The Authenticity Feeling

Language and Dialect in the Historical Film

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Frey, Mattias: The Authenticity Feeling: Language and Dialect in the Historical Film. In: Research in Film and History. New Approaches (2018), pp. 1–48. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14811.

1The pursuit of authenticity is film’s dominant mode of historical representation. For the overwhelming majority of historical film makers and audiences, authenticity signifies a realistic historical experience, an effective suspension of temporal-spatial disbelief. Authenticity, as the engine of mainstream historical filmmaking, has three chief functions: as an aesthetic strategy, a reception discourse and a marketing discourse. A feeling, a form of perception and (supposed) knowledge, the aesthetic success of authenticity, and thus the mainstream historical film, is assessed via the following question: Has the past been conveyed in a way that the spectator can reconcile with his or her perception of the historical reality? Audiences speak of films that “bring history to life”.2 I call this condition – this sensation of a media-produced, purportedly successful historicity – the ‚authenticity feeling‘.

To be sure, authenticity and the authenticity feeling are products of particular domains and styles of representation, including costume and music. Precisely because authenticity remains, among many audiences and critics, the most important benchmark in the evaluation of historical filmmaking, however, it must be understood and examined as a chief characteristic of marketing and reception discourses. Interviews with actors, directors and other film personnel, advertising campaigns and Making Of featurettes frequently and consistently refer to the quantity and quality of pre-production historical research. The producers of ZODIAC (David Fincher, USA 2007), we learn for example, used helicopters and cement to plant trees on a barren California island in order to precisely reconstruct a murder scene due for a mere smattering of shooting days. On the ‚San Francisco Chronicle‘-set, production designers sourced painstakingly elaborate replicas of every page of each day’s newspaper, even though they never appear on camera. Such meticulous forms of realism, the prop master Hope M. Parrish explains in the Making Of, help the actors slip into their roles. The screenwriter and other personnel justify this obsessive degree of historical reconstruction with auteurist appeals: according to them, David Fincher is no mere perfectionist, but above all the consummate, uncompromising artist, and the pursuit of visual authenticity represents a sort of method acting for sets, props and locations. (Fincher himself never speaks; the production designer, costume designer and make-up artist admire him from the distance as talking heads.) Furthermore, and above all in recreating instances of human suffering – ZODIAC revolves around a serial killing spree in northern California in the late 1960s – filmmakers appeal to a sense of moral duty to stay as close as possible to known and knowable facts, as a gesture of respect to the victims. This is certainly not a phenomenon restricted to the CGI-era. Film historians such as George Custen register exemplary 1930s Cecil B. DeMille productions by which authenticity essentially shapes both aesthetics and marketing.3

Authenticity has been and remains the most prominent element in historical films’ reception discourse. Scholars never tire to explain the extent to which historians, critics and lay audiences evaluate historical films according to the meter of “accuracy and authenticity.” 4 Above all, critical reviews and academic articles seek to clarify the extent to which the film corresponds to the “real events” and “official records”. Ridiculed and rejected by film scholars as the “fidelity discourse”, this approach considers the film as the reflection of an already existent and indisputably superior description of reality. As Jonathan Stubbs opines, “achievement in the historical film genre is often judged according to the perception of historical accuracy rather than by aesthetic criteria.”5

The impression of authenticity, and the warm, righteous feeling it catalyses, fundamentally shape the reception of historical films, particularly among lay audiences. There is no shortage of sources which report that in BRAVEHEART (Mel Gibson, USA 1995), set in thirteenth-century Scotland, a white van and a man with a baseball cap can be seen, or that in GLADIATOR (Ridley Scott, USA 2000) a gas bottle appears in the back of a Roman chariot.6 IMDb maintains categories for goofs and anachronisms so that users can, for example, flag up and discuss the extras in SPARTACUS (Stanley Kubrick, USA 1960) who wear a wrist watch.7 The American humour magazine Cracked asked its readers to upload the “most glaring mistakes” in film onto a webpage that eventually attracted over 1.5 million hits. Most users – and the winners of the competition – highlighted errors in period films. Among them: Jack, protagonist of TITANIC (James Cameron, USA 1997) supposedly comes from a town in Wisconsin that in reality was founded five years after his death. RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK (Steven Spielberg, USA 1981) depicts a German military operation in Egypt that is not only invented, but also, because of the British occupation during the period, would have been impossible. In a BACK TO THE FUTURE (Robert Zemeckis, USA 1985) scene meant to be set in 1953, Marty (Michael J. Fox) plays a Gibson ES335 guitar, a model that was not sold until three years later.8 A fan culture that collects and disseminates such continuity errors exists among blogs, forums, Wikipedia entries, YouTube videos and books, which serve this culture and its interests.9As we shall see, empirical studies demonstrate that, for a significant proportion of audiences, the search for “mistakes” and the engagement with the details of the historical mise-en-scène represent the “pleasure”, “source of active enjoyment” and “most important motivation” for the consumption of historical films.10

Authenticity is, for it many proponents, ultimately a felt, sensual, even embodied historicity: the authenticity feeling. Its detractors belittle authenticity as historicism, an arduous yet naïve representational form and artistic habitus that attempts to approach the past in an uncritical and affirmative manner. In this article I seek to disrupt the critical consensus and propose two main arguments. First, authenticity, as an aesthetic strategy, and the authenticity feeling, as a measure and characteristic of reception, are important social phenomena that must be considered more closely and dissected more systematically. Second, sound – and above all language and dialect – plays an essential and hitherto little studied part in the production of the authenticity feeling. In order to write an Audio History of Film, it is essential to better understand the authenticity feeling; only via a rigorous analysis of the historical film’s acoustic elements can one comprehend authenticity as a marketing discourse and means of reception.

Authenticity Criticism

Today, there are many critics who write lengthy, often embittered condemnations of filmmakers’ authenticity efforts. According to the opinion of Katja Nicodemus (Die Zeit), there should be a “multiyear prohibition . . . for the one street used as a historical location at the Babelsberg studio”.11 Alluding to Walter Benjamin, Nicodemus ridicules contemporary German historical films and their “deeply museal engagement with their visual representation” as whores in the bordello of historicism: “it seems as if the German cinema, with its prop-schlepping, its over-enthusiastic recreators . . . has fooled around with precisely this historical whore”. Nicodemus is hardly alone in her critique of the “parasitic shamelessness of the German nostalgia film”. According to taz-critic Cristina Nord, it suffices these days “when the license plate in the film matches the one in real life”. Indeed, if “there is anything resembling a program” among these films, “it expresses itself in the fetishisation of authenticity”. The aesthetic focus on historical details, according to Nord, is part and parcel of a “new naïveté”.12

Such opinions are not only widely held among German film critics. The former NYU professor Robert Sklar criticised THE BAADER MEINHOF COMPLEX (DER BAADER MEINHOF KOMPLEX, Uli Edel, D 2008) in a similar way: “Its idea of interpreting the past is to try to match on screen the same number of bullets that were expended in the actual event”.13 Directors such as Romuald Karmakar, Christian Petzold and Andres Veiel complain about “stylisation of the past”, a “historical over-consolidation that is simply disgusting”. They reject the attempts of productions such as THE MIRACLE OF BERN (DAS WUNDER VON BERN, Sönke Wortmann, D/A 2003) GOOD BYE, LENIN! (Wolfgang Becker, D 2003) and DOWNFALL (DER UNTERGANG, Oliver Hirschbiegel, D 2004) for wanting to “end history with a full stop”.14 In (conscious or unconscious) reference to Linda Williams’ definition of pornography (a genre that above all aims for “maximum visibility”), some “Berlin School” filmmakers speak of “history porn” when describing such films.15Authenticity criticism is an international phenomenon with a long pre-history: film scholars such as Stubbs refer to the tradition of leftist critique of historical films, which are supposedly too preoccupied with costumes and detailed mise-en-scène.16

The most well-known instance of authenticity criticism took place in the context of the 1990s “heritage film” debate. Andrew Higson delivered the most prominent contributions in his various publications on the British costume dramas of the 1980s and 1990s.17 Higson describes the “discourse of authenticity” thus: “the desire to establish the adaptation of a heritage property (whether conceived as historical period, novel, play, building, personage, décor, or fashion) as an authentic reproduction of the original”.18 Revealingly, this formulation foregrounds the relationship between original and copy: historical films and their production processes function essentially as adaptations. Measured in this way, historical films suffer from the traditional status of reproduction (in the history of art and otherwise): second-rate fakes that prey on the original in order to appropriate the latter’s reputation. Authenticity criticism places historical films under the general suspicion of being no more than leeches:

One central representational strategy of the heritage film is the reproduction of literary texts, artefacts, and landscapes which already have a privileged status within the accepted definition of the national heritage.19

According to Higson, heritage films cling to the cultural capital of written historiography as well as that of documents, artefacts or monuments.

The authenticity critics involved in this debate judged heritage films in often caustic terms. For Richard Dyer and Ginette Vincendeau – who extended the British discussion to contemporary Continental period productions – heritage films are “characterised above all by a museum aesthetic”, maintaining an “apparently meticulous period accuracy, but clean, beautifully lit, and clearly on display”.20 Indeed, in the course of the debate, the films were often accused of an “aesthetic of display”. According to these commentators, the productions seek to configure unreflective ‚Heimat‘ fantasies with a fixation on the mise-en-scène, e.g., with lighting, cinematography and editing that emphasise the detailed reconstruction of costumes. Moreover, they claim, this stylisation serves to represent, and thus glorify, the upper classes. Implicitly and explicitly, the scholars and critics attempt to yoke the “conservative” aesthetic together with conservative politics and, furthermore, a conservative audience.

It is important to emphasise that the heritage-film authenticity critics analyse their objects of inquiry in a ‚normative‘ way. Professor, newspaper columnist or blogger alike: all commentators thematise the productions as a means to criticise them. In the opinion of Claire Monk, the heritage film is therefore not a genre in the conventional sense, but rather a kind of warning label:

the construction of the idea of the ‘heritage film’ is interesting for its entanglements of political criticisms with a gut-level cultural aesthetic aversion to the films on the part of its many critics.21

To my mind this vehement antipathy towards the historical film – a culturally contingent, sociologically decipherable curiosity of the history of taste – inhibits a productive engagement with an Audio History of Film. Elsewhere, I refer to the weaknesses of such authenticity criticism. For instance, critics dismiss the productions out of hand, without undertaking differentiated analyses of individual examples or accounting for unique historical receptions; they suspect (erroneously) that the films appeal mainly to women, gays and/or conservatives, a problematic assumption that reveals suspicions of “visual pleasure”.22

In the context of this study of Audio History, however, new insights are necessary. First of all, it is important to note the authenticity critics’ fixation on visual elements. For example, Nicodemus discusses problems with the “visual representation”, the “picture”, “Grandpa’s ‚Wehrmachtsuniform‘ and discarded disco balls”, the “Technicolor aesthetic”, or the “typical brown-beige patina of the German coming-to-terms-with-the-past film”, i.e., props, costumes, production design and their ‚visual‘ representation. The one single exception – Nicodemus mentions her dismissive attitude towards “violin excesses” – proves the rule.23 The critics of the “new naïveté” and “history porn” seem to have few problems with any “maximum audibility”, in other words, the engagement with sound. Is there less to criticise about the concerted search for and detailed rendering of sound, than there is regarding the production design? Or is this aspect neglected by the makers of historical films and can thus, according to the logic of these commentators, be ignored in such critiques? As the lengthy discussion of dialect, music and so on in this chapter demonstrates, at least the second question can be answered in the negative.

Second, both the authenticity discourse, in general, and authenticity criticism, in particular, are important symptoms for the considerable cultural importance of filmic historiography: feelings run high. The laborious aesthetic, the extensive reports on the effort and money expended in this process in marketing discourses, as well as critics’ furious objections demonstrate clearly how much remains at stake. Historical films are not seldom national issues. The press detailed how the US President Barack Obama “teared up” while watching THE BUTLER (USA 2013).24 German Federal Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, cabinet ministers, the Hungarian ambassador and the Swiss general consul attended the premiere of THE MIRACLE OF BERN in Essen. The chancellor, who had a public persona as a macho, had already seen the rough cut of the film in his official residence in Berlin and admitted having had cried three times.25 Historical films are among the most frequently screened audiovisual media in classrooms. The Federal Agency for Civic Education has published teaching materials so that German history teachers and foreign teachers of the German language can use generic exemplars to convey postwar German history.26

These are dramatic fiction films, but also so much more. The debates surrounding historical authenticity are aesthetic questions about representation, but ultimately ontological questions about the essence of the historical film and its identitarian functions. Commentators contest ‚how‘ history should be best and most credibly represented, but they also seek to resolve a deeper dilemma: If history is represented in this particular way, ‚who‘are we? The focus on authenticity in marketing discourses is surely a strategy to foreclose a negative reception via reports of extensive and time-consuming research. The authenticity discourse attempts to veil and prevent aesthetic judgments: “It’s just a film” and “That’s how it really was”, when spoken by filmmakers or historical witnesses become indisputable (if contradictory) responses to any criticism. The deafening noise that is the authenticity discourse drowns out more subtle, subjunctive and counterfactual questions about form, effect, affect and audience engagement. How ‚could‘ history have been best conveyed, in this case? Did the spectator understand the larger implications of the representations? ‚What‘ did he or she understand?

Nevertheless, authenticity critics – reviewers as well as many historians and film scholars27 – ignore the significant resonance of authenticity in popular discourse: the historical film remains one of the most popular and successful film genres.28 An Adornian argument – i.e., that audiences only engage with or expect “authentic” costumes or dialects because they unconsciously reproduce media discourses – would be, in my opinion, an insufficient explanation of this phenomenon. Human beings have a sensual need and instinctive desire for credible historical experiences. Initial empirical studies demonstrate, for example, how spectators assume various expectations and demands for “truth” and “accuracy” depending on whether the film was marketed as a historical film and whether the film depicts well-known historical figures and events.29 Following this principle, for instance, the demand for authenticity would be greater for LINCOLN (Steven Spielberg, USA 2012) than for MOULIN ROUGE! (Baz Luhrmann, AUS/USA 2001), even if strictly speaking both are historical films. Such audience desires must be taken seriously and studied in a differentiated manner – ‚why‘ and ‚for whom‘ are they important? – rather than simply rejecting them as “disgusting” or “naïve”.

Indeed, authenticity criticism tends towards simplified explanations and characterisations of the productions themselves, the filmmakers who deliver them, and the implied audiences that consume them. Even exemplars that do not fetishise production design, costumes and narrative details (whether in the film itself or in the surrounding discussions) cannot simply do away with such details. After all, such details – whether anachronistic clothing, specific means of speaking, music and others sounds from the depicted period, historical figures or written references to past dates – are necessary to cue audiences to recognise the films as ‚historical‘ in the first place.30 The following section outlines a taxonomy of these details – first the visual and subsequently the acoustic elements – which produce the authenticity feeling.

How Is the Authenticity Feeling Created?

Historical films express authenticity via a qualitative and quantitative excess of detail, reconfirmed with perpetual references, both within the films themselves and in extratextual discourse. Period films, according to Jonathan Stubbs, “have represented the past by accumulating visual evidence which evoke a sense of historical period and overwhelm potential laxities in the narrative. . . . material details are foregrounded as a way to establish an authentic connection with real events”.31 Vivian Sobchack argues, moreover, that history “emerges in popular consciousness not so much from any ‚particular accuracy‘ or even ‚specificity‘ of detail and event as it does from a ‚transcendence of accuracy and specificity‘ enabled by a general and ‚excessive‘ parade and accumulation of detail and event”.32

In practice, films thematise authenticity directly. Prologues and the frequently deployed line “based on a true story” are exemplary in this sense: e.g., FARGO (Joel and Ethan Coen, USA 1996) and the spinoff television series FARGO (series, USA 2014–), which use the cliché ironically (both are decidedly not based on a true story), or AMERICAN HUSTLE (David O. Russell, USA 2013), with its entreaty that “Some of this actually happened”. Stubbs gestures to the long tradition of such texts as well as other ways by which authenticity is foregrounded in typographical form. GLORY (Edward Zwick, USA 1989) conveys the fact that the letters from the protagonist Robert Gould Shaw (Matthew Broderick) “are collected in the Houghton Library of Harvard University”.33 The epilogue of many historical films functions in a similar manner. Without fail, a final message in a white, solemn font upon a black background (or photographs or documentary moving images of the real-life historical figures) announces the fate of the hitherto depicted events and the further course of history. This tactic connects the drama to the “real history” and in this way, according to Stubbs, “works to close the gap between the film’s representation of historical events and the historical events themselves”, with the intention of underlining the authenticity of the production one final time.34

Beyond intertitles, a tactical implementation (and publicity-based dissemination) of details seeks to evoke an authenticity feeling. On the level of the story, filmmakers attend to seeming trivialities. For THE WHITE RIBBON (DAS WEIßE BAND – EINE DEUTSCHE KINDERGESCHICHTE, D 2009), Michael Haneke insisted upon sowing fields with antique seeds from the depicted decade.35 Such details are “excessive”; audiences would hardly perceive the story or historical interpretation of the Kennedy assassination differently if the district attorney drinks a beer on a bar called “Napoleon’s” or one named “Tortoich’s”. In fact, they remain more important for later marketing and reception discourses, where filmmakers can use them to highlight the accuracy of their production, as here in the case of Oliver Stone and JFK (1991).36 For spectators, the very act of ‚knowing‘ these details creates a feeling of confirmation, which can be activated before, during or after viewings of the film itself.

Authenticity’s other visual indices reside in the mise-en-scène: costume, production design and locations, props and casting. Costumes, in particular those used to characterise prominent historical figures, must be recreated; other period production necessitate time-consuming visits to vintage shops, costumiers such as Angels Costumes or dedicated stocks.37 Indeed, costumes play such a privileged, visual role in the production and recognition of a historical film that the term costume film is used to designate (and denigrate) a subgenre.38 Filmmakers insist on reconstructing scenes precisely and slavishly, as a way to accrue added authentic value. In ZODIAC, for instance, the filmmakers insisted on shooting the murders on their precise historical locations. When the local authority in the posh San Francisco neighbourhood Presidio Heights rejected a shooting permit application, the filmmakers assiduously recreated the intersection in Downey Studios and had the background simulated with CGI designed by the special effects company Digital Domain.39

Props are hardly trivialities in period film production. In the reception of the many so-called ‚Ostalgie‘ (nostalgia for the East German past) films, the production designer was celebrated as a sort of auteur. Lothar Holler, who coordinated these duties for exemplars such as SUN ALLEY (SONNENALLEE, Leander Haußmann, D 1999), THE ROOM FOUNTAIN (DER ZIMMERSPRINGBRUNNEN, Peter Timm, D 2001), GOOD BYE, LENIN! (2003) and NVA (Leander Haußmann, D 2005), was interviewed for his role as production designer of GOOD BYE, LENIN! nearly as often as the director, Wolfgang Becker, and the stars, Daniel Brühl and Kathrin Saß.40 In these articles Holler referred again and again to the painstaking and arduous efforts to source authentic GDR match sticks and other East German products at flea markets. (It was after all precisely these products that were discarded after the fall of the Berlin Wall.) Because of the importance of this role, Michelle Pierson refers to the historical film as the “production designer’s cinema”.41 If historical films are evaluated largely according to the perception of historical details, production designers make the crucial contribution to their success.

Casting is likewise of central importance to the authenticity feeling. Characters’ faces and bodies must correspond to viewers’ imaginations, in order to manufacture a believable historical world. The marketing discourses surrounding THE WHITE RIBBON are exemplary. Statements in interviews repeatedly referred to the six months that director Michael Haneke and casting agent Markus Schleinzer devoted to evaluating 7000 head shots of children.42 The aim of finding the “right faces” was in essence an effort to mimic shapes and contours that audiences retrospectively know through other media, e.g., the human bodies on display in old August Sander photographs.

Representing historical figures – the prominent people we learn about in history textbooks and popular media – requires surpassing a further hurdle: through his or her embodiment, the actor writes over or rewrites the knowledge of a more or less well-known individual. In judging such efforts, critics distinguish between mimetic ‚imitatio‘, i.e., impersonation, on the one hand, and an interpretation that somehow transposes the present into the past, a performance that – by its very divergence from pure mimicry – portrays the ‚spirit‘ of the character, on the other. Here again, the ebbs and flows of reception discourses are revealing. Mixed reactions greeted Cate Blanchett’s portrayal of Katherine Hepburn in THE AVIATOR (Martin Scorsese, D/USA 2004), above all because of the recreation of Hepburn’s old-fashioned and idiosyncratic accent, gestures and movements.43 Similarly, Moritz Bliebtreu faced round critique and taunts of hammed-up clownery for his turn as Joseph Goebbels in JEW SUSS: RISE AND FALL (JUD SÜSS – FILM OHNE GEWISSEN, Oskar Roehler, D/AUT 2010). According to critic Hanns-Georg Rodek, Bleibtreu limps as Goebbels, hits his actors chummily with his fist on their chest, he waves around his index finger and even yells, when his avuncular attitude bears no fruit. This is copied precisely from historical film documents and yet comes off as semi-skilled, because it fails to divine the difference between the accurate and the credible: someone who plays Goebbel like he (probably) was back then looks just ridiculous today.44

Bleibtreu’s manner of speaking and gesture – the mimetic representation of Goebbels as he appears in old newsreels and audio recordings, not to mention the many documentaries that recycle these primary sources – functioned in 2010 as a caricature. Despite its accuracy, the performance carried no authenticity and it helped little that other historical, if less prominent, figures (e.g. Tobias Moretti’s turn as Ferdinand Marian or Justus von Dohnányi as Veit Harlan) were portrayed with relative restraint and conformity vis-à-vis twenty-first century norms.

How Can Film Sound Produce an Authenticity Feeling?

Acting performance, and the discourse surrounding it, anticipates the essential role of sound in producing a satisfying historical experience. It furthermore problematises any clear distinction between sound and image in the analysis of historical films. Sound has a key role to play and, indeed, inhabits this function almost always in conjunction and dynamic interaction with images. Despite the research that claims that “Historical cinema, then, is led by ‚visual‘ evidence in its representation to the past . . . . material details are foregrounded as a way to establish an authentic connection with real events”, sound is in fact essential to the credible experience of historicity.45

Historians are just beginning to thoroughly analyse the role of sound in the writing of history. In his monograph How Early America Sounded, Richard Cullen Rath attempts to reconstruct the acoustic world of seventeenth-century America. He argues that sound was particularly important to the people of this era and imagines how different the historical record might appear, had scholars not only taken into account written and other visual documents. According to Rath, sound played a much more important role in that era than in the present day; the dominance of the visual is not an inevitable or natural condition, but rather the consequence of an historical process.46

In contrast, Lutz Koepnick and Nora M. Alter argue in their introduction to Sound Matters that sound is the quintessential element of modernity. Unlike Rath they claim that the acoustic sphere first achieved significant prominence and cultural value in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Furthermore, they contend, sound has an ontological connection with the construction of identity.47 These claims are evidenced by the rise of noise and other acoustic forms in public and private spaces. The advent of the Industrial Revolution in Britain, and later in France, the United States, Germany and elsewhere, introduced a new era and a capital-intensive economic system. “Preindustrial sounds could be traced to their origins—an animal, a hand-held tool, a cloudy sky—and hence made meaningful”, according to Koepnick and Alter.48 In the new, loud metropolitan centres, a sensual overload and a new, strict separation between the visual and sonic suddenly prevailed.49 Repeatedly, Koepnick and Alter refer on the one hand to the sound tradition of Richard Wagner, and on the other to Theodor Adorno (and/or Bertolt Brecht).50 In this context the contrast Wagner versus Adorno/Brecht stands in for many other binary oppositions: harmony versus dissonance, unity versus fragment, synthesis versus dialectic, aesthetic versus self-reflexivity, nationalism versus resistance, conservatism versus avant-garde.

As radical as Rath’s and Koepnick/Alter’s interventions may be among historians and cultural studies scholars, respectively, it is also clear that (at least since the 1930s) filmmakers needed to create narrative worlds out of images ‚and‘ sounds in order to excavate the past in historical films. As progressive historians (e.g., Robert Rosenstone) note, period films are historiographical forms despite – and precisely because of – their commercial mandates, broad consumer address and lack of adherence to scholarly representations of the past.51 But how are these historical realities constructed? With which acoustic details and styles is the authenticity feeling evoked? Which culturally contingent filmic conventions have established themselves in the sonic realm in order to efficiently and effectively depict an “authentic” past? These questions must be answered in this section, first with reference to music and then with a thorough discussion of language.

Music

Experts enumerate four elements of film sound: music, dialogue, sound effects and silence.52 Music is perhaps the most conspicuous aspect; it existed in cinemas even before the first talkies.53 Correspondingly, music is also one of the most important ingredients in the production of historical films; their pastness hinges on music’s potential to efficiently locate proceedings in time, establish mood, characterise, interpret events and so on. Film music, according to James Wierzbicki, structures narrative form and identifies “films’ locales and time periods”.54 Soundtracks, as Arthur Knight und Pamela Robertson Wojcik furthermore argue, “recall us to our past, or they conjure up a past we never experienced and, through the familiar language of popular music, make it ours”.55 Just as effective (and stylistically more elegant) as an intertitle with a day, month or year, a song from the portrayed period can date the story and mark jumps in time. The Four Tops or The Supremes transport the audience back into the 1960s; in addition, of course, they establish a specific mood and delineate a certain human representation and his or her emotions, tastes, class and background. Bob Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” and Janis Joplin’s “Mercedes-Benz” locate THE BAADER MEINHOF COMPLEX historically and allude to the broader, more pacifist left-wing movements around 1968, on the one hand, and to the RAF-terrorists’ preference for fast German cars, on the other. FORREST GUMP (Robert Zemeckis, USA 1994), to cite another example, uses no text intertitles to mark its many jumps in historical time. Instead, Jenny’s changing fashion and hairstyles, but above all a hit-parade of pop songs, perform this narrative function. Elvis Presley’s “Hound Dog”, Aretha Franklin’s “Respect”, Creedance Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son”, Lynyrd Skynyrd’s “Sweet Home Alabama” and Bob Seger’s “Against the Wind” convey, in effective manner, the historicity of the scenes from the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. The music is no background décor: “Without the music, and its discrete meaning existing outside the visual text”, as Hilary Lapedis writes about “soundtrack films” such as FORREST GUMP or TRAINSPOTTING (Danny Boyle, UK 1999) “the film would be less effective”.56 Lapedis’s observation must be refined for cases such as FORREST GUMP. In ‚historical films‘ that use such musical tactics, their ‚historical experiences‘ would be less effective without such music.

FORREST GUMP is merely one of many historical films in which pop hits choreograph a dynamic narrative – and also fulfil economic imperatives. Such soundtracks indicate historicity, but they also entertain, progress the plot, outline character traits and interpret history, often all at the same time. The dénouement of THE SOCIAL NETWORK (David Fincher, USA 2010) provides an instance of this multifaceted impact. The Facebook founder (played by Jesse Eisenberg) sits alone trying the befriend an old college sweetheart, the text “Mark Zuckerberg is the youngest billionaire in the world” appears and the ironic Beatles song “Baby You’re a Rich Man” overwhelms the soundtrack. If it is not already clear by this point in the story, the music helps guide the viewer to a certain, rather negative, impression of Zuckerberg and his efforts to forge friendships: in the end he is a lonely, socially inept plutocrat.57 Beyond this rather conventional narrative function, soundtracks have become key factors for the decision of whether or not to see a historical production and, by extension, whether or not it even is funded to be made. Classic pop hits play pivotal roles in historical film trailers and during key montage sequences. At least since AMERICAN GRAFFITI (George Lucas, USA 1973), soundtracks have proved crucial for Hollywood historical films’ economic success and integral to their profit-driven business models.58 On the one hand, many successful musicals take place in the past, for example THE SOUND OF MUSIC (Robert Wise, USA 1965), GREASE (Randal Kleiser, USA 1978), EVITA (Alan Parker, USA 1996) or DREAMGIRLS (Bill Condon, USA 2006). In these films the music is not made up of songs originally hits in the depicted past; rather the melodies and arrangements seek to evoke those eras and styles (e.g., the 1950s in GREASE or Motown in DREAMGIRLS). On the other hand, and perhaps even more importantly, historical films are “pre-sold”, to use Justin Wyatt’s idiom, with a soundtrack that will attract audiences to the production.59

In many so-called nostalgia films, such as DINER (Barry Levinson, USA 1982) or FORREST GUMP, pop music furthermore functions as a double sign of authenticity. It verifies the events as part of a credible representation of the past and does so with a type of music that radiates another kind of authenticity: the “real” musicians of yesteryear, whether Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix or The Doors. Music historians have demonstrated how the pop music and above all rock history of the 1960s have been associated in the popular memory with craftsmanship, true art and political rebellion (and a rejection of the commercial imperatives of the music industry).60 BAADER (D/UK 2002), Christopher Roth’s auteurist project about the Red Army Faction that renders terrorist leader Andreas Baader like a pop star, is an exception that proves the rule. Unlike in reality, Baader does not die in 1977 by his own hand in the Stammheim prison. Rather, police gun him down in a Frankfurt shootout that, in actuality, led to his arrest. Nearly without exception the music video-like sequences are overlaid with pop music that emanates out of the depicted scenes’ future. The songs, among others by the English rock band Stone Roses, serve (as would ordinarily be the case) not to locate the scenes historically. Rather, they produce a “cool” mood, contribute to characterisation (distinguishing the young, trendy terrorists from the Federal Republic’s square, older generation) and invoke an “authentic”, international, progressive, future wave of music: 1990s Britpop.61 Indisputably an arthouse film, BAADER harbours no pretensions to undertake a conventional, Sobchackian, “general and excessive parade and accumulation of detail and event”.62 Nevertheless, its historiographical mode seeks to advance a particular characterisation of Baader and his group – and thus a certain interpretation of the past – via music.

Historical films that chiefly represent musicians must confront additional aesthetic problems that require bespoke solutions. Unlike the many historical productions that deal with politicians, actors, artists or other historically prominent figures, those that portray musicians must compete with additional audience memories and perceptions from other sources. Chief among these are sound memories, i.e., the associations and feelings that arise from (often repeated) listening to the musician’s work. Biographical films such as THE DOORS (Oliver Stone, USA 1991) or GAINSBOURG (VIE HÉROÏQUE, Joann Sfar, F 2010) narrate the lives of musicians and report in great detail on their love affairs and drug addictions behind the scenes. These productions recreate their subject’s first modest and later spectacular stage appearances, and provide narrative opportunities to hear the musician’s work: performance is key to the generic formula and provision of pleasure. This subgenre, called the musical biopic or musician biopic by fans and press alike,63 features various filmic conventions in order to solve fundamental aesthetic-philosophical problems, such as: How can one credibly represent the well-known achievements of these highly talented and unmistakable musicians? Some films largely do without new recordings. Instead, threy create a convincing audio-historical experience by reusing original sound in the film itself. THE HARMONISTS (COMEDIAN HARMONISTS, Joseph Vilsmaier, D/AUT 1997) exemplifies the use of this tactic. The German boy band is embodied by Ben Becker and other actors; the group’s singing, however, derives from the 1930s recordings. The advantages of this method of historical representation are clear. Casting selection can focus on appearance and acting talent and the production must not devote any herculean effort to recreate the accomplishments of the bygone musicians. Furthermore, audiences immediately recognise the music as authentic, which directly activates a sound memory. In such a scenario, however, the actors must mime and sing in lip-sync, a means of sound-image performance and editing that, when not handled with utmost precision, can leave the audience with the strong impression of illusion, fakery and simulation: the dissonance between the authentic sound, on the one hand, and the recreated visual staging of the actor’s foreign body, on the other, only increases and can become painfully plain. Such an aesthetic can therefore effect an involuntary distanciation in the reception, as evidenced in reviews and internet audience forums.

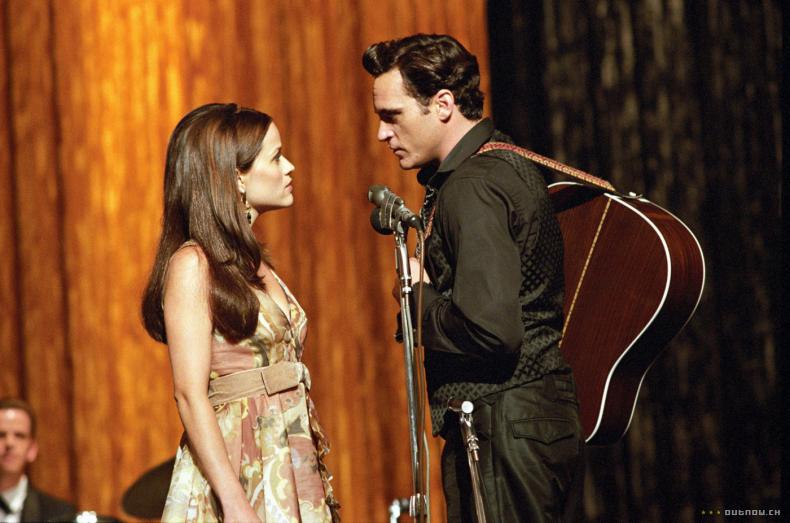

For this reason, a second strategy rejects synchronisation.64 In projects such as RAY (Tayler Hackford, USA 2004) or WALK THE LINE (James Mangold, USA/D 2005), Jaime Foxx and Joaquin Phoenix perform their own interpretations of well-known Ray Charles and Johnny Cash songs, respectively. Such productions also attempt to deliver an authenticity feeling; the aesthetic dilemma is resolved in a different manner, however. In other words, the artistic and musical talent of the recreating ‚actor‘ is decisive; his or her performance is implicitly, but usually explicitly, compared to that of the historical musician. Indeed, marketing discourses typically belabour the extensive vocal training required for the role. Reese Witherspoon, who played June Carter in WALK THE LINE (and later received an Oscar for her efforts), was asked by a reporter how she mastered the “difficult task of singing like June Carter”:

Well, [it was] nearly impossible so I just tried to be the best version of what I could be, because it was impossible to emulate her. And I’m sure on Joaquin [Phoenix]’s part it was pretty difficult to emulate Johnny Cash. But we trained for five and a half months and learned to play instruments, record an album, and worked six or seven hours every day for five months on it. So you can’t say we didn’t try.65

Correspondingly, the reception of musician biopics largely dwells on the success or failure of the acoustic imitation. Remaining on the example of WALK THE LINE, film critic Roger Ebert’s evaluation is revealing:

It is by now well known that Phoenix and Witherspoon perform their own vocals in the movie. It was not well known when the movie previewed – at least not by me. Knowing Cash’s albums more or less by heart, I closed my eyes to focus on the soundtrack and decided that, yes, that was the voice of Johnny Cash I was listening to. The closing credits make it clear it’s Joaquin Phoenix doing the singing, and I was gob-smacked. Phoenix and Mangold can talk all they want about how it was as much a matter of getting in character, of delivering the songs, as it was a matter of voice technique, but whatever it was, it worked.66

In this way, these films make aesthetic claims (the imitation of a known performance) that transcend those of other genres and modes; in turn, the fulfilment of these demands provides audiences with an added value. The evaluation of (and any pleasure derived from) the imitation partly distracts from the fact that the sounds and visuals are recreated in the present of the production, emanating from a time and space detached from the treasured recordings. In addition, these productions offer the opportunity to revive (and re-monetise) old classics. In the vein of a live performance by a Beatles cover band or going to see a Queen or Michael Jackson musical play, musician biopics satisfy a longing for the repetition, with small changes, of a past positive experience. This discussion of pop music – which traditionally foregrounds the singer and his or her putatively unique voice in the sound mix (let alone the marketing) – anticipates the importance of language, a subject to which I now turn.

Dialogue and Language

Even if critics and audiences most often consider music to be film’s most artistic sonic aspect,67 filmmakers themselves maintain a different perspective. “Ask any sound professional in the film industry today what is the most important element in the soundtrack”, Gianluca Sergi attests, and “you will invariably receive the same answer: dialogue”.68 The audibility of every last footstep or every last tuba note on the score is ultimately secondary: in contrast, however, every line of dialogue must be clearly heard. Compared to music, dialogue remains problematic terrain in period productions, a formal element that foretells a whole host of aesthetic and cultural quandaries. The ability to even reconstruct dialogue presents serious issues for the makers of historical films. For example, in ZODIAC, which commits to an extreme form of authentic recreation, it is simply impossible – unlike costume, hairstyles, make-up or props such as cars – to exactly convey the precise conversations between victims directly before their deaths.

That is not to say that many films do not attempt to recreate dialogue as faithfully as possible to the historical record. This impetus abounds among productions set in recent history, especially those that revolve around politicians, celebrities and others subject to frequent media scrutiny. Such projects can use word-for-word quotations from speeches or interviews in their screenplays. Indeed, some historical films, in the tradition of documentary theatre,69 compose dialogue using largely or exclusively confirmed sources such as public reports and newspapers, as well as radio and television appearances. Reinhard Hauff’s STAMMHEIM (D 1986) is an archetype of this strategy. It thematises the 1975-1977 trial of Andreas Baader, Gudrun Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof und Jan-Carl Raspe using text that derives from court protocols. In this way the various (and hotly contested) historical interpretations of the RAF and the death of Baader et al. are contrasted with the sober, “objective” perspective of the dialogue.

BAADER represents a further example of using real quotations. The conversation between Helmut Ensslin (Peter Rühring) and his daughter Gudrun (Laura Tonke) stems from an interview he gave after the 1968 Frankfurt department store fire. The texts spoken by the characters Ulrike Meinhof (Birge Schade) and Horst Herold (Vadim Glowna) are adapted in part from newspaper articles written by the real Meinhof and Herold. Both sources are reprinted in Stefan Aust’s standard history on the subject, Der Baader-Meinhof-Komplex.70 To be sure, this type of historical sound authenticity risks alienating audiences with anachronisms. The effect can be similar to the case of the Bleibtreu’s depiction of Goebbels in JEW SUSS (D 1940): the real quotations (the historical figures themselves often recycled Marxist teachings word for word) from the wild 1960s and 1970s seemed stiff and archaic even by the time of BAADER’s 2002 release. Director Christopher Roth faced caustic critique in arts pages, and an almost invisible theatrical reception (30,000 tickets sold in its domestic run), on account of such dramaturgical methods.71

Unlike other aspects of film sound such as the score and pop music, the role of dialect in particular and of language in general remains strongly bound by cultural differences. Dialect is ‚a priori‘ unique or peculiar; it contains untranslatable meanings. To be sure, Sardinian, Scottish and Swabian maintain some parallels (especially in their relations to the dominant dialects of their respective language groups); nevertheless, they can hardly be compared directly. Indeed, language is the quintessential substratum and codeterminant of culture. Furthermore, there are traditions of individual national and regional film industries – for example vis-à-vis subtitling and dubbing – that arise for complex reasons (including the size of the language community, the mutual comprehensibility of different dialects, the market for foreign-language films, state funding and other interventions). This fact suggests that films create a credible historical experience dialect conventions that may vary widely. A few examples can illustrate this point.

THE PASSION OF THE CHRIST (USA 2004) was shot in Latin, Aramaic and Hebrew. Director Mel Gibson took it as a central task to recreate the authentic languages and wordings that the historical figures themselves used.72 In this way the film distinguishes itself from the many epic Hollywood historical films set in the Near East or ancient Rome whereby the characters all speak English. Nevertheless, in order to resolve the same aesthetic problem (i.e., How can actors who portray historical figures sound credible?) Ridley Scott came to a wholly different conclusion in GLADIATOR. All actors speak English; however, each actor was allowed to deliver the dialogue in his or her native (Australian, Irish, English and so on) accent. In this way, according to Scott, the characters would seem “less ‘actorly’ and thus more sincere”.73 The subtext here is the aforementioned tradition of Roman epics like QUO VADIS (Mervyn LeRoy & Anthony Mann, USA 1951) or SPARTACUS, in which the Roman elites speak posh British English and the slaves have common American accents. English-language historical films (like fantasy films) have naturalised codes that express social power relations via (historically speaking completely absurd) dialects.74

In contrast, other filmmakers use a highly consistent and historically documented dialect as an opportunity to efficiently convey an authenticity feeling. HEIMAT (DE 1984) director Edgar Reitz insisted that the actors’ speech should correspond as closely as possible to the local Hunsrück idiom. Yet again in this case, questions of acoustic representation commingle with the politics of identity. Reitz’ aesthetic choice must be understood as a formal but ultimately historiographical programme. Dialect in HEIMAT must be considered on the one hand as part of the larger sound design: the dialogue and even the music in HEIMAT were produced live in front of the camera, i.e., not added in postproduction. “The HEIMAT series”, as Michael Kaiser writes, “applied the principle of producing as much authenticity as possible during the shoot, in order to approximate in this way reality as closely as possible under the artificial conditions of a film production”.75 As a reaction to the perceived cultural appropriation of the German past through US-American film forms, narrative storytelling and historical interpretation, the HEIMAT projects’ precise use of local dialect (and sound in general) constitutes, on the other hand, a political message. According to producer Joachim von Mengershausen, Reitz developed the concept for an epic family history, out of which HEIMAT emerged. Back then it was still, originally called ‚Made in Germany‘ – which exactly reflects what we were feeling back then – namely, no longer ‘Made in USA’ but ‘Made in Germany’ – it was supposed to be a programmatic title, but then at the very end of production and also because of the influence of Constantin boss Eichinger, who had worked hard to secure the premiere of the film at the Munich Film Festival – because of his influence the film or the series was called in the end HEIMAT.76

In other words, an acoustic-aesthetic-political authenticity in the film’s representation (and conscious rewriting) of history was developed as a means to counteract a perceived loss of national identity and longstanding cultural appropriation. Reitz himself fuelled this interpretation. According to him:

Neither on German television nor in any kind of feature film, whether from America or Italy or anywhere else, does synchronisation look [as if it were recorded] live! Never in my life have I seen a film in which a synchronised recording looks as if the people are really playing [music live] – never! . . . Film crews almost never understand what I mean.77

As we shall see plainly in the subsequent discussion of REQUIEM (Hans-Christian Schmid, D 2006), the role of dialect in HEIMAT represents an exception among German historical films. In other cultural contexts, however, accent and dialect are essential components of dramatising history on screen. In representations of British history, for example, filmmakers take pains to ensure clearly recognisable and differentiated accents. This rule obtains across the spectrum of production, including blockbusters recreating epic events from the distant past (BRAVEHEART), small-scale auteurist reckonings with recent times (e.g., Lynne Ramsey’s 1999 art film RATCATCHER (UK/F 1999), set in 1970s Glasgow) or television efforts of all shapes and sizes. These conventions not only reflect Britain’s regional identities, postcolonial legacies, funding-body imperatives or the omnipresent discourses of today’s multicultural society and anxieties surrounding immigration. In British English class is expressed largely via spoken language and accent; hardly restricted to films that dwell explicitly on these themes, such as THE KING’S SPEECH (Tom Hooper, UK/USA/AUS 2010), sound quality, intonation and the performed heritage of language offer an essential contribution to characterisation, story and thus historical interpretation.

It is important to note that such “details” can have substantial effects on the reception of historical films. Ultimately, they exert a significant influence on the credibility of the historical experience and the creation of an authenticity feeling. The reception of ROBIN HOOD (Ridley Scott, USA/UK 2010) was chiefly a discussion of dialect: commentators accused Russell Crowe – despite “hours of intensive vocal training” – of failing to reproduce the Nottingham dialect. This linguistic error was interpreted as a miscarriage of professional performance, but moreover a fatal flaw in the aesthetic experience of the film.78 “Russell Crowe accused of making Robin Hood sound Irish”, wrote The Daily Telegraph, one of many British and international newspapers that reported the incident.79 Indeed, the press have traditionally made dialect the main topic in their reportage of Robin Hood adaptations: “When Errol Flynn played Robin Hood in 1938 he spoke with an upper-class English accent while Kevin Costner was criticised for his strong American accent in the 1991 film ROBIN HOOD: PRINCE OF THIEVES”.80

Nevertheless, the equal and opposite general principle, that the accurate rendering of dialect – in the minds of critics and audiences – will guarantee a positive reception, does not obtain. There are counterexamples by which films attempt to convey a realistic historical experience precisely by ‚avoiding‘ dialect. REQUIEM, a portrait of a young, schizophrenic woman set in the Swabian Alp and Tübingen areas of 1970s southwestern Germany, is such a case: the local dialect, Swabian, is circumvented completely. The main characters, who come from simple, working-class local origins and are portrayed by classically trained, award-wining actors (e.g., Sandra Hüller and Burghart Klaußner), might as well come from Hannover or Paderborn, so closely do they intone standard German, ‚Hochdeutsch‘. I was not able to find any interview with the director Hans-Christian Schmid or the other filmmakers in which they justify the aesthetic decision. Nevertheless, the lack of dialect was noticed in reviews. On the website filmspiegel.de, for example, the use of standard German was deciphered in the following manner:

REQUIEM is an inventory, a purely empathetic rendering of a thought-provoking death, which in reality of course had much more absurd features than the representation in the film. REQUIEM is the attempt first to depict and then to understand, and is thus the sharpest contradiction of popular cinema. Evidence thereof is the avoidance of dialect, which would have all too quickly stigmatised the events as curiosity, or the almost complete relinquishment of depicting the world of medicine, which would have brought familiar, scientific explanatory patterns into play. The spectator is supposed to participate in the fate of Michaela Klinger without prejudice and only thereafter concern him- or herself with the question why. First the emotional, then the rational dimension.81

The review portal critic.de claimed that:

The rational stance of the director is unmistakable in every shot: no image bears evidence of the supernatural, no shock effect pulls the spectator into the psyche of the girl. For there are no abysses to find there, but rather a human fate that is universally valid, and precisely without a fixed geography and time. Deep Purple’s ‘Anthem’, which gives the film part of its unique atmosphere, sets the mood, rather than indicating the historical period. And the Swabian surroundings are merely an example for provinciality as a breeding ground for false dreams and fundamentalist thoughts. None of the protagonists speaks in dialect.82

The first reviewer deems the avoidance of dialect (in a German historical film) above all as a sign of an art film (rather than “popular cinema”). The neutral ‚Hochdeutsch‘ is interpreted as evidence of a “rational” perspective. Moreover, the review suggests that the use of Swabian (perhaps unlike dialects from Berlin, Hamburg or other areas of the German-speaking world) would have harmed the drama. That particular idiom, often considered by non-speakers to be cute, ugly or silly, would have distracted from the serious theme of mental illness. In contrast, the use of standard German allows the spectator an engagement with the depicted events “without prejudice”. The second critic interprets the use of standard German in the rural areas of Baden-Württemberg as an attempt to generalise and universalise the story: the film avoids simply recreating the details of an exceptional event and instead delivers an atmospheric sketch that could happen anywhere, an important objective in the aim to evoke empathy among diverse audiences. This sound strategy is important, according to the reviewer, in narrating an allegorical – rather than merely “accurate” – story. The acoustic parallel to the role of music is significant: the Deep Purple song serves more to furnish a mood than to date the film in a specific time. The (sound) representation is thus evaluated positively.

Furthermore, both critics imply that the use of dialect in (German) historical films does not contribute to the feeling of authenticity. Perhaps based on the German tradition of populist and trivial ‚Heimatfilme‘ or television movies and series such as DIE KIRCHE BLEIBT IM DORF (Ulrike Grote, D 2012; series from 2013) or SOKO STUTTGART (D, from 2009), they consider dialect to detract from the aesthetic value of historical films. One must only think of Italian neorealism, e.g., LA TERRA TREMA (Luchino Visconti, IT 1948), or refer to the aforementioned British tradition, to demonstrate how such film sound conventions are culturally specific.

To be sure, there are other essential aspects of a taxonomy of historical films’ linguistic-acoustic representation beyond regional differences. Swearing and other vulgar expressions – a culturally important subgroup of language’s lexical level – project respect and/or contempt as well as class differences. Such linguistic elements are especially important in the reception of historical films. One case can be found in Alison Landsberg’s analysis of DEADWOOD (USA 2004—2006), the much-praised US-American television series that takes place in a gold rush town in 1876. Landsberg’s observations tell us much not only about the historio-political implications of swear words, but also resound with the overall project of Audio History. Landsberg claims that “sound and language can elicit particular kinds of spectatorial responses”.83 The use of sound, which can produce “specific kinds of cognition and knowledge”84 in the spectators of historical films and series, functions in DEADWOOD by “mov[ing] spectators between spectatorial identification and alienation”.85 The series consistently avoids non-diegetic music. Furthermore, it attempts repeatedly to reconstruct detailed, difficult-to-produce and historically documented sounds. Sound memories that no longer have cultural currency today – for example, the screams of a character who undergoes a medical operation without anaesthesia, or the montage of the many town residents who experience the ruckus through the contemporary buildings’ thin walls – are foregrounded.86 In this way the historicity of the proceedings (the lack of narcotics and medical knowledge, but also the proximity of the community – all experience other community members’ deaths, births, illnesses, sexual intercourse and so on acoustically) are marked and emphasised through the interaction of film sound, empathy and the authenticity feeling.

In DEADWOOD, language has important consequences for the transmission of the authenticity feeling, on the one hand, and the type of spectatorial identification, on the other. Landsberg cites the New York Times critic Alessandra Stanley, who is thoroughly surprised by the series’ dialogue: both the good and evil characters use a “crude language more commonly associated with THE SOPRANOS”.87 In some of the series’ conversations, “cocksucker”, “pussy”, and above all “fuck” are heard in almost every line of dialogue; such encounters hardly push forward the plot and contribute rather to characterisation (of individuals and of the overall milieu). Other reviewers gesture towards the generally baroque quality of speech: “big looping passages of quasi-Elizabethan prose that immediately set the show apart from the usual western repertory of variations on the word ‘pardner’”.88 Through the generally old-fashioned and partially unintelligible dialogue (for example: “The Creator in his infinite wisdom, Miz Garret, salted his works so that where gold was, there also you’d find rumor, though he decreed just as firm that the opposite wouldn’t always hold”), according to Landsberg, “conjur[es] a world to which we have only limited access”.89 In the film scholar’s opinion, this stylised speech requires an active form of spectatorship: “the language calls attention to itself and [the viewers] must work to make sense of what is being said”.90 Indeed, it helps express the multilayered network of social relationships in the series; with the many allusions to the Bible and Shakespeare, DEADWOOD transmits a past with fixed, common cultural goods that are also shared by the many illiterates in the community – an idea that was integral to the authenticity efforts of producer David Milch.91 In this sense the cursing and other vulgarities remain part and parcel of a historio-political strategy: to build a bridge between the past and present. “Profanity”, according to Milch, “was the ‚lingua franca‘ of the time and place, which is to say that anyone, no matter what his or her background, could connect with almost anyone else on the frontier through the use of profanity”.92 Clearly, Milch seeks to evoke an authenticity feeling by means of well-researched, historically documented language use. Swearing has further effects, however. Contemporary audiences are reminded of THE SOPRANOS (USA 1999-2007), that is, of the present itself as time period but even more so the present of the medium – high-quality cable television – and its regulation. Of a time in which (unlike Hays-Code-era Hollywood) more piquant forms of expression have become quotidian in various audiovisual media. In this sense, one can consider Landsberg’s analysis of profane language in DEADWOOD symptomatically. That Milch’s authentic, profane dialogue could surprise critics demonstrates their expectations of staid or refined language in historical films and series.

Landsberg’s observations beg important questions: Why do historical film audiences expect such acoustic rules and norms? Why is (sound-)authenticity sometimes perceived as inauthentic? In order to answer these questions and to conclude this section of the article, I present here important results from Claire Monk’s empirical study regarding historical film audiences’ behaviours, preferences and understandings regarding language, swearing, authenticity, class and historiography. These can help us test and confirm the aforementioned observations regarding the role of sound and above all language. For: Landsberg’s analysis of DEADWOOD is an important example of how film scholars might recognise and analyse how sound functions in producing an authenticity feeling. (The final portion of this article offers further case studies that could also be productive in this sense.) And yet Landsberg’s efforts are neither comprehensive nor conclusive. In essence, she argues – with reference to various formal and stylistic elements in DEADWOOD – that sound (and above all language) is decisive in the creation of historical understanding and an authenticity feeling. To my mind, this argument is successful; after all, I propose a similar thesis. Landsberg’s claims about audience reactions are more asserted than demonstrated, however. Indeed, except for a few New York Times critics, public opinion (besides her own of course) is completely ignored.

Claire Monk’s empirical study regarding historical film audiences – one of the very few of its kind – is revealing in this context. Unlike science fiction, fantasy or horror,93 the audiences and fans of historical films remain neglected. Monk’s project, conducted between 1997 and 1998, examined two different subgroupings of the “heritage film” audience: readers of the London listings magazine Time Out and members of the British cultural preservation society, the National Trust.

The study has important implications for our discussion regarding authenticity and the function of sound in the production of the authenticity feeling. Both groups found authenticity to be of central importance to their experience, even if in different measures. Roughly 60 percent of the overall younger Time Out group, almost exclusively Londoners and cinephiles, deemed the “accurate reproduction of details in period settings” and “looking at period costumes” to be of central importance, even if only 17 percent of these viewers estimated this aspect as “very important”. In contrast, the overwhelming majority (95 percent) of the National Trust cohort found such elements to be important and 81 percent considered them to be “very important”.94 Furthermore, there were recognizable differences in the understandings of the concept of authenticity. The Time Out group emphasized an authentic ambience, i.e., an authenticity feeling that derived from stylistic details, even if the individual costumes, locations and so on were never their main focus. In contrast, the National Trust members fixated obsessively on details, often at the expense of the story or characters themselves.95 The latter group evaluated the “accurate reproduction” of historical details to be even more important than “visual enjoyment”. Some of the interviewees “did not respond to period films ‚as films‘, narratives or dramas, but more as a pretext for the scrutiny of detail”.96 This perspective, according to Monk, was the essential feature of the National Trust cohort and betrayed its understanding of the function of history. “Quality”, “authenticity” and “educationality” (i.e., the exercise of cultural competence) were frequently used terms by which the interviewees justified their interest in historical films.97 According to Monk, “spotting perceived inauthenticities and anachronisms (of period detail more than historical fact) was a source of active enjoyment. Indeed, the criteria of authenticity applied to period films by some respondents were unworkably stringent; and for some […] this exercising of cultural or historical knowledge was an important – if at times sadistic and fault-finding – pleasure”.98

Monk is surprised – perhaps on account of the fixation on visual details in the scholarly literature – with the evaluation of the role of sound in her questionnaire. “It was notable that so many respondents were as preoccupied with the (perceived) historical ‘authenticity’ (or otherwise) of dialogue, and the speech/diction and deportment of actors, as they were with details of visual styling”.99 In the survey the participants mentioned again and again – of their own volition and without targeted questioning on Monk’s part – acoustic elements as decisive in their preference for the heritage film and in their evaluation of individual titles. Historical films offer “true langue [sic], not pseudo dialects”, claimed one interviewee.100 In this context “true langu[ag]e” means a grammatically correct, finely expressed manner of speaking with neither modern pronunciation nor slang: via historical films’ soundscape, many of the study participants hoped to escape the unpleasant elements of modern life.

This way of seeing – and above all, ‚hearing‘ – historical films implies a relative evaluation of other exemplars: modern, vulgar comedies, but also art films and social realism with strong regional accents, for example Ken Loach. Class differences, norms and good manners were often the crucial issue in their appreciation of sound and language in the historical film. According to the opinion of one participant, “Dialogue indicates education. Generally,” she appreciates “an absence of vulgarity”.101 This opinion was widespread. One interviewee mentioned the lack of curse words as the great advantage of the historical film. The spectators’ negotiation of language also betrays, moreover, cultural, national and industrial preferences and prejudices. Many of the participants associated culturally or historically non-authentic language with Hollywood historical films such as ROBIN HOOD: PRINCE OF THIEVES (Kevin Reynolds, USA 1991), an exemplar mentioned several times.

Interestingly, both the older, more conservative National Trust members and the younger ‚Time Out‘ cinephiles partook of this discourse. For the former group, however, this view of language functioned as part of a pro-British patriotism and a means to express the putative superiority of the British film industry over Hollywood and the United States. The ‚Time Out‘ group perspective, in contrast, served a preference for quality, more artistically worthwhile films, rather than mainstream culture.102 The viewer comments reveal a vague, resistant understanding of the role of Britain and the domestic film industry in the world: e.g., “Actors and actresses’ accents are sometimes wrong for the period or setting, often because ‘American’ stars are used to sell the film in the USA market”.103 (This sentiment has been observed also in earlier studies.)104 In this way, locution plays an important role in evaluation: “I hate any slip in the language which makes [an historical film] unbelievable”.105 Speech connects also here quite directly to authenticity – and with it, the value of films and history.

Monk’s results are resonant for the purposes of the current essay in at least three ways. First, sound – and above all language – is a decisive, empirically documented factor (and, in some instances, one of the ‚central‘ reasons) for audiences’ consumption of historical films. For some viewers at least, heritage films offer a safe space, far removed from contemporary fears about, and distaste for, indulgent representations of sex, violence and so on. Second, the policing of the (perceived) (in)authenticity of language in historical films is for many viewers a desirable task and even constitutes one of the main activities in the reception. The authenticity feeling is therefore not a passive condition; rather, its arises from an active negotiation with the film and its stylistic characteristics. The audience often intensively attempts to challenge the filmmakers by scrutinising details, mistakes and other discrepancies. The caricature of the daydreamer spectator, who considers the depicted past like a beautiful fantasy, cannot be substantiated in empirical observation. For this reason, authenticity criticism (for example of the type put forward by the heritage film critics), formulated after all without reference to any real, existing audiences, must be urgently revised. Third, regarding language, viewers react to certain historical film conventions that have developed over time. To be sure, people living in the nineteenth century, and much earlier, swore; but over time it has become the norm not to use such rough language and vulgarities – or to use them less – vis-à-vis other genres, e.g., action movies, gangster films or comedies. The authenticity feeling thus refers just as much to film history (an individual, subjective film history – the films that one has seen in his or her life) as to history writ large, the one learned in schoolbooks. (There is furthermore the tradition in such films to concentrate on the “mannered” classes and historical episodes, which only compounds such perceptions.) It is also for this reason that exceptions like DEADWOOD prove the rule. The surprised reactions of critics – that DEADWOOD sounds like THE SOPRANOS – demonstrate symptomatically how deep-rooted such norms may be.

Language and Dialect in Context: Three Case Studies of an Audio History of Film

This article has demonstrated the extent to which filmmakers deploy sonic stylistic elements – and above all language and dialect – in order to create a credible historical representation and authenticity feeling, and how these efforts are explained and evaluated in marketing and reception discourses, respectively. For example: both GLADIATOR and REQUIEM avoid historically correct language and dialect, respectively. The very same aesthetic decision is used as evidence, in the reception of each film, to categorise the former as Hollywood and the latter as an art film. These codes are – as demonstrated clearly in the comparison between German and British historical films – culturally specific and not universal. Indeed, they are not even necessarily consistent across a filmmaker’s body of work: Ridley Scott experimented with two very different dialect conventions in two of his films, GLADIATOR and ROBIN HOOD. Such conventions are unstable and not bound to hard and fast rules; they vary according to culture, depicted epoch, filmmakers, intended audience and, indeed, even within these categories. A generic inventory, in which for example the appearance of dialect gestures definitively to a certain meaning (art cinema, “authentic” mode of historiography) is therefore useless. Aesthetic elements and decisions lead – in various constellations, but also because of material influence in the marketing, distribution, exhibition and so on – to (intended or unintended) interactions and consequences, which must be considered in close analyses and case studies.

It is furthermore important to emphasise that individual stylistic elements always function in larger contexts. In addition to and in conjunction with language and dialect, there exist other essential aspects of a taxonomy of historical films’ acoustic representation. For instance, in FORREST GUMP, Tom Hanks’ conspicuous, Southern US-American accented voice-over must be considered in concert with the prominent pop music and the relative lack of other sound effects: Randy Thom’s focussed sound design differentiates the life phases of Gump and the historical events of the United States across the second half of the twentieth century.106 Any attempt to consider these elements individually and exclusively poses the risk of misappropriation and misunderstanding: such acoustic tactics may be important parts of their films’ historical interpretations, but taken singularly and out of context they do not correspond to typical audiences’ experiences. Language, dialect and the authenticity feeling, among the most essential elements of an historical film for its consumer, function in larger constellations.

So what could an Audio History of Film look like, in practice and applied to individual, exemplary films? With three examples that I submit here less as completed analyses but rather as approaches to and beginnings of possible audio(visual) investigations, I would like to conclude my article and simultaneously pave the way for further efforts of this kind.

A. Language, Music, Historical Interpretation: Two Sound Montages in ZODIAC

The sound montages in ZODIAC demonstrate how multi-layering can create narrative transitions and simultaneously advance particular interpretations of the past. This film, which contains many jumps in historical time, hints in various ways when a good deal of time passes between scenes. These markers include the display of text with dates (e.g., “2 weeks later – October 11, 1969”); new fashions in costumes, different car models, evolving technologies (e.g., typewriters) and other props. Montage sequences also feature for this purpose: for example, the construction of the iconic Transamerica Pyramid building (finished in 1972) is depicted in fast-motion, accompanied by Marvin Gaye’s 1971 song “Inner City Blues (Make Me Wanna Holler)”. Later in the film, a sound montage against a black background functions as a formal alternative. A whole host of voices, musical motifs and other sounds can be heard: Richard Nixon (from his speech about “peace with honour in Vietnam”), the commentary of the iconic television presenter Walter Cronkite regarding the arrest of Charles Manson, as well as Queen Elizabeth’s speech on the occasion of the US bicentennial celebrations. Simultaneously, there are excerpts from news reports, among others regarding the Chowchilla kidnapping, the death of Mao, the resignation and pardoning of Nixon, the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa and the arrest of the “Son of Sam” serial killer. Likewise spliced into the sound mix are pop songs – for example, The Temptations’ “Papa Was a Rolling Stone”; Roberta Flack’s “Killing Me Softly”; Bachman Turner Overdrive’s “You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet” and The Ohio Player’s “Love Rollercoaster”. Only at the very end of the 53-second sequence is there a text subtitle: “4 years later”.