Educational Film in East Germany (GDR) in 1950–1990 in Perspective of the “Grammar of Schooling”

Table of Contents

Screening Propaganda

In Defense of Culture

The Raw Materials of Celluloid Film

Wholeness and Nature

The Austrian Province as Subject and Space of Action in Educational Film Practices

The Development of Educational Cinema for Schools in the Soviet Union in the 1930s

Educational Film in East Germany (GDR) in 1950–1990 in Perspective of the “Grammar of Schooling”

No Instructions, Just Some Advice

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: von Engelhardt, Kerrin. “Educational Film in East Germany (GDR) in 1950–1990 in Perspective of the ’Grammar of Schooling.’” Research in Film and History 5 (2023): 1–41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/22730.

1. Introduction

This article1 aims to take a closer look at both sides and, on the one hand, explore the hopes and expectations which were associated in the GDR with the use of educational films and, on the other hand, investigate possible reasons for their failure.2 For that reason, the article looks at the intentions of the East German film pedagogy using sources on educational film theory. But, remarkably, there also was extensive research on the impact and practices of educational film use throughout the 1960s to 1980s. Thus, in the history of the GDR educational film and its usage, two perspectives open up a potentially revealing field of tension: The production-side expectations published in brochures by the responsible institutions and in manuals are contrasted with the results of practical studies commissioned since the 1970s on the effectiveness of audio-visual teaching materials in the GDR. Even if the central role of the teacher was always rhetorically unquestioned, it can be assumed that the use of audio-visual teaching aids was associated with efforts to assert control on the part of the school authorities, as they have already been historically documented in the case of textbooks.3 Therefore, the technical equipping of the classrooms in GDR’s schools can be reasonably understood as an irritation of teacher-centeredness and, thus, also as an irritation of what educational history calls the grammar of schooling.4

“What is important is that the educator understands how necessary this technology is in order to make the pedagogical process more rational and effective, and that in the future the teacher’s activity can no longer be ‘technology-free.’”5 With this statement, Ewald Topp emphasised in his published dissertation the importance of basic technical equipment like audio-visual teaching aids in schools in the German Democratic Republic (GDR, East Germany, 1949–1990).6 With this degree, he had qualified for the position of Deputy Head of the GDR Institute for Teaching Aids of the Academy of Pedagogical Studies (Institut für Unterrichtsmittel der Akademie der Pädagogischen Wissenschaften der DDR) in 1971. The institute was responsible for the planning, production, and authorisation of all teaching materials that could be used in GDR schools.7 The thorough curriculum reform around 1970 in the GDR was accompanied by new didactic teaching concepts that included the demand to use audio-visual teaching aids effectively. Therefore, Topp’s publication can also be understood as an official viewpoint on the use of audio-visual teaching aids. From an economic point of view, he considered “films, slides, slide series with sound recordings, projection transparencies and television broadcasts” to be the “most rational means” for programming teaching and learning processes.8 Programming was understood as detailed and technology-based pre-planning of teaching units to increase the effectiveness of knowledge acquisition.9 But, in emphasis of this appeal, a problem as old as the debates on the school educational film also appeared: the seemingly opposing position of the teacher versus the technical teaching aid.

Since the Weimar Republic (1918–1933), sceptics who feared distraction and a diminution of teachers’ authority had opposed enthusiastic advocates of educational film.10 Regarding educational media use in general, the GDR differs structurally from the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG, West Germany) after World War Two.11 Whilst in the eastern part, between 1949 and 1990 the production and use of teaching aids were centrally controlled,12 in the western part of Germany a freedom to use teaching materials – the so-called Lehrmittelfreiheit13 – was established. Of course, a certain caution is called for here, since it can be assumed that teachers were able to use grey areas and leeway in the GDR on the one hand, and that licensing procedures and financial possibilities set limits to freedom in the FRG on the other.14 However, the old tension between technology-enthusiastic innovators, also on the part of the school administration, and conservative sceptics in the ranks of the teachers – the familiar reservations against the moving image – was emphasized differently in the GDR: The most frequently and officially stated reason for the hesitant use of educational film in schools was the teachers’ lack of knowledge about its use. This explanation seems nearly logical in a system where every novelty was authoritatively decided centrally, economically pre-planned and ideologically legitimised. Therefore, already in the planning phase of novelties, elaborate academic training and further education programmes for teachers were initiated. However, a less official explanation was provided by unpublished commissioned surveys of educational practices at the time, which showed that there was still a lack of technical equipment in schools in the GDR during the 1980s. From a historical perspective, the inertia of teaching practices combined with teachers’ reserve towards new technologies may also have been the cause.

For some time, historical educational research has used the concept of the grammar of schooling as a category of analysis, and also as an explanation for the structurally conditioned failure of school reforms. David Tyack, William Tobin, and Larry Cuban attributed conservatism and inertia of the school against reforms to the persistence of an established grammar of schooling and its regulated structures.15 The concept of a grammar of schooling means “regular structures and rules that organize the work of instruction”16 such as age-group classes, subject teaching, curricula, the division of time units, etc., and which determine the organisation of teaching and the operation of the modern school. This grammar is described to be resistant or selective to reform processes. Daniel Tröhler and Jürgen Oelkers conceptualized teaching materials as part of this grammatical configuration.17 Thus, school, classroom and educational aids (films as well as other teaching and learning materials) are to be understood as structurally related with instructional practices. Carsten Heinze uses this concept to methodize the historical research of textbooks and to grasp the textbooks’ acquiring of meaning.18 It is therefore not too far-fetched to use this concept for the history of the GDR educational film as well. Moreover, the concept of a grammar of schooling can be used in order not to lose sight of the basic functional mechanisms of school and teaching (also in their historical genesis) and to possibly also capture what is typical of the GDR. But it is precisely in the complex field of tension between teachers, teaching aids and teaching technologies that it becomes apparent that the grammar of schooling is not an ontological constant. Teaching practices may be inert to reform, but they are not permanent and are certainly ambivalent. As Marcelo Caruso has therefore pointed out, it is problematic to view school reforms in a purely binary way – i.e., as either failed or successful – as this reduces the complexity of such processes from the outset.19 Therefore, reforms should, as far as possible, respond flexibly to the established grammar of schooling.20

In this article Heinze’s descriptions are used as a kind of guideline. Heinze distinguishes four dimensions of the grammar of schooling: grammar of educationalization (takes into account the social consensus on delaying the child’s participation in society by means of an educational phase),21 of knowledge acquisition (focuses on what knowledge is to be taught, how it must be shaped for this purpose, and how it is to be learned),22 of institutionalization of instruction (considers the places and forms of teaching),23 and of regulation (issues the legal conditions of the school system and its maintenance).24 In the following we will look at these dimensions by altering the order a little bit. To start off, in the GDR, the dimension of educationalization25 – interlinked with the modern childhood concept – was not fundamentally questioned, albeit the propagated polytechnic education led to an early introduction of the children to the field of work.26 Moreover, childhood in the GDR was highly institutionalised and thus politicised.27

2. Educational Films and the Dimension of Regulation

In general, institutionalisation is linked to regulation. The dimension of regulation28 was of great importance in the GDR for the production and distribution of teaching aids. All teaching materials were planned and produced in a centrally institutionalized fashion and for every school in the GDR.29 In the course of the curriculum reforms around 1970, great importance was also attached to ensuring that the various teaching media for the individual school subjects were coordinated. To this end, detailed lesson plans were drawn up that not only specified the lesson content for the teacher, but also the forms of instruction such as blackboard pictures or media. In addition, catalogues were published indicating for the available educational films whether they were to be used compulsorily in class or only for extracurricular purposes.

The regulation in the field of educational film was in the 1970s fully institutionalized and divided into three areas: The Institute for Teaching Aids at the Academy for Pedagogical Studies (Institut für Unterrichtsmittel der APW) in Berlin was responsible for the area of schools, with cooperation partners at universities and teacher training colleges. The Central Office for the Rationalisation of Teacher Training (Zentralstelle für Rationalisierungsmittel der Lehreraus- und -weiterbildung, ZRL), based at the University of Education in Erfurt, was primarily responsible for the area of teacher training. And the Institute for Film, Image and Sound (Institut für Film, Bild und Ton, ifbt) and the Central Institute for Higher Education (Zentralinstitut für Hochschulbildung) in Berlin were responsible for the area of higher education.30 To understand the complex structures of educational film institutions, see the scheme (Tab. 1):

|

Area of Responsibility |

||

|

School |

Teacher Training |

Colleges and Universities |

|

1950: Zentralinstitut für Film und Bild in Unterricht und Wissenschaft – Central Institute for Film and Images in Science and the Classroom |

||

|

1954: Deutsches Zentralinstitut für Lehrmittel (DZL) – German Central Institute for Teaching Aids |

||

|

1962: Deutsches Pädagogisches Zentralinstitut (DPZ) – German Central Institute of Pedagogy |

1964: Institut für Film, Bild und Ton (ifbt) – Institute for Film, Image and Sound |

|

|

1970: Institut für Unterrichtsmittel (IU) der Akademie der Pädagogischen Wissenschaften der DDR (APW) – Institute for Teaching Aids at the Academy for Pedagogical Studies |

1970: Zentralstelle für Rationalisierungsmittel der Lehrerausund Weiterbildung (ZRL) – Central Office for the Rationalisation of Teacher Training |

|

|

1979: Zentrum für Audiovisuelle Lernmittel (ZAL) an der Humboldt Universität zu Berlin – Centre for Audio-visual Teaching and Learning Resources at the Humboldt University in Berlin |

||

|

1982: Zentralinstitut für Hochschulbildung – Central Institute for Higher Education) |

||

These institutions were not only responsible for the production and distribution of teaching aids such as films, but also for research on their usage and effectiveness in practice. In particular, the areas of school and teacher training and further training were interlinked in empirical studies on the effectiveness of media use in teaching. In contrast, the publications in the academic sector (universities and Fachhochschulen) had more of a systematising and recommending character. Here, best practice examples for the use of teaching and learning materials were presented or lecturers were advised on the creation of their own teaching materials. However, there are manifold interconnections between the authors and institutions in the field of educational film research in the GDR.

The educational film research at these GDR institutions can be roughly divided into three phases: the 1950s were dominated by consolidation, the 1960s and 1970s focused on rationalising teaching, and the 1980s emphasised the aspect of knowledge acquisition. After the consolidation phase, which also discussed questions of conditioning in the sense of Ivan Petrovich Pavlov (1849–1936) for the educational film sector, research on the use of teaching aids began, which was strongly characterised by a centralist claim to planning. Studies of the 1960s and 1970s refer to the optimal illustration of subject-specific knowledge.31 The background to this was a general frontal teaching arrangement. Since the 1970s, one key concept was the “programming” of teaching and especially of learning processes with the help of audio-visual media. In this context, cybernetic concepts were prominently discussed. On the planning side, it was expected that the expenditure on school equipment would be reflected in corresponding results – such as sustainable knowledge acquisition, especially for pupils with learning difficulties.32 In the 1980s, more attention was paid to intellectual practical acquisition activities in certain subjects. In addition, however, information science approaches continued to be pursued, which certainly still bore behaviourist traits. In the school sector, at the APW in particular, the research results were not only used in the evaluation of admission procedures, but also in the production of new teaching materials.33 In the following, the article will look at studies from the 1970s and 1980s that dealt more intensively with the means of the educational film and its practices. In all studies, reference was made to both international socialist and non-socialist research, with interpretations framed in the obligatory political manner. Nevertheless, with some catch-up in the 1970s, western research methods (particularly quantitative research designs) on media use were adapted.

3. Educational Films and the Dimension of Knowledge Acquisition

Teaching aids are an element of the grammar of schooling and play a central role in teaching practices and knowledge acquisition.34 In the GRD, the dimension of knowledge acquisition played an important role for pedagogical discussions on audio-visual teaching aids, thus also on educational films, which were analysed (and designed) under the keyword ‘effectiveness.’ However, it was not only about the question of how knowledge could be effectively conveyed, but also about shaping the attitudes towards this knowledge. Here the GDR’s film pedagogues discussed the concept of the “association complex” as a special form of didacticizing: The aim was to link factual content with acoustic signals and visual patterns on film in such a way that they could be effectively learned and recalled. In this understanding, strongly abstracted knowledge was usually concreted and illustrated by examples of application and thus at the same time marked in its value for practical life. In addition, emphasis was placed on the thesis that particularly low-performing students benefitted from the use of audio-visual media. In the GDR, the educational film was understood as an instrument for efficient teaching and learning. This instrumental understanding runs as a claim through the commissioned studies on educational films. The “control function” of audiovisual media was beyond question:

A flip-foil, a series of slides, a complex educational film etc. not only transmit a lot of information, but they also exert an influence on the sequence and the way in which the learner processes this information, i.e., they control the learning process. It is crucial for this aspect of the effectiveness of an av LLM [audiovisuelles Lehr- und Lernmittel, audio-visual teaching and learning aid] that both creators and users are aware of this objectified control and take it into account in a purposeful way when designing and using it.35

This is stated in the handbook Audiovisuelle Lehrmittel: Methodik ihrer Anwendung und ihre Gestaltung (Audio Visual Teaching Aids: Methodology of Their Use and Their Design) which was first published in 1973 by Rolf Fuchs and Klaus Kroll with the assistance of a collective of authors for the higher education sector and appeared in its third edition in 1982. Rolf Fuchs was professor of education at the Humboldt University in Berlin and worked there with the Centre for Audio-Visual Teaching and Learning Resources (Zentrum für audiovisuelle Lehr- und Lernmittel, ZAL) founded in 1979.36 Klaus Kroll worked at the Institute for Technical Education of the GDR (Institut für Fachschulwesen der DDR) in Karl-Marx-Stadt.37 Hence, the publication can be understood as representing an official position on the field of vocational training and universities in the GDR.

In addition to the “information transfer function” and the “rationalisation function,” the “motivational function” of audio-visual media was also repeatedly emphasised:

The course of the learning process is co-determined by emotional colourings; pleasure or displeasure, interest or disinterest and other feelings accompany it. Frequently, and sometimes connected with this, a lessening of the learner’s attention also occurs in subjectively different learning phases. An av LLM [audiovisuelles Lehr- und Lernmittel, audio-visual teaching and learning aid] can, through appropriate design, stimulate the learning process insofar as it arouses involuntary attention, promotes a positive emotional state and keeps interest in the subject matter alive.38

In order to motivate this readiness, one strategy in particular can be found in the writings on the design of audio-visual teaching aids. On the basis of perception psychology, the principle of ‘association’ was discussed. Under this keyword, the linking of teaching content with visual and acoustic patterns, but also rational and emotional stimuli, was considered. In 1952, Albert Wilkening (1909–1990) spoke simply of “connections” that a director – he cites the Russian director and film theorist Sergei Eisenstein (1898–1948) as an example – creates with the help of film montage, aperture and vision and through which viewers also understand interrupted sequences of action. These connections function like conditional reflexes in Pavlov’s sense, Wilkening states. Thus, he emphasises, “It is not ‘illusion’, as it is mystically often called by dream makers, but a quite natural physiological process.”39 Wilkening was editor-in-chief of the journal Bild und Ton (Image and Sound), production manager at German Film AG (Deutsche Film AG, DEFA) and later professor at the German Academy for Cinematography (Deutsche Hochschule für Filmkunst) in Potsdam-Babelsberg.

Eisenstein was still relevant three decades later. Bernd Denecke systematically dealt with the coupling of knowledge and attitude from a pedagogical perspective under the already mentioned keyword “association complex” and, like Wilkening before him, referred to Eisenstein: “Eisenstein once wrote the following about the associative effect of the film image. The content of the image should be selected in such a way that, in addition to the visual illustration, an ‘associative complex’ is also created, which brings forth the emotional intellectual statement of the image.”40

In the IfBT information booklet Zur Gestaltung und Wirksamkeit von Bild und Ton dynamischer audiovisueller Lehr- und Lernmittel (On the Design and Effectiveness of Images and Sound in Dynamic Audio-Visual Teaching and Learning Aids), Denecke explained the design possibilities of the educational film in 1984.41 This booklet series was addressed to the academic field. Later, Denecke would submit these study results as his second dissertation at the Dresden University of Education, to get the permission to lecture at university in pedagogy (an equivalent to venia legendi). Before that, he had already received his doctorate in 1978 at the Humboldt University in Berlin with a dissertation on pre-produced television programmes and was subsequently involved in several perceptual-physiological studies on the theory of teaching and learning aids at the Magdeburg University of Education. In the 1984 booklet, he addressed not only camera settings and lighting conditions, but also the use of sound and especially music. He argues: “In the pedagogical design of audio-visual teaching and learning aids, we pursue the goal of consciously creating and triggering associations. In doing so, the learning contents are linked in such a way that the occurrence of one teaching content, e.g., the perception of a known chemical formula, leads to the reproduction of the ideas associated with the formula or produces a new concept, relationship or fact.”42

This refers to a phenomenon that fellow pedagogue Karl Steuding describes as ‘indirect influences’ in the case of an educational film on chemistry: “The film F 838 ‘Chemical Reaction I – the Combustion Process’ shows the combustion of charcoal or magnesium by pupils in a real shot at the beginning. The modern chemistry room, the clean and clear arrangement of the equipment and the observance of health and safety regulations all have an effect on the pupils in addition to the actual educational aim of these scenes.”43

After this brief, rather atmospheric description, Steuding quickly returns to the ‘direct influences’ and factual knowledge. But back to Denecke’s remarks on “attention,” which he sees as a “regulative variable of learning behaviour” that is influenced by associations and dependent on sensory stimuli: “Strong visual stimuli, caused, for example, by irregular arrangements of the picture, structured and articulated picture composition, colour contrasts, changes in movement, brightness fluctuations and much more, have a primarily involuntary effect and thus become unexpected stimuli that are useful for the visual absorption of information.”44

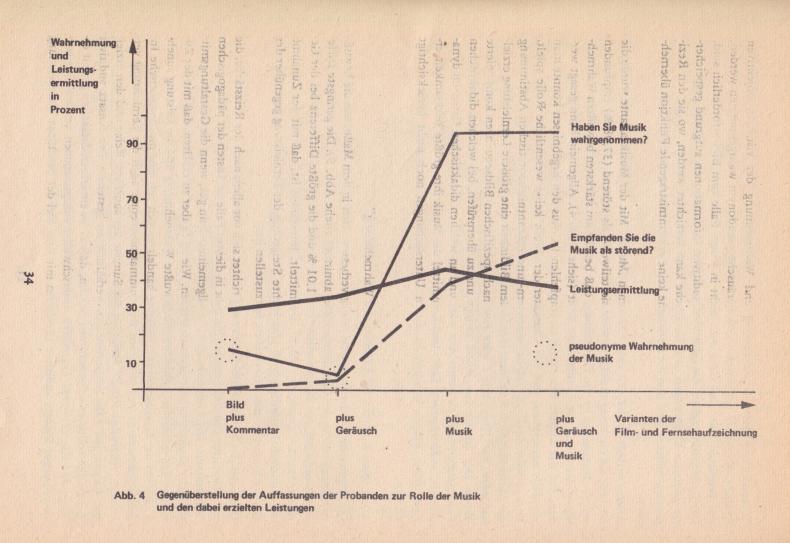

Denecke explains on the use of music in another publication that it is not only possible on the sound level to link disjointed visual material, but one can also specifically evoke physical reactions such as “increased breathing, higher pulse rate and body temperature as well as a perceptible rush of blood.”45 The impact study on which this is based was, however, remarkably not carried out via measurements or tests, but with a qualitative questionnaire evaluation. Denecke’s publications in the IfBT series came about as part of official resolutions to improve the pedagogical qualifications of university teachers in 1980.46 The background to his analyses and recommendations were studies at the Technical University of Magdeburg, in which 300 students were interviewed about four specially produced educational films (see Fig. 1).47

In the 1980s, information science approaches and the aim of effectiveness played a more important role, but in Denecke’s description ideas of conditioning, which had been discussed in the field of educational films especially around 1960, still shine through. In this sense, Ewald Topp also postulated in his already quoted dissertation on the basic technical equipment of the school: “The teaching and acquisition of knowledge and the training of skills must be inseparably linked to the formation of attitudes, ideological convictions and character traits. In all educational work, the unity of science and ideology must always be established.”48 The aim was always to convey factual content with the right, i.e., socialist, framing. In accordance with school policy, GDR teaching was therefore geared not only to imparting concrete bodies of knowledge and knowledge practices, but also to set the students’ attitudes towards them. The pedagogy of the GDR was convinced that affective and normative attributions shape the status and appreciation of learning content. A subject of learning should therefore not only be legitimised as true and useful to life, but also convey a certain affective attitude towards it. This was formulated concretely for the social science school subjects: “The pupils must feel emotionally attracted to the object of acquisition, so that they not only acquire specific discipline knowledge of the social sciences and knowledge of Marxism-Leninism intellectually, but are affected in their whole personality.”49 Thus, GDR pedagogy aimed to use the emotional attunement of students – not lastly through films – as a means to the end of imparting politically conformist knowledge.

4. Educational Films and the Dimension of Institutionalization of Instruction

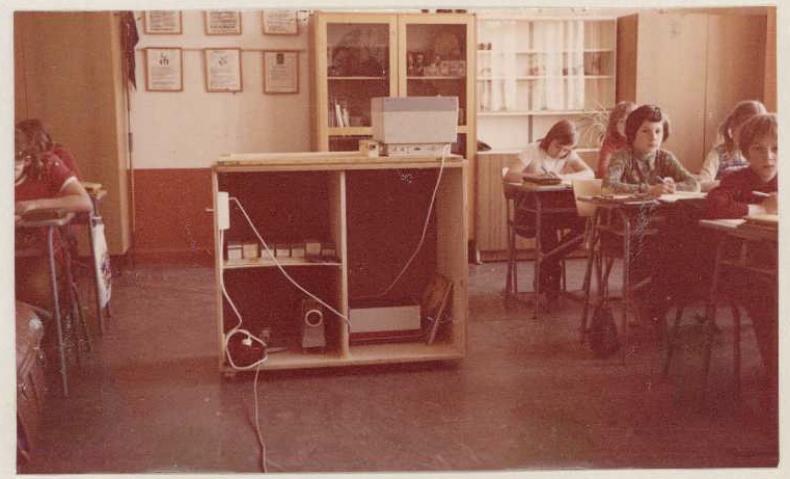

For the dimension of institutionalization of instruction, the place and time of teaching are relevant. Unlike textbooks, 16mm educational films did not generate a “spatio-temporal independence of learning.”50 The film projection relied on the blackout, a teacher operating the projector, and a teaching that prepared and followed up the film screening in the classroom. The photo (Fig. 2) gives an impression of how complex the set-up of the technical aids in the GDR classroom could be.51

However, the actors can also thwart the normative pattern of the grammar of schooling at certain points. The example of film in school shows this: For example, when an entertainment film is used as a teaching aid in language lessons, it then actually becomes a teaching film and is also understood by the pupils as a learning aid – then the film screening corresponds to the grammar of schooling. But the constellation is thwarted when an entertainment film is shown in the last hours before the holidays as a kind of relaxation and reward. Ultimately, however, this exception also supports the usual pattern, since the event is explicitly marked by the teacher as an exceptional situation and is perceived as such by the students. Basically, due to their relative shortness, films that are intended as educational films must be actively integrated into the lesson – i.e., by preparing, commenting, following up, etc. But when a 16mm film is started, the teacher has to leave the stage position in front of the class. He or she remains present in the classroom, the film apparatus rattles monotonously and radiates warmth, the images start flickering and (in case of a sound film) the sound starts, with the convinced voice of the general male commentator aiming to leave no room for doubt. The educational film could then elicit a variety of reactions: It could enchant immersively – if it uses the dramaturgical means of the entertainment or cultural film – or it could also make the students sleepy in its predictability and its even monotony.

In the GDR, educational film research operated in a field between planning, school practice and the produced teaching material. Initially – and this was also decisive for the first phase of educational film research in the GDR – the existing educational films were compared with regard to the curricular goals and the officially given scenarios for use in the classroom. This was later supplemented by studies on the use of teaching aids from the point of view of efficiency. Now school practice was evaluated or simulated in pedagogical experiments, and the results were taken into account in the planning of new teaching materials and teaching concepts.52 In these empirical studies, efficiency was interpreted as a testable degree of knowledge acquisition – on the other hand, the impact on learners’ (political) attitudes was hardly empirical addressed.

Within the framework of a lively research activity on the effectiveness of teaching-learning materials and teaching aids, several studies were carried out, i.e., lesson observations and questionnaire evaluations on both didactic use and learning success in schools and universities, the results of which found their way into dissertations. Considering the tendencies of self-censorship, it is somewhat surprising to frequently read sobering results, as in the case of studies on lending at district media centres,53 observations of lessons or surveys of teachers on the state of equipment and the degree of use. These findings could probably be applied to the entire Eastern Bloc: It was found that teachers did not effectively use the cost-intensive media.54 In accordance with the internal logic of the GDR educational system, the teachers’ lack of competence was diagnosed as the first cause of these problems. ‘Internal logic’ here refers to the reasoning that, since the teaching materials were created with the greatest care, taking into account current pedagogical and subject-specific expertise, they could only have been poorly applied – and this was up to the teachers. Moreover, in the planned economy of the GDR, the lack of equipment in schools was hardly discussed as a problem in public. These may have been the reasons of increased efforts in the teacher-training sector.55 However, it is noteworthy that handouts, booklets, etc., and training programmes for teachers have already been developed in parallel with the development of new curricula and teaching materials. Only very rarely, there were references to the fact that teachers did not use the teaching media because they saw them as outdated or unsuitable for other reasons. In the latter case, this could point us to the persistence of the grammar of schooling, as will be discussed below.

The above-mentioned Karl Steuding stated after a teacher survey on the chemistry film: Most teachers used films without preparation and follow-up, because they regard film as a teaching and learning tool that imparts extensive knowledge by merely showing it.56 Pedagogue Steuding worked with the Professor for Pedagogy Helmut Boeck and did research at the Central Office for the Rationalisation of Teacher Training and Further Education (Zentralstelle für Rationalisierungsmittel der Lehreraus- und -weiterbildung, ZRL) in Erfurt-Mühlhausen.57 However, this result did not correspond to the official intentions. On the contrary, Topp, as quoted at the beginning of this article, emphasised the leading role of the teacher in socialist pedagogy, which should not be compromised by technology. The technical equipment of the school was seen primarily as an instrument for planning, directing, imparting, appropriating and controlling.58 But one could also understand Topp’s plea as a concession to the grammar of schooling and teacher-centred teaching. And Steuding too, in describing his experimental set-up and the factors influencing the effectiveness of instructional films, stated the leading role of the teacher.59 He also used this claim to distinguish the socialist efforts from supposed ambitions in capitalist countries to compensate for teacher shortages through the use of instructional films.60 Therefore, one result of his experiments is not really surprising:

The attitude of the teacher towards the educational film is also extraordinarily important. In our investigations there were teachers who rejected a teaching film for this or that reason. In these cases, there was usually no special performance in the experimental examination in comparison to the control class, because those teachers either created extraordinarily intensive lessons in the control class or because certain methodological deficiencies were evident in the experimental class due to the rejection of the film. [...] The teacher very much determines the effectiveness of the film.61

Steuding – like the official interpretation – saw the only solution against the ineffective use of educational films in intensifying teacher training and further training. Steuding investigated the effectiveness of silent films, since the majority of films produced for chemistry lessons were made without sound and as fragmentary films – he also suggests that there were reservations about sound films on the part of teachers.62

He substantiates these reservations a few pages later by distinguishing between films according to their didactic character as “work tools” or as “demonstration tools.”63 He defines: “By the term ‘working material’ (or film with ‘working material character’) we want to understand such instructional films that only present the facts themselves without a deeper and more extensive explanation.”64 This is in line with the definition of a fragment film [Fragmentfilm], which, according to Fuchs and Kroll, always presupposes an embedding by the teacher: “The fragment film remains limited to one learning step or a short sequence of learning steps. The very term ‘fragment’ indicates that it is always only a direct part of a didactic-methodical unit.”65 Steuding defines the other type of film as follows: “By the term ‘demonstration medium’ (or film with the character of a ‘demonstration medium’) we want to understand those instructional films which deal comprehensively with a certain subject matter in accordance with the curriculum requirements.”66

In the further explanations it becomes clear that this corresponds to the so-called complex film [Komplexfilm] as defined by Fuchs and Kroll, which treats “a sequence of learning steps and leads from individual phenomena to generalising statements or from theoretical knowledge to examples of application in practice.”67 According to Steuding, films with the character of a working tool are generally preferable because they are easier to integrate into lessons and are more stimulating for the pupils.68

This assessment seems to be linked to a long tradition, for even at the time of the introduction of the educational film during the Weimar Republic, the pedagogical side preferred a certain aesthetic sparseness.69 The films were to be kept simple, frontal and soundless, so that the subject matter of the lesson never lost its focus and the teacher continued to play the central role as the film narrator.70 For the National Socialist era, matter-of-factness with pathos was cultivated and all too strong cinematic staging with a sophisticated sound dramaturgy, as was usual with propaganda films, was to be avoided.71 In the GDR – as in the FRG at the time – the film material of the Reich Institute for Film and Images in Science and the Classroom (Reichsanstalt für Film und Bild in Wissenschaft und Unterricht, RWU) continued to be used.72 But in the GRD an educational film type was produced with the so-called complex film, which made greater use of the filmic means of entertainment cinema in montage and sound. In this type of film, however, the mandate for attitude education became clearer; the knowledge content was emotionalised and ideologically embedded. Such films can also be found among Russian educational films and it is to be expected that this type of film was widespread throughout the Eastern Bloc. Remarkably, Western audiences are also familiar with educational films that are more cinematographically sophisticated, not to say entertaining, such as Disney’s educational productions.73 In the GDR, the complex films used the overwhelming strategies of cinema, but the studies on media practices indicate these films produced with great effort were rarely used, at least in science lessons – as Steuding’s analysis and other surveys suggest. It should be noted that delegations from the GDR regularly took part in international film festivals and the GDR was also present there with educational films.74 The involvement of GDR representatives in the International Scientific Film Association (ISFA) – which encompassed both Eastern and Western Bloc countries – is also worth mentioning.75 However, an overview of the scientific educational films produced in the GDR reveals that titles from other countries are very rarely listed in the teaching material catalogues.

The example of the film TF 1007 PRODUKTION VON ROHEISEN / PRODUCTION OF PIG IRON (DDR, 1977) shows how a so-called complex film worked. It was intended for chemistry classes in 7th grade of a Polytechnic Secondary School [Polytechnische Oberschule]. In this sound film, a lot happens on the visual level, a lot of movements in the pictures, a lot of cuts and setting changes. The principle of varying repetition creates an almost song-like impression with verses of the same structure and repeating choruses. The sound level uses original sounds to reinforce the documentary character of the film footage, but also an authorial male voice-over and even orchestral music. The plot can be read as a narration with a beginning and an end. The introduction refers to the importance of pig iron for transport and industry; in the first main part, the raw materials necessary for production are located on a map. In the second main part of the film, the chemical processes taking place are visualised and explained before the film builds up to the climax, the production of pig iron, the cinematic depiction of which finds an almost epic ending accompanied by the orchestral music. The cinematic staging of pig iron production shows the glowing metal for moments like the flowing lava of an erupting volcano (Fig. 4) accompanied by epic orchestral music. The film embeds the teaching content in atmospheric imagery and in this way conveys more than just facts – here it was much more about attitudes and convictions in an ideological understanding. Through montages, the film constantly mediates back and forth between map and real space or between schematic representation and industrial plant. This film is complex from a didactic point of view, as well. It kind of adapts the classroom lecture of a teacher who pauses and allows time to take notes before continuing. The film has auditory and visual pauses and uses repetitions as well as the commentary emphasises learning words through a special pronunciation. Here, the film is produced to claim the front position in a classroom and to gain the attention of all students.

But, as can be seen in Steuding’s description of the indirect influences of a chemistry film, this does not only go for complex films. In the educational films which were made as fragment or problem films and mostly without sound, importance was attached to conveying more than just the chemical formula, as well. The film on fermentation that Steuding investigated also uses documentary images from food production and agriculture, which can be read as narrative elements and thus also classify the chemical reaction in terms of its economic relevance. Although there were also very simple educational films in the GDR that referred purely to the learning knowledge to be imparted without any narrative elements, it is noticeable that in film production, importance was attached to presenting the why of what was learned.

In general, the GRD’s studies on the use of educational films had shown that, despite all the control fantasies and aims of heightened efficiency, the elaborately produced educational films were disappointing in their effectiveness. This is where the logic explained by Tröhler and Ölkers could come into play: Maybe, as Steuding’s analysis implies, the teachers especially objected to those educational films that were too out-of-school in their subject and style. Thus, a resistance caused by a grammar of schooling can also be assumed for the use of educational films in the GDR. The introduction of the terminus “Bewährung” (probation or proof, in the sense of ‘proven as useful’) in the studies on teaching aids can be understood as a reaction to such results. This concept was coined in the 1980s by the Academy of Pedagogical Studies (APW) of the GDR and focused on the practical suitability of audio-visual teaching aids in schools and, above all, on the person of the teacher as a judge in this matter.76 But the effectiveness of the audio-visual teaching aids was not only left to the activity of the teacher, but also to the students’ learning process: “The teacher shapes the lesson by actualising the potencies of this ‘conserve’ (the avUM) [die audiovisuellen Unterrichtsmittel, the audio-visual educational aids], bringing it to life and connecting it with the conditions of the current process [...] Audio-visual teaching aids are elements of creation in the hands of the teacher as well as in the hands of the learner.”77

Heinze also mentions this aspect, noting teachers or students must “activate” textbooks in the learning process through active usage.78 This indicates that a changed understanding of the learning process had prevailed in GDR’s educational research by the end of the 1980s that distanced itself from the idea of mere programming.79 Nevertheless, the 16mm film as a teaching aid, with its technical conditionality, always remained dependent on a projectionist; thus, the pupils could not independently use it as a learning aid. In the GRD, on the one hand, despite all the restrictive guidelines for classroom management, teachers also had a certain amount of freedom and could simply do without certain teaching aids. Officially, the intention to further optimise teacher training was maintained, as shown by the dissertation started in the GDR and submitted after reunification in 1990 on the introduction of an independent subject “Technik der Arbeit mit audiovisuellen Unterrichtsmitteln” (technique of working with audiovisual teaching aids) for prospective teachers.80

On the other hand, however, the studies on the use of the official lending services show that teachers were not even able to borrow the recommended films. Therefore, the classroom proved to be dominated by the teacher, who, in the view of the researchers, did not help the film achieve its intended effect. Thus, the central role of the teacher was manifested; and one could say the grammar of schooling had shown its powerfulness. These effects were taken into account by the academy for pedagogical studies and a new interest in the role of the teacher was awakened.

5. Résumé

In this article, the studies by Topp, Steuding and Denecke and the handbook by Fuchs and Kroll were the main sources. There were, on the one hand, more programmatic writings (Topp or Denecke) and, on the other, studies of a more verifying nature (Steuding). The latter were generally unpublished; Steuding’s analysis exists only as an archived manuscript in the library of the Humboldt University in Berlin. But these writings were all embedded in official pedagogical research in the GDR, i.e., they participated in state commissioned research. Moreover, Topp was aiming for a position in a state institution with his dissertation, Steuding for a professorship. In principle, therefore, (self-)censorship can be assumed. Accordingly, the studies always demonstrated political conformity in their design and interpretation of the results, but at the same time also followed the rules of scientific work. Steuding’s text engages with problems that he himself did not expect. But of course, his study can only provide pointers for school practice.

If one understands the use of teaching aids as linked to a certain teaching technology or teaching practice, then the trust in the use of audio-visual teaching materials on the part of the GDR’s school administration can not only be understood in terms of the universally emphasised increase in efficiency, but also as an attempt to at least temporarily undermine the instructional pattern of the standard teacher-centred teaching in order to increase the effectiveness of teaching. But, the enthusiasm for progress due to the new technical possibilities contrasted with the sobering results of studies on their usage in school practice. The case of GDR audio-visual teaching aids can be understood as an example of challenging the grammar of schooling and so, Caruso’s insistence on the complexity and associated ambivalences in educational reform processes can be confirmed. Although the power of regulation was very high in the case of the centralized GDR school system and the use of audio-visual teaching aids was propagated in teacher training and further education, teaching practice did not follow suit. However, the reasons for this were certainly not only the incompetence of the teachers, as was usually claimed in official publications, but also the partly insufficient technical equipment of the schools and the fact that film prints were not accessible for teachers, as GDR surveys showed, but also the fact that the teachers considered the time-consuming produced media unsuitable and therefore simply ignored them. All in all, it is hardly possible (or meaningful) to name clear-cut national distinctions of the GDR educational film. Differences to the educational films of the FRG at the time become relative in international comparison. Even the ideologically explicit type of “complex film” followed the Russian model and used cinematographic techniques that were also familiar to Western cinema. Nevertheless, according to the current state of knowledge, the theoretical discussions and reflections on the representational practices of the educational film in the GDR seem to have been comparatively elaborate.

In today’s classroom, the screen is almost a matter of course, darkening is hardly necessary and heat radiation and operating noise from technical equipment are also minimised. In addition, the accessibility of media content has become more flexible and de-hierarchized by digitalization and the accessibility in the World Wide Web. Thus, on the one hand, the teacher is no longer dependent on the material availability of a certain film format, such as 16mm, at his school or at a nearby rental point, but on the other hand, the students also can inform themselves independently, if they have the appropriate end devices. The technical and technological conditions of media use have thus changed fundamentally and film as teaching and learning resource is no longer dependent on the teacher as intermediary. So, with the changed relation between teacher and teaching/learning aid and new practices of knowledge acquisition, changing forms of teaching can also be assumed – and the grammar of schooling is challenged in all four dimensions here.

- 1This article is part of the project “The Myth of Scientific Neutrality. The Educational Film in Schools during the Cold War.” It is part of the research network “Bildungs-Mythen – eine Diktatur und ihr Nachleben. Bilder(welten) über Praktiken und Wirkungen in Bildung, Erziehung und Schule der DDR” funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) (https://bildungsmythen-ddr.de/ddr-forschung/).

- 2As an overview of media education in the GDR see: Arndt Fischer, Herbert Grunau, and Hartmut Warkus, “Medienpädagogische Bemühungen in der DDR. Ansprüche und Widersprüche – Aufbrüche und Abbrüche,” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Medienpädagogik und Kommunikationskultur 36 (1994): 79–93.

- 3Carsten Heinze, “Das Schulbuch zwischen Lehrplan und Unterrichtspraxis. Zur Einfuhrung in den Themenband,” in Das Schulbuch zwischen Lehrplan und Unterrichtspraxis, ed. Eva Matthes and Carsten Heinze (Bad Heilbrunn/Obb.: Klinkhardt, 2005), 9–17.

- 4Larry Cuban, “Persistence of the Inevitable. The Teacher-Centered Classroom,” Education and Urban Society 15 (1982): 26–41.

- 5Ewald Topp, Zur Funktion, Nutzung und Weiterentwicklung der technischen Grundausstattung der Oberschulen der DDR (Berlin: Volk und Wissen Verlag, 1973), 89.

- 6The biographical data of the GDR authors mentioned in the text are given where known.

- 7Dietmar Waterkamp, Lehrplanreform in der DDR. Die zehnklassige allgemeinbildende polytechnische Oberschule 1963–1972 (Hannover: Schroedel, 1975).

- 8Topp, Zur Funktion, Nutzung und Weiterentwicklung der technischen Grundausstattung der Oberschulen der DDR, 26.

- 9Nicole Zabel, “Die Lehrmaschine und der Programmierte Unterricht – Chancen und Grenzen im Bildungswesen der DDR in den 1960er und 1970er Jahren,” Jahrbuch für Historische Bildungsforschung 20 (2014): 123–152.

- 10Michael Annegarn-Gläß, Neue Bildmedien revisited. Zur Einführung des Lehrfilms in der Zwischenkriegszeit (Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt, 2020), 78–94.

- 11On educational film in the GDR see Karin Kneile-Klenk, Der Nationalsozialismus in Unterrichtsfilmen und Schulfernsehsendungen der DDR (Weinheim: Beltz, 2001); Uta Schwarz, “Vom Jahrmarktspektakel zum Aufklärungsinstrument. Gesundheitsfilme in Deutschland und der historische Filmbestand des Deutschen Hygiene-Museums Dresden,” in Kamera! Licht! Aktion! Filme über Körper und Gesundheit 1915 bis 1990, ed. Susanne Rößiger (Dresden: Sandstein, 2011), 12–49; Gerhard Knopfe, “Der populärwissenschaftliche Film der Defa,” in Schwarzweiß und Farbe. DEFA-Dokumentarfilme 1946–92, ed. Günter Jordan and Ralf Schenk (Berlin: Jovis, 1996), 294–341; Wiebke Degler et al., “Staging Nature in Twentieth-Century Teacher Education in Classrooms,” Paedagogica Historica 56 (2019): 121–149; Alexander Friedland, “‘... doch erscheint in seiner Denkschrift die Bedeutung des klinischen Films für den Unterricht allzustark betont.’ Zur Geschichte des Medizinisch kinematographischen Instituts der Charité 1923–1931,” Medizinhistorisches Journal 52, no. 2/3 (2017): 148–179.

- 12See Günter Schwarze et al., Technik der Arbeit mit audio-visuellen Unterrichtsmitteln (Berlin: Volk und Wissen, 1973), 9–21.

- 13See: Bernd Protzner, Das Problem der Lernmittelfreiheit. Der Einfluß staatlicher Instanzen auf didaktische Medien am Beispiel des Freistaats Bayern seit 1945 (Bad Heilbrunn/Obb.: Klinkhardt, 1977).

- 14On educational film in the FRG see: Anja Sattelmacher et al., “Introduction: Reusing Research Film and the Institute for Scientific Film,” Isis 112 (2021): 291–298.

- 15David Tyack and Larry Cuban, Tinkering toward Utopia. A Century of Public School Reform (Cambridge/Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995); David Tyack and William Tobin, “The ‘Grammar’ of Schooling: Why has It Been So Hard to Change?,” American Educational Research Journal 31 (1994): 453–479.

- 16Tyack and Tobin, “The ‘Grammar’ of Schooling,” 454.

- 17Daniel Tröhler and Jürgen Oelkers, “Historische Lehrmittelforschung und Steuerung des Schulsystems,” in Das Schulbuch zwischen Lehrplan und Unterrichtspraxis, ed. Eva Matthes and Carsten Heinze (Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt, 2005), 99.

- 18Carsten Heinze, “Historical Textbook Research. Textbooks in the Context of the ‘Grammar of Schooling,’” Journal of Educational Media, Memory & Society 2, no. 2 (2010): 122–131.

- 19Marcelo Caruso, “Technologiewandel auf dem Weg zur‘grammar of schooling.’ Reform des Volksschulunterrichts in Spanien (1767–1804),” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 56, no. 5 (2010): 648–665.

- 20Tröhler and Ölkers, Historische Lehrmittelforschung, 99.

- 21Heinze, Historical Textbook Research, 125.

- 22Ibid., 126.

- 23Ibid., 126.

- 24Ibid., 127.

- 25Ibid., 125.

- 26Andreas Tietze, Die theoretische Aneignung der Produktionsmittel. Gegenstand, Struktur und gesellschaftstheoretische Begründung der polytechnischen Bildung in der DDR (Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2012).

- 27Heinz-Elmar Tenorth et al., ed., Politisierung im Schulalltag der DDR: Durchsetzung und Scheitern einer Erziehungsambition (Weinheim: Deutscher Studien-Verlag, 1996).

- 28Heinze, Historical Textbook Research, 127.

- 29See introduction: Dietmar Waterkamp, Handbuch zum Bildungswesen der DDR (Berlin: Spitz, 1987); and Gert Geißler, Schule und Erziehung in der DDR (Erfurt: Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung Thüringen, 2015).

- 30Nicole Zabel, Zur Geschichte des Deutschen Pädagogischen Zentralinstituts der DDR (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Chemnitz, 2009), 124; Andreas Malycha, Die Akademie der Pädagogischen Wissenschaften der DDR 1970–1990 (Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsanstalt, 2009), 147; Sonja Häder and Ulrich Wiegmann, eds., Die Akademie der Pädagogischen Wissenschaften der DDR im Spannungsfeld von Wissenschaft und Politik (Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 2007).

- 31See: Helmut Boeck, Über die Eigenarten, die Aufgaben und die Gestaltung von Unterrichtsfilmen für den Chemieunterricht [...] (unpublished doctoral thesis, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 1962).

- 32See: Jürgen Küster, Untersuchungen zur Wirksamkeit von audio-visuellen Hochschulunterrichtsmitteln [...] (unpublished doctoral thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule “Dr. Theodor Neubauer” Erfurt/Mühlhausen, 1976).

- 33On pedagogical research in the GDR see: Heinz-Elmar Tenorth, “Die Erziehung ‘gebildeter Kommunisten’ als politische Aufgabe und theoretisches Problem. Erziehungsforschung in der DDR zwischen Theorie und Politik,” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 63 (2017): 207–275.

- 34Tröhler and Ölkers, Historische Lehrmittelforschung, 98–100.

- 35Rolf Fuchs and Klaus Kroll, Audiovisuelle Lehrmittel (Leipzig: Fotokinoverlag, 1982), 21.

- 36See: Hans-Georg Heun, “Die Organisation und Leitung der Arbeit mit audiovisuellen Lehr- und Lernmitteln an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin und an anderen Hochschulen in der DDR,” Neodidagmata 20 (1991): 131–136; and Rolf Fuchs, “Der hochschulmethodisch begründete Einsatz von Fernsehdokumentationen kommunikativer Realprozesse,” Neodidagmata 21 (1992), 125–130.

- 37Klaus Kroll, Erfahrungen und Probleme beim Einsatz des Lehrfernsehens für die Hoch- und Fachschulausbildung (Karl-Marx-Stadt: Institut für Fachschulwesen d. DDR, 1977).

- 38Fuchs and Kroll, Audiovisuelle Lehrmittel, 19.

- 39Albert Wilkening, “Pawlows bedingte Reflexe und der Film,” Bild und Ton 5, no. 3 (1952): 65.

- 40Bernd Denecke, Zur Gestaltung und Wirksamkeit von Bild und Ton dynamischer audiovisueller Lehr- und Lernmittel (Berlin: ifbt, 1984), 10.

- 41Denecke submitted a dissertation entitled “Pädagogisch-psychologische Grundlagen der Bild/Ton-Gestaltung audiovisueller Lehr- und Studiermittel” (unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Dresden, 1986). Central text segments had already appeared in 1984 in Denecke, Zur Gestaltung, 1984.

- 42Denecke, Zur Gestaltung, 10.

- 43Karl Steuding, Untersuchung zur Bestimmung der pädagogisch-methodischen Wirksamkeit von Unterrichtsfilmen im Unterrichtsprozeß des Faches Chemie der Zehnklassigen Allgemeinbildenden Polytechnischen Oberschule (unpublished doctoral thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule “Theodor Neubauer” Erfurt/Mühlhausen, 1972), 28.

- 44Denecke, Zur Gestaltung, 11.

- 45Ibid., 84.

- 46Ibid., 5.

- 47Ibid., 30.

- 48Topp, Zur Funktion, 20.

- 49Gisela Wörner, Audiovisuelle Unterrichtsmittel und erziehungswirksamer Unterricht (Berlin: Volk und Wissen, 1979), 43.

- 50Heinze, Historical Textbook Research, 126.

- 51The photo was element of a text written by a GDR school headmaster probably in 1977: Harald Krieger, Probleme und Erfahrungen beim Aufbau des Fachunterrichtsraumsystems an der POS Schulzendorf im Kreis Königs Wusterhausen aus der Sicht der Leitung der Schule (BBF/DIPF, PL 4605a). On this GDR type of pedagogical writings see: Josefine Wähler and Maria-Annabel Hanke, “‘Pacemakers Report’: GDR Pedagogical Innovators and the Collection of Pädagogische Lesungen, 1952–1989,” Paedagogica Historica 58 (2020), DOI: 10.1080/00309230.2020.1796720.

- 52Horst Rasche, Zur Analyse und Durchführung von Praxisanalysen – Standpunkte, Erfahrungen, Empfehlungen (Berlin: Humboldt Universität, 1981).

- 53See: Günter Heichel, Analyse des Ausstattungsstandes, des Ausnutzungsgrades, des methodischen Einsatzes von Unterrichtsmitteln und der erzieherischen Einflußnahme bei der Arbeit mit Unterrichtsmitteln im Biologieunterricht der allgemeinbildenden polytechnischen Oberschulen der DDR (unpublished doctoral thesis, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 1975).

- 54Arndt Fischer, Herbert Grunau, and Hartmut Warkus, “Medienpädagogische Bemühungen in der DDR. Ansprüche und Widersprüche – Aufbrüche und Abbrüche,” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Medienpädagogik und Kommunikationskultur 36 (1994): 79–93, 9.

- 55Josefine Wähler and Sabine Reh, “Das Zentralinstitut für Weiterbildung der DDR 1962 bis 1990/1991,” in Erziehen und Bilden. Der Bildungsstandort Struveshof 1917–2017, ed. Landesinstitut für Schule und Medien Berlin-Brandenburg (LISUM) (Ludwigsfelde-Struveshof: Landesinstitut für Schule und Medien Berlin-Brandenburg, 2017), 131–166.

- 56Steuding, Untersuchung, 11.

- 57Boeck himself received his doctorate from the University of Halle-Wittenberg in 1962 with a dissertation on educational chemistry films. He defined the educational film as follows: “An educational film is a teaching and learning aid designed according to pedagogical-methodical aspects, the content of which is determined by the teaching tasks and which is suitable by its characteristics to effectively support certain areas of the educational process in class.” (Boeck, Über die Eigenarten, 37.)

- 58Topp, Zur Funktion, 13.

- 59Steuding, Untersuchung, 51.

- 60Ibid., 32.

- 61Ibid., 154.

- 62Ibid., 16.

- 63Ibid., 28–36.

- 64Ibid., 29.

- 65Fuchs and Kroll, Audiovisuelle Lehrmittel, 81.

- 66Steuding, Untersuchung, 29.

- 67Fuchs and Kroll, Audiovisuelle Lehrmittel, 81.

- 68Steuding, Untersuchung, 30.

- 69Yasuo Imai, “Ding und Medium in der Filmpädagogik unter dem Nationalsozialismus,” Zeitschrift fur Erziehungswissenschaft 25 (2015): 229–251; and Verena Niethammer, “Indoktrination oder Innovation? Der Unterrichtsfilm als neues Lehrmedium im Nationalsozialismus,” Journal of Educational Media, Memory & Society 8, no. 1 (2016): 30–60.

- 70Annegarn-Gläß, Neue Bildmedien, 89–94; and see: Yasuo Imai, “Film und Pädagogik in Deutschland 1912–1915. Eine Analyse der Zeitschrift Bild und Film,” Bildung und Erziehung 47, no. 1 (1994): 87–106.

- 71Konstantin Mitgutsch, “Indoktrination als Phantom. Über die Intentionalität des Medieneinsatzes im Lehr-Lernprozess,” in Indoktrination und Erziehung, ed. Henning Schluß (Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2007), 93–112.

- 72Imai, Ding und Medium, 231.

- 73Ina Heumann and Julia Köhne, “Imagination einer Freundschaft – Disneys Our Friend the Atom. Bomben, Geister und Atome 1957,” Zeitgeschichte 35, no. 6 (2008): 372–395.

- 74See the travel reports in the files of the Academy of Educational Sciences of the GDR (Akademie der Pädagogischen Wissenschaften der DDR). Now, the files are located in the archive of the Research Library for the History of Education (Bibliothek für Bildungsgeschichtliche Forschung) in Berlin.

- 75Werner Hortzschansky, the first head of the Central Institute for Film and Images in Science and the Classroom (Zentralinstitut für Film und Bild in Unterricht und Wissenschaft). He was elected 1st Vice President of the Standing Committee on Higher Instructional Film in 1958 at the XII. Congress of the International Scientific Film Association (ISFA) in Moscow, see Kneile-Klenk, Der Nationalsozialismus in Unterrichtsfilmen, 56–57.

- 76Karl Steuding, Zur Bewährung audiovisueller Hochschulunterrichtsmittel im Hinblick auf die Zielstellung der Ausbildungsdokumente in der Diplomlehrerausbildung der DDR (unpublished doctoral thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule “Dr. Theodor Neubauer” Erfurt/Mühlhausen, 1988), 6.

- 77Holger Donle, Die koordinierte pädagogische Führungstätigkeit zur Ausbildung der Lehrerstudenten im Lehrgebiet “Technik der Arbeit mit audiovisuellen Unterrichtsmitteln” an der kombinierten Lehrerbildungseinrichtung unter Berücksichtigung der Erfahrungen an der Pädagogischen Hochschule Neubrandenburg (unpublished doctoral thesis, unpublished doctoral thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule “Dr. Theodor Neubauer” Erfurt/Mühlhausen, 1990), 25.

- 78Heinze, Historical Textbook Research, 126.

- 79Zabel, “Die Lehrmaschine und der Programmierte Unterricht,” 149.

- 80See: Donle, Die koordinierte pädagogische Führungstätigkeit.

Annegarn-Gläß, Michael. Neue Bildmedien revisited. Zur Einführung des Lehrfilms in der Zwischenkriegszeit. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt, 2020.

Blömeke, Sigrid, Christiane Müller, and Dana Eichler. “Handlungsmuster von Lehrerinnen und Lehrern beim Einsatz neuer Medien. Grundlagen eines Projekts zur empirischen Unterrichtsforschung.” MedienPädagogik: Zeitschrift für Theorie und Praxis der Medienbildung 4 (2017): 229–244.

Boeck, Helmut. Über die Eigenarten, die Aufgaben und die Gestaltung von Unterrichtsfilmen für den Chemieunterricht [...]. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 1962.

Caruso, Marcelo. “Technologiewandel auf dem Weg zur "grammar of schooling". Reform des Volksschulunterrichts in Spanien (1767–1804).” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 56, no. 5 (2010): 648–665.

Cuban, Larry. “Persistence of the Inevitable. The Teacher-Centered Classroom.” Education and Urban Society 15 (1982): 26–41.

Degler, Wiebke et al. “Staging Nature in Twentieth-Century Teacher Education in Classrooms.” Paedagogica Historica 56 (2019): 121–149.

Denecke, Bernd. Zur Gestaltung und Wirksamkeit von Bild und Ton dynamischer audiovisueller Lehr- und Lernmittel. Berlin: ifbt, 1984.

Denecke, Bernd. Pädagogisch-psychologische Grundlagen der Bild/Ton-Gestaltung audiovisueller Lehr- und Studiermittel. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Dresden, 1986.

Donle, Holger. Die koordinierte pädagogische Führungstätigkeit zur Ausbildung der Lehrerstudenten im Lehrgebiet “Technik der Arbeit mit audiovisuellen Unterrichtsmitteln” an der kombinierten Lehrerbildungseinrichtung unter Berücksichtigung der Erfahrungen an der Pädagogischen Hochschule Neubrandenburg. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule “Dr. Theodor Neubauer,” Erfurt/Mühlhausen, 1990.

Fischer, Arndt, Herbert Grunau, and Hartmut Warkus. “Medienpädagogische Bemühungen in der DDR. Ansprüche und Widersprüche – Aufbrüche und Abbrüche.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Medienpädagogik und Kommunikationskultur, 36 (1994): 79–93.

Friedland, Alexander. “‘... doch erscheint in seiner Denkschrift die Bedeutung des klinischen Films für den Unterricht allzustark betont.’ Zur Geschichte des Medizinisch-kinematographischen Instituts der Charité 1923–1931.” Medizinhistorisches Journal 52, no. 2/3 (2017): 148–179.

Fuchs, Rolf and Klaus Kroll. Audiovisuelle Lehrmittel. Leipzig: Fotokinoverlag, 1982.

Fuchs, Rolf. “Der hochschulmethodisch begründete Einsatz von Fernsehdokumentationen kommunikativer Realprozesse.” Neodidagmata 21 (1992): 125–130.

Geißler, Gert. Schule und Erziehung in der DDR. Erfurt: Landeszentrale für Politische Bildung Thüringen, 2015.

Gysbers, Andre. Lehrer, Medien, Kompetenz. Eine empirische Untersuchung zur medienpädagogischen Kompetenz und Performanz niedersächsischer Lehrkräfte. Berlin: Vistas, 2008.

Häder, Sonja and Ulrich Wiegmann, eds. Die Akademie der Pädagogischen Wissenschaften der DDR im Spannungsfeld von Wissenschaft und Politik. Frankfurt am Main: Lang, 2007.

Heichel, Günter. Analyse des Ausstattungsstandes, des Ausnutzungsgrades, des methodischen Einsatzes von Unterrichtsmitteln und der erzieherischen Einflußnahme bei der Arbeit mit Unterrichtsmitteln im Biologieunterricht der allgemeinbildenden polytechnischen Oberschulen der DDR. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, 1975.

Heinze, Carsten. “Das Schulbuch zwischen Lehrplan und Unterrichtspraxis. Zur Einführung in den Themenband.” In Das Schulbuch zwischen Lehrplan und Unterrichtspraxis, edited by Eva Matthes and Carsten Heinze, 9–17. Bad Heilbrunn/Obb.: Klinkhardt, 2005.

Heinze, Carsten. “Historical Textbook Research. Textbooks in the Context of the "Grammar of Schooling."” Journal of Educational Media, Memory & Society 2, no. 2 (2010): 122–131.

Heumann, Ina and Julia Köhne. “Imagination einer Freundschaft – Disneys Our Friend the Atom. Bomben, Geister und Atome 1957.” Zeitgeschichte 35, no. 6 (2008): 372–395.

Heun, Hans-Georg. “Die Organisation und Leitung der Arbeit mit audiovisuellen Lehr- und Lernmitteln an der Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin und an anderen Hochschulen in der DDR.” Neodidagmata 20 (1991): 131–136.

Imai, Yasuo. “Ding und Medium in der Filmpädagogik unter dem Nationalsozialismus.” Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft 25 (2015): 229–251.

Imai, Yasuo. “Film und Pädagogik in Deutschland 1912-1915. Eine Analyse der Zeitschrift Bild und Film.” Bildung und Erziehung 47, no. 1 (1994): 87–106.

Kneile-Klenk, Karin. Der Nationalsozialismus in Unterrichtsfilmen und Schulfernsehsendungen der DDR. Weinheim: Beltz, 2001.

Knopfe, Gerhard. “Der populärwissenschaftliche Film der Defa.” In In Schwarzweiß und Farbe. DEFA-Dokumentarfilme 1946–92, edited by Günter Jordan and Ralf Schenk, 294–341. Berlin: Jovis, 1996.

Krieger, Harald. Probleme und Erfahrungen beim Aufbau des Fachunterrichtsraumsystems an der POS Schulzendorf im Kreis Königs Wusterhausen aus der Sicht der Leitung der Schule. BBF/DIPF, PL 4605a.

Kroll, Klaus. Erfahrungen und Probleme beim Einsatz des Lehrfernsehens für die Hoch- und Fachschulausbildung. Karl-Marx-Stadt: Inst. für Fachschulwesen d. DDR, 1977.

Küster, Jürgen. Untersuchungen zur Wirksamkeit von audio-visuellen Hochschulunterrichtsmitteln [...]. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule „Dr. Theodor Neubauer“ Erfurt/Mühlhausen, 1976.

Malycha, Andreas. Die Akademie der Pädagogischen Wissenschaften der DDR 1970–1990. Leipzig: Akademische Verlagsanstalt, 2009.

Mitgutsch, Konstantin. “Indoktrination als Phantom. Über die Intentionalität des Medieneinsatzes im Lehr-Lernprozess.” In Indoktrination und Erziehung, edited by Henning Schluß, 93–112. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 2007.

Niethammer, Verena. “Indoktrination oder Innovation? Der Unterrichtsfilm als neues Lehrmedium im Nationalsozialismus.” Journal of Educational Media, Memory & Society 8, no. 1 (2016): 30–60.

Protzner, Bernd. Das Problem der Lernmittelfreiheit. Der Einfluß staatlicher Instanzen auf didaktische Medien am Beispiel des Freistaats Bayern seit 1945. Bad Heilbrunn/Obb.: Klinkhardt, 1977.

Rasche, Horst. Zur Analyse und Durchführung von Praxisanalysen – Standpunkte, Erfahrungen, Empfehlungen. Berlin: Humboldt Universität, 1981.

Sattelmacher, Anja et al. “Introduction: Reusing Research Film and the Institute for Scientific Film.” Isis 112 (2021): 291–298.

Schwarz, Uta. “Vom Jahrmarktspektakel zum Aufklärungsinstrument. Gesundheitsfilme in Deutschland und der historische Filmbestand des Deutschen Hygiene-Museums Dresden.” In Kamera! Licht! Aktion! Filme über Körper und Gesundheit 1915 bis 1990, edited by Susanne Rößiger, 12–49. Dresden: Sandstein, 2011.

Schwarze, Günter. Technik der Arbeit mit audio-visuellen Unterrichtsmitteln. Berlin: Volk und Wissen, 1973.

Steuding, Karl. Untersuchung zur Bestimmung der pädagogisch-methodischen Wirksamkeit von Unterrichtsfilmen im Unterrichtsprozeß des Faches Chemie der Zehnklassigen Allgemeinbildenden Polytechnischen Oberschule. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule “Theodor Neubauer” Erfurt/Mühlhausen, 1972.

Steuding, Karl. Zur Bewährung audiovisueller Hochschulunterrichtsmittel im Hinblick auf die Zielstellung der Ausbildungsdokumente in der Diplomlehrerausbildung der DDR. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Pädagogische Hochschule „Dr. Theodor Neubauer“ Erfurt/Mühlhausen, 1988.

Tenorth, Heinz-Elmar et al., eds. Politisierung im Schulalltag der DDR: Durchsetzung und Scheitern einer Erziehungsambition. Weinheim: Deutscher Studien-Verlag, 1996.

Tenorth, Heinz-Elmar. “Die „Erziehung gebildeter Kommunisten“ als politische Aufgabe und theoretisches Problem. Erziehungsforschung in der DDR zwischen Theorie und Politik.” Zeitschrift für Pädagogik 63 (2017): 207–275.

Tietze, Andreas. Die theoretische Aneignung der Produktionsmittel. Gegenstand, Struktur und gesellschaftstheoretische Begründung der polytechnischen Bildung in der DDR. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2012.

Topp, Ewald. Zur Funktion, Nutzung und Weiterentwicklung der technischen Grundausstattung der Oberschulen der DDR. Berlin: Volk und Wissen Verlag, 1973.

Tröhler, Daniel and Jürgen Oelkers. “Historische Lehrmittelforschung und Steuerung des Schulsystems.” In Das Schulbuch zwischen Lehrplan und Unterrichtspraxis, edited by Eva Matthes and Carsten Heinze, 95–107. Bad Heilbrunn: Klinkhardt, 2005).

Tyack, David and William Tobin. “The ‘Grammar’ of Schooling: Why has It Been So Hard to Change?” American Educational Research Journal 31 (1994): 453–479.

Tyack, David and Larry Cuban. Tinkering toward Utopia. A Century of Public School Reform. Cambridge/Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995.

Wähler, Josefine and Sabine Reh. “Das Zentralinstitut für Weiterbildung der DDR 1962 bis 1990/1991.” In Erziehen und Bilden. Der Bildungsstandort Struveshof 1917–2017, edited by Landesinstitut für Schule und Medien Berlin-Brandenburg (LISUM), 131–166. Ludwigsfelde-Struveshof: Landesinstitut für Schule und Medien Berlin-Brandenburg, 2017.

Wähler, Josefine and Maria-Annabel Hanke. “’Pacemakers Report’: GDR Pedagogical Innovators and the Collection of Pädagogische Lesungen, 1952–1989.” Paedagogica Historica 58 (2020). DOI: 10.1080/00309230.2020.1796720.

Waterkamp, Dietmar. Lehrplanreform in der DDR. Die zehnklassige allgemeinbildende polytechnische Oberschule 1963–1972. Hannover: Schroedel, 1975.

Waterkamp, Dietmar. Handbuch zum Bildungswesen der DDR. Berlin: Spitz, 1987.

Wilkening, Albert. “Pawlows bedingte Reflexe und der Film.” Bild und Ton 5, no. 3 (1952): 65.

Wörner, Gisela. Audiovisuelle Unterrichtsmittel und erziehungswirksamer Unterricht. Berlin: Volk und Wissen, 1979.

Zabel, Nicole. Zur Geschichte des Deutschen Pädagogischen Zentralinstituts der DDR. Unpublished doctoral thesis, University of Chemnitz, 2009.

Zabel, Nicole. “Die Lehrmaschine und der Programmierte Unterricht – Chancen und Grenzen im Bildungswesen der DDR in den 1960er und 1970er Jahren.” Jahrbuch für Historische Bildungsforschung 20 (2014): 123–152.