Destroyed Statues, a Bolex 16 mm Camera, and an Old Jeep

The Traces of History in FLAT TYRE

Table of Contents

Secret Publics

Digital Digging

Movie Theatre(s) of Memory

Filmography of the Genocide

Exacting the Trace

Destroyed Statues, a Bolex 16 mm Camera, and an Old Jeep

“…will you show that on your British television?” ACCEPTABLE LEVELS as Historiographic Metafiction

Work and Life

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Ko, Li-An. “Destroyed Statues, A Bolex 16 mm Camera, and an Old Jeep: The Traces of History in FLAT TYRE.” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces, no. 4 (February 2022): 1–16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18103.

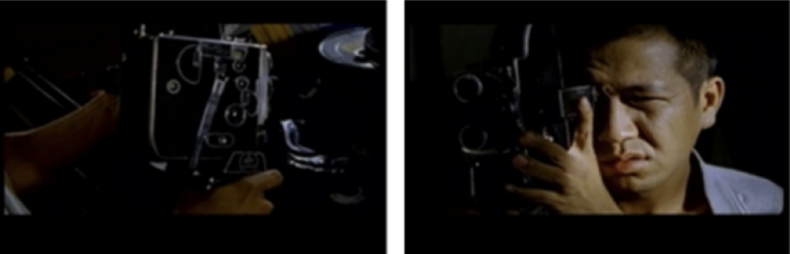

A black-and-white photograph of the seashore is placed against the wall of a stark room. Nearby is Ning, who adores the photos made by her boyfriend, Meng, formerly a photographer and now a documentarian. Lying like a sculpture nude on the floor, Ning is sleeping. Her sleep is interrupted by Meng, who sleeps beside her but apparently has nightmares. Ning tries to offer him some solace by touching his face. Hearing sounds that resemble gunshots, Meng awakes. He leaves Ning for another room; there, he takes a Bolex 16 mm camera out from a leather box and assembles the handle and viewfinder to the machine in the light of the break of dawn. He winds up the camera, presses the release, and shoots. The clattering of the running camera is clearly heard as Meng immerses himself in the shooting…

On this poetic opening sequence of FLAT TYRE (Ming-Chuan Huang, TW 1998),1 Erik Bordeleau considers Meng’s awakening from the nightmare a pivotal form of historical presentation (“chaque présentation de l’historie doit commencer par le réveil,” as Bordeleau quotes Walter Benjamin).2 Yet, what history is to be presented and how? As implied in the following dreamlike scene in the opening sequence in which Meng and his fellow cameraman Jianxian climb to the summit of Mount Jade to film a damaged monument, the history to be presented is the past of Taiwan represented by public statues that were destroyed or abandoned across the island, and the method used to present the history is a film.

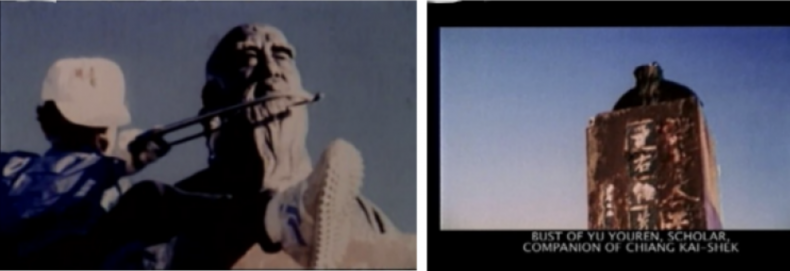

Since the end of martial law in 1987,3 monuments that were erected to commemorate past rulers have become more and more controversial for Taiwanese society. For example, many public statues that commemorate the late dictator Chiang Kai-Shek (1887–1975), the leader of the KMT government in Taiwan (1949–1975), are more often demolished as a result of the current democratization of the island.4 Besides, the statues of other political figures, such as Yu You-Ren (1879–1964), a former president of the Control Yuan of the KMT government,5 and Wu Feng (ca. 1699–1769), a Han Chinese official who tried to end the headhunting—an aboriginal tradition in Taiwan—were also destroyed by opponents of the KMT.6 The destruction of the statues reflected one of the most noticeable political phenomena in the post-martial law society of Taiwan during the 1990s.7 Until today, the statues of the past rulers, especially Chiang, are still destroyed or vandalized during the public commemorations of the victims of the KMT authoritarian regime and in protests for transitional justice.8

As Meng and Jianxian’s shooting of the damaged monument on the peak of Mount Jade in the opening sequence implies, FLAT TYRE intends to record the decaying statues of the political figures mentioned above. Moreover, not merely recording the political monuments, the film captures religious statues that were erected in a great number while the political ones were demolished, despite the fact that part of them could also be ruined later for certain reasons. In other words, the film records the aforementioned statues by focusing on their destruction and tries to explore the historical meaning that these “marginalized” statues represent. As the director Ming-Chuan Huang emphasizes, “the marginalized” objects enable us to discover the “traces of history” and thus are worthy of being filmed.9

FLAT TYRE records real statues and nevertheless it is as a fiction film, not a documentary. However, the protagonists are indeed two documentarians—Meng and Jianxian—who take a Bolex 16 mm camera and drive an old jeep from one location to another to search and shoot the real (broken) statues in the landscapes of Taiwan. In the process, they discuss not only background information about the filmed objects but also how to shoot them. With the simple tools, they attempt to capture the unique statues as historical objects in the physical world. Additionally, the film introduces other characters, such as Ning, Meng’s girlfriend who has no interest in those “lifeless stones” and struggles to develop her own career as an actress against the background of a sharp downturn in the local film industry, and a mysterious man, who has been as silent as a statuette since the protagonists met him. In these ways, FLAT TYRE portrays the relationships between the statues and Taiwanese people from a bottom-up angle and meanwhile presents a meta-perspective on the practice of documenting the public statues by means of cinema.

The meta- and bottom-up perspectives, as well as the form of fiction film, make FLAT TYRE a special case among films that deal with destroyed or decaying artifacts and memorials.10 Besides, scholars have discussed FLAT TYRE as a film representing the “ruinscapes” in Taiwan and an alternative example in the broad context of “ecocinema”11 and as a visual work resistant to the images of “landscaped space” shown in the mainstream media with marginalized space and the aesthetics of ruins.12 However, in analyzing the images of the film the meta-perspective which marks a fundamental characteristic of the work was hardly explored in existing literature. By depicting the documentarians who travel around the island of Taiwan with their camera and jeep to search the public statues, FLAT TYRE in fact invites the viewer to join the search, to “trace” the broken statues with the images of the film, and at the same time to reflect on how the cinematic images of the statues are created, as well as how the history of Taiwan is interpreted with the images in the film. Therefore, in what follows, this article will firstly discuss statues recorded and presented in FLAT TYRE and secondly explore the film’s reflection on the practice of documenting the statues by means of cinema. Thirdly, the article aims to look into the work as a cultural practice of tracing the statues as the traces of the history of Taiwan, and, lastly, analyze how the history is (re)interpreted by the director with the cinematic images.

Record

Showing the filming work by Meng and Jianxian as documentarians of the political and religious statues in Taiwan, FLAT TYRE uses a considerable number of documentary images of the statues, among which some are still sound but some are already destroyed, broken, abandoned, or unnoticed. The statues shown in the film include that of, as mentioned earlier, Chiang Kai-Shek, Yu You-Ren, Wu Feng, Chiang Ching-Kuo (1910–1988), Chiang’s son, and Cheng Cheng-Kung (Koxinga, 1624–1662),13 and the political ones that represent the past rulers of Taiwan in different historical periods, and Buddha, Guanyin,14 Daoist gods as the religious ones, as well as other statues.15 The statues are shown in the film as they are filmed by the documentarians on location and in documentary sequences that appear as part of the film (Figures 1–2).

In addition, FLAT TYRE captures unusual images of the statues. In Figure 3, for example, the film shows a huge statue of the Jade Emperor of Daoism, beside which are the statues of Guanyin and Chiang Kai-Shek. They stand next to a temple, with four flagpoles set in front of the statue of Chiang Kai-Shek. This image appears in the last part of a series of sequences showing a variety of statues of Guanyin which are ubiquitous in Taiwan and conveys an image of the “coexistence” of the political and religious statues mentioned above. When showing this image, the film provides a comment on it with Jianxian’s voice-over: “[…] we Taiwanese really need great figures to protect us!” Perhaps conveying a sense of absurdity or strangeness, this image implies that there seems to be an everlasting spiritual need for “protectors,” be it a religious figure, political one or both, in Taiwanese people.

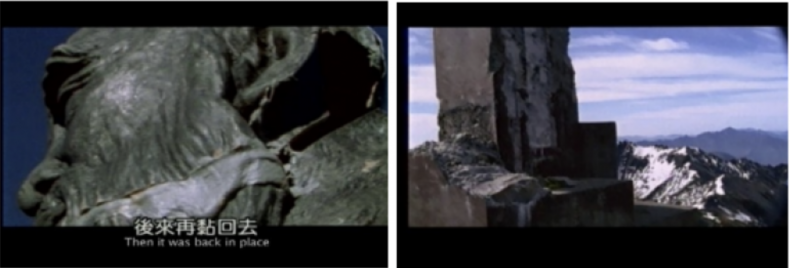

On the other hand, FLAT TYRE uses several visual documents like documentary photographs and footage that represent the historical events that involve the public statues in Taiwan, such as the demolishing of the Yu You-Ren’s bust on Mount Jade and the equestrian statue of Wu Feng in the city of Chiayi. In these cases, the origin of these documents is not specifically indicated in the film, and it is uncertain whether they are archive documents (some of these documents could be works by the director Ming-Chuan Huang himself). However, some of them are used to give a context to the statues recorded by the protagonists. In the case of the bust of Yu You-Ren on Mount Jade, for instance, a few photographs are inserted to show a man who demolishes (or prepares to demolish) the head of the bust (Figures 4–6) and the finally destroyed statue (Figure 7). Holding an indexical function, these photos refer to the incident of destroying the bust. According to a report published in 2007, on November 1, 1995, a few opponents climbed up to the main peak of Mount Jade and cut off the head of the statue. One of the men who demolished the bust was Po-Wen Yeh, a social movement figure in Taiwan. The reason why they destroyed the bust was to “revive the original face of the mountain.” The destroyed head of the bust was discarded at that time but was found and stuck back to the bust later. Yet, in 1996 the bust was found demolished again, and therefore the entire monument was finally replaced by a natural stone engraved with the words “Mt. Jade Main Peak.”16

After showing these photos, the film cuts to a series of sequences with the same bust recorded by Meng and Jianxian accompanied by a voice-over, a dialog between them exchanging memories of shooting the bust. According to the voice-over and the images of the sequences, the viewer learns that what the protagonists recorded are the repaired bust and the remains of the monument after the destruction in 1996. (Figures 8–9). Furthermore, FLAT TYRE presents documentary images (in the diegesis they are recorded and shot by Meng) with the left pedestal of the bust, showing that the pedestal was, surprisingly, once used by unknown prayers for some kind of religious ritual/activity at a point after the 1996 destruction and a man sitting on the pedestal where the destroyed statue was set and chanting incantations (Figures 10–11).

The documentary recordings of this religious event, on the one hand, remind the viewer of the image showing the three religious and political statues standing next to a temple (Figure 3), implying the spiritual need for “protectors” in Taiwanese; on the other hand, these images recontextualize the historical incidents of destroying the bust of Yu You-Ren on Mount Jade in a new context of religion, and that undoubtedly expands the viewer’s memory and imagination of the past events related to the destruction of the monuments to the political figures.

Reflect

By showing Meng who concentratedly assembles and shoots with the Bolex camara in the opening sequence (Figures 12–15), FLAT TYRE adopts a reflexive approach while recording and presenting the statues. This approach and the image of the two documentarians with the camera in the film might recall Dziga Vertov’s MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA (USSR 1929) and the concept of Kino Eye. FLAT TYRE appears to share a similar belief in the task of the movie camera, that is, as Osip Brik has stated, “not to imitate the human eye, but to see and capture what the human eye usually does not see,”17 and also a belief in the work by a cameraman, that is, as what Siegfried Kracauer comments on Vertov’s work in MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA, “again and again penetrates the seemingly self-contained collective realm,”18 as the film emphasizes the camera as an important device for the protagonists to record the statues as historical objects and portrays how the objects are shot by them with the camera.

At the same time, the movie camera can be considered differently, as a pragmatic choice for filming the statues in FLAT TYRE. As shown in the opening sequence, the Bolex camera is chosen as a key instrument by Meng to make his documentary. Introduced in the 1930s and once being “both tool and talisman” for a generation of filmmakers,19 this camera can be approached as a “museum piece” nowadays, as Jianxian jokes about this antique device in the film. However, as Meng responds to Jianxian’s joke, the crucial features of the camera — its mobility and low costs (“it doesn’t need batteries!” as Meng says in the film) — can definitely be useful for Meng, an independent documentarian who does not have enough financial resources but aims to film as many statues placed in different environments and remote sites as possible.20

In this pragmatic view, the film further presents how the protagonists shoot the statues with the camera and use other tools like an old jeep for a filming process. For instance, in the scene that shows the two documentarians’ encounter with an uncompleted statue of Buddha atop a religious building on their way, they decide to film the statue from the moving jeep. Meng drives the jeep and Jianxian first measures the light with a light meter and then leans with his upper body out of the window of the jeep to shoot the statue (Figure 16). Meanwhile, Meng asks Jianxian not to “zoom in.”

The shot therefore goes back and forth between Jianxian (who is filming the statue) and the headless Buddha statue (the filmed object) (Figures 17–21). We can see that the image of the statue is captured from the point of view of Jianxian’s camera, and the size of the image of the statue is changing together with the moving of Jianxian on the running vehicle. In this way, the film clearly shows how a documentary image of the headless Buddha statue is captured and manipulated by the documentarian from his point of view with the filming tools (i.e., the light meter, the camera, and the jeep) and shooting techniques (i.e., no “zoom in” and shooting on the moving vehicle) he uses.

And through the representation of the documentarians’ action of filming the statues, FLAT TYRE further reflects the definition of the filmed images of the statues. In this particular scene of Jianxian’s action of shooting the headless statue of Buddha, for example, the film reflects that what has been shot refers to what is shot from a certain angle in space and in a certain moment in the flow of time; the images of the headless statue of Buddha captured here are far less capable of representing the statue as an object existing in space and time. Nevertheless, the film reminds that what image depicts is hard to describe with words. In one of the scenes, Meng and Ning argue over the way of writing a voice-over script for his documentary: whereas Meng considers that Ning, who is supposed to write the text, should accompany him on location in order to “feel” the statues and the environment, Ning assumes that such a text can be written based on a discussion. In this way, FLAT TYRE emphasizes the function of documentary images as “eye witnesses.” Meanwhile, it reflects on the question of how a cinematic image as historical evidence should be read. In other words, the image can have very different meaning to the ones who witnessed the relevant history and the ones who did not.

Trace

Since the term “trace” became a key concept and method in historiography, things, as Peter Burke indicates, like “manuscripts, printed books, buildings, furniture, the landscape,” as well as those providing images, such as “paintings, statues, engravings, photographs,”21 are all potentially viewed as a significant “vestigium” for historians. As Gustaaf Renier has pointed out, the Latin word “vestigium” refers to “the trace left by the sole of the foot and also the sole of the foot itself,” and thus implies “an intimate relation [that] exists between a trace and that by which it was left.”22 Therefore, as Renier assumes, “[t]o be acquainted with a trace brings us nearer to the event by which it was left […].”23 Along this line of thinking, FLAT TYRE has multiple meanings. First, the film deals with destroyed or abandoned statues. In this sense, it conceptualizes them as traces that are left from original monuments as well as indicates events that lead to their destruction or abandonment. Second, the film documents a number of images of the statues and in doing so preserves them as a kind of trace in audiovisual form. And third, the film demonstrates a continuous cultural practice of “tracing” by depicting the protagonists who trace the above-mentioned statues with the movie camera; as a result, more images and information about the statues, their location, and surroundings, are revealed in the course of the film.

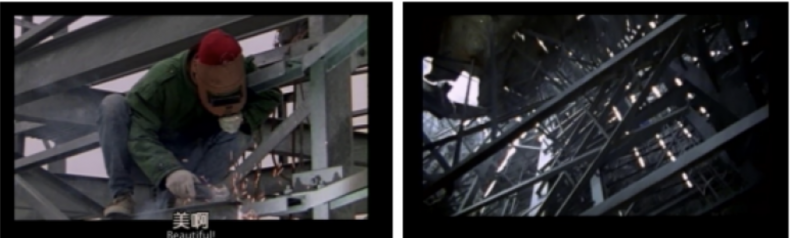

For example, in the scene that shows an abandoned statue of Guanyin as a huge uncompleted building, the film depicts Meng and Jianxian in search of the statue driving to the intended destination. The viewer firstly sees the building located on a desolate riverbank in a rural area (Figure 22).24 It appears that Meng has visited this place for investigation for several times, whereas it is the first time for Jianxian to see this statue on location. The film continues to show the remaining steel structure of the statue in more detail as the protagonists enter the building to see the inside of it (Figure 23). Meng tells his partner that according to his inquiries the construction of this statue has stopped for a long time. Meanwhile, some documentary video fragments showing workers on the building are inserted into the film (Figure 24). The content of these fragments refers to the construction of the statue in the past. And then Meng proposes to climb up to the top of the building to find out more details of this abandoned statue as Jianxian is amazed at the space constituted by the steel structure and thinking how to film it (Figure 25). While they are ascending to the top, more parts of the building are shown to the viewer (Figure 26), and a few more video fragments are again inserted into the film. These video fragments present the exterior of the statue from the top to the bottom and reveal that the head of the Guanyin statue is unfinished and a smaller but finished Guanyin statue is on the base of the building (Figure 27). As the protagonists arrive at the roof, they have a dialog about the bankrupt of the construction company that results in the incompletion of the building. Besides, while the dialog goes, the viewer can see through the steel structure the surrounding area with lush greenery that contrasts with the decay of the steel structure (Figures 28–29).

In this process of tracing and revealing (the past of) this particular statue, the film further raises curiosity in the viewer. For example, in the dialog between the protagonists at the roof of the statue, Meng asks a question: “Can politics and documentary be kept separate?” To this question (which in fact is a big question about politics and art) Jianxian replies humorously: “[…] who planned this Guanyin were bankrupt and fled to China? If so…in one sense this is a political Guanyin. And that makes this a political documentary!” What Jianxian says sounds bewildering and ambiguous, but in this way, and with all the images and video fragments shown previously, the film prompts broader questions of what does this abandoned statue exactly represent, what history does the statue represent in terms of Taiwan’s politics, economics, and religion, and what is the role of cinema in tracing the history?25 In this sense, the film implies that the images of the statues captured in this work can be regarded as an alternative approach to triggering historical thinking or as a kind of “raw material” for historical exploration in the context of the reconstruction of the history of Taiwan in the post-martial law era, and more importantly the film, as what the protagonists have been doing in the film symbolizes, encourages more practices of tracing, as well as documenting, those abandoned, unnoticed, forgotten, and marginalized as historical traces. On the other hand, how can the statues traced by the protagonists be interpreted in regard to the historical issues of Taiwan? What follows is a discussion on this question.

Interpret

Drawing on Roland Barthes, Yu-Chin Huang points out that the statue of the “great man” Chiang Kai-Shek was once taken as a material for creating mythological discourse. However, when the discourse which surrounds the statue is faded, the statue is but a lifeless cold stone.26 Yet, Yu-Chin Huang emphasizes the importance of exploring and interpreting the meaning of the statue as a historical artifact in the contemporary context of Taiwan.27 From this viewpoint, FLAT TYRE on the one hand aims to trace those destroyed or abandoned statues and on the other hand tries to provide a historical interpretation with the images shown in the film.

Rather than interpreting the destroyed or abandoned statues as an imagery connected to the traumatic historical experience of the Taiwanese, the film tries to transform the ruined into a “battlefield” of historical interpretation and invites more radical reflections on the historical consciousness of the Taiwanese. For instance, in the film Meng and Jianxian encounter a mysterious man on their way to filming their documentary. The man is standing beside a damaged car, and it seems that a car crash has just happened. Meng gets off the jeep to check the situation, but the man has been silent when Meng shows his concerns. Meng invites the man to join their ride to the foot of the mountain. However, when Meng wants to help the man to get into the jeep, he suddenly pushes Meng into the jeep and then shuts the door of the vehicle. Instead of sitting in the jeep, he stands on the outside board of the car and grasps a handle on the top with one hand. By waving the other hand the man wants Jianxian to start the car. Shocked by this unusual behavior, Meng and Jianxian become curious. When they arrive at the foot of the mountain and approach the rugged coastline, it starts to rain heavily, so that they decide to stay overnight at the seashore. Then Meng asks the man: “Where are you from?” The man answers: “Very, very far from here.” This answer makes Meng bewildered so he continues to ask: “Where?” But the man does not reply. And then Jianxian comes to talk to Meng:

Jianxian: You’re such a tough guy. Why not film those buckers of ‘50s...from the “Recapture the Mainland” Campaign?

Meng: Why would I want to film buckers?

Jianxian: They’d fit right into your documentary. They’re like the statues...Stiff and lifeless! Plus, they have that “historical significance” you love!

Meng: No, it’s different. Nobody’s really looked at those statues before. That’s why they’re “alive”...and worth filming!

Jianxian: Let’s face it... Taiwan is so close to China. Because the KMT Nationalists retreated here...your whole life is overshadowed by them...and their Communist enemies.

Meng: No, it’s only the KMT which overshadow us. I don’t see any shadow of the Chinese Civil War.

Jianxian: What’s the difference? The Civil War is a historical fact!

Meng: Historical fact? Everything we were taught about China...was from the KMT’s perspective. That shaped our whole lives. It’ll shape our children’s too. Where’s the Communist influence? There hasn’t been no one connecting our lives to Communist?

Jianxian: Okay, but it’s only since martial law ended...and Chiang Kai-Shek and his son died...that all these religious statues have appeared. Those damn great icons of concrete and steel...Aren’t they “political” too?

In this conversation, the film reflects on Taiwanese’s historical consciousness which is formed and influenced by the KMT’s historical education since the government retreated from Mainland China to Taiwan in 1949. The historical education is based on a “nationalist historiography” that, according to Albert Tzeng, aims to glorify the nation and is constructed in opposition to an enemy.28 Therefore, the historical education aimed at glorifying the past of China and strengthening the people’s hostile attitude towards the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the enemy of the KMT, as well as mobilizing the people to defend the island by promoting this Chinese nationalist identity. In other words, the Taiwanese were being educated by the KMT which promoted a “history” that does not reflect their actual life on the island. The film indicates the problem of the historical education and suggests a more critical attitude toward history. By defining the statues as “live” objects to be filmed, FLAT TYRE appears to expect a historical interpretation that can go beyond the existing historical boundaries set by the authority and draws attention to the actual space, time, and materiality as elements of history encountered by the Taiwanese.

Silence?

When Meng and Jianxian are talking to each other, the mysterious man is silently sitting beside them. When Meng and Jianxian start to talk about the 1950s’ buckers against the background of the “Recapture the Mainland Campaign,” the man closes his eyes and sits like that during their conversation (Figure 30). When Meng says about the filmed statues (“No, it’s different. Nobody really looked at those statues before. That’s why they’re ‘alive’ [...] and worth being filmed!”), the camera cuts to a head-and-shoulders shot of the mysterious man, who is sitting as a “live statue” (Figure 31). And then the camera zooms out from the shot a bit and pans from the man to Meng and Jianxian who are still talking to each other. When the conversation ends, the image jumps to a medium shot of the man again (Figure 32) and then a close-up that clearly shows the outline of the man’s face and the meditational expression of him (Figure 33).

Ending at the close-up of the mysterious man, the film raises curiosity and a set of questions: Why does the man behave himself wordlessly? What does the man think when he closes his eyes? Does he listen to the conversation between Meng and Jianxian? What does the image of the mysterious man mean? Apparently, the silent man contrasts the intense conversation between Meng and Jianxian. The man’s distant attitude towards the conversation on the history of Taiwan implies an attitude of anti-interpretation, questioning whether the history discussed by Meng and Jianxian as “Taiwanese” refers to “our history.” Sitting silently like a “live statue” the man symbolizes the real statues to be filmed and interpreted. At the same time, the expression powerfully reminds of the necessity of self-reflection in terms of any historical interpretation.

Conclusion

Walter Benjamin stated that “[i]n the ruin […] history does not assume the form of the process of an eternal life so much as that of irresistible decay.”29 However, FLAT TYRE conveys a message that the destroyed or abandoned is “alive” to the ones who attempt to explore history and thus worthy of being traced and filmed. The film was also discussed as a text with regard to representing the mythologies of politics and religion of Taiwan.30 However, as this article indicates, besides showing the political and religious statues, the film suggests a meta-perspective to reflect on the definition of the filmed images of the statues as historical objects and the meaning of documenting the objects by means of cinema. With the two documentarians who search and film the political and religious statues, the film tries to seek an alternative and an open perspective to interpret the history of Taiwan in the post-martial law context of the island.

This article suggests the first step to explore the images of the statues recorded in FLAT TYRE and the meaning of the images as historical traces in the film. The cinematic images of the destroyed statues represent the drastic political and historical changes of the island. Meanwhile, the images imply the impossibility to show a complete history and the boundaries of writing a history. At the end of the film, the jeep driven by Meng and Jianxian has a flat tyre, but they pursue their journey of tracing history with their camera. More images await to be shot, and the images shot await further explorations by the audience.

- 1This article is part of my PhD research “Beyond Sadness: Historical Films in the Post-martial Law Period of Taiwan (1987–2017)” supervised by Frank Kessler and Judith Keilbach at the Institute for Cultural Inquiry, Utrecht University, the Netherlands. A previous version of the article was presented at the conference “Truth and Imagination: The Metaphors of Cultures and Their Refashioning and Interpretations” held by the Department of Drama and Theatre, National Taiwan University in Taipei on October 27–28, 2018. I would like to thank the respondent Wei-Chih Wang (Institute of Taiwan Literature, National Tsing Hua University, Taiwan) to my paper at the conference. My thanks also go to the following people for their valuable contributions to this article: the reviewers for suggestions, Clara Pafort-Overduin (Department of Media and Culture Studies, Utrecht University) for comments, Levon Kwok for assistance with editing the draft of the article and translation, and Tatiana Astafeva at Research in Film and History for copy editing.

- 2Erik Bordeleau, “Un drame onirique de la présence: Quelques notes autour de Huang Ming-Chuan,” in 如夢似劇 : 黃明川的電影與神話 [Like a Dream, Like a Drama: Huang Ming-Chuan’s Films and Mythology] (Taipei: ARTouch, 2013), 90.

- 3Martial law was imposed by the Kuomintang (the KMT, also known as the Chinese Nationalist Party) government on Taiwan in 1949. It lasted thirty-eight years and is considered “the longest period of martial law in the world during the twentieth century.” Wan-Yao Chou, A New Illustrated History of Taiwan, trans. Carole Plackitt and Tim Casey (Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc., 2015), 333.

- 4According to an estimate, approx. 4.500 statues of Chiang were erected in Taiwan after Chiang’s death in 1975 and until the mid-1980s. Built in various sizes and forms, the statues were installed in the schools, military premises, parks, and other public spaces. After 1987 the statues were constantly removed, partly destroyed, or damaged by opponents. Cf. Joseph Roe Allen, Taipei: City of Displacements (Seattle, London: University of Washington Press, 2012), 150–151; Yu-Chin Huang, “台灣偉人塑像的 興與衰 : 以 1949 到 1985 年的《中央日報》為例” [The Rise and Fall of the Statues of the Great Men in Taiwan: Taking Central Daily News, from 1949 to 1985, as an Example], in 近 代 肖 像 意 義 的 論 辯 / Contesting the Meanings of Modern Portraiture, ed. Jui-Chi Liu (Taipei: Yuan-Liou Publishing Co., Ltd., 2012), 202–243; Helen Leavey, “Taiwan Divided over Chiang’s Memory,” BBC News, March 11, 2003, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/2836725.stm.

- 5The Control Yuan is one of the five “Yuans,” literally “courts,” of the constitutional government of the Republic of China (Taiwan). The five Yuans, including the Legislative Yuan, the Executive Yuan, the Judicial Yuan, the Control Yuan, and the Examination Yuan, are the core branches of the government. The Control Yuan serves as the highest investigatory branch of the government and holds the power to impeach or censure a government official and to audit the annual governmental budget. Cf. The official website of the Control Yuan https://www.cy.gov.tw/EN/; Wikipedia entry: Control Yuan https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Control_Yuan

- 6Cf. Cheung Han, “Taiwan in Time: The Drastic Downfall of Wu Feng,” Taipei Times, September 10, 2017, https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2017/09/10/2003678150.

- 7Cf. Yu-Chin Huang, “台灣偉人塑像的興與衰” [The Rise and Fall of the Statues of the Great Men in Taiwan], 236–237.

- 8Cf. Chung-Lan Cheng, “台灣 : 228 前夕依舊尷尬的蔣介石銅像” [Taiwan: The Still Embarrassing Statue of Chiang Kai-Shek on the Eve of the February 28 Incident], BBC News/Zhongwen, February 27, 2016, https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/trad/taiwan_letters/2016/02/160227_taiwan_228_chiang_statues; “台灣「政治線民」風波及移除蔣介石銅像爭議:「轉型正義」如 何 面 對 更 多 挑 戰 ” [The Dispute over “Political Informer” and the Controversy about Removing the Statue of Chiang Kai-Shek in Taiwan: How Does the “Transitional Justice” Face More Challenges], BBC News/Zhongwen, November 22, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/trad/chinese-news-59339027.

- 9Pei-Lin Wan, “ 懷 抱 十 年 文 化 紀 錄 的 大 夢 ” [A Ten-Year Big Dream of Documenting the Culture], in 神話三部曲 : 西部來的人﹑寶島大夢﹑破輪胎 / Huang Mingchuan’s Trilogy: THE MAN FROM ISLAND WEST, BODO, FLAT TYRE (Taipei: Formosa Filmedia Co., 2011), 84.

- 10According to my research, films that deal with decaying or destroyed artifacts and memorials were generally documentaries, such as Alain Resnais and Chris Marker’s STATUES ALSO DIE (FR 1953) and Laura Mulvey and Mark Lewis’s DISGRACED MONUMENTS (UK 1994). These films do not suggest specifically a meta-perspective on the practice of documenting the artifacts and memorials.

- 11Song-Yong Sing, “塵埃迷濛了你的眼:黃明川、陳芯宜與臺灣電影中的墟形 魅景”/ “Dust Gets in Your Eyes: Ming-Chuan Huang, Singing Chen and Ruinscapes as Phantom Scenes in Taiwan Cinema,” Journal of Art Studies 13 (2013): 141–183.

- 12Jow-Jiun Gong, “去頭風景、感應影像 : 從「神話三部曲」到〈流浪神狗人〉 ” [The Scenery of the Acephalous and the Image of Affection: From “Trilogy of Mythology” to GOD MAN DOG], in 如夢似劇 : 黃明川的電影與神話 [Like a Dream, Like a Drama: Huang Mingchuan’s Films and Mythology] (Taipei: ARTouch, 2013), 152.

- 13Cheng Cheng-Kung (Koxinga) was a Chinese loyalist of the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). He resisted the Qing Dynasty which conquered the Ming around the mid-seventeenth century. In 1662, Cheng Cheng-Kung defeated the Dutch who ruled Taiwan at that time and then used the island as “a base from which to oppose the Ch’ing [Qing] and restore the Ming Dynasty.” Wan-Yao Chou, A New Illustrated History of Taiwan, trans. Carole Plackitt and Tim Casey (Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc., 2015), 68.

- 14Guanyin refers to the Buddhist bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara. In the context of Chinese Buddhism, Guanyin is viewed as the “goddess of Mercy” and widely worshipped in Taiwan. Cf. Wikipedia entry: Guanyin, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guanyin.

- 15Besides the statues of political and religious figures, the film also captures some statues which are located in remote places or unknown courtyards, representing traditional stories.

- 16Yen-Ling Chiu, “玉山于右任像斷頭 元凶說始末” [The Beheading of the Statue of Yu You-Ren on Mount Jade, an Explanation from the Culprit], The Liberty Times, February 13, 2007, https://news.ltn.com.tw/news/focus/paper/116225.

- 17Osip Brik, “What the Eye Does Not See,” in Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties, ed. Yuri Tsivian (Udine: La Cineteca del Friuli – Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2004), 265.

- 18Siegfried Kracauer, “Man with a Movie Camera,” in Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties, ed. Yuri Tsivian (Udine: La Cineteca del Friuli – Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2004), 358.

- 19Daniel Barnett, Movement as Meaning in Experimental Film (Amsterdam, New York: Editions Rodopi B.V., 2008), 116.

- 20The reasons here echo Daniel Barnett’s mention of the popularity of the Bolex cameras in the 1960s and 1970s, as he says: “These cameras were relatively common and relatively inexpensive and their availability meant that films could be produced by individual artists with a financial and material economy typical of the status of poets and painters, allowing a cultural movement to develop where audience acceptance was far less of a consideration than the kind of visual experimentation afforded by this remarkable tool.” Daniel Barnett, Movement as Meaning, 193.

- 21Peter Burke, Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence (London: Reaktion Books, Ltd., 2001), 13.

- 22Gustaaf Renier, History: Its Purpose and Method (London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd, 1950), 97.

- 23Ibid.

- 24According to an interview with the director Ming-Chuan Huang, the statue is located in Miaoli, a county in north-western Taiwan. FLAT TYRE DVD.

- 25In this regard, FLAT TYRE resonates with the practice of documentary photography in Taiwan. According to Shih-Ming Pai, the photography has begun to question the core of a Taiwanese identity since the 1980s. Based on long-term field research, the photography attempted to reconstruct the image of historical materiality and memory of Taiwan. In the 1990s, the photography, as Pai points out, was further transformed into a “battlefield of discourse” in which issues with regard to “the reformulation of history,” “opposition to otherness,” and “the establishment of cultural subjectivity and identity” are critically examined from a postcolonial perspective. Shih-Ming Pai, “記憶、被記憶與再記憶化的視覺形構: 臺灣近現代攝影的歷史物質性與影像敘事 / Remembering, Being Remembered and Re-rememberization: The Historical Materiality and Image Narrative of Modern Photography in Taiwan,” The Sculpture Research Semiyearly 12 (2014), 55, 59–60. By depicting the protagonists as documentarians who put long-term efforts to trace, investigate, and record the public statues, FLAT TYRE echoes the above-mentioned practice of the documentary photography and, at the same time, intervenes the relevant discourse with the documentary images of the statues in the film.

- 26Yu-Chin Huang, “台灣偉人塑像的興與衰” [The Rise and Fall of the Statues of the Great Men in Taiwan], 208.

- 27Yu-Chin Huang, “我和我的偉⼈塑像:⼀段教科書不會記載但私以為更有意義 的記憶書寫” [The Statues of the Great Men and Me: A Memory That Will Not Be Recorded in Textbooks But Is Significant to Me], Thinking Taiwan, 8 March 2017, https://www.thinkingtaiwan.com/content/6104.

- 28Albert Tzeng, “我們為何學歷史?教育史學格局、地理框架、與課綱的政治 ” [Why Should We Study History? The Vision for the Historiography of Education, the Framework of Geography, and the Politics of Curriculum], Opinion, February 6, 2014, https://opinion.cw.com.tw/blog/profile/220/article/978.

- 29Walter Benjamin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osborne (New York: Verso, 2003), 177–178.

- 30Te-Pen Chang, “Huang Mingchuan’s Trilogy: The Making of an Archetype,” translated by David J. Toman, in 神話三部曲:西部來的人﹑寶島大夢﹑破輪胎 / Huang Mingchuan’s Trilogy: THE MAN FROM ISLAND WEST, BODO, FLAT TYRE, 139-152. Taipei: Formosa Filmedia Co., 2011.

Allen, Joseph Roe. Taipei: City of Displacements. Seattle, London: University of Washington Press, 2012.

Barnett, Daniel. Movement as Meaning in Experimental Film. Amsterdam, New York: Editions Rodopi B.V., 2008.

Benjamin, Walter. The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Translated by John Osborne. New York: Verso, 2003.

Bordeleau, Erik. “Un drame onirique de la présence: quelques notes autour de Huang Ming-Chuan.” In 如夢似劇: 黃明川的電影與神話 [Like Dreams, Like Drama: Huang Ming-Chuan’s Films and Mythology], 80–95. Taipei: ARTouch, 2013.

Burke, Peter. Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence. London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2001.

Brik, Osip. “What the Eye Does Not See.” In Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties, edited by Yuri Tsivian, 265–266. Udine: La Cineteca del Friuli – Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2004.

Chang, Te-Pen. “Huang Mingchuan’s Trilogy: The Making of an Archetype,” translated by David J. Toman. In 神話三部曲 :西部來的人 ﹑寶島大夢 ﹑破輪胎 / Huang Mingchuan’s Trilogy: THE MAN FROM ISLAND WEST, BODO, FLAT TYRE, 139–152. Taipei: Formosa Filmedia Co., 2011.

Cheng, Chung-Lan. “台灣 : 228 前夕依舊尷尬的蔣介石銅像” [Taiwan: The Still Embarrassing Statue of Chiang Kai-Shek on the Eve of the February 28 Incident]. BBC News/Zhongwen, February 27, 2016. https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/trad/taiwan_letters/2016/02/160227_taiwan_228_chiang_statues.

Chiu, Yen-Ling. “玉山于右任像斷頭 元凶說始末” [The Beheading of the Statue of Yu You-Ren on Mount Jade, an Explanation from the Culprit]. The Liberty Times, February 13, 2007. https://news.ltn.com.tw/news/focus/paper/116225.

Chou, Wan-Yao. A New Illustrated History of Taiwan. Translated by Carole Plackitt and Tim Casey. Taipei: SMC Publishing Inc., 2015.

Gong, Jow-Jiun. “去頭風景、感應影像 : 從「神話三部曲」到〈流浪神狗人〉” [The Scenery of the Acephalous and the Image of Affection: From “Trilogy of Mythology”to GOD MAN DOG]. In 如夢似劇:黃明川的電影與神話 [Like a Dream, Like a Drama: Huang Ming-Chuan’s Films and Mythology], 129–153. Taipei: ARTouch, 2013.

Han, Cheung. “Taiwan in Time: The Drastic Downfall of Wu Feng.” Taipei Times, September 10, 2017. https://www.taipeitimes.com/News/feat/archives/2017/09/10/2003678150.

Huang, Yu-Chin. “台灣偉人塑像的興與衰: 以 1949 到 1985 年的中央日報為例” [The Rise and Fall of the Statues of the Great Men in Taiwan: Taking Central Daily News, from 1949 to 1985, as an Example]. In Contesting the Meanings of Modern Portraiture, edited by Jui-Chi Liu, 202–243. Taipei: Yuan-Liou Publishing Co., Ltd., 2012.

---. “我和我的偉⼈塑像: ⼀段教科書不會記載但私以為更有意義的記憶書寫” [The Statues of the Great Men and Me: A Memory That Will Not Be Recorded in Textbooks But Is Significant to Me]. Thinking Taiwan, March 8, 2017. https://www.thinkingtaiwan.com/content/6104.

Kracauer, Siegfried. “Man with a Movie Camera.” In Lines of Resistance: Dziga Vertov and the Twenties, edited by Yuri Tsivian, 355–359. Udine: La Cineteca del Friuli – Le Giornate del Cinema Muto, 2004.

Leavey, Helen. “Taiwan Divided over Chiang's Memory.” BBC News, March 11, 2003. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/2836725.stm.

Pai, Shih-Ming. “記憶、被記憶與再記憶化的視覺形構:臺灣近現代攝影的歷史 物 質 性 與 影 像 敘 事 ” / “Remembering, Being Remembered and Rerememberization: The Historical Materiality and Image Narrative of Modern Photography in Taiwan.” The Sculpture Research Semiyearly 12 (2014): 53–84.

Renier, Gustaaf. History: Its Purpose and Method. London: George Allen & Unwin Ltd. 1950.

Sing, Song-Yong. “塵埃迷濛了你的眼:黃明川、陳芯宜與臺灣電影中的墟形魅 ” / “Dust Gets in Your Eyes: Ming-Chuan Huang, Singing Chen and Ruinscapes as Phantom Scenes in Taiwan Cinema.” Journal of Art Studies 13 (2013): 141–183.

Tzeng, Albert. “我們為何學歷史?教育史學格局、地理框架、與課綱的政治” [Why Should We Study History? The Vision for the Historiography of Education, the Framework of Geography, and the Politics of Curriculum]. Opinion, February 6, 2014. https://opinion.cw.com.tw/blog/profile/220/article/978.

Unknown, “台灣「政治線民」風波及移除蔣介石銅像爭議 : 「轉型正義」如何 面 對 更 多 挑 戰 ” [The Dispute over “Political Informer” and the Controversy about Removing the Statue of Chiang Kai-Shek in Taiwan: How Does the “Transitional Justice” Face More Challenges]. BBC News/Zhongwen, November 22, 2021. https://www.bbc.com/zhongwen/trad/chinese-news-59339027.

Wan, Pei-Lin. “ 懷 抱 十 年 文 化 紀 錄 的 大 夢 ” [The Ten-Year Big Dream of Documenting the Culture]. In 神話三部曲 : 西部來的人 ﹑寶島大夢﹑破輪胎 / Huang Mingchuan’s Trilogy: THE MAN FROM ISLAND WEST, BODO, FLAT TYRE, 79–87. Taipei: Formosa Filmedia Co., 2011.