Liberated on Film

Images and Narratives of Camp Liberation in Historical Footage and Feature Films

Table of Contents

Liberated on Film

Mexican Public Health History through Film

Reel Life

Film as Instrument of Social Enquiry

Visibility and Torture

Trapped in Amber

Be Part of History

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Weckel, Ulrike: Liberated on Film: Images and Narratives of Camp Liberation in Historical Footage and Feature Films. In: Research in Film and History. Research, Debates and Projects 2.0 (2019-11-25), No. 2, pp. 1–21. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14796.

Since SS camp personnel obeyed the strict prohibition against photography in Nazi annihilation, concentration, and work camps, the footage that Allied cameramen shot in such camps during and shortly after their liberation filled this void in visual documentation. Thus, what we imagine went on in Nazi camps while in operation has been shaped by pictures that document their very last stages, after the SS had fled most of these crime scenes, most inmates had been killed or died, and tens of thousands of the still living had been evacuated on death marches. So, though the arrival of Allied soldiers was a turning point for survivors, the film that Allied cameramen shot in those days tells us more about the effects of Nazi terror than about survivors’ liberation from it. This perception is not contrary to the cameramen’s intentions. They had been ordered to film evidence of Nazi crimes for use in future trials, to justify the high number of casualties to home audiences, and to confront Germans with what they had obviously not let themselves worry too much about. The narrations of the Allied atrocity films compiled from this footage make it clear that it was shot during the liberation of camps; however, they quickly go on to teach the lessons that the filmmakers wanted their different audiences to learn from the shocking remnants of Nazi criminality. 1

The provenance of these images is far less clear today. Clips and stills from the liberation footage have been reproduced over and over again removed from their original context and included in big-screen and television documentaries, books, and exhibitions, not to mention searches on the Internet, where they have been mixed with images of different origins that have also come to represent the Holocaust: clips from the exceptional footage that the Nazis took in camps and ghettos, namely, Westerbork, Theresienstadt, and Warsaw, to use in deceptive propaganda; 2 filmed photographs from the now well-known SS album covering the selection process at Auschwitz-Birkenau; 3 and rare film and filmed not-so-rare photographs of pogroms and mass executions shot by German soldiers behind Germany’s Eastern front.4 Images of these different origins are usually mixed together in order to give viewers a vivid, disturbing sense of how horrendous Nazi crimes were. But conveying their horrendousness does not yet explain anything about them. Moreover, not keeping images’ origins straight has led to misconceptions, e.g., of the conditions in different camps at different times and the belief that the Nazis shamelessly documented their crimes on film.

However, in this contribution I am not going to recontextualize frequently shown clips or discuss the extent to which the liberation footage, though shot after the fact, can nevertheless serve as a source for studying the history of the Holocaust. Instead, I shall examine some lesser-known shots that reveal the situation from which they originate, namely, liberators’ encounters with the liberated, encounters that overtaxed both sides. On the one hand, many liberators expressed disbelief at what they saw in front of them and mixed feelings of pity, disgust, guilt, and outrage.5 On the other hand, what liberation meant for the liberated and how they experienced it differed from camp to camp and from person to person, depending on a survivor’s physical and mental state, how long he or she had been confined, and on what this person knew or did not know about the fates of family and friends, to name just a few crucial variables. Little of this could be observed by liberators or recorded by their cameras. This raises the questions whether Allied cameramen and filmmakers, aware of how limited their understanding was, still tried to tell filmically stories of liberation and, if so, what they were. Creating telling images of the perplexing encounters between liberators and liberated has been easier for feature filmmakers, who know some of the numerous memoirs and interviews of both survivors and veterans that have appeared since the end of the war. In order to assess the advantages that fiction has over the documentary footage of the time I shall discuss some feature films that include scenes of camp liberation.

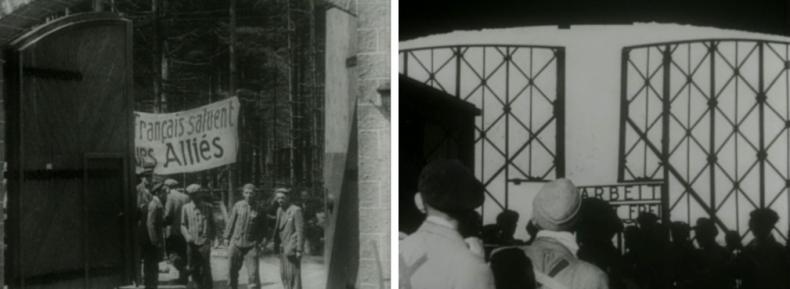

Historical Liberators’ Looks at Survivors

The most straightforward attempt to tell a liberation story filmically was never edited or shown publicly. In the first days after the Red Army had reached Auschwitz on January 27, 1945, not much was filmed. The Soviets shot most of their Auschwitz liberation footage weeks later, when cameramen and film stock were again available, as was a spotlight for filming inside huts. 6 At this later time, when the snow visible in the earlier footage had melted, cameramen staged a jubilant liberation scene of the sort one would have naively expected or wished for. 80 seconds of film are shot from several angles, requiring repetitions of the performance. About 50 men, women, and children stand densely packed together, looking out through the gate of Stammlager Auschwitz I with its infamous “Arbeit macht frei.” One of the cameramen, Alexander Vorontsov, claimed in an interview in the 1980s that they were survivors who, having left the camp a month earlier and recovered, happily volunteered to return for the filming. This does not sound very likely, but, be that as it may, none of the extras looks on the verge of death or even weak or sick. Unlike the famous scene of a large group of small children who had survived Mengele’s experiments on twins, only two men in the crowd wear striped prisoner’s uniforms. In the first frames, we see the inmates longingly awaiting their liberators and then waving their caps as some Red Army soldiers enter the picture, pointing their weapons towards the gate. This detail was probably supposed to signal the audience that the Red Army was prepared to fight the SS. There being no guards, as was really the case, the soldiers simply lift the barrier and break open the gate, against which the prisoners are already impatiently pressing. They are then shown, from three different angles, cheerfully pouring through the opened gate, still waving their caps, some embracing their liberators. The last frames show the barrier rising across the gate’s infamous inscription against the sky.

Since 1941, Red Army film crews had been instructed to, first, film traces of German atrocities, in order to rally public support for the costly Soviet war effort, and, second, portray the Red Army as powerful and effective, to raise hopes that victory would come soon, and they had become experts in this.7 When cameramen entered the annihilation camps of Majdanek, in July 1944, and Auschwitz, six month later, the patterns of composition they had developed in the field were not sufficient. They had to find new ways to film vast camps in which only a few survivors wandered amid empty huts and mass graves, i.e., to represent what was no longer there.8 Yet, the staged jubilant liberation seems to have been an attempt to follow the tradition of the happy ending. However, the filmmakers never edited or showed it because, as Vorontsov later explained, “it in no way corresponded to the bleak reality of January 27.” 9

The Soviets compiled three films that included their footage of the liberated annihilation camps, dubbed versions of which were distributed in the West. The one on Majdanek, made in 1944, is 15 minutes long; the one on Auschwitz in 1945 is 21 minutes long; and the third, 60 minutes long and made be screened at the Nuremberg trial in February 1946, documented German crimes in many places in Eastern Europe including Majdanek and Auschwitz.10 Compiled to be damning accusations of the Germans and their fascist regime, none of the three contains a single image of triumph or elation. However, they present another emblematic motif of camp liberation, probably the most iconic: survivors standing behind a barbed wire fence filmed from a slowly passing vehicle. This scene was also staged, first in Majdanek and re-staged at Auschwitz with improved results.

The first time, the shots are blurry; one man seems to be raising his clenched fist, but this detail is easily missed. The second time, the survivors were arranged according to height, so that the viewer sees the faces of most as they look directly into the camera, and carefully chosen to represent a spectrum: different ages and sexes, with and without caps, some wrapped in blankets, one bandaged, another on crutches, some shyly smiling, others serious. These are liberators’ point-of-view shots. The motif suggests that after the SS had left inmates gathered at a fence, waiting for outside help to arrive, unable to do anything else. Their looking into the camera suggests that they have just spotted their liberators, and liberation was 3 imminent. And yet, these edited scenes, unlike the unedited triumphant liberation sequence, do not indicate a happy ending. For the survivors behind the fence look miserable, and the viewer can guess at their mistreatment, a guess that the films confirm by depicting corpses; the ruins of blown-up gas chambers and crematoria; heaps of the belongings of the dead, which the SS had stored in huge warehouses; torture instruments; and inmates in deplorable condition being examined by Allied doctors and carried by fellow prisoners since they could not walk on their own. With these later shots in mind, we see that this scene of inmates’ waiting for their liberators can just as easily be read as a representation of their coming later than they should have.

Shots of gates being pushed open and prisoners happily greeting their liberators seem to have suggested themselves at the time. Various Allied cameramen arranged such scenes.

Some of these sequences look as if the initiative to stage them could have come from the survivors themselves, who wanted to symbolize victory, international solidarity, or express respect for the dead by collectively waving into the camera, giving the victory sign, or taking off their caps. This is definitely true of the liberation ceremonies and May Day celebrations that international committees of political prisoners organized, e.g., in Ebensee, Mauthausen, Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen.

Footage of these celebrations exists;11 however, it was seldom included in the Allied documentaries, for they were supposed to tell another story. DIE TODESMÜHLEN, which the US Military Government for Germany screened to German audiences in its zone of occupation in early 1946, includes some shots of such joyful moments, but it was careful to frame them so that they would not lessen the overall impression of horror and misery. The film sets its tone by starting with a scene of preparations for the funeral that men from the town of Gardelegen were ordered to hold for evacuated forced laborers burnt to death in a nearby barn.12 The narrator then states that there had been more than 300 Nazi camps, “death mills all of them until their gates were pushed open by the Allied armies.” After some brief shots of celebrating survivors, he adds, “But immediate help was needed, in order to curb the mass starvation of inmates.” 13

All of the Allied documentaries portray this help more or less explicitly, yet it is surprisingly seldom that we see survivors and liberators genuinely interacting, e.g., in conversation or through bodily contact, of which there must have been more than we are shown.14

There might be more of this in unedited footage, but it is equally possible that cameramen did not think it important to cover such human interactions. What Allied cameramen apparently did not even try to cover was liberators’ own bewilderment, which they regularly expressed in memoirs and interviews. In order to see images of this, we have to turn to feature films, which I will now do. In addition to feature films’ ability to turn the camera back on the liberators who in 1944–45 turned their cameras on the liberated camps, they can also tell stories of liberation from the perspective of survivors.

Fictional Looks at Liberators

Some feature films about World War II end with Allied soldiers coming across a German concentration camp, e.g., THE YOUNG LIONS (Edward Dmytryk, US 1958) and THE BIG RED ONE (Samuel Fuller, US 1980).15 Regularly, the essence of these episodes is that hardened combat soldiers, who have seen and been through so much, are stunned at the sight of emaciated, helpless inmates in overcrowded huts and break down or fly into a rage against the Germans. Arguably, the most detailed dramatization of American soldiers’ reactions to such a confrontation is in the television miniseries BAND OF BROTHERS (US 2001), produced by Steven Spielberg and Tom Hanks, which is based on the real experiences of the men of “Easy Company” of the 101st Airborne Division.16 In the ninth episode, entitled “Why We Fight,” more than ten months after having parachuted into Normandy and with the war still dragging on, several of the fictionalized characters have become cynical about the war. But in Bavaria they come across a camp of famished, sick, and mostly Jewish forced laborers; shocked, they hectically organize rescue work and force local German civilians to bury the many corpses. They now feel that the war is justified. 17

Soldiers of the 101st Airborne Division really did liberate the Kaufering IV sub-camp of Dachau near Hurlach on April 28, 1945, and compelled Hurlach’s inhabitants to carry the dead to mass graves. 18 In the Kaufering sub-camps, mostly Jewish forced laborers had had to build subterranean aircraft factories, and the brutal work conditions, malnutrition, and disease had resulted in a high mortality rate. With the advance of American troops, the SS evacuated the inmates from these sub-camps, except for Kaufering IV, whose inmates, because it was used as a sick camp, were too weak to move. SS guards shot hundreds of them and set fire to the huts before fleeing the typhus-ridden camp. From historic footage and photographs of the Kaufering IV liberation,19 the filmmakers could recreate the camp with its double fence, wooden gate, watchtowers, and huts dug into the ground and camouflaged with grass on their roofs against detection from the air.

Nearly 20 minutes long and with several dramaturgical turning points, the liberation narrative in BAND OF BROTHERS allows for the portrayal of numerous reactions that historical liberators remembered experiencing. At the start, six soldiers on patrol in a forest and put on alert by the uncanny quiet carefully approach a clearing and stare, obviously distressed, at something off screen. One of them races back to the town but cannot tell Major Richard Winters (Damian Lewis) more than that they have found “something”; asked what it is, he answers, visibly stunned, that he does not know. As Winters and the rest of the company approach the site in vehicles, viewers get their first shaky glimpse of a smoldering compound behind barbed wire onto which some thin figures are holding.

Solemn, minor-key symphonic music creates an unearthly atmosphere of awe. In the course of the scene, several of the soldiers take off their helmets as if they have entered a church. Usually talkative, most of the men are speechless; we hear only a few brief orders and remarks. They cut the chain on the gate and open it, and viewers see the pale, filthy, and miserable inmates in liberators’ point-of-view-shots. All wear striped uniforms, many with yellow stars. Contrary to the historical footage, the camera focuses the viewers’ gaze on the disturbed faces of the liberators, even more intensely than on the liberated. Some stare in apparent disbelief; some cover their eyes or noses with handkerchiefs; some get sick; others cry. These are no reverse shots from the perspective of survivors, some of whom are trying to interact with their liberators, apparently asking for food, tearing at their sleeves, or hugging and kissing them. Rather, when the camera does not show us the scene from the soldiers’ perspective it circles them dizzyingly to suggest how they feel. Though the liberated figure prominently in the episode, it remains the story of the “band of brothers” who are transformed by this terrifying experience.

21st-century viewers recognize what the series’ liberators still do not. Corporal Joseph Liebgott (Ross McCall), who speaks some German, translates what one of the survivors tells them, constantly scratching his head: This is a work camp of “Unerwünschte,” who, as the man explains, are not criminals but “undesirables,” from all kinds of professions, mostly Jews, and there is a women’s camp close by. This last piece of information angers Liebgott still further.20 The soldiers first distribute their rations; then they commandeer the bread from the town’s fat, protesting baker and begin to hand it out, only to learn from the regimental surgeon that they have to stop, because the starving will eat themselves to death, and confine the liberated to the camp for the time being in order to control their diet and prevent them from wandering away. Liebgott breaks down as he tells the incredulous prisoners that they must return to the compound. Two soldiers discover that some of the emaciated corpses are tattooed with numbers, “like cattle”; two others enter a dark hut and shine their flash lights on survivors too feeble to get out of the wooden racks upon which they lie;21 yet others stumble upon a freight car full of corpses.22 Major Winters will not learn before evening from headquarters that American troops are finding similar camps “all over the place.” The Russians have liberated one that seems “a lot worse.” “Worse?”, Captain Lewis Nixon (Ron Livingston) asks, incredulously. “Yes, apparently, ten times as big, executions chambers, ovens…”

There is nothing triumphant, joyful, or even happy in this liberation scene; nobody ever smiles. However, the liberation story does end with a scene that offers viewers some emotional gratification. Before the patrol had discovered the camp, Captain Nixon, a heavy drinker, was searching the conservatively furnished living room of a wealthy German home, apparently looking for alcohol. After examining the framed photograph of a haughty German general, decorated with a mourning band, he lets it drop to the floor, and the glass shatters. At this moment, the widow enters the room and proudly stares at him in contempt. Ashamed, Nixon leaves the house. On the evening after the camp’s liberation, Nixon hears from Winters that the townspeople, who had claimed not to have known of the camp’s existence, were going to get “a hell of an education” the next morning when they will have to bury the corpses. Nixon wants to see that, but Easy Company will be moving out at noon; so, he drives to the camp early in the morning. Among the cowed Germans meekly dragging or carrying the dead, he spots the widow. In shot-reverse-shot, they stare at each other until she lowers her well-coiffed head in shame.

Survivors’ Looks at Liberators and Their Feelings upon Liberation

Naturally, the historical liberation footage does not represent the survivors’ perspective. Only a few feature films supply this. In SCHINDLER’S LIST (Steven Spielberg, US 1993), overall a rescue-story, the liberation, which comes after the highly sentimental good-bye to Schindler, is anti-climactic. The surviving “Schindler Jews” in the Brünnlitz labor camp are still asleep on the ground at the opened gate when a single mounted Russian soldier appears, proclaiming grandiosely, “You have been liberated by the Soviet Army!” The survivors get up, rubbing their eyes, and Itzhak Stern (Ben Kingsley) asks him if there are any Jews left in Poland. The soldier looks puzzled. “Where should we go?”, asks someone else. The movie tries to sum up the dilemma of liberated Jewish survivors in the soldier’s answer: “Don’t go East, that’s for sure. They hate you there. I would not go West either, if I were you.”

If filmmakers want to portray survivors’ perceptions of their liberators and their feelings in the moment of liberation realistically, they can get inspiration from the memoirs of authors who wrote eloquently about this situation. One of the most vivid, self-reflective reports of liberation and its long aftermath is The Truce (La tregua in the Italian original, whose literal translation is ‘the reprieve’ or ‘the breathing time’), which Primo Levi first published in 1963 as a sequel to If This Is a Man (Se questo è un uomo), his seminal book from 1947 about his eleven months in Auschwitz. In 1997, the Italian screenwriter Tonino Guerra and director Francesco Rosi filmically adapted The Truce. Their film includes shots of liberators from the perspective of Levi (John Turturro) and his fellow prisoners; in fact, it concentrates on their perceptions to the extent that the liberators are reduced to extras. However, Guerra and Rosi took artistic liberties, and they needed the expressive skills of an excellent actor to capture filmically the mixed emotions that Levi describes in a way that cannot possibly be represented visually.

Together with some hundred others, Levi had been abandoned in the sick compound of the Auschwitz work camp Buna-Monowitz by the fleeing SS in mid-January 1945. Ten days later, according to his memoir, Levi and a fellow prisoner were carrying their first dead roommate to a common grave when they saw a patrol of four Russian soldiers on horseback, “who stopped to look, exchanging a few timid words, and throwing strangely embarrassed glances at the sprawling bodies, at the battered huts and at us few still alive.”23 Levi recalls that the soldiers “seemed wonderfully concrete and real,” and his description of them almost reads as an instruction to filmmakers: “perched on their enormous horses, between the grey of the snow and the grey of the sky” and, a little later, as armed “but not against us: four messengers of peace, with rough and boyish faces beneath their heavy fur hats.”24 However, the complex thoughts that follow are moral, not imagistic:

They did not greet us, nor did they smile; they seemed oppressed not only by compassion but by a confused restraint, which sealed their lips and bound their eyes to the funereal scene. It was that shame we knew so well, the shame that drowned us after selections, and every time we had to watch, or submit to, some outrage: the shame that Germans did not know, that the just man experiences at another man’s crime; the feeling of guilt that such a crime could exist, that it should have been introduced irrevocably into the world of things that exist, and that his will for good should have proved too weak or null, and should not have availed in defence.

Levi goes on to say that the joy the liberated felt was undermined by their realization that nothing could ever cleanse their consciences and memories; “the scars of the outrage” would remain with them forever. Human justice could not eradicate the evil that they had witnessed and experienced. This is how Levi explains in retrospect why so few of the inmates had run to greet their liberators and why so few had fallen down in prayer, for with joy had come “an unexpected attack of mortal fatigue.” For the rest of the day, nothing else happened, and the liberated inmates avoided talking about their liberation “because face to face with liberty we felt ourselves lost, emptied, atrophied, unfit for our part.” 25

Except for this line, which the film almost quotes, the liberation scene in THE TRUCE bears little resemblance to Levi’s description. Rather, it presents its own filmic narrative of an ambivalent moment. After a short, chaotic, and noisy introductory scene in which SS men set fire to huts, shoot some prisoners, order others to burn documents, and blow up a crematorium, the next scene starts very quietly, calmly, and slowly. On the horizon, which is barely visible between “the grey of the snow and the grey of the sky,” four horsemen appear; they come closer and stop. We see in close-up the fur cap of one with a small gold hammer and sickle in a Soviet red star. It is too foggy to read the look in his eyes. One of the four takes out binoculars and inspects what lies in front of them. Cut. From inside the camp, we now see two inmates carrying a dead man in a blanket-- others in the background are doing the same--and with a last of their strength roll the corpse into a ditch filled with other corpses and collapse. It is when one of the two stands up, catches his breath, looks around, and sees the four horsemen in the distance that we understand that he is the protagonist, Primo Levi.

Since the beginning of the scene, the only sounds have been the horses’ hooves and the inmates’ wooden clogs on the hard snow and horses breathing heavily. Next comes a series of shot-reverseshots between, on the one side, Levi, his comrade, and other inmates who are slowly approaching the fence and, on the other side, and through their binoculars, the Soviet soldiers. The horses are filmed from a low camera angle so that they do look enormous, as Levi describes them in his memoir. Contrary to the memoir, however, the soldiers, who have now reached the gate, are expressionless; they show no sign of shock or shame even though they must realize that they have come across an immense crime. Rather, they seem coarse, impassive, at best focused on the task before them. Thus, THE TRUCE neither grants the Soviet soldiers the reactions of “the just man” witnessing someone else’s crime, which Levi saw in them, nor does it stage the inmates awaiting their liberators as impressively as Red Army cameramen did at Auschwitz. THE TRUCE does seem to quote historical Soviet footage; however, its shots of prisoners lining up along the barbed wire resemble the blurry Majdanek shots much more than the famous ones at Auschwitz.

To return to the scene, the soldiers check for current in the fence and finding none pull down the metallic gate, which falls to the ground with a loud crash. We see the wide-open gateway shot against the sky; however, it is quiet once again, and nobody moves. The camera zooms in on Levi, whose overlapping red and yellow triangles on his striped jacket identify him as a Jew and a political prisoner, and it is now that the film quotes the memoir: “Face to face with freedom we felt lost, emptied, atrophied, unfit for our new-found liberty.”26

Music quietly began to play with Levi’s words. The scene then becomes dramatic. The inmates, still behind the open gateway, come to life. “We are free,” some shout, as they all begin to stagger out through the gateway; a woman crosses herself; others embrace. As they move towards the stationary camera shooting up from the ground, their legs and feet fill the screen. A man falls on his knees, in gratitude or prayer, right in front of the camera. From here on, the soundtrack dominates the scene and controls viewers’ emotional responses. A triumphant symphonic motif begins to play as the camera shows the liberated, elated despite their weakness, from different angles. Then, their faces freeze; their eyes widen in fright; and their shouting turns panicky. Accompanied by threatening brass music, many more horsemen appear on the horizon and approach the camp followed by army vehicles on one of which flutters a big red flag. Those who had passed through the gate now turn around and run back into the camp, except for Levi, who stands on the threshold, nearly overrun by the panicked crowd. As he calmly observes the theatrically approaching Red Army, a range of mixed emotions plays across his face. At the end of the scene, the music returns to the triumphant motif, and Levi, with a tender smile, lifts his left hand to wave at the liberators, thereby revealing the number tattooed on his arm.

Though THE TRUCE employs many filmic devices to tell its liberation story from the survivors’ perspective in a compelling way, it still must turn an interior drama into action. What Levi describes in his memoir as survivors’ ambivalence, conflicting feelings that were surprising because they were experienced simultaneously, the scriptwriter converts into plot twists that surprise the audience. So, the film’s survivors are first numb, then alive with joy, and a moment later terrified of what comes next (if not of the Red Army, though that is not be well motivated). It is only the protagonist whose face and narrated words express the complex emotions that Levi the author describes as a collective dilemma.

A Tale of Self-Liberation and its Revision

No survey of feature films narrating the liberation of camps can leave out what is arguably the most triumphant variation, the DEFA film NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN (NAKED AMONG WOLVES, Frank Beyer) of 1963. It, together with the novel of the same title by the Buchenwald survivor Bruno Apitz that it adapted, introduced the powerful tale of antifascists’ self-liberation at Buchenwald, which became a crucial part of the GDR’s founding myth.27 In NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN, an international underground in Buchenwald works with high-ranking German Communist prisoner functionaries to hide a young Jewish boy from the SS although this puts their preparations for an armed revolt at risk and the SS tortures two members in their efforts to find the child.

The film culminates in a showdown between prisoners and SS that ends in a twofold victory for the antifascists: a victory over the SS by successfully storming the camp’s watchtowers and main gate and a victory for their humanity by saving the life of the child. The tale of Buchenwald’s self-liberation is not completely made up, though it was far less spectacular than as portrayed in the film and unrelated to the rescue of one particular child. There was a strong, well-organized clandestine international committee of political prisoners, mostly Communists, in Buchenwald. Also, German Communists had been able to take over positions of prisoner functionaries (kapos) from prisoners classified as criminals or asocials, with whom the SS usually filled such positions. Kapos had limited power to make decisions; for example, they could protect prisoners by assigning them less dangerous work or excluding them from deportation at the expense of others. Buchenwald’s so-called ‘red kapos’ used their influence to improve the survival chances of their own group, German Communists, and to shield the underground committee that was preparing an armed uprising in the expected case that the SS would attempt to kill all of the inmates before fleeing the camp.28 It is also true that of the hundreds of children incarcerated in Buchenwald, some Jewish and many Roma and Sinti, at least twelve were taken off a deportation list, among them a three-year-old Jewish boy, and replaced by others;29 however, this detail of NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN’s liberation tale is of less interest given my focus on visualizations of camp liberation.

The underground had taken advantage of the chaos caused by an air raid in August 1944 to smuggle weapons into the camp and formed a prisoner militia. As a result, they no longer felt completely powerless about what the SS would inflict on them when the Allies neared the camp. On April 1, 1945, they learned that American troops were within about 60 kilometers of Buchenwald and could reach it in a few days. In light of this information, the red kapos tried to obstruct further evacuations, and some of the SS’s roll calls met with passive resistance. On the morning of April 11, gunfire could to be heard, and the SS prepared to flee. According to the reports of liberated inmates, the last SS guards abandoned the watchtowers at 3:00 pm, and the prisoners’ militia, which had been standing by, immediately took control of them and their machine guns, raised a white flag on one, and cut the barbed-wire fence.30 Someone from the international committee ordered the inmates over the loudspeaker to maintain their discipline. Some prisoners arrested the few SS men who were hiding in the camp; others searched the surrounding woods for those who had fled and captured more than 60, several of whom had dressed as civilians or prisoners. The American troops encountered armed prisoners patrolling in the camp’s vicinity, and when the first soldiers entered Buchenwald between 4:00 and 5:00 pm they were greeted with cheers by those inmates who were strong enough to participate in the liberation.31

In DEFA’s NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN, some SS men remain in the camp, armed and dangerous, until the end, and the Americans are never seen. After the angry, impatient order over the loudspeaker for the prisoners to fall in for roll call fades over the empty Appellplatz,32 the commandant directs a large detachment of armed SS into the camp, and he threatens the Communist camp senior, Walter Krämer (Erwin Geschonnek),33 that all of the inmates will be shot unless they fall in. However, a siren then signals an air raid, and the head of the underground, Herbert Bochow (Gerry Wolff), orders the militia to break out the hidden weapons and get ready. While some open fire on the watchtowers from within the huts, a large group storms the main gate in the best action-film style.

They open it easily and then climb the watchtowers and shoot or disarm the guards who, despite their machine guns, have not been very effective against the coordinated revolt. Meanwhile, other prisoners have cut a barbed-wire fence to pursue fleeing SS men, many of whom they bring back as their prisoners. Finally, Bochow enters the commandant’s abandoned office, grabs the microphone, and, after shyly clearing his throat, shouts, “Comrades, we are free… free… free,” with increasing enthusiasm. With the second “free,” the film cuts to the huts from which we hear a victorious howl as hundreds of prisoners pour out into a triumphant mass that, shot from above, happily runs towards the gate.

It is an uplifting liberation scene of the sort that one might have wished for in real life. These prisoners are neither miserable nor powerless; they do not wait in desperation for the Allies to arrive but free themselves, attacking the SS and taking as many of them prisoner as they can. The morally questionable decision of antifascists to cooperate with the SS as kapos is here shown to have been justified and, moreover, ennobled by their having followed their heartfelt desire to save the child they were hiding at the expense of party discipline.34 The film was a big success at the Moscow International Film Festival in 1963, and the head of DEFA at the time, Jochen Mückenberger, later recalled how enthusiastically the audience in the Kremlin’s Great Hall had responded to the final scene.35 The film was not only distributed in all of the Socialist countries but also in several countries in the West, where many critics praised it for its humanistic message, psychologically differentiated characters, and artful cinematography.36 In his generally positive review, the film critic of the New York Times at least noted that the audience never learns who actually liberated the camp.37 Harsher criticism came from the Polish daily Polityka whose reporter complained that the film’s elevating end stood in stark contrast to the historical footage that American army cameramen had shot of Buchenwald’s liberation, which showed half-burned corpses and skeletal survivors. 38

In 2015, German public television produced a remake of NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN (Philipp Kadelbach), apparently wanting, on the one hand, to profit from the fact that more or less all former East Germans knew the novel or the film or both39 and therefore might tune in and, on the other hand, to set straight some of what the broadcasters and filmmakers took to be ideological in the DEFA film. In current television docu-drama style, the remake inserts short clips of historical footage with historical explanation superimposed, specifically of the American army’s advance through Germany and of camp liberations pre-dating that of Buchenwald, namely Auschwitz and Ohrdruf. The effects of the historical footage, in addition to “authenticating” the fictionalization through the mixture of images, are, first, that the advance of the American troops is a constant theme, discussed by both SS and inmates, and, second, that viewers anticipate what Buchenwald might look like if the SS were to try to kill off the inmates. Kadelbach’s remake also differs from the original in that its prisoners are more deplorable looking, many more are identifiably Jewish, and part of the story takes place in Buchenwald’s Little Camp, a camp within the camp, in which the weak and sick evacuees from Eastern camps were locked up. Viewers also see the brutal working conditions in the quarry. And the SS’s violence is portrayed much more vividly and prominently. The filmmakers took into account that Holocaust movies had become a genre, with an iconography from which they quote, to which they apparently wanted to live up.40

In several respects, the color remake of NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN portrays Buchenwald and its liberation more accurately and realistically than the black-and-white original. For example, in the remake Unterscharführer Reineboth (Sabin Tambrea) does not follow his orders to command the SS to gun down the inmates; rather, he orders them to abandon the camp. Because they flee in haste, the underground does not need to fight to get to the tower and raise the white flag. While this is closer to the historical truth than the scene in 1963, the story of the hidden child’s survival is much more sentimental. Instead of the DEFA film’s coda of a triumphant mass scene, near the ending of the remake the boy’s “camp father”, Hans Pippig (Florian Stetter), sacrifices himself to save the boy and begins to die a slow death in close-up as the boy’s little hand grabs his.

However, what really comes as a surprise in the remake is that nobody rejoices over the camp’s liberation. Camp senior Krämer (Sylvester Groth) joylessly announces over the microphone, “We are free.” “The SS has fled,” he adds gloomily, “the camp is in our hand.” He urges the inmates to maintain discipline and, specifically, to refrain from lynching because otherwise, he says, they would not be “any better than the SS murderers.” His fatigue and depression in this moment are unexplained. More and more inmates appear on the Appellplatz, but they are detached and disoriented. They meander about the square, apparently uninterested in the open gate. Again, the audience gets no explanation for their lack of cheer.

It sees Reineboth dressed in a prisoner’s uniform and with his head shaved deceive the credulous American soldiers he meets on his escape and Krämer erupt into a sudden rage in the commandant’s office, sweeping everything from the desk, ripping pictures and coat hooks off the wall, kicking the furniture, and breaking windows until, out of breath, he falls into a chair. The tortured Communist who did not betray the underground is freed from his cell. Back on the Appellplatz, prisoners watch in silence as the white flag is raised, and the child’s savior finally dies. The audience is clearly supposed to feel that this is no happy ending, that a camp’s liberation does not make up for what took place there. Strangely, however, the film projects these emotions onto the survivors. But why they are not happy at their liberation remains a mystery. Are Krämer and the other kapos supposed to be overwhelmed by bad conscience at having cooperated with the SS? If so, the film would have to have hinted earlier at the gross abuses of power, like liquidating their enemies among the inmates, of which some of the historical red kapos were accused.41 Yet, the film does not do this. It just inverts DEFA’s heroic showdown and triumphant ending.

Conclusion

Obviously, it is difficult to tell the story of the liberation of Nazi camps on film, whether in a documentary or a fictitious or fictionalized movie. The large majority of inmates were murdered, not liberated; many of the survivors died within weeks of being liberated; and others remained traumatized for the rest of their lives. The SS had abandoned the camps and the Allies had arrived, but many survivors, especially Jews, did not know where to go and were soon to learn of the deaths of many or even most of their family and friends. Therefore, telling a rescue story with a happy ending might seem inappropriate. At the same time, however, the end of Nazi terror and murder did make an enormous difference to survivors and was something to rejoice about. Survivors’ realization that they were lucky still to be alive and their simultaneous awareness that millions of others had not been that lucky generated survivor’s guilt in many. As contemporary observers of camp liberations, Allied cameramen seem to have found it a difficult task to document survivors’ relief and joy while ensuring that their footage did not downplay the Nazis’ crimes and their victims’ suffering. Feature films are better able to tell stories that depict the ambivalence of liberation. They can also stage liberation as a fantasy, which inmates might have had and which audiences would prefer to see, by telling an obvious fairy tale, as in LIFE IS BEAUTIFUL (Roberto Benigni, IT 1997) and TRAIN DE VIE (Radu Mihăileanu, F/BE/NL/IL/RO 1998). The viewers’ final realization that such a liberation was only a fairy tale instills in them a novel kind of sadness with the potential to instruct in new ways.

- 1On film crews’ instructions, filming conditions, the compilation films, their narrations, and German viewers’ responses, see Ulrike Weckel, Beschämende Bilder. Deutsche Reaktionen auf alliierte Dokumentarfilme über befreite Konzentrationslager (Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2012).

- 2See, e.g., Florian Krautkrämer, ed., AUFSCHUB. Das Lager Westerbork und der Film von Rudolf Breslauer / Harun Farocki (Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2018); Thomas Elsaesser, "Returning to the Past its Future. Harun Farocki’s RESPITE,” Research in Film and History 1, https://filmhistory.org/issues/text/returning-past-its-own-future; Lutz Becker, “Film Documents of Theresienstadt,” in Holocaust and the Moving Image. Representations in Film and Television Since 1933, ed. Toby Haggith and Joanna Newman (London, New York: Wallflower, 2005), 93–101; Karel Margry, “Das Konzentrationslager als Idylle: THERESIENSTADT – EIN DOKUMENTARFILM AUS DEM JÜDISCHEN SIEDLUNGSGEBIET,” in Auschwitz: Geschichte, Rezeption und Wirkung, ed. Fritz Bauer Institut (Frankfurt: Wallstein, 1996), 319–52; Anja Horstmann, “Das Filmfragment GHETTO – erzwungene Realität und vorgeformte Bilder,” in Dossier Geheimsache Ghettofilm, ed. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (Bonn, 2013), http://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/geheimsache-ghettofilm….

- 3The album is available online at https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/album_auschwitz/arrival.asp. It was long assumed that the photographs documented one transport, the one in which the discoverer of the album, the survivor Lili Jacob, had arrived at Auschwitz. Closer inspection has proven that the photographs are from at least four transports of the ‘Ungarn-Aktion.’ See Stefan Hördler, Christoph Kreutzmüller, and Tal Bruttmann, “Auschwitz im Bild. Zur kritischen Analyse der AuschwitzAlben,” Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 63, no. 7/8 (2015): 609–32. For an instructive indepth analysis of the photographs as images and their suggestive arrangement in the album, see Ulrike Koppermann, “Das visuelle Narrativ des Fotoalbums ‘Umsiedlung der Juden aus Ungarn.’ Ein kritischer Blick auf die ‘Täterperspektive’,” Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 67, no. 6 (2019): 518–27.

- 4Most often used is Marinefeldwebel Reinhard Wiener’s short clip of a mass shooting at Liepaja in June 1941. See Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Trophy, Evidence, Document: Appropriating an Archive Film from Liepaja, 1941,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 36, no. 4 (2016): 509–28, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2016.1157286. Another source for moving images is the film fragment documenting a pogrom in Lwow in 1941, which the American prosecutors first screened during the Nuremberg trial in 1945. It can be seen, restored and in slow motion, in the French documentary SHOAH, LES OUBLIÉS DE L’HISTOIRE (F 2014, German title: DIE GRAUEN DER SHOAH; DOKUMENTIERT VON SOWJETISCHEN KAMERAMÄNNERN) by Véronique Lagoarde-Ségot. However, most historical images are photographs taken by German soldiers with their private cameras despite prohibitions. The prints of these seem to have been popular souvenirs or trophies among servicemen at the time. See, e.g., Kathrin Hoffmann-Curtius, “Trophäen in Brieftaschen. Fotografien von Wehrmachts-, SS- und Polizeiverbrechen,”, in Dinge. Medien der Aneignung – Grenzen der Verfügung, ed. Gisela Ecker et al. (Königstein: Ulrike Helmer, 2002), 114–35; Frances Guerin, Through Amateur Eyes: Film and Photography in Nazi Germany (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012), 37–92.

- 5See, e.g., Robert H. Abzug, Inside the Vicious Heart. Americans and the Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camps (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985); GIs Remember: Liberating the Concentration Camps, ed. National Museum of American Jewish Military History (Washington D.C.: National Museum of American Jewish Military History, 1993); Remembering Belsen: Eyewitnesses Record the Liberation, ed. Ben Flanagan and Donald Bloxham (London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2005).

- 6In 1986, Irmgard von zur Mühlen published the complete 30-minute-long liberation footage that she had found on site in her documentary DIE BEFREIUNG VON AUSCHWITZ (THE LIBRATION OF AUSCHWITZ), which includes this scene. The documentary also includes interview sequences with Aleksander Vorontsov, the only cameraman who had filmed in Auschwitz in 1945 who was then still alive. Cf. Irmgard and Bengt von zur Mühlen, Geheimarchive und Sperrgebiete. Mit der Kamera auf den Spuren der Geschichte (Berlin Kleinmachnow: Chronos, 1995), 142–54.

- 7Jeremy Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust. Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012), 44–78; David Shneer, Through Soviet Jewish Eyes. Photography, War, and the Holocaust (New Brunswick, London: Rutgers University Press, 2011), 87–139; Filmer la guerre: les Soviétiques face à la Shoah, 1941–1946, ed. Valérie Pozner, Alexandre Sumpf and Vanessa Voisin (Paris: Mémorial de la Shoah, 2015), 9–50.

- 8Hicks, First Films, 157–85; Shneer, Soviet Jewish Eyes, 140–83; Filmer la guerre, 51–64. On the final phases and liberations of these camps, see Jon Bridgman, The End of the Holocaust: The Liberation of the Camps (Portland: Areopagitica Press, 1990), 18–27; Sybille Steinbacher, Auschwitz. Geschichte und Nachgeschichte (Munich: Beck, 2015), 91–107; Dan Stone, The Liberation of the Camps. The End of the Holocaust and its Aftermath (New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2015), 29–64.

- 9This is the paraphrased translation from the interview conducted in Russian from the English version of zur Mühlen’s THE LIBERATION OF AUSCHWITZ, 1986. SHOAH, LES OUBLIÉS DE L’HISTOIRE includes an edited, shortened, and restored version of the scene. However, much of the amateurishness of the performance and filming is lost. It is a mystery to me how Dan Stone could conclude that this scene has been “inscribed into the world’s consciousness” and has for decades shaped both the public’s and academics’ false notions of triumphant camp liberations. He admits that it was “an outtake” but claims that it was “inserted into the [Auschwitz] film in the 1980s.” However, the Russian film AUSCHWITZ: FILM DOCUMENTS OF THE MONSTROUSLY EVIL CRIMES OF THE GERMAN GOVERNMENT IN AUSCHWITZ of 1945 (OSVENCIM: KINODOKUMENTY O CHUDOVISHCHNYH PRESTUPLENIJAH GERMANSKOGO PRAVITEL’STVA V OSVENCIME) was simply not altered decades later nor was it released internationally again after its relatively few screenings in the immediate postwar period. Stone seems not to have seen either AUSCHWITZ or zur Mühlen’s documentary. For example, his brief description of the liberation scene is inaccurate in that he claims that all of the prisoners wear striped uniforms. Stone, 2, 29, 31, 48.

- 10MAJDANEK: FILM DOCUMENTS OF THE MONSTROUSLY EVIL DEEDS OF THE GERMANS IN THE EXTERMINATION CAMP OF MAJDANEK, IN THE TOWN OF LUBLIN (MAJDANEK: KINODOKUMENTY O CHUDOVISHCHNYH ZLODEIANIJAH NEMTSEV V LAGERE UNICHTOZHENIJA NA MAJDANEKE V GORODE LUBLIN/ Irina Setkina, SU 1944); AUSCHWITZ (Elizaveta Svilova, SU 1945); and FILM DOCUMENTS OF ATROCITIES COMMITTED BY THE GERMAN-FASCIST INVADERS (KINODOKUMENTY O ZVERSTVAKH NEMTSKO-FASHISTSKIKH ZAKHVATCHIKOV / Elizaveta Svilova, SU 1946).

- 11See, e.g. the footage of the First of May celebration in Dachau, published by the Arte series MYSTÈRES D’ARCHIVES, season 3, 2013, DVD 1.

- 12Diana Gring, “Das Massaker von Gardelegen,” Dachauer Hefte 20, no. 20 (2004): 112–26.

- 13The author’s translation from the German narration. For a transcription of TODESMÜHLEN’s narration, see Weckel, Beschämende Bilder, 611–15, on the history of the film’s production, 151–72, and on its reception in the US zone, 418–98. The narration of the film’s American version DEATH MILLS is not a literal translation from the German and sometimes sets quite a different tone.

- 14The most of the human side of the encounters would have been presented in the British atrocity film GERMAN CONCENTRATION CAMPS FACTUAL SURVEY if it had been finished at the time. The Imperial War Museum in London completed and restored it in 2014; it is now available on DVD. See Toby Haggith, “The 1945 Documentary GERMAN CONCENTRATION CAMPS FACTUAL SURVEY and the 70th Anniversary of the Liberation of the Camps,” The Holocaust in History and Memory 7 (2014): 181–97; id., “Restoring and Completing GERMAN CONCENTRATION CAMPS FACTUAL SURVEY (1945/2014), Formerly Known as MEMORY OF THE CAMPS,” Journal of Film Preservation 4 (2015): 95–101.

- 15Fuller served in the 1st US Infantry Division, which liberated Falkenau, a small subcamp of Flossenbürg. With his private camera, he had filmed the local dignitaries carrying out his commander’s order to dress and respectfully bury the corpses. This footage was published in the documentary FALKENAU, VISION DE L’IMPOSSIBLE. SAMUEL FULLER TÈMOIGNE (Emil Weiss, F 1988).

- 16The script is based on the book Band of Brothers: E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne from Normandy to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest by the historian Stephen E. Ambrose, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992); several members of the company wrote their memoirs, mostly after the miniseries was aired.

- 17The episode’s title quotes the US government’s famous series of seven propaganda films, many of them directed by Frank Capra.

- 18Unlike in the television series, they arrived one day after the US Seventh Army’s 12th Armored Division had discovered this and other subcamps in the area, https://www.scrapbookpages.com/DachauScrapbook/DachauLiberation/Kauferi… ml. See also Edith Raim, “Kaufering,” in Der Ort des Terrors. Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager, vol. 2, ed. Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel (Munich: Beck, 2005), 360–73.

- 19See https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kaufering_I_(Landsberg)_liberat…

- 20This is not an invention of gender-sensitive filmmakers; there really were female prisoners in the Kaufering subcamps. Raim, “Kaufering,” 361.

- 21This is an image based on historic photographs of Buchenwald, a variation of which can be found in most camp liberation scenes in feature films.

- 22Freight trains evacuating inmates really were abandoned near Kaufering. The scene in BAND OF BROTHERS strikingly resembles shots from the historical footage of freight cars full of corpses discovered near Dachau, the main camp of the complex.

- 23Primo Levi, If This is a Man/The Truce, trans. Stuart Woolf (Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979), 187.

- 24This and the following citations, ibid., 188.

- 25Ibid., 189, 190.

- 26It is a voice-over. Turtorro’s lips do not move on screen

- 27See Thomas Heimann, Bilder von Buchenwald. Die Visualisierung des Antifaschismus in der DDR, 1945–1990 (Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau, 2005), esp. 71–104, http://dx.doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok.1.913; the novel’s new edition includes instructive extra information on its history and effects: Bruno Apitz, Nackt unter Wölfen, expanded new edition, ed. Susanne Hantke and Angela Drescher (Berlin: Aufbau, 2012).

- 28See Karin Hartewig, “Wolf unter Wölfen? Die prekäre Macht der kommunistischen Kapos im Konzentrationslager Buchenwald,” in Die nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager – Entwicklung und Struktur, vol. 2, ed. Ulrich Herbert et al. (Göttingen: Wallstein, 1998), 939–58.

- 29See Axel Dossmann,“NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN, eine Neuverfilmung. Über die Grenzen emotionaler Erkenntnis und historischer Gerechtigkeit im öffentlich-rechtlichen Fernsehen,” WerkstattGeschichte 72 (2016): 90–2; see also William Niven, The Buchenwald Child: Truth, Fiction, and Propaganda (Rochester: Camden House, 2007).

- 30David A. Hackett, ed., Der Buchenwald-Report. Bericht über das Konzentrationslager Buchenwald bei Weimar (Munich: Beck, 1996), see 21–5, 127–35, 367–7.

- 31Earl F. Ziemke, The US Army in the Occupation of Germany, 1944–46 (Washington DC: Center of Military History, 1975), 236–9; Abzug, Vicious Heart, 45–59.

- 32NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN was one of the first films that DEFA produced in what was then the new Cinemascope, which makes the scenes shot on Buchenwald’s original Appellplatz even more impressive.

- 33The actor had been imprisoned in a concentration camp for many years as had the novel’s author, who played a small part in the film.

- 34Other sources give a different picture. In the SED’s internal power struggle between returnees from exile in Moscow and former concentration camp inmates the former quickly won the upper hand and instrumentalized the party’s trials of red kapos. According to trustworthy confessions, some Communist kapos in Buchenwald had ruthlessly liquidated political enemies and those they suspected of being “traitors.” See Lutz Niethammer, ed., Der ‘gesäuberte’ Antifaschismus. Die SED und die roten Kapos von Buchenwald (Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1994).

- 35Quoted in Heimann, Bilder von Buchenwald, 97.

- 36Ibid., 98–102.

- 37Bosley Crowther, “The Screen: Death Camp. NAKED AMONG WOLVES at 34th Street East,” New York Times, April 19, 1967.

- 38Zygmunt Kaluzynski in Polityka November 9, 1963, quoted in Heimann, Bilder von Buchenwald, 99.

- 39In the GDR, the novel was regularly read in school and the film was broadcasted on television at least once a year. All political mass organizations owned copies of the film. Heimann, Bilder von Buchenwald, 97.

- 40For example, the film starts in 1943 with one of the protagonists together with other Germans being transported to Buchenwald in a truck in the middle of the night. Apart from the fact that German political prisoners would have been deported to concentration camps much earlier, this night-time scene with its search lights, shouting SS men, and barking German shepherds reminds one of SCHINDLER’S LIST and other Holocaust movies. Dossmann, “Neuverfilmung,” 82.

- 41See Niethammer, ed., Der ‘gesäuberte’ Antifaschismus; Hartewig, “Wolf unter Wölfen?”.

Abzug, Robert H. Inside the Vicious Heart. Americans and the Liberation of Nazi Concentration Camps. New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Ambrose, Stephen E. Band of Brothers: E Company, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne from Normandy to Hitler’s Eagle’s Nest. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992.

Apitz, Bruno. Nackt unter Wölfen, expanded new edition, ed. by Susanne Hantke and Angela Drescher. Berlin: Aufbau, 2012.

Becker, Lutz. “Film Documents of Theresienstadt.” In Holocaust and the Moving Image. Representations in Film and Television Since 1933, edited by Toby Haggith and Joanna Newman, 93–101. London, New York: Wallflower, 2005.

Bridgman, Jon. The End of the Holocaust: The Liberation of the Camps. Portland: Areopagitica Press, 1990.

Crowther, Bosley. “The Screen: Death Camp. NAKED AMONG WOLVES at 34th Street East.” New York Times, April 19, 1967.

Dossmann, Axel. “NACKT UNTER WÖLFEN, eine Neuverfilmung. Über die Grenzen emotionaler Erkenntnis und historischer Gerechtigkeit im öffentlich-rechtlichen Fernsehen.” Werkstatt Geschichte 72 (2016): 77–96.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias. “Trophy, Evidence, Document: Appropriating an Archive Film from Liepaja, 1941.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 36, no. 4 (2016): 509–28. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2016.1157286.

Elsaesser, Thomas. “Returning to the Past its Future. Harun Farocki’s RESPITE.” Research in Film and History 1. https://film-history.org/issues/text/returning-past-its-own-future.

Flanagan, Ben, and Donald Bloxham. Remembering Belsen: Eyewitnesses Record the Liberation. London: Vallentine Mitchell, 2005.

Gring, Diana. “Das Massaker von Gardelegen.” Dachauer Hefte 20, no. 20 (2004): 112–26.

Guerin, Frances. Through Amateur Eyes: Film and Photography in Nazi Germany. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2012.

Hackett, David A., ed. Der Buchenwald-Report. Bericht über das Konzentrationslager Buchenwald bei Weimar. Munich: Beck, 1996.

Haggith, Toby. “The 1945 Documentary GERMAN CONCENTRATION CAMPS FACTUAL SURVEY and the 70th Anniversary of the Liberation of the Camps.” The Holocaust in History and Memory 7 (2014): 181–97.

Haggith, Toby. “Restoring and Completing GERMAN CONCENTRATION CAMPS FACTUAL SURVEY (1945/2014), Formerly Known as MEMORY OF THE CAMPS.” Journal of Film Preservation 4 (2015): 95–101.

Hartewig, Karin. “Wolf unter Wölfen? Die prekäre Macht der kommunistischen Kapos im Konzentrationslager Buchenwald.” In Die nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager – Entwicklung und Struktur, vol. 2, edited by Ulrich Herbert et al, 939–58. Göttingen: Wallstein, 1998.

Heimann, Thomas. Bilder von Buchenwald. Die Visualisierung des Antifaschismus in der DDR, 1945–1990. Cologne, Weimar, Vienna: Böhlau, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok.1.913

Hicks, Jeremy. First Films of the Holocaust. Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Hördler, Stefan, Christoph Kreutzmüller, and Tal Bruttmann, “Auschwitz im Bild. Zur kritischen Analyse der Auschwitz-Alben.” Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 63, no. 7/8 (2015): 609–32.

Hoffmann-Curtius, Kathrin. “Trophäen in Brieftaschen. Fotografien von Wehrmachts-, SS- und Polizeiverbrechen.” In Dinge. Medien der Aneignung – Grenzen der Verfügung, edited by Gisela Ecker et al, 114–35. Königstein: Ulrike Helmer, 2002.

Horstmann, Anja. “Das Filmfragment GHETTO – erzwungene Realität und vorgeformte Bilder.” In Dossier Geheimsache Ghettofilm, edited by Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung. Bonn, 2013. http://www.bpb.de/geschichte/nationalsozialismus/geheimsache-ghettofilm…

Koppermann, Ulrike. “Das visuelle Narrativ des Fotoalbums ‘Umsiedlung der Juden aus Ungarn.’ Ein kritischer Blick auf die ‘Täterperspektive’.” Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 67, no. 6 (2019): 518–27.

Krautkrämer, Florian, ed. AUFSCHUB. Das Lager Westerbork und der Film von Rudolf Breslauer/Harun Farocki. Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2018.

Levi, Primo. If This is a Man/The Truce. Translated by Stuart Woolf. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1979.

Margry, Karl. “Das Konzentrationslager als Idylle: THERESIENSTADT – EIN DOKUMENTARFILM AUS DEM JÜDISCHEN SIEDLUNGSGEBIET.” In Auschwitz: Geschichte, Rezeption und Wirkung, edited Fritz Bauer Institut, 319–52. Frankfurt: Wallstein, 1996.

Mühlen, Irmgard, von zur, and Bengt von zur Mühlen. Geheimarchive und Sperrgebiete. Mit der Kamera auf den Spuren der Geschichte. Berlin, Kleinmachnow: Chronos, 1995.

National Museum of American Jewish Military History, ed. GIs Remember: Liberating the Concentration Camps. Washington D.C.: National Museum of American Jewish Military History, 1993.

Niethammer, Lutz, ed. Der ‘gesäuberte’ Antifaschismus. Die SED und die roten Kapos von Buchenwald. Berlin: Akademie Verlag, 1994.

Niven, William. The Buchenwald Child: Truth, Fiction, and Propaganda. Rochester: Camden House, 2007.

Pozner, Valérie, Alexandre Sumpf, and Vanessa Voisin. eds. Filmer la guerre: les Soviétiques face à la Shoah, 1941–1946. Paris: Mémorial de la Shoah, 2015.

Raim, Edith. “Kaufering.” in Der Ort des Terrors. Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager, vol. 2, edited by Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel, 360–73. Munich: Beck, 2005.

Shneer, David. Through Soviet Jewish Eyes. Photography, War, and the Holocaust. New Brunswick, London: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

Steinbacher, Sybille. Auschwitz. Geschichte und Nachgeschichte. 3 rd Edition. Munich: Beck, 2015.

Stone, Dan. The Liberation of the Camps. The End of the Holocaust and its Aftermath. New Haven, London: Yale University Press, 2015.

Weckel, Ulrike. Beschämende Bilder. Deutsche Reaktionen auf alliierte Dokumentarfilme über befreite Konzentrationslager. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2012.

Ziemke, Earl F. The US Army in the Occupation of Germany, 1944–46. Washington DC: Center of Military History, 1975.