Reflections on the Geography of the Holocaust Based on Soviet Film Footage

The Cases of Kremenets and Vyshnivets (July 1944)

Table of Contents

Soviet Film Footage and Professional Practices (1941–1945)

Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis')

A Travelling Archive

Zinovii Tolkachov’s Graphics from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek Death Camps

People with Disabilities as Nazi Victims on Screen and Paper

Forgotten: Film Documents from the Liberated Camps for Soviet POWs

Depicting Atrocities

Reflections on the Geography of the Holocaust Based on Soviet Film Footage

Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv

Filming Auschwitz in 1945: Osventsim

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Moutier-Bitan, Marie. “Reflections on the Geography of the Holocaust Based on Soviet Film Footage: The Cases of Kremenets and Vyshnivets (July 1944).” Research in Film and History 6 (2025): 1–24. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/23565.

“There are no Jews in Ukraine. […] All is silence. All is peaceful. An entire people has been savagely massacred.”1 When Vassili Grossman wrote these lines in the autumn of 1943, Kharkiv, Poltava, Kremenchuk, Donetsk and other towns and cities east of the Dnieper had been liberated. Soviet camera operators filmed ruins and corpses, documenting the scale of devastation and emptiness of the murderous, genocidal Nazi occupation.

The Visual History of the Holocaust project (EU Horizon 2020 project, coordinated by the Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Digital History, Vienna) has developed a platform where researchers can access this footage, most of which has been preserved at the RGAKFD (Российский государственный архив кинофотодокументов, Russian Archive of Film and Photographic Documents) in Krasnogorsk. The platform was the topic of an international symposium held in Paris in November 2022.2

Several recent studies have investigated the conditions in which the footage was created.3 The details unearthed in these studies are crucial to understanding a source of evidence that has until now often been neglected in histories of the Holocaust. The Soviet filming concentrated on locations that were significant in terms of the number of victims or types of methods. The resulting footage has been used by Holocaust historians such as Stuart Liebman (as a source on the Majdanek concentration camp4) and Karel Berkhoff (who meticulously analysed footage shot at Babyn Yar to understand the topography of the site and reconstruct the geography of the massacres5). Footage shot after the liberation of the territories can help to compensate for changes in the physiognomy of the execution sites as we know them eighty years later.

However, some visual materials, including many photographs or films from Eastern Europe, suffer from a lack of geographical context, making it virtually impossible to integrate them into other documents of the Holocaust. Some caption sheets are missing, others are too imprecise (for instance, only naming a region) or contain inaccuracies.

This footage nonetheless represents a crucial resource: it shows spaces a few weeks or months after the mass murder of the Jewish population, in the context of a war of annihilation and colonisation. Our aim here is to show that it is possible, using a variety of tools (maps, TchGK investigations, neighbours’ testimonies, GPS readings during field surveys), to identify places and so allow these visual materials to be used to document the Shoah in Eastern Europe and open up new avenues of research.

Identifying Space

We chose to analyse a few minutes of a film preserved at the RGAKFD under the title TRAGEDY OF TWO CITIES / ТРАГЕДИЯ ДВУХ ГОРОДОВ, file number 10855. It was shot in July 1944 in two towns that were historically located in the province of Volhynia but were later administratively attached to the Ternopil oblast. When this footage was recorded by Aleksandr Efimovich Vorontsov and Grigory A. Mogilevsky, it had been over a year since the ghettos of the “Generalbezirk Wolhynien und Podolien“ had been liquidated. It is estimated that less than five per cent of the territory’s Jewish population survived the Nazi occupation. When Vorontsov and Mogilevsky surveyed Kremenets and Vyshnivets in the July sun of 1944, it had been at least a year and a half since the Jews of these two towns had been murdered. They now lay in mass graves on the towns’ outskirts. Just like in the rest of the Generalbezirk, the ghettos were liquidated in autumn 1942. We know this story through the investigations of the Soviet Extraordinary State Commission (TchGK),6 whose work can be seen in some of the footage of the exhumations, as well as through the post-war depositions of Nazi criminals responsible for the killings,7 the testimonies of the small number of Jewish survivors8 and interviews with Ukrainian residents of Kremenets and Vyshnivets.9

Film 10855 is raw footage without sound, comprising thirty-two shots. The first (frames 1 to 252) is a tracking shot of a small town in the countryside, the next seven show urban spaces and then the final twenty-four are of exhumations. The RGAKFD caption sheet for film 10855 indicates the location and date of shooting: “Ukrainian SSR, Ternopil region, towns of Kremenets, Vyshnivets, July 1944. Destroyed buildings in the streets of Kremenets. View of a passing car. The roof of a house, pierced by a shell. A woman walks among the bricks of a destroyed house.“ The rest of the description refers to the exhumations that appear in the second part of the film.

The information on the sheet is inadequate: it does not specify which town is shown on each shot. Moreover, at no point does the description provided by the RGAKFD mention that the exhumed victims were Jewish or that the destruction was linked to the process of genocide. So how can this footage be used as a source of information about the Holocaust? Shots 4 (frames 801 to 985) and 5 (frames 986 to 1148) were included in the film DESTRUCTION MADE BY THE GERMANS IN THE TERRITORY OF THE SOVIET UNION, which was screened at the Nuremberg trials on February 22, 1946. In that film, the voice-over simply announces the name of the town: “Vyshnivets.“ What all the footage has in common is that it shows remnants of neighbourhoods or buildings that have been destroyed, reduced to ash, demolished or gutted by bombs. The destruction in Smolensk and the rubble in Vyshnivets are presented without clearly distinguishing between them, which can make it hard to reliably glean information from the footage. It is therefore imperative to precisely and irrefutably identify the locations shown in the film.10

We were able to pinpoint the locations by comparing disparate visual materials: an 1891 Russian military map outlining the relief;11 a map drawn from memory by a former Vyshnivets resident, Moshe Segal;12 and photographs by Henryk Poddębski, Józef Dutkiewicz and Jan Bułhak from the mid-1920s and early 1930s. Testimonies from former Jewish residents in books of remembrance and from Ukrainian neighbours that were collected by Yahad – In Unum in 2009 and 2019 also provided some clues (GPS coordinates, mentions of places such as the Shevchenko statue and the present-day police station).

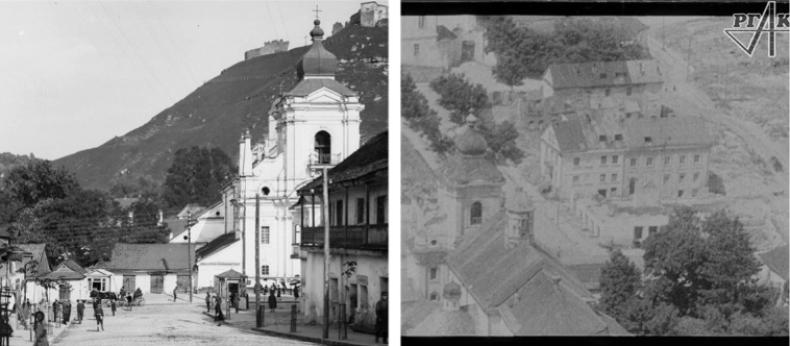

Two buildings can be identified in the footage. The second shot (frames 253–534) begins with a bird’s-eye view of a church: the Franciscan monastery of Kremenets. This travelling shot was taken from above from the Kremenets fortress, which can be seen in a prewar photograph (Figure 1).

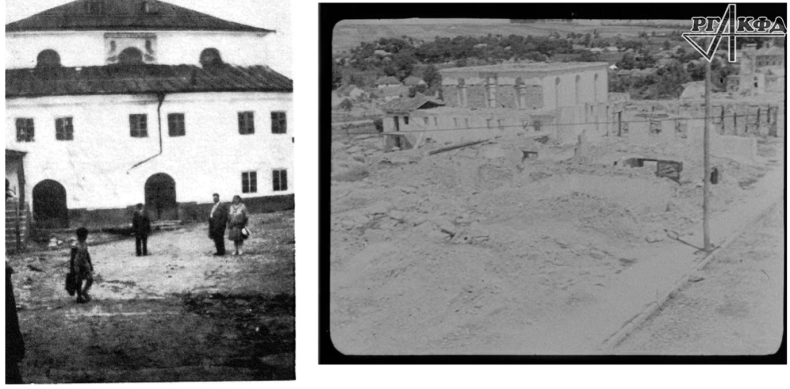

The third shot (frames 535–800) switches to a new location without any transition. The climatic conditions seem to be the same, and the architecture of the buildings still standing in the streets is similar. Some identifiable sections of wall amidst the ruins confirms the change of location: this is a travelling shot taken in Vyshnivets, showing the Great Synagogue (frame 721, Figure 2). Thanks to the identification of the Vyshnivets synagogue and topographical research conducted by the Yahad – In Unum team in this town in 2019, it is also possible to recognise the mill, some 350 metres away. The location of the camera for shot 3 (frames 535 to 800) can then be precisely pinpointed to the intersection between the “boulevard“13 (north–south axis) and Third of May Street14 (east–west axis) (Figure 3).

Shots 4, 6 and 7 show either the synagogue or the Vyshnivets mill, and are thus easily identifiable. However, neither of these buildings can be seen in shot 5. The shadows of the buildings in shot 5 suggest that the facades are facing east, along an axis running from north to south, like the “boulevard.“ A woman dressed in a dark top, light skirt and white scarf walks up the street (shot 5): she is the only person who appears in these scenes of the town’s destruction. She looks similar to the woman rummaging through the rubble in shot 8, but we cannot be sure it is the same person.

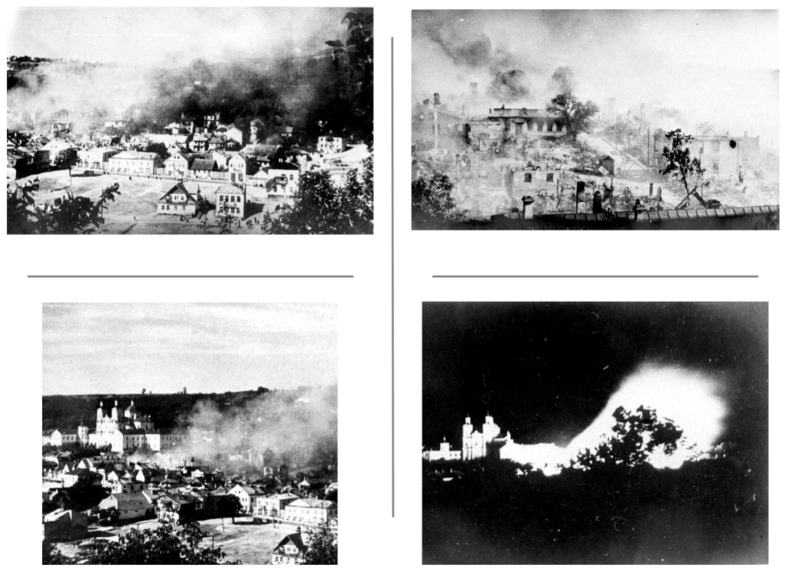

The footage shows two entire Jewish neighbourhoods that have been destroyed and reduced to rubble. This devastation requires contextualisation of the devastation. Without the support of archives and testimonies, there would be a risk of interpreting these ruins as collateral damage from armed confrontations or intense shelling by the German army, in pursuit of a global policy of annihilation of the Soviet Union. But in fact the destroyed neighbourhoods shown in film 10855 were a product of the genocide of Jews in the occupied territoryThis confusion also applies to a series of photographs preserved at Yad Vashem, which were originally thought to show an aerial bombardment of Kremenets, whereas in fact they show a fire in the ghetto.15 A note has been added to photograph YVA 2656/62, probably on the initiative of Iryna Danylyuk, which explains that it actually shows the liquidation of the Kremenets ghetto in August 1942.

Kremenets

Shot 2, filmed from the fortress, offers a bird’s-eye view of a completely destroyed central district. Only our knowledge of the town’s prewar geography, based on the testimonies of former residents, both Jewish and non-Jewish, enables us to identify it as the Jewish quarter, which later became the ghetto and was then liquidated in August 1942 (Figure 4).

In June 1941, there were around 12,000 Jews living in Kremenets, which was more than a quarter of the town’s population.16 The first massacres of Jews began a few hours after the arrival of the Germans on 3 July 1941, when a pogrom broke out that claimed around 130 Jewish victims.17 At the end of July, several hundred Jewish intellectualswere shot.18 The synagogue was set on fire at the end of July, after having been looted and ransacked.19 On 1 March 1942, a ghetto was created on a long strip of land surrounded by a wooden fence.20 The conditions in the ghetto were appalling, with people dying daily from hunger. Humiliating orders and abuses by Gebietskommissar Müller led to a reign of terror.21 The liquidation of the ghetto, which was orchestrated by Müller and the Sipo/SD unit, began on 10 August 1942. The process took several weeks, since the perpetrators found Jews living in hiding. On the first day, around 5,000 Jewish men, women and children were shot in trenches outside the town, behind the barracks known as the Yakutski firing range.22 Almost 9,000 Jews were murdered during the liquidation, which ended with the burning of the ghetto on 2 September 1942.23

Shmuel Spector, an expert on the Volhynia Holocaust, expressed uncertainty about the origin of the fire in the Kremenets ghetto:24 did the internal resistance deliberately set fire to the dwellings in order to confuse the German perpetrators and their auxiliaries when the ghetto was liquidated on 10 August 1942? Or was it a German tactic to force the Jews out of their hiding places, as rumoured among the local Ukrainian population?25 On 2 September 1942, a Russian teenager who lived in Kremenets and was a friend of a Jewish girl who had been shot a few weeks earlier wrote in his diary:

Around 3 a.m., around 400 houses went up in flames, but now only a quarter of them are still standing. A motor pump has been working non-stop since early morning to fetch water from the river. But what can a single motor pump do? A fire department has come from Dubno, and it is even said that another one has come from Rovno, but they haven’t been able to do anything yet either. The fire was undoubtedly set by the Jews themselves, and the arson was obviously very well planned, and the weather today is also extremely favourable. Yesterday there was an unexpectedly strong wind, with the clearest sky, there was an easterly wind […]. When I was woken up again by gunshots, the sky was glowing red and thick clouds of smoke were rising. I immediately realised what was going on, I was secretly happy and went back to sleep.26

Whatever the cause of the fire – whether it was set by Jewish inmates of the ghetto or by the men of the Sipo/SD to drive the Jews from their hiding places – the desolate expanse that it created is evidence of Jewish resistance to extermination. Following rumours that circulated about the operations conducted in the surrounding ghettos, the Jews of Kremenets organised themselves and built bunkers. Ranging from crude dugouts to proper underground installations, these enabled them to survive for several days.27

The liquidation of the ghetto began on 10 August 1942, and the ghetto was burnt down on 2 September 1942. The men of the Sipo/SD and the Ukrainian police of the Schutzmannschaft were unable to arrest all the Jews in the ghetto during those three weeks in August. The ghetto fire killed the last people hiding inside.28 Whether intentionally or not, the shot of the ruins of Kremenets in the film illustrates the specificity of Nazi violence against Jews: genocidal, total and confined to the Jewish population alone. Firefighters were mobilised to manage the ghetto fire – not to extinguish it, but to prevent it from spreading to non-Jewish dwellings (Figure 5).29 There were only around fifteen Jewish survivors from Kremenets.30

The shot illustrates the dichotomy between the annihilation of the town’s Jewish population, and the continuation of life as normal on and around the town’s other thoroughfares. In the film, the contrast between full and empty is striking. There is an unbearable gulf between the ghetto and the rest of the town: “The Christian inhabitants outside the ghetto continued their normal lives as if nothing had happened.“31 Once the ghetto had been reduced to ash, the meagre possessions of the Jewish victims were transferred from the town to the countryside:

Organized looting continues in the ghetto. Old women with brooms keep watch around the clock. What people, what people! What heroes! They are shot at, arrested, beaten. But none of that bothers them. Wherever there is a hint of profit, nothing can hold them. Men from remote villages come to the ghetto, and hardly any of them now walk around without a watch.32

A similar transfer of Jewish property from the town to the countryside also occurred in the neighbouring town of Vyshnivets, leaving a highly visible mark on the town centre.

Footage of the Holocaust in Vyshnivets

Around 4,000 Jews lived in Vyshnivets on the eve of Operation Barbarossa.33 Like Kremenets, the town was situated on the border of two historical provinces, Volhynia and Eastern Galicia. Its population was made up of Poles, Ukrainians and Jews. The town is split across both banks of the River Horyn. the crossing is extremely hazardous or even deadly for those who cannot swim. The town centre is on the north bank of the river in Novyi Vyshnivets, while the old town is on the south bank in Stary Vyshnivets, where the Catholic church of St Stanislaus is located. Opposite, the Vyshnivets Palace, once owned by a Polish noble family, the Wiśniowieckis, overlooks the steep valley. The Jewish quarter was located in the suburb of Novyi Vyshnivets, clustered along the shopping streets and around the large white building of the Great Synagogue,. Other prayer houses and a small cemetery were located nearby. The newer Jewish cemetery was nestled on a hill to the north of the town. Jews also lived in Staryi Vyshnivets.34 A Ukrainian resident of Vyshnivets described the town centre as follows:

The Jews, those who were a little richer, had stores […] those who had less money went to people’s homes to glaze windows, for example […] They were carpenters, dressmakers […]. The richest owned stores, boutiques […] for example, in the centre of Vyshnivets, there were only their stores! This area was occupied by Jews.35

Lidia B., born in 1932, was interviewed in 2009 as part of Yahad – In Unum’s study. The arrangement she describes was a typical distribution of socioeconomic space in western Ukraine: a strong Jewish presence in the town centre with a high concentration of commercial professions.

In March 1942, the German authorities set up a ghetto along the street beside the River Horyn. It was surrounded by railings, except for the side overlooking the river. This meant that the Great Synagogue was outside the ghetto. The ghetto lasted only a few months: on 11 and 12 August 1942, a Sipo/SD unit from Kremenets, with the support of local collaborators, organised the murder of over 2,600 Jewish men, women and children. The shootings took place outside Staryi Vyshnivets, close to the road leading to Zbarazh. The executions of the survivors, who had mainly hidden in bunkers, took place in November 1942.36 We know that the ghetto was completely destroyed, perhaps to ensure there were no possible hiding places remaining. However, it is not the ghetto that appears in the later film, but the old Jewish quarter around the synagogue, one of the few buildings (along with the mill) that was still left standing amid the rubble in July 1944. The ghetto ran along the central street; the area of the ghetto does not appear in the footage, as the camera stops at the edge of the street, perhaps to avoid direct sunlight. We can only make out a few shadows, suggesting that the facades were few and far between, which confirms the destruction of the ghetto’s dwellings.

A travelling shot from frames 535 to 800 (see for instance frame 719, Figure 6) shows a completely empty space around the ruins of the synagogue. A Polish postcard from the 1920s or 1930s shows a densely populated neighbourhood clustered around the synagogue. The former site of those houses can be found to the north of the synagogue, shown in red on frame 719: all that remains is rubble. Henryk Poddębski’s 1924 photograph (frame 758) shows the area east of the synagogue; by July 1944, these houses had been completely destroyed (Figure 7). According to Moshe Segal’s map, this neighbourhood included several synagogues, as well as a small cemetery adjacent to the Great Synagogue. There was also the Tarbut school and the Hekdesh, a hospicefor the poor.

The Jewish quarter of Vyshnivets was almost completely destroyed. By comparing three kinds of visual material (photographs, films and postcards), we can understand the scale of the destruction that occurred during the Nazi occupation. This highlights the materiality of the Holocaust and raises the question of what became ofJewish victims’ property.

The images of the ruins in Vyshnivets are disconcerting. The viewer might attribute the rubble to German military destruction. A few houses bear marks of fire, but most buildings seem to have been reduced to rubble. One house appears to have been ransacked rather than destroyed (frame 1363): there are no marks of fire or bombs, but the doors, windows and furniture are gone. The house next door (frame 1406) has no roof, windows or doors. The same applies to the Great Synagogue: the windows, roof and doors are gone. However, the walls and the small adjoining house are intact. Did the devastation of the ghetto spill over into the town centre? According to the TchGK investigation, the testimonies of the very few Jewish survivors and interviews with Ukrainian residents, there was no targeted operation to destroy this district, by contrast with the site of the ghetto after its liquidation in November 1942 (mentioned in a single line in the TchGK report).37

The field studies conducted by Yahad – In Unum in 2009 and 2019 provide some insight into the devastation of Jewish homes in the town centre. A Ukrainian resident of Vyshnivets, Vasili C., born in 1927, explained: “The poorest Jewish houses were destroyed and burned; the richest houses by the town hall were sold“;38 this probably happened after the massacre. Another neighbour claimed that the Ukrainians received permission from the German authorities to dismantle Jewish homes: “We were taking! […] Anyone who wanted to, they went and took! We tore up the floors […] we took all the furnishings! People took what they wanted! […] Those who wanted the floor, tore it out and took the planks!“39 Another testimony confirms the looting of building materials from Jewish homes.40 Anton Z.’s uncle set up his photography studio in a former Jewish house.41 This dismantling would explain the state of the houses, which were reduced to piles of stones. In the nearby town of Kremenets, the German Gebietskommissar Müller ordered the dismantling of Jewish houses outside the ghetto; all the material recovered was sold to local farmers.42

The synagogue and mill escaped full demolition, though the former was looted. This can be explained by the fact that these were official buildings that fell outside local residents’ control. In western Ukraine and other Soviet regions previously occupied by the Nazis, the synagogues still standing were transformed into public buildings, such as warehouses, clubs or prisons. This is what happened to the Great Synagogue of Vyshnivets in the 1950s.

With the exception of the silhouette of a woman walking along a bare facade and another woman (or perhaps the same one) rummaging through debris, the town’s streets are empty, bathed in the bright light of the hot July sun. The orientation of the shadows indicates that this footage was shot around midday or in the early afternoon. Is the absence of people in the streets an aesthetic choice, to emphasise the idea of total destruction, both material and human?

Whether it was intentional or not, the emptiness of these images raises the question of the reconfiguration of space, and in particular of socioeconomic space. The absence of passers-by in the streets may have been orchestrated for filming purposes, but the gaping hole in the town centre is very real. It had been a year and a half since the last Jews in Vyshnivets were murdered. How can we explain this pile of rubble still being there so long after the massacre?

The reconfiguration of space in Vyshnivets was slow: not only had the Jewish population been massacred, but so had many of the Polish inhabitants, while the rest had left. By July 1944, all that remained of the June 1941 population were Ukrainians and a handful of other “nationalities.“ The Ostarbeiter, who were still in forced labour camps in the German Reich, must be subtracted from this Ukrainian population. In addition, the majority of Ukrainian inhabitants of Volhynia and Eastern Galicia were farmers living in the countryside. Building materials taken from Jewish homes were used to construct farms out in the villages. One farmer removed all the bricks and other materials from Samuel Greenberg’s house to rebuild his own, which had accidentally burned down.43 Simche Boytener, who visited Vyshnivets in early 1944 after the arrival of his Red Army regiment in Kremenets, also noted the misappropriation of Jewish sacred objects: “I also saw entryway steps made of Jewish gravestones. I saw floor coverings and boots made of parchment from the Torah scrolls.“44

Two former Jewish residents of Vyshnivets visited the town in 1956. M. Malev, who had survived the Holocaust in Volhynia, struggled to recognise his hometown:

Our house and Yakov Chachkis’s house, which were next to the rabbi’s, were gone. All the ghetto streets were destroyed, and their buildings completely leveled. […] The town center had been completely plowed under, and a town park had been planted there. Several buildings that were still standing were occupied by Ukrainians who had collaborated with the Germans. In the space where Shapiro’s home once stood, Ostrovski, the well-known piglet, built a mansion using bricks he collected from destroyed Jewish homes. The Lerners’ house had completely sunk into the ground. I don’t have any idea how it happened. Its windows were shattered and covered with wooden planks. It’s not habitable, but a Ukrainian from the area lives there.45

The synagogue and the mill were the two buildings that enabled Chayim Korin to recognise Vyshnivets in 1956 – and that enabled us to identify the films:

Finally, I arrived in Vishnevets. I was there for a few days, but I couldn’t take more than that. The town had been destroyed, life had been pulled from its roots, Jewish life had disappeared, and our loved ones were gone. […] I took my handkerchief off, and I really didn’t know where I was standing. I turned around, shocked and confused, until I saw the flourmill still standing in its place. Only then did I know I was in my hometown, the town that no longer existed. Only a few buildings remained standing in Vyshnivets. The Great Synagogue remained and was being used as the district prison.46

The reconfiguration of socioeconomic space is a slow process. The town centres were not being filled by the surrounding rural population, who continued living closer to the fields and pastures. In Boremel, another Volhynian town further north, some of the houses in the town centre where Jewish people had formerly lived were rented out to doctors and teachers, who had clearly come from elsewhere; many others were dismantled to meet the need for combustible materials.47 In Zboriv, south-west of Vyshnivets, a few Jewish houses were allocated by the Soviet authorities to Ukrainians who had been relocated from Poland, but most were destroyed.48 This difficulty in repopulating Jewish districts in the town centres illustrates the central socio-professional role played by Jews in the local and regional economy in the provinces of Volhynia and Eastern Galicia, where professions were segregated by nationality or religion, directly corresponding to the Russian Empire’s restrictions on access to property and other rights.

Conclusion

The film we have analysed here strengthens the case for including the chronology of post-genocidal spaces in the history of the Shoah. The footage of the razed Jewish quarters of Vyshnivets and Kremenets document both the spatial settlement of Jews in cities and towns before the Nazi occupation and their socioeconomic role, which was difficult to replace after their annihilation. It also bears witness to the material aspect of the genocide: looting and dispersal of Jewish property, and destruction of Jewish homes. The term “destruction“ needs to be reconsidered: we should instead speak of demolition, dismantling or even disguising of property that formerly belonged to Jews. Do we dismantle what cannot be reclaimed? The looting operations, which began long before the murder of the Jewish victims, tore apart Jewish properties. Stones, bricks, planks and tiles from Jewish homes were dispersed among a multitude of farms in the surrounding area. The result was a dilution of individual responsibility within a collective movement.

The Soviet footage invites us to critically question these acts of destruction and to sketch out a typology: by whom, when and under what circumstances were Jewish quarters and ghettos destroyed in the occupied Soviet Union? As we have seen, though the ruins of Kremenets and Vyshnivets are similar and the result (an entire district razed to the ground) the same, the circumstances of the devastation were quite different.

The film of Vyshnivets and Kremenets preserves the last trace of Jewish life before it was hidden by the geographical and economic reconfiguration of space, and also the last trace of the murder of the towns’ Jewish inhabitants – men, women and children. This footage is all the more important because it fills a void: it captures for posterity the landscapes of the Shoah, several months or weeks after the last Jewish communities were killed, and makes the public nature of this genocide, anchored in everyday space, even more palpable.

- 1

Vassili Grossman, Carnets de guerre: De Moscou à Berlin, 1941–1945 (Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 2007), 281.

- 2

On the nature of the films and rushes, see Valérie Pozner’s article in this issue: “Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis),” Research in Film and History 6 (2025): 1–27.

- 3

Valérie Pozner, Alexandre Sumpf, Irina Tcherneva and Vanessa Voisin, eds, Filmer la guerre: les Soviétiques face à la Shoah 1941–1946 (Paris: Mémorial de la Shoah, 2015); Jeremy Hicks, First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946 (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012); Irina Tcherneva, “Historiciser les images soviétiques de la Shoah (Estonie, Lituanie, 1944–1948),“ Vingtième Siècle: Revue d’histoire 139, no. 3 (2018): 59–78.

- 4

Stuart Liebman, “Les premiers films sur la shoah: les Juifs sous le signe de la Croix,“ Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah 195, no. 2 (2011): 145–179.

- 5

See: Karel Berkhoff, “Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv,” Research in Film and History 6 (2025): 1–28.

- 6

The investigations of Vyshnivets and Kremenets can be found in GARF 7021-75-3 and 7021-75-6.

- 7

Bundesarchiv Ludwigsburg, BArch B162-7493 to B162-7495.

- 8

In particular, the Holocaust testimony of Samuel Greenberg, 10 January 1984, USHMM, RG-50.462.0281.

- 9

Yahad – In Unum researchers made eighteen trips to Ukraine in 2009 and sixty in 2019.

- 10

USHMM, RG-60.6953, ID 4289.

- 11

Scale 1:25,000.

- 12

The sketch can be found in Chayim Rabin, ed., Sefer Vishnivits: Sefer zikaron likedoshei Vishnivits shenispu besho’at hanatsim (Tel Aviv: Organization of Vishnevets Immigrants, 1970).

- 13

This is how the north–south axis is referred to in Moshe Segal’s sketch.

- 14

Name of the east–west axis during the Republic of Poland (1921–1939).

- 15

The erroneous captions may have come from the Polish Commission for the Investigation of Crimes Committed against the Polish Nation (Główna Komisja Badania Zbrodni przeciwko Narodowi Polskiemu), which donated the photographs to Yad Vashem.

- 16

Martin Dean, ed., The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945: Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe,vol. 2 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012), 1394–1397.

- 17

Ereignismeldungen UdSSR no. 28, 20 July 1941.

- 18

GARF 7021-75-6.

- 19

Diary of Roman Aleksandrovitch Kravtchenko, Kremenets, 26 July 1941, KRKM, LKM-i-8570/7695/1.

- 20

Aleksandr Kruglov, Katastrofa ukrainskogo evreistva 1941–1944 gg.: Entsiklopedicheskii spravochnik (Kharkiv: Karavella, 2001), 173–174.

- 21

Betsalel Shvarts, “Ghetto Martyrology and the Destruction of Kremenets,“ in Pinkas Kremenets: sefer zikaron, ed. Abraham Samuel Stein (Tel Aviv: Hotsaʼat Irgun ole Ḳremnits be-Yiśraʼel, 1954), 416– 435.

- 22

GARF 7021-75-6.

- 23

Dean, Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1394–1397.

- 24

Shmuel Spector, The Holocaust of Volhynian Jews, 1941–1944 (Jerusalem: Yad Vashem and the Federation of Volhynian Jews, 1990), 220–223.

- 25

Interview with Viktor F. in Stary Vyshnivets, 10 July 2019, YIU/2618U.

- 26

Diary of Roman Aleksandrovitch Kravtchenko, Kremenets, 9 February 1942, KRKM, LKM-i-8570/7695/1.

- 27

Betsalel Shvarts, “The Holocaust,“ in Pinkas Kremenets: sefer zikaron, ed. Abraham Samuel Stein (Tel Aviv: Hotsaʼat Irgun ole Ḳremnits be-Yiśraʼel, 1954), 234.

- 28

Ibid.

- 29

Some pictures may have been taken by Henryk Hermanowicz, but they might instead have been taken by German soldiers; we do not have further information.

- 30

Tova Teper-Kaplan, “The Story of the Extermination,“ in Pinkas Kremenets: sefer zikaron, ed. Abraham Samuel Stein (Tel Aviv: Hotsaʼat Irgun ole Ḳremnits be-Yiśraʼel, 1954), 251.

- 31

Shvarts, “The Holocaust,“ 234.

- 32

Diary of Roman Kravtchenko, 18 September 1942. Gold objects, such as fire-resistant coins, were particularly sought after.

- 33

Dean, Encyclopedia, 1493.

- 34

Interview with Anton Z. in Stary Vyshnivets, 10 July 2019, YIU/2613U.

- 35

Interview with Lidia B. in Vyshnivets, 15 May 2009, YIU/842U.

- 36

GARF 7021-75-3.

- 37

GARF 7021-75-3.

- 38

Interview with Vasili C. in Vyshnivets, 15 May 2009, YIU/839U.

- 39

Interview with Aleksandr J. in Vyshnivets, 15 May 2009, YIU/840U.

- 40

Interview with Mikhayl D. in Vyshnivets, 15 May 2009, YIU/841U.

- 41

Interview with Anton Z. in Stary Vyshnivets, 10 July 2019, YIU/2613U.

- 42

Shvarts, “The Holocaust,“ 234.

- 43

Holocaust testimony of Samuel Greenberg, 10 January 1984, USHMM RG-50.462.0281.

- 44

Simche Hirsh Boytener, “Vishnevets 1944,“ trans. Tina Lunson, in Rabin, Sefer Vishnivits, 387.

- 45

M. Malev, “My Trip to Vishnevets in 1956,“ trans. Sara Mages, in Rabin, Sefer Vishnivits, 137.

- 46

Chayim Korin, “Years of Senseless Horror,“ trans. Sara Mages, in Rabin, Sefer Vishnivits,114.

- 47

Interview with Galina K. in Boremel, 28 November 2001, YIU/1343U.

- 48

Interview with Magdalina K. in Zboriv, 16 May 2009, YIU/830U.

Grossman, Vassili. Carnets de guerre. De Moscou à Berlin, 1941–1945. Paris: Calmann-Lévy, 2007.

Pozner, Valérie, Alexandre Sumpf, Irina Tcherneva, and Vanessa Voisin, eds. Filmer la guerre: les Soviétiques face à la Shoah 1941–1946. Paris: Mémorial de la Shoah, 2015.

Hicks, Jeremy. First Films of the Holocaust: Soviet Cinema and the Genocide of the Jews, 1938–1946. Pittsbrugh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012.

Tcherneva, Irina. “Historiciser les images soviétiques de la Shoah (Estonie, Lituanie, 1944-1948).” Vingtième Siècle. Revue d'histoire 139, no. 3 (2018): 59–78.

Liebman, Stuart. “Les premiers films sur la shoah: les Juifs sous le signe de la Croix.” Revue d’Histoire de la Shoah 195, no. 2 (2011): 145–179.

Rabin, Chayim, ed. Sefer Vishnivits: Sefer zikaron likedoshei Vishnivits shenispu besho'at hanatsim. Tel Aviv: Organization of Vishnevets Immigrants, 1970.

Kruglov, Aleksander. Katastrofa ukrainskogo evreistva 1941–1944 gg.: Entsiklopedicheskii spravochnik. Kharkiv: Karavella, 2001.

Spector, Shmuel. The Holocaust of Volhynian Jews, 1941–1944. Jerusalem: Yad Vashem & The Federation of Volhynian Jews, 1990.

Stein, Abraham Samuel. Pinkas Kremenets. Tel Aviv: Hotsaʼat Irgun ole Ḳremnits be-Yiśraʼel, 1954.

Martin Dean, ed. The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Encyclopedia of Camps and Ghettos, 1933–1945: Ghettos in German-Occupied Eastern Europe, vol. 2, 1394–1397. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2012.

Archives

Extraordinary State Commission, GARF 7021-75-3, GARF 7021-75-6, GARF 7021-75-493

Bundesarchiv Ludwigsburg, BArch B162-7493 to B162-7495

Ereignismeldungen UdSSR no. 28, July 20, 1941

USHMM, RG-60.6953, RG-50.462.0281

Oral Testimonies

Yahad – In Unum, YIU/2618U, YIU/2613U, YIU/842U, YIU/839U, YIU/840U, YIU/841U, YIU/1343U, YIU/830U