Film and History: Towards a General Ontology

Table of Contents

Mapping and Grounding Visual History

Nonfictional Film as Historical Source

Benjamin and Deleuze

Film and History: Towards a General Ontology

Analyzing the Familiar

Migrations of Media Aesthetics

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License.

Suggested Citation: Paalman, Floris: Film and History: Towards a General Ontology. In: Research in Film and History. Sources – Meaning – Experience (2021-01-28), No. 3, pp. 1–41. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15454.

Introduction: Cinema and Modern Life

From politics to tourism, and from space travel to mental health, cinema has affected many aspects of modern life. The use of propaganda has been widely known and studied. Films have successfully communicated all kinds of messages, both political and commercial. The most visible effects on audience behavior can probably be found in film-induced tourism,1 which has become a field of study in its own right, bringing together students of marketing and tourism. Film has triggered longings and provided models and references for daily life as well as lifetime ambitions, inspiring people to act accordingly. Many commentators have observed how Kubrick’s 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY (UK 1968) not only prepared the general audience for the moon flight in 1969,2 but also offered inspiration to scientists dealing with space engineering.3 In its wake, many more science-fiction blockbusters started to be produced in Hollywood, which had a similar effect on later generations. A comparable phenomenon could be observed in the USSR, where Tarkovski’s SOLARIS (USSR 1972) was also a hit among scientists.4 In addition, since the beginnings of cinema, cognitive scientists and psychologists have shown an interest in the medium. This has developed into a research area of its own, with handbooks presenting analyses of a myriad of films for students of psychology to serve as case studies and as reference material for therapy.5 Many other fields and practices affected by cinema could be mentioned here as well.

Cinema has become part and parcel of modernity, to such an extent that in ordinary discourse, it has even become a metaphor for capturing reality (fig. 1). However, how it came to be embedded in socio-cultural structures, and how it in turn has informed them, remains largely unclear. Reporting on the impact of 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY, Australian Cosmos journalist Lauren Fuge says: “But much of 2001’s influence is not concrete. It’s difficult to quantify how the film reshaped humanity’s thinking about its place in the cosmos and sparked a sense of wonder and inspiration — especially in future scientists”.6 While films can be analyzed through close reading, and revenues can be calculated, influence remains opaque. How can we acknowledge and understand the way cinema has contributed to the various fields of study mentioned above, and to major developments like industrialization, urbanization, and globalization? Or conversely, how have these fields and developments informed cinema, that is, as a medium to understand our place in the world and reflect upon our existence? A similar question is addressed by Barbara Klinger, who, in a plea for historical reception studies, reflects on what researchers might achieve: “Can they exhaust the factors involved in the relation between film and history, providing a comprehensive view of the rich contexts that once brought a film to life and gave it meaning for a variety of spectators?”7

History and film history could complement and enhance each other, but so far, there exists a gap in interaction between the two fields of study. While film has been appreciated as a unique medium to capture and reflect on reality, few historians use film, such as historical newsreels, as primary source material.8 Even less common is the use of historical fiction films, which express the values of a specific time, although important attempts have been made.9 Occasionally, historians engage with today’s period films through reconstruction and dramatization, alongside documentaries about history. Historian Marc Ferro, for example, has asked how films (both fiction and documentary films) frame history and society: from above, from below, from within (as participant) or from without. He has also asked what history is being told: an officially sanctioned history or that of a counter-institution, memories of people involved, or an autonomous analysis? These two axes, of how and what, constitute “Ferro’s Grid”.10 While some filmmakers use similar methods as historians, others may “encourage a form of historiographic practice that is more reflexive, experimental and critically aware of its own auspices”.11 But many scholars are still hesitant to engage with audiovisual writing of history, notwithstanding the impact films may have had by creating images in the minds of both the general public and historians, and by affecting discourse.12

Film historians, in turn, have worked on the development of cinema, regarding films as works of art or realistic representations of the world, and studied them in terms of style, cinematic language, and discourse. Since the 1980s, the revisionist approaches of new film history, media archaeology, and new cinema history, have turned the attention from the text towards the socio-economic context of production and consumption of films, their material and technological features.13 In this way, film has been studied as an artefact existing in the world. The focus, however, has still been inward, on film itself, rather than on its social functions.

The purpose of this article is to construct a historiographical framework and to set a research agenda that can give both film historians and historians a finer apprehension of the relations between film and history. In an outline, relevant concepts and approaches will be related to each other and combined, and research directions will be indicated. Inevitably, relevant literature and concepts will often be mentioned, where further exploration might be welcome. Various implications of the framework developed here, which is intended as a general ontology of cinema from a historical perspective, will need to be elaborated further; this article is an invitation to the reader to reflect upon my suggestions and advance them.

World Cinema History

Notwithstanding empiricist and materialist revisionism, many historically oriented film scholars still rely on conventional concepts such as realism, national cinema, auteur, and film as art, with a focus on style, aesthetics, and representation. Their studies have largely been informed by hermeneutic film theory and cultural analysis. This can be observed in different fields of film studies, including world cinema. However, most authors concerned with world cinema also view films explicitly in the light of cultural context and political conditions.14 This is true for an increasing number of historically oriented publications on world cinema.15 While some are fairly conventional in historiographic terms, there are also more daring ones, through which one can observe a distinct historiographical framework emerging in this field, which has the potential to bridge the gap between history and film history.16 What these publications have in common is a concern with textual issues of representation and politics, alongside the socio-economic conditions of film production and consumption. This is partly informed by new film history, although methodologies from the social sciences have been applied also.17 I will briefly describe how the approach of world cinema history has developed, and highlight the propositions of some key publications, in order to describe the features of this historiographical method.

In 1930, British filmmaker and critic Paul Rotha wrote the book The Film Till Now, which was subject to several subsequent revisions. The 1948 edition included a survey of contemporary films from around the world, compiled with the help of Richard Griffith (assistant director of the MoMA film library in New York). In 1960, the book’s survey of contemporary cinema from different countries was updated and the title extended — The Film Till Now: A Survey of World Cinema. Still, the book was mainly about American and European cinema, a fact which the authors acknowledge,18 and one which reveals how difficult it was for them to gain an idea of what was happening elsewhere. Things would soon change after 1960,19 spurred by the emergence of film festivals screening films from around the world, such as the Documentary film week in Leipzig.20 Beyond the exchange of contemporary films, the next challenge was to outline a historical overview of films from around the world.

In 1973, The History of World Cinema was published, written by British film critic David Robinson. The work is mainly focused on artistic achievements and economic factors, describing the developments in film throughout various continents. Robinson observes how, in the 1930s and 1940s, Hollywood pursued a policy of conquest and annexation at the expense of film industries in other countries, and comes to the conclusion that, in terms of art, it was a period of retrogression and reactionary virtues. On the whole, the book is an attempt to give a comprehensive historical overview of cinema rather than develop an idea of film’s diversity and map different traditions. Or, as a reviewer noted: “He deals with production from a cosmopolitan point of view but does center his attention on western Europe and, in particular, on the U.S.A.”.21 Moreover, it is a chronological narrative that still exemplifies the old way of writing film history. Robinson’s achievement, however, lay in writing a history that also included other areas of the world, discovering hitherto unknown films from the early days. This was also his primary interest, and so he became the director (1997–2015)22 of the Giornate del Cinema Muto silent film festival in Pordenone, which has fuelled the development of new film history and media archaeology.23 Robinson’s book is therefore part of a historiographical transition.

The notion of world cinema history gained in relevance with the book The Oxford History of World Cinema (1997), edited by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith.24 It was a daring attempt by 81 authors to write an 800-page all-inclusive history of cinema, or, as the book cover says: “The definitive history of cinema worldwide.” Among its contributors are many authors associated with new film history and the then emerging approaches of media archaeology and (new) cinema history. However, the fact that most contributors were from the USA and UK has defined the book’s structure and aspects receiving the most attention. The book is divided into three parts of about twenty-five chapters each. The first part (Silent Cinema 1895–1930) deals almost exclusively with the emergence of cinema in Europe and America and is largely focused on production. Under the heading of ‘national cinemas,’ only one final chapter is dedicated to Japanese cinema. The second part (Sound Cinema 1930–1960) pays special attention to Hollywood’s studio system, (American) genre cinema and, once more, the national cinemas of various European countries as well as Japan, with additional chapters on the cinemas of China, India, Australia and one chapter on cinemas in Latin America. The last part (The Modern Cinema 1960–1995) addresses the impact of television on Hollywood, American movies (with subjects as varied as black presence or blockbusters), art film and the avant-garde, and national cinemas, now called ‘Cinemas of the World,’ which basically subsumes everything that is not American. It encompasses European cinemas (those of France, Italy, Spain, UK, Germany, Eastern Europe, Russia, and ex-Soviet Republics), and the cinemas of the Arab World, Turkey, Sub-Saharan Africa, Iran, India, China, Hong Kong, Taiwan, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and Latin America. While a merit of the book lies in extending the scope, it also raises the question what the histories of various film cultures were like before 1960. Moreover, one may ask why certain cinemas were not discussed in separate chapters, for example that of Egypt, or the cinemas of Latin America, which became globally prominent and influential in this period. Overall, the book is largely structured along the lines of ‘old film history,’ to which it provides supplements.

In the meantime, the term ‘world music’ had been coined in the 1960s by the American ethnomusicologist Robert E. Brown.25 His world music program at Wesleyan University encompassed Western art music and jazz, music of India, Java, Japan, and Ghana, and Native American traditions. This selection was practically motivated, but the term world music “was meant to be inclusive, not just as a label for non-Western traditions”.26 In the 1980s and 1990s, however, it became a marketing category for non-Western music, including folk, ethnic, indigenous, and traditional music, or popular music inspired by this. But how can all of these belong to one genre? A classification such as this proves especially problematic for film: what are the cinematic equivalents to folk and indigenous music traditions that go back for generations? Moreover, where would commercial cinema fit in?27 James Chapman's book Cinemas of the World: Film and Society from 1895 to the Present (2003) presents a discussion of film history more akin to Brown’s definition of world music. Although the title still suggests a conventional, linear perspective, it deliberately uses the plural — cinemas — and the introduction speaks of ‘historical perspectives’ rather than ‘history,’ making it clear that Chapman wished to steer away from the idea of presenting one monolithic history. He describes how film production throughout the world has raised various theoretical questions. “The most significant of these is whether any general model can adequately account for the many different filmmaking practices, genres, styles and traditions that have arisen in the global context”.28 While it is difficult, even problematic, to bring all cinemas of the world under a general label, Chapman finds the solution in what he calls the ‘comparative approach.’ It takes diversity into account and offers a historiographical method of looking for patterns across places and times.

World Cinema Typologies

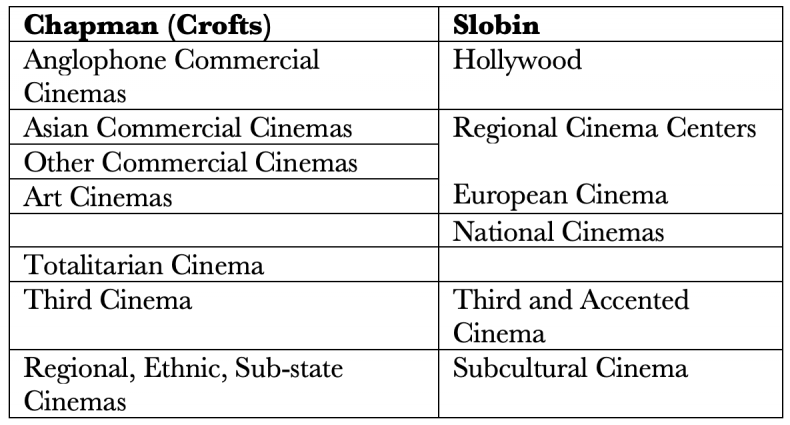

Comparisons need to be drawn on a common basis. Chapman relies on Stephen Crofts’ article Reconceptualising National Cinema/s (1993), in particular his typology of the seven major types of cinema.29 Chapman defines Art Cinemas as one category, next to Asian, Anglophone, and Other Commercial Cinemas. Besides, he also identifies Totalitarian Cinemas, Third Cinema, and Regional, Ethnic, and Sub-state Cinemas. However, other typologies can be defined, as Chapman acknowledges, which is indeed done by Mark Slobin (see fig. 2) in Global Soundtracks: Worlds of Film Music (2008). Slobin is an ethnomusicologist, and while he refers to neither Chapman nor Crofts, he too emphasizes the need for comparison. He says that case studies bring you right into the action, “But we also want to try out comparative approaches, which have been singularly lacking in film studies”.30 Slobin extensively discusses Hollywood before drawing his typology, where he does not list Hollywood again, but it should effectively be seen as his first category. He then distinguishes Subcultural Cinema, European Cinema (both commercial and art cinema), Regional Cinema Centres (i.e. supranational, in Mexico, Brazil, Egypt, India, USSR, South Korea), National Cinemas (e.g. Asian national cinemas, European national cinemas, and outspoken cinema cultures elsewhere, such as in Nigeria), and Third and Accented Cinema (including several cinemas from Latin America).

While Chapman sees Art Cinemas as a separate category, for Slobin it is covered by European cinema, which also includes commercial cinema. And while Chapman distinguishes three kinds of commercial cinema, Slobin defines it as Hollywood and Regional Centres. Chapman avoids the concept of national cinema, although it is still prominent throughout his book. Slobin retains it as a distinct category describing cinemas that cater to a specific nation, without further distribution, as distinct from his Regional Centres category.

Chapman also distinguishes Totalitarian Cinemas, due to his emphasis on politics. Interestingly, he classifies all Soviet cinema as Totalitarian, whereas Slobin also recognizes the different subcultural cinemas that were present in the Soviet Union. For both authors, the political dimension is present in Third Cinema (which rejects both Hollywood and auteur cinema); Slobin, however, includes Accented Cinema in this category. For Chapman, Accented Cinema is part of Regional, Ethnic, and Sub-state Cinemas, but for Slobin, Accented Cinema is transnational, like Third Cinema. The problem with any typology is that in reality, all kinds of cross-connections and combinations exist. Slobin acknowledges this when he says, “Any category offered here can be contested and reconsidered”.31 To complicate the matter, one could also compile different typologies for different historical periods. Any attempt to map their varying shifts would be a major historiographic challenge, but could be explored using digital means.

In 2007, Chapman co-authored the book The New Film History: Sources, Methods, Approaches. As a new film historian, Chapman is interested in context, and thus analyzes modes of production and distribution. However, he also allows for textual analysis in order to map the relationship between film content and production conditions. While this may still align with new film history, as the conditions under which a film was produced may explain certain textual features, his idea of world cinema history suggests a combined usage of textual and contextual analysis, which corresponds to the idea of ‘World Cinema as methodology.’32 A crucial feature is what I would call the ‘text-context continuum,’ which is a major potential of world cinema history. In this respect, however, different analytical approaches are currently being followed within research.

On the one hand, there are approaches based on aesthetics.33 One publication which is characteristic of this approach is Global Art Cinema: New Theories and Histories, edited by Galt and Schoonover, which adheres to the paradigm of art, auteur, and new waves, historically associated with European cinema, but applies it globally. Within this approach, cinema is considered above all as art which can then be related to politics as authorship is understood to inherently imply political agency.34 Rather than style being transmitted from the centre to the periphery, topics that are usually considered local are compared internationally.35 Since filmmakers around the world engage with and propel certain discourses by providing ideas, visions, and models that have political impact, other scholars are therefore especially concerned with politics.36 This is most explicitly exemplified by the book Third Cinema, World Cinema and Marxism, edited by Kristensen and Mazierska. Its retrospective section is not simply intended to serve historiography but is meant to inform today’s political agenda. It criticizes the concept of World Cinema, being based on transnationalism and cultural diversity, as ideas that serve neo-liberalism and global consumerism.37 Kristensen and Mazierska take a Marxist position and align themselves with Third Cinema. Moving away from transnationalism, they focus on localized praxis within national contexts. For the authors, Third Cinema, with its aesthetic openness and imperfection, provides a method through which to understand how people are entangled in specific historical circumstances, and how they can act within them.38

While Chapman and Slobin draw up typologies for the purpose of historical comparison, authors like Galt and Schoonover have refined this endeavour for Art Cinemas (as a category corresponding to Chapman’s typology), and Kristensen and Mazierska have done the same for Third Cinema (corresponding to both typologies). Meanwhile, it would be plausible if Kristensen and Mazierska had objected to the use of such typologies, as they conceal power relations by simply rendering different types of cinema as mere options to be consumed (or studied).

On the other hand, typologies facilitate a mapping of cinemas, and geographical features come to be recurrently addressed in regard to World Cinema.39 Mapping the geographical features of film texts, as well as aspects of production and exhibition, enables distant readings, in order to recognize patterns in certain types of films and film practices across different countries. At the same time, mapping can be used to analyse localized praxis in order to explain variations and specificities of particular films. Film content relates to an environment: in a direct way for what it shows, or indirectly for how it comes about. All content is affected by particular socio-economic conditions and connections between people, locations, and objects, so the mapping method can create a common ground within world cinema history and bridge the different strategies of reading the relation between text and context.

An Active Force: Third Cinema

The power of cinema is to be found in the way it presents visions of the world, or an imaginary world, and how it acts in the world. This applies to all types of cinema, but historiographically it can best be examined through Third Cinema, which was most explicitly aimed at changing social conditions. This movement, which proposed a third path, rejecting both Hollywood and auteur cinema, emerged in the 1960s. It was spurred on by Cuban cinema, such as the newsreel series NOTICIERO ICAIC LATINOAMERICANO (Cuba 1960–1990), supervised by Santiago Álvarez, and the work of Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in Argentina, especially their film LA HORA DE LOS HORNOS / THE HOUR OF THE FURNACES (1968) and their written manifestos "Towards a Third Cinema" (1969) and "Militant Cinema" (1971). These two texts, next to multiple other manifestos written within the context of Third Cinema and other movements, have also been included in the anthology Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures by Scott MacKenzie. This anthology is based on the proposition that “the act of calling into being a new form of cinema [did not only change] moving images but the world itself”,40 which in turn relies on the premise that “…one cannot take moving images to be separate from the world or to be simply a mirror or reflection of the real. Instead, one must see moving images as a constitutive part of the real: as images change, so does the rest of the world”.41 MacKenzie understands both film and film manifestos according to the maxim of “aesthetics as action”.42 In Third Cinema, both films and manifestos are meant to intervene in political discourse, and function as tools for social change. Rather than regarding film as an object in itself, and with an aesthetic quality of its own, this process orientation provides a historiographic perspective that allows us to understand cinema’s place in the world.

Forming part of politics, films have thus stood side-by-side with other media, such as magazines, posters, banners, flyers, music records, radio and television broadcasts, live performances, concerts and plays, as well as demonstrations and strikes. As such, Third Cinema is a poignant example of cross-media practices. Ironically, commercial practices have increasingly applied similar strategies, known in marketing as the ‘media mix.’ In fact, activist films and commercials both serve socio-economic purposes. In the end, this applies to all films and media productions, as they all serve their own unique social and financial (hence political) interests.

Characteristic for Third Cinema, however, are the close connections between production, distribution, exhibition, and consumption. Teshome Gabriel, a prominent theorist of Third Cinema, especially in the context of the Third World, has argued that film production passes through three phases there.43 The first is ‘the unqualified assimilation,’ in which the industry identifies with Hollywood and copies its themes and entertainment function; the second is ‘the remembrance phase,’ which for the industry means “Indigenisation and control of talents, production, exhibition and distribution,” and the “movement for a social institution of cinema in the Third World,” propelling the theme of “Return of the exile to the Third World’s source of strength, i.e., culture and history”.44 The third is ‘the combative phase,’ characterized by “Film-making as a public service institution” in which the film industry is “managed, operated and run for and by the people,” focused on the theme of “Lives and struggles of Third World peoples”.45 Gabriel observed that, in the 1980s, most Third World cinemas were in the second phase. Irrespective of the explanatory value of this Marxist view, it is a historiographical model that itself became part of a historical process, as it has inspired filmmakers. Important here is the need to control the means of production, distribution, and exhibition.

Within a short period, around 1970, a dense international network was established,46 that included countless small-scale local venues where films were shown, among them community centres, schools, and fair-trade shops. Film screenings weren’t just shows. In the manifesto "Towards a Third Cinema," film screenings were conceptualized by Solanas and Getino as ‘film acts’:

[E]ach projection of a film act presupposes a different setting, since the space where it takes place, the materials that go to make it up (actors-participants), and the historic time in which it takes place are never the same. This means that the result of each projection act will depend on those who organise it, on those who participate in it, and on the time and place; the possibility of introducing variations, additions, and changes is unlimited. The screening of a film act will always express in one way or another the historical situation in which it takes place…47

Film screenings were often accompanied by speeches, discussions, and actions such as demonstrations, petition signings, collection donations for various organizations, or the planning of such events in the future.48 A direct link was established between the content of the films, the conditions to which they referred, and the situation of the viewers, which usually necessitated some form of ‘local appropriation.’ As has been observed in the case of the militant film collective Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms in Amsterdam (1966–1986), this was carried out through (live) translation, modification of films, combined screenings of local and foreign films, and through own productions elaborating on the themes of the other films.49 This made film acts unique events, with historical contextuality being at the core of the Third Cinema project.50 Historical specificity and local praxis have been primary features of Third Cinema throughout its history.

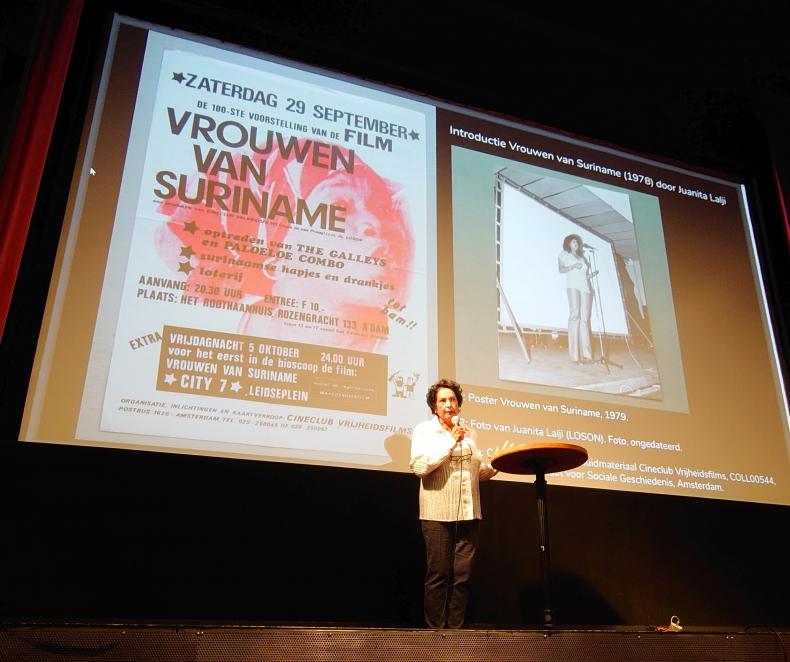

By extension, such features may also inform today’s archival practice related to Third Cinema, which can also be exemplified by the case of the Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms collection preserved by the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam. As part of a project to activate this collection, screenings have been organized to inform people about the existence and the relevance of the films, and to involve communities. This has happened, for example, with the documentary VROUWEN VAN SURINAME / WOMEN OF SURINAME (At van Praag, 1978), about the history of Suriname and its situation since its independence, which is represented by the lives of five women. After decades, the film was shown again, by means of a deteriorated 16mm film copy, at Kriterion cinema in Amsterdam (2020). The programmers Luna Hupperetz and Luisa González invited Juanita Lalji to introduce the film, who did it more than a hundred times about forty years ago (fig. 3). After the screening, a forum discussion took place between people who had been involved with the production of the film. They commented on its ideas and the political conditions now and then, both in Suriname and the Netherlands, regarding (neo-)colonialism and racism, to which the audience responded as well. It became clear that the issues addressed by this film are still actual today. There is a strong interest in the film, also among younger generations within the Surinamese community, to learn about history and activist strategies from the past. As a result, plans have been made to restore and digitize the film and to investigate related archival footage, to be used on social media platforms, in order to raise historical awareness and to foster a dialogue between Dutch and Surinamese people.

Third Cinema remained a prominent force until the mid-1980s, when it started to be re-evaluated.51 Partly based on Teshome Gabriel’s theory, Third Cinema came increasingly to be understood as Third World Cinema and started to incorporate auteur cinema too. Its militant nature diminished, and in the 1990s, many thought that Third Cinema had ended.52 However, an increasing number of filmmakers, programmers, critics, and scholars today see a continuation.53 Many filmmakers from the early years continued to address social issues and postcolonial conditions, like Fernando Solanas in Argentina and Ousmane Sembène in Senegal. Others turned to a more introspective and retrospective approach later on in their careers, often using a poetic style, but still addressing political issues that persisted, for example, the Chilean filmmaker Patricio Guzmán in his CORDILLERA OF DREAMS (Chile/France 2019).

A generation of filmmakers which emerged around the year 2000 have also been associated with Third Cinema. One example is Apichatpong Weerasethakul in Thailand and his production company Kick the Machine.54 While his work is also regarded as auteur cinema from the Third World, Third Cinema features are seen especially in his “consistent thematic concern with border forms and subject,” relating to both physical and symbolic boundaries, by which he reconsiders the relationship between humans and nature, “endorsing an aesthetic ideal of submitting to the senses”.55 Weerasethakul developed this approach based on his own experience of the rapidly changing rural environment he grew up in.56 At the same time, with his “mergers of several notable oppositions,” Weerasethakul “eludes the grasp of simple classification”.57 This is typical of filmmakers who draw upon the legacy of Third Cinema, while simultaneously exploring new paths. Other examples include the Philippine filmmaker Lava Diaz, for his slow cinema, and Khavn De La Cruz for his aesthetics of ‘imperfection’.58 Their work correlates with the idea of an ‘imperfect cinema’ advocated by Cuban filmmaker Julio Espinosa, who in 1969 was already imagining a future in which film technology would be accessible to everyone. It also draws a direct link to today’s activist media practices.59

Apart from Third Cinema aesthetics, while always related to socio-economic conditions and available technologies, continuities have been articulated especially in terms of political causes with regard to queer, feminist, postcolonial, migrant, poor, and ecocinema.60 Some young filmmakers today, such as Nadir Bouhmouch, director of AMUSSU (2019), a documentary about residents from a Moroccan village resisting a silver mine, explicitly see their work as Third Cinema, and favour collectivist and participatory methods of production instead of becoming absorbed in auteurism.61 Bouhmouch, moreover, has also applied the idea of ‘film act’ in a contemporary way using the spotlights of a major film festival to make a political statement. During the premiere of AMUSSU at Hot Docs in Toronto, May 2019, he protested against the imprisonment of Hirak Rif activists in Morocco, which he subsequently communicated through Twitter as well (fig. 4).

These examples show that Third Cinema has served as a reference for filmmakers and scholars for more than half a century. All films within Third Cinema, past and present, show a conscious political positioning, usually in combination with an aesthetic openness. However, the films also display significant variations with regard to their subjects, geographic and cultural orientation, affiliations, modes of address, styles, and the balance between aesthetics and politics. “Third Cinema cannot be reduced to a specific set of films, to certain modes of production or distribution, to the audiences it targets nor to its contemporaneous modes of reception and not even to the ideological programme it follows”.62 In fact, the diversity of cases that scholars have discussed in the context of Third Cinema cover all the possibilities of ‘Ferro’s grid,’63 from officially sanctioned views expressed ‘from above’ in the case of Cuban cinema, to Guzman’s memoires and scrutiny of his own place in history ‘from within,’ alongside views ‘from below’ that allow for a sensory engagement, like in the case of Weerasethakul. Due to this diversity, Third Cinema would be appropriate for an analysis of how cinema frames history, while its transnational circulation combined with local praxis, embedded in specific historical conditions, also illustrates the position, function, and place of cinema in history.

Ontology

Film studies have long been dominated by the ideas of realism and photographic ontology, which have been considered quintessential for film. Photographic ontology has been discussed with regard to its relation with reality, but also for the concurrent problem of how it allows film to be art. In his book Film History as Media Archaeology (2016), Thomas Elsaesser still refers to the idea of ontology as having become subject to discussion since the advent of digital cinema. Moving one step further, he has begun to redefine cinema’s ontology in his book European Cinema and Continental Philosophy (2019). He therefore reviews the work of influential philosophers who have written on film.

Cavell, Deleuze and Nancy do not focus on aesthetics, but are very much more concerned with a new ontology that cinema has brought into the Western world, that is, a new taxonomy of what exists and what does not, what is alive and what is not, and have thus provided philosophy with an enigma and challenge, rather than using cinema merely for illustration of reality or the representation of what exists.64

Cinema has thus been conceptualized as a ‘reality that thinks.’ Instead of looking into the meaning of a film or how it represents reality, Elsaesser stresses its existence and function, how its images affect viewers, how they constitute realities in their own right, and how they classify the world.65

But besides the ontology of cinema, Elsaesser, in passing, also regards cinema as an ontology, “in the sense of instantiating the groundless ground of our being — and reconciling us to it (renewing our ‘belief in the world’)”.66 Cinema serves as an ontology to ground our belief in the world, and Elsaesser relates various political ideals to it.67 Articulating such a position and role of cinema in the world seems to be the ultimate purpose of Elsaesser’s book. This is in fact the answer to the fundamental question he raises: what is cinema good for?68 Yet, this question is far-reaching, and there are many ways in which it can be reformulated and answered. Elsaesser enumerates several implicit and explicit answers offered by various people over time, such as the idea that cinema is intended as a means of preserving an imprint of life (to defeat death), as a mirror, a window on the world, a disembodied eye that sees all, a storytelling medium to make sense of the world, a means of acting from a distance, of mastering life through simulation and play, as well as a technological training of the senses as a disciplining tool of modernity. Elsaesser himself sees cinema primarily as a humanist hope, indebted to technology, which is therefore an inherent part of its ontology. These purposes are functions that cinema has performed in society, but Elsaesser does not elaborate on them in further detail. He merely provides the outline for a new ontology, which for him suffices in order to discuss the way in which film thinks, and how film can be seen as a thought experiment. While in that light he resolutely moves away from meaning and representation, besides various other classic concepts from film studies, such as ‘author’, ‘genre’, and ‘realism,’ he also recognizes how certain categories “are relevant to the audience as human beings, where films might still be seen as coded texts and symbolic actions, but where cinema is also an event and an experience of the world, and of us in the world…”.69 Therefore it seems crucial to critically retain some of film studies’ classical preoccupations, especially regarding textual analysis.

A theory needs to be developed which understands film as both text and technological artefact, and explains its position and functions in society, how these functions are performed, and their actual implications as part of the ‘text-context continuum.’ I would therefore propose a ‘general ontology of cinema’ in the context of modern life. To that end, it is first important to define the denominators of this proposal. Cinema is understood here as: the world of film, as material artefact, aesthetic form, textual content, and as a form of thinking as well as its production, distribution, exhibition, consumption, archiving, and the discourse surrounding it. Ontology is understood here as: the existence of an entity with particular features and properties and the conditions of its existence, including its relations to its environment. The general ontology of cinema could then be defined as: the existence and manifestation of cinema in the world, and its relationship to the world.

The proposed ontology can be elaborated on through the lens of ecocinema. Of special relevance here is Adrian Ivakhiv’s conceptualisation of the film-earth relationship, not only in terms of cinematic representation, but also in terms of cinema’s position in the world. Ivakhiv distinguishes anthropomorphic, geomorphic, and biomorphic registers of cinema and links them to three corresponding ecologies: social, material, and mental.70 I take the anthropomorphic register to encompass the ‘film text’ presenting the human subject and social world; within the geomorphic register one can recognize cinema’s dispositif, but extended, with the film form being related to material factors and geographical positioning; the biomorphic register concerns the production, mediation, and perception of lifelike cinematic appearances that become affects and mental (or cognitive) constructs. Each register enables interaction with the world, but Ivakhiv stresses the film experience, which sets something in motion.71 This presents an agenda for new cinema history, concerning the consumption of films, seeing what happens after viewing, as part of cinema’s social operation. Besides synchronic relations, new cinema history can map long term, diachronic relations.

In order to understand the existence of an entity, one must first pose the inevitable question as to how it came into existence, and why. This is a problem of origins. Given that the reasons why something comes into existence are conditional, and that those conditions change over time, the question is also how the phenomenon fulfils its functions, and how those functions develop vis-à-vis the environment. These dimensions mean that ontology is inherently historical and of a diachronic nature. Since the reason why something emerges is external to the thing itself, ontology also points to the synchronic relations between the phenomenon and the world in which it exists. In this case, what is the system cinema is part of, what position does it occupy, what functions does it fulfil in it, and how? Who are the stakeholders? How does the body of cinema establish relations with other bodies, both human and non-human?

As a medium, cinema is both material and symbolic, which creates a double ontology. As a material artefact is has economic value, and its production and organization make cinema an industry with its own logic and specific technological, financial, and labor assets. Cinema already became a global industry very early on in its history. Such factors affect films’ images, as for example in the use of stand-in locations, or the different endings of films for different markets. In the last decade or so, the extensive networks of the film industry have attracted more substantial scholarly attention across the fields of economics, marketing, geography, and film studies. Film’s symbolic properties and their impact, although acknowledged from the beginning of cinema, are still hard to determine beyond their formal appearances. Much of film theory has been concerned with the question of meaning, but the (historical) interconnection with the industrial logic of cinema still requires further research. The symbolic dimension, however, may also lead to another ontological agenda.

An ontology of a phenomenon that actively involves human input entails imagination and belief, and a self-reflexive dimension that complicates the ontology. This is especially the case with self-reflexive cinema addressing the human condition. A general ontology of cinema, of an inherently historical nature, will therefore also map properties like imagination, belief, and self-reflexivity. They are especially hard to define when it comes to inspiration and motivation and how sensations of being in the world are captured, expressed, transferred, and subsequently appropriated, applied and transformed by filmmakers and spectators respectively.

Especially difficult from this perspective is the problem of ‘emergence,’ which refers to the properties of an entity that are absent in its constituent parts, but emerge in the larger body. It can already be observed in the most elementary level of cinema: motion emerges out of a series of still images. Emergence also takes place when distinct ideas arise from various impressions, individually and collectively. In a less obvious way, emergence also occurs when all the cinematic images that a person has seen during their life combine to create a Cinematic Imaginary, which then multiplies throughout an entire society. The force of emergence is little understood, but it is key to understanding the ontological problem as to how something universal relates to something particular, or the way in which cinema as a whole relates to a certain film, and how, in turn, one film can inform us about cinema as a whole. This is exemplified by the problem of cinematic language; is it possible to learn cinematic language by studying one film? Or, if ideology is considered, can one film change collectively held ideas? The proposed ontology should therefore also take into account the different scales of cinema, from a single film to the output of a film industry, and from film festivals or archives to world cinema history.

A film presents a particular world view. A historical review of a large corpus of films is inevitably an abstraction and thus presents its own world view. Such a review is informed by the films under consideration, but in terms of vision or conceptual depth, it is not necessarily more profound, comprehensive or sophisticated than any of those films individually. Similarly, an archival collection or film festival selection may be presented by stressing common denominators or shared themes, but the world view of each film might be more thorough than the view that stems from the entire body. This also translates into analytical approaches; methodologically speaking, studies based on pattern recognition in a large corpus may stand on an equal footing to case studies or close readings. As long as the mapping of patterns, just like conducting case studies, transcends description and employs rigorous analysis to inform argumentation and conceptualization, both methods will be valuable. In any case, both are needed in order to conceptualize a general ontology that moves between the scales represented by the two methods.

When filmmakers are given a voice as partners in historiographical discussions — when we allow their films to speak back, just like archives at the other end of the historical spectrum, epistemology extends to create a self-reflexive (film) history. Because when individuals and institutions, with their daily struggles to find resources to carry out their plans, are brought into the discussion, scholars will similarly have to reflect upon their own incentives and the aims of carrying out historical research. Why, after all, are certain historical subjects of interest today? How are historical issues addressed in order to serve today’s purposes? This ‘research ontology’ and its agenda points to the intertwined functions performed by filmmakers, historians, and archivists, among others, in order to understand how their collective work facilitates history to be written.

Total History

While world cinema history initially referred to the entire history of cinema, after 2000 it steered away from the idea of a monolithic history based on a western perspective, allowing instead for multiple histories to be told. World cinema history written today follows the text-context continuum, in which the representation and meaning of a film text is brought into connection with social institutions and social developments. One would therefore frequently expect to encounter references to the historian Fernand Braudel and his concept of ‘total history’ within film studies. Total history is a historical viewpoint that integrates the worlds of geography and economics alongside social institutions and political actions. However, Braudel’s name is hardly ever encountered within the field of film historical studies. This is not just because he wrote about periods before the advent of cinema, but above all due to the gap that exists between history and film history. One exception, however, is Barbara Klinger, who has made extensive use of his ideas in the context of historical film reception studies.

In a total history, the analyst studies complex interactive environments or levels of society involved in the production of a particular event, effecting a historical synthesis, an integrated picture of synchronic as well as diachronic change. In Foucauldian terms, total history appears as the general episteme of an archaeological stratum which would include the system of relations between heterogeneous forms of discourse in that stratum. A Marxist gloss defines total history as a 'dialectical history of ceaseless interaction among the political, economic, and cultural, as a result of which the whole society is ultimately transformed.' Whatever the specific permutation, the grand view behind a histoire totale has several valuable functions for film history. … [P]ursuing this idea in the context of film studies provides the occasion for imagining what a cinematic version of histoire totale might comprise, creating a panoramic view of the contexts most associated with cinema's social and historical conditions of existence, and returning us to the question of what exactly is at stake in materialist approaches to textuality.72

Klinger’s endeavour with regard to historical reception studies might serve to bring back the question of meaning that has disappeared from the agenda of new cinema history, which has disregarded textuality in favor of cinemagoing as social fact. Klinger paves the way here for a historiographical approach that links content to conditions.

For too long, film historical research has not been a cutting-edge theoretical endeavour. This issue was raised by Jane Gaines, who, with reference to Hayden White, focused on the epistemological position of the film historian, who is effectively producing metahistory.73 This position can be taken as a warning against viewing ‘total history’ as the “definitive history of cinema worldwide,” which in 1997 was still the logline of The Oxford History of World Cinema.74 However, in 1997 Klinger also warned against such a view, arguing that total history is merely a utopian aim. Braudel summarizes it as follows: “if not to see everything, at least to locate everything”.75 Gaines, however, refers to the perspective of the researcher, pointing out that an overarching utopian (i.e., singular) view doesn’t hold water either, since the writing of history is always a directional process rooted in the episteme of its own era. With reference to historian Keith Jenkins, Gaines stresses that history is always a form of “imagined re-existence.” However, what remains relevant in Braudel’s total history is the integral approach, connecting different fields. Braudel, explaining the title of his book Civilization and Capitalism, says: “For civilizations do indeed create bonds, that is to say an order, bringing together thousands of cultural possessions effectively different from, and at first sight even foreign to, each other — goods that range from those of the spirit and the intellect to the tools and objects of everyday life”.76

Although much film theory has been neglected by film historians, the concept of the auteur has never fully disappeared from film history. This is a further complication with regard to using Braudel in film historiography, as he granted little agency to individuals.

The strength as well as the weakness in Braudel’s concept [of total history] is that it minimises the power of individuals and groups in shaping their own destinies. It errs in exaggerating the importance of external physical forces, inherited biological characteristics and impersonal social and economic institutions. Movements and trends are made to seem beyond the control of living men and women.77

A challenge within the creation of a total history of cinema lies in overcoming the tension between the collective and the individual, or the universal and the particular. The solution might be found in the concept of ‘the everyday,’ which Braudel describes in great detail alongside power structures and major historical events. It is the everyday that cinema has recorded and directed in great detail since its beginning.78

Braudel’s ‘everyday’ was part of the shortest historical term he distinguished. He identified three kinds of duration: the longue durée of environmental time, characterized by persistent structures in which things change very slowly, the medium time of economies, societies, and cultures (or the history of institutions conceptualized as conjunctures), and the short time of discrete events (histoire événementielle).79 As cinema is a relatively new star on the historical horizon, the first duration appears to be of no meaning to film historians. However, in The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II (originally published in 1949),80 Braudel shows that this time frame provides the foundation upon which every other development unfolds; “the almost timeless realities of terrain, climate, agriculture, cities, trade, transport and population were perceived as the most substantial and persistent facts of Mediterranean history”.81

The environment, with its longue durée, provides the foundation for a general ontology of cinema. Klinger’s emphasis on cinema’s social and historical conditions of existence substantiates this ontology. Its further elaboration can build upon media archaeology. Informed by Foucault’s ‘archaeology,’ Elsaesser explains that cinema has no single origin and no pre-ordained goals.82 Instead, cinema has emerged along with discursive formations and historical epistemes. Similarly inspired by Foucault has been “the emphasis on institutions, customs, habits, and unwritten rules as historical agents, invariably expressing relations of power”.83 Conditions of existence thus call for analyses of (long lasting) power relations, purposes, and interests. In order to research the conditions of existence of cinema, one needs to consider its function within a socio-cultural system.

Environments of Cinema

The paradigm of structural-functionalism within the social sciences in the 1940s and 1950s contended that social activities and artefacts are interrelated and fulfil functions that can maintain a system. American sociologist Charles Wright applied these ideas to media in his book Mass Communication: A Sociological Perspective (1959) and identified four main functions of the media: 1) surveillance of the environment, 2) correlation of the parts of society in responding to the environment, 3) transmission of social heritage from one generation to the next, 4) entertainment.84 It should be noted that these functions are primarily concerned with organization and stability. Functions more attuned to change and development would relate to cognition, such as interpretation, imagination, and experimentation, where film has important contributions to make. Furthermore, the label of ‘entertainment’ is more of a placeholder for various functions, such as finding relief and inspiration, or play. Mobilization could be another function that also refers to the transfer of messages intended to cause people to act.

The functions proposed by Wright have been subject to discussion and still require further elaboration and being brought into dialogue with the purposes of cinema outlined by Elsaesser (from ‘defeating death’ to ‘play’). In addition to this, Hediger and Vonderau have observed three principal functions of industrial films, those of record (documentation), rhetoric (convincing stakeholders and clients), and rationalization (showing the production process in order to streamline it, and instructing workers how to act).85 There is a need for further understanding of connections between functions, how they may overlap and be situational, that is, how functions apply depending on the particular situation. Furthermore, Wright’s framework also requires modification in order to serve a historiographical purpose, as functions may change over time due to changing interests. Rather than a static or permanent condition, cinema is always subject to changing conditions, which has led Rick Altman to speak of ‘crisis historiography,’86 with crisis being the default condition of modernity and cinema alike.

However, it is also important to note Wright’s emphasis on ‘environment’ — which is connected with Elsaesser’s question of, “how does cinema figure in humans’ adaptation to their environment, what is cinema’s ecology, so to speak?”87 The distinguished functions are performed within social systems, small and large. While a system constitutes an environment within, there is yet another environment outside the system. The environment of cinema is multi-faceted, and this issue has attracted a lot of attention in recent years, following the spatial turn in the humanities. It concerns the place of production, the infrastructure of distribution, the locale of screening and consumption, and the socio-cultural context in which a film is regarded and assumes meaning.88

At a global scale, the largest environments are provided by the typologies proposed within world cinema history. While some of the categories are transnational, like Third Cinema, they are also localized, tied to particular places, and their links can be traced synchronically, through the international networks that exist between filmmakers and distributors.89 Something similar applies to related transnational categories. Naficy’s work on Accented Cinema, for example, includes various spatial markers, both textual and contextual.90

Emphasizing cinema’s relationship to its environment, ontology poses questions of ecology, for which I propose to build on the theory of cultural ecology.91 This idea was first developed by the anthropologist Julian Steward in the 1950s. An environment offers certain possibilities for making a living, they are explored and appropriated through particular ideas and values — an idea comparable to that of his contemporary, Braudel.92 This configuration of environmental structures, affected by human ideas and actions, creates a ‘culture core’: a set of preoccupations, practices, beliefs, and knowledge that directly relates to a culture’s subsistence. I have shown this in a previous case study, using Rotterdam as an example, showing that the city’s subsistence is based on the port and that its culture core can be identified accordingly.93

Expanding from this core, while simultaneously informed by it, there will be a proliferation of practices and associated ideas and values. This development is characterized by an increase in complexity through the division of tasks.94 The way these tasks are related is a matter of ‘integration,’ as Steward calls it, which happens at a higher level of organization.95 For example, the task of a parent teaching a child makes sense in relation to other activities within a household, which constitutes the level that integrates the different activities. Teaching at a school is integrated at neighbourhood or city level, and education through film happens at regional or national level. Different practices become interrelated and meaningful within a specific environment, which creates a ‘cultural ecology.’

Alongside environmental factors, there are also historical factors (or ‘influences’) that come from outside.96 Such factors include ideas, practices, or interests that have developed elsewhere as part of other histories or of general national or international developments. They may have no intrinsic relationship to the culture core of the place they affect, but the culture core provides the conditions for the application and appropriation of such influences. Still higher levels of cultural ecological integration must thus be taken into account in order to observe how differing ‘locales’ connect. To that end, I propose the use of anthropologist Ulf Hannerz’s concept of the city as a “switchboard of culture”.97 A city is not the source of all inventions; rather, it is a place where things come in, where connections are made, and transmissions take place. Through the ‘switchboard,’ ideas are simultaneously locally appropriated and sent out into the ‘world,’ feeding a general historical trend.

In my previous studies, I have shown that the theory of cultural ecology applies to media in an urban context. The challenge is to develop an understanding of a global cultural ecology and the position of cinema within it. One question here is how Steward’s concept of ‘culture core’ remains relevant at a global scale, and with it the reliance on the notion of subsistence. What happens when there are multiple centres, and, seen from a historical perspective, multiple genealogies? How do mobility and migration fit into this perspective? Hannerz may provide some direction as to how to answer these questions from an anthropological perspective through his concept of the ‘global ecumene,’ defined as “an open fairly densely networked landscape,” in which culture is organized.98

From a historical perspective, it is important to stress Steward’s aim to understand ‘multilinear evolution.’ Different levels of organization exist within and alongside each other, and each has its own temporal horizon. This approach corresponds to that of Braudel, due to his emphasis on the environment providing the structure in which different durations exist for various forms of organization. Developed at the same time, Braudel’s theory can be seen as the historical counterpart of cultural ecology. In Civilization and Capitalism, Braudel explains the dependence of cities on the countryside,99 and how their growth was interrelated to the development of states.100 When discussing the features of large cities, he writes: “Above all, a great city should never be judged in itself: it is located within the whole mass of urban systems, both animating them and being in turn determined by them”.101 Moreover, since the 16th century, cities in Europe “vied with each other in modernity”,102 while cities in countries across the world had always been centers of political concentration.103 These observations point in the direction with which to relate different locales as part of Hannerz’ global ecumene.

At this point, the main outline for the proposed historiographic framework has been drawn, but I want to add two possible directions. On the one hand, further elaboration of the given perspectives could occur through the field of ‘media ecology,’ a concept introduced by Neil Postman in 1968 for “the study of media as environments”.104 “These environments consist of techniques as well as technologies, symbols as well as tools, information systems as well as machines. They are made up of modes of communication as well as what is commonly thought of as media….”105 The focus here is on communication systems, but rather than a technological concern, Postman’s starting point has been a social one. “A medium is a technology within which a culture grows; that is to say, it gives form to a culture’s politics, social organization, and habitual ways of thinking”.106 He explained this more than three decades later, speaking about the humanism of media ecology, adding that media ecology “exists to further our insights into how we stand as human beings, how we are doing morally in the journey we are taking”.107 Postman’s initial concern with a culture’s growth holds a historiographical promise. Within the perspective of cultural ecology, media ecology can help to establish the functions, operations, and relationships of cinema.

On the other hand, such further elaboration could also take place in connection with the study of ecocinema, which encompasses various kinds of films addressing environmentalist issues.108 While the concerns of cultural ecology differ from the concern with human impact on nature mostly addressed by ecocinema, a common denominator can be found in the place occupied by cinema in the world. Especially relevant are cinema’s three ecologies, as explained by Ivakhiv109: social, material, and mental, which are features of the general ontology of cinema that I have proposed. Moreover, how these ecologies manifest at different levels, and how they interact, is a common concern of both ecocinema and cultural ecology. Within ecocinema studies, in which many case studies have been carried out regarding local concerns, the need for transnational, planetary perspectives has been addressed, moving towards ‘eco-cosmopolitanism’.110 The question here is how cinema interacts with the world, which can be answered by considering affective labour and physical infrastructures that are part of the world.111 This taps into ‘new materialism’ and the challenge of developing a media theory of things. Such a theory views all kinds of artefacts as media, and vice versa, as forms of expression and communication that exist within extensive infrastructures, through which they operate and enable multiple circulations of matter, images, and ideas. Such circulations affect and direct human action within complex ecologies, in which human and natural environments are related.112 These circulations have different durations within different time frames, and touch upon issues of obsolescence and sustainability relevant to ecocinema. Long-term developments can be brought into perspective through the application of ecological approaches, in order to better make sense of ephemeral human manifestations. This would present a common research prospect for ecocinema and the revisionist historiography proposed here.

Conclusion: Film and History, Towards a General Ontology

Considering the problem of the position of cinema in modern life, which is relevant to both historians and film scholars alike, I have raised the question of how a historiographical framework can be developed in order to acknowledge and understand the way in which cinema has contributed to major historical developments since the late 19th century. While the main revisionist movements in film historiography have addressed the material existence of cinema, I have called attention to world cinema history as another possible approach which, while sharing some features in common with new film history, also brings the issue of the representation and meaning of film back into discussion by following a text-context continuum.

Through a discussion of Third Cinema, being a movement that explicitly aims at social engagement, especially through what Solanas and Getano refer to as the ‘film act,’ I have identified features of the social position of cinema with regard to appropriation and strategies that have served specific social aims. This is most noticeable in Third Cinema, but by no means restricted to it. The way in which a film makes sense locally generates the properties of a general ontology of cinema, in particular the links between film content and the conditions of production and reception. I have also pointed out other ontological aspects, for example, the enigma of emergence; that is, of how a film, a collection of films, or an entire cinematic culture is more than the sum of its parts, which calls attention to (collective) cognitive processes, and the way in which experiences are synthesized. This occurs in the lives and minds of makers (or curators and historians), and in those of audiences. These cognitive or mental properties of an ontology of film relate to actual (physical and social) environments from whence inspiration has been drawn and which are in turn then fed by new ideas. Putting this ontology into a historical perspective, I have combined cultural ecology with total history.

The resulting framework sees cinema as part of a ‘global ecumene’ in which different cinemas exist alongside one another, as outlined by Chapman and Slobin, all with ties to certain regions or places as well as to networks connecting them. Each of these cinemas are systems in their own right, which have developed within particular epistemes (for the explanation of which Elsaesser’s media archaeology is of particular use). These systems generate discourses that, besides the films themselves, also encompass statements regarding both the production and reception of film (Klinger). In turn, these cinemas are part of larger socio-cultural systems. These systems are not fixed, and (using digital methods) could be mapped to analyze how they have changed. They are adaptive systems, and the place of cinema within them can be studied through the lens of Altman’s ‘crisis historiography.’ The coexistence of different cinemas, and similarly their coexistence with other cultural manifestations, each with differing durations and time frames, call for the application of Steward’s concept of multilinear evolution. Their entanglement is multidirectional and serves varying purposes. Mapping their interrelatedness, dynamics and the parameters at work is the challenge for cultural ecology.

Alongside this, various scales can be mapped, from the shooting locations of a single film, to the networks of the international film festival circuit, and the output of an entire film industry, or the provenance and reuse of archival collections. In such a methodology, digital tools could play an important role. The coexistence of cinematic practices does not just happen on a single level, but is layered, as part of different levels of integration within a cultural ecology. This means that individuals can be in conversation with communities, or society at large. Concurrently, further understanding is needed regarding inter-scale relations, which especially applies to cinematic functions. Different functions may simultaneously be observed at different levels of integration; for example, one film might serve both individual as well as collective memory, and similarly, large collections may serve individuals as well as communities. It may also be possible to identify functions other than the ones mentioned above, in order to re-evaluate Wright’s view.

Moving beyond the broader function of cultural memory, Ivakhiv’s three ecologies of cinema (social, material and mental) can be elaborated on historically. This will allow a shift from cultural memory to cultural cognition, to be recognized at different levels of integration, in order to understand how cinema contributes to social developments, material transformations, and the determination of collective values. In order to understand such an epistemology, researchers themselves need to be aware, as Gaines has argued (through White), of their own position and perspective and the purposes and interests they serve as part of the episteme that governs their thinking and action. While cinema performs a dual role of documentation and imagination, which affects actual developments, a similar role is performed by the historian. The problem faced by a global ecology, and a general ontology of cinema, is the lack of an outside perspective that allows us to assess positions and developments. But internal differentiation can be made, in order to create a space in between that enables a shift of positions, allowing for comparison between regions, times, and spatial-temporal scales. In this way we might be able to better understand how cinema has contributed to history, how it has framed history while, at the same time, being its product, and how reflections on cinema and history allow us to determine our own position in the world.

- 1Joanne Connel, “Film Tourism: Evolution, Progress and Prospects,” Tourism Management 33 (2012): 1007–1029.

- 2E.g. NASA official Brian Dunbar has written about it under the heading of “NASA History”: “50 Years Ago: 1968 Welcomed 2001.” NASA History, edited by Melanie Whiting, April 9, 2018. www.nasa.gov/feature/50-years-ago-1968-welcomed-2001

- 3Douglas Trumbull, VFX-supervisor of 2001, has said that “I meet scientists, engineers and astrophysicists almost every week who say they went into their line of work because they watched the film when they were young,” in: Phil Hoad, “50 years of 2001: A Space Odyssey — How Kubrick’s Sci-fi ‘Changed the Very Form of Cinema’,” The Guardian, April 2, 2018. www.theguardian.com/film/2018/apr/02/50-years-of-2001-a-space-odyssey-stanley-kubrick. See also: Lauren Fuge, “Fifty Years Later: Scientists Reflect on the Influence of 2001: A Space Odyssey,” Cosmos, October 17, 2018. https://cosmosmagazine.com/space/fifty-years-later-scientists-reflect-o…

- 4Personal communication of the author with Dr. Romen Matirosov of Yerevan Physics Institute, 2001.

- 5Danny Wedding, Mary Ann Boyd, and Ryan M. Niemiec, Movies and Mental Illness: Using Movies to Understand Psychopathology (Göttingen/Cambridge, MA: Hogrefe Publishing, 2014).

- 6Lauren Fuge. “Fifty Years Later: Scientists Reflect on the Influence of 2001: A Space Odyssey.” Cosmos, October 17, 2018. https://cosmosmagazine.com/space/fifty-years-later-scientists-reflect-on-the-influence-of-2001-a-space-odyssey/

- 7Barbara Klinger, “Film History Terminable and Interminable: Recovering the Past in Reception Studies,” Screen 38, no. 2 (1997): 108.

- 8Alexandra Chassanoff, “Historians and the Use of Primary Source Materials in the Digital Age,” The American Archivist 76, no. 2 (2013): 468.

- 9Ted Mico, John Miller-Monson, and David Rubel, Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies (New York: Owl Books & Society of American Historians, 1996); Robert Rosenstone, History on Film/Film on History (Harlow: Pearson, 2006).

- 10Marc Ferro, “Does A Filmic Writing of History Exist?” Film & History: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Film and Television Studies 17, no. 4 (1987): 89.

- 11Desmond Bell, “Documentary Film and the Poetics of History,” Journal of Media Practice 12, no. 1 (2011): 3.

- 12Ferro, “Filmic Writing,” 81–82; Rosenstone, History on Film, 158.

- 13For New Film History: Thomas Elsaesser, “The New Film History,” Sight and Sound 55, no. 4 (1986): 246–251; James Chapman, Mark Glancy, and Sue Harper, eds., The New Film History: Sources, Methods, Approaches (London: Palgrave MacMillan, 2007). For New Cinema History: Daniel Biltereyst, Richard Maltby, and Philippe Meers, eds., Explorations in New Cinema History: Approaches and Case Studies (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011). For Media Archaeology: Thomas Elsaesser, Film History as Media Archaeology: Tracking Digital Cinema (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2016).

- 14See, for example: Aristed Gazetas, An Introduction to World Cinema (Jefferson: McFarland, 2000); David Gallagher, ed., World Cinema and the Visual Arts (London: Anthem, 2002); Shohini Chaudhuri, Contemporary World Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2005); Catherine Grant and Annette Kuhn, eds., Screening World Cinema (London/New York: Routledge, 2006); Lúcia Nagib, Chris Perriam, and Rajinder Dudrah, eds., Theorizing World Cinema (London: I.B. Tauris, 2012); Asma Sayed, Screening Motherhood in Contemporary World Cinema (Bradford: Demeter Press, 2016); Patricia White, Women’s Cinema: World Cinema — Projecting Contemporary Feminisms (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015); Paul Cooke, Stephanie Dennison, Alex Marlow-Mann, and Rob Stone, eds., The Routledge Companion to World Cinema (New York: Routledge, 2018).

- 15Linda Badley, R. Barton Palmer, and Steven Schneider, eds., Traditions in World Cinema (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2006).

- 16This prospect also extends to history education, see: Ronald Briley, “Bringing World Cinema into the History Curriculum,” Teaching History: A Journal of Methods 41, no. 2 (2016): 73–83.

- 17See for example Milton Fernando González Rodriguez, Histrionic Indigeneity: Ethnotypes in Latin American Cinema, PhD Thesis (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 2019).

- 18Paul Rotha and Richard Griffith, The Film Till Now: A Survey of World Cinema (London: Vision/Mayflower, 1960), 17.

- 19This is also clear from the annual survey by The International Film Guide, published since 1964. The numbers of countries covered grew steadily over the years, see: Rosalind Galt and Karl Schoonover, eds., Global Art Cinema: New Theories and Histories (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 4.

- 20Lars Karl and Pavel Skopal, eds., Cinema in Service of the State: Perspectives on Film Culture in the GDR and Czechoslovakia, 1945–1960 (New York/Oxford: Berghahn, 2015), 234.

- 21Harry Rand, World Cinema: A Short History by David Robinson (review), Leonardo 9, no. 4 (1976): 344.

- 22Charles Musser, “Pordenone Silent Film Festival 2015,” October 18, 2015. http://www.charlesmusser.com/

- 23Elsaesser, Film History as Media Archaeology, 42.

- 24Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, ed., The Oxford History of World Cinema (Oxford/New York: Oxford University Press, 1997).

- 25Robert E. Brown, “World Music: The Voyager Enigma,” in Music in the Dialogue of Cultures: Traditional Music and Cultural Policy, ed. Max Peter Baumann (Wilhelmshaven: Florian Noetzel Verlag, 1991), 365–374.

- 26Brad Klump, “Origins and Distinctions of the ‘World Music’ and ‘World Beat’ Designations,” Canadian University Music Review 19, no. 2 (1999): 9.

- 27Paul Cooke, “Film and the End of Empire: Deconstructing and Reconstructing Colonial Pasts and their Legacy in World Cinemas,” in The Oxford Handbook of the Ends of Empire, ed. Martin Thomas and Andrew S. Thompson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), 665.

- 28James Chapman, Cinemas of the World: Film and Society from 1895 to the Present (London: Reaktion Books, 2003), 33–34.

- 29Chapman, Cinemas of the Worlds, 44.

- 30Mark Slobin, Global Soundtracks: Worlds of Film Music (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2008), xix.

- 31Slobin, Global Soundtracks, xix.

- 32Stephanie Dennison and Song Hwee Lim, eds., Remapping World Cinema: Identity, Culture and Politics in Film (London: Wallflower Press, 2006), 8.

- 33See also: Robert Stam, “Beyond Third Cinema: The Aesthetics of Hybridity,” in Rethinking Third Cinema, ed. Anthony R. Guneratne and Wimal Dissanayake (New York: Routledge, 2003), 31–48.

- 34Galt & Schoonover, Global Art Cinema, 8.

- 35Ibid., 3.

- 36Cooke, “Film and the End of Empire,” 661–677.

- 37Lars Kristensen and Ewa Mazierska, eds., Third Cinema, World Cinema and Marxism (New York: Bloomsbury, 2020).

- 38Kristensen & Mazierska, Third Cinema, 3.

- 39Dennison & Lim, Remapping World Cinema, 9; Andrew Dudley, “An Atlas of World Cinema,” in Remapping World Cinema: Identity, Culture and Politics in Film, ed. Stephanie Dennison and Song Hwee Lim (London: Wallflower Press, 2006), 19–29; Lúcia Nagib, “Towards a Positive Definition of World Cinema,” in Remapping World Cinema: Identity, Culture and Politics in Film, ed. Stephanie Dennison and Song Hwee Lim (London: Wallflower Press, 2006), 31; Cooke et al., Routledge Companion, 4.

- 40Scott Mackenzie, ed., Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 1.

- 41MacKenzie, Fim Manifestos, 1.

- 42Ibid.

- 43Teshome Gabriel, “Towards a Critical Theory of Third World Films,” Critical Interventions 5, no. 1 (2011): 187–203. This article was an elaboration of his PhD Thesis Third Cinema in the Third World: The Aesthetics of Liberation, defended in 1979 and published in 1982 (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1982).

- 44Gabriel, “Towards a Critical Theory,” 188.

- 45Ibid., 189.

- 46Mariano Mestman and Masha Salazkina, “Introduction: Estates General of Third Cinema, Montreal ‘74,” Canadian Journal of Film Studies 24, no. 2 (2015): 4–13.

- 47Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino, “Towards a Third Cinema: Notes and Experiences for the Development of a Cinema of Liberation in the Third World (Argentina, 1969),” in Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology, ed. Scott Mackenzie (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014).

- 48Kristensen and Mazierska, Third Cinema, 2; Luna Hupperetz, The Militant Film Circuit of Cineclub Vrijheidsfilms, Master’s thesis (Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit, 2020), 26.

- 49Rommy Albers, Simona Monizza, and Floris Paalman, “Cineclub Amsterdam Freedom Films at the International Institute of Social History,” paper presentation at Orphans Symposium: Radicals (Vienna: Austrian Filmmuseum, June 8, 2019); Hupperetz, Militant Film Circuit.

- 50Paulina Aroch Fugellie and André Dorcé, “Third Cinema after the Turn of the Millennium: Reification of the Sign and the Possibility of Transformation,” in Third Cinema, World Cinema and Marxism, ed. Kristensen Lars and Ewa Mazierska (New York: Bloomsbury, 2020), 141.

- 51Paul Willemen, “The Third Cinema Question: Notes and Reflections,” Framework 34 (1987): 4–38.

- 52John Akomfrah in Mike Wayne, Political Film: The Dialectics of Third Cinema (London: Pluto Press, 2001), 2.