Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis')

Table of Contents

Soviet Film Footage and Professional Practices (1941–1945)

Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis')

A Travelling Archive

Zinovii Tolkachov’s Graphics from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek Death Camps

People with Disabilities as Nazi Victims on Screen and Paper

Forgotten: Film Documents from the Liberated Camps for Soviet POWs

Depicting Atrocities

Reflections on the Geography of the Holocaust Based on Soviet Film Footage

Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv

Filming Auschwitz in 1945: Osventsim

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Pozner, Valérie. “Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis').” Research in Film and History 6 (2025): 1–27. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/23562.

The vast majority of Soviet footage selected and digitised for the Visual History of the Holocaust (VHH) project comes from the Russian State Archive of Film and Photographic Documents (RGAKFD), located in Krasnogorsk near Moscow. In a country with a highly centralised system of government, the concentration of records in a place close to the seat of power is hardly surprising. For a long time, it was impossible to disseminate some of the visual evidence of Holocaust-related crimes that was recorded by Soviet camera operators in the weeks, months and years after they took place. But that all changed during the period when the archives were open (1991–2022), as this material could now be used in both post-Soviet and Western documentary productions.

The Russian archives preserve two types of documents relating to the World War II period: firstly, edited films, generally with sound, that were widely distributed (documentaries, newsreels, short films known as “special editions” that dealt with specific events: trials, liberations, discoveries of atrocity sites, etc.); secondly, an enormous mass of archival material, collectively referred to as kinoletopis’, literally “cinematographic chronicle.” The sometimes surprising kinoletopis’ sequences show little-known aspects of the filmed subjects’ experiences and were not circulated at the time of their creation. An emblematic case is a shot of the prayer shawls of the Jewish victims of Auschwitz, filmed by Soviet camera operators at the front and long kept in the archives, only to then later end up being overused.

The vast majority of the post-1991 films that used the RGAKFD material made no distinction between the two types of sources; both are incorporated into the same edits and no indication is given of their different status. The aim of this article is to highlight the differences between footage from Soviet and Anglo-American archives, and to explore the difficulties of attribution and interpretation inherent to this corpus.

In both the card files and the RGAKFD online catalogue, it is difficult to distinguish between the two categories (edited/unedited), since both types of film have titles and inventory numbers, and are summarised in terms of their content. The attribute “sound” or “silent” can often be used as a proxy, since sound equipment was rare at the time and so sound was only added at the post-synchronisation phase when preparing a film for theatrical release; a “sound” film is therefore more likely to be edited footage. However, only viewing a film can confirm this.

One of the first works to clearly make this distinction with regard to Holocaust-related footage was a study by British researcher Jeremy Hicks, who analysed how before footage from Barvenkovo was released, Soviet editors had cropped it to remove the Star of David badges from the victims discovered there.1 A few years later, while preparing the exhibition and catalogue Filmer la guerre: les Soviétiques face à la Shoah (Paris, 2015) the CINESOV team2 likewise highlighted the differences between the two kinds of footage. Firstly, we analysed footage that was filmed for but not included in the special edition of the Soviet news bulletin on Auschwitz OSVENCIM edited by Elizaveta Svilova (Central News Studio, 1945). Secondly, we hypothesised possible reasons for why the footage may have been excluded, drawing attention to how the editing affected the meaning: for example, either Russifying or internationalising the victims. Most recently, Victor Barbat authored a study on the USSR’s efforts to preserve its cinematographic heritage that directly addressed the history and composition of this unique film collection, with a particular focus on the role of filmmaker and archivist Grigori Boltianski (1885–1953).3

However, the conditions under which the kinoletopis’ material was created, the various institutions it was successively managed by and the kinds of intervention carried out on it (technical, censorial or other) remain to be clarified. These factors have left their mark on all visual archives of Soviet origin and must be taken into account when analysing the material that, thanks to the VHH-MMSI platform, is now accessible to a large community of researchers. In the following sections, I will therefore look at the history of this collection, the consequences of the various choices made regarding it and finally the uses to which it has been put.

The Genealogy of an Archival Project

A law passed in 1996, long after the creation of this collection, defines kinoletopis’ as follows: “Regular filming of documentary subjects reflecting the characteristic (essentially ephemeral) specificities of a period, place or circumstance, and carried out in anticipation of the production of a film.”4 This definition, which curiously echoes the preoccupations of certain Soviet filmmakers of the 1920s (the need to fix an ephemeral current event on film), makes no reference to the possibility, desirability or necessity of archiving the material, even though the term is most often applied to film sequences stored in archives.

The truth is, when we talk about kinoletopis’, a problem of definition and scope immediately arises. What exactly are we talking about: shots of historical interest? Unedited film rushes? Or archival compilations – and if so, compilations of what: outtakes from edited films, discarded sequences, extracts from edited films that have been reorganised (For what purposes? According to what principles?)? To answer these questions, we need to go back to the origins of this archival enterprise.

This same relative vagueness is apparent from the first decree instituting the archiving principle on February 4, 1926, which obliged all institutions and companies to deposit all “negatives of shots and films reflecting social and political events and presenting a historical-revolutionary interest in the central archives of the RSFSR (Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic), no later than five years after their production.”5 In the instruction detailing this 1926 decree and the procedures for handing over the materials, it is stated that if the negatives have not been kept, the positives should be deposited instead, and that when they are examined by a commission of experts the producers and owners of images will have to provide the necessary explanations and present “all auxiliary material: inventories, editing sheets, technical documents, catalogues and corresponding positives.”6 The distinction between “films” (edited) and “shots” seems to indicate that unedited elements, outtakes and so on also had to be deposited. In short, this decree covered all material produced during filming. It should be noted that this measure only applied to Russia, not to other Soviet republics.

It is impossible to say to what extent this resolution was applied in practice, or whether the massive loss of films from the 1920s was due to negligence on the part of studios that were unaware of the decree, to the lack of conservation infrastructure or to the need to reuse film (for re-emulsion). Similarly, the documents that I consulted were silent about the expert commissions that were supposed to examine the items when they were deposited.

In any case, the decree’s attention to historical documentation echoes the work and recommendations of certain filmmakers and theorists, including Esfir Shub, creator of a trilogy of montage films devoted to Russian history (THE FALL OF THE ROMANOV DYNASTY / PADENIE DINASTII ROMANOVYH (1927), THE GREAT ROAD / VELIKIJ PUT’ (1927), LEV TOLSTOY AND THE RUSSIA OF NICOLAI II / ROSSIJA NIKOLAJA II I LEV TOLSTOJ (1928)), who was the most eloquent advocate for this preservation programme. She had been involved in rereleasing the films of formerly private distribution and production companies after their nationalisation, and her subsequent texts and speeches attest to a concern with the preservation of filmed documents. Shub advised keeping the negatives intact by duplicating them, whereas the usual practice was to remove fragments directly from the negatives. At the same time, she urged studios to commission films so as to build up a film archive for the future. This double movement upstream and downstream was evident again in 1943.7

The central archives department set up in 1926 was housed in the Lefortovo Palace. Year after year, more photographic and cinematographic documents were added to its collection, soon to be followed by phonographic documents. This material was classified thematically. After Russia’s repressive turn, a “secret” department was created in 1933/1934, headed by an appointee of the NKVD (People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs). On April 16, 1938, the entire archive came under the control of the NKVD, and its director was promoted to the rank of captain in the security forces. The archive’s mission was to receive all documents (films, photos, sound recordings) of “scientific, educational, documentary and current affairs significance” that were “political, historical-revolutionary and sociocultural in nature.” Filmed newspapers and newsreels had to be deposited within two years of their production in the form of negatives, or positives if no negatives existed.8

In practice, completed films were collected this way. But the studios still hold unedited rushes, versions of films or shots that were never released or were deleted from the final edits, shortened sequences and films that were overlooked and not deposited, even though it was theoretically compulsory to do so. This material has not been classified or organised.

It was not until the summer of 1936 that a project known as kinoletopis’9 emerged. Its initiator was Grigori Boltianski, a close associate of Shub. Boltianski had started out in newsreels and organised the filming (at the time under the aegis of the Skobelev Committee) of the events of February 1917, before heading the newsreel department of the Petrograd Film Committee (1918–1919) and other organisations and studios (VFKO, Sevzapkino, Goskino).10 He was also responsible for organising filming of Lenin and later his funeral. Boltianski was a historian of photography, a critic, collector and curator and the first to propose the idea of a film museum/cinematheque in the 1920s.11 He wrote the first Soviet book on film newsreels.12 In the 1930s, as a teacher at Moscow Film School (VGIK) and historical advisor on films about the revolution and civil war, he established himself as the leading specialist in newsreels (film and photography) and continued to push for the creation of archives. However, it was a series of alarming observations dating from the end of 1935 that led to the adoption of injunctive measures. A decree issued by the Central Committee on December 2, 1935 makes clear that the concerns mainly centred on the poor condition of the negatives (especially those for the film CHAPAEV, released barely a year earlier, which had already been sent abroad for restoration): the deplorable state of the development laboratories and printing plants, the excessive number of copies made from the original negatives, the lack of interpositives and duplicated negatives and the poor conservation conditions. The Central Committee instructed the film department to rapidly remedy matters by improving laboratory operations, carrying out a precise evaluation of conserved negatives, paying particular attention to newsreels and documentaries “of particular historical importance” and creating a film archive”13 However, despite the commitments made by the leaders of the Cinema Committee, on June 10 of the following year the Party’s control commission noted that little or nothing had been done. The situation was particularly worrying for the Central News Studio.14

A month earlier, on May 3, 1936, an internal order from the Film Committee had established a collection called kinoletopis’, in which the most significant non-fiction sequences from the Soviet history would be grouped together.15

Until the war, the items in this collection seem to have been supplied mainly by the Moscow news studio. In the absence of documentation covering the period between the collection’s creation and the Soviet Union’s entry into the war, it is difficult to determine what criteria were used to collect these negatives (and positives). In any case, in October 1941, the collection, which then comprised around 500,000 metres of film (around 60,000 metres of it filmed since the German invasion), was evacuated to Novosibirsk.16 The NKVD archive in Lefortovo was evacuated to Chkalov (as the town of Orenburg in the southern Urals was then known).

No more deposits were made following this double evacuation. However, around 205,000 metres of film collected by the Central Studio of Documentary Films, which had not left Moscow, was later added. The collection is now stored in a Mosfilm warehouse.17

In August 1943, Boltianski carried out an inventory, and realised just how varied the material in the collection was: entire films of all lengths and genres sat alongside shots that did not belong to any film at all. He also noted the absence of clear, rigorous criteria for selection, indexing and conservation, and drafted a memorandum calling for a sorting process and a charter defining these criteria.18

Definition and Selection Criteria

Based on these proposals, the head of the news and documentary department, Fedor Vasil’chenko, presented a report on September 14, the broad outlines of which then formed the basis for a decision taken in October.19 According to the report, which mainly concerned footage produced during the war, the first step was to separate the wheat from the chaff and to retain in the collection only “documents of historical value, providing a general overview of the different periods and stages in the life of the country,” based on index entries that could be modified according to the situation. Footage that did not meet these criteria, had been deposited by chance or existed in duplicate form would have to be discarded. “Reels” (filmoroliki) would be created from the material, compiling footage according to a periodisation defined by Party historians. Five major stages of the conflict would serve as a basis. Within these reels, footage of military operations filmed at the front would alternate with footage filmed behind the lines during the same period. An editorial committee comprising historians and filmmakers would help to identify and classify the footage.20 The negatives created as a result were no longer to be touched; extracts required to create newsreels and documentaries could only be taken from duplicate negatives. The rest of the material – that is, the footage which was not suitable for the reels – had to be returned to the studio’s film library (filmoteka), which would be the main source for day-to-day production.

Some professionals warned about the subjective nature of the work: classification and selection involve making choices. Moreover, editing, which creates “links” or meaning, ran the risk of turning the archive into an artistic creation.21 For this reason, the use of intertitles or voice-overs was forbidden, and the reels would be accompanied by precise descriptions of the shots (montazhnye listy) to aid understanding, but also to prevent the material from being deliberately or accidentally misinterpreted at a later date. These descriptions, drawn up a posteriori, should not be confused with the camera operators’ caption sheets, which were produced at the time of or just after filming; one reason such confusion is likely is that the same Russian term, montazhnye listy, is used for both the descriptions and the caption sheets.

Drawing Up Shooting Plans

In addition to the processing and classification of footage that had already been filmed, there was demand for additional filming (of sites of major battles, scenes of destruction, heroes of military operations, etc.) to better reflect events already recorded on film and build up the special kinoletopis’ collection. The organisation of shooting plans was set out in a clear, precise circular from Vasil’chenko that was sent to film crew leaders on all fronts in early December 1943. It began as follows:

Camera operators often come across events that they do not film, either because they fall outside the scope of the Journal’s regular work, or because the footage cannot be included in the Journal at that time. At the same time, such footage is often of exceptional value for the history of the Great Patriotic War and for the kinoletopis’. In the future, these materials will be exceptionally powerful documents, showing in their true form the full power of the Soviet people’s struggle against the Germano-fascist invader, their struggle and all its difficulties.22

Vasil’chenko reminded camera operators of the historic role they had to play in documenting the conflict. “Everything must be filmed,” he wrote – and that included evidence of atrocities and destruction. All operators were expressly asked to film “the severest and harshest things” and to do so “without submitting to the usual aesthetic requirements.” This “professional obligation” extended to traces of the “new order” imposed by the German Reich: seizure of property, forced labour, humiliations, discriminatory inscriptions, signs hung around the necks of those condemned to death. These demands duplicated or merged with those of the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission for the Investigation of Nazi Crimes (ChGK), which gathered evidence of the enemy’s crimes and examined the footage sent in by camera operators.

Vasil’chenko also called for coverage of the dark, unofficial side of the Great Patriotic War, including the sacrifices endured by soldiers, retreats and even defeats. This initiative represented a genuine alternative to official history as it is usually practised. Admittedly, its perspective was still rooted in a system of representation dependent on Soviet conventions. But Vasil’chenko’s work anticipated a time when history could be written differently, with particular attention paid to the fates of individuals and their suffering:

Thus, in the material filmed in Leningrad [...] during the first winter of the siege, scenes of famine and destruction of extraordinary force were recorded. This material was not made public, and only part of it was later included in LENINGRAD V BORBE.

The vast majority of these shots can only be made public at a later date. [...] But it all has to be filmed. We must not let ourselves be guided solely by the urgencies of the day, but consider the facts from the point of view of our overall struggle against the Germano-fascist invader, from the point of view of “tomorrow.” [...] Camera operators must show initiative and capture on film the facts and phenomena that are important and necessary for history.

As examples of such facts and phenomena, he mentions the victims, the human losses, the corpses of combatants, the faces of the seriously wounded, the blood, the material losses, the fires, the heroes, life in the occupied territories and the crimes perpetrated and destruction caused by the enemy.

Results and Limitations

As is so often the case in Soviet history, and particularly in the history of cinema, these ambitions came up against material problems. A report presented in July 1944 sounded the alarm and prompted a frank discussion within the Film Committee. Shub, who had by then become the lynchpin of the enterprise, played a very active part in it, to the extent that the team working on the kinoletopis’ collection was now referred to as “Shub’s group.”23 Working conditions were appalling and cramped, the conservation and storage conditions were alarmingly bad and the team lacked essential equipment, in particular editing tables. The legal status of the reels was unclear: according to the decree of 1936, it was compulsory to hand over the footage to the archives, but the decree had not been ratified, or was somehow lost, so the studio staff could pick and choose as they wished, and the collection risked receiving only footage discarded by the studios.

Apart from the material issues of preservation, the content left much to be desired. Up until the end of 1943, as Shub explained at the meeting, only “scraps” had been received, that is, material that had not been used to edit the newsreels that had been shown in cinemas and that would not immediately be used for other productions (and so would remain in the studio’s film library). These “scraps” included cutaways, landscape shots and the like, which were of no interest for the kinoletopis’ collection. As Shub pointed out, there was both too much and too little, or not enough of what was needed: the best shots and material on the most important subjects had already been taken. It was therefore necessary to skim (removing all the “superfluous” elements) and request copies/duplicate negatives for certain edited films.

At the same time, these negatives were being requested by the NKVD archive; as mentioned above, a 1938 provision required negatives of newsreels to be deposited two years after their release. Worse still, due to a Sovnarkom decree of May 1941, the NKVD now demanded that the negatives be deposited after one year, despite the fact that, according to film professionals, the staff of these archives were poorly trained, conservation conditions were poor, dialogue was difficult and the consequences of evacuating their holdings to Chkalov were unknown. Added to this, the NKVD also began directly demanding kinoletopis’ footage. The discussion on July 18, 1944 prompted the committee to attempt to regain full control of the NKVD archive or, at the very least, to request a postponement of the transferral of the negatives for five or even ten years, arguing that this was necessary for production purposes and that it would be difficult to obtain the requested items once they had been deposited. Admittedly, as filmmaker Sergey Gerasimov, who had recently been appointed Vasil’chenko’s replacement as head of the newsreel department, pointed out, the Film Committee’s archives at Belye Stolby were also far from ideal for conservation, but the staff there were competent, and the Scientific Research Institute for Film and Photography (NIKFI) could contribute its knowledge (in particular, its photochemical expertise) to help improve the situation.

On the day of the meeting, Shub’s team24 declared that, for the first phase of the war (the period of the retreat), they had selected 37,000 metres (out of a total of 170,500 metres). There were also another 16,000 metres of negatives still to be analysed and sorted. Precise descriptions of the selected material had been produced (sometimes shot by shot, sometimes just by subject). For the second period, 380,000 metres had been selected, part of which came from newsreels and films (duplicated). This left around 600,000 metres to be processed, which is why Shub asked for additional staff: an assistant, a negative cutter and a stock manager. She got her wish, and generally speaking her work was strongly supported by Film Committee managers.

What criteria governed these choices? What footage was rejected and destroyed? It is difficult to say. In the documentation of the creation of the kinoletopis’, the criterion of “Importance of the subject for history” seems to have been left to the discretion of archivists and any historians or military personnel that were called in ad hoc (who do not seem to have played a very active role). These included “war heroes,” speakers at international conferences and leading political and military figures. Furthermore, the first phase of the conflict – as the first archivists noted as early as 1943 – had been very poorly documented. Shub pointed out that the period of the retreat had been filmed in such a way as to give the impression that it was a Soviet-led offensive.25 There were also plans to retrieve footage from news studios outside Moscow and to approach the camera operators themselves to assist with documenting footage whose provenance was unknown. For the time being, however, little is known about these contributions and interactions. Similarly, it is poorly documented when and under what circumstances certain caption sheets written by the camera operators were added to the RGAKFD archives.

The Subsequent Fate of the Collection

Let us recall the sequence of operations that took place after filming. Firstly, the original negatives were taken from the camera and sent to Moscow. Upon arrival, they were developed at the studio, and then numbered, printed and edited. The negatives of edited films were (in theory, at least) then transferred to the NKVD archive. Unedited sequences, some edited sequences that had been discarded for reasons of political or military censorship, or because the footage was too harsh and disturbing, and some internegatives from broadcast films were, after a while, passed on to the kinoletopis’, where they were combined with other material, either immediately or at a later date. Some shots from the original footage were removed from the negatives and incorporated elsewhere (newsreels or films). Before being used for other editions or transferred to the kinoletopis’, these materials were stored for an indefinite period of time in the central studio’s film library, known as the filmoteka.26

The material that remains in the kinoletopis’ is thus: 1) incomplete in terms of the original negatives; 2) most often dissociated from the caption sheets; 3) combine with other footage. It was arranged into compilations of around 250–300 metres, the average length of a reel or conservation unit. These reels were described shot by shot, sometimes many years apart, with or without the original caption sheets completed by the camera operator who filmed the footage.

According to the original procedures (established in the 1920s to 1930s), all items were to be deposited in the NKVD archive. But storage conditions, which were already less than ideal, worsened in the postwar period, and the archive had limited capacity. Moreover, the way the institution functioned did not allow the easy access necessary for both identification work and documentary filmmaking. For these reasons, as we have seen, as early as 1944 there were calls to preserve the Belye Stolby archives, which were under the authority of the Film Committee (from 1946: the Ministry of Cinema). Pending an official decision, it was decided to keep the kinoletopis’ collection under the aegis of the Central News Studio.27 However, this collection was later transferred, in several phases that have yet to be precisely dated, to the NKVD archive, which later became the Krasnogorsk archive, following the relocation from the Lefortovo fortress (1953). Meanwhile, the non-fiction films seized from the enemy were – perhaps due to lack of space, perhaps due to a desire to keep them away from the capital or because of their association with the great mass of fictional “trophy” films – transported from Germany to Belye Stolby, where they still remain, at least to the best of our knowledge.

Although the two archives – that of the NKVD, which held the complete reels, and the kinoletopis’, which was long stored at the Central News Studio – were ultimately reunited, the kinoletopis’ remained a separate collection and was not merged with the other material. As a result, we sometimes find one and the same film and its associated material under the same title but different inventory numbers, with sequences that are sometimes duplicates and sometimes different because one is not the final edited version.

The kinoletopis’ reels were generally assembled by grouping sequences according to names of places, regions, phases of military operations, etc., in accordance with decisions taken in 1943. Consequently, within a reel it is only possible to determine the origin and date of a particular shot if we have the original caption sheet for it. The “out-of-camera” negatives were replaced by reels assembled from heterogeneous material at a later date. This is confirmed by the very high number of splice marks found in the archive data sheets and the variable quality of the individual elements (some shots in the reels are internegatives).

The Consequences Today: Some Challenges and a Few Ideas for Consideration

The archive negatives digitised as part of the VHH project are not first-generation, unlike the amateur material in American collections. Successive or parallel interventions by various organisations had an impact not only on the work of camera operators but also on editing and conservation practices. The final products we find in the archives are the result not of individual but of collective effort, with each person playing their part, at their own level, with or without the assent or support of others. The last person in this complex chain – which included stages of censoring, editing, sorting and assembling before conservation – had the last word. This means the kinoletopis’ material must be considered incomplete and lacunar by its very nature. In this respect, it is very different from much of the Anglo-American material. Moreover, it is the result of a collective effort in which it would be futile to look for the distinctive style of a single individual. This does not mean, of course, that we should abandon the work of identification that allows us to attribute shots to a particular filmmaker. But we should avoid approaches that seek to highlight the exceptionality of an auteur’s vision.

Among the paper materials accompanying the visual documents, in addition to the caption sheets (not all of which have been preserved) and the montazhnye listy compiled for the kinoletopis’ the archives also hold the rabochie kartochki (technical data sheets), which we initially thought might be an interesting source. In reality, they proved disappointing when we examined them. The plurality of reasons for intervention in the material poses difficulties for researchers: a splice mark may indicate the removal of footage so it could be added to a compilation, a deletion or a simple technical measure (such as a repair of one or more damaged frames). Deciding between these possibilities is a real challenge, especially as most of the interventions left no written trace. Editors do not write down the number of cuts and splices they make, or the reasons for them. Only the archivist records them to document the technical quality of the material.

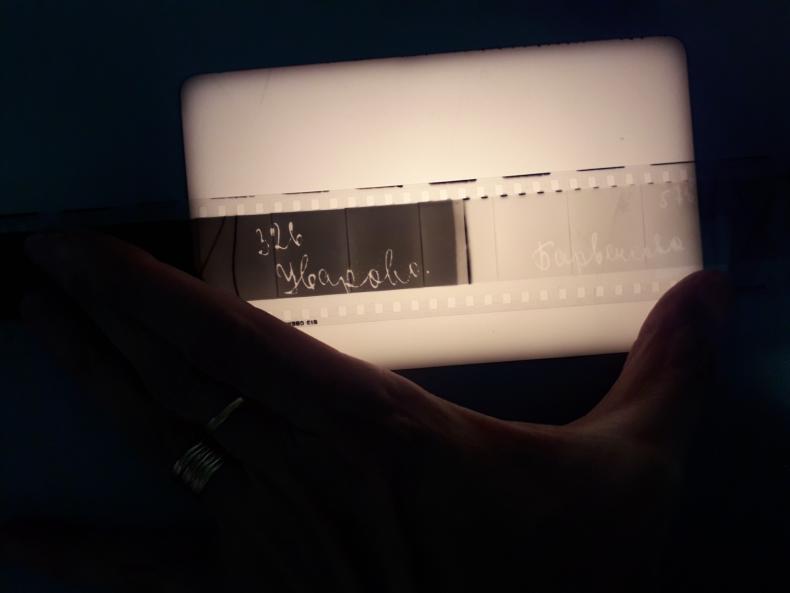

The complex genealogies of the reels also affected the digitisation choices made as part of the VHH project. Notably, as the negatives have been removed from their original contexts, it is normal for us to find several different film brands on the same reel (Agfa, Kodak, DuPont, Soyouz, etc.). Handwritten notations between sequences (titles, sometimes dates, places, names) and original numbers noted on the film (known as “studio numbers”) can be used to associate items with caption sheets and thus enable them to be identified.

Finally, in the context of the VHH project, the decision to select only extracts from the kinoletopis’ collection for digitisation, by contrast with the complete digitisation of the films that were edited and broadcast, is fully justified, since the reels were assembled according to sometimes arbitrary or irrelevant criteria (footage from the same region or period, alternating sequences from the front and behind the lines) or simply because a reel had to be completed.

The archives that have been preserved, and in particular the kinoletopis’ collection, are the result of a twofold process: firstly, conservation (but a conservation process that involved selection and thus exclusion); secondly, special orders.

The often incomplete transfer of material has created difficulties for identifying documents. Other problems include changes in numbering (between the studio and the archive); materials of varying provenance being grouped together, sometimes in very large compilations (PARTISANS / PARTIZANY 1942–1943 has sixty-two reels!); the great difficulty in retracing the history of edits to the footage; the risk of confusing different types of material: rushes, outtakes of edited films, shots that were never used; material being deposited at a later date – firstly following an order from the ministry in 1947 to put studio film libraries in order, particularly that of the Central Studio of Documentary Films (CSDF), and then in a second wave from 1953 onwards, as attested by the RGAKFD’s entry registers. Later, were added the “scraps” from feature films that had been rereleased in shortened versions. Adding to the heterogeneity, shot-by-shot descriptions were often made by archivists who watched the footage at their desks many years after it was originally recorded. These descriptions, depending on whether or not they were produced by competent individuals who took the trouble to integrate other information, may be of great use or very little.

Only by patiently comparing the footage with the preserved caption sheets and cross-referencing with photographs of the same locations and other paper sources can we identify the dates and locations of filming more precisely. In some cases, handwritten annotations on the film allow us to distinguish one sequence or footage from another or find a title or original studio number – all of which can be used to pinpoint a date, location or camera operator.

The Subsequent Life of the Footage: Between Unexpected Discoveries and Wilful Misuse

Despite abuse of the kinoletopis’ collection by studio directors, who would sometimes plunder material from it, some treasures have nonetheless been preserved. If time is devoted to identifying them (as was done in the VHH project), it may be possible to make major historical discoveries. The VHH project, for example, was able to pick out twelve hours of historically significant footage, including a few newsreels and documentaries, by means of an extensive selection process.

For a long time, this collection remained relatively inaccessible, at least to foreigners. From the 1960s/70s onwards, Soviet documentary filmmakers used extracts from the collection for medium and feature-length films about World War II. They made new associations and often recycled the same footage. However, extracts relating directly to the Holocaust, a subject that was still taboo in the USSR, were excluded. From 1991 onwards, the kinoletopis’ was opened up to a wider audience, including documentary filmmakers and foreign researchers, and became a privileged source for World War II history. Once again, after a while, the same sequences ended up being used in many productions, due to the lack of other identified footage. The VHH project was able to expand the range of available sources; however, the material has been inaccessible since the severing of institutional relations following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Productions from the Soviet period should not be overlooked, however, as some of them may be of unexpected interest. One example is the thirteenth episode in the TV series THE UNKNOWN WAR, entitled “The Liberation of Ukraine” (number 26193 in RGAKFD Archive, 1979), which uses numerous pieces of atrocity footage. The director, Lev Danilov, was a veteran himself. He had served as a private soldier, not as a camera operator, although he was a student at the VGIK at the time. “The Liberation of Ukraine,” which we did not include in the digitisation work commissioned for the VHH project, contains extracts from footage filmed in Kyiv at the time of the liberation (October–November 1943) that are not to be found in the kinoletopis’. A montage shows shots of Kharkiv (presented in the film as Babyn Yar), preceded by a sequence of atrocities from locations including Kerch and Poltava. Some brief shots seem to have been filmed at Babyn Yar: the geographical layout, and the ravine in particular, are identifiable. There are two possible hypotheses: either these shots come from material that we have not yet identified (which could be either in the Krasnogorsk collections or elsewhere), or they have been taken directly from a negative we know of, but that has not been duplicated. That shows we are still a long way from having a complete picture. Admittedly, the extermination of the Ukrainian Jews is not explicitly mentioned in this film, even though the voice-over speaks of the Ukrainian, Russian, Byelorussian and Jewish victims. However, the presence of such images is an exception in documentary productions of the time. It should be noted that this was a Soviet–American co-production.

Danilov’s interest in then little-known chapters of World War II history persisted later on: in the 1990s, he made several documentaries about episodes in the Soviet history of the war that have now been repressed once again: the Katyn massacre, the defection of Andrey Vlasov and the fate of the shtrafniki.28

The second use of the material I would like to draw attention to occurs in Sergei Loznitsa’s film BABYN YAR: CONTEXT (2021), which again features a montage of still and moving images from different sources (both Nazi and Soviet, with the two political regimes placed on an equal footing). The work done on this material goes far beyond simple clean-up: it has been colorised, slowed down or sped up; sound has been added; certain details have been highlighted by zooming in or inserting shots. The absence of a voice-over seems to assert a position of neutrality. In reality, the editing and inserts induce an interpretation that is far from neutral. This interpretation highlights not German policies of discrimination but local complicity, which the director understands as “context.” The selection and editing of images emphasise the behaviour of local populations – who are capable of reversing their opinions, submitting to one regime (Soviet) only to then embrace another (Nazi) and then backtrack again three years later. The film makes no attempt to explain these reversals of opinion, or to precisely show the social, economic, cultural and political context or history of these regions. Instead, these aspects are glossed over in favour of disturbing simplifications, since the film selects only episodes that highlight the reversals of opinion (the new rulers being welcomed with fanfare, mass gatherings, etc., in scenes that bear striking visual similarities). The populations of Lemberg (Lviv) and Zhitomir are assimilated to those of Kyiv, leading to an essentialisation of the “Ukrainian nation.” The Babyn Yar massacre is immediately preceded by a sequence showing explosions in the centre of Kyiv, attributed to pro-Soviet resistance fighters, which would have enraged the Germans. By placing these two excerpts together, the film’s editing implicitly suggests that the massacre may have been triggered by these resistance actions. Elsewhere, the absence of commentary on the images of the Lviv pogrom (filmed by German camera operators) and the faces selected by the Nazi camera operators from among the Soviet soldiers taken prisoner is dangerous and disturbing, as these images were intended to emphasise the victims’ degradation.29 Equally problematic is the sound recording of the hangings of those convicted of war crimes at the Kyiv trial in 1946. The editing work tends to present a “global image” of the Ukrainian people as “collaborators” who were actively involved in the crimes of both the Soviet and the Nazi regimes. Loznitsa is accustomed to hiding behind his auteur status to avoid questions about the political significance and impact of his work (in this case, even the photographs have had sound added), which merit detailed study. He claims the aims of his films are purely aesthetic – quite the opposite of what the kinoletopis’ team recommended.

The use made of kinoletopis’ footage in other Soviet and post-Soviet productions requires in-depth study so that we can determine how widespread these phenomena of reuse were and precisely chart the variations in meaning ascribed to the footage according to the period and the filmmakers’ aims (and, perhaps, those of their sponsors).

Conclusion

The availability of a vast amount of footage filmed during the reconquest of Nazi-occupied territories, and in particular footage documenting the crimes committed there, has already contributed to a better understanding of the Shoah, its temporalities, its modes of action, its scale and its precise geography, and will undoubtedly continue to do so. However, if these archival materials are to be properly understood, and if the halo of suspicion that has long surrounded them is to be dispelled, their analysis needs to be accompanied by rigorous reflection on the entire chain that led to their production (which organisations created the footage, for what purposes, with what material resources and professional culture?), distribution (or non-distribution) and preservation. The path these materials have taken between 1942–1945 and 2024 has been marked by multiple changes in preservation procedures, institutional attachments and, due to the country’s various political transformations, the accessibility of the footage to the public.

By the time the footage was deposited in the kinoletopis’, in or after 1941/42, the archive had already been shaped by a history of prior decisions and procedures, and was managed by staff (archivists, editors, managers of various levels) who had themselves been shaped by a particular, highly ideological professional culture. That culture’s values were expressed in a hierarchy of what is and is not historically important, which led the archive’s staff to privilege certain sequences to the detriment of others. However, the Soviet desire to control the entire documentary chain, the institutionalised opacity, the practice of secrecy as a way of working and exercising power and, finally, the general view that careful preservation could prove politically and administratively useful led to the conservation (and not the destruction) of thousands, even millions of metres of film for the greater benefit of historians and, in theory, ordinary citizens, even if that footage was excluded from any editing.30

Finally, if we wish to gain a full picture of the relevant operations in all their complexity, we must not underestimate the personal dimension: the involvement (or non-involvement) of certain filmmakers, editors and archivists in the process of sorting, indexing and associating; their eagerness to pass on certain footage to repressive institutions or, conversely, their resistance to doing so; the weight of rivalries between different bodies, which led to hesitations and contradictory choices that are reflected in material acts – cutting, deleting, assembling, editing – which are potentially crucial to how we interpret these materials.

- 1

See Chapter 2 of Jeremy Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012).

- 2

Thanks to funding from the French National Research Agency (ANR), the CINESOV team, coordinated by Valérie Pozner and Alexandre Sumpf, was able to spend three years (2013–2016) studying Soviet cinema from the period 1939–1949.

- 3

Victor Barbat, “Une cinémathèque de papier: La tentative déçue de créer un musée du cinéma en URSS,” Cahiers du CAP 9 (November 2021): 93–122.

- 4

Federal Law of August 22, 1996, no. 126-F3 (on state support for cinema in the Russian Federation), Art. 3, “General terms” [O gosudarstvennoj podderzhke kinematografii Rossijskoj Fedeeracii. Glava I. Osnovnye polozhenija. Stat’ja 3. Osnovnye ponjatija].

- 5

“ׅ’O peredače central’nomu arhivu RSFSR negativov foto-snimkov i kino-fil’m, imejuščih istoriko-revoljucionnyj interes’: Postanovlenie Soveta narodnyh komissarov RSFSR ot 4 fevralja 1926,” in Sistema dejstvujuščego kino-zakonodatel’stva RSFSR, ed. I. S. Piliver and V. G. Dorokupec (Moscow: Tea-Kino-Pečat’, 1929), 64–65. This initiative extended a resolution that was taken on February 15, 1924 (less than a month after Lenin’s death) and expanded the following year in a decree of January 16, 1925, whose aim was to collect photographic and cinematographic negatives featuring Lenin (ibid., 68–69).

- 6

Ibid., 67.

- 7

Esfir’ Shub, “ׅNeigrovoe kino,” Kino i kultura 5 (1929): 6–11.

- 8

V. N. Batalin and G. E. Malyševa, Istorija Rossijskogo arhiva kino-fotodokumentov: Hronika sobytij 1926–1966 (St Petersburg: Liki Rossii, 2011), 38.

- 9

RGALI, f. 2057, op. 1, d. 377.

- 10

Sergej Bratoljubov, Na zare sovetskoj kinematografii: Iz istorii kinoorganizacij Petrograda-Leningrada 1918–1925 godov (Leningrad: Iskusstvo, 1976), 28–29.

- 11

Barbat, “ׅUne cinémathèque de papier.” See also the documents in the RGALI’s Boltianski collection, published in Kinovedčeskie zapiski 84 (2007): 26–42.

- 12

G. M. Boltianski, Kino-hronika i kak ee snimat’ (Moscow: Kino-pečat’, 1926).

- 13

K. M. Anderson et al., Kremlevskij kinoteatr (Moscow: Rosspèn, 2005), 295–297 (RGASPI, f. 17, op. 114, d. 598, ll. 49–51).

- 14

See V. I. Fomin et al., Letopis’ rossijskogo kino 1930–1945 (Moscow: Materik, 2007), 407–408 (RGALI, f. 2456, op. 4, d. 21, ll. 14–25).

- 15

This is the internal order from the Film Committee that the professionals and managers refer to in the rest of the documentation that we examined, but we have not yet been able to find the precise wording.

- 16

Report by F. M. Vasil’chenko dated September 14, 1943, RGALI, f. 2456, op. 1, d. 831, ll. 65–71. Reproduced in V. I. Fomin, Kino na vojne: Dokumenty i svidetel’stva (Moscow: Materik, 2005), 751.

- 17

Ibid., 752.

- 18

RGALI, f. 2057, op. 1, d. 377.

- 19

I. G. Bol’šakov, “ׅPrikaz Komiteta po delam kinematografii: “O meroprijatijah po ulučeniju raboty po sistematizacii dokumental’noj kinoletopisi,’” October 22, 1943, RGALI, f. 2456, op. 1, d. 831, ll. 62–63. Reproduced in Fomin, Kino na vojne, 754–755. See also the discussion in RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 136.

- 20

The committee was headed by Vasil’chenko. Its members included Boltianski, Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Ilya Kopalin and historian Izrail Razgon, who had just been awarded the Stalin Prize.

- 21

This point is developed by Victor Barbat (“ׅUne cinémathèque de papier”), who refers to a very frank discussion between managers, executives and editors at the Central News Studio about Boltianski’s proposals that took place in September 1943 (RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 136).

- 22

F. M. Vasil’čenko, “Cirkuljarnoe pis’mo Glavkinohroniki načal’nikam frontovyh kinogrupp,” December 2, 1943, RGALI, f. 2451, op. 1, d. 186, ll. 15–16 ob, in Fomin, Kino na vojne, 755. My translation from Russian.

- 23

RGALI, f. 2456, op. 1, d. 923 (protocol, report, transcript and decision, ll. 131–148). Part was published in Fomin, Kino na vojne, 762–767.

- 24

The team consisted of only three people (RGALI, f. 2456, op. 1, d. 923, l. 144).

- 25

Ibid., 764.

- 26

This film library was used for the studio’s day-to-day production. It should be noted that the documentation we consulted is relatively silent about its holdings, contents, classification categories, etc. Only reports of disorder and deterioration, following inspections and leading to warnings, can be found in the archives from 1947 onwards.

- 27

The relationship between the CGAKKFD (the official name of the NKVD archive), Belye Stolby (which became the Gosfilmofond in 1948) and the CSDF (Central Studio of Documentary Films) had been marked by constant rivalry and conflict ever since the 1930s. On the period 1951–1952, see Batalin and Malyševa, Istorija Rossijskogo arhiva kino-fotodokumentov, 89.

- 28

Shtrafniki were penal military units. Service in them was considered a form of punishment in lieu of imprisonment or capital punishment. See Lev Danilov’s films SHTRAFNIKI / PENAL BATTALION (PLOTS FROM ORDER NO. 227) (1989), K VOPROSU O KATYNI / ON THE KATYN QUESTION(1989) and DOS’E NA GENERALA VLASOVA /DOSSIER ON GENERAL VLASOV (1990).

- 29

On the use and trivialisation of images of perpetrators, see Fabian Schmidt and Alexander Oliver Zöller, “ׅAtrocity Film,” Apparatus: Film, Media and Digital Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe 12 (2021): 1–80. For an analysis of photographs of the Lviv pogrom, see Thomas Chopard, “ׅLe pogrom de Lviv, juin 1941,” Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe, https://ehne.fr/fr/encyclopedie/th%C3%A9matiques/guerres-traces-m%C3%A9moires/shoah-mises-au-point/le-pogrom-de-lviv-juin-1941. And on the pogrom itself, see John-Paul Himka, Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust: OUN and UPA’s Participation in the Destruction of Ukrainian Jewry, 1941–1944 (Stuttgart: Ibidem Press, 2021).

- 30

For a general yet in-depth study of the questions raised by the Soviet archives, see Sophie Cœuré, “ׅLe siècle soviétique des archives,” Annales: Histoire, Sciences sociales 3–4 (2019): 657–686.

Anderson, Kirill, and Leonid Maksimenkov. Kremlevskij kinoteatr. Moscow: Rosspèn, 2005.

Barbat, Victor. “Une cinémathèque de papier. La tentative déçue de créer un musée du cinéma en URSS.” Cahiers du CAP éditions de la Sorbonne 9 (November 2021): 93–122.

Batalin, Viktor, and Galina Malyševa. Istorija Rossijskogo arhiva kino-fotodokumentov. Hronika sobytij 1926–1966. Saint-Petersburg: Liki Rossii, 2011.

Boltjanskij, Grigorij. Kino-hronika i kak ee snimat’. Moscow: Kino-pečat’, 1926.

Bratoljubov, Sergei. Na zare sovetskoj kinematografii. Iz istorii kinoorganizacij Petrograda-Leningrada 1918–1925 godov. Leningrad: Iskusstvo, 1976.

Chopard, Thomas. “Le pogrom de Lviv, juin 1941.” Encyclopédie d’histoire numérique de l’Europe. https://ehne.fr/fr/encyclopedie/th%C3%A9matiques/guerres-traces-m%C3%A9moires/shoah-mises-au-point/le-pogrom-de-lviv-juin-1941.

Cœuré, Sophie. “Le siècle soviétique des archives.” Annales. Histoire, Sciences sociales 3–4 (2019): 657–686.

Fomin, Valerij, et al. Letopis’ rossijskogo kino 1930–1945. Moscow: Materik, 2007.

Fomin, Valerij. Kino na vojne. Dokumenty i svidetel’stva. Moscow: Materik, 2005.

Hicks, Jeremy. First Films of the Holocaust, Soviet cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Himka, John-Paul. Ukrainian Nationalists and the Holocaust. OUN and UPA’s Participation in the Destruction of Ukrainian Jewry, 1941–1944. Stuttgart: Ibidem Press, 2021.

Piliver, Iosif, Dorogokupec, V. G. Sistema dejstvujuščego kino-zakonodatel’stva RSFSR. Moscow: Tea-Kino-Pečat’, 1929.

Schmidt, Fabian, and Alexander Oliver Zöller. “Atrocity Film.” Apparatus. Film, Media and Digital Cultures in Central and Eastern Europe 12 (2021): 1–80.

Shub, Esfir’. “Neigrovoe kino.” Kino i kultura 5 (1929): 6–11.