Exacting the Trace

Re-archiving Film Historiography in PHOENIX (Christian Petzold, 2014)

Table of Contents

Secret Publics

Digital Digging

Movie Theatre(s) of Memory

Filmography of the Genocide

Exacting the Trace

Destroyed Statues, a Bolex 16 mm Camera, and an Old Jeep

“…will you show that on your British television?” ACCEPTABLE LEVELS as Historiographic Metafiction

Work and Life

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Mazor, Yael. “Exacting the Trace: Re-archiving Film Historiography in PHOENIX (Christian Petzold, 2014).” Research in Film and History. Audiovisual Traces, no. 4 (February 2022): 1–14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/18102.

Introduction

Berlin, 1945. World War II has ended in Europe, and Nelly has returned home after surviving the camps. Accompanied by her friend Lene, Nelly is brought back to receive medical care that is meant to reconstruct her face destroyed by a gunshot wound. Presented with the choice by her surgeon of whom she would like to resemble, her simple answer stating ‘myself’ seems like an unlikely choice for a German-Jew. After all, claims the doctor, given the opportunity, many would opt for an erasure of their most recent past and begin anew. Indeed, the remainder of Nelly’s past, traces of her former self, are echoed throughout the film as a constant reminder of the inability to go back, while also facing the implausibility of a future. Convalescing in her hospital bed, the framed picture hanging on the wall beside her is that of Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus. This particular choice of painting is no coincidence, since we may in fact understand it as the map through which to read the film in its entirety. Angelus Novus, or the ‘Angel of History’ as Walter Benjamin described this amorphous entity, is a symbol of how filmmaker Christian Petzold approaches history in PHOENIX (DE 2014), from which the scene described above is taken.1 In an interview upon the release of his penultimate feature, TRANSIT (DE 2018), Petzold stated that cinema, much like the Angel of History, is bound by the rubbles of the past that amass in front of him, claiming that “precisely because it looks back, cinema feels that which lies before us.”2 As a film that clearly takes place in the past, and considering the historical events of WWII and the Holocaust that serve as its premise, PHOENIX is an unusual historical drama in how it addresses its subject matter.

In the following article, I wish to examine Petzold’s film as part of the ongoing engagement with the notion of the archive in film studies over recent years with the explicit intent of re-assessing the role of fiction films as part of archival film practices in their capacity to act as audio-visual traces of the past. Through the concept of ‘archiveology’ introduced by Catherine Russell, I propose looking at PHOENIX as an example of how filmic references to the historical may be understood as a practice of archiveology, despite not being composed of archival excerpts or fragments. I argue that Petzold’s engagement with history in his film materializes through his focus on the ‘trace’ as removed from a representation of the event, maintaining Giorgio Agamben’s notion of the gesture in relation to the image. Agamben’s concept of the gesture relies on Walter Benjamin’s perception of language, understanding the filmic in its ability to create ‘repetition’ and ‘stoppage’. Hence, traces of the past are manifested in Petzold’s film, as I claim, through deconstructing film historiography and subsequently re-establishing it.

The Return of the Past? Petzold and the Historical Film

Petzold’s films are undeniably concerned with the past, though more often than not, the past relies on inference and contextualization. This treatment of history has been remarked upon, most prominently through writing that considers the filmmaker’s unique approach to genre films, in which the protagonists are likened to ghosts that live in the ‘aftermath of history’.3 This last point has differentiated Petzold’s films from a corpus of German filmmaking in the latter half of the 20th century and increasingly since the 1990s onwards. In this “cinema of consensus,”4 German cinematic productions that have emulated British heritage films of the 1980s have turned to reenacting the events of the 20th century in an increasing preoccupation with Germany’s recent history under totalitarian regimes.5 This wave of films that according to Marco Abel “exude significant appeal for an international audience” is such that addresses the German past to “pathologically corroborate the ideologically convenient belief that this notion is almost exclusively still reducible to its totalitarian past(s).”6

In contrast to some of his contemporaries, Petzold has explicitly stated his aversion to any attempt to re-create historical events for the screen.7 It was therefore all the more surprising when in 2012 the director seemingly went against his own inclinations with the release of the GDR drama BARBARA (DE 2012), the first installment in the semi-official trilogy dubbed ‘Love in times of totalitarian regimes’, followed by PHOENIX and TRANSIT (2018). BARBARA takes place in the early 1980s, describing the transfer of Berlin-based physician Barbara Wolff to a provincial hospital in the former GDR, supposedly as punishment for insubordination. PHOENIX is a post-WWII drama that returns to the rubbles of Berlin in 1945, when Nelly, a Jewish woman who has miraculously survived the camps and a fatal gunshot to the head returns to Germany only to find that the life she previously knew can no longer be reclaimed. TRANSIT is an adaptation of Anna Seghers’ novel from 1944 that describes the life of German refugees in France at the time of the Nazi regime. Whereas both BARBARA and PHOENIX clearly take place in the historical period they describe, TRANSIT follows along the narrative and locations of Seghers’ novel but with one major difference: it occurs in present-day France. While each of these films deals with a specific period of German history, neither of them follows along the lines of what Jaimey Fisher described as a German “production trend” of the 2000s.8 According to Fisher, the international success and accolades bestowed on German historical productions, THE LIVES OF OTHERS (DE 2006) being a prominent example, stems from their melodramatic structure. Thus, these popular historical films have a general appeal that is based on a coherent and chronological depiction of history that facilitates and mediates the complexity of these events for a global audience.9

Indeed, it would therefore seem that Petzold’s recent turn to historical fiction is all the more questionable and curious. In approaching history, these films exhibit a “Benjaminian sensibility” to the past that consists of undertaking “an ‘archaeological’ approach,” that is, “archaeologically excavating and reconstructing in order to understand the past and its crucial transitions.”10 The reference to Benjamin made by Jaimey Fisher in this respect is to the former’s theory of history as laid out in his Theses on the Philosophy of History, recalling Benjamin’s advocation of a nonchronological historiography, “brushed against the grain,” such that denies the notion of progress, and embraces the “time of the now” as a privileged form of writing.11 In other words, Petzold’s recourse to history in his films relies on the layering of temporal strata in which the present moment is imbued with both past and future. In this stratification, Fisher claims, the excavated traces of genre films and film genres, measured against how we have come to know and recognize them from a current vantage point, also serve to mark the historical transitions that in Petzold’s films are realized through these appropriated generic means.12 Considering the appeal of German historical film worldwide that emerged in large part due to its generic structure, Petzold’s use and reference to genre films becomes a significant factor in understanding his countering of the all-too-familiar historical narratives regarding the immediate post-war period.

PHOENIX is a film that tells the story of Nelly, a German-Jew that returns to Germany after the war, only to discover that her spouse has divorced her, and now, believing that she is dead, wishes to claim her inherited fortune. Seeking him out, Nelly finds Johnny, or Johannes, who fails to recognize his dead-but-very-much-alive wife. And yet, she looks similar enough for him to attempt and ‘direct’ Nelly, now going by Esther, to pose as Nelly for the purpose of cashing in on the inheritance. Petzold’s film returns to a mélange of filmic and cultural references, most notably Alfred Hitchcock’s VERTIGO (US 1958), but also Georges Franju’s EYES WITHOUT A FACE (FR 1960), F. W. Murnau’s NOSFERATU: A SYMPHONY OF TERROR (DE 1922), post-war rubble films such as Wolfgang Staudte’s THE MURDERERS ARE AMONG US (DE 1946), and Helmut Käutner’s UNDER THE BRIDGES (DE 1946),13 but also Roberto Rossellini’s GERMANY YEAR ZERO (IT 1948), as well as Hubert Monteihllet’s novel Return from the Ashes.14 In all these examples an excavation emerges, a work of archaeology that seizes the historical in each of these ‘sources’ only to disconnect from them for the purpose of conveying a temporal transition. This method of “citing without quotation marks”15 is representative of Benjamin’s methodology of historical writing, where the principle of montage is implemented in writing history, as recently echoed in Catherine Russell’s theorization of ‘archiveology’.16 It is therefore in this vein that I wish to continue my discussion of Petzold’s film, in light of Russell’s proposal of archiveology as a critical method for understanding the structuring of historical memories.17 I suggest reading Petzold’s film as a mode of archiveology in its treatment of historical subject matter and focus on how re-archiving film historiography is an essential component of the filmmaker’s approach to history in his films.

Re-archiving Traces: Language and History

In the proliferating debates surrounding the concept of the ‘archive’ in film studies, Russell’s discussion of archival practices focuses on the use of archive materials, or the appropriation of previously shot footage. These archival excerpts are perceived not just for the manner in which they may create cinematic disjunctures, attesting to what Jaimie Baron described as ‘temporal’ and ‘intentional disparities’, but also to the way archival practices are intimately linked to processes of remembering.18 Russell’s discussion of archival practices may therefore be situated in the wider context of memory studies and its implications in the study of film and history, especially when concerned with traumatic pasts.

The notion of ‘postmemory’, as formulated by Marianne Hirsch, for example, maintains that events of the past, especially traumatic ones, are experienced by children of survivors and future generations through mediated means such as photographs that perpetuate the intensity of the trauma, however without providing a full understanding of the circumstances of past events. Thus, memories of the past are essentially ‘prosthetic memories’, as described by Alison Landsberg, such that may unite a community through a shared repository of memories that are transferred and disseminated to varied audiences by means of mass media. In this sense, cultural products that mediate memories of the past through popular forms of entertainment, follow along the lines of Astrid Erll and Ann Rigney’s description of how memory and memorialization today are cultural memories in which social processes that pertain to a continued production of views of the past are scrutinized. These processes are particularly relevant when examining the role played by various media, cinema being one of them, in the shaping and impacting of such views of the historical past. The past is therefore not only mediated, but also remediated time and time again through the reiteration of memory production through and across a plethora of cultural channels of communication and references.19

Russell’s continued preoccupation with the shaping of the past is therefore connected to the already recognized mission of archives today and their participation in the undoing of historical narratives as archives realize their subversive potential enabled by rapidly shifting technologies.20 The history which archival practices produce is according to Russell best understood in light of the cultural theory proposed in the writings of Walter Benjamin, and this approach is taken as a heuristic methodology in the readings of films that practice archiveology. Thus, Benjamin’s ‘Denkbild,’ or ‘thought-image’, reflects the dialectical effect of appropriating archival materials in order to re-write historical narratives. This effect, according to Russell, is what lies at the heart of archiveology as it emerges through archival film practices that stitch together fragments and traces of previously shot materials while taking apart chronological structures of historical knowledge. As such, the focus is placed on the work of montage in taking apart and reconnecting the fragments, rather than on the events recorded in the archival excerpts themselves. Russell opts for an approach that prefers the analysis of non-fiction films in which the work of montage and evidence of fragmentation is made clearer. However, she still recognizes “the potential of film history in its cut-up form” as an “open possibility” to further understand the practices of archiveology.21 Archiveology is therefore primarily a method of analysis from which we may understand the work of archiving as twofold. Firstly, it considers the ‘archive’ as a source of information and images that actively engages with remnants of the past. Secondly, this engagement with the past is based on an undoing and re-narration of history in the process of learning how history is written through film.

Based on Russell’s proposal, I therefore wish to further inquire into this above-mentioned “potential” and examine this underexplored prospect of archiving through the “wounding and trauma to the integrity of narrative cinema,”22 asking if and how a film that is based on narrative continuity, such as a historical drama, might archive remnants or traces of the past? Moreover, do these traces necessarily appear as previous recordings of historical events, or might the past also be invoked differently? With Petzold’s film in mind, I propose to explore how the archive, or rather the work of archiving, can transcend not only historical and temporal boundaries, but cinematic boundaries in particular. That is to say, I suggest reading Petzold’s film as one possible way of understanding how archiveology may be realized in narrative form rather than through works of appropriation involving the incorporation of previously shot materials. Thus, PHOENIX draws on traces that emerge not only from fragments and excerpts, but also from a fictionalized narrative that is likewise capable of fracturing the chronological structures of history that archiveology seeks to dismantle, or at the very least take to task.

This once again returns us to the issue of how traces of the past are registered within a cinematic text, and moreover, what kind of links to the past these inscriptions produce. Georges Didi Huberman’s understanding of the trace might prove useful in this respect. In his study of the work of Aby Warburg, Didi-Huberman places an emphasis on Warburg’s term of ‘Nachleben,’ or ‘afterlife’ of images throughout time. Warburg, according to Did-Huberman, introduced the notion of temporality into art history, or to be precise, the image as separated from its own time. That is to say, that there is a temporal aspect of writing a history of images, and writing history through images, that displaces the images from their own time, thus ‘anachronizing’ the present in which they re-appear.23 Warburg’s exploration of the return of forms in art therefore perceives this return as a survival — as a trace — that enters a different temporal regime with its repetition. Didi-Huberman concludes that “forms survive” as “history opens up.”24 In this temporal displacement through the image, its historical context is prone to re-examination and may appear, much like Benjamin’s concept of the dialectical image, within an entirely different time and place than that of its own production. As Didi-Huberman has stressed, Warburg’s work indicates that there is no history of art without a specific concept or notion of temporality, therefore reiterating that history, as it is relayed visually, always already contains a perception of time that can be understood through the image. Hence, the trace, according to Didi-Huberman, is the inscription of history according to a specific understanding of temporality that the image conveys in how it approaches the past. However, following Did-Huberman, we might also ask how might the trace be formally realized in a film? In Didi-Huberman’s advocation of Warburg the initial critique claimed against the latter persists, namely that the notion of this temporal transition through images remains vague and methodologically ungrounded. Temporality itself is a fickle term in this respect, since it may come to signify many things, especially if we consider its cinema-related usage. Nevertheless, for the purpose of the current debate, I discuss temporality as imbued in the notion of history that emerges from Petzold’s films and therefore linked to the idea of the trace of images as that which presents a ‘displaced’ or anachronistic image of history. In other words, to understand the link to the past in Petzold’s film requires an understanding of how traces of the past appear in it so as to re-open history and thereby its temporal structure. In the case of Petzold’s genre-based narrative filmmaking another query raised concerns the way this seemingly chronological depiction of events is disrupted in the process of linking the film’s realization of its subject matter to the historical background. Thus, I wish to return to Benjamin’s historiographic method as discussed by Russell and elaborate on one of the aspects mentioned in her study that specifically builds on the effect of Benjamin’s understanding of ‘language’ in his theorization of historical writing. In this, I am referring to Russell’s turn to Giorgio Agamben’s notion of the gesture and its relation to the workings of the dialectical montage.

Archiveology is a critical method engaged in the construction of historical memory “through the practice of remixing, recycling, and reconfiguring the image bank.”25 Russell asks: “Is this a new mode of film language?” suggesting that the use of the image bank, or archive, is a language in itself. But what does ‘language’ mean in this respect? The allegorical nature of language that Benjamin promotes in The Origin of German Tragic Drama26 is such where meaning is not inferred from language itself but instead signals an understanding that lies beyond the signs of language. Benjamin seeks a ‘meta-language’ that will allow for communication without mediating and anchoring within a set system of signifiers. This arguably is a somewhat utopian wish that further complicates the idea of images and their interpretation, especially when thinking of history as that which is often represented through film, since the past is accessed or experienced only in retrospect. A pressing question in this context would be, is there also a language of history?

Giorgio Agamben’s notion of gesture returns to Benjamin’s search for such a ‘nonrepresentational’ language, further claiming that it is the experience of language that is the task of the historian in the present. That is, language is to be experienced as a means that has no end, not mediated and convoluted through arbitrary signifiers that turn language into discourse, or into a representation.27 According to Agamben, the purest state of communication is likened to that of ‘infancy’, when humans still do not possess language and therefore cannot corrupt its ethical function of maintaining communicability, or the open possibility of maintaining communication. Once humans acquire language, it turns into representation, therefore straying from this primary intention of a form of communication devoid of wrongful appropriations.28 Thus, he seeks to explore the possibility of a language that will remain open and unincumbered by signification. While realizing that Western philosophy and linguistics have failed in providing an adequate alternative to a language founded on negativity, for Agamben, the “exposition of language as a means of communication”29 is a possibility of maintaining language as a ‘mode of communicability’. In exposing language, what is stressed is rather the barrier, or the fracture where appearance turns into discourse. Language, however, is where Agamben also detects the move into history, indicating that history itself is always a mode of mediated representation. How then can we speak of history when the very discussion itself seems to be inherently faulted? How can the notion of gesture perform the task of the exposition and what might be considered as a gesture in this respect?

Russell has proposed that gesture can be detected through Agamben’s concept of the ‘face’ as that which communicates the unmediated experience of language. Thus, a close-up serves as a concrete cinematic example of how to expose the fracture or break between image and signification.30 Following up on this, I suggest going back to what Agamben considers as exemplary of a ‘cinema of gesture’ to further understand the role of the face in exposing the machinations of language as it turns into representation. The return “to the homeland of gesture”31 has to do with what Agamben perceives as the “transcendentals of cinema,” its constitutive elements that are realized in the principle of montage. In writing on the films of Guy Debord, Agamben names these elements ‘repetition’ and ‘stoppage’.32

Repetition is a return to an existing image. It applies not so much in the sense of only repeating the same image, but rather of returning to the potentiality of the image, of ‘what might have been’, that is returning to an image for what it might have come to signify and in this return/ repetition attempting to invest it with new potential meaning. Stoppage, the second transcendental, refers to an act of interrupting the flow of the image, and by this exposing the mediality of cinema. Repetition and stoppage thus realize the task of exposing the fracture that separates the image as appearance from the image as representation.

However, I would argue that even though Agamben’s examples refer to non-narrative cinema, what remains essential in his depiction of the fracture as an exposition of cinema’s mediality, its mode of communication, is a manner through which it links history to a perception of time. As Alysia Garrison notes in this regard:

For Agamben historicity is at once synchronic and diachronic; the human enters history by exposing the discontinuity of language and also the discontinuity of time. Following Benjamin and Nietzsche, he believes that history is not a linear progression, a sequence of events like the beads of a rosary, but untimely, riddled by gaps, disjuncture and anachronism.33

Thus, devising a new understanding of history has to do with realigning history with another perception of time, one that is not linear and chronological. But rather than just impeding time through exposing the discontinuities of history, the contemporary, or the historian, according to Agamben, must also “suture this break or this wound.”34

Put differently, history is where time is overturned and interpolated, and through the meeting between past and present history is exposed as this transformation of time. But history is also the reconnection of fragments and therefore also the realigning of time, thus establishing a new intelligible relation or link to the past. Repetition and stoppage may therefore be perceived for how they not only fracture and expose the language of film, but also for how they sew it back together. More importantly, it is the manner in which they expose the various temporalities of a film as a ‘language’ that creates a notion of history.

‘Reconstructing’ the Face: Deconstructing and Reclaiming Film Historiography

Nelly’s entrance into the film presents her with a bandaged face, speechless. Returning to Germany and crossing the border into Berlin is a passage into the world of the past, where she existed in her former identity. The bridge that appears at the beginning of PHOENIX is a threshold into another world, a realm where both Nelly and her friend Lene traverse as ghosts. Indeed, this ghostly reference is aligned with Fisher’s description of Petzold’s ‘ghostly archaeology’ and recalls one of the major influences cited by the filmmaker, namely that of Murnau’s NOSFERATU. While PHOENIX can hardly be described as a horror film, this turn to Murnau is understood precisely through the bridge, the passage into another world that Hutter in NOSFERATU pauses on before he proceeds to cross over into the country dominated by the dark shadows of Count Orlok.35 This passage into another realm appears also in previous works by Petzold that mark this transience from one state of existence into another. However, another and no less significant factor in this shift begins with the close-up on the face that emerges silent out of darkness, recalling Agamben’s description of the move from the silence of ‘infancy’ into taking one’s place among history. As the notion of the gesture in cinema indicates, this transition into history bears an ethical significance, which given PHOENIX’s particular historical background seems to present poignant and urgent discussions as to what this significance might entail. 36 Nevertheless, this progression can be detected in the initial close-up that is emblematic of Petzold’s films.

It is an element we can see, for example, in the opening of BARBARA, tracking Barbara Wolff’s arrival in the East German province town. The film begins with a close-up on her face as she is shown standing in a public transportation vehicle. This opening shot that is characteristic of many of Petzold’s films is not a conventional establishing shot. Viewers are not informed straight away of the location they are seeing, but instead, see the silent face of the protagonist, often on the way to an unknown destination. The following shot has Barbara disembarking the bus into the town square as she attempts to get her bearings. It is at this moment that we realize that she is displaced from her natural surroundings having entered a new and strange world.

Similar film openings take place in Petzold’s ‘Ghosts’ trilogy, beginning with THE STATE I AM IN (DE 2000), in which Jeanne, the teenage daughter of former RAF terrorists is filmed in close-up, remaining silent, again without prior viewer knowledge as to her whereabouts. As the film cuts to the next shot, she is shown against a background of a vast and empty beach, her gaze combing the horizon to make sure that she is not being watched. The opening of GHOSTS (DE 2005) is more similar to the later examples, as we see the face of a man driving in his car, presumably on his way to somewhere. He remains speechless and the only sound we hear is the extra-diegetic sound of opera that accompanies this shot. We soon realize that he is driving to a city—Berlin. His license plates show that he is arriving from France. This sequence shows again a crossing into a foreign terrain, the purpose of which at this point is yet to be established.

GHOSTS unfolds as a story of Nina, an orphan teenager with mental problems that relies on the work and aid of social services. By chance she meets Toni, a young woman who crosses the park where Nina is assigned to work. They are united in a failed attempt to improve their lives. Meanwhile Francoise, the wife of Pierre, whom we see in the film’s opening, encounters Nina on the street and believes she is her lost daughter who was kidnapped years ago. Nina, as well as Toni and Francoise, wander the Berlin terrain aimlessly as specters that seek to find that which defines them. The third installment of the Ghosts trilogy, YELLA (DE 2007), yet again repeats the unusual opening sequence of the silent face in close-up, this time of Yella Fichte, a recently separated woman from the former GDR who is travelling back to her home town after having attended a job interview in Hanover. Again, the only indication to her location is given by the flickering background image which suggests that she is on a moving train. Having found a job in the former West, Yella is about to leave her father’s house and attempt to make a new life for herself in the business world of the city. In a clearer homage to the horror genre, YELLA’s direct reference to Herk Hervey’s CARNIVAL OF SOULS (US 1962) leaves no doubt as to Yella’s own literal ghostly existence throughout the film. Emerging from a crash site under the bridge from which the car she was in had been found leads her into uncharted territory, this time it is the land of the living. Thus, the face is the point of entry into a search, a journey across an unknown space—also indicated in the transitory nature of the locations through which it passes—that serves as a displacement of time in the sense of disrupting the temporal order of the diegesis. Where the assumed natural order of things that move from life to death, from the past into the future is questioned through the entrance of the protagonists into these worlds, chronological temporality is challenged. The anachronistic presence of the protagonists ruptures the perceived and accepted notion of the images through which these worlds have been commonly depicted. This is particularly true of the more recent trilogy in which the historical world is reconstructed, and it is also why these examples in Petzold’s oeuvre are all the more interesting in the images of history that they relay to viewers.

Returning to the function of the face in PHOENIX, the silence that opens the film gradually develops into a search for identity as the protagonist passes from a ‘state of infancy’ to becoming a part of history. The notion of history in Petzold’s films, as noted earlier, follows along the Benjaminian perception of the dialectical image in which history emerges out of the clash of constellations that are contained within the image. And yet these need not be the depiction of historical events which PHOENIX does not present. Instead, history surfaces as a trace that is evoked through the film historiographical references appearing at certain points of intersection that the face gives rise to as a form of gesture. This gesture may be detected in understanding these intersections through repetition and stoppage, the ‘transcendentals’ of cinema that are also indicative of where the break occurs between the image as appearance and the image as representation. I would therefore like to continue with such instances in the film that exemplify how the face serves as the site through which this process of entering history unfolds, while taking apart historiographic trajectories.

Nelly’s gradual move from a completely covered and unrecognizable face to the attempt to enlist her face in an act of disguise, marks two crucial points in the film that depict this transition from not having a face, and therefore also not having an identity, to the regaining of the face and the choice of embracing identity. In the course of the film, the face serves as a site through which expression is enabled, and this enabling is also indicative of the possibility not to choose, and indeed to eventually trace one’s own way in the world.

Nelly’s discussion of her future appearance after the surgery she is to undergo exemplifies how this process begins by introducing the primary conflict that is presented between the desire to return to the past on the one hand, and the need to move ahead into a future, on the other hand. Approached by her surgeon, Nelly is presented with the choice of whom she wishes to appear like as her ‘new self’. Half-jokingly, the doctor asks if she would like to resemble Zarah Leander or Kristina Söderbaum, although, as the good doctor remarks, “these two are not as popular today as they used to be.” Dr. Bongartz is of course referring to two of Nazi cinema’s most popular female film stars, and this as he continues to explain, might prove to be more problematic than helpful. But a further question posed to Nelly by the doctor wishes to understand why she, as a Jew, chose to return to Germany at all. Thus, identity is presented as a matter of choice, and furthermore, as one that can be mastered trough the correct and proper design of one’s appearance. The very idea of a choice that is expressed in whether she would prefer to be a ‘Leander’ or a ‘Söderbaum’ indicates that identity is also one which can be implemented anachronistically, meaning that to change an identity entails literally appearing as belonging to another time. Identity is thus tied to either the continuation or disruption of historical chronology, and thereby to how one perceives time. As Nelly insists on returning to her former self, to be “exactly how she was,” this conflict of temporalities that is linked to the formation of identity is further exacerbated as it is clear that this will not be achieved, and thus the question remains as to how Nelly will choose to proceed and the significance of this choice in her relation to her own history. As the doctor connects the anesthetic to Nelly’s arm, he asks that she count backwards, a “countdown” as he explains, a term supposedly coined by the Americans which in fact originated in Fritz Lang’s film WOMAN IN THE MOON (DE 1928). This bit of film history becomes all the more significant when considering that WOMAN IN THE MOON was also Lang’s last silent film of the Weimar era. His next film, M (DE 1931), was the first one to be made with sound. The latter was described by Lang himself as having brought about his political coming-of-age after which it became clear that as a Jewish artist in Germany there would be no place for him there. Much like Nelly’s dilemma or rather that of her surroundings as to why she would choose to return to Germany after the war, it is this procedure through which she will gradually move from silence and the inability to speak, to a slow regaining of language and the entrance into history, an entrance that according to Agamben holds ethical and therefore political implications. Returning to the notions of repetition and stoppage, we might therefore consider Dr. Bongartz’s repeated questioning and probing of what kind of identity Nelly would like to assume as significant markers in the scene in which there is pause or stop for consideration, reiterating or repeating each time the options through references to film history.

This scene exemplifies how film history serves to foreground the historical through emphasizing the break and discontinuity in the narrative that are caused by the anachronism of the protagonist’s situation. While not formally breaking into a montage that clearly demarcates the temporal transitions, this anachronism is weaved into the scenes through the renewed function of film history and how it is utilized as a trace of history. This trace does not fixate on the references in their original meaning but rather on how they come to bear the situation of the protagonist and the larger historical implications that her story is part of. The trace, as exhibited through the turning to film history, recalls former images and serves to re-archive both film and its historical role in the displacement of historical narrative.

Thus, Nelly’s face presents how the work of the cinematic medium links Nelly’s past to the dismantling of her identity, and this in turn is linked to the question of Jewish identity and the choice of identity in general in post-war Germany. As the film continues, the work of the medium in restructuring identity is gradually inverted in the attempted formation and ‘direction’ of Nelly by her former spouse that continues to draw on film history in realizing the process of Nelly’s ‘becoming historical’.

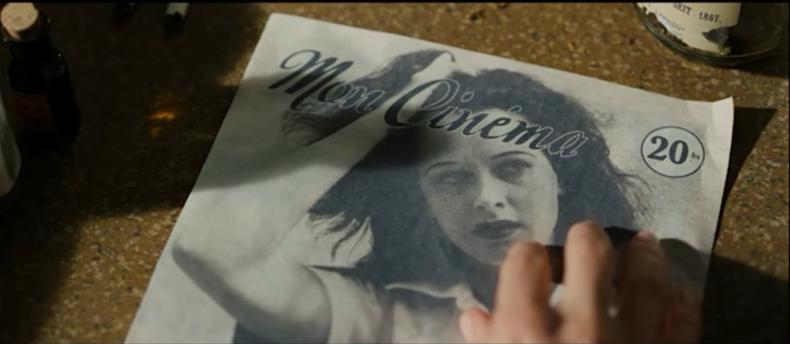

As Johnny attempts to give the ‘ghostly’ Nelly a makeover to resemble her former self, two particular instances that frame the interaction in this scene are significant. Johnny proposes that as part of her makeover Nelly dye her hair and apply make-up to resemble the woman on the cover of an entertainment magazine. In this brief yet definitive moment, the camera frames the magazine cover, producing a close-up on a woman’s face, only to reveal that the ‘actress’ whom Nelly is meant to model herself after is Hedy Lamarr, Austrian-born, Jewish émigré, whose own Jewish background in Hollywood was intentionally suppressed and set aside in order to be reborn as Golden-age Hollywood leading lady. Also known as ‘the most beautiful face in the world’, it is Lamarr’s silent image, peering directly in its wordless appeal that produces a gesture that is ‘pure’ mediality, relating identity, its disclosure as well as its suspension, and to a certain extent, elimination, as both a fracture in language, and as its suturing through the same form of ‘language’ that it has ruptured. This, again, is the language of film history interjected within a context that examines the mediation of historical events.

The prolonged and intentional focus on the unmistakable image of Lamarr, then, rupturing or stopping the sequential continuity of the scene just long enough to insert the image into the viewing frame of reference, situates Petzold’s film yet within another film historiographic trajectory. The scene links the erasure of female identity in the work of the medium to that of post-WWII German film and in this serves to re-mobilize the various histories and historiographies that have commonly bridged German film history and Hollywood cinema, as already suggested by Petzold through his visual and stylistic acknowledgments discussed above.

Since this close-up essentially encases Johnny’s ‘act of directing’, his attempt of creating a discourse of history, the film historiographies referenced throughout the film also appear in their existence as ‘languages’ through which history is written. Thus, the narrative continuity and form are dismantled by the very means of writing history only to realign them, extending the idea of the structuring that this writing entails. In other words, through the deconstruction of and subsequent restructuring of film historiography, using the close-up of Lamarr, Petzold breaks with conventional historiography to gesture at that which lies beyond the image.

Thus, the break of the form through the principles of montage, as exemplified in repetition and stoppage, produce the connected and ‘exacted’ traces as historical writing detached from the historical referent, only to create the historical through its exposure as a mediation. This mediation and connection are afforded by relying on what is exposed as writing — namely, film historiography. The past therefore surfaces through taking apart and then piecing together traces of film history, manifesting the potential of reading a film through the breaking of its narrative form as suggested by Russell. In this, the search for the historical as a mode of communication, beyond the image and beyond representation, might be considered as one possible way of what, to paraphrase Agamben, could be the light that perpetually voyages toward a new language of history.37

- 1This link to Benjamin and his understanding of historical writing has been addressed by Jaimey Fisher, among others, who also refers to the presence of Klee’s painting in this pivotal scene. See “Petzold’s Phoenix, Fassbinder’s Maria Braun, and the Melodramatic Archaeology of the Rubble Past,” Senses of Cinema 84 (September 2017).

- 2Ursula Scheer, quoted from an interview given by Petzold to Neue Zurcher Zeitung in 2018; see Ursula Scheer, “Things will not go well,” The German Times, March 2019, https://www.german-times.com/in-2018-german-screenwriter-and-director-c….

- 3Jaimey Fisher, Christian Petzold (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013), 1–9.

- 4A term coined by Eric Rentschler in reference to post-unification German cinema that sought to create consensus among German audiences rather than aesthetically or thematically challenge potential viewers. This notion, albeit the considerable successes of German films abroad from the 2000s onwards, has carried over to the most prominent and successful German films in foreign markets—such that engage with German history of the 20th century. While garnering significant success these films have been criticized for creating simplified and un-complicated versions of complex historical events. See Eric Rentschler, “From New German Cinema to the Post-Wall Cinema of Consensus,” in Cinema and Nation, eds. Scott MacKenzie and Mette Hjort (New York: Continuum, 2000), 260–277.

- 5For a discussion on the appropriation and meaning of the term ‘heritage films’ in the context of German historical film productions, see Lutz Koepnick, “Reframing the Past: Heritage Cinema and Holocaust in the 1990s,” New German Critique 87 (Autumn 2002): 47–82.

- 6Some examples to such popular productions include, among others, DOWNFALL (DE 2004), THE LIVES OF OTHERS (DE 2006), THE BAADER MEINHOF COMPLEX (DE 2008); Marco Abel, “Chapter 1,” in The Counter-Cinema of the Berlin School (Rochester: Camden House, 2013), Kindle.

- 7See, for example, interview with Petzold in Fisher, Christian Petzold, 147–167.

- 8Jaimey Fisher, “German Historical Film as Production Trend: European Heritage Cinema and Melodrama in The Lives of Others,” in The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and its Politics at the Turn of the 21st Century, eds. Jaimey Fisher and Brad Prager (Detroit: Wayne State U P, 2010), 186–215.

- 9While Fisher attributes this simplified mode of melodramatic storytelling to popular German historical productions of the past two decades, Petzold’s films have raised further scholarly debates in regards to the specific function of melodrama that is typical of his films. Wim Staat, for instance, reads PHOENIX in light of Stanley Cavell’s theory of film melodrama, especially the notion of the ‘unknown woman’, in which unacknowledged female desires are negotiated through public artifacts that attest not only to the personal moral dilemmas of the protagonists, but more importantly to social and historical dilemmas that extend the ethical implications of this negotiation indicated in the characters’ inability to feel at home. See Wim Staat, “Christian Petzold’s Melodramas: From Unknown Woman to Reciprocal Unknowness in Phoenix, Wolfsburg, and Barbara,” Studies in European Cinema 13, no. 3 (2016): 185–199.

- 10Fisher, “Petzold’s Phoenix, Fassbinder’s Maria Braun.”

- 11Walter Benjamin, “Theses on the Philosophy of History,” Illuminations, ed. Hannah Arendt, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken, 1968), 253–264.

- 12Fisher, Christian Petzold, 1–9.

- 13Although Kaütner’s film was shot in 1945 during the last days of the war, it was released only in 1946, at a time when films were once again being produced in Berlin’s Soviet sector. Kaütner’s film, despite having been disrupted by sirens and bombings at the time of shooting does not display any of the destruction that these reigned on the city, nor is it indicative of the regime under which it was produced. Instead, it is a film that examines the very possibility of love in a time of war, chaos and hate.

- 14For a comprehensive analysis that considers the film’s references to various literary, cinematic, cultural, and historical texts, see Brad Prager’s extensive study of the PHOENIX, in Brad Prager, Phoenix (Rochester: Camden House, 2019).

- 15Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, ed. Rolf Tiedemann (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999), 458.

- 16Catherine Russell, Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices (Durham: Duke University Press, 2018), 16.

- 17Russell, Archiveology, 20.

- 18Jaimie Baron, “Chapter 1,” in The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History (London and New York: Routledge, 2014), Kindle.

- 19Marianne Hirsch, The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust (New York: Columbia University Press, 2012); Alison Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory the Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004); Astrid Erll and Ann Rigney, “Introduction: Cultural Memory and its Dynamics,” in Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural Memory, eds. Astrid Erll and Ann Rigney, (Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2009), 1–14.

- 20See, for example, Paula Amad, Counter-Archive: Film, the Everyday, and Albert Kahn’s Archives de la Planѐte (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010); Ina Blom, Trond Lundemo, and Eivind Røossaak, eds., Memory in Motion: Archives, Technology, and the Social (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017); Trond Lundemo, “Archives and Technological Selection,” Cinémas 24, no. 2–3 (2014): 17–40.

- 21Russell, Archiveology, 1.

- 22Russell, Archiveology, 1.

- 23Georges Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms: Aby Warburg’s History of Art, trans. Harvey L. Mendelsohn (University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017).

- 24Didi-Huberman, The Surviving Image, 16.

- 25Russell, Archiveology, 11.

- 26Walter Benjaimin, The Origin of German Tragic Drama, trans. John Osborne (London: NLB/Verso, 1977).

- 27Giorgio Agamben, “What is a Contemporary?” in What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays, translated by David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2009), 39–54.

- 28Giorgio Agamben, Infancy and History: The Destruction of Experience, trans. Liz Heron (London: Verso, 1993).

- 29Alysia Garrison, “History/ Historicity,” in The Agamben Dictionary, eds. Alex Murray and Jessica Whyte (Edinburg: Edinburgh University Press, 2011), 92–93.

- 30Russell, Archiveology, 165.

- 31Giorgio Agamben, “Notes on Gesture,” in Means without End: Notes on Politics, trans. Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino, (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000), 55.

- 32Giorgio Agamben, “Difference and Repetition: On the Films of Guy Debord, ” trans. Brian Holmes, in Guy Debord and the Situationists, ed. Tom McDonough (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2002), 313–320.

- 33Alysia Garrison, “History/ Historicity,” 93.

- 34Agamben, “What is a Contemporary?” 42.

- 35See Jaimey Fisher’s discussion regarding the influence of NOSFERATU on Petzold in Christian Petzold, 81–82.

- 36The ethical aspect that Agamben sees as inherent in considering film as gesture maintains that any aesthetic form serves as an opening form of communication rather than constricting it to a specific and limited meaning. In this respect, the discussion of how PHOENIX approaches the past raises a number of crucial concerns regarding the continuation of Holocaust remembrance. Such concerns are exemplified in Dora Osborne’s understanding of PHOENIX as a film that thematizes the work of archiving as both an intra-diegetic and extra-diegetic task that she detects in the different works of archiving that are carried out by the characters, implemented in how they try to either recreate or trace the past. Since any attempt to either trace or reproduce this particular past essentially disavows the possibility of providing a representational space for the trauma, PHOENIX is a film that “stages the particular problems of archive work after Auschwitz” (193). Conversely, Ruth Jennifer Hosek draws on PHOENIX, as well as other films by Petzold, in order to raise the issue of contemporary European films exhibiting a ‘postmigrant aesthetics’, that is to say, as films that point toward gaps in the notion of a utopian and hegemonic postmigrant Europe that continually masks racism, fascism and xenophobia. See Dora Osborne, “Too Soon and Too Late: The Problem of Archive Work in Christian Petzold’s Phoenix,” New German Critique 139, 47, no. 1 (February 2020): 173–195; Ruth Jennifer Hosek, “Towards a European Postmigrant Aesthetics: Christian Petzold’s Transit (2018), Phoenix (2014), and Jerichow (2008),” Transit 13, no. 1 (2021): 52–70, doi:10.5070/T713153425.

- 37Agamben, “What is a Contemporary?” 47.

Abel, Marco. The Counter-Cinema of the Berlin School. Rochester: Camden House, 2013. Kindle.

Agamben, Giorgio. “Difference and Repetition: On the Films of Guy Debord.” In Guy Debord and the Situationists International: Texts and Documents, edited by Tom McDonough, translated by Brian Holmes, 313–320. Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2002.

Agamben, Giorgio. Infancy and History: The Destruction of Experience. Translated by Liz Heron. London: Verso, 1993.

Agamben, Giorgio. “Notes on Gesture.” In Means without End: Notes on Politics. Translated by Vincenzo Binetti and Cesare Casarino, 48–59. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

Agamben, Giorgio. “What is a Contemporary?” In What is an Apparatus? and Other Essays. Translated by David Kishik and Stefan Pedatella, 39–54. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2009.

Amad, Paula. Counter-Archive: Film, the Everyday, and Albert Kahn’s Archives de la Planѐte. New York: Columbia University Press, 2010.

Baron, Jaimie. The Archive Effect: Found Footage and the Audiovisual Experience of History. London and New York: Routledge, 2014. Kindle.

Benjamin, Walter. The Arcades Project, edited by Rolf Tiedemann. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1999.

Benjamin, Walter. The Origin of German Tragic Drama. Translated by John Osborne. London: NLB/Verso, 1977.

Benjamin, Walter. “Theses on the Philosophy of History.” In Illuminations, edited by Hannah Arendt, translated by Harry Zohn, 253–264. New York: Schocken, 1968.

Blom, Ina, Trond Lundemo, and Eivind Røossaak (eds.). Memory in Motion: Archives, Technology, and the Social. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2017.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. The Surviving Image: Phantoms of Time and Time of Phantoms-Aby Warburg’s History of Art. Translated by Harvey L. Mendelsohn. University Park, Pennsylvania: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2017.

Erll, Astrid and Ann Rigney. “Introduction: Cultural Memory and its Dynamics.” In Mediation, Remediation, and the Dynamics of Cultural Memory, edited by Astrid Erll and Ann Rigney, 1–14. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 2009.

Fisher, Jaimey. Christian Petzold. Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

Fisher, Jaimey. “German Historical Film as Production Trend: European Heritage Cinema and Melodrama in The Lives of Others.” In The Collapse of the Conventional: German Film and Its Politics at the Turn of the 21st Century, edited by Jaimey Fisher and Brad Prager, 186–215. Detroit: Wayne University Press, 2010.

Fisher, Jaimey. “Petzold’s Phoenix, Fassbinder’s Maria Braun and the Melodramatic Archaeology of the Rubble Past.” Senses of Cinema 84 (September 2017).

Garrison, Alysia. “History/ Historicity.” In The Agamben Dictionary, edited by Alex Murray and Jessica Whyte, 92–93. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2011.

Hirsch, Marianne. The Generation of Postmemory: Writing and Visual Culture after the Holocaust. New York: Columbia University Press, 2012.

Hosek, Jennifer Ruth. “Towards a European Postmigrant Aesthetics: Christian Petzold’s Transit (2018), Phoenix (2014), and Jerichow (2008).” Transit 13, no. 1 (2021): 52–70. http://doi.org/10.5070/T713153425.

Koepnick, Lutz. “Reframing the Past: Heritage Cinema and Holocaust in the 1990s.” New German Critique 87 (Autumn 2002): 47–82.

Landsberg, Alison. Prosthetic Memory the Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

Lundemo, Trond. “Archives and Technological Selection.” Cinémas 24, no. 2–3 (2014): 17–40.

Osborne, Dora. “Too Soon and Too Late: The Problem of Archive Work in Christian Petzold’s Phoenix.” New German Critique 139, vol. 47, no. 1 (February 2020): 173–195.

Prager, Brad. Phoenix. Rochester: Camden House, 2019.

Rentschler, Eric. “From New German Cinema to the Post-Wall Cinema of Consensus.” In Cinema and Nation, edited by Scott MacKenzie and Mette Hjort, 260–277. New York: Continuum, 2000.

Russell, Catherine. Archiveology: Walter Benjamin and Archival Film Practices. Durham: Duke University Press, 2018.

Scheer, Ursula. “Things will not go well.” The German Times, March 2019. https://www.germantimes.com/in-2018-german-screenwriter-and-director-ch…

Staat, Wim. “Christian Petzold’s Melodramas: From Unknown Woman to Reciprocal Unknowness in Phoenix, Wolfsburg, and Barbara.” Studies in European Cinema 13, no. 3 (2016): 185–199.