Secret Publics

Preserving and Curating Audiovisual Traces of LGBTIQ+ Self-Documentation in Austria and Beyond

Table of Contents

Secret Publics

Digital Digging

Movie Theatre(s) of Memory

Filmography of the Genocide

Exacting the Trace

Destroyed Statues, a Bolex 16 mm Camera, and an Old Jeep

“…will you show that on your British television?” ACCEPTABLE LEVELS as Historiographic Metafiction

Work and Life

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Müller, Katharina. “Secret Publics: Preserving and Curating Audiovisual Traces of LGBTIQ+ Self-Documentation in Austria and beyond.” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces, no. 4 (February 2022): 1–24. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18099.

Memories cannot be conserved in drawers and pigeon-holes; in them the past is indissolubly woven into the present. … Precisely where they become controllable and objectified, where the subject believes himself entirely sure of them, memories fade like delicate wallpapers in bright sunlight.1

As a history of subcultures, queer history is always also a history of spaces, whether analogue or virtual, in which alternative ways of living are made possible. In Austria, this history unfolded within one of the most stubbornly hostile legal environments for queer people anywhere in (Western) Europe. Drawing on the Austrian Film Museum’s “Rainbow Films” collection (working title),2 this article explores the ephemeral audiovisual self-documentation of the LGBTIQ+ community in or with links to Austria. It focuses primarily on noncommercial films/videos produced outside formal artistic contexts: home movies, activist films, campaign videos, coming-out films, club films, etc. I propose conceiving of these films and videos not as “private films” but as ephemeral spaces of a “secret” but nonetheless real public that stands opposed to the omnipresent privatization of existence. Due to their diversity of themes, medium (8 or 16 mm film, video), and production context, and the various ways and reasons in or for which these media were consumed, I understand these spaces praxeologically as queer ephemeral media spaces. Historically, Austrian film and TV (in line with state-imposed broadcasting restrictions) largely ignored queer forms of life, and where they did appear they tended to be depicted and reproduced either in terms of a history of oppression or Othering stories of individual lives. But beyond the realm of official representation and government influence (and alongside a local subculture) the LGBTIQ+ community created queer ephemeral media spaces: spaces where people could negotiate the dimensions of queer existence, spaces where they could live and celebrate, discursive spaces of experience and self-discovery, spaces of coming-together, spaces of possibility. My postdoc research is concerned with topics of archiving and curation. Combining methods of historical assemblage theory, affect theory, and (digital) museum praxis, it explores how these spaces can be carved out, preserved, and/or made accessible as safe spaces.3 The core question is how the sexual, political, and aesthetic dimensions of existence inherent to them can be preserved and (as a political project) opened up in analogue and digital spaces. This raises a host of issues around media ethics, concerning matters such as the vulnerability of the people who appear in these films (as members of a socially marginalized group), the fragility of the physical media (which are stored in scattered locations, often in conditions not conducive to their preservation), the ontology of safe spaces, and approaches to privacy and metadata. If we understand these queer ephemeral media spaces as a resource (for queer history(ies) and future utopias of collective, connected communities), these issues in turn prompt questions about archival and curatorial agency with regard to these spaces: What strategic options are open to us between archival secrecy at the one extreme and indiscriminately uploading everything to the cloud at the other? And what bearing do the audiovisual traces left by film and video recordings over time have on this question? In this article, I draw on a corpus of a few thousand minutes of material (several days’ worth in total), which I began to explore last year in collaboration with a number of colleagues and partners.4 Aspiring for legal recognition, a politics of assimilation came to supplant a subculture already weakened by HIV in the 1980s. Second, 2000 was when video began to migrate onto the internet, ushering in a radical shift in media consumption patterns: interactive digital communication media and dating sites created a new sexual networking and communication culture that brought with it a dizzying quantity of “private” images. However, given that legal recognition was achieved relatively late on in Austria and that the country’s conservative turn came primarily, and very drastically, when the far right entered government in 2000, this upper limit will be “soft,” and examples from the 2000s will certainly not be completely excluded from my analysis. This article is the first publication to come out of my research on this topic. It is also the first time that audiovisual traces from some of the films and videos have been made public. In this context, I shall argue, the concept of audiovisual traces can serve a methodological and analytical function, allowing us to productively navigate ethical issues of conservation and curatorial practice that span the delicate parameters of in_visibility.

Queer Ephemeral Films and Videos as (Re)sources

In recent years, there has been growing interest worldwide among artists, curators, academics, and private individuals in the queer community’s ephemeral visual self-documentation. Alongside a comprehensive reevaluation of queer amateur photography,5 this also extends to audiovisual egodocuments,6 which have served as key historical sources for documentary films such as Stewart Maddux’s REEL IN THE CLOSET (US 2015) and for documentary series such as PRIDE (US 2021).7 They have also served as a point of reference or disembarkation for the fictions of a postmigrant queer cinema committed to structural transformation of society. One example is the archival fragment included in the opening sequence to the internationally acclaimed production FUTUR DREI / NO HARD FEELINGS (DE 2020). The fragment shows the director and actor Faraz Shariat as a child, wearing a Sailor Moon costume and singing and dancing in front of the TV, and so gives a historical dimension to the character he plays in the film. We do not see the whole document (i.e., the VHS that Shariat’s father took of his son) but an audiovisual trace of it, which here functions as a resource: “Queer, contrary to its contemporary representation in society, has a history,” observed Paulina Lorenz, part of the production collective behind FUTUR DREI, at a workshop on queer film.8 This history is crucial for visions and utopias of coexistence. And it is not just a history of oppression, contrary to how it has long been depicted in fiction and documentary films and as which it is often still structurally reproduced:9 The use of the Sailor Moon archival fragment can be understood as a cinematic strategy of resistance to normative temporal regimes. As hinted at by the film’s German title (which refers to a “third future tense,” alongside the simple future and future perfect), it opens itself up “radically to the future by moving backward toward a revolution.”10 Audiovisual traces like these can serve to make revolution (in the sense of an anticipated utopia) thinkable—and hence can have revolutionary potential. They are a source for conceptions of social transformation processes based on refiguring our “modes of relationship.”11 Yet they also refer to specific, historical lifeworlds.

Amateur films and videos are key sources for the history of the LGBTIQ+ community because they focus on “private” images that can be understood as self-conceptions, which represent an alternative to the pathologizing, externally imposed conceptions produced by the institutions of heteronormative mainstream society.12 As “counter stereotypical representations”13 free of cliches and commercial considerations, these films and videos convey something very different to mainstream films, including those made at a time when queer life was criminalized.14 Amateur films/videos and other ephemera also productively challenge conventional historical narratives of oppression and address the ambivalence of in_visibilities: For instance, lesbian amateur films from 1930s America15 show that the invisibility of people living as queer can actually be read as a form of freedom to be oneself without needing to hide.16 One way to understand queer ephemeral audiovisual media is as subcultural documents. The vast majority have a queer point of view, depict LGBTIQ+ people as complex individuals rather than stereotypes, and incorporate a diverse spectrum in terms of race, class, age, ethnic origin, political affiliation, gender identity, and so forth. Above all, they show LGBTIQ+ people in the context of our relationships, families (blood or found), and communities.17

If we understand “queer” in its historical dimension as a critique of power relations and oppression, of society and capitalism; if we regard an antiseparatist and antiassimilationist stance toward society as one of its most essential aspects;18 if—in line with the activists of the New Lesbian and Gay Movement—we understand “queer” as a demand for revolutionary change to a system driven by racism, sexism, militarism, and heterosexism;19 if, following Foucault, we understand “queer” as a sexual and aesthetic universe, an experience that can be articulated in artistic form or a “creative power”20 in its own right; if we see in “queer” an opportunity to leave the phallic system behind and adopt a postphallic perspective21—then ephemeral films and videos will be crucial agents of a historicity that points the way to the future.

“Queer” shares with ephemera a specific kind of temporality. Common to both is a history of loss: If, as Peter Rehberg proposes, we understand queer history not just as a history of social acceptance and legal reforms, but also as a “sexual experiment, and hence also always a social and subjective experiment,” that “seeks not just to make already-existing forms of power accessible to all but rather … to arrange power structures and subjects’ relations to them differently,” then “queer” is, “when we look back in retrospect, not just a history of triumph but also one of loss: As a radical sexual, social, and subjective experiment, ‘queer’ is constantly being lost.”22 And if, following Michael Loebenstein, we conceive of audiovisual ephemera as cinematic flotsam and jetsam, as debris of history,23 then queer ephemera can be understood as vestiges of the aspects of queerness that have been lost both in pragmatic politics and “grand narratives,” namely: “The sexual and aesthetic dimensions of our existence (which can collectively be taken as what Deleuze terms ‘desire’), which are often perceived as a challenge or threat, and so can abruptly shift into homophobia.”24

If we cast a critical gaze at the rise in museum exhibitions on LGBTIQ+ lives over the past decade, we will see that they “have been characterized by a focus on identity-based histories, rights, and political struggles, and structured by a progressivist ‘grand narrative’ culminating, most recently, in marriage equality.”25 As important as this framing is, it also reproduces a series of problematic norms and tends “to overlook queer lives and experiences that are not easily incorporated into an epistemology of the closet.”26

Against this backdrop, I would argue, ephemeral films and videos represent an extremely valuable source if we want to go beyond this framing and explore the sexual, aesthetic, and political dimensions of our existence and desires (as well as the revolutionary potential of modes of relationship) through the lens of a “queer ethics.”27 If, following Siegfried Mattl, we hold that ephemeral films “are”28 history and that, as Heide Schlüpmann claims, they are capable of mediating physical expression and hinting at revolutionary potentials in our society for which no words (yet) exist,29 this gives amateur films and videos produced in the context of queer self-documentation the status of a resource capable of (re)constituting society; if antidemocratic, totalitarian, repressive tendencies correlate with suppression of sexuality and desire and can be understood as a physical state,30 then conversely we can assume that sexuality and desire offer a potential with psychological, social, ethical, and political consequences, in particular with regard to the relation between “private” and “public.”31 As an alternative economy of the social, the homosexual/queer position is more than just a variation of sexual identities.32

In a 1998 video shot in his kitchen with no budget, Dietmar Schwärzler (who now runs the Vienna-based experimental film distributor sixpackfilm) offers an intersectional perspective on what this “more” might be. DIFFERENT VOICES PART5 (AT 1998) is an adaptation of the trailer for Kathryn Bigelow’s STRANGE DAYS (US 1995). Beginning with the question “Are you sexual?” Schwärzler gives a comprehensive list of possible permutations of sexuality—of different modes of relationship. The affective component is striking: Today, Schwärzler sees himself in this video as the “angry young man of the 1990s,” enraged at inequality. He says that his aim was to make a video promoting a cause to a wider public —“like what you’d nowadays put on YouTube or Instagram.”33

Extending this idea, there are also formal parallels to the safe spaces that a young generation of queer TikTok users have created with their videos as places to negotiate sexuality and provide mutual support.34 The direct address to the audience, the humorous element, and the pop culture reference are emblematic of a queer history that is not simply a linear (teleological) story of achieving “liberation” through “coming out” or social acceptance through assimilation, but also, going beyond representation, opens up a historical media and communication space imbued with affective qualities. These affective qualities pointed the way ahead for queer media and queer history, standing as they do for a practice of “relating” that is crucial to queer contexts and to a queer ethics of historical praxis. Queer kinship always involves an active process of building relationships between people: “They are relating, not related.”35

Vienna, the Beauty of Queerness and Unsafe Spaces: LGBTIQ+ Media Spaces in Austria

Vienna, May 1980. One day before the presidential election, members of the Vienna Homosexual Initiative (HOSI, founded 1979) asked passersby on the street if they would vote for their preferred candidate if he were gay. It was part of Austria’s first participatory media project (“Volks stöhnende Knochenschau”), whose declared ambition was to establish a “counter-public.” The resulting videos were displayed on the side of a van, which could be driven around and allowed the videos to reach a wider audience on the city’s roads, streets, and public squares. The project took place in the context of an audiovisual media landscape where two government-owned television stations got to set the agenda, with no space for marginal groups.36 Passersby responded that they would not vote for a gay candidate, and the interviewers were subjected to homophobia and hate speech. In the next sequence, we see members of HOSI setting up a temporary information stand at Wiener Festwochen alternativ (a radical alternative to the regular Wiener Festwochen, Vienna’s world-famous art festival).

This clip comes from one of the very few examples of self-documentation by the Austrian LGBTIQ+ community that is aimed at a general audience. Although HOSI activists were not in charge of the art direction for SCHWUL SEIN KANN SCHÖN SEIN / BEING GAY CAN BE BEAUTIFUL (AT 1980, 11 mins.), they were behind the camera. The video relates itself to the public sphere by reproducing the style of a news format (in this case, the anachronistic newsreel format). Even before HOSI established a permanent base of operations, it had carved out a space for itself with the video (and the temporary information stand that it documents): Media space preceded geographically situated space. Speaking to the camera, a member explains the broader social dimensions of the homosexual perspective: Without the liberation of homosexuality, she explains, true emancipation is impossible. Alongside several comingout videos, HOSI also produced the video HOSI BUDE REUMANNPLATZ / HOSI STAND ON REUMANNPLATZ (1980, 10 mins.), which tells the story of how the information stand was not long for this world: The local council ordered the police to intervene, and the stand was closed down shortly afterwards. The objection, as the council chair never tired of repeating, was that the stand would lure people into being gay. As in the previous video, the opinions of passersby were canvassed, and we can observe a field of conflict and negotiation between different views.

Over a decade earlier, in 1969, lesbians, gay men, and trans people protested against the routine police raids at New York’s Stonewall Inn. The year following the Stonewall Riots is regarded as a turning point in queer liberation. Ever since, annual pride marches have taken place in cities across the world, subject to local political conditions. This history of gay, lesbian, and trans liberation unfolded in Vienna, too, though somewhat later—and “more agreeably,”37 as one Green politician put it. Just as is the case for Europe as a whole, different urban contexts produce different experiences and understandings of queer life, identity, and subculture. These differences are bound up with national histories, laws, geography, immigration, conceptions of home, socialization, and each city’s local myths and stories.38 In this context, “agreeableness” (Gemütlichkeit) could be understood in terms of a dynamic peculiar to Vienna and its specific history. In any case, no mention was made of Stonewall in the Austrian news. Relations between “persons of the same sex” were prohibited as “unnatural lewdness” until 1971, when a minor legislative reform replaced the total ban on homosexuality with four new provisions. One of them (a ban on male prostitution) was repealed in 1989, while two others—a ban on promoting “lewdness with persons of the same sex or with animals” and a ban on associations “supporting same-sex lewdness”—remained in force until 1996.39 The latter two sections of the act, 220 and 221 respectively, were the greatest obstacle to political activism. A strict pornography law also banned depictions of same-sex acts, which even led to safer sex brochures ordered from the German AIDS Service being confiscated.40

Of the thousand or so VHS tapes stored by Vienna’s AIDS Service (either as educational films or as records of relevant media coverage), most of them copies of copies, the vast majority were produced outside Austria. Amidst a hodgepodge of mainly German, French, and American productions (including TV recordings, campaign films, and science films), we can also find one of the few campaigns produced in Austria: GIB AIDS KEINE CHANCE / DON’T GIVE AIDS A CHANCE (1994–1996), a collection of clips produced by the Viennese production company DoRo. Reflecting hegemonic structures, the campaign was aimed at a heterosexual audience. Text inserts such as “vaginal, anal, oral, normal” leave some ambiguity about the intended audience, but the messages of the dramatized segments starring Austrian celebrities do not. Josef Hader, now Austria’s most successful comedian, plays a straight, macho sex tourist, while popular singer Kurt Ostbahn says that AIDS “isn’t just an illness that affects gays and junkies.” By the time we get to the insert explaining that “women are at ten times greater risk than men,” it’s clear that the LGBTIQ+ community is at most included by its conspicuous absence. These campaigns are nonetheless significant in the context of queer processes of collectivization, and can still be found in community archives.

The struggle over Austria’s anti-LGB legislation continued to sharply divide the country’s politics between “liberal” and “conservative” camps.41 After the ban on promoting homosexuality was repealed in 1996 (the Austrian People’s Party unsuccessfully attempted to replace it with an even more restrictive anti-LGB law), the final provision to be overturned was section 209, which set the age of consent for “male homosexuals” at eighteen rather than fourteen as for heterosexual relations, despite the European Parliament, Council of Europe, and United Nations having called ever since the early 1980s for all laws discriminating against people on the grounds of homosexuality to be quashed. Section 209 was not repealed until 2002. A campaign video for Rechtskomitee Lambda, also produced by DoRo in collaboration with the filmmaker Stefan Ruzowitzky, can be regarded as one of the few examples of official self-documentation, at least in terms of representation: KEIN RECHT ZU LIEBEN: SCHWULE JUGENDLICHE IN ÖSTERREICH / NO RIGHT TO LOVE: YOUNG GAY MEN IN AUSTRIA (1995, 10 mins.) shows young gay men pointing out the absurdity of the law and the idea that the higher age of consent was to “protect” them: While a straight or lesbian sexual relationship between a twenty-year-old and a seventeen-year-old was permitted, the same relationship between two men would be a sexual offense. The clip makes reference to the Austrian Criminal Code, according to which all citizens are supposed to be equal before the law. At the start of the clip is a warning that it must not be shared without written authorization from Rechtskomitee Lambda, thus inscribing into the video a potential interest in sharing it. However, few other examples of films and videos made by LGBTIQ+ people in the period up to 1996 and aimed at a broader audience are to be found in the archives of grassroots groups and public LGBTIQ+ documentation centers.

Public-service broadcasters’ attitudes to homosexuality and queerness were marked by ignorance of the community’s political, cultural, and artistic concerns until into the 1990s. After that, coverage alternated between constructing personal narratives of suffering and victimhood (biographical experiences understood as personal misfortunes) and Othering depictions from an external perspective, most notably of the star presenters Günter Tolar and Alfons Haider who had recently come out. If news and current affairs programming reported on homosexuality at all, it was almost exclusively in connection with HIV/AIDS (an exception was the discussion show Club 2). From the late 1990s onward, official audiovisual coverage of LGBTIQ+ people in Austria concentrated, albeit with greater nuance than before, on their (isolated) identity through the prism of (“liberation” from) persecution and discrimination. The focus was on white male forms of homosexuality; queer and lesbian issues received barely any attention. 42 More recent coverage of same-sex marriage, the Life Ball, and rainbow parades attests to the legal and political success (achieved relatively late on in Austria) of an LGBTIQ+ culture and civil rights movement that, since the 1990s, has primarily concentrated in Europe on securing acceptance, assimilation, and mainstream visibility.

Queer Ephemeral Media Spaces as Subcultural and Transnational Publics

However, the visibility of LGBTIQ+ people in the mainstream at the same time brings with it a new invisibility and widespread exclusion: A history of victors (the success story of equal rights, same-sex marriage/civil partnerships, and antidiscrimination laws) effaces differences between groups and individuals, “dividing the (European-American) queers who are or wish to be integrated from … the homosexualities of the great remainder of the world”;43 it also excludes the affective life of queer cultures by assuming a “gay citizen whose affective fulfillment resides in assimilation, inclusion, and normalcy.”44 The assimilatory approach so fundamental to the LGBTIQ+ movement, whereby it seeks integration into the heteronormative, patriarchal world, subscribes to the consensus of a standardized way of life that relegates sexuality and desire (especially in their nonheteronormative forms) to the “private” sphere. It is there, in the vast expanse that lies outside the realm of representation and state interference, that (extended) egodocuments of queer relations and social movements have been produced ever since film was first invented. As discussed at the start, I understand these egodocuments praxeologically as queer ephemeral media spaces: amateur films, home movies, videos promoting a message or cause, activist films, campaign films, coming-out films, films of self-discovery, club films, films/videos produced for university projects or courses, and so on and so forth. Contra the standard definition, I do not understand these egodocuments as “private” films, since in their many and varied manifestations they stand opposed to the privatization of sex, desire, and existence. They contain audiovisual traces of a subculture that flourished behind closed doors from the 1950s onward despite oppression and persecution.45 In Vienna, this subculture was concentrated spatially in a few bars and a sauna, and evidence of it can be found in literary works, letters, stories, gossip columns, adverts, petitions, and many other sources.46 The history of the LGBTIQ+ movement in Austria (and countries to which queer Austrians emigrated) can be traced back to a first wave in the late nineteenth century. As with the women’s movement, a second wave then emerged in the decades after World War II.47 Its beginnings can be dated to the founding of the group Coming Out (CO) in 1975 and of the first lesbian group in the Autonomous Women’s Movement (AUF) in 1976.48

The first Bewegungsfilm, “film of a movement,” in the strict sense to document the queer movement was PFINGSTTREFFEN / SPRING CONFERENCE (AT 1977), also known by the title DAS SCHWULE TREFFEN / THE GAY CONFERENCE. In a “combination of reportage, documentary film, and contemporary political document,”49 we witness Austria’s first ever official queer conference at a rented villa in Purkersdorf. According to the voice-over, “150 German and 100 local [Austrian] homosexuals” met there. They discussed “the old questions of political relations to the mainstream left and the women’s movement.” Unlike its German counterpart, the Vienna queer group was not a student group, having emerged not out of the student and youth movement but only at a much later stage: “around one-and-a-half years ago,” according to the film. In the afternoon, we learn, “gay culture” was celebrated with “gay songs and sketches.” We see a performance of the song “Sie leben vom fremden Verkehr,”50 which casually presents us with structural racisms involving exoticized ideas of Arab masculinity (“cheap, submissively laughing Berbers”):

Given the very sparse documentation of the LGBTIQ+ movement in or with links to Austria, the ephemeral queer films and videos are a valuable resource for supplementing existing historical accounts of the movement and of everyday queer lives. They are also crucial to reinterpreting these histories through an intersectional lens, taking the axes of race, class, and gender into account. Films like PFINGSTTREFFEN, alongside numerous travel and vacation films, provide an avenue for studying the discourse of “oriental male sexuality,”51 a topic that is only gradually beginning to receive attention in Germanophone scholarship, and their constructions of hegemonial masculinity can be used to productively interrogate our contemporary society of migration. These films can be seen as inviting us to understand that, as Nanna Heidenreich puts it, “what is written about home movies must always be interrogated with [a view to] migration” and that “any purported archiving of ‘private’ films along nation-state lines must be viewed with mistrust.”52 Austria’s queer history is a history of emigration—stories like that of ORF journalist Rudy Stoiber, who emigrated to New York in 1955 and whose story is told in Katharina Miko and Raffel Frick’s documentary WARME GEFÜHLE / WARM FEELINGS (AT 2012); such stories transcend territorial borders and must be viewed from a “perspective of migration.”53 This perspective is an inclusive one that encompasses society as a whole. PFINGSTTREFFEN and many other films can also contribute significantly to an analysis of the role played by class differences in historical constructions of homo-, hetero-, and transsexuality. In GARDEROBENGEFLÜSTER / WHISPERS FROM THE DRESSING ROOM (AT 1973, 11 mins.), actor and dancer Franz Mulec shows us “a laughing world, overbrimming with good cheer,” before immediately relativizing his almost utopian queer universe: “But it’s all theater.” The Austrian Film Museum’s collection includes over sixty of Mulec’s films, made between 1960 and 1990. These films alone open up an incredibly rich universe of queer history.

Queer ephemeral media spaces are also of interest in relation to a curatorial activism54 that addresses the community and encourages artists and activists to engage with archival material in order to thematize and construct publics. Over the last two decades, there has been a decline in LGBTIQ+ spaces in European cities, affecting both state-subsidized spaces (in particular, spaces used by queer women, the trans community, and/or queer PoCs) and commercial spaces such as bars and discos. This decline has also affected queer film festivals and events, which can be seen as strategic political tools for reclaiming urban environments in neoliberal contexts by providing material and discursive spaces for the queer community.55 A recent example in Austria was the international queer film festival Identities, which was launched in 1993 and came to an end in 2017. Offering queer spaces for the community raises some pressing ethical issues: How should archivists and curators approach material that (unlike the films discussed above) was not demonstrably produced for a wider audience (or has already been publicly shown), and in which, as I shall show, there often appears to be an awareness of the impact that visibility to a wider audience might have? In the next section, I argue that “audiovisual traces” can play a key role in protecting people’s privacy while still respecting the interest in making material publicly available. When watching ephemeral films, these traces can help free us from the gravity of documents.

Queer Ethics or the Problem of Documents: Conceptualizing and Analyzing Audiovisual Traces

How do we archive sex? The messiness of it? The feel of it? The joy of it? The pain of it? How would we boil that down to a document?56

If we proceed from the premise that queer urban spaces play a central role in the subjectivity and sociality of LGBTIQ+ people,57 and that this applies equally to virtual spaces created by digital culture, then these questions posed by Ann Cvetkovich point to a key challenge for the archival preservation and historicization of these spaces: namely, that a document will struggle to convey the (discursive, social, material, sensuous, physical, affective) quality of the things that took place there. But what if we understand these LGBTIQ+ films and videos not as documents from which further documents can be made, but instead free ourselves from the burden of documents? Although understanding films/videos as (historical) documents may improve the estimation in which they are held by (film) historians, there may be difficulties with regard to the functions of evidence and proof inherent to documents. Since decriminalization, proof that someone belongs to an LGBTIQ+ social category has in most cases been a matter of subjective, rather than legal, documentation. While proving queerness may still be of central importance in certain legal contexts (for instance, if someone is seeking asylum due to being persecuted over their sexual orientation),58 the notion of “queer evidence” is highly problematic for a constructivist view of history.

A key aspect of the preservation and curation of queer ephemeral media spaces as safe spaces is the vulnerability of these films’/videos’ subjects. As Dagmar Brunow observes, although there is a wide array of queer perspectives on archives and queer archival exhibition practices, there has not yet been any comprehensive engagement with questions of how to address the ambivalences of queer visibility. Visibility is a disputed notion in the history of the LGBTIQ+ community. Like other forms of minority representation in visual culture, it does not automatically lead to empowerment. For queer people, visibility always also entails a risk of heightened vulnerability in the form of surveillance, governmentality, policing, pathologization, homophobic or transphobic violence, stereotyping, and shaming.59 In Austria, the situation is made further precarious by the fact that (except in Vienna) there is still no antidiscrimination law: LGBTIQ+ people can still be legally denied entry to events or access to certain goods and services based on their sexual orientation. Nationwide discrimination protections apply only in the workplace, not in day-to-day life.

So what approach are we to take to queer ephemeral media spaces? How are we to regard them in the context of collecting, archiving, exhibiting, and educating, and in the creation of social spaces? How are we to analyze them, given (among other things) the tension between the hermeneutic, systematic, and semiotic approaches that are typically adopted in studies of amateur films and tend to uphold (ideological) norms, and the strategic provisionality, nonfixability, and fluidity of “queer,” as described by Judith Butler?

Conceiving of ephemeral queer films and videos as documents is also problematic because it limits their potential. Having the status of a document is an obstacle to using these films and videos as sources of evidence or testimony, as for instance in classical “memorial practice” approaches. The testimonial character of LGBTIQ+ biographies in this context must, analogously to the crisis of testimony associated with the Holocaust, constantly be problematized, and alternative narrative forms favored. For example, it has been suggested that biographical LGBTIQ+ videos should be understood as fragmentary, literary stories in order to do justice to the people telling them.60

In my view, understanding queer films and videos as documents (and hence as entities) limits potential archival and curatorial approaches. Many of the films and videos could not be preserved and/or shown in full, but “traces” from them (sequences, fragments, individual shots, soundtracks, or transpositions of audiovisual content into new, different stories and artistic/activist configurations) could be. I therefore suggest that a focus on audiovisual traces could be a productive way to address ambivalences of visibility in queer history projects, with regard to analysis, preservation, and curation. The approach I am recommending would entail not avoiding these ambivalences, but shifting away from the (limiting) focus on “historical documents” as entities (which we must decide whether to make visible or not) in order to concentrate instead on audiovisual traces—and adopting a selective approach. In line with the methodology of historical assemblage theory,61 I understand audiovisual traces as agents from which collective practices of thought and action can be derived. A trace is not proof or evidence. Traces can be found whenever a focus on the practical consequences or impact of a piece of history (a collection, a name or label a framing, etc.) reveals an association; they are always concretions of empirically established associations. Latour speaks in this context of “matters of concern”: It is these, by contrast with “matters of fact,” that leave a trace. While society “had always been illustrated by boring, routine, millenary old matters of fact such as stones, rugs, mugs, and hammers,” “matters of concern” are not objects but rather “gatherings.”62 María Puig de la Bellacasa’s notion of “matters of care” expands on Latour’s theory in a way that is highly relevant to our present concerns (and to a critical understanding of history) and that takes issues of social injustice into account: “We must take care of things in order to remain responsible for their becomings.”63 But a focus on traces also entails asking who is being cared for and who is doing the caring, what motivates them, and, most crucially, what kind of care is needed.64

In this context, a trace can be anything and everything that “makes a difference”65 with regard to the relationship that we are seeking to establish (in this case, preserving and curating queer ephemeral media spaces as safe spaces in a way that “walk[s] the fine line between surveillance and empowerment”66). Traces free us from the gravity of documents. They also free films and videos from a state in which, as isolated objects, they stand outside a practice of collectivization or a queer praxis of “gathering” or “relating”: an active process that involves not simply generating awareness but opening up activities “that allow something to be set against an imposed privatization of existence as a contemporary form of socialization.”67

My proposal is that we focus on traces that articulate affective associations, particularly when analyzing films and videos from activist movements. In the context of social movements, affect and affection play a key role in processes of collectivization.68 Especially in political collectives and processes of collectivization where agents cannot unify around shared intentions, interests, identities, and concerns but instead present themselves as a community despite contradictions in their performative practices (as illustrated in the present case by the lack of alliances between lesbians and gay men, the dynamic between protest and assimilation, or the divisions between the intersectional categories of class and race), affective associations are traces of a peculiar kind: loose and unfixed, more like processes than things. Analyzing these associations will require us to focus not just on the agents’ motives but on affective processes between bodies. Their relation to other factors such as intentions, emotions, interests, economic conditions, representations, and communicative practices should be understood as one of coexistence rather than dualism.69 Moreover, they never achieve a final, stable state, and occupy an ambivalent position as a crucial force in both progressive and regressive movements.70

If, following Roger Odin, we understand queer ephemeral media spaces as “communicative spaces,”71 then affects (which, in their essence, are expressions of power72) occur in a variety of contexts: in discursive spaces (with the aim of persuading through rhetoric),73 in the aesthetic mode of viewing (whether in the viewing or the viewed subject),74 and in the artistic mode of functionalization. Traces of affective associations are empirically observable, and assume material form in effects of assemblage. They can also be fruitfully used in film analysis in the notion of affective images, which can be identified as moments of stillness in the narrative or plot.75 A turn to affects also promises a productive approach to ambivalences of in_visibility by offering a perspective that, as Mieke Bal describes, accords the central role not to representation but rather to effect or impact (a key consideration in curatorial contexts).76 Thus, if we have a curatorial interest with a primarily practical focus, concerned with producing modes of relationship, we must think beyond a strategy of making-visible— that is, of merely showing films and videos—and consider forms of exhibition not limited to publishing documents, conceived as entities. Instead, we could focus on identifying and elaborating on traces. If, accordingly, we ask how best to preserve and present ephemera in a way that keeps their relevance alive for future generations, then, as Cvetkovich points out, this will bring affects and affection into play—as well as the necessities of artistic curation as queer praxis. As Marie-Luise Angerer has suggested, affective associations should be understood within a context of media ecology and media technologies,77 in which nothing less than the conditions of a political community are articulated.

How Can Audiovisual Traces Help to Open up (Safer) Queer Ephemeral Media Spaces?

When it comes to constructing and conserving queer safe spaces, what strategic courses of action are open to us between archival secrecy at the one extreme and indiscriminately uploading everything to the cloud at the other?

The risks connected to the ambivalence of in_visibility become apparent right from the stage of collecting material; social invisibility and a minority position have impacted both on the original production of material (the prospective quantity of material predating the second wave of the LGBTIQ+ movement is presumably very small) and its subsequent preservation (the material is often stored in very unfavorable conditions78). When I asked whether HOSI, Austria’s main LGBTIQ+ lobby group, had any audiovisual ephemera stored at its head office, its chief executive at the time, Kurt Krickler, replied regretfully that all the film and video material had developed mold and been thrown away. Anna Szutt, Krickler’s successor in the role, reports that recordings and documents of the group’s activities are mainly circulated in WhatsApp groups, and that proper archiving of the videos is not possible with the resources the organization has available.

The situation is very different at Stichwort, the archive of the women’s and lesbian movement, where great sensitivity to issues of visibility has led to the collections being carefully guarded. The archive has around 700 minutes’ worth of activist videos on “lesbian themes.” The material is not publicly archived; in order to protect it from being abused or used for dubious purposes, it is accessible only to members, who must give a detailed explanation of the intended use. Although they are protected from unwanted access, the analogue videos are still susceptible to their natural enemies: Time, use, and chemical processes cause wear and tear. Some of the videos are badly damaged, with streaks or blemishes in the picture. The oldest video79—GEHEIME ÖFFENTLICHKEIT / SECRET PUBLIC (AT 1990)—addresses the legitimacy of film and video production within the women’s and lesbian movement itself. A panel discussion on the movement’s use of images was filmed, though the aim was “to experiment, rather than to document.”80 The formally selfreflexive video makes reference to the surveillance and control function of documentation and so addresses the ambivalence of audiovisual practices (between offensive appropriation on the one hand and rejecting them as tools of control on the other) in the context of activist movements.81 The voice-over commentary explores what it would mean if it were ultimately only possible to film bottles of mineral water.82

The fact that this and a dozen other activist videos (out of those so far selected and extracted from the full collection of activist videos) have collectively, and very deliberately, not been publicly archived despite arguably being a highly important piece of cultural heritage raises fundamental questions about trust and the work of building relationships, of relating. How can an antiseparatist attitude be translated into queer archival praxis? Another challenge concerns (meta)data associated with the documents in the collection: While the absence of (meta)data can be a sign of archival neglect, it can also be a strategy to protect the content against homo- and transphobia.83 I therefore propose expanding the concept of trace to the carrier media and their inscriptions. A focus on traces, which transcends the binarism of text and context, brings storage conditions and inscriptions into clear view: Often, as Paolo Caneppele and Raoul Schmidt observe, these tell their own stories.84

Audiovisual traces, and the affective associations and processes of collectivization connected with them, are not confined to images but can also be articulated verbally. In INTERVIEW— FRAU DES MONATS DEZEMBER 2005 / INTERVIEW WITH THE WOMAN OF THE MONTH, DECEMBER 2005 (AT 2006, 62 mins.), filmed by an unknown director, “woman of the month” Helga Pankratz—an author, critic, and activist—describes how since its founding HOSI had been a “boys’ club” run solely by gay male activists. Pankratz set up HOSI’s first lesbian group in the early 1980s, and later also a youth group. As chair of the lesbian group, she worked with impressive energy to achieve lesbian visibility in the fledgling homosexual movement and in wider society. In October 1981, at a performance of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s play The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1971) at Vienna’s Volkstheater, the HOSI lesbian group made its first public appearance. Through flyers distributed at the theater and a panel discussion with the director, they showed people “how things really are.” In INTERVIEW—FRAU DES MONATS DEZEMBER 2005, an anecdote becomes a trace that articulates an affective association. Until recently, this incident and its role in processes of collectivization has been left out of historical accounts; only with the fortieth anniversary of the HOSI lesbian group and the posthumous publication of some of Helga Pankratz’s photographs and writings did it come to public attention.85 Traces like this anecdote can point the way for a curatorial activism that combines queer archival praxis with artistic methods and allows history to be made active as a practice of relating, whether through classical reenactments or through activities on social media and video platforms.

When considering strategies for how to ethically approach images and narrative accounts, it is striking that we can learn from the images themselves, or rather from their audiovisual traces. This pertains to a wide array of formal strategies, both visual (abstraction, cutting, blurring, out-of-focus shots, zooms, extreme closeups, stills, etc.) and audial (anonymizing voices, voice-overs, etc.). A taxonomy86 of strategies (including both illustrative elements and performative forms such as reenactment, parody, or comedy) could be helpful to identify curatorial/expository approaches to communicating queer history (“themstory”), including in digital spaces.

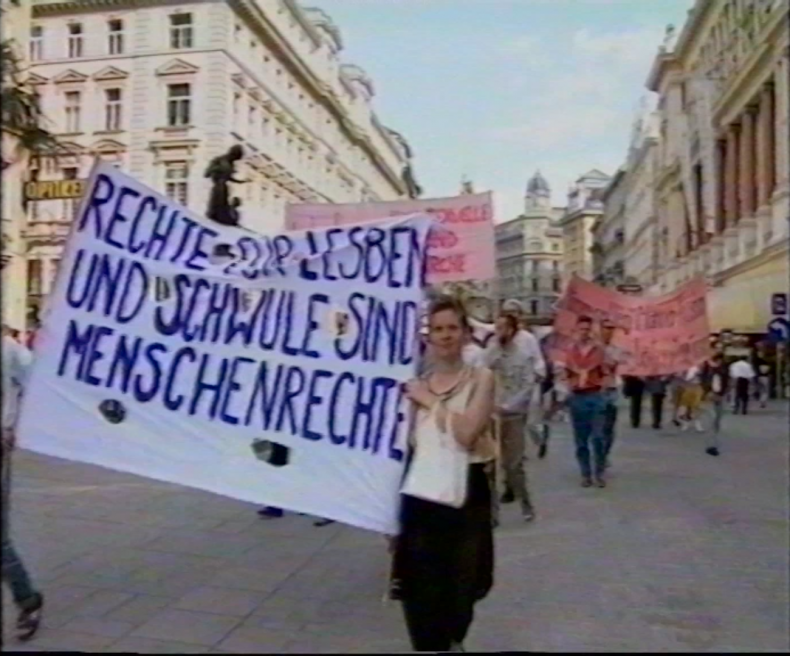

MENSCHENRECHT FÜR HOMOSEXUELLE / HUMAN RIGHTS FOR HOMOSEXUALS (AT undated) is a video of unknown date, though its content would suggest it must have been made before the ban on promoting homosexuality was repealed in the 1990s. In it, we can observe a convergence of video and social praxis. We can also find what, extending Donna Haraway’s notion of “situated knowledges,”87 we might term “situated images.” Angelika Haas and Nargis Mitev bring the viewer right up close to the action, as we move with the camera through a demonstration.

It is not yet clear what precise connection the filmmakers had to the events depicted in the video, but it can safely be classified as a Bewegungsfilm due to its positive relationship to a social movement.88 In the video, two people put their bodies at the disposal of the cause, give it a voice, and conduct interviews with demonstrators and representatives of Rosa Lila Villa—a building occupied by gays and lesbians in 1982 and run as a grassroots advice, cultural, and communication center. A soccer match in Vienna’s Prater park indicates a strategic sensitivity with regard to queer in_visibility; from off screen, the filmmaker jokingly remarks that this “proves” that “women can handle a soccer ball pretty well too.” The women’s bodies themselves, their soccer prowess aestheticized in slow motion, are pixelated and barely identifiable as people.

Things are more complex when it comes to analyzing traces from AIDS video activism. While official coverage by ORF (with some exceptions such as the sensitive reporting by Margit Hinke and Elisabeth Scharang for the youth show X-Large) tended to be problematic, depicting and reproducing HIV-positive people as victims and pariahs, we can still find examples of a more subjective, situated camera. It is striking that in the “genre” of AIDS video activism filmmakers and activists who were critical of mainstream representations nonetheless reproduced mass media techniques.89 We can find stylistic nods to music videos, references to blockbusters, inversions of talking heads’ expertise, and so on. AIDS IN ÖSTERREICH / AIDS IN AUSTRIA (AT 1987), directed by Aimée Klein while she was at university, presents people affected by HIV/AIDS in inverted colors, and draws further attention to this stylistic device with a text insert (Veränderte Aufnahme, “modified image”). Traces like this image, which makes reference to the sex worker and drug scene, open up a whole spectrum of affective potentials through their aesthetics and discursive function, as well as different ways of perceiving the documented collective: The traces appear to suggest an aesthetics of criminalization and surveillance as much as they do an intimate physical closeness and involvement.

With the words “It’s rolling” (“es geht schon”), Andreas Brunner (now codirector of the queer history center QWIEN) audibly indicates that the camera is on. His video STIEFELKNECHT (AT c. 1989, 25 mins.) reveals some of the problems involved in categorizing queer ephemera. At Stiefelknecht, a gay leather club in Vienna, we see men in fetish outfits, sometimes only filmed from the shoulders down. They follow Brunner’s directions and amuse themselves. But what is this, exactly? What is the work’s ontological status? Brunner and I had great fun watching the video back together, but the viewing left me none the wiser: He heard himself speaking and giving directions, but was unsure why and in what context he had made the video. From calendars and posters that can be identified in the background, it clearly dates from before the ban on promoting homosexuality was repealed. It is also clear that the video is unedited, though it appears to have been planned to edit it later. Brunner repeatedly reassures the film’s subjects that their identities will be protected and explains what will and will not be shown. “Your face isn’t being recorded anyway,” he jokes from off screen. In fact, however, dotted throughout the fragment are shots that were (presumably) not intended for the final cut: We see faces, including in closeup, and can recognize people. The entire half-hour video contains both staged sequences (mostly alluding to kink scenes) and ones that could be described as “making-of” footage: people standing around, waiting, staring, or simply hanging around the bar. If we were to extract audiovisual traces that the filmmaker marked off, either verbally or formally, as staged performance, we would be left with fragments such as the following:

Shots of buttocks—some naked, others covered by leather or jeans–can be interpreted as depicting a process of collectivization. The visual focus is on the handkerchiefs worn in the men’s pockets or around their necks. In the “hanky code” that was used in the pre-internet era, especially in the leather scene, the colors of handkerchiefs discreetly informed those in the know of the wearer’s sexual preferences and the sexual activities they were interested in—a very clear example of queer situated knowledge. This knowledge manifests not only as a counternarrative to the hegemonic, homophobic discourse of media and academia, but also in material form as a social space that makes continuities possible. The open-ended, fragmentary nature of the audiovisual trace (many other traces could be extracted from the half-hour video, such as the striking sequence showing Tom of Finland comics in closeup) allows it to be indefinitely extended and augmented—in line with the conditions of a queer ethics.

Finally, an incredible wealth of material not produced for commercial use can also be found in the archives of queer artists.

When, say, the photographer Sabine Schwaighofer takes a home video of Ashley Hans Scheirl flexing bulging muscles for the camera, or when experimental filmmaker Katrina Daschner dances down the streets of Vienna dressed as an orientalist-coded drag king, we see not only “how beautiful queerness is,” but also how forms of knowledge, experience, and community are given material form in aesthetic productions. A sensitivity to the risks of visibility, as noted by Dagmar Brunow, is inherent to many queer ephemeral media spaces. Where this sensitivity is palpably absent or its limits are tested, audiovisual traces can be helpful to us as extracts capable of being extended and elaborated. They grant us possibilities of agency, allowing us to cultivate a queer, postmigrant archival praxis of empowerment and encounter.

Translated by Andrew Andrew Godfrey and Hildegard Czinczoll

First published in German: Müller, Katharina. “Geheime Öffentlichkeiten: Zum Kuratieren audiovisueller Spuren der LGBTIQ+-Selbstdokumentation in und mit Verbindungslinien nach Österreich.” nach dem film (November 22, 2021). https://nachdemfilm.de/essays/geheime-oeffentlichkeiten.

- 1Theodor Adorno, Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life (London: Verso, 2005 (original German: 1951)), 166.

- 2While the term “rainbow films” may appear problematic with a view to the risks of “grand narratives,” it has advantages from a curatorial perspective due to its high recognition value.

- 3The term “safe spaces” generally refers to spaces created by and for socially marginalized people so that they can share their experiences and build a positive community. These spaces necessarily involve reflective engagement with issues of inclusion and exclusion.

- 4I am deeply indebted to Michael Loebenstein, Stefan Huber, Stefanie Zingl, Anna Högner, Andreas Brunner, Margit Hauser, and everyone else who has discussed this topic with me—in particular Andrea Braidt, Dagmar Brunow, Katrina Daschner, Karin Harrasser, Nanna Heidenreich, Katalin Kovacs, Peter Rehberg, Sabine Schwaighofer, Dietmar Schwärzler./fn] Part of this corpus is dispersed across private households, queer grassroots archives, and documentation centers, while the rest is held by or has been passed to the Austrian Film Museum. The material to be analyzed could potentially date all the way back to the emergence of narrow-gauge film; just how far back in history we are able to go will become clear as the collection develops. At the upper end, the year 2000 makes sense as a cutoff point for which films and videos to include in the analysis. First, it marks a “sharp conservative turn in the queer community, which saw the desire to change the whole replaced by a desire to partake in it.”Peter Rehberg, Hipster Porn: Queere Männlichkeiten und affektive Sexualitäten im Fanzine Butt (Berlin: b_books, 2018), 21.

- 5Examples include Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love 1850–1950 by the private collectors Hugh Nini and Neal Treadwell, institutional Instagram accounts like that of the New York-based Lesbian Herstory Archives (@lesbianherstoryarchives), and collective accounts like @lesbian_herstory. There are countless gay and queer profiles on Instagram that claim to be “historical,” though the physical sources of the images they share are often untraceable.

- 6Paolo Caneppele and Raoul Schmidt, “Der Amateurfilm als Ego-Dokument,” in Bewegtbilder und Alltagskultur(en): Von Super 8 über Video zum Handyfilm: Praktiken von Amateuren im Prozess der gesellschaftlichen Ästhetisierung, ed. Ute Holfelder and Klaus Schöneberger (Cologne: Herbert von Halem Verlag, 2017), 96. Caneppele and Schmidt operate with a trans-genre understanding of egodocuments that does not reduce the concept to historical and documentary aspects but also draws attention to recordings’ affective character.

- 7Directed by Tom Kalin, Andrew Ahn, Cheryl Dunye, Anthony Caronna, Alex Smith, Yance Ford, and Ro Haber, the documentary series looks at the development of LGBTIQ+ rights in the USA decade by decade. Footage from private individuals plays a central role, as strikingly seen in the use of material from the Nelson Sullivan Video Collection in the 1980s episode.

- 8“Queeres, postmigrantisches, feministisches kollektives Filmen, Erzählen, Schreiben und Produzieren,” workshop held on July 2, 2021, at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, Department of Transcultural Studies.

- 9An examination of European film funding bodies’ diversity policies and guidelines reveals that sexual minorities are often not included as a diversity category. Dagmar Brunow, “Naming, Shaming, Framing? The Ambivalence of Queer Visibility in Audio-Visual Archives,” in The Power of Vulnerability: Mobilising Affect in Feminist, Queer and Anti-Racist Media Cultures, ed. Anu Koivunen, Katariina Kyrölä, and Ingrid Ryberg (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018), 178, https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526133113.00017.

- 10Henriette Gunkel has described similar strategies in films such as Cheryl Dunye’s THE WATERMELON WOMAN. Henriette Gunkel, “Rückwärts in Richtung queerer Zukunft,” in Queer Cinema, ed. Dagmar Brunow and Simon Dickel (Mainz: Ventil Verlag, 2018), 77.

- 11Bini Adamczak, Beziehungsweise Revolution: 1917, 1968 und kommende (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2019), 225.

- 12Susanne Regener and Katrin Köppert, Privat / öffentlich: Mediale Selbstentwürfe von Homosexualität (Vienna: Turia + Kant, 2013), 11.

- 13Brunow, “Naming, Shaming, Framing?” 176.

- 14Sharon Thompson interviewed by Dagmar Brunow, “2021-03-27 Queer Archives—Three Interviews with Queer Archivists,” accessed July 10, 2021, https://saqmi.se/play/queer-archives-three-interviews-with-queer-archiv….

- 15These films were collected as part of the Lesbian Home Movie Project, thus far the only initiative of its kind in the world, which was founded as a nonprofit organization in 2009 by Sharon Thompson, Kate Horsefield, and B. Ruby Rich). See Sharon Thompson, “Urgent: The Lesbian Home Movie Project,” Journal of Lesbian Studies 19, no. 1 (2015): 114–116.

- 16Thompson and Brunow, “Three Interviews.”

- 17Lynne Kirste, “Collective Effort: Archiving LGBT Moving Images,” Cinema Journal 46, no. 3 (Spring 2007): 134.

- 18This was, for instance, the consensus of participants at the symposium “What Happened to Lesbian and Gay Studies?” held at ICI Berlin in June 2021, https://www.ici-berlin.org/events/what-happened-to-lesbian-and-gaystudi… (discussion panel IV).

- 19Barry D. Adam, The Rise of a Gay and Lesbian Movement (New York: Twayne, 1995), 82.

- 20Rehberg, Hipster Porn, 21.

- 21Peter Rehberg, “Energie ohne Macht: Christian Maurels Theorie des Anus im Kontext von Guy Hocquenghem und der Geschichte von Queer Theory,” in Für den Arsch, Christian Maurel (Berlin: August Verlag, 2019), 136.

- 22Rehberg, “Energie ohne Macht,” 139.

- 23Michael Loebenstein, “Österreichisches Filmmuseum: Abfall, Strand- und Treibgut,” in sich mit Sammlungen anlegen: Gemeinsame Dinge und alternative Dinge, ed. Martina Griesser-Stermscheg, Nora Sternfeld, and Luisa Ziaja (Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2020), 273.

- 24Rehberg, Hipster Porn, 21.

- 25Nikki Sullivan and Craig Middleton, Queering the Museum (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 28.

- 26Ibid.

- 27Ibid., 35.

- 28Drehli Robnik, “Alles einsetzen: Spiel, Stadt, Sammlung: Siegi Mattls filmischer Geschichts-Sinn,” in Die Strahlkraft der Stadt: Schriften zu Film und Geschichte, Siegfried Mattl (Vienna: Synema, 2016), 12.

- 29Heide Schlüpmann and Andrea Haller, Zu Wort kommen (Frankfurt: Kinothek Asta Nielsen, 2018), 8.

- 30Klaus Theweleit, Männerphantasien (Berlin: Matthes & Seitz, 2019 (1977/78)).

- 31Rehberg, “Energie ohne Macht,” 121.

- 32Ibid., 123.

- 33Interview with Dietmar Schwärzler, July 27, 2021.

- 34Emma Carey, “TikTok’s Queer ‘It Girls’ Are Creating New LGBTQ+ Safe Spaces,” them, October 1, 2020, https://www.them.us/story/tiktoks-queer-it-girls-create-lgbtq-safe-spac….

- 35From Rachel O’Neill’s introduction to the lesbian pop-up bar Mothers and Daughters: https://www.mothersanddaughters.be/about.

- 36See http://www.medienwerkstatt-wien.at/cataloge/katalog.php?seite=volks.

- 37In German: gemütlicher. Marco Schreuder, “Vorwort,” in Stonewall in Wien 1969–2009: Chronologie der lesbischschwulen-transgender Emazipation, ed. Andreas Brunner et al. (Vienna: Grüne Andersrum, QWien, and queer Lounge, 2019), 2.

- 38Jennifer V. Evans, Queer Cities, Queer Cultures: Europe since 1945 (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014), 1.

- 39Helmut Graupner, “Homosexualität und Strafrecht in Österreich: Eine Übersicht,” Rechtskomitee LAMBDA, August 27, 2002, https://www.rklambda.at/images/publikationen/209-9_18082003.pdf.

- 40Andreas Brunner et al., Stonewall in Wien 1969–2009: Chronologie der lesbisch-schwulen-transgender Emazipation (Vienna: Grüne Andersrum, QWien, and queer Lounge, 2019), 10.

- 41Matti Bunzl, “Outing as Performance / Outing as Resistance: A Queer Reading of Austrian (Homo)Sexualities,” in Same-Sex Cultures and Sexualities: An Anthropological Reader, ed. Jennifer Robertson (Malden: Blackwell, 2005), 145, https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470775981.ch12.

- 42Andreas Brunner et al. geheimsache:leben – schwule und lesben im wien des 20. Jahrhunderts (Vienna: Löcker Verlag, 2005), 71–72.

- 43Dirck Linck, “Welches Vergessen erinnere ich? Siegergeschichte: Zum Umgang der aufklärerischen Ästhetik mit einem Tabu,” FORUM Homosexualität und Literatur 30 (1997): 60.

- 44Ann Cvetkovich, An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures (Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2003), 10.

- 45Brunner et al., Stonewall in Wien, 4.

- 46Hanna Hacker, Frauen* und Freund_innen: Lesarten “weiblicher Homosexualität” Österreich, 1870–1938 (Vienna: Zaglossus, 2015), 13.

- 47Ute Gerhard, “Die ‘langen Wellen’ der Frauenbewegung. Traditionslinien und unerledigte Anliegen,” in Das Geschlechterverhältnis als Gegenstand der Sozialwissenschaften, ed. Regina Becker-Schmidt and Gudrun-Axeli Knapp (Frankfurt: Campus, 1995), 247–278.

- 48Ulrike Repnik, Die Geschichte der Lesben- und Schwulenbewegung in Österreich (Vienna: Milena Verlag, 2006), 83.

- 49Dietmar Schwärzler, “das schwule treffen,” in Identities 2003: Queer Film Festival (catalogue), 64.

- 50“They live from tourist/foreign trade”; the sexual innuendo is present in the German title too. Performed by musician Poldo Weinberger, a regular on Vienna’s gay scene, lyrics: Prunella de Queensland. The song, footage from the fragment, and a fragment from SCHWUL SEIN KANN SCHÖN SEIN appear in edited form in Katharina Miko and Raffael Frick’s documentary WARME GEFÜHLE (AUT 2012).

- 51See on this topic Christopher Treiblmayer’s ongoing project “Von Homoerotik zu Homophobie: Zur Dekonstruktion stereotyper Sexualitäts- bzw. Männlichkeitsbilder des ‘Orients’ (1850–2016)” (“From homoeroticism to homophobia: on the deconstruction of stereotypical images of sexuality and masculinity in the ‘Orient’”), https://www.qwien.at/forschung-projekte/laufende-projekte-qwien/von-hom….

- 52Nanna Heidenreich, “Das Narrativ der nationalen Umfassung beschädigen,” in unnamed edited volume (title to be confirmed), ed. Alejandro Bachmann and Michelle Koch, forthcoming in 2022.

- 53Nanna Heidenreich, V/Erkennungsdienste: Das Kino und die Perspektive der Migration (Bielefeld, transcript 2015).

- 54Maura Reilly, Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating (New York: Thames and Hudson 2018).

- 55Theresa Heath, “Neoliberalism, Politics and Resistance: Queer Film Festivals and the Fight against Urban Erasure,” Altre Modernità 20 (2018): 118.

- 56Ann Cvetkovich, “Artist Curation as Queer Archival Practice,” filmed November 2019 at Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC)at Rensselaer, New York, video, 1:25:43, https://empac.rpi.edu/events/2019/artist-curation-queer-archival-practi….

- 57Gill Valentine and Tracey Skelton, “Finding Oneself, Losing Oneself: The Lesbian ‘Scene’ as a Paradoxical Space,” International Journal of Urban andRegional Research 27 (2003): 849–866.

- 58Heather Scavone, “Queer Evidence: The Peculiar Evidentiary Burden Faced by Asylum Applicants with Cases Based on Sexual Orientation and Identity,” Elon Law Review 5 (2013): 390.

- 59Brunow, “Naming, Shaming, Framing?” 176.

- 60Daniel Baranowski, “Geheime Augenblicke, öffentlich wiederholt: Zum Zeugnischarakter der Lebensgeschichten im ‘Archiv der anderen Erinnerungen,’” Invertito – Jahrbuch für Geschichte der Homosexualitäten 22 (2020): 133.

- 61I regard Bruno Latour’s study of the Aramis transit project as a prime example of constructivist historical assemblage research that focuses on failure (rather than success). Bruno Latour, Aramis or The Love of Technology (Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2002).

- 62Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 114.

- 63María Puig de la Bellacasa, Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017), 43.

- 64Bellacasa, Matters of Care, 61.

- 65Latour, Reassembling the Social, 252.

- 66Brunow, “Naming, Shaming, Framing?” 190.

- 67Andrea Seier, “Plädoyer für notwendige Illusionen: Kritik neu erfinden,” Navigationen – Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturwissenschaften 2 (2016): 135, https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1676.

- 68Christian Helge Peters, “Affekttheorien und soziale Bewegungen: Kollektivierungen, Affizierungen und Affektmodulationen in Bürgerwehren,” in Handbuch Poststrukturalistische Perspektiven auf soziale Bewegungen, ed. Judith Vey, Johanna Leinius, and Ingmar Hagemann (Bielefeld: transcript, 2019), 155, https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839448793-010.

- 69Peters, “Affekttheorien und soziale Bewegungen,” 162.

- 70Ibid., 163.

- 71Roger Odin, Kommunikationsräume: Einführung in die Semiopragmatik (Berlin: oa books, 2019).

- 72Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 1: The Movement-Image (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986), 97.

- 73Odin, Kommunikationsräume, 143.

- 74Ibid., 93.

- 75Anke Zechner, “Das Affektbild als Stillstand der Narration: Überlegungen zur Schlussszene von VIVE L’AMOUR – ES LEBE DIE LIEBE,” in Affekte: Analysen ästhetisch-medialer Prozesse, ed. Antje Krause-Wahl, Heike Oehlschlägel, and Serjoscha Wiemer (Bielefeld: transcript, 2006), 155.

- 76Mieke Bal, “Affekt als kulturelle Kraft,” in Affekte: Analysen ästhetisch-medialer Prozesse, ed. Antje Krause-Wahl, Heike Oehlschlägel, and Serjoscha Wiemer (Bielefeld: transcript, 2006), 7–19.

- 77Marie-Luise Angerer, Affektökologie (Lüneburg: meson press, 2017), 24.

- 78Brunow, “Naming, Shaming, Framing?” 183.

- 79“Geheime Öffentlichkeit,” panel discussion, organized by Stichwort, October 21, 1990, VHS, Austria 1990.

- 80Hanna Hacker at the event “Dokumente sprechen feministisch zurück,” Vienna, December 13, 2013. See Renée Winter, “Feministische Videopraktiken im Wien der 1980er Jahre und die Notwendigkeit lustvoller Space-Offs,” in Geschlechtergeschichten vom Genuss: Zum 60. Geburtstag von Gabriella Hauch, ed. Theresa Adamski et al. (Vienna: Mandelbaum, 2019), 70.

- 81Ibid.

- 82Ibid.

- 83Brunow, “Naming, Shaming, Framing?” 183.

- 84Paolo Caneppele and Raoul Schmidt, “Die Flüchtigkeit festhalten: Von der Melancholie des Sammelns,” in Abenteuer Alltag: Zur Archäologie des Amateurfilms, ed. Siegfried Mattl, Carina Lesky, Vrääth Öhner, and Ingo Zechner (Vienna: Synema, 2015), 149.

- 85Barbara Fröhlich and Petra M. Springer, eds., SICHTBAR – 40 Jahre HOSI-Wien-Lesben*gruppe (Vienna: Edition Regenbogen, 2021), 26.

- 86An example of this can be seen in the project Visual History of the Holocaust: Rethinking Curation in the Digital Age, which is being run by the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Digital History (Vienna) in collaboration with the Austrian Film Museum. See https://www.vhh-project.eu andhttps://www.vhh-project.eu/deliverables/d….

- 87Donna Haraway, “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Priviledge of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–599.

- 88Julia Zutavern, Politik des Bewegungsfilms (Marburg: Schüren, 2015), 13.

- 89Jim Hubbard, “AIDS-Videoaktivismus und die Entstehung des ‘Archivs,’” in Queer Cinema, ed. Dagmar Brunow and Simon Dickel (Mainz: Ventil Verlag, 2018), 91.

Adam, Barry D. The Rise of a Gay and Lesbian Movement. New York: Twayne, 1995.

Adamczak, Bini. Beziehungsweise Revolution: 1917, 1968 und kommende. Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2019.

Adorno, Theodor. Minima Moralia: Reflections on a Damaged Life. London: Verso, 2005.

Angerer, Marie-Luise. Affektökologie. Lüneburg: meson press, 2017.

Bal, Mieke. “Affekt als kulturelle Kraft.” In Affekte: Analysen ästhetisch-medialer Prozesse, edited by Antje Krause-Wahl, Heike Oehlschlägel, and Serjoscha Wiemer, 7–19. Bielefeld: transcript, 2006.

Baranowski, Daniel. “Geheime Augenblicke, öffentlich wiederholt: Zum Zeugnischarakter der Lebensgeschichten im ‘Archiv der anderen Erinnerungen.’” Invertito – Jahrbuch für Geschichte der Homosexualitäten 22 (2020): 132–141.

Brunner, Andreas, et al. geheimsache:leben – schwule und lesben im wien des 20. Jahrhunderts. Vienna: Löcker Verlag, 2005.

Brunner, Andreas, Ewa Dziedzic, Iris Hajicsek, Marco Schreuder, and Hannes Sulzenbarcher. Stonewall in Wien 1969–2009: Chronologie der lesbisch-schwulen-transgender Emazipation. Vienna: Grüne Andersrum, QWien, and queer Lounge, 2019.

Brunow, Dagmar. “Naming, Shaming, Framing? The Ambivalence of Queer Visibility in AudioVisual Archives.” In The Power of Vulnerability: Mobilising Affect in Feminist, Queer and Anti-Racist Media Cultures, edited by Anu Koivunen, Katariina Kyrölä, and Ingrid Ryberg, 175–194. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018. https://doi.org/10.7765/9781526133113.00017.

Brunow, Dagmar, and Simon Dickel. Queer Cinema. Mainz: Ventil Verlag, 2018.

Bunzl, Matti. “Outing as Performance / Outing as Resistance: A Queer Reading of Austrian (Homo)Sexualities.” In Same-Sex Cultures and Sexualities: An Anthropological Reader, edited by Jennifer Robertson, 129–151. Malden: Blackwell, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470775981.ch12.

Caneppele, Paolo, and Raoul Schmidt. “Die Flüchtigkeit festhalten: Von der Melancholie des Sammelns.” In Abenteuer Alltag: Zur Archäologie des Amateurfilms, edited by Siegfried Mattl, Carina Lesky, Vrääth Öhner, and Ingo Zechner, 143–149. Vienna: Synema, 2015.

Caneppele, Paolo, and Raoul Schmidt. “Der Amateurfilm als Ego-Dokument.” In Bewegtbilder und Alltagskultur(en): Von Super 8 über Video zum Handyfilm: Praktiken von Amateuren im Prozess der gesellschaftlichen Ästhetisierung, edited by Ute Holfelder and Klaus Schöneberger, 96–105. Cologne: Herbert von Halem Verlag, 2017.

Carey, Emma. “TikTok’s Queer ‘It Girls’ Are Creating New LGBTQ+ Safe Spaces.” them, October 1, 2020. https://www.them.us/story/tiktoks-queer-it-girls-create-lgbtq-safe-spac….

Cvetkovich, Ann. An Archive of Feelings: Trauma, Sexuality, and Lesbian Public Cultures. Durham, NC, and London: Duke University Press, 2003.

Cvetkovich, Ann. “Artist Curation as Queer Archival Practice.” Filmed November 2019 at Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center (EMPAC) at Rensselaer, New York. Video, 1:25:43. https://empac.rpi.edu/events/2019/artist-curation-queer-archival-practi….

Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 1: The Movement-Image. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1986.

Evans, Jennifer V. Queer Cities, Queer Cultures: Europe since 1945. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

Fröhlich, Barbara, and Petra M. Springer, eds. SICHTBAR – 40 Jahre HOSI-Wien-Lesben*gruppe. Vienna: Edition Regenbogen, 2021.

Gerhard, Ute. “Die ‘langen Wellen’ der Frauenbewegung: Traditionslinien und unerledigte Anliegen.” In Das Geschlechterverhältnis als Gegenstand der Sozialwissenschaften, edited by Regina Becker-Schmidt and Gudrun-Axeli Knapp, 247–278. Frankfurt: Campus, 1995.

Graupner, Helmut. “Homosexualität und Strafrecht in Österreich: Eine Übersicht.” Rechtskomitee LAMBDA, August 27, 2002. https://www.rklambda.at/images/publikationen/209-9_18082003.pdf.

Gunkel, Henriette. “Rückwärts in Richtung queerer Zukunft.” In Queer Cinema, edited by Dagmar Brunow and Simon Dickel, 68–81. Mainz: Ventil Verlag, 2018.

Hacker, Hanna. Frauen* und Freund_innen: Lesarten “weiblicher Homosexualität” Österreich, 1870–1938. Vienna: Zaglossus, 2015.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective,” Feminist Studies 14, no. 3 (1988): 575–599.

Heath, Theresa. “Neoliberalism, Politics and Resistance: Queer Film Festivals and the Fight against Urban Erasure,” Altre Modernità 20 (2018): 118–135. https://doi.org/10.13130/2035-7680/10827.

Heidenreich, Nanna. V/Erkennungsdienste: Das Kino und die Perspektive der Migration. Bielefeld, transcript 2015.

Heidenreich, Nanna. “Das Narrativ der nationalen Umfassung beschädigen.” In unnamed edited volume (title to be confirmed), edited by Alejandro Bachmann and Michelle Koch, forthcoming 2022.

Hubbard, Jim. “AIDS-Videoaktivismus und die Entstehung des ‘Archivs.’” In Queer Cinema, edited by Dagmar Brunow and Simon Dickel, 82–105. Mainz: Ventil Verlag, 2018.

Kirste, Lynne. “Collective Effort: Archiving LGBT Moving Images,” Cinema Journal 46, no. 3 (2007): 134–140.

Koivunen, Anu, Katariina Kyrölä, and Ingrid Ryberg. The Power of Vulnerability: Mobilising Affect in Feminist, Queer and Anti-Racist Media Cultures. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018.

Latour, Bruno. Aramis or The Love of Technology. Cambridge, MA, and London: Harvard University Press, 2002.

Latour, Bruno. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Linck, Dirck. “Welches Vergessen erinnere ich? Siegergeschichte: Zum Umgang der aufklärerischen Ästhetik mit einem Tabu,” FORUM Homosexualität und Literatur 30 (1997): 59–82.

Loebenstein, Michael. “Österreichisches Filmmuseum: Abfall, Strand- und Treibgut.” In Sich mit Sammlungen anlegen: Gemeinsame Dinge und alternative Dinge, edited by Martina Griesser-Stermscheg, Nora Sternfeld, and Luisa Ziaja, 272–274. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2020.

Odin, Roger. Kommunikationsräume: Einführung in die Semiopragmatik. Berlin: oa books, 2019.

Peters, Christian Helge. “Affekttheorien und soziale Bewegungen: Kollektivierungen, Affizierungen und Affektmodulationen in Bürgerwehren.” In Handbuch Poststrukturalistische Perspektiven auf soziale Bewegungen, edited by Judith Vey, Johanna Leinius, and Ingmar Hagemann, 155. Bielefeld: transcript, 2019. https://doi.org/10.14361/9783839448793-010" \t "_blank.

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More Than Human Worlds. Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Regener, Susanne, and Katrin Köppert. Privat / öffentlich: Mediale Selbstentwürfe von Homosexualität. Vienna: Turia + Kant, 2013.

Rehberg, Peter. Hipster Porn: Queere Männlichkeiten und affektive Sexualitäten im Fanzine Butt. Berlin: b_books, 2018.

Rehberg, Peter. “Energie ohne Macht: Christian Maurels Theorie des Anus im Kontext von Guy Hocquenghem und der Geschichte von Queer Theory.” In Für den Arsch, Christian Maurel, 99–139. Berlin: August Verlag, 2019.

Reilly, Maura. Curatorial Activism: Towards an Ethics of Curating. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2018.

Repnik, Ulrike. Die Geschichte der Lesben- und Schwulenbewegung in Österreich. Vienna: Milena Verlag, 2006.

Robnik, Drehli. “Alles einsetzen: Spiel, Stadt, Sammlung: Siegi Mattls filmischer Geschichts-Sinn.” In Die Strahlkraft der Stadt: Schriften zu Film und Geschichte, edited by Drehli Robnik, 6–14. Vienna: Synema, 2016.

Scavone, Heather. “Queer Evidence: The Peculiar Evidentiary Burden Faced by Asylum Applicants with Cases Based on Sexual Orientation and Identity,” Elon Law Review 5 (2013): 389–413.

Schlüpmann, Heide, and Andrea Haller. Zu Wort kommen. Frankfurt: Kinothek Asta Nielsen, 2018.

Schreuder, Marco. “Vorwort.” In Stonewall in Wien 1969–2009: Chronologie der lesbischschwulen-transgender Emazipation, edited by Andreas Brunner et al., 2. Vienna: Grüne Andersrum, QWien, and queer Lounge, 2019.

Schwärzler, Dietmar. “das schwule treffen.” In Identities 2003: Queer Film Festival (catalogue).

Seier, Andrea. “Plädoyer für notwendige Illusionen: Kritik neu erfinden,” Navigationen – Zeitschrift für Medien- und Kulturwissenschaften 2 (2016): 125–143. https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/1676.

Sullivan, Nikki, and Craig Middleton. Queering the Museum. London and New York: Routledge, 2020.

Theweleit, Klaus. Männerphantasien. Berlin: Matthes & Seitz, 2019 (1977/78).

Thompson, Sharon. “Urgent: The Lesbian Home Movie Project,” Journal of Lesbian Studies 19, no. 1 (2015): 114–116.

Thompson, Sharon, interviewed by Dagmar Brunow. “2021-03-27 Queer Archives—Three Interviews with Queer Archivists.” Accessed July 10, 2021. https://saqmi.se/play/queer-archivesthree-interviews-with-queer-archivi….

Valentine, Gill, and Tracey Skelton. “Finding Oneself, Losing Oneself: The Lesbian ‘Scene’ as a Paradoxical Space,” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 27 (2003): 849–866.

Winter, Renée. “Feministische Videopraktiken im Wien der 1980er Jahre und die Notwendigkeit lustvoller Space-Offs.” In Geschlechtergeschichten vom Genuss: Zum 60. Geburtstag von Gabriella Hauch, edited by Theresa Adamski et al., 66–75. Vienna: Mandelbaum, 2019.

Zechner, Anke. “Das Affektbild als Stillstand der Narration: Überlegungen zur Schlussszene von VIVE L’AMOUR – ES LEBE DIE LIEBE.” In Affekte: Analysen ästhetisch-medialer Prozesse, edited by Antje Krause-Wahl, Heike Oehlschlägel, and Serjoscha Wiemer, 155–167. Bielefeld: transcript, 2006.

Zutavern, Julia. Politik des Bewegungsfilms. Marburg: Schüren, 2015.