Mexican Public Health History through Film

The Riches of a Film Archive, 1945–1970

Table of Contents

Liberated on Film

Mexican Public Health History through Film

Reel Life

Film as Instrument of Social Enquiry

Visibility and Torture

Trapped in Amber

Be Part of History

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Gudiño, María Rosa: Mexican Public Health History through Film: The Riches of a Film Archive, 1945–1970. In: Research in Film and History. Research, Debates and Projects 2.0 (2019), No. 2, pp. 1–10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14797.

Introduction

In Mexico, the use of film for educational campaigns on hygiene and public health topics has a long history, beginning with the films made by the Ministry of Health (Secretaría de Salud) under the presidency of Porfirio Díaz in the late nineteenth century. Subsequently, in the early twentieth century, American films were used at two important moments in the history of Mexican public health. The first one came during the 1920s as a result of the Rockefeller Foundation’s health strategy in Mexico. The second came in the 1940s with Health for the Americas, a cultural and educational program aimed at farmers in Latin America that was headed by Nelson Rockefeller, Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs. Film established itself as a favored alternative for educating illiterate rural populations. One of the filmmakers to work on the program was Walt Disney, who produced thirteen short animated films.1 Due to the predominance of American films, Mexican public health educational films have remained largely unknown. The production, subject matter, and use of Mexican films are almost entirely absent from historical studies of public health by physicians and historians. Their existence was, until recently, known only from the lists of titles in some institutional books published by the Ministry of Health. Which prompted the question: if they really had existed, where exactly were they now?

After two years of attempting to request films from the Public Health Ministry Historical Archive (Archivo Histórico de la Secretaría de Salud, or AHSS),2 I was finally told in 2006 that a collection of films, including 180 cans of 16 mm and 35 mm film, had been added to their collection of written documents and photos. The film cans were labeled numerically, each number indicating a title and probable date of filming, but none of the labels had any information about the films’ content or any hint as to what sort of stories they contained. Additionally, due to unsuitable environmental conditions for preserving film and the lack of relevant experts, it was necessary for the films to be moved to the vaults at the National Autonomous University of Mexico Film Library (Filmoteca de la Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México) in late 2006.3 After they were received at the Film Library, their state of preservation was reviewed, so that deteriorated films could be removed to avoid contaminating the rest, and they were stored in properly climate-controlled vaults to await cataloguing.

The move of the films from the AHSS to the Film Library confirmed that the occasionally cited films, whose titles were only mentioned in the Bulletins and Memoirs, the official publication of the Public Health and Welfare Ministry (Secretaría de Salubridad y Asistencia or SSA) were still in existence. Naturally, this confirmation of the existence of an untouched body of audiovisual sources opened up new questions and avenues for research. What sort of films made up the Public Health and Welfare Ministry (Secretaría de Salubridad y Asistencia or SSA) collection? Were they only Mexican films? What directors, cinematographers, and producers were involved in their creation? What topics did they deal with? Were they educational or propagandistic in nature? Finally, as sources, what did the films reveal to researchers?

To answer these questions, the films needed to be catalogued.4 In the course of the cataloguing process, a significant number of films produced in Mexico were identified, offering many possible objects of study. As mentioned above, the collection comprises 180 cans of 16 mm and 35 mm film, but during the cataloguing process, several duplicates were additionally identified, along with sound reels, deteriorated films, and thirty-six foreign movies from Colombia, Argentina, Brazil, France, and the USA, confirming that films had been exchanged with other countries. Some of them are in black and white, while others are in color, the sound on most of them is reduced to simple voiceovers, and they have short run times, ranging from 10 to 25 minutes. Chronologically, they were made between 1946 and 1980.

The descriptive cataloguing process made it possible to identify public health topics and content that had been filmed for specific reasons, the names of a number of directors who worked with the institution, and features of the films’ narratives. It also allowed the educational and propagandistic intentions behind each of the audiovisual stories told on screen to be ascertained. At the end of this enriching interdisciplinary project, a previously unknown film archive had been brought to light and new sources had become available for research on the history of Mexican public health in the second half of the twentieth century.5 This article presents a detailed account of the information obtained from the cataloguing process and is organized into three sections. The first covers some general aspects of the use of film as a source in historical research on medicine and public health, with a particular focus on this institutional film archive, which has helped to revive a part of the SSA’s audiovisual memory. The second part deals with the qualitative aspects of the archive and presents several of the documentaries as examples, taking account of the historical context in which, they were filmed. The final section examines the dissemination of this film material and how some of the films have been made available on the AHSS website.

I. Film as a Source for Research and Its Role in the Study of Public Health History in Mexico

Since the 1960s, there has been methodological skepticism about the use of film in historical studies as a primary source of information about the past. Pierre Sorlin has noted the reticence among historians in the 1960s to view film as a source for historical research,6 while Marc Ferro has shown how cinema, despite over 100 years having passed since its invention, was still not seen as a valid source for historians on the grounds that it lacked precision and credibility.7 Nevertheless, films do tell stories that, although they may be made up, nonetheless provide us with cultural references concerning the society and period they depict. We should not lose sight of the fact that cinema, in order to seduce its audiences, invents things, and it would be naive to deny the importance of images in today’s world.

The analytical wealth of a film lies not only in its aesthetic quality, however, but also in its social and cultural potential. It shows us lifestyles, trends of thought and behavior, and ideologies that offer the viewer a sociohistorical window onto the time or characters portrayed on screen. As such, analysis of film does not necessarily need to focus on the work as a whole, but can instead be based on fragments of films. Taking account of the fact that films are intelligible texts that can be decoded, like any written work, it is the historian who constructs the problematic with his or her questions.8 Film on public health topics has a particular history, and the paradigms set by films from the US are a fundamental part of the development of such films in Mexico after the 1940s. As an example, historian Adolf Nichtenhauser’s manuscript A History of Motion Pictures in Medicine, which remained unfinished upon his death in 1953, is a pioneering catalogue of films produced by institutions.9 Films aimed at preventing venereal diseases have also caught the attention of researchers in the US. For instance, Allan Brandt has studied the social causes and consequences of the spread of venereal diseases among the US population from 1860 onward, and given a cinematographic, social, and educational analysis of the films FIT TO WIN (USA, 1919) and THE END OF THE ROAD (USA, 1919).10 Stacie Colwell has also analyzed THE END OF THE ROAD, but her study focuses on the film’s reception between 1919 and 1922, when it was shown in cities across the United States.11 The significance of these two films for the Mexican case is that they were used as part of the 1927 National Anti-Venereal Campaign and were shown in various Mexican states.12 As noted earlier, the Health for the Americas film series, produced by the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs under Nelson Rockefeller’s leadership, used short films from Walt Disney Productions for its program.13 The presence of these US films rendered Mexican productions practically invisible. The titles of the films were published in the mentioned Bulletins and Memoirs, but no information about their content was recorded. In the late 1950s, more complete information became available thanks to the National Lottery for Public Assistance (Lotería Nacional para la Beneficencia Pública) supporting the production of public health films. For example, 180,000 pesos was given to Cinematográfica América Unida S.A. to produce a documentary of around one thousand feet, in color, and dealing with the title: The Battle against polio. Six months later, the same amount was provided for the creation of twelve documentaries on a variety of topics, including one titled PUBLIC HEALTH.14 On July 13, 1960, representatives of Tricolor-Documentales de México, S.A. sent Dr. José Álvarez Amézquita, the Public Health and Welfare Minister, a list of technical specifications for a “professional cinematographic documentary” focusing on “rural medicine,” for which a filming budget of 150,000 pesos had already been agreed upon.15

These examples show how the Public Health and Welfare Ministry hired production companies to film their documentaries in line with the institution’s guidelines, which determined what topics were filmed, which directors and/or producers were hired, and which scripts made it to the screen. Without doubt, this relationship between the institution and film directors opens up an interesting line of research aimed at understanding how the public health campaigns and the opening of clinics were covered in films. In order to address this point, after watching and cataloguing the films and situating them in a historical space and time, it was important to search for (or to reconstruct from visual representations) aspects of public health history revealed in the short stories of real-life individuals with specific medical conditions, who, at times gratefully and at times resentfully, were cared for by the public health brigades, clinics, and professional healthcare workers.

II. The Films Begin to Speak

In the 1950s and 60s, there were three main public medical institutions in Mexico: the Public Health and Welfare Ministry, which originated in 1917 with the creation of the Public Health Department (Departamento de Salubridad Pública); the Mexican Social Security Institute (Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social, founded in 1943); and the State Employee Social Security Institute (Instituto de Seguridad Social para los Trabajadores del Estado, founded in 1959). The Public Health and Welfare Ministry established the specific agenda for the prevention and control of communicable diseases through its mobile health campaigns, which in some cases (for instance, the National Campaign for the Eradication of Malaria, (1957) were determined by the international agenda of the World Health Organization. There were also major national campaigns aimed at eradicating diseases such as onchocerciasis, pinta, and polio. The same occurred with the hospital infrastructure network, with health centers and clinics being built systematically across the country. With these two main activities leading the Public Health and Welfare Ministry agenda, the Public Health Cinematography Committee was created in 1950 to oversee the creation of institutional films.

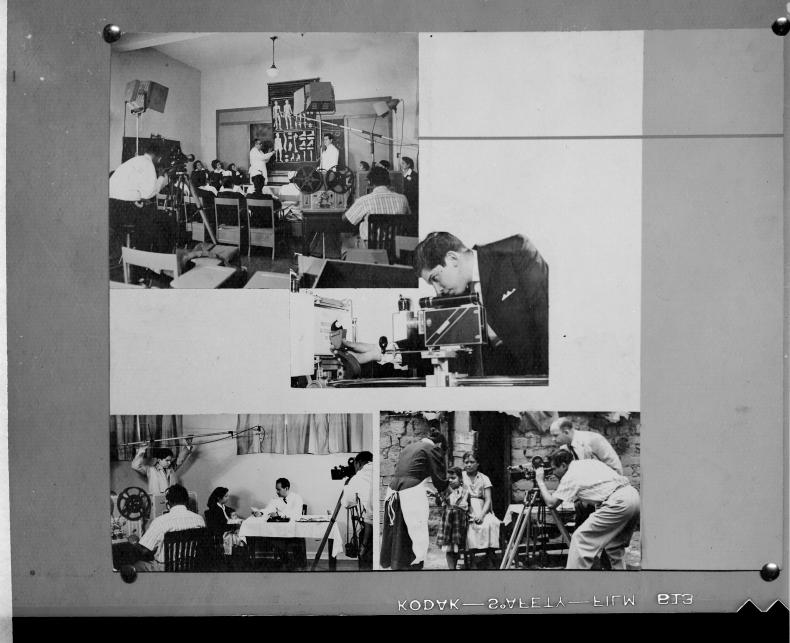

It was within this historical context that the films that comprise the AHSS collection were made. Before we examine them, it is important to first note who was behind the cameras shooting these Mexican public health stories in the service of a major government institution. The directors, cinematographers, screenwriters, and producers identified during the cataloguing process include Francisco del Villar (who has the greatest number of surviving documentaries),16 Adolfo Garnica, Demetrio Bilbatúa, and the German-Mexican Walter Reuter. These names and their film credentials open up interesting avenues for research, as some of them later became some of the most important filmmakers in Mexico, like Francisco del Villar, who went on to an interesting career in fictional cinema after his work with the Public Health and Welfare Ministry, or Demetrio Bilbatúa, who recently donated his film archive to the Ministry of Public Education (Secretaría de Educación Pública).17 Each of these filmmakers also included elements of melodrama18 in their documentaries. The documentaries show how the public health campaigns were carried out, including all of the human and material resources deployed in small communities far from Mexico City, the organization of these resources, illness maps, geographical routes, and accounts of the health workers’ jobs (including nurses, sanitarians, social workers, and engineers, though all these were generally overshadowed by the figure of the physician) and their reception in communities, as well as the health festivals and other tools used to promote health education.

As mentioned above, most of the 180 films deal primarily with recommendations for how to prevent diseases such as typhus, malaria, pinta, lead poisoning, smallpox, onchocerciasis, rabies, tuberculosis, and polio. The filmmakers also documented the suffering of the ill and the joy of the healthy. When it is considered how these images were combined with voiceovers and a musical score that sets a certain emotional tone among viewers, these films’ pedagogical nature becomes apparent.

The oldest films in the collection entitled DYSENTERY and SMALLPOX (USA, ca. 1946-1948) were produced by American filmmakers Jack Chertok (director) and Herbert D. Knapp (cinematographer) from the Office of the Coordinator of Inter-American Affairs. Both visited Mexico in 1946 and filmed several short scenes showing the sanitary and health conditions in the country. The Public Health and Welfare Ministry requested they avoid “denigrating scenes,” however, such as women at work in typical Mexican marketplaces washing their dishes in a communal water trough. These films, together with Disney’s, made up the Health for the Americas film series (produced in Mexico in the 1940s), and copies of them were included in the AHSS collection.19

Two aspects of these films are worth highlighting. On the one hand, the Americans represented themselves as the bringers of healthy habits, and as the only one’s worthy of that role. On the other, they represented Latin Americans on screen as peasants in rural settings, which, as a representation, was far from fair. To explain disease and unhealthy ways of living in Mexico, and as a justification for the films, they depicted dichotomies of happiness and sadness, cleanliness and dirtiness, hard work and laziness. The assumption that farmers were unhealthy, sad, lazy, dirty people was made to seem natural. In these American films, the Mexican government does not appear to be dealing effectively with disease in the country. This bears mentioning because the representation contrasts with the messages in the Mexican films that make up the AHSS collection, which portray the Mexican government as concerned with the health of the Mexican people. The film discourse represented on screen depicts a dynamic public health system and, ultimately, shows that the government had the infrastructure resources needed to build clinics and hospitals and employed sufficient health workers to provide care for people suffering from all kinds of diseases.

The inclusion of such aspects in the Mexican films marks a clear difference from the American films. This difference is especially pronounced in the films about the health campaigns, which present the campaigns from a top-down perspective and show the Mexican state, represented on screen by the Public Health and Welfare Ministry, bringing organization and efficiency to the health campaigns and their staff. To shed light on this structure, it is helpful to analyze two representative short films, RÍO ARRIBA (Upriver, Mexico, 1962), which deals with the National Anti-Tuberculosis Campaign, and MARTINA (Mexico, 1959), on the topic of nurse training.

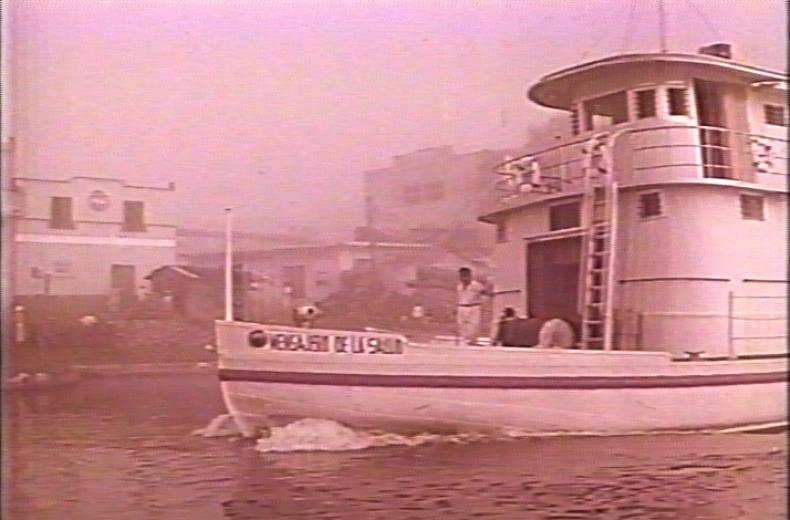

As noted above, health campaigns were highly mobile, and this was clearly shown on screen through depictions of vehicles, horses, motorcycles, and cars. The best example is RÍO ARRIBA, a film focusing on the ship El Mensajero de la Salud, which in 1962 began a journey to visit riverside towns along the Grijalva River in Tabasco State as part of a tuberculosis campaign. This documentary was funded by the National Committee for the Fight against Tuberculosis (Comité Nacional de Lucha contra la Tuberculosis, or CNLT).20 The director Adolfo Garnica and cinematographer Armando Carrillo travel to Tabasco to film on the ship. RÍO ARRIBA presents a general perspective on the workings of a health campaign that combined preventive medicine and medical treatment, and begins by showcasing the natural beauty of the region and the enthusiasm of its people. The voiceover tells the story of how the crew, led by an epidemiologist, nurses, and health educators, arrived in advance on a smaller riverboat to let the local population know that the ship, fully equipped to attend to the sick with the BCG vaccine and to offer the healthy recommendations on how to prevent tuberculosis, was on its way. The eight days that the Mensajero de la Salud remained anchored were enough for Garnica and the CNLT to show viewers the modern technology and the efficiency of the health and medical staff. It is a story of success that is told from various angles, including showing the festive reception the people gave the ship and its crew upon arrival and their thankful send-off. With regards to public health, this short film helps to counter the negative way in which the Walt Disney films from the US depicted the “unhealthy” conditions in Mexico in the 1940s. By the 1960s, when RÍO ARRIBA was filmed, Mexicans were already enjoying the benefits offered by their government.

The medical and health staff who appear in these short films are generally portrayed either completing their training or working with the public: for example, in PASOS EN LA ARENA (Footprints in the Sand, Mexico, 1960), BRIGADAS JUVENILES DE LA SALUD (Youth Health Brigades, Mexico, 1962), TRES HISTORIAS BLANCAS (Three White Stories, Mexico, 1958), and MARTINA. MARTINA presents the story of a young woman from the town of Mixtequilla in Oaxaca State, who is studying to become a nurse. With her father’s approval and the support of the town’s mayor, she goes to a health center to study, where she learns how to make hospital beds, to administer the smallpox vaccine, and to help in obstetrics. We always see this protagonist learning in classrooms and exam rooms. At the end of the course, with her diploma in hand, the young nurse returns to her town to care for her community. She makes up for the material shortages she faces with hard work. With support from the town’s mayor, Martina sets up the town clinic, makes house calls so she can remain in close contact with the townspeople and learn about their needs, works with teachers, and vaccinates schoolchildren. Through her work in the field, the townspeople come to know, love, and respect her.

In both short films, the Mexican state appears on screen, demonstrating its interest in health campaigns and promoting education and professional training for health workers by helping to increase efficiency and providing the necessary funding. These representations function as “cinematographic texts” and as political and educational propaganda for the Mexican state, reinforcing its image as a benefactor committed to the welfare of the population.

III. The Films and Their Availability to Researchers

The aim of promoting the SSA collection was more than simply to create a thematic catalogue that awaits the arrival of researchers interested in the topic. Fortunately, the work invested in the cataloguing process has already borne fruit: two studies, conducted between 2010 and 2018, have been published that utilize a number of documentaries that were recovered during this process. The first was Cien años de salud pública: Una historia en imágenes,21 which was published in 2010 to commemorate 100 years of public health in Mexico, coinciding with the Bicentennial of Mexican Independence (1810) and the Centennial of the Mexican Revolution (1910) celebrations. In addition to reprinting hundreds of photographs from a variety of national and international archives, the study also looked at ten documentaries from the AHSS. In an attempt to present a range of different aspects of Mexican public health between 1940 and 1970, documentaries on various health campaigns (typhoid fever, smallpox, pinta, rabies, etc.) and on nutrition and family planning were used. The corresponding rolls of film were cleaned and restored so they could be copied onto CDs. This process also brought to light the fact that the documentaries had been filmed in color, something that had gone undetected during the cataloguing process.

The second project was the result of the updates made to the website, which the Ministry of Health made accessible to the public.22 The site also includes thirteen documentaries selected according to institutional criteria and labeled as “antique films,” grouped under the heading “films on health.”23

Both projects have helped to publicize the existence of these films, which, with the passage of time, become an attractive audiovisual primary source for historical research. Medical infrastructure, health workers, and Mexican state development in the 1960s are some other topics represented in these films. Their images and representations allow us to recreate certain events, landscapes, and scenes connected to public health and its historical development.

Concluding Observations

Cataloguing an institutional film archive, such as the AHSS, is an opportunity to demonstrate and reaffirm that interdisciplinary work involving film archivists and historians should be an integral aspect of work with document collections in general and with film collections in particular. A combination of expertise in different areas is needed: first, the film archivist’s knowledge of the technical and production aspects of film and of its origins and state of preservation; second, the historian’s study of the context the film was produced in and of the historical period it portrays. This latter set of tasks constitutes a historical reading of the film, which makes it possible for a film to be used as a source for research or as educational material.

The results of the film cataloguing process discussed here offer a number of potential avenues for research and teaching that, while they may not do much to directly deepen our understanding of public health, do shed light on topics relating to social history, especially if we look at how health workers are portrayed, or at how women are depicted in their roles as nurses or social workers. The thematic aspects of these films set them apart from the American education films that were used from the 1920s to the 1940s, which presented an image of Mexico as a country where health conditions were very poor. The Mexican films vindicated the work of the health ministry and portrayed the nation as having the infrastructure needed to provide adequate care for the population.

Finally, in the case of this archive, the combination of cataloguing work and historical study also made a contribution by ensuring that the films will be stored in conditions suitable for their preservation, making them available for future research, and undertaking dissemination efforts to promote their later use.

- 1The use of Disney films as an instrument for hygiene education in Mexico is the topic of chapter four of my book, El María Rosa Gudiño Cejudo, Educación higiénica y cine de salud en México 1925–1960 (México, El Colegio de México, 2016). Other authors to analyze Disney films include Eric Smoodin, ed., Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom (London: Routledge, 2014), Julianne Burton-Carvajal, “‘Surprise Package’: Looking Southward with Disney,” in Smoodin, Disney Discourse, 131–147, Linda Cartwright, “Cultural Contagion: On Disney’s Health Education Films for Latin America,” in Smoodin, Disney Discourse, 169–180, Julie Prieto, “Making a Modern Man: Disney’s Literacy and Health Education Campaign in Latin and South America during WWII,” in The Pedagogy of Pop: Theoretical and Practical Strategies for Success, ed. Edward Janak and Denise Blum (United Kingdom, Lexington Books, 2013), 29–44, Rodolfo Vidal González, La actividad propagandística de Walt Disney durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial (Salamanca: Publicaciones Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, 2000).

- 2“It was officially created in 1945, although the assembly and organization of its collections had begun in 1942. In 1978, the archive’s organizational and descriptive categories were established, allowing it to consolidate itself as one of the richest historical archives in the country on topics of public health and public welfare.” On the AHSS, see also http://pliopencms05.salud.gob.mx:8080/archivo/ahssa/principal.

- 3The UNAM Film Library was founded on July 8, 1960, and it is the largest film archive in Mexico. In addition to rescuing, preserving, and restoring film material, it shares this material at a national and international level. Rafael Aviña, Filmoteca UNAM: 50 Years (México, UNAM and Dirección General de actividades cinematográficas, 2010) was published as part of the library’s fiftieth anniversary celebrations. Available online at https://issuu.com/libro_filmo/docs/filmotecaunam_libro50anos.

- 4The UNAM Film Library Cataloguing Department is headed by Angel Martínez. He and Mario Tovar provided me with all the tools a researcher could need to complete the work to a satisfactory standard and in a timely manner. I had the pleasure of learning the fascinating task of film cataloguing from them.

- 5I published an initial look at this collection in my article “Un recorrido por el acervo filmográfico de la Secretaría de Salud de México,” História, Ciéncias, Saúde-Manguinhos 19, no. 1 (Jan–Mar 2012): 325–334.

- 6Pierre Sorlin, “El cine, reto para el historiador,” Istor V, no. 2 (2005): 11–35.

- 7Marc Ferro, Historia contemporánea y cine (Barcelona: Ariel, 2000), 39.

- 8Julia Tuñón, “Torciéndole el cuello al filme: de la pantalla a la historia,” in Los andamios del historiador: Construcción y tratamiento de fuentes, ed. Camarena Ocampo and Lourdes Villafuerte (México, AGN-INAH, 2001), 341.

- 9This work was requested by the Audiovisual Training Section, the Professional Training Division, the Bureau of Medicine and Surgery, and the Department of the Navy. A copy is in National Library of Medicine. Adolf Nichtenhauser, A History of Motion Pictures in Medicine, unpublished manuscript (1953).

- 10Brandt M. Allan, No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States since 1880 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985).

- 11Colwell, Stacie, “The End of the Road: Gender, the Dissemination of Knowledge and the American Campaign against Venereal Disease during WWI,” Camera Obscura (1992), 91–125.

- 12Gudiño, Educación higiénica, 121–153.

- 13Gudiño, Educación higiénica, 158–190.

- 14“Agreement no. 1294 stipulating the contract with the ‘América Unida’ film company for the creation of the color documentaries The Battle against Polio and Public Health. Mexico, June 11, 1957,” in Lotería Nacional para la Asistencia Pública, Archivo Histórico, Departamento de Contabilidad, File H-1065.

- 15Letter sent to Dr. José Álvarez Amézquita by Ernesto Julio Teissier and Raúl Mendizábal of Documentales de México, S.A., on July 13, 1960. The letter requested a documentary filmed in Eastmancolor, in 35 mm format, and with a duration of ten minutes with twenty projection copies, ten 35 mm Eastmancolor copies, and another ten 16 mm Kodachrome copies. In Lotería Nacional para la Asistencia Pública, Archivo Histórico, Departamento de Contabilidad, File H-1065. Subject: agreements for payments relating to the national malaria eradication and public welfare campaigns.

- 16In the Public Health and Welfare Ministry collection, there are seven documentaries directed by Francisco del Villar, filmed between 1959 and 1970. Their titles are PUERTAS CERRADAS, POLVO AMARGO, LA RESPUESTA, CRUZADA HEROICA, SOMBRAS EN LA SELVA, PASOS EN LA ARENA, and UN NUEVO ROSTRO.

- 17Verónica Díaz, “Devuelvo a México parte de lo que me dio: Bilbatúa,” Milenio, May 9, 2015, https://www.milenio.com/cultura/devuelvo-a-mexico-parte-de-lo-que-me-di….

- 18Melodrama makes an emotional appeal to viewers, and it was used in pamphlets and flyers that were widely distributed in Mexico towards the end of the nineteenth century. Historian Andrés Ríos Molina remarks that “melodrama permeated film, radio, literature, comics and television, and its omnipresence still has not been the subject of widespread analysis in Mexican contexts.” Andrés Ríos Molina, “Relatos pedagógicos, melodramáticos y eróticos: La locura en fotonovelas y cómics, 1963–1979,” (México, UNAM, 2017), 263, http://www.historicas.unam.mx/publicaciones/publicadigital/libros/psiqu….

- 19Gudiño, Educación Higiénica, 153–190.

- 20The CNLT was established in 1939 as an agency to promote cooperation and social action in the fight against tuberculosis. Claudia Agostoni, “Timbres rojos y el Comité Nacional de Lucha contra la Tuberculosis, Ciudad de México 1939–1950,” Revista CONAMED 22, no. 4 (2017): 199–201.

- 21Cien años de salud pública en México: Historia en imágenes (Madrid, Secretaría de Salud, Sanofi, and Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 2010).

- 22Further general information about its collections is available at http://pliopencms05.salud.gob.mx:8080/archivo/ahssa/principal.

- 23Available at http://pliopencms05.salud.gob.mx:8080/archivo/ahssa/filmesdelasalud.

Agostoni, Claudia. “Timbres rojos y el Comité Nacional de Lucha contra la Tuberculosis, Ciudad de México 1939–1950.” Revista CONAMED 22, no. 4 (2017).

“Agreement no. 1294 stipulating the contract with the ‘América Unida’ film company for the creation of the color documentaries The Battle against Polio and Public Health. Mexico, June 11, 1957.” Lotería Nacional para la Asistencia Pública, Archivo Histórico, Departamento de Contabilidad, File H-1065.

Allan, Brandth M. No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States since 1880. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1985.

Aviña, Rafael. Filmoteca UNAM: 50 Years. México: UNAM and Dirección General de actividades cinematográficas, 2010. https://issuu.com/libro_filmo/docs/filmotecaunam_libro50anos.

Burton-Carvajal, Julianne. “‘Surprise Package’: Looking Southward with Disney.” In Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom, edited by Eric Loren Smoodin, 131–47. New York, London: Routledge, 2014.

Cartwright, Linda, and Brian Goldfarb. “Cultural Contagion: On Disney’s Health Education Films for Latin America.” In Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom, edited by Eric Loren Smoodin, 169–80. New York, London: Routledge: 2014.

Cien años de salud pública en México: Historia en imágenes. Madrid: Secretaría de Salud, Sanofi, and Centro de Investigaciones y Estudios Superiores en Antropología Social, 2010.

Colwell, Stacie. “The End of the Road: Gender, the Dissemination of Knowledge and the American Campaign against Venereal Disease during WWI.” Camera Obscura 10 (1992): 91–125.

Díaz, Verónica. “Devuelvo a México parte de lo que me dio: Bilbatúa,” Milenio. May 9, 2015. https://www.milenio.com/cultura/devuelvo-a-mexico-parte-de-lo-que-me-di….

Ferro, Marc. Historia contemporánea y cine. Barcelona: Ariel, 2000.

Gudiño Cejudo, El María Rosa. Educación higiénica y cine de salud en México 1925–1960. México: El Colegio de México, 2016.

Gudiño Cejudo, El María Rosa. “Un recorrido por el acervo filmográfico de la Secretaría de Salud de México.” História, Ciéncias, Saúde-Manguinhos 19, no. 1 (2012): 325–34.

"Letter sent to Dr. José Álvarez Amézquita by Ernesto Julio Teissier and Raúl Mendizábal of Documentales de México, S.A., on July 13, 1960." In Lotería Nacional para la Asistencia Pública, Archivo Histórico, Departamento de Contabilidad, File H-1065.

Molina, Andrés Ríos. “Relatos pedagógicos, melodramáticos y eróticos: La locura en fotonovelas y cómics, 1963–1979.” México: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 2017. http://www.historicas.unam.mx/publicaciones/publicadigital/libros/psiqu….

Nichtenhauser, Adolf. A History of Motion Pictures in Medicine, unpublished manuscript. 1953.

Prieto, Julien. “Making a Modern Man: Disney’s Literacy and Health Education Campaign in Latin and South America during WWII.” In The Pedagogy of Pop: Theoretical and Practical Strategies for Success, edited by Edward Janak and Denise Blum. United Kingdom: Lexington Books, 2013.

Smoodin, Eric Loren, ed. Disney Discourse: Producing the Magic Kingdom. New York, London: Routledge, 2014.

Sorlin, Pierre. “El cine, reto para el historiador,” Istor V, no. 2. 2005.Tuñón, Julia. “Torciéndole el cuello al filme: de la pantalla a la historia,” in Los andamios del historiador: Construcción y tratamiento de fuentes, ed. Camarena Ocampo and Lourdes Villafuerte. México: AGN-INAH, 2001.

Vidal González, Rodolfo. La actividad propagandística de Walt Disney durante la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Salamanca: Publicaciones Universidad Pontificia de Salamanca, 2000.