Historical Turns

On CALIGARI, Kracauer and New Film History

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Baer, Nicholas: Historical Turns: On CALIGARI, Kracauer and New Film History. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14785.

The advent of New Film History a quarter-century ago was preceded by a far earlier “historical turn.” Challenging natural law theory, with its appeal to the atemporal and universal aspects of human nature, nineteenth-century German historicism had asserted the historicity and uniqueness of all sociocultural phenomena and values. The legacy of Leopold von Ranke and the Historical School has extended into the field of Cinema and Media Studies over the past three decades, as film scholars have promoted a greater historical consciousness. Whereas apparatus theory of the 1970s presumed a basic uniformity and historical continuity in cinematic style and spectatorship,1 more recent work has emphasized the 'historicity' of moving images, from their conditions of production to their contexts of reception, and has examined large-scale transformations in technology and modes of sensory perception and experience.

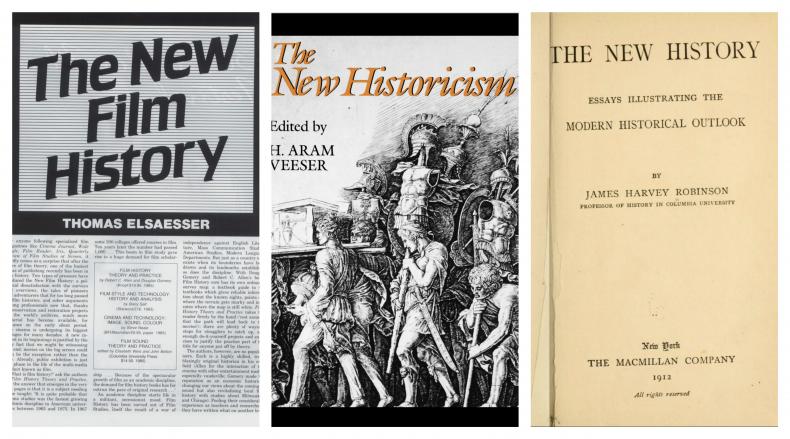

Of course, an analogy between the “historical turn” in nineteenth-century German scholarship and that of Film Studies in the 1980s is an imperfect one. The term “New Film History,” as popularized by Thomas Elsaesser in a 1986 article, recalled not only the rising New Historicism in literary studies, but also the “New History” championed in the early twentieth century by James Harvey Robinson, who had critiqued prior historiography for its narratives of preeminent political figures and events.2

The phrase “New History,” or “nouvelle histoire,” emerged again in the 1960s and 1970s with a generation of American and French scholars who harkened back to Progressive historians (Robinson, Charles A. Beard) and the Annales School founders (Lucien Febvre, Marc Bloch) in expanding the purview and methods of the historical sciences and in foregrounding economic and social forces.3

Books such as Robert C. Allen and Douglas Gomery’s Film History: Theory and Practice (1985) arguably continued these trends in approaching cinema as an open system shaped by artistic, technological, economic, and social factors.4

If New Film History thus followed the New History movement and the Annales School in diverging from nineteenth-century German historiography, film historians nonetheless upheld many central ideals of the Rankean tradition, including primary-source research, scientific exactitude, and objective, detached neutrality. In both cases, one also witnessed a time lag between the formation of an academic discipline and the crystallization of its problems. Much as German intellectuals increasingly recognized the aporias of historicism, culminating in a crisis of historical thought in the early twentieth century, recent years have witnessed heightened reflection on the “historical turn” in Cinema and Media Studies and on the histories of film historiography and theory. This reflection has occurred against the backdrop of dizzying shifts in our global media environment, which have radically expanded our resources for producing film scholarship but have also called into question the very centrality, autonomy, and stability of our object of study, threatening it with obsolescence.

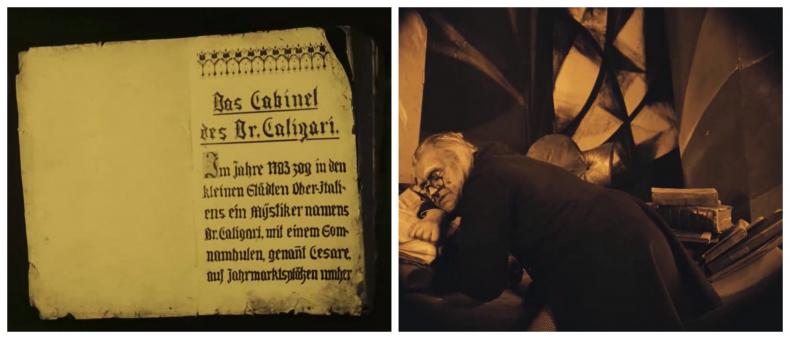

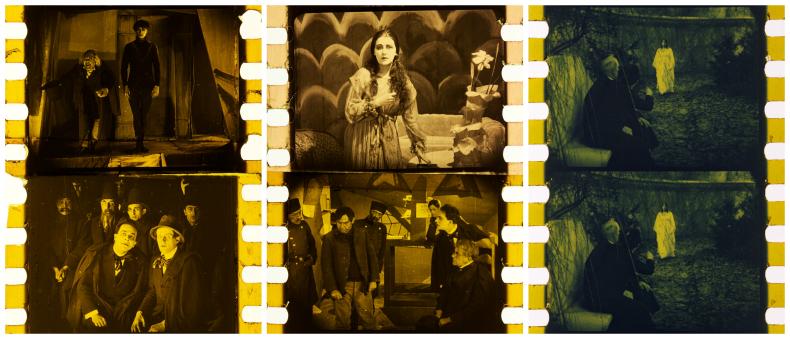

In the broader book project of which this paper is part, I attempt to rethink the tenets of New Film History by examining the “crisis of historicism” widely diagnosed by German intellectuals a full century ago. My project focuses on pioneering and influential films of the Weimar Republic, which, I argue, engaged with contemporaneous metahistorical debates, offering aesthetic responses to ontological and epistemological questions of the philosophy of history. In my analysis, many of Weimar cinema’s defining formal and stylistic features (e.g., non-linear narratives, Expressionist 'mise en scène') can be interpreted as figurations of historical-philosophical issues, including the structure and directionality of history and the possibility of objective cognition. Moreover, numerous films of the period developed strategies to break with historicist thinking altogether, whether in the non-referentiality of avant-garde abstraction or in the alternative temporal frameworks of nature, religion, and myth. In this way, Weimar films issued a critique of nineteenth-century historical methodology and are thus at odds with the objectivism and empiricism of much new film-historical scholarship. The present essay will give a brief account of the “crisis of historicism” and use Robert Wiene’s DAS CABINET DES DR. CALIGARI / THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI (D 1920) to illustrate my larger argument.

The Crisis of Science

While the positivism popularized by Auguste Comte in the nineteenth century made an enormous contribution to emerging disciplines such as history and sociology,5 the extension of naturalist postulates to the Geisteswissenschaften (humanities) raised many vexing questions for intellectuals in Central and Western Europe: might not human life and activity bear unique, vital, and dynamic qualities, ones that are obscured when social existence and behavior are treated like objects of natural-scientific scrutiny? Are there dimensions of humankind’s being, interiority, and lived experience that exceed the purview of a phenomenalist epistemology, which relies on sense perception and denies any distinction between appearances and essences? Can one yield genuine knowledge of spiritual-intellectual realms from a passive, disinterested mode of examination, abstaining from value judgments and proceeding strictly according to inductive generalization? And, finally, is it possible to figure the subjectivity and historicity of the observer without thereby sacrificing a claim to universal validity? Such questions fueled a “crisis of science” addressed by Max Weber in his celebrated 1917 lecture, “Wissenschaft als Beruf” (Science as a Vocation), delivered at a time when many in the younger generation expressed radical skepticism about the ultimate purpose and meaning of specialized intellectual inquiry.6

The general rebellion against science at the end of the “long nineteenth century” involved the rejection of a specific tradition of historical thinking. Though not a simple positivist, Leopold von Ranke had upheld a correspondence theory of truth, pursuing the ideal of faithfully and impartially re-creating empirical reality—or, in his well-known words, showing “wie es eigentlich gewesen” (how it actually was).7 Ranke’s mode of historiography, involving the rigorous collection of individual facts, was criticized as early as 1874 by Friedrich Nietzsche, for whom it entailed a dry, ascetic antiquarianism as well as the dissolution of all foundations into a ceaseless, Heraclitean flux.8 Wilhelm Windelband, Heinrich Rickert, and Wilhelm Dilthey later addressed epistemological and methodological issues related to the science of history, seeking to provide a firm basis for historical knowledge and understanding. Their inability to wield off the relativist implications of historicism presaged a crisis of historical thought diagnosed by Ernst Troeltsch in the years following World War One, when a Rankean faith in the meaningfulness and directionality of the historical process seemed to be decisively shattered.9

Troeltsch’s final work, Der Historismus and seine Probleme (Historicism and Its Problems, 1922), prompted responses by Friedrich Meinecke, Karl Mannheim, Otto Hintze, Karl Heussi, and Siegfried Kracauer, who reviewed Troeltsch’s book alongside a collection of essays by Max Weber in 1923.10 In this text, entitled Die Wissenschaftskrisis (The Crisis of Science), Kracauer stated that empirical sciences such as history and sociology, which had significantly expanded in scope during the nineteenth century, confronted an insurmountable dilemma as they made claims to universal validity, the consequences of which, in his words, were “senseless accumulation of material [Stoffanhäufung] and unavoidable relativism.”11 In his Photography essay of 1927, Kracauer used the same word to describe the “accumulation [Häufung]” of photographs proliferating in illustrated newspapers, and he linked photographic media to historicism.12 Noting the contemporaneous emergence of photographic technology and historicist thinking, Kracauer wrote that much as the former presents a “spatial continuum” of social reality, historicism attempts to grasp historical reality by “reconstructing the course of events in their temporal succession without any gaps.”13 Four decades later, in his posthumously published History: The Last Things Before the Last (1969), Kracauer returned to the debates over historicism and further probed the nexus of historiography and photographic media.

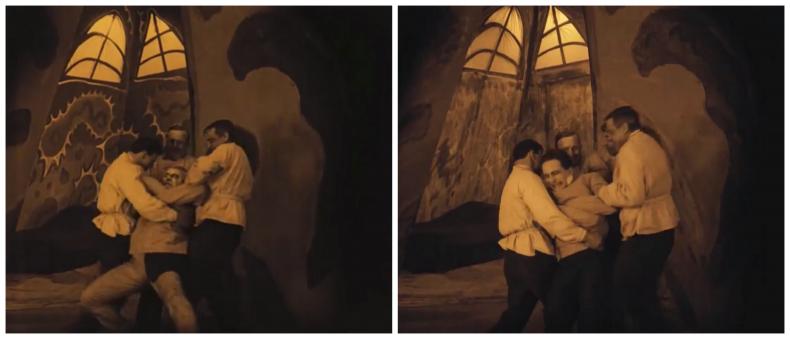

Kracauer repeatedly criticized DAS CABINET DES DR. CALIGARI in his writings, whether for the film’s alleged proto-fascism or for its misguided, even retrogressive quest to attain the legitimacy of the traditional arts.14 If, however, with a nod to his History book, one pursues an analogy between CALIGARI’s reworking of “camera reality” and contemporaneous intellectual efforts to rethink the nature and epistemology of “historical reality,”15 one might also interpret the film in terms of historical-philosophical debates—and, more specifically, as a critique of nineteenth-century German historicism. Indeed, the Expressionist 'mise en scène' of Wiene’s film not only rejects traditional realist aesthetics, but also abandons the historicist quest for unbiased and comprehensive representation. On the level of narrative, CALIGARI’s circular structure also thwarts the historicist postulation of a continuous and unilinear temporal flow; the film’s recursive form is congruent less with any sequential or developmental model than with Oswald Spengler’s vision of historical periodicity.16 Such a correspondence between Expressionist aesthetics and anti-historicism was suggested by director Robert Wiene himself in a 1922 text. Writing in the Berliner Börsen-Courier, Wiene positioned the Expressionism that emerged in the decade before World War I as a reaction against aesthetic realism, whether in its historicist or naturalist guises. For Wiene, Expressionism marked an “an irrepressible countermovement, which turned against the last vestiges of historicism—in short, against all forms of realism,”17 and had since become the goal of film and all other arts in the current era. In the following sections, I will seek to reinterpret Wiene’s film in relation to the crisis of historicism.

Kracauer and DAS CABINET DES DR. CALIGARI

Among the major points of contention in scholarship on Wiene’s film since Kracauer’s From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film (1947) is the function of the frame narrative, the addition of which, in Kracauer’s well-known assessment, transformed “a revolutionary film […] into a conformist one.”18 Kracauer based his appraisal of the film on a 1941 manuscript by Hans Janowitz, who had attributed the narrative device to Wiene, disavowing its presence in the original script.19 Numerous scholars have since diverged from Kracauer’s critique, offering alternative readings of CALIGARI’s politics; most recently, Anton Kaes has characterized CALIGARI as “an aggressive diatribe against the murderous practices of war psychiatry,” associating the film with “Dada’s nihilistic attacks on the establishment.”20 While I would agree with those who have emphasized that CALIGARI’s openness and indeterminacy frustrate all ascriptions of direct socio-historical referentiality and political coherence,21 I also wish to shift focus to an unexplored area of inquiry: namely, the film’s engagement with issues of historical ontology and epistemology. In my analysis, CALIGARI marks a challenge to basic historicist tenets, including the objectivity of historical accounts, the reliability and authority of narration, and the alignment of power and ethics. The film, I will argue, conveys a radical skepticism regarding the possibility of detached, disinterested observation, suggesting a Nietzschean sense of historical reality as the interplay of finite interpretations.22

For Kracauer, CALIGARI’s framing device pathologizes the narrator, Francis, thereby delegitimizing and even reversing his story’s implied challenge to state authority. Furthermore, Kracauer views the narrative device itself, with its ambivalent gesture of containment, as the symbol of a collective trend in Weimar Germany toward both solipsistic retreat and inner, “psychological revolution.”23 Apart from its factual errors, internal contradictions, and dubious methodological premises, Kracauer’s argument confronts myriad hermeneutical obstacles, most obviously the extension of the film’s Expressionist design into the framing scenes and their intertitles. Because the film’s concluding episode does not, as Kracauer himself notes, restore “conventional reality,” it problematizes the relationship between Expressionist stylization and narrational insanity assumed by many contemporary reviewers.24 Whereas Kracauer nonetheless maintains that Francis’ story is bracketed as a “madman’s fantasy,”25 I would emphasize that the film not only ultimately refuses to designate his (and the asylum director’s) degree of sanity, but also interrogates the bases upon which the figures’ credibility might be evaluated and ascertained. Moreover, in contrast to Kracauer, who associates the film’s exclusive use of studio settings with a postwar German withdrawal from the exterior world, I submit that CALIGARI calls into question the very existence and accessibility of a normative reality—one external to the subjective perspectives of discrete individuals.

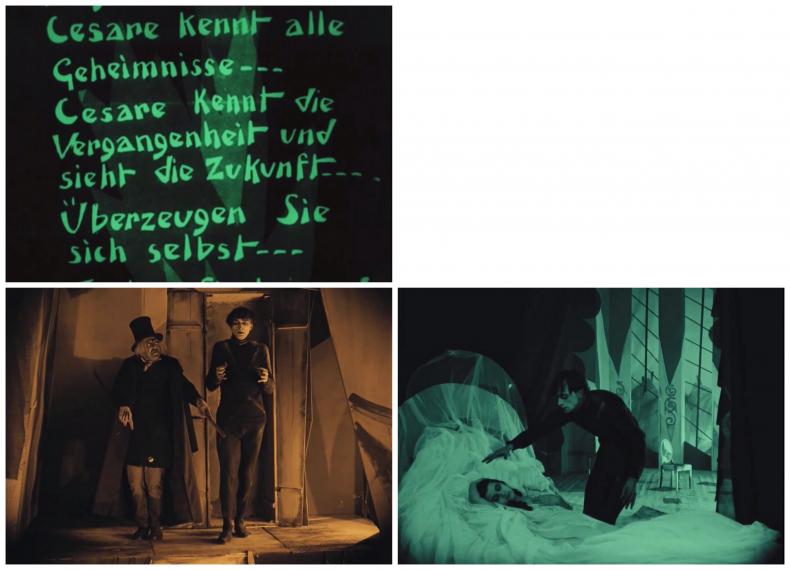

In juxtaposing CALIGARI’s framing scenes with its inner story, Kracauer also discounts the blurring of formal and textual boundaries that characterizes Wiene’s film and the Expressionist movement more generally. Distinguishing Expressionist dramaturgy from earlier theatrical practice, Walter Sokel argued that “the physical stage […] ceases to be a fixed frame of a scene or act,” and the protagonist’s dreamlike vision is no longer placed within an “explanatory frame of reference.”26 Although, as stated, CALIGARI’s Expressionist style is not consistently or unequivocally aligned with one character’s psychological state, the film nonetheless disregards the barriers between inner self and external environment, and between enigmatic visions and elucidatory frameworks. In Wiene’s film, aspects of characters’ appearances, costumes, and props (e.g., the three lines in the director’s hair and gloves; Cesare’s slender, angular physique and knife) correspond to patterns in the surrounding décor, and characteristics of the mise en scène (e.g., irregular shapes, distorted angles) extend not only to the film’s framing scenes, but also beyond the diegesis to include the font and design of the intertitles.

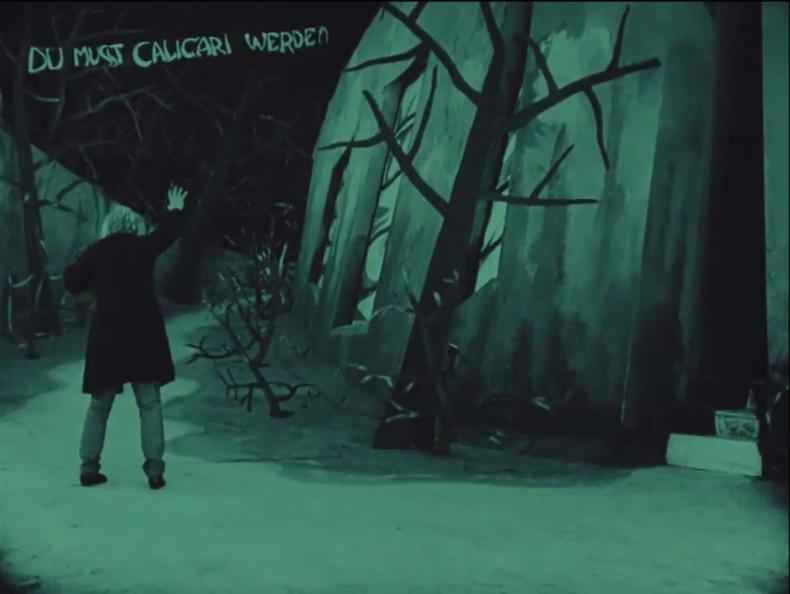

The film also obscures the thresholds between word and image, and between textual and paratextual elements; the injunction “Du musst Caligari werden” (You must become Caligari), which appears before the asylum director in a famous scene, also featured prominently in the film’s 1920 advertising campaign.27

The film’s obfuscation of conventional boundaries also applies to its narrative and thematic registers. Drawing from the Romantic and Gothic literary works of Mary Shelley (Frankenstein, 1818), E. T. A. Hoffmann (Der Sandmann, 1817), Edgar Allan Poe (The System of Doctor Tarr and Professor Fether, 1845), and Robert Louis Stevenson (The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, 1886), CALIGARI features fantastic, uncanny figures or motifs (e.g., ghosts, somnambulists, doppelgängers) that frustrate basic ontological distinctions, such as those between life and death, sleeping and wakefulness, and self and other. Cesare is first hailed for his omniscient and prophetic powers, which extend across temporal horizons (“Cesare knows the past and sees the future…”), and he is also revealed to transgress spatial boundaries, repeatedly exiting the fairground area and penetrating into others’ private spheres.

The central mystery of the story within the story—who is truly responsible for the series of murders in Holstenwall—not only bleeds into and even beyond the frame narrative, resisting unambiguous resolution or closure, but is also complicated by a further question opened up by the concluding episode: namely, whether the murders narrated by Francis in fact occurred, or if the entire inner story was merely his subjective delusion. The film’s inverse, mutually incompatible endings, alternately depicting the director and Francis in straitjackets in the insane asylum, pose an irresolvable challenge to viewers’ capacity for decisive interpretation.

In this regard, Wiene’s film foregrounds problems of hermeneutics associated with the early twentieth-century crisis of historicism, implicating its viewers as finite, locally conditioned participants within the dynamic process of history.

Problems of Hermeneutics

Recognizing the threat of relativism faced by the historical sciences, Wilhelm Dilthey adapted the interpretive procedures developed by Friedrich Schleiermacher into a methodology for securing knowledge of the past. In Die Entstehung der Hermeneutik (The Rise of Hermeneutics, 1900), Dilthey conceived a process of understanding (Verstehen) through an imaginative re-experiencing (Nacherleben) of others’ psychic states; in this way, Dilthey wrote, the subjective operations of the observer could “be raised to objective validity.”28 Among the many problems with Dilthey’s approach was an assumed homogeneity of exegete and author, or subject and object of research. Appealing to “the substratum of a general human nature” as the basis for interpretation,29 Dilthey neglected historicism’s crucial emphasis on the uniqueness of all sociocultural phenomena and values. Thus, although Dilthey sought to resist what he deemed “the inroads of […] skeptical subjectivity,”30 he failed to offer a satisfactory solution to the aporias of historicist thought, as later formulated by Hans-Georg Gadamer: “how objectivity is possible in relativity and how we are to conceive the relation of the finite to the absolute.”31 Taking up Dilthey’s hermeneutic theory, Gadamer emphasized the limited range of vision within the present as well as the unfeasibility of self-transposition into the past. While postulating the inescapability of tradition and prejudice, Gadamer invoked the potential for historical understanding through an ongoing “fusion of horizons.”32

For Dilthey, hermeneutics promised not only to avert historicism’s relativist implications, but also to delineate humanistic inquiry from an imperialist positivism. An innovator of Lebensphilosophie (philosophy of life) in the late nineteenth century, Dilthey distinguished the dynamic sphere of human activity from the inanimate objects of natural-scientific research, positing life itself as the foundation of the Geisteswissenschaften. Countering the theory of phenomenalism, which denied the distinction between appearances and essences, Dilthey described the object of the human sciences as “an inner reality, a coherence experienced from within,” and he identified the goal of hermeneutics as that of surpassing an author’s own self-understanding, as per the “doctrine of unconscious creation.”33 Furthermore, emphasizing the interpreter’s immersion in his or her very sphere of investigation, Dilthey problematized the separation of facts from judgments and also eliminated the distance between the observer and objective world; whereas the scientific method had facilitated the amassing of facts based on neutral, disinterested apprehension, Dilthey sought meaningful truth through a more holistic, projective act of interpretation. Finally, in contrast to positivism, which lacked reflexivity regarding the observer’s subjective consciousness, Dilthey characterized understanding and interpretation as “active in life itself,” and he envisaged the process of historical reconstruction (Nachbildung) as a means of self-knowledge.34

CALIGARI followed Dilthey and other ‘philosophers of life’ in critiquing positivism, challenging the privileged relation that it had presumed between vision and knowledge. Wiene’s film perpetually reveals the epistemic insufficiency of external signs, featuring figures who deceive sensory perception, assume alternate names or identities, are driven by obsessive ideas, or are even unaware of their own actions. While highlighting modes of observation and surveillance involved in detective work, the film emphasizes the fallibility and manipulability of visual evidence as well as its inadequacy for determining motives—as when a man is wrongfully accused of the murders in Holstenwall due to his possession of a knife (with which he had hoped to divert suspicion for an attempted homicide), or when Francis unwittingly watches Cesare’s dummy for hours while the actual somnambulist abducts Jane.

The film also confounds basic temporal and ontological boundaries between the researcher and the object of investigation; in a flashback within the inner story, the asylum director reads an eighteenth-century chronicle of Dr. Caligari and is compelled not only to reenact the doctor’s murderous experiments, but also to “become Caligari”.

Though Francis and the asylum’s doctors later unmask the director after scrutinizing his book and diary, the film’s concluding scenes disclose the dubiousness of Francis’ own story, thus undermining spectators’ assumptions based on the entire preceding action.

Insofar as CALIGARI unsettles attempts to ascertain knowledge on the basis of (auto-)biographical accounts, it also destabilizes central tenets of Dilthey’s hermeneutic theory. Much as the narrative’s unsolvable mysteries thwart an optimism regarding the ultimate attainability of truth, the film’s own vicissitudinous history of distribution and exhibition disrupts a philological concentration on “fixed and relatively permanent expressions of life,”35 revealing contingencies and discontinuities in the passage from a work’s creator(s) to its present-day exegete. The near-century since CALIGARI’s premiere has witnessed the circulation of prints varying significantly in length, music, intertitles, and coloration, as well as the proliferation of spurious, often-contradictory claims regarding the film’s authorship, production process, and political meanings. Important discoveries (e.g., the screenplay, a tinted nitrate copy) over the past decades have dispelled numerous legends about the film and have also facilitated more precise, historically grounded readings.

In my analysis, however, the unreflexive empiricism of much new film-historical research is at odds with the film’s own pointed critique of nineteenth-century historical methodology. If, as I have sought to demonstrate, CALIGARI rejects a naïve objectivism and abandons the historicist quest for comprehensive representation, the film renders one recent encyclopedic effort to document “the true story behind its creation” a rather ironic undertaking.36

CALIGARI and New Film History

The author of the aforementioned tome, which was published to much acclaim in Germany in 2012, argues that few films were as susceptible to the inadequacies of prior scholarship as CALIGARI. In the author’s estimation, the traditional historiography “was teeming with legends and false, superficial, and inaccurate representations.”37 The main objectives of the author’s study are to dispel the numerous legends surrounding the film and “to place Caligari research on a broader empirical basis.”38 The author aligns his book’s approach with that of New Film History in its consideration of newly available films and extratextual sources, as well as in its attentiveness to the “complex structure of factors” that shapes any work.39

In this endeavor, the author tacitly follows the critical-historical methodology of Ranke and the Historical School. With his avowed dedication to “precise source criticism” and his determination to ascertain “objective facts” such as “when the film was actually shot,”40 the author recalls Ranke’s ideal of faithfully and impartially reconstructing the past, or showing “how it actually was.” Furthermore, in his attempt to offer a comprehensive, all-inclusive account of CALIGARI’s genesis and context of development, the author renews the historicist quest for complete and unbroken coverage, seeking to grasp historical reality, in Kracauer’s words, by “reconstructing the course of events in their temporal succession without any gaps.”41

CALIGARI, as I have argued, emerged at a time when the German historicist tradition was entering a state of acute and widely diagnosed crisis, and the film dismissed the ideals of Ranke in favor of Nietzsche’s perspectivist vision of historical reality as the interplay of finite interpretations. Moreover, the film’s oft-noted self-reflexivity aligns it with what Hayden White has called an “ironic” mode of historiography, or one aware of the relativity of all values and conscious of the problematics of narration.42 One might have wished for such ironic self-reflexivity on the part of the author of the recent CALIGARI book, who—claiming “to have solved the secrets of the film in essence”43 —seeks to provide the definitive account of a film that itself highlights the invariable subjectivity and epistemological limitations of all historical reports.

I use this example not to single out a particular film historian for criticism, but rather to suggest broader limitations of the film-historical approach with which the author aligns himself. In my view, while New Film History has emphasized the 'historicity' of moving images, it has all too often left the very 'concept of history' under-examined and insufficiently historicized. Though long eclipsed by From Caligari to Hitler, Kracauer’s posthumous book on History points to a more reflexive model of historiography, acknowledging antinomies and discontinuities in conceptions of time and history. Not least, Kracauer’s final book remains vital today in suggesting an underexplored approach to film and other media—one that considers them in conjunction with central ontological and epistemological questions of the philosophy of history.

- 1On this point, see, e.g., Tom Gunning, “‘Now You See It, Now You Don’t’: The Temporality of the Cinema of Attractions,” in Silent Film, ed. Richard Abel (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1996), 71–84; and Linda Williams, ed., Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995).

- 2See Thomas Elsaesser, “The New Film History,” Sight and Sound 55, no. 4 (Autumn 1986): 246–251; H. Aram Veeser, ed., The New Historicism (London: Routledge, 1989); and James Harvey Robinson, The New History: Essays Illustrating the Modern Historical Outlook (New York: Macmillan, 1912).

- 3See, e.g., Walter Laqueur and George Mosse, eds., The New History: Trends in Historical Research and Writing Since World War II (New York: Harper and Row, 1967); and Jacques Le Goff, Roger Chartier, and Jacques Revel, eds., La Nouvelle Histoire (Paris: Retz, 1978). Fernand Braudel had also invoked “une histoire nouvelle” in his 1950 inaugural lecture at the Collège de France.

- 4Robert C. Allen and Douglas Gomery, Film History: Theory and Practice (New York: Knopf, 1985), 16–17.

- 5On positivist thought, see H. Stuart Hughes, Consciousness and Society (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 2002), 33–66; and Leszek Kolakowski, The Alienation of Reason: A History of Positivist Thought, trans. Norbert Guterman (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1968), 1–10.

- 6Max Weber, “Wissenschaft als Beruf,” in Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre, ed. Johannes Winckelmann (Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1968): 582–613.

- 7Leopold Ranke, “Vorrede,” in Geschichten der romanischen und germanischen Völker von 1494 bis 1535 (Leipzig and Berlin: G. Reimer, 1824), vi.

- 8Friedrich Nietzsche, “Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben,” Unzeitgemäße Betrachtungen, Werke in drei Bänden, vol. I, ed. Karl Schlechta (Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1994), 209–285.

- 9Ernst Troeltsch, “Die Krisis des Historismus,” Die neue Rundschau 33 (1922): 572–590. See also Charles R. Bambach, Heidegger, Dilthey, and the Crisis of Historicism (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995); Hughes, Consciousness and Society, 183–248; and Georg G. Iggers, “The Dissolution of German Historicism,” in Ideas in History: Essays Presented to Louis Gottschalk by His Former Students, ed. Richard Herr and Harold T. Parker (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1965), 288–329.

- 10Ernst Troeltsch, Der Historismus und seine Probleme (Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1922); Friedrich Meinecke, “Ernst Troeltsch und das Problem des Historismus,” in Zur Theorie und Philosophie der Geschichte, ed. Eberhard Kessel (Stuttgart: K.F. Koehler Verlag, 1959), 367–378; Karl Mannheim, “Historismus,” Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik 52, no. 1 (1924): 1–60; Otto Hintze, “Troeltsch und die Probleme des Historismus. Kritische Studien,” Historische Zeitschrift 135, no. 2 (1927): 188–239; and Karl Heussi, Die Krisis des Historismus (Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1932).

- 11Siegfried Kracauer, “Die Wissenschaftskrisis. Zu den grundsätzlichen Schriften Max Webers und Ernst Troeltschs,” in Werke, vol. 5.1, ed. Inka Mülder-Bach (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2011), 591; emphasis in original.

- 12Siegfried Kracauer, “Photography,” in The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, ed. and trans. Thomas Y. Levin (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995), 59.

- 13Ibid., 49.

- 14See Siegfried Kracauer, “Wiedersehen mit alten Filmen. Der expressionistische Film,” Kleine Schriften zum Film, vol. 6.3, ed. Inka Mülder-Bach (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2004), 266–270; Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, ed. Leonardo Quaresima (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004), 61–76; and Kracauer, Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997), 37, 39, 61, 84–85.

- 15Siegfried Kracauer, History: The Last Things Before the Last (Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener, 1995), 3–4.

- 16Oswald Spengler, Decline of the West, trans. Charles Francis Atkinson (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1926).

- 17Robert Wiene, “Expressionism in Film,” trans. Eric Ames, in The Promise of Cinema: German Film Theory, 1907–1933, ed. Anton Kaes, Nicholas Baer, and Michael Cowan (Oakland: University of California Press, 2016), 437.

- 18Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler, 67.

- 19Hans Janowitz, “Caligari – The Story of a Famous Story,” in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: Texts, Contexts, Histories, ed. Mike Budd (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990), 221–239.

- 20Anton Kaes, Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Culture and the Wounds of War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009), 53.

- 21See, e.g., Stefan Andriopoulos, “Suggestion, Hypnosis, and Crime: Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920),” in Weimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the Era, ed. Noah Isenberg (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009), 24; and Thomas Elsaesser, Weimar Cinema and After: Germany’s Historical Imaginary (London: Routledge, 2000), 63, 76, 79, 92, 95.

- 22For a more extended account of Caligari and Nietzschean perspectivism, see Nicholas Baer, “Post-Perspectival Aesthetics in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” in The New Berlin, 1912–1932, ed. Inga Rossi-Schrimpf (Brussels: Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, 2018), 93–99.

- 23Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler, 67.

- 24Ibid., 70.

- 25Ibid., 67.

- 26Walter H. Sokel, The Writer in Extremis: Expressionism in Twentieth-Century German Literature (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1959), 38, 45.

- 27On paratextuality, see Gérard Genette, Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation, trans. Jane E. Lewin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

- 28Wilhelm Dilthey, “The Rise of Hermeneutics,” trans. Fredric Jameson, in New Literary History 3, no. 2 (Winter 1972): 231.

- 29Ibid., 243.

- 30Ibid., 244.

- 31Hans-Georg Gadamer, Truth and Method, trans. Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall (New York: Continuum, 2004), 230.

- 32Ibid., 305.

- 33Dilthey, “Hermeneutics,” 231, 244.

- 34Ibid., 241, 231. On Dilthey, see also Gadamer, Truth and Method, 214–235; Martin Jay, Songs of Experience: Modern American and European Variations on a Universal Theme (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 216–260; and Reinhart Koselleck, “Standortbindung und Zeitlichkeit. Ein Beitrag zur historiographischen Erschließung der geschichtlichen Welt,” in Vergangene Zukunft. Zur Semantik geschichtlicher Zeiten (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1979), 176–207.

- 35Dilthey, “Hermeneutics,” 232. Dilthey claimed that only written documents could be the objects of generally valid interpretation.

- 36Olaf Brill, Der Caligari-Komplex (Munich: Belleville, 2012), 7; see also Olaf Brill, “Traditionelle Filmgeschichtsschreibung versus New Film History,” Dokumentation des 9. FFKs, ed. Britta Neitzel (Weimar: Universitätsverlag, 1997), 9–23.

- 37Brill, Der Caligari-Komplex, 115.

- 38Ibid., 117.

- 39Ibid., 18.

- 40Ibid., 117, 299, 10.

- 41Kracauer, “Photography,” 49.

- 42Hayden White, Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973), 37–38.

- 43Brill, Der Caligari-Komplex, 10.

Allen, Robert Clyde, and Douglas Gomery. Film History: Theory and Practice. New York: Knopf, 1985.

Andriopoulos, Stefan. “Suggestion, Hypnosis, and Crime: Robert Wiene’s The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920),” in Weimar Cinema: An Essential Guide to Classic Films of the Era, ed. Noah Isenberg. New York: Columbia University Press, 2009.

Baer, Nicholas. “Post-Perspectival Aesthetics in The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari,” in The New Berlin, 1912–1932, ed. Inga Rossi-Schrimpf. Brussels: Royal Museum of Fine Arts of Belgium, 2018.

Bambach., Charles R. Heidegger, Dilthey, and the Crisis of Historicism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1995.

Brill, Olaf. Der Caligari-Komplex. Munich: Belleville, 2012.

Brill, Olaf. “Traditionelle Filmgeschichtsschreibung versus New Film History,” in Dokumentation des 9. FFKs, ed. Britta Neitzel. Weimar: Universitätsverlag, 1997.

Dilthey, Wilhelm. “The Rise of Hermeneutics.” Translated by Fredric Jameson. New Literary History 3, no. 2. (Winter 1972).

Elsaesser, Thomas. “The New Film History.” Sight and Sound 55, no. 4 (Autumn 1986).

Elsaesser, Thomas. Weimar Cinema and After: Germany’s Historical Imaginary. London: Routledge, 2000.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg. Truth and Method. Translated by Joel Weinsheimer and Donald G. Marshall. New York: Continuum, 2004.

Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Translated by Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997.

Gunning, Tom. “‘Now You See It, Now You Don’t’: The Temporality of the Cinema of Attractions.” In Silent Film, edited by Richard Abel. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1996.

Heussi, Karl. Die Krisis des Historismus. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1932.

Hintze, Otto. “Troeltsch und die Probleme des Historismus. Kritische Studien.” Historische Zeitschrift 135, no. 2 (1927).

Hughes, Henry Stuart. Consciousness and Society. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction, 2002.

Iggers, Georg Gerson. “The Dissolution of German Historicism.” In Ideas in History: Essays Presented to Louis Gottschalk by His Former Students, edited by Richard Herr and Harold T. Parker. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1965.

Janowitz, Hans. “Caligari – The Story of a Famous Story.” In The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari: Texts, Contexts, Histories, edited by Mike Budd. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 1990.

Jay, Martin. Songs of Experience: Modern American and European Variations on a Universal Theme. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Kaes, Anton. Shell Shock Cinema: Weimar Culture and the Wounds of War. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Kolakowski, Leszek. The Alienation of Reason: A History of Positivist Thought. Translated by Norbert Guterman. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1968.

Koselleck, Reinhart. “Standortbindung und Zeitlichkeit. Ein Beitrag zur historiographischen Erschließung der geschichtlichen Welt.” In Vergangene Zukunft. Zur Semantik geschichtlicher Zeiten. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1979.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “Die Wissenschaftskrisis. Zu den grundsätzlichen Schriften Max Webers und Ernst Troeltschs,” Werke vol. 5.1, edited by Inka Mülder-Bach. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2011.

Kracauer, Siegfried. From Caligari to Hitler: A Psychological History of the German Film, edited by Leonardo Quaresima. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2004.

Kracauer, Siegfried. History: The Last Things Before the Last. Princeton, NJ: Markus Wiener, 1995.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “Photography.” In The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, edited and translated by Thomas Y. Levin. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Kracauer, Siegfried. Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “Wiedersehen mit alten Filmen. Der expressionistische Film.” In Kleine Schriften zum Film vol 6.3, edited by Inka Mülder-Bach. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 2004.

Laqueur, Walter, and George Mosse, eds. The New History: Trends in Historical Research and Writing Since World War II. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

Le Goff, Jacques, Roger Chartier, and Jacques Revel, eds. La Nouvelle Histoire. Paris: Retz, 1978.

Meinecke, Friedrich. “Ernst Troeltsch und das Problem des Historismus.” In Zur Theorie und Philosophie der Geschichte, edited by Eberhard Kessel. Stuttgart: K.F. Koehler Verlag, 1959.

Mannheim, Karl. “Historismus.” In Archiv für Sozialwissenschaft und Sozialpolitik 52, no. 1 (1924).

Nietzsche, Friedrich. “Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben.” In Unzeitgemäße Betrachtungen, Werke in drei Bänden vol. I, edited by Karl Schlechta. Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1994.

Robinson, James Harvey. The New History: Essays Illustrating the Modern Historical Outlook. New York: Macmillan, 1912.

Ranke, Leopold. “Vorrede.” In Geschichten der romanischen und germanischen Völker von 1494 bis 1535. Leipzig and Berlin: G. Reimer, 1824.

Sokel, Walter H. The Writer in Extremis: Expressionism in Twentieth-Century German Literature. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1959.

Spengler, Oswald. Decline of the West. Translated by Charles Francis Atkinson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1926.

Troeltsch, Ernst. “Die Krisis des Historismus.” Die neue Rundschau 33 (1922).

Troeltsch, Ernst. Der Historismus und seine Probleme. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1922.

Veeser, Harold Aram, ed. The New Historicism. London: Routledge, 1989.

Weber, Max. “Wissenschaft als Beruf.” In Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Wissenschaftslehre, edited by Johannes Winckelmann. Tübingen: J.C.B. Mohr, 1968.

White, Hayden. Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

Wiene, Robert “Expressionism in Film,” translated by Eric Ames. In The Promise of Cinema: German Film Theory, 1907–1933, edited by Anton Kaes, Nicholas Baer, and Michael Cowan. Oakland: University of California Press, 2016.

Williams, Linda, ed. Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1995.