Be Part of History

Documentary Film and Mass Participation in the Age of YouTube

Table of Contents

Liberated on Film

Mexican Public Health History through Film

Reel Life

Film as Instrument of Social Enquiry

Visibility and Torture

Trapped in Amber

Be Part of History

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Petraitis, Marian: Be Part of History: Documentary Film and Mass Participation in the Age of YouTube. In: Research in Film and History. Research, Debates and Projects 2.0 (2019), No. 2, pp. 1–19. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/14802.

An increasing number of online documentaries are challenging the understanding of film in general and the term 'documentary' in particular. There are whole new landscapes of documentary projects that use different media to present their visual content and address the viewer through a variety of platforms. These projects also involve new interactive components as well as increased participatory and collaborative options for engaging the viewer in the production process. The results are new media practices that allow the viewer to co-create documentaries as active users, not only contributing visual content but actively shaping the projects along the way. While new forms are evolving at a rapid pace, and simultaneously raising questions about traditional epistemologies, researchers are particularly interested in trying to understand how the additional interactive, participatory, and collaborative options redefine our understanding of documentary. To get a better understanding of current developments in documentary, it may be helpful to take a look back. As Patricia Zimmerman and Helen De Michiel point out in their book Open Space New Media Documentary, the rise of participatory and collaborative filmmaking is by no means a new phenomenon of the digital age, but is entangled with a century of documentary history1 and has manifested in several theories of documentary, probably most prominently Bill Nichol’s concept of the participatory mode of documentary.2

In this paper, I focus on a number of online documentaries that I class not solely as participatory, but as mass participation documentaries.3 I do so not to undermine the theoretical and historical implications of the first term, but in order to expand on it and include a connection that has only rarely been drawn: namely, to mass participation projects, and in particular to Mass Observation. Mass Observation, an interdisciplinary research project begun in 1937 by the anthropologist Tom Harrisson, the writer and sociologist Charles Madge, and the documentary filmmaker Humphrey Jennings, examined everyday life in Britain on a single day, the date of George VI’s coronation. The idea was to collect diverse material provided by ordinary people, referred to as “observers.” The material ranged from diaries, questionnaires, and transcripts of conversations to poetry and other media. The project became a long-term endeavor, continuing until the mid-1960s, and was then revived again in the 1980s and has since run until the present day. Originally framed as an “anthropology of ourselves,” Mass Observation has become an increasingly valuable historical source documenting the shifts in everyday life in Britain. Mass participation documentaries not only take similar methodological approaches to Mass Observation, but also share the anthropological goal of depicting everyday life in ways that potentially offer a unique historical perspective that differs from “official,” institutionalized historical narratives.

The present article takes a closer look at how these mass participation documentaries, which rely heavily on participation and collaboration by large numbers of users, shape historical conceptions, and asks to what extent they can serve as useful historical documents. My argument is that mass participation documentaries differ significantly in terms of both their openness to new perspectives on historiography and documentary film and their actual value as historical documents. However, almost all of them are clearly concerned with “history,” emphasizing their own historical value as unique documents of collective filmmaking.

The article begins by briefly contextualizing the emergence of new forms of documentary closely connected to Web 2.0 and the rise of media platforms such as YouTube, looking at the amateur practices and vernacular creativity surrounding these platforms and their historical predecessors. Subsequently, it takes a closer look at how mass participation projects might become valuable documents for a historiographical perspective, focusing on how the projects claim to be part of meaningful historical campaigns and therefore establish a self-proclaimed monumentality. I then introduce a theoretical framework (drawn from recent academic debate) in order to undertake a comprehensive analysis of these projects. I discuss concepts such as polyphony and heteroglossia and introduce microhistorical approaches and polyvocal historiographies. Subsequently, the article maps out two different groups of mass participation documentaries, focusing specifically on the differences in their understanding of and approach toward history.

Emergence of New Documentary Forms

Mass participation documentaries can be seen as part of a large-scale development that emerged alongside the rise of new documentary forms online, which in turn began more than a decade ago. In their article “‘This Great Mapping of Ourselves’: New Documentary Forms Online,” Jon Dovey and Mandy Rose trace this development back to the emergence of Web 2.0. In their view, most of the characteristics that define this new online environment merely continue or intensify already-existing cultural phenomena. However, they also point out that major new developments can be closely linked to the online environment, the new platform of media production:

As a platform, online is a new site where all kinds of media material including documentary can be uploaded and potentially seen. […] Our contention is that the 'processes’ of documentary production can change through new forms of collaboration, and that, in fact, the 'forms’ of documentary are changing through software design and interactivity, and the 'user experience’ of documentary can change through the new facility for participation offered by the online environment.4

This article was published back in 2013, and in just these past few years new documentary forms have evolved with rapid speed. Nonetheless, this short passage contains several terms that remain central to the current discussion. I want to focus on the new possibilities made available by this changed role of the viewer as user, especially with regard to collaboration and participation. This is something Dovey and Rose themselves directly link to the concept of the vernacular video, a term that they derive from Jean Burgess and Joshua Green’s notion of vernacular creativity, which is defined as “the wide range of everyday creative practices […] practiced outside the cultural value system of either high culture or commercial creative practice”.5 Connecting the idea of vernacular creativity to filmic practices quickly raises the question of possible predecessors, which Dovey and Rose answer by naming three historical sources: the visions of the avant-garde movement (such as Alexandre Astruc’s idea of the caméra-stylo), the practices of amateur film, and the “camcorder cultures” of the 1990s.6

As Zimmermann and De Michiel have shown in their analysis of participatory documentary practices, this is by no means a conclusive list of predecessors.7 It will prove valuable to think further about the link between amateur practices and new forms of documentaries from a historiographical perspective. Simon Rothöhler explores the connection between historiographic practices and contemporary cinema in Amateur der Weltgeschichte.8 He establishes an understanding of film as an amateur medium for historiography, a notion that might prove useful in the future.

I want to argue that although documentary forms have rapidly evolved beyond YouTube (while YouTube itself has transformed from a new and experimental media platform that allowed vernacular creativity to an increasingly commercial “mainstream” media platform), the connection between certain new forms of documentary and media platforms such as YouTube (and related concepts such as vernacular video and amateur practices) is worth examining more closely. Furthermore, I think that documentary projects that take a mass participatory approach are particularly productive research subjects. They invite large numbers of users to actively engage in amateur practices as part of a participatory and collaborative act of filmmaking. These collaborative efforts are particularly invested in the idea of creating historical documents, a historiographical ambition worth taking a closer look at.

Creation of History and Self-Proclaimed Monumentality

Mass participation projects are explicitly concerned with the “creation of history” and often make this ambition explicit to users. They allow users to take part in a significant, meaningful campaign, as well as declaring the project’s own historical value. Consequently, prior to any actual collection of content, they often prematurely predict that this content will be a rich source for a unique historiographical approach. Many mass participation projects thus create an ambivalence: they point at their own importance as historical documents and at the same time provide critics with arguments against it, including an (often aggressively) anticipated, self-proclaimed monumentality.

It should be noted that the value of new documentary forms for historiographical perspectives is still in the process of being uncovered and acknowledged. Following on from Stefano Odorico’s workshop on “i-docs as a research method,” which took place at the University of Bremen in 2017, and the 2018 edition of the annual i-Docs Symposium in Bristol, a special issue of the journal Alphaville was released.9 The issue focuses on the potential engagement inherent within interactive documentaries (or i-docs), a term often used to describe a range of new documentary forms,10 and Mikhail Bakhtin’s expanded concept of polyphony. The adaptation of polyphony to the documentary field (Bakhtin originally introduced the term with literary studies in mind) can be seen as an attempt to establish a theoretical framework capable of dealing with new structures, production processes, and, especially, the multiple voices that continuously interact with one another in the ongoing creation of content for online documentaries.

In “The Poetics and Politics of Polyphony: Towards a Research Method for Interactive Documentary,” Judith Aston and Stefano Odorico sketch out this framework, alongside certain other concepts. Based on the adaptation of polyphony to documentary, they suggest also incorporating Bakhtin’s idea of heteroglossia into the analysis of i-docs. Heteroglossia refers to the coexistence of and conflict between different types of speech that challenge a monologic authorial voice.11 Bakhtin reflects on literature, especially Dostoevsky’s work and the use of dialogue to allow different social styles to be presented through different characters (which then in turn establishes polyphonic and multivocal novels). Aston and Odorico, meanwhile, see great potential in further investigating how different types of speech form heteroglossia within new documentary forms.

The introduction of polyphony and heteroglossia to documentary proves useful in two ways. First, these notions are connected to pivotal concepts of documentary theory, most notably to Bill Nichol’s notion of the voice of documentary.12 Second, they have the potential to expand this concept and help to better describe how interactive components and the increased participatory and collaborative options in new documentary forms challenge the hierarchies in both production and consumption of documentary, replacing authorial voices with multivocal arrangements. It is especially intriguing to further examine how i-docs (most of them mass participation projects that heavily rely on collaboration and participation by users) arrange the different voices contained in their diverse material.

Consequently, i-docs draw on increasingly open and fluid structures that emphasize spatial categories, using factors such as proximity and distance to translate these relational aspects as well as the increasing entanglement of voices on the screen. In doing so, i-docs move further away from a “classic” linear documentary form and instead open up new stylistic possibilities, which Aston and Odorico believe are directly related to Nicolas Bourriaud’s thinking on relational aesthetics and Umberto Eco’s concept of the open work. These projects then tend to produce new multiplicities in terms of aesthetics, narratives, authors, realities, and so forth.13 In their provocative conclusion, Aston and Odorico propose thinking of new documentary forms such as i-docs in terms of “chronotope-ical 'roads’” in order to better understand how these projects function. I shall return to Aston and Odorico’s notion of chronotopical roads later on in my discussion of Alisa Lebow’s FILMING REVOLUTION (UK 2018), part of the second group of mass participation documentaries.

In “Thirty Speculations toward a Polyphonic Model for New Media Documentary,” Patricia Zimmermann observes that looking at new documentary forms through polyphony is especially valuable from a historiographical perspective. While most of her previous speculations relate to historiography indirectly, four of them do so explicitly. She describes the potential of what she calls “new media documentary” as the ability to tell “microhistories from below,” which in turn feature multiple voices provided by ordinary people. These voices simultaneously operate as both subjects and objects and institute a “polyvocal and radical historiography.”14 They do so within heterogeneous and hybrid structures, thus establishing a new way of thinking about the historical system of colligation, contiguity, and synchrony. These reflections are continued in Open Space New Media Documentary. In the chapter entitled “Small Places,” Zimmermann and De Michiel claim that open space documentaries shift away from grand, large- or national-scale narratives, which puts them in a microhistorical tradition that tends to be situated in local topographies in order to tell more fragmented, heterogeneous, and possibly contradictory everyday life stories that allow multiple voices to be heard.15 For Zimmermann and De Michiel, the focus on polyphony means these documentaries are closely related to the ideas of postcolonial historiographers such as Dipesh Chakrabarty, who favors a minority history approach that emphasizes working-class, nonwhite, nonwestern, and women subjects, as well as to polyvocal historiographical accounts like those of Robert Berghofer, who adapts multiculturalist and feminist approaches to call for a hybrid structure that enables an interplay of voices that are able to function simultaneously as both subjects and agents.16

I shall not attempt here to verify or refute these speculations, nor shall I solely focus on the term interactive documentary, since not all of my examples precisely fit that category. Instead, this article introduces some examples that all share a similar approach toward mass participation, which then can be linked to certain aspects of both Aston/Odorico’s and Zimmermann/De Michiel’s reflections. My intention is to make a contribution to the ongoing debate on how to understand new documentary forms, especially their potential to shape historical conceptions and institute historiographical approaches that involve polyphony and heteroglossia. The article goes on to map out two different groups of mass participation documentaries.

LIFE IN A DAY: Global Carnival or World History?

The first group of mass participation documentaries emphasize the “creation of history” in an act of collaborative filmmaking and point out their consequent value as historical documents. At the same time, these projects are particularly invested in the creation of homogeneous temporality as part of a collectively shared experience. The first example LIFE IN A DAY (UK/US 2011) is a documentary directed by the British filmmaker Kevin Macdonald. However, it is also a YouTube project, and was the platform’s very first attempt to create a full-length documentary. YouTube took a mass participation approach in which its users were invited to contribute the visual material themselves. The company launched a widespread campaign that announced the intention behind the documentary (namely, an attempt to capture a snapshot of life on earth) and asked users to film and record their everyday lives on a specific date (July 24, 2011) and then submit their clips. YouTube advertised the campaign with the slogan “Be Part of History,”

emphasizing the historical value of the project and framing a singular day in the summer of 2011 as a significant global and collaborative event.

The production process for the film involved a daunting amount of work: a team of twenty people reviewed more than 80,000 video clips sent in by users, equivalent to a combined total of 4,500 hours of material, which was ultimately condensed into a documentary film with a running time of 95 minutes.17 This documentary was then shown in cinemas around the world and simultaneously made available on YouTube.

The film groups the polyphonic and heterogeneous material under larger themes, such as love, hope, hate, and fear. It thus draws on a predefined structure that was created by prompting users to ask several questions on the day of the filming, such as “What are you afraid of?” and “What is in your pocket?” While the film occasionally dives into personal stories of particular individuals and depicts specific events, for example the tragic mass panic at the Love Parade in Duisburg that took place that day, it keeps coming back to these broader, emotionally charged themes. The film also repeatedly focuses on globally shared daily routines, which provide LIFE IN A DAY with a second layer, emphasizing its focus on temporality and expanding the project’s self-proclaimed monumentality. Early in the film, we are confronted with a montage depicting a repertoire of everyday practices, e.g. morning routines such as waking up, brushing teeth, preparing breakfast, drinking coffee. The initially minimalistic but later increasingly foregrounded musical score supports the appealing rhythm of gestures. This arrangement not only succeeds in forming a connection between the seemingly contingent mass of images from everyday life, but also injects a certain pathos into this one random day on planet Earth. It establishes a poetics of the everyday on a global scale; a sort of awakening of the world on day X. Moreover, it fosters an intriguing awareness of the passage of time as a main structural element of the everyday.

The multiple realities and voices contained in the raw material are ultimately transformed into a common, unifying human experience that positions itself on a global scale and manifests a shared rhythm of everyday life. LIFE IN A DAY thus ultimately does not transform the polyphonic material into heteroglossia as described by Aston and Odorico. Instead, the film establishes a humanist yet homogeneous and monologic voice through montage and a unifying musical score, and in doing so mainly rejects contradictions between, or even the coexistence of, different voices, as well as the idea of dialogue.

Some might still see LIFE IN A DAY as an attempt to contribute to world history by connecting vastly different experiences in one film project. Yet it is maybe more accurately characterized as part of a group of documentaries, such as 7 BILLION OTHERS (DE, EL, EN, ES, FR, IT, PT, RO, RU, ZH, 2003), that – as Dovey and Rose point out in their analysis of the poetics of collaboration and participation – all assimilate into universalist views of the conditio humana, creating a sort of “one-world-ism” rather than having any specific historical value.18

I argue that LIFE IN A DAY is primarily concerned with its own temporality, monumentality, and historicity, which are all unified under the conception of a globally shared experience of the everyday. It thus came as no surprise that the project received a lot of criticism for its universalist approach. YouTube was seen as a gatekeeper of the everyday, choosing to depict a dominantly Western perspective on this human experience. As a result, LIFE IN A DAY also lacks value for the kind of postcolonial or polyvocal historiography discussed by Zimmermann and De Michiel.

However, it is also possible to consider the project in terms of another Bakhtinesque notion discussed in Aston and Odorico’s article – carnival:

Carnival is not a spectacle seen by the people; they live in it, and everyone participates because its very idea embraces all the people. While carnival lasts, there is no other life outside it. During carnival time life is subject only to its laws, that is, the laws of its own freedom. It has a universal spirit; it is a special condition of the entire world, of the world’s revival and renewal, in which all take part. Such is the essence of carnival, vividly felt by all its participants.19

According to Aston and Odorico, carnival offers an ideal environment for exercising polyphony and heteroglossia, because it offers freedom of speech, a sense of openness, and a spirit of equality that create the potential for everyday life to be subverted from within. Bakhtin’s concept of carnival as a constant in cultural history can be productively adapted for an analysis of new documentary forms. It offers an insight into how the appeal of certain mass participation projects is constructed in the age of YouTube. LIFE IN A DAY might thus be better understood as part of a wider user experience. This experience is, again, connected to a media platform that, through various projects including a documentary film, promises to offer a unique, “carnivalesque” environment. On a provocative note, LIFE IN A DAY and the restriction it places on its users could be seen as part of a regulated “corporate carnival”: YouTube sets the rules for the carnival and demands compliance, which raises fresh questions about the project’s actual potential for subversion.

In that context, interdisciplinary connections can be identified, especially between mass participation projects that go beyond the medium of film. In the case of LIFE IN A DAY, a direct inspiration can be found: director Kevin Macdonald said that the idea for the film project can be traced back directly to Mass Observation. The influence Mass Observation has had on vernacular creativity can also be seen in the BBC television project VIDEO NATION (UK 1994–2000), which called on viewers to record their everyday lives in the form of video diaries taken on camcorders.

Accordingly, it might prove valuable to look at Mass Observation’s connection to surrealism and its ultimate aim of transforming the presentation of everyday life by giving a voice to groups that were previously marginalized within society. Its unique approach toward history includes a scientific ambition to conduct a long-term project relying on a great variety of media practices. Furthermore, it shares with microhistorical methodology and polyvocal historiography the aim of portraying the life of “ordinary” British people. While LIFE IN A DAY is not entirely successful in adapting these methodological approaches to documentary film, I would like to suggest that a closer examination of Mass Observation in relation to documentary can reveal essential connections, including to mass participation documentaries in general.20

Real-Time Documentaries: Experience History Live As It Is Happening?

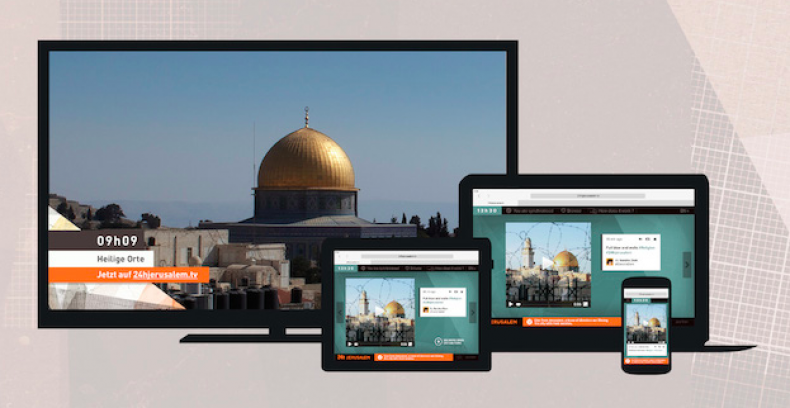

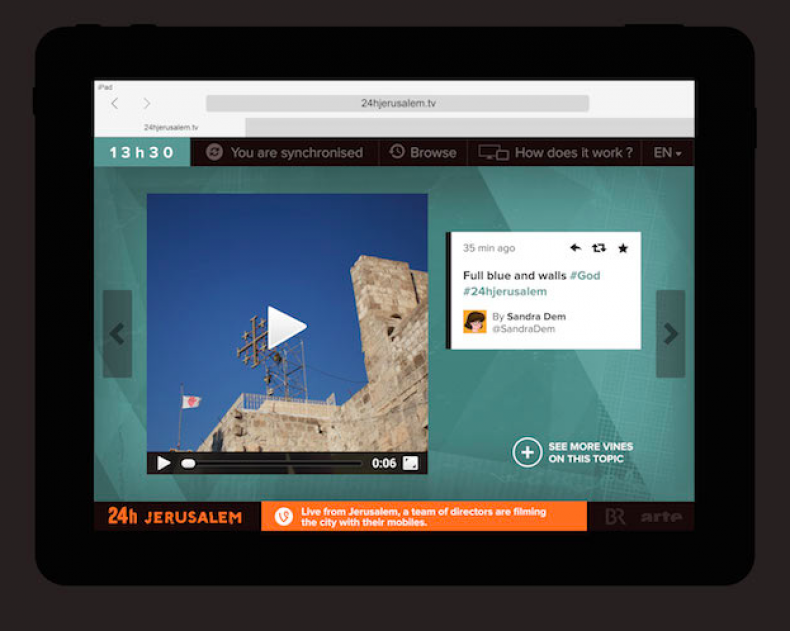

Another connection to Mass Observation can be seen in “real-time documentaries,” which also fall in the first group of mass participation documentaries: for example, 24H BERLIN (DE/F 2009) and 24H JERUSALEM (DE/F 2014), produced by the Franco-German TV network ARTE. These projects also cover a single day; however, in this case the compiled material accumulated to a running time of 24 hours, which was then broadcast nonstop on one specific date. These documentaries thus give the viewer an illusion of real time, which of course is not the case, since the material was actually recorded one year in advance. However, the viewers were encouraged to submit videos of their own activities during the broadcast in order to take part in the seemingly “live” event. While the users were only able to participate at certain points in the production process, additional emphasis was placed on their importance as viewers: history is happening right here and now, “live,” and you can be part of it by watching it happen!21 This was primarily a business strategy, but also one that provides a hybrid between television and connectedness, which in turn is made possible by the Web.

These projects went to great lengths to create their portraits of a modern city. In the case of 24H JERUSALEM, eighty different film crews contributed more than 750 hours of visual material.22 They offer diverse perspectives on individual residents, who expand on their life stories in interviews and through dialogue, and give a detailed insight into their daily routines on a specific day. 24H JERUSALEM thus takes a microhistorical approach as described by Zimmermann and De Michiel, in that it closely sticks to a local topography and uses the observation of the residents’ everyday lives as a way to explore their histories. Furthermore, it arranges these microhistories not as part of an enclosed narrative that tells a “bigger” story, but rather uses a mosaic structure to present loosely connected parts, at times “zooming in and out” of certain stories: a narrative structure of heterogeneity and fragmentation that, in the view of Zimmermann and De Michiel, ultimately enables polyphony.23 More importantly, though, these documentaries are structured such that every half hour the material is interrupted by extreme long shots that show the city as the actual, central protagonist of the project. As emphasized by the accompanying sound, it is the very pulse of the city and the passage of time that are being repeatedly drawn into focus.24

Moreover, real-time documentaries are comprised of media events that claim to mark the point at which everyday life transitions into “history,” thereby emphasizing the processual quality and adding a monumental gravitas to the projects. History thus becomes an irreversible, directional process, and the projects are less concerned with the actual telling of a bigger narrative composed of microhistories than with reflecting on the temporality of such a collaborative event and proclaiming its monumentality. In her article on 24H BERLIN, Britta Hartmann uses the term “anticipated historiography,” which seems a particularly apt description of the phenomenon. She also uses the concept of “déjà disparu” to emphasize the fascination surrounding these projects. This notion is adapted from Ackbar Abbas’s work on literature, which describes the impression of the dissolution of a culturally significant object as the feeling that the new and unique part of a moment is always immediately lost as soon as we become aware of it.25 The implied emphasis on processuality is also underlined in an interview with Volker Heise, the creator of both of the aforementioned real-time documentaries: “Es wird nichts bleiben, und das haben wir festgehalten.”26 – Nothing will remain, and that is what we captured.

In framing the processual qualities of real-time documentary as the ability to experience the passage of time, 24H JERUSALEM ultimately shares the idea of self-proclaimed monumentality with LIFE IN A DAY. Its focus on rhythm again creates a homogeneous temporality that works as a unifying force. LIFE IN A DAY aims for the largest possible scale as it tries to grasp a rhythm of everyday life as a conditio humana. 24H JERUSALEM begins on a much smaller scale by collecting microhistories of a city that are then presented in a mosaic structure. Nevertheless, it synthesizes these microhistories into a repetitious montage, to the shared pulse of an anthropomorphic, “living” city.

Beyond Carnival – Toward Revolution and Authorship

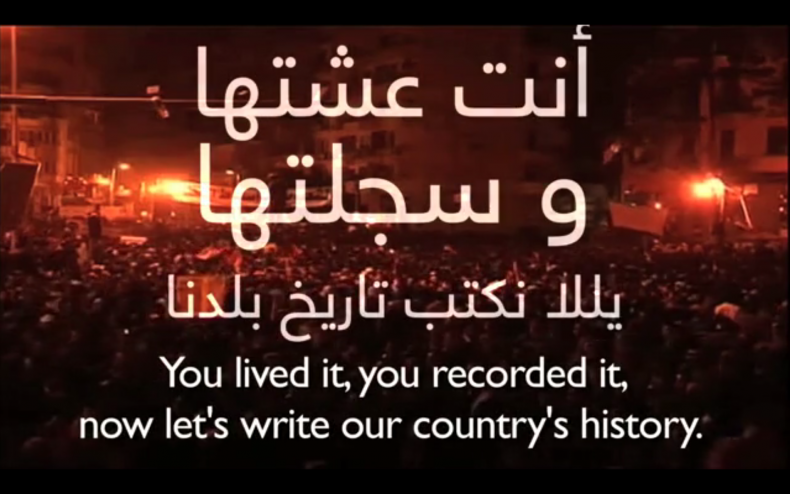

A second group of mass participation documentaries also make use of the interdependence between a call for participation and the emphasis on historical value, though for different reasons and in ways adapted to their own specific contexts. One of them is 18 DAYS IN EGYPT (US 2011), a Web-based documentary that deals with the Egyptian revolution during the Arab Spring. The creators of the project asked users to submit photos, videos, Facebook posts, and Tweets that were taken or written during the revolutionary days of the Arab Spring. To encourage them to do so, the creators addressed the audience as both amateur filmmakers and historiographical agents: “You lived it, you recorded it, now let’s write our country’s history.”

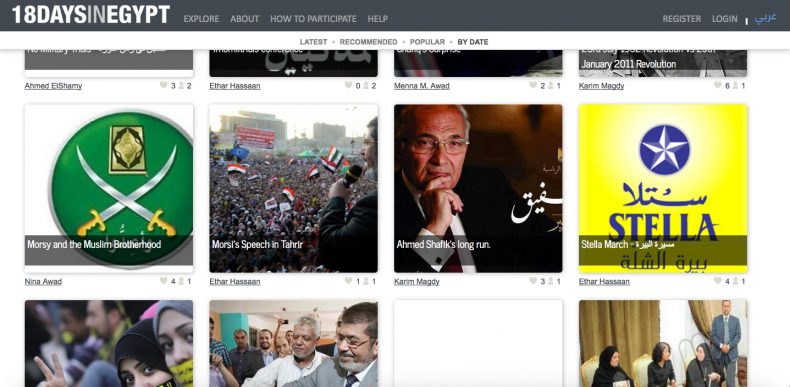

Furthermore, they offered the users even more potential involvement in the creation of the project itself through its emphasis on polyphony. YouTube vastly limited the possible participation of users in LIFE IN A DAY by inviting them to contribute content but simultaneously excluding them from any further production processes. Users of 18 DAYS IN EGYPT, by contrast, were able to access a database containing the submitted material. They were then invited to create their own short films called “stories” using this material and upload them to the database, where they would be shared with the community.27

For 18 DAYS IN EGYPT, a media platform was created to give the users a voice on two levels: a voice of authorship, involving them in the decision-making process; and a voice-as-social-participation, highlighting the relationship between audience practices and social discourse and their ability to connect and engage with each other.28 Additionally, it can be understood as an attempt to establish a new environment for vernacular creativity through dialogue. While this certainly amounts to a wider range of participation, I argue that it is only one aspect that differentiates this example from the above-mentioned documentaries. As part of the historiographical campaign, the project additionally insists on the ontological status of the images as visual documents, as testimonies of and witness to otherwise unseen realities that take place during revolutions and wartime, within a climate of oppression and censorship.

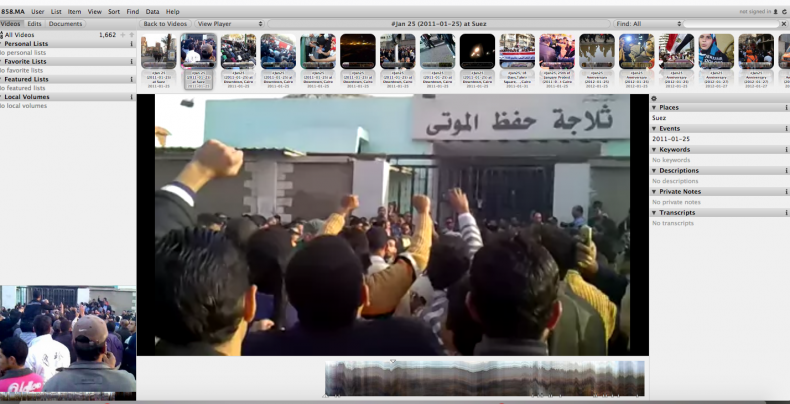

Another, more recent example is 858.MA, a website launched in 2018 by the Egyptian collective Mosireen, which collected 858 hours of uncut visual material showing events surrounding the revolution.29 The videos were mainly taken on cell phones by local residents directly involved in the revolution. The website design mimics the structure of a hard drive yet functions as a self-proclaimed “archive of resistance,”

establishing a fully searchable database with multiple tags that allow users to filter and select material relating to a specific location or event. While the project provides users with fewer participatory options than 18 DAYS IN EGYPT, it gives a voice to the hundreds of people who took the videos in the first place, offering a radical, microhistorical perspective on everyday life during the Arab Spring. Zimmermann and De Michiel see a similar approach in a number of documentary projects dealing with the ongoing civil war in Syria. In their analysis of ABOUNADDARA, a platform initiated in 2011 and named after a Syrian collective that produced videos of everyday life, they describe these videos’ historiographical ambition as follows: “These videos elaborate not only a micro rather than macro history, but also foreground small scenes of homes, particular streets, and specific places as productive sites of survival and memory.”30 By doing so, projects such as ABOUNADDARA and 858.MA share similar historiographical ambitions to 18 DAYS IN EGYPT. But they also have the same problematic open structure and at times overwhelming amount of visual content, which in turn raises questions about additional curation: who will see all of this vast and diverse material and who will be able to make sense of it? Although the open structure enables ways of arranging heterogeneous material and emphasizes the multiplicity of voices and realities, as a result it faces a problem of curation. Since the films are predominantly amateur videos confronting the viewer with “raw” visual impressions, often without any further explanation, the material requires a high level of prior knowledge on the part of the viewer. Ultimately, the lack of context can threaten the status of the images as documents, not because the images do not show what might have happened, but because the viewer might not be able to decipher it.

In an interview with the newspaper Die Zeit, a member of the Mosireen collective states that their goal with 858.MA was not to establish a fixed narrative of the revolutionary days, but to create a space for visual evidence that counters the official historical narratives established by the acting regime, who still deny most of the depicted violence and massacres.31 The battle over visual images had thus already turned into a battle over the correct historiography of the event. These two examples show that the analysis of historiographical campaigns and the way the projects shape historical conceptions cannot be reduced to their participatory options but instead have to be looked at in terms of how they present and connect the visual material they have collected, and how they define their ontological status within these projects. In the end, creating a polyphonic environment with increased accessibility might even threaten the comprehensibility of the content.

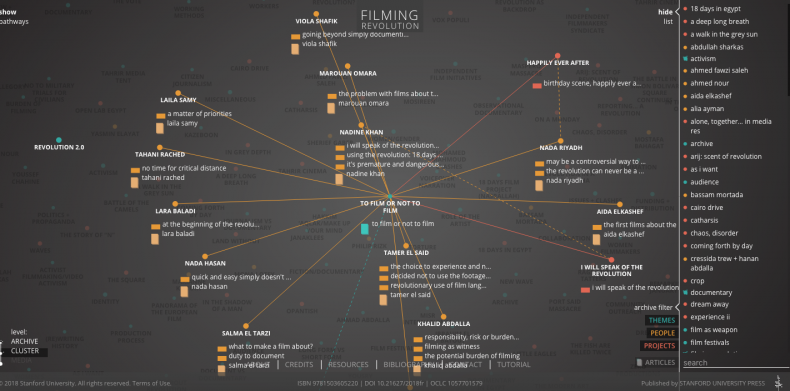

Consequently, a number of i-docs are currently trying to find new visual solutions for the inevitable encounter with the polyphony of their collected material. For example, Alisa Lebow’s FILMING REVOLUTION (2018), a self-proclaimed “meta-documentary” about filmmaking in Egypt during the revolution.32 Lebow went to Egypt during the aftermath of the 2011 revolution in order to talk to over thirty filmmakers, artists, activists, and historians about how their practices have changed as a result of the events surrounding the revolution. The website presents the collected material within a multilayered, rhizomatic structure that highlights interconnections between them.

In doing so, the project not only finds innovative ways to highlight multiplicity on different levels, but also comes close to what Aston and Odorico describe as “chronotope-ical roads.” By emphasizing space and establishing “roads” that function as connecting lines within the otherwise contingent assortment of visual material, FILMING REVOLUTION makes it possible to tell new and different (hi-)stories about these events while highlighting the relational aspects of the heterogeneous material through the website’s interface. The project can thus be seen not just as a metadocumentary about filmmaking, but also as a project that – through its nonlinear, rhizomatic structure – reveals the multitude of approaches taken toward an event that is in the process of becoming part of history. Polyphony is enabled and made visible not by montage, but by design choices in the creation of the website.

SILVERED WATER: 1,001 Voices, One Conversation

While FILMING REVOLUTION offers a glimpse of the potential for new documentary forms to create a polyphonic environment, the final example discussed here is not an i-doc but a film that ultimately emphasizes the unique abilities of the essay film. MA’A AL-FIDDA or SILVERED WATER, SYRIA SELF-PORTRAIT (F/SY/US/LB 2014) is a film about the Syrian Civil war directed by Ossama Mohammed and Wiam Simav Bedirxan. It largely consists of video material that was uploaded to YouTube and “shot by 1,001 Syrians,” as the filmmakers put it at one point in the film. In contrast to LIFE IN A DAY, which called for active participation by its users, SILVERED WATER largely builds on footage that was found on and taken from YouTube by Mohammed. Hence, the filmmaker’s voice and his relationship to the found images of violence, torture, and devastation and his reflections on the people in front of and behind the cameras are made the main focus of SILVERED WATER. Consequently, the film is more than a raw compilation of “digital found footage,” and instead functions as a form of mourning by Mohammed, a filmmaker witnessing the civil war from his exile in Paris, who collects these amateur videos in an attempt to get in touch with his homeland and its people. Over the course of the film, the “conversation” about found footage evolves into a dialogue between Mohammed and Bedirxan, an elementary school teacher in the besieged city of Homs, who in turn starts to record the dissolution of her hometown herself and gets in touch with Mohammed to ask how she should approach the atrocities of war that she is witnessing.

The film refrains from compiling the images to create a sense of a common experience. Instead, it depicts the deeply personal mourning experienced by Mohammed, and also touches on the issue of recording and uploading video clips, which in this case is a survival tactic for people who find themselves living in the center of a war zone. The ambition to enable a conversation about experience is further emphasized by the voice-over provided by Mohammed and Bedirxan, in which they engage in a literal conversation about these vastly different experiences. This collaborative aspect of the film does not result in polyphony in the sense of democratization of the narrative, nor does it form a heteroglossia that treats all voices equally; instead, it can be seen as an argument about the capabilities and limitations of documentary itself. Although the film at times allows images to speak of brutality and death, torture and pain, thereby providing visual testimonies of individuals (which include both victims and perpetrators), its central argument is ultimately concerned with the power structures contained in those images.

In a scene toward the end of the film, the relationship between Mohammed, Bedirxan, and “the people of Syria” is shown to be a complex structure of interdependences. We see a young boy strolling around the ruined city of Homs, in constant danger of being shot, and Bedirxan, who is following him with her camera. The multilayered audio track includes a voice-off by Bedirxan, who is talking to the boy, while the viewer simultaneously hears gunshots in the background. The scene thus gives a glimpse of the tense, life-threatening atmosphere surrounding the pair. A voice-over by Bedirxan and Mohammed has also been added in which they try to make each other understand how they feel. As the danger increases, Bedirxan starts to read out percentages, which can be understood as the progress of her uploading the video. At this point, the film draws a parallel between the imminent danger of death and the submission of a video to the Web, dramatically urging the viewers to take the images as documents of survival.

SILVERED WATER consequently serves as a reflection on what cinema is and can be in times of war and devastation, as well as on the historicity of the filmic material itself. Throughout the scene, we also hear an ambient rattling (clearly added in postproduction) that simulates the sound of an old film camera. Shortly after a moment of imminent danger – Bedirxan and the boy hastily cross a street, under threat of being shot by a sniper who they believe is targeting them – we see a close-up of the steps of an escalator, probably shot in exile by Mohammed. This shot is intertwined with the computational sound of successfully uploaded video clips. This arrangement exemplifies the status of “digital found footage”; visual testimonies that strive for visibility and the hope of being seen (and heard) in exile. Furthermore, it is this precise arrangement of sounds that ultimately reveals the capabilities and limitations of film in times of war: film as witness and testimony, and film as a medium for reflection on how documentary practices can mediate lived experience. These themes, however, are not solely restricted to the age of YouTube: instead, they are historical constants that reveal the very core of documentary.

Conclusion

By mapping out two groups of documentaries, this article has hopefully made clear that while all of them are invested in the “creation of history,” the examples vary significantly in their actual historical value. The first group is especially interested in the creation of a self-proclaimed monumentality and a homogeneous temporality through rhythm, resulting in an idea of shared experience. These documentaries are less concerned with the production of any actual historic value and more with the filmic potential to make the passage of time perceptible (although the microhistorical approach of real-time documentaries can to some extent prove a valuable source for studying the history of certain places). Meanwhile, the films in the second group, situated in times of revolution and war, insist on their historic value as visual documents, and call for viewers to see them as visual testimonies of and witness to devastation, violence, and suffering. What differentiates the two groups is the ontological status of the heterogeneous documentary images: while the first group uses the potential of moving images for a reflection on temporality, the second is primarily concerned with their status as documents.

Furthermore, the projects differ in the collaborative and participatory options they offer their users, as well as in their narrative structures. The examples show that different microhistorical approaches and emerging documentary forms enable new ways of thinking about how to arrange visual material so that the multiplicity of voices contained in the contingent, raw material might retain its polyphonic character in times of mass online participation. However, the analysis shows that creating polyphony within new, open, and hybrid structures cannot be a matter of a simple formula for how to create productive histories. The form and structures provide great potential for telling histories in new, exciting, and enriching ways, but they also bring certain problems and limitations with them, especially when it comes to questions of contextualization and curation, and in times of increasingly large quantities of documentary content online. Future projects that claim to be creating history might, then, best be analyzed not only in terms of what participatory or interactive options they offer to users or whether they establish a polyphonic environment, but also how they ultimately connect their heterogeneous material – whether through film montages or design choices for interactive websites – in order to create meaning and to improve the argumentative power, accessibility, and interactivity of the collected material.

- 1Zimmermann and De Michiel refer to Jay Ruby’s reevaluation of NANOOK OF THE NORTH (US 1922) as an early example of collaborative filmmaking (in this case, between the director Robert Flaherty and the Inuit) and to Dziga Vertov’s and the Kinoks’ work on the “kino-eye,” which calls for spectator participation and collective media movements. They go on to describe several predecessors of “collaborative, collective and participatory media movements,” ranging from the Workers Film and Photo League in the late 1920s to the Newsreel Collective of the 1960s (both in the US) to third cinema theories in 1960s Latin America and movements that engaged with postcolonial and postmodern thought in the 1970s and 80s, such as the Black Audio Film Collective in the UK. See Patricia R. Zimmermann and Helen De Michiel, Open Space New Media Documentary (New York: Routledge, 2018), xi–xix.

- 2See Bill Nichols, Introduction to Documentary (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010), 179.

- 3My use of the term is closely related to Annebella Pollen’s use of “mass photography” and “mass participation projects.” In Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life (London: I.B. Tauris, 2016), Pollen examines mass participation projects in more detail, focusing primarily on One Day for Life. This was a mass photography project (initiated by Search88, an organization that aims to raise money for cancer research and palliative care in the UK) that called on people to submit photographs taken on a specific date, namely August 14, 1987.

- 4Jon Dovey and Mandy Rose, “‘This Great Mapping of Ourselves’: New Documentary Forms Online,” in The Documentary Film Book, ed. Brian Winston (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 366.

- 5Jon Dovey and Mandy Rose, “‘This Great Mapping of Ourselves’: New Documentary Forms Online,” in The Documentary Film Book, ed. Brian Winston (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 366.

- 6Dovey and Rose understand camcorder culture as an evolving creative practice of the everyday that became a key factor in the rise of first-person documentaries, since the easily accessible, affordable, and highly mobile devices made it possible for a large number of amateurs to record and produce their own movies, opening up new forms of creative expression through video (see Dovey and Rose, “Mapping of Ourselves,” 367). Interestingly, camcorder culture is typified by a strongly inscribed presence of a subject behind the camera, declaring a sort of “I was here” impression. This became a popular practice in documentary, framed as “embodied presence,” and would eventually end up being inscribed into a vast amount of material used in mass participatory documentaries.

- 7William Uricchio emphasizes the importance of a historical perspective in order to better understand current and future developments of the documentary form (see William Uricchio, “Things to Come: The Possible Futures of Documentary … from a Historical Perspective,” in i-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary, ed. Judith Aston, Sandra Gaudenzi, and Mandy Rose (London and New York: Wallflower Press, 2017), 191–205. For more historical predecessors of amateur practices in participatory documentary, see Zimmermann and De Michiel, Open Space New Media Documentary, xi–xix.

- 8The analysis includes a variety of documentary films from between 2000 and 2010, including the work of Chinese filmmaker Wang Bing, Rithy Panh’s S-21, LA MACHINE DE MORT KHMÈRE ROUGE (F/CM 2003), and Thomas Heise’s MATERIAL (DE 2009). It excludes new online documentary forms; however, it might be worth bearing in mind the notion of film as an amateur medium for historiography and to think in more detail about how new online documentary forms are actually capable of depicting or – to use Simon Rothöhler’s term – of “reconstructing” history (see Simon Rothöhler, Amateur der Weltgeschichte: Historiographische Praktiken im Kino der Gegenwart (Zurich: diaphanes, 2011), 15.

- 9The whole journal is available online at http://www.alphavillejournal.com/.

- 10Siobhan O’Flynn talks about the concept of voice as a “rediscovered term” in connection to new documentary forms and gives an overview of the emergence of the term i-docs and contrasting terms such as Web-based documentary (webdoc) and transmedia documentary. She defines i-docs as “often designed as databases of content fragments, often on the Web, though not always, wherein unique interfaces structure the modes of interaction that allow audiences to play with documentary content. [...] the narrative or storyline is often designed as open, evolving, and processual, sometimes including audience created content” (see Siobhan O’Flynn, “Documentary’s Metaphoric Form: Webdoc, Interactive, Transmedia, Participatory and beyond,” Studies in Documentary Film 6, no. 2 (2012): 142). The definition has constantly evolved (as have new documentary forms themselves), and is moving away from a sole emphasis on interactivity toward a more inclusive concept.

- 11See Judith Aston and Stefano Odorico, “The Poetics and Politics of Polyphony: Towards a Research Method for Interactive Documentary,” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 15 (Summer 2018): 65.

- 12See Bill Nichols, “The Voice of Documentary,” in New Challenges for Documentary, ed. Alan Rosenthal and John Corner (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005).

- 13See Aston and Odorico, “Polyphony,” 73.

- 14See Patricia R. Zimmermann, “Thirty Speculations Toward a Polyphonic Model for New Media Documentary,” Alphaville 15 (Summer 2018): 12ff.

- 15See Zimmerman and De Michiel, Open Space New Media Documentary, 20ff.

- 16Ibid., 59ff.

- 17See Ed Gibbs, “Turning the Web into a Worldwide Wonder,” The Sydney Morning Herald, January 28, 2011, https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/turning-the-web-into-a-worl….

- 18See Dovey and Rose, “Mapping of Ourselves,” 370ff.

- 19Bakhtin in Aston and Odorico, “Polyphony,” 84.

- 20Mandy Rose (who led the VIDEO NATION project between 1994 and 2000) has herself repeatedly pointed out the connection to Mass Observation. She did so most recently in one of her articles on new documentary forms and co-creation as a strategy for activism (Mandy Rose, “Not Media about, but Media with: Co-Creation for Activism,” in i-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary, ed. Judith Aston, Sandra Gaudenzi, and Mandy Rose (London and New York: Wallflower Press, 2017), 49–65).

- 21Short videos (“vines”) taken by users and uploaded to the project page were inserted during the broadcast in order to emphasize and visualize the physical location of the people who were watching and “experiencing” the documentary at the time.

- 22“24h BERLIN,” https://www.zeroone.de/movies/24h-berlin/.

- 23See Zimmerman and De Michiel, Open Space New Media Documentary, 58–9.

- 24Britta Hartmann elaborates on the “pulse of the city,” explaining that it is frequently presented in real-time documentaries (Britta Hartmann, “Ethnografie und Archiv des Alltags: 24H BERLIN. EIN TAG IM LEBEN,” montage AV 21, no. 2 (2012): 168–70). In this respect, real-time documentaries appear to resemble the city symphony films of the 1920s and 30s.

- 25Ibid., 175.

- 26Volker Heise in Hartmann, “Archiv des Alltags,” 175.

- 27The project is still online, and users can still create their own stories at beta.18daysinegypt.com.

- 28The distinction between the two terms originates from Kate Nash and her work on participation in Web documentaries, in which she also talks about 18 DAYS IN EGYPT. Nash claims that, by giving users access to both voices, the project also aims to foster user engagement and activism (Kate Nash, “What Is Interactivity for? The Social Dimension of Web-Documentary Participation,” Continuum 28, no. 3 (2014): 383–95).

- 29The full database of collected material is available on the website at https://858.ma.

- 30See Zimmerman and De Michiel, Open Space New Media Documentary, 31.

- 31See Andreas Backhaus, “Die Geschichte ist ein Schlachtfeld,” Die Zeit, January 25, 2018, https://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2018-01/aegypten-kollektiv-mosireen….

- 32https://www.filmingrevolution.org

Aston, Judith, and Stefano Odorico. “The Poetics and Politics of Polyphony: Towards a Research Method for Interactive Documentary.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 15 (Summer 2018): 63–93.

Backhaus, Andreas. “Die Geschichte ist ein Schlachtfeld.” Die Zeit, January 25, 2018. https://www.zeit.de/politik/ausland/2018-01/aegypten-kollektiv-mosireen….

Bakhtin, Mikhail. The Dialogic Imagination. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Problems of Dostoevsky’s Poetics. Translated by Caryl Emerson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. Rabelais and His World. Translated by Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1984.

Bakhtin, Mikhail. “The Problem with Speech Genres.” In Speech Genres and Other Late Essays. Translated by Caryl Emerson and Michael Holquist, 60–102. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1986.

Bourriaud, Nicolas. Relational Aesthetics. Dijon: Les Presses du réel, 2002.

Burgess, Jean, and Joshua Green. YouTube: Online Video and Participatory Culture. Cambridge and Malden, MA: Polity, 2009.

Dovey, Jon, and Mandy Rose. “‘This Great Mapping of Ourselves’: New Documentary Forms Online.” In The Documentary Film Book, edited by Brian Winston, 366–75. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Eco, Umberto. The Open Work. Translated by Anna Cancogni. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1989.

Gibbs, Ed. “Turning the Web into a Worldwide Wonder.” The Sydney Morning Herald, January 28, 2011. https://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/movies/turning-the-web-into-a-worl….

Hartmann, Britta. “Ethnografie und Archiv des Alltags: 24H BERLIN – EIN TAG IM LEBEN.” montage AV. Zeitschrift für Theorie und Geschichte audiovisueller Kommunikation 21, no. 2 (2012): 162–80.

Nash, Kate. “What Is Interactivity for? The Social Dimension of Web-Documentary Participation.” Continuum 28, no. 3 (2014): 383–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/10304312.2014.893995.

Nichols, Bill. “The Voice of Documentary.” In New Challenges for Documentary, edited by Alan Rosenthal and John Corner, 17–33. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2005.

Nichols, Bill. Introduction to Documentary. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010.

O’Flynn, Siobhan. “Documentary’s Metaphoric Form: Webdoc, Interactive, Transmedia, Participatory and beyond.” Studies in Documentary Film 6, no. 2 (2012): 141–56. https://doi.org/10.1386/sdf.6.2.141_1.

Pollen, Annebella. Mass Photography: Collective Histories of Everyday Life. London: I.B. Tauris, 2016.

Rose, Mandy. “Not Media about, but Media with: Co-creation for Activism.” In i-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary, edited by Judith Aston, Sandra Gaudenzi, and Mandy Rose, 49–65. London and New York: Wallflower Press, 2017.

Uricchio, William. “Things to Come: The Possible Futures of Documentary … from a Historical Perspective.” In i-Docs: The Evolving Practices of Interactive Documentary, edited by Judith Aston, Sandra Gaudenzi, and Mandy Rose, 191–205. London and New York: Wallflower Press, 2017.

Zimmermann, Patricia R. “Thirty Speculations Toward a Polyphonic Model for New Media Documentary.” Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media 15 (Summer 2018): 9–15.

Zimmerman Patricia R., and Helen De Michiel. Open Space New Media Documentary: A Toolkit for Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge, 2018.