Sonic Histospheres

Sound Design and History

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Greiner, Rasmus: Sonic Histospheres: Sound Design and History. In: Research in Film and History. New Approaches (2018), pp. 1–34. DOI: https://doi.org/10.26092/elib/101.

1. Film Sound and Experiencing History

This chapter explores the role played by film sound in the audio-visual construction of historical dimensions of experience. This exploration does not treat the auditory level in isolation, but considers how it interacts with moving images, montages and aesthetic and narrative concepts within the ‚audio-visual histosphere‘.1 The term “histosphere” refers here to a space–time structure constructed by film that models a historical world and opens it up to audio-visual experience. In the histosphere, spectators’ perceptions oscillate between a supposedly objective external view and the subjective experiences of the film characters.

Underpinning this chapter is a conception of how film experience enables historical experience that draws on Vivian Sobchack’s work on the phenomenology of film.2 Sobchack understands the experience of film as an embodied process that addresses the synaesthetic structure of our perceptual apparatus. In her theory, films make palpable the experience of history not simply by means of intensely affective images, but also by synaesthetically combining the visual and auditory levels. Film sound plays a special role in this process. It structures the cinematic narration of history by creating continuities and breaks, connections, conjunctions and oppositions. The auditory level is also crucial in determining the mood of film sequences, and elicits emotional reactions to historical processes, events and situations.3 In order to emphasise the importance of sound in this context, I introduce the notion of a ‚sonic histosphere‘.

If soundtracks are analysed according to the approach I have sketched above, the great importance of sound design will become apparent. In the 1970s, a revolution began in American film production that film historians later termed “New Hollywood”. New Hollywood brought with it aesthetic, technical and creative innovations, and these innovations changed film sound too.4 Inspired by European avant-garde movements such as the French New Wave, a new generation of filmmakers (including George Lucas, Francis Ford Coppola, Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese) elevated the status of sound design. They shared an enthusiasm for the contemporary music industry’s “electronically modified sounds that blurred the boundary between noise and music”5 and attempted to “develop a similar vocabulary for film soundtracks”.6 The profession of sound designer was born. Sound design was pivotal in turning film sound into an autonomous dimension of expression with a status equal to images, by organising the production of auditory signs and increasing their scope for expression and complexity.

There are three dimensions to the relationship between sound design and history that can be studied in connection with the auditory construction of the histosphere: the auditory modelling of history, the auditory experiencing of history and the auditory reflection on history through film sound. In this chapter, I take a heuristic approach to theory formation in which I focus on each of these three interwoven aspects in turn, though without ever losing sight of the other two. Firstly, by reference to Tom Hooper’s THE KING’S SPEECH (UK/USA/AUS 2010) I investigate the auditory modelling of history, with a focus on the relationship between sound design and filmic/historical space, filmic/historical time and film characters/historical figures. Secondly, by analysing Francis Ford Coppola’s APOCALYPSE NOW (USA 1979) I explore auditory experiences of trauma and painful history. In this context, I connect sound design to forms of remembering and imagination and to ‚embodied experiences of history‘, and examine sound design’s function as the emotional texture of history in closer detail. Finally, I analyse Ari Folman’s animated film WALTZ WITH BASHIR (ISR/F/D/USA/FIN/CHE/BEL/AUS 2008) as an example of auditory reflection on the relationship between traumatic experiences, memory and history. This analysis also explores how the ‚sonic histosphere‘ relates to reflective mediatisation of historiography. However, before turning to these films, in the next section I begin by tracing the ways in which sound design relates to prefilmic reality and to conceptions of history.

2. Constructions of Reality and History

If we hear something, we take it to be real. This intuitive auditory comprehension gives film sound an instant credibility.7 Although the relationship between film images and reality has come under scrutiny since the start of the digital revolution, if not before, indexical traces of a prefilmic reality are still ascribed to film sound. Rick Altman regards this as a fundamental fallacy, and maintains that our understanding of sound moved on from this era of indexicality far earlier than our understanding of film images.8 According to Altman, film sound is not reproduction but representation, that is to say an interpretation of the original sound contingent on physical, technical and aesthetic factors.9 Altman’s view is at odds with norms and conventions that encourage spectators to place unquestioned faith in film sounds: “In order to assess the truth of a sound, we refer much more to codes established by cinema itself, by television, and narrative-representational arts in general, than to our hypothetical lived experience.”10 Although spectators draw on their auditory memory, this memory itself can often be composed of sounds remembered from films. For most people in post-industrial societies, hearing sounds transmitted through media is an everyday experience. These media sound experiences create new hierarchies of memory11 and can even displace pre-existing memories of sound.

In his discussion of the visual dimension of cinematic historicity, Sven Kramer remarks, “There are always images – mental images – that occur involuntarily and cast themselves over what we are currently looking at. Or, to put it another way: the images that we see are constantly augmented by images that we do not see. In this way, the images we are currently viewing are always modified by the visual discourse and visual memory of a collective. The discourse speaks constantly into the reading.”12 Very similar interrelations can be observed in film sound in historical films.13 Sound design engages with and responds to these interrelations. Hence, what is intuitively perceived as the authentic sound of history turns out to be modelled by cinema. A parallel can be drawn here with the ‚politics of representation‘ in photography theory: the “mainly unconscious ideological and mental structures” through which “photographs constitute the reality and identities that they purport to be re-presenting.”14 My thesis is that film sound creates and constructs historical identities and realities in a very similar manner. In her theoretical reflections on film and history, Gertrud Koch suggests that spectators actually prefer cinematic conventions to faithful accounts of how events really happened:

One might think that it is precisely the concretist character of the sets, the artificiality [‚Kulissenhafte‘] of the painted and sawn scenery, that constantly signals to spectators that this is an invented story. But the opposite appears to be the case: the more symbolic and self-contained [‚geschlossen‘] the aesthetic cosmos of signs that envelop the spectators, the more readily they will succumb to the myth.15

Sound design shapes, organises and structures the auditory elements of this aesthetic cosmos, which in relation to historical films I earlier termed the ‚sonic histosphere‘.

If sound design does not intervene in filmic reality, it can confuse spectators, as Randolph Jordan noted in his discussion of the Naudet brothers’ footage of the first plane hitting the World Trade Center.16 Because the camera team were too far away from the site of the impact, the sound of the crash is not simultaneous with the images of the exploding aircraft, and is only heard a few moments later. This physically accurate representation diverges completely from the Hollywood norm, where image and sound are synchronised. Béla Balázs had already noted back in the early 1930s that

this is one case in which our natural mode of perception contradicts our imagined reality […] And for the most part the sound film will have to adjust itself to our imagination rather than to nature. For what matters here is not objective factual reality, but only the specific, immanent spiritual reality of the work of art. What matters is illusion. And illusion is for the most part only disrupted by the exact reproduction of nature.17

If sound has been modified by sound design, this will usually be concealed from spectators unless their attention is specifically drawn to the film’s acoustic qualities. Just like with invisible image editing, they accept the artificial construction and modelling of the represented object as valid reality, and actually prefer it to more realistic representations. The instant credibility of sound even colours images; Jean-Louis Comolli argues that “combined with the visual deception, the sound (edited or unedited), carries a reminder of reality, if I may say, which first and foremost serves to validate the illusion — as striking and yet as fragile as it is — precisely by asserting its status as a mere impression of reality”.18 These remarks echo Friedrich Kittler’s notion of the “noise of reality” (‚Rauschen des Realen‘): according to Kittler, it is not just the meaningful, signifying elements that make their way into the material but everything else too, even things generally considered “interference”, since analogue media do not distinguish between voices, linguistic codes and noises. They transform the intentional and the accidental alike, and code it as co-present noise.19 The seeming authenticity of such noise can aid film in constructing and modelling history through sound and images. If sound design mimics these kinds of unintentionally recorded traces of prefilmic reality, or simulates technical interference and technological deficiencies, this will not only facilitate the audio-visual representation of history, but will also help to make this representation credible.

3. Auditory Modelling of History: THE KING’S SPEECH

This section investigates the auditory strategies and devices with which historical films model history. The concept of modelling is drawn from Horst Bredekamp’s discussion of the “driving force of form”20 (‚Triebkraft der Form‘) and is understood as an expression of aesthetics. If space, time and subject – in short, filmic reality – are generated through a film’s audio-visual design, then the conceptions of history evoked by films can also be traced back to aesthetically motivated editing of moving images and sounds. To put it another way: cinema’s aesthetic strategies of ‚temporalising space and spatialising time‘21 generate a reality that models history. We can speak here not just of a ‚mise-en-image‘ but also of a ‚mise-en-son‘: the soundtrack helps to create an audio-visual space – a quasi-historical22 world – in order to fulfil dramaturgical requirements. The film’s narrative localises the characters in this audio-visual construction;23 they themselves become part of history and are ascribed their own historical consciousness. Hence, the concept of modelling has a double meaning: firstly, the audio-visual moulding of a filmic space–time structure; secondly, a model representation of history.Below, I shall attempt to show how film sound helps to construct conceptions of historical spaces and times, and how it situates characters within them. I focus on the auditory modelling of a historical world and the effects of this modelling on popular conceptions of history. My analysis takes the film THE KING’S SPEECH24 as an example. It complements Winfried Pauleit’s chapter by concentrating less on points relating to (media) history and more on this process of audio-visual world-building.

Space

Hearing is a spatial sense. It helps us to orient ourselves in space and provides information about the nature of the space we find ourselves in. “Through the ears, we are in constant dialogue with the space that surrounds us”,25 according to Barbara Flückiger. This gives film sound the potential to create spaces independently of images and to invest them with meaning. However, this potential was long neglected. Sound only began to be emancipated from image in the late 1950s. This shift also involved a changing relationship to space, as Henry M. Taylor observes: “Sound starts to become detached from the spatial definition of the image, and even to question and threaten it”.26 Furthermore, film sound was soon also capable of producing an expanded filmic space. But whereas in nature it is possible to clearly distinguish between pulses of sound and the resonance of a space, in sound recording this distinction collapses.27 So in order to use auditory devices to model filmic spaces and make them palpable to the senses, the fundamental physical features of real-world sound spaces must be artificially simulated. Long ago, Balázs drew attention to the fact that through having a certain “timbre”, sound conveys the impression of being located in the space of the represented events.28 The view I am arguing for here is that historical worlds can also be simulated in this way. Doing so requires an artistic modelling of historical sound spaces, which can be accomplished by sound design. The spatial coordinates of sound design can also have a metaphorical significance, as Balázs illustrates by reference to the examples of ‚silence‘ and ‚noise‘: “Silence occurs when what I hear is distance. And the space that falls within the range of my hearing becomes my own, a space that belongs to me. Where there is noise, in contrast, I feel surrounded by walls of sound, a prison cell of noise.”29 The sound design of a space can also significantly influence readings of history by infusing the representation of historical figures, events and circumstances with a particular atmosphere.

Noises in particular possess great evocative power, which is a more important determinant of film’s capacity to influence conceptions of history than how closely these noises resemble the historical sounds and tones they purport to represent. Accordingly, auditory world-building is based primarily on the use of noises that stir the spectators’ emotions. In addition, noises can function as auditory metaphors that have a significant impact on film’s representation and interpretation of history.30 In the opening sequence to THE KING’S SPEECH, Albert (Colin Firth) is supposed to give a speech at the closing of the British Empire Exhibition in Wembley Stadium as a representative of the Royal Family. His attempt to speak is thwarted by high-pitched interference from the microphone, which causes Albert to descend into scarcely comprehensible stammering. The impression of vulnerability and exposure in a vast space is further reinforced by the use of strong reverberation.

In this way, the sound design contributes to the representation of the historical figure and contemporary perceptions of him. The faraway whinnying of a horse gives added emphasis to the unpleasant silence, which (following cinematic conventions) is expressed not through the absence of sound but through a reduced but still present ambience.31 Ambience serves a dual function. On the one hand, it characterises the location or space, and on the other it simultaneously infuses this location or space with an atmosphere that can affect spectators emotionally. This is all the more effective because the ambience is registered prereflectively and is hence “felt”32 rather than critically questioned. In the context of the ‚sonic histosphere‘, ambience thus assumes a mediating function between the representation and perception of a filmic space.

Ambience also has the potential to link history to the physical space in which it is represented in film. This can be observed in THE KING’S SPEECH too. In another sequence, Albert enters a private room in his palace where his wife (Helena Bonham Carter) and two young daughters are waiting for him. He tells the children a bedtime story. The ambience is characterised primarily by the steady blazing and crackling of the fire in the hearth. The soothing effect of this background noise characterises the private room as a place of refuge. This models not only the specific filmic location where the characters find themselves, but also the relationship between the characters. The film thus offers a historical reconstruction of the everyday reality and interpersonal relations of a member of the Royal Family in the 1920s, and presents this intimate sphere, by way of contrast with public life, as a space of safety and security.

The atmosphere of a space is determined not just by the ambience but also by the material qualities that the sound captures.33 What noises occur in a space? And what do they sound like? Enriching the soundtrack with material details gives substance back to the objects formed of light and shadow that are depicted in film images. According to Flückiger, this compensates for the absence of tactile sensation34 and makes the unfamiliar worlds constructed by film more credible.35 The “materializing sound indices”36 give the impression that you could reach out and touch the audio-visually modelled historical world. At the same time, films are measured against what the spectators expect particular historical locations and situations to sound like. The room in the sequence from THE KING’S SPEECH described above has almost no reverberation, so it does not seem excessively large. A faint hum when the characters speak suggests wood-panelled walls or textured wallpaper. The sound of Albert’s steps is muted, indicating thick carpets, while a light clumping sound suggests that there are wooden floorboards underneath. In this case, the materialising sound indices reinforce the impression of warmth and security already evoked by the ambience. The sound thus makes tangible the historical world constructed by the film and infuses it with a mood that is also reflected at the visual level, especially in the warm yellow lighting.

‚Orienting sounds‘ also contribute to auditory construction of cinematic space. According to Flückiger, orienting sounds are sound objects that are recognisable and significant for people from a particular community and a particular time: “The term ‘orienting sound’ does not refer to a specific sound object in itself, but to its function of defining a place in geographical, temporal, cultural, ethical or social terms.”37 All these aspects are significant in orienting spectators within the space–time structure of a cinematically modelled historical world. One example of an orienting sound used repeatedly in THE KING’S SPEECH is the sound of horse-drawn carriages on paved streets. This, firstly, localises the film in an urban space and, secondly, pins it down to an approximate point in time, particularly when the sound of carriages is combined with the sounds of contemporaneous motorcars. I explore the importance of orienting sounds for modelling historical time in greater detail further below.

The combination of orienting sounds with the ambience, materialising sound indices and other sound objects (some of which cannot be identified) expands the possibilities for auditorily modelling a historical world. Frieder Butzmann and Jean Martin correctly point out that without the careful selection and montage of sound objects, film would end up as a “sublime orgy of noise”.38 Hence, strong tendencies to codify film sound can be observed, especially in American mainstream cinema.39 These tendencies also affect the auditory modelling of history, with the result that cinematic representations of scenes set in the streets of London in the 1920s (like in THE KING’S SPEECH) can sound identical to cinematic representations of similar settings in New York. It is only through being combined with film images or iconic sounds such as the chiming of Big Ben that the scenes can be assigned to a specific place.

At the same time, the sound design of the historical world contains a subtle layer of political meaning. Whereas Albert’s palace in THE KING’S SPEECH is almost hermetically sealed off from the outside world, sounds from the street are able to permeate into the home of the speech therapist Lionel Logue (Geoffrey Rush). In combination with the clinking of dishes and the creaking of bare floorboards, the clattering of horse-drawn carriages and the voices of passers-by not only allude to Logue’s more modest middle-class circumstances but also suggest a certain openness to the world that the upper classes in THE KING’S SPEECH lack (at least initially). However, spectators’ perceptions are also affected by the characters and their behaviour. The exuberance in Lionel’s home is juxtaposed with the somewhat calmer – but no less affectionate – scenes in Albert’s household. Hence, film sound also functions as an expression of different social classes and the conditions in which they live. This is another strand of the way in which the film models history.

Time

Film sound cannot be divorced from the progression of time. While a still image will resemble the sequence of moving images from which it is taken, film sound cannot be held still without causing it to disappear completely. At the same time, it regulates the temporality of the images by necessitating a certain projection speed and linearisation.40 Erwin Panofsky describes how visual montages temporalise filmic space through switches of perspectives.41 Building on the discussion in the previous section about the auditory construction of filmic spaces, it is possible to expand Panofsky’s idea to include audio and audio-visual montages too, in which moving images and sound blend into an audio-visual space–time structure: namely, the histosphere, which spectators in turn perceive and interpret over a stretch of time.

Film sound enables spectators to travel through not just space but also time and to immerse themselves in the bygone era constructed by film. The ‚sonic histosphere‘ is anchored in a particular historical period through orienting sounds and complex soundscapes. Historical films also create a specific chronology through their temporal arrangement of the historical events that they depict. In this process, film sound often serves an amalgamating function, linking filmic spaces together and establishing continuity. One example of this can be seen in the final radio broadcast at the end of THE KING’S SPEECH, where Albert speaks live to the people of Britain. Shots of Albert speaking in the recording booth are intercut with images of people throughout the country listening to him raptly, creating a public that film spectators can also be a part of. Colin Firth’s voice runs through the montage and links the shots together.

By repeating the live experience, the film makes the past immediately present. At the same time, by linking together shots of the king with images showing a cross section of the British people, the sound forms a community, an experience of collective memory. History is re-enacted as a media event. The choice of music also reinforces the impression that one is experiencing a moment of great historical significance. Instead of a conventional film score, Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony No. 7 is used.42 Despite being an anachronism, this choice of music taps into a collective cultural memory, to which the film sequence is then linked. Furthermore, it suggests to spectators that they are witnessing the creation of a historical audio document. However, THE KING’S SPEECH does not use the actual historical recording of George VI’s speech, but an audio re-enactment with Colin Firth’s voice. Accordingly, the sequence can be described as a filmic representation of history in the making: the auditory modelling of the king’s voice synchronises space and time, establishing historical continuity.

Moreover, the temporality of the quasi-historical world constructed by the film is highly malleable. For example, the strong reverberation during the speech in Wembley Stadium described above not only creates the perception of a vast filmic space, but also makes time appear to stretch out so that Albert’s ordeal seems endless. Birger Langkjær explains this effect: “Whereas the pictures manipulate time by slowing down visual movements, the sound manipulates time by extending the audio space”.43 Accordingly, the auditory modelling of space is closely linked to spectators’ perception of time, while the film sound’s manipulation of the experience of time in turn directly influences the perception and evaluation of the historical event depicted by the film. In the sequence described earlier, this can be seen in the way that the reverberation effect not only expands the dimensions of the filmic space but also creates the impression of time being stretched out, which (given spectators’ foreknowledge of his unexpected ascension to the throne) increases the historical brisance of Albert’s failure.

The processes that occur while spectators are watching a film also unfold within a specific temporal context. Orienting sounds are based on the principle of recognition. But the memories that they trigger in spectators often also originate in cinematic contexts. How credible an as-if-historical orienting sound is deemed to be is therefore often judged on the basis of historical sounds constructed by film. In semiotic terms, the orienting sound is a signifier of a signifier, behind which the signified disappears. This constellation has a striking effect: on the one hand, orienting sounds are subject to historical transformation, and their symbolic value changes over time;44 on the other, the sounds remain in collective memory for at least as long as they recur in and are conserved by cinema. Although an indexical link is implied between the auditorily modelled historical world and the acoustic realities of a particular historical period, these sounds are also a construction that in turn influences extra-filmic conceptions of history. According to Butzmann and Martin, this use of sound in film reinforces “the emotional significance of certain sounds in public consciousness and anchors their symbolic value in memory.”45 This entails that a film’s ‚sonic histosphere‘ is not only composed of historically indexed sounds, but also associates sounds with conceptions of history. A crucial role is played here by ‚auditory‘ memory, analogous to visual memory. Aesthetics and narrative infuse the sounds with significance, helping to model not just a ‚sonic histosphere‘ but also conceptions of history.

Characters

Alongside space and time, film characters are also an essential element of the ‚sonic histosphere‘. Sound design helps to model ideas about historical figures, for example by associating them with soundscapes, orienting sounds and music. Character’s voices have a particularly close relationship with images and potential conceptions of history. The voice functions here as an extension of the body, through which film sound can awaken the impression of sensuous contact with historical figures. At the same time, the voice conveys linguistically or culturally coded information. I will now explain this dual function in greater detail by applying Roland Barthes’s theory of photography to film sound. The linguistically and culturally coded information conveyed by the voice is deciphered through a cognitive process that is very similar to Barthes’s concept of ‚studium‘.46 But voice also has something contingent about it, which Barthes elsewhere describes as grain. According to Barthes’s theory, the materiality and auditory texture of the voice are able to captivate and mesmerise spectators;47 Barthes highlights in particular the direct, prereflective experience of listening. The “grain” of a voice is thus equivalent in effect to ‚punctum‘, the sensuous, atopic address to spectators that “pricks”, even “wounds” them.48 This entails that historical films are not only able to localise film characters in a historical context or to modulate the experience of time by means of the information conveyed through the films’ aesthetics and narratives, but can also address spectators at a sensuous level. This can evoke a rich sense of historicity, which Sobchack refers to in connection with epic films as the “history effect”.49

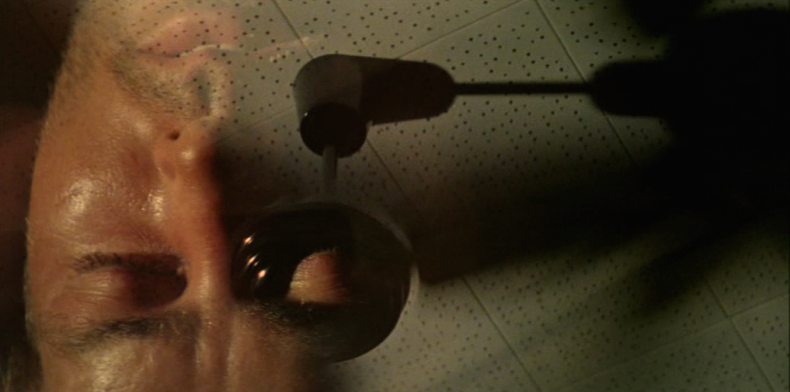

These ideas can also be applied to the opening sequence of THE KING’S SPEECH, in which the situation at the closing of the British Empire Exhibition, when Albert finds himself unable to speak, is not just re-enacted but also audio-visually modelled. The impression of agonising silence is further reinforced by the protagonist’s despairing sighs and the quiet smacking of his lips as they struggle to form words. These non-verbal bodily sounds are enough to trigger a direct emotional response in the spectators and generate a bond of empathy. In addition, extreme close-ups from Albert’s point of view also make it easier to empathise with the situation of the struggling speaker, who stares helplessly at the oversized, menacing-looking microphone.

A cut to the BBC recording studio and the analogue crackle of a sound engineer’s headset pile on even more pressure. Even the radio (the defining mass medium of this period) seems to be waiting for Albert to speak. The barely articulated fragments of words that follow are garbled to the point of incomprehensibility by the reverberation and the technical distortion of his voice. The piercing, dissonant noises that result feel like a quasi-physical assault on the spectators, who will find the situation just as unbearable as Albert and the irritated-looking spectators in the stadium, between whom the film cuts back and forth.

The melancholy string and piano music reinforces the feeling of humiliation. However, the music is not just a commentary, but also an expression of the sequence’s emotional force. As well as modelling the historical event, the sound design also models Albert’s personal tragedy and its contemporary public reception. This gives the film’s protagonist an emotional profile that also affects how the underlying historical events and figures are interpreted. Having the spectators endure the unpleasant situation “with” Albert has the potential to increase the sympathy they feel for the historical figure depicted by the film.

Through its poignant audio-visual representation of Alfred’s struggle to speak, the opening sequence creates an arc of suspense that extends until his big radio address as King George VI at the end of the film. At the level of sound design, the interplay between voice and music is of particular importance for the reception and effect of the sequence. In combination with close-ups, this interplay establishes a close identification with Albert which, to use Sobchack’s terms, is no longer simply of the form “ourselves-now as others-then” but rather “ourselves-now as we-then”.50 As Albert gropes his way from word to word and his voice and articulation gradually become surer, the repetitions of entire musical movements and redundancies allow the audience to share in the protagonist’s feverish excitement.51 The combination of histosphere and close identification makes spectators feel as though they are witnessing a historical audio document being created. During this process, Albert’s voice is doubled: on the one hand, the spectators can (or so it seems) hear the character’s voice directly and in unadulterated form. On the other, the shots of Albert are intercut with images of people listening to his voice on the radio. This radio voice has the same tinny sound and limited tonal range as the original audio document. Siegfried Kracauer called for cinema to make use of sound’s “material qualities”,52 something sound design is able to achieve by artificially altering sounds and voices. One way to create an impression of historicity is to simulate the shortcomings of historical recording and reproduction methods by mimicking the static, crackling and distortion of tonal range, and this technique proves reliable in THE KING’S SPEECH too. The immediacy of the historical moment, by contrast, is emphasised by the hyperrealistic presence of non-verbal, bodily noises that accompany Albert’s production of speech. This counteracts the disembodying effect of the radio, which transforms Albert’s voice into the voice of the king. The artificial, mediatised being that is articulated in the purportedly historical radio address is given back its humanity by the corporeality that resonates in the sound. The soundtrack articulates a Barthesian “this is how it was”53 and forges an emotional bond with the spectators. By making palpable the sensuous experience and materiality of bygone eras and enveloping spectators in soundscapes to which a specific historicity is ascribed, film sound constructs the spatial and temporal dimensions of the ‚sonic histosphere‘. But it is only by simulating the characters’ perceptions that the film enables spectators to experience this quasi-historical world on a foundation of empathy and immersion.

4. Auditory Experience of History: APOCALYPSE NOW

In the previous section, I chose to look at the auditory modelling of history from a constructivist perspective. In this section, the focus shifts to the functioning of the ‚sonic histosphere‘ and the question of how, in combination with film images, it allows spectators to experience history. Before doing so, I’d like to present a few remarks on the concept of experience that I deploy in my analysis.

Francesco Casetti describes filmic experience as the moment

in which, on the one hand, while enjoying a film a spectator measures themselves against images and sounds that directly and powerfully appeal to them, and in which, simultaneously, they reflectively take note of this situation and their action, and projectively anticipate the relationship that they will develop towards themselves and the world on the basis of what they have seen.54

Experience is understood here in accordance with Sobchack’s The Address of the Eye.55 Expanding on the “narrow, ocular-centric scope” of contemporary film theory, Sobchack describes an “embodied, corporeal experience that, on the basis of the synaesthetic organisation of our perceptual apparatus, incorporates the whole spectrum of sensuous experience”.56 Analogously, historical experience can be understood as direct contact with history. According to Frank R. Ankersmit, historical experience of this kind takes us completely unawares and thus prompts critical reflection.57 If a film’s audio-visual design establishes this sort of ‚authentic contact‘ with history, filmic experience can elicit historical experience. Film constructs historical reality by making use of spectators’ capacity to identify with film characters and orient themselves within filmic structures of time and space. The emotional impact of film sound, its instant credibility and the promise of authenticity inherent to it help to thoroughly immerse spectators in the texture of cinematic conceptions of the past. Innovative movements like New Hollywood greatly elevated the role of soundtracks.

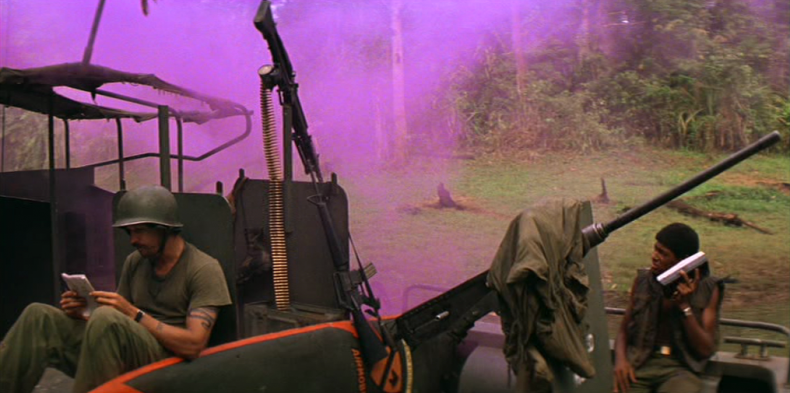

Sound will also be the central focus of this section, in which I discuss how films make historical experiences tangible to spectators. I begin by looking at auditory techniques of subjectivisation and memory, before examining how film sound functions as the emotional texture of perceptions and experiences of history. My analysis focuses on Francis Ford Coppola’s APOCALYPSE NOW as an example of the New Hollywood movement that established sound design as a creative process. Working with Walter Murch, Coppola developed nothing less than a new form of sound experience, including the use of a quadraphonic soundtrack.58 According to Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Wedel, APOCALYPSE NOW was the first film to make “significant use of soundscapes and the subject effects elicited by them in order to represent the Vietnam War”.59 They argue that the film radically upends conventional hierarchies of image and sound: images are desubstantialised, visual perceptions are destabilised and sound is treated as a physical substance.60 APOCALYPSE NOW is based on Joseph Conrad’s novella Heart of Darkness. It tells the story of the war-weary American officer Captain Willard (Martin Sheen), who takes a patrol boat on a fever dream-like odyssey deep into the Cambodian jungle with the mission of “terminating” Colonel Kurtz (Marlon Brando), a renegade American commander. Below, I analyse selected sequences from the film in order to explore how sound can help make trauma and painful history palpable to the senses.

Subjectivisation

At a very early stage in the history of film, Balázs already recognised film sound’s unique potential to “raise […] to the level of consciousness […] soft, intimate sounds” that we do not otherwise become aware of.61 According to Balázs, particular sounds can be singled out and emphasised without undermining a film’s impression of realism: “The wonder of the microphone is that even in the midst of the greatest din, it can detect the softest sound simply by moving up close. […] Each of us thus hears the whispering in this sound close-up right up against his ear, and understands what is said regardless of the simultaneous ambient noise.”62 By moulding perception in this way, sound can also convey the state of mind aroused in a film character by their environment.63 On the basis of identification and immersion, spectators are able to participate in a subjective, sensuous experience of historical worlds and events. This heightens the importance attached to the depicted historical events, figures and circumstances. In reference to New Hollywood, Flückiger notes that “subjectively coloured depictions of the environment” have increasingly become a “strategy” of “mainstream cinema since the mid-seventies”, especially in cases where the “characters’ psychological depth” permits it.64 Audio-visual design focuses not on reconstructing representations of objective historical events but on depicting historical worlds from subjective perspectives. In the following, I show how a historical setting – in this case, the Vietnam War – can be made tangible to spectators through the use of auditory strategies of subjectivisation, taking as my example the opening sequence to APOCALYPSE NOW.

Right from the outset, APOCALYPSE NOW’s soundtrack interacts dynamically with the visual dimension. The first guitar chords and percussion effects from the Doors’ hit “The End” are mixed with a whirring, rhythmic sound that gradually gains substance. We can see a thick jungle with yellow smoke in the foreground. The skids of a helicopter glide through the extreme foreground, out of focus. By means of a stereo effect, the whirring sound follows the helicopter across the screen, thus linking the sound to the helicopter. The jungle erupts into flames almost exactly in time with the first line of the song: “This is the end/ Beautiful friend”. Sound and text reciprocally comment on each other. Shots of the burning jungle are superimposed over a close-up of Captain Willard and a ceiling fan seen from his point of view.

As well as the visual montage, the pervasive, defamiliarised throbbing and whirring of the rotors binds together the two narrative levels. Originally attached only to the helicopters, it is now also transferred to the fan. The focus gradually shifts to Captain Willard’s subjective perspective.65 The soundscape is constructed around the protagonist and expands to 360 degrees. The dissociation of image and sound blurs the boundaries between filmic reality and imagination. Flückiger attributes this “hallucinatory loss of reality” to the absence of noises “corresponding to the visually represented diegetic world”.66 Instead, new connections emerge between the independently existing spheres of sound and image, whose dynamics can trigger somatic effects too, such as vertigo and disorientation. The sound design also draws on a repertoire of auditory forms used in other genres. The representational technique of distorting and defamiliarising sounds is primarily found in horror films, where it “explicitly relates to disorientation and loss of spatiotemporal certainties”.67 Just as Thomas Morsch describes in his apt summary of Sobchack’s The Address of the Eye, APOCALYPSE NOW is a prime example of how film can become an “embodied, corporeal experience that, on the basis of the synaesthetic organisation of our perceptual apparatus, incorporates the whole spectrum of sensuous experience”.68 This phenomenon is closely connected to ‚historical experience‘, which Ankersmit describes as direct “authentic contact”69 with history. Hence, embodied filmic experience can elicit historical experience. In support of this idea, in the following I describe how sound can mould the narrative perspective and what effect this has on the relationship between film and history.

While the music amplifies the blending of perception, memory and imagination, and hence reinforces the impression of subjective experience, the increasingly loud and concrete sound of the rotors ushers in a brief awakening from the fever dream. The superimposed images disappear and the music falls silent, but, as Flückiger notes, “in the brief moment in which the sounds are given a realistic touch, the picture adopts a subjective perspective as a PoV; a shift occurs from auditory to visual subjectivisation”.70 Willard peers through the slats of a blind.

Sounds from the street can be heard, and the sound environment extends71 beyond the confines of the hotel room. Finally, Willard’s comment, “Saigon. – Shit. I’m still only in Saigon”, situates the action in the former Vietnamese capital. At the same time, the voice-over increases the potential for identification. Recorded extremely close up and reproduced on three speakers, it localises Willard’s voice in the spectator’s head.72 However, it is no longer a “voice of God”, the authoritative voice in the tradition of newsreels. Rather, the voice-over helps to establish a quasi-subjective experience of history. The transformation of the city/everyday ambience into the jungle/war ambience once again undermines the connection to reality.73 Accompanied by psychedelic music and distorted, scream-like sounds, recollections of the jungle/war regain the upper hand. We can see Willard stewing in his hotel room, but the percussive music, the lack of any noises from his immediate surroundings and the superimposition of further visual elements show that, mentally, he is back in the jungle/war. The wild frenzy that follows – a mix of tai chi, ecstasy and pain – associates the Vietnam War with an aestheticised form of madness and primordial death drives.

Nonetheless, the order of the filmic reality remains intact. The focus is not on dissolving the filmic reality effect, but on problematising personal-subjective and populist-cinematic perspectives on history. When Willard punches a mirror, the sound is synchronised with his action, which introduces a more objective, observatorial perspective. While these less subjective parts of the sequence contribute to narrative progression, the subjectivisation transforms the historical setting of the Vietnam War into a dimension of sensuous experience. In APOCALYPSE NOW, the Vietnam War is presented less as a factually based military conflict and more as a subjective state of nightmarish delirium. This representation goes far beyond conventional conceptions of history, augmenting them with the dimension of historical experience. This approach to history allows the film to address the objective fact of war trauma and the perceptual disturbances associated with it, which can only be represented subjectively.

Memory

Given that historical films delve into the past from the vantage point of the present, the continuity-creating, associative potential of film sound merits greater attention. As described above, the defamiliarised helicopter noise and the rhythmic, rapturous sounds of the music link together different temporal layers at the start of APOCALYPSE NOW. The subjective portrayal and audio-visual access to the character’s memory open up a mediatised channel into the past. The historical experience evoked by the experience of the film is also accompanied by memories that are triggered in the spectators by the sound. These may be memories of personal experiences and impressions, memories acquired through media or memories of experiences of media. Sounds can thus powerfully stimulate the imagination, without generating concrete visual images. Daniel Deshays elaborates,

Listening means giving oneself over to the rush [‚Rausch‘] of memory – even at the risk of straying down paths that lead to mere fantasy [‚Träumerei‘]. Listening means finding oneself in a momentary state of needing to recognise in order to be able to understand the nature of the chance event.74

These links to memory and contextualisation are of crucial importance to the relationship between film and history. Flückiger notes how fragments of memory are linked to spatiotemporal coordinates:

Sounds, like smells, can catapult us directly back to earlier experiences even years later. They evoke mental images; entire landscapes appear before the inner eye, long-forgotten sensations reawaken. Every place impresses itself as an acoustic bundle of specific sound objects.”75

The underlying principle is the same as that described in Marcel Proust’s novel In Search of Lost Time (1913–27), when the taste of a madeleine dipped in tea vividly reawakens childhood memories. This is very similar to Ankersmit’s conception of historical experience as direct contact with the past. According to Ankersmit, the historical artefact or artwork triggers a personal recollection and evokes an emotional setting that makes it possible to comprehend the sensibilities of a bygone era.76 Applying this idea to historical films, I propose to refer to sounds that bring about these kinds of memory effects as ‚auditory reminiscence triggers‘.77 These effects can relate to personal memories or ones induced by media, in particular memories of the appearance and sound of historical worlds constructed by film. In principle, in order to be able to understand these codes spectators need to belong to a particular sociocultural community. However, the globalised film and media market defies such limits by constantly expanding spectators’ knowledge of diverse film cultures.

In APOCALYPSE NOW’s opening sequence, two different auditory reminiscence triggers are used: the music and the sounds of helicopters. Klas Dykhoff observes that when spectators are shown enigmatic images, they fill in the visual gaps with the help of the soundtrack: “With a minimal amount of visual information and sounds suggesting something, you can get the audiences [‚sic‘] imaginations running.”78 Although on the one hand the Doors song reinforces the “incoherence and ambivalence of the spatiotemporal structure”,79 spectators may also associate the 1967 song with the period of the Vietnam War – either as a result of personal experience or due to memories of media representations of the conflict, which in turn frequently bear the influence of APOCALYPSE NOW. The way in which these associations are formed is determined primarily by spectators’ age and socialisation and by the point in time when they watch the film.

The helicopter noise functions as another type of auditory reminiscence trigger. It awakens spectators’ memories of distorted perceptions during states of delirium – or representations of such states in films. It also serves as a leitmotif, as a bridge between present and past reception of the film.80 The interaction between image and sound in the opening sequence creates a ‚synchresis effect‘81 that combines simultaneously occurring sound and visual effects into a whole. As a result of this effect, individual audio or visual elements from the sequence will spontaneously remind spectators of the event in its entirety even if these elements only recur in isolation later in the film. In APOCALYPSE NOW, the potentially unsettling audio-visual design of the opening sequence simulates a traumatisation of the spectator and remains unconsciously lodged in their memory, waiting to be recalled. Consequently, in later sequences a single audio element, such as the sound of a helicopter, is enough to make the spectator associate the sequence with images of fire, destruction and loss of reality.

In this way, APOCALYPSE NOW constructs a second-order auditory reminiscence trigger whose symbolic character emerges out of the film’s narrative structure. These examples show the degree to which the “rhetorical opposition between elementary imagery and operative tonality”82 breaks down the boundaries between past, present and future. Assisted by the auditory reminiscence triggers, the characters’ constructed perceptions and memories interact with the spectators’ experience. Hence, historical experience is created primarily at the points of intersection between sensuous, embodied filmic experience and narration.

Arousing emotion

There is a close connection between film sound and emotion. Michel Chion even speaks of “composite sensations”83 that go far beyond (purportedly) representing actual sound, in line with the prophecy made by Balázs, the critic and visionary of sound films, back in 1930: “Acoustic impressions, acoustic emotions, acoustic thoughts.”84 In this section, I explore the relationship between auditory affects and the ways in which films allow spectators to experience history.

If filmic affects are understood as the result of audio-visual and narrative operations, of negotiations between film and spectator, then the underlying structures and strategies merit close attention. Hans Jürgen Wulff notes that filmic affect control is not simply a stimulus–response schema; indeed, spectators can even recognise the devices that cinema uses to provoke affects without these devices actually triggering their emotions.85 Hermann Kappelhoff – with reference to Sergei M. Eisenstein – explains that camera movements and montage in particular forge a link between an image’s symbolic structure and the spectator’s affects.86 In the following, I expand the scope of his analysis to include the auditory dimension. I take as my example another sequence from APOCALYPSE NOW: at a remote outpost, the patrol boat’s crew unexpectedly receive letters from home, which they open during their onward journey. The young African American soldier Clean (Laurence Fishburne) has received an audio cassette from his mother, which he puts in a portable cassette recorder. His mother’s recorded voice can be heard with the same clarity as the other soldiers’ voices, until it is silenced by heavy gunfire from the bank. When the attack is over, a weeping Chief Philips (Albert Hall) announces that Clean is dead. Now the voice of Clean’s mother fades back in. At first only faintly audible amidst the other voices, it eventually comes to the fore, accompanied only by disharmonious music. A bitterly ironic contrast is drawn between the images of the dead soldier and the sound of his mother’s voice urging him to come back safe and sound.

The sequence makes use of various audio-visual techniques to arouse emotion. In the following, I examine these techniques with particular attention to sound design. Most of the auditory affects bear no direct semantic relation to the filmic reality (the characters’ reality). Freed from a conceptual connection to their source or a specific semantic code, sounds can trigger a direct emotional response.87 This form of emotional arousal is mainly associated with non-diegetic film music. After the boundary between music and sounds became increasingly blurred in the second half of the twentieth century, in New Hollywood films sound design assumed some of film music’s traditional functions.88 In APOCALYPSE NOW, deep bass undertones create an ominous aura even before the attack on the patrol boat. The low tones utterly engulf the spectators, drowning out any detached reflection.89 Auditory stimuli blend into somatic ones, causing a stress response. As well as the physically palpable bass tones, the film also uses high-pitched, dissonant fragments of music. Like in a horror film, the disharmonious, unsettling sounds arouse a sense of unease. Flückiger observes that high-pitched, jagged tones can have a direct somatic effect, especially ones that resemble a person screaming. According to Flückiger, sound design utilises this effect by adding screams or scream-like sound objects to soundtracks.90 After Clean’s mother’s disembodied voice falls silent, for example, distorted jazz-style trumpets strike up, evoking the sound of screaming. This provokes a direct emotional response in the spectator that can range from inner disquiet to utter shock. In addition, film music also addresses spectators’ cultural memory. Christoph Metzger explains:

Although music and sounds are mainly used as dramaturgical devices that infuse the arc of suspense in a scene with a particular atmosphere, they also simultaneously convey cultural codes that make reference to their origin in other domains […]. These codes, the interplay of which defines the film’s acoustic identity, primarily refer to contemporary history and social labels.91

Metzger’s thesis applies even to this sequence from APOCALYPSE NOW, where the score has been modulated to sound closer to noise than music. For example, the cultural codes contained in jazz emphasise Clean and his mother’s identity as African Americans, a group that suffered disproportionate losses in the Vietnam War. The pain associated with these losses also resonates in Clean’s mother’s voice-over. Here, the sound design is once again fully geared towards the audio-visual construction of affects. The way that the volume of her voice is modulated does not recreate the way that the environment subjectively sounds to the film characters. Nor does it follow the principle of acoustic comprehensibility by keeping the volume consistently at an audible level. Instead, as Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Wedel describe,

the recorded voice of [Clean’s] mother oscillates between the diegetic and the non-diegetic; sometimes becoming quieter, sometimes louder and sometimes disappearing altogether, modulated entirely in accordance with the intention of creating an emotional effect that wrings the maximum pathos out of the technique of ironic detachment.92

At the same time, the disembodied voice also functions as a tapestry of sound “that subliminally [formulates] an emotional appeal through the prosodic features of rhythm and intonation as well as through the tonal qualities of the voice”.93 Accordingly, the auditory characteristics contribute significantly to creating a composite affect of bewilderment and shock. The soundtrack as a whole thus proves to be a texture capable of arousing complex moods and emotional responses. The emotive effect functions not only as the driving force behind the audio-visual experience of history, but also makes spectators empathise and identify with the characters, thus influencing their interpretation of and reflections on the depicted historical events, figures and circumstances.

5. Auditory reflection on history: WALTZ WITH BASHIR

The ‚sonic histosphere‘ models a historical space–time structure and makes history palpable to the senses. At the same time, it enables reflection not just on historical events and circumstances but also on the relationship between film and the writing of history. Robert Burgoyne coined the term “metahistorical film”94 to describe a subgenre of historical film that questions the way in which films represent history. Within this subgenre, there is a tendency towards a hybridisation of fictional, documentary and essay films that blurs the boundaries between the genres. Koch describes filmic projection as a process of making the past immediately present by drawing on the “camera’s ineluctable recording function” and the “diegetic function of the moving image”. Regardless of whether a film is categorised as documentary or fictional, this process of projection can be understood in terms both of documentation and of orchestration and fiction.95 If we wish to investigate the reflective potential of sound design, films in which the “camera’s ineluctable recording function” is suspended are particularly well suited as objects of analysis. A good example of this are animated films that reflect on history,96 such as PERSEPOLIS (Marjane Satrapi / Vincent Paronnaud, F/USA 2007), ALOIS NEBEL (Tomás Lunák, CZE/D 2011) and WALTZ WITH BASHIR. These films use animated images to create distance from extra-filmic reality, giving sound a more important role in creating conceptions of history. At the same time, a gap opens up between the artificial images and the seemingly naturalistic sound, providing a starting point for processes of reflection on history or the self.97

Taking the example of WALTZ WITH BASHIR, I will now build on this idea and show how the interplay between animated images and sound design evokes a specific mode of listening that encourages spectators to engage in reflection. The film’s plot draws on autobiographical information. Its protagonist is the alter ego of the director, Ari Folman. Just like Folman himself, the protagonist witnessed the Sabra and Shatila massacre, in which members of the Lebanese Phalange militia tortured and killed large numbers of civilians in refugee camps. However, he has lost his memories of the massacre, and the film tells the story of his quest to recover them. Using interviews, memory sequences and filmic representations of imaginary visions, it shows “narrative microactivities that the protagonist (and hence the film itself) connects to a macronarrative of the Lebanon War”.98 However, although WALTZ WITH BASHIR imitates the photographic and aesthetic techniques of a live-action film,99 it remains clearly identifiable as an animation at all times. In combination with the voice-over technique and sound design, the animated images create the impression that one is observing “a world ‚coming into existence‘ in the act of reporting”.100 This puts spectators into a specific, reflective mode of reception. Moreover, the repeated use of the same pieces of music across different sequences underscores the constructed nature of filmic representations of history; I will also investigate the reflective potential of this technique. The same applies to the various modes of addressing trauma and memory through the medium of film that WALTZ WITH BASHIR experiments with; by reference to these techniques, I explore the relationship between the ‚sonic histosphere‘ and reflective historiography.

Reflective Listening

In ‚metahistorical films‘, the sound design fosters a specific mode of reception that I refer to as ‚reflective listening‘, a concept based on a phenomenological understanding of reflection about film.101 Fundamentally, reflective listening is similar to what Michel Chion calls “semantic listening”102 in that it arouses spectators’ interest in decoding the film sound as if it were a signal. However, reflective listening in ‚metahistorical films‘ goes further; it creates connections and associations and develops interpretations. In order to specify more precisely the operations of sound design required to achieve this, I shall now turn to WALTZ WITH BASHIR’s opening sequence. The film’s sound design is dominated by Max Richter’s electronic music. Repetitive structures and sustained, haunting sounds start creating a trance-like mood even before the opening credits, displayed against a black background, are over. The bass-heavy beat that begins as the picture fades in acts as an auditory paraphrase for the sequence that now ensues, in which a pack of dogs rampages through the streets with teeth bared. Hyperrealistic breathing, growling and panting sounds create a sense of danger. After the wild race through the city, the furiously barking dogs gather below a window. Above is Ari’s friend Boaz (voiced by Mickey Leon), who looks down fearfully. Boaz recounts this dream to Ari (Ari Folman) in a bar. The haunting music resumes even before the film cuts back to the dream sequence, announcing the vision and preparing spectators for it. The music is used as a leitmotif in memory and dream sequences throughout the film, connecting the filmic reality to subjective fragments of memory that ultimately coalesce into historical experience as Ari recovers more of his memories of violent, traumatic experiences. The switch from the on-screen conversation to Boaz’s voice-over commentary is not marked by a change in the sound. On the contrary, sounds hinting at his spatial surroundings can still be heard in the voice-over: for example, a faint reverberation and ambient noise. Sound thus maintains a link to the filmic present even during dream and memory sequences. This allows the process of remembering traumatic experiences, and the construction of historical experience based on this process, to be grasped at a reflective level. The filmic present, memory and imagination are depicted as fundamentally equal elements of historicisation that are in constant interchange. However, while the film character’s uncertain memory, which is augmented by imaginary visions, is transformed into a sensuous experience through the musical accentuation, the verbocentric filmic present functions as a space for reflection. Following the conversation in the bar, Ari watches Boaz staring at the turbulent sea. The drumming and pattering of raindrops acts like a catalyst for memory: “It often rains during moments of high emotional intensity. Sound designers create an analogy between the release of emotional inhibition and the opening of the heavens”,103 according to Butzmann and Martin. The roar of the sea can also be interpreted symbolically. In reference to the films of Jean-Luc Godard, Fred van der Kooij observes that “noise and the sea have become a closely twinned metaphor of disorder, of chaos; symbols of the totality that the lens constantly encompasses but will never entirely capture.”104 In WALTZ WITH BASHIR, the drumming of the rain and the roar of the sea symbolise the release of disordered flows of memory mixed with imaginary visions. When Ari drives away in his car afterwards, this release gives way to a process of reflection. The regular sound of the windscreen wipers functions like a metronome, giving structure to the haunting soundscapes, which now grow in intensity. In a contextualising, reflective voice-over, Ari identifies the cause of the fragments of traumatic memory for the first time: the war in Lebanon. Eventually, he gets out the car and stands on the promenade. As he stares at the waves beneath the night sky, the camera pans and the promenade is transformed into the shoreline of Beirut.

The sky is filled with flares that bathe the picture in a surreal, yellow tinge. The texture of the music now becomes thicker; the harmony of the sustained bass tones is significantly expanded on and embellished by a repetitive motif on the solo violin. Gradually, the quality of the memory sequence changes: memories of specific events emerge piecemeal out of the symbolic, imaginary visions. Along with other young soldiers, Ari rises naked out of the water and starts getting dressed. The picture has a blue tint, indicating that dawn is breaking. A virtual Steadicam follows Ari and his fellow soldiers into the city. As he turns a corner past a building, the camera pans around him and then lingers on a close-up of his face as women dressed in black push past. The urgent music creates a sense of unease and makes the spectator want to learn more about the events in the Lebanon War. Overall, the heavy editing makes the film sound into a subtle instrument that prefigures analytical reflection on the film. The metaphorical and symbolic use of sounds, evocative music and contextualising voice-over add a level of reflective listening to the ‚sonic histosphere‘. At this level, the film primarily addresses the processing of traumatic experiences, uncertain memories and their relationship to concrete historical events.

Reflective Connections and References

The soundtrack not only moulds the ‚sonic histosphere‘ in individual sequences, but is also capable of creating connections and references that cut across sequences and go beyond linear production of meaning. This approach is underpinned by a semiotic understanding of self-reference.105 For example, multiple sequences can be reciprocally linked through the repeated use of a piece of music, and thus make reference to the constructed nature of the filmic illusion. The linking together of the two sequences begins with a prereflective recognition of something heard earlier. On this basis, a space for reflection is then created in which the sequences are compared with and related to each other. In WALTZ WITH BASHIR, the use of “The Haunted Ocean” as a leitmotif marks the protagonist’s enigmatic fragments of memory, which first appear after the conversation with Boaz at the start of the film. During Ari’s conversation with his friend and therapist Ori (Ori Sivan), the sequence from the start of the film is repeated for the first time, but it only recurs in part (Ari rises naked out of the sea and gets dressed, silhouetted against a bright background). In the final third of the film, during his second conversation with Carmi (Yehezkel Lazarov) in the Netherlands, the sequence is repeated in full again (Ari enters the city with the other soldiers, and at the end women dressed in black push past him). The enigmatic melody of “The Haunted Ocean”, which stands out far more prominently than the rest of the score, clearly delineates the sequence from the film’s plot and assigns it a meta-level function. The repetition gives spectators the opportunity to reflect, while simultaneously laying bare the film’s use of repetition. The sequence is framed by information from the people Ari interviews and the memories evoked by this information. Through this process, the background to the enigmatic images is gradually revealed: for example, the fact that Ari himself fired the flares that immerse the scene in a surreal yellow light, while the Christian Phalange militia were carrying out the massacre. The answers given by Ari’s former war comrades are compared with the fragments of memory, and assembled into a narrative. The repetitive structure of the piece of music, to which additional elements such as a solo violin are gradually added, reflects this process of decoding and reassembling.

Another example shows that the repeated use of a piece of music does not necessarily mean that the sequence that is linked to the music will be repeated in full. When Ari is taking the taxi back to the airport after visiting his friend Carmi in the Netherlands, a bass-heavy beat is played that is very similar to the one that accompanies the opening sequence of dogs rampaging through the city. Ari looks out the window of the car, thinking to himself. Suddenly, the reflections in the glass no longer show the bare trees of the Dutch winter landscape, but instead palm trees and an armoured transport.

Benjamin Beil refers to this kind of “merging of past and present, of unreal and real in a ‚shared filmic space‘” 106 as a “mindscape”:

A ‚mindscape‘ is characterised by the interlacing of the world of memory and filmic reality that emerges out of a complex orchestration [‚Inszenierung‘] of the points of intersection between these two (narrative) levels and a tendency to superimpose and mix ‘real’ and mental worlds.107

In this example sequence from WALTZ WITH BASHIR, the sound design adds an intersequential level to the mindscape. The beat associated with the dogs at the start of the film announces that a potentially traumatic war experience is about to be shown. Conversely, the reference to the Lebanon War during the taxi journey reveals the opening sequence to be a symptom of post-traumatic stress disorder. Sound design can create a complex mindscape within a single sequence too: when Ari steps into the airport terminal in Beirut in another flashback, he imagines it still being in use. While the voice-over maintains contact with the filmic present, a complex soundscape of signals, announcements, buzzing voices and footsteps brings the airport back to life. When Ari eventually becomes aware that the airport has long been disused, the “airport” soundscape is replaced by the “war” soundscape. Military commands, helicopter noises and dull explosions situate the protagonist back in the time of the Lebanon War.

A final example shows how the repeated use of a piece of music can also be used to question the veracity of memories. While Ori (speaking off-screen) describes a memory experiment that is visualised on-screen, Johann Sebastian Bach’s Harpsichord Concerto No. 5 in F minor plays. In the experiment, the test subjects were shown photos from their childhood, one of which (a visit to an amusement park) was a fake. But most of the subjects nonetheless regarded the picture as real, and with a little prompting could remember visiting the amusement park too. The soothing classical music – in combination with electrical sound effects and the stalls and visitors that are added to the image one after the other – underscores the impression of an experimental set-up. This effect is also significant in the second sequence where the piece is used: when a boy in an orchard fires an RPG at an Israeli troop transport, Bach plays once again. The sequence unfolds in slow motion, giving the spectator space to reflect. Only when the Israeli soldiers shoot down the boy in a hail of gunfire does the representation of time return to normal. The musical reference and the manipulation of time make the situation in the orchard seem like an experimental set-up too, bringing the reliability of apparent memories into question. Hence, the reflective linking of different sequences by means of film sound can be either unifying or deconstructive in nature. The repeated use of “The Haunted Ocean” and the bass-heavy beat connects the sequences and shows how memories of concrete events are distilled from the flow of imaginary thoughts. However, the musical link between the orchard sequence and the memory experiment casts fresh doubts on the reliability of the conceptions of history thus constructed on the basis of apparent memories.

Reflective Mediatisation

Audio-visual media have developed various formats and strategies for representing history and memory. ‚Metahistorical films‘ question and analyse these formats and strategies by accentuating and juxtaposing them audio-visually. In the context of this reflective mediatisation, the ‚sonic histosphere‘ is instrumental both in simulating the underlying formats and audio-visual strategies, and in self-reflectively questioning them. In the following, by reference to WALTZ WITH BASHIR I illustrate the significant role played by film sound and sound design in this process. One powerful example is a memory sequence in which Ronny (Ronny Dayag), another of Ari’s former war comrades, swims to safety after being separated from his unit when they are attacked on the beach. Quick cuts and simulated shaky camera motions are accompanied by urgent, suspenseful music. The sound design adds thunderous explosions, machine-gun salvos and whirring projectiles. The sequence mirrors the style of hyperrealistic war films like SAVING PRIVATE RYAN (Steven Spielberg, USA 1998). The images and sound are geared to making the battle palpable to the spectators’ senses. Only Ronny’s unemotional voice-over serves to provide analytical feedback. After Ronny has swum to safety, epic orchestral music begins playing, with string and wind elements that could have been taken straight from the soundtrack of a conventional Hollywood war film. But the second part of the episode undercuts the pathos of the story of survival. A soldier walks up to the precise spot where Ronny escaped into the sea and starts playing air guitar on his rifle, which is synchronised with the opening chords of the song “Beirut”.108 This makes the sequence resemble a music video in which editing and visual design are subordinated to sound. While the soldier continues playing air guitar on his rifle in the foreground, behind him a time-lapse sequence unfolds showing the beach being retaken. The sequence is followed by a shot of a surfing soldier – a clear reference to APOCALYPSE NOW. Mortar shells strike the water around him. The sounds of shots and explosions keep the war present at the auditory level. Following a cut back to the filmic present, further battle scenes with large numbers of civilian casualties are shown in a montage cut to the rhythm of the music. With its marked indifference towards the “collateral damage”, the music video (a format borrowed from television) refracts the images of conflict through an ironic, sarcastic lens.

The second example, by contrast, takes a psychological perspective. Ari interviews a psychologist (Zahava Solomon) who discusses cognitive defence mechanisms. She describes a soldier who persuaded himself he was seeing the war through a still camera, allowing him to assume the role of a detached observer. This perspective is illustrated by still images of war scenes, accompanied by soothing music. The length of the sequence makes it possible for spectators to reflect on the “technical and epistemological limits of photography”109 with respect to the representation of history. In a voice-over, the psychologist explains that when the soldier witnessed a traumatic event – a large number of horses lying dead or dying – this imaginary camera was shattered. Like a film strip running through a projector, the images start moving. The adjustment of the focus and position of the image and the steady rattling sound of the film spool simulate the physical effect that transforms still images into moving ones. The soldier’s mode of perception switches from detached observation to sensuous experience. Clearly identifiable sounds from objects shown on-screen, such as the buzzing of flies on the carcasses and the neighing of horses, reinforce the sense of reality thus created. The materiality of the sound design suggests a synaesthetic perception that goes far beyond the senses of sight and hearing, and conveys an almost tactile, olfactory experience of the dead and dying animals. Hence, the sequence demonstrates how film sound can add a sensuous, somatic dimension to artificial, detached photography (and, later, to moving images too).

Having simulated examples of various media formats used to represent history (Hollywood film, music video, photography), the end of the film adds another approach to this ensemble that reflects on the tension between representation and audio-visual design. In the style of a multiperspectival documentary, the interview sequences and visualisations of characters’ memories are assembled into a reconstruction of the Sabra and Shatila massacre. When the slaughter is over, the same images are used as in the final part of Ari’s enigmatic memory sequence. But instead of Max Richter’s “The Haunted Ocean”, we hear a clamour of weeping and plaintive cries as the women dressed in black push past Ari. Finally, the film cuts from Ari’s subjective perspective to documentary video footage. Felix Hasebrink regards this as a “gaping wound in the film’s aesthetic structure” from which memory and the past emerge “as if that which had always been lurking beneath the layers of animated images were now pressing to the film’s surface.”110 The aesthetic break in the closing sequence opens up a self-reflective level where film’s potential to represent and model history can be interrogated, with the sound referring to the audio-visually constructed relationship between reality and filmic representation. The unindividuated cries from the animated part of the sequence are linked in the documentary images to visually recognisable sources: the women are now shown separately, and their individual voices are synchronised with the images. The merging of image and sound in a point of synchronisation111 further underscores the aesthetic break. Sound thus functions as a reflective device that ruptures the integrity of the ‚sonic histosphere‘ and makes spectators aware of the film’s construction and modelling of history. However, this also retrospectively consolidates the ‚sonic histosphere‘ by bridging the visual discontinuity in the transition from animation to live-action film.

In the foregoing analysis, I have shown how sound design is an autonomous dimension of film design. In the form of the ‚sonic histosphere‘, sound design models history, makes it a palpable object of experience and prompts critical reflection. Film sound thus not only plays a key role in constructing filmic representations of history, but also in critically questioning and reinterpreting these representations. This is a topic that requires further detailed research.

- 1Cf. Rasmus Greiner and Winfried Pauleit: “Sonic Icons and Histospheres: On the Political Aesthetics of an Audio History of Film”. In: Leif Kramp et al. (eds): Politics, Civil Society and Participation. Bremen 2016, pp. 311–321.

- 2Vivian Sobchack: The Address of the Eye: A Phenomenology of Film Experience. Princeton 1992.

- 3Michel Chion understands film sound as a subtle means of emotional and semantic manipulation that directly influences the spectator’s physiology and perceptions. Cf. Michel Chion: Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. New York 1994, p. XXVI.

- 4Cf. Barbara Flückiger: Sound Design: Die virtuelle Klangwelt des Films. Marburg 2012, p. 13.

- 5Ibid., p. 17.

- 6Ibid.

- 7Cf. Rasmus Greiner and Winfried Pauleit: “Audio History des Films”. In: Nach dem Film, 14: Audio History, 2015. www.nachdemfilm.de/content/audio-history-des-films.

- 8See Rick Altman: “Four and a Half Film Fallacies”. In: Rick Altman (ed.): Sound Theory, Sound Practice. New York et al. 1992, pp. 35–45.

- 9Cf. ibid., p. 42.

- 10Chion 1994, op. cit., p. 107.

- 11Cf. Frieder Butzmann and Jean Martin: Filmgeräusch. Wahrnehmungsfelder eines Mediums. Hofheim 2012, p. 153.

- 12Sven Kramer: “Neuere Aneignungen von dokumentarischem Filmmaterial aus der Zeit der Shoah”. In: Delia González de Reufels, Rasmus Greiner and Winfried Pauleit (eds): Film und Geschichte. Produktion und Erfahrung von Geschichte durch Bewegtbild und Ton. Berlin 2015, p. 32.