt is such a conspicuous challenge to history. If, traditionally, history takes over from memory precisely at the point where the past is no longer embodied in a living substance, but only accessible through the material traces that an event or a person has left behind, then the emergence of recorded sound and moving images since the beginning of the twentieth century has confronted this conception of history with the conundrum with which I began: namely, that recorded sound and moving images are both more than mere traces and less than full embodiment of past events. They have the power to conjure up living presence, while also remaining mere echoes and shadows of what once was. In the cinema, “the past is “never dead, it’s not even past” (to quote William Faulkner), so how can it become history? Moving pictures, whether fictional or documentary, whether wholes or fragments, are both lost to life and yet survive the death of what they display. Their ghostly presence and afterlife is intimately linked to what we understand by memory today. Indeed, as mentioned, I would go further and claim that historical footage, especially found footage and amateur film, is by its very nature closer to trauma, experienced as a past event that will return, unannounced, with the full force of the lived instant. The sud denness of the encounter with such a past, brought back to life, requires its own kind of “working through” – be it in the form of montage, as in the found footage films of Bruce Conner, Peter Delpeut, Bill Morrison, and Péter Forgács, or be it by way of personal narratives, as in the films of Ross McElwee and Alan Berliner.

These once-marginal avant-garde practices have increasingly moved to the center, occupying – in the form of online video essays or essay films – an increasingly important place in teaching, filmmaking, and installation art. More than a passing trend, it is indicative of yet another coping strategy: for could it be that our tendency to now privilege memory over history, as more authentic and truthful, and to associate memory invariably with trauma, is in fact our way of “working through” not only the many man-made disasters of the twentieth century, but also of coming to terms with the fact that any history of the twentieth century must henceforth dig into the archives of its mechanically and electronically produced sounds and images? Archives that we are only beginning to find the narratives to make sense of, narratives that can speak to the losses and integrate the gaps, but also narratives that manage the often-haphazard accumulation and sheer abundance and diversity of the film materials that have survived and been passed down to us.

If the historians’ working cycle moves from testimony and living memory to History with a capital H, there is another cycle – one that includes these sound and image archives – that moves from history back to collective memory, and from collective memory to individual trauma, that is, memory that displays the symptoms of trauma: the nonlinear persistence of unprocessed experience.

Obsolescence

In the confrontation with the sensory overload of mechanical and electronic images, but also in the face of traumatically disruptive techno logies, the term “obsoles cence” has made an unexpected reappearance as the codeword for the undead state of moving images and other phenomena that refuse to join the natural cycles of decay and renewal.

What is unexpected about this reappearance is that “obsolescence” has not only caught the attention of digital media historians, but also of the art world. In the process, it has significantly changed its meaning, enlarging its semantic and evaluative range. From being a negative term within the technicist discourse of “progress through creative destruction,” it became a critical term in Marxist discourse, when designers and marketers advanced the principle of planned obsolescence, while critics of consumerism in the 1950s, such as Vance Packard, attacked such built-in obsolescence as both wasteful and immoral.22

As both a cover for an all too readily assumed (and consumed) nostalgia for several kinds of pre- or proto-cinematic golden ages, and as an expression of more conflicted ways of coping with the utter presumption of the new, obsolescence might seem at first glance to fetishize the “first machine age” of cinema (i.e. its apparatus side), in a gesture that melds the superiority of hindsight with the secret envy of lost innocence.

However, the meaning of obsolescence has once more shifted: it has entered the realm of the positive, signifying something like heroic resistance to relentless acceleration, to the tyranny of the “new,” just as “glitch” is now the name for resistance to relentless digital perfection. In the process, obsolescence has become the badge of honor of the no longer useful (for capitalism, for profit, for a purpose), which further more associates the obsolete with the “disinterestedness” of the aesthetic impulse itself. Just think of the many obsolete media technologies that now fill our galleries, the way that sculptures of nudes used to people museums a hundred years ago.23

As the cycles of updates and upgrades in the spheres of consumer electronics and software have sped up, obsolescence increasingly connotes or implies the digital as its negative foil. This is also reflected in one of its current definitions:

"Obsolescence is the state of being which occurs when an object, service, or practice is no longer wanted even though it may still be in good working order. Obsolete refers to something that is already disused or discarded, or antiquated. […] A growing industry sector is facing issues where the life cycles of products no longer fit together with life cycles of components. […] However, obsolescence extends beyond electronic components to other items […] obsolescence has been shown to appear for software, and soft resources, such as human skills."24

The last part of the passage is telling, since it spells out the antiquatedness and obsolescence of what are here called “soft resources,” i.e. human skills and, by extension, human beings: a point I shall return to at the end of this article, since it hints at our own anxieties about not being able to keep pace with the accelerated life cycles that machines and gadgets are imposing on humans. As a consequence, obsolescence can also be the rallying point for sustainability and ecological awareness, while nonetheless taking its stand for “object-oriented philosophy” and the new materialism of self-sufficiency of being. Yet this should not make us overlook how, in respect of film and photography, obsolescence can give expression to the grieving and mourning, the denial and disavowal, of what is lost and gone forever, while at the same time nurturing an insane hope, bordering on hubris, that we might be able to bring this embalmed past back to life.

Sarah Polley’s STORIES WE TELL

A good example of both the hope and the hubris, of the dilemmas of how to deal with the images that have come down to us and of the almost inevitable turn to memory as trauma, is the documentary STORIES WE TELL (CA 2012) by the Canadian actor and director Sarah Polley. Polley weaves her very personal and, as it turns out, traumatic narrative around home movies that mainly feature her mother Diane as a vivacious and energetic but also flighty and flirtatious thirty-something, which were taken by her hus band and the father of her four children. Diane died tragically young of cancer, with her youngest child Sarah being the one who most closely followed her mother’s career as an actor. What makes the film symptomatic of the quest for a new materiality of memory is not only that Polley, faced with her father’s home movies of a mother she barely knew, constructs a narrative in the form of a quest and a self-interrogation, in which all the family mem bers, siblings, friends, and colleagues are interviewed and cross-examined, but also something that only gradually emerges: namely, that Polley illus trates many of these reminiscences, anecdotes, and recalled moments with restaged scenes, using actors made up to look like her parents and their friends, who are then filmed with the same equipment that her father had used for the original footage.

What is striking is the way this Super 8 camera, in its precariousness and obsolescence, becomes a talisman and fetish (in the anthropological sense), charged with documenting and uncovering what the actual surviving images so carefully hid and concealed, namely her mother’s extramarital affair, of which Sarah turns out to have been the not altogether welcome love child. It is as if the restaging and faking is best understood as Polley’s own “working through” and “acting out” of the trauma of her paternity, for which the Super 8 camera itself becomes both the instrument of truth and the guarantor of authenticity, in the very act of filming the unfilmed, and thus restoring what is missing in Sarah’s life narrative.

But this desperate act of recovery is only possible or credible because of what I hinted at earlier: we have become so saturated with images that we now assume any event worth being remembered or important enough to enter history must have been captured on camera. Yet this in turn is such a tragic mistake, such a fatal illusion, that only a narrative revolving around family melodrama and personal trauma can rescue its underlying assumptions, by making them provocatively problematic. Here an orphan of the cinema (the found footage of her mother) quite literally begets a narrative about an orphan: Sarah. Having lost her mother, Sarah is suddenly forced to look for her biological father. In other words, the default value of what is “real” has changed, with the obsolete technology retro actively standing in for the historical gap between the 1970s (and amateur filming as an emerging practice) and today (where everyone carries a camera), so that the fake footage both fills and fails to fill this gap. A similar strategy characterizes Polley’s way with words: in order to be truly authentic, her father’s testimony needs to be mediated, and the most inti mate parts of his narrative are filmed in a recording studio, where he reads the lines from a script, and repeats them when Sarah is not satisfied with his delivery. Here, then, “mastering the past” not only involves digitally remastering damaged analogue footage, but also restaging and reenacting the past, now in the idiom of obsolescence.

One reason why this way of “mastering” a family trauma through reenactment that includes fake footage and obsolete technology resonated so strongly with the public may be that it also speaks to the broader trauma we all seem to be caught up in: our obsession with not only revisiting but also rewriting and revising the past, because of our inability to imagine a world different from the one we currently inhabit, making us all orphans – of utopia. As in BACK TO THE FUTURE (US 1985), we seem to have lan ded in a compulsion to repeat, disguised as nostalgia for a “better and more complete past” (since we cannot have a better future), which may even take the form of time travel; but unlike in BACK TO THE FUTURE, our collective return vainly hopes to undo what has already happened, as if to try and make amends for sins we are not even sure we have committed, as in the case of STORIES WE TELL.

The Loop of Belatedness

The fact that obsolescence thus connects both utopia and time travel would confirm the point I started from, namely that we have not only lost our faith in a better future, but also our belief in “learning from history,” which is why we can deconstruct it so easily into memory and topography, into trauma and archive. Obsolescence is therefore also a codeword for “history at a standstill,” to modify Benjamin’s aphorism about the dialectical image.25 But as arrested history, time that is suspended and reversible in its flow, obsoles cence is also the placeholder for renewal and revival, biding its time.

This would be the ground for positing a “poetics of obsolescence,” whose theoretical elaboration can also be traced back to Walter Benjamin and his reflections on the surrealist object.26 Freed from utility and market value, even the industrially made commodity can reveal an unexpected beauty and display a match between form and function that speaks of ideals present as potential even when still unrealized. At the same time, when reclaiming the discarded, preserving the ephemeral, and putting to new use the newly useless, we may indeed be right to feel virtuous: for are we not paying our tribute to ecological sustainability and renewability, even if only in the form of the symbolic act that is art?

At this point it is worth recalling Marshall McLuhan’s tetrad of media effects: “What does the medium enhance and amplify? What does the medium discard and make obsolete? What does the medium reverse or how does it flip when pushed? What does the medium retrieve that had been discarded?”27 With only minor adjustments – for instance, by inverting the direction of McLuhan’s causal arc from old to new, and allowing for the discovery of the new in the old medium, and not only the effects of the new on the old medium – the current interactions between the art world and the cinematic archive are holding all three parts of McLuhan’s tetrad in suspended animation: whether we think of art historian Rosalind Krauss advocating the post-medium condition as the “new medium specificity,”28 whether we take the museum space as the site at the intersection of enhancement and retrieval, or whether we study artists like William Kentridge, pushing the old medium to its extremes in the full awareness of the digital having effected a kind of figure–ground reversal.

Remaining within Benjamin’s frame of reference, we can cite his messianic conception of Jetztzeit or now-time, and say that “the past is always formed in and by the present. It comes into discourse analeptically in relation to a present, but since it is read from the standpoint of the present, it is proleptic as well, in that it forms ‘the time of the now.’”29 This analeptic–proleptic relationship I call the “loop of belated ness,” whereby we retroactively discover the past to have been prescient and prophetic, as seen from the point of view of some special problem or urgent concern in the here and now. Much of our work as film scholars and media historians is, for good or ill, caught in this loop of belatedness, where we retroactively assign or attribute foresight and agency to a moment or a figure from the past that suddenly speaks to us in a special way.

But here’s the rub: if one of the strategic uses of obsolescence is that it can serve both as an aesthetic value and as an ecological virtue, there still remains the fact that, being a term inevitably associated with both capitalism and technology, it implicitly acknowledges that today there can be no art or nature outside capitalism and technology. This would be the term’s political dimension, since the dialectics of (technological) innovation and (capitalist) obsolescence has in some sense become the fate of the contemporary world, keeping us in a loop of our own historical belatedness, whether as Europeans or as a species.

It suggests that obsolescence, as I have been trying to sketch it, is also the recto to the verso of the now definitely lost ideals of progress and enlightenment: through obsolescence we negatively conjure up the ghost of progress past, making it the token or fetish of a future we no longer see other than as the recovery of a past: a past that may be trapped for us – but possibly also trapping us – in the translucent amber of our celluloid heritage.

This leaves us pondering the trade-off I have been suggesting: namely, that one way to salvage history from cinema’s (and not only cinema’s) uncanny ontologies is to open historical thinking up to the archaeo-topographies of cultural memory, and especially to its traumatic remainders and apparently obsolescent values. It gives the past – more and more recalled and present to us only through moving images – the kinds of locatedness and materiality that, far from making the world superfluous, establish for it a new ecology of sustainability. By reestablishing a cycle that is not just a loop, it would ensure for mankind’s many pasts the possibility of fashioning the future, rather than foreclosing it in the posthuman life scenarios of bioalgorithmic or biodigital fusion.30

This essay was first published as Elsaesser, Thomas. "Trapped in Amber: The New Materialities of Memory." Panoptikum 19 (2018): 144–158. https://doi.org/10.26881/pan.2018.19.10

- 1Hal Foster, “What’s Neo about the Neo-Avant-Garde?”, October 74 (Fall 1994): 30.

- 2Reviews of the controversy caused by Damien Hirst’s exhibition can be found at: https://hyperallergic.com/391158/damien-hirst-treasures-from-the-wreck-…

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/damien-hirst-created-fake-documentary…

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/apr/06/damien-hirst-treas…

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2017/apr/16/damien-hirst-treas…. - 3Aleida Assmann, Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012).

- 4Pierre Nora, Les Lieux de Mémoire (Paris: Gallimard, 1984–1992).

- 5Maurice Halbwachs, On Collective Memory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992).

- 6Pierre Nora et al., eds., Realms of Memory (Columbia: Columbia University Press, 1996), xvii.

- 7Pierre Nora, “Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire,” Representations 26 (Spring 1989): 7.

- 8André Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” in Film Quarterly 13, no. 4 (Summer, 1960): 4–9.

- 9Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography (New York: Hill and Wang, 1981), 96.

- 10Quoted in Richard Abel, ed., French Film Theory and Criticism 1907–1929 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988), 314.

- 11Thomas Elsaesser, ed., Harun Farocki — Working on the Sightlines (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004), 189.

- 12Georges Didi-Huberman, Images malgré tout (Paris: Edition Minuit, 2004).

- 13Quentin Meillassoux, After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency (London: Bloomsbury, 2008).

- 14For an account of different kinds of agency, see Andrew Pickering, The Mangle of Practice (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1995).

- 15W. G. Sebald, On the Natural History of Destruction (New York: Random House, 2003).

- 16From http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/m/memory-maps-about-the-project/, paraphrasing W. G. Sebald, The Emigrants (New York: New Directions, 1996).

- 17Marina Warner, “What Are Memory Maps”, accessed October 8, 2019, http://www.vam.ac.uk/content/articles/m/memory-maps-about-the-project/

- 18Ibid.

- 19Simon Schama, Landscape and Memory (New York: Vintage, 1995).

- 20Warner, “What Are Memory Maps.”

- 21The notion of the chronotope is usually traced back to Mikhail Bakhtin, “Form of Time and Chronotope in the Novel,” in The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, ed. Michael Holquist (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981), 84–258.

- 22Vance Packard, The Waste Makers (New York: David McKay&Co, 1960).

- 23For examples of sculptural treatments of projectors, celluloid, and editing tables, see the work of Tacita Dean, Rodney Graham, Rosa Barba, Sandra Gibson, and Luis Recoder.

- 24Wikipedia entry on “Obsolescence,” accessed May 19, 2018, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Obsolescence.

- 25The original phrase is: “an image is that wherein what has been comes together in a flash with the now to form a constellation. In other words: image is dialectics at a standstill. For while the relation of the present to the past is purely temporal, the relation of what has been to the now is dialectical: not temporal in nature but figural. Only dialectical images are genuinely historical.” Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” in Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zoon (New York: Schocken Books, 1968), 253–64.

- 26See Thomas Elsaesser, “Media Archaeology as the Poetics of Obsolescence,” in Film History as Media Archaeology (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016), 331–50.

- 27Marshall McLuhan, “The Tetrad of Media Effects,” in Marshall McLuhan and Eric McLuhan, Laws of Media: The New Science (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988). Emphases mine.

- 28Rosalind Kraus, A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition (London: Thames & Hudson, 2000).

- 29Jeremy Tambling, Becoming Posthumous: Life and Death in Literary and Cultural Studies (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2001), 4.

- 30On the topic of biodigital fusion, see for instance Richard van Hooijdonk, “The 4th industrial revolution: ‘a fusion of our physical, digital and biological worlds,’” accessed October 2, 2019, https://richardvanhooijdonk.com/blog/en/the-4th-industrial-revolution-a….

Abel, Richard, ed. French Film Theory and Criticism 1907–1929. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988.

Assmann, Aleida. Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Media, Archives. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. "Form of Time and Chronotope in the Novel." In The Dialogic Imagination: Four Essays, edited by Michael Holquist, 84–258. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981.

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. New York: Hill and Wang, 1981.

Bazin, André. “The Ontology of the Photographic Image.” Film Quarterly, 13, no. 4 (Summer 1960): 4–9.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Images malgré tout. Paris: Edition Minuit, 2004.

Elsaesser, Thomas, ed. Harun Farocki — Working on the Sightlines. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2004.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Media Archaeology as the Poetics of Obsolescence.” In Film History as Media Archaeology, 331–50. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016.

Foster, Hal. "What’s Neo About the Neo-Avant-Garde?" October 74 (Fall 1994): 5–32.

Halbwachs, Maurice. On Collective Memory. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992.

Kraus, Rosalind. A Voyage on the North Sea: Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition. London: Thames & Hudson, 2000.

McLuhan, Marshall. “The Tetrad of media effects.” In Laws of Media: The New Science, Marshall McLuhan and Eric McLuhan. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1988.

Meillassoux, Quentin. After Finitude: An Essay on the Necessity of Contingency. London: Bloombury, 2008.

Nora, Pierre. "Between Memory and History: Les Lieux de Mémoire." Representations 26 (Spring 1989): 7–24.

Nora, Pierre, ed. Les Lieux de Mémoire. Paris: Gallimard, 1984–1992.

Nora, Pierre, and Lawrence D. Kritzman, eds. Realms of Memory. Columbia: Columbia University Press, 1996.

Packard, Vance. The Waste Makers. New York: David McKay&Co, 1960.

Schama, Simon. Landscape and Memory. New York: Vintage, 1995.

Sebald, W.G. On the Natural History of Destruction. New York: Random House, 2003.

Tamblin, Jeremy. Becoming Posthumous: Life and Death in Literary and Cultural Studies. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2001.

Warner, Marina. "What are Memory Maps." V&A website. http://www.vam.ac.uk/page/m/memory-maps/