A Travelling Archive

Tracing Soviet Liberation Footage

Table of Contents

Soviet Film Footage and Professional Practices (1941–1945)

Towards a History of Soviet Film Records (Kinoletopis')

A Travelling Archive

Zinovii Tolkachov’s Graphics from the Auschwitz-Birkenau and Majdanek Death Camps

People with Disabilities as Nazi Victims on Screen and Paper

Forgotten: Film Documents from the Liberated Camps for Soviet POWs

Depicting Atrocities

Reflections on the Geography of the Holocaust Based on Soviet Film Footage

Soviet Footage from the 1940s and the Holocaust at Babyn Yar, Kyiv

Filming Auschwitz in 1945: Osventsim

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Schmidt, Fabian, and Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann. “A Travelling Archive: Tracing Soviet Liberation Footage.” Research in Film and History 6 (2025): 1–29. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/23564.

Our film heritage is fragmented. Only ten percent of completed films from the silent era have been preserved. Some films, such as Hans Karl Breslauer’s adaptation of Hugo Bettauer’s satirical novel Stadt ohne Juden / City without Jews from 1924, were considered lost for a long time. In 1991, an incomplete and damaged version of the Austrian film was discovered in the Netherlands, consisting only of fragmented scenes from the controversial movie, which had faced fierce opposition from Nazi supporters in Austria and Germany. This opposition led many cinemas to re-edit and censor their screening versions. After the restoration of the recovered copy, a more complete version of the film was discovered at a Parisian flea market in 2015. This allowed for comparison and combination with the earlier fragment, revealing impressive scenes of the expulsion of Jews from the fictional city of Utopia. These scenes not only echoed motifs from earlier expulsions but may have also influenced portrayals of deportation in Nazi propaganda, including JUD SÜSS (DE 1941, Veit Harlan), as well as private films and photographs of real deportations such as in a short film from Bruchsal from 1940.

In other cases, footage previously unknown or considered lost survived by travelling through other films. The hypothesis of a so far unacknowledged piece of material from the famous Westerbork film that was formed on the basis of utilizations in documentaries by one of the authors, Fabian Schmidt, resulted in the discovery of 20 Minutes of original negative that had been forgotten by the Dutch archives most likely due to a generational change in the 1980’s.1

It is not uncommon that cultural artefacts are handed down in a type of secondary “used” form, specifically not in context of events such as genocide and war. Be it so-called spolia, pieces of stone that are reused for new buildings that sometimes are the only relics of a certain era of architecture or a former edifice, because the original building or buildings didn’t survive or be it texts written on papyrii that were used to embalm corpses for mummification. Many of the original texts that were destroyed when the library of Alexandria burnt down existed and survived in the form of copies in other places. The perhaps most astonishing example has turned into a trope of cultural studies, the ubiquitous “palimpsest,” its best-known example the Archimedes Palimpsest, a 10th century copy of two mathematical books by Archimedes deemed lost, which was erased and re-used as a prayer book but survived thanks to the, if faintly, readable original letters under the new text. In the 1990s these were decyphered and hence the Archimedes text which had travelled under the prayer book for more than 600 years re-emerged. In 1860 E. C. Werlauff, a Librarian at the Danish Royal Library in Copenhagen discovered parts of the long-lost epic poem “Waldere” on parchments that had been used to stiffen the binding of an Elizabethan prayer book. Also, films can survive as travellers. STÜRME DER LEIDENSCHAFT / THE TEMPEST (1931), an early sound film by Robert Siodmak, featuring Emil Jannings for example, was accounted for as lost by German archives (and still is not available anywhere in Europe), but actually survived as a slightly shortened export version with Japanese side titles in the National Film archive of Japan. Due to the disposal of hundreds of nitrate film copies that over the years had piled at the end of the commercial distribution chain in Dawson City in 1929, dozens of silent films that were previously thought to be lost were salvaged upon their rediscovery in 1978 – an archive that had literary travelled to the end of the Western world. Cultural manifestations in general survived in the form of literary travelling archives more often than otherwise. And sometimes the travelling memory that is manifest in the use of archival film material in documentary films can lead to the re-finding of materials that had gone lost within the archives themselves. Precisely this is the case with film footage filmed by Allied cameramen in the last years of World War II, mostly US signal corps, British camera crews in Bergen Belsen and Soviet cinematographers on the Eastern front since 1942, which had the purpose to document and provide evidence for crimes committed by Nazi Germany.

Until recently, it was rather difficult to properly trace the vast amount of this liberation footage depicting Nazi atrocities. Early compilations of it, such as the Soviet and US-American re-education and atrocity films, circulated in several editions, which were scattered in archives around the world. Due to a lack of digitized materials, a comparison of these versions that were aiming at various audiences in different countries was not always possible. Furthermore, the same and similar footage that was compiled into these early “atrocity films” was also used on other occasions, for instance in various newsreels, again addressing several audiences in different countries. In the decades to follow the end of World War II numerous documentary films utilized the very same footage next to previously unknown shots and images. Questions about provenance or about how and when these outtakes had become accessible for filmmakers and TV producers, and under which circumstances were difficult to answer, specifically due to different sources of the films (military units, newsreels, private films) and the political circumstances (World War II, Cold War) as well as archival collections holding the footage that were spread around the globe.

Film historical research also sought to ascertain the timeline of public awareness surrounding these images and the extent to which filmmakers were cognizant of the production context when incorporating them. Such inquiries were almost impossible during the “age of electronic reproducibility and dissemination,”2 before digitization. Examining the fragmented histories of individual film productions, such as those involving the filming at the liberated Bergen-Belsen concentration camps or the image migrations within Alain Resnais’ NUIT ET BROUILLARD, as explored by Sylvie Lindeperg,3 required extensive research efforts and privileged access to archival materials.4

Digitization, digital curation, and the development and implementation of machine learning for the automated analysis of historical films has only recently increased the possibilities of reconstructing the efforts of documenting German atrocities inside and outside the camps and tracing the migration of particular footage.5 The analysis of such image migration previously depended on relatively small samples, a limited accessibility of relevant films, and the individual knowledge and viewing experience of the researchers.6 The EU Horizon 2020 project Visual History of the Holocaust: Rethinking Curation in the Digital Age (VHH) has made a significant change on several levels: (1) It has gathered advanced high resolution digitizations of Allied films that were previously scattered in archives around the world including outtakes and previously unused or rarely utilized footage.7 (2) The project has developed and applied automated film analysis techniques based on machine learning, which allow for the detection of shot size, camera movement, objects and relations to identical or similar footage.8 (3) A comprehensive vocabulary was defined for detailed, shot based annotations that enable advanced search operations. (4) The VHH-MMSI platform allows the annotation and specification of relations, thereby making it possible to locate the mediation and re-mediation of atrocity images as well as identifying gaps and losses of specific shots and outtakes.9 In the following, we demonstrate the potential of the methods developed and applied in the course of the VHH project for tracing, analyzing and specifying the use of footage from liberated concentration camps with the help of manual and automated relation detection.

The Search for Relations

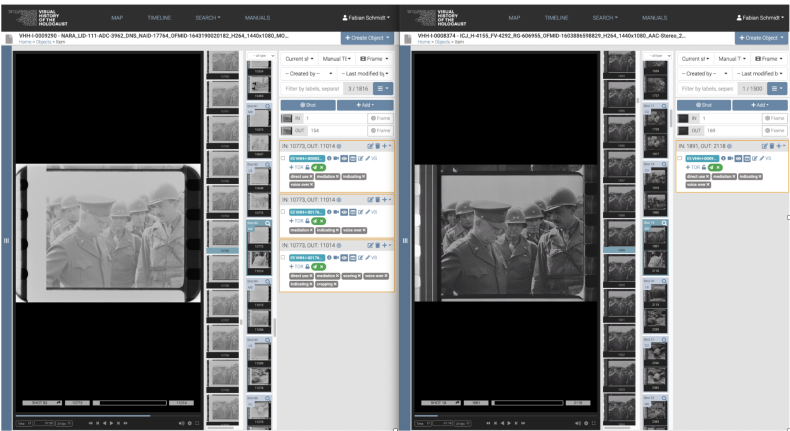

One of the goals of the Visual History of the Holocaust project was to detect and provide digital transfers of the original liberation footage. We were particularly intrigued to uncover the origins of those shots that had been used regularly and constituted the most iconic materials from the liberation of the camps. Referring to the concept of image migration,10 we aimed towards a relational approach to analyze and contextualize these iconic images. For that purpose, we gathered and digitized on the one hand original footage from the liberated camps and other atrocity sites that was dispersed in different archives around the world, and on the other hand collected early compilation films, such as DEATH MILLS (1946), NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMPS (1945) or the Soviet films MAJDANEK (1944) and OSWIECIM (1945), and compared both materials – the original sources and their use in early documentaries – by linking them in our database through time based annotation of relations. More precisely, we linked predefined, automatically detected frame ranges in the source materials – the original Signal corps films for example – with their utilization in documentary and atrocity film. To put it differently, we searched for different versions of identical footage in source and carrier films. For instance, we were able to trace the origins of a montage with concentration camp gates from the re-education film DEATH MILLS (carrier) back to the original Signal corps and Soviet film materials (source) and could thereby identify them as gates in Flossenbürg, Kaufering and Ebensee. To give another example, we matched a shot from DEATH MILLS that depicts US-General Dwight D. Eisenhower visiting the former Ohrdruf concentration camp in Thuringia, Germany with the Signal Corps material from the US-American NARA Archive. The same shot is found in materials from the Imperial War Museum that were gathered in context of the production of an unpublished film about the liberation of Bergen-Belsen.11 Within the Media Management and Search Infrastructure (MMSI) of the VHH project, frame ranges related to the specific shots in each of the films are manually linked and displayed as annotations of each of the respective shots (Fig. 1). This allows to trace and to document the migration of the Ohrdruf footage from the Signal Corps material into the early US-American compilation film and further towards the footage collected for the production of the British film about Bergen-Belsen.

To explain it simply, we have the complete original camera materials that were shot by Allied camera teams and we have compilation films such as DEATH MILLS that used these materials. By relating and comparing both, we can assess how much of the original footage was used by the editors and what the cameramen had filmed before and after the selected moments. This allows additional insights into the context of filming, and offers new possibilities for a qualitative analysis of the use and migration of historical film footage. Such insights are valuable and emerge from the options the project infrastructure provides. But the annotation of relations we pursued during the project phase also revealed fascinating insights on a much more basic level. By tracing the origins or the footage used in DEATH MILLS, the re-education film became visible as a carrier for travelling archives. This conclusion stems from two observations. Firstly, DEATH MILLS has visibly served as a source for other documentaries that did not consult the originals in the NARA archives, but instead re-used shots from DEATH MILLS. And secondly, quite some shots used in DEATH MILLS can no longer be traced back to their original, hence DEATH MILLS in fact is their most original, though travelling, archive, at least for the time being.

According to Mannoff, archives can be defined as "a repository and collection of artifacts"12 that are "shaped by social, political and technological forces"13 Relating this definition to film collections preserving liberation footage, we have to consider that archives had to obey certain technical specifications. Film material was indexed and stored in different ways by different units who produced or used footage in the 1940s for different purposes, and footage was recorded and made available in different formats and different versions. Above all, liberation films are characterized by the political constellations during and after the Second World War, and in particular by the need to document the crimes committed by Germans in a way that would stand up in court. However, they have also been shaped by the imminent, fundamental change in this constellation in the context of the formation of the Cold War, as well as by various social memories in national and transnational contexts. The latter points to the fact that films as repositories of liberation footage also function as transportable archives, and in particular could have a memory-forming effect. Such “traveling archives” have clear similarities with what Astrid Erll has called “travelling memory.” Erll defines particularly transcultural memory as “incessant wandering of carriers, media, contents, forms and practices of memory.”14 In a similar way, the Allied atrocity footage, combining aspects of media, content, forms and practices, travelled by the help of “carriers” such as early compilation films and post-war documentaries on a global scale. Films like DEATH MILLS, in this regard, are no containers that locked up the cinematic evidence of Nazi atrocities.15 To the contrary, as carriers of the footage they established renewed access to the actual containers: archives dispersed around the world as well as lost or undetectable footage. Correspondingly, not only film archives became “increasingly significant for Holocaust memory”16 both as a source and as a place for preservation, “archive footage as it appears in other films has [also] become the starting point for re-viewing historical images.”17

In the platform age, online repositories tend to blur the boundaries between film and archive even further. With the help of annotations, archive footage and film segments can be identified and made searchable in equal measure. In addition, links can be created that fill gaps in the existing archives on the one hand, and can also point out such gaps on the other. The VHH platform as a dynamic repository of both, the former carrier films as well as the travelling footage, thus became a certain kind of travelling archive itself that allows numerous ways of linking and interlinking the visual memory of Nazi atrocities. It contains digitized archive footage that can be linked to later uses in compilation and documentary films and also links them to the archives that preserve the original footage.

The Lost Origins

Within this travelling archive, the Soviet archival materials, namely the footage from Majdanek and Auschwitz, constitute a special case. What we got during the VHH project as “original materials” from the Documentary Film archive of the Russian Federation (RGAKFD) in Krasnogorsk often appeared chaotic and fragmented: a lot of short clips that looked like leftovers or cutaways, film material that was difficult to decipher. Astonishingly, a lot of the footage, which was already known from later compilation films including the early films MAJDANEK (1944) and OSWIECIM (1945), was not part of the digitized original or “source” materials provided by the RGAKFD. To phrase it differently: the original camera negatives of the materials used in the atrocity film OSWIECIM from 1945 no longer seem to exist in the Russian archive – at least today the archive does not know where they are and there is a certain likelihood that they only survived as part of the edited films such as MAJDANEK and OSWIECIM.

We are not talking about generic footage, but about shots that long have been iconic parts of the visual histories and collective imageries of the Holocaust worldwide. Among the shots that only exist as part of the above-mentioned compilation or atrocity films and not as original footage being preserved in the archives are: the iconic aerial shot of the barracks in Birkenau, the famous shots of children with the number tattoo and even the iconic camp gate (Fig. 2).

Also, in case of the liberation of the concentration camp near Lublin, better known under the local name “Majdanek,” iconic archive materials cannot be found in the archive anymore, for instance the infamous “Bad und Desinfektion II” sign or the iconic chimney of the main crematorium. Even the shot with the doll from the Majdanek ‘Effekten’ storage is not existing as an original archive shot, or at least: the archive has no access to it, even if it might still exist, they don’t know where (Fig. 3).

In this case, the early compilation films OSWIECIM and MAJDANEK did not only become carriers of visual evidence from the camps, but serve today as solely remaining archives of footage without a traceable origin.

Films as Archives

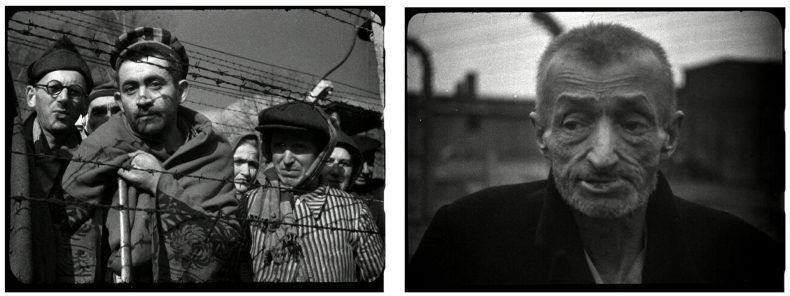

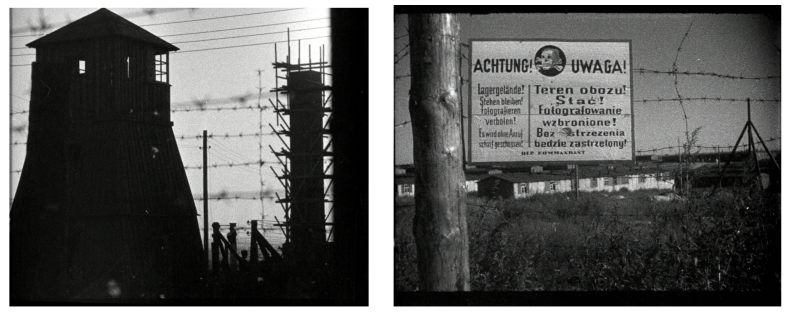

Some material, however, still exists in the Russian archives. A closer look at the footage, with digital copies we obtained from the Krasnogorsk archive, revealed the following shots as still existing in the archive as originals: the inmates at the fence in Auschwitz, the old survivor (Fig. 4), the often-quoted sign from Majdanek, just as the well-known shots of the watchtower and the barbed wire (Fig. 5).

We also got some seemingly unused materials. When we compared them to the material used in early Soviet compilation films, it turned out that many of these fragments from Krasnogorsk were in fact unused or cutout parts of the familiar materials. By re-unifying them with the already known footage in a videographic editing approach, it was possible to reconstruct what is missing in the archive: the (more or less) complete original source materials.

For the repository of the VHH, we were specifically interested in identifying original source materials of the Number Tattoo footage.18 But we only found a very short fragment at Krasnogorsk. However, if you play the passage with the children from OSWIECIM and that fragment one after the other, they complement and complete each other. It is actually a seamless transition, which demonstrates that the footage in the archive is the exact outtake or cut away from the material seen in OSWIECIM (Video 1). The now, if only partially, completed sequence reveals at least one little detail that the editors perhaps tried to obscure by shortening the shot. In the part from OSWIECIM, the boy closest to the camera, Rene Gutmann, born in December 1937 in Czechoslovakia to German-Jewish parents, initially appearing fatigued, experiences a gentle yet inadvertent tap on the head from the child behind him. Whether this is the reason or whether he is frightened by something that he sees in the off, he suddenly appears on the verge of crying. Right after the cut, he is no longer able to hide it, and his cheeks show how he is overcome with sadness.

Another example demonstrates how the Krasnogorsk material is completing the remaining materials from other films. In video 2, we combined archival footage we received from the RGAKFD with shots taken from the atrocity film OSWIECIM. Also, in this case the footage from the second half does not exist in any Russian archive anymore, at least officially. Here, the re-completed shot reveals a slightly different intention of the cinematographer. As the footage from RGAFK shows, the shot originally started with two elegant women’s shoes and the camera then moved towards a less significant part of the pile. The edited version almost omits the women’s shoes and focuses on the indifference of the piled shoes instead.

Another example from OSWIECIM depicts piles of suitcases in Auschwitz. The first shot in this videographic montage originates from the footage we got from Krasnogorsk. It is followed by a complementing part from OSWIECIM, which is actually completing the original shot (Video 3). In this case, the editor only cut away the beginning of the panning shot, which starts a little hesitant. Starting a couple of seconds into the shot also adds to the impression of an endless heap of suitcases, as it omits the edge of the pile actually visible in the first second of the raw footage. These first seconds also show a part of the building behind the pile, which will make it possible to locate the shot.

Video 4 is another example of how the Krasnogorsk material is completing the remaining materials from other films. The beginning is from the new material we received from Russia and the second half is taken from the film MAJDANEK. Also, in this case the footage from the second half does not exist in any Russian archive anymore, at least not officially. MAJDANEK only uses the last seconds with a passport of a young Polish woman. The Dutch and the French passports visible in the first half of the footage are admittedly a little less engaging and meaningful.

In all these cases the early compilation films are the only remaining carriers of the lost original archive footage. They now function as filmic archives, which assist in filling the gaps existing in the state archives. As part of the VHH platform’s travelling archive those films serve as both: visual records of the liberation and as early manifestations of the use of such visual records in compilation films.

Looking at the raw archive material in the VHH Repository that was used for OSWIECIM, it is clear that significant parts of the original footage were only preserved as part of the edited film. A sequence from the Auschwitz infirmary in the raw material from the archive is characteristic for this observation. First, we see a medium long shot of a group of Soviet military doctors in a consultation. A woman in a prisoner uniform is brought in. Although the film is silent, we can see that the doctors speak to her. She is sitting with her back to the camera and answers their questions. In the following medium shot, we suddenly see one of the doctors standing next to her and holding her bare arm towards the camera. With his finger, he points to the number tattooed on her arm.

The sudden jump cut reveals that something had happened in between. In the previous shot the woman was speaking, her sleeve was not pulled up, and she was sitting alone in front of the doctors. Indeed, something was missing here.

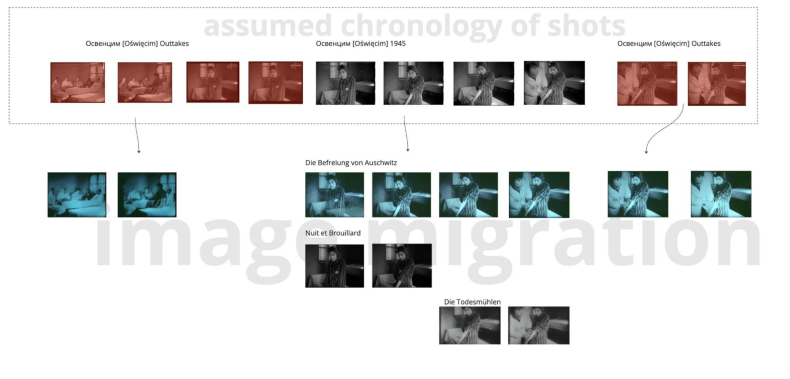

Reviewing the respective sequence in the edited film OSWIECIM brings to attention that the medium front shot of the woman in the prisoner uniform that was edited into the atrocity film is actually the missing part from the raw material. By inserting the part from OSWIECIM into the raw material, we were able to reconstruct the assumed chronology: first the medium long shot with the doctors and the woman from behind, then the medium reverse shot depicting the woman speaking, and then slowly pulling up her sleeve to show the number tattooed on her arm to the doctors, and then the doctor entering the frame and holding her arm towards the camera. The part utilized in OSWIECIM, however, cuts away exactly before the doctor points with his finger to the number (Fig. 6).

Obviously, two early compilation films only used the footage that was edited into OSWIECIM. Alain Resnais’ NIGHT AND FOG, for instance, only used the first part of the medium shot up until the moment when the woman pulled up her sleeve. In contrast, DEATH MILLS had utilized the second part of the shot, beginning with the medium shot of the woman’s bare arm, and continuing with the doctor stepping into the frame. Also, in the case of DEATH MILLS the part of the original footage containing the doctor pointing with his finger to the number tattoo is missing. Both sequences together, the one from DEATH MILLS and the one from NIGHT AND FOG, exactly correspond to the shot from OSWIECIM.

It seems that no complete version of the original recordings has survived in the archive. It only exists as separate sequences in the outtakes on the one hand, and in the released version of OSWIECIM on the other. A coherent and chronologically correct sequence, however, can be found in the documentary film THE LIBERATION OF AUSCHWITZ by Irmgard Von zur Mühlen from 1986, including the final frames depicting the doctor pointing with his finger to the number tattoo. This sequence seems to consist of connected shots. Perhaps it was actually discovered in its entirety as an edited sequence by Von zur Mühlen in the archive and can no longer be found or accessed today. In any case, the complete sequence is only preserved today in THE LIBERATION OF AUSCHWITZ. On closer inspection, however, it is noticeable that some frames are missing after the only cut in the sequence, the reverse cut to the medium shot of the woman. These in turn are part of the outtakes from the archive. This example shows how, on the one hand, film archives of liberation films are characterized by gaps and, on the other hand, film material missing from the archive is only preserved in carrier films and passed on from them.

The final example is again taken from THE LIBERATION OF AUSCHWITZ. It seems as if Von zur Mühlen had something similar in mind as the VHH platform’s travelling archive does: completing the familiar and repeatedly used footage with excerpts from the archive, and thereby creating a film that acts as a travelling archive, which reconstructs the original footage that was fragmented and dispersed through time. Von zur Mühlen, however, does this with the help of cinematic means, and in the form of a solely analog endeavor. The following split-screen arrangement presents an extract from the Von zur Mühlen’s film on the left, and shows the corresponding source footage at the right side of the screen (Video 7). The first shot in this sequence comes from the Russian archive. The second and third are part of OSWIECIM. The fourth shot in this example completes the third by almost 6 seconds. It can be found as part of a montage of unconnected shots in the outtakes from Krasnogorsk. Von zur Mühlen is able to reconstruct and recomplete two consecutive shots by combining the different source materials.

Travelling Archives

Erwin Leisers DEN BLODIGA TIDEN / MEIN KAMPF (1960) is also carrying two shots that are taken from the footage shot in Auschwitz during the liberation but that are neither part of OSWIECIM nor are preserved in the Russian archives. These shots show child survivors in a winterly setup which matches one of the scenes from the outtakes of OSWIECIM. They appear in a two-minute sujet from a Polish newsreel showing Birkenau facilities in the snow in January 1945, trains full of clothes and grown-ups and child survivors leaving a barrack in the freezing cold that was re-discovered only recently by Ania Szczepanska. Again, the material has not survived as original footage in the archive, but in at least two other instances, if only partially.

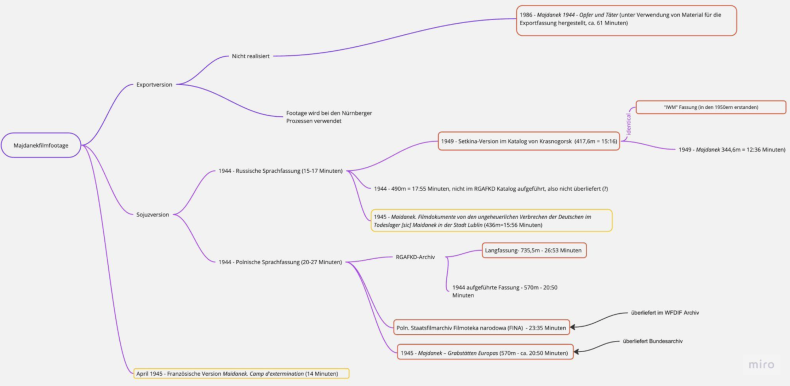

In her seminal study of the Majdanek film Filme über Vernichtung und Befreiung: Die Rhetorik der Filmdokumente aus Majdanek 1944–1945 historian Natascha Drubek-Meyer has tried to trace the different versions and archive locations of the famous and first Holocaust atrocity film. The diagram (Fig. 8) is the attempt to relate all known versions of the film and to explain the genealogy of these versions (the films marked in red are identified versions), how they emerged and how they influenced each other. Some of the connections are still assumptions.

We had hoped that in the course of the VHH project we would be able to gather all these versions and reference them to the source materials from the Soviet cameramen. However, this turned out to be much more difficult and eventually impossible for several reasons, including the current political situation. Still, we found some interesting traces and this search is perhaps a good example of how sometimes research outside the archives is helpful and even needed in order to fill gaps in the archival records. Hopefully, Drubek-Meyer’s findings will add to a further completion of the archival record of these materials. Perhaps with this in mind, Bengt and Irmgard von zur Mühlen produced the film MAJDANEK 1944 in 1986 while using large parts of the then still existing footage. The entire material, 19 reels of originals that we found in Krasnogorsk is about 107 minutes long. Von zur Mühlen did use about half of it in their film. However, there are about 10 minutes of material that can only be found in the Von zur Mühlen film and not in the archive, so again, a film serves as an archive here. And as we just found out, the Von zur Mühlens did copy lots of material from the Russian archives and brought this material as 35mm film to Germany. These reels still exist and might prove to host further so far unknown materials.

Conclusions

The exploration of the image migration of liberation films shot by Soviet camera teams in Auschwitz and Majdanek has revealed both challenges and intriguing discoveries. By gathering, digitizing and analyzing Allied liberation films, the EU Horizon 2020 project Visual History of the Holocaust (VHH) made it possible to identify relations between the original footage and the compilation and re-education films that used these materials and helped to shed light on previously unknown footage. This comprehensive effort has not only facilitated a nuanced understanding of how these images migrated in various versions but has also helped to highlight its historical significance. By linking original liberation footage with its use in early documentaries, the VHH project showcased how compilation films served early on as carriers and as travelling archives for these materials. Hence, despite geopolitical challenges limiting access to certain film versions, technology and comprehensive analyses have transformed the study of historical film footage.

The examination of Soviet archival materials, particularly from Majdanek and Auschwitz, revealed a complex landscape of fragmented and dispersed footage. While early compilation films like OSWIECIM and MAJDANEK became crucial repositories of iconic footage, gaps in archival records remain, emphasizing the need for further research. The phenomenon of the missing films, however, is by no means restricted to the archives of the former Soviet Union but occurred also with footage from the NARA archives within the VHH project. A significant part of the source material of DEATH MILLS for example proved to be untraceable and the same goes for NAZI CONCENTRATION CAMPS (1945) and the often-cited WELT IM FILM NO. 5 (1945, also known as “KZ”) that focuses on the camps. Hence all these films, to a degree, serve as exclusive archives of parts of the materials they use.

The project’s focus on identifying original source materials has led to intriguing discoveries, such as the possibility of completing missing archival footage through the re-unification of materials used in several films. The concept of films as “travelling archives” – compilation films that act as repositories of lost original footage – made it possible to bridge gaps in current archival records. Here, the VHH platform serves as a dynamic repository, allowing for the linkage and interlinkage of visual memory of Nazi atrocities. In essence, the study of image migration in liberation films has not only enhanced our understanding of historical events but has also demonstrated the importance of technology and collaborative efforts in preserving and analyzing visual history. Through initiatives like the VHH project, we continue to uncover layers of untapped cinematic memory, enriching our collective understanding of the past.

The films and texts we mentioned at the beginning, previously thought lost, have been reintegrated into film archives and libraries making them accessible once again. Their rediscovery and inclusion in institutional collections have resolved their status as unrecognized artifacts. However, as the case of STÜRME DER LEIDENSCHAFT (1931) shows – a lost film that turned up in another archive, but still stays out of reach – this process of making items available is complicated as soon as national borders are involved. Our documentation of missing Soviet liberation footage, now part of the VHH database and of this essay (and correspondingly the findings of Natascha Drubek-Meyer documented in her publication), raises questions about whether merely documenting these findings is enough to ensure their inclusion in the preserved film heritage. Since our research combines archival and non-archival sources from various national contexts, existing film archives may not see it as their responsibility to preserve these discoveries. Perhaps it’s time to consider establishing an institution dedicated to recording and organizing outcomes from transnational, extra-archival efforts, supporting national archives in cases where they lack the resources to complete their collections independently.

- 1

Fabian Schmidt, “The Westerbork Film Revisited: Provenance, the Re-Use of Archive Material and Holocaust Remembrances,” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 40, no. 4 (2020).

- 2

Anton Kaes, “History and Film: Public Memory in the Age of Electronic Dissemination,” In Framing the Past. The Historiography of German Cinema and Television, ed. Bruce A. Murray and Christopher J. Wickham (Carbondale/Edwardsville: South IllinoisUP, 1992), 308.

- 3

Sylvie Lindeperg, Night and Fog: A Film in History (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014).

- 4

Toby Haggith, and Joanna Newman, eds. Holocaust and the Moving Image (Columbia: Wallflower, 2005).

- 5

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Noga Stiassny, and Henig, Lital, “Digital Visual History: Historiographic Curation Using Digital Technologies,” Rethinking History 27, no. 2 (2023): 159–186, DOI: 10.1080/13642529.2023.2181534.

- 6

Tobias Ebbrecht, “Migrating Images: Iconic Images of the Holocaust and the Representation of War in Popular Film,” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 28, no. 4 (2010): 86–103, https://doi.org/10.1353/sho.2010.0023.

- 7

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Geschichte ist Beziehung: Über Vernetztes Erinnern und digitales Kuratieren einer visuellen Geschichte des Holocaust,” in Erinnerungskultur und Holocaust Education im digitalen Wandel: Georeferenzierte Dokumentations-, Erinnerungs- und Vermittlungsprojekte, eds. Victoria Kumar, Gerald Lamprecht, Lukas Nievoll, Grit Oelschlegel, and Sebastian Stoff (Bielefeld: transcript, 2024), 178–179.

- 8

Daniel Helm and Martin Kampel, “Video Shot Analysis for Digital Curation and Preservation of Historical Films,” in GCH 2019 Eurographics Workshop on Graphics and Cultural Heritage, eds. Selma Rizvic and Karina Rodriguez Echavarria (The Eurographics Association, 2019), https://doi.org/10.2312/gch.20191344.

- 9

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Geschichte ist Beziehung,” 184–188. See also: Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Stassny, Henig, Lital, “Digital Visual History.”

- 10

Ebbrecht, “Migrating Images.”

- 11

Toby Haggith, “The Filming of the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen and Its Impact on the Understanding of the Holocaust,” Holocaust Studies 12, nos. 1–2 (2006): 89–122.

- 12

Marlene Manoff, “Theories of the Archive from Across the Disciplines,” Libraries and the Academy 4, no. 1 (2004): 10.

- 13

Manoff, “Theories of the Archive,” 12.

- 14

Astrid Erll, “Travelling Memory,” Parallax 17, no. 4 (2011): 4–18, https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2011.605570.

- 15

For a detailed anlysis of DEATH MILLS see: Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann and Fabian Schmidt, "15. Virtual Topographies of Memory: Liberation Films as Mobile Models of Atrocity Sites," in Non-Fiction Cinema in Postwar Europe: Visual Culture and the Reconstruction of Public Space, ed. Lucie Cesalkova, Johannes Praetorius-Rhein, Perrine Val, and Paolo Villa (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2024), 399–424, https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048556625-023.

- 16

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Echoes from the Archive: Retrieving and Re-viewing Cinematic Remnants of the Nazi-Past,” in Edinburgh German Yearbook 9: Archive and Memory in German Literature and Visual Culture, ed. Dora Osborne (Boydell and Brewer: Boydell and Brewer, 2015), 124, https://doi.org/10.1515/9781782046431-007.

- 17

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, “Echoes from the Archive,” 125.

- 18

Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Noga Stiassny, and Fabian Schmidt, “The Auschwitz Tattoo in Visual Memory. Mapping Multilayered Relations of a Migrating Image,” Research in Film and History (2022), https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/19713.

Drubek-Meyer, Natascha. Filme über Vernichtung und Befreiung: Die Rhetorik der Filmdokumente aus Majdanek 1944–1945. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2020.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias. “Echoes from the Archive: Retrieving and Re-viewing Cinematic Remnants of the Nazi-Past.” In Edinburgh German Yearbook 9: Archive and Memory in German Literature and Visual Culture, edited by Dora Osborne, 123–139. Boydell and Brewer: Boydell and Brewer, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781782046431-007.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias. “Geschichte ist Beziehung: Über Vernetztes Erinnern und digitales Kuratieren einer visuellen Geschichte des Holocaust.” In Erinnerungskultur und Holocaust Education im digitalen Wandel: Georeferenzierte Dokumentations-, Erinnerungs- und Vermittlungsprojekte, edited by Victoria Kumar, Gerald Lamprecht, Lukas Nievoll, Grit Oelschlegel, and Sebastian Stoff, 173–189. Bielefeld: transcript, 2024.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias, Noga Stiassny, and Lital Henig. “Digital Visual History: Historiographic Curation Using Digital Technologies.” Rethinking History 27, no. 2 (2023): 159–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642529.2023.2181534.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias, and Fabian Schmidt. "15. Virtual Topographies of Memory: Liberation Films as Mobile Models of Atrocity Sites." In Non-Fiction Cinema in Postwar Europe: Visual Culture and the Reconstruction of Public Space, edited by Lucie Cesalkova, Johannes Praetorius-Rhein, Perrine Val, and Paolo Villa, 399–424. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2024. https://doi.org/10.1515/9789048556625-023.

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, Tobias, Noga Stiassny, and Fabian Schmidt. “The Auschwitz Tattoo in Visual Memory. Mapping Multilayered Relations of a Migrating Image.” Research in Film and History (2022). https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/19713.

Ebbrecht, Tobias. “Migrating Images: Iconic Images of the Holocaust and the Representation of War in Popular Film.” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 28, no. 4 (2010): 86–103. https://doi.org/10.1353/sho.2010.0023.

Erll, Astrid. “Travelling Memory.” Parallax 17, no. 4 (2011): 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2011.605570.

Haggith, Toby. “The Filming of the Liberation of Bergen-Belsen and Its Impact on the Understanding of the Holocaust.” Holocaust Studies 12, nos. 1–2 (2006): 89–122.

Haggith, Toby and Joanna Newman, eds. Holocaust and the Moving Image. Columbia: Wallflower, 2005.

Helm, Daniel, and Martin Kampel. “Video Shot Analysis for Digital Curation and Preservation of Historical Films.” In GCH 2019 Eurographics Workshop on Graphics and Cultural Heritage, edited by Selma Rizvic and Karina Rodriguez Echavarria. The Eurographics Association, 2019. https://doi.org/10.2312/gch.20191344.

Kaes, Anton. “History and Film: Public Memory in the Age of Electronic Dissemination.” In Framing the Past. The Historiography of German Cinema and Television, edited by Bruce A. Murray and Christopher J. Wickham, 111–129. Carbondale/Edwardsville: South Illinois University Press, 1992.

Lindeperg, Sylvie. Night and Fog: A Film in History. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014.

Manoff, Marlene. “Theories of the Archive from Across the Disciplines.” Libraries and the Academy 4, no. 1 (2004): 9–25.

Schmidt, Fabian. “The Westerbork Film Revisited: Provenance, the Re-Use of Archive Material and Holocaust Remembrances.” Historical Journal of Film, Radio and Television 40, no. 4 (2020): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/01439685.2020.1730033.