The Mediated Eyewitness

Voice-Overs and Modelling History

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Greiner, Rasmus: The Mediated Eyewitness: Voice-Overs and Modelling History. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–10. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14795.

The classical history film places both the aesthetic and the strategies of narration in the service of a „history effect.”1 In this way, the spectator is given the impression of experiencing history either as it takes place or after the fact. Film sound, as shown by initial research in audio history, plays a key role in this process. The intuitive, prereflexive reception of auditory and indexical similarities to familiar sounds from history evoke the feeling of sensual participation in a supposed historical reality, which in turn encounters the spectators’ film-based expectations.2 In contrast to this, many current history films are marked by the beginnings of a reflexive approach to media historiography. Combining auditory strategies of participation and bringing the past ‚to life‘ with such a layer of reflection promotes the deconstruction of intuitive processes of reception.

The starting point for my considerations is the supposition that it is precisely the fascination of the sensuality of sound that has the potential to set a process of reflection in relation to history in motion. Sound accordingly not only contributes decisively to the generation of a ‚history effect‘, but also undermines conventions of media history presentation and mediation. It virtually ‚whispers‘ to the receivers a doubt about the validity of historical ‚master narratives‘. Modern forms of voice-over narration in particular take part in this: while the authoritarian ‚voice of God‘ of classical history films still mainly confirmed its own credibility, by emphasizing on the one hand the act of narration and at the same time bridging the temporal distance between present and past, the fascination that is triggered by sound and the subjective dimension of the subjectivated voice-over in current history films opens the path for further processes of reflection.

In the following, I would like to explore this transformation of the voice-over in more detail. My central hypothesis is that narrative voices in history film no longer serve to confirm the authenticity of a presentation of history, but also generate subjectivated modellings and reflections of filmic historiography. At the same time, the importance placed on sensual aspects, for example, the sound, the „grain“ of the voice,3 and the physicality resonating therein, can be observed. While a similar development can be seen in other genres as well,4 the history film possesses a very special relevance. By including subjectivated history in (media) historical constellations and an intricate referentiality, history is modeled anew as part of a filmic historiography.

To examine these propositions and develop them further, I will look at two short animated films from 1998 and 2011 as examples for analysis. Short films are particularly well suited for studying the innovative potential of the medium, for they are often more audacious than their ‚big brother‘, the feature film, in trying out experimental approaches and presenting a reflexive take on history. Both films deal with the lives of actual individuals under Nazism and fascism in Europe. And yet the animated image builds up a distance to non-filmic reality. The stylization of the image thus increases the relevance of sound in generating an audio-visual ‚reality effect‘. This results in a condensation of auditory processes of communicating history. The “instant credibility” of film sound even has an impact on the image, which is subsequently accepted as a representation of the past. The meta-reflexive level on which the relationship between subjective and collective (media) historical and memory images is interrogated reveals the two films as standing in the tradition of a movement of renewal, which began with directors like Alain Resnais, a pioneer of the New Wave. Looking from the present to the past, the paradigm of memory from Resnais’s Holocaust film NUIT ET BROUILLARD (NIGHT AND FOG, F 1955) is taken up by these short films.

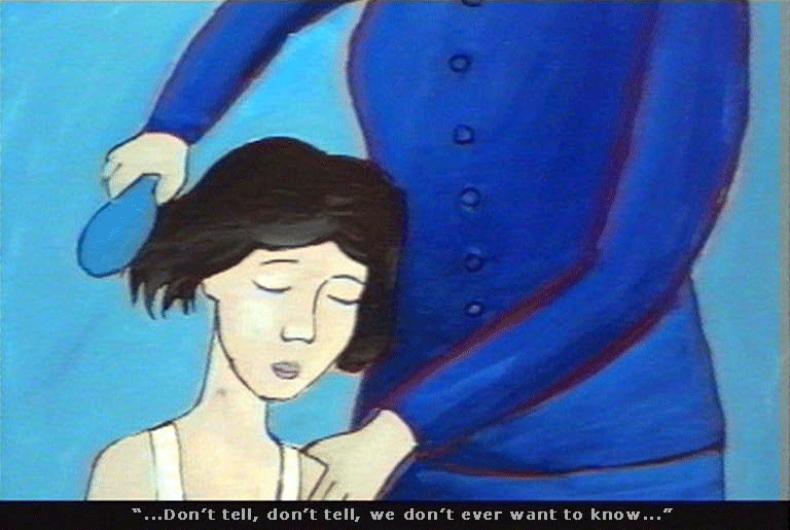

Sylvie Bringas’s and Orly Yadin’s short film SILENCE (UK 1998) reconstructs the story of the young Jewish girl Tana, separated from her mother during the Nazi period (Fig. 1) entirely in this spirit. Hidden by her grandmother in Theresienstadt, Tana survives and grows up after the war with her uncle and his family in Sweden. It is only as a young adult that she learns of her mother’s murder in Auschwitz. The most notable aspect in SILENCE is the almost complete reversal of the image-sound hierarchy. Sound is not added to the image: instead, the animation illustrates the soundtrack, by adapting to its rhythm and sound, which is defined by the music and the homodiegetic voice-over.5 Film sound creates a historical space that is associatively opened in the image.

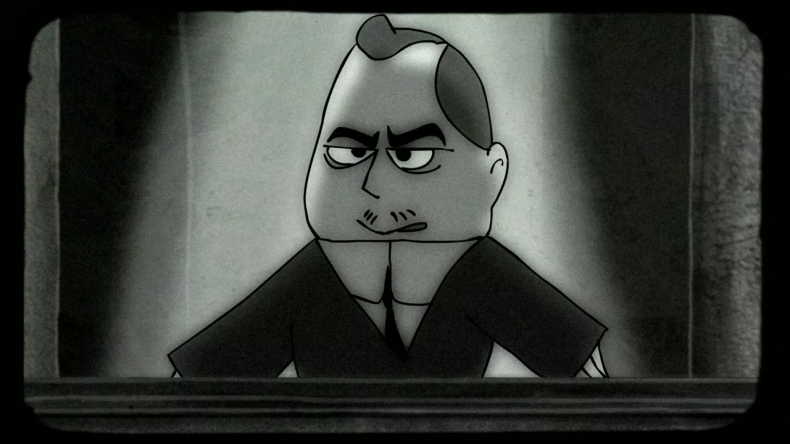

In HELDENKANZLER (Benjamin Swiczinsky, D 2011), too, the sound track takes on an independent dimension of modeling history (Fig. 2). In the field of tension between the equally homodiegetic voice-over, classical music, and a sparingly used cartoon sound, a highly ironic but historical founded view of Austrian chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß is presented. Until his murder in 1934, Dollfuß tried to establish an ‚Austro-fascist corporate state‘, seeking support from both the Catholic Church and Benito Mussolini.

Voice(s) of History

Since the start of the age of sound film, voice-over narration has been a popular technique to introduce the spectator to the plot. In monumental cinema, the ‚Voice of God‘ underscores the authority of the implicit presenter and underscores the distance to be bridged between the present and the past.6 In modern history film, the ‚voice of God‘ is being replaced by a ‚subjectivated voice-over‘. In contrast to the traditional, apparently infallible ‚voice of history‘, which was usually provided by famous actors and directors (including Orson Welles, John Huston, Spencer Tracy),7 these subjectivated narrative voices can also present colored perceptions and judgments on historical events. As an element of this, there is a shift from the use of the third to the first person. The narrative voice becomes human and thus fallible—sometimes it is even a part of a self-reflexive play with the speaker’s unreliability, approaching strategies of modern documentary and essay film.

The voice-over in HELDENKANZLER thus does not represent an authoritarian narrative figure, but rather is a subjective commentary that lends expression to Engelbert Dollfuß’s naïve fantasies of power. In contrast to the figure’s speech, where the protagonist almost exclusively produces onomatopoetic word fragments (grammelot), in the voice-over he is able to articulate normally. While the narrator mimes the role of the implicit presenter, the squawking voice, its strong Lower Austrian accent, and the exaggerated, pathos-laden emphasis on every single syllable mark it as a caricature.

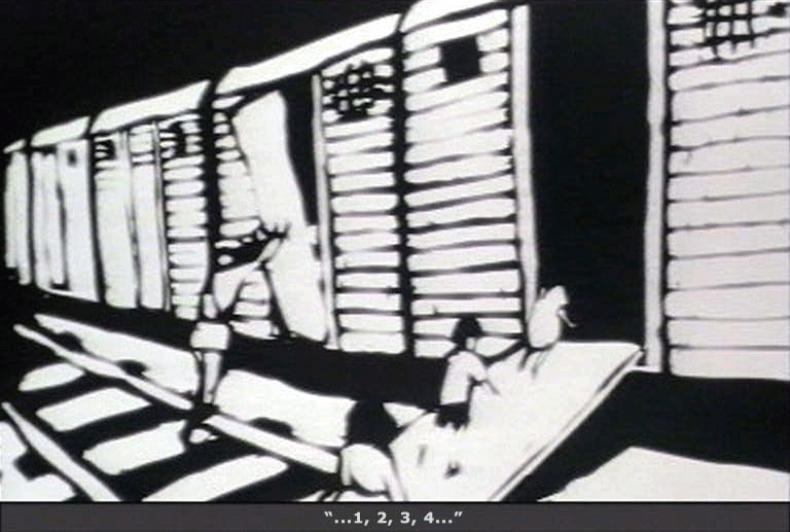

While during the voice-over in HELDENKANZLER the discrepancy between form and content takes on a comic effect, in SILENCE it flanks the subjectively colored modeling of history. For example, the whispered counting of the children in Theresienstadt is combined with the motif of the deportation train (Fig. 3). The situation of permanent threat that is lived through once again many years later over and over is reflected in the narrative voice. Very much in the sense of Michel Chion’s term „synchresis“8, id est the fusion of a sound event with an image event, in later sequences whispered counting is sufficient as a reference to this trauma. The same is true of the whistling and wheezing of a steam locomotive and the screech of the brakes - typical train sounds that with Tana’s arrival in Sweden anticipate a visual metaphor for the Holocaust: a conductor looks through the wagon door of the train and morphs in that very moment into a uniformed SS man. In black-and-white images, the shadows of the past break forth. But even in such subjectivated, imaginative sequences, filmic reality remains consistent and credible.

The use of a female narrative voice, however, counters the decades of paternal domination in the classical Hollywood film. In that the narrative voice of a woman of advanced age generates the impression that she experienced the events described and recalls them to memory together with the spectator, it operates beyond the undemocratic paternalism of the classical history film.9 By using the first person singular, the preceding statement „This is my story“, and by voicing all the figures, a subjectivated perspective is taken from the very beginning. In addition, the direct address of the spectator eases identification with the protagonist and allows for deep emotional participation.

But it is not the dissolution of the historical process of meaning, but the problematization of access to history that stands at the focus of the film. The specific rhythm and the complementary relationship of images and speech acts generate a narrative current of lived history: a time-image.10 The subjectivation of the voice-over narration can be understood in the sense of a ‚stream of memory‘. In contrast to the primarily literary model of the ‚stream of consciousness‘, the ‚stream of memory‘ is more like a structured narration than an interior monologue. The various channels of perception are here linked to one another, which confirms Michel Chion’s thesis „that one perception influences the other and transforms it.“11 SILENCE accordingly deals with processing partly suppressed traumatic experiences. The voice-over here takes on an additional dimension. By quoting from letters from the mother, it adds another facet to Tana’s biography and accentuates history’s multivocality. The overlapping, animated images of the struggle for survival in Germany and her uncle’s work as a conductor in Sweden are fused by the stirring orchestral music and the voice-over. Movement through space is precisely matched by the sound. This forms a sound carpet „that formulates an emotional appeal under the surface, via the prosodic characteristics of rhythm and intonation as well as the sound characteristics of voice,“ but, historically considered, can only lose its impact.12 The final applause is followed by the whistling and hissing of a steam locomotive, then there is silence. The visually communicated trip through the gate of the concentration camp Auschwitz and the voice-over information on the death of the mother confirm what was previously suggested by the soundtrack.

Materiality and Aesthetics

Listening is not just temporally located, but also a spatial-sense that is addressed deliberately by film. Film sound also gives the spectator ‚materializing sound indications‘ and lends the filmic world a certain materiality.13 As Barbara Flückiger puts it, „[t]he film image dematerializes objects, while sound returns them their physicality.“14 In other words, film sound replaces tactile sensory perception: listening makes the materiality of the filmic world palpable, evoking associations and triggering emotions.15 This also influences the reception of voice-over narration, since the human voice can be understood as the intersection between the production of meaning and physicality.16

In HELDENKANZLER, there are even mutual interactions between materializing sound and the voice-over narration. The first-person narrator explains to edited archive images of shooting soldiers and dead political enemies: „A wonderful day: No Communists, no Socialists, and no other riff-raff were left in my way to keep me from realizing my dream of a Christian-Austrian corporatist state. I was never before so happy to see your eminence [Benito Mussolini].“ Dollfuß’s absolutely distorted perception of the horrific reality seems deeply cynical when combined with the image: an impression that is amplified by the soundtrack. From the background, a threatening humming sound mixes with the echoing, irregular steps of soldier boots. While in the image the perpetrators walk by their victims, the acoustically mediated hardness of the ground can be associated with the harshness of dictatorship (fig. 4).

An even greater importance is placed on the specific materiality of the historical, which the viewer/listener sites in the sound track. Birger Langkjær emphasizes that sound in film need not agree with sound in reality. Instead, at issue is triggering the same perceptive processes that take place in perceiving non-media reality.17 For the history film, we can expand this theory still further: since the sounds generated by the film in the rarest of cases can be compared to the non-media ‚original‘, the spectator is forced to recall his or her memory, which in turn is often influenced by film impressions.18 In many history films, the goal is to trigger the same perceptive processes that take place in the reception of film documents, categorized in the memory of the spectator as historically credible. The viewer is to be placed in the mode of a ‚documentarizing reading”.19 Friedrich Kittler’s hypothesis of the „noise of the real“ is very useful for understanding the mechanisms behind this concept. Kittler proposed that not only the sensible, but everything else - even what is generally considered a disturbance - finds its way into film.20 In other words, the technical media transform both consciously selected elements of profilmic reality as well as the coincidental, coded as noise. Many current history films seek to evoke the „noise of the real“ by imitating old film stock and apparent technical defects.21 HELDENKANZLER uses this very strategy. The typical cracking, sizzling, and slight hiss of the sound is visually complemented with digitally created scratches and dust. The old German writing and the metallic appearance of the title’s surface takes its inspiration from the style of propaganda films such as TRIUMPH DES WILLENS (TRIUMPH OF THE WILL, Leni Riefenstahl, D 1935).

This pathos-laden audiovisual presence of the historical that refers by way of simulated disturbances to historical film documents and feature films is contrasted to the pathetic physical presence of the main character. Dollfuß is small and unshapely. In acoustic terms, his awkwardness is underscored by unarticulated sounds such as throat clearing and humming. In addition, there is the squawking voice of the voice-over commentary coupled to the visible body. Kaja Silverman here speaks of an „embodied voice-over“, which in contrast to the disembodied voice is weakened in its authority, virtually emasculated.22 The acoustically communicated, shameful choking of the historical figure takes the audiovisual exaggeration strategies borrowed from film propaganda to absurd levels. The resulting self-reflexive refraction makes us aware of the previously triggered ‚history effect‘ and places the spectator in a discursive relation to a filmically mediated historicity.

Referentiality and Historical Echo

In its original use, the term ‚post-memory‘ refers to the phenomenon of children of Holocaust survivors ‚remembering‘ the experiences of their parents as narratives and images with which they grew up.23 The place of parental memory has now been taken by media representation.24 Feature film here plays a special role, for it transforms archive images and generates image stereotypes all its own. Silvie Lindeperg calls the intertextual play of quotations and counter-quotations generated in this way an „echo-cinema“, using a concept that already refers to sound.25 In fact, historical sound stereotypes and sound metaphors have taken hold. In place of the original sounds, media sounds are remembered, so that we can speak of a media ‚echo‘ of history. In many cases, all that is necessary is a small acoustic impulse to trigger long chains of memory and association. In the following, I will call these sound impulses ‚reminiscence triggers‘. The principle is the same as in Marcel Proust’s novel À la recherche du temps perdu (1913-1927), where the taste of a madeleine dissolved in tea triggers the sensual resurrection of childhood memories. The cognitive links to historical processes and events triggered by sound in history film go far beyond the information of the affective memory. While the understanding of a ‚reminiscence trigger‘ requires membership in a certain socio-cultural community, the globalized film and media market is constantly enlarging the international understanding. Especially in recent history films, far-reaching migration movements of sounds can be registered, that also develop a parodic potential. For example, the title melody of HELDENKANZLER is clearly similar to the fanfares of the Nazi weeklies. The sound track, however, soon raises doubts about the seriousness and dependability of the supposed historical film document. The music piece outdoes itself with elaborate pseudo-bombast that culminates in a dissonant ‚grinding down‘ caused by the temporary slowing of the playback tempo.

An example that is even clearer than this quite simple reference to the sounds of the past is Dollfuß’ speech before the Austrian parliament (Fig. 5): while on the one hand there is a clear similarity to original recordings of Adolf Hitler’s appearances at Nazi party rallies - the „sonic icon“26 of Hitler’s voice and the celebratory jubilation of the masses. The reverberating acoustics refer to the monumental architecture of the space: in addition, the perspective from below, the strong contrasts, slight camera movements, and rounded corners of the image evoke associations with newsreels shots and the film of a Nazi party convention TRIUMPH DES WILLENS (Fig. 6). On the other hand, key work of film history serves here as a reference. Just like in Charlie Chaplin’s THE GREAT DICTATOR (USA 1940), Dollfuß’s address is an aggressively presented mixture of indecipherable, in part onomatopoetic word fragments (Fig. 7). The specific listening experience of ‚grammelot‘ can serve in turn as a reminiscence trigger with the help of which the historical reference is called to memory. The effect of parody is also amplified by the fact that in contrast to Hitler and even Chaplin, Dollfuß doesn’t have his audience under control and in the end is even laughed at.

In SILENCE, this multi-dimensionality of media history is built up already in the very first sequence. The archival shots from the Nazi period are provided with music that recalls the piano accompaniment of silent films. The film is charged with a media-historicity from the very start. When the voice-over reports the fate of Tana’s mother, a silhouette-like photograph of a woman with a baby is moved before the archival images. But synchronous with the statement that the mother has left Tana, the face of the woman dissolves into an animated cloud of smoke. The wooden wall rushing through the image, also in animation, can only be understood as a sign for the filmic motif of deportation in combination with the sound - the sound of train and the voice-over commentary „soon everybody else was gone“. The sound metaphor serves as a reminiscence trigger with the help of which memories of deportation scenarios from other films can be evoked. Borrowing from Tobias Ebbrecht’s considerations on the visual aesthetic of the Holocaust film, we can conclude that since the early 1990s a sound aesthetic has developed „that is no longer based directly on historical events“27, but refers to a tradition of sounds and narrative. This development takes place proportionally to the gradual ‚extinction‘ of the eyewitnesses who could have described the original sounds, noises, and soundscapes. At the same time, fictive narrators take their place by operating in the mode of mediated eyewitness.

Summary

The prereflexive reception of sound in historical film evokes a feeling of direct sensual participation in the past. But the current history film not only generates a ‚history effect‘, but also subjects it to a critical reflection by way of the voice-over or remediation using visual or sound documents. This play with the supposed ‚instant credibility‘ of sound generates doubt as to the certainty of media-produced history. The imitation of the physical-material qualities of historical sound documents serves frequently not just to trigger a documentarizing reading, but also proves to be a force of modeling history by which continuity can be provided, fissures are marked, and self-reflexive impulses can be provided. A ‚historicizing echo‘ makes us aware of various dimensions of (media) historicity. In this way, a sound object can be linked to certain historical events, processes, and eras, but also to media forms of usage and contexts of meaning, to trigger among the spectators far reaching chains of remembrance and association. Such a ‚reminiscence trigger‘ has the potential impact of an auditory ‚punctum‘ by triggering fascination, interest, and emotions. The voice-over narration as an outstanding element of the soundtrack can thus be linked to historical references. The narrative voice serves furthermore in numerous current historical films as an expression of an autonomous historical dimension of the soundtrack. The ‚voice of God‘ of monumental film is replaced by a subjectivated voice-over that liberates an enormous imaginative power, but is also fallible and human. Together with the use of a female narrative voice, this ‚humanization‘ ends the undemocratic paternalism of the ‚voice of God‘ in the classical history film. The spectator enters into a discursive relation to the voice-over narration that represents no longer ‚the‘, but ‚a‘ voice of history. The fictive voice-over narrator here takes on the role of a mediatized eyewitness. The tendency towards subjectivation leads furthermore to a valuation of the physical-sensual dimension of sound and the grain of the voice which ultimately generate in the spectator a reflexive relationship to the content. The relationship between the auditory and the visual levels of current history films thus needs to be reconceived. The emancipation of film sound and the subjectivation of the voice-over make the image, which can be understood as pre-reflexive as a representation or even reproduction of reality, becomes legible as a form of the aesthetic. Its potential to model history is thus the result of a discursive process of negotiation between the various layers of image and sound, film, and the spectator.

- 1Vivian Sobchack describes the “history effect as an experiential field in which human beings pretheoretically construct and play out a particular—and culturally encoded—form of temporal existence.” Vivian Sobchack, “‘Surge and Splendor’: A Phenomenology of the Hollywood Historical Epic,” in Film Genre Reader III, ed. Barry Keith Grant (Austin 2007), 300.

- 2Rasmus Greiner and Winfried Pauleit, “Audio History des Films: Eine Forschungsskizze,” Nach dem Film 14: Audio History, accessed March 13, 2015, https://www.nachdemfilm.de/issues/text/audio-history-des-films.

- 3See Roland Barthes, “The Grain of the Voice,” in Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York 1978).

- 4Cf. Christina Heiser, Erzählstimmen im aktuellen Film: Strukturen, Traditionen und Wirkungen der Voice-Over-Narration (Marburg 2014), 123, 133, 335.

- 5“Homodiegetic” means that an ego narrator speaks from the perspective of a figure in the image; cf. ibid., 280–283.

- 6See Sobchack, “‘Surge and Splendor,’” 297.

- 7Ibid., 296.

- 8See Michel Chion, Audio-Vision, trans. Claudia Gorbman (New York 1994), 63–64.

- 9Cf. Kaja Silverman, The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema (Bloomington 1988), 51.

- 10See Gilles Deleuze, The Time Image: Cinema 2, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Caleta (Minneapolis 1989).

- 11See Chion, Audio-Vision, xxvi.

- 12See Barbara Flückiger, Sound Design: Die virtuelle Klangwelt des Films (Marburg 2001), 364. (Transl. B.C.).

- 13Cf. Chion, Audio-Vision, 114–117.

- 14See Flückiger, Sound Design, 330. (Transl. B.C.).

- 15Ibid.

- 16Cf. Silverman, The Acoustic Mirror, 44.

- 17Cf. Birger Langkjær, “Making Fictions Sound Real: On Film Sound, Perceptual Realism and Genre,” MedienKultur 48 (2010): 10.

- 18See Chion, Audio-Vision, 108.

- 19See Roger Odin, “Dokumentarischer Film, dokumentarisierende Lektüre,” in Bilder des Wirklichen: Texte zur Theorie des Dokumentarfilms, eds. Eva Hohenberger and Judith Keilbach (Berlin 1998), 259–275.

- 20Cf. Friedrich Kittler, Grammophon/Film/Typewriter (Berlin 1986), 26.

- 21Ibid.

- 22Cf. Silverman, The Acoustic Mirror, 53f.

- 23Cf. Marianne Hirsch, “Surviving Images: Holocaust Photographs and the Work of Postmemory,” in Visual Culture and the Holocaust, ed. Barbie Zelizer (New Brunswick 2001), 218.

- 24Cf. Tobias Ebbrecht, “Sekundäre Erinnerungsbilder: Visuelle Stereotypenbildung in Filmen über Holocaust und Nationalsozialismus seit den 1990er Jahren,” in Medien – Zeit – Zeichen: Beiträge des 19. Film- und Fernsehwissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums, eds. Christian Hißnauer and Andreas Jahn-Sudmann (Marburg 2007), 39.

- 25Cf. Silvie Lindeperg, “Spuren, Dokumente, Monumente: Filmische Verwendungen von Geschichte, historische Verwendungen des Films,” in Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit: Dokumentarfilm, Fernsehen und Geschichte, eds. Christian Hißnauer and Andreas Jahn-Sudmann (Berlin 2003), 68.

- 26Brian Currid, A National Acoustics: Music and Mass Publicity in Weimar and Nazi Germany (Minneapolis 2006), 102.

- 27Ebbrecht, “Sekundäre Erinnerungsbilder,” 38. (Transl. B.C.).

Barthes, Roland. “The Grain of the Voice,” in Image, Music, Text, trans. Stephen Heath (New York 1978).

Chion, Michel. Audio-Vision, trans. Gorbman, Claudia (New York 1994).

Currid, Brian. A National Acoustics: Music and Mass Publicity in Weimar and Nazi Germany (Minneapolis 2006).

Deleuze, Gilles. The Time Image: Cinema 2, trans. Tomlinson, Hugh / Caleta, Robert (Minneapolis 1989).

Ebbrecht, Tobias. “Sekundäre Erinnerungsbilder: Visuelle Stereotypenbildung in Filmen über Holocaust und Nationalsozialismus seit den 1990er Jahren,” in Medien – Zeit – Zeichen: Beiträge des 19. Film- und Fernsehwissenschaftlichen Kolloquiums, eds. Hißnauer, Christian / Jahn-Sudmann, Andreas (Marburg 2007).

Flückiger, Barbara. Sound Design: Die virtuelle Klangwelt des Films (Marburg 2001).

Greiner, Rasmus / Pauleit, Winfried. “Audio History des Films: Eine Forschungsskizze,” Nach dem Film 14: Audio History, accessed March 13, 2015, http://www.nachdemfilm.de/content/audio-history-des-films.

Heiser, Christina. Erzählstimmen im aktuellen Film: Strukturen, Traditionen und Wirkungen der Voice-Over-Narration (Marburg 2014).

Hirsch, Marianne. “Surviving Images: Holocaust Photographs and the Work of Postmemory,” in Visual Culture and the Holocaust, ed. Zelizer, Barbie (New Brunswick 2001).

Kittler, Friedrich. Grammophon/Film/Typewriter (Berlin 1986).

Langkjær, Birger. “Making Fictions Sound Real: On Film Sound, Perceptual Realism and Genre,” MedienKultur 48 (2010).

Lindeperg, Silvie. “Spuren, Dokumente, Monumente: Filmische Verwendungen von Geschichte, historische Verwendungen des Films,” in Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit: Dokumentarfilm, Fernsehen und Geschichte, eds. Hißnauer, Christian / Jahn-Sudmann, Andreas (Berlin 2003).

Odin, Roger. “Dokumentarischer Film, dokumentarisierende Lektüre,” in Bilder des Wirklichen: Texte zur Theorie des Dokumentarfilms, eds. Hohenberger, Eva / Keilbach, Judith (Berlin 1998).

Silverman, Kaja. The Acoustic Mirror: The Female Voice in Psychoanalysis and Cinema (Bloomington 1988).

Sobchack, Vivian. “‘Surge and Splendor’: A Phenomenology of the Hollywood Historical Epic,” in Film Genre Reader III, ed. Grant, Barry Keith (Austin 2007).