Transitions and Cinematic Dimensions of In-Betweenness in the Films of Vesna Ljubić

THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY (1986) and DEFIANT DELTA (1980)

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

The cinema of the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia encompasses films made by Yugoslav directors from roughly 1947 until 1991. During this period, there were only a very few women directors of feature-length fictional films, such as Sofija ‘Soja’ Jovanović,1 Gordana Boškov, Marija Marić, Suada Kapić, Eva Balaž-Petrović, Ljiljana Jojić.2 Another name that belongs on this list is Vesna Ljubić (1938–2021), whose films I shall be discussing in this article.

Ljubić’s film career began when, after graduating in philosophy at the University of Sarajevo, she went to Rome to study film directing at the Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia (CSC) and worked as an assistant director for the renowned Italian filmmaker Federico Fellini.3 She later returned to her home country, where she made important fiction and documentary films during both the Yugoslav and post-Yugoslav period. For my case study, I have selected her two feature-length fictional films from the Yugoslav period: THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY (Posljednji skretničar uzanog kolosijeka; Yugoslavia 1986) and DEFIANT DELTA (Prkosna delta; Yugoslavia 1980),4 which was also edited into a TV series of the same name (Yugoslavia 1982).

My aims in this article are: (1) to investigate whether these two Ljubić films have been digitised and what factors might have influenced that (including the director’s gender); (2) to give a close reading of depictions of the past, transcendental states and memory in Ljubić’s films through a postcolonial and post-Yugoslav lens; and (3) to explore, by applying feminist film theory, whether Ljubić as a woman director shows a particular interest in themes specifically relevant to women, whether she places female characters in the spotlight and, finally, whether she subverts gender stereotypes, reinforces them or leaves matters ambiguous in her films. All of these aims can be encompassed under the overarching heading of transitions, as I will identify several types of transitions in the films I analyse here. Specifically: transitions from old analogue film to digital film (digitisation), from past to present, from colonial to postcolonial, from life to death, from reality to dream, from Yugoslav to post-Yugoslav and from a predominant focus on male directors in previous scholarly accounts to a focus on a female director.

1. Transitions from Analogue Film Stock to Digital Film – Digitisation

Most of the films directed by Yugoslav women directors, especially feature-length fictional ones, have not been restored or digitised,5 have not been subtitled in English and are not available on DVD or on legal streaming platforms (they only occasionally appear on TV or pirate pages, in low quality). This is an example of what Sanja Bahun and V. G. Julie Rajan call ‘the workings of gender difference in patriarchal contexts – a societal dynamic that requires the consistent privileging of masculinity over femininity in an assumed heteronormative framework’.6 Women filmmakers from all parts of the world, particularly those from the Balkans and Eastern Europe, are often neglected, sidelined and overlooked in film histories, because the spotlight is mostly on male directors – a phenomenon discussed by only a few scholars, such as Dina Iordanova7 and Ana Grgić.8

Additionally, the transition from analogue film to digital film (digitisation) has been rather slow in the former Yugoslav socialist republics, which constituted former Yugoslavia in the past, and then later, after Yugoslavia fell apart, became independent states. The main reason is the archives’ lack of funds and equipment. Furthermore, the situation in the former Yugoslav territories is sometimes more complex due to unclear copyrights or copyrights that are shared between the successor states. Moreover, Yugoslav films are often regarded as unwanted heritage of a bygone era if they and their directors cannot be reinterpreted through the national lens of one of the post-Yugoslav states (e.g. as Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian, Montenegrin, Slovenian, Macedonian).9 This is the case with Ljubić’s films: ‘Remaining independent of any political or ethnic orientation, Ljubić’s films are usually first acknowledged abroad, to be recognized at home only later,’ notes film curator, scholar and director Rada Šešić,10 who roughly four decades ago was Ljubić’s assistant director on THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY.

However, film negatives and positives are perishable, and so there is a pressing need to raise awareness of films by female Yugoslav directors, as that might increase their chances of restoration and digitisation. The two films by Ljubić that I analyse here are at risk of being lost, because they have not yet been digitised. According to information provided by Aleksandar Erdeljanović, the deputy director of Jugoslovenska kinoteka – Yugoslav Film Archive in Belgrade (Serbia), this archive (which used to be the biggest in Yugoslavia) has a copy print of DEFIANT DELTA without subtitles and only an archival print of THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY.11 Meanwhile, Ines Tanović, head of the Film Centre Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina) as well as a film director in her own right, and Ema Muftarević, who is in charge of digitisation at the centre, report that their archive has three episodes of the TV series DEFIANT DELTA, only as a single archival copy on film positive print (two to three reels per episode), but unfortunately they have not been digitised because some of the material (four reels) is infected with mould. This is apparently a widespread problem at the centre, which has caused the loss of many films.12 The Film Centre Sarajevo does not have a complete physical print of THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY, as the soundtrack is missing. Besides the mould issue, the archive’s storage problems appear to be due to a series of factors beyond its control, such as damage to facilities and materials during the war (1992–1995), and a lack of funds for repairs to facilities and for restoration and digitisation equipment.13 The Film Archive of Bosnia and Herzegovina (Kinoteka BIH), also located in Sarajevo, encountered similar problems. A single 35 mm copy of DEFIANT DELTA is stored there, albeit in a very bad state. There are no copies of THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY on film at all in Kinoteka BIH; except only on DVD with hardcoded subtitles in Slovenian.14As stated by Devleta Filipović, the head of this archive, another issue is that the original film materials are kept in present-time Croatia, namely in the Croatian Film Archive (Hrvatska kinoteka) in Zagreb. Before that they were also stored in Zagreb, in the (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Croatia, but in Jadran Film (a production studio and distribution company from Yugoslav period), since laboratory processing had been done there. This is because there was no colour film laboratory in the (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina.15 After the breakup of Yugoslavia and the privatization of Jadran Film, the materials in question were handed over to the Croatian Film Archive.16 Another part of the materials is preserved in the Yugoslav Film Archive (Jugoslovenska kinoteka) in Belgrade (in present-time Serbia). The original film materials were handed over there for safekeeping as a general rule during socialist Yugoslavia. However, says Filipović, the availability of the materials has become a challenge since the breakup of Yugoslavia.

It is also important to mention that DEFIANT DELTA was 100% produced by companies from the former (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, whereas THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY had majority co-producers from the (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and minority co-producers from the (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Croatia and the (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Serbia.17 This means that the Film Centre Sarajevo (in present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina), as the legal successor of former production companies from the (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, has the rights to these films.18 However, as mentioned above, the positive prints of THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY and DEFIANT DELTA held by the centre are respectively incomplete and infected by fungi. Digitising Ljubić’s films would therefore probably require collaboration with other archives, such as Jugoslovenska kinoteka in Serbia and Hrvatska kinoteka in Croatia, because it would seem they may have better copies of positive prints (and perhaps even negatives). The fact that this would be a matter of international collaboration between three countries, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, and Serbia, further complicates the films’ digitisation prospects. But at a time of transition from analogue to digital, these films urgently need to be digitised or they are in danger of being lost forever. By analysing two selected films by Ljubić and highlighting their artistic significance, this article will hopefully help to raise awareness of them and make it more likely they will be digitised.

2. Political and Historical Transitions

THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY is set in 1970s socialist Yugoslavia, specifically in Bosnia, while DEFIANT DELTA takes place in Herzegovina at some unspecified point in a distant, fictionalised, pre-socialist past. In the 1980s, when the two films were made, their respective filming locations were in the Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, and in the Socialist Republic of Croatia (in the latter film), which in turn were two of six republics that constituted the Socialist Federative Republic of Yugoslavia.

THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY is a film about the people working at a small, rural train station and how their lives are negatively impacted by the closure of the eponymous narrow-gauge railway. DEFIANT DELTA, meanwhile, portrays the lives of people whose village is regularly pillaged by different armies and hit by recurrent flooding from the river Neretva and nearby lakes during rainy periods, which takes a heavy toll due to the village’s unfavourable geographical location on a river delta. A village girl named Ivana (played by Gorica Popović), whose parents died in one of the many floods, wants to obtain explosives from the soldiers by any means so she can make a tunnel to drain excess water into the sea. However, her efforts are in vain, and she pays with her life for trying to defy both humans and nature.

In these two films, political and historical transitions are caused either by humans or by natural phenomena. While in DEFIANT DELTA human-caused transitions (pillaging armies) and natural ones (frequent deadly flooding) occur cyclically, in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY there is a one-off human-caused transition resulting from the closure of a railway that is seen as a remnant of colonial rule by the Austro-Hungarian Empire, which had originally built it to exploit resources.

a) Transitions and Remnants of the Colonial Past

Like DEFIANT DELTA, THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY is filmed in the (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, now a separate country with a complex history. At the Congress of Berlin in 1878, control over the territory, which had until then been occupied by the Ottoman Empire, was granted to Austria-Hungary. However, what was only meant to be a temporary administration in fact became an occupation.19 Subsequently, Austria-Hungary formally annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1908, contrary to the terms of the treaty signed in 1878 at the congress.20 In 1914, the First World War broke out, triggered by the politically motivated assassination of Austro-Hungarian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo. The assassination was carried out by the young Gavrilo Princip, who supported the unification of the southern Slavs and the overthrow of Austria-Hungary’s colonial rule.21 When the war ended in 1918, this likewise brought an end to Austria-Hungary’s annexation of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the territory became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes.22 In 1929, the kingdom officially changed its name to the one that was already being used colloquially: the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (meaning ‘the Land of the South Slavs’).23 During the Second World War, Bosnia and Herzegovina’s territory was annexed and became part of the fascist ‘Independent State of Croatia’ (1941–1945),24 a puppet state formed by the Axis powers. During the liberation struggle, the foundations of socialist Yugoslavia were laid (with Bosnia and Herzegovina as one of its constituent republics), and when the Second World War ended in 1945, the war-torn country ‘launched the struggle to build a new society on its own model: to become industrialized but at the same time to create a new social ethic’.25

In THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY, there is a character called Miss Clara (Jasna Beri) who is like a recurring glitch, a lingering remnant of the Austro-Hungarian past and an embodiment of its colonial rule, signifying an unfinished transition to socialist Yugoslav society. In the film, it is revealed that during Austria-Hungary’s occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Clara’s late grandfather, Rudolf von Messner, built the train station Brezovi dani. Clara periodically appears throughout the film, always punctually on time for a passenger train. She walks seductively, wearing a tight black dress, a black hat, elegant black gloves and sunglasses, as if she were a widow in mourning for a bygone era. Her appearance is always accompanied by a quirky, non-diegetic instrumental tune, which becomes Clara’s leitmotif. The music makes the sequences with Clara stand out, amplifying the sense that she is the incarnation of Austria-Hungary’s former imperialism, who symbolises its influence and the consequences of its occupation of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

On the one hand, Clara’s body is visually represented as sexually objectified, due to the seductive clothing she wears and a camera framing that fragments her body into features such as buttocks and breasts – an example of what Laura Mulvey calls the ‘male gaze’.26 On the other, the character of Clara narratively subverts patriarchal stereotypes, because she is not represented as passive in the way that female characters often are. Instead, she is a female exhibitionist. She routinely exposes her breasts to male passengers on passing trains, who then watch her from the windows. Later in the film, after the narrow-gauge railway is permanently closed, there is a scene where it looks like a hitherto seemingly harmless male character, Mungo (Mustafa Nadarević), might try to sexually harass her. She turns the tables and remains in control by voluntarily exposing her breasts to him. Although he is tempted and appears to reach out to touch Clara’s breasts, Mungo resists the urge. He closes her shirt, covers her breasts and tells her, breathing heavily, ‘Miss Clara, there is one place where trains still pass.’ She starts laughing and, as he runs away, she exposes her breasts again (Figure 1), but this time to nobody, because there are no longer any trains passing by. The character of Clara, who walks around as a beautiful but haunting spectre, functions as a remnant and reminder of the colonial past, which lingers despite the transition from Austria-Hungary to the socialist society of Yugoslavia.

b) Transitions and Sonic Icons

In both films, political and historical transitions are expressed not just visually but also aurally, via the creative use of sound in general, and especially via the scores (composed, respectively, by the Greek composer Vangelis (DEFIANT DELTA) and the Yugoslav Vladan Radovanović (THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY)). Moreover, there are several types of music in both films that are rooted in and inspired by regional traditions. For instance, in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY there is sevdalinka (or sevdah music), which recalls both the dark days of the Ottoman occupation and its arguably more positive musical influences.27 Furthermore, a brass band appears in the film, which has a twofold meaning. On the one hand, as one of the main protagonists, railway switchman Marko Mrgud28 (Velimir ‘Bata’ Živojinović), complains, the classical brass music has negative, colonial connotations, signifying the Austro-Hungarian occupation. On the other hand, for other characters, such as the train dispatcher Martin Sudar29 (Boro Stjepanović) and his wife Japanolija30 (Jadranka Matković), the music has positive connotations, because it represents culture, urbanity and progress. In contrast, folk music, such as that played for the traditional kolo dance, is regarded as rural and so implicitly as backwards or retrogressive. The music therefore sheds light on the past of the (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina and the inequalities between rural and urban structures in socialist Yugoslavia, where nominally everyone was equal.

Opinions about music are not the only line of conflict in the film. There are also occasional clashes between different types of diegetic music, such as brass band music and folk music, which sometimes play at the same time. For instance, during the parade at the small rural train station that is organised to mark the permanent closure of the narrow-gauge railway, a narrow-gauge train of the model nicknamed ‘Ćiro’ arrives at the station for (what is presumed to be) the last time. The train is decorated with a banner that reads ‘Ćiro is leaving and diesel is coming’ (in Serbo-Croatian: ‘Ćiro odlazi, dizel dolazi’). People holding flags are standing on top of the locomotive. Others are standing in the closed carriages and waving from the open windows. Some of them, in an open-top carriage, are dancing a kolo dance to traditional music and wearing traditional clothing. When the ‘Ćiro’ arrives at the small station, its traditional kolo music clashes with the live brass band music being played by an orchestra at the station, creating a cacophony of sound. As mentioned above, this signifies a collision between rural and urban, underpinned by contested opinions about backwardness and progress. The sonic harmonies and cacophonies, in combination with the visual elements, are crucial for pinpointing historical and political transitions. This sequence can be read as an example of how, as film scholars Winfried Pauleit and Rasmus Greiner put it, sonic histospheres ‘emphasize films as complex audio-visual constructions of a historical world’.31 Furthermore, both the ‘Ćiro’ train and the brass music are remnants of Austro-Hungarian colonial rule. Ironically, while the former is perceived as backwards, rural and outdated by Yugoslav decision-makers and their sycophant Martin (the train dispatcher), the latter is, as discussed above, linked to notions of urbanity, culture and progress, which suggests double standards regarding Austria-Hungary’s colonial legacy.

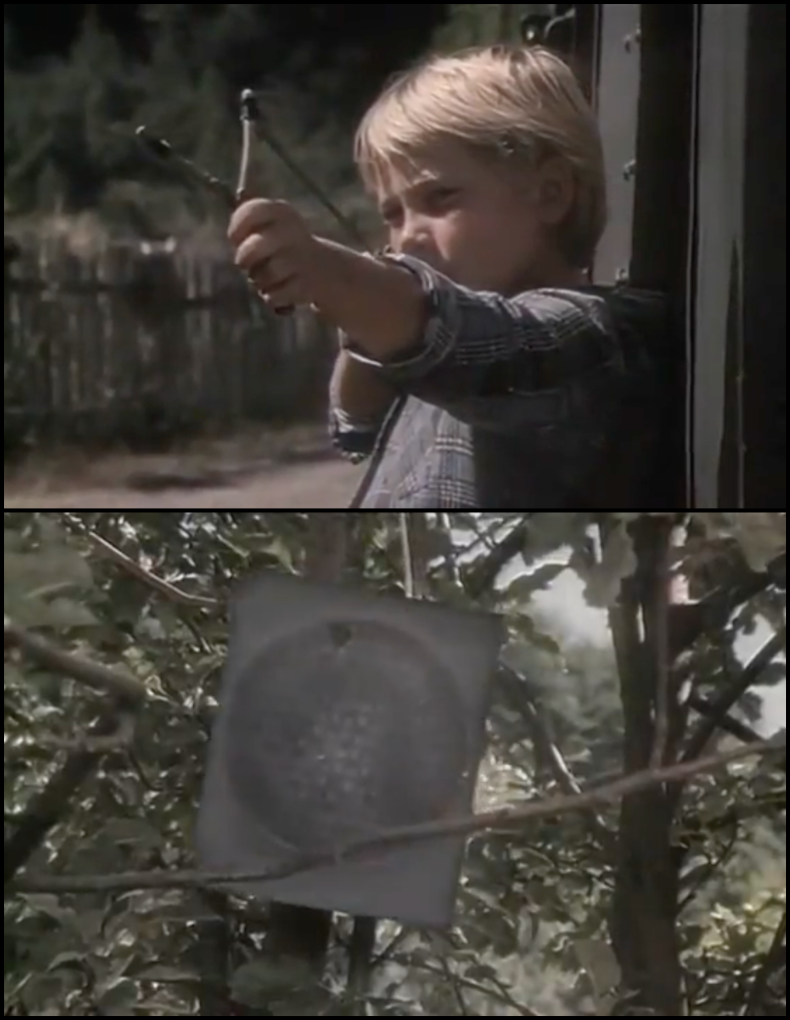

In addition, both films feature the singing of traditional songs, which occasionally become acts of defiance. In DEFIANT DELTA, this is a cappella singing by the villagers in defiance of foreign soldiers. They are fed up with years of foreign soldiers coming to the village under the banners of various armies to pillage livestock and food, conscript men by force, kill people, burn houses, or sexually assault women. In a similar vein, in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY a rural woman named Luca (Kaća Čelan) mounts a small act of defiance by singing a folk song a cappella in support of her husband, the switchman Marko. The song is a protest against the urban woman Japanolija, who is the wife of the train dispatcher Martin. Luca’s singing is preceded by an argument between Marko on the one side and Martin and Japanolija on the other, during an outdoor party organised at the station Brezovi dani to celebrate Marko preventing a train accident.32 The argument concerns the live brass band music that is being played. Japanolija and Martin are in favour of the music. In contrast, Marko, for whom the brass music signifies a remnant of the Austro-Hungarian colonial heritage, would prefer to hear traditional kolo music at the party organised in his honour. The dispute is resolved when their boss, Mr Kopecki (Edo Liubich), starts playing a guitar and singing a sevdalinka song (a traditional folk genre whose lyrics are often about unrequited love and longing). This song genre could be interpreted as signifying the Ottoman occupation and its musical influences, which over a long period of time merged with the traditional oral poetry of the South Slavic population.33 However, everyone seems to be content with Mr Kopecki’s performance – even Martin starts singing along – except for Japanolija, who is infuriated and goes back to her house at the station. Japanolija wants to impose ‘cultured’ opera music on the villagers and anyone else she sees as ‘backwards’. She starts playing it on a gramophone connected to a loudspeaker in order to deliberately interrupt the party. ‘When microphones, loudspeakers, and sound recording equipment appear in films, their appearance creates a self-reflexive potential,’34 according to Pauleit. This opens up a space for ‘sonic icons’, defined by Pauleit as ‘self-reflexive moments in specific films where the sound comes to the fore and reveals specific historical references’.35 By invoking or facilitating a reminiscence of the past, sonic icons reveal their link to specific historical moments and, just like every representation, have the potential to transform and construct those moments instead of merely reflecting them.36 The defining quality of a sonic icon, as Pauleit notes, lies ‘in the reference to something from the past, in a trace that enables something absent to be identified’.37 In sonic icons, sound is not a stand-alone category, but rather is in constant interplay with image and text, thus creating a new meaning.38 Given that, it is significant that Pero Mrgud (Figure 2a), the son of the rural woman Luca, destroys the loudspeaker with his sling (Figure 2b) in a futile attempt to silence the opera music. This transcends the act of a child misbehaving and becomes a social critique of the urban–rural divide. Even more enraged, Japanolija returns to the party, demanding to find the perpetrator who damaged the loudspeaker, and hurls insults at everybody, calling them ‘Vandals! Peasants! Provincials!’ A sonic cacophony then occurs when Luca, representing the rural side of the rural–urban divide, starts singing a traditional song a cappella over the opera music, in support of her husband Marko and son Pero and against Japanolija, who signifies the urban side. This sonic icon becomes a social, historical and cultural commentary, in defiance of the attempt to impose cultivation that is represented by opera music.

c) The Colonial and the Imperial Gaze

Besides the musical references to the colonial past, such as the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian occupations of Bosnia and Herzegovina (which, at the time the film was produced, was the (Yugoslav) Socialist Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina), and the visual references to the latter occupation embodied in the character of Clara in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY, DEFIANT DELTA also contains visual references to the ‘colonial’ and the ‘imperial’ gaze. Image as well as sound is used to address the colonial past and its legacy, or to subvert and defy the ‘colonial gaze’. The terms ‘colonial gaze’ and ‘imperial gaze’ (which may be used interchangeably) refer to an ideological construct, mainly found in film narratives and discourses from Western countries, in which colonised people are (mis)represented by exploitative colonial powers as sexualised and are racially or ethnically othered.39 By creating existential, social and political distance between themselves and the colonised, colonisers often hypocritically attribute to the colonised negative traits (such as patriarchal attitudes) that actually also apply to Western societies, while simultaneously stereotyping the colonised as an exotic, primitive, uncivilised, inferior Other.40 To quote E. Ann Kaplan: ‘The imperial gaze reflects the assumption that the white western subject is central, much as the male gaze assumes the centrality of the male subject.’41 Kaplan, who is primarily referring to Hollywood cinema, and to some extent also to British cinema, equates ‘male gaze’ and ‘imperial gaze’ inasmuch as white Western men are the subjects of both. In a similar vein, Freya Schiwy42 argues that the ‘colonial gaze’ is both imperial and masculine, while Ella Shohat says that Western cinema43 and its constructs are products of a colonialist imaginary and a gendered Western gaze, due to the symbiosis ‘between patriarchal and colonial articulations of difference’.44 Both Kaplan’s understanding of the ‘imperial gaze’ and Shohat’s and Schiwy’s definitions of the ‘colonial gaze’ highlight the racial scrutiny of these (white) gazes. Even though there are no people of colour in the films directed by Ljubić that I am analysing here, they do take place in the Balkans. According to Maria Todorova,45 this is a region that perpetually has liminal status within Europe: as its periphery, its subaltern, its inferior Other. That implies a colonial power dynamic. I therefore believe postcolonial theories of the colonial gaze and imperial gaze are applicable to my analysis.

In DEFIANT DELTA, Ljubić’s representational style is indeed such that the colonial gaze visually corresponds to the male gaze. This can be related to Schiwy’s observation that ‘when the male gaze coalesces with colonial desire, film constructs a patriarchal imperial-looking convention’.46 However, in Ljubić’s film, the male gaze and colonial gaze are aligned so that they can both be implicitly criticised and eventually subverted. For example, a carnival takes place in the village, during which the villagers dress in costumes, most of which are improvised from their own clothing. They wear masks made from pumpkins or weaved reeds, or put on moustaches and wigs made from wool. Some wear authentic foreign soldiers’ uniforms: their hands are tied and they are escorted by other villagers as captives. Others carry what look like scarecrows (most likely so-called pustovi), which they eventually hit with sticks. Villagers parade, dance, sing and make a lot of noise. This is a traditional custom whose purpose is to drive away the evil spirits, demons, werewolves and nightmares from people and their homes, to bring them good marriage prospects and good health and to ensure abundant crops and cattle.47 The scarecrows are reminiscent of the witch from AMARCORD (Italy 1973; dir. Federico Fellini), which is placed on a bonfire by the townspeople at a traditional carnival event in order to chase away the winter and cold, and help the spring to come.

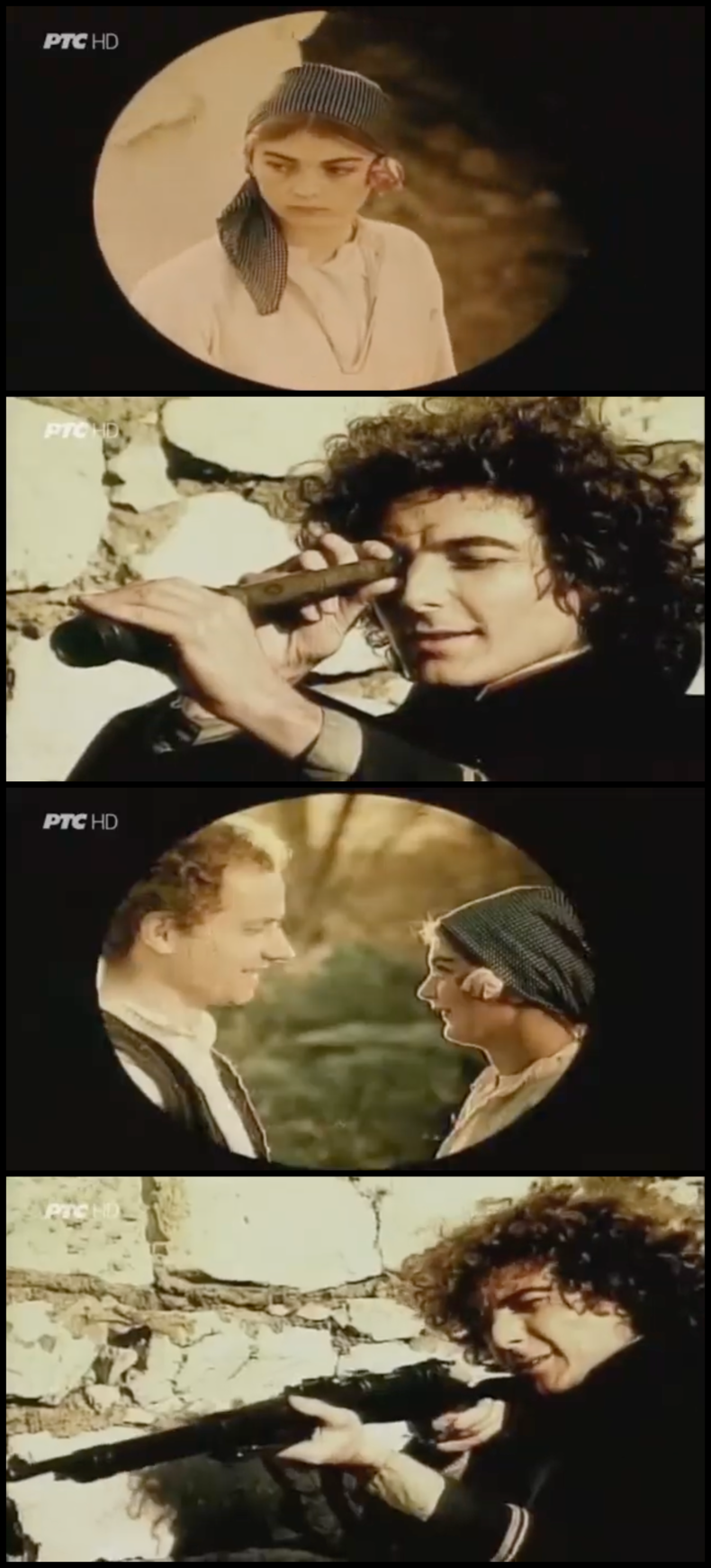

In another scene from AMARCORD there is an orientalist, sexually objectifying representation of harem women from the perspective of a mythomaniac Italian character. With this representation, director Fellini reinforces the colonial gaze or imperial gaze, in contrast to his former mentee Ljubić, who condemns it. At the carnival in DEFIANT DELTA, one foreign soldier observes the villagers through a monocular from the high-up, distant vantage point where he is posted. At first, this appears to be a typical example of the colonial gaze, where the coloniser is looking down (in this case also literally) on the colonised, who are represented as somewhat exotic and primitive due to their participation in the carnival. Then, among the villagers he notices a beautiful young girl (Figure 3a). Ljubić visually represents this sequence using close-ups of the soldier, who is holding a monocular and peering through it (Figure 3b), intercut with his point-of-view shots, showing what he is gazing at – the young girl (in close-ups). To make the close-ups of the girl look the way they appear to the soldier through the monocular, a visual effect has been applied to add a black circle (mask) around her. This is an example of male gaze, as defined by Mulvey,48 in which women are objectified. At the same time, it is an instance of the colonial gaze, which ‘is predicated on bodily distance between the gazing subject and the object of gaze’.49 The foreign soldier sees the young girl start to interact with a young man. The two of them appear to like each other (Figure 3c). In a fit of jealousy, the soldier puts away the monoscope, takes a rifle (Figure 3d) and shoots the young man dead. At this point, Ljubić subverts both the male gaze and the colonial gaze. The former is subverted when the young girl, in tears, defiantly gazes back in the direction of the gunshot (and the soldier’s gaze). The colonial gaze is also subverted when the villagers, who at first appeared primitive, superstitious, backwards and barbaric, one by one take off their masks and hats, and likewise gaze back at the representative of colonial power, who has suddenly become the barbaric one. Startled, frightened or ashamed, the soldier turns his back and returns to the safety of his military post.

Another example of exposure to the male gaze and colonial gaze occurs in a sequence where four village girls, who are washing their feet in a body of water, possibly a lake, are interrupted by three foreign soldiers. One of the girls is Ivana, who wants to obtain explosives in order to make a tunnel in the mountain so that excess water (from the river Neretva and nearby lakes) will drain into the Adriatic instead of flooding the village. When the soldiers arrive, Ivana is naked above the waist. The situation is reminiscent of classical paintings of Susanna and the Elders, in which Susanna is shown bathing while lecherous old men gaze at her. However, in the film, Ivana’s nudity is less emphasised than in those paintings.

DEFIANT DELTA’s depiction of a woman being observed while bathing or showering differs from examples of similar scenes in films by male directors (who also include such depictions more frequently than female directors), for instance in THE MAN WITH THE GOLDEN GUN (UK and USA 1974; dir. Guy Hamilton) and EARLY WORKS (Rani radovi; Yugoslavia 1969; dir. Želimir Žilnik).

A Susanna and the Elders painting actually appears in PSYCHO (USA 1960; dir. Alfred Hitchcock),50 which Norman Bates (Anthony Perkins) removes from the wall so he can spy through a peephole at a woman undressing for a shower. Male directors typically show the nude woman as lascivious, or in close-ups and with fragmented details of her sexually objectified body. In DEFIANT DELTA, by contrast, Ivana, semi-nude with bare breasts, is shown in a long shot, together with the other girls and three foreign soldiers who suddenly intrude on them. Because her back is turned while she washes herself, Ivana is unaware of the soldiers’ unexpected presence until one of the other girls warns her to cover herself. At that moment, her half-naked body is bent as she reaches for the water. Ivana then stands up and turns around to face the soldiers, saying to her friends, ‘They shouldn’t watch, if they don’t want to.’51 One of the soldiers exclaims, ‘Ooh la la!’ Ivana starts putting on her blouse. The soldiers approach, while the other girls leave. Ivana, fully clothed and alone with the three soldiers, initiates a conversation with them about explosives, because ever since she lost her parents in a flood, she has been obsessed with obtaining explosives to build a tunnel to drain excess water into the sea. Vangelis’s score starts up. The conversation is then muted and the scene stops. There is a visual cut, with the music serving as a sound bridge to the new scene until it also stops.

In the new scene, we see other villagers. After some time, a small boy wearing an altar boy surplice comes running and yells ‘People! Help! They’re killing Ivana! Help Ivana! Faster!’ Male villagers rush to her aid. They find she is being gang-raped by the foreign soldiers in a field. Shots of villagers approaching by land and ambushing the soldiers are intercut with shots of big wooden crosses gliding along the surface of the nearby lake or river. The crosses appear to be moving because they are standing on the decks of boats, as part of a religious procession on the water. The sequence is accompanied by a male and female a cappella choir (only audible, but not shown) singing a religious song. White, fluffy seeds (perhaps from poplar or willow trees), are floating in the air, reminiscent of the blowballs in AMARCORD. The villagers then kill at least one of the soldiers by strangling him. Ivana is distraught and in shock. The villagers argue about possible retribution for killing a foreign soldier. Eventually, after being gently told by one of the villagers, Vrane (Žarko Mijatović), to go home, Ivana starts running through the crops, captured by a telephoto camera lens in a series of following shots, only to eventually fall to her knees after seeing the moving crosses from the boat procession and hearing the a cappella prayer that underscores this sequence.

In her representation of gang rape as severe sexual violence, Ljubić subverts the patriarchal stereotype, which often blames the female victim for allegedly provoking the rape by the way she dressed and behaved, and instead places responsibility on the soldiers, who made a deliberate choice to stare at Ivana’s semi-nude body and then sexually assault her, even though she only wanted to talk.

However, besides dealing with gang rape as a serious act of sexual violence perpetrated in warzones, Ljubić simultaneously approaches the problem of gang rape allegorically. There are many other instances of Yugoslav and international directors, especially men, using representations of raped women as allegories of a nation, to symbolise a country being politically or economically exploited. This can potentially be very problematic, especially if a female character who is raped is sexually objectified by the visual representation and narrative.52 Since Ljubić’s depiction of the gang rape of a local woman by foreign soldiers involves certain colonial power relations, it can indeed be read as an allegorical representation of an exploited country that is forcibly deprived of everything, humiliated and given nothing in return. However, Ljubić is able to deftly address predicaments of sexual violence, colonialism and militarism in the context of war, and the ensuing transitions in the affected countries, without falling into the trap of sexually objectifying her violated female protagonist, Ivana.

3. Transitions to Oneiric States

Besides political and historical transitions, both of the Ljubić films feature transitions to oneiric states. Visual elements that facilitate the transition to such states include locomotive steam, which is often seen in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY when the train appears, and smoke and fog, which appear in dreamlike shots in DEFIANT DELTA. Furthermore, the sensation of in-betweenness, of being between reality and dream, is amplified by the presence of female twins in both films, because they are reminiscent of doppelgangers, that is, phantom counterparts or doubles of a living person, which are regarded as inauspicious. Such doubling strengthens the sense of uncanniness and dreamlike-ness. A parallel can be drawn to the female twins in JULIET OF THE SPIRITS (Giulietta degli spiriti; Italy 1965; dir. Federico Fellini).

Although the presence of female twins in DEFIANT DELTA and THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY railway is not as ominous as in, say, THE SHINING (USA 1980; dir. Stanley Kubrick), in both Ljubić’s films they do get someone in trouble. For instance, in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY, there is a scene when 11-year-old Pero sneaks into the office of the train dispatcher Martin, the boss and archenemy of his father, the switchman Marko. Pero plays around and short-circuits some cables, which triggers a sound like an alarm and makes people think there is an emergency because a train is about to unexpectedly arrive at the station. Later, Pero tries to sneak out of Martin’s office, only to be spotted by one of Martin’s young twin daughters (Figure 4a). Because of Pero’s actions, disciplinary measures are taken against Marko, who then beats Pero.

Similarly, in DEFIANT DELTA, two adult twins bring bad luck to a foreign deserter. While the deserter is undressing to join the twin girls (Figure 4b), who are swimming in what is presumably a lake, and performing acrobatic feats to impress them, two soldiers on horseback arrive. They realise that the soldier has deserted their army and consequently shoot him, to the dismay of the twins and their little sister. So it is possible to conclude that the female twins that appear in the two films by Ljubić bring bad luck to other characters, creating an impression of peculiarity and in-betweenness.

4. Transitions from Life to Death

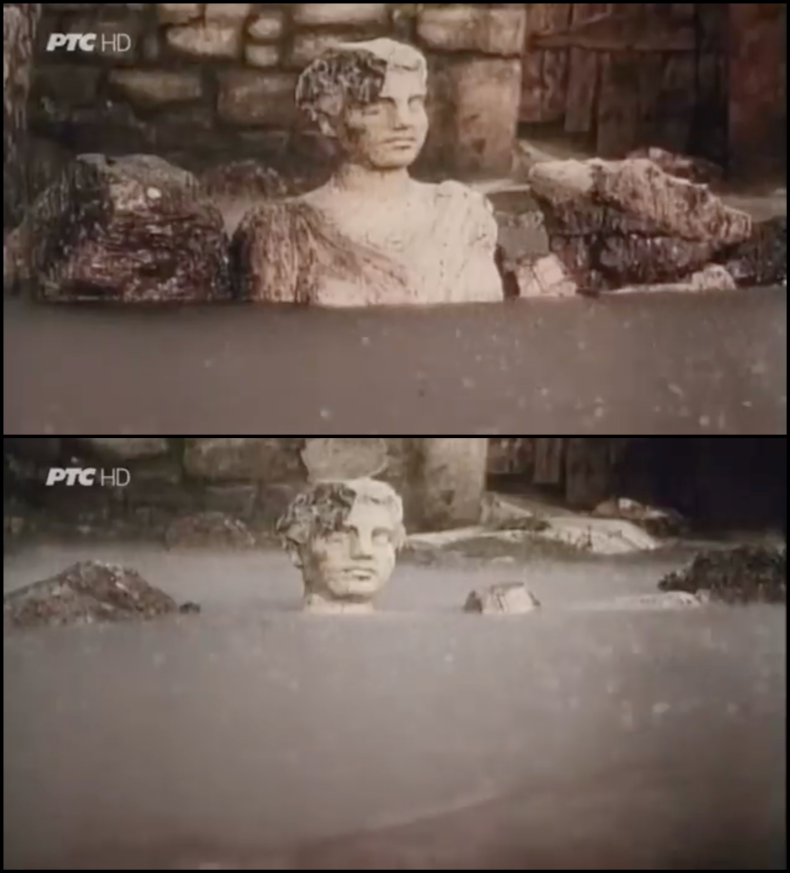

In Ljubić’s films, transitions from life to death are represented visually (for example, by the use of dreamlike sequences) or aurally (for instance, by the use of music, off-screen sound or oneiric soundscapes). In DEFIANT DELTA, transitions from one world to another sometimes take place by boat. This is reminiscent of the boatman Charon from Greek and Roman mythology (the latter originated from the former), whose task was to ferry the souls of the departed to the underworld over the rivers Acheron and Styx.53 One example of this is a scene in DEFIANT DELTA where a deceased villager is transported by boat, accompanied by a priest in another boat. There are also apocalyptic images of villagers taking refuge in boats during a fire and a flood. Water is an important element in DEFIANT DELTA – both a blessing and a curse. An ancient statue, possibly Hellenic or Roman, serves as a marker of the rising water level during floods (Figure 5a). If the water reaches the statue’s head, it signals a state of emergency: villagers must flee for their lives by boat (Figure 5b). A visual parallel can be drawn with films by the Greek director Theo Angelopoulos that feature boats, rafts or vast bodies of water, such as THE HUNTERS (Oi kynigoi; 1977), which was made before DEFIANT DELTA, and VOYAGE TO CYTHERA (Taxidi sta Kythira; 1984) and TRILOGY: THE WEEPING MEADOW (Trilogia: To livadi pou dakryzei; 2004), which were made after it. An aural parallel with Greece is marked by the Greek composer Vangelis, who composed the music which is heard in DEFIANT DELTA (but who as far as I know did not work with Angelopoulos). Moreover, the fact that Ljubić’s mentor and one of her key influences was the Italian director Fellini and that she lived in Rome while studying film54 may add another layer of ‘Graeco-Roman-ness’ to her film work.

In the films selected for the present case study, visually represented transitions from life to death often involve an animal, such as a rooster in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY or a dog and goats in DEFIANT DELTA. The precise moment of all these deaths takes place off-screen. The deaths are not directly shown, but implied. The indirect, inferred, unshown moment of transition from life to death can be related to ‘[Siegfried] Kracauer’s analogy between the cinema screen and Athena’s polished shield, a mirror that makes it possible to behold horrors without turning to stone’.55 The Greek virgin goddess Athena (Minerva in Roman mythology) gave a mirrored shield to the hero Perseus (from Greek and Roman mythology) so that he could look indirectly at Medusa without being turned to stone, enabling him to kill her.56 In my view, killing Medusa was a questionable act, given that she was a victim of rape, and it indicates how the mythology was male-oriented. However, Kracauer’s57 mythologically inspired analogy of cinema as a mirrored shield that does not merely reflect, but indirectly refracts, distorts, embellishes, polishes or makes bearable the events it represents, as well as Greiner’s58 reading of that analogy, captures the gist of how Ljubić often depicts her characters’ deaths. Specifically: they are hidden off-screen and associated in some way with an animal, which shields the viewers by making the deaths more bearable, allegorical and transcendental.

The death of retired railway worker Pero Mrgud (Milan Srdoč) (Figure 6a) is foreshadowed by the reappearance of his lost pet rooster (Figure 6b) on top of a passing train. Earlier in the film, the rooster had been shown always accompanying Pero. It is trained to jump into Pero’s arms when he blows a whistle. The rooster gets lost when Pero, as part of their usual routine, throws him inside a train wagon full of corn so that he can eat. Because of the loud diegetic orchestra music, the rooster probably cannot hear the sound of Pero’s whistle and so does not fly out of the corn wagon. The train departs with him on board, to Pero’s great sorrow. Since it is made known during the film that roosters are forbidden on trains, the fact that the retired, disciplined railwayman, who has dedicated his whole life to the railway, is keeping a rooster and letting him on board a train could be read as an act of defiance.

When the lost rooster seemingly reappears on top of a passing train, it signals that Pero’s hour has come. The shots of the rooster are intercut with close-ups of Pero, who starts smiling because he has seen, or imagined seeing, his lost rooster. A parallel can be drawn to the chthonic meaning of roosters in Magna Graecia, where they appeared on funerary reliefs and votive tablets to signify the soul of the departed.59 In the last shot of the scene in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY, the rooster on top of the passing train gradually becomes smaller and more distant as the train moves away. The camera then tilts up from the train and the rooster to the smoke billowing up from the locomotive and the sky above. This shot then cross-dissolves to a different sky. The view tilts down to a wooden cross and we realise we are in a new scene: Pero’s funeral. The camera follows the moving cross leftwards. Written on the cross are the words ‘Here lies the body of the late Pero Mrgud’60 and Pero’s years of birth and death. It is being carried by Mungo, who plants it upright in the ground. Only a handful of family members and workmates are present at the funeral.

Pero’s death comes just after he, the eldest railwayman of the Brezovi dani station, was awarded a medal for his bravery in preventing train accidents on three separate occasions and so saving the trains and their passengers. Ironically, the award ceremony takes place at the party organised to mark the official closure of the narrow-gauge railway. At Pero’s funeral, his fellow railway worker Srećko Zec61 (Zijah Sokolović) says, ‘Dear Pero, destiny wanted you, and maybe you also wanted it, to depart at the same time as the last Ćiro.62 It can therefore be inferred that Pero’s death symbolises the ‘death’ of the narrow-gauge train model nicknamed ‘Ćiro’ and the narrow-gauge railway in general.

At the funeral, Pero’s grandson, who is named Pero after him, hangs his slingshot on the wooden cross of his grandfather’s grave and places a toy rooster on the mound. However, in the next scene, which comes after an ellipsis, it is shown that life prevails despite Pero’s transition to death. His younger grandson Markan, who has grown up a bit in the meantime, now has a young rooster, who jumps into his arms when he blows a whistle – just like his late grandfather’s rooster used to do.

Another animal in Ljubić’s films that is linked to a person’s transition to the afterlife is a dog in DEFIANT DELTA. One small boy from the village, named Jureta, has a puppy who never leaves his side. He is always shown carrying it. He cares for it when the flood starts by putting the puppy inside the house to keep it safe. When the flood worsens and the villagers have to evacuate on wooden boats, Jureta, who is being carried by his father Marijančić (Ante Vican) to one of the boats, holds the dog in his arms in a wooden basket. There are many people in the boat. When the boat arrives near Ivana’s house, Marijančić puts the boy on the bow of the boat, in order to free a space for Ivana. While Marijančić is fetching Ivana, the wooden basket with the dog rolls over and falls off the boat’s bow into the water. Jureta tries to grab the basket, but it keeps floating away. Then he gets out of the boat and descends into the muddy water, trying to reach for the basket with his little hands. His father brings Ivana on board and the boat leaves, without anyone noticing that Jureta is missing. The boy is shown in a medium shot, the water up to his waist, following the basket, which keeps floating out of his reach. Close-up shots of his father rowing away, unaware of Jureta’s predicament, are cross-cut with medium close-ups of the boy crying and calling for his father.

Later, when the family has already reached safety and Marijančić talks about his plans for his children, including sending Jureta to his relatives in the USA, he realises that Jureta is missing. The villagers start calling for the boy, and then set out on the boats again, repeatedly calling his name. However, Jureta does not respond. Only the sounds of frogs and an adult dog barking in the distance can be heard. At some point, a puppy starts wailing. Then the puppy is shown, wet but alive, having found sanctuary in some tree branches that were not submerged under the water. The shot of the wailing puppy is followed by a shot of a whirlpool and then a close-up of Marijančić (Figure 7a,b,c), who comes to the painful realisation that his son has drowned in the whirlpool. He starts crying while the puppy continues to wail, and takes off his cap to wipe the tears from his eyes.

In Greek and Roman mythology, the three-headed watchdog Cerberus both admits newly deceased souls into the underworld and prevents any souls from leaving it.63 Although the puppy from the film is far from the three-headed mythological monster, there is definitely a correlation between the transition of the boy from life to death in the presence of a dog and Graeco-Roman mythology, as in other implicit references to Greek and Roman myths in the film. Incidentally, the score composed by Vangelis is entitled Entends-tu les chiens aboyer?,64 and also known as Can you hear the dogs barking? and Ignacio. It recurs throughout the film, such as when it is heard at the very end of the film, in the sequence of Ivana’s death.

Another reference to Greek and Roman mythology in DEFIANT DELTA comes in the form of poppies. Poppies are frequently associated with the Greek goddess Demeter or her Roman counterpart Ceres, and symbolise her various aspects.65 On the one hand, poppies’ numerous seeds stand for the fertility of crops, soil and vegetation,66 which Demeter presides over and makes bountiful during the seasons of the year when her daughter Persephone (or Proserpina in Roman mythology) is with her in the world of the living, meaning she is happy and content.67 But on the other, as the source of the narcotic opium, poppies can also signify sleep and hence death (eternal sleep).68 This corresponds to the liminal aspect of Demeter,69 who spends the other seasons of each year, when Persephone is in the underworld with its god, Hades, in mourning.70 While mourning, Demeter neglects to assist with crops and vegetation, causing nature to fall dormant and leading to famine or even death among humans.71 Notably, poppies were also used in ancient times as offerings to the deceased.72 So the presence of poppies in DEFIANT DELTA creates a sensation of in-betweenness, of being poised between the worlds of the living and the dead.

Poppies appear in two scenes of the film, which both deal with the theme of death. In one scene, death is a topic of conversation. A newcomer, nicknamed ‘Antiša from the sea’73 (Ivan Klemenc) by the villagers, is unaccustomed to physical labour and struggles to hoe the soil with the same ease and skill as the villagers. During the lunch break, he performs mime acts for the villagers, and afterwards starts playing an old-fashioned instrumental tune on what appears to be a Baroque guitar. Drawing on the concept of ‘sonic icons’, which Pauleit describes as ‘specific moments within films which forge and maintain connections to history beyond the context of the works themselves’,74 I interpret the music played on the Baroque guitar as an allusion to the Republic of Venice’s past political interferences with and cultural influences on Herzegovina.

Hearing this instrument for the first time, the villagers are so impressed that they pause their work, stop digging and stand in awe. This is shown in a long shot, while Antiša’s performance is shown in close-up. Afterwards, we see a close-up of Ivana, who is sitting next to him, wearing a white headscarf and listening to his music attentively. There is a visual cut to a long, slow pan from left to right over a field of red poppies, while the instrumental guitar music acts as a sound bridge between the two shots and continues to play. Then one of the villagers, Božina (Boro Begović), who is framed in a medium shot in the foreground, with two other villagers in the background, says to Antiša that he should not do any more work but just play guitar. As Božina speaks, the music stops. The other villager, Jozina, who is shown in a medium shot, takes off his hat as a sign of respect and says that Antiša must play the tune he just played at his funeral. Over a close-up of Antiša, we hear Božina reply from off-screen that this is not a song to bury the dead to. Antiša jokingly responds to the villagers that they seem to be talking as if they will all start dying tomorrow. A woman named Mara (Jadranka Matković)75 then approaches him and Ivana. She says she is the only one whose death is near and that he should save the tune that he just performed for her and play something else at other people’s funerals. Marijančić, shown in medium close-up, says that he does not want them to talk about death any more, but that instead Antiša should continue playing, which he does, and the villagers stand and listen in awe. I would argue that the overarching theme of death in this sequence, amplified by the presence of poppies, foreshadows the demise of Ivana. Her close-up, in which she is wearing a white scarf and white blouse, suggesting her goodness and innocence, is immediately followed by the pan across the blood-red poppy field. This editing creates an associative link between Ivana and the red poppies, prefiguring the spilling of her red blood.

Moreover, in the very last scene of the film, before Ivana’s actual demise, the poppies are shown again, thus becoming the leitmotif of death. After Ivana is apprehended by a soldier for trying to steal boxes of military explosives (to make a tunnel to prevent flooding) and is mistaken for an enemy operative by his superior, she is escorted through a red poppy field by two soldiers, to be executed on their superior’s orders. Ivana and two soldiers are depicted in an extreme long shot, as they walk through the field towards the camera. Only the sounds of crickets (and occasionally their approaching footsteps) can be heard. Then, a shot of their legs is shown, as they walk and step on the poppy flowers. This is followed by a shot of numerous red poppies in the field, with the camera tilting upwards. In an extreme long shot featuring a brief zoom-out, we see a vast field with some trees in the background and the two soldiers, who place Ivana in front of a tree trunk in the distance. A voice-over from a disembodied, non-diegetic male voice breaks the silence, yelling ‘People!’ It is the voice of a man with dwarfism, named Šimun,76 who at several points in the film has come running to announce impending doom, such as the arrival of an army. But in the sequence of Ivana’s execution, Šimun the bearer of bad news is not present; only his voice can be heard. This directorial decision adds a menacing tone, implicitly signalling that something bad is about to happen.

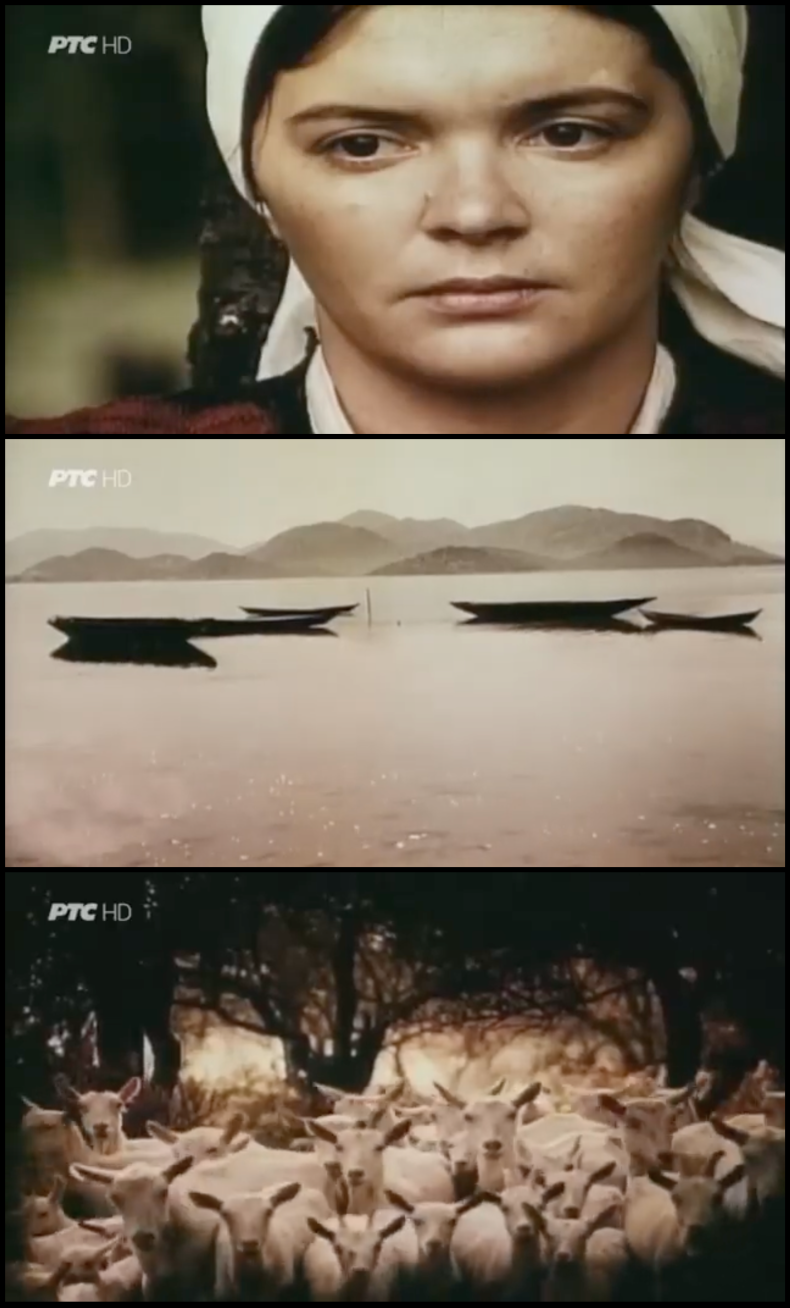

We then see a close-up of Ivana. She wears a white headscarf that suggests her innocence in the face of adversity and a bloody red blouse that foreshadows her execution. Only the sound of crickets can be heard. There is then a cut to an extreme long shot of a mountainous landscape. We hear a non-diegetic male voice singing a cappella a traditional song type known as ganga. The lone lamenting voice wails throughout the mountains, resonating, reverberating, echoing, overlapping and then multiplying as other male voices join in. The lyrics mention barren rocks, and they are accompanied by several shots of barren mountain landscapes, edited with cuts. The last of the five landscape shots is an extreme long shot, similar to the first but a bit less wide, as if slightly zoomed in. There is a visual cut to a big close-up of Ivana (Figure 8a), while the wailing of overlapping male voices continues. Then the wailing stops and Ivana closes her eyes. Again, only crickets can be heard. We see an extreme long shot of the Adriatic Sea, with several empty wooden boats and mountains in the background (Figure 8b), suggesting her memory of a place where she spent a wonderful moment with ‘Antiša from the sea’. Then the reverberating sound of a rifle shot pierces the silence. Ivana’s execution thus takes place off-screen. The instrumental music (Entends-tu les chiens aboyer?) by Vangelis starts, serving as a sound bridge to the next shot, an extreme long shot of a natural landscape with grass, trees and a big herd of white goats roaming around shown in what appears to be slight slow motion. The herd of goats slowly approaches the camera (Figure 8c) and then the screen fades to white, symbolising Ivana’s transition from life to death.

Goats are an important leitmotif associated with Ivana from the beginning of the film. A goat which is her only means of survival is almost taken away from her by foreign soldiers. She is only allowed to keep it because one soldier is physically attracted to her. Later, she must leave her goat behind during the flood and it most likely dies. Moreover, when she and Antiša, whom she likes, are on their way to see the sea for the first time in her life, they encounter a big herd of goats. Ivana is stunned that so many goats exist in the world. She reminisces to Antiša about the times in the past when there was a drought and so the villagers went hungry. Only those with a goat survived. Ivana is thankful to Antiša for bringing her to see this beautiful scene with goats. Consequently, she is no longer afraid of hunger or fever, because ‘as long as there are goats, there will be life’.77 In this sequence from Ivana’s life as well as in the sequence of her death, both of which feature goats, the same instrumental tune (Entends-tu les chiens aboyer?) by Vangelis can be heard, thus creating a parallel between them. To Ivana, goats, as white as her headscarf, signify plenitude, survival, happiness and perhaps a memory of the special moment she spent with Antiša. The last shot of the film therefore suggests that in the afterlife to which Ivana transitions a heavenly herd of goats awaits her.

4. Conclusion

The different kinds of transitions discussed in this chapter reveal the complex nature of the selected films by Vesna Ljubić, DEFIANT DELTA and THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY. For instance, there are historical and political transitions, which include references to the colonial and imperial past, as well as transitions to transcendental states, such as oneirism and death. My analysis of these Yugoslav films, from the perspective of the post-Yugoslav present, has shown that their references to bygone times spark a dialogue between their present and the distant past they are looking back to. However, they not only intertwine their present and past, but also create a new transition to my present, in the form of a cultural memory of Yugoslavia. Close readings of the films, from feminist and postcolonial perspectives, make it possible to explore their artistic aspects and Ljubić’s unique directorial style.

Yugoslav women usually did not consider themselves to be feminists, because they saw feminism as just one more ideology, in this case one from the capitalist West.78 However, I argue that with hindsight we can see how in the analysed films Ljubić either challenges gender stereotypes, as in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY, where a supporting female character, Clara, has agency over her exhibitionism despite being sexually objectified, or places a female character in the lead role, as with Ivana in DEFIANT DELTA. Regardless of whether Ljubić would have considered herself a feminist or not, to quote Rada Šešić she ‘portrays her female characters with depth, nuances, and understanding’.79 Ljubić’s films, their representations of gender roles and her auteur vision therefore stand the test of time.

However, the analogue prints of these films might not withstand the challenges of transition to the post-Yugoslav era that occurred more than three decades ago. The films are mostly forgotten,80 despite being a noteworthy part of Yugoslav cultural heritage. Their copies on film stock are in danger of being lost forever, and so there is an urgent need to digitise and restore them. If the films in question are digitised and subtitled, they can be saved for posterity and screened internationally. Furthermore, Ljubić needs to be (re)inscribed in the history of Yugoslav and European cinema. This article is intended to raise awareness of her remarkable filmography. I hope it will draw the attention of my fellow scholars and increase the prospects of her films being digitised.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank my supervisor Winfried Pauleit (University of Bremen) for his kind help with this article, as well as my co-supervisor Sanja Bahun (University of Essex) and the editors Rasmus Greiner and Tatiana Astafeva. I am also grateful to YUFE4Postdocs and the Hanse-Wissenschaftskolleg Institute for Advanced Study (HWK), with whom I hold postdoctoral fellowships. In addition, I sincerely appreciate the proofreading by Andrew Godfrey-Collins. Finally, my heartfelt thanks go to Aleksandar Erdeljanović (Kinoteka – Yugoslav Film Archive), Ines Tanović and Ema Muftarević (Film Centre Sarajevo), and Devleta Filipović (The Film Archive of Bosnia and Herzegovina), who provided invaluable information on the film archives and digitisation processes.

Funding statement

This work was funded by the European Union, through YUFE4Postdocs – Horizon Europe’s Marie Sklodowska-Curie programme. Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or REA (European Research Executive Agency). Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

- 1

For further information on Sofija ‘Soja’ Jovanović, see Dijana Jelača, ‘Towards Women’s Minor Cinema in Socialist Yugoslavia’, Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies 21, no. 1 (2020).

- 2

Petra Belc, ‘Home Movies and Cinematic Memories: Fixing the Gaze on Vukica Đilas and Tatjana Ivančić’, in Experimental Cinemas in State-Socialist Eastern Europe, ed. Ksenya Gurshtein and Sonja Simonyi (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2022), 156, n. 19.

- 3

Gordana P. Crnković, ‘Farewell My Love: Vesna Ljubić’s Adio kerida (2001)’, Kinoeye: New Perspectives on European Film 3, no. 10 (2003).

- 4

I have so far found two different versions of this film: a longer one, broadcast for example by Radio Television Serbia, and a shorter one, preserved for instance in the archive of the Film Centre Sarajevo, which the archive management kindly allowed me to view. Besides a difference of approximately twenty minutes in length, the plot is presented differently due to different editing and ordering of some scenes. My analysis here refers to the longer version.

- 5

One notable exception is some short films directed by Tatjana Ivančić that were recently restored by the Austrian Film Museum and Light Shop/Digital Magic Studio at the initiative of Petra Belc and Cinéclub Zagreb, with the support of the Croatian State Archives and funding from the Croatian Audiovisual Centre. Another noteworthy example is Sanja Bahun’s initiative to digitise short animated and documentary films by Vera and Ljubiša Jocić, with the support of several institutions. The films were shown at the exhibition ‘Aktivitet: 100 Years of Surrealism’, which Bahun conceived and curated. Finally, I should also note the work by Ines Tanović and the Sarajevo Film Centre to digitise Yugoslav films, especially in the project ‘Preserving BiH Film Heritage for Future Generations’, which was supported by the US Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation. Also, they plan to digitize short films by female filmmakers, such as by Mirjana Zoranović Živković and Vera Crvenčanin.

- 6

Sanja Bahun and V. G. Julie Rajan, ed., Violence and Gender in the Globalized World: The Intimate and the Extimate (Farnham: Ashgate, 2015), 3.

- 7

Dina Iordanova, ‘Women’s Place in Film History: The Importance of Continuity’, Panoptikum 23, no. 30 (2020): 10–15; Dina Iordanova, Cinema of the other Europe: the industry and artistry of East Central European film (London: Wallflower, 2003), 119.

- 8

Ana Grgić, ‘There Is No Such Thing as Balkan Cinema, and Yes, Balkan Cinema Exists: Ruminations on the Past and Possible Futures of Balkan Cinema (and Media) Studies?’, NECSUS 10, no. 2 (2021): 22.

- 9

Gal Kirn, ‘Transnationalism in Reverse: From Yugoslav to Post-Yugoslav Memorial Sites’, in Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales, ed. Chiara De Cesari and Ann Rigney (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014), 314; Nebojša Jovanović, Gender and Sexuality in the Classical Yugoslav Cinema, 1947–1962, doctoral thesis, Central European University, Budapest (2014), 48.

- 10

Rada Šešić, ‘Ljubic, Vesna’, in Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film, ed. Ian Aitken, vol. 2: H–O Index (New York: Routledge, 2006), 808.

- 11

Personal correspondence with Aleksandar Erdeljanović, 9 August 2022.

- 12

Personal correspondence with Ines Tanović and Ema Muftarević, 11 December 2024.

- 13

FCS, ‘Uspješno završen američki projekat digitalizacije “Preserving BiH Film Heritage for Future Generations”’, https://fcs.ba/afcp/.

- 14

Personal correspondence with Devleta Filipović, 21 April 2025.

- 15

Personal correspondence with Ines Tanović and Ema Muftarević, 20 March 2025.

- 16

Personal correspondence with Devleta Filipović, 21 April 2025.

- 17

Personal correspondence with Aleksandar Erdeljanović, 9 August 2022.

- 18

‘Filmski centar Sarajevo’, Sarajevo City of Film, https://sarajevocityoffilm.ba/bs/filmski-centar-sarajevo/

- 19

Milorad Ekmečić, ‘The Failure of Yugoslav-Oriented Policies and the Predominance of Austria in the Balkans’, in History of Yugoslavia, ed. Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić (New York: McGraw Hill, 1974), 396.

- 20

Vladimir Dedijer, ‘The Collapse of Ottoman Rule’, in History of Yugoslavia, ed. Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić (New York: McGraw Hill, 1974), 422.

- 21

Vladimir Dedijer, The Road to Sarajevo (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966), 17.

- 22

Vladimir Dedijer, ‘The New State in International Affairs’, in History of Yugoslavia, ed. Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić (New York: McGraw Hill, 1974), 504.

- 23

Vladimir Dedijer, ‘Yugoslavia between Centralism and Federalism’, in History of Yugoslavia, ed. Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić (New York: McGraw Hill, 1974), 542.

- 24

Robert J. Donia and John V. A. Fine Jr, Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Tradition Betrayed (London: Hurst, 1994), 93.

- 25

Vladimir Dedijer, ‘Part Four: Unification and the Struggle for Social Revolution’, in History of Yugoslavia, ed. Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić (New York: McGraw Hill, 1974), 415.

- 26

Laura Mulvey, Visual and Other Pleasures (Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1989), 20.

- 27

Especially considering that sevdalinka was inscribed in 2024 on the UNESCO list of the intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

- 28

The last name ‘Mrgud’ can be translated as ‘grumpy’.

- 29

The last name ‘Sudar’ can be translated as ‘clash’.

- 30

Japanolija is an invented name, a pun on the words Japan and jambolija – the latter being a traditional woolen cover, which can also be used as a rug. Ljubić satirises Japanolija’s ‘cultured’ stances by giving her this name.

- 31

Winfried Pauleit and Rasmus Greiner, ‘Sonic Icons and Histospheres: On the Political Aesthetics of an Audio History of Film’, in Politics, Civil Society and Participation: Media and Communications in a Transforming Environment,ed. Leif Kramp et al. (Bremen: Edition lumière, 2016), 313.

- 32

Trains appear in several of Fellini’s films, including I VITELLONI (Italy 1953) and 8½ (Italy 1963).

- 33

‘Sevdalinka, Traditional Urban Folk Song’, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/sevdalinka-traditional-urban-folk-song-018….

- 34

Winfried Pauleit, ‘Sonic Icons in A Song Is Born (1948): A Model for an Audio History of Film’, in Music, Media, History: Re-Thinking Musicology in an Age of Digital Media, ed. Matej Santi and Elias Berner (Bielefeld: Transcript, 2021), 152.

- 35

Pauleit, ‘Sonic Icons in A Song is Born’, 155.

- 36

Pauleit, ‘Sonic Icons in A Song is Born’, 155.

- 37

Winfried Pauleit, ‘Sonic Icons: Prominent Moments of Cinematic Self-Reflexivity’, Research in Film and History: New Approaches (2018): 5.

- 38

Pauleit, ‘Sonic Icons in A Song is Born’, 155.

- 39

Pam Cook, ed., The Cinema Book (London: BFI, 2007), 488; Freya Schiwy, Indianizing Film: Decolonization, the Andes, and the Question of Technology (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009), 112.

- 40

Kalpana Ram, ‘Gender, Colonialism, and the Colonial Gaze’, in The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology, ed. Hilary Callan (Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2018), 2465.

- 41

E. Ann Kaplan, Looking for the Other: Feminism, Film, and the Imperial Gaze (New York: Routledge, 1997), 78.

- 42

Schiwy, Indianizing Film, 112.

- 43

Shohat refers to Western cinema in general, but most of the examples of the films she gives are from mainstream US and British cinema.

- 44

Ella Shohat, ‘Gender and Culture of Empire: Toward a Feminist Ethnography of the Cinema’, Quarterly Review of Film and Video 13, no. 1–3 (1991): 45.

- 45

Maria Todorova, Imagining the Balkans (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), 3.

- 46

Schiwy, Indianizing Film, 113.

- 47

Ivan Lozica, ‘Poklade u zborniku za narodni život i običaje Južnih Slavena i suvremeni karneval u Hrvatskoj’, Narodna umjetnost 23 (1986): 44.

- 48

Mulvey, Visual and Other Pleasures, 19.

- 49

Ram, ‘Gender, Colonialism, and the Colonial Gaze’, 2465.

- 50

Brigitte Peucker, The Material Image: Art and the Real in Film (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007), 76.

- 51

‘Neka ne gledaju, ako im nije volja’ (original dialogue in Serbo-Croatian).

- 52

Vesi Vuković, ‘Yugoslav(i)a on the Margin: Sexual Taboos, Representation, Nation and Emancipation in Želimir Žilnik’s EARLY WORKS (1969)’, Studies in Eastern European Cinema 13, no. 3 (2022): 251; Vesi Vuković, ‘Violated Sex: Rape, Nation and Representation of Female Characters in Yugoslav New Film and Black Wave Cinema’, Studies in Eastern European Cinema 9, no. 2 (2018): 136.

- 53

‘Charon’, Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Charon-Greek-mythology.

- 54

Šešić, ‘Ljubic, Vesna’, 807.

- 55

Rasmus Greiner, Cinematic Histospheres: On the Theory and Practice of Historical Films (Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021), 186.

- 56

Greiner, Cinematic Histospheres, 118.

- 57

Siegfried Kracauer, Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997), 305.

- 58

Greiner, Cinematic Histospheres, 118.

- 59

Augusto Cosentino, ‘Persephone’s Cockerel’, in Animals in Greek and Roman Religion and Myth, ed. Patricia A. Johnston, Attilio Mastrocinque and Sophia Papaioannou (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2016), 192.

- 60

‘Ovdje počiva tijelo pokojnog Pere Mrguda’ (original text in Serbo-Croatian).

- 61

His first name, ‘Srećko’, can be translated as ‘happy’ or ‘lucky’ and his last name, ‘Zec’, as ‘rabbit’.

- 62

‘Dragi Pero, sudbina je tako htjela, a možda si ti tako htio da odeš sa posljednjim “Ćirom”’ (original dialogue in Serbo-Croatian).

- 63

Josepha Sherman, ed., Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore (London: Routledge, 2015), 87.

- 64

Initially heard in the film DO YOU HEAR THE DOGS BARKING? (¿No oyes ladrar los perros?; Mexico 1975; dir. François Reichenbach).

- 65

Barbette Stanley Spaeth, The Roman Goddess Ceres (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996), 128.

- 66

Spaeth, The Roman Goddess Ceres, 128.

- 67

Michael Jordan, Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses (New York: Facts on File, 2004), 73.

- 68

Spaeth, The Roman Goddess Ceres, 128.

- 69

Spaeth, The Roman Goddess Ceres, 128.

- 70

Jordan, Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses, 73.

- 71

Jordan, Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses, 73.

- 72

Farrin Chwalkowski, Symbols in Arts, Religion and Culture: The Sound of Nature (Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2016), 267.

- 73

‘Antiša sa mora’ (original nickname in Serbo-Croatian).

- 74

Winfried Pauleit, ‘Sonic Icons: Prominent Moments’, 5.

- 75

The same actress plays the character of Japanolija in THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY.

- 76

Unfortunately, I could not identify the name of the actor.

- 77

In Serbo-Croatian: ‘Dok je koza, biće života’.

- 78

Anikó Imre, ‘Gender, Socialism, and European Film Cultures’, in The Routledge Companion to Cinema and Gender, ed. Kristin Lené Hole, Dijana Jelača, E. Ann Kaplan and Patrice Petro (Abingdon: Routledge, 2017), 89.

- 79

Šešić, ‘Ljubic, Vesna’. 807.

- 80

There are some praiseworthy exceptions, such as the screening of THE LAST SWITCHMAN OF THE NARROW-GAUGE RAILWAY in the ‘Icebreakers’ programme, curated by Diana Nenadić, at the nineteenth Zagreb Film Festival in 2021.

Bahun, Sanja, and V. G. Julie Rajan, eds. Violence and Gender in the Globalized World: The Intimate and the Extimate. Farnham: Ashgate, 2015.

Belc, Petra. “Home Movies and Cinematic Memories: Fixing the Gaze on Vukica Đilas and Tatjana Ivančić.” In Experimental Cinemas in State-Socialist Eastern Europe, edited by Ksenya Gurshtein and Sonja Simonyi. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2022.

“Charon,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed November 11, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Charon-Greek-mythology

Chwalkowski, Farrin. Symbols in Arts, Religion and Culture: The Sound of Nature. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2016.

Cook, Pam, ed. The Cinema Book. London: BFI, 2007.

Cosentino, Augusto. “Persephone’s Cockerel.” In Animals in Greek and Roman Religion and Myth, edited by Patricia A. Johnston, Attilio Mastrocinque and Sophia Papaioannou. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars, 2016.

Crnković, Gordana P. “Farewell My Love: Vesna Ljubić’s Adio kerida (2001)”, Kinoeye: New Perspectives on European Film 3, no. 10 (2003). http://www.kinoeye.org/03/10/crnkovic10.php ISSN : 1475-2441

Dedijer, Vladimir. “Part Four: Unification and the Struggle for Social Revolution.” In History of Yugoslavia, edited by Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić. New York: McGraw Hill, 1974.

Dedijer, Vladimir. “The Collapse of Ottoman Rule.” In History of Yugoslavia, edited by Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić. New York: McGraw Hill, 1974.

Dedijer, Vladimir. “The New State in International Affairs.” In History of Yugoslavia, edited by Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić. New York: McGraw Hill, 1974.

Dedijer, Vladimir. The Road to Sarajevo. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1966.

Dedijer, Vladimir. “Yugoslavia between Centralism and Federalism.” In History of Yugoslavia, edited by Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić. New York: McGraw Hill, 1974.

Donia, Robert J. and John V. A. Fine Jr. Bosnia and Herzegovina: A Tradition Betrayed. London: Hurst, 1994.

E. Ann Kaplan, Looking for the Other: Feminism, Film, and the Imperial Gaze (New York: Routledge, 1997), 78.

Ekmečić, Milorad. “The Failure of Yugoslav-Oriented Policies and the Predominance of Austria in the Balkans.” In History of Yugoslavia, edited by Vladimir Dedijer, Ivan Božić, Sima Ćirković and Milorad Ekmečić. New York: McGraw Hill, 1974.

Greiner, Rasmus. Cinematic Histospheres: On the Theory and Practice of Historical Films. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

Grgić, Ana. “There Is No Such Thing as Balkan Cinema, and Yes, Balkan Cinema Exists: Ruminations on the Past and Possible Futures of Balkan Cinema (and Media) Studies?.” NECSUS 10, no. 2 (2021): 19-26. http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/17285

Jelača, Dijana. “Towards Women’s Minor Cinema in Socialist Yugoslavia.” Wagadu: A Journal of Transnational Women’s and Gender Studies 21, no. 1 (Fall 2020). https://wagadu.org/v21-towards-womens-minor-cinema-in-socialist-yugoslavia/ ISSN : 1545-6196

Imre, Anikó. “Gender, Socialism, and European Film Cultures.” In The Routledge Companion to Cinema and Gender, edited by Kristin Lené Hole, Dijana Jelača, E. Ann Kaplan and Patrice Petro. Abingdon: Routledge, 2017.

Iordanova, Dina. “Women’s Place in Film History: The Importance of Continuity.” Panoptikum 23, no. 30 (2020): 10–15. https://doi.org/10.26881/pan.2020.23.01

Iordanova, Dina. Cinema of the other Europe: the industry and artistry of East Central European film. London: Wallflower, 2003.

Jordan, Michael. Dictionary of Gods and Goddesses. New York: Facts on File, 2004.

Jovanović, Nebojša. “Gender and Sexuality in the Classical Yugoslav Cinema, 1947–1962.” PhD diss., Budapest: Central European University, 2014.

Kirn, Gal. “Transnationalism in Reverse: From Yugoslav to Post-Yugoslav Memorial Sites.” In Transnational Memory: Circulation, Articulation, Scales, edited by Chiara De Cesari and Ann Rigney. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2014.

Kracauer, Siegfried. Theory of Film: The Redemption of Physical Reality. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1997.

Lozica, Ivan. “Poklade u zborniku za narodni život i običaje Južnih Slavena i suvremeni karneval u Hrvatskoj.” Narodna umjetnost 23 (1986): 31-56. https://hrcak.srce.hr/49888

Mulvey, Laura. Visual and Other Pleasures. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 1989.

Pauleit, Winfried. “Sonic Icons in A Song Is Born (1948): A Model for an Audio History of Film.” In Music, Media, History: Re-Thinking Musicology in an Age of Digital Media, edited by Matej Santi and Elias Berner, Bielefeld: Transcript, 2021.

Pauleit, Winfried. “Sonic Icons: Prominent Moments of Cinematic Self-Reflexivity.” Research in Film and History. New Approaches (2018): 1-45. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14812.

Pauleit, Winfried and Rasmus Greiner. “Sonic Icons and Histospheres: On the Political Aesthetics of an Audio History of Film.” In Politics, Civil Society and Participation: Media and Communications in a Transforming Environment, edited by Leif Kramp et al. Bremen: Edition lumière, 2016.

Peucker, Brigitte. The Material Image: Art and the Real in Film. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2007.

Ram, Kalpana. “Gender, Colonialism, and the Colonial Gaze.” In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Hilary Callan. Hoboken: Wiley Blackwell, 2018.

Sherman, Josepha, ed. Storytelling: An Encyclopedia of Mythology and Folklore. London: Routledge, 2015.

Schiwy, Freya. Indianizing Film: Decolonization, the Andes, and the Question of Technology. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2009.

“Sevdalinka, Traditional Urban Folk Song,” UNESCO, accessed November 12, 2024, https://ich.unesco.org/en/RL/sevdalinka-traditional-urban-folk-song-01872

Shohat, Ella. “Gender and Culture of Empire: Toward a Feminist Ethnography of the Cinema.” Quarterly Review of Film and Video 13, no. 1–3 (1991): 45-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10509209109361370

Spaeth, Barbette Stanley. The Roman Goddess Ceres. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1996.

Šešić, Rada “Ljubic, Vesna.” In Encyclopedia of the Documentary Film, edited by Ian Aitken, vol. 2: H–O Index. New York: Routledge, 2006.

Todorova, Maria. Imagining the Balkans. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

“Uspješno završen američki projekat digitalizacije ‘Preserving BiH Film Heritage for Future Generations’,” FCS, accessed November 10, 2024, https://fcs.ba/afcp/

Vuković, Vesi. “Yugoslav(i)a on the Margin: Sexual Taboos, Representation, Nation and Emancipation in Želimir Žilnik’s Early Works (1969).” Studies in Eastern European Cinema 13, no. 3 (2022): 248-271. https://doi.org/10.1080/2040350X.2021.1994758

Vuković, Vesi. “Violated Sex: Rape, Nation and Representation of Female Characters in Yugoslav New Film and Black Wave Cinema.” Studies in Eastern European Cinema 9, no. 2 (2018): 132-147. https://doi.org/10.1080/2040350X.2018.1435204