Movie Theatre(s) of Memory

Audiovisual Traces, Reenactment, and Remediation in CINE MARROCOS (BR 2018)

Table of Contents

Secret Publics

Digital Digging

Movie Theatre(s) of Memory

Filmography of the Genocide

Exacting the Trace

Destroyed Statues, a Bolex 16 mm Camera, and an Old Jeep

“…will you show that on your British television?” ACCEPTABLE LEVELS as Historiographic Metafiction

Work and Life

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Krämer, Marie. “Movie Theatre(s) of Memory: Audiovisual Traces, Reenactment and Remediation in CINE MARROCOS (BR 2018).” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces, no. 4 (February 2022): 1–14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18101.

1. Introduction

A dark room, lit by a handheld spotlight. Carefully, almost searchingly, a man illuminates every corner. Remnants of a cinema architecture emerge: the windows of a projection booth, rows of worn red leather seats. The camera climbs a staircase, lined with dusty strips of celluloid. Who left them there? What would we see if they were revived? With these atmospheric shots, the documentary CINE MARROCOS (Ricardo Calil, BR 2018) begins a search for traces in a former cinema in São Paulo, Brazil. Opened in 1951, Cine Marrocos was once considered one of the most luxurious cinemas in South America. In 1954, it even hosted Brazil’s first international film festival, the Festival Internacional de Cinema do Brasil. After decades of decline, the Marrocos closed its doors in 1994 and stood empty before being occupied in 2013. Until its eviction in 2016, the building housed up to 3,000 homeless people and immigrants from South and Central America and Africa. Together with them, Calil ventures a “performative mobilisation of trace carriers.”1 But what traces does such an ephemeral event as a film festival actually leave behind? And how can we make them visible, record them, preserve them, but also share, recirculate, and renegotiate them?

Since only little footage from the 1954 Festival do Brasil has survived,2 CINE MARROCOS relies on reenactment. But it is not the festival that is being reenacted. Rather, the Maroccos’ residents reenact scenes from films that were shown at the time and have since become classics. As only films from Western Europe and the US are reenacted, although the festival also featured Brazilian productions,3 CINE MARROCOS on the one hand contributes to the consolidation of Western-dominated canons: “The canon of classical texts is not only taught from generation to generation but also performed […]. It is only a tiny segment of the vast history of the arts that has the privilege of repeated presentation and reception which ensures its aura and supports its canonical status.”4 On the other hand, CINE MARROCOS allows the reenactors a “bodily appropriation of historical images.”5 Film figures such as Maréchal (LA GRANDE ILLUSION, Jean Renoir, F 1937) and Norma Desmond (SUNSET BOULEVARD, Billy Wilder, USA 1950) become “projection surfaces – for experiences as varied as war trauma, depression, disgust of affluence and post-colonial alienation.”6 Through interviews, CINE MARROCOS also gives the reenactors a name and (hi)story. In a sense, they become ‘film stars’ themselves and leave their own traces—at the former festival venue, in the documentary and with its audiences. CINE MARROCOS thus contributes to processes of remediation, where “[e]ach renewed publication might create a new context […] and adds a new layer of meaning.”7

Oscillating between these poles, I explore the memory dynamics that CINE MARROCOS unfolds between screen and stage, ‘originals’ and reenactments, the audiences of then, now and tomorrow. To this end, I first outline the concepts of “reenactment” and “remediation” and their role in cultural memory. Based on close readings of selected scenes, I then examine how reenactment and remediation are used in CINE MARROCOS to (re)read exisiting, but also to (re)write new audiovisual traces.8

2. Between Reenactment and Remediation

The term “reenactment” describes a broad spectrum of (memory-)cultural “practices of locating, embodying and representing,” as well as aesthetic strategies of “restaging, reliving and revising.”9 Considering the many meanings of the prefix “re,”10 reenactments simultaneously perform a retrieval of the past, and a repetition that can only take place retrospectively and therefore must deviate from ‘the original’.11 Through this double gesture, reenactments mark events as worthy of remembrance and shape their commemoration:

They are rituals which ‘canonize’ particular events, in the sense of giving them a sacred or exemplary quality, making them ‘historic’ as well as historical. They tell a story, present a ‘grand narrative’, or make it grand by performing it. They reconstruct history or ‘re-collect’ or ‘re-member’ it in the sense of practising bricolage, assembling fragments of the past into new patterns.12

Reenactments create a peculiar, ghostly temporality that simultaneously approximates and separates past and present. While some reenactments strive for a reconstruction of and immersion into the past, others draw clearer lines between past, present and potential future(s).13 In addition to temporality, space also plays a role: Although many reenactments suggest that what happened at a historical site can be relived in the present, some even mark original sites as nothing more than ‘stages’.14

In reenactments, the past must be (re)embodied by “actors.”15 Past actions and gestures are thus transferred to new bodies, which differ in physical constitution, training and body memory.16 They bring in their own memories and affects,17 as well as a specific “habitus […] particular to a time, place, and social system.”18 In addition to the reenactors, we must consider stagers and spectators.19 Between these three parties of the “aesthetic community”20 constituted in live reenactments, complex memory dynamics unfold that aim at both individual (self-)reflection and collective identity formation.21 By transforming historical events into plays, performances, choreographies or films, reenactments operate a “change of medium.”22 In particular, they add the element of an audience, which was not present at the historical event, but to whom the reenactment is addressed and who is also more or less involved in it.

Moreover, we need to distinguish the specific “mediality of reenactments” from the extent to which they “[rely] on other media in order to be transmitted, accessed, archived, and re-reenacted.”23 For many reenactments are documented in writing and/or recorded (sound recordings, photographs, film/video), i.e., translated into, and then archived and transmitted in, a mediality other than their own. Such “representation[s] of one medium in another” can be understood as cases of “remediation.”24 Astrid Erll connects this term coined by Jay Bolter and Richard Grusin with notions of a social (Maurice Halbwachs) and/or ‘image’ memory (Aby Warburg):

With the term “remediation” I refer to the fact that memorable events are usually represented again and again, over decades and centuries, in different media […]. What is known about a war, a revolution, or any other event which has been turned into a site of memory, therefore, seems to refer not so much to what one might cautiously call the “actual events,” but instead to a canon of existent medial constructions, to the narratives and images circulating in a media culture.25

Following Aleida Assmann, who understands this dynamic as actualising, but first and foremost as consolidating,26 Erll fears that remediation could amount to “stabilising certain mnemonic contents into powerful sites of memory.”27 However, remediation also has a transformative potential. Arguing with Stuart Hall, Dagmar Brunow points out that every reedition involves recontextualisation, as linguistic, transcultural and/or medial translations, but also (renewed) circulation and reception can bring about change(s).28 Remediation thus not only has the power to consolidate established canons, but also to (re)introduce elements that have been forgotten or suppressed.

Both Erll and Brunow furthermore point to the important role of audiences and “pluri-medial networks,” i.e., contextualising and framing paratexts, as well as particular constellations of production, distribution, exhibition, and reception.29 In their understanding, remediation takes place not only through new productions, but also through (re-)distribution and circulation in new contexts or through renewed reception. And that is a subtle yet crucial difference between reenactments and remediations. Reenactments are in themselves remediations (of a historical event or artwork into a new, performative/theatrical/medial setting). However, live reenactments form an ‘aesthetic community’ that is defined in terms of time, space, actors and audiences. In contrast, recorded reenactments generate ever new aesthetic communities as long as they circulate. In this way, they are able to continually reinitiate the “alternative processes of knowledge generation based on complex, collective and collaborative processes of negotiation”30 that are inherent to reenactments.31

It is precisely this dynamic between reenactment and remediation that CINE MARROCOS makes use of. Through reenacting and (re)reading preserved audiovisual traces of the first Festival do Brasil, the film aims to (re)produce audiovisual traces of what none left behind: the audiences. By restaging and recording their encounters with the films, CINE MARROCOS literally reimagines the 1954 Festival do Brasil and its meaning(s) within Brazilian and international (film) history. In the following, using the opening sequence and the first reenactment (of Ingmar Bergman’s GLYCKARNAS AFTON, SE 1953), I show how CINE MARROCOS shifts the focus from the audiovisual traces to their (re)reading. Analysing reenactments of LA GRANDE ILLUSION and SUNSET BOULEVARD, I then examine the remediations emerging between Cine Marrocos and its “documentarian mediation.”32 Through these remediations, I argue in conclusion, the film inscribes new traces in the audiovisual traces of the past and ensures that the ‘aesthetic community’ during the Marrocos’ occupation, unlike that of the festival, is not forgotten.

3. (Movie) Theatre(s) of Memory, or: (Re)Reading Audiovisual Traces

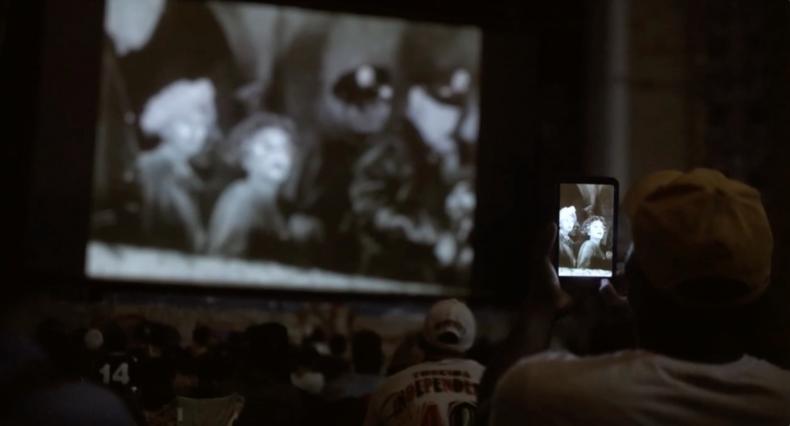

As already mentioned, CINE MARROCOS begins in a dark room. Valter Machado, one of the residents (and a stage lighting technician in his former life) lights up the space. Sitting on one of the worn cinema seats, he addresses us head-on and warns us “not to trust in me.”33 Seemingly from his perspective, and still relying on his shaky spotlight as our only source of light, we ascend a dark staircase and come across tangible traces in the form of celluloid. Suddenly, the voice of a newscaster sounds from off-screen, announcing that film stars are visiting São Paulo, which is celebrating its first film festival. The camera climbs the last steps and pans into an illuminated room. Black and white footage from 1954 then shows international stars such as Irene Dunn and Errol Flynn making their appearance at the Marrocos, then São Paulo’s largest cinema. Back in the present, we catch sight of a black square where there must once have been a screen. As the newscaster continues to list illustrious names of festival guests, we see graffiti-sprayed corridors filled with furniture, room dividers against luxurious mirrors and ceilings with rich, oriental-looking ornaments. Colour footage from the Brazilian news programme SP TV fades in and helps us understand that we actually are in the former film palace. Then we return to the audiovisual traces. The rattling sound of a film projector can be heard as the camera glides back and forth, as if examining the celluloid: Can it still/again be screened to reveal its secrets? A man takes a film strip in his hand, holds it against the light, scans individual frames. Rows of chairs are set up, a new screen is stretched, 35mm film material is wound up for projection, an audience gathers and the projector light is switched on. Finally, scenes of those films flicker (again) across the screen that were shown at this very location in 1954. But today’s audience is a different one, as we are reminded of by a smartphone filming the screen (figure 1).

This opening sequence establishes Cine Marrocos as a historical site where traces of the past are still present, waiting to be read and revived. However, past and present are separate visually (past: festival, classics, cinema palace, stars, black and white; present: film screening, projection/audience, cinema ruin, residents, colour). By showing a screen within the screen, Calil also accentuates the mediatedness and mediality of CINE MARROCOS. And it is perhaps no coincidence that on both screens we see one of the most iconic scenes in film history: that of SUNSET BOULEVARD, in which Gloria Swanson as Norma Desmond shoots her (last) close-up.

Having thus symbolically revived the remaining audiovisual traces, Calil embarks on (re)reading them with today’s audience(s). Casting-like interviews introduce some of the volunteers, and Valter explains the project:

What do I think of a crew of cinema professionals coming here at Morocco with the proposal of getting 20 residents together to do theatrical activities and to reproduce the scenes from the movies that were screened here during the film festival of 1954? Well, prepare for the criticism: research is needed. What type of research? What the locals would like to watch here and which scenes they would like to reproduce. That simple.34

Then we see a stage, where the reenactors warm up, introduce themselves and recite phrases from a song.35 An interview with (reen)actor Joseph from Nigeria, who tells the story of his escape from Boko Haram, interrupts the preparations and, in an almost Ėjzenštejnian countermovement, takes us back to the present to let the reenactor’s story flow in before we continue to approach the past.

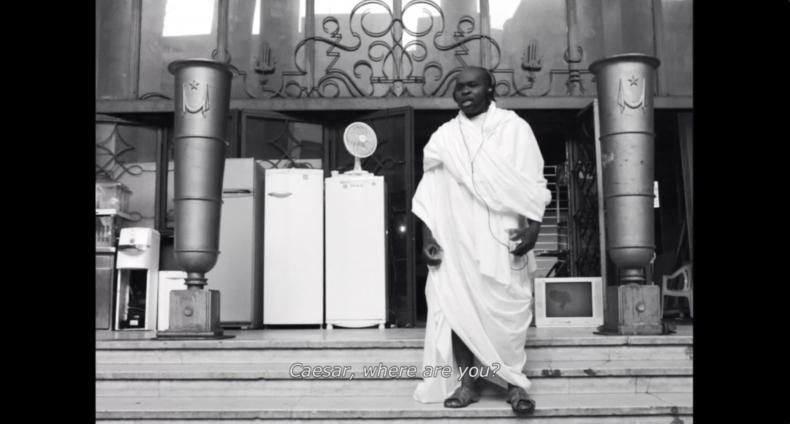

On the screen framed by the Marrocos’ orientalising ornaments, we see—as if from the perspective of the audience(s) there, then and now—a scene from GLYCKARNAS AFTON. The same scene is reenacted on stage, with Valter as Mr Sjuberg (in GLYCKARNAS AFTON: Gunnar Björnstrand) and another resident as Albert Johansson (Åke Grönberg). The dialogue is still prompted and the actors’ intonation, which fluctuates between shyness and exaggeration, indicates that they have yet to find their way into their roles. The process of restaging is again interrupted by an interview (this time with Valter) before we return to Bergman’s film, now in full screen. After a dialogue between Johansson and Sjuberg, CINE MARROCOS begins to (match-)cut back and forth between GLYCKARNAS AFTON and its reeenactment, filmed in black and white ‘just like the original’. Despite an improvised costume, Valter is still recognisable, and immediately after the reenactment he steps out of his role, thanking his co-star and reflecting on the costume that makes him “arrogant.”36 But although we are thus back in the ‘diegetic present’, the image remains in black and white, as if the past still reverberates until, after another cut, a new rehearsal begins (see figures 2 and 3).

This interweaving of rehearsals, original scenes, (filmed) reenactments, and documentary interviews continues through the entire film. Little by little, we get to know the (reen)actors: Besides Joseph, Panda, a journalist from the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Yamaya from Senegal also came to Brazil as refugees. Volusia, like Valter, ended up on the streets after suffering from severe depression. Tatiane, who came out as queer, and Fagner, actually the son of an estate agent, fled family conflicts, and Dulcelina from an abusive marriage. What all have in common is that they are marginal figures of Brazilian society. Unlike the film stars whose roles they take on, they are not in the limelight, nor are they celebrated by the Brazilian media.37 If they were indeed allowed to choose which scenes they wanted to reenact, some may therefore have deliberately chosen ‘foreign’ films or characters that offered them a certain self-protection. Tatiane, for example, chose the circus rider Anne (Harriet Andersson) from GLYCKARNAS AFTON: like Tatiane as a Muy Thai boxer, Anne also tries to live from her sporting talent; at the same time, unlike Tatiane, Anne is heterosexual. And Dulcelina distances herself from her failed marriage by reenacting ‘La Bersagliera’ (Gina Lollobrigida) from PANE, AMORE E FANTASIA (Luigi Comencini, I 1953), a female character who ends up in a happy marriage. “In these situations, contemporary bodies stand in for formerly living bodies, asking questions of the past from the vantage point of the present. But no body, whether past or present, is a tabula rasa […].”38 Through the process of reembodying and reenacting, the audiovisual traces of the 1954 Festival do Brazil and the (film) history they refer to are thus not only (re)read, but also rewritten.

4. From Cine Marrocos to CINE MARROCOS

By translating the live reenactments into a cinematic mediality, CINE MARROCOS contributes to this process and sets in motion a chain of additional remediations. Panda, for example, takes on the role of Lt. Maréchal (Jean Gabin) from LA GRANDE ILLUSION, who becomes a prisoner of war in Germany during World War I and is isolated from other Frenchmen. During rehearsals, Panda initially plays this part in English: “I wanna escape this place. I can’t live in this place. I don’t want to stay in this place. This place is stinking of shit. I cannot stand this place. I cannot stand this place anymore. [...] I want to hear some voice... I want to hear some French accent.”39 But instead of repeating as prompted, Panda ends with: “I want to hear some French – action out.”40 For a brief moment, we see him staring into space. The camera begins to move around him and a short, soft touch of a piano keyboard sounds from off-screen, as if to underline this moment and at the same time expose it in its stagedness. After a cut, the previously rehearsed scene from LA GRANDE ILLUSION follows in full screen, and again the filmed reenactment is inserted through match cuts. But Panda now speaks in some other language and adds to Gabin’s statement “There is no voice”: “There is no voice in Congo.”41

Compared to LA GRANDE ILLUSION, Panda’s monologue differs slightly already during rehearsals. Through the renewed change of language, however, the reenactment filmed and edited into CINE MARROCOS achieves a more profound remediation: The past of Renoir’s and Gabin’s scene (World War I, captivity of a Frenchman in Germany) is short-circuited with the present of Cine Marrocos (poverty, isolation from society), as well as with the past (armed conflicts in the Congo) and present of Panda (life as a political refugee in Brazil). The reenactment and its cinematic remediation thus open LA GRANDE ILLUSION to transcultural memory, with Yamaya’s statement at the end of the scene, “This war is going on for too long,” taking on unexpected ambiguities.42

Another example is the reenactment of SUNSET BOULEVARD by Volusia. Like the aged and forgotten silent film diva Norma Desmond, Volusia, once a model and dance teacher with her own studio, has lost everything due to severe depression. During rehearsals, Volusia speaks the monologue in Portuguese and struggles with the correct pronounciation of the word “close-up” in Norma’s famous last sentence. While repeating the prompted words, she constantly seeks the reassuring gaze of the others. But as she speaks “This is my life. And it always will be,”43 Volusia’s facial expressions, gestures, and intonation suddenly seem more convincing. And precisely at this point, CINE MARROCOS again comments what is happening on stage: For a brief moment, the camera loses focus and the image becomes blurred, as if to emphasise the increasingly blurred boundaries between Volusia and Norma.

Unlike before, we do not see the filmed version of Volusia’s reenactment immediately afterwards. Instead, we see further rehearsals and reenactments, as well as Vlad, the leader of the homeless workers’ movement occupying the Marrocos, who announces that the city council has decided to evict the building. From this point on, the Marrocos’ past, present and future intersect in ever more complex ways. Weddings and birthdays are celebrated; rehearsals and filming continue. But a reenactment of Julius Caesar being stabbed (JULIUS CAESAR, Joseph L. Mankiewicz, US 1953) is followed by footage of a newscast, announcing that Vlad has been arrested for drug trafficking and that his movement has enriched itself from the residents. Leaving it up to audiences to decide what to believe, Yamaya delivers Marcus Antonius’ eulogy of Caesar as a self-written rap song (see figures 4–7). While Yamaya thus ‘speaks to the people’, he stands on the same entrance stairs that we saw the film stars striding up earlier. However, Yamaya and the other ‘stars’ of CINE MARROCOS are not facing a cheering crowd of fans: They are facing a crowd of uniformed policemen preparing to evict them.

While dustmen are beginning to clean the building, Valter recites from “Saudosa Maloca,” a melancholy samba tune from 1961,44 which could just as well have described the scenes taking place at the Marrocos. The residents then move on into an uncertain future. Shots that must have been taken immediately after the eviction show the abandoned building, as if to capture this moment on film, writing new traces for future audiences. On the screen of a camera, we see filmmaker Calil addressing his star, “Are you ready, Norma?”45 (figure 8). This is ‘answered’ by Gloria Swanson/Norma, but the command “Action,” is executed by Volusia, who descends a staircase in front of a graffiti-covered wall in the Marrocos. As with Maréchal, Norma Desmond’s last words thus take on an unexpected ambiguity: “After Salome, I will make another picture and another picture. This is my life. Me, the cameras and those wonderful people out there in the dark.”46

With this final montage, CINE MARROCOS turns the end of the aesthetic community in the Marrocos—which, unlike that of the 1954 festival, did not end in a self-determined way—into (potential) new beginnings. These new beginnings, however, require the ‘wonderful people out there in the dark.’ In them, the viewers of CINE MARROCOS at other film festivals,47 traces and memories of the Marrocos and its ‘stars’ live on:

[…] The theatre as a place of memory is […] a formerly inhabited place [...]. When the show ends, the old order is forgotten and we are left alone with the memory of the present beings who, by fading away, pass to the side of the ghost who, tomorrow, will come to circulate in the intimacy of the living […].48

5. Conclusion

In this article, I have explored what audiovisual traces a film festival leaves behind and how we can share and pass them on. As an example, I used the documentary CINE MARROCOS, which examines precisely these questions. In its particular case—the 1954 Festival do Brasil—traces were indeed left behind: footage of illustrious festival guests and copies of the films shown, but also less obvious traces that required audiovisual memory work through (filmed) reenactments and remediations.

In reenactments, past events are “relived, revived, and refashioned”49 by performers and audiences alike. But reenactments are never neutral ‘repetitions’. They are also ‘reassemblages’ and can enter into further remediation processes through recording, circulation and reception. Archived, they provide future generations with information about how previous generations (re)imagined the past and can become the subject of new reenactments and remediations. It is precisely this dynamic of cultural memory that CINE MARROCOS exploits: By reenacting and thus rewriting the audiovisual traces that still exist, it creates new ones for later generations to (re)read.

In doing so, CINE MARROCOS intervenes in Brazilian (film) history in a way that at first glance looks like what Raphael Samuel calls „a matter of improving on the original by installing, in replica and facsimile, what ought to be there but is not.”50 For the audiovisual traces that have survived from 1954 carry traces of problematic power relations. They show what was the focus of attention at the time (international film stars, heteronormative figures, white European perspectives on World War I), and thus also hold up a mirror to contemporary film festivals and their programming. Yet in many traces, not only “the clearly perceptible [...] is inscribed, but also the barely perceptible.”51. By remediating these traces of the ‘barely perceptible’, CINE MARROCOS brings to the centre what was peripheral in 1954 and contributes to opening up Western-dominated canons of film history to multidimensional processes of transcultural memory.

It is perhaps no coincidence that CINE MARROCOS bases this endeavour on a (former) movie theatre, “one of the most powerful ‘theatres’ available to a memory in motion.”52 The film repeatedly puts us in the place of the audiences in the Marrocos, now and then. At the same time, we are made aware of our role as spectators of CINE MARROCOS. It also seems as if Norma Desmond speaks the same complicit words to those (re)gathering in the Marrocos as Volusia does to us, the audiences gathered in front of MARROCOS. In this way, the film makes us aware of our own role and power in the (movie) ‘theatre of memory’ of film history, as well as of our responsibility as readers and (re)producers of old and new audiovisual traces.

- 1Anja Dreschke, Ilham Huynh, Raphaela Knipp, and David Sittler, “Einleitung,” in Reenactments: Medienpraktiken zwischen Wiederholung und kreativer Aneignung, ed. Anja Dreschke, Ilham Huynh, Raphaela Knipp, and David Sittler (Bielefeld: transcript, 2016), 11. My translation from German: “performative Mobilisierung der Spurenträger.”

- 2The footage featured in the film is limited to two newsreels, identified in the credits as “Sao Paulo Brazil Film Festival (1954)” (Newsreel Associated Press © Easy Street Productions, LLC) and “Bandeirantes na tela N.611“ (Cinemateca Brasileira).

- 3cf. Rafael Morato Zanatto, “O I Festival Internacional de Cinema do Brasil (1954),” Aniki 8, no. 1 (2021): 101–130, https://doi.org/10.14591/aniki.v8n1.728. Zanatto also shows how the conception of the festival was influenced by European models and outlines the cultural-political considerations underpinning the section “Grandes Momentos do Cinema” and the “Retrospective Erich von Stroheim,” in which mainly European and Western productions were shown (ibid., 103–106 and 109–116).

- 4Aleida Assmann, “Canon and Archive,” in Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, ed. Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2008), 101.

- 5Ulf Otto, “Gesten des Anachronismus. Theatrale Medienpraktiken im Reenactment,“ in Reenactments, ed. Dreschke et al., 171. My translation from German: “körperliche Aneignung historischer Bilderwelten.”

- 6Esther Buss, “Cinema Morocco,“ DOK Leipzig – International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film, accessed September 28, 2021, https://www.dok-leipzig.de/en/film/20181358/cinema-morocco.

- 7Dagmar Brunow, Remediating Transcultural Memory: Documentary Filmmaking as Archival Intervention (Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 2015), 49.

- 8Building on Manuel Zahn’s concept of film reception as the reading of traces (“Spurenlesen,” Ästhetische Filmbildung: Studien zur Materialität und Medialität filmischer Bildungsprozesse (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012), 91–109), I assume here that in CINE MARROCOS, both on the part of the production and through our reception, not only existing traces are followed and investigated, but also (new) traces are laid (“Spurenlegen”).

- 9Dreschke et al., “Einleitung,“ 10.

- 10See for example Gerald Sieber, Reenactment: Formen und Funktionen eines geschichtsdokumentarischen Darstellungsmittels (Marburg: Schüren, 2016), 112–113; Annemarie Matzke, “Bilder in Bewegung bringen. Zum Reenactment als politischer und choreografischer Praxis,” in Theater als Zeitmaschine, ed. Jens Roselt and Uwe Otto (Bielefeld: transcript, 2012), 128–130.

- 11Erika Fischer-Lichte, “Die Wiederholung als Ereignis. Reenactment als Aneignung von Geschichte,” in Theater als Zeitmaschine, ed. Roselt and Otto, 14 and 45.

- 12Peter Burke, ”Co-memorations. Performing the past,” in Performing the Past: Memory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe, ed. Karin Tilmans, Jay M. Winter, and Frank van Vree (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010), 106.

- 13Stella Bruzzi, “Documentary,” in The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies: Key Terms in the Field, ed. Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb, and Juliane Tomann (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 49 and 51; see also Matzke, “Bilder in Bewegung,” 128–129.

- 14Burke, ”Co-memorations,” 115.

- 15Ibid., 108.

- 16Matzke, “Bilder in Bewegung,” 126.

- 17Jay M. Winter, “The Performance of the Past: Memory, History, Identity,” in Performing the Past, ed. Tilmans et al., 11–12.

- 18Amanda Card, “Body and Embodiment,” in The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies: Key Terms in the Field, ed. Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb, and Juliane Tomann (London and New York: Routledge, 2020), 31.

- 19cf. Burke, ”Co-memorations,” 116.

- 20Fischer-Lichte, “Wiederholung als Ereignis,” 48 (“ästhetische Gemeinschaft”). Fischer-Lichte also refers to the concepts of “aesthetic communities” (Gianni Vattimo) and “imagined communities” (Benedict Anderson), both of which suggest that communities constituted in the context of a live event can be transferred into a more permanent form or revived on the basis of memories, affects and/or media.

- 21Jens Roselt and Uwe Otto, “Nicht hier, nicht jetzt. Einleitung,” in Theater als Zeitmaschine, ed. Roselt and Otto, 10. See also Fischer-Lichte, “Wiederholung als Ereignis,” 48; Burke, “Co-memorations,” 108; Winter, “Performance of the Past,” 1 and 15.

- 22Roselt and Otto, “Einleitung,” 10 (“Medienwechsel”).

- 23Maria Muhle, “Mediality,” in The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies: Key Terms in the Field, ed. Agnew et al., 133.

- 24Bolter, Jay M. and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000), 45.

- 25Erll, Astrid, “Literature, Film, and the Mediality of Cultural Memory,” in Cultural Memory Studies, ed. Erll and Nünning, 392.

- 26Assmann, “Canon and Archive,” 100–102.

- 27Erll, Astrid, Memory in Culture (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 143.

- 28Brunow, Remediating Transcultural Memory, 49–50.

- 29Erll, “Mediality of Cultural Memory,” 395–396; Brunow, Remediating Transcultural Memory, 49–51.

- 30Dreschke et al., “Einleitung,“ 13. My translation from German: „alternative Verfahren der Wissensgenerierung [...], die auf komplexen, kollektiven und kollaborativen Aushandlungsprozessen basieren.“

- 31Rebecca Schneider further elaborates on this with a particular focus on theatre in chapter 3 of her monograph Performance Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment (London: Routledge, 2011), 87–110.

- 32Muhle, “Mediality,” 134.

- 33CINE MARROCOS, 00:01:46. Throughout the film, Valter plays a more prominent role than the other residents. This passage serves to establish him as a kind of trickster who sometimes seems to speak on behalf of the filmmaker and sometimes on behalf of the residents.

- 34CINE MARROCOS, 00:07:04-00:07:42.

- 35The song “Nine Out of Ten,” written in 1972 by Caetano Veloso during his political exile in London, praises emotions that films and their stars can evoke, making us feel ‘alive’ even in difficult times (“Nine out of ten movie stars make me cry/I am alive”). The song is recited again and again during the rehearsals at the Marrocos and also accompanies the end credits of CINE MARROCOS, presenting the reenactors as ‘movie stars’ themselves.

- 36CINE MARROCOS, 00:18:32.

- 37On the contrary, Brazilian media such as SP TV either criminalise the Marrocos’ residents by associating them with drug smuggling, or victimise them by describing the homeless workers’ movement as a mafia-like structure that even extracts rent from them for their poor accommodation

- 38Card, “Body and Embodiment,” 30.

- 39CINE MARROCOS, 00:50:21–00:50:41.

- 40CINE MARROCOS, 00:50:42.

- 41CINE MARROCOS, 00:52:04.

- 42As Philipp Scheffner’s documentary THE HALFMOON FILES (D 2007) shows on the basis of sound recordings made in the so-called Half Moon Camp near Berlin, during World War I, soldiers from the colonies who fought in the French army also became German prisoners of war. LA GRANDE ILLUSION largely omits this part of history, except for a minor character called “the Senegalese” (Habib Benglia), who audiences familiar with Renoir’s classic might feel reminded of here.

- 43CINE MARROCOS, 00:22:47.

- 44Adoniran Barbosa, who composed this tune, was one of the first samba musicians to use the language spoken by working classes and poor people. In English translation the lyrics read: “If you don't remember/That here where you are now/That tall building/Was once an old house […]/It was here […]/That[…]/We built our shed/One day I don’t even want to remember/The men came with their tools/The owner ordered them to demolish/We took all our things/And we smoked in the middle of the street/To enjoy the demolition.”

- 45CINE MARROCOS, 01:10:37.

- 46CINE MARROCOS, 01:11:42–01:11:59.

- 47CINE MARROCOS has been screened at several film festivals, including DOK Leipzig in Germany, Festival Internacional de Cine en Guadalajara, Mexico, and É Tudo Verdade in São Paulo.

- 48Georges Banu, “Le théâtre, lieu de mémoire,” in Traverses 40 (Éditions du Centre Georges Pompidou, 1987), 116. My translation from French: “Approcher le théâtre comme lieu de mémoire c’est d’abord l’approcher comme lieu anciennement habité […]. Quand le spectacle s’achève, l’ordre ancien s’oublie et nous laisse seuls avec le souvenir de ces êtres présents qui, en s’évanouissant, passent du côté du fantôme qui, demain, viendra circuler dans l’intimité des vivants.”

- 49Winter, “Performance of the Past,” 11.

- 50Raphael Samuel, Theatres of Memory (London: Verso, 1995), 172.

- 51Sybille Krämer, “Was also ist eine Spur? Und worin besteht ihre epistemologische Rolle? Eine Bestandsaufnahme,” Spur: Spurenlesen als Orientierungstechnik und Wissenskunst, ed. Sybille Krämer, Werner Kogge, and Gernot Grube (Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2007), 14. My translation from German: “nicht nur das deutlich Wahrnehmbare […] eingeschrieben, sondern ebenso das kaum Wahrnehmbare – situiert am Rande seiner Unmerklichkeit.”

- 52Christa Blümlinger, Michèle Lagny, Sylvie Lindeperg, François Niney, and Sylvie Rollet, “Avant-propos,” in Théâtres de la mémoire: Mouvement des images, ed. Christa Blümlinger, Michèle Lagny, Sylvie Lindeperg, François Niney, and Sylvie Rollet (Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2011), 9. My translation from French: “le cinéma ouvre l’un des plus puissants « théâtres » qui s’offrent à une mémoire en mouvement.”

Assmann, Aleida. “Canon and Archive.” In Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, edited by Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning, 97–107. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2008.

Banu, Georges. “Le théâtre, lieu de mémoire.” Traverses 40 (Éditions du Centre Georges Pompidou, 1987): 115–123.

Blümlinger, Christa, Michèle Lagny, Sylvie Lindeperg, François Niney and Sylvie Rollet. “Avantpropos.” In Théâtres de la mémoire: Mouvement des images, edited by Christa Blümlinger, Michèle Lagny, Sylvie Lindeperg, François Niney, and Sylvie Rollet (Paris: Presses Sorbonne Nouvelle, 2011), 5–9.

Bolter, Jay M. and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2000.

Brunow, Dagmar. Remediating Transcultural Memory: Documentary Filmmaking as Archival Intervention. Berlin/Boston: De Gruyter, 2015.

Bruzzi, Stella. “Documentary.” The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies: Key Terms in the Field, edited by Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb, and Juliane Tomann, 49–52. London/New York: Routledge, 2020.

Burke, Peter. ”Co-memorations. Performing the Past.” In Performing the Past: Memory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe, edited by Karin Tilmans, Jay M. Winter, and Frank van Vree, 105–118. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

Buss, Esther. “Cinema Morocco.” DOK Leipzig – International Leipzig Festival for Documentary and Animated Film. Accessed September 28, 2021. https://www.dokleipzig.de/en/film/20181358/cinema-morocco.

Card, Amanda. “Body and Embodiment.” In The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies: Key Terms in the Field, edited by Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb, and Juliane Tomann, 30–33. London/New York: Routledge, 2020.

Dreschke, Anja, Ilham Huynh, Raphaela Knipp and David Sittler, eds. Reenactments: Medienpraktiken zwischen Wiederholung und kreativer Aneignung. Bielefeld: transcript, 2016.

Erll, Astrid. “Literature, Film, and the Mediality of Cultural Memory.” In Cultural Memory Studies: An International and Interdisciplinary Handbook, edited by Astrid Erll and Ansgar Nünning, 389–398. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2008.

Erll, Astrid. Memory in Culture. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Fischer-Lichte, Erika. “Die Wiederholung als Ereignis. Reenactment als Aneignung von Geschichte.” In Theater als Zeitmaschine: Zur performativen Praxis des Reenactments, edited by Jens Roselt and Uwe Otto, 13–52. Bielefeld: transcript, 2012.

Krämer, Sybille. “Was also ist eine Spur? Und worin besteht ihre epistemologische Rolle? Eine Bestandsaufnahme.” In Spur: Spurenlesen als Orientierungstechnik und Wissenskunst, edited by Sybille Krämer, Werner Kogge, and Gernot Grube, 11–33. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 2007.

Matzke, Annemarie. “Bilder in Bewegung bringen. Zum Reenactment als politischer und choreografischer Praxis.” In Theater als Zeitmaschine: Zur performativen Praxis des Reenactments, edited by Jens Roselt and Uwe Otto, 125–139. Bielefeld: transcript, 2012.

Muhle, Maria. “Mediality.” In The Routledge Handbook of Reenactment Studies: Key Terms in the Field, edited by Vanessa Agnew, Jonathan Lamb, and Juliane Tomann, 133–137. London and New York: Routledge, 2020.

Otto, Ulf. “Gesten des Anachronismus. Theatrale Medienpraktiken im Reenactment.“ In Reenactments: Medienpraktiken zwischen Wiederholung und kreativer Aneignung, edited by Anja Dreschke, Ilham Huynh, Raphaela Knipp, and David Sittler, 167–189. Bielefeld: transcript, 2016.

Roselt, Jens Roselt and Uwe Otto. “Nicht hier, nicht jetzt. Einleitung.” In Theater als Zeitmaschine: Zur performativen Praxis des Reenactments, edited by Jens Roselt and Uwe Otto, 7–11. Bielefeld: transcript, 2012.

Samuel, Raphael. Theatres of Memory. London: Verso, 1994.

Schneider, Rebecca. Performing Remains: Art and War in Times of Theatrical Reenactment. London: Routledge, 2011.

Sieber, Gerald. Reenactment: Formen und Funktionen eines geschichtsdokumentarischen Darstellungsmittels. Marburg: Schüren, 2016.

Winter, Jay M. “The Performance of the Past: Memory, History, Identity.” In Performing the Past: Memory, History, and Identity in Modern Europe, edited by Karin Tilmans, Jay M. Winter, and Frank van Vree, 11–31. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2010.

Zahn, Manuel. Ästhetische Filmbildung: Studien zur Materialität und Medialität filmischer Bildungsprozesse. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2012.

Zanatto, Rafael Morato. “O I Festival Internacional de Cinema do Brasil (1954).” Aniki 8, no. 1 (2021): 101–130. https://doi.org/10.14591/aniki.v8n1.728.