Depicting Atrocities

Ethics of Sharing Holocaust Images

Table of Contents

Soviet Film Footage and Professional Practices (1941–1945)

Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis')

A Travelling Archive

Zinovii Tolkachov’s Graphics from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek Death Camps

People with Disabilities as Nazi Victims on Screen and Paper

Forgotten: Film Documents from the Liberated Camps for Soviet POWs

Depicting Atrocities

Reflections on the Geography of the Holocaust Based on Soviet Film Footage

Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv

Filming Auschwitz in 1945: Osventsim

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Högner, Anna, and Fabian Schmidt. “Depicting Atrocities. Ethics of Sharing Holocaust Images.” Research in Film and History 6 (2025): 1–26. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/23558.

Engaging in a project titled The Visual History of the Holocaust - Rethinking Curation in the Digital Age (VHH) means delving into the complex ethical questions of handling incredibly violent imagery. The aim of the project was to trace prints of the so-called “liberation footage” in various archives and museums and to create state-of-the-art digital copies of the material. Access copies of the films were uploaded to a publicly accessible platform that offers complex analytical tools for analysis, annotation, and comparison. It links the visual testimonies to other visual and written sources. The platform provides access to an unprecedented quantity of visual sources on the Holocaust, and while offering a valuable tool for the engagement with this historical event, it is also embedded in an ethical discourse that has accompanied any use and reuse of Holocaust-related visual material from the very beginning.

The Holocaust has always been an exception to widely accepted standards for the public depiction of death, whether in the context of war, natural disasters, accidents or personal tragedies. Here, ethical restrictions could be and often were expected to be suspended. The conditions faced by military personnel, especially camera crews, during the liberation of German concentration and labor camps surpassed, in terms of cruelty and dehumanization, what had previously been considered acceptable wartime collateral. The attitude of most Germans immediately after liberation to deny any knowledge of these atrocities, of deeds that had often been committed in their immediate neighborhood, was a crucial reason for the relentless display of these images. For the moment, the images of liberation replaced the memory that the perpetrators and bystanders were in the process of suppressing. The imperative to expose the extent of this breach of civilization, the unique status of the liberation footage as testimony and evidence and their role in the reeducation programs justified, at the time, a temporary suspension of conventions. Yet, this suspension persisted and has shaped the collective consciousness of Western societies since 1945.

This choice was by no means a self-evident one. The Allied cameramen also provided a great deal of less gruesome footage that would have sufficiently documented the camps. The Soviet approach of rather filming women mourning over their murdered relatives pursued an alternative strategy of generating empathy rather than shock. The confrontation of the German public with the images of corpses from the concentration and labor camps in reeducation films immediately after the war was initially a means of contradicting denial. At the time, this was already a breach of conventions, but it was supposed to summarize the abysmal dimension of the German camp system. The emaciated survivors from camps all over Europe and the piles of equally emaciated corpses from Bergen-Belsen were chosen for the purpose to shock an audience that was expected to deny responsibility.

Nonetheless, or perhaps exactly because of this, within the Visual History of the Holocaust project we were confronted with this breach of convention on a daily basis. The images we worked with made us aware of our own ethical attitudes toward the depiction of individual suffering and death, and thus of the different ways in which they can be displayed in public, contextualized in research and publications, and presented in lectures, panels at conferences, or symposia. These considerations were with us throughout the project. They were brought up in break room conversations with colleagues and discussed at two of the final conferences. Still seeing room for some final considerations, we decided to give a brief intervention of what we saw as the most prevalent questions during the closing conference in Paris in 2022.

While examining the subject, we were surprised how wide the range of ethically accepted approaches towards visual evidence of the Holocaust was, even within the VHH project. The team consisted of people with different professional backgrounds. Some had spent much of their professional lives studying the subject and had already developed a sense of distanced and pragmatic professionalism toward these images. In addition to seasoned media scholars or Holocaust historians, the team included translators, media archivists, or restorers with little or no familiarity with this kind of images. During the digitization and contextualization phase of the project, staff spent months digitizing and subtitling footage, tagging content, verifying automatically generated annotations, and interlinking film works, context materials, people, and places. The approximately 70 hours of footage compiled for the VHH project comprised all of the film material that had been shot during the liberation of the concentration and extermination camps and of the atrocities committed by the Germans against civilians in the occupied territories in Eastern Europe. The portion of these images typically encountered by researchers and known to the public as iconic or emblematic Holocaust imagery turned out to be only a fraction of a much larger body of visual testimony that the editors in 1945 had deemed inappropriate for reeducation films.

Aware of this, the project adopted a considerate policy of informing all staff to monitor their emotional response to working with this material and to pause or even stop working with certain types of images if they noticed signs of stress or anxiety. Alongside this cautious approach, which focused on individual responses to these images, guidelines were put in place to reflect on how these images might be framed and selected in public or semi-public settings such as conferences or lectures. The project’s Ethical Guideline sets out general curatorial principles for working with Holocaust-related material to “ensure the respectful treatment of cultural materials including material of a sensitive nature, and preventing its abuse,” and to “ensure that dignity and the moral rights of people depicted in historical records, or people whose stories are told through these records, is respected.”1 Since presenting the results of research on the visual traces of genocide necessarily involves showing the object of study, the principle of respect for those depicted and the scholarly interest in these images are in a constant tension. At the beginning of the Visual History of the Holocaust project, some general rules were established for the use of images in presentations and lectures. These included avoiding overly violent images. Visual sources from the project should not be shown out of context, cropped or otherwise distorted, or used as background images in PowerPoint presentations. One of the frequently used images for the announcement of events reflects this approach very well. It is a frame of 16mm footage that the American filmmaker George Stevens shot during the liberation of Dachau (Figure 1). We can see the back of a photographer taking a picture of one of the wagons of the infamous “Dachau train.” The corpses of the prisoners are barely recognizable, but still visible behind his figure.

Obviously, as the project progressed, not every image in every presentation could be chosen as carefully. When it came to presenting the results of our research, whether in public or in the professional environment of the project’s final conferences and other meetings, we often encountered a certain professional routine in dealing with atrocity images that affected the balance between the premise of dignity and the use of these images as a source. In the light of these experiences, we began to question once again the specific ethical problems posed by a project that focuses on the Holocaust and that is specifically designed to provide public access to these materials. We wondered about the ethical boundaries of showing images of dead and mutilated corpses — even in a context where the conditions of their production and their historical background are well reflected. Particularly in the context of Holocaust studies, viewing and showing very challenging images is an integral part of research activities and is often seen as something to be endured for the sake of the scholarly endeavor and not always is the aforementioned balance between the purpose of demonstration and respect “for the people whose stories are told through these record”2 at the center of attention. The first draft of this paper that circulated shortly before the closing conference of the VHH resulted in a notable number of participants modifying their presentations towards using less atrocity images. One might conclude that the prevailing culture of displaying atrocity images is in many cases the result of desensitization rather than a deliberate intention.

At the same time, questions of ethics, especially in relation to a historical event that will soon be accessible only through written sources, photographs, and visual and sound recordings, cannot be addressed without considering one’s own cultural, social, and historical position. We, the authors of this article, were born and raised in Germany, the successor state of the perpetrator nation. And we should bear in mind that we might therefore be particularly concerned to avoid anything that could contribute to a revictimization of any sort. At the same time, as a colleague from another successor nation of the perpetrator state pointed out, it might be also questionable from this position to voice any prescriptive statements about what can and cannot be shown. From their experience families of survivors often seemed to express less concern about their relatives’ privacy when it came to Holocaust education, research, or remembrance than did the descendants of the perpetrators.

In the light of the growing distance between us and the historical events of the Holocaust, examining and reexamining audiovisual and written records gains importance. Remembrance will not be possible without detailing the unimaginable horrors of the camps and the other atrocity sites. This is becoming even more prevalent in the light of growing antisemitic tendencies, revisionism, and Holocaust denial. This essay is therefore less concerned with the question if these images should be shown publicly, and more with the question of how. We began our inquiry with a series of questions:

– Under which circumstances can the portrayal of people in a situation that has stripped them of all that normally constitutes humanity be justified?

– How can the distress, the shock, or even the empathy of watching these images constitute a teaching or learning experience?

– Do we need the visual evidence of the Holocaust to really understand it?

– Should learners/viewers have a say in how much distress they are willing to endure?

At the beginning of our research, we discussed various moments that we felt touched our ethical boundaries, and we began to wonder about the potential of these images to teach, but also to hurt: the dignity of the victims as well as the well-being of those exposed to them. This consideration is very much in line with what Ruth-Anne Lenga, Program Director at the UCL Centre for Holocaust Education, identifies as the two main concerns in the contemporary field of Holocaust education regarding atrocity photographs: the “anxiety that distressing images have the potential to harm students – both in terms of their emotional well-being and, relatedly, in terms of their capacity to learn” and their ability to “damage and distort the memory of the individual men, women and children depicted, imposing upon them an abstracted and dehumanising frame.”3 Lenga proposes a framework for the work with atrocity images at schools that excludes certain types of images.

As stated above, the Holocaust is a domain where ethical norms regarding the sanctity of the private spheres of both victims and spectators tend to be suspended. If we look at the moment when the first images of the liberation were released to a wider audience, it becomes clear that shock as a means of countering denial has been a part of our handling of Holocaust imagery from the beginning. In spring 1945, the first newsreel edits of images taken by the US Signal Corps appeared. The voice-over emphasized the footage’s disturbing nature while pointing out its evidentiary value. In the opening statement to the Nuremberg trials, Robert Jackson, the chief U.S. prosecutor, described the strategy behind using moving images of Nazi crimes as evidence:

We will show you these concentration camps in motion pictures, just as the Allied armies found them when they arrived, and the measures General Eisenhower had to take to clean them up. Our proof will be disgusting and you will say I have robbed you of your sleep. But these are the things which have turned the stomach of the world and set every civilized hand against Nazi Germany.4

Today, these images are part of our visual history used, re-used, and superimposed to tell about the horrors of the Nazi crimes – for future generations to deal with and learn from. But how and what do images of atrocities teach us? Documentary filmmaker and author of the film NIGHT WILL FALL (GB 2014) Andre Singer argues in an interview: “I think the imagery in Bernstein’s film and mine, if used in the right context, can only help understanding. [...] We can only understand the horrors of war if we use images like this.”5 Singer emphasizes the unique capability of visual evidence to convey historic truth. But does the subjection of a learning individual to traumatic images necessarily prevent future trauma by “understanding” the horrors through visual documents? Reflecting on Singer’s stance on this subject Natalie Borman points out that

[the] question, what images can really tell and teach us is rooted in expectations that graphic portrayals of suffering, trauma, and violence should provoke viewers/students into action. Faith in the image’s ability to do so is predicated, in turn, on the assumption that graphic depictions of atrocity will be intense enough to horrify viewers into responding.6

But shock or even a strong sense of compassion might not necessarily translate into what Andre Singer calls “understanding” or even political action. Learning from this evidence therefore requires some kind of transition from an initial emotional response to a conscious evaluation of how and in what particular circumstances these images came to be, what they show, and what they do not show.

There is one aspect of the atrocity images that is sometimes lost in the discussion, and that is the fascination of gazing at dead bodies, a dilemma or moral conflict we can already find in Plato’s tale of Leontius who is passing the bodies of executed criminals outside the gates of Athens:

He felt the urge to look at them; at the same time he was disgusted with himself and his morbid curiosity, and he turned away. For a while he was in inner turmoil, resisting his craving to look and covering his eyes. But finally, he was overcome by his desire to see. He opened his eyes wide and ran up to the corpses, cursing his own vision: “Now have your way, damn you. Go ahead and feast at this banquet for sordid appetites.”7

In the end, the curious Leontius gives in to his desire to see the hanging corpses. When the first films about the German concentration camps hit the US-American market, the media reported on shocked audiences. But it didn’t take long for the moment of “shock” to dominate the publicity surrounding these atrocity films and the demand for more and more of these images grew. The magazine Film Daily claimed in May 1945 that “atrocity pix” of “Buchenwald and other Nazi concentration camps are reported to have attracted the largest audience since the newsreel pictures of the Hindenburg Graf-Zeppelin disaster” and audiences and theater owners complained publicly when the authorities began to censor them.8 From the point of view of the 21st-century Holocaust education, which aims to foster independent, ethically grounded individuals capable of resisting the appeal of fascist subjectivization, one might even argue that there is a need for an effect opposite to shock: a necessary desensitization through repeated exposure to the images of atrocity; to rid oneself of this fascination and to achieve a neutral, detached view of these images. But does one want to lose sensitivity to the cruelty of these images?

The presentation of results during our research project often led to situations in which images of tortured or murdered people were shown, like the images of the piles of corpses in Dachau, the stashed corpses in Klooga, or the decapitated corpses in the Anatomic Institute of Gdansk, whose heads are stored in a metal bucket. Inserted into PowerPoint presentations they lingered above the audience that tried to focus on what the speakers had to tell. Images that at that point had lost all their startling potential as they were processed, digitized, enhanced, sometimes cropped to fit a presentation slide, enlarged or slowed down to prove a specific argument. They no longer shocked, but served the purpose of a historical testimony that could reveal more information about the historical situation that led to their creation. At the same time, the individuals depicted in these images were exposed to an analytical yet indifferent gaze. As onlookers we run the risk of acquiring a certain professional casualness in dealing with these visual testimonies of human suffering. In her essay on the representation of death in documentary space, film theorist Vivian Sobchack describes the “professional gaze” of the camera, which is “marked by ethical ambiguity, by technical and machine-like competence in the face of an event which seems to call for further and human response.” She distinguishes this gaze from the “humane stare” inscribed in most atrocity footage, which she describes as “frozen and hypnotized gaze [...] generated by the incredibly inhumane and incomprehensible, by a disbelief that what one is seeing is existentially possible.”9 The “inhuman stare” that Sobchack finds in the published or iconic portions of the liberation footage can be reconstructed in even greater detail in the raw material available on the research platform of the VHH project. A close examination of the original raw material shot by the Signal Corps cameramen in Ohrdruf or the British Army Film and Photographic Unit in Belsen reveals a certain dramaturgy. At first, these soldiers filmed the piles of corpses from a distance, as part of the larger structure of the camp. Only gradually did they dare to get closer and eventually singling out individuals. Within the succession of shot sizes, the close-ups appear, or can be interpreted, as the attempt to look for something human, for an individual fate within the faceless mass of bodies these soldiers encountered. Here, the professional gaze is already compromised, anticipating the discomfort we want to address in our essay. Both types of gaze on the events that Allied soldiers were confronted with are inscribed in these materials: an incredulous “humane stare” that mirrors Plato’s tale and a distanced, analytical “professional gaze.” What is inscribed in the images may be the cinematographers’ struggle to come to terms with what they found in front of the camera. When we use this footage in an academic, museum, or educational context, we still have to find ways to come to terms: with the atrocities depicted, but also with our own “layered gaze,” to quote a concept coined by film historian Jamie Baron, on the intentions of the producers of the original document, on the context the image is presented in and finally our own historic position.10

Is there a way to work with these images without losing the ability to be truly touched by the fate of the people who populate them, without being hurt by them? We searched for curatorial approaches to similar problems and found several, ranging from obscuring parts of the image or omitting certain details to the careful presentation of these images within a rich contextualization through other objects and or explanatory texts. One fascinating example deals with the recent discussions of the colonial legacy in Vienna. It is the short film KÖRPER FORMEN / CASTING BODIES (AUT 2018) by Jannik Franzen. The film is about plaster casts found in a basement of the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna and a particular piece of archival film footage that records the making of one particular cast, that is a cast made from a living person during World War I. The subject being copied in plaster is a person of color, a prisoner of war from one of the colonies. In order to respect this person’s rights, Franzen cut out those parts of the film that show the victim and therefore leaves only fragmented parts of the action, protecting the image of the victim while at the same time redirecting the attention towards those guilty of performing what we now recognize as an act of humiliation.

While the analysis of the different regimes of gaze inherent in the production and the use of perpetrator footage is also typical of our work as Holocaust historians, it is questionable whether this particular approach would be generally applicable to Holocaust-related projects. Not only because we seldom have both perpetrators and victims in one image. It still should be acknowledged as a theoretical and aesthetical approach very different from what we find normal in dealing with Holocaust imagery: an attempt to respect the dignity of this unknown prisoner of war.11

Raoul Peck uses a similar technique with the opposite result in his presentation of photographs showing evidence of the sexual exploitation of indigenous women by European colonists. In the first episode of his series EXTERMINATE ALL THE BRUTES (USA 2021), black bars are used to cover up the breasts of young women who are shown in the arms of officers in khaki uniforms. Peck’s intervention in the images redirects our gaze — not at the perpetrators, as in the example above, but at the act of concealment itself and at the nakedness of their victims. By hiding what is usually hidden in Western societies, Peck forces us to replicate a sexualized, colonial gaze on these women’s bodies.

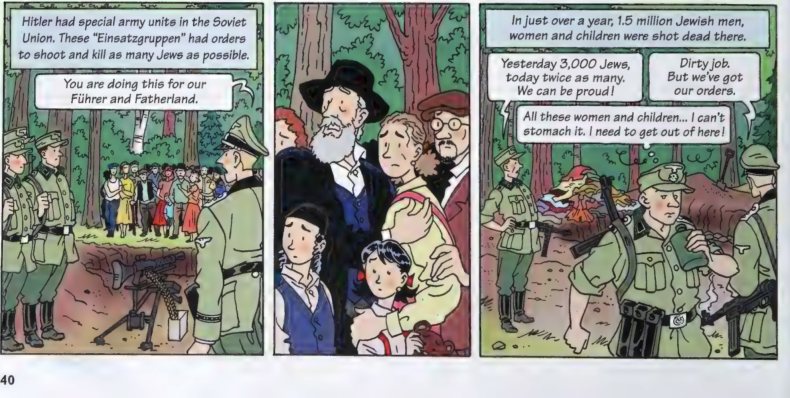

One approach that might avoid the pitfalls of obscuring parts of visual testimonies is to refer to them by means of a narrative ellipsis. In their graphic novel The Search (2007), comic artist Eric Heuvel and Author Ruud van der Rol chose to narrate the horrors of the Holocaust without explicitly depicting atrocities. Heuvel explained his concept in an interview with the German newspaper Die Welt:

We thought long and hard about how we should portray this. The comic is primarily aimed at students between the ages of 13 and 16. We decided that we didn’t want to show the atrocities that really happened. Piles of corpses, for example, are not shown. We showed the events before and after, but not the terrible deeds. After all, it is not possible to show the full extent of the horror that really happened. It can’t be captured in drawings or in any other way.12

Eric Heuvel emphasizes that an image will always fall short in conveying the true horrors of the Holocaust and leaves it to the readers to fill in the gaps in the narrative. But how do institutions whose mission it is to grant access to visual and textual sources about the Holocaust manage the difficult balance between presenting images that show the reality of the crimes committed during the Holocaust to a diverse audience, while at the same time not losing sight of the victims, the sensitivity of visitors, and the general question of how much shock is appropriate? Most memorial sites reacted to the general tendency in memory studies in recent years by adapting a very careful handle of Holocaust-related visual testimonies. The Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz, a memorial at the site of the conference where high-ranking Nazi officials set in motion what led to the deportation and murder of European Jews, recently updated their exhibition displays. The museum removed most of the iconic photographs or film stills of atrocities, in the spirit of creating an exhibition that would be open for everyone. Maintaining a low threshold and a barrier-free approach towards narrating the conditions under which the persecution of Jews and the Holocaust could unfold, these were replaced with less explicit photographs that still document the situation, showing perpetrators and victims but not in a context that humiliates the victims.

The Imperial War Museum is another memory institution that has recently opened a new exhibition focusing on the Holocaust, the Holocaust Galleries. The footage and photographs taken by British soldiers during the liberation of the Belsen and Neuengamme concentration camps are central to the Museum’s holdings. They are shown at the end of a comprehensive account of the history of the Holocaust. As James Bulgin, Head of Content at the Imperial War Museums explains, careful consideration has been given not to present exhibition objects in a way that provokes “an emotional response, or to serve the explicit purpose of shocking visitors. To that end, such imagery is only reproduced at the historic scale it would have existed.”13 By preserving photographs and moving images at their original size rather than enlarging them, attention is drawn their materiality and their original function as a visual source. Moreover, visual testimonies are presented within a rich context, as visual records that bear witness to a factual truth they depict. The exhibition concept avoids presenting images or the people they portray. Individuals and visual sources alike have a history and are not displayed, as Bulgin emphasizes, in a “metonymic function, whereby [the] intention is to demonstrate or indicate how horrendous the Holocaust was a holistic event rather than to support engagement with the specific moment or event.”14 The Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz and the Holocaust Galleries are two examples of Holocaust memorials and museums that explicitly try not to use elements of shock or means of subjectification to convey a historical factuality. To put it differently, both provide an explicit answer to the question raised at the beginning of this article about how much suffering is acceptable to display in order to achieve an educational result.

There are also other, more radical positions on Holocaust education. “The reversed gaze,” a teaching method practiced by Robert Jan van Pelt carries the shock treatment, as initially introduced by the Allies in the 1940’s to prevent any forms of denial, to an extreme. In an essay, the author describes an exercise he does with participants of a guided tour through the Auschwitz Memorial. The situation, or experiment described here recurs strongly on a well-known motif of the Holocaust imagery: a person behind barbed wire. Although it does not explicitly evoke these images, it is still a telling example of the underlying motivations in the context of Holocaust education:

When we begin our visit at 9:00 in the morning, we are alone at the gap; most visitors following the prescribed route will need at least two hours to reach this point. I give the group some simple instructions. I ask half of them to form a line along the inside of the fence, with two meters between each person and standing 1.5 meters from the barbed wire. I ask the other half to go through the gap and do the same on the outside of the fence, directly opposite someone on the inside. Every time, there are some puzzled looks and awkwardness. But having traveled a long distance to “experience” Auschwitz under my guidance, everyone soon falls into position, facing someone else through two layers of barbed wire. I then ask them to simply look that person in the eyes, and to not stop until I say so. Before we start, I clarify: “This is not a staring contest. You may blink as much as you want. The question is not who is stronger, but what you see when you observe another person through a barbed wire fence, and what happens inside you when you know yourself to be observed through a barbed wire fence.” Then we begin.

The same reactions usually unfold: someone breaks down in tears within the first minute or two; one or two people break eye contact and step out of line; and after five minutes, the remaining faces show severe stress, even pain. By this point I call an end to the exercise and ask the group to explain what had just happened.15

This example is interesting because it argues from morally secure grounds. Van Pelt is convinced to have history on his side, and that he is doing a good thing by shaking people awake. Not only does it involve or display a certain moral rigor, but it also involves a second vital aspect: trust. As the author describes, his test subjects find the setup awkward, but they go along because they trust his expertise. This is where a problem arises. In the situation created by Van Pelt, pain is afflicted in the name of a trustful transfer of knowledge. Now, what are the implications of this example?

There is a difference between confronting someone with cruel events from the past and risking that the person is shocked or suffers, and making the suffering an explicit goal, like in the previous example. This may sometimes be a difficult and narrow distinction to make, but in general most people will agree that inflicting pain is not the primary goal of Holocaust education. Now, what about the idea that pain is an inevitable part of understanding what the Holocaust is or was? To some extent this is true, and the notion of the horrors of the camps has been a recurring trope in educational efforts to frame the Holocaust imagery from the beginning. But should the individual have a say in how far this pain is acceptable? Isn’t a distanced view of the matter important in order to have the necessary objectivity? Is it really pain that was transported by the Belsen images of piles of corpses, the images that clearly had an impact on how the Holocaust was remembered and how the collective remembrances reacted to it, turning it into the seminal “never again” event? Maybe there is a path between being stifled by the horrendous events these images depict and a detached professional gaze. Analyzing the work of Peter Weiss, literary historian Alan Itkin comes to an interesting conclusion that refers to the individual but transcends questions of piety and personal rights. For Itkin, Weiss’ literary and artistic confrontation with the atrocities of the Holocaust compels us to pick sides: “This image is a provocation: either to accept the observers’ disregard for the dead man and thus to take a position among those who are indifferent to his fate or to be outraged by the casual way they have erased the individual and thus to stand on the side of the dead.”16 Indeed, choosing sides requires an act of distancing oneself from the image and the gaze it imposes. It requires an effort to reverse one’s own gaze: away from the depicted towards the lens of the camera. Instead of losing oneself in a state of shock, disgust, empathy, or habituality, it lays the groundwork for what Bertolt Brecht coined as “a consciously critical observer.”17 Such an act of distancing, or “alienation,” doesn’t restore the dignity that the perpetrators have taken from the people depicted, but it does at least acknowledge it. As a viewer, one can choose to look beyond the humane gaze or the professional gaze of the camera and relate to what and who is being depicted and the specific historical situation in which it is embedded.

Is there a way to mediate the elements of shock and rationalization in studying the visual history of the Holocaust? We believe that any involvement with this material requires room for an analytical distance to the material. One way might be to provide space for reflective criticism and active engagement with what and who is depicted. This analytical distance is something that the Visual History of the Holocaust project allowed researchers and assistants to have when annotating the material in the project’s digital media platform. Before users access a film, they encounter a complex analytical interface that displays each media object in relation to its place of creation, to the people involved, and to photographs, text documents, and other resources. This media management and search infrastructure provides tools for in-depth analysis of the visual resources showing the liberation of the camps, allowing the material to be bookmarked, segmented, and related. By actively engaging with the liberation footage, rather than simply viewing it, users have the opportunity to discover new layers of meaning through an analytical approach to the atrocities shown (Figure 7).

As our discussion of different curatorial approaches to framing atrocity footage and photographs shows, shock as a means of conveying the truth of the Holocaust cannot, and perhaps should not, be entirely avoided. However, as presenters, we should make an effort not to show these images carelessly. During presentations, the audience has less opportunity to look away, and for them as spectators in that case, a space for analytical distance may not always open up. Visual material needs to be carefully selected, framed, and discussed so as not to induce feelings of morbid curiosity, distress, or a dehumanizing gaze in the audience. Handling these images ethically means striking a balance between a justified scholarly interest, the positionality of those confronted with the imagery, and, as the VHH Ethics Guideline states, the “dignity and the moral rights of people depicted in historical records.”18 It is about keeping the instruments of shock at bay by acknowledging the fact that shock is inherent in the subject. At the same time, it is necessary to be aware and to stay aware about the historical circumstances under which these films and photographs became an important part of the collective imageries of the Holocaust: as means of countering widespread denial of the atrocities they depict.

The examples from other contexts also show that some approaches, such as the anonymization of victims, will not be applicable in the context of Holocaust research. Liberation footage is a visual record of an event that is becoming increasingly distant to us. Any intervention in the material runs counter to a legitimate interest in keeping the memory of these events alive, to learn more about them, by, for example, identifying the victims — and restoring their humanity. For these reasons, obscuring faces would be highly questionable.

Using ellipsis to refer to atrocities, by indirectly showing, leaving a gap to be filled by the readers, as we saw in the graphic novel The Search can be a valuable path to choose for some, especially in educational contexts. But as the example of Haus der Wannsee-Konferenz and the Holocaust Galleries show, dealing with these sources will always be a matter of carefully choosing and contextualizing visual sources in exhibition contexts.

Returning to the question posed at the beginning of this text, we would argue that there are no a priori ethical limitations to showing and analyzing images of atrocities. But, depending on the context, ethical considerations might impose methodological limitations on their treatment and call for an adequate dispositif to show them. When atrocity images or atrocity footage are shown in an exhibition, presentation, or in an educational context, there should be space to consider the victims. And there should be space to address feelings these images evoke. This could be done by placing the image itself at the center of the discussion and asking what we know about the circumstances in which it was taken and what we know about the fate of the people depicted in it.

- 1

Camille Blot-Wellens, Michael Loebenstein, “Deliverable D3.3 Ethics Guideline,” last modified December 2019, 3, https://www.vhh-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/VHH_Publication_D3-3_Ethics-Guideline_v1-5_2019-12-31.pdf.

- 2

Ibid.

- 3

Ruth-Anne Lenga, “Seeing Things Differently: The Use of Atrocity Images in Teaching about the Holocaust,” in Holocaust Education: Contemporary Challenges and Controversies, ed. Stuart Foster, Andy Pearce, Alice Pettigrew (London: UCL Press, 2020), 196.

- 4

Robert H. Jackson’s opening statement before the International Military Tribunal: “Second Day, Wednesday, 11/21/1945, Part 04,” in Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal. Volume II. Proceedings: 11/14/1945-11/30/1945 (Nuremberg: IMT, 1947), 98–102, https://www.roberthjackson.org/speech-and-writing/opening-statement-before-the-international-military-tribunal/.

- 5

André Singer cited in: Stuart Jeffries, “The Holocaust film that was too shocking to show,” The Guardian, January 9, 2015, https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/jan/09/holocaust-film-too-shocking-to-show-night-will-fall-alfred-hitchcock.

- 6

Natalie Bormann, The Ethics of Teaching at Sites of Violence and Trauma: Student Encounters with the Holocaust (Boston: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018), 38.

- 7

Plato, The Republic, 439e–440a, trans. Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985).

- 8

Unknown, “Atrocity Pix Breaking Newsreel House Records,” The Film Daily, May 3, 1945, 6.

- 9

Vivian Sobchack, “Inscribing Ethical Space: Ten Propositions on Death, Representation, and Documentary,” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 9, no. 4 (1984): 294–298.

- 10

Jamie Baron, Reuse, Misuse, Abuse: The Ethics of Audiovisual Appropriation in the Digital Era (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2020).

- 11

KÖRPER FORMEN / CASTING BODIES (Ausschnitt/excerpt), Jannik Franzen, AUT 2018, https://vimeo.com/994022281.

- 12

Die Welt, March 4, 2008, our translation.

- 13

James Bulgin in an email to the authors, 2023.

- 14

Ibid.

- 15

Robert Jan van Pelt, “Auschwitz and the Architecture of the Reversed Gaze,” e-flux, October 2020, https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/monument/351167/auschwitz-and-the-architecture-of-the-reversed-gaze/.

- 16

Alan Itkin, “Bringing Up the Bodies: The Classical Concept of Poetic Vividness and Its Reevaluation in Holocaust Literature,” PMLA 133, no. 1 (January 2018): 107–123.

- 17

“Der Zweck dieser Technik des Verfremdungseffekts war es, dem Zuschauer eine untersuchende, kritische Haltung gegenüber dem darzustellenden Vorgang zu verleihen.” Bertolt Brecht, Gesammelte Werke Band 15 (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1967), 341.

- 18

Blot-Wellens, Loebenstein, “Deliverable D3.3 Ethics Guideline,” 3.

Baron, Jamie. Reuse, Misuse, Abuse: The Ethics of Audiovisual Appropriation in the Digital Era. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2020.

Blot-Wellens, Camille, and Michael Loebenstein. “Deliverable D3.3 Ethics Guideline.” Last modified December 2019. https://www.vhh-project.eu/wp-content/uploads/VHH_Publication_D3-3_Ethics-Guideline_v1-5_2019-12-31.pdf.

Bormann, Natalie. The Ethics of Teaching at Sites of Violence and Trauma: Student Encounters with the Holocaust. Boston: Palgrave MacMillan, 2018.

Brecht, Bertolt. Gesammelte Werke, Band 15. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1967.

Heuvel, Eric. The Search. Amsterdam: Anne Frank House, 2007.

Itkin, Alan. “Bringing Up the Bodies: The Classical Concept of Poetic Vividness and Its Reevaluation in Holocaust Literature.” PMLA 133, no. 1 (January 2018): 107–123.

Jackson, Robert H. “Second Day, Wednesday, 11/21/1945, Part 04.” In Trial of the Major War Criminals before the International Military Tribunal. Volume II. Proceedings: 11/14/1945-11/30/1945. Nuremberg: IMT, 1947. https://www.roberthjackson.org/speech-and-writing/opening-statement-before-the-international-military-tribunal/.

Jeffries, Stuart. “The Holocaust Film That Was Too Shocking to Show.” The Guardian, January 9, 2015. https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/jan/09/holocaust-film-too-shocking-to-show-night-will-fall-alfred-hitchcock.

Lenga, Ruth-Anne. “Seeing Things Differently: The Use of Atrocity Images in Teaching about the Holocaust.” In Holocaust Education Contemporary Challenges and Controversies, edited by Stuart Foster, Andy Pearce, Alice Pettigrew, 195–220. London: UCL Press, 2020.

van Pelt, Robert Jan. “Auschwitz and the Architecture of the Reversed Gaze.” e-flux, October 2020. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/monument/351167/auschwitz-and-the-architecture-of-the-reversed-gaze/.

Plato. The Republic. 439e–440a. Translated by Richard W. Sterling and William C. Scott. New York: W. W. Norton, 1985.

Sobchack, Vivian. “Inscribing Ethical Space: Ten Propositions on Death, Representation, and Documentary.” Quarterly Review of Film Studies 9, no. 4 (1984): 294–298.

Unknown. “Atrocity Pix Breaking Newsreel House Records.” The Film Daily, May 3, 1945. 1, 6.