Visibility and Torture

On the Appropriation of Surveillance Footage in YOU DON’T LIKE THE TRUTH

Table of Contents

Liberated on Film

Mexican Public Health History through Film

Reel Life

Film as Instrument of Social Enquiry

Visibility and Torture

Trapped in Amber

Be Part of History

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Köthe, Sebastian: Visibility and Torture: On the Appropriation of Surveillance Footage in YOU DON’T LIKE THE TRUTH. In: Research in Film and History. Research, Debates and Projects 2.0 (2019), No. 2, pp. 1–9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14800.

"Clean" Torture: Invisibility and Strategic Visibility

So-called “clean” or “white” torture causes suffering to defenseless people, employing a style that aims to evade reconstructions, reimaginations, and acknowledgment. In the “global war on terror” waged at Guantánamo Bay and the CIA black sites, torture is neither a state of exception nor a sudden rupture of civilization, but is based on twentieth-century practices of democratic torture. Due to democracy’s constitutive need of legitimization, a growing critique of state violence, and new means of state monitoring, leading democracies invented ways to enforce false confessions and to terrorize even their own populations without leaving traces on their victims’ bodies.1 Paradigmatic examples of these techniques are isolation, sensory deprivation by exposure to bright light or darkness, sensory overload using white noise, “stress positions” in which bodies are forced to harm themselves (e.g. by being forced to stand for prolonged periods), and “waterboarding.”2 These techniques could be quickly adapted to the “war on terror,” as they are used in US national territory in migrant detention centers, in supermax prisons, and – to a certain degree – in the training of US troops. They turn the constitutive openness of human perception, sensitivity, and sociality against itself: in “clean” torture, the relationality to the world, to others, and to one’s own body does not enable the constitution of personhood, intersubjectivity, or worldliness, but inverts them painfully.3 This annihilation is deniable and strategically visible. The iconic photographs of the sensory-deprived prisoners kneeling on Guantánamo’s soil in January 2002 were not leaked by investigative journalists but rather publicized by the Department of Defense itself. Their goal is to terrorize and exert power over whole populations by claiming infinite sovereignty over surrogate victims.

In this article, I ask about the relationship between visibility and violence. Even though visibilization is legitimized as a technology of surveillance, where security is gained through knowledge, its decisive function is not epistemological, but as a mode of torture. How can visibility be violent? If this violence consists in making human beings excessively visible, and if critical filmic research usually involves enhancing visibility, how can it avoid reproducing violence? Are there modes of filmic counterhistoriography that do produce visibility differently, appropriating and reframing ambiguous source materials?

These questions are raised by the documentary YOU DON’T LIKE THE TRUTH (AU/CA/UK 2010), which was the first and only film to show surveillance camera videos from an interrogation in Guantánamo. The film does reproduce perpetrator images that violate the rights of the depicted subject, teenage interrogatee Omar Khadr, but it also strives to reframe the depicted violence, becoming an important source in the campaign for Khadr’s liberation. How are critical aesthetic, epistemic, or forensic appropriations of these surveillance images – that not only depict violence, but manifest it themselves – possible?

Visibility as Torture in Guantánamo Bay

Being detained in Guantánamo means to be incessantly visible to others. This is ensured by a technological and architectural dispositif as well as body techniques of surveillance (including totalitarian regimes of command and obedience; the immobilization of prisoners through shackles, cages, or wounds; sensory deprivation, for example by hoodings that disable the reciprocity of gazes; or withholding protective property such as blankets or clothing) and surveillance of the most intimate self-relations (showering, defecation, masturbation, self-harm, suicide). It was not for nothing that “Camp X-Ray,” the name of a now-abandoned camp, alluded to a visualization of the inside of the body.4

The ubiquitous use of surveillance cameras not only heightens the intensity of visibility, but also constitutes archives. Between 2002 and 2005, all 24,000 interrogations in Guantánamo were recorded. Until 2008, all “activities” in the camps were recorded, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Detainees have reported that there were cameras in their cells, which they found behind clocks in interrogation rooms or disguised in pens. In 2013, lawyers discovered that confidential talks with clients were being illegally bugged and that low-resolution cameras could decipher even the smallest notes.5

While the digital photographs of torture in Abu Ghraib have been excessively disseminated, it is important to understand photography and video as everyday means of exerting control. For example, the CIA produced some 14,000 photographs at their black sites. Supposedly, they contain images that “document how money was being spent”: mugshots as well as nude pictures of prisoners during their rendition and arrival at the camp.6 All prisoners went through this procedure, which was legitimized as “documentation” of their health conditions.7

In Moazzam Begg’s 2004 open letter from Guantánamo, he demands a “logical and reasonable answer” to the question of “[w]hy I was physically abused, and degradingly stripped by force, then paraded in front of several cameras toted by U.S. personnel.”8 “Stripped by force” means that the prisoners’ clothes were cut from their bodies with scissors, which articulates an ambivalent proximity to the overpowered body: on the one hand, the abducted person loses autonomy even over the process of undressing himself. On the other hand, the scissors enable perpetrators to maintain a minimal distance from the victim’s body, seemingly professionalizing the act. The process destroys forms: it rips up not only the clothing, but also its cultural logic: the process of dressing and undressing, the fitting of body and object, the temporal horizon that connects undressing and dressing. Cutting the clothes from the body not only produces total visibility of the naked body, but symbolically negates a future return to civil life.

The scene Begg describes concerns not a single “mugshot” but pictures taken by “several cameras.” The spectacularized view of his naked, bruised body is seized as a photographic trophy by multiple soldiers. The notion of being “paraded” evokes a scene in which violence is delightedly slowed down and repeated. While a parade is usually a tool used by a state to display its power to kill, here the coerced prisoners are paraded to display their impotence, defeat, and neglect – the exposure of their deficiency and shame becomes equivalent to the state’s and its agents’ power.9 This mode of subjection through enforced visibility does not take place in the registers of surveillance, security, or health. To be forced to present oneself, when one’s frail body has become a sign of someone else’s power, means to be forced to betray oneself – one of the main goals of “clean” torture.10

Samir Naji Al Hasan Moqbel has described how prisoners were forced to watch videos of other prisoners being abused; these videos were screened in “a sort of cinema room.”11 This short circuit of violence as a production, dissemination, and forced receptivity of visibility aims to destroy solidarity and sociality among the prisoners, who inadvertently invade each other’s privacy. “The most humiliating thing was witnessing the abuse of others, and knowing how utterly dishonoured they felt.”12 The geopolitical scale of the threat posed by the DoD’s images of Guantánamo’s humiliated prisoners is reproduced on a smaller scale in the camps themselves. The images address their captured audience as racialized beings that know they will be the next victims of the depicted violence and violent depiction. Forcing to see is another way to mutilate a person’s body; stealing their eyes by controlling what they do and do not see and isolating them from their body’s agency.13 As Diana Taylor puts it: “To see without being able to do disempowers absolutely.”14

Sovereign Legitimizations of Surveillance

These regimes of visibilization are officially not legitimized as subjugation, but, firstly, as security technologies of surveillance: not only to protect US soldiers physically, but also to protect them and the detainees judicially. The cameras, without their images ever being published, supposedly guarantee that the forces are following the law. In the case of Abu Zubaydah, who survived CIA torture but was heavily wounded and lost an eye while in custody, surveillance was justified by the “concern that [the CIA] needed to have this all documented in case he should expire from his injuries.” The videos of torture justify themselves as purportedly objective evidence of lawfulness, in which it is not torture that kills, but wounds without perpetrators. Resistance emerged against the surveillance of Zubaydah because the agents themselves felt monitored: “If you’re a case officer, the last thing you want is someone in Washington second-guessing everything you did.”15

Video surveillance is, secondly, legitimized epistemologically: the ephemeral interrogation becomes medially reproducible and new elements such as body language are constituted as objects of (pseudo-)research. However, the Army Human Intelligence Manual, while claiming video to be the most accurate means of recording interrogations, warns that the technology can tend to encourage “both the source and the collector [… to] ‘play to the camera.’”16 Again, surveillance relates both to the interrogatee as well as the interrogator. The manual conceives of technology not only as a means of conservation, but also as performatively inciting actions. Thus, heightened visibility is supposed not only to enable epistemic surplus value, but at the same time endanger it by enabling dissimulations.

In the case of “waterboarding,” surveillance and research have been even more closely interlinked, as physicians did not merely participate in acts of torture; after the DoD suspended the rule of “informed consent” that protects human beings from becoming research objects without instruction and consent, physicians supervised “waterboardings” systematically, gathered data, and revised the practice by designing new boards, fluids for “safer” suffocation, and liquid diets to reduce the risk of victims dying from their own vomit.17 It is no accident that generals called Guantánamo a “battle lab” and that the 2003 standard operating procedures of Guantánamo instruct soldiers “not just to do the jobs they were trained for, but to radically create new methods and methodologies.”18

Negotiating Visibility

“[P]lay[ing] to the camera” implies that victims of torture have to, as Reinhold Görling puts it, become “actors and spectators of their own destruction.”19 The cameras come to represent invisible third parties as audiences of the victim’s destruction, as well as the victim’s own communities, which will be betrayed by his fake confessions and accusations. As well as this destruction of sociality, the recordings threaten eternal repetition of the humiliation, as the Abu Ghraib photographs confirm. Additionally, surveillance enables perpetrators, to quote Görling again, “to keep something like an addressee in the cruel acts […] The camera replaces or suspends the self-referentiality of the action.”20 This is confirmed by memos describing laughing analysts watching live feeds of torture on their screens:21 instantaneous mediatization to affirmative audiences can disinhibit violence and delegate responsibility. The videos are streams of violence and subjugation that enable soldiers to kill time by staging cruel spectacles, to demonstrate group membership, or to force brutal intimacy on other bodies.

However, the mediatized involvement of third parties is not a prerogative of perpetrators, but is also appropriated by survivors. Force-feeding of hunger strikers, such as Ahmed Rabbani, was routinely filmed. When the recordings stopped, Rabbani regretted it, “as I would always describe loudly for the camera what was being done to me.”22 In exhibiting the endured injustice to the camera, the narrator can distance himself from his suffering body. Here, shame and pain do not cause isolation and desubjectivization, but become objects of a subject’s demonstration, which demands acknowledgment and aims to reassert relationality.

Another way in which prisoners inverted the very means of their oppression can be seen in the sessions where they were shown countless photos of “suspects” to identify. This display of global visual domination over various persons, together with the injunction to betray them, did not only lead to paranoia and the destruction of social relations. The isolated prisoners, separated from their kin, were touched to see the faces of their friends, families, or just of people who looked like themselves. When the Canadian Secret Service showed Omar Khadr photographs of people from the Toronto neighborhood where he grew up, “he seemed almost happy to be looking down at familiar faces.”23

Reframing Violent Visibilities: YOU DON'T LIKE THE TRUTH

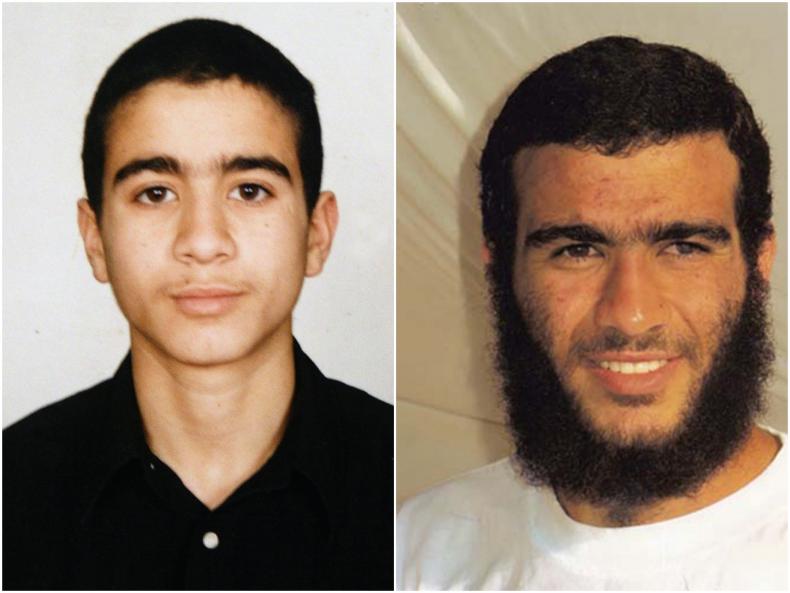

YOU DON’T LIKE THE TRUTH24 shows CCTV recordings of four days of interrogation of Omar Khadr by the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) in Guantánamo Bay in 2003. Khadr, a Canadian national from an Egyptian-Palestinian family, was left with the Afghan Taliban as a translator and child soldier by his father at the age of 1525 and was heavily wounded by two shots in his chest in a fight with US soldiers, during which he allegedly26 killed US soldier Christopher Speer. He was tortured by means such as withholding pain relief, isolation, physical violence, and threats of rape, and abducted to Guantánamo in 2002. Out of strategic considerations, he pleaded guilty to murder and other crimes in 2010 and was sentenced to eight more years of imprisonment by the military commission. Khadr was extradited to Canada, where he was released on parole in 2015 and received multimillion dollar reparations as well as a reluctant apology from his government. In 2008, a Canadian court had decided that Khadr’s constitutional rights had been violated when the CSIS interrogated him in Guantánamo. This was how he gained the rights to over seven hours of CCTV images of his interrogations. Two years after his lawyers released a ten-minute extract, YOU DON’T LIKE THE TRUTH was released, which for the first time publicized an hour of Khadr’s interrogation.

The videos show the then 16-year-old trying in vain to convince the Canadian agents of his torture in Guantánamo and to obtain help, while they try to elicit “information” about terrorist attacks. When Khadr does not say what his interrogators want to hear, they leave. The filmmakers edited a rough cut of this material, following the original order as it already “seem[ed] the work of a scriptwriter” – a statement that should alert us to the staged, dramatized, and aestheticized character of the interrogation. This rough cut was shown to experts, family members, and witnesses of Khadr’s tribulations, who were in turn filmed watching and commenting on it.

The CCTV material consists of three simultaneous phantom shots, “recordings taken from a position that a human cannot normally occupy.”27 While two of them focus on Khadr, the third is directed at the empty space between him and the interrogators. This third shot seems to manifest a potential space, securing a virtual crime scene, as if Khadr could jump over the table to attack his interrogators at any moment. While the cameras behind the interrogators’ backs expose Khadr’s side of the room, they keep them invisible by hiding their facial features, which are additionally censored by digitally inserted black blurs. While this anonymization protects the interrogators from public and judicial scrutiny, it also emphasizes their remaining expressiveness: the floundering voice of the main interrogator, his reliance on several documents to pose questions, the drumming of his fingers on the table. By fragmenting their bodies, the incoherence, effort, and contingency of their violent performance becomes palpable.

While Khadr tries to convince them that his confessions were coerced under torture, the agents reprimand him for not uttering the “truth” they want to hear. The scene shifts when Khadr lifts up his shirt to show his scarred chest, a forceful attempt to introduce a different kind of evidence. It is symptomatic of the antiforensic regime of “clean” torture that Khadr, to demonstrate his psycho-physical wounds and fragmentation, can only present war injuries, but not the subtle consequences of insufficient medical treatment, humiliation, and isolation. But while invisibility often prevents the acknowledgment of wounds, visibility does not guarantee it, as the reply of the interrogator proves: “I’m not a doctor, but I think you’re getting good medical care.”28 Khadr, still partly undressed, rejects this discourse of interrogation as care: “Nobody cares about me.” While still denying his vulnerability, the interrogators are irritated by Khadr’s resistance and parrhesia29 and flee the scene, peppering him with awkward advice that is not aimed at the boy, but instead is a performance of what Diana Taylor calls percepticide:30 “Take a break.” – “Have a little bit to eat before your hamburger gets cold.” – “Put your vest on.” – “Relax a bit.” – “Put the A/C back on.” – “That’s not true, people do care about you.” – “Put the fan on so you’re cool.” – “Put your shirt back on.” – “We’ll be back. Take a few minutes and relax a bit.” Khadr remains alone, observed by the cameras, puts his shirt back on, sobs. His chest and face slump down, his face is buried in his hands. He conceals his expression from sight. While the faces of the interrogators are protected by the sovereign manipulations of censors blurring their faces, Khadr achieves this by self-affective gestures. Whatever powers are taking effect on him, resulting from his torture, dispossession, social death, and unjust interrogation, they are claimed by his gestural withdrawal as his sole property.

Khadr’s defense had previously released the very same excerpt. The filmmakers added English subtitles that focus on its propositional dimensions. By this I mean that the style of the film does not focus on the violence of taking those images in the first place, but on the propositional meaning of what happens in them, especially of what is said. The documentary makes the scene, in the literal sense, readable. Its climax is the dramaturgically delayed subtitle “Ya ummi (Oh mother),” which is followed by a cut to Khadr’s mother and sister. Without this intelligibilization in its initial release, commentators were divided about what Khadr had said; some suggested his words were “ya ummi,” others that he had said “help me” or “kill me.” The film translates the ambiguity of Khadr’s voice into the false clarity of a single unambiguous subtitle. I want to stress that this undecidability itself has an epistemological value, since it shows a specific situatedness and sidedness of interpretative appropriations. And, more important, this undecidability is not merely a technological deficit, but essentially connected to Khadr’s sobbing. Hiding his face behind his hands, the liquefaction of mouth and nose, addressing absent or internalized persons – Khadr’s mode of expression neither addresses specific subjects nor focuses on decipherable propositions and thus cannot be adequately transcribed. His sobbing signifies above all extreme bodily intensity and self-affection. By transcribing and subtitling his expressions, the film is in danger of appropriating not the CCTV images, but Khadr’s feelings.

A news report by CBC claimed the videos to be “of poor quality […] often inaudible, as [they were] never intended to be viewed by the public”31 – this, maybe inadvertently, almost gets it right. The images are of poor quality, but not because they were never intended to be viewed by a public – they were intended for the very exclusive public of the secret services. What seems to be so hard to grasp is the idea that these images were produced for reasons other than epistemological ones. In insisting on making them readable, the documentary is in danger of losing sight of this other function. By focusing its filmic investigation on the verbal, informational, and rhetorical dimensions and not the performative violence of the image production and consumption itself, the film, as well as many commentators, buys into epistemology as ideology and cover-up of state violence as mere surveillance.

The way the documentary stages the interviewees produces a similar effect of intelligibilization. First, they are presented as silent, affected faces; then they verbally explain both their own emotions and those of Khadr. As intermediaries, they strive to represent his suffering as well as to prefigure the audience’s reaction through their own. Yet Khadr’s gestures and sounds do not aim at communication, but concealment.

“I wanted to answer, it’s just – I heard it so much later on.” What Khadr’s heartbroken mother says upon seeing the material stresses the latency between Khadr’s crying, its medial transmission, and his mother’s response, which could not have any hope of reaching her addressee. This shapes the film’s aesthetic strategy. While the film unfolds this belatedness, at the same time it works on resynchronizing it: the time Khadr has lost to war, injury, torture, and isolation is rearranged in the film’s space so that he can almost touch his mother and sister. Years of being separated and unable to communicate are condensed in the film’s parallel screens, where security camera footage and interviews shot years later constitute an aesthetic reunification of son, sister, and mother, who remain separated by a strip of black. This impression is confirmed by the only pan in the film, which leads from Khadr’s sister Zaynab to her mother, sitting next to her. It is this connection that the documentary can establish, but the surveillance cameras cannot, since there is nothing to be connected between the walls of the monitored cell.

This montage can be understood as the cinematic translation of Khadr’s desperate letters to his family: “i miss you very much and i hope i can see you in the nearast time… don’t forgat me from you pray’urs and dont forget to writ me and if ther any problem writ me. Your [heart] son:- omar [heart] khadr.”32 However, in the case of the complicated and very public Khadr family, the naturalization and privatization of family ties overly simplifies matters, since, for example, his mother and sister hurt his case by expressing public sympathy for al Qaeda. After his release, he stated that his relatives “have said things that was not very smart – that they shouldn’t have said.”33

Film as Counterhistoriography

One cannot escape the paradox of these videos: as they breach Khadr’s privacy and protect the interrogators by rendering them invisible, a critical public must voice dissent from the videos’ violent visual logic. As humiliating images that do not let Khadr withdraw from visibility, they should neither be owned nor seen. As forensic splinters of Guantánamo’s clandestine torture regime they demand contextualization and careful investigation. As evidence of Khadr’s parrhesic resistance they speak for themselves and do not need to be explained by supposed experts. We should not have seen them, but must investigate them, because they contain unatoned-for crimes. The images demand an impossible answer that is always already too late. Questions about this material should not resemble secret service epistemologies and strive for Khadr’s “true feelings” or “true knowledge,” but must decipher its visuality itself as a mode of inflicting harm and salvage Khadr’s encapsulated agency.

While the original images are made for the interrogators, the film appropriates them to transform them into forensic images and a monument to the child soldier. It remains in tension with its own source material. It not only tries to counter the violent performativity of its components, but also their epistemological and medial qualities: by overwriting them literally through the insertion of subtitles or by creating new temporal logics through montage. By making the raw material readable, the filmmakers surpass the secret service epistemologically and upgrade the violent theater of interrogation. As a result of focusing on the material’s propositional dimensions, neither the performativity of generating and perceiving the images nor Khadr’s gestural withdrawal receive adequate attention. The film’s critical appropriation and counterhistoriography remain close to the ideology of epistemological surveillance. The underexposed visual harm of torture makes it necessary to reflect not only on the verbal, performative, or physical modes of torture in the sphere of the audiovisual, but also on visibility in itself. Since the regime of torture transforms seeing and knowing, archiving and ownership into modes of violence, critical (filmic) research cannot content itself with just presenting and renarrating marginalized materials in support of minoritarian politics. The violence of visibility cannot be demonstrated without an ethical risk of one’s own, but neither may it remain hidden – whether in the dark or in overexposure.34

- 1Darius Rejali, Torture and Democracy (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2007), 1–33.

- 2For a broad study of “clean” torture from the perspective of phenomenology and theater studies, see Carola Hilbrand, Saubere Folter: Auf den Spuren unsichtbarer Gewalt (Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2015).

- 3Lisa Guenther develops this argument further in her excellent study on solitary confinement: “Persons who are structured as intentional consciousness but are deprived of a diverse, open-ended perceptual experience of the world, or who are structured as transcendental intersubjectivity but are deprived of concrete relations to others, have the very structure of their Being-in-the-world turned against them and used to exploit their fundamental relationality.” Lisa Guenther, Solitary Confinement: Social Death and Its Afterlives (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), xv.

- 4This regime of discipline also demands excessive obedience from its own guards, who are regulated by a 240-page Standard Operating Procedure, covering body and cell searches, counting systems, record keeping, and the surveillance of daily procedures such as shaving, prayers, and recreational breaks.

- 5Mark Denbeaux et al., “Spying on Attorneys at GTMO: Guantanamo Bay Military Commissions and the Destruction of the Attorney–Client Relationship,” 3, 7, 16, https://law.shu.edu/ProgramsCenters/PublicIntGovServ/policyresearch/upl….

- 6Adam Goldman, “CIA photos of ‘black sites’ could complicate Guantánamo trials,” Miami Herald, June 29, 2015, https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo….

- 7“In most cases, the detainee was stripped of his clothes, photographed naked, and administered a body cavity search (rectal examination). Some detainees described the insertion of a suppository at that time […] Mehdi said in his interview that he remains concerned about the existence of these photos.” Human Rights Watch, Delivered into Enemy Hands: US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya, 36, 89, https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/09/05/delivered-enemy-hands/us-led-abus….

- 8Moazzam Begg, “Re: Supplementary Exposition,” July 12, 2004, via The Guardian, http://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-files/Guardian/documents/2004/10/01/gua….

- 9See Elaine Scarry, The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985), 27–28, 45–51.

- 10Samir Naji, “Gitmo inmate: My treatment shames American flag,” CNN, December 11, 2014, https://edition.cnn.com/2014/12/11/opinion/guantanamo-inmate-naji/index….

- 11Moazzam Begg, with Victoria Brittain, Enemy Combatant: My Imprisonment at Guantánamo, Bagram, and Kandahar (New York: The Free Press, 2006), 112.

- 12“The prisoner’s body—in its physical strengths, in its sensory powers, in its needs and wants, in its ways of self-delight, and finally even, as here, in its small and moving gestures of friendship toward itself—is, like the prisoner’s voice, made a weapon against him, made to betray him on behalf of the enemy, made to be the enemy.” Scarry, The Body in Pain, 48.

- 13Another detainee was “forced to look at photographs of his wife’s face superimposed on images of naked women next to Osama bin Laden.” Jeffrey M. Strauss, “Family Photo,” in The Guantánamo Lawyers: Inside a Prison, Outside the Law, ed. Mark P. Denbeaux and Jonathan Hafetz (New York and London: New York University Press, 2009), 360.

- 14Diana Taylor, Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina’s “Dirty War” (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1997), 123.

- 15Scott Shane and Mark Mazzetti, “Tapes by C.I.A. Lived and Died to Save Image,” New York Times, December 30, 2007, https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/30/washington/30intel.html.

- 16“FM 2-22.3 (FM 34-52): Human Intelligence Collector Operations (September 2006),” 9–11, https://fas.org/irp/doddir/army/fm2-22-3.pdf.

- 17Physicians for Human Rights, Experiments in Torture: Evidence of Human Subject Research and Experimentation in the “Enhanced” Interrogation Program, 8, https://s3.amazonaws.com/PHR_Reports/Experiments_in_Torture.pdf.

- 18Mark Denbeaux et al., “Guantánamo: America’s Battle Lab,” 13, https://law.shu.edu/policy-research/upload/guantanamo-americas-battle-l….

- 19Reinhold Görling, “Performativität und Gewalt: Zur Destruktivität der Folter,” in Performing the Future: Die Zukunft der Performativitätsforschung, ed. Erika Fischer-Lichte and Kristiane Hasselmann (Munich: Fink, 2013), 68. My translation.

- 20Ibid., 67.

- 21Mark Denbeaux et al., “Captured on Tape: Interrogation and Videotaping of Detainees at Guantánamo,” 1315, http://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1403&context=shlr. For an in-depth treatment of the topic of the laughter of perpetrators, see Klaus Theweleit, Das Lachen der Täter: Breivik u.a. Psychogramm der Tötungslust (St. Pölten, Salzburg, and Vienna: Residenz Verlag, 2015).

- 22Ahmed Rabbani, “Affidavit of Ahmed Rabbani”, June 10, 2014, via Reprieve, https://reprieve.org.uk/press/2014_06_17_guantanamo_abu_wael_dhiab_forc….

- 23Michelle Shephard, Guantánamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr (Mississauga, ON: Wiley, 2008), 115.

- 24The film can be streamed on the official website of the Free Omar Campaign: https://freeomar.ca/videos/you-dont-like-the-truth-4-days-inside-guantanamo/. The excerpt I am focusing is from TC 00:36:10 to 00:43:28.

- 25The most detailed reconstruction of Khadr’s family history can be found in Shephard, Guantánamo’s Child, 17–68.

- 26This version is rather unlikely. A report accidentally (!) released by the US government, for instance, proves that Khadr was not the only one to survive the initial attack on the compound and thus not the only possible person who could have thrown the grenade. See Michelle Shephard, “Khadr secret document released by accident,” The Star, February 4, 2008, https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2008/02/04/khadr_secret_document_re…. For a detailed discussion of Khadr’s case, see Janice Williamson, “Introduction,” in Omar Khadr, Oh Canada, ed. Janice Williamson (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012).

- 27Harun Farocki, “Phantom Images,” in public 29: Localities (2004): 13.

- 28Luc Côté and Patricio Henriquez, “Excerpts from the Screenplay You Don’t Like the Truth: 4 Days Inside Guantánamo,” in Janice Williamson, ed., Omar Khadr, Oh Canada, 130–131.

- 29Foucault summarizes the Greek notion of parrhesia as “a kind of verbal activity where the speaker has a specific relation to truth through frankness, a certain relationship to his own life through danger, a certain type of relation to himself or other people through criticism (self-criticism or criticism of other people), and a specific relation to moral law through freedom and duty. More precisely, parrhesia is a verbal activity in which a speaker expresses his personal relationship to truth, and risks his life because he recognizes truth-telling as a duty to improve or help other people (as well as himself). In parrhesia, the speaker uses his freedom and chooses frankness instead of persuasion, truth instead of falsehood or silence, the risk of death instead of life and security, criticism instead of flattery, and moral duty instead of self-interest and moral apathy.” Michel Foucault, Discourse and Truth: the Problematization of Parrhesia: 6 lectures at University of California at Berkeley, CA , Oct–Nov. 1983, https://foucault.info/parrhesia/.

- 30“Dangerous seeing, seeing that which was not given-to-be-seen, put people at risk in a society that policed the look. The mutuality and reciprocity of the look, which allows people to identify with others, gave way to unauthorized seeing. Functioning within the surveilling gaze, people dared not to be caught seeing, be seen pretending not to see. Better cultivate a careful blindness. […] The triumph of the atrocity was that it forced people to look away – a gesture that undid their sense of personal and communal cohesion even as it seemed to bracket them from their volatile surroundings. […] People had to deny what they saw and, by turning away, collude with the violence around them.” While Taylor aims to describe the percepticide of bystanders, in this context the Canadian agents, themselves observed by the US agents through surveillance cameras, are at the same time perpetrators of violence and governed onlookers of the past violence inscribed contained in Khadr’s body. They too are in danger of transgression if they react compassionately, rescinding the binary of ally/terrorist. See Diana Taylor, Disappearing Acts, 122–123.

- 31Anonymous, “‘You don’t care about me,’ Omar Khadr sobs in interview tapes,” CBC News, July 15, 2008, http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/you-don-t-care-about-me-omar-khadr-sobs-i….

- 32Jeff Tietz, “The Unending Torture of Omar Khadr,” Rolling Stone, August 24, 2006, https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/the-unending-tortur….

- 33Michelle Shephard, “In his own words: Omar Khadr,” Toronto Star, May 27, 2015, http://projects.thestar.com/omar-khadr-in-his-own-words/.

- 34 These thoughts have been shaped by numerous discussions with colleagues and friends. I am especially thankful to have presented them at the workshop Gewaltsames Wissen: Macht und Grausamkeit in den Künsten, organized by Georg Dickmann, Barbara Gronau, and myself; at the doctoral colloquium of Iris Därmann and Thomas Macho; at the conference Gegen\Dokumentation, organized by the graduate research group Das Dokumentarische: Exzess und Entzug; and at the conference Research in Film and History: New Approaches, Debates and Projects, organized by Rasmus Greiner, Winfried Pauleit, Delia González de Reufels, and Mara Josepha Fritzsche. I am also thankful to Andrew Godfrey whose proofreading was an invaluable contribution to this article.

Begg, Moazzam. “Re: Supplementary Exposition. July 12, 2004." The Guardian.

http://image.guardian.co.uk/sys-files/Guardian/documents/2004/10/01/gua….

Begg, Moazzam, and Victoria Brittain. Enemy Combatant: My Imprisonment at Guantánamo, Bagram, and Kandahar. New York: The Free Press, 2006.

Côté, Luc, and Patricio Henriquez. “Excerpts from the Screenplay You Don’t Like The Truth: 4 Days Inside Guantánamo.” In Omar Khadr, Oh Canada, edited by Janice Williamson, 118–152. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

Denbeaux, Mark et al. “Captured on Tape: Interrogation and Videotaping of Detainees at Guantánamo.” Seton Hall Law Center for Policy and Research, February 7, 2008. http://scholarship.shu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1403&context=shlr

Denbeaux, Mark et al. “Guantánamo: America’s Battle Lab.” Center for Policy and Research, Seton Hall School of Law, January 2015. https://law.shu.edu/policy-research/upload/guantanamo-americas-battle-l….

Denbeaux, Mark et al. “Spying on Attorneys at GTMO: Guantanamo Bay Military Commissions and the Destruction of the Attorney–Client Relationship.” https://law.shu.edu/ProgramsCenters/PublicIntGovServ/policyresearch/upl….

Farocki, Harun. “Phantom Images.” In public 29: Localities (2004): 13–22.

FM 2-22.3 (FM 34-52): Human Intelligence Collector Operations (September 2006): 9–11.

https://fas.org/irp/doddir/army/fm2-22-3.pdf.

Foucault, Michel. Discourse and Truth: the Problematization of Parrhesia: 6 lectures at University of California at Berkeley, CA, Oct-Nov. 1983. https://foucault.info/parrhesia/.

Goldman, Adam. “CIA Photos of ‘Black Sites’ Could Complicate Guantánamo Trials.” Miami Herald, June 29, 2015. https://www.miamiherald.com/news/nation-world/world/americas/guantanamo….

Görling, Reinhold. “Performativität und Gewalt: Zur Destruktivität der Folter.” In Performing the Future: Die Zukunft der Performativitätsforschung, edited by Erika Fischer-Lichte and Kristiane Hasselmann, 53–72. Munich: Fink, 2013.

Guenther, Lisa. Solitary Confinement: Social Death and Its Afterlives. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Hilbrand, Carola. Saubere Folter: Auf den Spuren unsichtbarer Gewalt. Bielefeld: transcript Verlag, 2015.

Human Rights Watch. Delivered into Enemy Hands: US-Led Abuse and Rendition of Opponents to Gaddafi’s Libya. https://www.hrw.org/report/2012/09/05/delivered-enemy-hands/us-led-abus….

Naji, Samir. “Gitmo Inmate: My Treatment Shames American Flag.” CNN, December 11, 2014.

https://edition.cnn.com/2014/12/11/opinion/guantanamo-inmate-naji/index….

Physicians for Human Rights. Experiments in Torture: Evidence of Human Subject Research and Experimentation in the “Enhanced” Interrogation Program. https://s3.amazonaws.com/PHR_Reports/Experiments_in_Torture.pdf.

Rabbani, Ahmed. “Affidavit of Ahmed Rabbani.” Reprieve, June 10, 2014.

https://reprieve.org.uk/press/2014_06_17_guantanamo_abu_wael_dhiab_forc….

Rejali, Darius. Torture and Democracy. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Scarry, Elaine. The Body in Pain: The Making and Unmaking of the World. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Shane, Scott, and Mark Mazzetti. “Tapes by C.I.A. Lived and Died to Save Image.” New York Times, December 30, 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/12/30/washington/30intel.html.

Shephard, Michelle. Guantánamo’s Child: The Untold Story of Omar Khadr. Mississauga, ON: Wiley, 2008.

Shephard, Michelle. “Khadr Secret Document Released by Accident.” The Star, February 4, 2008.

https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2008/02/04/khadr_secret_document_re….

Shephard, Michelle. “In His Own Words: Omar Khadr.” Toronto Star, May 27, 2015.

http://projects.thestar.com/omar-khadr-in-his-own-words/.

Strauss, Jeffrey M. “Family Photo.” In The Guantánamo Lawyers: Inside a Prison, Outside the Law, edited by Mark P. Denbeaux and Jonathan Hafetz. New York and London: New York University Press, 2009.

Taylor, Diana. Disappearing Acts: Spectacles of Gender and Nationalism in Argentina’s “Dirty War.” Durham and London: Duke University Press, 1997.

Theweleit, Klaus. Das Lachen der Täter: Breivik u.a. Psychogramm der Tötungslust. St. Pölten, Salzburg, and Vienna: Residenz Verlag, 2015.

Tietz, Jeff. “The Unending Torture of Omar Khadr.” Rolling Stone, August 24, 2006.

https://www.rollingstone.com/politics/politics-news/the-unending-tortur….

Williamson, Janice. “Introduction.” In Omar Khadr, Oh Canada, edited by Janice Williamson, 3–50. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2012.

“‘You Don’t Care about Me,’ Omar Khadr Sobs in Interview Tapes.” CBC News, July 15, 2008.

http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/you-don-t-care-about-me-omar-khadr-sobs-i….