Issue 7: Iconic Film Footage from the Nazi Era

Iconic Film Footage from the Nazi Era: Context and Circulation

In recent years, both film studies and contemporary history including memory studies have increasingly recognized that films are not only sources of history, but are also instrumental in shaping our idea of the past. 1 However, research of historical films that reflects on the films themselves as well as on archival sources for the reconstruction and contextualization of their production and of their impact on memory culture is still a desideratum, especially with regard to the cinematic legacy of National Socialism.

While photographic sources have been discussed intensively and methods of historical image analysis have been extensively theorized, especially from the perspective known as “visual history,” there is still a lot of potential with regard to cinematic sources of National Socialism. This is despite the general assumption that many of these films or materials are familiar and well known. Over the years, many of the National Socialist self-images as well as the images the regime produced of others have started to migrate through popular culture almost independently. Widely circulated and often cited these film images and sequences, some of which have become visual icons of public memory, often obscure the specific contexts of their creation and blur the ideological perspectives inscribed in them. They acquire an illustrative status, and the knowledge of who made them in what circumstances and in how many versions, who was depicted in them, often under duress, and what happened to the footage since then, is lost if it ever existed. Despite some important case studies, such a material history has yet to be written for many films and film fragments from the Nazi era. This is the starting point for the essays in our special issue.

At the same time, however, most of the eight contributions also consider the later migration of the images and sounds into other films and TV shows, both documentary as well as fictional formats, thus broadening the perspective on the cinematic legacy of National Socialism to include the commemorative function of media. The historical film materials serve as sources (source films) for subsequent cinematic representations of the Holocaust and National Socialism, and sometimes also completely different topics (carrier films), which thus carry them forward, sometimes modify them, relate them to other materials, and reexamine their origin and status. How such re-uses as well as the transformation of national and transnational cultures of (audiovisual) remembrance in turn influence changing perceptions and understandings of the past is also the subject of some of the contributions collected here.

This special issue is an interim result of the long-term research project “(Con)sequential Images. An archaeology of iconic film footage from the Nazi era” funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG), which was launched in May 2021 as a cooperation between the Film University Babelsberg and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “Archaeology” in the project title naturally ties in with the various trends in film and media archaeology of the last 25 years, and in our case is referring to a very practice-oriented, concrete way of film research, since the starting point for our exploration is the subsequent use of historical film footage originating from the Nazi era, which we address from different perspectives: in form of a material history, a visual analysis and a history of appropriation.

Concerning the first approach, it is not always easy or possible to determine what can be considered “the original:” Some of our source films turned out to be composed of completely different sources, others exist in different versions, of which it is not necessarily clear which one comes closest to the filmmakers’ intentions. It is also important to clarify, by some sort of detective work, how and through which channels they were handed down to us, and in which period they were available to whom. This is crucial for answering the question of why certain materials (individual shots, scenes and sequences) were or were not used in particular countries or situations.

The second approach involves examining the film footage with various digital tools more closely than has been done or has been possible in the past. It is always astonishing how little knowledge is ultimately available, even among experts, about film images that have traveled around the world. This concerns the question of authorship and ownership, the exact location of the places where filming took place, the estimation of the date and time of filming, the identity of the people seen in the film and much more.

The third approach links the origin of the footage to its circulation in the present. Referring to Jamie Baron, 2 we call it the history of appropriation. Our aim is to explore exactly how the migration of individual shots from the source films through international film and television history functioned, which motives and which actors were involved and how the status of the individual films changed in the public perception as a result of continuous recontextualization.

In order to work with a set of data as broad as possible, we identified on the basis of titles or descriptions around 8,500 carrier films, in which we suspected shots from the source films we were investigating; of these, we were able to obtain approx. 4,500 films digitally and viewed them in fast-forward mode in order to track down the shots we were looking for; the findings were then tagged according to various criteria, stored and linked with accurate timecode information using the software “Icon Maker”, which we specifically developed for this purpose. Thus, the selection of films was based on accessibility and probability and is therefore not all-encompassing, but promises a valid approximation, at least as far as Europe, Israel and North America are concerned (and in particular documentaries and essay films on the Nazis and the Holocaust), while television could only be partially taken into account.

Our project is dating back at least to 2016. The first materials we looked at included Leni Riefenstahl's TRIUMPH DES WILLENS (1935) and a private film depicting an execution site in Liepaja, Latvia, the so-called Wiener film (1941). It was only over the years, based on viewing experience, that we decided on 23 core materials (amateur films and home movies, films commissioned by Nazi officials, newsreels, Allied documentaries and long propaganda films) that we consider “iconic” in the context of a migration history of Nazi footage. This term has religious origins, but today it is not only ubiquitous in reportage photography and in the art-historical study of popular culture, but also in everyday language. In fact, it is used so frequently that it has almost lost its meaning. In this respect, using the term “iconic” in the project title was a provocation – not necessarily for our funders, but for ourselves in the sense of a challenge to reconsider the meaning of “iconic” for each individual material, and even whether the term is ultimately unsuitable.

In our project, we also explore the potential of videographic essays, mainly by using them both as research tool and to process and visualize results, but increasingly also in the course of developing formats for educational work. Some of our experiments are included in the essays of this special issue. You can follow our activities on the project website.

Each essay presents preliminary results of our research on one of the 23 core materials. We present them in the chronological order of the production date of the source film discussed in the respective essay. However, some of the materials, such as the sequences depicting the anti-Jewish boycott in April 1933, became iconic only as composites of several sources, which were compiled at different times in different contexts. Others, like the private films of Eva Braun (1938–1944) and Reinhard Wiener but also the archived film footage from the Warsaw Ghetto (1942) or the Westerbork film (1944), were publicly shown only after 1945 as part of post-war documentaries. One of the films discussed in this special issue, the notorious propaganda film DER EWIGE JUDE (1940), is itself composed of different source materials next to original sequences specifically made for the film.

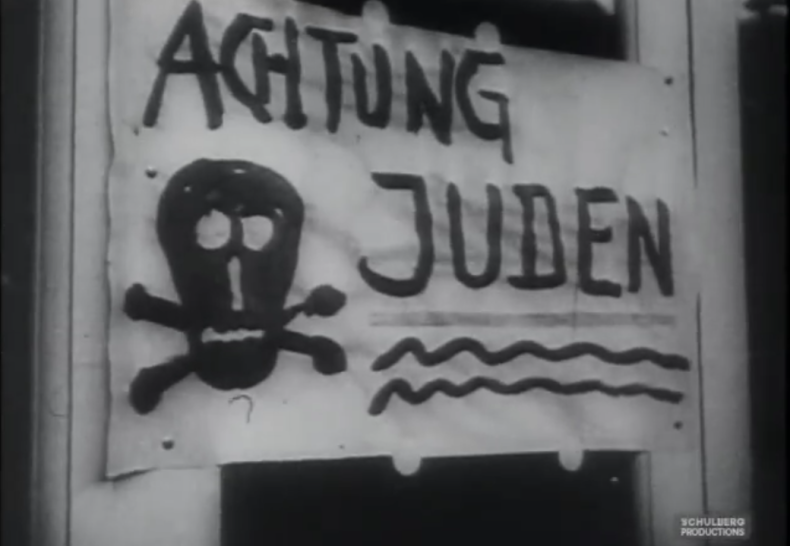

In her article, Noga Stiassny critically examines the April 1st Anti-Jewish Boycott newsreel footage. The starting point of her journey is a version edited into the US-American compilation film THE NAZI PLAN (1945). She subsequently uncovers several ‘originals’ and shows that the iconic boycott images do not represent the Nazi regime’s self-image, but are rather a curated compilation of newsreel footage originally produced by the American newsreel companies Fox and Paramount.

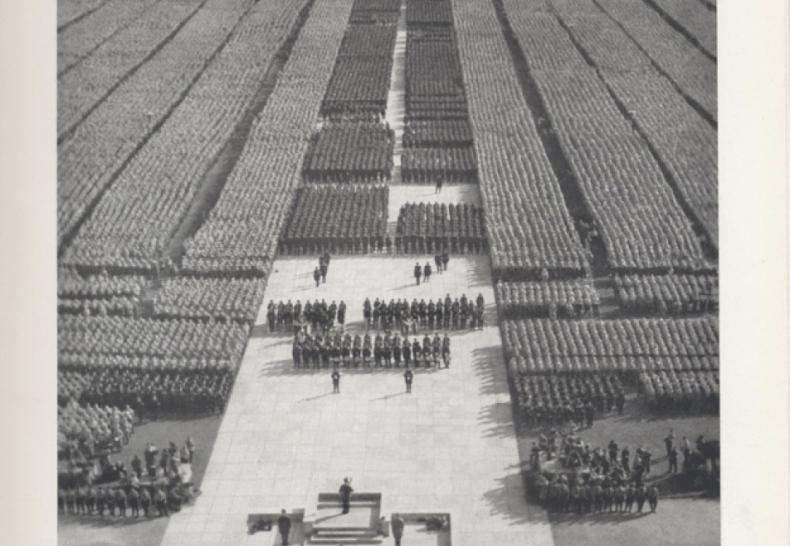

Chris Wahl discusses the longest as well as the most famous and, in various respects, the most ‘successful’ source film in our corpus. He focuses on the material history of Riefenstahl's propaganda flic TRIUMPH DES WILLENS, and here in particular on the controversy about the sequences of Reichswehr and Stahlhelm, on the abridged US versions from the 1940s, and on the versions from the 1970s connected with copyright issues. The question of documentary versus propaganda film is also revisited, historicized, and turned into the negative: What did Riefenstahl actually not make or film? In order to tackle the “iconic,” Wahl adopts both an inner-filmic and a meta-filmic perspective, and takes also photographs by Heinrich Hoffmann into consideration. In a final twist, the migration of images from TRIUMPH DES WILLENS to other productions is reversed, under the keywords “tradition” and “zeitgeist”, into a videographic examination of Riefenstahl's own film aesthetical role models.

The so-called Bloody Sunday in Bydgoszcz (in German: Bromberg) in September 1939 remains a controversial subject between Poland and Germany until today. An event of mass-violence between the Volksdeutsche minority and ethnic Poles living in the city, it was immediately exploited by the Nazi propaganda apparatus which squarely placed the blame on the Poles, using it to justify reprisals but also the Nazis' genocidal policy enacted on Polish territory at large. The event and its aftermath have left disparate traces in Poland, Germany, as well as Israel, with the Jewish community of Bydgoszcz having been annihilated. Yael Ben-Moshe and Alexander Zöller examine the historical context of the events and its ongoing transnational ramifications, and explore how the propagandistic depiction in German wartime newsreel footage continues to be appropriated.

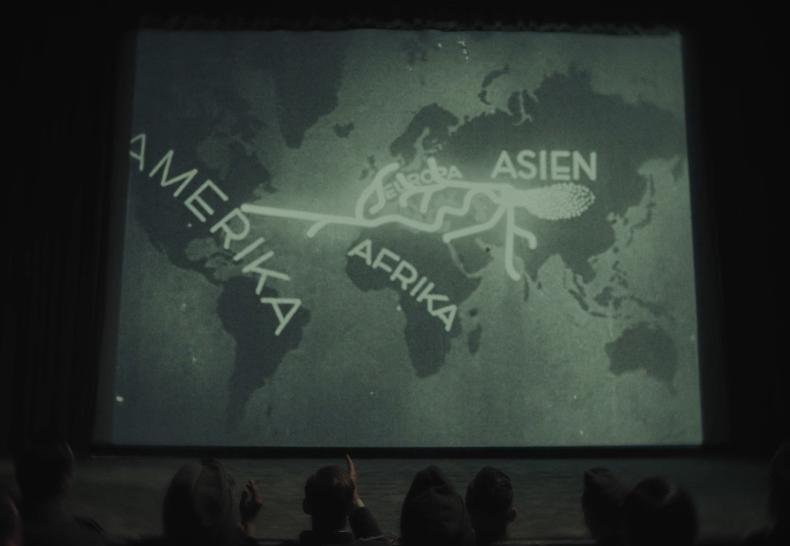

The same is true for the notorious antisemitic propaganda film DER EWIGE JUDE, which is the topic of Daniel Körling's article. In it he reveals how fragments of this Nazi-era film have scattered across documentaries for more than 60 years – some handle the poisonous images with proper warnings and context, while others, disturbingly, repackage them as generic historical footage, stripped of their murderous intent. In addition to the afterlife of DER EWIGE JUDE the production of the film itself is scrutinized with a fresh eye, followed by an analysis of the exhibition Der ewige Jude and its accompanying booklet as prototypes for the film.

Eva Braun’s home movies, set in the period between 1938 and 1944, document personal moments with her proper family as well as with her second family comprised of Nazi officials. They were archived as “Private Motion Pictures of Adolf Hitler and Eva Braun” at the NARA archives. Aleksandra Miljković explores Braun's role as a filmmaker, analyzing how these films express her agency and identity. She also traces the trajectory of Braun's images from their post-war use in American newsreels to their rediscovery and rising prominence in the early 1970s.

The film footage of several mass shootings of Jewish civilians taken by German naval soldier Reinhard Wiener in the dunes of the Latvian coastal city of Liepaja became a central part of the visual memory of the Holocaust. Since its first use in the West German television documentary AUF DEN SPUREN DES HENKERS (BRD 1961) and at the latest with their inclusion in the American mini-series HOLOCAUST (USA 1978) the footage turned into “migrating images.” Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann asks what these images actually show, and how they can be categorized and decoded. Based on Wiener’s own description of the film as a “living document of events” in Liepaja, he pursues a visual archaeology to uncover various layers of its production and use.

In the spring of 1942, uniformed German cameramen of the so-called Propagandakompanien (PK) shot at least ninety minutes of 35 mm film footage in the Warsaw Ghetto. This unfinished project was unusual: while it portrayed the inhabitants of the ghetto along established anti-Semitic stereotypes, using authentic as well as staged scenes, it also documented Jewish traditions and customs. The film was rediscovered postwar in several distinct parts, in different archives, and at different times, which has led to a peculiar history of appropriation, in which filmmakers have only gradually availed themselves of all available parts of the surviving material. Alexander Zöller reconstructs the archival provenance of the ghetto film, arguing that it can help to better understand not only its ongoing appropriation in documentary and feature films but also inform a more reflected and critical use of the footage going forward.

In the final article, Fabian Schmidt examines the image migration of the Westerbork film and reconstructs its impact on the formation of Holocaust remembrances. The Westerbork film has been part of the visual history of the Holocaust since its prominent use in Alain Resnais’ essay film about the camp system NUIT ET BROUILLARD (1956). In 2017, the material was included in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register acknowledging its importance as a document of the ghettoization and deportation of Jews in Western Europe during World War Two. The Westerbork film has been used in Holocaust documentaries, art films and even in feature films, and today some of the images, such as the girl looking down from the cargo train, are considered iconic. Schmidt critically questions claims of overuse of this footage and tries to replace unfounded assumptions of repetition with the outline of a culture of use that is manifest in the hundreds of cases of appropriation that were examined.

Chris Wahl and Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann

Potsdam and Jerusalem, April 1, 2025

Acknowledgements: Our sincere thanks to copy editor Aksana L. Coxhead (Ewert-Sprachendienst e.K.).

Suggested Citation: Wahl, Chris, and Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann. “Issue 7: Editorial. Iconic Film Footage from the Nazi Era.” Research in Film and History 7 (2025): 1–9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/24052.