‘Not Approved for Screening’

Political Film Censorship in West Germany by the Interministerieller Ausschuss für Ost/West-Filmfragen

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Kötzing, Andreas: ‘Not Approved for Screening’: Political Film Censorship in West Germany by the Interministerieller Ausschuss für Ost/West-Filmfragen. In: Research in Film and History. New Approaches (2020), pp. 1–11. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14816.

1. Introduction

Politically motivated film censorship was a common phenomenon at the peak of the Cold War, and the paranoia of films from the enemy’s system was not solely restricted to the dictatorships of the Eastern bloc. In many western nations, too, politicians were eager to protect their citizens from the impact of (alleged) propaganda by censoring foreign films.1 In divided Germany, film censorship was strongly enforced because of the division of the country and the immediate confrontation of the rivalling systems of political power. There has been extensive research covering the political situation of censorship in the German Democratic Republic (GDR)—with particular focus on films with contemporary themes produced by the Deutsche Film AG (DEFA) that were banned or stopped in production in 1965/66.2 Film censorship in the Federal Republic of (West) Germany (FRG), however, has been researched to a lesser extent. Available studies are more likely to focus on the Freiwillige Selbstkontrolle der Filmwirtschaft (FSK; ‘Self-Regulatory Body of the Film Industry’),3 an organization in charge of the age rating of films in accordance with the German Jugendschutzgesetz (‘Protection of Young Persons Act’) up until today. By contrast, other censorship bodies have been neglected, most importantly the so-called Interministerieller Ausschuss für Ost/West-Filmfragen, an interdepartmental committee run by the government in the 1950s and 1960s that was responsible for the assessment of all Eastern European films to be released and presented in West Germany. As of now, the Interministerieller Ausschuss and its backgrounds have only been dealt with in a small number of German studies.4 In international historical research, its activity is largely unknown and only a handful of individual instances have been covered.5

This article provides an introduction into the activity of the committee and scrutinizes the factual backgrounds of film censorship. Several case studies examine the motives for censoring certain films, analyse the legal and political justification of censoring, and deal with incidents of public opposition to the censorship. Finally, the article discusses the relevance of the activity of the censorship committee within an all-German cultural history. The source material of this study will be provided by the protocols recorded at the meetings of the Interministerieller Ausschuss.6

2. Film Censorship as the Activity of the Interministerieller Ausschuss

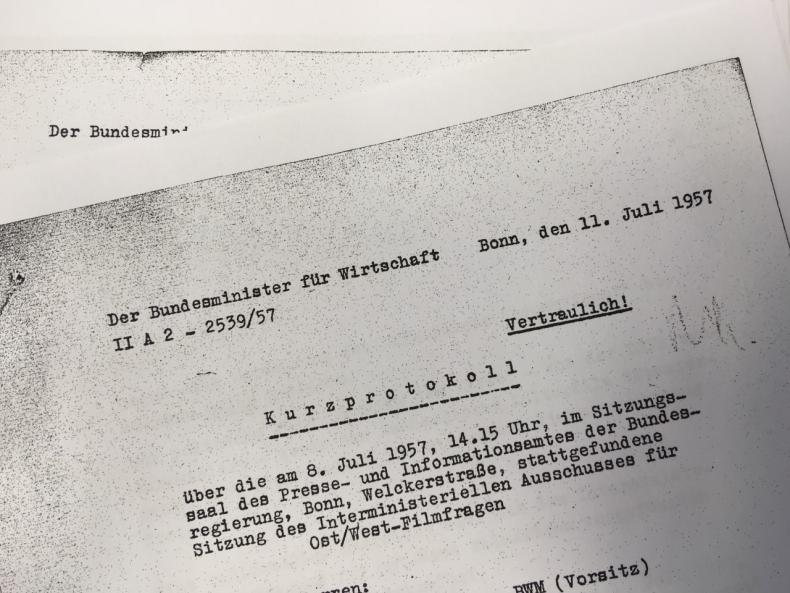

The Interministerieller Ausschuss was initially founded by the Bundesministerium des Innern (BMI; ‘Federal Ministry of the Interior’) and not—as sometimes noted in literature concerning the history of the Ausschuss—by the Verfassungsschutz (‘Federal Office of the Protection of the Constitution’), one of the German intelligence services.7 On 5th January 1953, the BMI held a conference attended by representatives of various ministries and federal agencies. One item on the agenda was the ‘import of films from countries under Soviet control’. The members of the conference decided unanimously to establish a committee responsible for the assessment of the films. The protocol classified as ‘strictly confidential’ gives an insight into the motives for founding the Ausschuss: from then onwards, only films ‘with politically unobjectionable content’ should be given permission to be presented in West Germany.8 The conference stipulated the exact circumstances under which of each film was imported and it also fixed the terms for screening films ‘privately and free of charge’, for example in film clubs. ‘Requests by politically disputed organizations’ were to be rejected without exception; still, the committee was granted the right to ‘give permission to the one-time presentation of films with politically objectionable content, closed to the public.’

The Interministerieller Ausschuss took up its official activity in December 1953. The committee was chaired by the Bundeswirtschaftsministerium (‘Federal Ministry of Economics’). It was in charge of communicating the committee’s decisions to each of the applicants—without stating any reasons with regard to the content whatsoever. Throughout the following years, the staff of the Ausschuss changed significantly, but generally an average of 10–20 officials from different ministries and federal agencies participated in the film screenings. The committee assembled on a regular basis—once or twice a month on average, but also more frequently on occasion, depending on how many films were to be assessed. The film distributing companies were generally required to submit every print of foreign films to the committee for approval within one week.

The Ausschuss ended its activity in early 1967 at the latest, even though the exact point in time at cannot be identified conclusively. At the beginning of 1967, the assessment of the films was transferred entirely to the Bundesamt für gewerbliche Wirtschaft (‘Federal Office of Industrial Economics’). The Bundesamt had already been communicating the committee’s decisions to the applicants in place of the Wirtschaftsministerium since 1961. From 1967, it was supposed to draw upon the activity of the Ausschuss only in highly disputed cases, which, as a matter of fact, did not happen in a single case.9

3. Censoring DEFA Films: Statistical Data

According to the statistical surveys by Stephan Buchloh, who included an examination of the Interministerieller Ausschuss in his essential study on censorship in the Adenauer era, a total of 3,180 Eastern European films were assessed between 1953 and 1966, about 130 of which were not granted the permission to be presented.10 Among the censored films were Czech feature films, such as HIGHER PRINCIPLE/VYSSÍ PRINCI (Jiří Krejčík, CSSR 1960), a vast number of East German documentary and feature films by the DEFA, including DU UND MANCHER KAMERAD (Andrew and Annelie Thorndike, GDR 1956), BETROGEN BIS ZUM JÜNGSTEN TAG (Kurt Jung-Alsen, GDR 1957) and THOMAS MÜNTZER (Martin Hellberg, GDR 1956), and Soviet films, such as the QUIET FLOWS THE DON/TIKHIY DON trilogy (Sergei Gerasimov, USSR 1957/1958), the second and third part of which were not approved for screening.

It is necessary, however, to reconsider and differentiate Buchloh’s statistical data, which he gathered from protocols of the meetings of the Interministerieller Ausschuss, in order to give a detailed record of its censoring practices. From time to time, the committee would revise its original decisions—for example, when the applicant lodged an objection against the censorship, or when, after repeated inspections of a film, the members of the committee were not able to find a significant cause for censorship any longer. Occasionally, the committee conditioned the admission of a film on cutting out certain scenes or limited the screening of the film to a specific audience, for example at festivals.

To provide a detailed account of the activity of the Interministerieller Ausschuss, researchers in a project at the Hannah-Arendt-Institut, Dresden, documented every single film from East Germany assessed by the committee from 1954 to 1966. The extent of the censoring activity can well be portrayed and exemplified by the DEFA productions, on which the committee put a special focus throughout its entire activity.11 The results of this project can be accessed in a public database and will be used in the following chapters. The database contains information about all East German films assessed by the Interministerieller Ausschuss.12

The committee assessed a total of 634 films from East Germany—mostly productions of different DEFA studios but also, occasionally, of the Deutscher Fernsehfunk (DFF), the East German Television Broadcast. 522 out of these 634 films were admitted without objection—66 of them were not approved and in 39 other cases, the films were admitted only under certain conditions, i.e. as authorized cut versions or for screening in front of a restricted audience. After a second assessment, 19 out of the 66 prohibited films were granted full admission and five were given restricted permission for screening.

Table 1: East German films assessed by the Interministerieller Ausschuss

| 1954 | 1955 | 1956 | 1957 | 1958 | 1959 | 1960 | 1961 | 1962 | 1963 | 1964 | 1965 | 1966 | Total | |

| Films assessed | 22 | 23 | 54 | 37 | 54 | 148 | 60 | 3 | 3 | 20 | 82 | 97 | 34 | 634 |

| Without decision | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 7 |

| Admitted | 9 | 17 | 31 | 28 | 46 | 137 | 50 | 3 | 1 | 9 | 68 | 95 | 28 | 522 |

| Admitted under restrictions | 3 | 1 | 10 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 39 |

| Not admitted | 7 | 5 | 13 | 9 | 3 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 66 |

| Admitted after 2nd assesment | 0 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 19 |

| Admitted under restrictions after 2nd assessment | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

Source: own survey

Table 1 summarises the censorship activities of the Interministerieller Ausschuss. The statistical data provide interesting insights into the all-German relations with regard to films in the 1950s and 1960s. A salient point is the comparatively large number of films imported from East into West Germany particularly in the mid-to-late 1950s. In 1959 alone, the Ausschuss took almost 150 film productions into consideration. Many filmmakers in East and West Germany were still in close contact at that time. This aspect has gained considerable attention among film historical researchers in recent years, but the details have yet to be further examined.13 At the same time, the overview exemplifies the deep cut in all-German film trades resulting from the building of the Berlin Wall: in 1961/62, the import of films from East Germany broke down almost completely. Over these two years, the Ausschuss was commissioned to assess a total of only six films.

Yet it is evident, with regard to the censorship conducted by the Ausschuss, that the number of DEFA films and TV productions which were admitted only under restrictions, or not approved at all in West Germany was surprisingly high. On average, one in five films from East Germany assessed by the Ausschuss was not granted immediate admission. In some years, the rate was significantly higher. In 1956, for example, half of all DEFA films fell under objection by the Ausschuss. Only from the mid-1960s, there were gradual signs of relaxation: out of the 213 productions assessed by the Interministerieller Ausschuss between 1964 and 1966, 191 film were permitted without restriction for the cut or other constraints.

4. Case Studies: Political Motives

For a deeper understanding of the extent of the censorship and the underlying motivation, a closer look at individual cases of prohibition is necessary. At the same time, concrete examples from the history of the Interministerieller Ausschuss can illustrate the practical limits of official action and how a public movement critical of society in West Germany put censorship activity out of use.

The decisions of the Interministerieller Ausschuss were informed by fear of communist propaganda and its immediate ‘contagiousness’ if ever the audience should come in contact with such films. In May 1954, the Ausschuss was submitted the documentary LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN (Max Jaap, GDR 1954) for assessment. The film was to be presented, along with 12 other DEFA productions, at the 3rd Mannheimer Kulturfilmwoche, an international festival for documentaries and feature films. LUDWIG VON BEETHOVEN, however, did not pass the assessment by the Ausschuss, along with three more DEFA films.14 The protocol lacks justification for this reasoning, but the motives of the Ausschuss are easily comprehensible, as the film was being assessed repeatedly in the following months—in one instance even with the assistance of an expert musicologist—in order to decide over the public screening of the film in West Germany. In the opinion of the Ausschuss, the film distorts Beethoven’s life to ‘serve a particular purpose’ and the famous composer was ‘branded as the pioneer of communism’.15 The main reason for this assessment might have been the end of the film: Beethoven's 'Ode an die Freude' is illustrated with glorifying images from the GDR to underline the supposed progressiveness of socialism. This ideological glossing over of Beethoven’s music was enough for the Ausschuss to justify the ban of the film.

Another important reasoning driving the Ausschuss in many of its decisions was to prevent criticism of the social conditions in West Germany and the Nazi past. Two such films, DU UND MANCHER KAMERAD and EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK (Joachim Hellweg, GDR 1958), were scheduled for screening as part of a special event at the Mannheimer Filmwoche. In DU UND MANCHER KAMERAD Andrew and Annelie Thorndikes outlined the historical development of Germany since the First World War from the point of view of the SED. They worked with numerous archive images, which gave the film the appearance of a supposed 'factual report'. However, historical events that did not fit into the official interpretation, such as the Hitler-Stalin Pact, were not included. Joachim Hellwig also took up a historical theme in his film. EIN TAGEBUCH FÜR ANNE FRANK describes the biographies of individual Nazi criminals who lived in the Federal Republic of Germany after the end of the war. The Ausschuss, however, decided that both films contained ‘anti-constitutional tendencies’ and vetoed their screenings. It soon became publicly known in Mannheim that the BMI was involved in banning the films, and when a screening was scheduled only in front of a limited audience, the East German producers withdrew the films to provoke a conflict and to bring the dispute into the public eye.16

Apart from these controversial remarks about the covert Nazi history of some West German politicians, the Ausschuss tolerated hardly any critical references to the socio-political situation in West Germany. This can be exemplified by the controversy over BERLIN – ECKE SCHÖNHAUSER…’ (Gerhard Klein, GDR 1957). The film was assessed by the Ausschuss in several differently cut versions, but neither of them got the permission for a public screening in the West. The reason for this was a number of scenes playing in a West German camp for East German refugees: not only do violence and oppression rule the camp, but an adolescent East German refugee even dies under tragic circumstances. It was scenes like these that provoked the rejection by the Ausschuss when BERLIN – ECKE SCHÖNHAUSER… was intended to premiere in West Germany in the autumn of 1958. The short protocol of the meeting states that the film ‘disparages, in its Communist tendency, West German institutions (such as the reception camps)’ und portrays the ‘conditions in an untruthful fashion’. Furthermore, the film depicts ‘deprivations of liberty as minor offences in West Germany’. Based on these findings, the majority of the Ausschuss members in session voted against the admission of the film; even though there was discord among the members as to what extent legal issues could be raised against the film, it ‘should be prohibited any way (…) out of political reasons’.17 Later, the film was given to the Ausschuss in a cut version for re-examination, but even this version was not approved.18

The third key motivation for the Interministerieller Ausschuss in the prohibition of DEFA films was the positive depiction of real life in the states of the Eastern bloc—something the Ausschuss was eager to prevent from spreading. In 1956, MARTINS TAGEBUCH (Heiner Carow, GDR 1956), a short film by the DEFA, was permitted for a one-time presentation as part of the Westdeutsche Kurzfilmtage, a festival for short films in Oberhausen. Three years later, however, the Ausschuss expressed opposition to the official release in West German cinemas. The Bundesministerium für Gesamtdeutsche Fragen (BMG, ‘Federal Ministry of All-German Affairs’), in particular, insisted emphatically on banning the film. The critical factor was the portrayal of the school system in East Germany: Carow tells the story of a school boy whose grades deteriorate under the influence of his parents’ merciless upbringing, but who can be saved in the end by one of his teachers’ courageous effort.19 The BMG stated, with regard to MARTINS TAGEBUCH that the film creates the impression that ‘schools in the Soviet Occupation Zone raise their children, in exemplary collaboration with their teachers, parents and the Pioneer Organization, to mere moral values when in reality, they train them to nothing but atheism and hatred for the Federal Republic [of West Germany]’. As the film was co-produced by the East German Ministry of Education of the People, it constituted, according to the BMG, a vicious attempt ‘to deceive the people of West Germany and put their authorities in the wrong.’ On account of its ‘effect of endangering the constitution’, a presentation in West Germany was prohibited.20

The last recurring reason for banning certain DEFA films was that even the use of symbols or the mention of East German institutional bodies could provoke objection. An interesting example is the short film SPUREN, WISSENSCHAFT UND PARAGRAPHEN (Joachim Hadaschik, GDR 1957), which provides insight into the routine of the East Berlin Institute of Criminology and is generally considered a work of popular science. When the film was to be imported into West Germany, individual members of the Ausschuss were in favour of a ban, because in the opening titles and at the end of the film, the term Volkspolizei (People’s Police, official denomination of the GDR’s police) appears. This was considered a criminal institution not acknowledged by the West German government; therefore, the film could not be admitted, either. Yet, this line of argument was critically ill-founded and thus the majority of the Ausschuss could not find a legal basis for banning the film.

5. Limits of Censorship

Concrete examples from the history of the Interministerieller Ausschuss can also illustrate the practical limits of official action and show how a public movement critical of society in West Germany put censorship activity out of use. The last example particularly sheds light on a central weakness of the censoring activity by the Interministerieller Ausschuss: its decisions lacked legal justification. In fact, up to the early 1960s there was no law to legitimize the activity of the Ausschuss. Until then, the investigations were loosely supported by a military government law dating from September 1949; this, however, covered only the economic aspects of film imports. Additionally, censorship was justified by section 93 of the Strafgesetzbuch (StGB; the ‘German Penal Code’): this section made the distribution of anti-constitutional films a punishable offense. Only in September 1961 was an act established to supervise criminal and other prohibitions of transport: the so-called Verbringungsverbotsgesetz conditioned the general import of films from certain countries on admission and made an assessment obligatory to investigate infringements of constitution, which safeguarded the Interministerieller Ausschuss legally.21

The members of the Ausschuss were well aware of the legal grey area they operated in. Often, in internal meetings, the possibility was discussed to prohibit the screening of films that were rejected for ‘political reasons’ even though there was no legal course of action. Altogether, the political reasons prevailed while legal concerns were put aside, for example when assessing THOMAS MÜNTZER. The members of the Ausschuss agreed that the film was not in confrontation with section 93 of the StGB; still, they voted unanimously against its admission, because in their opinion the film glorified ‘the Peasants’ War in a legally dubious way’ and had ‘a general tendency of fanning the flames’.22

Even though the Ausschuss was able to ban films despite a lack of legal basis and many film distributing companies accepted the restrictions of the Ausschuss without objection for a long time, the public opposition started growing during the 1960s. On the one hand, journalists criticized the questionable activities of the Ausschuss,23 and on the other hand, individual persons started legal actions against the prohibitions of the films. Helmut Söder, for example, an insurance sales clerk from Freiburg in southern West Germany, performed several screenings of the DEFA documentary DER LACHENDE MANN (Walter Heynowski and Gerhard Scheumann, GDR 1966) in West Germany. When he was asked to give his print to the Interministerieller Ausschuss for assessment, he simply refused. The subsequent trial was held in several courts of appeal and eventually, the Bundesverfassungsgericht (‘Federal Constitutional Court’) had to consider not only the case but also the Verbringungsverbotsgesetz itself. This, however, did not happen before 1972 when the Ausschuss had already ceased its activity altogether.24

The increase in public criticism and a new generation of students more sympathetic to Marxist ideas is likely to have contributed to a falling rate in prohibitions from the mid-1960s; additionally, a greater number of films was admitted after a second assessment. Thus, when the Allgemeiner Studentenausschuss (AStA; ‘General Students’ Committee’) at Heidelberg University announced to screen THOMAS MÜNTZER as part of a seminar in 1965, the Ausschuss voted in favour of admission without any restrictions. The students in Heidelberg had criticized the activity of the Ausschuss in public debates several times before and eventually, the Ausschuss gave in to the protests.25

The power of the Ausschuss was generally limited throughout its existence, as the committee was not in full charge of the distribution channels of the film production in West Germany. In the unitary state system of East Germany, the Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (SED) was in full control of not only the production of films but also of the distribution and the presentation in the cinemas; compared to this, the Ausschuss was much less powerful. The censorship system relied on the importers of films—private film production firms as much as broadcast stations, universities and colleges, film clubs and festivals, and even private persons—to provide the Ausschuss their copies for assessment.

It cannot be guaranteed, however, that the importers did so in each individual case. On the one hand, some banned films presented to the public were investigated. In February 1957, for example, the owner of a film store in North Rhine-Westphalia was taken into custody, because he allegedly possessed and showed 260 East German films with ‘communist tendencies’, ten of which had been banned by the Ausschuss.26 On the other hand, there are many records of instances, in which the Ausschuss was informed of a screening too late for an intervention; the print of the film could not be assessed, because it had already been sent back to East Germany. Incidentally, the film DU UND MANCHER KAMERAD was presented in 1957—a considerably long time before the events in Mannheim mentioned above—as part of a seminar at Münster university without the Ausschuss having a chance of prior inspection.27 BERLIN – ECKE SCHÖNHAUSER… was also screened illegally in 1964 when the Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (SDS; ‘Socialist German Student Union’) in München got hold of a print and organized a screening of the film even though it had been banned by the Ausschuss.

These examples show that censorship was not carried out comprehensively by the Interministerieller Ausschuss. Admittedly, the vast majority of films not approved by the Ausschuss, or only under certain restrictions, remained inaccessible to the general West German public. The decision of the Ausschuss had particular significance for commercial presentations in cinemas or in television, since banned films were in fact not aired at all. Yet, apart from that, there were still wide grey areas in which banned films were screened in academic film clubs, associations or other institutions, especially throughout the 1960s when the Ausschuss became subject to increased public criticism.

6. Conclusion: There Is No Apparent Censorship?

The censoring activity of the Interministerieller Ausschuss can be interpreted in two different ways: On the one hand, the competence of the Ausschuss is a significant exemplification of an authoritative conception of the state, which is guided rather by the interests of the government than by the principles of the constitution. The fact that prohibition of censorship was anchored in the Grundgesetz (constitution of the Federal Republic of Germany) was of minor importance for the members of the Ausschuss when it came to decide over a potential ban. The members were dedicated to protecting the people of West Germany from communist propaganda even if there was a shaky legal basis. With its focus on authoritarian tendencies, the analysis of the actitity of the Interministerieller Ausschuss contributes to the critical re-assessment of West German democracy during the 1950s and 1960s.

On the other hand, the history of the Interministerieller Ausschuss can be considered a successful example for overcoming governmental censorship. While the officials were entangled in the ideological debates of the Cold War, a long-term change occurred in West German society: critical media and actions by individuals of the film industry questioned publicly the legitimization of the Ausschuss—of a committee that had its reasons for acting, and ceasing to act, covertly. The change of generations in the 1960s was accompanied by a change in mentality, which made governmental paternalization obsolete.

Along with this process, a general phenomenon can be observed which is quite common in the context of film censorship—regardless of the social background: only the ban made (and indeed still makes) the films truly interesting. In many cases, the decisions by the Interministerieller Ausschuss effected the exact opposite of what they had in mind: even though the general public did not have direct insight into the propagandistic properties of the films banned by the Ausschuss, they were still on everyone’s lips.

- 1Cf. Johannes Roschlau, ed., Kunst unter Kontrolle. Filmzensur in Europa (München: edition text+kritik, 2013).

- 2Cf. Andreas Kötzing and Ralf Schenk, ed., Verbotene Utopie. Die SED, die DEFA und das 11. Plenum (Berlin: Bertz & Fischer, 2015).

- 3Cf. Jürgen Kniep, „Keine Jugendfreigabe.“ Filmzensur in Westdeutschland 1949–1990 (Göttingen: Wallstein, 2010).

- 4Cf. Stephan Buchloh, „Pervers, jugendgefährdend, staatsfeindlich.“ Zensur in der Ära Adenauer als Spiegel des gesellschaftlichen Klimas (Frankfurt/Main, New York: Campus, 2002); Andreas Kötzing, „Zensur von DEFA-Filmen in der Bundesrepublik.“ Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, no. 1–2 (2009): 33–39

- 5Henning Wrage, “DEFA Films for the Youth: National Paradigms, International Influences,” in DEFA at the Crossroads of East German and International Film Culture, ed. Marc Silbermann and Henning Wrage (Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter, 2014), 272; Matthias Steinle, “Visualizing the Enemy: Representations of the ‘Other Germany’ in Documentaries Produced by the FRG and GDR in the 1950s,” in Framing the Fifties: Cinema in a Divided Germany, ed. John E. Davidson and Sabine Hake (New York/Oxford: Berghahn, 2009), 120–136; Sabine Hake, German National Cinema (London/New Xork: Routledge, 2002), 89.

- 6The protocols of the meetings of the Ausschuss are filed in the Bundesarchiv (BArch; German Federal Archives) in Koblenz.

- 7This incorrect information appears for the first time in an article in Der Spiegel giving account of the activities of the Ausschuss in 1956. Cf. „Plädoyer für den Untertan,“Der Spiegel, no. 47, 21.11.1956.

- 8Protocol of a meeting at the Bundesministerium des Innern, Monday, 5th January 1953 raising the issue of the imports of film from countries under Soviet control. BArch Koblenz, B 102/34486.

- 9The last protocol of a meeting of the Ausschuss filed in the BArch in Koblenz is dated 21st February 1967. It is uncertain if there were any more meetings after this.

- 10Buchloh, „Pervers, jugendgefährdend, staatsfeindlich,“ 224–235.

- 11Cf. Kötzing, „Zensur von DEFA-Filmen in der Bundesrepublik,“ 33–39.

- 12The data base is accessible online at www.filmzensur-ostwest.de (German only).

- 13Cf. Michael Wedel, et. al., ed., DEFA International. Grenzüberschreitende Filmbeziehungen vor und nach dem Mauerbau (Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2013).

- 14Cf. short protocol of the meeting of the Interministerieller Prüfungsausschuss in Bonn on 26th May. Bonn, 28th May 1954. BArch Koblenz, B 102/34486.

- 15Short protocol of the meeting of the Interministerieller Prüfungsausschuss in Bonn on 5th June. Bonn, 7th June 1957. BArch Koblenz, B 102/34487. Even in later meetings, there was no admission, cf. the protocol of the meeting 26th June 1957, ibid.

- 16Cf. Andreas Kötzing, „Provozierte Konflikte. Der Club der Filmschaffenden und die Beteiligung der DEFA an der Mannheimer Filmwoche 1959/60,“ in DEFA International. Grenzüberschreitende Filmbeziehungen vor und nach dem Mauerbau, ed. Michael Wedel et. al (Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2013) 369–384.

- 17Short log No. 15/58 of the meeting of the Interministerieller Ausschussfür Ost/West-Filmfragen in Bonn on 6th October 1958. Bonn, 10th October 1958. BArch Koblenz, B 102/34486.

- 18Cf. Kötzing, „Zensur von DEFA-Filmen in der Bundesrepublik,“ 33–39.

- 19On the matter of Carow’s popular-science works, cf. Günter Agde, “Lernen in der Grauzone. Die populärwissenschaftlichen Filme von Heiner Carow (1952–1957),“ Filmblatt, no. 35 (Autumn 2007), 57–64.

- 20Contribution of the BMG to the short protocol, 16th June 1959. BArch Koblenz, B 102/34486.

- 21In an approximate wording of the law, section 5 states: ‘(1) It is prohibited to introduce into the area of validity of this law any films which have the content-related properties to function as a means of propaganda against the free and democratic constitutional order or against the idea of understanding among nations, as long as these films are meant to be distributed. This prohibition shall not be opposed to the processing conducted by the customs services. (2) Any person who introduces any such film into the area of validity of this law must disclose a print of each film to the Bundesamt für Gewerbliche Wirtschaft within one week following the introduction. Films introduced from certain countries may be determined by decree of the Federal Government not to be subject to the duty to disclose.’ Cf. Gesetz zur Überwachung strafrechtlicher und anderer Verbringungsverbote, 24th May 1961. In: BGBl. I, No. 35/1961, 607–608. Only films from the Eastern bloc and Cuba had to be provided for assessment; films from Western countries were generally excluded from the obligatory assessment. Cf. Verordnung zur Durchführung des Gesetzes zur Überwachung strafrechtlicher und anderer Verbringungsverbote, 12.10.1961. In: BGBl. I, No. 84/1961, 1873.

- 22Short protocol of the meeting of the Interministerieller Ausschuss für Ost/West-Filmfragen in Bonn on 6th January 1958. Bonn, 13th January 1958. BArch Koblenz, B 102/34487. The film had previously been banned in December 1956 and in the spring of 1957.

- 23Cf. Reinhold E. Thiel, „Zensur aus dem Hinterhalt – wie lange noch?“ Die Zeit, no. 35/1963, 30.8.1963.

- 24Cf. Buchloh, „Pervers, jugendgefährdend, staatsfeindlich,“ 241.

- 25Cf. Short protocol No. 24/65 of the meeting of the Interministerieller Ausschuss für Ost/West-Filmfragen, in Bonn on 8th July 1965. Bonn, 5th August 1965, BArch Koblenz, B 102/144133. See endorsement by the Bundeswirtschaftsministerium II C 4–28 99 07, subject: Verbringungsverbotsgesetz, Bonn, 16th July 1965. Ibid.

- 26Cf. Short protocol of the meeting of the Interministerieller Ausschuss für Ost/West-Filmfragen in Bonn on 25th February 1957. Bonn, 28th February 1957. BArch Koblenz, B 102/34487.

- 27Cf. Short protocol of the meeting of the Interministerieller Ausschuss für Ost/West-Filmfragen in Bonn on 8th April 1957. Bonn, 11th April 1957. BArch Koblenz, B 102/34487.

Agde, Günter. „Lernen in der Grauzone. Die populärwissenschaftlichen Filme von Heiner Carow (1952–1957).“ Filmblatt, no. 35 (Herbst 2007): 57–64.

Buchloh, Stephan. „Pervers, jugendgefährdend, staatsfeindlich.“ Zensur in der Ära Adenauer als Spiegel des gesellschaftlichen Klimas. Frankfurt/Main, New York: Campus, 2002.

Davidson, John E., Sabine Hake, ed. Framing the Fifties: Cinema in a Divided Germany. New York/Oxford: Berghahn, 2009.

Hake, Sabine. German National Cinema. London/New York: Routledge, 2002.

Kniep, Jürgen. „Keine Jugendfreigabe.“ Filmzensur in Westdeutschland 1949–1990. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2010.

Kötzing, Andreas. „Zensur von DEFA-Filmen in der Bundesrepublik.“ Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, no. 1–2 (2009): 33–39.

Kötzing, Andreas. „Der Bundeskanzler wünscht einen harten Kurs...“ Bundesdeutsche Filmzensur durch den „Interministeriellen Ausschuss für Ost/West-Filmfragen.“ In Kunst unter Kontrolle. Filmzensur in Europa, editd by Johannes Roschlau. München: edition text+kritik, 2013: 148–159.

Kötzing, Andreas. „Provozierte Konflikte. Der Club der Filmschaffenden und die Beteiligung der DEFA an der Mannheimer Filmwoche 1959/60.“ In DEFA International. Grenzüberschreitende Filmbeziehungen vor und nach dem Mauerbau, edited by Michael Wedel et. al. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2013: 369–384.

Kötzing, Andreas. Kultur- und Filmpolitik im Kalten Krieg. Die Filmfestivals von Leipzig und Oberhausen in gesamtdeutscher Perspektive. Göttingen: Wallstein, 2013.

Kötzing, Andreas, and Ralf Schenk, Ralf, eds. Verbotene Utopie. Die SED, die DEFA und das 11. Plenum. Berlin: Bertz & Fischer, 2015.

Roschlau, Johannes, ed. Kunst unter Kontrolle. Filmzensur in Europa. München: edition text+kritik, 2013.

Silbermann, Marc, and Henning Wrage, eds. DEFA at the Crossroads of East German and International Film Culture. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter, 2014.

Steinle, Matthias. “Visualizing the Enemy: Representations of the ‘Other Germany’ in Documentaries Produced by the FRG and GDR in the 1950s.” In Framing the Fifties: Cinema in a Divided Germany, edited by John E. Davidson and Sabine Hake. New York/Oxford: Berghahn, 2009: 120–136.

Thiel, Reinhold E. “Zensur aus dem Hinterhalt—wie lange noch?“ Die Zeit, no. 35, 30.8.1963.

Wedel, Michael et. al., ed. DEFA International. Grenzüberschreitende Filmbeziehungen vor und nach dem Mauerbau. Wiesbaden: Springer VS, 2013.

Wrage, Henning. “DEFA Films for the Youth: National Paradigms, International Influences.” In DEFA at the Crossroads of East German and International Film Culture, edited by Marc Silbermann and Henning Wrage. Berlin/Boston: de Gruyter, 2014: 263–280.