Work and Life

Toward a New Type of Biography

Table of Contents

Secret Publics

Digital Digging

Movie Theatre(s) of Memory

Filmography of the Genocide

Exacting the Trace

Destroyed Statues, a Bolex 16 mm Camera, and an Old Jeep

“…will you show that on your British television?” ACCEPTABLE LEVELS as Historiographic Metafiction

Work and Life

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Basaldella, Dennis. “Work and Life: Toward a New Type of Biography.” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces, no. 4 (February 2022): 1–12. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18105.

Introduction

The new film history approach proposed by Thomas Elsaesser and other film scholars shifted the focus of film studies. On this approach, film history is no longer regarded as a linear and causal chain of events, but as a tangle of crisscrossing branches. Moreover, film ceases to be a remote, detached art object produced by a single person’s work—the product of a solitary creative struggle by the director or artist; rather, it is seen as the result of a network of people working together. Another aspect, and the main point this article shall focus on, is that the new film history approach is empirically based; films themselves do not serve as the only source, and other archival sources can yield a complex, multilayered new perspective on film, television, and their history.

Based on a case study of the work and legacy of freelance GDR (German Democratic Republic) filmmaker Horst Klein,1 this article will show that biographical information can enrich historical studies of film and television and lead to a better understanding of work in the film and television industry. Here, the biographical information takes the form of traces that allow us to discover a previously neglected chapter of film history in the former socialist country. These traces also shed light on an often overlooked aspect of film production: filmmakers’ personal and emotional lives.

Before the main discussion gets underway, the first section introduces Horst Klein, giving a brief outline of his biography and explaining why his career is so important and valuable for a closer examination of the connection between work and life. This section also sets out the central question that the remainder of the article will seek to answer. The second section gives a brief introduction to the topic of freelance work in the GDR film industry and the freelancers involved. The third section takes a closer look at the relevant biographical or, to be more precise, autobiographical sources, so as to gain a better understanding of the quality and type of these sources. Especially in the case of autobiographical sources, it is important to know who the intended audience was and what effect (if any) this had on the content. It is also important to understand the context in which these sources were produced. The fourth section discusses Klein’s professional ethics and why he took certain decisions during his career. A closer look at various events over the course of his life and career reveals a pattern to the subjects he chose to work on. It is therefore important to analyze where this ethics came from and what effect it had on his work. The fifth and sixth sections examine a number of different examples. While the examples in the fifth section show how biographical events influenced Klein’s working life, the sixth section highlights cases where Klein’s work had an impact on film and television work in the GDR. These last examples are particularly interesting, since the diaries (biographical sources) are the only traces to give an indication of this impact.

Case Study and Central Question

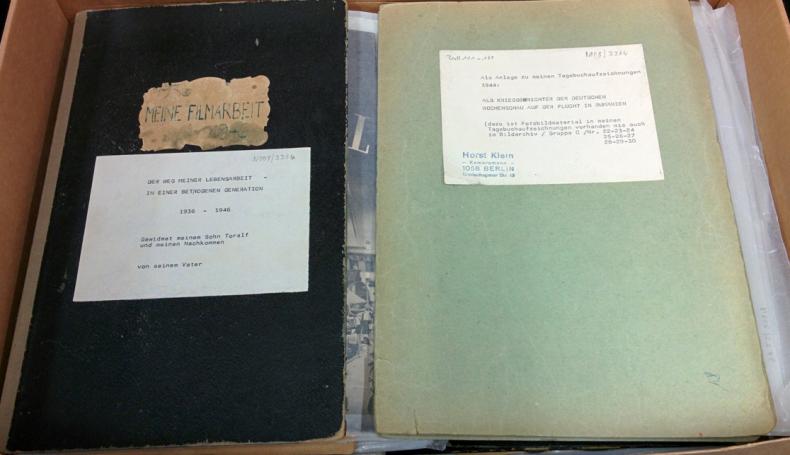

Horst Klein (1920–1994), whose writings, films, and other documents are preserved in the archive of the Filmmuseum Potsdam (Germany), is the central figure in the present case study.

Klein was born in Luckenwalde, a town about seventy-six kilometers south of Berlin in the modern state of Brandenburg, on November 1, 1920. It was there that he took the first steps in his future film career when, at the age of seventeen, he began making amateur films. In 1941, he founded KLEIFAG (presumably an acronym for Klein Film-Arbeitsgemeinschaft, or “Klein film association”). Later, in 1942, he chose to work as a field camera operator for the Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops. When the war ended in 1945, he resumed his film career in the Soviet occupation zone. After a short period as camera assistant and permanent employee at the state-owned film studio DEFA (Deutsche Film-Aktiengesellschaft), he embarked on his freelance career, working as a newsreel camera operator for the MGM and NBC offices in West Berlin. After about five years of illicitly working for the American newsreels as a GDR citizen, from 1953 onward his life and activities were mainly centered on the East German state. He worked for many different political institutions, in particular the fledgling state television broadcaster, DFF (Deutscher Fernsehfunk). In the following years, he and his colleagues became a central part of the television network’s production process. His career lasted until about 1990, when he completed his final commission. He dedicated his final years to his legacy, and until his death on January 3, 1994, was actively involved in the process of relocating his writings, films, and other documents to Filmmuseum Potsdam. Across these four decades, Klein completed almost 900 nonfiction commissions for various cultural and political institutions in the Soviet occupation zone (1945–1949) and GDR (1949–1990), making him one of the most productive freelance filmmakers in the country.

A key element to understanding Klein’s work and its value are the 1,827 pages of his work diaries, which are held in the archives in Potsdam. They contain entries from between 1936 and 1994 and thus span the whole period of the Soviet occupation zone’s and the GDR’s existence. Although these diaries are just one part of the collection in Potsdam, they are a unique source, since there is no other official source documenting the work of freelance filmmakers in the GDR in such rich detail.

Viewed through the lens of the new film history approach, the central question is whether audiovisual traces like these diaries can open up a new perspective on film and television history. This article will argue that, in virtue of their form, these diaries (discussed in more detail in the following sections) are able to give a unique inside view into the work of a freelancer in the GDR. It will do so by examining three different aspects of Klein’s career: his life in relation to the film production processes; historical and personal circumstances and influences; and the impact of Klein’s work on the various cultural and political institutions for which he worked. This approach treats his work and his personal life as two parallel strands of equal importance, with biographical and nonbiographical elements constantly interacting and forming a kind of network. This inside view not only gives a new perspective on film and television history, but also a unique insight into Klein’s personal life and thought. These two aspects give a complete picture of his work and career, and will help us to better understand how he was able to maintain his productivity throughout all those years. They also help to shed new light on the relation between work and life.

Freelance Work in the GDR

Before addressing the issues raised in the previous section, we first need to ask what “freelance” means in the GDR context. Although freelance work did not form part of the official work collective politics in the GDR, freelance filmmakers had a notable impact on the country’s film and television production. Unlike permanent employees, freelance filmmakers usually worked together in small groups, production collectives, or alone, using their own equipment to complete commissions (usually on nonfiction topics) for one or more employers.

However, it should be stressed that the concept of autonomous production units was not entirely unprecedented in the socialist system. As Petr Szczepanik points out in his study of socialist production culture, various such units existed in the Soviet Bloc between the 1940s and 1970s. Depending on the political circumstances of their time, they worked more or less autonomously within the production system of various socialist countries.2 In the GDR context, DEFA’s Künstlerische Arbeitsgruppen (KAGs, “artistic working groups”) were similar to freelancers, as they formed a sort of artistic production unit inside the bigger production system of the state-owned film studio and were in charge of the various stages of the production process during the shooting of a film.3

But although these groups did have similarities to freelancers, there was a substantial difference: The KAGs and other groups were integrated into the production system’s structures and had work delegated to them, while in the case of freelancers the work was outsourced externally. In other words, freelancers became part of the employer’s production process, but always remained an autonomous group outside the structures of the employer’s production system. Furthermore, while for the KAGs the politically and ideologically important stage of script development was closely monitored and supervised,4 the freelancers managed this stage on their own too.

Although this last aspect underscores that freelancers had more freedom than the other groups involved in film production, is should be remembered that they were still financially dependent on their employers, and so it was also in their own interest to comply with political requirements. Although the research on Klein’s work did not uncover any source comparing the costs of film productions made by permanent employees versus those made by freelancers (and hence showing the advantages or disadvantages of using one rather than the other), the numbers of productions that were externally commissioned do suggest that (as will be demonstrated later) employers like DFF benefited from outsourcing work to freelancers.

However, the freelancers’ strength was also their weakness. The fact that freelancers usually operated in small production units with their own equipment outside of the firmly structured production system allowed them to work quickly and efficiently. By doing so, they filled a gap that the inhouse production structure could not. So freelancers were more than welcome when employers needed to complete film productions quickly, efficiently, and (presumably) at a lower cost. But their small production resources made bigger productions very difficult and sometimes impossible for freelancers to complete on their own, as one longer commission that Klein worked on between 1961 and 1963 proves.5

Previous studies of GDR film history have paid little attention to freelance filmmakers. By contrast with the new film history approach mentioned in the introduction, these studies have primarily focused on big institutions such as DEFA or the state television broadcaster DFF, or on famous directors and figures from the GDR film industry. Consequently, this research has neglected the work of alternative film production in East Germany and presented the GDR film and television industry as a monolithic structure, solely dominated by a few big institutions. My recent book Ein Leben für den Film (2020) takes a closer look at this largely ignored aspect of GDR film production, while the present article explores how Klein and his diaries help open up a new, alternative view on GDR film history.

(Auto)biographical Sources as Traces

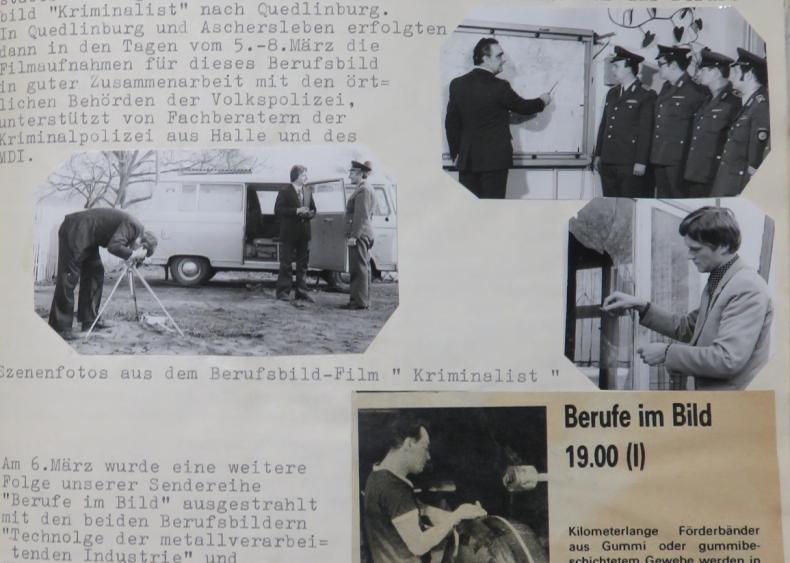

As already mentioned, the 1,827 A4 pages of Klein’s diaries are a unique source for historical research on GDR film, in particular because no other GDR freelancer kept such detailed and extensive work diaries, and because they are far more than just a collection of texts: They combine text and images, including production documents, collected newspaper articles, and set photographs that give a detailed inside view into the work and production processes of a freelancer and freelance production collectives.

Furthermore, since the barrier between work and life for freelancers is much more fluid than it is for permanent employees, a study of freelance work will only be complete if it acknowledges that personal life always has an impact on such work and vice versa. As discussed in detail below, Klein’s diaries give an account not just of his work but also of his personal life, which was so strongly connected to his job that the two cannot be considered in isolation.

These autobiographical sources are unique because they help give a better overall understanding of the work of a freelancer in the GDR, and hence of the neglected topic of GDR freelance filmmakers in general. However, it is important to be aware that the diaries in their present form are not the originals. There is clear evidence in the diaries that there must have been an original version, probably handwritten, which the present diaries are based on. Between 1990 and 1994, the about five years when he dedicated himself to his legacy, Klein began to “retype” and illustrate his notes and diaries. Unfortunately, the original versions (if they did indeed exist in the first place) have not been preserved and so it is not possible to definitively prove this hypothesis. It is possible that some information or facts may have been modified during the reorganizing process between 1990 and 1994, with the aim of presenting a more positive view of certain events or of Klein himself. However, the amount of information and above all the rich detail in which certain events are described in the diaries suggest that there was no substantial alteration of the diaries’ content.6

It is also important to understand that the diaries were not just written to compile information and document events that occurred during these forty years of work. Klein wrote them with the aim of leaving a legacy for future generations, and more specifically for his children. A closer look at the diaries from the early years shows that they are not addressed to any particular person. This changed with the births of his first daughter, Christiane, in 1962, and his second daughter, Marion, in 1966; Klein’s subsequent diaries were addressed to them. The best evidence for this is the photo collages on the first pages of the diaries from this period, showing Klein, his first wife, and his daughters. However, after the divorce in 1969, the addressee changed again, this time to his son Toralf from his second marriage. Between 1990 and 1994, when the GDR ceased to exist and circumstances changed, it is notable that Klein’s diary entries increasingly focused on documenting the changes that occurred in the country during the years after the fall of the wall and reunification.7

Biographical and autobiographical sources are, to be sure, not new to the field of historical research. Indeed, not only is their use familiar, but also raises certain problems that merit a critical discussion. The first and central question is whether the information presented in the diaries is factually accurate, whether it has been altered, and whether the events really happened the way they are described, especially given the clear evidence that the diaries in their present form are not the originals but “retyped” and restructured versions of them. As already mentioned, the extensive and richly detailed description of certain events and facts suggests that the entries must be grounded in reality. It is still possible that Klein may have altered descriptions to present the addressees with a more palatable, positive version of his life, but the account of the unpleasant process of the divorce, as mentioned above,8 does suggest that Klein was determined to present the whole unvarnished truth.

Nonetheless, it is more than usually important to establish the accuracy of what Klein says about his work. The only way to verify these claims is by comparing them with other, more reliable sources such as official documents in other archives. During the research, it was possible to find evidence of almost all the events and film productions discussed in Klein’s diaries and to double-check his accounts of them. However, there is no evidence outside the diaries for certain events that were key formative influences in Klein’s life, such as when he was detained for filming the uprising in East Germany from June 16 to 17, 1953 (on which more later). In the absence of corroborating evidence, it remains unclear whether Klein really was present at the uprising and whether the personal events took place the way he describes in his diary. This last example in particular underscores that these autobiographical sources should primarily be viewed as audiovisual traces and clues that can lead to a better understanding of Klein’s work and life, but can also lead to false assumptions if they are read the wrong way and taken as the full truth. However, as the following sections will show, considering biographical and personal information can add a new layer to historical research.

Professional Ethics and the Connection between Life and Work

Because of the special situation of the diaries, it is even more important to understand the person behind the text and the reasons for the strong connection between his life and work. When we examine a source of this kind, some decisions taken by the person in question might seem to be logical, but others may seem strange and wrong, especially from today’s point of view. It is important to consider the historical circumstances in which these decisions were taken. But it is also important to understand that since freelancers often literally “live their work,” the dividing line between private and working life is fluid, and personal events will often affect work issues. It is in this interaction between personal and professional life that questions of professional ethics usually arise. A closer look at Klein’s diaries allows us to identify the ethical values that guided his professional decisions, which had their origins in his youth and the early years of his film career.

In his very first diary entry, from 1936, Klein describes the origin of his passion for cinema. Like most filmmakers describing their background, Klein writes that he often went to the movie theater when he was younger. Inspired by the films he saw, he started making his own by splicing together pieces of film that he found.9 Even though this introductory episode might be romanticized and rose-tinted, it does point to a strong connection between life and work that not only shapes the reader’s perceptions of Klein’s work but also marks the starting point of a constant interaction between the spheres of work and life throughout his career. A central characteristic of the diaries is a lack of real separation between biographical information (such as the birth of his two daughters, as mentioned above) and information about Klein’s work; the two often appear side by side. Therefore, Klein’s 1936 diary entry encourages the reader not to view Klein’s life in isolation from cinema and his work. Klein would develop this personal vision of cinematic life over the years that followed: being part of an institution with a reliable and permanent employment contract, while maintaining his independence. All decisions concerning his career progression were guided by this vision.

While this preprofessional episode of Klein’s life sets up the parameters for the following decades, another episode in his early career explains why throughout his diaries there is barely any discussion of the content of his work. As mentioned before, Klein took his first steps into the world of film in his hometown, before working as a field camera operator for the Wehrmacht Propaganda Troops from 1942 until 1945, a position he took because he wanted to pursue a career in film.10 Earlier, in 1940, the Hitler Youth asked Klein to make a propaganda film about its work during the war, which was later called JUGEND IM KAMPF (Germany, 1940). Although he had already left the Hitler Youth in 1938, he agreed to make the film. Later, he discussed his moral conflict in his diary, saying that he did not support the views of the NSDAP (National Socialist German Workers’ Party) or the Hitler Youth but had only accepted the commission because it was an opportunity to hone his filmmaking skills.11

This short episode, years before his professional career began, shows two aspects of Klein’s professional ethics. First, it reveals a certain ambivalence, since from a retrospective and political point of view one might condemn his decision. Still, this decision has to be seen in its historical context.

Aside from the decision itself, the second important aspect of this episode is that it shows why there are no discussions of content throughout the diaries. When Klein attempts to justify his decision by reference to improving his skills, he places the process of filmmaking above the content of the film, as it was the filmmaking process itself that allowed him to fulfill his passion and hence the vision mentioned above. The act of filming was thus more important to him than the content and so there was no need to discuss the latter. Furthermore, Klein often described himself as a craftsman, interested in the practical side of things, rather than an artist, interested in the content or substance of the work.12

This lack of attention to content persisted during the following decades, including the years of the GDR: a period of Klein’s life when one might expect to find him making statements for or against the regime, or at least some sort of political statement. However, this would be a onesided view, since life in the GDR was not only black or white, for or against; rather, there were different shades of gray in between. Klein was definitely in between, since he managed to keep the balance between fulfilling his dream and his passion on the one hand and fulfilling the requirements of the institutions he worked for on the other. It is therefore completely understandable that there are almost no remarks about the political situation or the political system in his diaries.

However, there are some occasional brief exceptions. The most significant was during the days of the uprising that occurred in East Germany from June 16 to 17, 1953. A time when Klein was improving his standing as a freelancer, but was not yet fully established in the film and television sector. Inspired by the wind of change blowing through the country and its capital during these days, Klein decided to walk through Berlin and capture these historic moments on his film and still cameras. On the day following the uprising, Klein was arrested for taking a picture of the Soviet embassy in Berlin while documenting the events. After one night in prison, the authorities released him. Although he described this event and his feelings about his unjustified imprisonment in an unusually long diary entry of two pages,13 the uprising of 1953 was the only time he expressed such clear criticism of the GDR’s political system.

During the following decades, we can rarely find comments about the political system in his writings. Only toward the end of his active career, in the late 1980s, Klein does increasingly begin to express his views about the deteriorating political situation in his country. It is, however, important to note that at this point, his career was already at its peak and that he was an important figure in the production process of GDR television, and hence in a position where he could more easily express such thoughts.

Influences on Klein’s Career

As well as revealing a lot about Klein’s personality and way of thinking, these autobiographical sources also shed light on turning points in his working life. Below, I will discuss some examples showing how—due to the porous nature of the barrier between work and life—personal choices and decisions had a profound impact on his working life.

The first episode I shall discuss took place in 1948, while Klein was working for DEFA. Right after the war, in 1946, Klein restarted his professional career at DEFA’s educational films studio, thanks to a recommendation by his later mentor, camera operator Hans Paxmann. During the following two years, Klein and Paxmann worked together as a team, producing seven or so educational films for DEFA as permanent employees. However, in 1948, this situation suddenly changed when they found out their employer was planning to restructure the studio and cut down the number of permanent employees.14 Because of his loyalty to Paxmann, Klein decided to leave with him, and together they started their freelance career in the Soviet occupation zone.15 The pair went their separate ways a year later, in 1949.16

In contrast to the other examples discussed below, the decision to leave DEFA and go freelance might have been deliberate but was not yet driven by the vision discussed in the previous section. It reveals another facet of Klein’s personality that would influence his decision-making process in the following years: namely, that loyalty and passion for his work were essential for Klein. Furthermore, it also shows that being a freelancer was not yet a role Klein envisioned for himself and that it was only the circumstances (and of course his own decision) that had forced him into this new work situation.

It is interesting to see that this sense of loyalty also affected his career at another moment in his life. In 1958, by which point Klein was a well-known, in-demand freelance filmmaker, he founded the film and TV production collective Fernseh-Film-Produktionskollektiv Berlin with Günter Felgentreu, Walter Schwarz, and Günter Oscheck. Klein’s time with the collective was the most productive in his career. Between 1958 and 1968, the collective completed about 262 commissions for the GDR television network. A key distinguishing feature of the group was that its members were responsible for almost every step of the production process: from the development of the idea and writing of the script to the editing of the finished film project. 17 Despite this long period of success, it was the aforementioned values of loyalty and passion for one’s work that would lead to the collective’s end.

While Felgentreu left the group in 1963,18 Klein remained involved and indeed was the most active member during the following years. However, as he wrote in his diary, he noticed a dwindling interest, loyalty, and passion for the work they were doing among his remaining colleagues.19 Knowing that under these circumstances he would not be able to fulfill his vision, he decided to leave the group, and took his technical equipment with him. While there is no official document proving this for sure, the collective most likely ceased to exist after this episode, and the remaining members continued their work for DFF, probably as permanent employees.20

The moment when personal and biographical decisions had the most profound impact on Klein’s work came during the 1950s, when he was building his career as a freelance filmmaker in the GDR and regularly working for DFF. Despite the progress in his career and his negotiations with the state television broadcaster, he believed he could not yet fulfill his vision of freelance filmmaking, since freelance work was tolerated but not supported by the authorities.21

Without an apparent future in the GDR, he decided to leave the country and seek work in the Federal Republic of Germany. Prompted by rumors that GDR filmmakers were held in high regard in the West, he applied to be a camera operator at Nord- und Westdeutscher Rundfunkverband (NWRV) in Hamburg, the precursor to today’s public service TV channels Westdeutscher Rundfunk (WDR) and Norddeutscher Rundfunk (NDR). After six days in Hamburg, from June 29 until July 4, 1957, Klein returned to Berlin, since things did not turn out the way he planned and no contract was signed. Back home in the East, he finally decided to stay in the GDR and continue his career as a freelance filmmaker for the state broadcaster, in spite of the disadvantageous circumstances.22

Although only four years later, the Berlin Wall would take this decision out of his hands, the choice to stay in the GDR marked the definitive start of his television career in the socialist state, which lasted until about 1990 and was extremely productive, as can be seen from the above-discussed example of the Fernseh-Film-Produktionskollektiv Berlin.

Blind Spots in Television and Film History

While the examples discussed so far have revealed new information about Klein and his work, the following examples will show that biographical sources can also help to reveal new historical information and blind spots in television and film history that might not always be obvious from the resources available in other archives.

In this context, we might ask how big an impact Klein’s work had. Or, to put it another way, is the impact of one person on film and television history at this level really measurable? As noted above, this kind of question is based on the assumption that big institutions such as DEFA or DFF represent GDR film and television history. However, this article and the new film history approach discussed in the introduction suggest that there are more histories behind this history, and GDR film and television was more complex than it might seem at first glance. So even though it may be difficult to prove definitively how great an impact Klein’s work had, it can be shown or at least acknowledged that it did have some influence.

For a better understanding of the two following examples, it is important to remember that Klein got off to a very early start with his work for the television network. In September 1953, just a few months after the official launch of the GDR’s television programming (December 1952), he completed his first commission for television, a short documentary about a wine festival in Freyburg-Unstrut (in present-day Saxony-Anhalt).23 At that time, the GDR television broadcaster did not yet have the capacity to cope with the increasing demand for content that came with the advent of broadcasting, and so it needed people like Klein to produce this content.

In 1955, when Klein had already been working on a regular basis for the fledgling GDR television industry for two years, he suggested using 16 mm reversal film during shooting, 24 a procedure he had already successfully used for another employer in 1954 and that proved to be helpful in accelerating the production by cutting out the time-consuming step of film processing. According to Klein, the initial reactions of the other camera operators working for DFF at this time were not very positive. But television officials reacted positively and, as official sources confirm, reversal film was introduced as a standard procedure in the television production process in 1956.25 In addition, Klein also claimed that he suggested to Agfa Wolfen (later renamed ORWO),26 the state-owned brand for photographic products, that it produce reversal film exclusively for television.27

Since there are no official sources mentioning who came up with the idea of using reversal film for television, it is difficult to say whether Klein’s suggestion really was responsible for its introduction in the GDR television industry, and later for Agfa Wolfen and ORWO beginning the production of reversal film. It is, however, worth mentioning that Klein repeatedly complained that his fellow camera operators, disparagingly referring to him as “Umkehrheini”28 (“reversal fool”), did not want to accept the fact that he, as a freelancer and outsider, had an idea that successfully improved the production process.29

The second blind spot in television history concerns Klein’s contribution to improving the Pentacon AK 16 in 1956. The AK 16 was the first and only 16 mm camera produced in the GDR. Launched in September 1952, its compact, practical design meant it was suitable for amateurs as well as professionals. Klein bought his AK 16 in early 1953. However, as he points out a few times in various diary entries, the newly launched camera had a few technical problems that created serious difficulties for filmmakers, especially professional ones like himself.30 To solve the problem, he organized a meeting with all the political institutions and manufacturing companies involved in the production of the AK 16 on August 27, 1956. Just a few months after this meeting, in December 1956, VEB Zeiss Ikon Dresden, the company that manufactured the camera, presented the first improvements.31

Unlike with the first example mentioned in this section, archival material in Potsdam does corroborate the impact that this meeting had on television history, specifically on the use of the AK 16. However, although the material proves that the meeting did actually take place, research in other archives found no other source mentioning Klein as the originator of these improvements that could provide further evidence of his impact.

Conclusion

As noted at the beginning of this article, the new film history approach changed perspectives on film. It showed that behind the production process there is a complex network of people working together to make the production of a film possible. There is also a network of different information that opens up many different views on film and television history. This information mainly concerns the production process, and most previous research has neglected the inner and personal lives of those involved in the production. Based on the new film history approach, this article has presented a novel way of proceeding that incorporates biographical and personal information.

It is fair to say that Klein’s example is a very special one, particularly due to his work diaries presenting a unique inside view on his work and life. It is also clear that not every researcher can rely on archival sources of this sort for their film history research. Nonetheless, these sources can provide two types of new information. First, they can give a new, alternative perspective on the history of film and television and their production processes. By doing so, the sources can shed light on blind spots in film and television history that have been neglected in previous research or are not obvious from archival sources.

Second, they also show that the inner life and decision-making process of the person behind the production do have an impact on the work, even though they are not taken into consideration most of the time. This is important in the special case of freelance filmmakers, where the connection between life and work was even stronger because in most cases they were one-person production companies and the time-consuming process of filmmaking had a deep impact on their private lives. The boundary between personal and working life was therefore much thinner and the interaction between these two worlds much stronger than was the case for permanent employees.

Despite the new possibilities afforded by using these types of sources, it is important to maintain a critical distance when discussing them. As mentioned at the beginning, Klein’s diaries point to a strong connection between life and work, emphasizing that his work was his life and that a full understanding of his career requires understanding his personal life too. This might be true, since attending to his personal life reveals a lot of information, and the diaries are veritable treasure troves for research into freelance filmmakers in the GDR. However, it is important to properly distinguish the pieces of this puzzle: the facts that can be verified by other sources, the new information that must be confirmed and verified, and other information that cannot be definitively proved or disproved. While the first two categories are obviously useful, the third can also be of help. Although scholarly research requires us to prove and verify information by referring to other, conventional sources, unprovable information concerning matters such as personal emotions, or personal experiences such as Klein’s during the uprising in 1953, can lead to a better understanding of provable facts. This information should therefore be regarded as helping to complete the puzzle, the image as a whole.

- 1See Dennis Basaldella, Ein Leben für den Film: Der freie Filmhersteller Horst Klein und das Film- und Fernsehschaffen in der DDR (Marburg: Büchner-Verlag, 2020).

- 2See Petr Szczepanik, “The State-Socialist Mode of Production and the Political History of Production Culture,” in Behind the Screen: Inside European Production Cultures, ed. Petr Szczepanik and Patrick Vonderau (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 120.

- 3See ibid., 122.

- 4See Dagmar Schittly, Zwischen Regie und Regime: Die Filmpolitik der SED im Spiegel der DEFA-Produktionen (Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 2002), 89–90.

- 5The production in question was the film GRÜNDUNG DER DEUTSCH-AFRIKANISCHEN GESELLSCHAFT / FOUNDING OF THE GERMAN AFRICA SOCIETY (GDR, 1963), which Klein made for the Liga für Völkerfreundschaft (League of Friendship between Peoples). See Horst Klein, Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1959–1964 (Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3369), 5/61 (diary entry: March 17, 1961).

- 6See Basaldella, Ein Leben für den Film, 44–47.

- 7See ibid., 56–59.

- 8See ibid., 186.

- 9See Horst Klein, 1936 Meine Filmarbeit 1946 Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1936–1946 (Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3364), 1.

- 10See Basaldella, Ein Leben für den Film, 91–97.

- 11See Klein, 1936 Meine Filmarbeit 1946 Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1936–1946 (Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3364), 13–19 (diary entry: May, 1940).

- 12See Basaldella, Ein Leben für den Film, 70.

- 13See Horst Klein, Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1953–1956 (Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3367), 10–12 (diary entries: June 17, 1953, and June 18, 1953).

- 14See Basaldella, Ein Leben für den Film, 102 and 112–113.

- 15See ibid., 102.

- 16See ibid., 119–120.

- 17See ibid., 183–184.

- 18See ibid., 184.

- 19See ibid., 184.

- 20See Horst Klein, Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1965–1967 (Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3370), 27/67–28/67 (diary entry: October 20, 1967).

- 21See Basaldella, Ein Leben für den Film, 149–150.

- 22See Horst Klein, Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1957–1958 (Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3368), 138–139 (diary entry: June 29 to July 4, 1957), 147 (diary entry: September 7, 1957) and 160 (diary entry: December 11, 1957).

- 23See Basaldella, Ein Leben für den Film, 148.

- 24See ibid., 177–178.

- 25See Dieter Glatzer, Manfred Hempel, and Dieter Schmotz, eds., Die Entwicklung des Fernsehens der DDR (Folge 1: Zeittafel) (Berlin: Staatliches Komitee für Fernsehen beim Ministerrat der DDR, 1977), 45.

- 26ORWO stands for “Original Wolfen,” referring to the city of Wolfen in Saxony-Anhalt (Germany), where ORWO Filmfabrik Wolfen had its head office.

- 27See Basaldella, Ein Leben für den Film, 179–180.

- 28Ibid., 180.

- 29See ibid., 180.

- 30See ibid., 180–181.

- 31See Horst Klein, Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1953–1956, 106–107 (diary entry: August 27, 1956) and 114–115 (diary entry: December 4, 1956).

Basaldella, Dennis. Ein Leben für den Film: Der freie Filmhersteller Horst Klein und das Film- und Fernsehschaffen in der DDR. Marburg: Büchner-Verlag, 2020.

Glatzer, Dieter, Manfred Hempel, and Dieter Schmotz (eds.). Die Entwicklung des Fernsehens der DDR (Folge 1: Zeittafel). Berlin: Staatliches Komitee für Fernsehen beim Ministerrat der DDR, 1977.

Klein, Horst. 1936 Meine Filmarbeit 1946 Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1936–1946. Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3364.

Klein, Horst. Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1953–1956. Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3367.

Klein, Horst.Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1957–1958. Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3368.

Klein, Horst. Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1959–1964. Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3369.

Klein, Horst. Der Weg meiner Lebensarbeit – In einer betrogenen Generation 1965–1967. Filmmuseum Potsdam, archive number N008/3370.

Schittly, Dagmar. Zwischen Regie und Regime: Die Filmpolitik der SED im Spiegel der DEFA-Produktionen. Berlin: Ch. Links Verlag, 2002.

Szczepanik, Petr. “The State-Socialist Mode of Production and the Political History of Production Culture.” In Behind the Screen: Inside European Production Cultures, edited by Petr Szczepanik and Patrick Vonderau, 113–133. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.