Filmography of the Genocide

Official and Ephemeral Film Documents on the Persecution and Extermination of the European Jews 1933-1945

Table of Contents

Secret Publics

Digital Digging

Movie Theatre(s) of Memory

Filmography of the Genocide

Exacting the Trace

Destroyed Statues, a Bolex 16 mm Camera, and an Old Jeep

“…will you show that on your British television?” ACCEPTABLE LEVELS as Historiographic Metafiction

Work and Life

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Schmidt, Fabian, and Zöller, Alexander Oliver. “Filmography of the Genocide: Official and Ephemeral Film Documents on the Persecution and Extermination of the European Jews 1933–1945.” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces, no. 4 (February 2022): 1–160. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18245.

Chapters

1. Introduction

2. The Schulberg Report

3. The Heydrich Decree

4. Sources for Moving Images from the Genocide

5. Towards a Forensic Cinema

6. Methodological Notes

7. Filmography (incl. map)

8. Bibliography

1. Introduction

By order of 12 November 1941, Reichsführer SS [Heinrich Himmler] has prohibited the taking of photographs during executions and ordered that, if such photographs were necessary for official reasons, the entire material be archived. (Reinhard Heydrich, April 1942)1

It has now been definitely established that at least one secret film on concentration camp atrocities and other Nazi cruelties has been made in Germany for a select audience of top Nazi officials. (Budd Schulberg, September 1945)2

Let them film! Let them film as much as possible! So a filmed documentation will remain of the situation brought upon a community of four times 100.000 Jews! They have the ability to create such a document. The editing and commentary are unimportant. They should leave a sneak view of the Jewish passerby on the crowded streets in the movie. The faces, the eyes that in future years will shout out in silence. They should all be commemorated; the droves of beggars, the people of yesterday slowly dying from the hardships and starvation in the closed ghetto. And another thing, the main one – they should add the German participants in this drama. They are the lead actors in this play. (Diary of Rachel Auerbach, 1942, p.3.)3

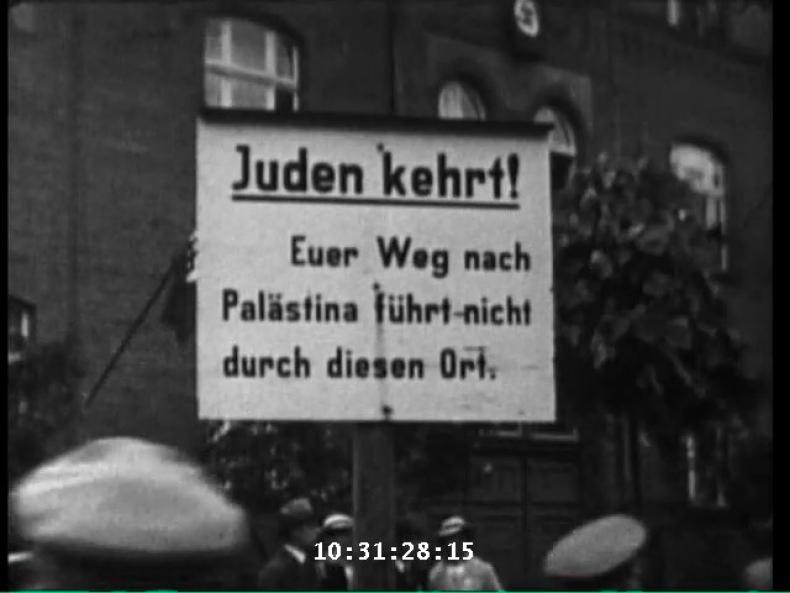

One of the self-evident and most prevalent historiographical assumptions tied to the Holocaust is that close to no film footage and photographs from the actual process of annihilation survived. Even the very notion that such material was produced in the first place has on occasion been dismissed: Why would the perpetrators have decided to leave such palpable evidence of their crimes? The assumption of the non-existence of film records seems to be supported by the few published filmography stubs such as the one from Jean-Michel Frodon (Cinema and the Shoah, 2010) which comprises no more than 40 archival convolutes and propaganda films. The finding aid “Jüdisches Leben und Holocaust im Filmdokument 1930–1945” (“Jewish Life and Holocaust in Film Documents 1930–1945”) compiled by the German Bundesarchiv lists quite a large number of archival materials, including newsreels, though often without clear references to provenance or whereabouts and with a rather vague focus.4 To the best of our knowledge, no prior effort has been undertaken to compile a comprehensive list of archival film material related to the genocide, including film materials which are only mentioned in contemporary sources, or which were only reported by witnesses after the war. A tabulation which encompasses lost films, if indeed there is considerable evidence for them, is bound to upend the prevailing notion that filming during the genocide was highly exceptional and mostly carried out in the handful of instances surviving as archival material today.

The reasons for the reluctance when it comes to filmic or photographic evidence of the Holocaust are manyfold and range from fear of the content to a hope for a lack of evidence due to a guilt-conscience on side of the perpetrators. Often, the alleged absence of cameras in the camps and ghettos ostensibly underlines the clandestine character of the genocide, as in Gideon Greif’s text about Lili Jacob and the Auschwitz Album, where he describes the arrival of the transport to Auschwitz-Birkenau from May 24, 1944 that was photographed for the so-called Auschwitz Album:

They held no revolvers or whips in their hands; instead, they were holding something that, until that day, had never before been seen in Auschwitz Birkenau when Jewish transports arrived – a camera. Such an instrument in this place, which for the Nazi regime was the most clandestine and secret, had to be considered a very exceptional occurrence.5

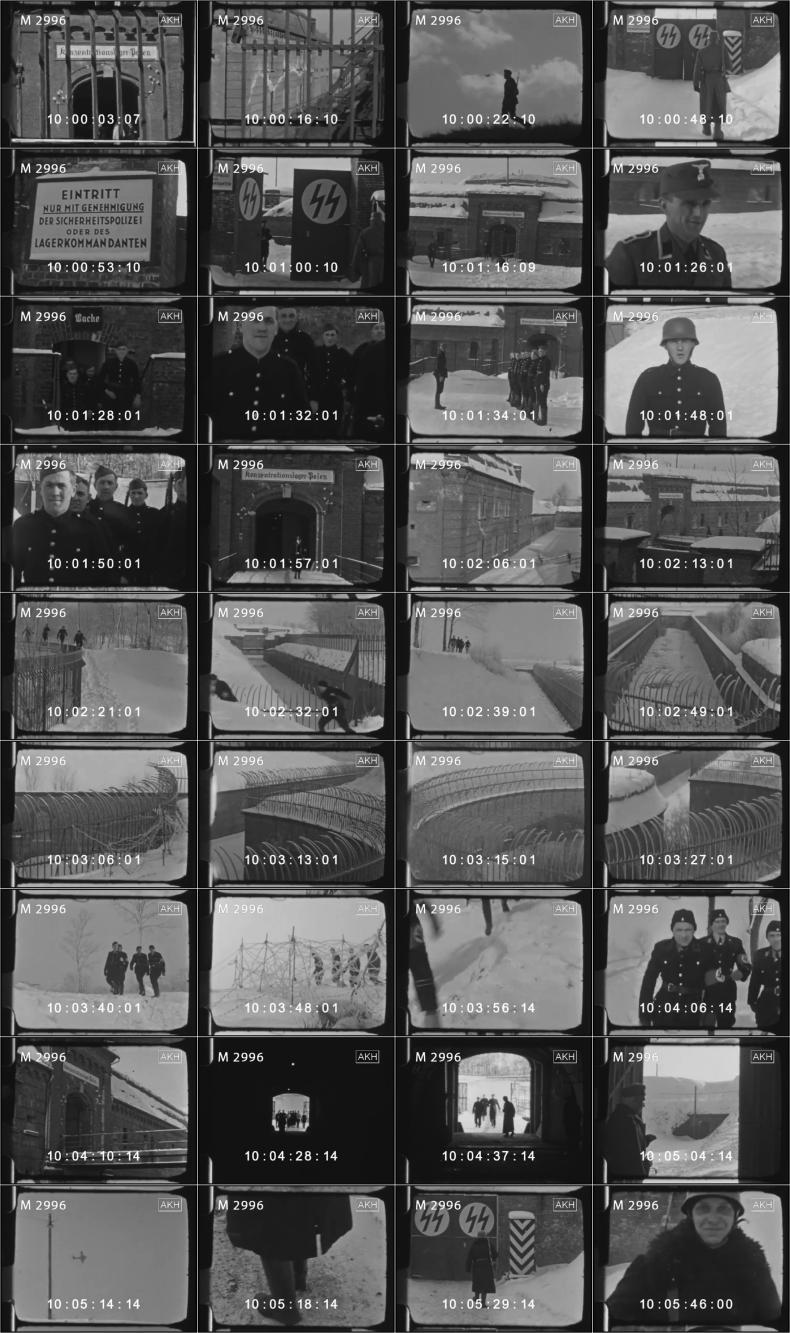

In fact, cameras and even film cameras were anything but an unusual sight in Auschwitz. Like Mauthausen, Westerbork, Theresienstadt, Dachau and many other camps and ghettos, Auschwitz had official photographers and a photo laboratory.

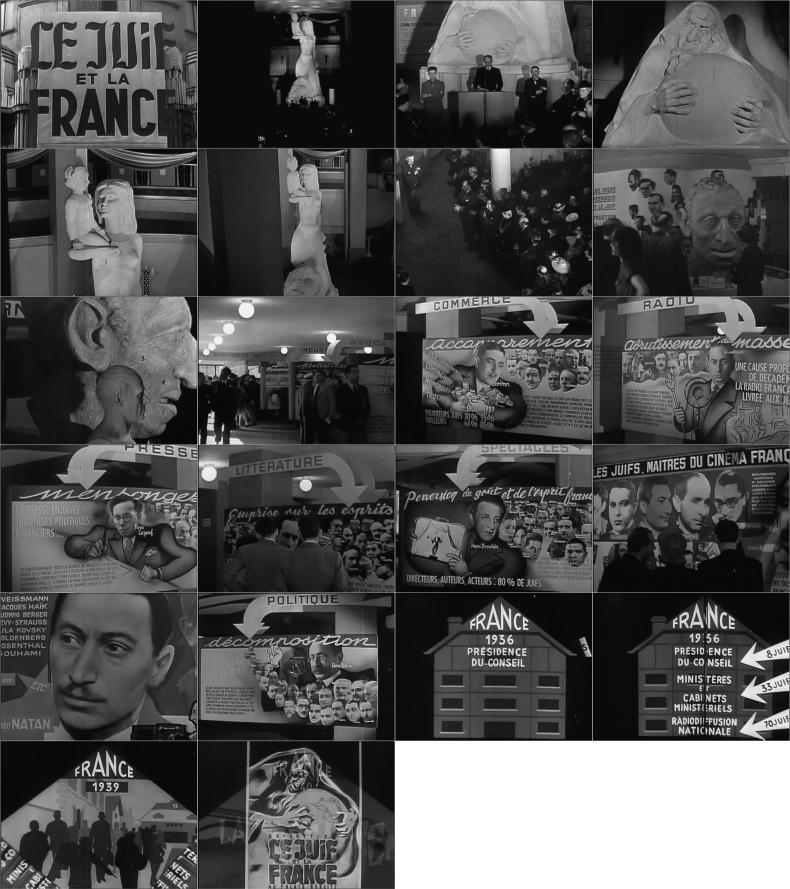

Possibly, this above mentioned scarcity of filmographic treatment is also connected to the disputes about the impossibility of a representation of the Holocaust which saw one of its peaks unfold around Claude Lanzmann’s cinematic milestone SHOAH (F/UK 1985) and the subsequent discussion about perpetrator footage in the context of Holocaust remembrances. Explicitly, the search for photographic evidence of the Holocaust in itself was equated with a tacit attempt to deny it.6 Today, the issue of permissible representation of the actual events appears to have changed. Given today’s knowledge about censorship of liberation footage on both sides of the Iron Curtain (e.g., the cancelled British production GERMAN CONCENTRATION CAMPS FACTUAL SURVEY and the largely censored Majdanek film of Aleksander Ford7), the question arises whether avoiding direct representation doesn’t run the risk of perpetuating such censoring practices. The discussion about the representation of the Holocaust today is less ideologically charged, which perhaps is also connected to the fact that it is much less in the center of attention. And also the proponents of the representation argument changed their attitude. SON OF SAUL (H 2015) for example visualised the mass murder in Auschwitz, and eventually even Claude Lanzmann approved of it.8 Claude Lanzmann, who became famous for his seminal ten-hour documentary SHOAH, exclusively consisting of testimony, even reconsidered his rejection of archive footage during the last phase of his career. The surprising, if scarce use of archival footage in his last documentary THE LAST OF THE UNJUST (FR 2013) perhaps can be considered as part of this broader shift of paradigm.

There also seems to be gradual change starting to happen in the pop-cultural approach to archival footage from the Holocaust. While the dominant historiographical discourse and even more the public remembrances are either busy ignoring or mourning the allegedly missing films and photographs, documentaries shown during film festivals like the very recent À PAS AVEUGLES / FROM WHERE THEY STOOD (Christophe Cognet, FR 2021) or Mar Targarona’s feature film EL FOTÓGRAFO DE MAUTHAUSEN (ES 2018) deal with filming and photography in the concentration camps and with the fact that it was, not unlike today, widely ignored at the time.

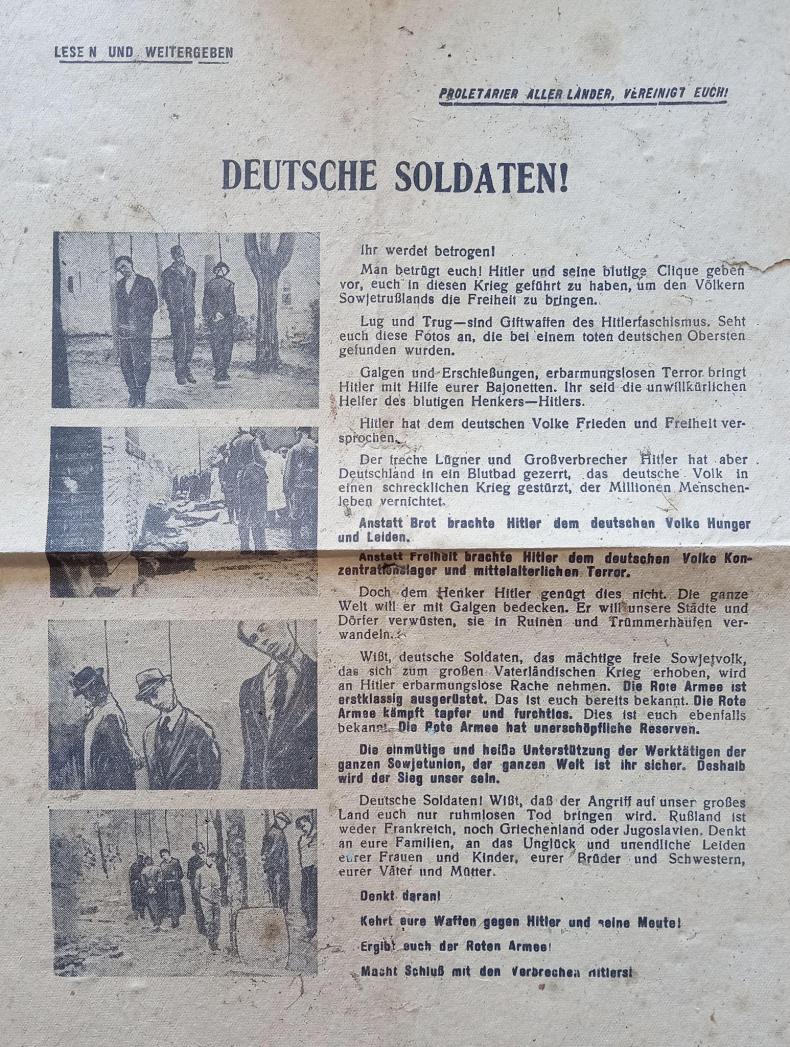

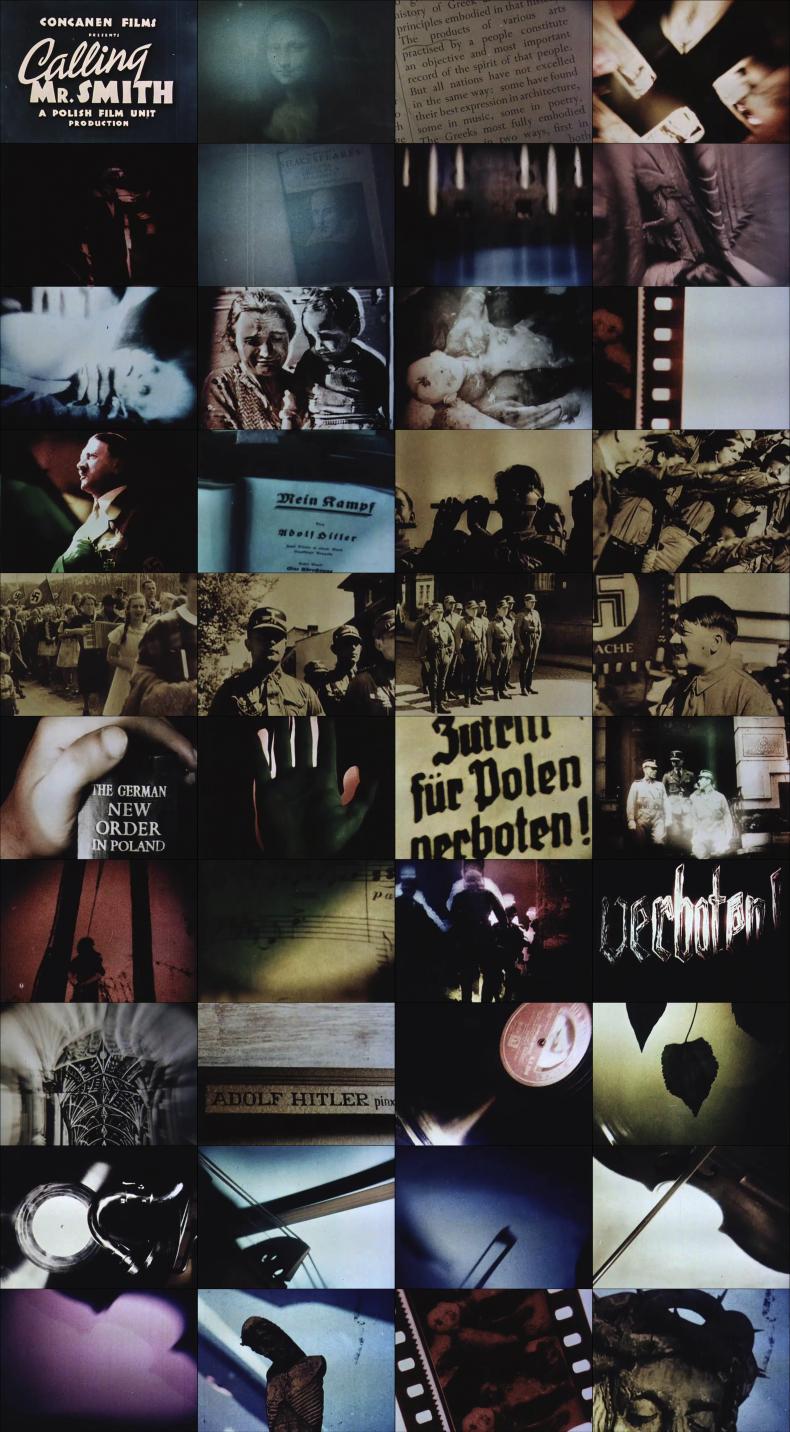

Strikingly, photographs and film stills showing German atrocities were circulated outside the Third Reich as early as 1941. Photographs from the reprisal execution in Pancevo for example already appeared in a Soviet propaganda leaflet, shown below, printed in the summer of 1941, only months after they were taken. These photos were most likely found among the belongings of a dead or captured German soldier who possibly had bought or traded them from another soldier. A large collection of 200 photographs with hanged or mutilated civilians and POWs can be found in the brochure “Soviet Documents on Nazi Atrocities,” published in 1943 in Great Britain. In the same year, the British short film CALLING MR SMITH (Franciszka and Stefan Themerson) used such photographs and even film footage from the ghettos in Poland in order to accuse the Germans of atrocities in the East.

So, perhaps, it is also time for historiography to acknowledge the fact that there has been, ‘and still is,’ a lot of photographic and film evidence of the genocide, much of which is still waiting to be fully analysed and assessed.

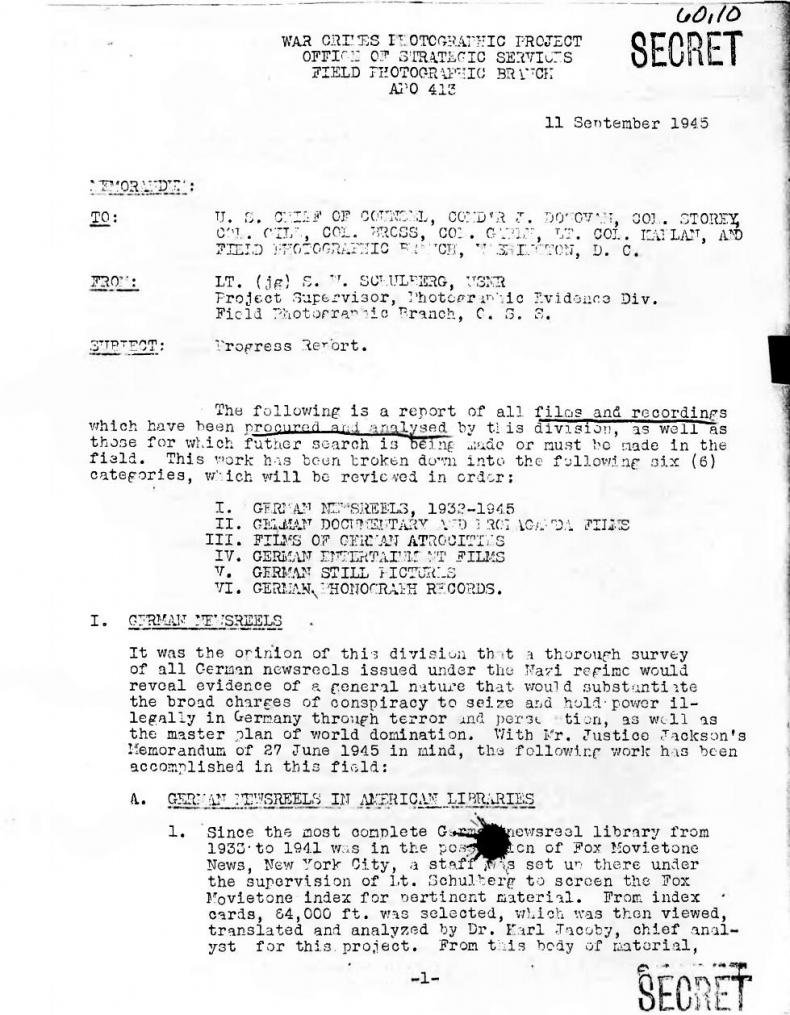

The beginning of the process which led to the filmography we are presenting here was the research for our still-ongoing documentary film project ATROCITY FILM.9 Intrigued by a status report by US Lt. Seymor W. (“Budd”) Schulberg from September 1945 and a fairly overlooked decree by Reinhard Heydrich from April 1941, we started to gather any traces of film activities in the context of the persecution and the genocide the Germans had unleashed mainly in Eastern Europe between 1941 and 1945. Schulberg claimed in his report to have found believable traces and testimonies of an Atrocity Film, a secret SS film project documenting the Holocaust. Reinhard Heydrich, cited above, in 1942 specified Himmler’s ban of photography during executions, originally issued in November 1941, and emphasised an aspect of Himmler’s initial decree that so far has not been acknowledged by historians: the order that all films and photos of executions were to be sent to and centrally collected at the RSHA (Reichssicherheitshauptamt) SS headquarters in Berlin. The combination of these two documents called for a broad search for traces of these archive films. We were successful in finding traces, much more than we had imagined. While the filmography we gathered this way merely served as proof for the theory of the Atrocity Film, it became clear to us that the majority of these film materials had not been acknowledged by historians, not to speak of the vast amount of footage mentioned in official and personal reports that has not yet surfaced and that indicates an almost seamless documentation of the genocide through its various stages. Hence, we decided to publish a full filmography, a filmography of the genocide, as we’d like to call it in order to distinguish it from Ronny Loewy’s Cinematography of the Holocaust, which has a far broader approach (including fiction film) and which at some point will be the larger host archive for our much smaller, specific collection.10 This introductory text is about our initial reasons to produce this filmography but at the same time seeks to point to the various opportunities this collection offers. Our latest publication “Atrocity Film” in Apparatus Journal gives a broader overview on the hypothesis of the SS Film and its traces uncovered so far.11

2. The Schulberg Report

During World War II, U.S. Navy Lt. Budd Schulberg was assigned to the Field Photographic Branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the direct precursor of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), working with John Ford’s documentary film unit. In 1945, Ford gave Schulberg and his fellow officer Ray Kellogg the order to locate incriminating motion picture film evidence that could be used against the Nazi perpetrators at the Nuremberg trials. Schulberg’s mission resulted in the OSS War Crimes Project amassing a considerable body of newsreels, documentary and propaganda films as well as photographs and other records, many of which had been seized from captured Nazi sources. In September 1945 Schulberg filed a report for his OSS superiors in which he gave a detailed account of any such efforts undertaken thus far.12 In section III. he lists what he calls “films of German atrocities” or simply: “Atrocity Film.” Under subsection D “German sources” he states that

[...] it has now been definitely established that at least one secret film on concentration camp atrocities and other Nazi cruelties has been made in Germany for a select audience of top Nazi officials.13

In the following pages of the report Schulberg explicitly names several sources who claim to have either seen the film or at least have knowledge about participants, content, and possible whereabouts of the physical film elements. Schulberg further reports that his efforts to find the film had been unsuccessful thus far, as three of the film storage sites of the former Reichsfilmarchiv, in Rüdersdorf, at the Olympic stadium in Berlin, and in a salt mine at Grasleben were burnt down or otherwise destroyed shortly before his arrival, while other such film vaults were still waiting to be examined.

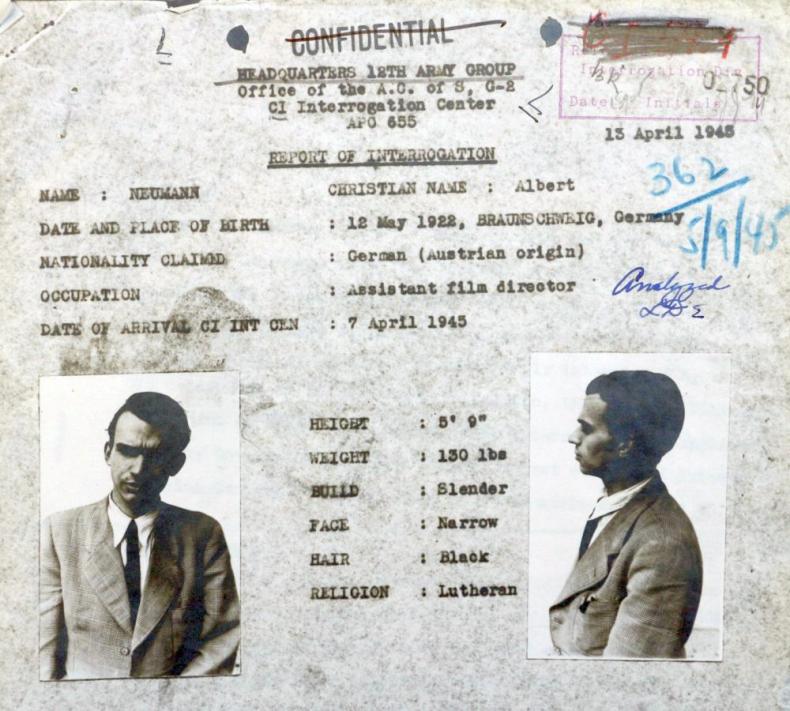

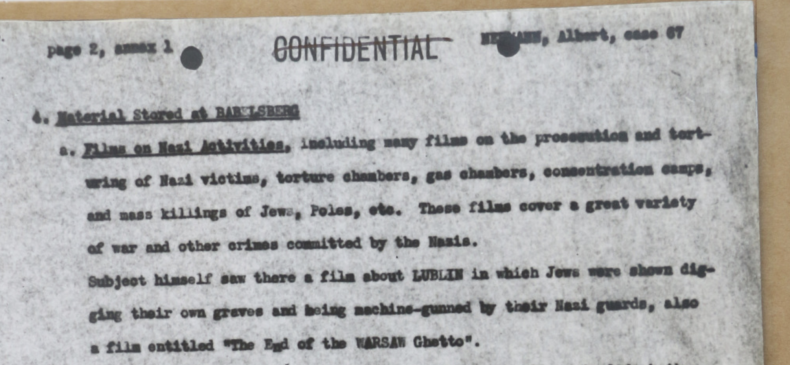

One of the sources Schulberg refers to is Albert Neuman, a German citizen and former employee of the Reichsfilmarchiv who defected to the Allies in March of 1945. Neumann’s interrogation resulted in the Nazi film archive being elevated to a Priority 1 target in the SHAEF intelligence target reports, with U.S. forces being ordered to secure its vaults and storage sites, including the main compound outside Babelsberg, by all means possible.14 Neumann stated that he had actually seen footage “showing SS massacre of Jews in Warsaw, mass murder of Russians and Poles, gas chamber tortures and other crimes.” In the corresponding file of his first interrogation, Albert Neumann claims more precisely to have watched a film “about LUBLIN in which Jews were shown digging their own graves and being machine-gunned by their Nazi guards.”15 It should be noted that Neumann’s descriptions are comparably detailed and hint to an unusual level of knowledge about the genocide. His account is fairly descriptive, and the number of collaborators listed by Schulberg is considerable. Schulberg attributed all this information to sources he considered credible, leading him to believe in the existence of such an atrocity film, and that further OSS efforts to locate the film were warranted.

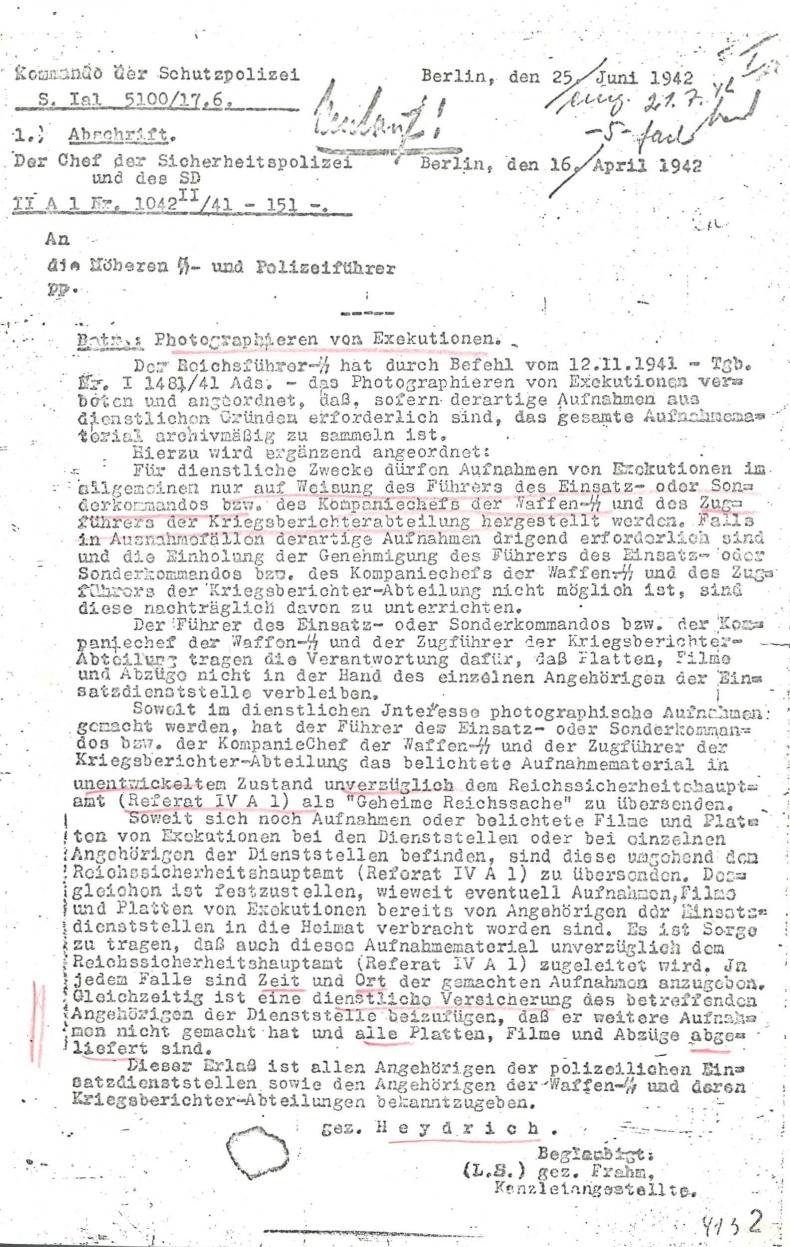

3. The Heydrich Decree

As outlined by Bernd Boll, and contrary to widespread assumptions, no general ban on private filming and photographing for military personnel existed in Nazi Germany. The only exception was the German Navy. In all other areas bans were limited, either temporally or spatially (Boll undated: 2). In general, the photographing of strategically sensitive objects such as airports, military installations or certain civil engineering structures was forbidden. The often public executions and the life in the camps and ghettos somehow were borderline cases that attracted film amateurs. Due to the ongoing, widespread practice of taking photos by military personnel, including ordinary soldiers of the Wehrmacht who participated in executions as spectators and onlookers, if not perpetrators, photo bans were issued in various contexts, including a decree by Himmler from November 1941. This ban was addressing SS personnel and specifically regulated the photographing of executions. Even if the SS would have obeyed this decree, it did not extend to the majority of uniformed units involved in the killings, such as the Wehrmacht and German Police. But Himmler’s photo ban for the SS, which has not survived, most likely did more than just ban photographing. It was renewed and altered by Reinhard Heydrich in March 1942. But instead of only reaffirming the ban, Heydrich specified that all photos and films that had so far been taken were to be sent as top secret material (Geheime Reichssache) to the RSHA in Berlin. Striking about this order is the fact that Heydrich explicitly demanded to contextualise the footage “in every case” by specifying date and place and that he referred to the earlier decree by Himmler (from November 12, 1941) as mandating the “archival collection” of all existing footage (“archivmäßig zu sammeln”) at Referat IV A 1 of the RSHA. It seems unlikely that the RSHA would have been tasked with collecting those films and photos for the sole purpose of destroying them. This could have been achieved much more easily by ordering such material to be destroyed by commanding officers in situ.

Himmler’s photo ban from 1941 is usually referred to not in the form of the original decree which has not survived, but through a later order by Himmler himself from 1944, where he reaffirms the ban without repeating its details (most likely the original decree was expected to be known and available to every officer). When Heydrich paraphrases the photo ban in 1942, however, he talks, in somewhat greater detail than Himmler did in 1944, about the need of systematic and archival (“archivmäßigem”) film collecting. We might conclude that Himmler’s initial ban has been mistakenly assumed to be a simple ban on photography, when it in fact represented the beginning of collecting film footage and photographs of atrocities. In this perspective Heydrich mainly gave more specific orders on how to label the films.

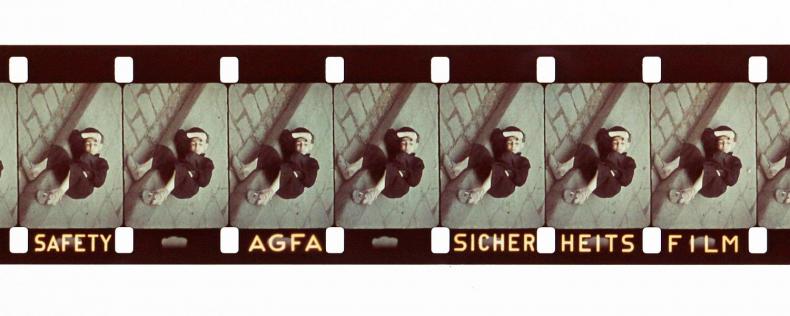

Given our general understanding about secrecy during the Holocaust, this interpretation of the Heydrich decree might seem sensationalist at a first glance. However, evidence exists that the described procedure of sending in films to the RSHA may in fact have taken place: Wilhelm Brasse, a Polish political prisoner who later became one of the photographers in Auschwitz, reported after the war that SS Hauptscharführer Bernhard Walter with his Agfa 16 mm film camera would film executions and that he “sent the original [film] to the RSHA in Berlin and later received a copy-print in return.” (Testimony of Wilhelm Brasse, 1984)16 It seems more than unlikely that Brasse would have had any reason to invent such a story.

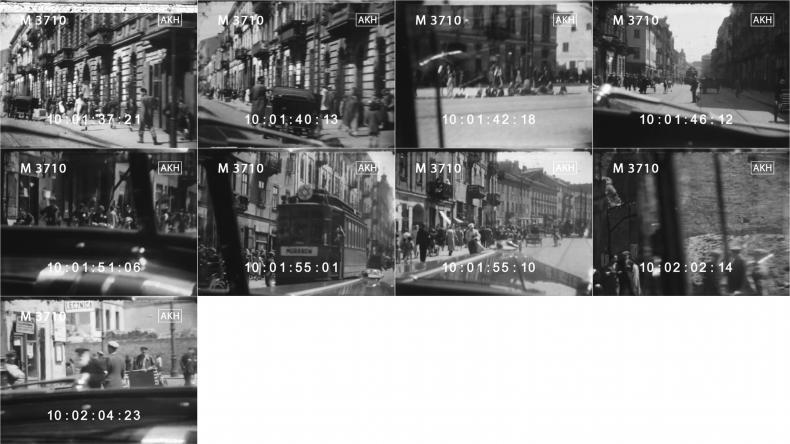

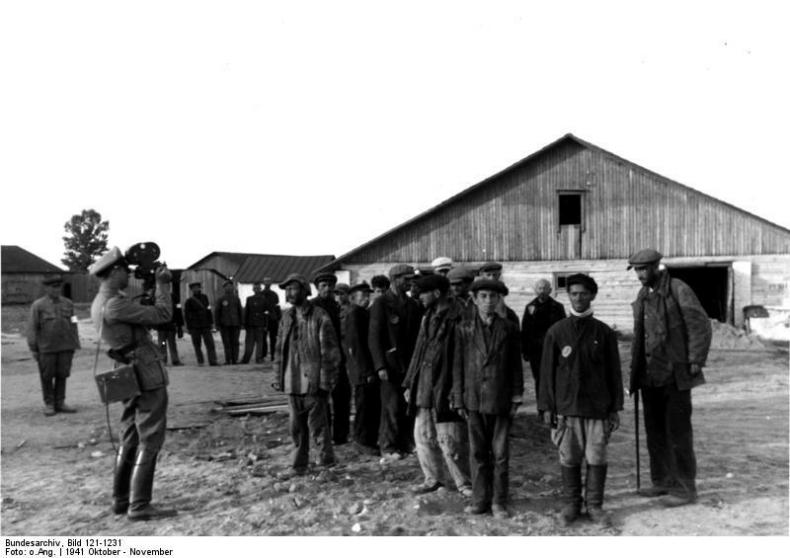

4. Sources for Moving Images from the Genocide17

In addition to a plethora of amateur filmmakers, such as German soldiers who filmed inside the ghettos, several institutions and entities of the Nazi apparatus were involved in filming the Holocaust and the steps that led up to it. Out of these professional groups, the Propagandakompanien (Propaganda Companies, or PK) arguably were the most active, not least because of the sheer amount of cameramen which they fielded, their far-flung operational area across all theatres of war and occupied Europe, and their unfettered access to film and camera equipment.

While the German Propaganda Ministry held discretionary power over the PK’s deployment and activities, it was the Wehrmacht who ultimately fielded the PK units, and its members were ordinary members of the German military. As such, they were subordinate to military orders—an arrangement which far transcended the modern approach of civilian “embedded correspondents.” In addition to the branch forces of the Wehrmacht—the Heer, Luftwaffe, and Kriegsmarine—the Waffen-SS also fielded its own PK units. Over the course of World War II, the PK employed more than 700 combat cameramen—the so-called Filmberichter—whose primary task was to shoot film for the weekly domestic newsreel, Deutsche Wochenschau. PK footage was also used in a number of propaganda films and various other newsreels produced for the occupied and neutral countries of Europe. By the end of the war, the PK’s film output amount to some five million metres of 35 mm film, though only about 300,000 to 500,000 metres ended up being screened. The remainder—by far the bulk of PK footage—was destroyed in a number of catastrophic nitrate film fires toward the end of the war. As such, historiography has struggled with assessing this vast body of lost film, being confined largely to the published films and newsreels, obviously a very carefully composed selection of material edited for the purposes of Nazi film propaganda.

The PK cameramen were instructed to shoot film with a view to produce suitable stories to be screened in cinemas, with maximum propagandistic effect, yet they also had the additional task to document the war for later, historical purposes: they also shot film for the archive. While the censors banned considerable swaths of PK footage from being released to newsreel companies or film studios, such material was nevertheless centrally collected and archived for its documentary value. All PK footage was archived at a special subsidiary office of the German Reichsfilmarchiv, the so-called PK-Filmstelle.

Even though the greater part of PK film footage ended up being destroyed, the surviving collections of PK photographs permit us to make assumptions as to what the film material may have contained: PK photography often moved along comparable film activities, with both a photographer and cameraman being assigned the same mission. Surviving series of PK photos cover various Jewish ghettos established by the Nazi occupants in Poland, of Jews being deported, and even from inside the Salaspils concentration camp near Riga, Latvia. On several occasions PK photographers shot pictures of mass executions and atrocities, and it is likely that the Filmberichter equally documented such events.

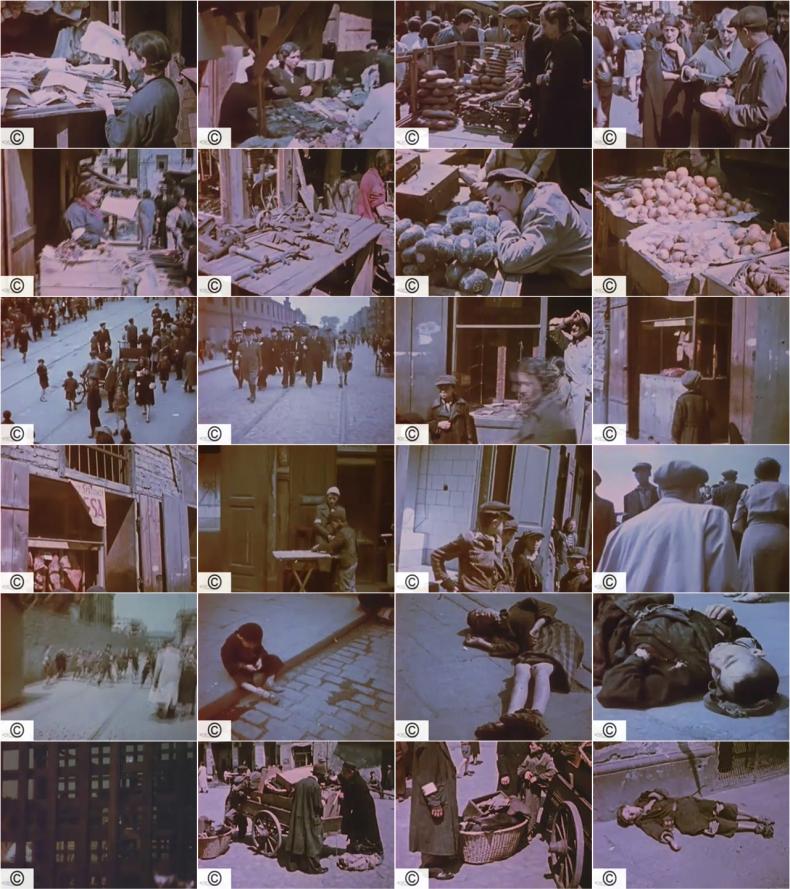

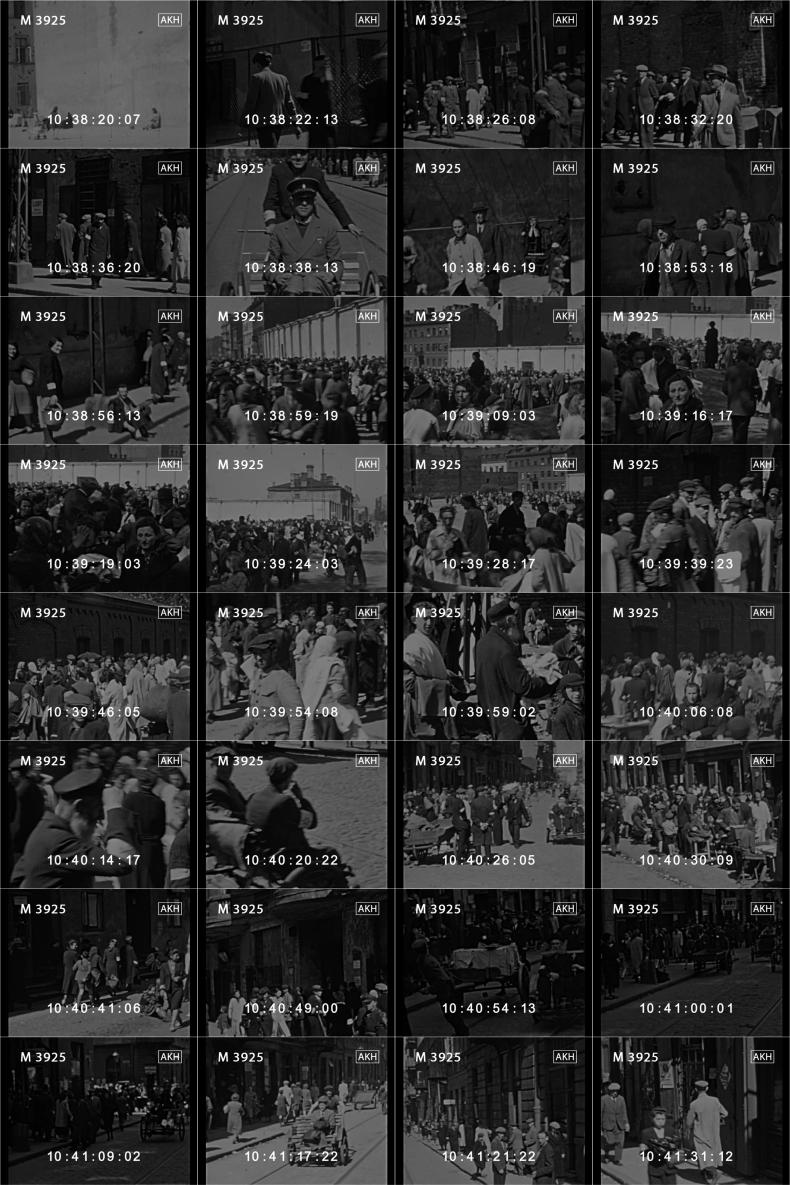

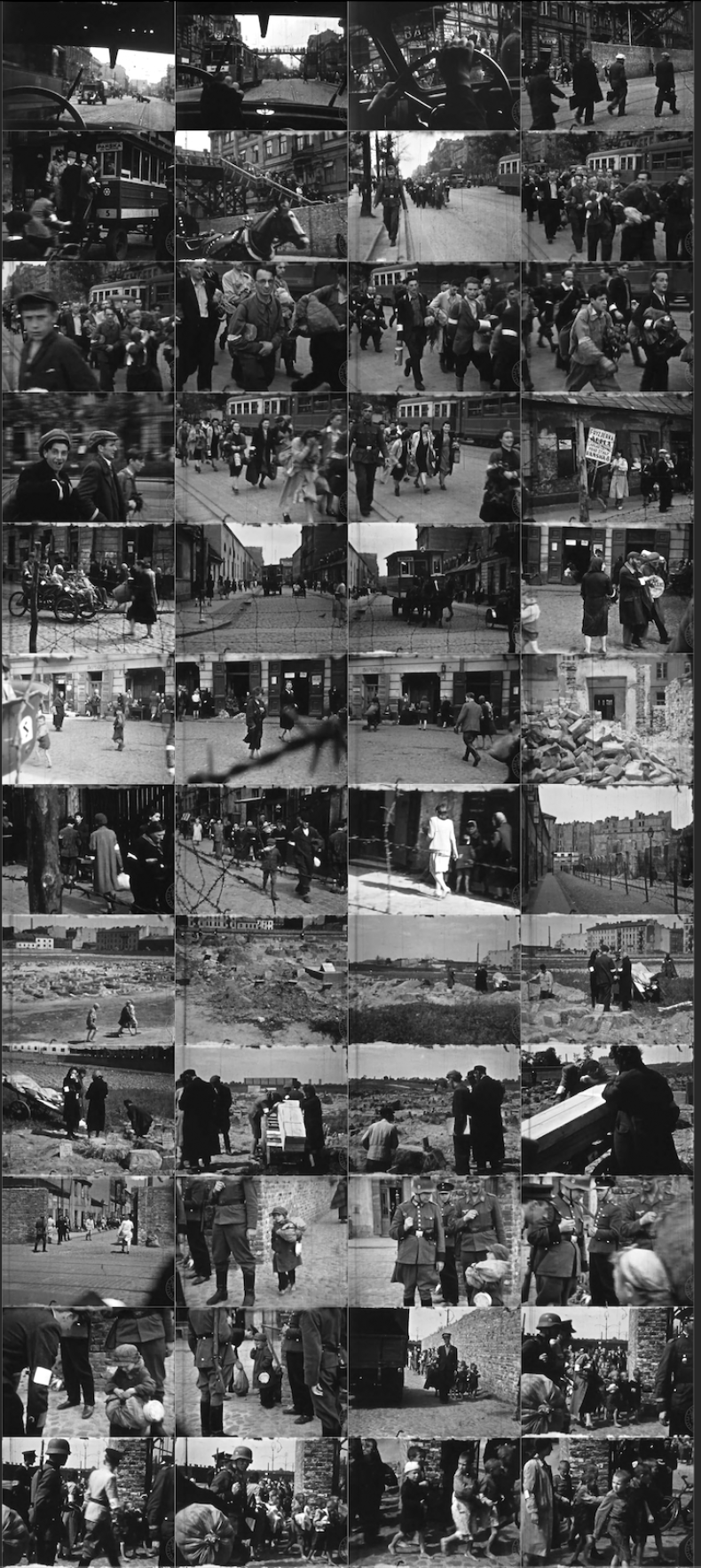

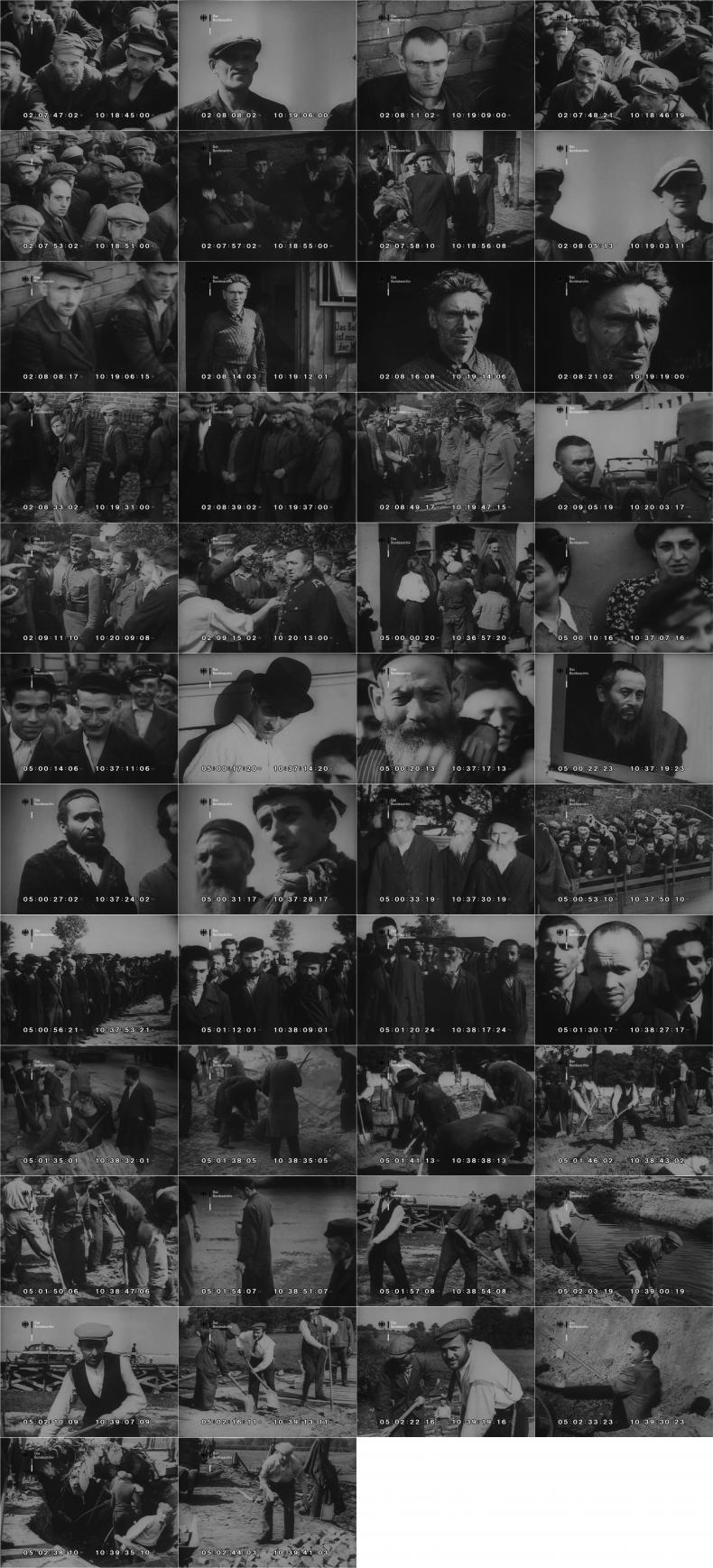

In a number of instances, PK cameramen—being the professionals at hand—were also drawn upon to shoot film for special projects, such as the 35 mm film from the Warsaw Ghetto shot in the spring of 1942, shortly before the commencement of mass deportations to the death camps. Finally, war correspondents of the SS were even attached to the SD’s mobile killing squads, the Einsatzgruppen. While the purpose of these “SS propagandists'” appears to have been largely in the area of so-called “active propaganda” (Aktivpropaganda) targeted at the civilian population of the occupied Soviet territories, as well as at enemy combatants, especially in the context of anti-partisan warfare, a documentary function in connection to mass executions and similar atrocities cannot be ruled out.

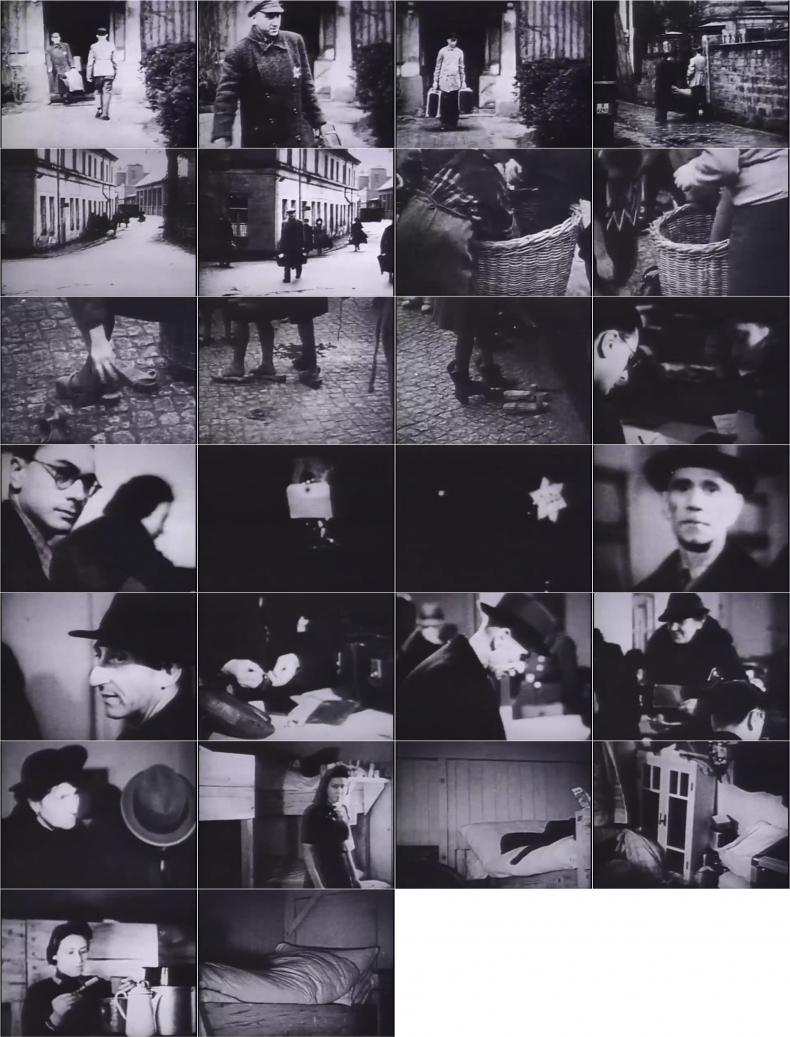

A second entity which more than likely was involved in filming the Holocaust was the SS itself, however far too little is known at present about the film activities of the SS and its various organisations. The SS had its own film department (Filmstelle) for which no appreciable archival record exists. More specifically, activities focused on the persecution, ghettoisation, and ultimately murder of Jews may have been spearheaded by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt (RSHA) and the SD. The RSHA had its own film and photography department, which initially was part of the RSHA’s Group II D (Technical Matters), itself a subsection of Amt II (Organisation, Administration, and Legal Matters) headed by SS-Obersturmbannführer Walter Rauff (1906–1984), who was instrumental in the implementation of the genocide using mobile gas vans. After a reorganisation in 1943 the film department was redesignated Referat II C 1 with the slightly altered purview of “Radio, Photography and Film.” With the possible exception of the Theresienstadt film from 1942, believed to have been initiated by the Sicherheitsdienst and at least partly shot in the presence of a SD cameraman, Olaf Sigismund, no film footage confirmed to have been produced by the RSHA is known to survive in archival collections today.

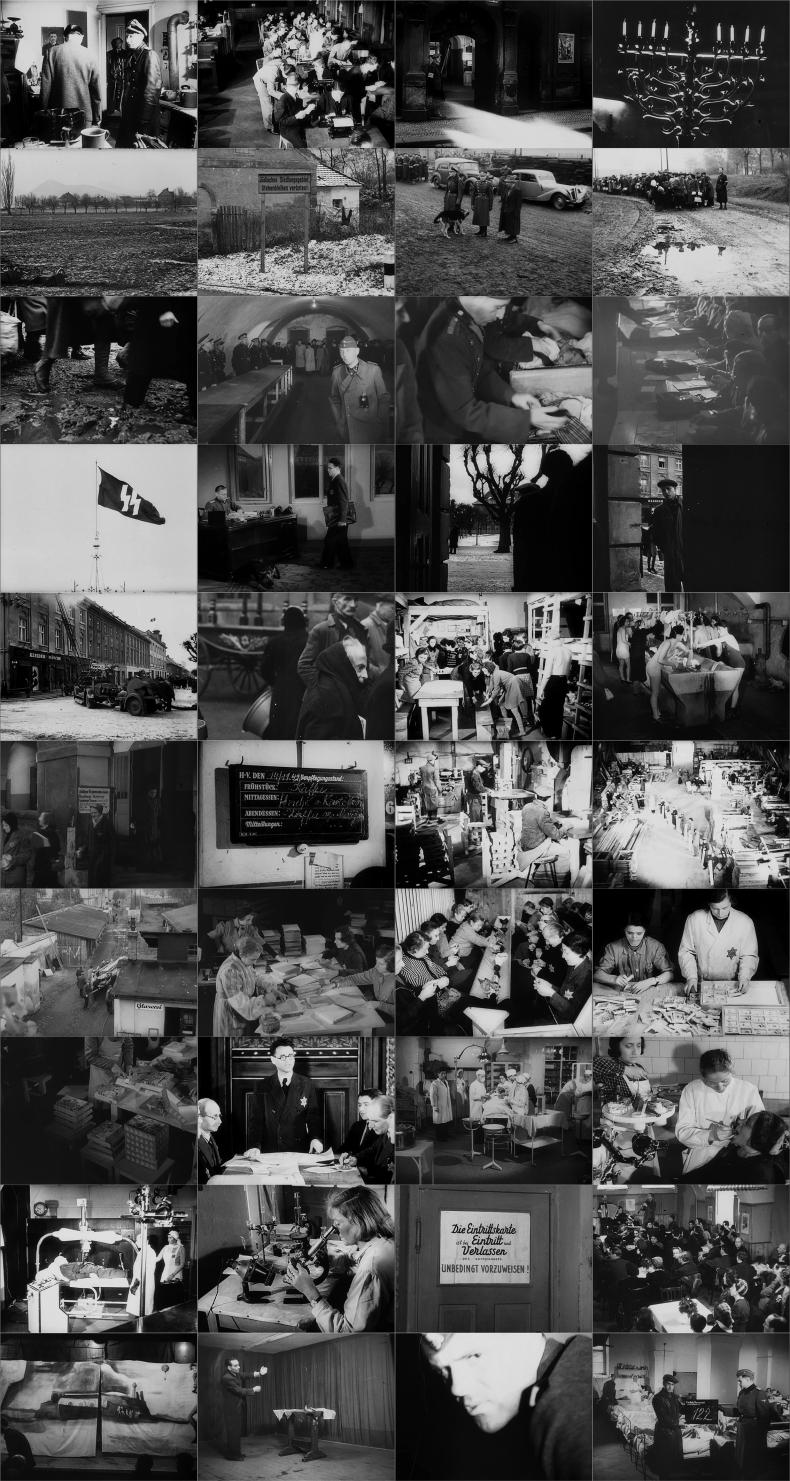

Several filming efforts in the context of the genocide were commissioned ‘locally’ by SS officers, specifically without prior consent of the RSHA. One could conclude that Heydrich was specifying Himmler’s decree because he had knowledge of such efforts and feared that these films and photos might fall into the wrong hands and backfire. However, one decisive aspect is worth highlighting once again: SS officers had several reasons to commission film productions, among them personal ambition (the hope to ‘surprise’ superiors who were all too cautious and unimaginative when it came to filming); the hope to produce evidence that cast them in a positive light (which cannot be fully ruled out in the case of Günther and THERESIENSTADT and seems likely in the case of Gemmeker in Westerbork); the desire for private or at least internal memorabilia; and the belief that they were responsible for this kind of propaganda within their own remit of power, combined with a certain jealousy or fear of intervention. All of these possible motives are based on one important prerequisite that filming at the time was an integral part of modern daily life.

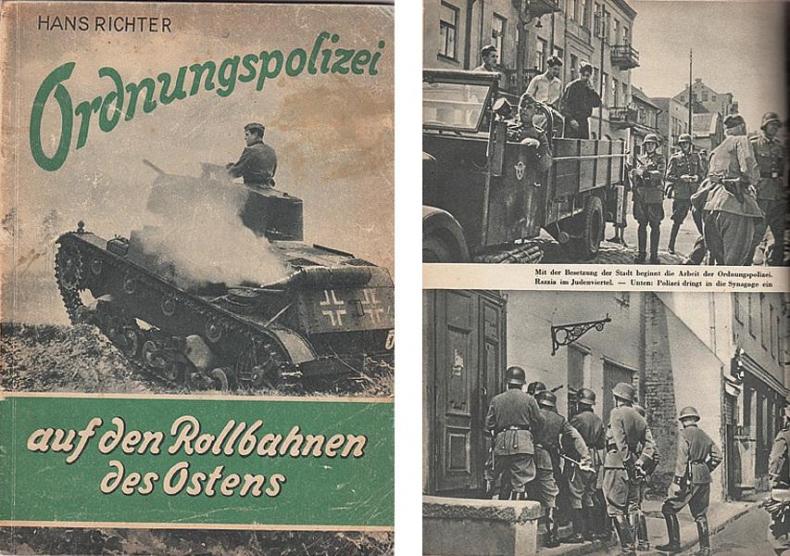

In a capacity very similar to the SS, various formations of the German police were also involved in film activities. Once again the activity of the respective Filmstellen is difficult to reconstruct due to a dearth of archival records. The Bild- und Filmstelle der Ordnungspolizei (Film and Photography Unit of the Order Police, or Orpo) demands special scrutiny. Ordnungspolizei troops perpetrated mass murder during the Holocaust and were responsible for a large number of genocidal crimes, including numerous mass executions.

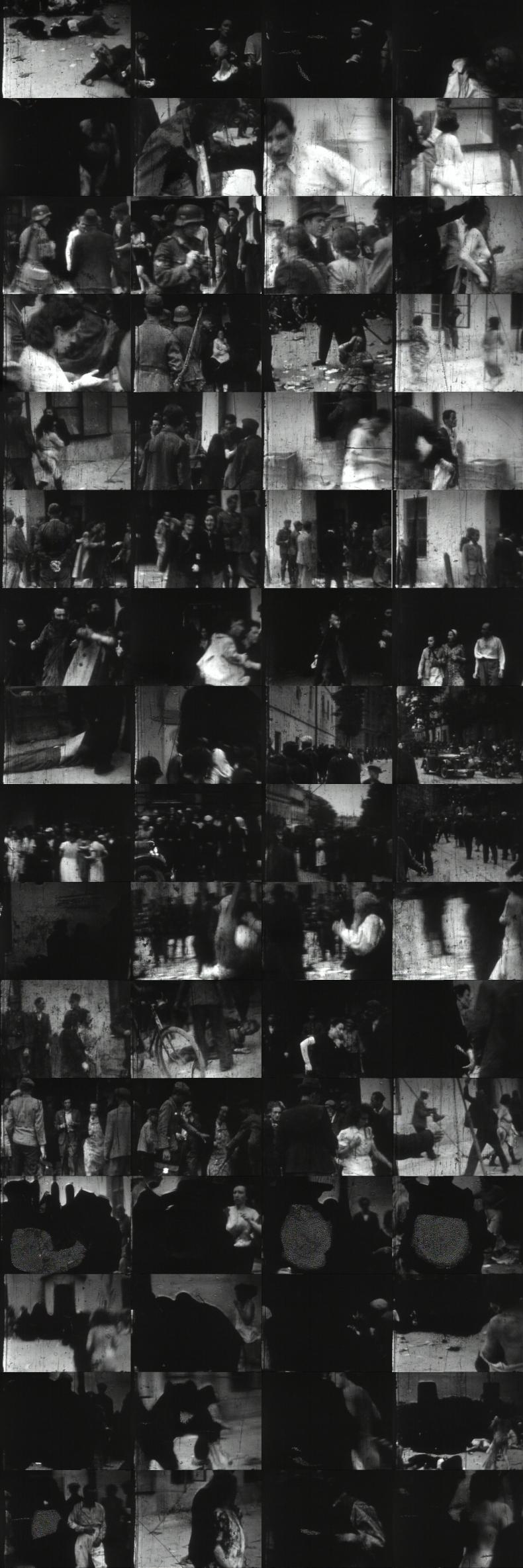

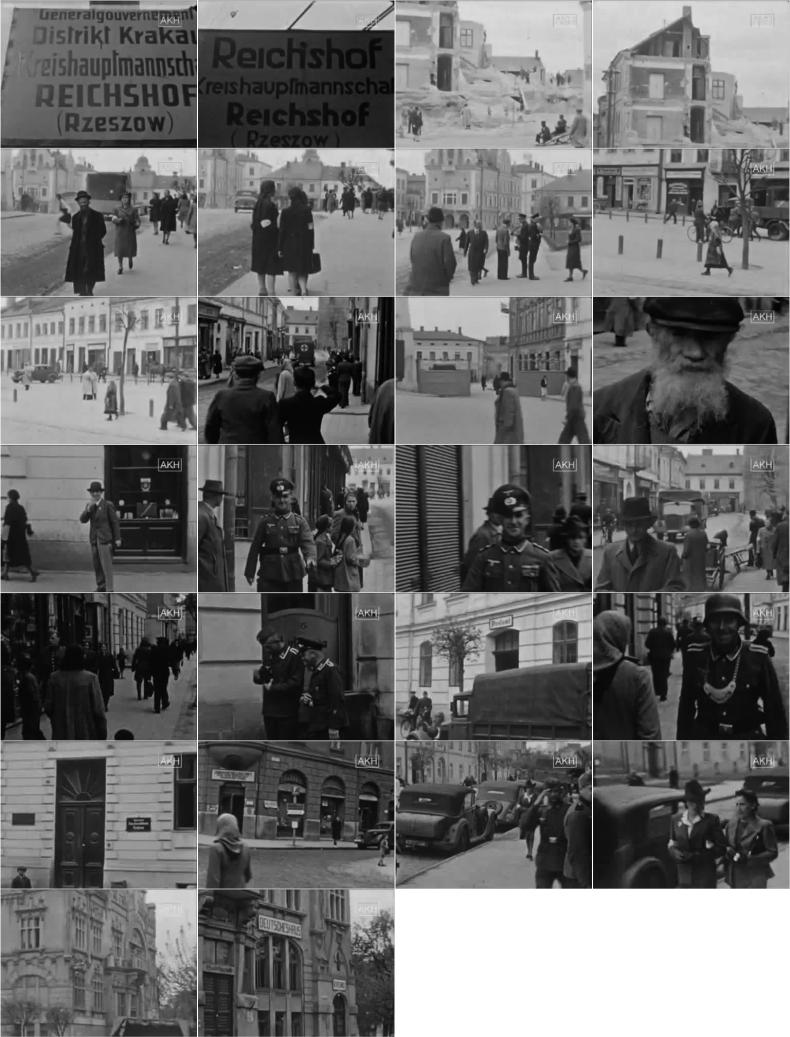

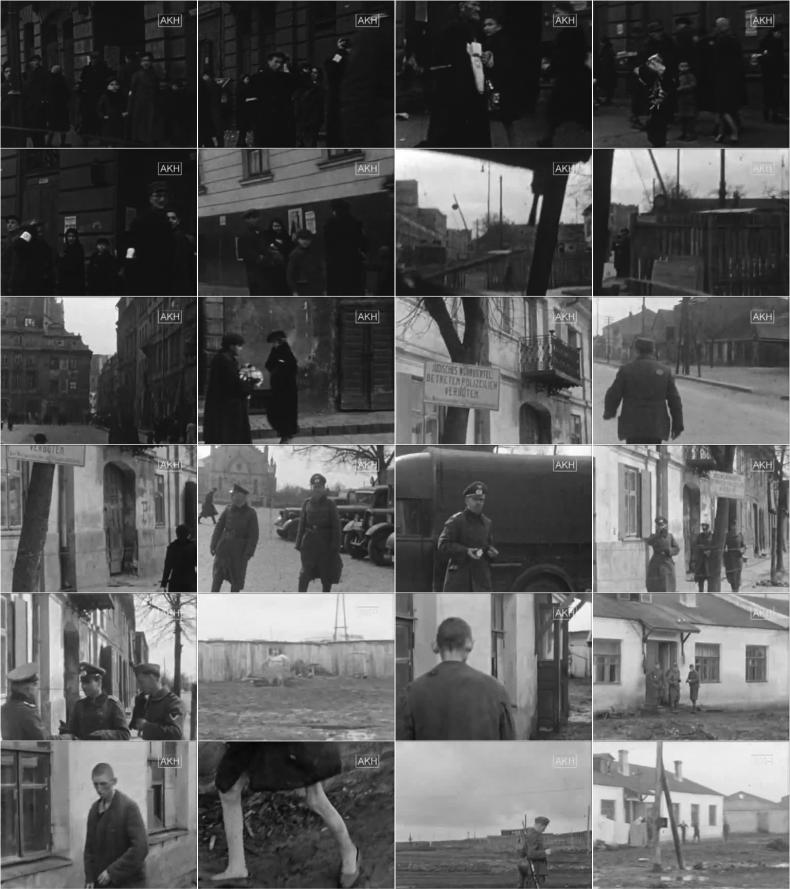

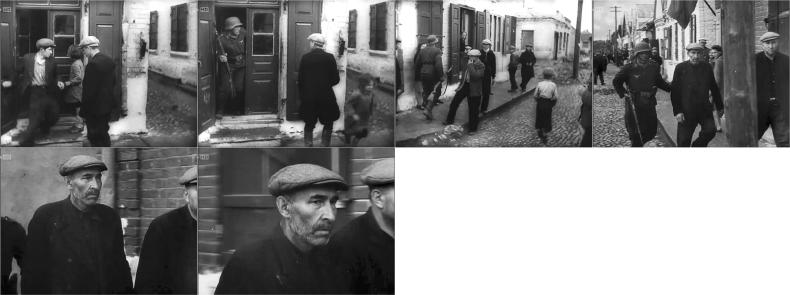

The Orpo’s Film- und Bildstelle fielded both cameramen and photographers, the latter of which took thousands of photos of Orpo operations. A 1943 brochure, “Ordnungspolizei auf den Rollbahnen des Ostens,” included a photo series of Orpo troops raiding the Jewish quarter and synagogue of a town in the occupied Soviet Union. The unit also produced a number of films, most of which have not survived. Congruous with similar losses incurred by the vaults of the PK film footage, the greater share of Orpo-produced audiovisual material appears to have been destroyed in the final days of the war. Only a few films that may have been produced by the Film- und Bildstelle have survived. DIE TÄTIGKEIT DER POLIZEI IM GENERALGOUVERNEMENT / POLICE OPERATIONS IN THE GENERAL GOVERNMENT, likely produced in 1941 by its immediate precursor (Film- und Bildstelle der Technischen Polizeischule) contains scenes of police raiding the Jewish quarter in Kraków, and of Jews being arrested and interrogated.18 Another film which now resides in the trophy collection of the Russian State Film Archive Gosfilmofond is even closer to actual documentary reporting and may be an indication that Orpo cameramen documented the war in a way similar to the PK.

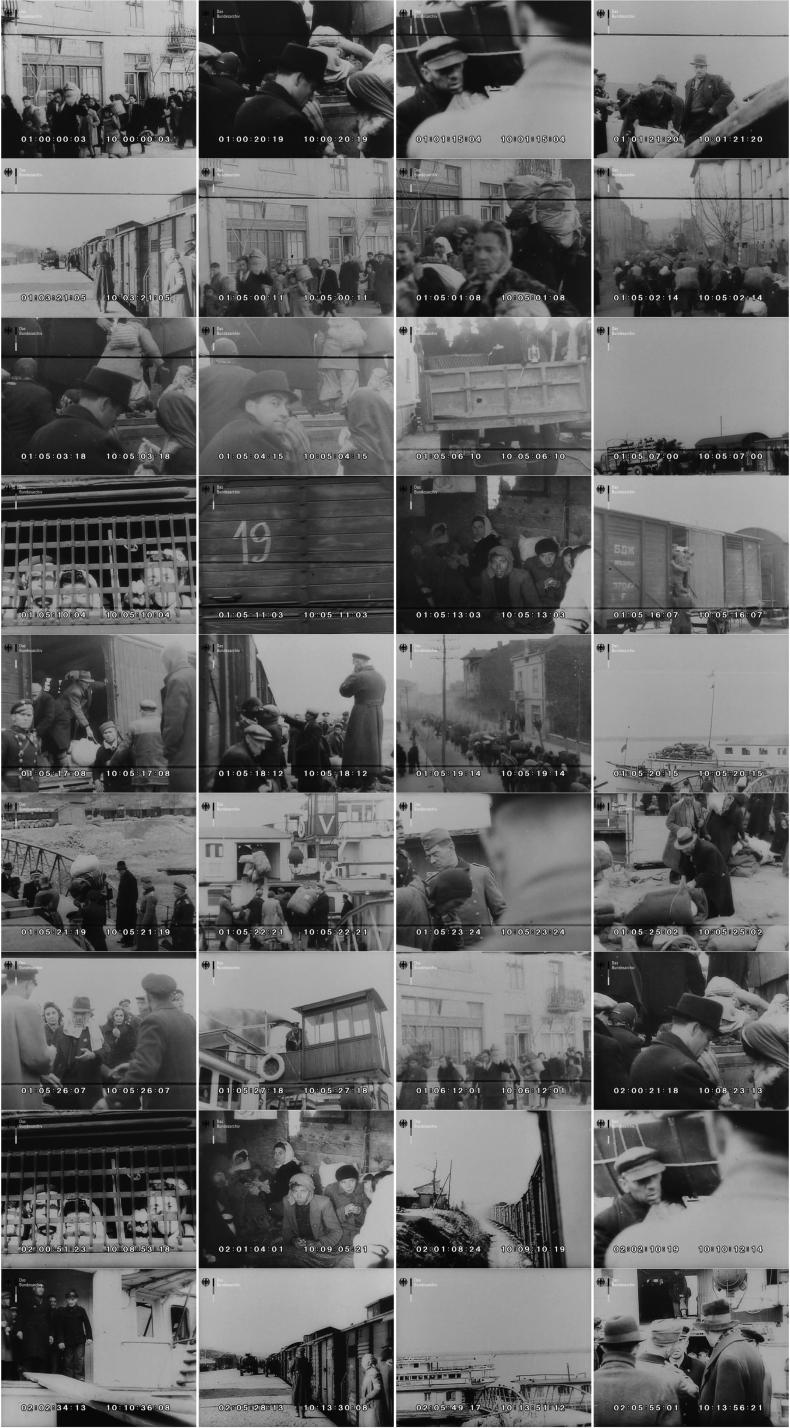

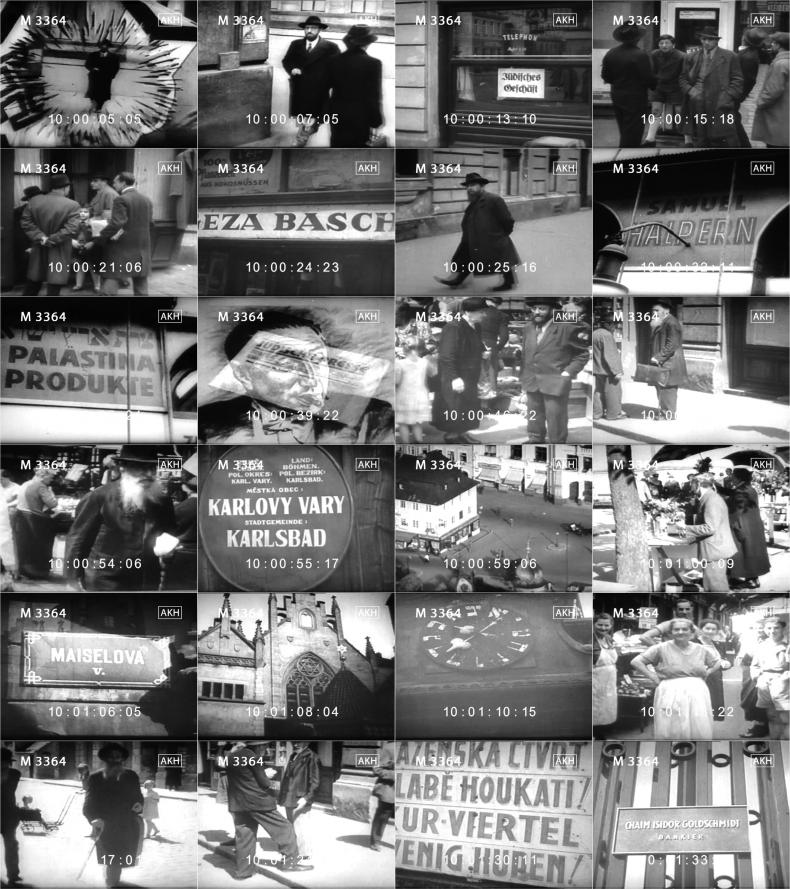

Perhaps surprisingly, staff members of the civilian newsreel companies were also implicated in relevant film activities. Cameramen of the German-controlled Aktualita newsreel in the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia were drawn upon to shoot the film THERESIENSTADT of 1944/1945, and they had previously been sent out to film the destruction of Lidice in 1942, razed to the ground in retaliation for the assassination of Reinhard Heydrich. In a similar fashion, in 1943 cameramen of the Bulgarian newsreel company Bălgarska delo shot footage of the deportation of Greek Jews from Thrace and of their transportation across Bulgarian-controlled territory.

Yet not only perpetrator footage survived. A number of films and photos shot in the context of the Holocaust were created by bystanders and in rare occasions shot by the victims, such as the four photos from the Sonderkommando in Auschwitz-Birkenau. These films cover incidents like trains with concentration camp inmates passing through smaller villages or even efforts by local resistance to film concentration camps and watchtowers, as in the case of the 8 mm material of the Plaszow concentration camp shot by Tadeusz Franiszyn.

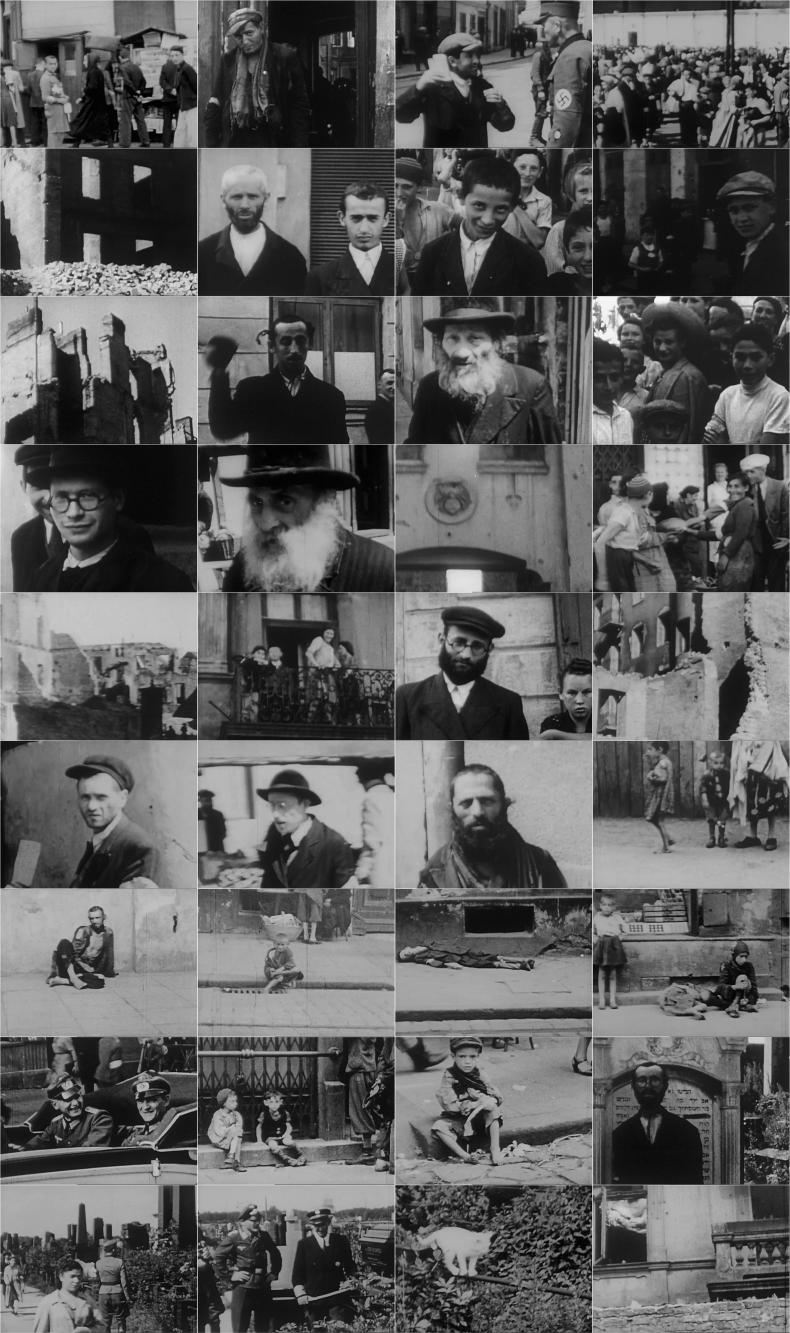

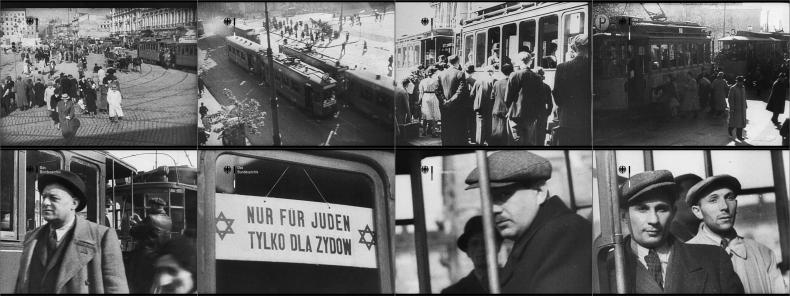

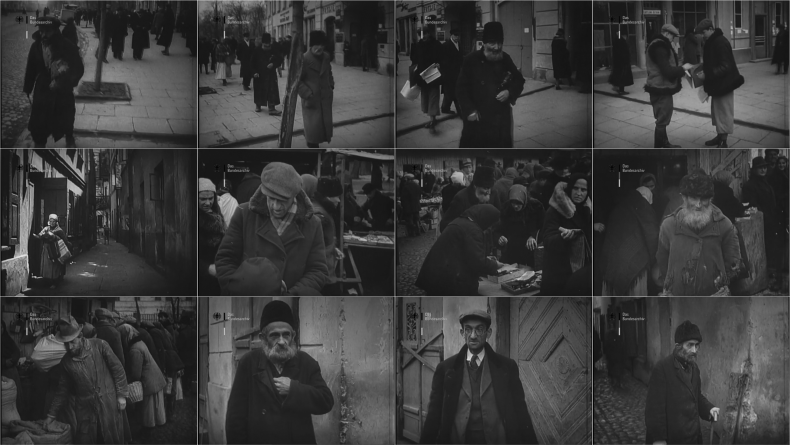

5. Towards a Forensic Cinema

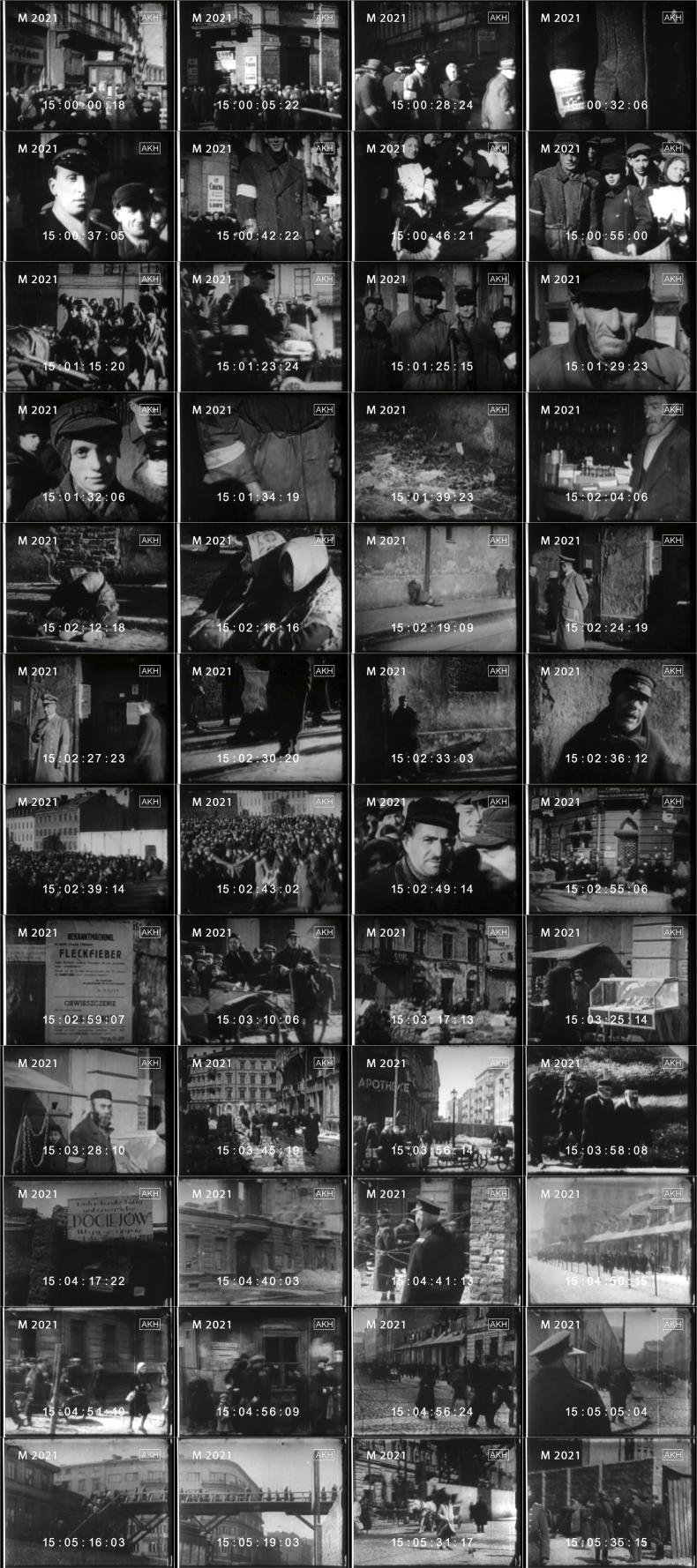

What do we hope to achieve by listing these films, including materials which have been lost or deliberately destroyed? This filmography is presented as an argument which concerns matters of historicization. While for the longest part of the postwar period film footage served as illustrations for the basic historicization of the Holocaust, an effort that required a lot of work and argument, we have already entered a new phase: local and micro histories command broader attention and films and photos increasingly are perceived as material evidence of the ‘cases’ they were supposed to record. This shift is partially made possible due to the fact that the Holocaust slowly ceases to be a matter of social debates about guilt and commitment, at least in Germany. And it goes along with a diminished reluctance to use such films on the side of historians. Still, to acknowledge that these films do not and cannot represent history but instead record single case structures cannot entirely clear out all reservations we have in terms of ‘the gaze’ inscribed in them. We are called upon to make aware the audiences watching these films of the ideological entanglements—and sometimes these entanglements are the only thing worth noting that has been preserved in these films. The case structures recorded in these archive materials are often inseparable from their ideological framing. Typically, the Wehrmacht soldier visiting the Warsaw Ghetto with his camera is not primarily documenting the housing situation of the Jews; he is aiming at feeding his prejudices. As such, these amateur films preserve something else: the perpetrator’s gaze19 on the situation in the ghetto. But at the same time, beyond restrictions that result from a selection of motifs and a selection of subjects that were not filmed and often go along with fear and hence atypical behavior on the side of the ghetto inhabitants being filmed, these films nevertheless offer an impression of what these ghettos looked like. Many of the moving images in question exhibit a twofold nature: they are ideologically framed and often staged representations, yet they are also indexical records of occupation and persecution, and often the only visual material in existence.

The importance to acknowledge this shift of perspective towards microhistory cannot be overrated, as this development runs danger to underestimate and to misjudge prior efforts of historicization in retrospect. A lot of the documentaries from before 2010 do not live up to today's expectations in terms of accuracy or case-oriented specificity. Archival footage was often used in a generally illustrative way, sometimes up to a disturbing extent. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that these movies are faulty or need to be corrected. They served a different purpose and still do so, rightfully.

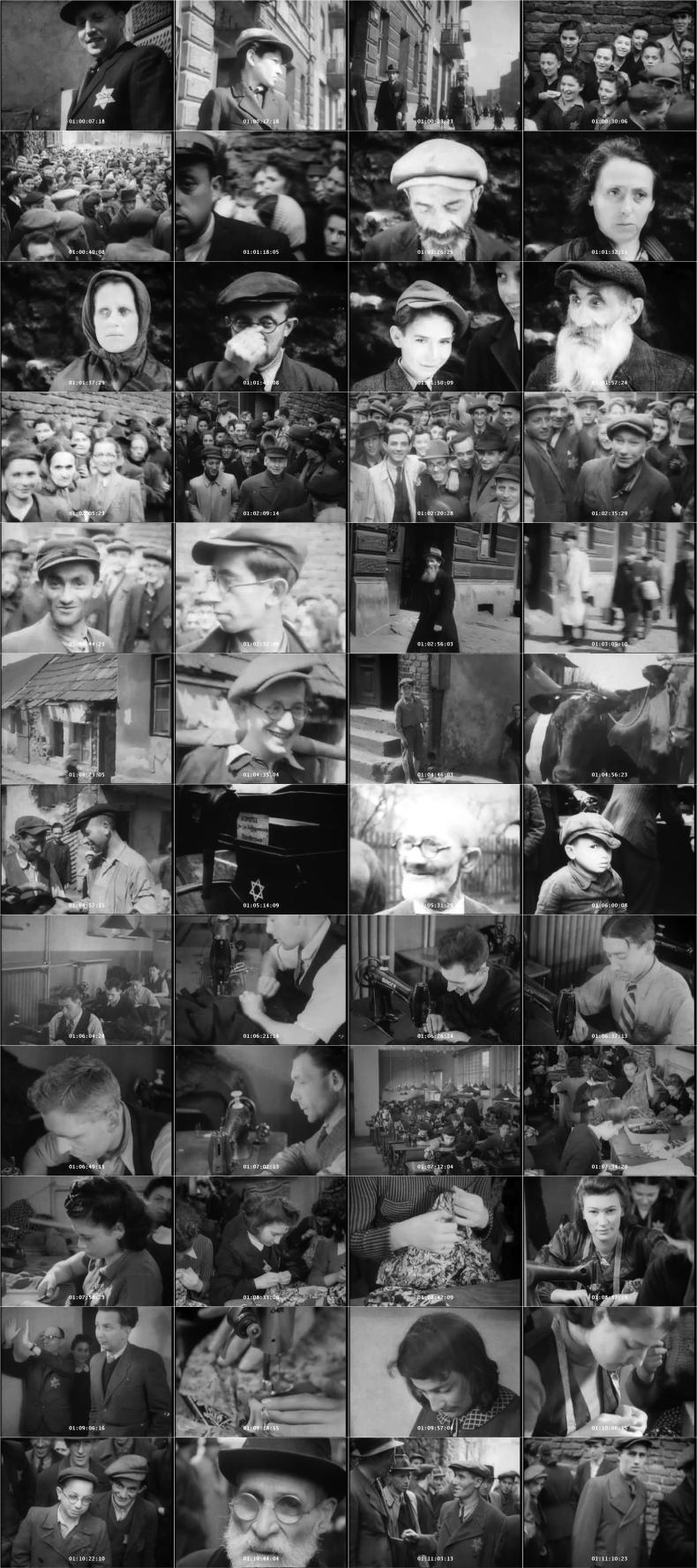

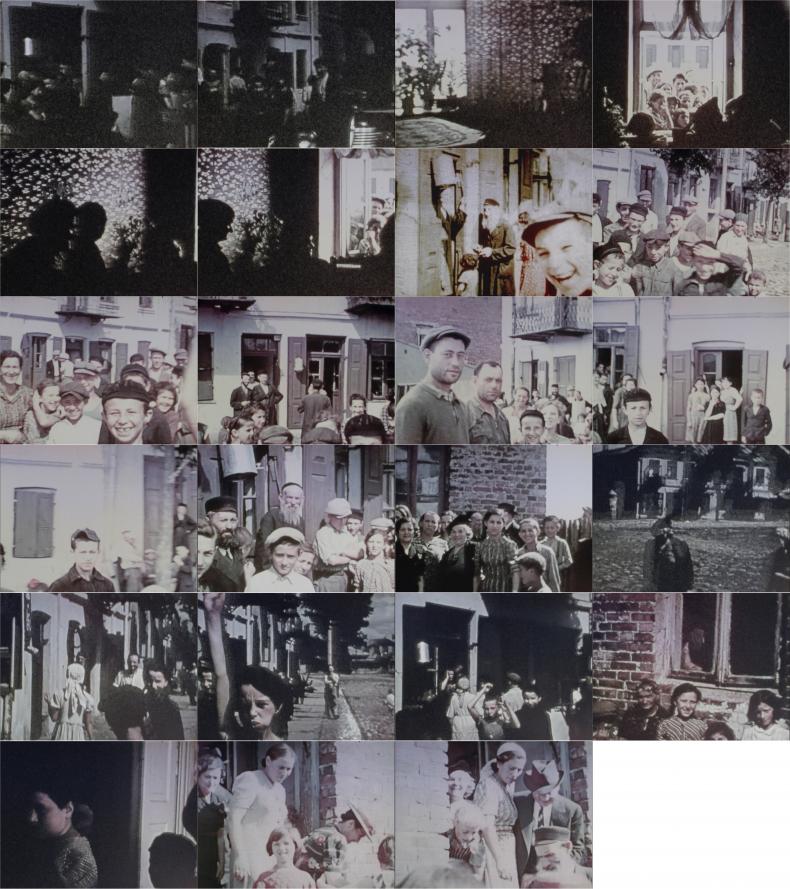

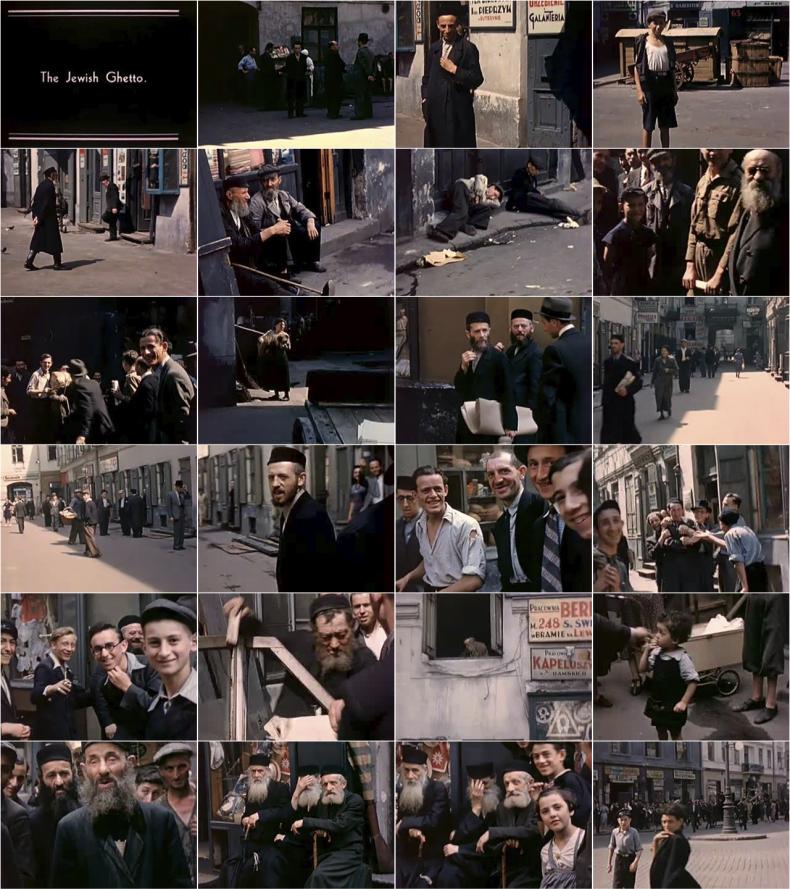

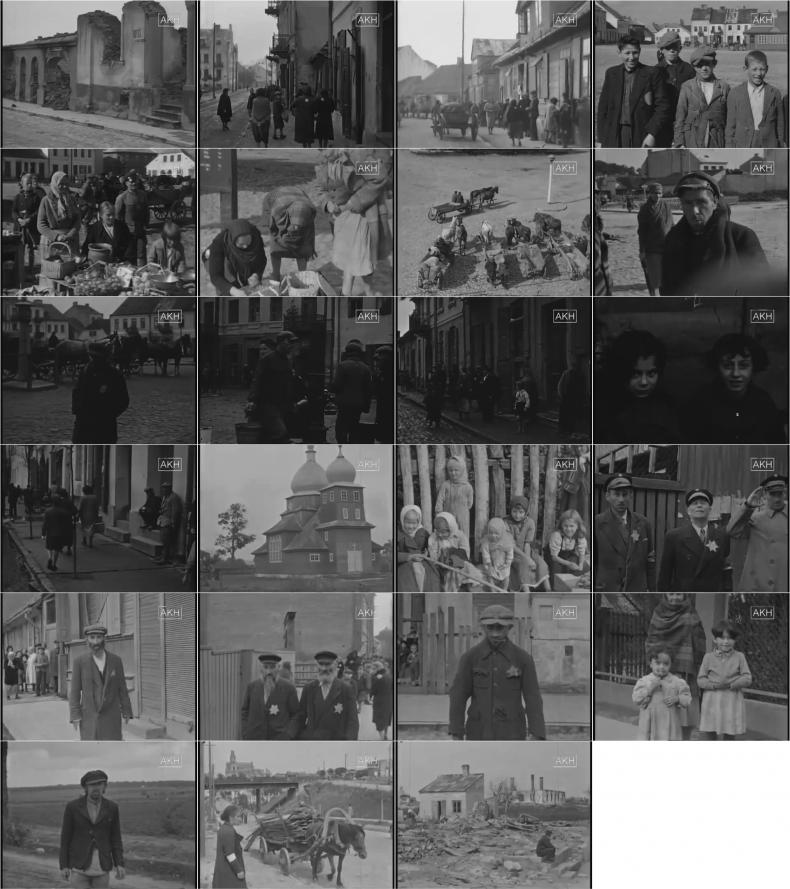

Being connected to this shift, the lesser-known part of this filmography may provide some unexpected features. Often the subjects filmed present themselves proudly, withstanding the mugshot attitude of their indoctrinated photographers, and engaging with the camera as one, if only very partial, “way out.” These films and photographs perhaps have the strongest potential to contradict the expectations of audiences today. They resist the still-dominant victimizing tendencies in Holocaust remembrances. As such, our approach goes beyond a sole rejection of the perpetrator’s gaze inscribed in these images. While Jamie Baron in her recent publication Reuse, Misuse, Abuse20 claims that the revealing of staged shots and the humane gaze that Yael Hersonski applies to the carefully selected “Judentypen” from the archival propaganda footage of the Warsaw Ghetto in her documentary A FILM UNFINISHED neutralizes the perpetrator’s gaze to a degree that justifies its use, we believe that exactly this use is problematic for two interconnected reasons: On the one hand, the distorted representation of the ghetto inhabitants as abnormal types conveys an anti-Semitic cliché of the Polish Jews. But even if we ignore this bias, the footage depicts these individuals as victims of an inevitable fate and therefore puts forward an interpretation of history that avoids agency, that imagines the Holocaust as a crime without perpetrators—the victimizing Holocaust remembrance. Archival footage such as GHETTO IN DABROWA GORNICZA AND BEDZIN (1942) on the other hand, is very rarely is shown in documentaries, most likely as its casual mood doesn’t make this kind of humane gaze look appropriate, while the footage actually fully represents the objectifying impact of the perpetrator’s gaze—but in order to comprehend and experience it, we need to accept the act of filming as part of the genocide.

A number of the materials listed here call for a closer scrutiny. While the better known footage, like the Liepaja film, as Ebbrecht-Hartmann (2016) demonstrates, underwent a development of its status from war trophy to court evidence to lasting document, a lot of the privately shot films from the ghettos still seem to come across like trophies, or at least like exciting by-catch in these amateur films, often shot by German soldiers when they were off-duty, while at a closer look they almost always betray the ideologically trained gaze and often seem to anticipate the atrocities to come. But it should also be noted that the content varies considerably. At least a handful of amateurs did not indulge in mugshots or humiliating perspectives. These few examples show that the perpetrator’s gaze wasn’t the only possible way to film or photograph, but a deliberate attitude the majority of photographers and amateur filmmakers chose to adopt.

While their sheer existence in our opinion sheds a new light on the level of commitment among the filmers and the filmed perpetrators appearing in some of them, these films also have substantial evidential value. They are proof of the perpetrator’s gaze and at least some of them provide evidence for the living and working conditions in the ghettos. Recently there has been a number of publications that examine the forensic value of films and photos from the genocide. The widely acknowledged publication of the newly surfaced collection of photographs by Johann Niemann Fotos aus Sobibor (2020) was introduced with the vague but impressive claim that the photos would show a young John Demjanjuk in Sobibor and therefore finally settle that he had been lying to the court. Also, in Die fotografische Inszenierung des Verbrechens21 Bruttman, Hördler, and Kreutzmüller analyse the photographs from Auschwitz in a detective-like manner, striving to explain every detail and to date them with the help of shadows down to the hour of day. A similar approach can be found in Fabian Schmidt’s recent essay about the Westerbork footage (2020), where he scrutinizes not only the provenance of the footage but also the alterations it most likely was subjected to by the archives preserving it. Our essay about the Atrocity Film (same title, 2021) also belongs to this new corpus of quasi-forensic approaches. This could be interpreted as traces of a shift in the historicization of the Holocaust. While well into the late 1990s the discourse in Germany was influenced by perpetrators and a comparably harmless event such as the so-called Wehrmachtsausstellung was capable of sparking a nationwide controversy about how much of the truth was allowed to be said, we seem to be entering a new phase, where eventually the fact of the genocide is widely acknowledged and where there is public interest in reconstructing the past. Perhaps these films and photos will eventually allow the public remembrances to engage in a less distorted look at the atrocities that were committed by the Germans in Eastern Europe, a view that today is still restricted to a relatively small number of Holocaust historians and film archivists. But we would like to dare an even bolder reading of forensic cinema. Scrutinizing and also simply watching these films will help us to relate to the past. The Allied liberation films that were mapping the camps shortly before they often had to be destroyed for reasons of hygiene, but also reconstructions and reenactments of the camps in feature films and in 3D models can be interpreted as attempts to contribute to a visual memory of the Holocaust that doesn’t necessarily rely on evidential photography but rather aims at a visualising and profoundly cinematic remembrance. We believe that the films in this filmography should play a role in this process of historicization.

While the narratives of the World War and the genocide have been mined territory for a long time, photographs and films today promise a new, direct way of connecting to the past that is less tinted with false claims of innocence and quarrels about who is allowed to judge and define the past. This, of course, is an expectation these images will not be able to live up to. The perpetrator’s gaze that is inscribed in many of these moving images, their often propagandistic tendencies and the availability of material today, which is limited by deliberate destruction at the end of the war as much as by prior selection of motives during the process of shooting, ensures that these films can hardly be drawn upon for representative or objective purposes. At best, they offer glimpses into facets of reality, and often very subjective glimpses at that. Finally, there is yet another motivation for scrutinising these images which is deeply rooted in our culture of remembrance: many of these images show human beings on the verge of being murdered. For Lili Jacob, who in 1945 found the “Auschwitz Album,” those photographs were a final memento of her neighbours and relatives.22 Acknowledging the evidential, the indexical aspect of these images is also an act of respect and a final moment of empowering the victims. No matter the outcome, as a first step one ought to acknowledge the existence of these films and pictures, and explore the paths to further scrutiny which they may offer.

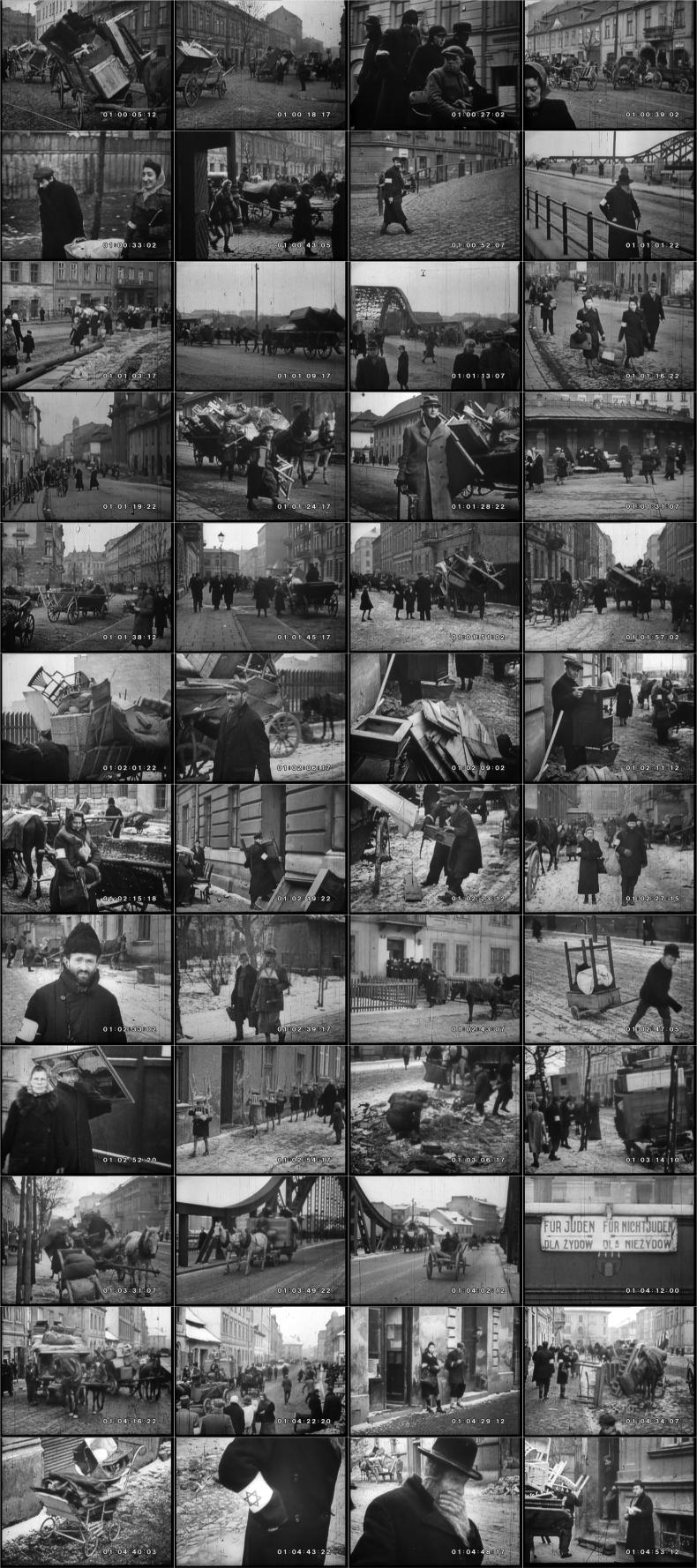

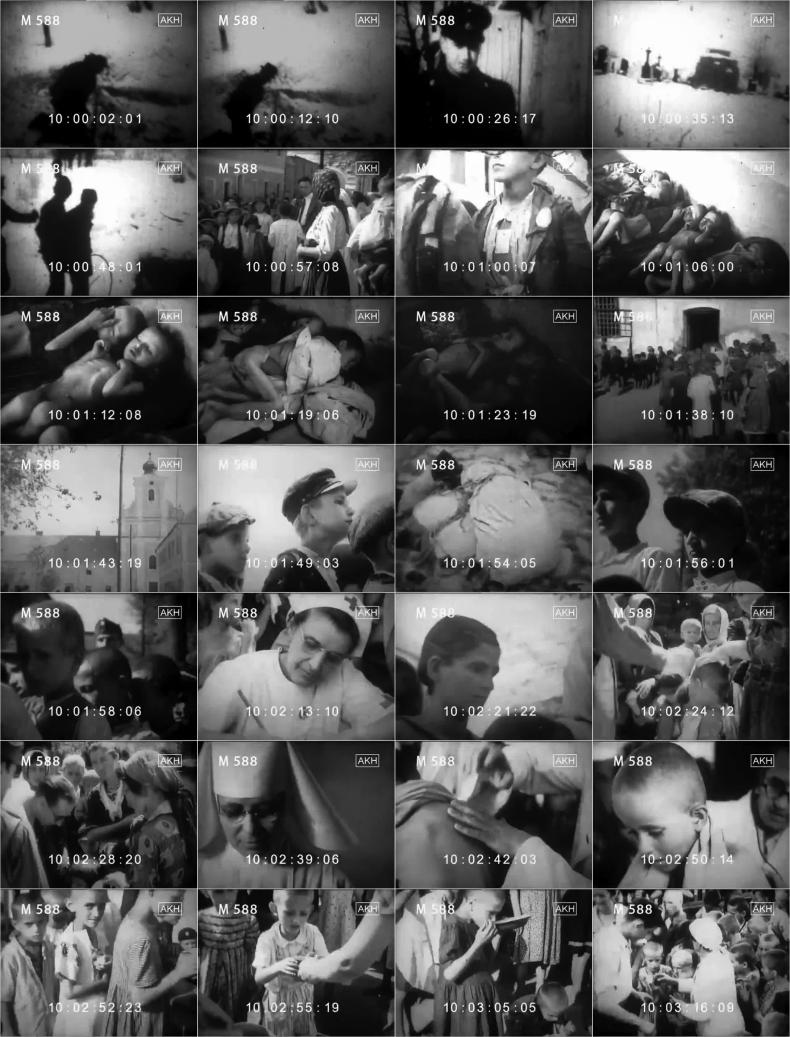

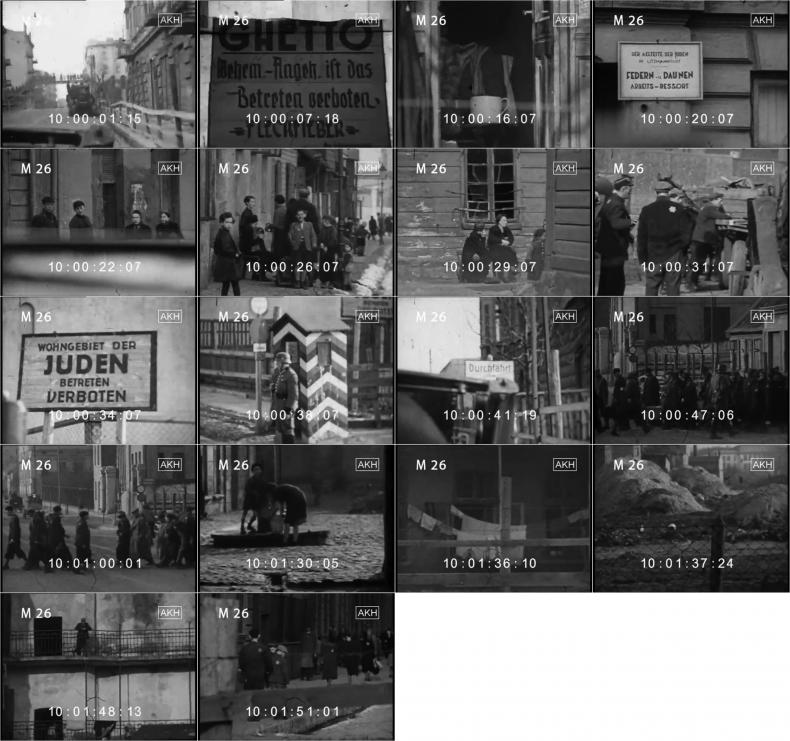

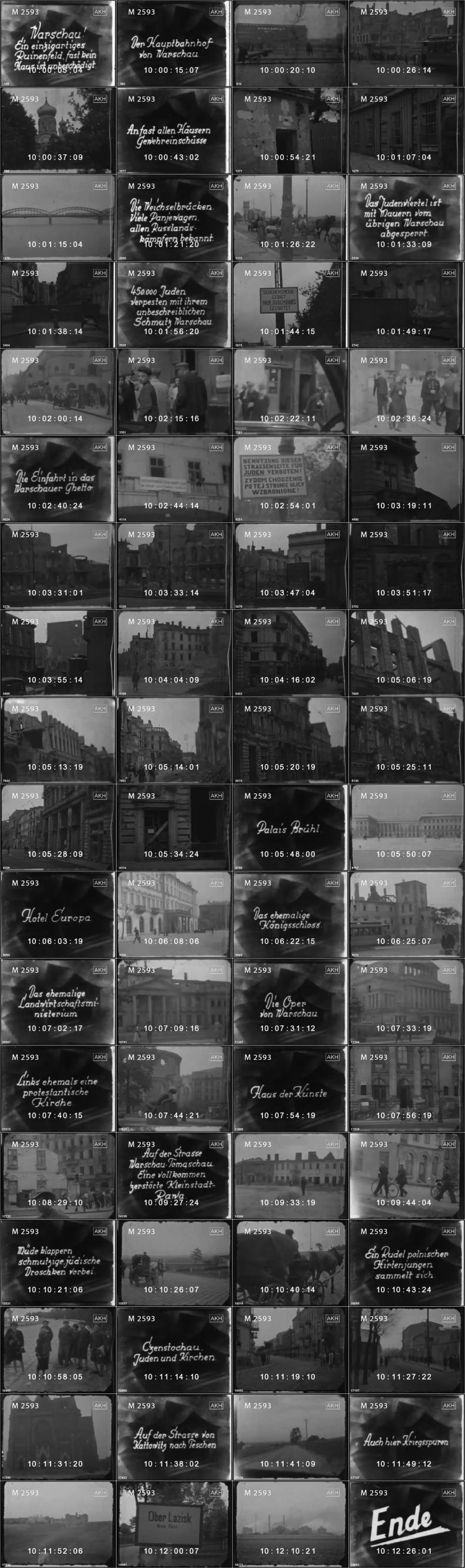

We are proposing this filmography as a preliminary effort to a comprehensive approach in researching and assessing these films. Compiling a list of titles, with data on their physical and intrinsic properties and where they are located today, will hopefully encourage historians and researchers to seek out these sources, especially lesser-known materials. We hope that the screenshots that will be added for many of these films will contribute to their increased visibility as sources, even though the next obvious step— a public repository which makes them accessible as moving images—remains a far-flung objective that is bound to encounter opposition from some of the rights holders. At its best, this filmography will serve as the nucleus for a collaborative approach, and will be amended and enhanced well into the future. Finally, we’d like to reinforce again that this filmography also constitutes an assemblage of evidence for the collective will to document a genocide—initially merely anticipated (as in the trophy films shot in the ghettos before their liquidation), though very quickly moving on to filming and photographing even acts of murder. While the greater share of these latter documents has been lost (and, we must assume, often deliberately destroyed), the existing footage defines not only the shape of this gap but serves to estimate its quality.

6. Methodological Notes

The volume of material documenting the genocide is as expansive as it is profoundly disturbing. The potential existence of an SS Film documenting the genocide remains hypothetical for the time being. The following filmography is supposed to give an overview over both existing and lost materials. So far, we have identified over 150 pre-1945 film materials which were produced during the different stages of the genocide, ranging from newsreels and propaganda films to unedited footage and a sprawling amount of amateur films. Of the latter, amateur footage from the ghettos forms the largest identifiable group.

In the filmography presented here, we compiled all references to footage that we could find: still-existing material, material used in the past but with no verifiable trace of the original elements in archives today, as well as footage only mentioned in wartime or postwar sources which hitherto has not been discovered. The latter group is bound to include films or film footage that was destroyed, either deliberately or as a result of the devastations of war, and which may never be found. We encourage readers to let us know about any further such materials, reports on film activities or even existing footage that is missing here. The corpus of literature on the Holocaust has long grown to a size that is hard to survey, let alone evaluate in full. As such, we rely on all historians and archival researchers to help us gather this information.

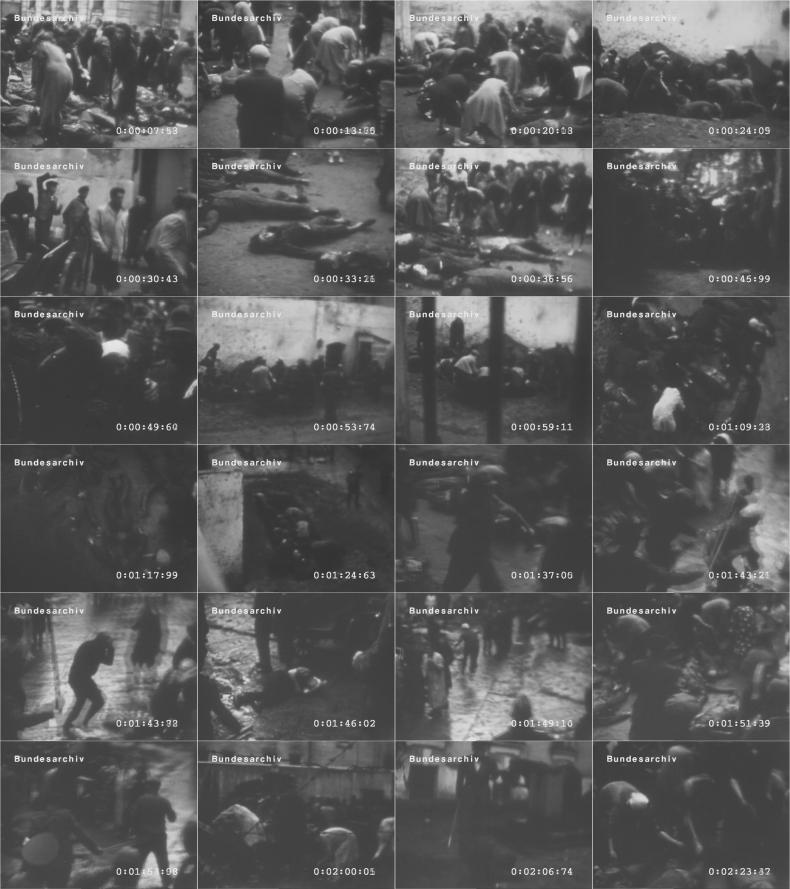

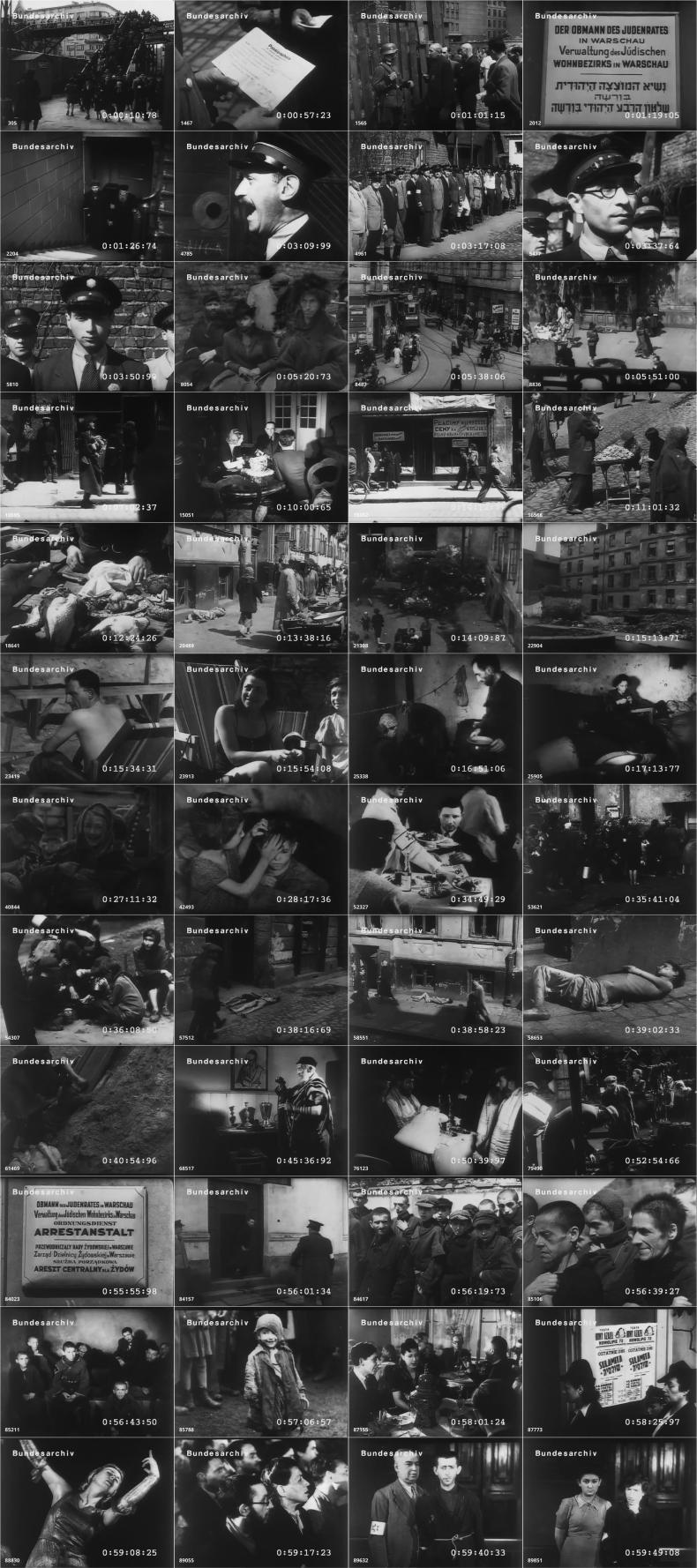

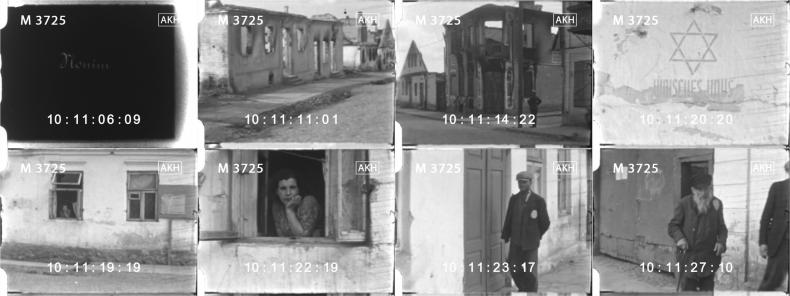

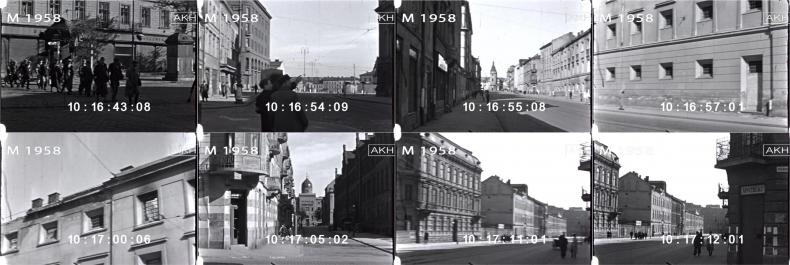

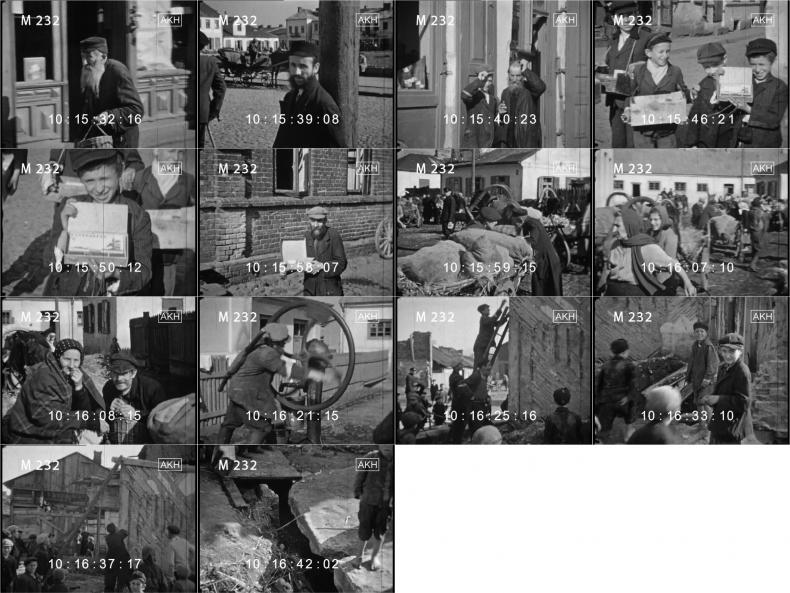

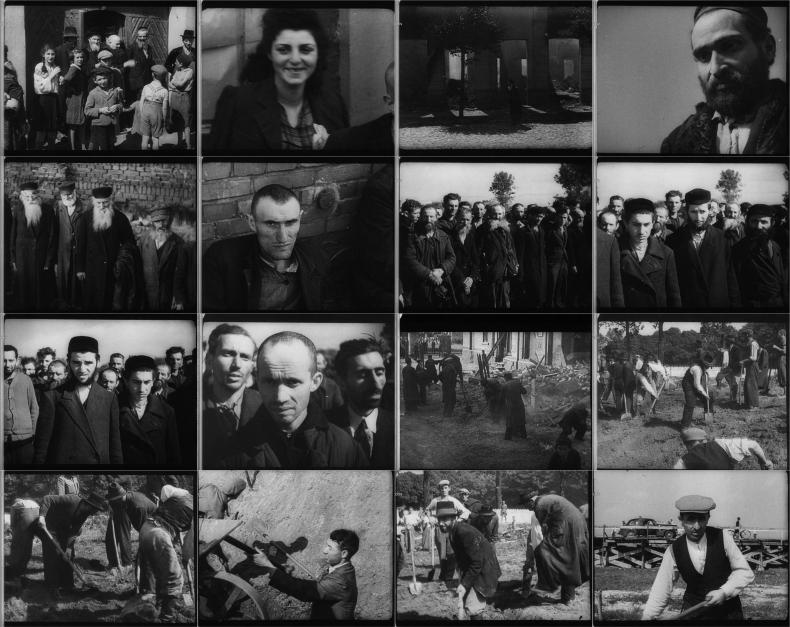

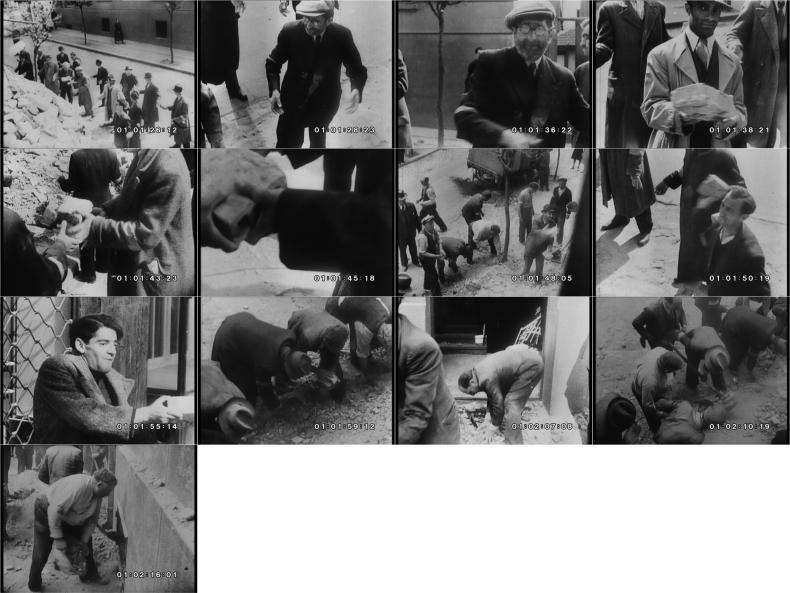

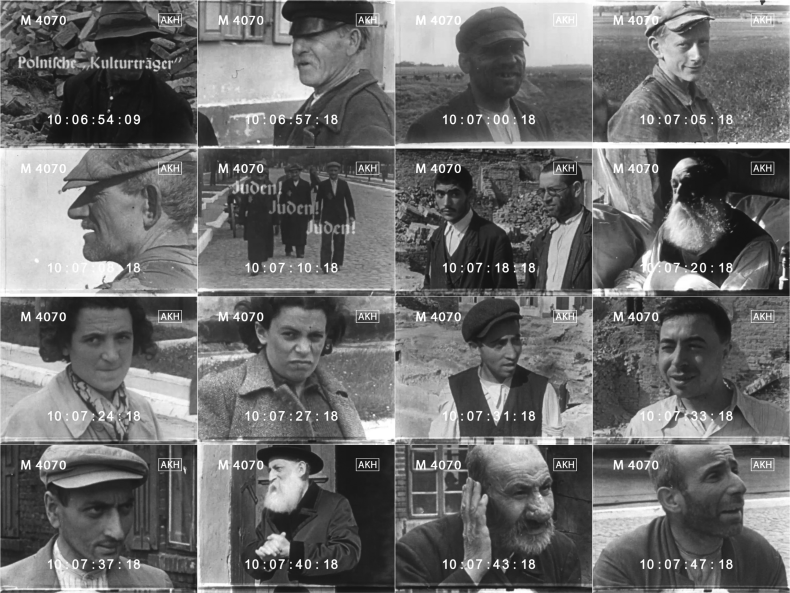

This filmography is still under construction, and will be completed over the course of the coming months and years. Our aim is to not only list all relevant materials, but to also provide screenshots of every new shot within the footage, each filed under a unique identifier consisting of an abbreviation for the film and a number for the frame count burnt into each screenshot so that future research is provided with an unambiguous reference for all these materials. So far we can only provide full documentation for some materials, such as the footage from Liepaja and Zichenau. In the coming months we hope to provide this information (open gate screenshots, frame count) for the entire filmography. We also aim to indicate surviving camera originals and contemporary pre-1945 elements, where possible, to highlight the existing physical record as it survives in film archives today.

In attempting to catalogue and classify what is essentially a highly diverse collection of films, we group them as follows:

Newsreels: any newsreel or comparable series of news films released for public screening.

Films: documentary features and shorts produced for public screening, including restricted screenings of films produced for limited audiences, such as trade professionals. In the case of films produced in Nazi Germany this mainly covers films that were cleared by the film censors (Filmprüfstelle). Perhaps unsurprisingly, the majority of these films are propagandistic in nature.

Footage: unedited footage, unfinished films etc. produced by statal organisations of Nazi Germany, including raw newsreel material.

Amateur films: any films shot and produced by amateur cameramen and filmmakers, including raw footage in case no statal background exists.

UPPERCASE TITLES refer to completed films that were assigned an officially-recognised title at the time, typically by the production company or author, with a view to being distributed and shown to audiences.

TITLES with an appended (A) refer to films or footage from an archival source, with the title having been assigned by the archive. In case of certain widely circulated materials that have been assigned different titles by different institutions, we give the most common identifiers.

[TITLES] in square brackets refer to films or footage to which no established title has yet been assigned. This typically applies to archival material that hasn’t been widely used in postwar documentaries and history television, or which has not survived in the first place. We also use this notation for important historical footage which only survives as fragments spliced into postwar documentaries.

Abbreviations: AKH – Archiv Karl Höffkes, Gescher; BA – Bundesarchiv-Filmarchiv, Berlin; GFF – Gosfilmofond of Russia, Belye Stolby; NARA – National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD; USHMM – United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington D.C.; YV – Yad Vashem, Jerusalem.

Since many of these films are silent, we only indicate sound where present.

7. Filmography

A: pre-1945 documentary film materials

Newsreels

For newsreels, we aim to provide details on the respective news item of relevance to this filmography, and give both the length of the entire newsreel and the segment in question in metres.

- 1933

-

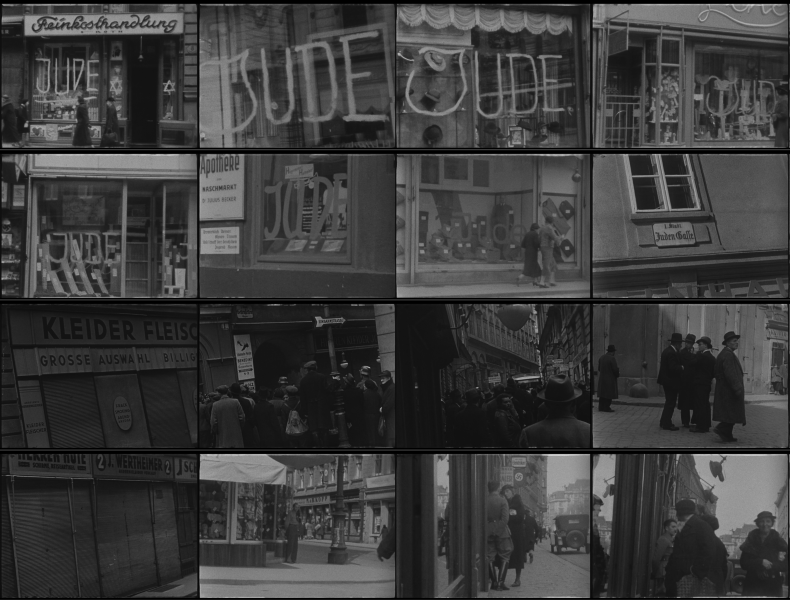

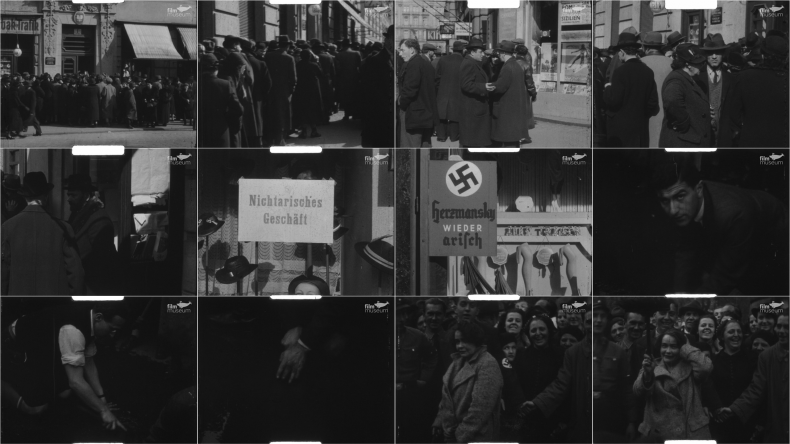

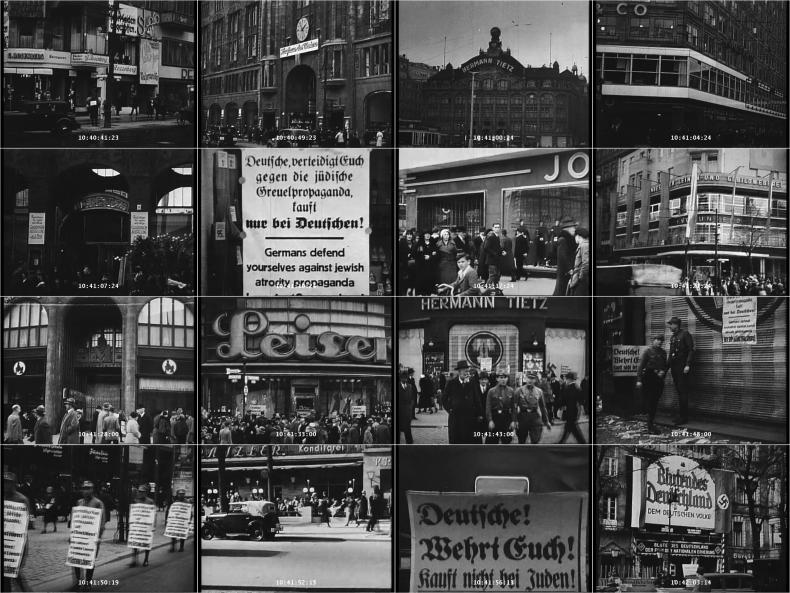

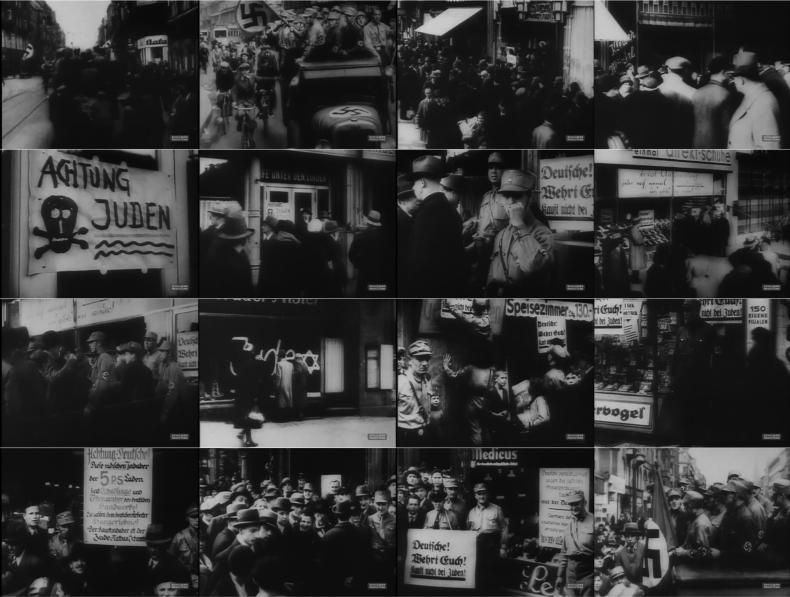

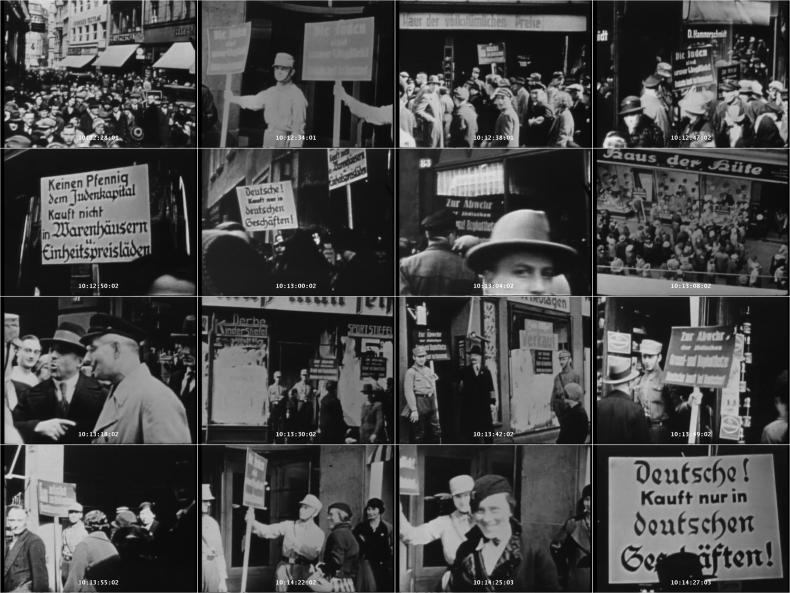

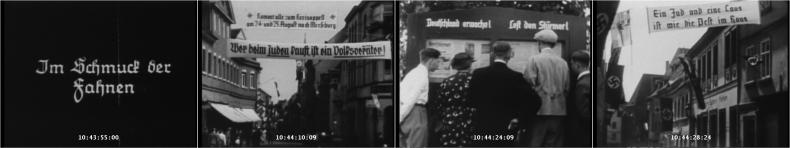

DEULIG TONWOCHE 66/1933 (5.4.1933). 35mm, b/w., sound, 12 min., official Boycott of Jewish shops. USHMM, RG Number: RG-60.4020, Film ID: 2705. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1003426.

DEULIG TONWOCHE 66/1933 FOX TÖNENDE WOCHENSCHAU JG. VII, Nr. 15/1933. 35mm, b/w., sound, 11 min., (6.4.1933). USHMM: RG Number: RG-60.0240, Film ID: 200. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1000173. (Note: the provenance is not clear).

FOX TÖNENDE WOCHENSCHAU JG. VII, Nr. 15/1933 - 1939

-

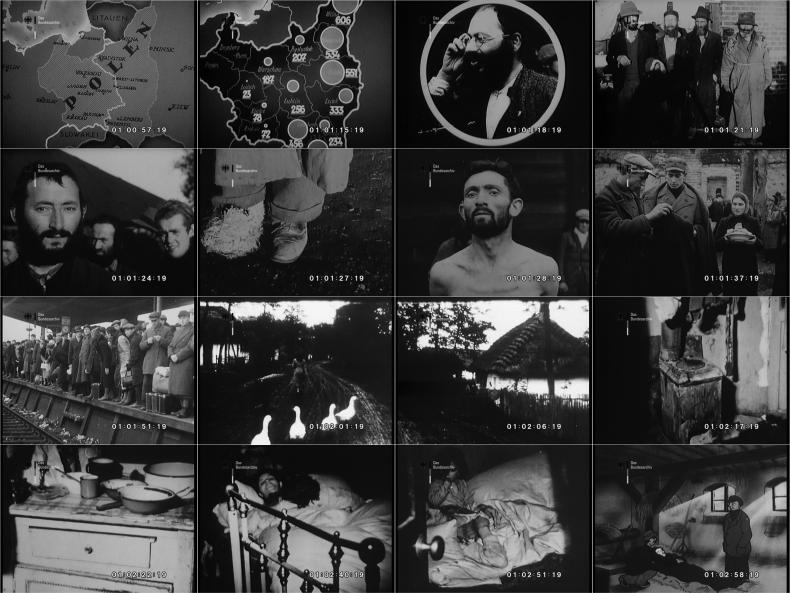

UFA-TONWOCHE 439/1939. PR: Universum-Film AG, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, sound. ? min. Contains snippet of Hitler's speech in front of the Reichstag threatening annihilation ("Ausrottung") of the "Jewish race in Europe". The same speech is included in the TOBIS-WOCHENSCHAU 6/1939, DEULIG-TONWOCHE 370/1939, and in DER EWIGE JUDE.

UFA-TONWOCHE 471/1939. PR: Universum-Film AG, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 506 m. 18 (1) min. Contains: Polish Jews under armed guard being marched on a road and made to stand in front of a wall; Jews standing on the platform of an open lorry before being transported away; camera pan across the faces of bearded Jews. Voice-over: "Polish Jews, many of whom are guilty of inciting murder against Germans. From their circles were recruited those grafters and criminals, who after 1918 flooded the defenseless Germany and of which the names Barmat and Kutisker are still remembered. Today the brothers and sons of these eastern Jews ["Ostjuden"] are sitting in England and Frankreich, agitating for a war of annihilation against Germany." 16 m. The same segment is included in TOBIS-WOCHENSCHAU 38/1939.

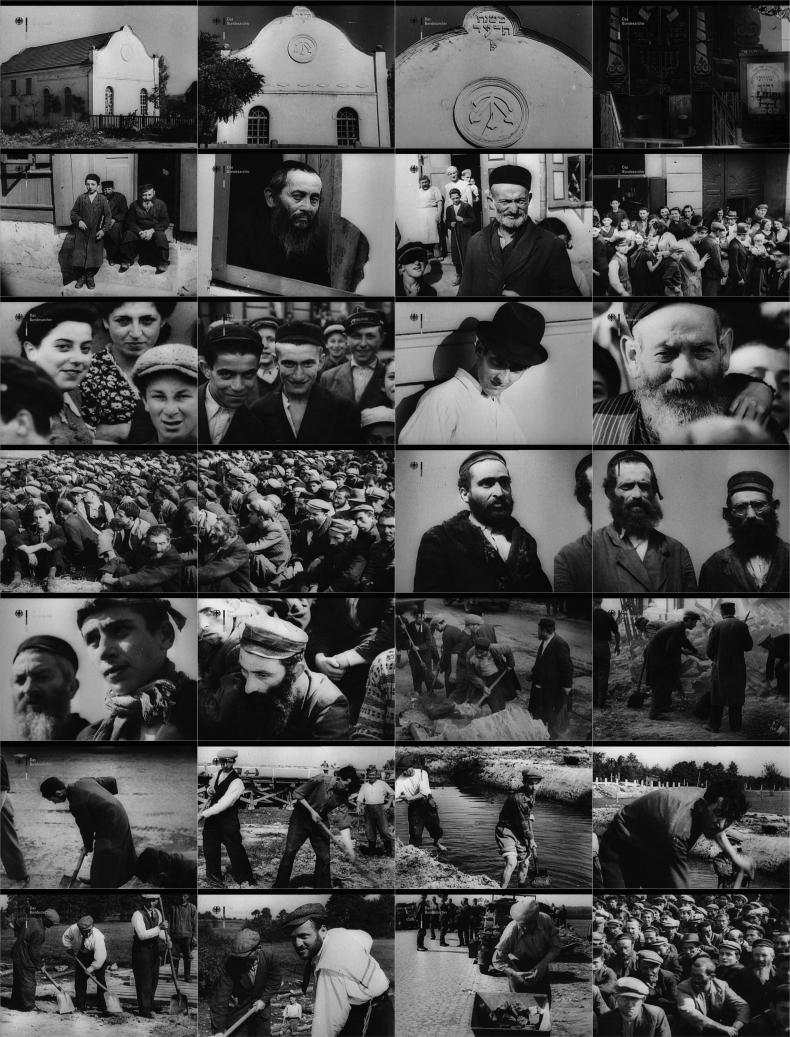

UFA-TONWOCHE 471/1939 UFA-TONWOCHE 472/1939. PR: Universum-Film AG, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 671 m. 24 min. Contains: Synagogue in a Polish town occupied by German troops (ext. and int. shots); Jews sitting on the stairs of an entrance door, another is looking out of a window; Poles and Jews in a camp, sitting on the floor (camera pan); Jewish faces (close-ups); Jews clearing rubble, excavating a water trench and performing road construction. Voice-over: "Most of them find their houses in ruins. In this village but a single building wasn't torched by the arsonists: the synagogue. No comment is needed. In the ghettos of the occupied towns the Jews are in high spirits. These pictures forcefully contradict the Jewish atrocity propaganda in the enemy countries. Insubordinate elements are being concentrated in camps. For the first time in their life they are forced to work." 55 m. The same segment is included in TOBIS-WOCHENSCHAU 39/1939.

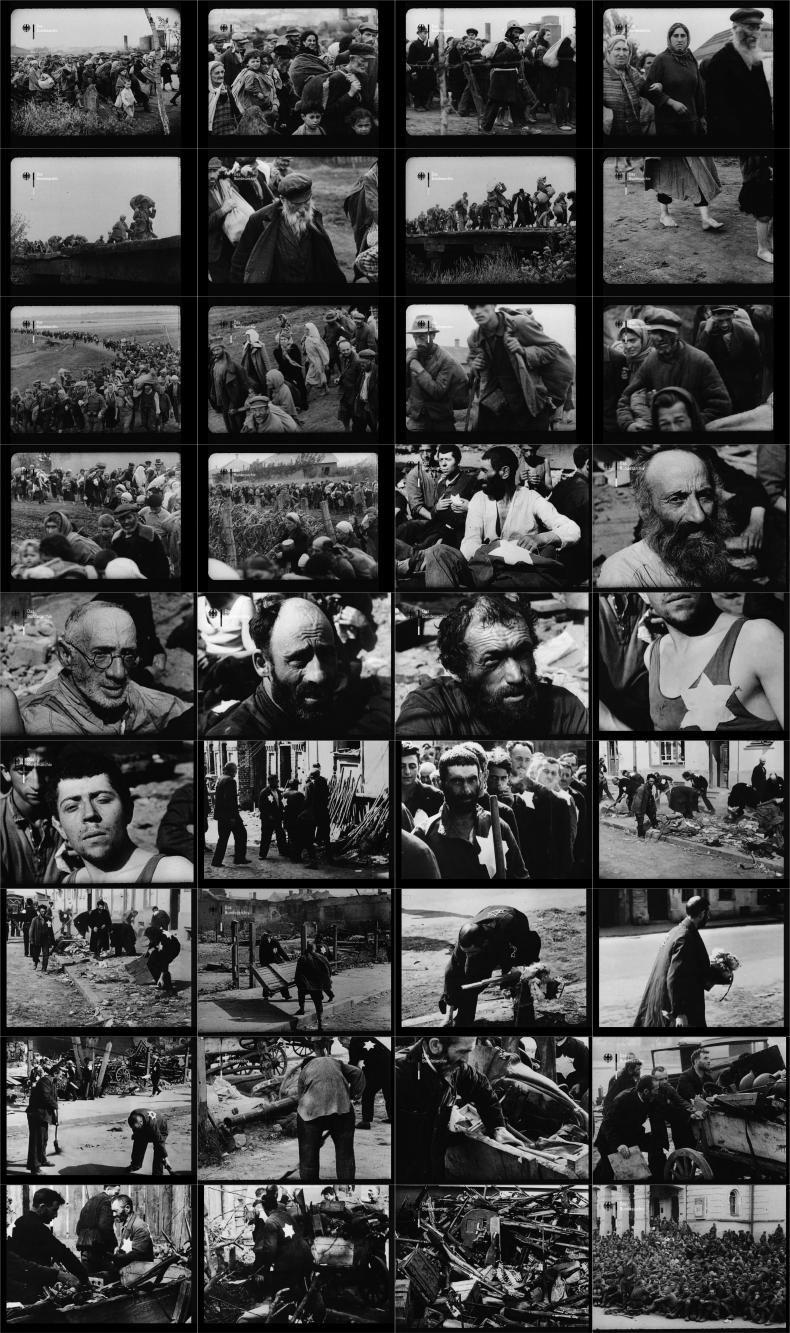

UFA-TONWOCHE 472/1939 UFA-TONWOCHE 474/1939. PR: Universum-Film AG, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 497 m. 18 min. Contains: Jews in the bustling streets of a Polish ghetto; faces of bearded Jewish men (close-up); camera pan across groups of individuals. Jews clearing rubble and during road construction. Voice-over: "The greatest problem facing the civil administration in the occupied territories is the Jewish question. German soldiers were shot at from these ghetto shacks. Punishment is swiftly meted out. These eastern Jewish subhumans ["ostjüdisches Untermenschentum"] have always supplied western Europe with its international criminal riff-raff. From here democracies were provided with pickpockets, pimps, drug dealers and human traffickers, international banking profiteers and hate journalists. These are the self-same Jews whose brothers, sons and cousins do all the talking for humanity and civilisation in London and Paris. Only if they are properly forced to work they suddenly become very docile." 38 m. The same segment is included in TOBIS-WOCHENSCHAU 41/1939.

UFA-TONWOCHE 474/1939 UFA-TONWOCHE 476/1939. PR: Universum-Film AG, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 478 m. 17 min. Contains: Jews clearing rubble in Warsaw; excavation of a pit by Polish prisoners of war. Voice-over: "In Warsaw a maddened governmental and military clique incited the civilian population to resist, believing to be under British protection. The irresponsible city commandant thought he could stall the well-equipped German units with barricades and toppled trams. His absurd resolve is to blame for the rubble covering the streets of Warsaw today. Jews are made to participate in the clean-up. They are not afforded any chance to exploit the suffering of others through racketeering or profiteering." 7 m.

UFA-TONWOCHE 476/1939 - 1940

-

SPRAWOZDANIE FILMOWE NO. 2 Z GENERALNEGO GUBERNATORSTWA W POLSCE. PR: Film- und Propagandamittel-Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH, Krakow – Warsaw. Contains: Jews are used as load carriers on the paddle steamer "Stefan Batory" on the Vistula, dragging sacks, boxes and pieces of luggage from the ship. 18 m. <1 min.

- 1941

-

ACTUALITÉS MONDIALES NR. 66 VOM 23.10.1941 (A: BA). PR: Deutsche Wochenschau GmbH, Berlin / ACE, Paris. 35 mm, b/w, silent, 179 m. 6 min. Contains: aftermath of a bomb attack against a synagogue in Paris (29 m). Note: On the night of October 2-3, 1941, members of the fascist Parti populaire français (PPF) committed several bomb attacks, destroying six out of the seven synagogues in Paris. The attacks were carried out on the initiative of the German SD, who always supplied the necessary explosives.

ACTUALITÉS MONDIALES 59/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 538/1/1941. 35 mm, b/w, sound, ? m. 1 min.

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 538/1/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 558/21/1941. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 607 m (? min). Contains: Belgrade: Jews removing debris in the partly-destroyed old fortress of Belgrade; men with provisional armbands carrying bricks. Voice-over: "The Jews of Belgrade are being used to perform clean-up work in the destroyed fortress." 26 m. 22 (1) min.

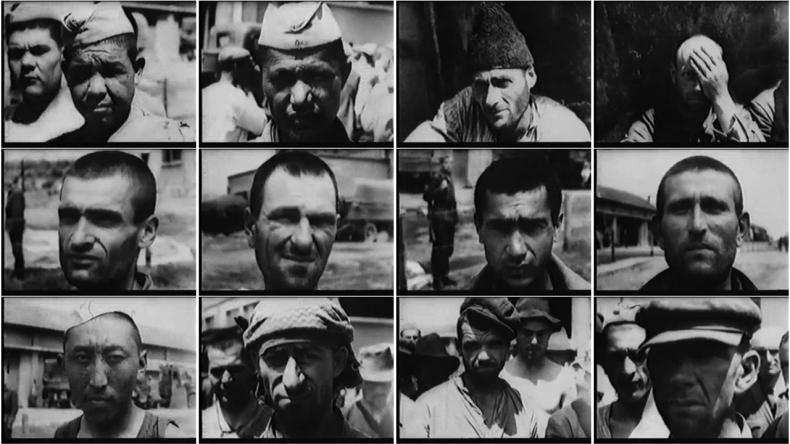

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 558/21/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 559/22/1941 (21.5.1941). 35 mm, b/w, sound, 583 m. 21 min. Contains: Greece: POW camp; camera pans across POWs; individual prisoners (CU), including Indians, Arabs, and New Zealanders; a group of Serbian officers; group of Jewish prisoners with German guards; individual faces (CU). Voice-over: "A camp with 10,000 prisoners. (...) Officers of dispersed Serbian units who were captured in Greece, and Jewish émigrés as voluntary auxiliaries of the British."

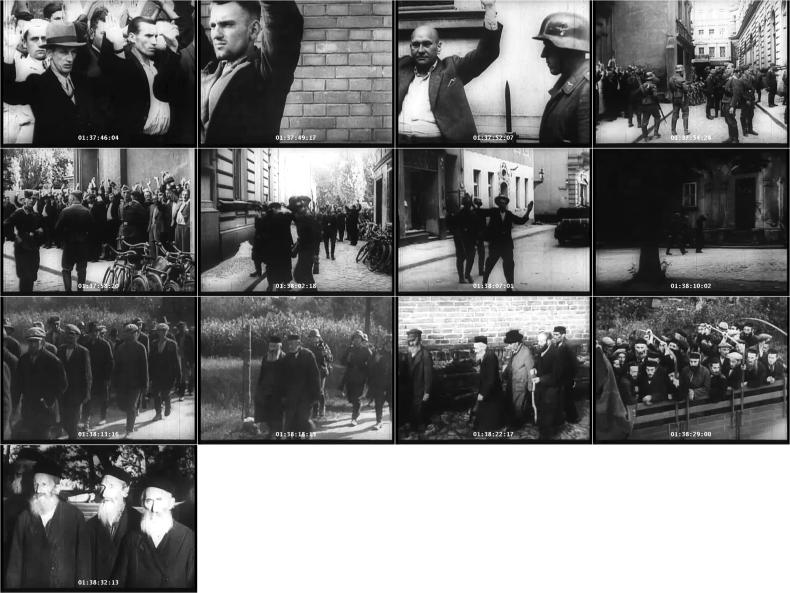

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 559/22/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 566/29/1941 (19.7.1941). 35 mm, b/w, sound, 934 m. 34 min. Contains: 1. Pogrom of Jews by Ukrainian nationalists in Lviv after the capture of the city by the German 1st Mountain Division on June 30, 1941; Jewish NKVD agents (as claimed by the German voice-over) are being turned over to German forces (14 m). 2. Jonava/Lithuania. The partly destroyed city; synagogue (EXT and INT shots); Luftwaffe soldiers pulling Jewish inhabitants from their homes to be taken away; CU shots of arrested Jews. Voice-over: "Jonava is in German hands. Scenes of destruction. Everything that was spared during the fighting was destroyed by the Soviet hordes during their retreat. Only the synagogue remained entirely intact due to orders given by the Jewish commissars of the GPU. The Jewish quarter of Jonava, which was equally spared, is being cleansed. Here, too, the Jewish rabble, in cahoots with GPU agents, terrorised the Lithuanian. Jewish ghetto types, scum of the earth." (18 m).

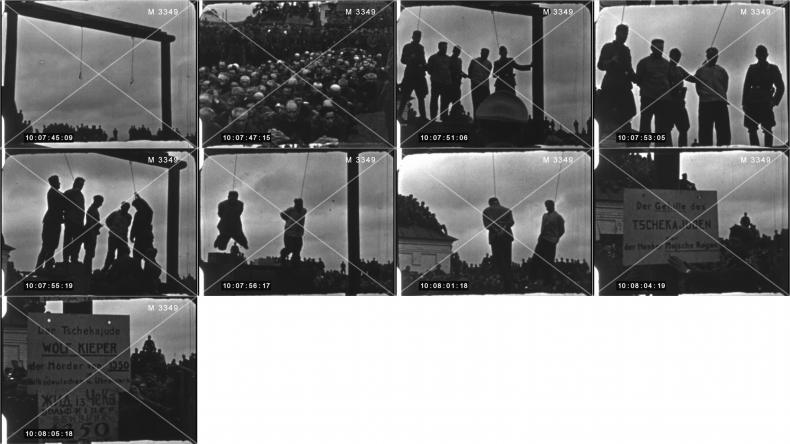

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 566/29/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 566/29/1941 (Jonava) DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 567/30/1941. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 1053 m. 38 (<1) min. Contains: 1. Jews with spades are made to jump from a truck; under SD guard they dig a pit at the edge of a forest, being constantly driven with loud shouts; some take off their shirts and continue working with bare torso. Voice-over: "The lazy Jews are immediately used to perform clean-up work" (14 m). 2. Pogrom in Riga: Latvian nationalists in civilian attire brutalising Jews in the streets; Wehrmacht soldiers as spectators; the burning synagogue of Riga at night. Voice-over: "The wrath and outrage of the populace against the cowardly, mostly Jewish murderers knows no bounds. Here the culprits for the nameless suffering of innumerable people are being caught by the irate relatives and handed over for just punishment. The synagogue of Riga, spared by the GPU commissars during their work of destruction like everywhere else, was set ablaze but a few hours later." For discussion of the first segment, which possibly shows the immediate steps leading up to a mass execution, see Schmidt/Zöller (2021).

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 567/30/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 567/30/1941 (Synagoge) DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 567/30/1941 (Digging) DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 568/31/1941. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 1022 m (? m). 37 min. Contains: 1. Lviv/Lemberg: Jews forced to exhume corpses of NKVD prisoners; the excavated dead are placed in a meadow one by one (20 m). 2. Provisional POW holding cage near Minsk; Soviet prisoners; faces of individual prisoners (CU), some of them possibly Jews (47 m).

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 568/31/1941 (exhuming) DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 568/31/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 569/32/1941. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 892 m. 32 min. Aerial views of Dorpat; Ruins of churches and buildings in the city; bodies lying in a courtyard; naked male corpses lying side by side. 22 m.

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 569/32/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 570/33/1941 (6.8.1941). 35 mm, b/w, sound, 970 m. 35 min. Contains: 1. Deportation of the Jews of Balti: huge procession of poorly dressed Jews on a rural road; they carry their few possessions and children with them, some are barefoot ( 20 m). 2. Smolesk after being occupied by German troops; Jews attaching yellow stars to their jackets; Jewish performing clean-up work in the streets of Smolensk; Jewish with large yellow stars affixed to the front and back of their clothes; collecting of garbage and sweeping of the streets; abandoned Soviet weapons are being collected (28 m). Voice-over: "A selection of Jewish types [Judentypen]. Finally they are being made to work. As can be seen - an unusual occupation for them. Here they must clean up the roads of the Soviet retreat" (28 m).

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 570/33/1941

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 571/34/1941 (13.8.1941). 35 mm, b/w, sound, 323 m.

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 571/34/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 579/42/1941 (8.10.1941). 35 mm, b/w, sound, 888 m. 32 min. Kiev after being occupied by troops of the German 6th Army on September 19, 1941; soldiers carrying boxes of explosives out of the Lenin Museum; the boxes are opened and the dynamite packages examined. Camera panning over the faces of Soviet prisoners, partly in uniform and partly in civilian clothes; individual faces with Jewish appearance (close-ups). Original German voice-over: Here is a selection of cheap tools used by GPU commissioners. They are partly responsible for these explosives attacks. Most of these cowardly beasts are Jews, each of whom has countless murders on his conscience." 27 m.

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 579/42/1941 DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 585/48/1941. 35 mm, b/w, 790 m. 28 (1) min. Contains: Column of Soviet prisoners of war crossing a makeshift bridge over the Dnepr; weary individuals in ragged clothing, partly in civilian clothes; POW column on a dirt road; aerial view from a Fieseler Storc; faces of individual prisoners (close-ups); group of Jewish prisoners in ragged clothing, sitting on the ground; single prisoners with shabby headgear (close-up). Voice-over: "The march of prisoners from the giant destruction battles east of the Dnepr seems endless. A special selection of Jews. The endless treck of captured Bolsheviks extends ever further west below. These are the allies of Churchill, Roosevelt's Christian soldiers." 25 m.

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 585/48/1941 SPRAWOZDANIE FILMOWE Z GENERALNEGO GUBERNATORSTWA No. 8. PR: Film- und Propagandamittel-Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH, Krakau/Warschau (FIP). 35 mm, b/w, 314 m. 11 min. Contains: German police patrol in Krakau; the patrol inspects a Jewish shop; one of the policemen discovers sausages and eggs from under the counter while the other reads out a proclamation to the Jewish shopkeepers (63 m). BA only has a silent print, BSP 16207.

- 1942

-

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 610/21/1942. 35 mm, b/w, 865 m. 31 min. Partisan warfare in the Jaila mountains in Crimea; Waffen-SS unit scouring a forested area; combat against a partisan base with small arms and grenades; partisans (in civilian clothes) surrender and are taken away. German voice-over: "Fight against Soviet gangs in the Jaila Mountains at 1200 metres. Clearing squads comb a forest area. Red Army personnel in civilian attire, Jews and Bolshevik agents, who terrorise the population at night through insidious raids and acts of sabotage, have set up their hiding places in these unclear and difficult to access areas. The gang is surrounded. Only a hard, ruthless grip can help here. The nest has been excavated, the rest of the bandits captured. This rabble can expect no mercy." 32 m.

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 610/21/1942 - 1944

-

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 718/25/1944 (7.6.1944). 35 mm, b/w, sound, 224 m. Contains an anti-Semitic story using footage from foreign sources.

DIE DEUTSCHE WOCHENSCHAU 718/25/1944

Films

- 1936

-

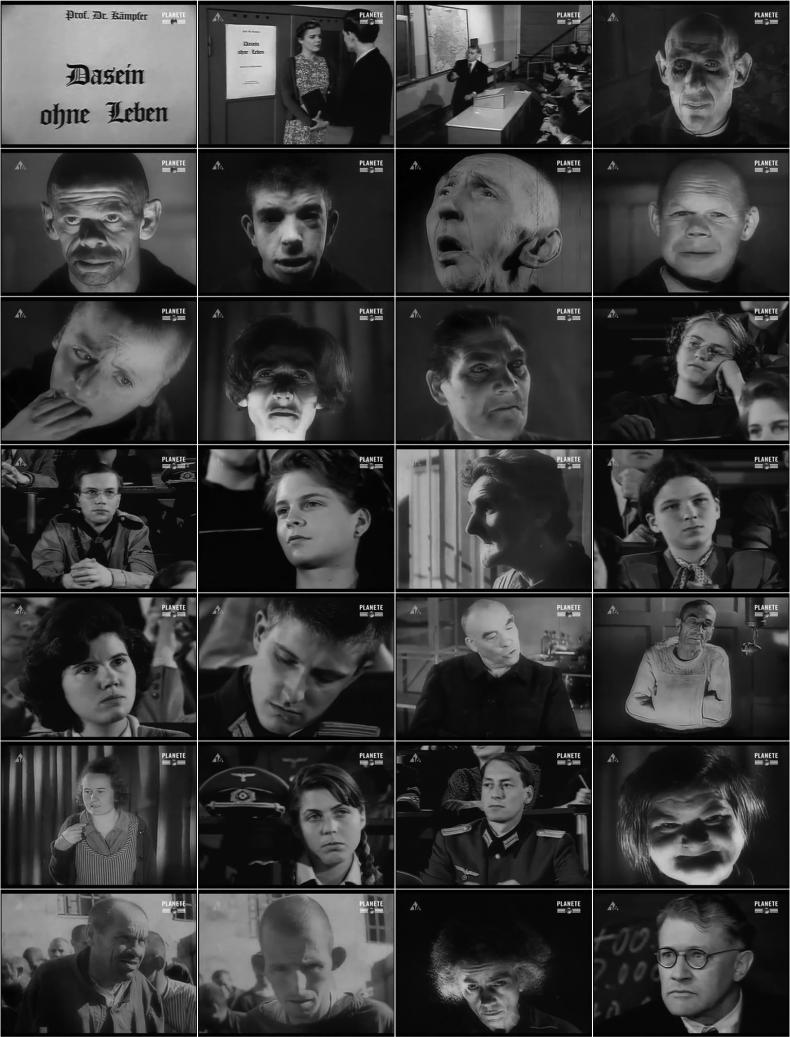

ERBKRANK. 35mm, b/w, sound. 11 min. One of six propagandistic movies produced by the “NSDAP, Reichsleitung, Rassenpolitisches Amt” or the Office of Racial Policy, from 1935 to 1937 to demonize people in Germany diagnosed with mental illness and mental retardation in order to gain public support for the T-4 Euthanasia Program then in preparation. It already features the mugshot style of later amateur and propaganda films. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1002454 Erbkrank

ERBKRANK - 1937

-

OPFER DER VERGANGENHEIT (Gernot Bock-Stieber). PR: Kultura-Film / Reichspropagandaleitung der NSDAP, Abteilung Film, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 413 m. 24 min. BA M 46. Propaganda film advocating for the sterilisation of individuals with hereditary diseases. Contains: mentally ill Jewish women in the convalescent and nursing home Berlin-Buch, who are contrasted with young, blonde nurses. Voice-over: “The Jewish people provide a particularly high percentage of the mentally ill. Their accommodation and subsistence, too, is being taken care of. For them, too, healthy German citizens must work, feed them, keep them dry.”

- 1938

-

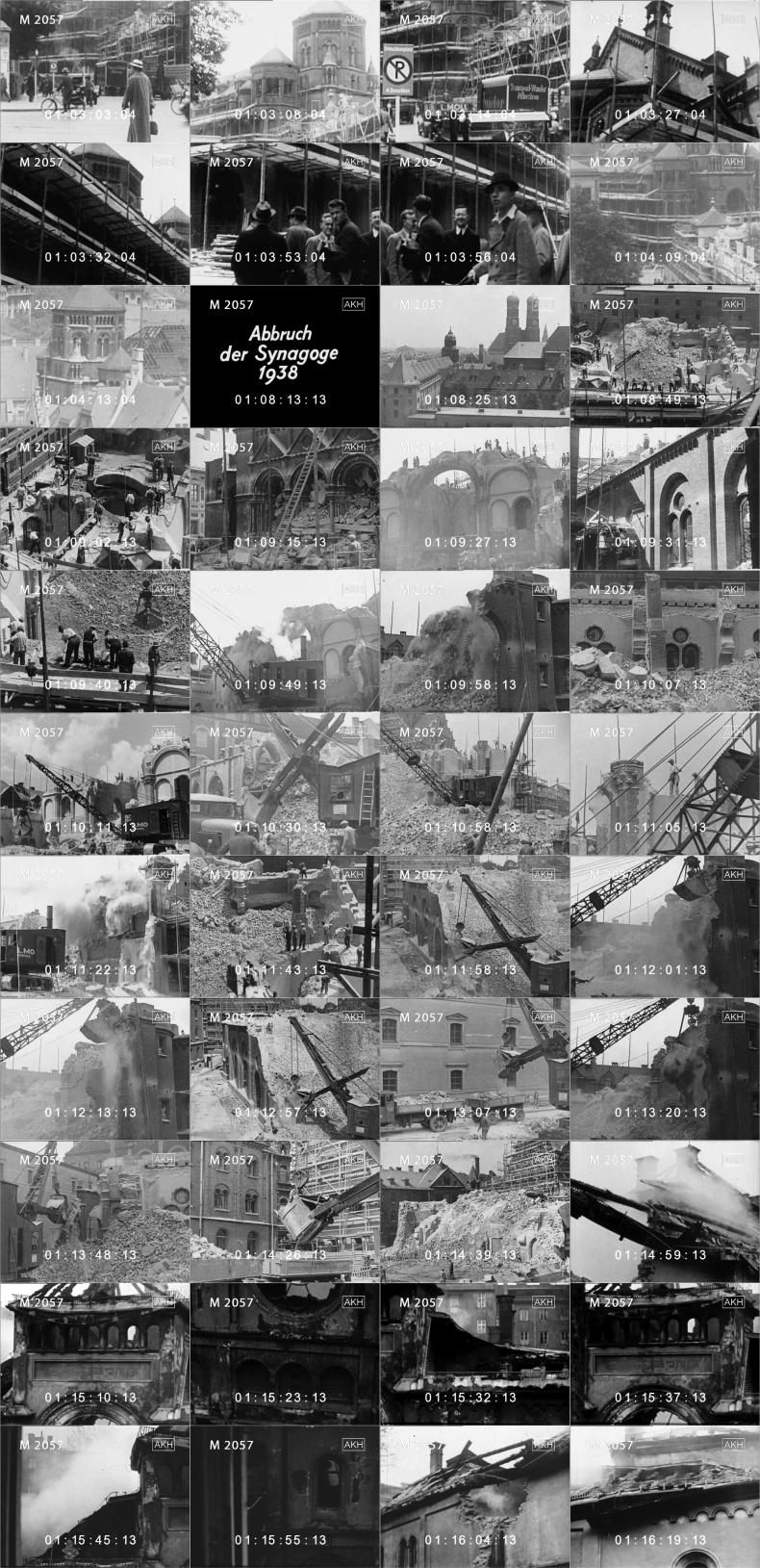

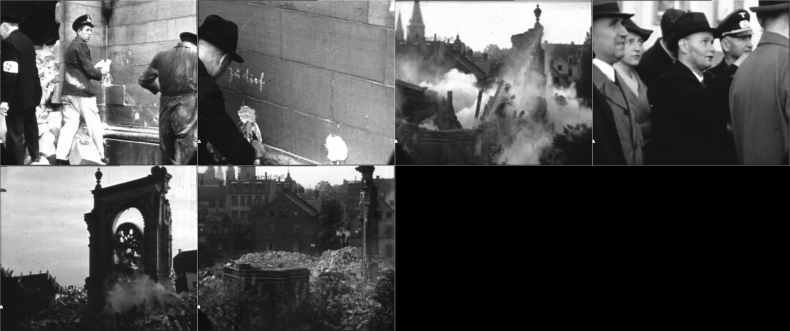

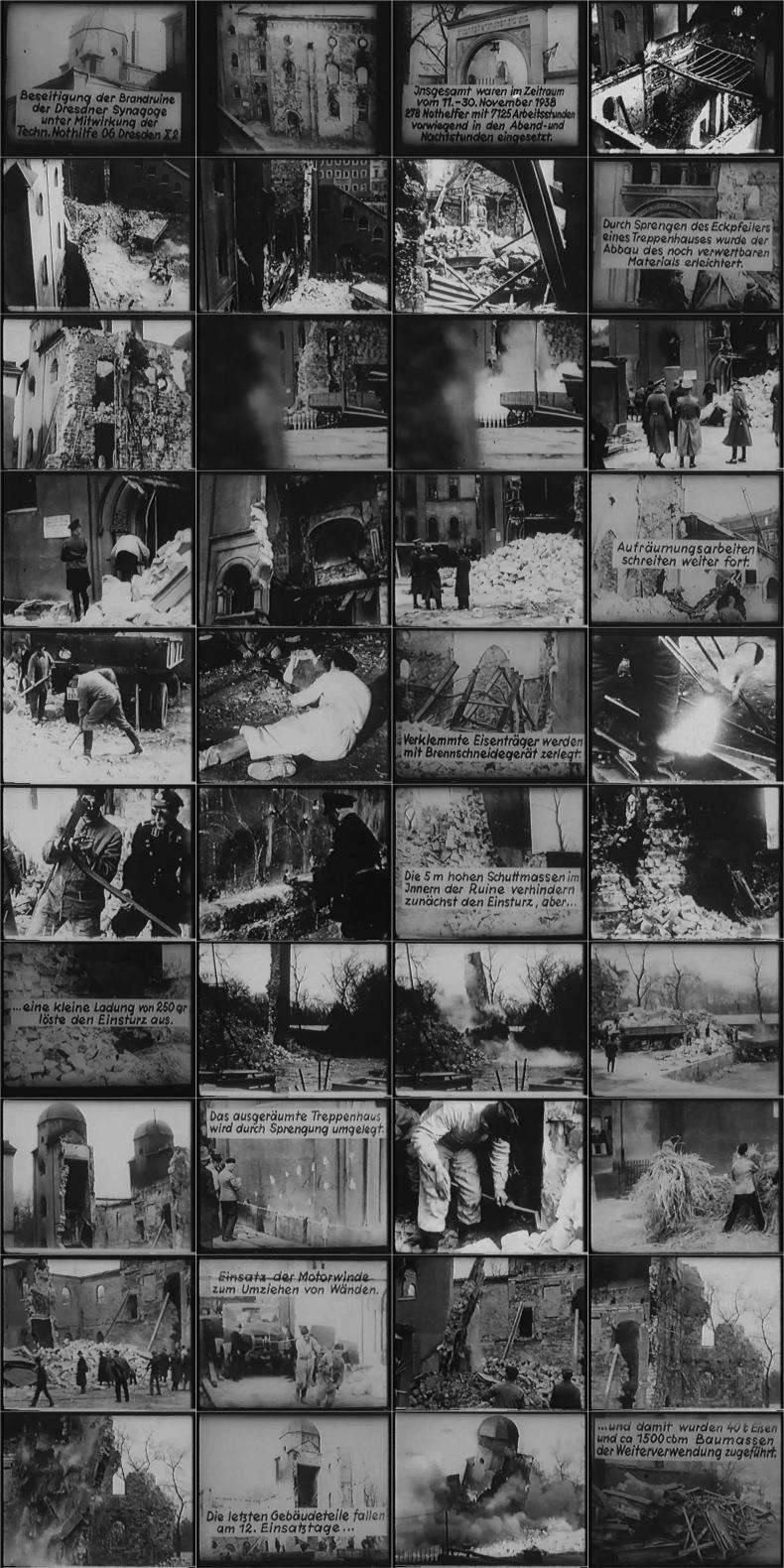

BESEITIGUNG DER BRANDRUINE DER DRESDNER SYNAGOGE UNTER MITWIRKUNG DER TECHN. NOTHILFE OG. DRESDEN X.2. PR: Technische Nothilfe, Dresden. 16 mm, b/w, 112 m. 13 min. Removal of the rubble of the burnt-out synagoge in Dresden by the Technische Nothilfe (Technical Emergency Help). Film with intertitles. BA M 20196.

Beseitigung der Brandruine der Dresdner Synagoge JUDEN OHNE MASKE. 35 mm, b/w, 1000 m. 36 min. A compilation film consisting of outtakes from various feature films with Jewish actors, cut and contextualised to convey a strongly anti-Semitic message.

“WAS DU ERERBT...” (Herbert Gerdes). PR: Rassenpolitisches Amt der NSDAP, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, silent, 668 m. 33 min. BA M 23182. Propaganda short advocating for the education of the German youth according to “Aryan” ideals of racial purity. Intertitle: “To dissolve our race, the Jew advocated for the glorification of prostitution. Squalidness, ruin and infirmity were the results. 130,000 people vegetate in mental asylums, their bodies and minds ruined, as a result of venereal diseases.”

"Was Du ererbt..." - 1939

-

DER FELDZUG IN POLEN (Fritz Hippler). PR: Deutsche Filmherstellungs- und Verwertungs-GmbH, Berlin, in cooperation with the German newsreels. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 1541 m. 56 (4) min. Contains: Bearded Jewish men in front of a house entrance; faces of Jewish girls and boys, and of bearded men with caps (close-up); camera pan across a row of Jewish men, individual faces (close-up); Jews clearing rubble in a Polish town and performing road construction under German guard; work in a ditch and levelling of the ground using shovels; Jews shoveling in a bomb crater; a Jewish man loading cobblestones into a wheelbarrow, carrying them one by one. Voice-over: “The eastern Jews [Ostjuden] have quickly gotten over the shock and scurry in droves from their ghetto holes. They are, as can be seen, in a great mood. These pictures forcefully contradict the Jewish atrocity propaganda in the enemy countries. Here a selection of particularly imposing Jewish heads. This eastern Jewish nether race [“ostjüdische Niederrasse”] sent its offspring to Berlin in the years 1918 and 1919. From these were recruited the known Jewish profiteers, a fixture of the Weimar Republic. The time of dodgy deals and racketeering is now over. Working is now a must. For the first time these eastern Jews learn how to work properly.” 85 m. DER FELDZUG IN POLEN was initially cleared by the German film censors on October 5, 1939, but was quickly withdrawn. A reworked and expanded version of the film (length: 1981 m) was cleared on January 27, 1940 and released under the modified title FELDZUG IN POLEN. The anti-Semitic sequence is no longer included in the second version.

Feldzug in Polen - 1940

-

EISENBAHNANLAGEN ZERSTÖRT... / DAS SCHIENENNETZ IM POLENKRIEG (Karl Breselow, C.-E. Clausius). PR: Reichsbahnfilmstelle, Berlin. 16 mm, b/w, sound, 280 m. 34 min. Censorship date: February 20, 1940. The film documents war damage inflicted on the Polish railroads and their provisional repair. Contains a number of scenes of forced Jewish laborers, with anti-Semitic commentary. Screenings of the film were restricted to professional audiences. BA 233508.

Eisenbahn zerstört... DER EWIGE JUDE. DOKUMENTARFILM ÜBER DAS WELTJUDENTUM / THE ETERNAL JEW (Fritz Hippler). 35 mm, b/w, 1820 m. 66 min. BA M 3002. Initially planned by Joseph Goebbels as the “Ghetto Film,” this viciously anti-Semitic propaganda film consists of documentary and feature footage combined with new material shot in occupied Poland.

Der ewige Jude HELFENDE HÄNDE (Kurt Rupli). PR: Ufa, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 513 m. 18 min. BA M 3325. Abandoned apartments of Polish and Jewish emigrants are cleaned and made available for ethnic Germans.

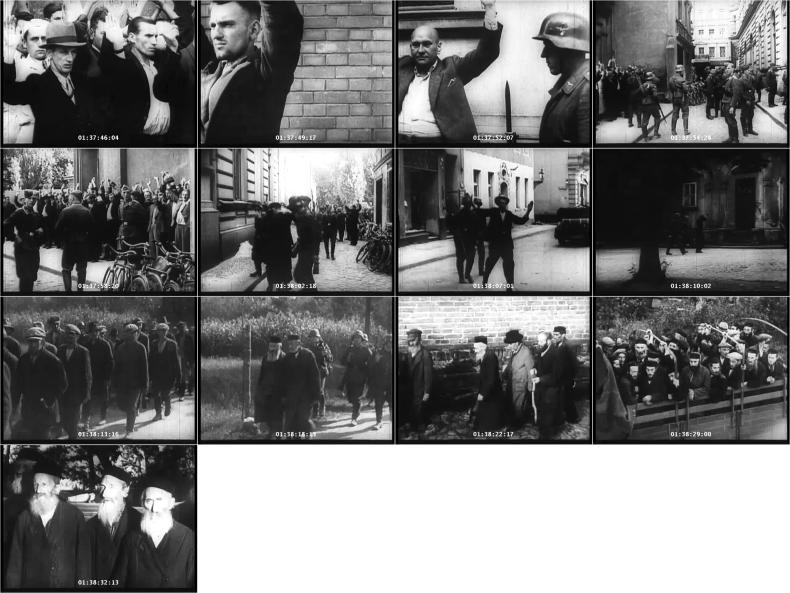

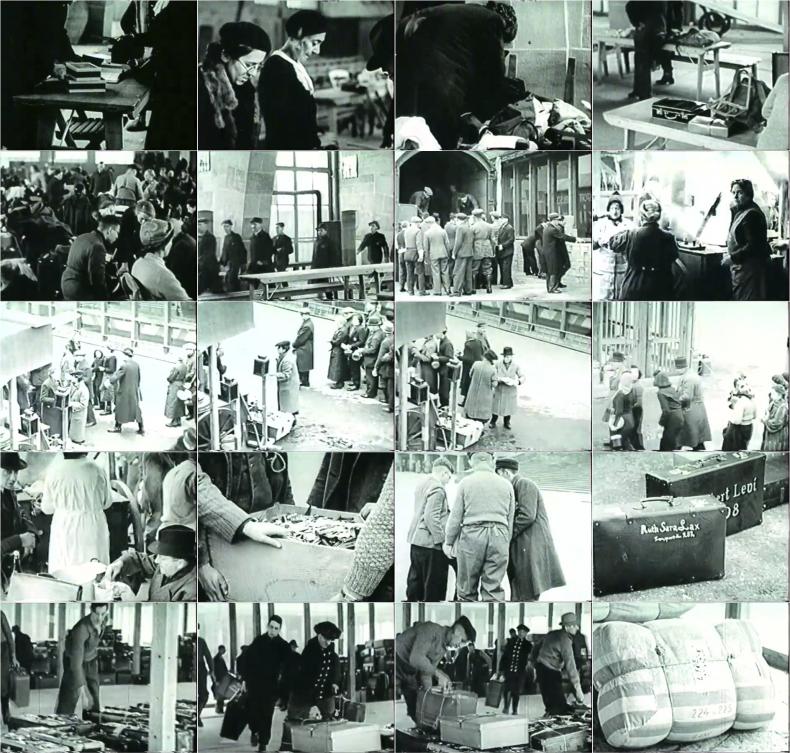

DER JUDE IM REGIERUNGSBEZIRK ZICHENAU. 16 mm, b/w, 84 m. 9 min. Camera operator: Horst Loerzer. Not submitted to the German censorship authorities but shown to audiences of the Bund Deutscher Film-Amateure (BdFA, Union of German Film Amateurs). Camera original lost, copies at BA, YV, AKH.

DER JUDE IM REGIERUNGSBEZIRK ZICHENAU - 1941

-

OSTLAND – DEUTSCHES LAND. DER EINSATZ DES LANDDIENSTES DER HJ IM OSTEN (Otto Stolle). PR: Reichsjugendführung der HJ / Foto-Vogt, Stettin. 16 mm, b/w, 228 m. 27 min. BA M 20398. Film report about the Reichsgau territories of Danzig-Westpreußen and Wartheland. Contains an anti-Semitic segment, including close-ups of Jews.

Ostland Deutsches Land RIGA NACH DER EINNAHME DURCH DEUTSCHE TRUPPEN, JULI 1941 (A: BA). PR: Heeresfilmstelle, Berlin. 16 mm, b/w, sound, 148 m. 12 min. BA, M 2834. Contains: Jews performing clean-up work in Riga; Jewish men removing rubble in front of the burnt-out and partly-destroyed St Peter’s Church; a Jewish woman picking up Soviet propaganda leaflets in a meadow. Voice-over: “Jewish parasites are forced to perform clean-up.”

RIGA NACH DER EINNAHME DURCH DEUTSCHE TRUPPEN, JULI 1941 SCHIENENWEG NACH RUßLAND. DEUTSCHER AUFBAU IM POLNISCHEN EISENBAHNNETZ (Walter Lüddecke). PR: Reichsbahnfilmstelle, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 464 m. 17 min. Contains scenes of Jews with white armbands as forced laborers clearing rubble in Warsaw (19 m). Screenings of the film were restricted to professional audiences. BA M 24123.

- 1942

-

BURGENLAND (Max Zehenthofer). PR: Kulturfilmproduktion Dr. Max Zehenthofer, Wien. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 379 m. 14 min. BA M 28271. Kulturfilm on the history and scenery of the Burgenland, following its annexation in 1938. Contains: scenes from a gypsy settlement; abandoned shops in a Jewish quarter, demolition of houses following the deportation of the Jewish inhabitants. Voice-over: “As parasitic remnants of those wars with the eastern people remained gypsies, now largely resettled and Jews, whose houses and ghettos are being demolished.” 20 m.

DASEIN OHNE LEBEN (Hermann Schwenninger). PR: Gemeinnützige Krankentransportgesellschaft mbH, Berlin. A propaganda film arguing for the value of euthanasia and the need to kill those “unfit for life.” A special cut screened only to individuals involved in the euthanasia program included scenes of patients being killed in a gas chamber. https://collections.ushmm.org

DASEIN OHNE LEBEN KAMPF DEM FLECKFIEBER. 35 mm, b/w, 473 m. 17 min. Produced by Heeresfilmstelle as Wehrmachtslehrfilm (Army Instructional Film) number 347. BA M 14552; USHMM RG-60.3298, Film ID 2504A. The film connects Jews with the spread of contagious diseases, especially typhus.

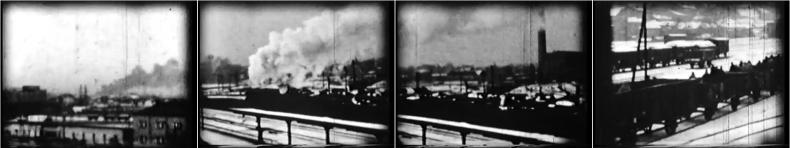

KAMPF DEM FLECKFIEBER REICHSBAHN IN RUßLAND. EIN STUMMFILMBERICHT FÜR DIE REICHSBAHNVERWALTUNG (M. Müller-Hildebrand, Paul Hinrichs). PR: Filmstelle des Reichsverkehrsministeriums, Berlin. 16 mm, b/w, 374 m. 45 min. Contains: Jewish women with yellow stars shoveling snow on a railway yard in Minsk. 4 m.

ROTER NEBEL (1942/1944, Voldemars Puuze). PR: Zentralfilmgesellschaft Ost (ZFO). 35 mm, b/w, 478 m. 17 min. Anti-Soviet propaganda film containing anti-Semitic segments. The film was initially produced to target the population of the Baltic states; it was later adapted to be shown to the “Ostarbeiter” (forced laborers from the occupied Soviet territories) inside Germany, and possibly in other European countries as part of Germany's “anti-Bolshevism” campaign. Known language versions: Estonian (PUNANE UDU), French (Pluie de sang), Latvian (SARKANĀ MIGLA), Swedish (DEN RÖDA DIMMAN); this list is incomplete.

[FIRST THERESIENSTADTFILM]. 35mm, b/w. Directed by Irena Dodalova who smuggled snippets out of the camp. Some of these fragments surfaced in Prague.

FIRST THERESIENSTADTFILM - 1943

-

CALLING MR. SMITH (UK 1943, Franciszka and Stefan Themerson). 35 mm, Dufaycolor, 10 min. Anti-Nazi propaganda short which incorporates imagery of Nazi atrocities.

CALLING MR. SMITH - 1945

-

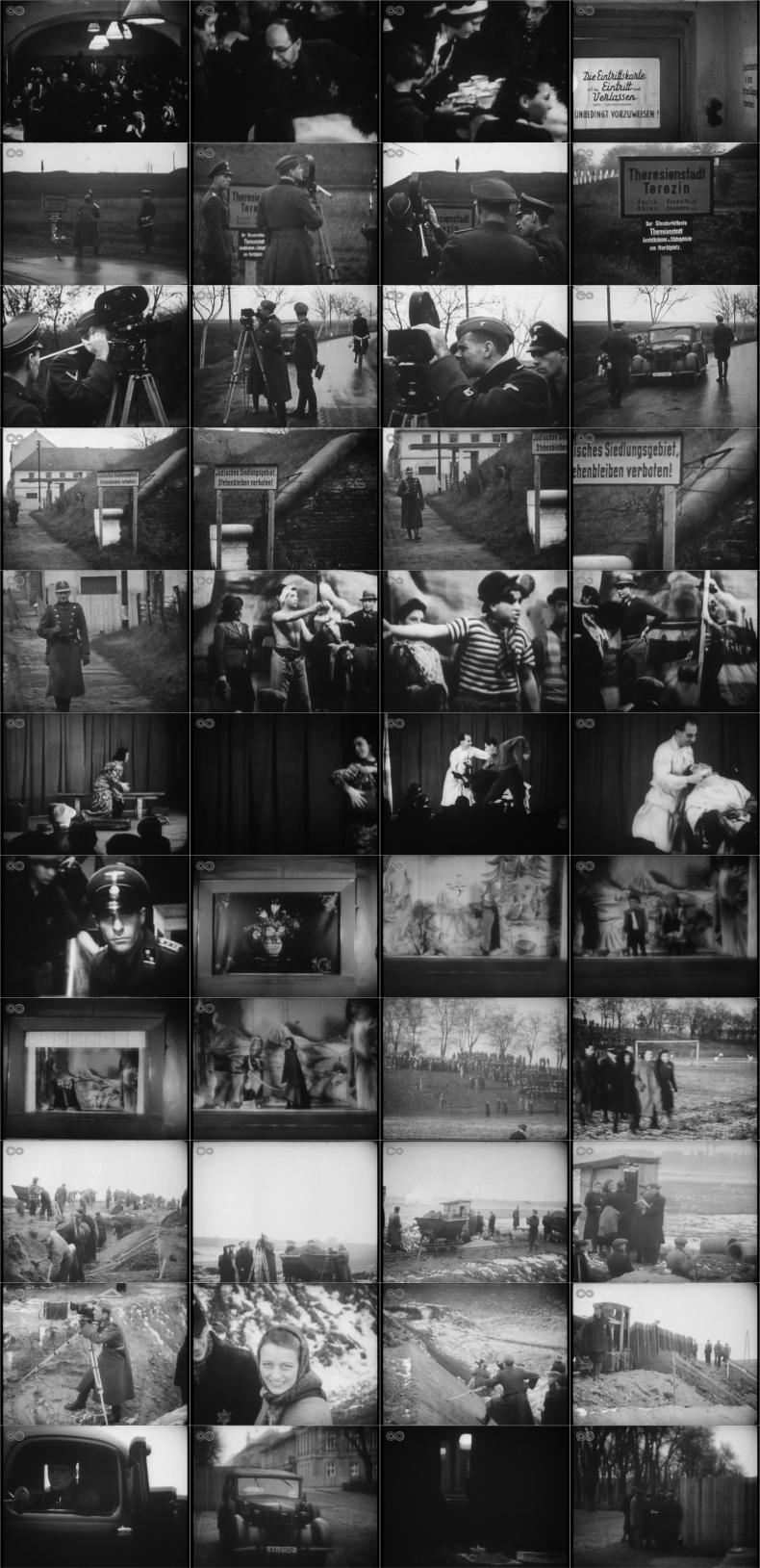

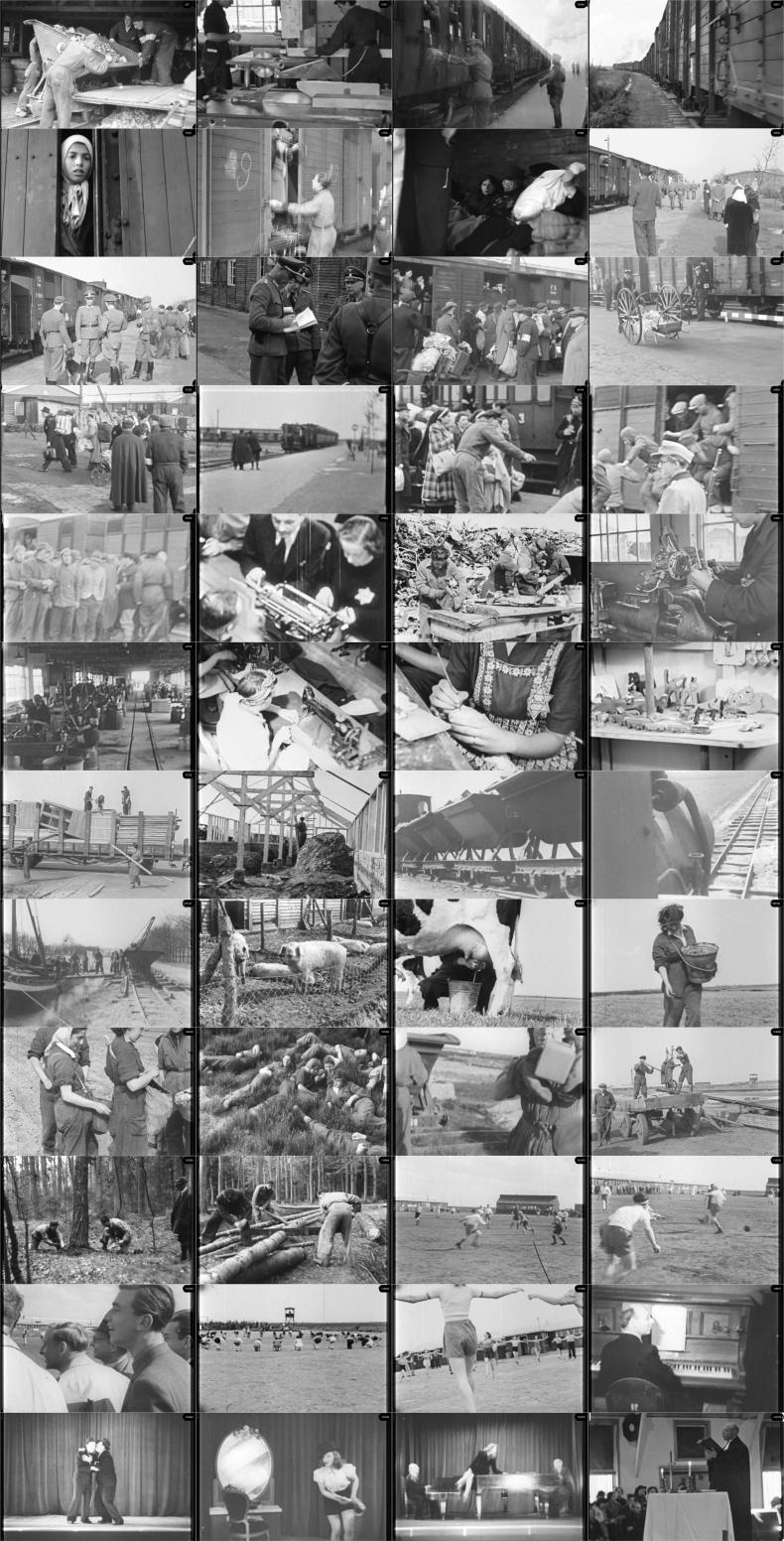

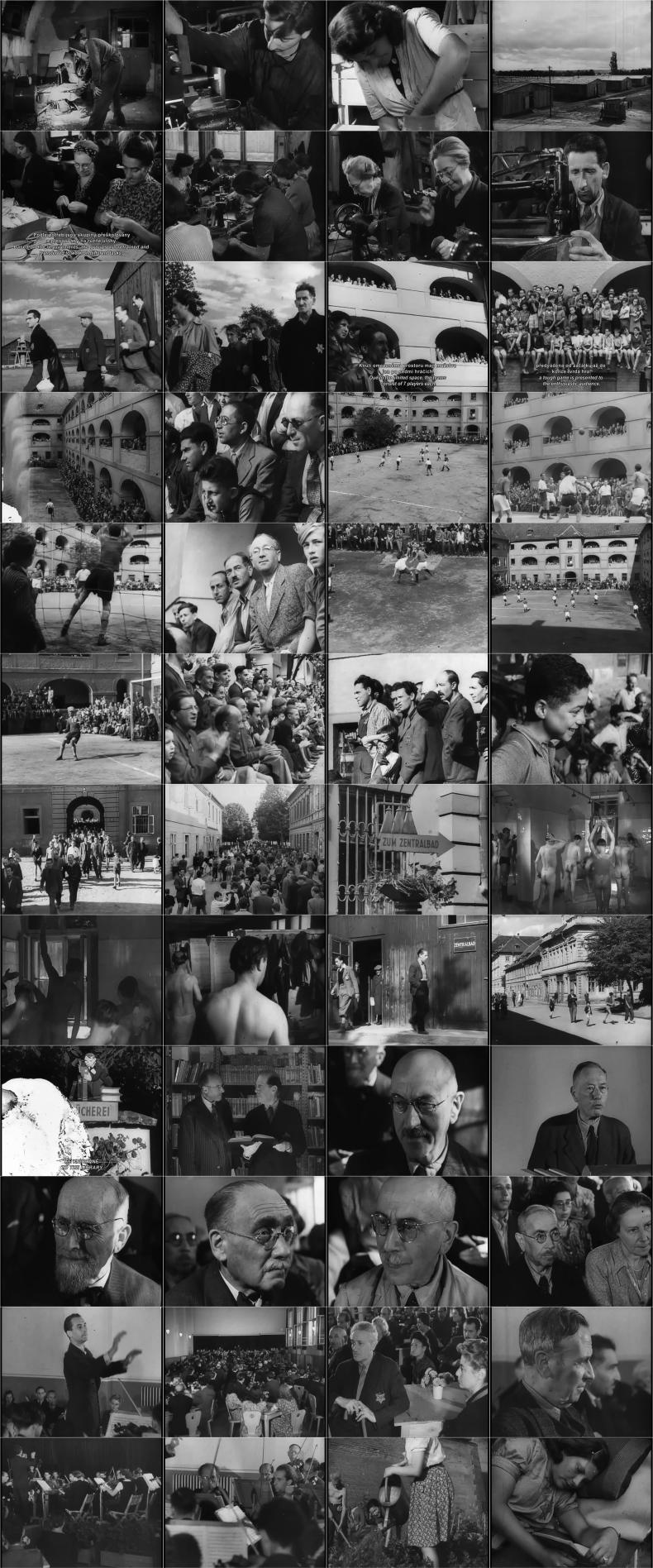

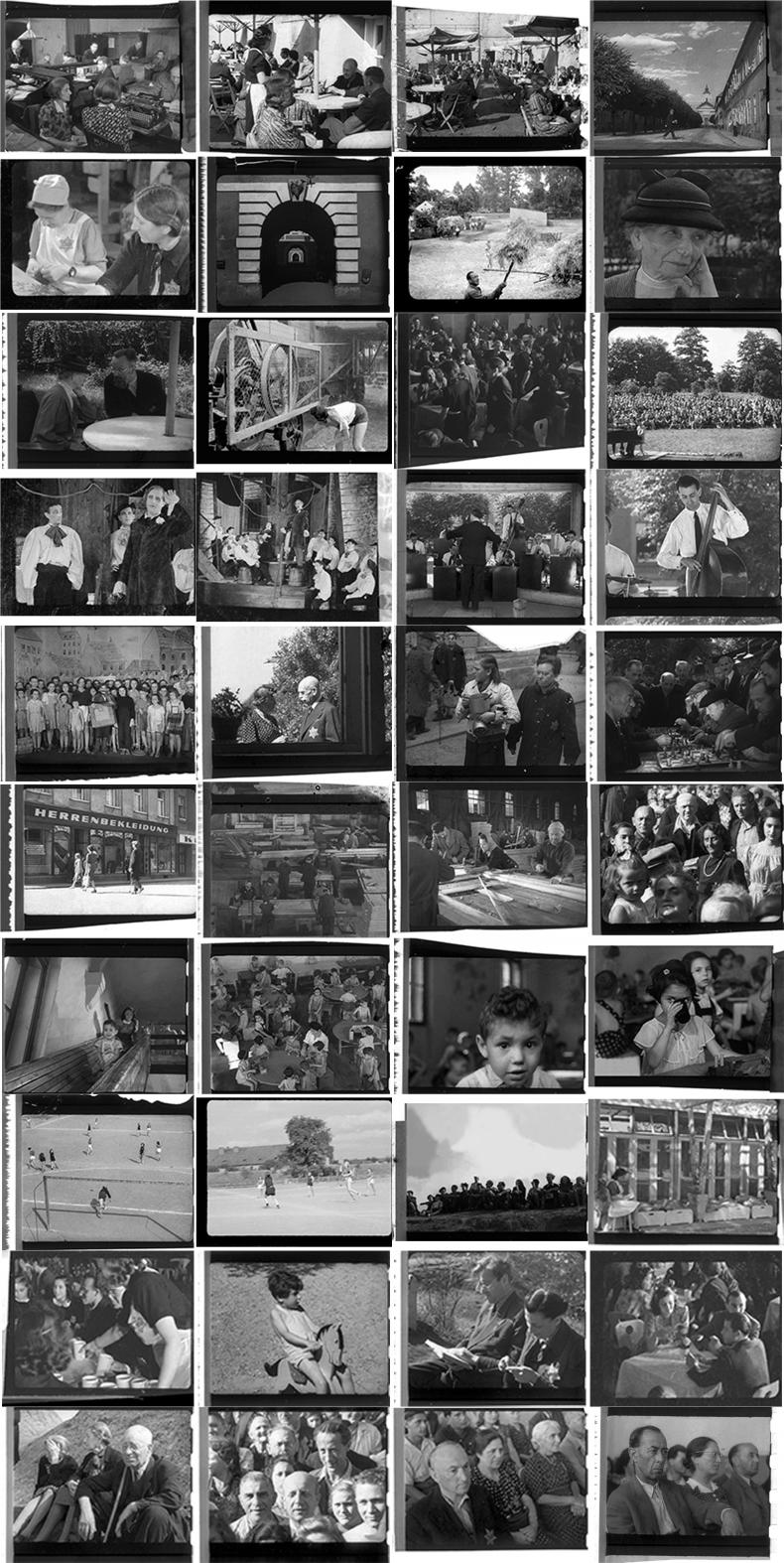

THERESIENSTADT. EIN DOKUMENTARFILM AUS DEM JÜDISCHEN SIEDLUNGSGEBIET. 35 mm, b/w. >21 min. Only three continuous fragments of the film survive: approximately 15 minutes discovered in Prague in 1964; another 7,5 minutes, including the main title, in 1987; and another sequence in 1997. Additionally, 149 single frames of lost shots have survived and further 229 shots can be reconstructed from the sketches made by Jo Spier in set.

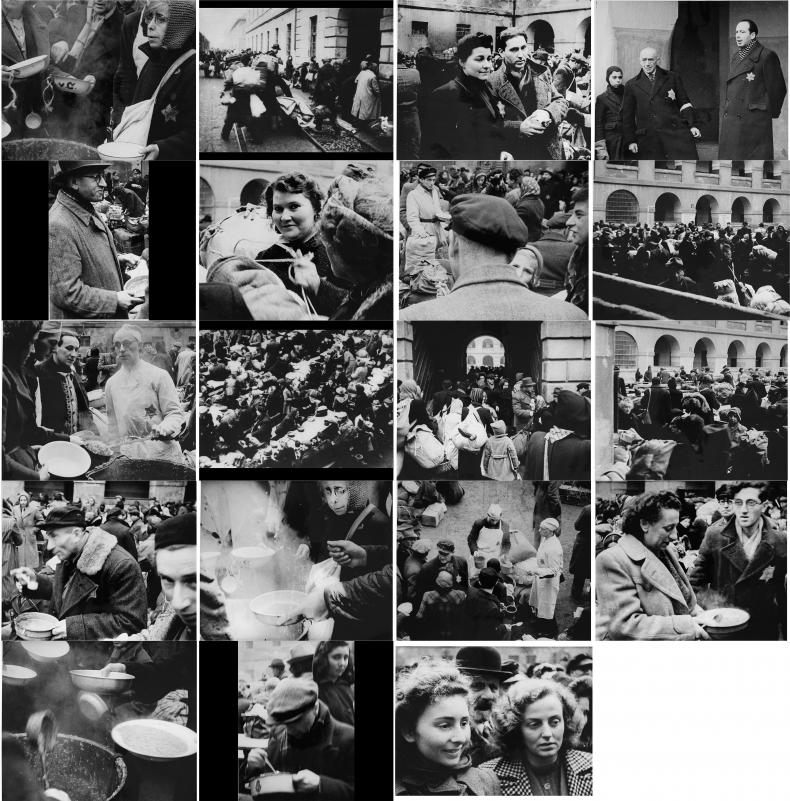

THERESIENSTADT. EIN DOKUMENTARFILM AUS DEM JÜDISCHEN SIEDLUNGSGEBIET. Fragment from Yad Vashem. THERESIENSTADT. EIN DOKUMENTARFILM AUS DEM JÜDISCHEN SIEDLUNGSGEBIET. Fragment found in Prague. THERESIENSTADT. EIN DOKUMENTARFILM AUS DEM JÜDISCHEN SIEDLUNGSGEBIET. Fragment found in 1997 THERESIENSTADT. EIN DOKUMENTARFILM AUS DEM JÜDISCHEN SIEDLUNGSGEBIET. Einzelkader.

Footage

Footage in this context refers to any unfinished films, unedited footage, outtakes, B-roll elements etc. produced by statal organisations, such as the Propagandakompanien.

- 1933

-

BILDBERICHTE 1932-1933, p: Landesfilmstelle Mitteldeutschland-Sachsen der NSDAP, 16mm, b/w., 3 min. Anti-Jewish boycott in Halle, 1.4.1933. USHMM: RG Number: RG-60.4634, Film ID: 2842. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1004138 .

Bildberichte 1932-33 - 1935

-

KREISAPPELL IN MERSEBURG AM 25. AUGUST 1935. 16mm, b/w., 1min., p: Gaufilmstelle Halle-Merseburg der NSDAP. USHMM: RG Number: RG-60.4641, Film ID: 2842. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1004145 .

KREISAPPELL IN MERSEBURG AM 25. AUGUST 1935 - 1936

-

APPELL DES KREISES LIEBENWERDA IN FALKENBERG, 16mm, b/w., 6 min., p: Gaufilmstelle Halle-Merseburg der NSDAP. USHMM: RG Number: RG-60.4997, Film ID: 2887. https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1004500 .

APPELL DES KREISES LIEBENWERDA IN FALKENBERG - 1939

-

POLENFELDZUG (AVT) (1939) (A: BA). 35 mm, b/w, 4924 m. Raw PK footage (18 reels). 180 min. Contains: 1. Jews as forced laborers perform road construction work (16 m); 2. Bearded Jews (CU) repairing a road under German guard (23 m); 3. Jews in civilian attire clearing rubble (13 m); 4. Camera pan across a holding pen, with tightly-packed Jews forced to sit on the ground (11 m). BA BSP 13626.

POLENREISE DES DR. FRANK (A: BA). PR: probably Ufa-Wochenschau, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, sound, 408 m. 15 min. BA M 24129, and outtakes, silent, 404 m 15 min. BA M 24128. A report on Generalgouverneur Dr. Hans Frank touring occupied Poland. Includes an anti-Semitic segment of Jews in Krakau, with close-ups. Voice-over: “Krakau, the old German town on the upper Weichsel, built by Germans, shaped by German civic diligence, was inundated from the 16th century with eastern types [“Typen des Ostens”], who eventually came to dominate the streets.”

POLENREISE DES DR. FRANK SIX CITIES. 50 min. Six documentary films shot before the outbreak of World War II, documenting Jewish life in Poland. See entry in bibliography for details.

- 1940

-

[ADOLF SEISSEL / BELZEC FILM]. Footage shot over the course of one week in the autumn of 1940 by Adolf Seissel, a police officer, as reported to the Schulungsamt of the SS-Hauptamt. At the time approximately 3,000 Jews were located in several work camps in Bełżec and the surrounding area, with work details performing forced labor such as earthworks and border fortifications. The death camp at Bełżec was established approximately one year later. Seissel's filming may have coincided with the closure of the work camps in October of 1940. The film is lost. Seissel went on to shoot another film in a camp at Lublin, see the separate entry under [ADOLF SEISSEL / LUBLIN FILM].

[ADOLF SEISSEL / LUBLIN FILM]. Footage shot by police officer Adolf Seissel in Lublin, as communicated to the Schulungsamt of the SS-Hauptamt. Seissel reported to have received permission for filming from Odilo Globocnik (SSPF Lublin), and that he shot footage in the “Judenlager Lublin.” Work title: “Juden unter sich” (“Jews Amongst Themselves”). The film is lost. Seissel previously shot footage in Bełżec, see [ADOLF SEISSEL / BELZEC FILM].

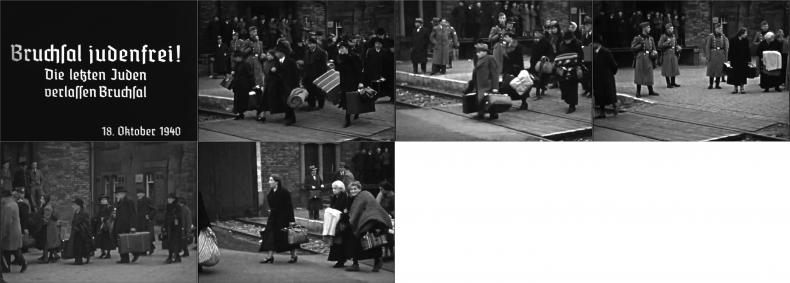

DEPORTATION VON BRUCHSAL NACH GURS. b/w. 1 min. Source: Stadtarchiv Bruchsal.

DEPORTATION VON BRUCHSAL NACH GURS [FILM SHOT BY THE SS IN CAMP WESTERBORK, NETHERLANDS]. Reported by Kurt Schlesinger.23 Lost.

КРАКОВСКИЙ КУЛЬТУРФИЛЬМ (A: GFF) / DAS KRAKAUER GHETTO (A: BA). PR: unknown. 35 mm, b/w. Preservation elements: GFF 5663; BA only has a VHS copy. Raw footage, possibly from an unfinished Kulturfilm: scenes of Krakow during the German occupation; Jewish living quarters in Kazimierz; the squalid living quarters in the ghetto are contrasted with representative buildings in the city; close-ups of Jews.

[POGROM IN WARSAW, AUGUST 11, 1940]. An incident reportedly filmed by German war correspondents (Friedrich (2002) 612). The footage is lost.

- 1941

-

AUS LODZ WIRD LITZMANNSTADT (A: BA) / ŁÓDŹ BECOMES LITZMANNSTADT (A: USHMM). Producer: unknown. 35 mm, b/w, 702 m. 25 min. BA M 3578. USHMM RG-60.4341, Film ID 2796, https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/irn1003805. Another version of this film is preserved at NARA, 242 MID 6219, and a silent print at Gosfilmofond, GFF 3252. See also https://progress.film/record/25007. Unfinished propaganda film about the development of Łódź as a “German” city, contrasting squalid living quarters with the new building program.

ERSTE KAMPFHANDLUNGEN IM SÜDABSCHNITT DER OSTFRONT, RUßLAND, SOMMER 1941 (A: BA). 51 min. PR: Heeresfilmstelle, Berlin. 16 mm, b/w, 427 m, 37 min. Contains: Deportation of Jewish men on the outskirts of a village or town; Jewish men sitting on the ground, guarded by Germans; individual groups of Jews sitting on the ground (CU); Jewish men are marched to a lorry and forced to climb aboard; SS officers of Einsatzgruppe C supervising the deportation. 19 m.

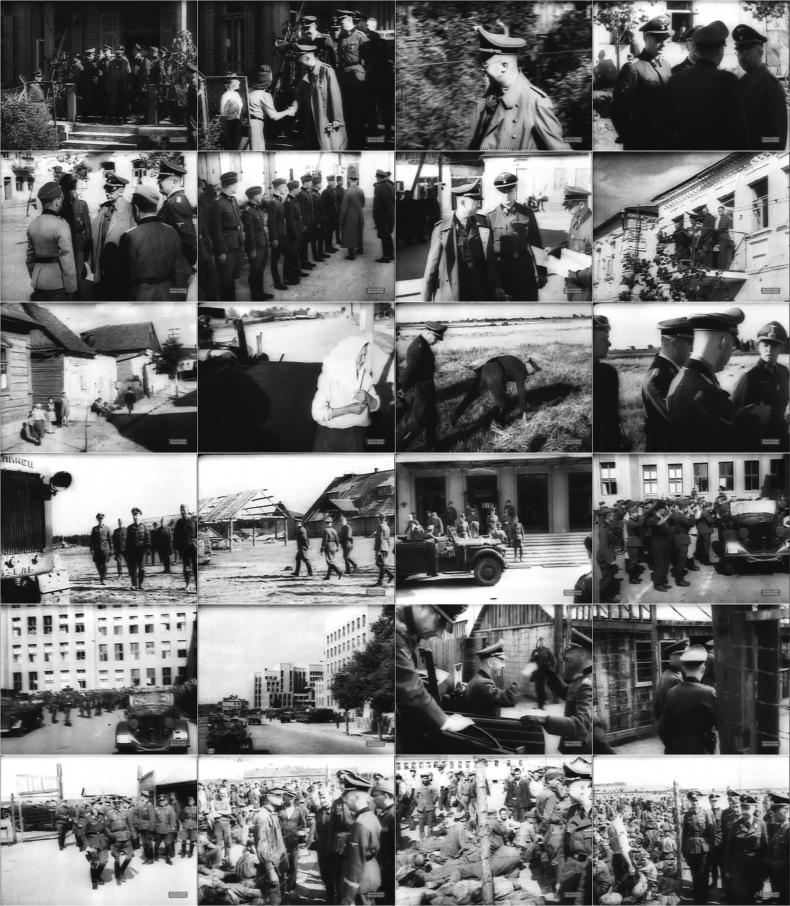

Erste Kampfhandlungen im Südabschnitt der Ostfront, Russland, Sommer 1941 [HIMMLER'S INSPECTION TOUR TO MINSK, AUGUST 1941]. 35 mm, b/w, original length unknown. 3 min. Camera operator: Walter Frentz. Fragment included in the three-hour version of THE NAZI PLAN (USA 1945, Ray Kellogg), screened at IMT Nuremberg as exhibit PS-3054. The whereabouts of the physical elements obtained by the OSS for the production of THE NAZI PLAN is unknown.

HIMMLER'S INSPECTION TOUR TO MINSK, AUGUST 1941 JUDEN BEI DER ARBEIT IN BRESLAU (A: BA). PR: Deutsche Wochenschau GmbH, Berlin. 35 mm, b/w, 60 m. 2 min. BA preservation elements: M 20230. Jews as forced laborers performing construction work. Note: The German Bundesarchiv locates the film has having been shot in Breslau, however the Reichsfilmarchiv card indexindicates it may have been shot in the Generalgouvernement instead, and as such may have been produced by FIP rather than Deutsche Wochenschau.

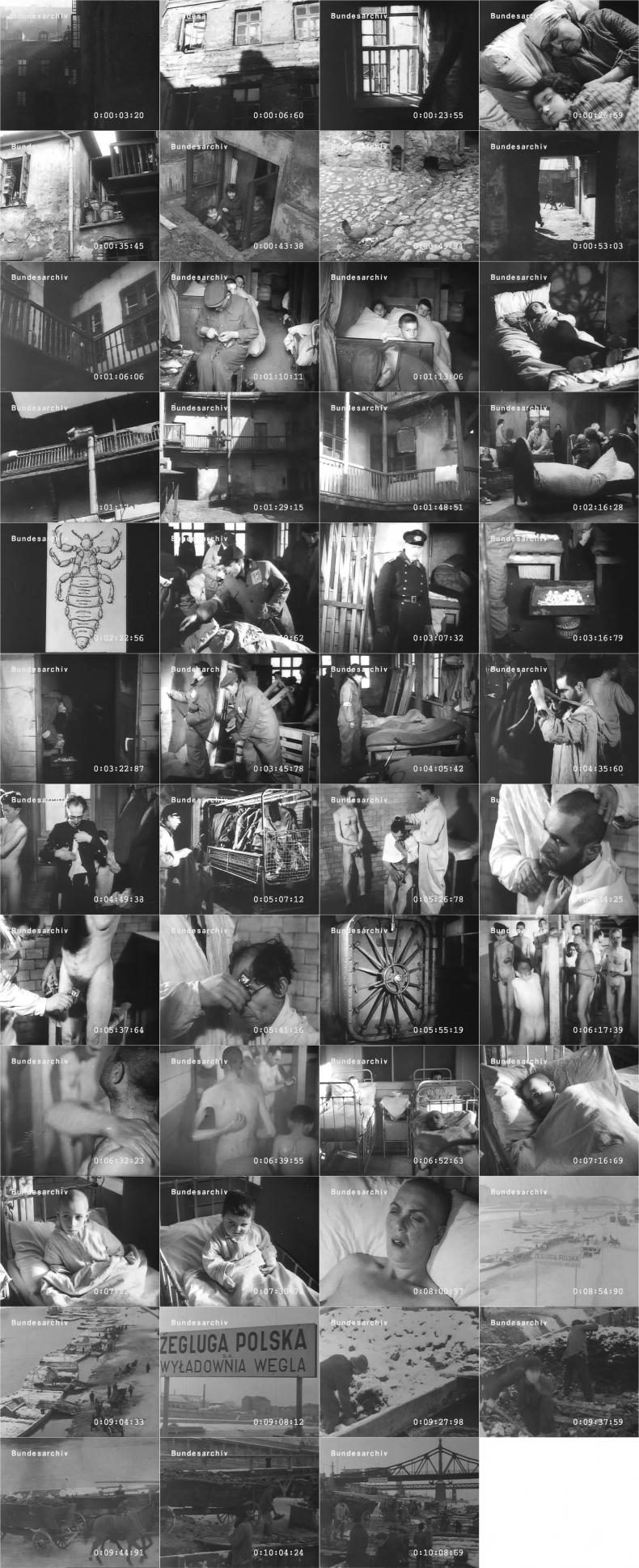

JUDEN BEI DER ARBEIT IN BRESLAU JUDEN, LÄUSE, WANZEN / JEWS, LICE, BUGS (A: USHMM). 35 mm, b/w, 310 m. 11 min. Presumably produced by Film- und Propagandamittel-Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH (FIP) in the General Government. German title assigned by Reichsfilmarchiv. BA preservation elements: M 17427. USHMM RG-60.3295, Film ID 2504A.

JUDEN, LÄUSE, WANZEN JUDENDEPORTATION IN STUTTGART (A: BA) / STUTTGARTER KRIEGSFILMCHRONIK. 16 mm, b/w, 58 m. 7 min. Deportation filmed by Gestapoleitstelle Stuttgart. Source: Stadtarchiv Stuttgart.

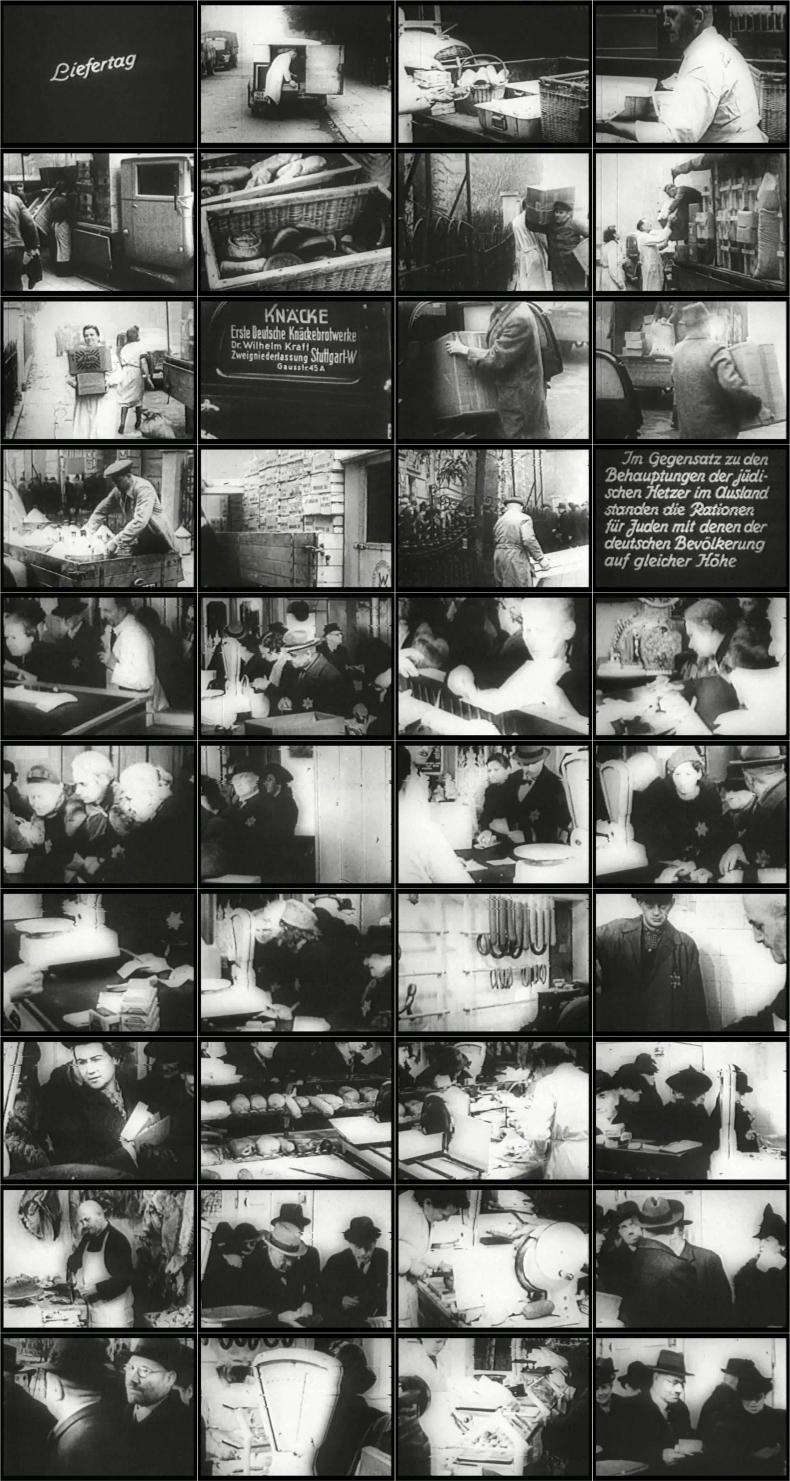

JUDENDEPORTATION IN STUTTGART LEBENSMITTEL-SONDERVERKAUFSSTELLE FÜR JUDEN IN DER EHEM. GASTWIRTSCHAFT "ZUM KRIEGSBERG" / JUDENDEPORTATION IN STUTTGART (A: Stadtarchiv Stuttgart). 16 mm, 60 m. USHMM RG-60.4636, Film ID 2842. Part of the Stuttgart “Kriegschronik,” this film shot by local cinematographer Jean Lommen depicts a special food purchasing store for Jews; intertitles claim the rations are on par with those for the German population.

LEBENSMITTEL-SONDERVERKAUFSSTELLE FÜR JUDEN [MOGILEV GASSING]. 16 mm (?), b/w, original length unknown. Camera operator: possibly Arthur Nebe who supervised the gassing experiment in Mogilev. Camera original lost. 1 min. 35 mm blow-up of a fragment (ca. 18 m) included IN NUREMBERG: ITS LESSON FOR TODAY (USA 1948, Stuart Schulberg). The original film was found no later than June 1947 in the former Berlin home of Arthur Nebe, its present whereabouts are unknown.24

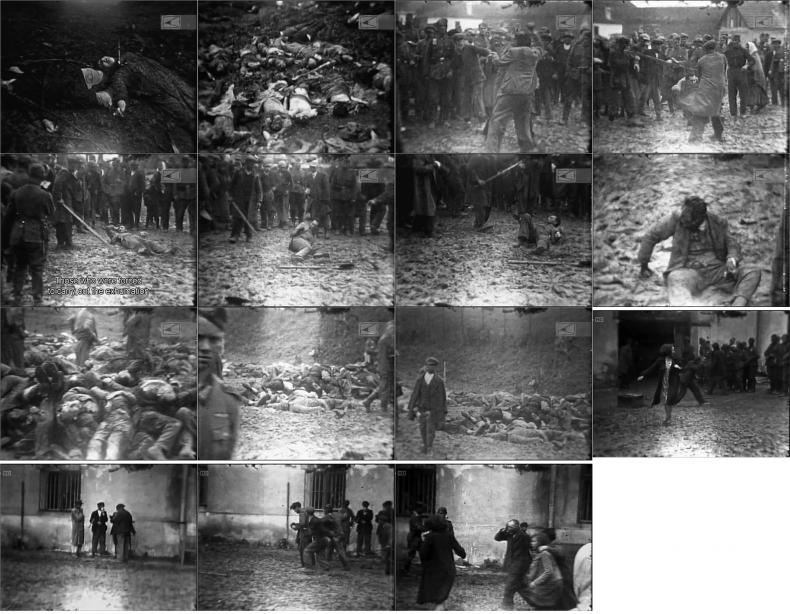

MOGILEV GASSING OPFER RUSSISCHER MASSAKER IM BALTIKUM UND IN SÜDRUßLAND (A: BA). PR: Heeresfilmstelle, Berlin. 16 mm, b/w, 176 m. 21 min. BA M 1804. Footage shot by cameramen of the Wehrmacht’s Heeresfilmstelle, which operated independently from the Propagandakompanien. Contains: Exhumation of corpses after the capture of Lemberg by German troops on June 30, 1941. Jews forced to dig out corpses from a mass grave in the yard of Brigidki prison; civilians beating Jews with sticks; camera pans across the yard, which is full of corpses; prison wall showing bullet holes; the fire-damaged facade of Brigidki prison. 60 m.

OPFER RUSSISCHER MASSAKER IM BALTIKUM UND IN SÜDRUßLAND [PK footage: Jewish district in Lublin]. PK 666, February 4, 1941. Lost.

[PK footage: "The Jewish Ghetto in Litzmannstadt"]. PK 689 – Rolf Hermann Carl, February 1941. Lost.

[PK footage: "Jewish work camps in Litzmannstadt"]. PK 689 – Rolf Hermann Carl, May 13, 1941. Lost.

[PK footage: Judenaktion in Paris]. Propaganda-Abteilung Frankreich, August 19, 1941. Lost.

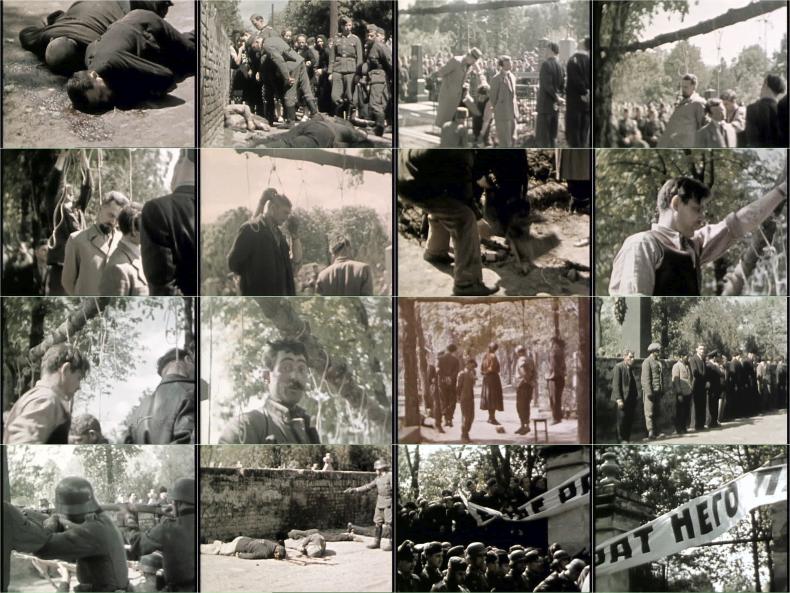

[PK footage: mass execution of Jews on the road to Niš, Serbia]. Propaganda-Abteilung Südost – unknown cameraman, October 8, 1941. Lost. Members of Prop.Abt. Südost were specially designated to document the execution.

[PK footage: Jewish prisoners in Minsk]. Footage shot by an unidentified PK or police cameraman. Lost.

[PK footage: Salaspils concentration camp]. Footage shot by an unidentified SS-Kriegsberichter in late 1941. Lost.

[PK footage: Jews digging a grave]. PK 612 - Alfred Fernau, July 4, 1941. Censorship report: “Soviet tanks in forest – burial of Soviet soldier by his comrades – Jews digging grave – captured Soviets.” Lost.

TÄTIGKEIT DER POLIZEI IM GENERALGOUVERNEMENT (A: BA). PR: presumably Film- und Bildstelle der Technischen Polizeischule. 35 mm, b/w, 427 m. 15 min. BA M 24496. Contains scenes of a police raid in the Jewish quarter in Krakau (Kazimierz); men being arrested; another raid on a market in Krakau; arrested Jews are being led under guard to the Kriminal-Kommissariat of the Sicherheitspolizei in Miechow; SD officers inspecting confiscated weapons; camera pan across the arrested men. The film survives as a rough cut without titles and sound.

TÄTIGKEIT DER POLIZEI IM GENERALGOUVERNEMENT VOLKSGRUPPE IM AUFBRUCH (A: BA). PR: NSDAP, Gau Wien. 16 mm, b/w, 189 m. 23 min. Raw footage from a film about the ethnic German groups in Slovakia. Contains: market square in a Slovakian town (possibly Neutra); Jews as pedestrians; a Jewish boy (with armband) being shooed away from a store entrance. The camera repeatedly follows Jews as they shop at the market. 24 m.

- 1941?

-

ENTLAUSUNG IN POLEN. 35 mm, b/w, 30 m. 1 min. Presumably produced by Film- und Propagandamittel-Vertriebsgesellschaft mbH (FIP) in the General Government. Title assigned by Reichsfilmarchiv. BA only has a nitrate print, BLB 26977.

- 1942

-

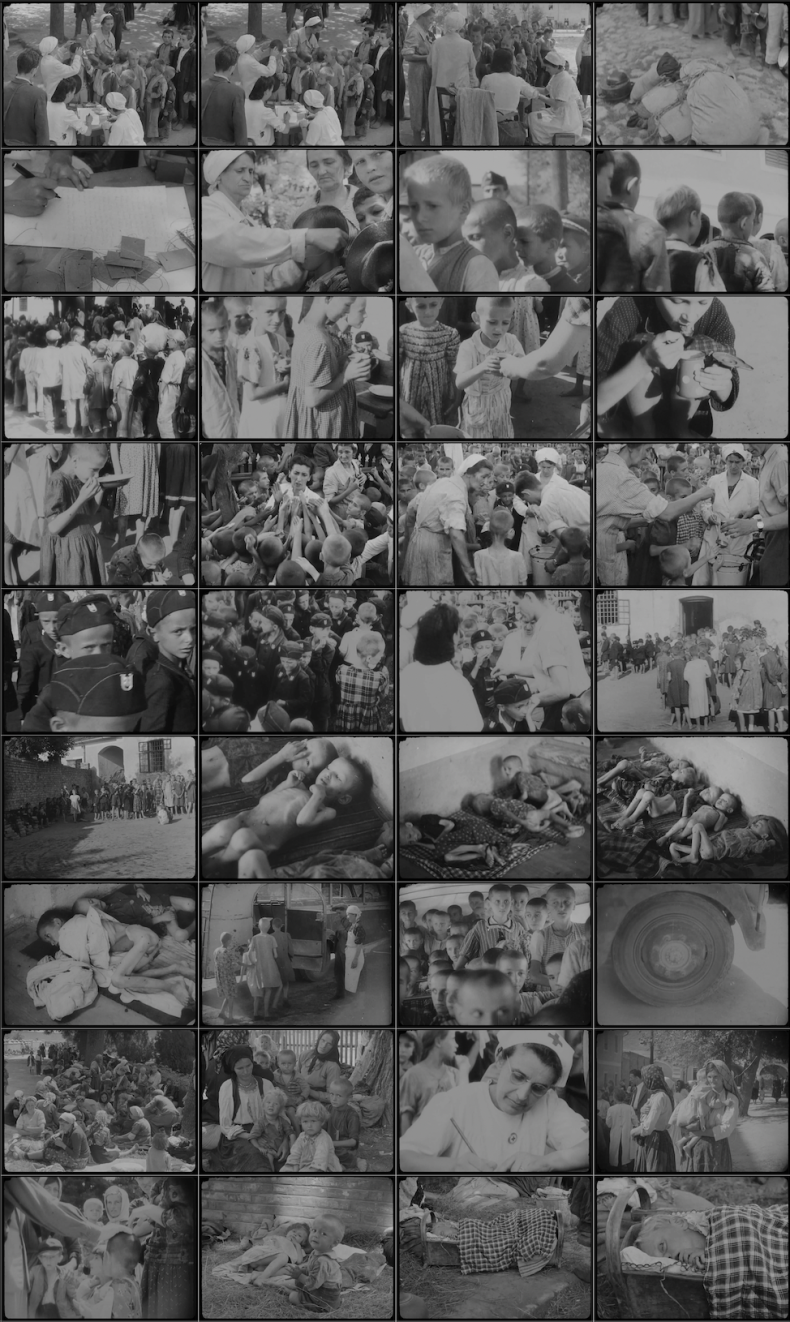

[CHILDREN IN NOVA GRADIŠKA CONCENTRATION CAMP]. 35? mm, b/w, 4 min, original length unknown. Jugoslovenska Kinoteka: [inventory number unknown]; USHMM RG-60.5834, Film ID 4365; AKH M 588. Emaciated and malnourished children being given food and administered medical care at Nova Gradiška, a sub-camp of Jasenovac concentration camp. Some of the children are wearing what appears to be the uniform of the Ustaše Youth (Ustaška mladež). The context and the possible presence of members of the International Red Cross is unclear. The footage may have been shot by a cameraman of the Croatian newsreel and was spliced into the short STRAZA NA DRINI (1942, Branko Marjanovic), which was screened at the 23rd Biennale in Venice, held in 1942.

CHILDREN IN NOVA GRADIŠKA CONCENTRATION CAMP [DEPORTATION OF JEWISH FAMILY FROM PRAGUE]. Producer: unknown. 35 mm, b/w. 1 min. This material was first used in AKTION J (GDR 1961, Walter Heynowski), and may have been filmed as part of the first Theresienstadt film (1942) - see under films, 1942, [FIRST THERSIENSTADT FILM].

DREHARBEITEN IN THERESIENSTADT (A: BA). 16 mm, b/w, 96 m. 11 min. BA M 20619. This 16 mm film was shot by SD cameraman Olaf Sigismund alongside the 1942 film project in Theresienstadt. Its categorisation—statal filming or merely an amateur film—has not been conclusively established.

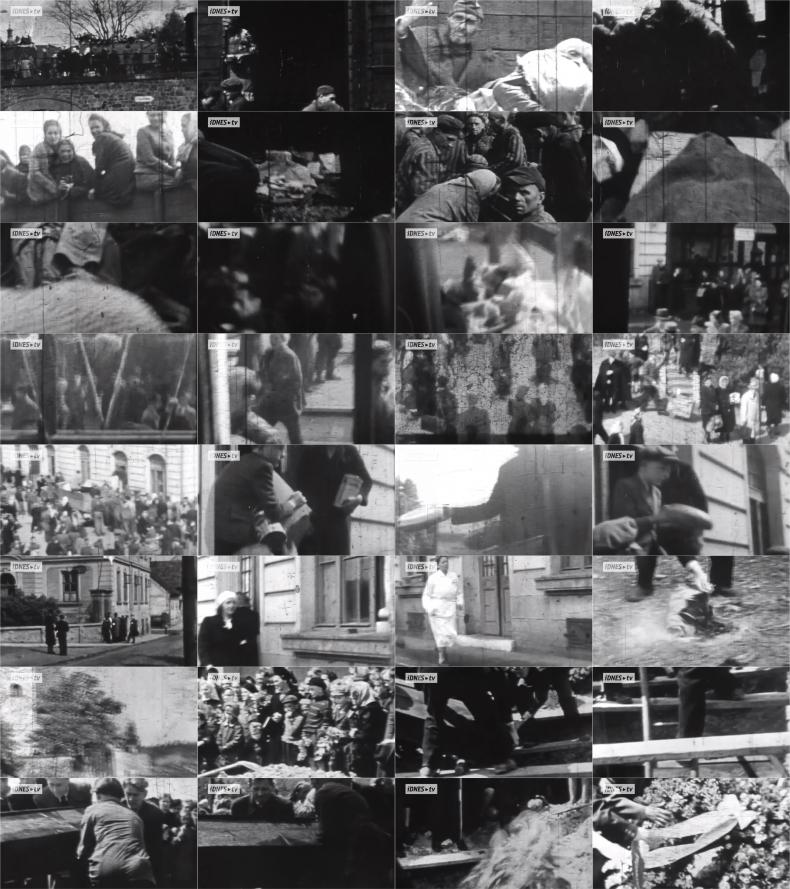

DREHARBEITEN IN THERESIENSTADT DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS (A: USHMM) / ZYDZI POLSCY / THE POLISH JEWS / JUDENDEPORTATION IN POLEN (A: BA). 16 (?) and 35 mm, b/w. 8 min. Segment from a postwar 16 mm archival compilation with added musical score produced by the former Documentary and Feature Film Studio (WFdiF), Warsaw, Poland. Source material lost and provenance unknown. This compilation footage is among the most commonly used materials and is routinely seen in historical documentaries.

DEPORTATION OF POLISH JEWS - WFDIF GHETTO IN DABROWA GORNICZA AND BEDZIN (A: USHMM) / DIE JUDEN VON DOMBROWA (BA). 35 mm, b/w, 241 m. 11 min Source: NARA, 242 MID 6198u.

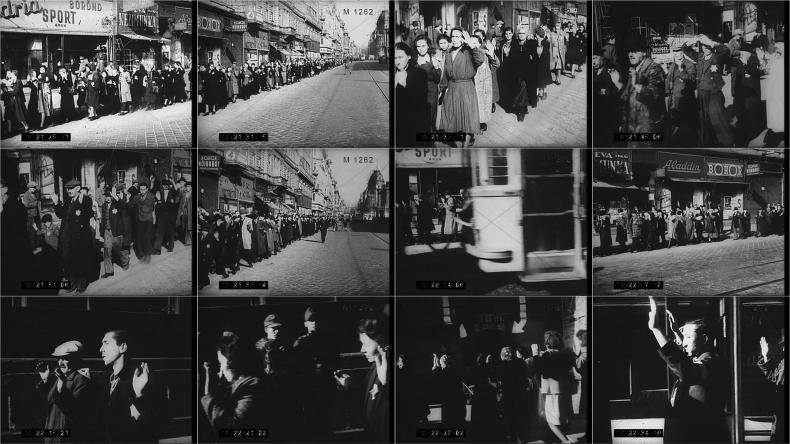

GHETTO IN DABROWA GORNICZA AND BEDZIN GHETTO (A: BA) / WARSAW GHETTO. 35 mm, b/w, 1723 m. 63 min. Camera operators: Hans Juppenlatz, Willy Wist. Rough cut discovered postwar at East German Film Archives. Nitrates destroyed, preservation copies at BA, M 17411.