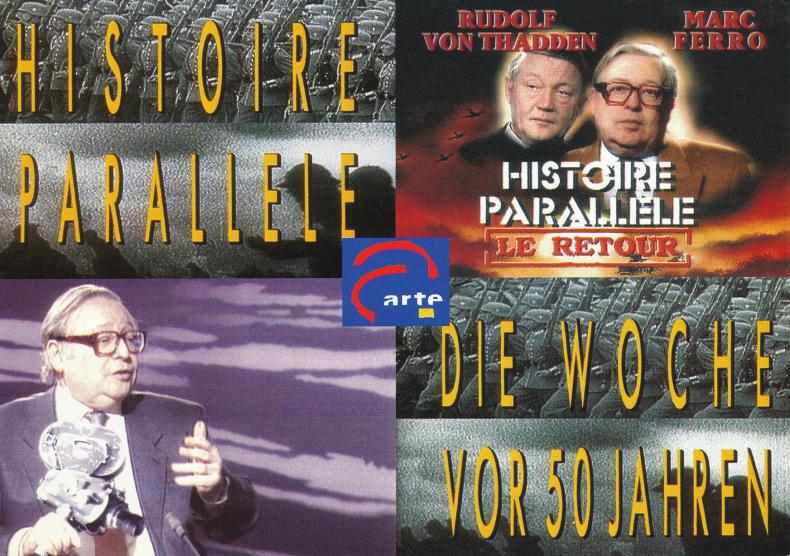

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Experience and Analysis of Historical Images on Television

Table of Contents

Returning to the Past its Own Future

Recent Appropriations of Documentary Film Material from the Shoa Era

Archiveology

A State Commemorates Itself

Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989-2001)

The Relationship between Film and History in Early German Postwar Cinema

Sound Space as a Space of Community

Image Migration and History

Recording and Modeling

The Mediated Eyewitness

Experiencing History in Film

Kracauer's Theory of History and Film

Historical Turns

Re-Membering the Past

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Steinle, Matthias: Marc Ferro's DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN / HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (1989–2001): The Experience and Analysis of Historical Images on Television. In: Research in Film and History. The Long Path to Audio-visual History (2018), No. 1, pp. 1–11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14790.

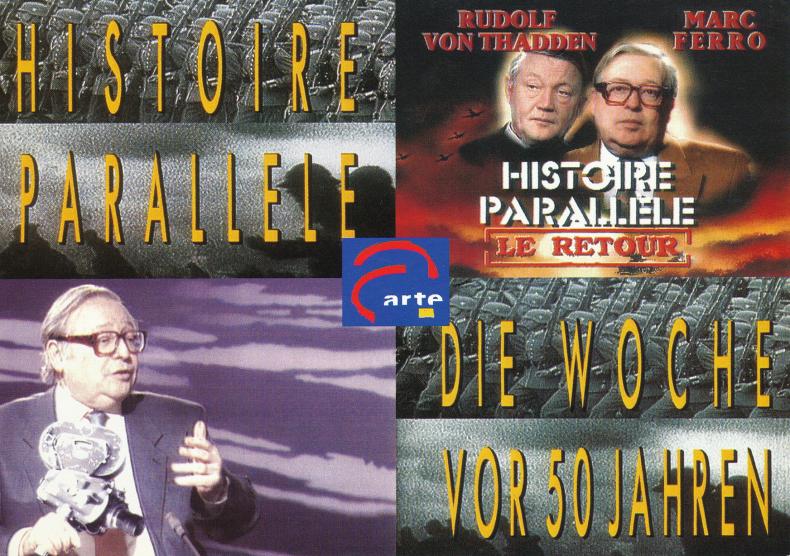

For twelve years, a weekly broadcast with a loyal audience in France and Germany: the television series HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN (1989-2001) moderated and co-created by the historian Marc Ferro was an unexpected success and the longest series on the cultural channel Arte. The history of HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE is still waiting to be written, due not least to its virtual biblical format with 630 episodes.1 The following discussion can only draw attention to this gap, which is an unfortunate one, not only when it comes to research in terms of current television historical formats. The focus will be placed on the potential of the series in the production and experience of history. A main hypothesis is that the relative simplicity of the devices used enabled an adequate and reflected use of film as a source and an agent of history, opening a realm of experience to a wide audience.

Marc Ferro developed “film and history” as a historiographical approach in the 1970s.2 While his innovative ideas have found a worldwide echo, his films remain absent from the research of (film) history.3 Ferro’s work as an author for film productions – he insisted he was not to be a director – included all kinds of film and television formats and different approaches, not only classical historical compilation films on 35mm characterizing the beginning of his “cinematographic career” in the 1960s. There were for example two series of short Super 8mm films without sound about the First World War and the Spanish Civil War to be used at school (HISTOIRE CONTEMPORAINE; 1969-1972, D: Pierre Gauge), a film about the war in Algeria, banned by the censors (ALGÉRIE 1954, LA RÉVOLTE D’UN COLONISÉ; 1974; D: Marie Louise Derrien), a series on the history of medicine with fictional elements (UNE HISTOIRE DE LA MÉDECINE; 1980; conceived with Jean-Paul Aron, D: Pierre Gauge, Claude de Givray and Jean-Louis Fournier) and 60 one-minute films for Italian television (L'HISTOIRE EN 1 MINUTE, 1988, D: Pierre Gauge). Surprisingly, Ferro’s own films, except for HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE, were never the subject of his theoretical engagement with film and television.

The reasons for this may be enlightened by Ferro’s first practical experience with film as a medium which was more or less coincidental: his doctoral advisor Pierre Renouvin was to supervise a film project on the First World War as a historical consultant in 1964. Since he had neither the inclination nor the time to do so, he sent his doctoral student to do the job. When the intended director Frédéric Rossif4 quit, his assistant Solange Peter became the official director and Ferro took on the position of author and participated in directing the compilation film, involving himself in all phases of production.5 LA GRANDE GUERRE / DER ERSTE WELTKRIEG was a French-German coproduction that was broadcast on both sides of the Rhine on the same day, and was a great success with the audience. The film was also praised by politicians and those responsible for television in Germany and France.6 Historians, however, took little if any notice of the film, just as they tended to ignore moving images in general, and although Ferro in retrospect called the project “one of his greatest adventures,” his description from the point of view of a historian was rather ambiguous. In a brief 1965 article, he concluded:

“The limitations placed on the image or the commentary made this kind of document easily vulnerable. In addition, film can’t try to be an illustrated history seminar, it has its own personality. The style here is more important than in a history book, since it is expected that a film is a performance. The spectator is supposed to be captured by the film’s dynamic and brought with the film. To obtain this result, the historian has to enter a compromise with the rules of his craft. He has to accept being schematic and modifying his own concepts in order to create an aesthetically more-valuable product. In the end, the only form that allows him to communicate with the audience.”7

The main thrust of the article is that Marc Ferro in HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE found a device that required no compromises with the standard rules of his profession, on the contrary: television offered new instruments well-suited to audio-visual material. Furthermore, in the series justice was also done to the film documents, and thanks to its serial format they succeeded in creating a special relationship to the audience, unique in television history.

The Beginnings of HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE, 1989

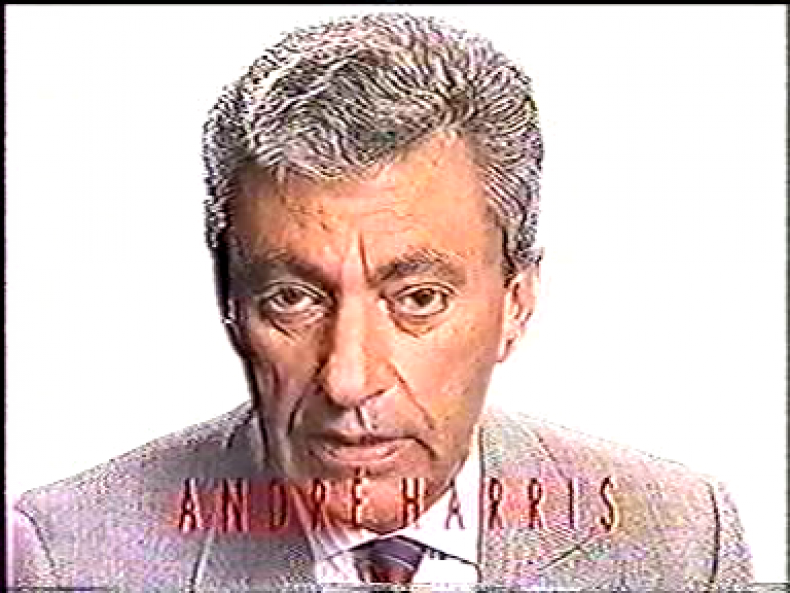

The original concept of HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE seems relatively simple: to show as a whole the newsreels produced each week 50 years ago by the two states at war with one another and having two historians from the countries in question discuss them. French producer Louisette Neil8 convinced André Harris,9 director of programming at the cultural channel La Sept,10 to show one of the German and one of the French newsreels shown in the cinemas at the time in parallel each week, starting with the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the war.11

Harris presented the new format before the first broadcast on August 27, 1989, by emphasizing three principles on which HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE was based: first of all, completeness, that is, showing the weekly newsreel in its entirety without cuts, so that the viewers, as Harris puts it, could see the newsreels “the way people saw them at the time, week after week.” Second, the principle of parallelism, that is, developing two national perspectives by confronting a German newsreel with a French one. Third, the principle of the changing gaze or the dual mirror thanks to the “analysis of two individuals from different generations” and nationalities.12

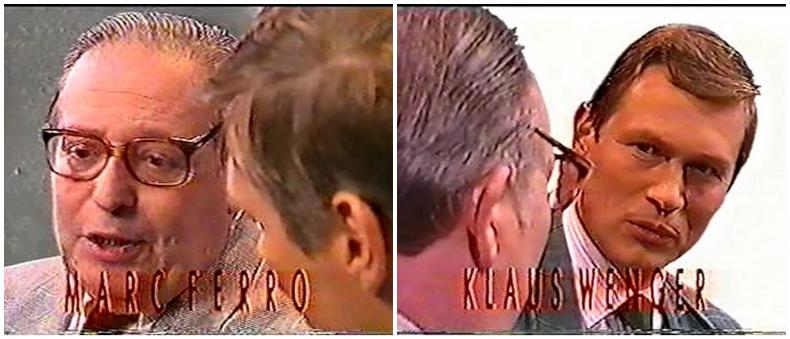

The historians who commented on the newsreels were Marc Ferro, born in 1924 and a member of the Résistence whose mother was deported as a Jew and killed in the camps, and Klaus Wenger, born in 1947, at the time creative director at SWR and later managing director of Arte Deutschland. If international dialogue was part of the concept of the show, the inter-generational aspect was more or less a “lucky accident,” because the German historians originally asked, Eberhard Jäckel and Rudolf von Thadden, were unable to participate.13

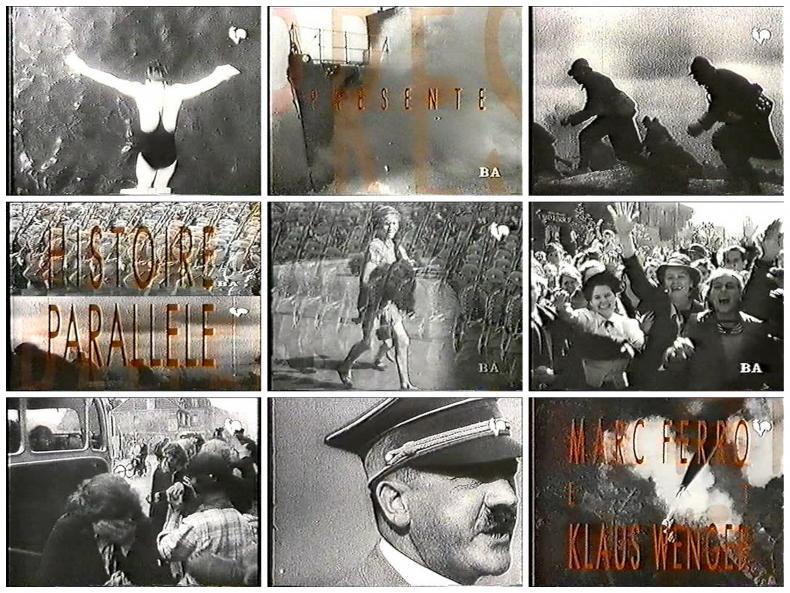

The one-minute title sequence, which would introduce all later episodes,14 begins with images in slow motion from the newsreels to follow, underlain with slightly distorted, stretched, dull sounds. When the title HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE appears, the screen divides horizontally, to show in the upper part of the split screen marching Wehrmacht soldiers and in the lower part running French soldiers. The selection of images, using a mixture of iconic (celebratory Germans, Hitler, bombs falling) and atypical images (high divers), indicates the focus of the series: the war as it was shown in the newsreels and as it was experienced from this perspective. Thus, sport and other entertaining subjects are also included, subjects rarely treated in the many documentaries on the subject.

The film-aesthetic techniques not only serve the purpose of dramatization, to awake the interest of the spectators in a way that is typical of television: they also visualize the principle of parallelism programmatically in the split screen, using dissolves in the transitions to point to the transnational linkages and by using slow motion underscoring the necessity for a precise analytic look at the images.

The first episode begins with a ten-minute extensive presentation of the project by both historians, who also take this opportunity to introduce themselves.

Furthermore, the introduction represents a reflection on the role of the historian and the eyewitness, and speaks of the emotional dimension of historical images and lived-through history, when Ferro gets teary eyed when thinking of the suffering during the war.

Ferro: “To try to write a book about Vichy and Pétain, where no one could say one is being malicious, that justified my profession in my eyes, you understand? So I tried to work on this period. To tell the truth, I regretted it somewhat, for it was pouring salt onto my wounds. I suffered a great deal in the war: and to work through all that again, to see the cruelties, to recall the way people behaved at the time, that was horrible. And I think I suffered even more as a historian than when I suffered in reality. When I was suffering in reality, I was able to defend myself, I could become a solider, and I did. But when confronted with history, one is completely powerless.”

Wenger: “Maybe it’s the same feeling of powerlessness that I felt when confronted with the images in MEIN KAMPF.“15

Ferro and Wenger not only present themselves as historians and specialists, who are going to explain the images and the histories behind them in the program to follow, but also as eyewitnesses, as people with experience and interests. Instead of doubling their authority as eyewitnesses, they relativize it vis-à-vis the helplessness of history. The tears in Ferro’s eyes, to which Wenger briefly later refers to explicitly, saying that this brought history closer to him than all the incomprehensible numbers of the murdered, also point to the role of emotions that allow for a different kind of experience and understanding of history.16 The two historians respond to the overwhelming impact of the images with an extensive verbal analysis, where they reflect on that very impact, on themselves and on the audience at the time.

In their introduction, the two historians also refer to the media dimension of history, for example when Klaus Wenger mentions the film MEIN KAMPF (1960) by Erwin Leiser, which was a shock for him and provoked a different view of German history. At the same time, this is a reference to the palimpsest character of the newsreels from fifty years ago that continued to circulate after 1945.17 The historicity of the images thus becomes clear beyond the history of their production context as the history of their reuse. Ferro and Wenger reflect on the role of images in the past for and in the present, making clear not only the historicity of the media, but also the mediacy of history itself.

Marc Ferro repeatedly called the program the “Cinderella” of the channel because of the small budget18 and because it was “aesthetically impoverished”,19 since there was nothing to see except for the talking heads of usually elderly men and the newsreels themselves.

This was contradicted to the extent that the news reels, at least the German ones—Goebbels’ most efficient propaganda weapon20 —showed quite attractive images that were still able to develop their audiovisual draw, since shown unedited.21 This meant the danger of attracting the wrong friends among the audience, and in the first weeks the producers received a great deal of mail where the series was accused of creating neo-Nazis because the images were more powerful than the analysis of the historians.22

The series was initially only to continue through June 1940, that is, as long as there were French newsreels, until the French defeat cut off the source.23 Due to the positive audience response, the series was continued, at first with British newsreels, later with Russian, American and Japanese ones, and with the spread of the war with newsreels from all over the world.24 When Arte began broadcasting in May 1992, HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE was seen on German screens as DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN.25

On the Reception of HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / (beginning in 1992) DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN

The truly “revolutionary” aspect of the program, according to Marc Ferro, was that it had a specific temporality, modeled on the principle of the daily soap, in the everyday life and life rhythm of the spectators.26 At issue was “history in the rhythm of life, week after week, history in real time.”27 One critic spoke of the invention of “perpetual television” and ironically summed up the alternative temporal perception of the fans of HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE as follows:

“Those who don’t watch Arte regularly were interested in the Schengen Agreement, while we were dealing with the general offensive of the German Wehrmacht. Under Edith Cresson, military service was cut back to 10 months, but Japan attacked Pearl Harbor. At the moment when truck drivers rebelled against the point system under Bérégovoy, Hitler ordered an attack on the Caucasus. It was only under Balladur that we were able to breathe.”28

The device used in HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN made history palpable as an open process and not as an omniscient retrospective. In this way, the series enjoyed unexpected success in France with an important core audience.29 In Germany, in contrast, the viewership, if it could be called that, was very small indeed, since the broadcast could only be seen via cable or satellite. The spectator response could be found in an impressive amount of fan mail: by 1995, the program team had received 10,000 letters, according to Ferro evidence that television spectators were becoming “active citizens.”30 From among these reactions, Marc Ferro and Denise Babin selected 200 for the publication Revivre l’histoire (Reliving History), which explored the various aspects of a history from below. The first chapter consists of contributions with complementary views of history, the second is dedicated to everyday life as experienced, and in the third debates and conflicts are brought in and those who live in the past are allowed to have their say, showing that, no matter how intelligent a film might be, people rely primarily on their own memory and only see what they want to see.31 In retrospect, Ferro summed up this experience as follows: “The people believe what they want to believe. It’s as if we were useless.”32

The Development of HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN

The series developed over time and the shows became more complex as the war spreads: along with the old format of two newsreels shown in parallel and the advantages this offered, there were now shows in which only one newsreel was shown, allowing the central event, for example, the landing of the Allies in Normandy, to be seen from the perspective of various countries, supplemented with material from feature films and other documentaries. In addition, the newsreels were fragmented, that is, no longer broadcast en bloc, but after one or several items followed by an analysis.33

The list of historians who appeared on DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN represents an international Who’s Who of the discipline in the 1990s.34 Besides Klaus Wenger and Rudolf von Thadden, several other historians and eyewitnesses as well as other intellectuals and artists were also invited to participate, for example Jean-Luc Godard together with Eric Hobsbawn in a show for May 1 (No. 561, May 6, 2000). Even if there was usually a consensus between Ferro and his guests,35 dissent on matters of detail and sometimes on basic questions was not excluded as a possibility, making clear history’s nature as a construction and the gaze of the present with its own interests on the past.

With the end of the war in 1945, that is, in 1995, the question of how to continue presented itself: the war offered narrative and dramatic threads that the post-war period, despite the Cold War, no longer provided. Due to the success of the series, the program was continued, now including thematic episodes that no longer dealt with one historical event as treated by the weekly fifty years ago, but with cultural phenomena such as the Mafia (No. 525, Aug. 21, 1999), carnival (No. 550, Feb. 19, 2000), Christmas (No. 594, Dec. 23, 2000) or even fashion (No. 421, Aug. 30, 1997).

The guest list also began to include more prominent names: as of 1945/95, famous figures such as Henry Kissinger (No. 300, May 8, 1995) or Mikhail Gorbachev (No. 439, Jan. 3, 1998), and then current holders of political office such as the German chancellor Gerhard Schröder (No. 507, Sept. 24,1999).36 The paradoxical effect of the increased importance placed on the guests was that the audience was now interested more in the contemporary figures and less in the archival documents,37 which included some strikingly odd material and had required a significant research effort. The team that now prepared the program had grown in size.38

Summary

To conclude, allow me to summarize the possibilities that HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHRE offered to make “images of history”—from the concrete audiovisual images to the mental images they influence and that influenced them—available to experience and analysis. First and foremost, the program’s point of departure always consisted of moving images that were presented as the object of interrogation.39 The series thus demonstrated the source value of audiovisual documents, that were not only studied for what they showed, but also for what they did not show, or, in the words of Alexander Kluge, “the unfilmed criticizes the filmed.”40 The question of the correctness or the propagandistic content of what was represented also led to the question of its function, whereby the documentary shots became clear as constructions driven by interests, and not just the fascist ones. In so doing, the principle of parallelism illustrated various points of view depending on the national and/or ideological perspectives taken on an event and various interpretations of the present.

By expanding the comparison with images from other film forms and formats, especially fictional films, the images were studied in their synchronic and diachronic circulation, processes of visual migration became traceable, and it became clear how their semantics depends on their use and the history of their use, usually in a rather implicit fashion.41 The basic completeness of the main source newsreel made this clear in its structure and function as the leading audiovisual documentary medium in the first half of the twentieth century, and made it possible to show subjects otherwise not seen, soccer or fashion, and to interrogate their dimension as cultural history (these subjects moved to attention especially after 1945/1995).42 Finally, the series offered historians a stage to present their research to a wider public and with their media presence represented a form of social recognition and respect for the discipline and its representatives.

In addition to achieving high ratings in France, HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN also served to do justice to the public broadcaster’s educational mission and fulfilled what had become the cliché of the “duty to remember”. For Arte, the German-French aspect was of key significance: even if the spread of the war became international, the German-French relationship was a focus, which was honored in the 500th show, which was not filmed in the Paris studio, but with Walter Wenger in Strasbourg, on the subject “what Germany for Europe?” (WELCHES DEUTSCHLAND FÜR EUROPA?, March 6, 1999).

For Thierry Garrel, for many years responsible for documentary production at Arte, the culture channel as a German-French project was truly realized in this series.43

In the pre-YouTube era, HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN offered many spectators for the first time access to films that were otherwise inaccessible, stored in archives, except for a few, usually spectacular scenes that are recycled in an endless media loop. The special link to the viewers was based on a specific temporality that made history available to experience in “real time” as an open process. The intergenerational exchange, as was especially emphasized in the first broadcast, dominated not only on screen, but in front of the screen as well. For example, I watched the show with my grandfather, and we enjoyed it for opposite reasons: he, an air-force pilot from 1937 to 1945, because he saw “acquaintances” from the Luftwaffe, and I learned what they did besides the romanticism of flying. As the viewer mail suggested, I wasn’t the only one to watch the program with the older generation of parents and/or grandparents, triggering a dialog about the past—which in my case, unfortunately, did not get very far.

That each individual episode did not always use the potential of the format to its full extent is understandable considering its 12 years, with one hour of television per week and more than 300 guests from all over the world who were not always predictable. The quality of the show is not only attributable to Marc Ferro, but to the whole team, especially producer Louisette Neil, director Didier Deleskiewicz, and many others. When the series was ended in 2001, HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN itself became an archival treasure. Unfortunately, the rights of the archival footage were only negotiated for two broadcasts, so to show them requires clearing them again (which would be easy for the first episodes using only two different newsreels and difficult for the later ones which use many different kinds of archival material). HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE / DIE WOCHE VOR 50 JAHREN is more contemporary than ever in terms of the possibilities that it used in producing and experiencing film and history, which neither German nor French television has taken up since then.

Translated by Brian Currid

- 1An extensive study is still lacking: the articles that have been published until now deal with the early years of the programme. See Marc Ferro, “A propos d’ ‘Histoire parallèle’” [1992], Cinéma et Histoire (Paris 1993), 120-134; Klaus Wenger, “‘Historie parallèle’: Eine Dokumentationsserie über den Zweiten Weltkrieg von hoher Aktualität,” Deutsch-französische Medienbilder: Journalisten und Forscher im Gespräch / Images médiatiques franco-allemandes, ed. Ursula Koch et al. (Munich 1993), 243–246; François Garçon, “La réussite d’Histoire parallèle,” CinémAction: Cinéma et histoire autour de Marc Ferro 65 (1992), 58–61; Marc Ferro, Mes histoires parallèles. Entretiens avec Isabelle Veyrat-Masson (Paris 2011), 237–246; Sheila Schvarzman, “Constructing history on television: Marc Ferro and newsreels in Histoire Parallèle”, Tempo, vol. 20, Niterói 2014, Epub Jan. 30 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/TEM-1980-542X-2014203622en; Jean Christophe Meyer, “Histoire Parallèle/Die Woche vor 50 Jahren (La SEPT/ARTE 1989-2001): Newsreels as an 'Agent and Source of History',” VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture, 4, dec. 2015, http://ojs.viewjournal.eu/index.php/view/article/view/JETHC091/218. In 2019 will be published the first detailed study of Marc Ferro’s films with several articles about HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE: Les films de Marc Ferro, ed. Martin Goutte, Sébastien Layerle, Clément Puget, Matthias Steinle, Théorème (Paris 2019).

- 2See his first published collection of articles Cinéma et histoire (Paris 1977), which became a standard work: Marc Ferro: Cinema and History, trans. Naomi Greene (Detroit 1988).

- 3The complete filmography can be found in Goutte et al., Les films de Marc Ferro.

- 4Frédéric Rossif (1922-1990) was a popular documentary filmmaker working for French television ORTF, specialized in animal and historical documentaries. Marc Ferro was strongly impressed by his film about the Spanish Civil War Mourir à Madrid (1963) which was, in his memory, the first film made with archival materials he saw. Ferro, Mes histoires parallèles, 204.

- 5In his own words, Ferro “hadn’t a clue about film or editing.” See Matthias Steinle, “ARTE vor seiner Zeit? Deutsch-französisches Geschichtsfernsehen im Zuge des Elysée-Vertrags: La Grande Guerre / 1914-1918 / Der Erste Weltkrieg – eine WDR-ORTF-Koproduktion (1964),” Rundfunk und Geschichte 31.2 (2006), 35–48.

- 6Despite these experience and additional compilation films in the 1960s, Marc Ferro only began to engage with the medium of film in a scholarly way in the 1970s. In his mind, he published his first “real” scientific article about the subject in 1973 (“Le film, une contre-analyse de la société ?,” Annales. ESC, n° 1, vol. 28, 1973), see “Entretien avec Marc Ferro et Pierre Sorlin,” L’image d’archives. Une image en devenir, ed. Julie Maeck, Matthias Steinle (Rennes 2016), 283–284.

- 7“Les limitations imposées tantôt à l’image, tantôt au commentaire rendent donc bien vulnérable cette sorte de témoignage. Ajoutons que le film ne doit pas être un cours d’histoire illustré ; il a sa personnalité. Le style importe ici plus encore que dans un ouvrage d’histoire ; car le siècle veut qu’un film soit aussi une représentation : le spectateur doit être empoigné et entraîné dans le mouvement du film. Et pour atteindre cette réussite, l’historien doit composer avec les règles de son métier ; il doit accepter d’être schématique, modifier ses propres conceptions pour parvenir à créer une œuvre esthétiquement supérieure. La seule, en fin de compte, qui le fera communiquer avec le public. » Annie Kriegel, Marc Ferro, Alain Besançon, “L’expérience de ‘la Grande Guerre’,» Annales ESC, n° 2, vol. 20, 1965, 334.

- 8Louisette Neil (1927) worked as producer for the French television institution Ina and than the TV stations La Sept and Arte. See the conversation with her and the director Didier Deleskiewicz in: Goutte et al., Les films de Marc Ferro.

- 9André Harris (1933-1997) was a journalist, filmmaker, and producer of films like THE SORROW AND THE PITY (LE CHAGRIN ET LA PITIÉ, 1971, Marcel Ophüls). He was program director at La Sept, and then program director at Arte until 1992.

- 10La Sept was conceived as a cultural channel, which began broadcasting in May 1989 via satellite (TDF 1) and in France 3. With the founding of Arte, La Sept became the French part of the German-French culture channel.

- 11The series was broadcast on Saturdays, on La Sept initially at 8 pm with 45 minute and later 52 minute episodes at 7 pm: during the last years of the show, broadcast time was cut back to 43 minutes. The director of the first episodes was Philippe Grandrieux, Didier Deleskiewicz took over this role in 1990.

- 12See Klaus Wenger, “‘Historie parallèle’,” 244.

- 13Ferro, Mes histoires parallèles, 239f.

- 14The formal compositional principle of the credits was kept over years up to the end, the newsreel images were changed to match the year.

- 15“Tandis que sur Vichy et Pétain, essayer de faire un livre où personne ne pourra dire il est de mauvaise fois, ça, pour moi c’était la raison d’être de mon métier, tu comprends. Alors j’ai essayé de travailler cette période. Pour dire la vérité je le regrette aussi un peu, car c’était à nouveau du sel sur mes plaies. J’ai beaucoup souffert pendant la guerre. Et recommencer à travailler ça, les archives, revoir toutes ces atrocités, me rappeler le comportement des gens, c’était horrible. Et j’ai presque plus souffert en étant historien que quand j’ai souffert réellement. Parce que quand j’ai souffert réellement je pouvais me défendre, je pouvais être soldat, ce que j’ai été d’ailleurs. Mais quand on est devant l’histoire, on est totalement impuissant.” – Wenger: “Peut-être un peu ce même sentiment d’impuissance que j’ai ressenti quand j’ai été devant les images de MEIN KAMPF.”

- 16The biographic dimension were not known to the viewer, because Ferro only talked about the Jewish origins of his family and his mother murdered in the camps after his retirement. See Ferro, Mes histoires parallèles, 29f.

- 17On the concept of the film palimpsest, see Sylvie Lindeperg, “Film Production as a Palimpsest”, Behind the Screen. Global Cinema, ed. Petr Szczepanik, Patrick Vonderau (New York 2013).

- 18The budget was 230,000 francs (ca. 44,000 $), 160,000 francs (ca. 31,000 $) for film rights alone. Garçon, “La réussite d’Histoire parallèle,” 60.

- 19Ferro, “A propos d’ ‘Histoire parallèle’,” 132f.

- 20See the tenth chapter with articles by Kay Hoffmann: “‘Sinfonie des Krieges’: DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU im Zweiten Weltkrieg“, Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Vol. 3 ‘Drittes Reich’ 1933-1945, ed. Peter Zimmermann, Kay Hoffmann (Stuttgart 2005), 688.

- 21See Ferro, Mes histoires parallèles, 244.

- 22Ibid., 126.

- 23According to Ferro, as of May there were no longer any newsreels, so without asking Harris, he turned to British newsreels. Marc Ferro, “De la BDIC à Histoire parallèle,” Matériaux pour l’histoire de notre temps, 2008/1 (N° 89-90), 151. See also Ferro, Mes histoires parallèles, 238, 241.

- 24Ibid., 151. See also Ferro, “A propos d’ ‘Histoire parallèle’,” 133.

- 25According to Ferro, the actual success began in 1942, because firstly, the German newsreels were now better, secondly, the range of witnesses grew, and thirdly, for the first time history could be experienced in “real time.” See Ferro, “De la BDIC à Histoire parallèle,” 151f.

- 26“C’était le temps réel qui était, au fond, la nouveauté de cette émission, pas l’intervention de Marc Ferro.” Ibid., 152.

- 27“L’Histoire au rythme de la vie, semaine après semaine, l’Histoire en temps réels.“ Marc Ferro (with Claire Babin), Revivre l’histoire autour d’Histoire parallèle (Paris 1995), 133f.

- 28“Le non-artésien s’intéressait aux accords de Schengen, nous avions sur les bras une offensive générale de la Wehrmacht. Sous Edith Cresson, le service national passait à dix mois, mais les Japonais attaquaient Pearl Harbor. Au moment même où les routiers se dressaient contre le permis à points sous Bérégovoy, Hitler se lançait à l’assaut du Caucase. On a commencé à respirer un peu sous Balladur.“ Alain Schifres, “La fin de l’histoire,” L’Express (Sept. 6, 2001), 224.

- 29According to François Garçon, an average of 1.2 million viewers, corresponding to a 7% market share (Mediamat). Garçon, “La réussite d’Histoire parallèle,” 60. Marc Ferro speaks about a viewing ration of up to 12% in 1992. Ferro, Mes histoires parallèles, 242. Jean Christophe Meyer queried these high ratings on the basis of the only indication he could obtain from ARTE France concerning the special show featuring Henry Kissinger broadcast on May 8th 1995: “Despite special design and prestigious guests, it only reached a 2.3% share, which represented around 450,000 viewers. For the same show, ARTE Deutschland indicated a 0.1% share and a total of 30,000 viewers with an average age of 45 years old. Only 10 shows out of 335 broadcast between January 6th 1995 and September 1st 2001 reached an audience of 100,000 viewers or more in Germany.” See the ratings from 1995 up to 2001 in Meyer, “Histoire Parallèle,” 6.

- 30Ferro/Babin, “L’Histoire au rythme de la vie,” 10.

- 31Ibid., 13; Ferro, Mes histoires parallèles, 245f.

- 32Ferro, “De la BDIC à Histoire parallèle,” 152.

- 33Critical comments on the “segmentation” in Michèle Lagny, “Historischer Film und Geschichtsdarstellung im Fernsehen” [2001], Hohenberger/Keilbach, Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit, 125f.

- 34See Ferro, Mes histoires parallèles, 241f.

- 35Marc Ferro speaks of a “game of words” between the guest and himself, adding and complementing information (Marc Ferro, “A propos d’ ‘Histoire parallèle,’” 123.)

- 36In 2002, a “best of” the discussions was broadcast without the archival footage, also directed by Didier Deleskiewicz, produced and broadcast as LES CARNETS D’HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE (26 episodes), they were available as video on demand from the Arte boutique. On Arte-Deutschland, the program was broadcast under the “appealing” title PROFESSOR FERROS GESCHICHTSSTUNDE (Professor Ferro’s History Hour).

- 37Ferro, “De la BDIC à Histoire parallèle,” 152.

- 38HISTOIRE PARALLÈLE was produced by Monteurs’Studio directed by Christine Morisset. For the archival rights and preparation of the broadcasts, Michèle Fournier, Pauline Kerleroux, Marie-Pierre Thomas and Matthias Steinle were responsible. See the interview with Pauline Kerleroux in Goutte et al., Les films de Marc Ferro.

- 39See Marc Ferro, “A propos d’ ‘Histoire parallèle’,” 121f.

- 40Alexander Kluge, “Das Nichtverfilmte kritisiert das Verfilmte” (1979), In Gefahr und größter Not bringt der Mittelweg den Tod: Texte zu Kino, Film, Politik, ed. Christian Schulte (Berlin 1999), 55–56.

- 41See the microhistorical analysis of Sylvie Lindeperg, “Night and Fog:” A Film in History, trans. Tom Mes, University of Minnesota Press, 2014 [2007].

- 42On the importance of “non-political,” entertaining subject matter, see Uta Schwarz, Wochenschau, westdeutsche Identität und Geschlecht in den fünfziger Jahren (Frankfurt a.M. 2002).

- 43Quoted by Julie Maeck, “Voir et entendre la destruction des Juifs d’Europe. Histoire parallèle des représentations documentaires à la télévision allemande et française (1960–2000),” dissertation, Université Libre de Bruxelles (2007), 502.

"Entretien avec Marc Ferro et Pierre Sorlin,” L’image d’archives. Une image en devenir, edited by Julie Maeck and Matthias Steinle. Rennes 2016.

Ferro, Marc. “A propos d’ ‘Histoire parallèle’” [1992], Cinéma et Histoire (Paris 1993).

Ferro, Marc. Cinema and History, translated by Naomi Greene. Detroit 1988.

Ferro, Marc. “De la BDIC à Histoire parallèle,” Matériaux pour l’histoire de notre temps 2008/1 (N° 89-90).

Ferro, Marc. Mes histoires parallèles. Entretiens avec Isabelle Veyrat-Masson. Paris 2011.

Ferro, Marc and Claire Babin. Revivre l’histoire autour d’Histoire parallèle. Paris 1995.

Garçon, François. “La réussite d’Histoire parallèle.” CinémAction: Cinéma et histoire autour de Marc Ferro 65. (1992).

Goutte, Martin and Sébastien Layerle, Clément Puget, Matthias Steinle (Eds.). Les films de Marc Ferro. Paris: Théorème, 2019. (forthcoming).

Hoffmann, Kay. “‘Sinfonie des Krieges’: DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU im Zweiten Weltkrieg.“ In Geschichte des dokumentarischen Films in Deutschland. Vol. 3 ‘Drittes Reich’ 1933-1945, edited by Peter Zimmermann and Kay Hoffmann. Stuttgart 2005.

Kluge, Alexander. “Das Nichtverfilmte kritisiert das Verfilmte.” In Gefahr und größter Not bringt der Mittelweg den Tod: Texte zu Kino, Film, Politik, edited by Christian Schulte. Berlin 1999.

Kriegel, Annie and Marc Ferro, Alain Besançon. “L’expérience de ‘la Grande Guerre’,» Annales ESC, n° 2, vol. 20 (1965).

Lagny, Michèle. “Historischer Film und Geschichtsdarstellung im Fernsehen.” In Die Gegenwart der Vergangenheit. Dokumentarfiln, Fernsehen und Geschichte, edited by Eva Hohenberger and Judith Keilbach. Berlin: Vorwerk 8, 2003.

Lindeperg, Sylvie. “Film Production as a Palimpsest.” In Behind the Screen. Global Cinema, edited by Petr Szczepanik and Patrick Vonderau. New York 2013.

Lindeperg, Sylvie. “Night and Fog:” A Film in History, translated by Tom Mes. University of Minnesota Press 2014.

Maeck, Julie. “Voir et entendre la destruction des Juifs d’Europe. Histoire parallèle des représentations documentaires à la télévision allemande et française (1960–2000).” Dissertation, Université Libre de Bruxelles, 2007.

Meyer, Jean Christophe. “Histoire Parallèle/Die Woche vor 50 Jahren (La SEPT/ARTE 1989-2001): Newsreels as an 'Agent and Source of History'.” VIEW Journal of European Television History and Culture 4 (Dec. 2015), http://ojs.viewjournal.eu/index.php/view/article/view/JETHC091/218.

Steinle, Matthias. “ARTE vor seiner Zeit? Deutsch-französisches Geschichtsfernsehen im Zuge des Elysée-Vertrags: La Grande Guerre / 1914-1918 / Der Erste Weltkrieg – eine WDR-ORTF-Koproduktion (1964),” Rundfunk und Geschichte 31.2 (2006).

Schifres, Alain. “La fin de l’histoire,” L’Express (Sept. 6, 2001).

Schvarzman, Sheila. “Constructing history on television: Marc Ferro and newsreels in Histoire Parallèle”, Tempo vol. 20, Niterói 2014, Epub Jan. 30 2015, http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/TEM-1980-542X-2014203622en.

Schwarz, Uta. Wochenschau, westdeutsche Identität und Geschlecht in den fünfziger Jahren. Frankfurt a.M. 2002.

Wenger, Klaus. “‘Historie parallèle’: Eine Dokumentationsserie über den Zweiten Weltkrieg von hoher Aktualität.” In Deutsch-französische Medienbilder: Journalisten und Forscher im Gespräch / Images médiatiques franco-allemandes, edited by Ursula Koch et al. Munich 1993.