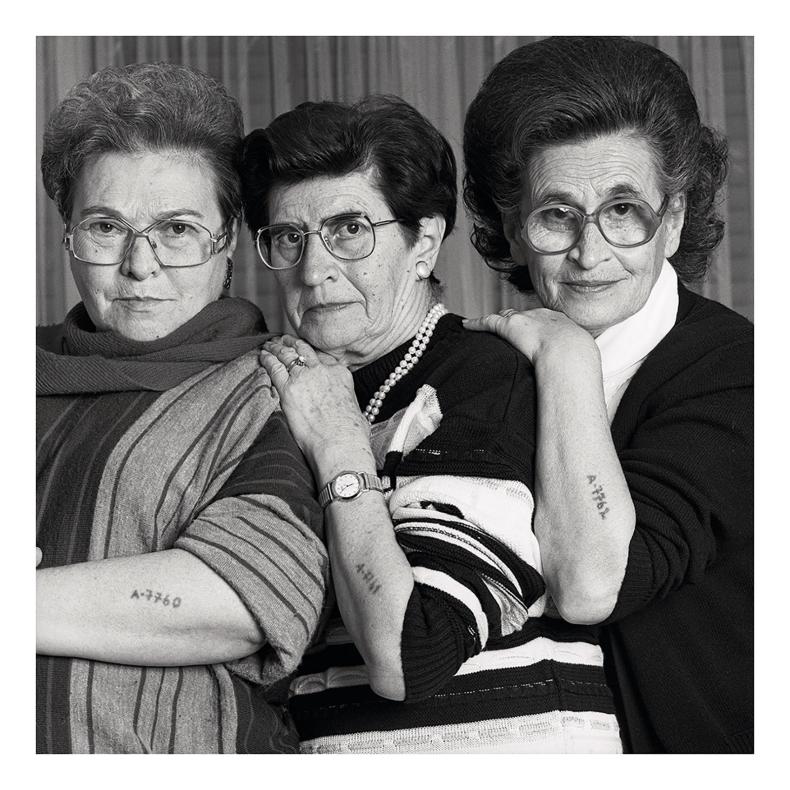

Three sisters

Vardi Kahana, Three sisters (Tel Aviv), 1992. My mother, Rivka Kahana, with her two sisters, Leah and Esther, consecutive numbers on their forearms. In this order they lined up and were tattooed in Auschwitz. Courtesy of the artist

As the title of this piece implies, the three elderly women are the artist’s mother, Rivka, and her two sisters, Leah and Esther. Leaning toward each other, the three sisters present the identification numbers tattooed on their left forearms: A7760, A7761, and A7762. The numbers tattooed on their forearms suggests that this is not a portrait in the conventional sense of the word. The women’s penetrating gaze at the camera is an invitation for viewers to join them on a journey. This is the journey of one Jewish family of three girls, as much as it is the Israeli story. Indeed, Three sisters is the departure point for a photo series entitled One Family: a series created over the course of a decade, during which the artist documented her family members, descendants of the three sisters. The result is a human mosaic of Israeli society: Kibbutzniks, settlers, and city dwellers of all ages and genders. The series continues where the historical footage left off: the close-up shot of the girl and the tattoo on her forearm has become a distinguished family tree.

However, another possibility lurks below the surface, one that in many ways undermines the Zionist narrative, especially its myth of the ‘New Jew.’ Like the Soviet cameraman, Vardi Kahana focuses on the figure of the diasporic Holocaust victim, the figure that Zionism rejected. Kahana succeeds in reclaiming this figure, presenting three powerful women (four if we include the artist), mothers who, against all odds, established a glorious, four-generation maternal dynasty. From this point of view, the number on their arms is no longer the symbol of a victim but a demonstration of female solidarity: three sisters, one sisterhood.